Abstract

Dhat syndrome is described as a culture bound syndrome (CBS). There is an ongoing debate on the nosological status of CBS. Dhat syndrome has been found to be prevalent in different geographical regions of the world. It has been described in literature from China, Europe, Americas, and Russia at different points of time in history. Mention of semen as a “soul substance” could be found in the works of Galen and Aristotle who have explained the physical and psychological features associated with its loss. However, the current classification systems such as International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Conditions-10 (ICD-10) (World Health Organization (WHO)) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association) do not give guidelines to diagnose these culture-bound conditions in the main text. The revisions of these two most commonly used nosological systems (the ICD and DSM) are due in near future. The status of this condition in these upcoming revisions is likely to have important implications. The article reviews the existing literature on dhat syndrome.

Keywords: Culture bound syndrome, international statistical classification of diseases and related health conditions-10, dhat syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Dhat Syndrome is described as a culture bound syndrome (CBS).[1] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV defines and lists culture bound syndrome only in the appendix (appendix I, p. 844) as “Recurrent locality specific patterns of aberrant behavior and troubling experience that may or may not be linked to particular DSM IV category”.[2] The explicit assumption that “culture-bound syndromes are generally limited to specific societies or culture areas and localized folk” have resulted in CBS being viewed as an alien entity to the western world, thereby limiting global interest in understanding these conditions and bringing them meaningfully under the general classificatory system. However, these conditions are of concern to clinicians and researchers indigenous to the area; that face double difficulty of diagnosing and treating these syndromes without established diagnostic criteria and communicating their findings to peers in absence of established terminology.

There is an ongoing debate on nosological status of CBS.[3] Dhat syndrome has been found to be prevalent in different geographical regions of the world.[4] It has been described in literature from China, Europe, Americas, and Russia at different points of time in history.[5] Mention of semen as a “soul substance” could be found in the works of Galen and Aristotle who have explained the physical and psychological features associated with its loss.[6] However, the current classification systems such as International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Conditions-10 (ICD-10) (World Health Organization (WHO))[7] and DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association)[2] do not give guidelines to diagnose these culture-bound conditions in the main text. The revisions of these two most commonly used nosological systems (the ICD and DSM) are due in near future. The status of this condition in these upcoming revisions is likely to have important implications. The article reviews the existing literature on dhat syndrome.

METHODOLOGY

The review is based on a literature search carried out by the authors. The literature search included MEDLINE, CINHAL, EMBASE, IndMed, and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register databases. Search terms used included ‘dhat syndrome’, ‘culture bound syndrome’, and ‘transcultural psychiatry’. No publication year limits were applied, but the search was restricted to articles in English. The abstracts of articles retrieved in the search were manually scanned. Finally, full texts of the accessible articles were included in preparation of the manuscript. Additionally, standard textbooks on the topic were used during manuscript preparation. The available literature has been organized under the headings of description, sociodemographic correlates, diagnosis, clinical presentation, and laboratory investigations.

DESCRIPTIONS

Syndromes similar to dhat have been reported from China, Sri Lanka, Europe, Americas, and Russia at different points of time in history.[4] Similarly, latah (from Malayo-Indonesia) and imu (from Japan) have been considered by researchers to be behaviorally matching.[8] Simons and Hughes emphasized that despite differences in the meaning assigned to the experiences and behaviors, CBS share phenomenological similarity across historically unrelated and culturally dissimilar times and places.[8] Still other researchers have tried to reconcile CBS as culturally patterned variation of the relevant DSM-IV-TR category. Thus, amok is similar to the dissociation phenomena, ataque de nervios (Latin America) similar to anxiety disorders, “brain-fag” (Western Africa) can be considered under somatoform disorders, and boufée delirante (Western Africa) under psychosis. However, most investigators currently consider the relationship between the CBS and DSM-IV-TR or ICD-10 categories to be one of the co-morbidity rather than of one-to-one correspondence. Many culture-bound syndromes are closely associated with small number of psychiatric disorders yet are not fully subsumed by them. The conditional statement in the DSM-IV-TR glossary that these syndromes “may or may not” be linked to a psychiatric diagnosis makes it clear that the relationship between the culture-bound syndromes and psychiatric disorders is complex and still needs considerable research.

Problems of describing CBS comprehensibly and consistently results not only from lack of data regarding the phenomenology, symptomatology, and outcome of these syndromes but also from the absence of a uniform language of communication while reporting these cases. Understanding these problems, Yap suggested that in studying CBS, attempts should be made to distinguish “essential” from “accessory” symptoms as well as to establish the “natural history” of each disorder in its “elementary psychogenic form”.[9] Such method of study would lead first to a consistent definition of each disorder in the form of modal symptoms and then to universally valid mechanisms of psychopathology, providing a firm basis for cross-cultural clinical research. Levine and Gaw similarly proposed organization of CBS as recurrent collections of symptoms, which should be classified according to their “predominant symptom or symptoms” and listed as culturally patterned versions of the most relevant DSM-IV-TR category.[10] More recent guidelines for research and communication on culture bound syndromes can be derived from works of Guarnaccia et al., based on their research on Ataques de Nervios, a Latino-Caribbean cultural syndrome.[11] Guarnaccia et al., in 1999[11] proposed that four questions need to be answered in any comprehensive research on culture bound syndromes. First, the defining features of the illness needs to be elucidated along with a full phenomenological portrait from representative sample. Secondly, the location of the illness in social context needs to be characterized. The social, cultural, economic, spiritual, and situational factors that provoke, sustain, and exacerbate these illnesses needs to be described. Thirdly, the relation of the CBS to established psychiatric disorders needs to be studied. Fourthly, if a culture-bound syndrome and psychiatric disorder coexist; one must then study the sequence of onset of disorders and influence of life history of sufferer on these disorders, as mental illnesses cluster with health and social problems and cumulative social adversities are important risks for psychiatric disorder.

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CORRELATES

Dhat syndrome has been most commonly reported in young males of low or medium socioeconomic status.[12,13,14,15,16,17,18] Typically, patients are unmarried or recently married,[13] come from rural background and have a conservative attitude towards sex.[15,19,20,21,22,23,24] Though most studies report patients of dhat to belong to rural and suburban localities, and to be of low educational level; Kendurkar et al., based on a review of records 1242 patients, reported dhat to be prevalent irrespective of the domicile or the educational status of the patient.[25] Singh et al., and others also reported no relation to educational status.[20,22] Bhatia and Malik similarly found it to be prevalent irrespective of religion.[26] Some insight into the clustering of dhat syndrome in this particular age and socioeconomic group can be found in the works of Malhotra and Wig, who explained the clustering as a consequence of differential information and knowledge base of the individuals from different social groups.[14] In their study, the authors reported that respondents belonging to social class I discussed sex freely and were less likely to fear health consequences for semen loss when compared with lower social classes. Whereas, people in social class IV considered topics of sex a taboo, were less informed about the normal sexual process and were more likely to perceive nocturnal emission as abnormal.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

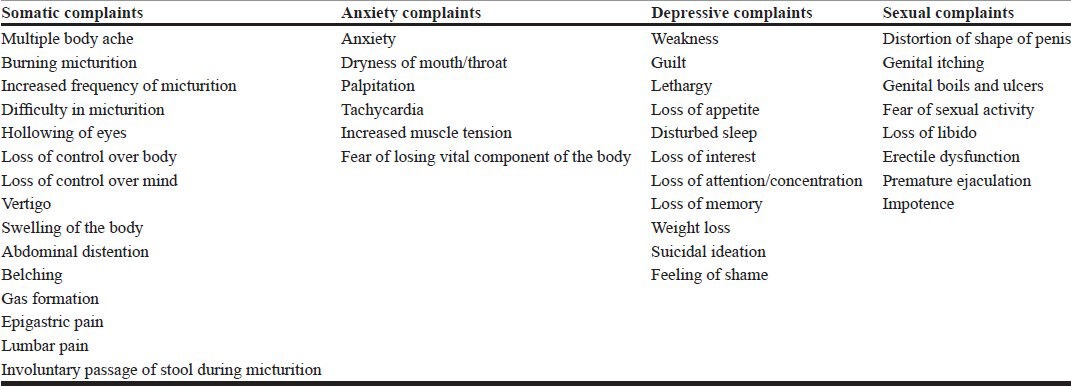

Patients of dhat syndrome, most commonly, present with a combination of vague somatic symptoms, anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and sexual problems. A summary of the symptoms reported by patients of dhat syndrome, integrated from all published literature and is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of presenting symptoms by patients with dhat syndrome

Beliefs regarding the causation of dhat syndrome varies between patients, but is often steered by cultural belief and opinion of indigenous medical practitioners. Indeed, some researchers have argued dhat syndrome to be a result of diagnosis difference or “label mismatch” between two conflicting systems of medicines (the western system of medicine and the indigenous system of medicine).[6,27] According to Ayurvedic system, health of the body is due to the balance between seven dhatus or essential components of the body and imbalance in these dhatus cause of wide range of physical disorders. These include rasa, fluid from digested food; rakta, blood; mamsa, muscle; meda, fat; ashti, bone; majja, marrow; and sukra, semen.[6] Of these, semen is the perfect substance (dhatu) and is a source of all physical and mental power.[13,20] Charaka samhita postulates that semen is all pervading within the body like “oil in the sesamic seed” and suggests one ejaculation per week in summer and total yearly ejaculation 168 times, as the optimal sexual frequency for humans.[28,29,30] The Shiva Samhita says “the falling of seed leads towards death, the keeping of one's seed is life. Hence, with all his power should a man hold his seed”. Wastage of semen due to excessive frequency of ejaculatory orgasm causes of imbalance in the dhatus with resultant physical illness.[6]

Therefore, many indigenous systems of medicine, following (or being influenced by) Ayurveda often label nonspecific somatic symptoms and weakness in patients as occurring due to disorders of the dhatus. Indigenous practitioners also have an inordinate focus on the sexual excesses of their patients[16] and the prevailing dictum is “it takes 40 drops of food and 40 days to form one drop of blood; 40 drops of blood to form one drop of marrow and 40 drops of marrow to form one drop of semen.”[4,6,31,32,33] While several others say this value to be 100 drops and not 40.[34,35,36] Therefore according to these systems, loss of semen from body will result in physical weakness and illness.[12]

In such a cultural belief milieu of sexual excess causing dhat disorder, it is quite understandable that patients report their dhat syndrome to be due to reading erotic literature or pictures, watching pornographic movies, unfulfilled longings or desires, bad company, premarital or extramarital affair, homosexuality, increased frequency of heterosexual sex,[6] betrayal in love, black magic by wife, intercourse during menstruation, and bad habits like alcoholism.[4,13,15,18] In other studies, patients also describe financial worries, venereal diseases, urinary tract infection (UTI), overeating, constipation, worm infestation, and disturbed sleep to be the causes of dhat syndrome.[31] Some also believed that penile blood is lost as semen following ejaculation.[37] Most studies report that patients harbor significant guilt with their erotic thoughts and masturbatory practices.[12] Semen loss is widely perceived to cause loss of “vital elixir of life” from the body[14] and is positively harmful.[6] Nightfalls were perceived as harmful by patients because during nightfall, dhat keeps falling continuously; thereby draining the body of all its energy.[14]

The morbid hypochondriacal fear that dhat syndrome will irreversibly harm the patient's body is well-documented in many studies.[13,21,23] Bhatia et al., reported that patients perceived consequences of dhat syndrome to be: Inability to produce male offspring, death of offspring at an early age, malformed fetus, anemia, leprosy, tuberculosis, permanent impotency, and shrinking of size of penis.[26]

DIAGNOSIS

There does not appear to be a clear and common definition of dhat syndrome. At the core of all these definitions is the preoccupation of the patient with the loss of dhat from the body and the belief that this loss results in significant harm to physical, mental, or sexual well-being. There is a wide variability in literature regarding the constituent of “dhat” and the mode of passage of dhat. Dhat has been defined in some studies specifically as semen,[12,20,26] while other studies define it broadly as any whitish discharge.[6,13,21] Earlier researchers from India believed dhat to be a form of phosphaturia.[20] Behere et al., reported from 50 consecutive dhat syndrome patients that 4% of patients believed dhat to be a mixture of semen and phosphate.[13] Bhatia et al., in their study of 93 patients with dhat syndrome, reported that 18% believed dhat to be pus, 12% believed it to be concentrated urine, and another 12% believed it to be sugar.[26] Other case reports suggest dhat to be semen, prostatic secretion, pus due to infection, lymph, and sugar.

The most common reported mode of passage of dhat is dhat mixed with urine.[6,14] However, loss of dhat during defecation,[22,23] with nocturnal emission; masturbation; or increased loss through heterosexual act, homosexual act; or through the anus have also been reported in literature and have been considered as cases of dhat syndrome.[4,21] Discharge of such white fluid has also been reported in females.[38,39,40] Chaturvedi et al., in a study of 200 female patients, found that 32% of psychiatric and 13% of nonpsychiatric patients attributed multiple somatic symptoms to nonpathological vaginal discharge.[41] Singh et al., reported a case of a woman who attributed somatic complaints and weakness to wetness experience during sexual intercourse, which represents phenomenological similarity to the male dhat syndrome.[42]

RELATIONSHIP WITH ESTABLISHED DIAGNOSTIC CLASSES

Most researchers report psychiatric comorbidities in cases of dhat syndrome rather than direct correlation with DSM-IV diagnosis. Depression is by far the most common reported co-morbidity with prevalence varying between 40-66% in various studies.[6,17,32,43] Anxiety disorders were found in 21-38% of patients.[15,26,17,32,43] Somatoform and hypochondriacal disorders are reported in as many as 40% of patients.[32,43] Various other studies report comorbid phobia,[26] stress reaction,[44] obsessive disorders, body dysmorphic disorders, and delusional disorders to occur along with dhat syndrome.

Few researchers have tried to find the status of dhat syndrome in relation to currently established psychiatric diagnosis. Jadhav argues it to be a case of cross-cultural misunderstanding[6] and Ranjith and Mohan define it as a functional somatic (misattribution) syndrome.[45,46] Perme et al., studied 29 patients of dhat syndrome using somatization screening index (SSI), screening version of illness behavior questionnaire (SIBQ), somatosensory amplification scale (SAS), Whitley index (WI), and Chalder fatigue scale; and also suggested a functional somatic syndrome status for the disorder.[47] Mumford et al., administered the Bradford somatic inventory (Urdu version) and Hamilton depression scale and performed factor analysis on patients presenting with complaints of urinary discharge. Patients with dhat syndrome were found to have a much higher hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) score, but no difference was seen in HADS anxiety score. Based on these results, he postulated dhat to be strongly related to the DSM diagnosis of depression.[5] Other authors have compared it to somatization disorder. On the contrary, Chadda in 1995, studied 50 patients of dhat syndrome and compared them with 50 neurotic controls using the SIBQ and showed that patients with dhat syndrome had a distinct illness behavior profile; suggesting that the illness might be a separate entity altogether.[48]

LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS

Many researchers have postulated that the passage of turbid urine might be due to sexually transmitted disease (STD) or UTI.[43] Gautham et al., looked into the urine infection rates of 366 symptomatic men and found 5.5% cases having chlamydia and gonorrhea infections.[18] Other researchers have postulated the turbidity of the urine due to urinary phosphates and oxalates.[31] Chadda et al., in a study of 52 patients with presenting complaint of dhat, found phopheturia and oxaluria in 6 and 10% of cases, respectively.[32] Other studies conducting urine examination on patients with dhat syndrome report phosphaturia, oxaluria, infections, pus cells, and alkaline urine.

MANAGEMENT

Although more than 50 case reports on the syndrome are available in published literature, almost no data is available on the management of such case. Most studies are cross-sectional and clinicians report high rates of dropout from therapy, as the patient shifts not only from doctor to doctor but from one system of medicine to another.[5,49] Behere and Natraj followed-up patients for a year and reported 66% of patients recovered completely with psychoeducation and minor tranquilizers.[13] Whereas, Bhatia reported best response with antianxiety or antidepressant drugs compared to those receiving psychotherapy only.[43] From the available literature it is known that, patients mostly acquire knowledge regarding the illness from friends, relatives, colleagues, roadside advertisements, lay magazines, hakims, vaids, and other practitioners of indigenous medicine.[5,18,26] Since the labeling of the syndrome is so rooted in indigenous medical practices; most patients perceive indigenous (desi) medicines, herbs, and advise of hakims/vaids[13] to be their best chances of cure.[5,22] Other patients believe dietary interventions, like ghee (butter), milk, protein and iron rich food, marriage, vitamin injections,[26] hormonal injections, and aphrodisiacs[15] as possible cures.

Regarding management of dhat syndrome, Wig originally suggested emphatic listening, reassurance and correction of erroneous beliefs.[1] Avasthi and Gupta in their “Manual for standardized management of single males with sexual disorders” proposed that the management of dhat syndrome should involve sex education, relaxation therapy, and also medications;[50] whereas Chadda and Ahuja suggested psychoeducation and culturally informed cognitive behavioral therapy for these patients.[32] However, no consensus exists and no empirical data comparing various nonpharmacological managements are currently available.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wig NN. Problems of mental health in India. J Clin Social Psychol (India) 1960;17:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.text rev. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. 1994 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balhara Y. Culture-bound syndrome: Has it found its right niche? Indian J Psychol Med. 2011;33:210–5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.92055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sumathipala A, Siribaddana SH, Bhugra D. Culture-bound syndromes: The story of dhat syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:200–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mumford DB. The ‘Dhat syndrome’: A culturally determined symptom of depression? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:163–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jadhav S. Dhat syndrome: A re-evaluation. Psychiatry. 2004;3:14–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.ICD-10. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. International statistical classification of diseases and health related problems. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons RC, Hughes CC. Dordrecht: D Reidel; 1985. The Culture-bound Syndromes: Folk Illnesses of Psychiatric and Anthropological Interest. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yap P. The Culture-bound reactive syndromes. Transcult Psychiatry. 1966;3:101–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine RE, Gaw AC. Culture-bound syndromes. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1995;18:523–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarnaccia PJ, Rogler LH. Research on culture-bound syndromes: New directions. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1322–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakra BR, Wig NN, Varma VK. A study of male potency disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 1977;19:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behere PB, Natraj GS. Dhat syndrome: The phenomenology of a culture bound sex neurosis of the orient. Indian J Psychiatry. 1984;26:76–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malhotra HK, Wig NN. Dhat syndrome: A culture-bound sex neurosis of the orient. Arch Sex Behav. 1975;4:519–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01542130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagadia V, Dave K, Pradhan P, Shah L. A study of 258 male patients with sexual problems. Indian J Psychiatry. 1972;14:143–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra Kar G, Varma L. Sexual problems of married male mental patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1978;20:365–70. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia M, Bohra N, Malik S. “Dhat” syndrome-a useful clinical entity. Indian J Dermatol. 1989;34:32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautham M, Singh R, Weiss H, Brugha R, Patel V, Desai NG, et al. Socio-cultural, psychosexual and biomedical factors associated with genital symptoms experienced by men in rural India. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:384–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan N. Dhat syndrome in relation to demographic characteristics. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh G. Dhat syndrome revisited. Indian J Psychiatry. 1985;27:119–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma KK, Khaitan BK, Singh OP. The frequency of sexual dysfunctions in patients attending a sex therapy clinic in north India. Arch Sex Behav. 1998;27:309–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1018607303203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta S, Surabhi D, Jain VK, Usha K, Vineet R. Profile of male patients presenting with psychosexual disorders. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2004;25:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avasthi A, Jhirwal O. The concept and epidemiology of Dhat syndrome. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2005;2:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akhtar S. Four culture-bound psychiatric syndromes in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34:70–4. doi: 10.1177/002076408803400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendurkar A, Kaur B, Agarwal AK, Singh H, Agarwal V. Profile of adult patients attending a marriage and sex clinic in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:486–93. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatia MS, Malik SC. Dhat syndrome: A useful diagnostic entity in Indian culture. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:691–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raguram R, Jadhav S. Historical perspectives on Dhat syndrome. NIMHANS J. 1994;12:117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obeyesekere G. The impact of Ayurvedic ideas on the culture and the individual in Sri-Lanka. In: Leslie C, editor. Asian Medical Systems. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1976. pp. 201–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Money J, Prakasam KS, Joshi VN. Semen-conservation doctrine from ancient Ayurvedic to modern sexological theory. Am J Psychother. 1991;45:9–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1991.45.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shankar BR, Gilligan D. The continuing story of dhat syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:261. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.3.261-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prakash O. Lessons for postgraduate trainees about Dhat syndrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:208–10. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chadda RK, Ahuja N. Dhat syndrome. A sex neurosis of the Indian subcontinent. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:577–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Hamad I, Scarcella C, Pezzoli MC, Bergamaschi V, Castelli F. Forty meals for a drop of blood. J Travel Med. 2009;16:64–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dhikav V, Aggarwal N, Gupta S, Jadhavi R, Singh K. Depression in Dhat syndrome. J Sex Med. 2008;5:841–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhikav V, Aggarwal N, Anand KS. Is Dhat syndrome, a culturally appropriate manifestation of depression? Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:698. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Painuly N, Chakrabarty S. The continuing story of dhat syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:260. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.3.260-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prakash O, Meena K. Association between Dhat and loss of energy: A possible psychopathology and psychotherapy. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70:898–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaturvedi SK. Psychasthenic syndrome related to leucorrhoea in Indian women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;8:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bang R. Why do women hide them? Rural women's viewpoints on reproductive tract infections. Manushi. 1989;1:27–63. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bang R, Bang A. Perception of rural women on white discharge: Ethnographic data from rural maharashtra. In: Gittelsohn J, Bentley M, Pelto P, Nag M, Pachauri S, Harrison A, et al., editors. Listening to Women Talk about their Health Issues: Evidence from India. New Delhi, India: Har-Anand Publication/Ford Foundation; 1994. [Last accessed date: 10.12.2012]. pp. 80–94. Available from: http://www.searchgadchiroli.org/Research%20Paper/perception%20of%20women%20on%20white%20discharge.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS, Issac MK, Sudarshan CY. Somatization misattributed to non-pathological vaginal discharge. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:575–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90051-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh G, Avasthi A, Pravin D. Dhat syndrome in a female-a case report. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:345–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhatia MS. An analysis of 60 cases of culture bound syndromes. Indian J Med Sci. 1999;53:149–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Silva P, Dissanayake S. The loss of semen syndrome in Sri Lanka: A clinical study. Sex Marital Ther. 1989;4:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ranjith G, Mohan R. Dhat syndrome: A functional somatic syndrome? Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:77. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranjith G, Mohan R. Dhat syndrome as a functional somatic syndrome: Developing a sociosomatic model. Psychiatry. 2006;69:142–50. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2006.69.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perme B, Ranjith G, Mohan R, Chandrasekaran R. Dhat (semen loss) syndrome: A functional somatic syndrome of the Indian subcontinent? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:215–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chadda RK. Dhat syndrome: Is it a distinct clinical entity? A study of illness behaviour characteristics. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:136–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sathyanarayana Rao TS. Some thoughts on sexualities and research in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:3–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prakash O, Rao TS. Sexuality research in India: An update. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S260–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]