Abstract

Background:

World Health Organization's Quality of Life – Spirituality, Religiousness and Personal Beliefs Scale (WHOQOL SRPB) is a valuable instrument for assessing spirituality and religiousness. The absence of this self-administered instrument in Hindi, which is a major language in India, is an important limitation in using this scale.

Aim:

To translate the English version of the SRPB facets of WHOQOL-SRPB scale to Hindi and evaluate its psychometric properties.

Materials and Methods:

The SRPB facets were translated into Hindi using the World Health Organisation's translation methodology. The translated Hindi version was evaluated for cross-language equivalence, test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and split half reliability.

Results:

Hindi version was found to have good cross-language equivalence and test-retest reliability at the level of facets. Twenty-six of the 32 items and 30 of the 32 items had a significant correlation (ρ<0.001) in cross language concordance and test-retest reliability data, respectively. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.93, and the Spearman-Brown Sphericity value was 0.91 for the Hindi version of SRPB.

Conclusions:

The present study shows that cross-language equivalence, internal consistency, split-half reliability, and test-retest reliability of the Hindi version of SRPB (of WHOQOL-SRPB) are excellent. Thus, the Hindi version of WHOQOL-SRPB as translated in this study is a valid instrument.

Keywords: Hindi translation, religiousness, spirituality, WHOQOL-SRPB

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade or so, spiritual or existential well-being has been recognized as an important dimension of Quality of life (QOL). Taking this into account, World Health Organization (WHO) designed WHO's Quality of Life – Spirituality, Religiousness and Personal Beliefs (WHOQOL-SRPB) scale to assess religious, spiritual, and personal beliefs as a domain of QOL, which is distinct from psychological and social domains.[1]

The WHOQOL-SRPB scale that has 32 questions, covering QOL aspects related to spirituality, religiousness, and personal beliefs, which was developed from an extensive pilot test of 105 questions carried in 18 centers around the world. The WHOQOL-SRPB scale acknowledges that some people follow a particular religion, while some others do not but believe in a higher spiritual entity. Some, however, do not follow both, but do have strong personal beliefs (such as scientific theory or a particular philosophical view) that guide them in day-to-day activities. The WHOQOL-SRPB makes allowance for these differing preferences as the questions are so framed that each individual can answer keeping one's own particular belief system in mind. Due to these, WHOQOL-SRPB can be considered as a valuable instrument to assess spirituality and religiousness. The initial evaluation of the scale was not limited to ill population and this makes it an ideal measure to study the spiritual QOL in diverse populations, including healthy subjects.[1]

The 32 items of SRPB are supposed to be used in conjunction with the WHOQOL-100.[2,3] The 32 questions are divided into 8 facets, each comprising 4 items and the facets are named as “spiritual connection,” “meaning and purpose in life,” “experiences of awe and wonder,” “wholeness and integration,” “spiritual strength,” “inner peace,” “hope and optimism,” and “faith.” Responses to each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 [‘not at all’] to 5 [‘an extreme amount’]). Each facet score is derived by averaging the score obtained from the responses to the 4 questions comprising that particular facet. As SRPB is supposed to be used with WHOQOL-100, the SRPB domain consists of the 9 facets that include the spirituality domain of the original WHOQOL-100 scale and the remaining 8 SRPB facets. The alpha value for various SRPB facets are reported to be strong, ranging from meaning and purpose in life (α=0.77) to faith (α=0.95).[1]

However, non-availability of this self-administered instrument in local language (Hindi in our context) is an important limitation in using this scale, as a large proportion of population in India still is not very comfortable with English language. Considering the fact that Hindi is the dominant language spoken and understood by a large portion of the population in India and as WHOQOL-100 is available in Hindi,[2,3] it was considered that translation of the WHOQOL-SRPB to Hindi would be useful. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to translate the English version of the SRPB facets of WHOQOL-SRPB scale to Hindi and evaluate its psychometric properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at a tertiary care multispecialty hospital. The translation procedure was part of a larger study that attempted to study spirituality, religiousness, and personal beliefs of patients with schizophrenia.[4,5] Ethical Review Board of the Institute approved the study and all participants were recruited after obtaining written informed consent.

Translation process

Translation was carried out according to the methodology described by WHO.[6] The 32 items were translated from English to Hindi by 3 bilingual mental health professionals who had sufficient knowledge of both the languages (spoken and written) and had received formal education in both languages. The translators were knowledgeable about both the English-speaking and Hindi-speaking cultures and idioms and had undertaken translation and development of other health-related instruments in the past.[6,7,8,9,10] Once the translated versions were available, an expert panel (comprising three members other than the translators) was convened. These members were experts in psychological and social fields of health, as well as had experience in instrument development and translation.

The translated versions were reviewed by the members of the expert panel who also had access to the English version of WHOQOL-SRPB instrument. The goal in this step was to identify the best translated version, make alternate suggestions, and by consensus resolve the difficulties in expressed meaning of the translated items. The members focused on overall quality of translation, meaning of words, and ease of understandability/comprehensibility of the language. The panel members questioned some words or expressions and made individual suggestions, which were discussed jointly. The changes that were agreed upon by all three members were incorporated and a draft of translated version was developed. The draft of translated version was then given to another 3 bilingual mental health professionals for back-translation. The back-translators had no knowledge or access to the English version of WHOQOL-SRPB instrument. During the process of back-translation, emphasis was also on conceptual and cultural equivalence and not merely linguistic equivalence. The back-translated versions were compared with the English version of WHOQOL-SRPB instrument by the expert panel and the Hindi translated version was modified to remove the ambiguity in the meaning of words or phrases by consensus after reviewing all the 3 back-translations and a revised version was made. To further improve the quality of translation, the revised version was given to ten members of the community in which it was to be used. After these respondents completed the questionnaire, they were interviewed to enquire as to whether they were able to comprehend as to what each item was attempting to address. Any words they did not understand or any word or expressions that they found unacceptable were also enquired into. The respondents were also asked to make suggestions regarding the use of words, phrases/idioms and framing of questions that in their opinion would improve the understandability of the instrument. The expert panel reviewed all the suggestions received and after thorough discussion those deemed appropriate were incorporated and final translated version was accepted.

Psychometric evaluation

The final Hindi version was assessed for cross language concordance and test-retest reliability. For this, participants were recruited by convenient sampling from those who were attending the psychiatry services of the Institute. The participants included primary caregivers of patients, hospital staff, and patients with schizophrenia in remission. For studying the cross language equivalence, bilingual participants who were proficient in Hindi and English were recruited, while for studying test-retest reliability, individuals well versed with Hindi were recruited. For cross language equivalence, a crossover design was followed with half the subjects (selected randomly) being given either English or Hindi versions first. The other language version (English or Hindi as applicable) was given one week later to the same participants. Another set of participants was given the Hindi version twice, one week apart for assessing test-retest reliability. Two assessments were done 1 week apart so as to negate any actual change in QOL status between the two ratings and remove memory bias due to too close observations.

Statistical analysis

Frequency and descriptive analyses were carried out for the demographic variables. Paired t-test and intra-class correlation were studied to assess the cross language concordance between item scores and between facet scores of English and Hindi versions. Similarly, paired t-test and intra-class correlation were performed to assess the test-retest reliability by comparing the scores (at baseline and 1 week later) obtained on final Hindi version. Cronbach's alpha was used to examine the internal consistency, and the Spearman-Brown Sphericity coefficient was used to determine the split-half reliability of the Hindi SRPB scale.

RESULTS

For the process of cross language equivalence, the Hindi and English versions were given to 23 participants, and for the test-retest evaluation, the scale was given to 20 participants.

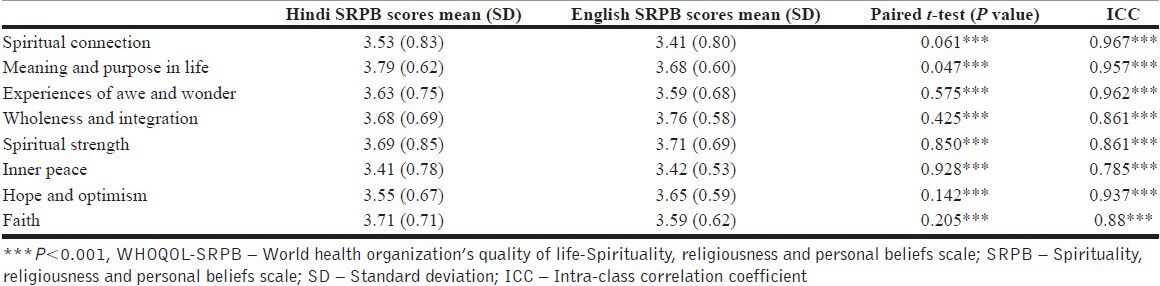

Cross-language concordance

The mean age of the participants was 42.09 years (range: 20-64 years). Ten (43.5%) were males. A majority of them had at least 15 years of schooling (n=18, 82.8%). As depicted in Tables 1 and 2, there were significant correlations between the English and Hindi versions of the WHOQOL-SRPB at the level of each facet and item/question of the WHOQOL-SRPB. The intra-class correlation value for the various facets ranged from 0.86 to 0.96. The intra-class correlation value was significant for each item and varied from 0.58 to 0.97, except for 2 items as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Cross language concordance between the Hindi and English versions of WHOQOL-SRPB facets

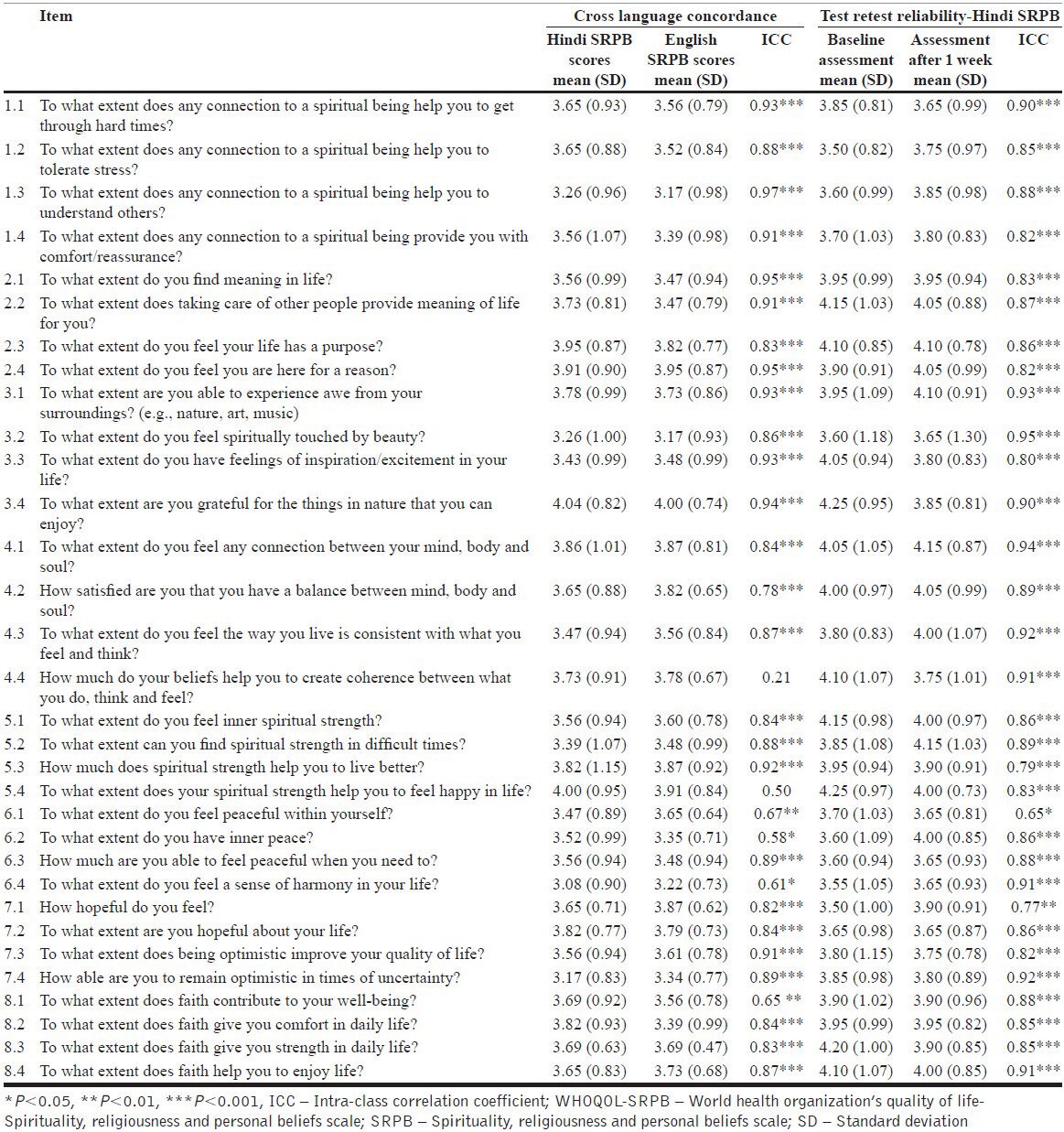

Table 2.

Cross language concordance between the Hindi and English versions of WHOQOL-SRPB and test-retest reliability of Hindi version of WHOQOL-SRPB

Test-retest reliability

For this, the sample consisted of 20 participants. The mean age of the participants was 38.05 years (SD – 15.16; range: 20-70 years) and there were equal number of males and females (i.e. 10 each). All the participants had received 10 years or more of formal education.

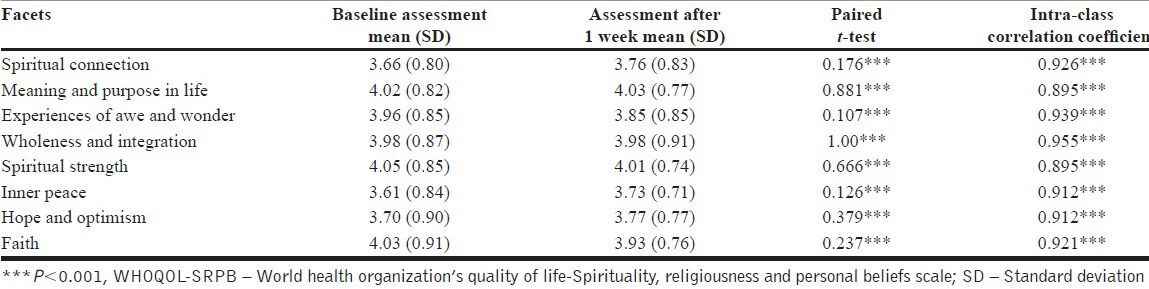

The Intra-class correlation coefficient was significant (P<0.001) for each facet and ranged from 0.89 to 0.95 [Table 3]. At the item level, there was significant correlation between both the assessments, with significance level <0.001 for 30 of the 32 items, <0.01 for one item, and <0.05 for the remaining 1 item [Table 2].

Table 3.

Test-retest reliability of Hindi version of WHOQOL-SRPB facets

Internal consistency and split-half reliability

For determining the internal consistency and split half reliability data of 43 participants, responses on Hindi version of the 23 participants in the cross-language equivalence and baseline responses of the 20 participants of the test re-test reliability were used. The Cronbach's alpha (as a measure of internal consistency) was 0.93, and the Spearman-Brown Sphericity coefficient (for assessing split-half reliability) was 0.91 for the Hindi version of SRPB. For the English version, data of 23 participants who participated in the cross-language equivalence were used. The Cronbach's alpha (as a measure of internal consistency) was 0.85, and the Spearman-Brown Sphericity coefficient (for assessing split-half reliability) was 0.77 for the English version of SRPB.

DISCUSSION

Findings of the present study show that the Hindi version of SRPB as translated for this study is a psychometrically valid instrument evidenced by the fact that it has good test re-retest reliability, cross-language equivalence, internal consistency, and split half reliability.

The methodology of translation and back translation used in this study is a well-established method to achieve the goal of translating to a conceptually equivalent and acceptable instrument that is culture sensitive and acceptable to the local population. In translation research, it is rightly emphasized that while translating an instrument “merely the word/phrase to word/phrase” is not sufficient but the conceptual meaning of the text has to be understood and then translated.[6] Other issue considered important while translating and validating an instrument is the consideration for cultural differences, because certain concepts, which may be native to one culture may be foreign to another. Furthermore, certain features of the language, such as idioms, are very difficult to translate and make little sense in a different cultural context.[11] In this study, the translation process took these into account. Also, lay persons belonging to the community in which the scale is purported to be used were involved in the translation process so as to understand the ease and understandability of the language used in the scale.

In the present study, the test-retest reliability at the facet level was good for all the facets. At the item level too, the test-retest reliability of each item was found to be very good. Results of the present study are comparable to the reliability analysis of the original scale (WHOQOL SRPB group, 2006) that showed an alpha correlation coefficient for the SRPB facets to be strong, ranging from 0.77 to 0.95. An overall strong ICC for all the facets in the present study indicates that the quality of translation is acceptable for use in Hindi-speaking population.

In the present study, the cross language equivalence at the facet level was good. At the item/question level too, there was significant correlation for 30 of the 32 items. These findings suggest that the Hindi SRPB version assesses the same concepts as the English SRPB instrument and it has good test-retest reliability where repeatability is concerned. Saxena et al.[3] while validating the Hindi version of WHOQOL-100 noted that despite some cross linguistic equivalence between Hindi and English versions, there were significant differences in one-third of facet and domain scores. However, in the present study, this was not that evident. This should be understood in the light of the fact that the concepts of spirituality and religiousness are integral to the Indian culture and most people have imbibed and internalized spirituality without any active effort. Thus, the construct is not new to the Indian population and improves the chances of comprehensibility of the items as opposed to certain items assessing other domains of QOL. Such findings suggest that the quality of cross-cultural translation relies heavily on the acceptability of a construct in that culture.

Findings of the present study reflect that although the internal consistency and split-half reliability of both Hindi and English version of SRPB are good, the same parameters for the Hindi version were better than the English version. These findings echo the concerns of Saxena et al.,[3] who while studying the psychometric properties of the Hindi translation of the WHOQOL-100 found lower reliability of facets in English version. The authors raised concern regarding application of the scale in subjects who are proficient in a language but are from a different culture.

To conclude, the present study shows that cross-language equivalence, internal consistency, split-half reliability, and test-retest reliability of the Hindi version of WHOQOL-SRPB are excellent. The internal consistency and split-half reliability of the English version of WHOQOL-SRPB was also found to be good. However, we did not examine the test-retest reliability for the English version, which is a limitation of present study. Future research in the same areas of the English version is warranted. The predictive and convergent validity of the scale was also not measured in the present study. In future, the Hindi version of the SRPB can be used as a self-rated measure along with Hindi version WHO-QOL-100 to measure the different aspects of QOL of various patients groups, their caregivers, and people in the community.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the present study suggest that Hindi version of WHOQOL-SRPB as translated in this study is a valid instrument.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHOQOL SRPB Group. A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1486–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxena S, Chandiramani A, Bhargava R. WHOQOL-Hindi; A questionnaire for assessing quality of life in health care settings in India. World Health Organization Quality of Life. Natl Med J India. 1998;11:160–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saxena S, Quinn K, Sharan P, Naresh B, Yuantao-Hao Power M. Cross-linguistic equivalence of WHOQOL-100: A study from North India. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:891–7. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah R, Kulhara P, Grover S, Kumar S, Malhotra R, Tyagi S. Contribution of spirituality to quality of life in patients with residual schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190:200–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah R, Kulhara P, Grover S, Kumar S, Malhotra R, Tyagi S. Relationship between spirituality/religiousness and coping in patients with residual schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1053–60. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9839-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en .

- 7.Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Ghormode D, Dutt A, Kate N, Kulhara P. An Indian adaptation of the involvement evaluation questionnaire: Similarities and differences in assessment of caregiver burden. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2011;21:142–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Scale for positive aspects of caregivingexperience: Development, reliability and factor structure. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2012;22:62–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nehra R, Chakrabarti S, Sharma R, Kaur R. Psychometric properties of the Hindi version of the coping checklist of Scazufca and Kuipers. Indian J Clin Psychol. 2002;29:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nehra R, Kulhara P, Verma SK. Adaptation of social support questionnaire in Hindi. Indian J Clin Psychol. 1996;23:33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren XS, Amick B, 3rd, Zhou L, Gandek B. Translation and psychometric evaluation of a Chinese version of the SF-36 Health Survey in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]