Abstract

Background:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is the most common type of violence against women. It is a major public health problem and violates the fundamental human rights of women.

Aim:

To determine the prevalence, pattern and consequences of IPV during pregnancy in Abakaliki, Southeast Nigeria.

Subjects and Methods:

A semi-structured questionnaire was designed for cross-sectional survey of pregnant women attending antenatal clinic between April and June 2011 at the Federal Medical Centre Abakaliki. A total of 321 questionnaires were correctly filled and then analyzed using Epi info software 2008 (Atlanta Georgia, USA).

Results:

Out of the 321 booked pregnant women, 44.6% (143/321) reported having been abused in the index pregnancy. Age of woman, family setting, religion, educational level of couples, parity and social habits of their husbands significantly influenced IPV (P < 0.05). The common causes of IPV were no identifiable cause (20.1%) 29/144, domestic issues (19.4%) 28/144, keeping late nights (12.5%) 18/144 and financial problem (11.8%) 17/144. Verbal abuse (60.1%) 86/143 was the most common type of abuse and most pregnant women resorted to praying (31.5%) 46/146, crying (24.7%) 36/146, and begging (22.6%) 33/146 as their major reactions to IPV. Eleven (7.7%) 11/143 pregnant women were hospitalized while (21%) 30/143 sustained emotional and physical injury. Apologies were tendered after IPV by 84.6% (121/143) of husband. Majority (83.9%) 120/143 of the abused did not support reporting IPV.

Conclusion:

Various types of IPV are still practiced commonly in our environment. IPV poses great threat to the reproductive health of all women especially during pregnancy.

Keywords: Abakaliki, Intimate partner violence, Nigeria, Pregnancy

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a significant public health issue in both developed and developing countries of the world.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) defines IPV as the range of sexually, psychologically and physically coercive acts used against adult and adolescent women by a current or former male partner.[2]

IPV is one of the most important reproductive health and rights, gender and public health issue of our time.[3] The WHO, non-governmental organizations and other agencies have recognized this and called on countries to take appropriate measures to prevent violence against women through numerous conventions and conferences.[3] In the midst of all these conventions and conferences, IPV is still very common, affecting millions of women worldwide.[4] It cuts across ethnic, cultural, socio-economical and religious barriers, impinging on the right of women to participate fully in the society. Globally especially in Nigeria, there is a gross under reporting of violence against women.[5,6,7,8,9] The prevalence in Nigeria varies from one region to the other with a range of 11-79%.[5,6,7,8] This wide range believed to be mainly because of the facts that there is no standard method for estimation of IPV. According to the WHO, surveys around the world indicate that approximately 10-69% of women report being physically assaulted by an intimate male partner at some point in their lives.[5]

Factors that lead to IPV are complex and numerous, ranging from no offence to major offences like financial problems, bad social habits, religious issues, and undue interference of a third party especially in-laws.[6,7,8,9,10] There has been an established relationship between pregnancy and IPV in previous studies.[1,10] Unfortunately IPV is perceived as a cultural norm or penal code and accepted as part of the rules guiding intimate partner relationship in some communities in different countries.[5,8,10]

However, the fact remains that the health and psychosocial consequences of IPV are enormous. IPV posses great threat to attainment of goals of Safe Motherhood Initiative and the Millennium Development Goals especially those concerned with reduction of maternal and child morbidity and mortality.[3] During pregnancy reported complication of IPV include preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, anemia, infection, miscarriage, first and second trimester bleeding, fetal distress, antepartum hemorrhage, intrauterine growth retardation, among other adverse pregnancy outcomes.[4,7,10,11,12,13] These consequences could be through direct or indirect mechanisms and could be prevented.[7,10]

The goal of the prevention is simply to stop IPV though it is as complex as the problem.[14] Preventive efforts are targeted towards promoting healthy, respectful and non-violent relationship. Furthermore this could be done by reducing the known risk factors and promoting protective factors.[15,16,17,18,19]

Pregnancy and postnatal period within two months of delivery provide unique opportunity to screen for domestic violence because women tend to trust and confide in health workers when ordinarily they will not.[9,17] This was one of the reasons why pregnant women were chosen for this study. Few studies have been done on this topic in the Southeast Nigeria and none has been done at Federal Medical Centre Abakaliki. This study was designed to estimate the prevalence, pattern and consequences of IPV among booked pregnant women at Federal Medical Centre, Abakaliki Southeast of Nigeria.

Subjects and Methods

This cross-sectional study on pregnant women was conducted at the Antenatal clinics of the Federal Medical Centre, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State of Nigeria between April and June 2011. The Federal Medical Centre is located in the capital city of the State and serves as a major referral center for the State and other neighboring States.

The participants were pregnant women who came for antenatal visits. Those too ill to participate were excluded and only those who had made at least one previous visit (booked) were recruited for the study consecutively. Those with at least one previous visit will not be apprehensive or afraid of the health workers. Pregnant women who came with their husbands were also excluded but could be included in subsequent visit if not accompanied by their husbands. Pregnant women who were not married were excluded from the study.

A minimum sample size of pregnant women was statistically determined for the study using prevalence of 13.6% reported by Umeora et al.[20], confidence interval of 95% and standard error of 5% as 230. This sample size was increased to 350 in other to increase the power of the study.

A pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire was administered consecutively by research assistants to the pregnant women who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Information on whether the pregnant women have been abused physically, sexually and psychologically during pregnancy was sought as well as the type of IPV by their husbands. The reactions, problems, burdens and solutions to IPV were also inquired from the pregnant women. They were interviewed in a private apartment within the clinic by the research assistants. Verbal consent was obtained before administration of the questionnaire.

Ethical approval was also obtained from the research and ethics committee of our hospital. The responses were coded, entered and analyzed using the 2008 Epi-Info Version 3.5.1 Statistical Software (Atlanta Georgia, USA). Descriptive analysis was used for the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and other variables. Binomial logistic regression was used to assess the association between some selected socio-demographic variables and the reported experience of IPV among the pregnant women at level of significance P < 0.05.

Results

Of the 350 semi-structured questionnaire administered, 321 (91.7%) 321/350 were correctly filled, returned and analyzed. The mean age of the respondents was 27.4 (4.7) years.

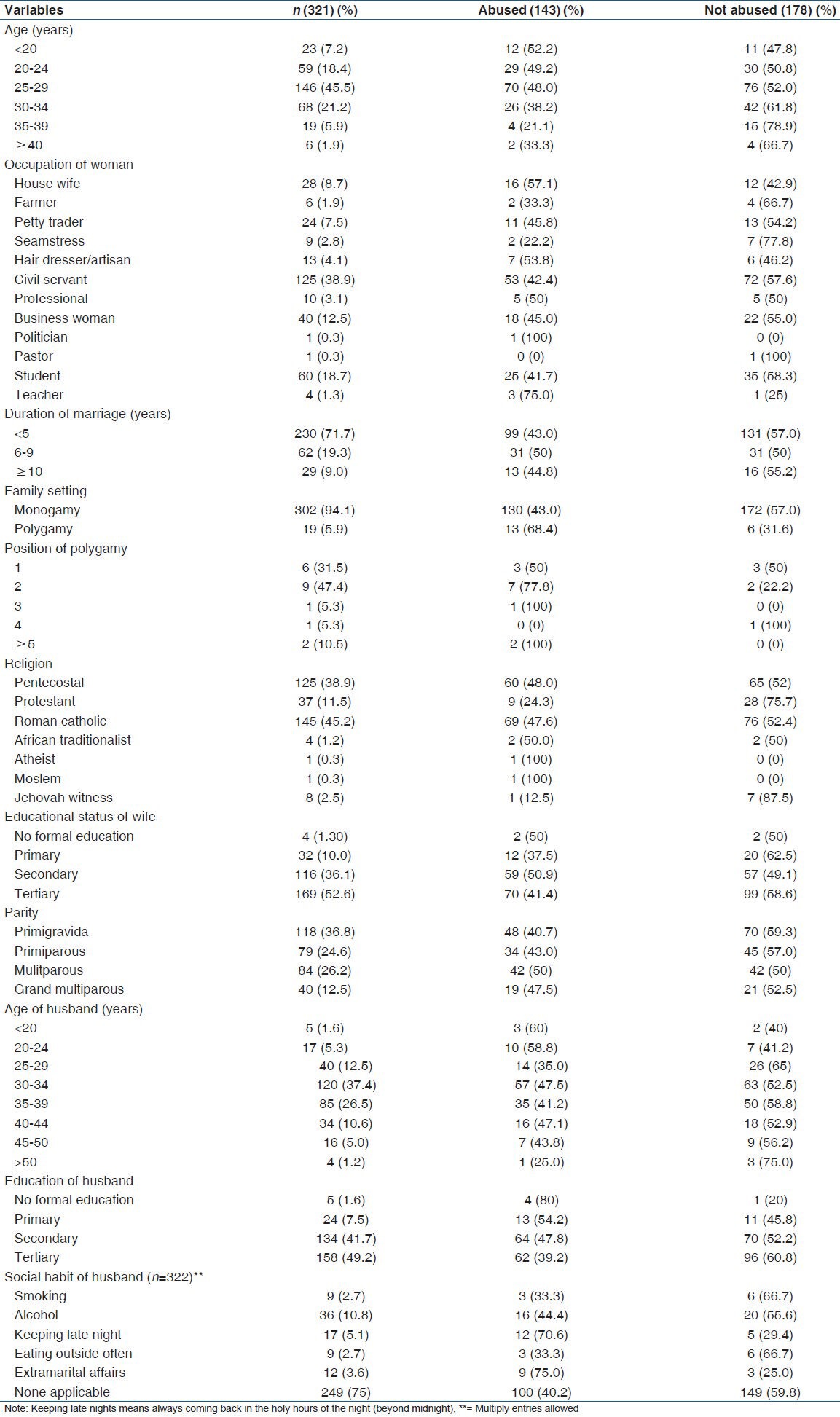

Table 1 shows sociodemographic characteristics and its relationship to physical, sexual and psychological IPV. The overall prevalence of IPV in this study was 44.6% (143/321). The most frequent age group among the respondents was 25-29 years. The highest percentage (52.2%) 12/23 of IPV was seen in women <20 years of age while the lowest 21.1% (4/19) was in the age bracket of 35-39 years. Civil service 38.9% (125/321) was the commonest occupation noted from the respondents. Politicians, Teachers, Housewives and Hair dressers were the common culprits of IPV with percentages of 100% (1/1), 75% (3/4), 57.1% (16/28) and 53.8% (7/13) respectively. A total of (18.7%) 60/321 students responded and (41.7%) 25/60 were abused in pregnancy. The duration of marriage of less than 5 years had the least IPV of (43.1) 99/230 whereas the highest IPV (50%) 31/62 was seen in marriages lasting between 6 and 9 years. Those who are Polygamy had the highest percentage of IPV (68.4%) 13/19 whereas monogamy had (43.0%) 130/302.

Table 1.

Socio-demo graphic characteristics and intimate partner violence

Most of the respondents were Christians. Among these Christians IPV was commonest among Pentecostals (48%) 60/125. All the respondents of Moslem and Atheist had IPV in pregnancy. Majority of the IPV occurred among those with secondary education (50.9%) 59/116 and no formal education (50%) 2/4.

The least IPV was recorded among those with primary education (37.5%) 12/32. IPV among those with Tertiary education was (41.4%) 70/169. IPV was noted to be highest among multiparas (50%) 42/84 and least (40.7%) 48/118 among primigravida.

Husbands < 20 years were noted to abuse their pregnant wives more commonly with percentage of 60% (3/5). This is closely followed by men between the ages of 20 and 24 years (58.8%) 10/17. IPV is least among man who are > 50 years (25.0%) 1/4. The educational status of Husband showed that Husband with no formal education and primary education as their highest form of education were the main perpetrators of IPV 80% (4/5) and 54.2% (13/24), respectively.

Husbands that attained Tertiary education were the least perpetrators of IPV 39.2% (62/158). Extramarital affairs (keeping girls/women friends) was the commonest social habit (75%) 9/12 of Husbands amongst women who suffered IPV. This was closely followed by keeping late nights in (70.6%) 12/17. The least social habit findings among husbands were smoking and eating outside with same percentage of 33.3 (3/9).

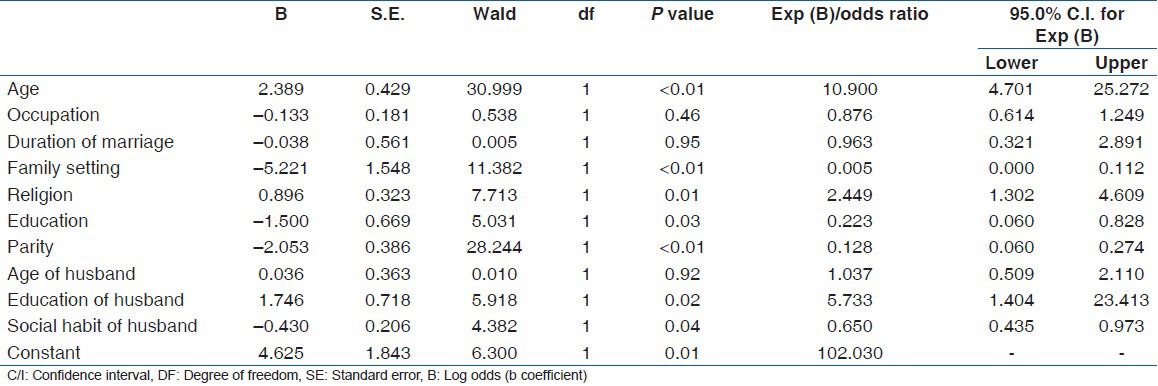

Table 2 shows adjusted odds ratios of IPV against the socio-demographic variables. There was significant association when the model was adjusted for age (odds ratio 10.9, 95% confidence interval 4.70-25.27; P < 0.01), family setting (odds ratio 0.005, 95% confidence interval 0.000-0.112; P < 0.01), religion (odds ratio 2.449, 95% confidence interval 1.302-4.609, P = 0.01), education of wife (odd ratio 0.223, 95% confidence interval 0.06-0.824, P = 0.03), parity (odds ratio 0.128, 95% confidence interval 0.060-0.274, P < 0.01), education of husband (odds ratio 5.733, 95% confidence interval 1.404-23.413, P = 0.02), and social habit of husband (odds ratio 0.650, 95% confidence interval 0.435-0.973, P = 0.04).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of intimate partner violence against the socio-demographic variables

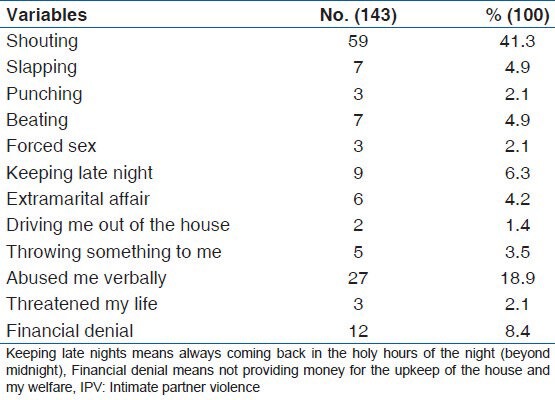

Table 3 shows the type of IPV meted on pregnant women by their Husbands. Shouting and verbal abuse were the common types of IPV seen in this study with percentage of 41.3 (59/143) and 18.9 (27/143), respectively. The least type of IPV was being driven out of the house at night by the husband (1.4%) 2/143. Financial denial 8.4% (12/143), keeping late Night 6.3% (9/143) and beating 4.9% (7/143) were other common types of IPV. Threatening, punching and forced sexual intercourse are other types with similar percentages of 2.1 (3/143).

Table 3.

Type of IPV by husband

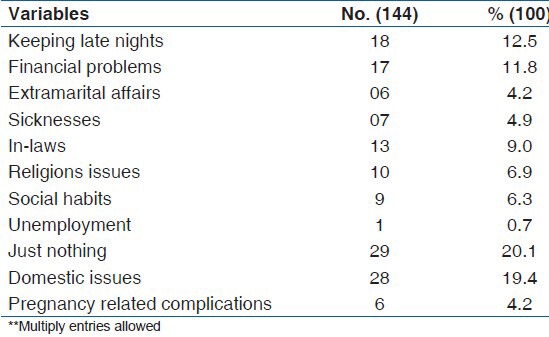

Possible causes of IPV during pregnancy is shown in Table 4. Reasons for IPV was not identified in 20.1% (29/144) of cases. However, the definite variable that was noted to be the commonest cause of IPV was domestic problems like dirty environment, not cooking good food, and not caring for the husband and children (19.4%) 28/144. This was followed by late nights (12.5%) 18/144 and financial problems (11.8%) 17/144. The least cause was unemployment in 0.7% (1/144). Pregnancy related complications and extramarital affairs had same contribution of 4.2% (6/144).

Table 4.

**Causes of intimate partner violence

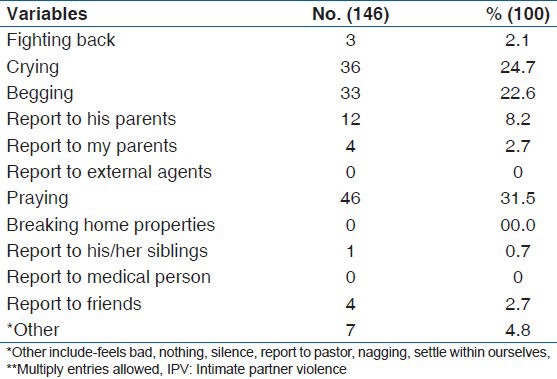

Table 5 shows the reactions by pregnant women following the IPV.

Table 5.

**Reactions by wife to IPV

Majority of the woman resorted to praying (31.5%) 46/146 as their reactions to the IPV by their Husband. This was followed closely by other reactions like crying (24.6%) 36/146 and begging (22.6%) 33/146. Others will report to Husbands parents (8.2%) 12/146, friends (2.7%) 4/146, their parents (2.7%) 4/146, siblings (0.7%) 1/146. No one reported to police or broke household properties. Other reactions (4.8%) 7/146 included feels bad, silence, nagging, report to pastor and settle within themselves.

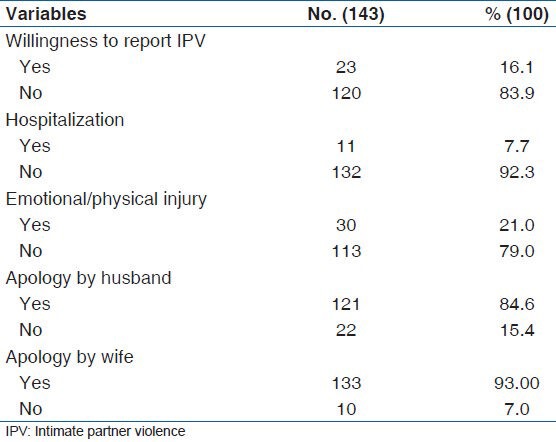

Table 6 shows burden/consequences of IPV during pregnancy.

Table 6.

Burden/consequences of IPV on women during pregnancy

Eleven (7.7%) 11/143 were hospitalized following IPV during pregnancy. Thirty (21%) 30/143 had physical and or emotional injuring. A high percentage (84.6%) 121/143 of husbands apologized to their wife after an IPV though a greater percentage (93%) 133/143 of women readily apologized to their husband. Very few women 23 (16.1%) 23/143 are willing to report to Law enforcement agencies not minding the degree of impact of IPV on them.

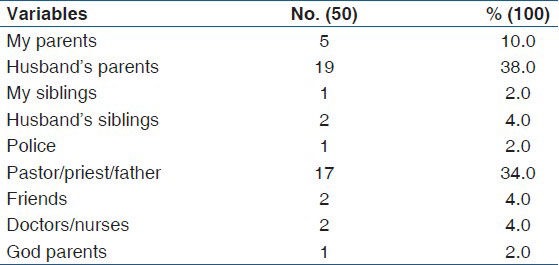

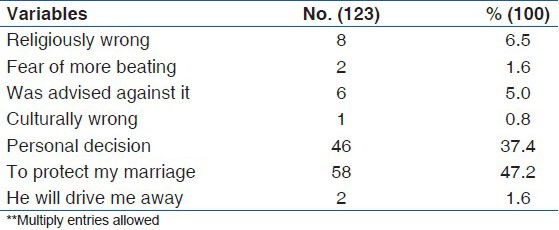

Table 7 shows those reported to (a) and reasons for not supporting (b) reporting IPV.

Table 7a.

Supports reporting to the following

Table 7b.

**Reasons for not supporting report

Among those willing to report a case of IPV, 38% (19/50) supports reporting to Husband's parents while only 10% (5/143) will report to their own parents. A significant percentage (34%) 17/50 will report to pastors, priests or Reverend Fathers. Only 4% (2/50) will report to friends, Doctors, Nurses, and Husband's siblings.

Majority of the respondents (47.2%) 58/123 do not support reporting IPV so as to protect their marriage. Another significant reason is personal decision (37.4%) 46/123. Fear of more beating and fear of being driven out of the house accounted for 1.6% (2/123) each while the least reason (0.8%) 1/123 was based on being culturally wrong. Religiously wrong and having been advised against it were other reasons given accounting for 6.5% (8/123) and 5.0% (6/123), respectively.

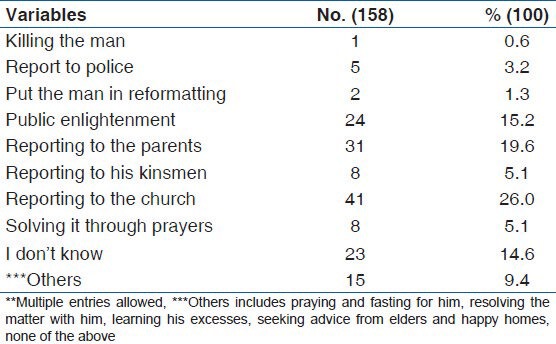

Table 8 illustrates suggestions by the respondents on the solutions to IPV. The highest number of respondents (26.0%) 41/158 suggested reporting to the Church. This was followed by reporting to the parents (19.6%) 31/158 and public enlightenment (15.2%) 24/158. The least suggestions of (0.6%) 1/158 was killing the man and (1.3%) 2/158 suggested admitting the man into reformatory. Twenty three (14.6%) 23/158 do not know any suggestion that could eliminate or ameliorate IPV.

Table 8.

**Suggestions on solutions to domestic violence

Others accounted for 9.4% (15/158) while the remaining suggestions are handling it by prayers and reporting to kinsmen each of (5.1%) 8/123, and reporting to police (3.2%) 5/123.

Discussion

Violence pervades the lives of many people around the world and touches all of us in some ways. To many people, staying out of violence's pathway is a matter of locking doors-and-windows and avoiding dangerous places. To others escape is not possible. The threat of violence is behind those locked doors and windows, well hidden from the public view.[18] The 44.6% (14300/321) prevalence of IPV found in this study supports the above view. This is quite high but is within the range of 11.5-79% seen in different parts of Nigeria.[5,6,7,8] It is higher than similar studies done in Nigeria by Fawole, et al. 2.3% in Abeokuta,[19] 11% by Ikeme and Ezegwui, et al. in Enugu,[7] 13.6% by Umeora, et al. in Abakaliki,[20] and 28% by Ameh and Abdul in Zaria.[10] The high prevalence rate in this study may be because the respondents were well motivated, and were taken into a separate apartment to complete the questionnaires. So they had no fear of stigmatization, or exposing the family affairs to the public. However, the actual prevalence may even be higher than this because some of them may still have fear of more violence, stigmatization and or even cultural perceptions of accepting IPV as a means of chastising or correcting an erring wife.[5,21] In addition some of the respondents are still in their early pregnancies as such may still have IPV in the course of their current pregnancy.

Most of the victims of IPV in this study were pregnant women with no formal education, in polygamous setting and those with long duration of marriage > 6 year as well as those < 20 years old. Age of the pregnant woman, family setting, and educational level of the couple were noted to have significantly influenced IPV in this study. This is in consonance with the findings in studies done in Enugu,[7] and Zaria.[10] However, some other findings noted that IPV is commoner in adolescents and women ≥ 40 year.[5,20] Our finding on influence of education on IPV is in line with other previous studies by showing that women who were less educated had higher odds of abuse during pregnancy than more educated women.[1,20] Housewives and student were common victims of IPV in this study and are unemployed. Unemployment results in lack of financial independence and this may be the reason why IPV is higher among housewives who have no other source of income besides their husbands. When demands of money for family upkeep are made and the man is unable to meet such demands it may breed unhappiness and may ignite misunderstanding, misconception and then IPV. The man on the other hand may have one of the social habits as a means of coping with his meager income. Social habits influenced IPV in this study. It is worthy of note that salaries are always not enough to cater for the family upkeep as minimum wage is ≤N7500, which is approximately equal to or even less than $50.[5] This is far less than the MDG expectation of at least $1 per day for an individual. Most of the time, the man has other dependent extended family members with aged parents and parents-in-laws as well as a large nuclear family. Grandmultiparity is also a common finding in most developing countries and may be an initiator of IPV. In this study IPV was commonest among grandmultiparas and parity significantly influenced IPV.

The most common reason for IPV in this study was unidentifiable cause (not disclosed). This supports the facts that women are generally reluctant to disclose IPV because of the feeling of self shame, loyalty to Husbands, fear of stigmatization as well as cultural norms documented in similar studies.[5,8,21,22] Even when they accept having suffered IPV it is still difficult for them to categorically state the cause. Furthermore domestic issues were the next most common identified cause of IPV. This is still as vague as the aforementioned no identifiable cause (just nothing). Few identified husbands late nights, financial problems, in-laws, religious issues, social habits, extramarital affairs among others as the causes of IPV during pregnancy.

Most of the victims of IPV were abused verbally and shouted down by their perpetrators. This is different from findings in some African studies where beating up, forced sexual intercourse and having object thrown at them were the common findings.[7,10,22] However, this finding is in conformity with the report of Umeora, et al. in Abakaliki.[20]

IPV historically has been viewed as a private family matter that needs not involve the government or criminal justice.[23] Of all the victims of IPV in this study none reported the case to Law enforcement agencies. Non-reporting of IPV is also enforced by male dominance, patriarchal system of family setting, cultural norms, fear of stigmatization and religious beliefs.[7,11,21,22] In this study there was a significant association between religion and IPV. Most women will resort to praying, crying and begging as was seen in this study.[5,23] This is done to protect their marriage, to prevent their children from suffering from neglect and abuse and to maintain their source of income.[5,23] When IPV is reported it is made to the family members like the parents, siblings and close friend. This is because marriage in our setting is seen as a family affair rather than a public or private affair.[5] This was further buttressed in this study by the fact that only 16.1% (2300/143) of the abused accepted that IPV should be reported to Law enforcement agencies.

The consequences of IPV abound, with increased risk to feto-maternal outcome. The IPV increases risk of an adverse pregnancy outcome and may even extend to the child at or after delivery.[6,21,22] In this study 7.7% (1100/143) were hospitalized while 21% (3000/143) sustained emotional and physical injury following IPV. IPV has been shown to be a traumatic experience by many studies with associated mental disturbances.[23] Studies have shown that women who had IPV exhibit different emotional or psychiatric problems such as depression, general anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as drug and alcohol dependence.[23,24,25] Other psychiatric disorders seen in IPV include borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.[13,21,24]

Lenore Walker presented the model of cycle of abuse of Tension building phase, to the violent phase and finally the Honeymoon phase. The honeymoon phase is characterized by affection, apology and apparent end of violence. Apology was given by (84.6%) 21200/143 of the perpetrators as against (93.30%) 13100/143 of the victims of IPV. These may mark the end of IPV and the return of love and affection and is more advocated by the victims of IPV. However, even the more pleasant behaviors’ of Honeymoon phase may serve to perpetuate the IPV.

IPV is a source of worry to the populace and is still very persistent not minding the concerted effort on ways of eliminating violence against women. Suggestions on solution to IPV by pregnant women in this study showed that reporting to family members and churches are significant ways of curbing the abuse. This is mainly because of the pedigree of the institution of marriage in this part of country. There is a strong religious and or cultural tie in family setting in Nigeria. Besides these, there is also the quest to protect the marriage and children as well as the fear of reprisals, loss of shelter and stigmatization. Public enlightenment was also a major suggested solution to IPV. Public enlightenment has been advocated globally by many agencies and organization.[2,21] In-fact the WHO, Non-Government Organization and other agencies have called on countries to take appropriate measures to prevent violence agent women.[2,21]

Conclusion

The burden of IPV is quite worrisome especially in the African setting where the act is concealed by the victims. This attitude of non-reporting of IPV is enshrouded in our cultural patriachalism, religious beliefs and perception of family institution as sacred. All these help to perpetuate reproductive ill-health and degrade the status of the women in our setting.

Recommendation

Attitudinal change is paramount to eliminating IPV and this could be achieved by empowering women and promoting gender equality as was prescribed by MDG. Other means of attitudinal change could be through education, advocacy, public enlightenment, male involvement and involvement of the judiciary.

Screening for IPV should be included in the curriculum of health care especially in the antenatal care. This will help in identifying, evaluating, counseling and offering immediate solutions to victims. Support group formation will also help in follow up and reporting of intractable cases to external agents. IPV should be made a punishable offence enacted into the constitution so as to deter perpetrators from such act.

AKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to acknowledge the management of Federal Medical Centre Abakaliki for allowing us to use her patients in this research work. we are also grateful to the research assistants and all those that assisted in the secretariat work as well as the data analysis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Hammoury N, Khawaja M, Mahfoud Z, Afifi RA, Madi H. Domestic violence against women during pregnancy: The case of Palestinian refugees attending an antenatal clinic in Lebanon. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:337–45. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. World Health Organization (1997). Violence against women: The priority health issue. Reproductive health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heise L, Pitangury J, Germain A. Washington DC: World Bank; 1994. Violence against women: The hidden health burden. World bank discussion paper, No. 255. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Bruyn M. Violence related to pregnancy and abortion: A violation of human rights. Sex Health Exch. 2002;3:14–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fawole OI, Aderonmu AL, Fawole AO. Intimate partner abuse: Wife beating among civil servants in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9:54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aimakhu CO, Olayemi O, Iwe CA, Oluyemi FA, Ojoko IE, Shoretire KA, et al. Current causes and management of violence against women in Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:58–63. doi: 10.1080/01443610310001620314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeme AC, Ezegwui HU. Domestic violence against pregnant Nigerian women. Trop J Obstet Gyeacol. 2003;20:116–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okemgbo CN, Omideyi AK, Odimegwu CO. Prevalence, patterns and correlates of domestic violence in selected Igbo communities of Imo State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2002;6:101–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shamu S, Abrahams N, Temmerman M, Musekiwa A, Zarowsky C. A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: Prevalence and risk factors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ameh N, Abdul MA. Prevalence of domestic violence amongst pregnant women in Zaria, Nigeria. Annals Afr Med. 2004;3:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezechi OC, Kalu BK, Ezechi LO, Nwokoro CA, Ndububa VI, Okeke GC. Prevalence and pattern of domestic violence against pregnant Nigerian women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:652–6. doi: 10.1080/01443610400007901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cokkinides VE, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Addy C, Bethea L. Physical violence during pregnancy: Maternal complications and birth outcomes. J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:661–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen R, Gazmararian JA, Spitz AM, Rowley DL, Goodwin MM, Saltzman LE, et al. Violence and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:366–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avery-Leaf S, Cascardi M. Dating violence education prevention and early intervention strategies. In: Schewe PA, editor. Preventing Violence in Relationships: Intervention Across the Life Span. Washington DC, USA: Am Psych Assoc; 2002. pp. 79–105. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;23:1023–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996;275:1915–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ameh N, Shittu SO, Abdul MA. Risk scoring for domestic violence in pregnancy. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BrundtLand GH. Preface. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg U, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fawole AO, Hunyinbo KI, Fawole OI. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:405–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umeora OU, Dimejesi BI, Ejikeme BN, Egwuatu VE. Pattern and determinants of domestic violence among prenatal clinic attendees in a referral centre, South-east Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:769–74. doi: 10.1080/01443610802463819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibekwe PC. Preventing violence against women: Time to uphold an important aspect of the reproductive health needs of women in Nigeria. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007;33:235–6. doi: 10.1783/147118907782101760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Worku A, Addisie M. Sexual violence among female high school students in Debark, north west Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2002;79:96–9. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i2.8911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avdibegović E, Sinanović O. Consequences of domestic violence on women's mental health in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croat Med J. 2006;47:730–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moracco KE, Brown CL, Martin SL, Chang JC, Dulli L, Loucks-Sorrell MB, et al. Mental health issues among female clients of domestic violence programs in North Carolina. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1036–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houry D, Schultz RM, Rhodes K, Kellermann AL, Kaslow NJ. Mental health symptoms and intimate partner violence. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:141. [Google Scholar]