Occurrence of a CSF-1 receptor-dependent monocyte differentiation process driven by IL-34, but not CSF-1.

Keywords: follicular dendritic cells, mouse spleen, CD11b

Abstract

With the use of a mouse FDC line, FL-Y, we have been analyzing roles for FDCs in controlling B cell fate in GCs. Beside these regulatory functions, we fortuitously found that FL-Y cells induced a new type of CD11b+ monocytic cells (F4/80+, Gr-1−, Ly6C−, I-A/E−/lo, CD11c−, CD115+, CXCR4+, CCR2+, CX3CR1−) when cultured with a Lin−c-kit+ population from mouse spleen cells. The developed CD11b+ cells shared a similar gene-expression profile to mononuclear phagocytes and were designated as FDMCs. Here, we describe characteristic immunological functions and the induction mechanism of FDMCs. Proliferation of anti-CD40 antibody-stimulated B cells was markedly accelerated in the presence of FDMCs. In addition, the FDMC-activated B cells efficiently acquired GC B cell-associated markers (Fas and GL-7). We observed an increase of FDMC-like cells in mice after immunization. On the other hand, FL-Y cells were found to produce CSF-1 as well as IL-34, both of which are known to induce development of macrophages and monocytes by binding to the common receptor, CSF-1R, expressed on the progenitors. However, we show that FL-Y-derived IL-34, but not CSF-1, was selectively responsible for FDMC generation using neutralizing antibodies and RNAi. We also confirmed that FDMC generation was strictly dependent on CSF-1R. To our knowledge, a CSF-1R-mediated differentiation process that is intrinsically specific for IL-34 has not been reported. Our results provide new insights into understanding the diversity of IL-34 and CSF-1 signaling pathways through CSF-1R.

Introduction

GCs are critical microenvironments where antigen-stimulated B cells differentiate into plasma or memory cells after undergoing SHM and class-switch recombination in their Ig genes [1–3]. B cells and IL-21-producing follicular Th cells that were activated in an antigen-specific manner accumulate around the network of FDCs to form GCs [4, 5]. After undergoing SHM, only B cell clones that acquired high-affinity BCRs are positively selected through interaction with antigens trapped on FDCs as immune complexes [5–7]. This leads to the production of high-affinity antibodies in the course of antibody responses, a process termed affinity maturation [2–7]. Thus, FDCs have been shown to play vital roles in controlling B cell differentiation in GCs.

To investigate further roles for FDCs in regulating antibody responses, we have established a FDC-like cell line, FL-Y, from popliteal LNs of immunized BALB/c mice [8, 9]. A characteristic feature of FL-Y cells is that their viability and proliferation are dependent on LTβR-mediated signaling and TNF-α, both of which are essential for sustaining FDC networks in vivo [10, 11]. In addition, we have reported that FL-Y cells retain a number of FDC-associated phenotypic markers, including expression of CD21, milk fat globule-EGF 8 protein, FcγRII, and B-cell activating factor; retention of complement component C4 on their surface; efficient support of B cell viability in vitro; and markedly inducing GC B cell markers (GL-7 and Fas) in cocultured B cells [8]. With the use of FL-Y cells, we have reported recently that PGE2 secreted from FDCs induced apoptotic cell death in GC B cells that were exposed to IL-21 in the absence of stimulation through CD40, thus implicating a novel function of FDCs in contributing to the negative selection of GC B cells [12]. These data suggest that FL-Y cells are a useful model cell line to study FDCs in vitro.

Here, we report another aspect of the function of FL-Y cells, implicating a new role for FDCs. We show that coculture of FL-Y cells with Lin−c-kit+ mouse spleen cells resulted in the generation of a new class of CD11b+ myeloid cells that may have a role in regulating B cell differentiation in GCs. Phenotypes of the developed cells were unique in that they expressed CD11b, F4/80, CD115, CCR2, and CXCR4 but were negative for Gr-1, Ly6C, CX3CR1, CD11c, and MHC class II. Microarray analysis of the gene-expression profile revealed that the cells belong to a mononuclear phagocyte Lin. Thus, we tentatively designated the induced CD11b+ cells as FDMCs.

Our analysis of the mechanism of FDMC development and its immunological functions led us to the following novel findings. Firstly, although FL-Y cells produced IL-34 and CSF-1 (also known as M-CSF), only IL-34 was effective in inducing FDMCs in a CSF-1R-dependent fashion. IL-34 was identified recently as a predicted second ligand for CSF-1R [13], although it does not share obvious amino acid sequence homology with CSF-1 [14, 15]. IL-34 and CSF-1 have been reported to show redundant activities in developing myeloid cells, including mononuclear phagocytes and osteoclasts from the BM precursors [15–18]. However, these two cytokines have been reported to show differential expression pattern in various tissues [18]. It has been controversial as to whether IL-34 and CSF-1 have nonoverlapping functions, respectively [19, 20]. Recently, reports from two groups of investigators have shown that disruption of the IL-34 gene in mice resulted in selective loss of Langerhans cells and microglia [21, 22]. A similar phenotype is observed in CSF-1R-deficient mice but not in CSF-1-deficient (CSF-1op/op) mice, suggesting involvement of an alternative ligand for CSF-1R in these defects [20, 23, 24]. These studies reported that IL-34-dependent development of Langerhans cells and microglia was a result of the spatiotemporal difference between IL-34 and CSF-1 expression in the microenvironments that support their development—rich in IL-34 but poor in CSF-1 [21, 22]. However, whether the CSF-1R expressed in the progenitors of these two types of cells is exclusively responsive to IL-34 has remained unclear in these studies. Here, we present several lines of evidence showing that the CSF-1R-mediated development of FDMCs in vitro was intrinsically dependent on IL-34 but not CSF-1. In addition, we examined immunological significance of FDMCs in comparison with previously reported CD11b+ myeloid Lin cells [17, 25].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Male BALB/c mice were purchased from Japan Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Kanagawa, Japan). CSF-1R-deficient mice (CBF1 background) were generated as reported previously [13]. All mice were treated in accordance with the guideline approved by the Committee of Laboratory Animal Care, Okayama University, and usually used at 7–12 weeks of age.

Antibodies, cytokines, and other reagents

Antibodies and other reagents used for flow cytometric analyses are as follows: FITC-anti-Gr-1, FITC-anti-I-Ad, FITC-anti-ScaI, FITC-anti-IgD, PE-anti-Ly6G, PE-anti-CD138, allophycocyanin-anti-CD11b, biotin-anti-Ly6C, biotin-anti-c-kit, FITC-anti-GL-7, PE-anti-Fas, PE-anti-CXCR4, and biotin-anti-CD138 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); rat anti-mouse CD115 (CSF-1R; clone AFS98) and biotin-F4/80 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA); PE-anti-Lin markers cocktail (anti-CD3e, anti-Ly6C/6G, anti-CD11b, anti-B220, anti-TER-199), PE-anti-CD11b, PE-anti-CD115 (CSF-1R), biotin-anti-CD11c, Pacific blue-B220, PE-B220, and Pacific blue-anti-CD3 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA); purified sheep anti-mouse IL-34 and rat anti-mouse CSF-1 (clone 131614; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA); streptavidin-FITC and PE-anti-sheep IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA); mouse rIL-4 and rCSF-1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA); and mouse rIL-34 and rIL-21 (R&D Systems).

Culture medium

All cells in the present work were cultured in the culture medium that consisted of a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FCS and 10−5 M 2-ME.

Culture of FL-Y cells

A mouse FDC line, FL-Y, was established in our laboratory from the long-term culture of primary FDCs derived from immunized BALB/c mice, as described previously [8]. FL-Y cells were cultured in the culture medium in the presence of 5 ng/ml TNF-α (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Where indicated, an agonistic anti-LTβR mAb (Serotec, Oxford, UK) was added at 2.5 μμg/ml to enhance the growth rate and gene expression. In some experiments, EGFP-expressing FL-Y was used, which was generated by retroviral transfer of the EGFP gene, as described previously [12].

FDMC induction culture

Each well in 24-well culture plates was coated with 5 × 103 EGFP+ FL-Y cells by incubating the cells overnight in 1 ml of the culture medium containing 5 ng/ml TNF-α. After removing the culture medium, 2 × 105 TBA-SCs in 1 ml of the culture medium were added into each FL-Y-coated well. The cells were cultured at 37°C under humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. TBA-SCs were prepared from BALB/c spleen cells by lysing RBCs and removing adherent cells by panning with plastic culture plates, followed by depleting T cells and B cells using Dynabeads Mouse Pan T (B220) and Mouse Pan B (Thy1.2), respectively (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After culture for 7–9 days, FDMCs (CD11b+EGFP−) were purified from the harvested cells by a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

In experiments using neutralizing antibodies, each antibody was added at indicated concentrations on Days 0 and 4 of the culture. Viable cells were enumerated by trypan blue dye exclusion, and the number of CD11b+ cells was estimated by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Cultured cells were treated with 10 μg/ml rat IgG at 4°C for 15 min and subsequently stained with labeled antibodies or their isotype-matched control antibodies in PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA and 0.1% (w/v) sodium azide at 4°C for 30 min. After washing, labeled cells were analyzed on the FACSCalibur or FACSAria (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). To obtain purified FDMCs, the cells that were harvested from FDMC induction culture were stained with the PE-anti-CD11b antibody, and the CD11b+GFP−-gated population was isolated using a FACSAria cell sorter. The purity of CD11b+ cells in the sorted preparation was >95%.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA sample was prepared from 1 × 106 purified FDMCs using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's indication, and used for the preparation of targets for Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). CEL files were generated by the Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console. Network analysis of genes expressed by various cell types was performed as described previously [9]. Briefly, FDMC microarray data were combined with a large collection of other cell- and tissue-specific gene-expression data sets (205 individual data sets, including FL-Y cells), available from the GEO database on the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array platform. Raw data (CEL files) were normalized using Robust Multichip Analysis (RMAExpress; http://rmaexpress.bmbolstad.com/), annotated using the latest libraries available from Affymetrix and arranged according to cell-type grouping. These normalized, nonlog-transformed gene-expression data were then imported into BioLayout Express3D (www.biolayout.org), a tool designed specifically for the visualization of large gene-expression network graphs [26]. A network graph was created using a Pearson correlation coefficient cut-off threshold of r = 0.80. The network was then clustered into groups of genes sharing similar profiles using the Markov clustering algorithm at an inflation value of 2.2. The graph of these data was then explored to understand the significance of the gene clusters and the functional relationships of FDMCs to other cell populations [9, 26–28]. The microarray data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information's GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), under Accession Number GSM1112078.

Phagocytosis assay

BMDCs were generated as reported previously [29]. Briefly, BM cells from BALB/c mice were depleted of T cells and B cells using Dynabeads Mouse Pan T and Mouse Pan B, respectively, and cultured for 6 days at 1 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FCS, IL-4 (10 ng/ml), and GM-CSF (10 ng/ml). On Days 2 and 4, the culture medium was exchanged with the fresh medium containing the same concentrations of IL-4 and GM-CSF. Nonadherent cells were collected on Day 6 of the culture and used as BMDCs. Phagocytotic activity of FDMCs or BMDCs was assessed using pHrodo Escherichia coli BioParticles conjugated for phagocytosis (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instruction. FDMCs or BMDCs were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well microplate and were incubated with the labeled E. coli particle for 3h at 37°C in the dark. Microscopic observation was done with a confocal laser-scanning microscope FV3000 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

qRT-PCR analyses

Total RNA samples were prepared from 1 × 105 FL-Y cells or FDMCs using TRIzol reagent. Each cDNA was prepared using Superscript II RT and oligo(dT) nucleotides (Invitrogen). The resultant cDNA was used in qRT-PCR using Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) on an iCycler iQ5 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR primers used for qRT-PCR are as follows: IL-34, 5′-CTTTGGGAAACGAGAATTTGGAGA-3′ and 5′-GCAATCCTGTAGTTGATGGGGAAG-3′; Csf-1, 5′-TCAACAGAGCAACCAAACCA-3′ and 5′-ACCCAGTTAGTGCCCAGTGA-3′; β-actin, 5′-AGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGTA-3′ and 5′-GCCAGAGCAGTAATCTCCTTCT-3′. All q-RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate.

KD of IL-34 or CSF-1 expression by RNAi

For silencing the il34 or the csf1 gene, we used the pcDNA6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR vector (Invitrogen), bearing an oligonucleotide sequence that encodes specific shRNA against IL-34 or CSF-1 mRNA. The IL-34- or CSF-1-specific shRNA sequences were generated using the BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer. The vector pcDNA6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR-neg, which bears a Scr, was used as a negative control vector. To KD the il34 or the csf1 gene in FL-Y cells, FL-Y cells were treated for 24 h with pcDNA6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR vector that was mixed with FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The stably transfected clones were selected in the culture medium containing 4 μg/ml blasticidin for 2–3 weeks, and individual isolated clones were examined for successful IL-34 or CSF-1 silencing by qRT-PCR and Western blot.

Western blotting

FL-Y cells were cultured with or without 2.5 μg/ml anti-LTβR mAb for 3 days. Cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (PBS containing 0.01% Triton X and 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail) and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses. Membranes were probed with a sheep anti-mouse IL-34 antibody or anti-mouse CSF-1 mAb. The antibody binding was detected using a combination of HRP-anti-sheep IgG or HRP-anti-rat IgG with ECL Prime (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Blots were stripped and reprobed against β-actin as a loading control.

Culture of B cells with FDMC

B cells (>95% pure) were prepared from spleen cells of BALB/c mice by removing RBCs and adherent cells, followed by T cell depletion using Dynabeads Mouse Pan T (Thy1.2; Invitrogen). To label purified B cells with CFSE, the B cells (2×107 cells/ml) were washed with PBS and incubated with CFSE at a final concentration of 2.5 μM at 37°C for 30 min. Then, the labeled cells were washed three times with the culture medium. B cells (1×106 cells/ml) were stimulated with an anti-CD40 mAb (0.5 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of FDMCs (1×105 cells/ml) in 1 ml of the culture medium for 3–4 days. Fluorescence intensity and expression of GC B cell-associated markers in cultured B cells were estimated by flow cytometry. Where indicated, IL-4 plus IL-21 (10 ng/ml or 30 ng/ml, respectively) were added to the culture in place of FDMCs.

In vivo analyses of FDMC-like cells

BALB/c mice were immunized i.p. with 100 μg TNP-KLH and 2 mg alum. After 12 days, TBA-SCs were prepared from immunized mice, as described above, and used for analyses of FDMC-like cells. TBA-SCs were treated with 10 μg/ml rat IgG at 4°C for 15 min and subsequently stained with fluorescence-labeled antibodies at 4°C for 30 min. The following antibodies were used: allophycocyanin -anti-CD11b, PE-anti-CXCR4, Pacific blue-anti-B220, Pacific blue-anti-CD3, FITC-anti-I-Ad, and FITC-anti-CD11c. The frequency of FDMC-like cells was estimated by measuring the percentage of CD11b+CXCR4+ cells in a B220−CD3−I-Ad−CD11c−-gated population on a FACSAria flow cytometer. To obtain purified FDMC-like cells, CD11b+CXCR4+B220−CD3−I-Ad−CD11c− cells were sorted from TBA-SCs using a FACSAria cell sorter.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± sem, and comparisons yielding P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant (Student's t-test). In some data where ses were not shown, they were <10% of the means from triplicate experiments.

RESULTS

Induction of FDMCs by coculture of precursor cells from mouse spleen with FL-Y cells

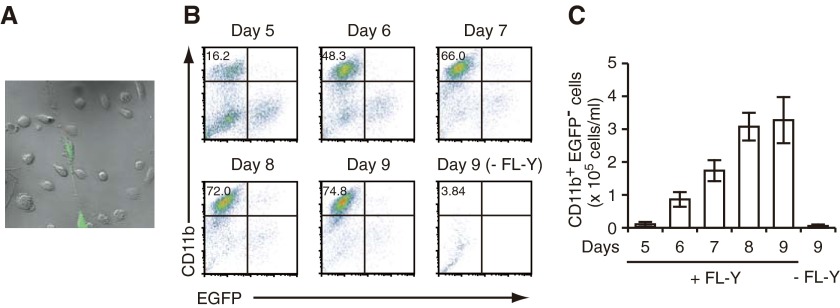

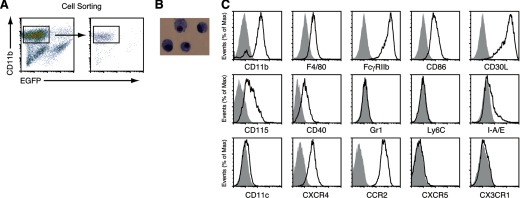

When we cultured T cell- and B cell-depleted mouse spleen cells with FL-Y cells in vitro, we often observed a substantial increase of CD11b+ monocytic cells after culture for 7–9 days. To characterize the increased CD11b+ cells, we cultured EGFP-expressing FL-Y cells with a non-B/non-T spleen cell preparation: TBA-SCs. We confirmed that the expanded CD11b+ monocytic cells (named FDMCs, as described above) did not express EGFP, indicating that FDMCs originated from precursors that had been contained in TBA-SCs (Fig. 1A and B). Induction of FDMCs was totally dependent on FL-Y cells and reached a plateau on Days 8–9 of the culture (Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1. Development of FDMCs in the coculture of mouse spleen cells with FL-Y cells.

TBA-SCs (2×105) from BALB/c mice were cultured with 2 × 103 EGFP-expressing FL-Y cells in 1 ml of the culture medium for 5∼9 days. The cultured cells were observed with a confocal laser-scanning microscope and analyzed by flow cytometry after staining CD11b. (A) Microscopic observation of expanded cells in the coculture of TBA-SCs with EGFP+ FL-Y cells (culture for 9 days). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of FDMC induction on each day during coculture of TBA-SCs with EGFP+ FL-Y cells. FDMCs were assessed as CD11b+EGFP− cells. The percentage of CD11b+EGFP− cells was indicated at the upper left in each panel. Note that CD11b+EGFP− cells were not induced in the absence of FL-Y cells (−FL-Y; lower right). (C) Time-course of the generation of FDMCs. The number of generated FDMCs in each culture was calculated from the percentage of CD11b+EGFP− cells in the total number of viable cells, as observed in B. Data are presented as the mean ± sem from triplicate cultures. Representative data from three repeated experiments.

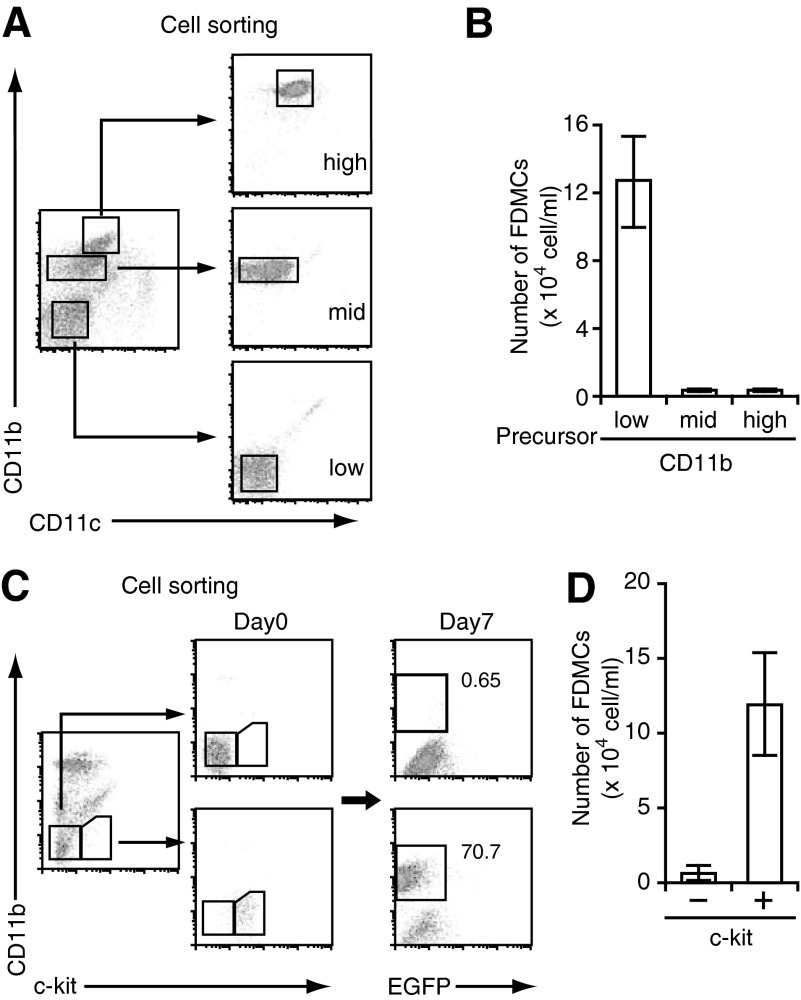

Analysis of the progenitor of FDMCs

To identify the progenitor of FDMCs, TBA-SCs were fractionated into three CD11c− populations, according to the expression level of CD11b, i.e., CD11blo, CD11bmid, and CD11bhi (Fig. 2A). When each sorted population (with the purity of >95%) was cultured with FL-Y cells for 9 days, FDMCs were generated exclusively from the CD11blo population (Fig. 2A and B). The CD11bhi and CD11bmid populations did not survive after coculture with FL-Y cells, thus ruling out that generation of FDMCs was not the result of expansion of pre-existed CD11b+ cells in the spleen cells. We further fractionated the CD11blo cells into c-kit+ and c-kit− populations and demonstrated that the former gave rise to FDMCs exclusively (Fig. 2C and D). FDMC generation similarly occurred when precursor cells were prepared by sorting as Lin−c-kit+ cells. The FDMC precursor cells appeared to be a very minor population that constituted <1% of the CD11blo cells in spleen (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. FDMCs were generated from c-kit+CD11b− cells in spleen.

(A) B220−CD3−CD11c−-gated spleen cells were sorted into CD11bhigh, Cd11bmid, and CD11blow populations by flow cytometry. (B) The same number of cells (2×105) from each sorted fraction was cultured with 2 × 103 EGFP+ FL-Y cells. Generation of FDMCs was assessed as indicated in Fig. 1B and C after culture for 9 days. (C) The CD11b− fraction in TBA-SCs was sorted into c-kit+ and c-kit− subsets. Cells from each subset (2×104) were cultured with EGFP+ FL-Y cells (2×103) for 7 days, followed by analysis of FDMC generation as in B. (D) The number of FDMCs generated from the culture of c-kit− or c-kit+ cells with EGFP+ FL-Y cells (experiments shown in C). Data are presented as the mean ± sem of triplicate cultures. Representative data from three repeated experiments.

Analysis of phenotypic markers and gene-expression profile in FDMCs

FDMCs were isolated from the induction culture by sorting the CD11b+GFP− population (Fig. 3A). These cells exhibited a mononuclear cell morphology (Fig. 3B). Flow cytometric analysis of isolated FDMCs showed that they were positive for F4/80, FcγRIIb, CD86, CD30L, CD115 (CSF-1R), CXCR4, CCR2, and CD40 but were negative or negligible for CD11c, Gr-1, Ly6C, I-A/Ed, CXCR5, and CX3CR1 (Fig. 3C). CD4 and CD8 were not positive either (data not shown). These phenotypic features suggest that FDMCs resemble Ly6CloGr-1− circulating, immature monocytes [30]. However, FDMCs were different from the blood monocytes, in that the latter cells have been reported to express a high level of CX3CR1 but are negative for CCR2 [30, 31]. We tested whether FDMCs respond to LPS plus IFN-γ or IL-4 plus GM-CSF to differentiate into mature-type macrophages or DCs, as reported for other immature myeloid cells [30, 32]. However, these stimuli induced expression of neither CD11c nor MHC class II in FDMCs (Supplemental Fig. 1A).

Figure 3. Flow cytometric analysis of surface markers on FDMCs.

(A) FDMCs were generated in the coculture of TBA-SCs with EGFP+ FL-Y cells for 9 days and purified by sorting as CD11b+EGFP− cells. (B) May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining of FDMCs. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of FDMCs after staining with each antibody to indicated surface markers. Negative controls that were stained with each isotype-matched control antibody are shown in gray.

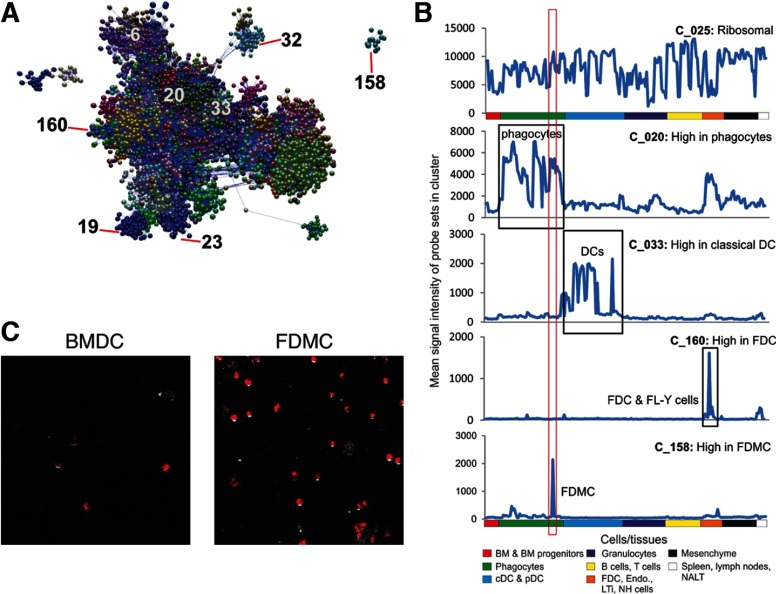

Next, the gene-expression profile of FDMCs was compared with that of many other immune cell Lin, including a range of mononuclear phagocyte Lin. The software tool BioLayout Express3D enables the visualization of a large number gene-expression data sets (microarray samples) at the same time as a network graph and to rapidly identify the relationships between data sets and the sets of genes that are robustly coexpressed across them [26, 27, 33]. Here, 23,447 probe sets (genes) were clustered using a Pearson correlation of r = 0.80 and Markov clustering algorithm of 2.2, generating 407 distinct clusters containing ≥7 probe sets (Fig. 4A). The network graph derived from these data is large, and its topology is complex. The graph's obvious structure is derived from the grouping of genes that are expressed in a specific manner, i.e., correlated in their expression profiles of >0.80, and are therefore connected by a large number of edges forming cliques within the network. Some of these clusters represent genes expressed in a cell-specific manner; others not (Fig. 4B). For example, Cluster 25 was enriched in ribosomal genes that were expressed highly by almost all cell populations. Cluster 160 contained 14 probe sets encoding genes expressed highly by FDC and FL-Y cells, including Cxcl13, mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1, and serine peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 1A. Cluster 20, in contrast, was enriched with 133 probe sets encoding genes known to be expressed highly by macrophages [28]. The genes in this cluster were expressed highly by all macrophage populations in this analysis but not by classical DCs (Fig. 4B). Our analysis showed that FDMCs also highly expressed the mononuclear phagocyte-related genes in Cluster 20 but not those with expression restricted to DC subsets (Cluster 33; Fig. 4A and B). We also found a small cluster of 15 probe sets (Cluster 158) encoding genes that were characteristically expressed highly in FDMCs alone (Fig. 4B and Supplemental Table 1). Noteworthy among them was expression of the uPA (Plau) mRNA at an extremely high level. In addition, FDMCs were shown to produce a limited number of cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-15, but not other B cell-stimulating cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-7, IL-13, and IL-21 (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 4. FDMCs shared a similar phenotype to mononuclear phagocytes.

(A) Network analysis of the 205 mouse cell and tissue gene-expression data sets using the tool BioLayout Express3D. This analysis enables the visualization of genes within a cluster across the entire data set. Genes with similar expression profiles are clustered together within the same region of the graph. Nodes represent transcripts (probe sets), edges represent correlations between individual expression profiles above r > 0.80, and the color of the nodes represent the cluster to which they have been assigned. The positions of representative clusters are annotated. (B) FDMCs share macrophage characteristics but not those of DCs. Five representative clusters derived from the network graph are shown and their mean probe set expression profiles across all data sets. The boxed area surrounded by a red line indicates the location of the FDMC data set; the black boxed areas show the location of the macrophage, classical DC (cDC), and FDC data sets. Cluster 25 is enriched in ribosomal genes that are expressed highly by almost all cell populations. Cluster 20 contains genes that are highly expressed by all of the phagocyte/macrophage populations. Cluster 158 represents genes specifically expressed in FDMCs. Genes in Cluster 33 were expressed specifically by classical DCs, whereas Cluster 160 was expressed highly by FDC (including FL-Y cells). pDC, plasmacytoid DC; Endo., endothelium; LTi, lymphoid tissue-inducer cells; NH, natural helper; NALT, nasal-associated lymphoid tissue. (C) Phagocytic activity of FDMCs compared with that of BMDCs. To compare phagocytic activity between FDMCs and BMDCs, these two types of cells were incubated with fluorescence-labeled E. coli particles for 2 h, as indicated in Materials and Methods.

Immunological functions of FDMCs

In accordance with the demonstration that FDMCs shared a phagocyte gene-expression profile, we observed that FDMCs actively phagocytosed fluorescently labeled E. coli particles actively (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, FDMCs did not function as APCs, as OVA-dependent proliferation of a Th clone, DO11.10, was induced in the presence of BMDCs but not FDMCs (Supplemental Fig. 1B). This is consistent with a negligible expression level of I-A/Ed molecules on FDMCs (Fig. 3C).

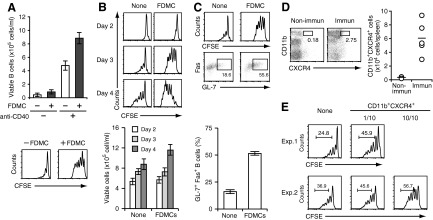

Next, to investigate effects of FDMCs on T cell and B cell functions, we cultured mouse B cells or T cells with FDMCs in vitro. When FDMCs were added to the culture of antigen-stimulated T cells, the T cell proliferation was inhibited only slightly (data not shown). In contrast, FDMCs showed characteristic augmenting effects on B cell proliferation. When FDMCs were added to the culture of B cells that were stimulated with a suboptimal concentration of an anti-CD40 mAb, B cell proliferation was accelerated markedly on Days 3–4 of the culture (Fig. 5A and B). FDMC alone did not show mitogenic effects on B cells in the absence of CD40 stimulation (Fig. 5A). Maximal enhancement was observed when the coculture was performed at the B cell:FDMC ratio of 10:1. FDMCs themselves did not increase their cell number during coculture but decayed gradually (data not shown). Although FDMCs markedly enhanced B cell proliferation, this was not reflected proportionally in the number of viable B cells after culture. The viability of B cells after coculture with FDMCs was only 15∼20% more than that observed in the absence of FDMCs (Fig. 5B). This may be a result of the fact that FDMC-stimulated, proliferating B cells were apt to die during culture. We observed a number of trypan blue dye-stained dead B cells in the coculture (data not shown).

Figure 5. Characterization of immunological functions of FDMCs in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Enhancement of proliferation of anti-CD40-stimulated B cells by the coculture with FDMCs. CFSE-labeled B cells (1×106/ml) were cultured with or without 0.5 μg/ml anti-CD40 mAb for 4 days in the presence or absence of FDMCs (1×105/ml) in 1 ml of the culture medium. The number of viable B cells after culture was calculated from the percentage of B220+ cells in the total number of viable cells (upper), and fluorescence intensities of cultured, CFSE-labeled B cells were measured by flow cytometry (lower). (B) Time-dependent enhancement of B cell proliferation by FDMCs. As indicated in A, CFSE-labeled B cells were stimulated with the anti-CD40 mAb in the presence or absence of FDMCs for 2, 3, or 4 days. Flow cytometric analysis of CFSE fluorescence intensity in cultured B cells (upper) and enumeration of viable B cells after culture for indicated days (lower) were performed as indicated in A. (C) Enhancement of GC B cell-associated marker expression in B cells that were cultured in the presence of FDMCs. CFSE-labeled B cells were cultured with or without FDMCs for 3 days as in A. CFSE fluorescence intensity and percentage of GL-7+Fas+ cells in B220-gated cells were estimated by flow cytometry (upper). Data from flow cytometric analyses were presented as histograms (lower). Data are presented as the mean ± sem from triplicate cultures. Representative data from two or three repeated experiments. (D) Increase of FDMC-like cells in immunized mice. A group of BALB/c mice (n=5) was immunized with TNP-KLH. Another group of mice was left nonimmunized as negative controls. On Day 12 after immunization, the frequency of FDMC-like cells was estimated by detecting CD11b+CXCR4+ cells in the CD3−B220−I-Ad−CD11c−-gated population in the spleen cells from each mouse. Representative flow cytometry diagrams from immunized (Immun) and nonimmunized (Non-immun) mice are shown (left). (E) Enhancement of B cell proliferation by FDMC-like cells isolated from immunized mice. CD3−B220−I-Ad−CD11c−CD11b+CXCR4+ FDMC-like cells were sorted from the pooled spleen cells of immunized mice. CFSE-labeled B cells were cultured with the anti-CD40 mAb in the presence or absence of the sorted FDMC-like cells (CD11b+CXCR4+), as described in A. FDMC-like cells were added at one of 10 or 10/10 of the number of input B cells as indicated. Two representative results (Exp. 1 and Exp. 2) are shown.

The above experiments showed that FDMCs markedly accelerate proliferation of anti-CD40-stimulated B cells. Rapid turnover of the cell cycle is one of the characteristic features of GC B cells, particularly centroblasts that are present in the dark zone of GCs [1, 2]. Thus, we investigated whether B cells that rapidly proliferated in the presence of FDMCs acquired GC B cell-associated markers. The proportion of B cells expressing Fas and GL-7 was increased by 1.5 to approximately twofold when anti-CD40-stimulated B cells were cultured with FDMCs for 3 days compared with those cultured in its absence (Fig. 5C).

To confirm further the immunological significance of FDMCs, we explored whether FDMC-like cells occurred in vivo by comparing the frequency of CD3−B220−I-Ad−CD11c−CD11b+CXCR4+ cells between immunized and unimmunized mice. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that a significant increase of a CD11b+CXCR4+ population was observed in the CD3−B220−I-Ad−CD11c−-gated spleen cells after immunization (Fig. 5D). We observed a similar increase of FDMC-like cells in immunized mice when the analysis was made by using another criterion, CD3−B220−I-Ad−CD11c−CD11b+CD30L+ (data not shown). Next, the increased CD11b+CXCR4+ cells were sorted from the CD3−B220−I-Ad−CD11c− fraction of immunized spleen cells and examined for their B cell-stimulating activities. Results showed that the sorted CD11b+CXCR4+ FDMC-like cells had enhancing effects on the proliferation of anti-CD40-stimulated B cells (Fig. 5E). We also confirmed that the coculture of anti-CD40-stimulated B cells with the FDMC-like cells resulted in an increase of GL-7+Fas+ B cells by approximately twofold (data not shown). These findings suggest that the sorted population contained a likely in vivo counterpart of FDMCs. Taken together, FDMCs are unique as monocytic cells, in that they had stimulating effects on B cell proliferation and differentiation.

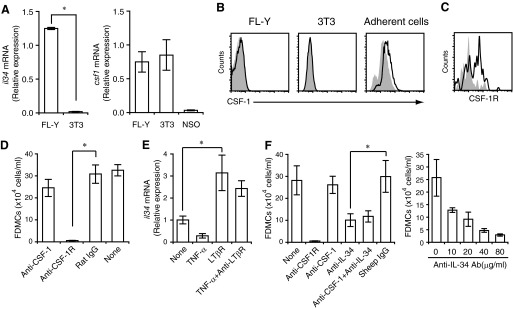

Dependence of FDMC generation on FL-Y-derived IL-34 but not CSF-1

To identify factor(s) that are responsible for FL-Y-induced FDMC generation, we first examined whether FL-Y cells expressed CSF-1, which plays a vital role in the development of monocyte/macrophage Lin cells [17]. We found that FL-Y cells expressed the CSF-1 mRNA and protein at comparable levels with those in a mouse fibroblastic cell line, NIH3T3, which was selected as a positive control (Figs. 6A and 7C). It has been shown that the CSF-1 molecules are produced as secreted and as membrane-spanning, cell-surface isoforms in various tissues [16, 19, 34, 35]. However, it has been reported that NIH3T3 cells do not express cell-surface CSF-1 [36], and our flow cytometric analysis confirmed this previous observation (Fig. 6B). The cell-surface CSF-1 was also undetectable on FL-Y cells (Fig. 6B), suggesting that they similarly almost entirely express the secreted CSF-1 isoforms. On the other hand, we found that FL-Y cells, but not NIH3T3 cells, produced IL-34, which was recently discovered as the second ligand for CSF-1R [14] (Figs. 6A and 7C). In addition, the Lin−c-kit+ precursor cells of FDMCs were found to express CD115/CSF-1R (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Development of FDMCs specifically depends on IL-34 that is produced from FL-Y cells.

(A) Expression of csf1 and il-34 mRNA in FL-Y and NIH3T3 (3T3) cells. NSO, Mouse plasmacytoma cell. (B) Absence of the membrane-bound form of CSF-1 on FL-Y and 3T3 cells. FL-Y cells (left) and 3T3 cells (middle) were stained with anti-CSF-1 mAb (lines) or an isotype-matched control antibody (shaded histograms), respectively. As a positive control, an adherent cell population prepared from the spleens of BALB/c mice (right) was stained similarly. (C) CSF-1R expression on Lin−c-kit+ FDMC precursor cells. TBA-SCs prepared from nonimmunized BALB/c mice were stained with anti-Lin marker, anti-c-kit, and anti-CD115 (CSF-1R) antibodies. The Lin−c-kit+-gated population was analyzed for expression of CSF-1R. Shaded histogram represents the staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. (D) Inhibition of FDMC generation by blockade of CSF-1R but not that of CSF-1. FDMC induction cultures were carried out as described in Fig. 1 in the presence or absence of 20 μg/ml indicated neutralizing antibodies. Isotype-matched control antibody (rat IgG) was added as a negative control. (E) Expression of il-34 mRNA in FL-Y cells. Cells were unstimulated or stimulated with TNF-α and/or an anti-LTβR mAb, as indicated for 48 h. The level of the il-34 mRNA was determined by qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to β-actin mRNA and presented as values relative to that in unstimulated FL-Y. (F) Inhibition of FDMC generation by a neutralizing anti-IL-34 antibody. Each indicated neutralizing antibody was added at 20 μg/ml to the FDMC induction culture (left). (Right) Varying concentrations of the anti-IL-34 antibody were added to the culture. Sheep IgG was added as an isotype-matched negative control. Data were presented as the mean ± sem from triplicate cultures. *Statistically significant difference (P<0.05). Representative data from three repeated experiments.

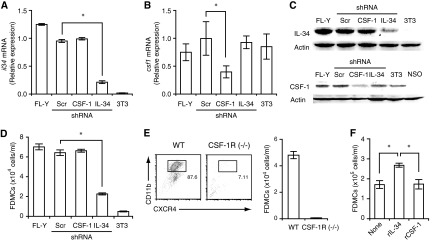

Figure 7. Further confirmation of dependence of FDMC generation on IL-34 and CSF-1R.

(A) Generation of the IL-34-KD strain of FL-Y. FL-Y cells were stably transfected with an IL-34-specific shRNA expression vector. As negative controls, FL-Y cells were transduced with a mock (Scr) vector or a CSF-1-specific shRNA expression vector. The il-34 mRNA level in each strain was assessed by qRT-PCR. NIH3T3 cells were used as an IL-34-negative control. Data were normalized to the level of β-actin mRNA. (B) The csf1 mRNA expression was reduced in the CSF-1-KD strain but not in the IL-34-KD strain. Data were normalized to the level of β-actin mRNA. (C) The IL-34-KD and the CSF-1-KD in FL-Y cells specifically reduced the IL-34 protein (upper) and the CSF-1 protein (lower), respectively. Cell lysates were prepared from FL-Y, the CSF-1-KD or the IL-34-KD cells, and analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was detected as loading controls. 3T3 and NSO cells were negative controls for expression of IL-34 and CSF-1, respectively. Only one major band is shown for the CSF-1 Western blot. (D) FDMC-inducing activity was abrogated in the IL-34-KD strain but not in the CSF-1-KD strain. Note that NIH3T3 cells that expressed CSF-1 but not IL-34 (as shown in A–C) did not induce FDMCs. (E) Inability of precursor cells from CSF-1R-deficient [CSF-1R (−/−)] mice to differentiate into FDMCs. The WT or CSF-1R-deficient precursor cells were cultured with FL-Y cells. Generation of FDMCs (CD11b+CXCR4+) was assessed by flow cytometry. (F) Improvement of the viability of FDMCs by IL-34 but not CSF-1. Purified FDMCs (5×105 cells/ml) were cultured for 2 days in the presence of rIL-34 (10 ng/ml) or rCSF-1 (10 ng/ml) and examined for the number of viable cells on Day 2. Data were presented as the mean ± sem from triplicate cultures. *Statistically significant difference (P<0.05). Representative data from two or three repeated experiments.

Thus, we first tested effects of a neutralizing anti-CSF-1 mAb on FDMC induction but observed no significant inhibitory effects (Fig. 6D). The neutralizing activity of the anti-CSF-1 mAb was confirmed by its inhibitory effects on CSF-1-dependent macrophage development from BM precursors (Supplemental Fig. 2). When cultured with mouse BM cells, CSF-1-producing NIH3T3 cells induced macrophage development, which was markedly inhibited by the anti-CSF-1 mAb that was used in the experiment of Fig. 6D. However, the same antibody again had no suppressive effects on FDMC induction (Supplemental Fig. 2). These data suggest that CSF-1 was not involved in FL-Y-induced FDMC generation.

However, FL-Y-induced FDMC generation was clearly abrogated when a blocking mAb to CSF-1R was added to the culture (Fig. 6D), suggesting that an alternative ligand for CSF-1R is involved in this process. IL-34, as well as CSF-1, has been shown to exert its biological activities by binding to CSF-1R [14]. Thus, we examined whether IL-34 was involved in FL-Y-induced FDMC generation using an anti-IL-34-neutralizing antibody.

Firstly, we investigated the expression pattern of IL-34 in FL-Y cells. We have reported that the growth of FL-Y cells in vitro is dependent on stimulation with TNF-α and an agonistic anti-LTβR mAb [8, 12]. Thus, we examined IL-34 expression in FL-Y cells that were cultured in the presence or absence of these stimuli. Unstimulated FL-Y cells expressed detectable levels of IL-34 mRNA, which was enhanced significantly when the cells were stimulated with an agonistic anti-LTβR mAb but not TNF-α (Fig. 6E).

We next examined whether the blockade of IL-34 abrogates FL-Y-induced FDMC development. Our data show that FDMC generation was inhibited markedly in the presence of an IL-34-neutralizing antibody in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 6F). In addition, a combination of the anti-CSF-1 mAb with the anti-IL-34 antibody did not augment blocking effects of the latter alone (Fig. 6F). On the other hand, NIH3T3 cells that produced CSF-1 but not IL-34 were not capable of inducing FDMCs in contrast to FL-Y cells that expressed IL-34 and CSF-1 (Figs. 6A and 7D). Taken together, these data suggest that FL-Y-derived IL-34 but not CSF-1 was responsible for FDMC induction.

Analysis of IL-34 dependence of FDMC generation by RNAi

To confirm further the IL-34 dependence of FDMC induction, we generated the IL-34-KD strain of FL-Y, in which IL-34 expression was silenced by transduction with IL-34-specific shRNA. IL-34 expression was reduced at mRNA and protein levels by >80% in the IL-34-KD strain, whereas transfection with Scr or CSF-1-specific shRNA had no significant effects on IL-34 expression (Fig. 7A and C). In addition, we confirmed that the IL-34 silencing did not significantly affect expression of CSF-1 in FL-Y cells (Fig. 7B and C). Consistent with these results, the ability to induce FDMCs was abrogated markedly in the IL-34-KD strain (Fig. 7D). On the other hand, we generated the CSF-1-KD strain of FL-Y, in which CSF-1 production was reduced to ∼¼ of that in the WT (Fig. 7C). We observed that FDMC generation with the CSF-1-KD strain, in contrast to the IL-34-KD strain, was not reduced significantly compared with the parental FL-Y (Fig. 7D). Collectively, these data further support that FL-Y-derived IL-34 but not CSF-1 is involved in FDMC generation.

Further analyses of critical roles for IL-34 and CSF-1R in FDMC generation

As IL-34 exerts its biological functions by signaling through CSF-1R [14], we examined whether FDMCs were generated from CSF-1R-deficient precursor cells. As anticipated, a precursor population prepared from the spleens of CSF-1R-deficient mice, in contrast to that from the WT, did not give rise to FDMCs in the coculture with FL-Y cells, thus indicating further a critical role for CSF-1R in FDMC development (Fig. 7E). Taken together, we conclude that FL-Y-induced FDMC generation from the precursor in spleen is mediated by a IL-34/CSF-1R-dependent signaling pathway.

As differentiated FDMCs still expressed CD115/CSF-1R (Fig. 3), we examined whether the CSF-1R retained the responsiveness to IL-34. For this, purified FDMCs were cultured with or without IL-34 or CSF-1. In the absence of these cytokines, the number of viable FDMCs was decreased to ∼1/3 of the initial input after 2 days. The addition of IL-34 but not CSF-1 improved the viability significantly, thus suggesting that CSF-1R expressed on FDMCs retains the selective responsiveness to IL-34 (Fig. 7F).

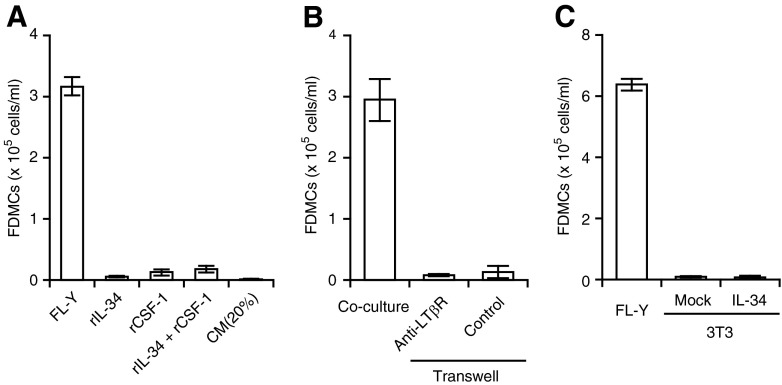

Although the blockade of IL-34 activity abrogated FDMC generation as described above, IL-34 alone is not considered to be sufficient for FDMC induction, as FDMCs were not generated when the precursor cells were cultured with mouse rIL-34 (Fig. 8A). Neither a FL-Y CM nor CSF-1 in combination with IL-34 was effective in inducing FDMCs (Fig. 8A). On the other hand, FL-Y cells were not capable of inducing FDMCs when they were physically separated by a transwell membrane (Fig. 8B). FDMC induction was not restored when an anti-LTβR mAb was supplemented to the transwell culture to enhance IL-34 production from FL-Y cells. Thus, in addition to IL-34, the contact between FL-Y cells and precursor cells is considered to be necessary for FDMC generation. Blocking antibodies to ICAM and VCAM that were highly expressed on FL-Y cells [8], however, did not inhibit FDMC induction by FL-Y cells (data not shown). In addition, FDMCs were not induced when FL-Y cells were replaced by NIH3T3 cells that were converted to a IL-34 producer by transduction with the IL-34 gene (Fig. 8C). Thus, it is suggested that in concert with IL-34, an additional molecule that is present on FL-Y cells but not on NIH3T3 cells is involved in FDMC generation.

Figure 8. In addition to IL-34, a contact-dependent signal delivered by FL-Y cells is required for FDMC generation.

(A) IL-34 alone was not sufficient for FDMC induction. TBA-SCs were cultured with FL-Y cells, rIL-34 (10 ng/ml), and/or rCSF-1 (10 ng/ml) for 9 days as described in Fig. 1. Where indicated, the CM of FL-Y cells was added at 20% (vol/vol). (B) Requirement of direct contact between FL-Y cells with the precursor cells for FDMC generation. In the transwell culture, 5 × 103 FL-Y cells were added to the lower chamber, and TBA-SCs (2×105 cells) were added to the upper chamber with a 0.45-μm pore-size membrane. Where indicated, an agonistic anti-LTβR mAb or a control antibody (each at 2.5 μg/ml) was added to the lower chamber to activate FL-Y cells. In a positive control experiment, FL-Y cells were cocultured with the precursor cells. (C) Failure of IL-34-expressing NIH3T3 cells to induce FDMCs. NIH3T3 cells were stably transduced with the empty vector (Mock) or the mouse IL-34 expression vector (IL-34). For induction of FDMCs, TBA-SCs were cultured with FL-Y or the engineered NIH3T3 cells. In all experiments, FDMC induction was assessed on Day 9 of the culture, as described in Fig. 1. Error bars indicate the mean ± sem from triplicate cultures.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that a mouse FDC line, FL-Y, induced development of a new class of CD11b+ monocytic cells named FDMCs from the Lin−c-kit+ precursor cells that were present in mouse spleen. The unique features of FDMCs are as follows. First, FDMC generation was specifically dependent on IL-34 produced by FL-Y cells and the receptor, CSF-1R, expressed on their precursor cells. Second, our surface marker analyses and gene-expression profiling revealed that FDMCs belong to a monocyte/macrophage Lin but are distinct from classical DCs. Although FDMCs (CD11b+CD11c−F4/80+Gr-1−) appeared to be phenotypically close to Ly6CloGr-1− circulating monocytes, these two cell types are distinct, in that the former was CX3CR1−CCR2+, whereas the latter exhibited an opposite phenotype (CX3CR1+CCR2−) [25, 30].

Several types of CD11b+ myeloid cells that share some phenotypes with FDMCs have been described in a variety of experimental systems in vitro and in vivo [16, 17, 25]. For instance, it has been shown that CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells increased in tumor-bearing mice and had suppressive effects on the activation of tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [37, 38]. These cells have been designated as myeloid-derived suppressor cells [25]. Another unique myeloid cell population, designated as regulatory DCs, has also been reported. Splenic stromal cells have been shown to promote differentiation of mature DCs into CD11b+CD11c+I-A+ regulatory DCs that were inactive as APCs but had suppressive effects on antigen-induced proliferation of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells [39, 40]. Similarly, CD11b+ Grl+ CD11c− myeloid cells have been found to expand in mice during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [41], Toxoplasma gondii infection [42], and polymicrobial sepsis [43]. These cells also showed negative regulatory effects on T cell activation. It has been shown that the majority of these regulatory myeloid cells produced NO [37, 39, 41, 42] and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 as immunosuppressive factors [39, 40, 43]. However, our data show that FDMCs were negative for Gr-1 and produced neither NO nor IL-10 (Supplemental Table 1 and our unpublished data). These characteristics suggest that FDMCs are distinct from these previously reported myeloid cell populations.

The strong, enhancing effects of FDMCs on B cell proliferation described here are novel, as B cell-stimulating activity like this has not been generally observed in CD11b+ monocytic cells with one exception. Data show that injection of alum into mice led to an increase of a CD11b+Gr-1+ population in the spleen [44]. These cells have been shown to enhance proliferation of MHC class II-engaged B cells in vitro. IL-4 secreted from the CD11b+Gr-1+ cells has been shown to be critical for stimulating B cell proliferation. However, our data clearly show that FDMCs did not express Gr-1 nor did they produce IL-4 (Supplemental Table 1), indicating that FDMCs are distinct from the alum-induced CD11b+Gr-1+ cells.

FDMCs not only enhanced B cell proliferation but also induced GC B cell-associated markers (GL-7 and Fas) in the cocultured B cells. In GCs, it has been shown that antigen-stimulated B cells differentiate into centroblasts that activate under SHM of Ig genes during rapid cell division [1–3]. The stimuli that are responsible for inducing the rapid proliferation and SHM in centroblasts are uncertain. FDMCs may provide new insight into elucidation of these problems. However, B cell-stimulating factor(s) produced from FDMCs remain to be identified. FDMCs produced no appreciable B cell-stimulating cytokines except IL-6 and IL-15 (Supplemental Table 1). We confirmed that FDMC-induced enhancement of B cell proliferation was not affected by neutralizing antibodies to these cytokines (data not shown). On the other hand, we observed that uPA was expressed at a high level in FDMCs. It has been shown that uPA contributes to skeletal muscle regeneration through enhancing hepatocyte growth factor activity and the proliferation of some types of tumor cells [45, 46]. We confirmed that mouse spleen B cells expressed uPAR, the uPA receptor. Thus, we examined whether uPA from FDMCs was responsible for FDMC-induced enhancement of B cell proliferation using blocking antibodies to uPA or uPAR. Although these antibodies were not inhibitory for the enhancement of B cell proliferation by FDMCs, the viability of B cells was decreased significantly in the presence of these blocking antibodies, thus suggesting that FDMC-derived uPA is potent in sustaining B cell viability under our experimental conditions (our unpublished data). In addition, we found that FDMC-like cells with similar phenotypic markers and immunological functions to those of in vitro-induced FDMCs were present in immunized mice. The B cell-stimulating effects of the FDMC-like cells prepared from immunized mice, however, were usually weak compared with those observed with the in vitro-induced FDMCs. This might be a result of lower purity of the FDMC-like cells or the presence of inhibitory cells in the sorted cell population. Further analyses are currently underway to define FDMC-derived factor(s) involved in the B cell activation and the exact physiological role for FDMCs in vivo.

The most characteristic feature of FDMC development is its specific dependence on IL-34. CSF-1 is broadly expressed in various tissues across vertebrates [20] and has been shown to regulate survival, proliferation, and differentiation of mononuclear phagocytes, including osteoclasts, Langerhans cells, and microglia [14, 16, 17, 19, 30, 35, 47]. CSF-1 transmits its signal through a homodimeric receptor, CSF-1R [14, 15, 20]. It has been shown that CSF-1 or CSF-1R deficiency in mice results in a disorder of osteoclastogenesis, leading to osteopetrosis [13, 16]. Observations that CSF-1R-deficient mice exhibited more severe phenotypes than CSF-1-deficient (Csf1op/op) mice led to the discovery of the second ligand for CSF-1R, IL-34 [13, 14, 23]. Although CSF-1 and IL-34 do not share obvious amino acid sequence homology, each is produced as a dimeric glycoprotein, and both factors have been shown to bind CSF-1R with similar affinities [14].

CSF-1 and IL-34 exhibit comparable activities in supporting the development, proliferation, and survival of macrophages and osteoclastogenesis in vitro, and the genetic disorders in Csf1op/op mice are reduced by IL-34 to the same degree as by the secreted glycoprotein isoform of CSF-1 when either cytokine is transgenically expressed with the same CSF-1-spatiotemporal expression pattern [18]. However, Csf1op/op mice are not compensated completely by IL-34, which they normally express [18, 48], suggesting nonredundant functions of these two cytokines that are determined by their different spatiotemporal expression patterns [18, 48]. Thus, it is important to determine how IL-34 and CSF-1 functionally differ in their regulation of a variety of processes in hematopoiesis, immunity, and the brain.

Recent reports from three groups of investigators clearly indicate that IL-34 and CSF-1 play nonredundant roles [21, 22, 49]. In IL-34-deficient mice, Langerhans cells in the epidermis and microglia cells in some parts of the brain were absent [21, 22]. These are similar phenotypes to those observed in CSF-1R-deficient mice but not Csf1op/op mice [23, 50]. The IL-34-specific dependence of these cells was considered to be a result of the different spatiotemporal expression pattern of IL-34 when compared with that of CSF-1 [21, 22]. In the epidermis, it has been shown that keratinocytes are a major source of IL-34 [21, 22], whereas CSF-1 is poorly expressed in this tissue. In the brain, IL-34 is more strongly expressed in forebrain regions and CSF-1 more strongly in the hindbrain and spinal cord [18, 49]. In the cerebral cortex and elsewhere, these two cytokines are expressed on mature neurons of different types, with the exception of the CA3 region of the hippocampus, where their cellular expression overlaps [21, 22, 49]. Thus, the differential expression pattern between IL-34 and CSF-1 in the epidermis and the brain may help to explain why the development of these two cell types consequently depends on IL-34. However, whether these cell progenitors exclusively respond to IL-34-CSF-1R stimulation has not been examined.

In the present work, we show that FL-Y cells produced CSF-1 and IL-34, but only IL-34 was required for FL-Y-mediated differentiation of c-kit+ precursor cells into FDMCs in a CSF-1R-mediated fashion. Involvement of CSF-1 in this process was ruled out by the following results: (1) NIH3T3 cells that produce CSF-1 but not IL-34 had no ability to induce FDMCs; and (2) the KD of CSF-1 expression in FL-Y cells, in contrast to that of IL-34, had no effects on FDMC generation. IL-34 from FL-Y cells requires CSF-1R on the precursor cells for signaling, as genetic disruption of CSF-1R or its blockade by an anti-CSF-1R mAb resulted in an almost complete loss of FDMC generation. Although it has been shown that CSF-1 and IL-34 differentially exert signal activation through CSF-1R in some cell types [51, 52], a CSF-1R-mediated developmental process that is intrinsically specific for IL-34 has not been reported. If the CSF-1R is the sole mediator of the IL-34 response on these cells, their lack of response to CSF-1 may reflect cell type-specific post-translational modifications of the extracellular domain of the CSF-1R or involvement of third-party molecules that differentially interferes with CSF-1 signaling via the receptor without affecting IL-34 signaling. However, it is also possible that the CSF-1R is not the sole mediator and that the differential effect of IL-34 over CSF-1 is a result of a requirement for IL-34 to signal through the CSF-1R and a second IL-34R. The existence of such a novel IL-34R has been implicated in the brain from the observations that IL-34 stimulates the neuronal differentiation of purified neural progenitor cells more strongly than CSF-1 and that IL-34 expression is elevated in adult mice when CSF-1R expression is markedly reduced [49].

Another important observation is that CSF-1R stimulation with IL-34 alone was not sufficient for FDMC generation. Our transwell experiments showed that direct contact between FL-Y cells with the precursor cells was necessary for FDMC induction. On the other hand, IL-34-expressing NIH3T3 cells were not capable of inducing FDMCs. Thus, it is suggested that an unidentified molecule expressed on FL-Y cells but not NIH3T3 cells may be involved in the contact-dependent transmission of an additional signal that is required for determining the IL-34 specificity of the FDMC generation. We found that this additional signal could be delivered by PFA-fixed FL-Y cells, as well as live FL-Y cells (our unpublished results). Although further studies are necessary to elucidate the molecular basis for the IL-34 specificity of CSF-1R expressed on FDMC progenitor cells, our results provide new insights into our understanding of the complexity of IL-34 and CSF-1 signaling.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports of Japan (21360405 and 24560961 to H.O. and 23790537 to M.M.). N.A.M. was supported by project (BB/F019726/1; JPA-1797) and Institute Strategic Programme grant (BB/J0004332/1) funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. E.R.S. was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grant CA32551.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

The following article is added as a reference, which was published after submission of our manuscript. Nandi, S., Cioce, M., Yeung Y. G., Nieves, E., Tesfa, L., Lin, H., Hsu, A. W., Halenbeck, R., Cheng, H. Y., Gokhan, S., Mehler, M. F., Stanley, E. R. (2013) Receptor-type protein-tyrosine phosphatase ζ is a functional receptor for interleukin-34. J. Biol, Chem. 288, 21972–21986.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 3

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

- BM

- bone marrow

- BMDC

- bone marrow-derived DC

- CD30L

- CD30 ligand

- CM

- conditioned medium

- FDC

- follicular DC

- FDMC

- follicular DC-induced monocytic cell

- GC

- germinal center

- GEO

- Gene Expression Omnibus

- KD

- knockdown

- KLH

- keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- Lin

- lineage

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- RBC

- red blood cell

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- Scr

- scrambled sequence

- SHM

- somatic hypermutation

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- TBA-SC

- T cell-, B cell-, and adherent cell-depleted spleen cell

- uPA

- urokinase-type plasminogen activator

AUTHORSHIP

F.Y. performed experiments, confirming the IL-34 dependence and CSF-1 independence of FDMC induction. Y.N. discovered the induction of FDMCs by FL-Y cells. K.M. analyzed IL-34 and CSF-1R dependence of FDMC induction and IL-34 expression in FL-Y cells. M.A., H.S., Y.F., H.T., and N.K. investigated culture conditions for FDMC induction and analyzed phenotypic markers. E.I. and K.W. investigated B cell-stimulating activity of FDMCs. N.A.M. analyzed the gene-expression profile of FDMC and participated in writing the manuscript. E.R.S. generated CSF-1R-deficient mice and participated in writing the manuscript. M.M. and H.O. designed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vinuesa C. G., Sanz I., Cook M. C. (2009) Dysregulation of germinal centres in autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 845–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rajewsky K. (1996) Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature 381, 751–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu M., Schatz D. G. (2009) Balancing AID and DNA repair during somatic hypermutation. Trends Immunol. 30, 173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allen C. D., Cyster J. G. (2008) Follicular dendritic cell networks of primary follicles and germinal centers: phenotype and function. Semin. Immunol. 20, 14–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kosco-Vilbois M. H. (2003) Are follicular dendritic cells really good for nothing? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 764–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klein U., Dalla-Favera R. (2008) Germinal centres: role in B-cell physiology and malignancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 22–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park C. S., Choi Y. S. (2005) How do follicular dendritic cells interact intimately with B cells in the germinal centre? Immunology 114, 2–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nishikawa Y., Hikida M., Magari M., Kanayama N., Mori M., Kitamura H., Kurosaki T., Ohmori H. (2006) Establishment of lymphotoxin β receptor signaling-dependent cell lines with follicular dendritic cell phenotypes from mouse lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 177, 5204–5214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mabbott N. A., Kenneth Baillie J., Kobayashi A., Donaldson D. S., Ohmori H., Yoon S. O., Freedman A. S., Freeman T. C., Summers K. M. (2011) Expression of mesenchyme-specific gene signatures by follicular dendritic cells: insights from the meta-analysis of microarray data from multiple mouse cell populations. Immunology 133, 482–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mackay F., Browning J. L. (1998) Turning off follicular dendritic cells. Nature 395, 26–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Endres R., Alimzhanov M. B., Plitz T., Futterer A., Kosco-Vilbois M. H., Nedospasov S. A., Rajewsky K., Pfeffer K. (1999) Mature follicular dendritic cell networks depend on expression of lymphotoxin β receptor by radioresistant stromal cells and of lymphotoxin β and tumor necrosis factor by B cells. J. Exp. Med. 189, 159–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magari M., Nishikawa Y., Fujii Y., Nishio Y., Watanabe K., Fujiwara M., Kanayama N., Ohmori H. (2011) IL-21-dependent B cell death driven by prostaglandin E2, a product secreted from follicular dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 187, 4210–4218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dai X. M., Ryan G. R., Hapel A. J., Dominguez M. G., Russell R. G., Kapp S., Sylvestre V., Stanley E. R. (2002) Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood 99, 111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin H., Lee E., Hestir K., Leo C., Huang M., Bosch E., Halenbeck R., Wu G., Zhou A., Behrens D., Hollenbaugh D., Linnemann T., Qin M., Wong J., Chu K., Doberstein S. K., Williams L. T. (2008) Discovery of a cytokine and its receptor by functional screening of the extracellular proteome. Science 320, 807–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garceau V., Smith J., Paton I. R., Davey M., Fares M. A., Sester D. P., Burt D. W., Hume D. A. (2010) Pivotal Advance: Avian colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1), interleukin-34 (IL-34), and CSF-1 receptor genes and gene products. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87, 753–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamilton J. A., Achuthan A. (2013) Colony stimulating factors and myeloid cell biology in health and disease. Trends Immunol. 34, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hume D. A. (2008) Macrophages as APC and the dendritic cell myth. J. Immunol. 181, 5829–5835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wei S., Nandi S., Chitu V., Yeung Y. G., Yu W., Huang M., Williams L. T., Lin H., Stanley E. R. (2010) Functional overlap but differential expression of CSF-1 and IL-34 in their CSF-1 receptor-mediated regulation of myeloid cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zelante T., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. (2012) The yin-yang nature of CSF1R-binding cytokines. Nat. Immunol. 13, 717–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Droin N., Solary E. (2010) Editorial: CSF1R, CSF-1, and IL-34, a “menage a trois” conserved across vertebrates. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87, 745–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Y., Szretter K. J., Vermi W., Gilfillan S., Rossini C., Cella M., Barrow A. D., Diamond M. S., Colonna M. (2012) IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nat. Immunol. 13, 753–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greter M., Lelios I., Pelczar P., Hoeffel G., Price J., Leboeuf M., Kundig T. M., Frei K., Ginhoux F., Merad M., Becher B. (2012) Stroma-derived interleukin-34 controls the development and maintenance of Langerhans cells and the maintenance of microglia. Immunity 37, 1050–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ginhoux F., Tacke F., Angeli V., Bogunovic M., Loubeau M., Dai X. M., Stanley E. R., Randolph G. J., Merad M. (2006) Langerhans cells arise from monocytes in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 7, 265–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Witmer-Pack M. D., Hughes D. A., Schuler G., Lawson L., McWilliam A., Inaba K., Steinman R. M., Gordon S. (1993) Identification of macrophages and dendritic cells in the osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse. J. Cell Sci. 104, 1021–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gabrilovich D. I., Nagaraj S. (2009) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freeman T. C., Goldovsky L., Brosch M., van Dongen S., Maziere P., Grocock R. J., Freilich S., Thornton J., Enright A. J. (2007) Construction, visualisation, and clustering of transcription networks from microarray expression data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, 2032–2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mabbott N. A., Kenneth Baillie J., Hume D. A., Freeman T. C. (2010) Meta-analysis of lineage-specific gene expression signatures in mouse leukocyte populations. Immunobiology 215, 724–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hume D. A., Summers K. M., Raza S., Baillie J. K., Freeman T. C. (2010) Functional clustering and lineage markers: insights into cellular differentiation and gene function from large-scale microarray studies of purified primary cell populations. Genomics 95, 328–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Labeur M. S., Roters B., Pers B., Mehling A., Luger T. A., Schwarz T., Grabbe S. (1999) Generation of tumor immunity by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells correlates with dendritic cell maturation stage. J. Immunol. 162, 168–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Geissmann F., Manz M. G., Jung S., Sieweke M. H., Merad M., Ley K. (2010) Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science 327, 656–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Geissmann F., Jung S., Littman D. R. (2003) Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 19, 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bronte V., Apolloni E., Cabrelle A., Ronca R., Serafini P., Zamboni P., Restifo N. P., Zanovello P. (2000) Identification of a CD11b(+)/Gr-1(+)/CD31(+) myeloid progenitor capable of activating or suppressing CD8(+) T cells. Blood 96, 3838–3846 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hume D. A., Mabbott N., Raza S., Freeman T. C. (2013) Can DCs be distinguished from macrophages by molecular signatures? Nat. Immunol. 14, 187–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nandi S., Akhter M. P., Seifert M. F., Dai X. M., Stanley E. R. (2006) Developmental and functional significance of the CSF-1 proteoglycan chondroitin sulfate chain. Blood 107, 786–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pixley F. J., Stanley E. R. (2004) CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 628–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stein J., Borzillo G. V., Rettenmier C. W. (1990) Direct stimulation of cells expressing receptors for macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) by a plasma membrane-bound precursor of human CSF-1. Blood 76, 1308–1314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Youn J. I., Nagaraj S., Collazo M., Gabrilovich D. I. (2008) Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Immunol. 181, 5791–5802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Watanabe S., Deguchi K., Zheng R., Tamai H., Wang L. X., Cohen P. A., Shu S. (2008) Tumor-induced CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells suppress T cell sensitization in tumor-draining lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 181, 3291–3300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang M., Tang H., Guo Z., An H., Zhu X., Song W., Guo J., Huang X., Chen T., Wang J., Cao X. (2004) Splenic stroma drives mature dendritic cells to differentiate into regulatory dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 5, 1124–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Svensson M., Maroof A., Ato M., Kaye P. M. (2004) Stromal cells direct local differentiation of regulatory dendritic cells. Immunity 21, 805–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhu B., Bando Y., Xiao S., Yang K., Anderson A. C., Kuchroo V. K., Khoury S. J. (2007) CD11b+Ly-6C(hi) suppressive monocytes in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 179, 5228–5237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dunay I. R., Damatta R. A., Fux B., Presti R., Greco S., Colonna M., Sibley L. D. (2008) Gr1(+) inflammatory monocytes are required for mucosal resistance to the pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity 29, 306–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Delano M. J., Scumpia P. O., Weinstein J. S., Coco D., Nagaraj S., Kelly-Scumpia K. M., O'Malley K. A., Wynn J. L., Antonenko S., Al-Quran S. Z., Swan R., Chung C. S., Atkinson M. A., Ramphal R., Gabrilovich D. I., Reeves W. H., Ayala A., Phillips J., Laface D., Heyworth P. G., Clare-Salzler M., Moldawer L. L. (2007) MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1(+)CD11b(+) population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1463–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jordan M. B., Mills D. M., Kappler J., Marrack P., Cambier J. C. (2004) Promotion of B cell immune responses via an alum-induced myeloid cell population. Science 304, 1808–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sisson T. H., Nguyen M. H., Yu B., Novak M. L., Simon R. H., Koh T. J. (2009) Urokinase-type plasminogen activator increases hepatocyte growth factor activity required for skeletal muscle regeneration. Blood 114, 5052–5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith H. W., Marshall C. J. (2010) Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chitu V., Stanley E. R. (2006) Colony-stimulating factor-1 in immunity and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18, 39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nakamichi Y., Mizoguchi T., Arai A., Kobayashi Y., Sato M., Penninger J. M., Yasuda H., Kato S., DeLuca H. F., Suda T., Udagawa N., Takahashi N. (2012) Spleen serves as a reservoir of osteoclast precursors through vitamin D-induced IL-34 expression in osteopetrotic op/op mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10006–10011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nandi S., Gokhan S., Dai X. M., Wei S., Enikolopov G., Lin H., Mehler M. F., Stanley E. R. (2012) The CSF-1 receptor ligands IL-34 and CSF-1 exhibit distinct developmental brain expression patterns and regulate neural progenitor cell maintenance and maturation. Dev. Biol. 367, 100–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ginhoux F., Greter M., Leboeuf M., Nandi S., See P., Gokhan S., Mehler M. F., Conway S. J., Ng L. G., Stanley E. R., Samokhvalov I. M., Merad M. (2010) Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 330, 841–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chihara T., Suzu S., Hassan R., Chutiwitoonchai N., Hiyoshi M., Motoyoshi K., Kimura F., Okada S. (2010) IL-34 and M-CSF share the receptor Fms but are not identical in biological activity and signal activation. Cell Death Differ. 17, 1917–1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu H., Leo C., Chen X., Wong B. R., Williams L. T., Lin H., He X. (2012) The mechanism of shared but distinct CSF-1R signaling by the non-homologous cytokines IL-34 and CSF-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1824, 938–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.