Abstract

Cell fate decisions depend on the interplay between chromatin regulators and transcription factors. Here we show that activity of the Mi-2β nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex was controlled by the Ikaros family of lymphoid-lineage determining proteins. Ikaros, an integral component of the NuRD complex in lymphocytes, tethered this complex to active lymphoid differentiation genes. Loss in Ikaros DNA binding activity caused a local increase in Mi-2β chromatin remodeling and histone deacetylation and suppression of lymphoid gene expression. The NuRD complex also redistributed to transcriptionally poised non-Ikaros gene targets, involved in proliferation and metabolism, inducing their reactivation. Thus, release of NuRD from Ikaros regulation blocks lymphocyte maturation and mediates progression to a leukemic state by engaging functionally opposing epigenetic and genetic networks.

Introduction

The fate of a cell is determined by the way that its genetic material and its protein scaffold, collectively referred to as chromatin, are modified. Chromatin influences the outcome of DNA-based processes such as transcription, replication, recombination and repair. The structure of chromatin is in part modulated by functionally diverse enzymes, which modify histones in the basic chromatin unit, the nucleosome, thereby providing direct or indirect modes of regulation of DNA accessibility. Histone acetylation can directly influence nucleosome configuration and is supportive of transcription initiation and elongation1,2. Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and deacetylases (HDACs) were recently shown to be concomitantly loaded on active genes possibly in anticipation of transcriptional changes3. The Mi-2β nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylase complex (NuRD) is one of several histone deacetylase complexes present in mammalian cells but is unique in that it contains both chromatin opening and closing enzymatic activities4,5. It has been hypothesized that the ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling activity of Mi-2β enables activity of the associated HDACs in the NuRD complex4. Chromatin modifying and remodeling activities are thought to be recruited to specific loci through association with sequence-specific DNA-binding factors, direct binding to pre-existing histone modifications, or other mechanisms6. In cells of the hematopoietic lineage, the NuRD complex stably associates with the Ikaros family of lymphoid lineage-determining DNA binding factors7,8. Thus the association between the NuRD complex and Ikaros proteins provides a unique paradigm by which to delineate how chromatin regulation is harnessed for the benefit of key developmental transitions.

The Ikaros gene family encodes zinc finger DNA binding proteins that serve as key regulators of lymphocyte development, function and homeostasis9. Ikaros primes the lymphoid lineage potential of multipotent progenitors and its loss severs lymphoid lineage specification and commitment10,11. After commitment into the T cell lineage, a higher level of Ikaros activity is required for homeostasis of differentiating precursors. Thymocytes, past the double-negative (DN) stage of differentiation, express high amounts of both the Ikaros and Aiolos family members12, and are exquisitely sensitive to perturbations in Ikaros DNA binding activity. Reduction in Ikaros that is not sufficient to interfere with early lymphoid lineage decisions nevertheless causes aberrant expansion of CD4+CD8+ (DP) TCRint thymocytes, which are reminiscent of cells undergoing TCR-mediated selection13,14. Ikaros-deficient DP TCR+ thymocytes, in response to a series of triggers including activation of Notch signaling, undergo further transition to a leukemic state15,16.

Genetic studies on Ikaros and Mi-2β have independently established their participation within the same molecular processes but have also uncovered an unexpected functional antagonism17,18. In multipotent hematopoietic progenitors, Ikaros promotes lymphoid lineage priming and commitment, whereas Mi-2β inhibits this process11 (T. Y. unpublished data). Loss of Ikaros results in illegitimate Cd4 activation in DN thymocytes, whereas loss of Mi-2β results in illegitimate Cd4 silencing in DP thymocytes18. Similarly, loss of Ikaros causes aberrant T cell activation whereas loss of Mi-2β interferes with T cell activation and proliferation17,19. Ikaros mutant mice develop T cell leukemia whereas Ikaros and Mi-2β doubly deficient mice survive past 6 months and are disease free (unpublished data). In spite of its critical role in lymphocyte development and leukemogenesis, the molecular basis of Ikaros and Mi-2β antagonism remains elusive.

Using this genetic system we show that in DP thymocytes, the NuRD complex contained both Ikaros and Aiolos and was targeted predominantly through common DNA binding motifs to transcriptionally active lymphoid differentiation genes. Loss in Ikaros correlated with a local gain in NuRD function, which was still recruited to these sites through Aiolos. Increased nucleosome remodeling and histone deactylase activity were detected that interfered with RNA polymerase II (RNA polII) recruitment and lymphoid gene expression. In addition, loss of Ikaros from the NuRD complex resulted in NuRD redistribution to permissive chromatin of transcriptionally poised, non-Ikaros gene targets, involved in cell growth and metabolism, causing their reactivation. We thus propose that balanced targeting of the NuRD complex through lineage-specific DNA binding factors and chromatin code is key to the timely induction of differentiation versus growth and proliferation genetic programs during development. Deregulation of this process causes differentiation arrest and leukemic transformation.

RESULTS

NuRD complex composition in primary DP thymocytes

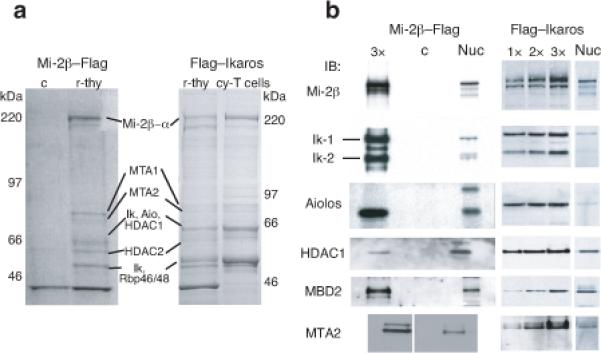

Association between the NuRD complex and Ikaros proteins was previously reported in cycling T cells and erythroleukemia cells7,8. We investigated whether this interaction also occurs in DP thymocytes which comprise 85% of the primary thymocyte population. DP thymocytes are quiescent cells that express abundant Ikaros family proteins and which need to undergo T cell receptor (TCR) recombination and selection prior to differentiating into immunocompetent T cells20.

Two protein complexes were purified from primary thymocytes using either an epitope-tagged Mi-2β or Ikaros protein, expressed in transgenic mice (Fig. 1a). Mi-2β is an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeler and an essential and non-redundant component of the NuRD complex that binds directly, and with high affinity, to Ikaros proteins21. Ikaros, its family member Aiolos, and NuRD complex components such as MTA1, 2, HDAC1, 2, and Rbp46, 48 were identified by protein microsequencing (Fig. 1). Immunoblot analysis verified strong enrichment of NuRD components in both complexes, relative to unfractionated nuclear extract (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). This result is consistent with previous Ikaros-based complex purifications from actively cycling T cells (Fig. 1a, cy-T cells)7. Thus, Ikaros DNA binding proteins are stable components of the NuRD complex in quiescent DP thymocytes as in cycling T cells.

Figure 1. NuRD complex composition in primary DP thymocytes.

(a) NuRD complex components were isolated from primary resting thymocytes (r-thy) or cycling T cells (cy-T cells) from mice transgenic for either Mi-2β-flag or flag-Ikaros using heparin sepharose and anti-Flag immunoaffinity columns as previously described7. The composition of Mi-2β-Flag and Flag-Ikaros purified complexes was visualized by colloidal blue staining of gradient acrylamide gels. A mock purification of non-transgenic thymocytes is provided as specificity control (c). Data shown is representative of more than two independent complex purifications performed from Mi-2β-flag or flag-Ikaros expressing cells. (b) Immunoblot analysis of Mi–2β-flag and flag-Ikaros based complexes shows strong enrichment for NuRD complex components (Mi-2β, α, MTA1, 2, HDAC1, 2, Rbp46, 48)5 and Ikaros family members (i.e. Ikaros isoforms Ik-1 and Ik-2 and Aiolos) relative to unfractionated nuclear extract (nuc). 1x-indicates loading of ~10ng of purified complex compared to 1.5-2 micrograms of nuclear extract. Analysis of a mock purification (c) from non-transgenic thymocytes was performed in parallel to the Mi–2β-flag purification. Full protein characterization is described in Supplementary Table 1.

Genome-wide targeting of the Ikaros-NuRD complex

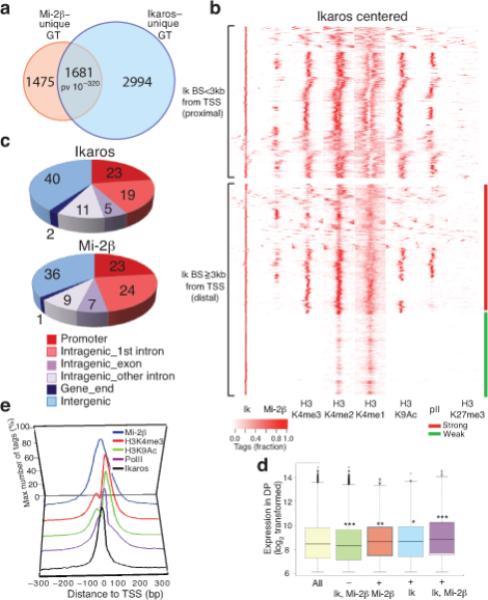

Ikaros’ DNA binding activity is required for lymphocyte development and homeostasis and its ability to target chromatin remodeling in a sequence-specific manner has been proposed as its modus operandi in the NuRD complex9. To test this hypothesis, the genome-wide distribution of Ikaros and Mi-2β was established in DP thymocytes by chromatin immunoprecipitations and DNA sequencing (ChIP-Seq). Ikaros bound to 7120 sites whereas Mi-2β bound to 4158 sites (P-value <10−5), which associated respectively with 4675 and 3156 gene targets (Fig. 2a and Table 1). Approximately 53% of Mi-2β binding sites and ~36% of Ikaros binding sites were associated with each other at the gene level, as identified by the closest transcription start site (Fig. 2a, P-value < 10−320). Ward hierarchical clustering centered on either Ikaros or Mi-2β enrichment peaks verified this proximity (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Ikaros and Mi-2β were similarly distributed at six different genomic locations with intergenic (40% vs. 36%) and promoter-proximal (42% vs. 47%) being the most prevalent (Fig. 2c). Taken together, protein complex purification and mapping studies confirm that Ikaros works through the NuRD complex at distinct regulatory regions of the DP genome.

Figure 2. Genome-wide mapping of the Ikaros-NuRD complex in permissive chromatin and transcriptionally active genes.

Genome-wide analyses of Ikaros and Mi-2β enrichment peaks obtained from ChIP-Seq replicates on the two factors identifying unique gene targets. (a) Highly significant overlap between Ikaros and Mi-2β gene targets (GT) (P-value = 10−320). (b) Ward's hierarchical clustering centered on Ikaros (Ik) binding sites and further analyzed within +/− 3 kb window for occupancy by Mi-2β, H3K4me3 (K4me3), H3K4me2 (K4me2), H3K4me1 (K4me1), H3K9Ac (K9Ac), RNA polII (polII) and H3K27me3 (K27me3). All Ikaros peaks were included in the analysis. Ikaros binding sites are grouped by promoter-proximal (<3 kb from the transcription start site, TSS, top) or promoter-distal (>=3 kb, bottom) locations. (c) Pie-chart distribution of Ikaros and Mi-2β sites at various genomic locations. (d) Expression analysis of gene subsets with and without Ikaros and or Mi-2β enrichment peaks in WT DP thymocytes. The bottom and top of each Whisker box plot represent the 25th and 75th percentile and the internal band the 50th percentile (median) in the group. P-values for the difference in expression between subsets and the all-gene group are shown. (e) Ikaros, Mi-2β, H3K4me3, H3K9Ac and RNA polII distribution relative to TSS. Biological replicates for Ikaros and Mi-2β ChIP-Seq experiments with good overlap (>50%) were pooled and used for peak analysis and data presentation. Enrichment peaks for H3 modifications in WT chromatin (i.e. H3K4m3, me2, me1, H3K9Ac, RNA polII or H3K27me3) were deduced from one ChIP-Seq experiment as they displayed expected correlation with each other and with regulatory domain distribution.

Table 1.

Chromatin status of Ikaros, Aiolos or Mi–2β gene targets

| H3K4me3 | H3K9Ac | H3K27me3 | H3K36me3 | RNApIIS5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ikaros WT | 87% | 83% | 39% | 70% | 61% |

| Mi−2β WT | 87% | 84% | 40% | 73% | 66% |

| Aiolos IkΔ | 88% | 83% | 43% | 68% | 56% |

| Mi−2b IkΔ | 84% | 80% | 43% | 67% | 55% |

Ikaros-NURD complex targets permissive chromatin

We next examined the chromatin environment surrounding Ikaros and Mi-2β sites and the transcriptional state of their gene targets. Ward hierarchical clustering22 centered on Ikaros sites at promoter proximal locations (3 kb upstream or downstream of TSS) revealed extensive association with permissive histone H3 modifications (methylation of lysine 4 (H3K4me3, 2, 1) or acetylation of lysine 9, H3K9Ac) as well as with RNA polII (Fig. 2b and Table 1). A similar association was observed at promoter-distal (greater than 3 kb of TSS) Ikaros sites, which depending on H3K4me1, me2 and me3 distributions could be further classified into strong or weak and or poised enhancers (Fig. 2b)23. In contrast, there was little direct overlap between Ikaros or Mi-2β sites and H3 trimethylated lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a mark of PRC2 polycomb complex activity and silent or bivalent chromatin24,25. Nonetheless, Ikaros or Mi-2β sites and H3K27me3 sites although non-overlapping were frequently (40%) associated at the gene level (Table 1).

RNA expression analysis in DP thymocytes indicated that Ikaros and Mi-2β gene targets were transcriptionally more active compared to genes not bound by these factors (Fig. 2d). Approximately 70% of Ikaros and Mi-2β gene targets were enriched for the H3K36me3 transcription elongation mark (Table 1). Since ~25% of Ikaros and Mi-2β sites were in close proximity to promoters we examined their distribution relative to the transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 2e). Ikaros distribution was centered on the TSS, fitting within the groove generated by the H3K4me3 and H3K9Ac-K14Ac marked nucleosomes that flank a transcriptionally active TSS. RNA polII distribution overlapped that of Ikaros. Interestingly, Mi-2β exhibited a broader distribution over the TSS, covering Ikaros, the two TSS-flanking nucleosomes and RNA polII. Thus in DP thymocytes, Ikaros and Mi-2β predominantly associate with transcriptionally active genes, frequently in the immediate vicinity of the RNA polII complex, implicating a direct role in the transcription cycle.

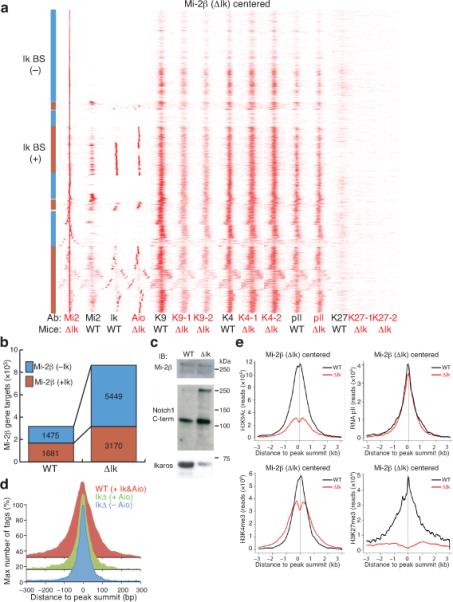

Ikaros loss and gain in NuRD chromatin enrichment

The role of Ikaros in targeting the NuRD complex was evaluated by comparing Mi-2β distribution in wild-type and Ikaros null pre-leukemic thymocytes obtained from 3-5 week old mice. As in wild-type cells, a large proportion of Ikaros null thymocytes were found at the DP stage and had not activated Notch signaling, which is a late event in leukemic progression16,18. An unexpected enrichment in Mi-2β binding was observed in Ikaros null chromatin (Fig. 3a,b). This result was not due to higher Mi-2β mRNA or protein abundance (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 2). It was also not due to a global effect on chromatin accessibility, as binding of RNA polII and other factors in the vicinity of Mi-2β sites was not increased (Fig. 3a, e), suggesting a specific effect on Mi-2β chromatin access. Different methods of analysis with comparable normalized reads from Mi-2β ChIP-Seq in wild-type and Ikaros null thymocytes consistently showed increased Mi-2β enrichment (Supplementary Fig. 1c and Fig. 3a). A <2 fold increase in Mi-2β binding was seen at sites normally bound by Ikaros in wild-type (Fig. 3a,b), the majority of which were also occupied by Aiolos, the second-most prevalent Ikaros family member and NuRD complex component in thymocytes (Fig. 3a and Fig. 1). However, a greater (>3.5 fold) increase was detected at non-Ikaros sites and gene targets (Fig. 3a, b).

Figure 3. Loss of Ikaros causes a profound gain in Mi-2β chromatin enrichment, remodeling and histone deacetylation.

(a) Ward's hierarchical clustering of Mi-2β-centered binding sites analyzed as in Fig. 2 for Ikaros, Aiolos, RNA polII, and H3 modifications in WT and Ikaros null (ΔIk) chromatin. All Mi-2β enrichment peaks obtained in Ikaros null chromatin were used in this analysis. (b) Increase in Mi-2β in ΔIk chromatin at non-Ikaros and Ikaros gene targets. (c) Immunoblot analysis of Mi-2β protein in WT and ΔIk total thymocyte extracts. Expression of Notch1 and Ikaros proteins are shown as controls. (d) Progressive narrowing of the Mi-2β distribution pattern over its enrichment peak in WT and ΔIk chromatin correlates with loss of co-occupancy by Ikaros or Aiolos. (e) Cumulative analysis of H3 modifications and RNA polII changes relative to the center of Mi-2β peaks in WT (black) and ΔIk (red) chromatin. Biological replicates for transcription factors were performed as described in Figure 2. Two biological replicates of Ikaros null pre-leukemic samples (−1, −2) were used for ChIP-Seq experiments and enrichment peak analysis for H3K9Ac, H3K4me3 and H3K27me3.

The vast majority of de novo and pre-existing Mi-2β sites detected in Ikaros null chromatin were in permissive chromatin, marked by H3K4me3, H3K9Ac and RNA polII, with a small subset again associated with H3K27me3 (Fig. 3a and Table 1). Notably, the broad binding pattern of Mi-2β observed in wild-type cells became progressively narrower in Ikaros null chromatin (Fig. 3a,d) in a manner that inversely correlated with the presence of Ikaros-type proteins in this complex. Thus although an increased number of chromatin sites are occupied by Mi-2β in the absence of Ikaros-family proteins the binding pattern is more focused. Overall the data suggest a gain in NuRD complex chromatin accessibility upon loss of Ikaros.

NuRD complex activity is negatively regulated by Ikaros

We further evaluated the histone modification status in proximity to Mi-2β sites in Ikaros null compared to wild-type chromatin. Ward hierarchical clustering of Mi-2β sites in Ikaros null chromatin revealed an extensive decrease in histone acetylation in its immediate vicinity detected with independent chromatin samples prepared from Ikaros null pre-leukemic DP thymocytes (Fig. 3a). Cumulative distribution analysis centered on Mi-2β sites confirmed the profound decrease in H3K9Ac-K14Ac frequency. In fact, the majority of genome-wide loss in H3K9Ac-K14Ac marks (67%) in Ikaros null chromatin was directly associated with Mi-2β occupancy (Supplementary Table 2). This analysis also revealed increased nucleosome remodeling in the vicinity of Mi-2β sites in the null compared to wild-type chromatin (Fig. 3e, K4me3 and K9Ac). Interestingly, an ablation of H3K27me3 was also detected at the subset of Mi-2β sites marked by this modification in wild-type chromatin (Fig. 3a,e, K27me3), implicating a potential antagonism between Mi-2β–NuRD and the PRC2 complex. In sharp contrast to the profound H3K9Ac decrease, the overall changes in H3K4me3 and RNA polII were relatively small (Fig. 3a,e). Nonetheless, the majority of the RNA polII changes were associated with increased Mi-2β occupancy (Supplementary Table 2).

The effect of Ikaros DNA binding on the nucleosome remodeling activity of Mi-2β was further investigated in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 3). Mononucleosomes and 5S nucleosomal arrays were generated with DNA templates containing rotational phasing sequences and Ikaros consensus sites. As a negative control, DNA template with non-binding Ikaros site mutations was used for mononucleosome assembly. The Ikaros-Mi-2β complex bound with specificity to both naked DNA and mononucleosomes harboring Ikaros binding sites but not to DNA or mononucleosomes without Ikaros sites (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). Notably, binding of the Ikaros-NuRD complex to mononucleosomes was stimulated by ATP. Ikaros-specific DNA binding was validated by incubation with an Ikaros antibody that decreased the mobility of the Ikaros-DNA binding complex (Supplementary Fig. 3a, labeled αIk). DNA templates with and without Ikaros sites formed positioned mononucleosomes as evidenced by the 10-bp repeat generated by the limited DNAse I cleavage at DNA sites facing away from the histone octamer (Supplementary Fig. 3c). At high concentrations of the Ikaros complex, an ATP-dependent disruption of the DNAse I cleavage pattern was evidenced by characteristic enhancements and protections on both templates, referred to as mononucleosome remodeling. However, at lower Ikaros complex concentration remodeling occurred preferentially on nucleosomes without Ikaros sites. Similarly, competition with oligonucleotides containing Ikaros binding sites provided more Ikaros complex remodeling and restriction enzyme accessibility in 5S nucleosomal arrays (Supplementary Fig. 3d). No such effect was observed with the hSWI-SNF nucleosome remodeling complex purified from HeLa cells that does not contain Ikaros.

Taken together both in vivo and in vitro studies provide strong evidence that Ikaros DNA binding plays an inhibitory role on Mi-2β chromatin accessibility and nucleosome remodeling. Sequence-specific binding of the Ikaros-NuRD complex on nucleosomes likely restricts access of Mi-2β to its nucleosomal substrate either through hindrance or by interference with the activity of the remodeler. Inhibition of Ikaros sequence-specific DNA binding stimulates Mi-2β nucleosome remodeling, which facilitates histone access and deacetylation. Increases in nucleosome remodeling may also influence access or activity of other chromatin modifiers such as the PRC2 complex, when recruited in proximity to the NuRD complex.

Sequence specific targeting of the Ikaros-NURD complex

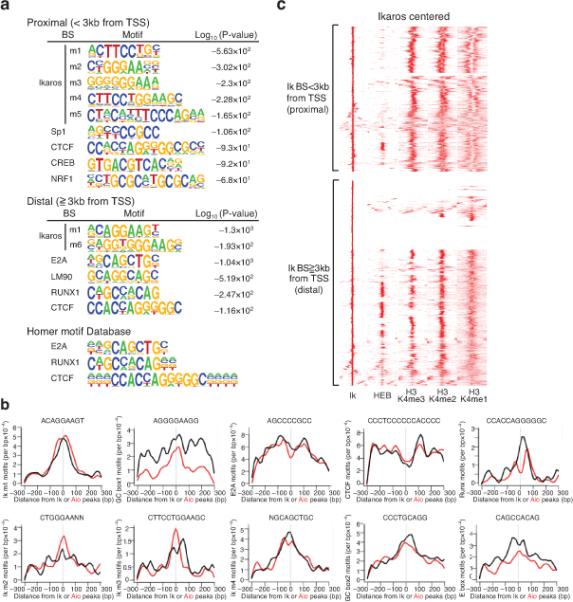

The DNA sequence specificity in the vicinity of Ikaros and Mi-2β binding sites was investigated. Homer de novo motif analysis was performed first in the vicinity of Ikaros sites at promoter-proximal and promoter-distal locations established in wild-type chromatin. The majority of these sites were still occupied by Aiolos and Mi-2β in Ikaros null chromatin (Fig. 3a).

Ikaros DNA binding motifs (Ik m1-m5) previously established in vitro26,27 were highly enriched in the vicinity of Ikaros peaks in wild-type chromatin and of Aiolos peaks in Ikaros null chromatin (Fig. 4a,b), indicating that both proteins target the NuRD complex to chromatin with similar sequence specificity. The most prevalent Ikaros motif (Ik m1, 5’-ACAGGAAGT-3’) detected at both promoter proximal and distal locations is a variant of an Ets1 motif present in lymphoid-specific regulatory elements28. Some Ikaros motifs (for example, Ik m4) at promoters displayed similarity to STAT binding sites, suggesting interplay between Ikaros and the JAK-STAT pathway. At promoter-distal Ikaros sites, a highly significant enrichment of E2A-HEB motifs was identified (Fig. 4a,b). Ikaros association with E-box proteins was further investigated by examining the genome-wide distribution of HEB in DP thymocytes. HEB is an E2A family member that heterodimerizes with E2A and mediates common effects on gene expression and TCR selection required for T cell differentiation29-31. A highly significant association between HEB and Ikaros was detected at enhancer locations (Fig. 4c). E2A binding sites were recently shown to associate with Ikaros-like Ets1 (Ik m1) and Runx1 motifs at transcriptional enhancers active in B cell precursors32. A significant association between Ikaros sites and Runx motifs was also observed here at T cell enhancers (Fig. 4a,b). Ikaros also acts through its cognate sites located at promoters and in proximity to basal transcription elements such as GC boxes and binding motifs for CREB and NRF1 (Fig. 4a,b). Motifs for the insulator protein CTCF were also associated with Ikaros at promoter and enhancer locations, albeit at lower frequency (Fig. 4a, b). Together these studies reveal a strong conservation between T and B cell enhancers and a key role for the Ikaros-NuRD complex in regulating gene accessibility and expression, acting in concert with other key lymphoid lineage-specific transcription regulators.

Figure 4. Targeting of the Mi-2β-NuRD complex to a lymphoid-specific gene network.

(a) Identification of Ikaros-related (m1-m5) and non-related motifs in the vicinity of Ikaros sites at promoter-proximal (top) and distal (bottom) locations in WT chromatin and log10 (P-value) for motif occurrence. (b) Context-specific frequencies of factor motifs in the vicinity (+/− 300 bp) of Ikaros (black) and Aiolos (red) enrichment peaks in WT and ΔIk chromatin. The distribution and moving average of motif frequencies within a 15bp window is shown. (c) Ward's hierarchical clustering of Ikaros, HEB and H3K4me3, me2 and me1 modifications at promoter proximal and distal locations as described in Fig. 2. All Ikaros peaks obtained in WT chromatin are included in this analysis.

Mode of NuRD targeting identifies distinct gene networks

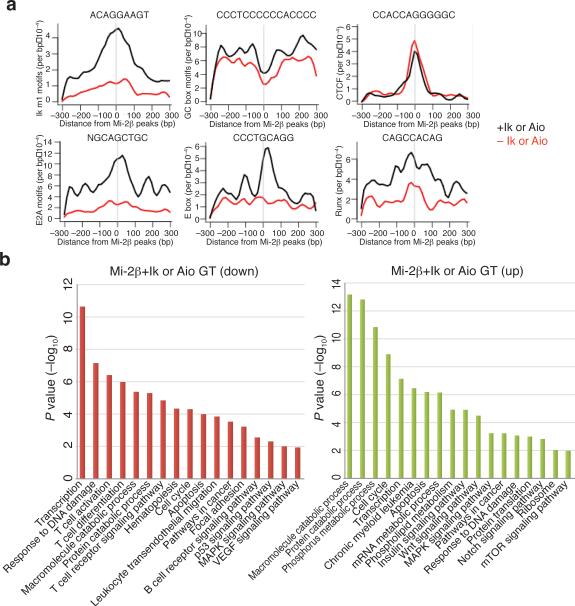

Analysis of Mi-2β enrichment peaks present in the vicinity of Ikaros or Aiolos enrichment peaks were significantly associated with motifs for Ikaros and its lymphoid factor associates indicating direct recruitment through these DNA binding factors (Fig. 5a, Mi-2β+Ik or Aio, Ikm1, E2A, E-box, Runx). In sharp contrast, Mi-2β enrichment peaks that were not in the vicinity of Ikaros or Aiolos enrichment peaks, did not associate at any significant frequency with Ikaros or other lymphoid factor motifs (Fig. 5a, Mi-2β-Ik or Aio, Ikm1, E2A, E-box, Runx). However in both cases, Mi-2β sites were highly enriched for basal transcription elements such as GC boxes at promoters as well as with CTCF motifs at both promoter proximal and distal regions (Fig. 5a, Mi-2β+ or – Ik or Aio, GC, CTCF). Thus in the presence of Ikaros, the NuRD complex is targeted primarily to lymphoid-specific regulatory regions highly enriched for Ikaros, E2A and Runx binding sites, whereas in the absence of Ikaros, targeting occurs either by pre-existing permissive chromatin codes such as H3K4me3 or through components of the basal transcription machinery.

Figure 5. GO pathway analysis of Mi-2β gene targets.

(a) Context-specific frequencies of transcription factor motifs (Ikaros motif 1, E2A, Runx, CTCF, E-box, GC) identified in the vicinity (+/− 300 bp) of Mi-2β peaks that were (black) or not (red) associated with Ikaros or Aiolos peaks in WT and ΔIk chromatin as described in Fig. 4c. (b) Gene ontology of Mi-2β, Ikaros and Aiolos gene targets (+Ik or Aio) or Mi-2β alone (–Ik or Aio) gene targets established in WT and ΔIk chromatin. The significance in pathway enrichment is shown as - log10(P-value).

Pathway analysis of genes targeted by the Ikaros–Mi-2β–NuRD complex or by the Mi-2β–NuRD complex alone has provided insight into the functional consequences of NuRD's differential targeting in wild-type and Ikaros null chromatin. Genes associated with Mi-2β–NuRD de novo sites in Ikaros null chromatin that lack Ikaros DNA binding motifs, exhibited strong and specific enrichment in pathways involved in cell growth such as mRNA, phospholipid metabolism, protein translation as well as insulin, Wnt, Notch and mTOR signaling (Fig. 5b, Mi-2β-Ik or Aio GT and Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, lymphoid-specific genes and pathways involved in T cell activation, differentiation, migration and adhesion, were specifically targeted by the Ikaros–NuRD complex (Fig. 5b, Mi-2β+Ik or Aio GT and Supplementary Fig. 4). Both NuRD complexes associated with transcription, cell cycle, DNA damage, apoptosis and catabolic processes albeit at different frequencies and with different gene targets (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 4). Taken together, these findings indicate that Mi-2β targets two classes of genetic networks that are functionally distinct. One that is normally regulated by Ikaros and supports lymphocyte differentiation, and a second that is guided by permissive chromatin code or basal transcription mechanisms and which supports cell growth and proliferation.

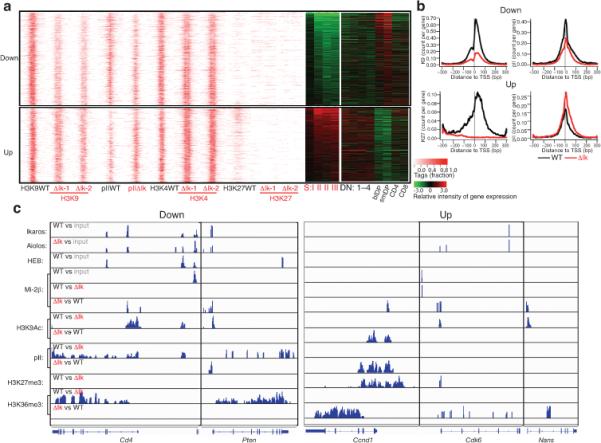

NuRD's opposing effects on differentiation vs. growth

The transcriptional effects of Ikaros-loss and Mi-2β–NuRD gain-of-function were evaluated in DP thymocytes. Changes in the transcriptional elongation marker H3K36me3 in pre-leukemic Ikaros null thymocytes were compared to changes in RNA expression in DP thymocytes undergoing leukemic progression (pre-leukemic stage I and II)16. A common signature of up- or down-regulated genes (1760 and 2193, respectively) was defined by a change in both H3K36me3 and RNA expression (Fig. 6a, plotted from most to least changed). Importantly, this signature was progressively deregulated during leukemogenesis with most genes directly associated with Mi-2β or the Ikaros family of proteins (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 6. Loss of Ikaros-mediated effects on gene expression reveals two functionally opposing mechanisms of NuRD-dependent transcriptional regulation.

(a) A pre-leukemic signature is defined in Ikaros-deficient DP thymocytes by loss (Down) or gain (Up) in transcriptional elongation (H3K36me3) and RNA expression. TSS-centered distribution of H3 modifications in down- and up-regulated genes in wild-type (wt) and Ikaros null (ΔIk-1 and ΔIk-2) DP thymocytes ordered from the most to the least significant change in expression. RNA expression of these genes at the pre-leukemic and leukemic stages (SI-III) as well as during normal T cell differentiation (DN1-4, DP, CD4 and CD8) is shown by heat maps. (b) Cumulative effect on H3K9Ac, RNA polII and H3K27me3 at the TSS of down- and up-regulated genes. (c) Representative examples of down- and up-regulated genes shown by IGV browser display of Ikaros, Aiolos, Mi-2β and HEB peaks identified using the MACS algorithm with appropriate input controls45. Differential enrichment for Mi-2β, RNA polII and H3 modification peaks between WT vs. Ikaros null chromatin was also obtained using MACS. In comparative analyses (wt vs. ΔIk or ΔIk vs. wt), the presence of reads indicates a signal increase, whereas the absence indicates a lack of signal change between the two conditions.

Down-regulated genes displayed a strong reduction in H3K9Ac-K14Ac modification as well as a reduction in RNA polII occupancy (Fig. 6a,b, Down) that was more profound in the vicinity of Mi-2β or Ikaros, Aiolos sites (Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 5c). Genes in the up-regulated group were transcriptionally poised in wild-type chromatin with H3K4me3, H3K9Ac marks and with low frequencies of RNA polII occupancy at the TSS and of the H3K36me3 elongation mark in the gene body (Fig 6a, Up). An increase in RNA polII occupancy was observed in the up-regulated genes in spite of a decrease in H3K9Ac-K14Ac histone modification. Nonetheless, the decrease in H3K9Ac-K14Ac was lower to that seen in down-regulated genes (Fig 6a, and Supplementary Fig. 5b). In about a third of the up-regulated genes, H3K27me3 was present in wild-type and lost in the Ikaros null chromatin (Fig. 6a, Up and Supplementary Figs. 5b, 6b and Supplementary Table 3). Notably, genes with the most significant increase in expression were frequently marked by H3K27me3 in wild-type chromatin (Fig. 6a, Up).

Analysis of gene ontologies associated with the up- and down-regulated gene subsets have revealed a division of labor for the NuRD complex during T cell development (Supplementary Fig. 6). Pathways associated with T cell differentiation, activation, hematopoiesis, lymphoid and immune system development and highly enriched by the Ikaros–Mi-2β–NuRD complex were down-regulated, whereas pathways supporting metabolism, and frequently enriched by the (Ikaros-free) Mi-2β–NuRD complex, were strongly up-regulated (Supplementary Fig. 6). Key T cell differentiation genes such as Cd4, Cd8, Rag1 and Rag2, Il4ra, Ifngr1, Ccnd3, Bcl2l1, Fas, Socs1,Tox, Pten, Ptprf were identified within the Ikaros–Mi-2β–NuRD down-regulated group. A significant fraction of these genes were also directly associated with the E2A partner, HEB (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 7). Genes supporting basic cellular pathways in metabolism, cell growth, migration and proliferation, such as Nans, Nsun2, Rrn3, Alox5p, Adcy7, Insgfr1 and 2, Elovl6, Trib1, Ddr1, Vcl1, Dock1, Sdc1, Mmp14, Maged1, Ccnd1, Myc, Smo and Smad1, were identified in the Mi-2β-NuRD up-regulated group (Supplementary Fig. 6 and 7).

Taken together these studies indicate that during T cell differentiation the NuRD complex regulates a range of genetic programs associated with differentiation, proliferation and growth by engaging functionally disparate mechanisms. However, the presence of Ikaros DNA binding activity in the NuRD complex restricts its action to the lymphoid differentiation programs and in the maintenance of gene expression. Loss of Ikaros unleashes NuRD activity to the full range of these genetic programs thereby interfering with normal differentiation and causing aberrant growth and proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Discussion

Our studies provide first insight into a mechanism that divides the labor of chromatin remodeling complexes between differentiation-specific and general cellular tasks such as proliferation and growth. We show that targeting through lineage-specific DNA binding factors positioned chromatin remodelers for regulation of genetic programs supporting differentiation while preventing their participation in programs that oppose differentiation. We also show that while tethered to lineage-specific genes, the activity of chromatin remodeling complexes was controlled by the DNA binding activity of associated lineage-specific factors, possibly serving as a barrier that limits their chromatin access. This potentially poised functional state provides an explanation for the steady state association of restrictive chromatin modifiers with transcriptionally active genes3.

In the chromatin of both wild-type and Ikaros null thymocytes, the NuRD complex was targeted to permissive chromatin, marked predominantly by H3K4me3, generated by the trithorax group of chromatin regulators33. The presence of Ikaros-type proteins in the NuRD complex further restricts this targeting to permissive chromatin that contains binding sites for Ikaros family proteins and the E-box and Runx family members, found frequently in lymphoid-specific regulatory elements. Here, the chromatin remodeling and histone deacetylase activities of the NuRD complex were kept in check by Ikaros proteins, likely providing a physical barrier through DNA binding, that limits access to the nucleosome and its acetylated histone tails either by competition or by altering Mi-2β conformation and enzymatic activity. At active lymphoid genes, reduction in Ikaros DNA binding increased local access by Mi-2β, nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylation and interfered with the RNA polII transcription cycle and gene expression. In the absence of Ikaros, the related family member Aiolos with similar DNA binding specificity still targeted the NuRD complex to these locations and limited local chromatin access, albeit not to the extent of both factors working together. Consistent with this model, more severe Ikaros-related phenotypes are observed in mice with combined Ikaros and Aiolos null mutations or in mouse and human with Ikaros dominant-negative mutations that interfere with activity of both factors9,16,34.

Loss in Ikaros DNA binding allows more access to Mi-2β not only at lymphoid gene targets, but also at transcriptionally poised genes involved in cell growth and metabolism. Gain of Mi-2β at these sites, normally present within permissive or bivalent chromatin, appears to promote the RNA polII transcription cycle and gene activation. Notably, a fraction of these normally repressed genes were marked by occupancy with the PRC2 complex, and gain in Mi-2β occupancy antagonized this chromatin modifier. Antagonistic interactions between PICKLE, the plant homologue of Mi-2β, and the polycomb protein CURLY LEAF were recently shown to control expression of stem cell and meristem genes in Arapidopsis35. While these genes do not contain significant Ikaros or other lymphoid-specific binding motifs they contain basic transcriptional motifs including binding sites for the CTCF insulator. An interaction between Mi-2β–NuRD and the cohesin complex that also interacts with CTCF was previously reported36,37, and was also detected in our Mi-2β–NuRD complex purification from thymocytes. Functional interactions between the cohesin and the basic transcription mediator complexes that enable communication between enhancer and core promoters in embryonic stem cells were recently shown38. A potential role for Mi-2β in regulating insulator function and possibly promoter-enhancer communication through interactions with the cohesin-CTCF and cohesin-mediator complexes present other mechanisms through which the NuRD complex participates in the induction of poised genes.

Change in the DNA binding activity of Ikaros family proteins present within the NuRD complex, may be the mechanism through which activity of this complex and expression of functionally opposing genetic programs is modulated from the most primitive lymphoid progenitor to the mature effector lymphocyte. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional events that target Ikaros expression and activity39-42, are likely to provide complexity in the regulation of the NuRD complex and may be key to successful transitions through the proliferative and quiescent stages of lymphocyte differentiation.

Association of the Ikaros-NuRD complex with both transcriptionally active and poised genes in thymocytes provides us with a snap shot of their dual potential as activators and repressors of gene expression, which is likely dictated by the activity of neighboring factors. For example, Ikaros has been perceived as a repressor of Cd4 gene expression in DN thymocytes18, whereas our current studies indicate that it also serves to maintain Cd4 gene expression in DP thymocytes. Ikaros association with the inactive Cd4 locus at the DN stage may antagonize Mi-2β remodeling, thus promoting activity of negative regulators, such as the PRC2 complex. Reduction in Ikaros DNA binding activity at the DN stage may increase Mi-2β remodeling that antagonizes local repressors and activates the Cd4 gene. Reinstating Ikaros DNA binding activity and the Ikaros-NuRD complex at the transcriptionally active Cd4 locus in quiescent DP thymocytes bestows Ikaros a new role as a guardian of Cd4 gene expression at this developmental stage. Reduction in Ikaros activity at this DP stage or during subsequent transitions again increases Mi-2β chromatin remodeling activity, which at this stage may antagonize the basal transcription machinery and thereby cause Cd4 gene inactivation.

An uncontrolled gain-of-function of the NuRD complex in DP thymocytes brings about disparate epigenetic effects that disrupt stage-specific activation and repression of genetic programs required for normal differentiation. Targeting of chromatin modifying enzymes for therapeutic intervention, especially histone deacetylases, is the focus in treating T cell leukemias as well as debilitating immune disorders43,44. Understanding the roles played by HDAC complexes in the epigenetic regulation of differentiation versus cell growth and proliferation through their interactions with lineage-specific DNA binding factors and other epigenetic regulators is important for our ability to manipulate cell fate choices and their aberrant manifestations in an intelligent fashion.

METHODS

Animals

Ikaros null mice (ΔIk), Ikaros dominant negative (IkDN) and WT strains were bred and housed under pathogen-free conditions as described14. Animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the MGH Subcommittee on Research Animal Care (SRAC). Mice were sacrificed at 3-5 weeks of age (for pre-leukemic: stage I-II) and >10 weeks (for leukemic: stage III- upon Notch signaling activation). Staging of mutant thymi was determined by phenotypic analysis of DP thymocytes as described16. Thymocytes were used for cellular, gene expression and chromatin studies. Ikaros-Mi-2β-flag mice10,39 and CD2-Flag-Ikaros transgenic mice were used for flag-tag protein purification from primary thymocytes as described7.

Antibody reagents

Cocktails of home-produced monoclonal antibodies were used for Ikaros (4E9, Ik14), Mi–2β (16G4, 2G8, 17H11) and Aiolos (9D10) ChIP with WT and ΔIk chromatin 7,17,18. For HEB, the sc357 antibody from Santa Cruz was used. For RNA polII and histone modification studies: anti-H3K4me3 (Abcam ab8580 or Millipore 07-473), anti-H3K4me2 (Millipore 07-030), anti-H3K4me1 (Abcam ab8895), anti-H3K9Ac-K14Ac (Millipore 06-599), anti-H3K27me3 (Millipore 07-449), and anti-H3K36me3 (Abcam ab9050) and anti-RNA polII S5 (Abcam ab5131) were used for ChIP with WT and ΔIk chromatin. Phenotypic analysis and sorting of DP thymocytes was performed by flow cytometry using FACSCanto (BD) or MoFlo (Cytomation). The antibodies used in these studies were CD4-PE-Cy5.5 (or CD4-PE-Cy7), CD8α-FITC, TCRβ-APC and CD5-PE, CD25-PE, HSA-PE, CD69PE, Thy1.2-PE, CD62L-APC and CD44-APC as described16.

ChIP-Seq

ChIP was performed on DP-enriched thymocytes (1×107-1×108) isolated from 3-5 week old WT and Ikaros null mice with 3-5 μg of antibodies to Ikaros, Mi–2β, Aiolos, HEB, H3K4me3, H3K9Ac-K14Ac , H3K27me3, H3K36me3 and RNA polII S5. Sequencing libraries were generated from 10-20 ng of ChIP or input DNA using either an Illumina kit or a home-made kit using reagents from NEB. Prior to and after library amplification, target enrichment in ChIPed DNA material was validated by candidate target approach as previously described16,18. Sequencing was performed on a Genome Analyzer II (Illumina).

ChIP-Seq data analysis

Single-ended 32bp sequences were mapped to the mouse genome assembly mm9 using the ELAND alignment tool in GApipeline accepting no more than two mismatches. Uniquely aligned tags were selected, converted to bed files and after read normalization were analyzed by the peak calling software MACS45 for robust and high resolution enrichment peak predictions. The algorithm was applied, using a 2d sliding window across the genome to find candidate peaks with significant tag enrichment according to Poisson distribution at a default P-value of 10−05 with input control data (Supplementary Fig. 9). Biological replicates for Ikaros and Mi-2β ChIP-Seq experiments were performed, verified by comparing enriched peaks and then combined into a single dataset.

To detect differential regulation of Mi–2β and H3-modification enrichment between WT and ΔIk chromatin, three steps were taken. First, peak calling with MACS was conducted between input control and the WT or ΔIk sample, respectively. Second, direct comparison between the WT and ΔIk sample was conducted with MACS. Third, peaks called in the second step were filtered though the peak list from the first step based on binding site overlap. For example, any peaks identified as up-regulated in ΔIk sample were also significant when ΔIk was compared against its input control; any peaks identified as up-regulated in WT were also present in the WT peak list deduced by comparing the WT sample to its input control (Supplementary Fig. 9). To test if the difference in the number of sequencing reads between two conditions (e.g. WT and ΔIk) affected the final differential regulated peak list and to what extent, we used random sampling to draw equal number of reads from each condition and run the above three step analyses. A very similar peak list in terms of number of called peaks and peak locations was obtained using either method.

Binding site profiling and GO analysis

All of the genome-wide annotations and statistics of protein–DNA interaction patterns from ChIP-seq data were performed with in-house scripts of the R and Perl programming language. Binding sites were assigned to the nearest transcripts based on the distance from gene Transcriptional Starting Site (TSS) to the peak summit of binding sites. Enriched DNA motifs at Ikaros, Aiolos and Mi–2β sites were obtained using the HOMER (Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif EnRichment) software (http://biowhat.ucsd.edu/homer/introduction/programs.html). Genomic sequences 100-300 bp upstream or downstream of Ikaros or Aiolos binding peaks were scrutinized to identify motifs present in these fragments on the basis of their statistical enrichment. GO analysis of target genes was conducted using the Functional Annotation Tool of the DAVID software.

Hierarchical clustering

Genomic binding patterns from multiple ChIP-seq studies were deduced by Ward's hierarchical clustering22 using the R statistical platform with hclust function. Specifically, normalized tags located at significant binding sites called by MACS were counted for each base position for each ChIP-seq experiment. Then the signal intensity pattern at these position-indexed tag numbers was tested relative to other genomic features, such as TSS sites and normalized ChIP-seq peaks from other factors. The tag numbers with positions falling within 6 kb regions centered around each genomic feature were pulled out for clustering. Numbers for each 6 kb region formed a row, and all rows were stacked together to form a matrix as input for the hclust function in R after percentage conversion. This step of percentage conversion is necessary for comparison of the signal intensities between two conditions (e.g. WT and ΔIk) and captures the genomic location and pattern of the ChIP-Seq signal simultaneously. Specifically for two-condition comparison, tag numbers in each row were converted to percentage fraction relative to the total number of tags. To obtain a combinatory pattern from multiple ChIP-seq studies, matrices from all ChIP-seqs were juxtaposed into a larger matrix that was used as input for hierarchical clustering by the Ward method.

Gene expression microarrays

DP thymocytes from WT, ΔIk and IkDN mice were obtained at different stages of leukemogenesis (stage I, stage II, and stage III) as described16 and profiled for RNA expression. A common signature of up- and down-regulated genes defined by both chromatin and RNA expression changes across Ikaros mutant compared to WT DP thymocytes was deduced. Comparative analysis of gene expression profiles from WT and Ikaros mutant DP was performed by the Bioconductor limma package46. Likelihood of over-representation of functional categories in the up- or down-regulated gene list relative to a background of all array genes was calculated by Fishers’ exact test. Genes with an absolute fold change in transcript level exceeding 1.5 and multiple test-adjusted P-value less than 0.05 were compared to the H3K36me3 changes occurring between WT and ΔIk chromatin at P-value of 10−5. Gene expression datasets obtained from sorted thymocyte subsets (e.g, DN1, DN2, DN3, pre-DP, blDP, smDP, CD4SP and CD8 SP) as described by47 were used to generate a heatmap of gene expression during T cell development for the subset of genes deregulated upon loss of Ikaros at the pre-leukemic state (stage I and II).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH R37 AI33062, NIH R01CA158006 and NIH 9R01CA162092. AFJ was supported by NIH2T32AI007529. Protein micro-sequencing was performed at the Microchemistry and Proteomics Facility, Harvard University, Cambridge, and at the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility at Harvard Medical School, Boston. High throughput DNA sequencing and RNA profiling was performed at the Bauer Center for Genomic research Harvard University, Cambridge. We thank P. Gomez for providing Mi-2β protein expression analysis in thymocytes, the Kingston lab (Department of Molecular Biology, MGH) for hSWI-SNF complex and help with setting up the mononucleosome and 5S array assays, I. Joshi for help with cell sorting, B. Czyzewski for mouse husbandry and B. Morgan for discussions of the project and critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions

J.W.Z., A.F.J., T.N., M.D., E.J.H., J.S., F.L., M.K., T.Y. designed and performed experiments and analyzed experimental data. H.T.P. designed expression studies on WT thymocyte subsets and provided data for analysis. F.G. and K.G supervised research and analyzed data. J.W.Z and K.G. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Zhao K. Active chromatin domains are defined by acetylation islands revealed by genome-wide mapping. Genes Dev. 2005;19:542–552. doi: 10.1101/gad.1272505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, et al. Genome-wide mapping of HATs and HDACs reveals distinct functions in active and inactive genes. Cell. 2009;138:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong JK, Hassig CA, Schnitzler GR, Kingston RE, Schreiber SL. Chromatin deacetylation by an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling complex. Nature. 1998;395:917–921. doi: 10.1038/27699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, LeRoy G, Seelig HP, Lane WS, Reinberg D. The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell. 1998;95:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho L, Crabtree GR. Chromatin remodelling during development. Nature. 2010;463:474–484. doi: 10.1038/nature08911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J, et al. Ikaros DNA-binding proteins direct formation of chromatin remodeling complexes in lymphocytes. Immunity. 1999;10:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Neill DW, et al. An ikaros-containing chromatin-remodeling complex in adult-type erythroid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7572–7582. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7572-7582.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgopoulos K. Haematopoietic cell-fate decisions, chromatin regulation and ikaros. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida T, Ng SY, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Georgopoulos K. Early hematopoietic lineage restrictions directed by Ikaros. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:382–391. doi: 10.1038/ni1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng SY, Yoshida T, Zhang J, Georgopoulos K. Genome-wide lineage-specific transcriptional networks underscore Ikaros-dependent lymphoid priming in hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity. 2009;30:493–507. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan B, et al. Aiolos, a lymphoid restricted transcription factor that interacts with Ikaros to regulate lymphocyte differentiation. Embo J. 1997;16:2004–2013. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winandy S, Wu P, Georgopoulos K. A dominant mutation in the Ikaros gene leads to rapid development of leukemia and lymphoma. Cell. 1995;83:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JH, et al. Selective defects in the development of the fetal and adult lymphoid system in mice with an Ikaros null mutation. Immunity. 1996;5:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumortier A, et al. Notch activation is an early and critical event during T-Cell leukemogenesis in Ikaros-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:209–220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.209-220.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gómez-del Arco P, et al. Alternative promoter usage at the Notch1 locus supports ligand-independent signaling in T cell development and leukemogenesis. Immunity. Immunity. 2010;24:685–698. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams CJ, et al. The chromatin remodeler Mi-2beta is required for CD4 expression and T cell development. Immunity. 2004;20:719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naito T, Gomez-Del Arco P, Williams CJ, Georgopoulos K. Antagonistic interactions between Ikaros and the chromatin remodeler Mi-2beta determine silencer activity and Cd4 gene expression. Immunity. 2007;27:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avitahl N, et al. Ikaros sets thresholds for T cell activation and regulates chromosome propagation. Immunity. 1999;10:333–343. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer A, Adoro S, Park JH. Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4- versus CD8-lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:788–801. doi: 10.1038/nri2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koipally J, Georgopoulos K. A molecular dissection of the repression circuitry of Ikaros. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27697–27705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward JH. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am Stat. Assoc. 1963;58:236–242. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ernst J, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Zhao K. The genomic landscape of histone modifications in human T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15782–15787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein BE, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molnar A, Georgopoulos K. The Ikaros gene encodes a family of functionally diverse zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8292–8303. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahm K, et al. Helios, a T cell-restricted Ikaros family member that quantitatively associates with Ikaros at centromeric heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 1998;12:782–796. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollenhorst PC, Shah AA, Hopkins C, Graves BJ. Genome-wide analyses reveal properties of redundant and specific promoter occupancy within the ETS gene family. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1882–1894. doi: 10.1101/gad.1561707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins and lymphocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/ni1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kee BL. E and ID proteins branch out. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:175–184. doi: 10.1038/nri2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones ME, Zhuang Y. Stage-specific functions of E-proteins at the beta-selection and T-cell receptor checkpoints during thymocyte development. Immunol Res. 2011;49:202–215. doi: 10.1007/s12026-010-8182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin YC, et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:635–643. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gould A. Functions of mammalian Polycomb group and trithorax group related genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:488–494. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullighan CG, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aichinger E, Villar CB, Di Mambro R, Sabatini S, Kohler C. The CHD3 Chromatin Remodeler PICKLE and Polycomb Group Proteins Antagonistically Regulate Meristem Activity in the Arabidopsis Root. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1047–1060. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakimi MA, et al. A chromatin remodelling complex that loads cohesin onto human chromosomes. Nature. 2002;418:994–998. doi: 10.1038/nature01024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wendt KS, et al. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature. 2008;451:796–801. doi: 10.1038/nature06634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kagey MH, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaufmann C, et al. A complex network of regulatory elements in Ikaros and their activity during hemo-lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 2003;22:2211–2223. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gomez-del Arco P, Maki K, Georgopoulos K. Phosphorylation controls Ikaros's ability to negatively regulate the G(1)-S transition. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2797–2807. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2797-2807.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomez-del Arco P, Koipally J, Georgopoulos K. Ikaros SUMOylation: switching out of repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2688–2697. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2688-2697.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mavrakis KJ, et al. A cooperative microRNA-tumor suppressor gene network in acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). Nat Genet. 2011;43:673–678. doi: 10.1038/ng.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masetti R, Serravalle S, Biagi C, Pession A. The role of HDACs inhibitors in childhood and adolescence acute leukemias. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:148046. doi: 10.1155/2011/148046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mullighan CG, et al. CREBBP mutations in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;471:235–239. doi: 10.1038/nature09727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2004;3:1–25. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffith AV, et al. Spatial mapping of thymic stromal microenvironments reveals unique features influencing T lymphoid differentiation. Immunity. 2009;31:999–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.