Abstract

The observed Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) between fluorescently labeled proteins varies in cells. To understand how this variation affects our interpretation of how proteins interact in cells, we developed a protocol that mathematically separates donor-independent and donor-dependent excitations of acceptor, determines the electromagnetic interaction of donors and acceptors, and quantifies the efficiency of the interaction of donors and acceptors. By analyzing large populations of cells, we found that misbalanced or insufficient expression of acceptor or donor as well as their inefficient or reversible interaction influenced FRET efficiency in vivo. Use of red-shifted donors and acceptors gave spectra with less endogenous fluorescence but produced lower FRET efficiency, possibly caused by reduced quenching of red-shifted fluorophores in cells. Additionally, cryptic interactions between jellyfish FPs artefactually increased the apparent FRET efficiency. Our protocol can distinguish specific and nonspecific protein interactions even within highly constrained environments as plasma membranes. Overall, accurate FRET estimations in cells or within complex environments can be obtained by a combination of proper data analysis, study of sufficient numbers of cells, and use of properly empirically developed fluorescent proteins.

Keywords: Interferon, FRET, Receptor, Equilibrium, Janus kinase

1. Introduction

1.1. Analyzing protein:protein interactions in cells

Studying protein:protein interactions is crucial to understand how signals are propagated and integrated into signaling networks in cells. The vast majority of technologies that are used to analyze protein:protein interactions require the separation of these proteins from the complex biological environments in which they reside. Although a detailed understanding of these interactions in chemically defined conditions is important, these interactions must also be observed in their natural environments to correlate in vitro data with in vivo data and to realize any modifications of this interaction by components in intact cells. The implementation of variants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) greatly facilitated the comparison of protein interactions in vivo and in vitro.

1.2. The interferon-gamma receptor complex

Some protein complexes cannot be purified intact from their biological environment; this prevents a detailed analysis of their structure using current technologies, and requires noninvasive technologies to determine their structure. Among these protein complexes are receptors for transmembrane cellular receptors such as growth factors, interleukins, and interferons (IFNs). The IFN-γ receptor complex is composed of two genetically distinct transmembrane polypeptide chains [1–4]. IFN-γR1 binds the IFN-γ ligand with its extracellular domain; its intracellular domain binds the tyrosine kinase Jak1 to empower it with enzymatic activity. IFN-γR2 binds IFN-γ by its extracellular domain only after IFN-γ binds to IFN-γR1; the intracellular domain of IFN-γR2 binds the tyrosine kinase Jak2 to similarly gain enzymatic activity. Unlike observations performed in vitro implying that neither IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 nor IL-10R1 and IL-10R2 interact, our group used noninvasive fluorescent technologies to determine that the both the interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) receptors and the interleukin-10 (IL-10) receptors interact in vivo [5–7].

Because the IFN-γ receptor complex is structurally different in vivo vs. in vitro, and the pharmacological target of the receptor is in vivo, we felt that further analysis of receptor interactions must be done in vivo. We used a mutagenic approach to find that significant FRET between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 requires (1) that the extracellular domains of IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 be species-matched, and (2) that the Jak1 association site of IFN-γR1 be intact [6].

1.3. Variation of protein levels in cells

Inspection of flow cytometric data from a wide variety of systems reveals that the levels of a given protein can vary considerably from cell to cell within a population. Similarly, we found early on that the fluorescence emission of cells expressing a given pair of fluorescent receptors varies from point to point within a cell as well as among cells within a transfected population (unpublished). Furthermore, the observed FRET between a given pair of receptor chains [7] and between cytoplasmic components of an RNA stability complex [8,9] varies within each population of cells. Although variations of protein levels and of FRET are unavoidable consequences of analyzing protein:protein interactions in cells that must be addressed, we hypothesized that quantifying this variation by deconvolution of populations of spectra will assist our understanding of how a given interaction may vary throughout a population of cells and that this analysis will reveal the optimal conditions that produce a desired interaction.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Restriction endonucleases, shrimp alkaline phosphatase and T4 DNA Ligase was purchased from New England BioLabs. Recombinant Taq DNA polymerase was purified as described previously [10]. Turbo Pfu DNA polymerase was purchased from Stratagene. Polyethyleneimine (PEI), in the linear 25 KDa form was purchased from Fluka as a powder. Solutions of PEI were prepared by dissolution in water, for 24 h, titration with hydrochloric acid until turbidity has disappeared for 1 h, followed by neutralization with NaOH and filtration; aliquots were stored at –70 °C until needed [11]. Diethyldioctadecylammonium bromide (DDAB) and dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich as powders, dissolved in absolute ethanol, and stored at –20 °C until used. Fluorescent proteins (with amino-terminal hexahistidine tags) were purified as described previously [12] with further purification by reverse-phase chromatography.

2.2. DNA constructions

Ligations were performed with T4 DNA Ligase. All PCR products were sequenced after they were subcloned into their host vectors and suitable isolates identified. Plasmids are purified using the alkaline lysis method, except that 7.5 M ammonium acetate instead of 5 M potassium phosphate is used. The synthesis of pEF3-IFN-γR1/cR1/STOP (hereafter referred to as pEF3-IFN-γR1), pcDNA3-FLAG-IFN-γR2/cR2 (hereafter referred to as pc3-FL-IFN-γR2), pcDNA3-FL-IL-10R2/IL-10R2/STOP (hereafter referred to as pc3-FL-IL-10R2), pEF3-IFN-γR1/ECFP, pEF3-IFN-γR1/EGFP, pEF3-IFN-γR1/EYFP, pc3-FL-IFN-γR2/ECFP, pc3-FL-IFN-γR2/EGFP, and pc3-FL-IFN-γR2/EYFP is described elsewhere [5,6]. The details of constructions synthesized with these starting plasmids are described in Supplemental Text 1.

2.3. Cell lines and transfections

Human kidney epithelial 293T and 293TT cells and green monkey kidney epithelial COS-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% (v:v) fetal bovine serum. All cell lines were grown in HEPA-filtered tissue culture incubators under an environment of 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% relative humidity.

Multiple transfection protocols were used according to the cell line used as well as the favored and optimized method at the time. Unless explicitly stated, all transfections were done with 2 μg each co-transfected plasmid or 4 μg of tandem vector per well of cells (about 1 million) plated at approximately 70% confluence in six-well tissue culture dishes. The transfection conditions are described in Supplementary Text 2.

2.4. Fluorescence confocal spectroscopy, spectral deconvolution and data analysis

Details of the confocal microscope and spectrophotometer are described in Supplementary Text 3 but were published previously [6,8,9]. Spectroscopic values for the various fluorophores were obtained from published literature [12–16]. Excitation and emission spectra were generously provided either by the webpage of the laboratory of Tsien, by members of the laboratories of Tsien, Shaner and Campbell, or were digitized from published figures.

The process of adding scalable reference spectra to optimize a fit to an obtained cellular emission spectrum, after correcting for spectrometer noise and laser emission, is described elsewhere [7,8].

In Supplementary Text 4, we describe the protocol we now follow to estimate the relative levels of donor, acceptor, donor:acceptor pairs, the FRET efficiency, the fractions of donor or of acceptor in paired complexes, and the efficiencies of coupling of donor and acceptor.

2.5. Fluorescence Lifetime imaging microscopy

A 405 nm picosecond diode pulse laser with a 1 kHz repetition rate, (Courtesy of Prof. Sergei Vinogradov, University of Pennsylvania Department of Chemistry) was used to excite the enhanced sapphire fluorescent protein. A Chameleon Ultra II Ti:Sapphire oscillator (Coherent, Inc., Santa Clara, CA., USA), with a pulse width of ~100 fs and a 80 MHz repetition rate was tuned to 880 nm to excite the teal fluorescent protein.

Samples were placed on 1 mm coverslips and fluorescence emission was obtained on a scanning confocal microscope with the sample and stage mounted on an inverted, epi-illumination microscope (Nikon Diaphot 300). A Nikon FLUOR 40, NA = 1.3 objective focused the excitation light and directed the fluorescence emission to either a monochromator (Acton Research) equipped with a back-illumination liquid nitrogen cooled CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) for spectral measurement to confirm the identity of the excited fluorescent species or to a single photon counting board, SPC 730 (Becker & Hickl, Inc.) to record the fluorescence lifetime decay curve. Both the CCD camera and the time-resolved photon counting board were coupled to Windows-based personal computers to process data.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The arithmetic means and standard deviations of either acceptor levels, donor levels, acceptor:donor molar ratio, acceptor:donor pairs, FRET efficiency or reaction quotients were calculated using SigmaPlot 10.0 (Systat Software, Inc). These values are shown graphically as two-dimensional error bars that bisect at the pairwise means. Statistical significance of two compared populations (p) were calculated by a two-tailed Student's t-test, with the assumption that the compared populations has different sample numbers and variances. Statistical distinctiveness of the populations was assumed when the obtained p value was less than 0.05, inferring that the two datasets would arise from a single population less than 5% of the time measurements are taken. Calculations of p were done with Microsoft Excel 2010. All averages and p determinations are reported in Supplementary Text 10. The p values are reported in the text as an ordered pair, in which the first term describes the p value of the terms along the x-axis, and the second term describes the p value of the terms along the y-axis.

3. Results

3.1. Resolving variations in FRET efficiencies

When we measured FRET efficiency between GFP- and EBFP-labeled IFN and IL-10 receptors, we observed considerable variation of the spectra and of the FRET efficiency throughout the transfected population [7]. We hypothesized that resolving FRET efficiencies among a population of cells by various dimensions will explain what underlies the variation in FRET efficiency.

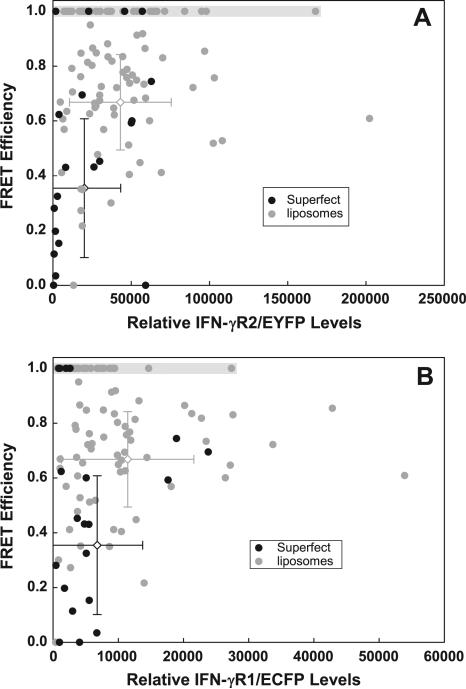

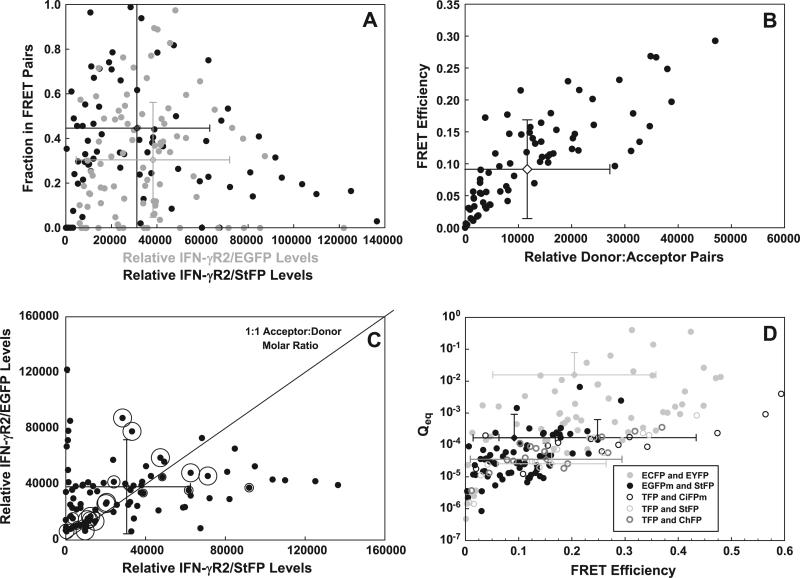

To address this, we transiently transfected 293T cells with the tandem vector CMVγR2EYFP+EF3γR1ECFP, examined many cells within each population using our new empirical protocol, and resolved this large pool of data along various parameters. Twenty cells were analyzed in a population transfected with the Superfect reagent (Fig. 1, black circles), while another 100 cells were analyzed in five populations transfected with various amounts of custom-made DDAB:DOPE liposomes (Fig. 1, gray circles). Even though the average levels of receptor chains and of observed FRET efficiency from the two populations achieved statistical significance at the 5% threshold (p = {0.003, 0.0002} and {0.047, 0.0002} for Fig. 1A and B, respectively), the data from the two transfection reagents overlapped sufficiently that the data were combined. Furthermore, the dispersion of data by FRET efficiency as a function several parameters yielded spatially cohesive data. We restrict our discussion to cells exhibiting incomplete FRET efficiency: a subpopulation of transfected cells exhibited 100% FRET efficiency (gray background) and are discussed in Supplementary Text 5.

Fig. 1.

Variation of FRET between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2. 293T cells were transfected with the tandem vector CMVγR2EYFP+EF3γR1ECFP, and were excited with both the 488 nm laser to preferentially excite EYFP and with the 442 nm laser to preferentially excite ECFP. Black circles are FRET values derived from cells transfected by Superfect; gray circles are FRET values obtained from cells transfected with DDAB:DOPE liposomes. (A) The FRET efficiency of each cell in the population is plotted as a function of relative IFN-γR2/EYFP levels. (B) The FRET efficiency of the above populations is plotted as a function of relative IFN-γR1/ECFP levels. Shaded regions in (A) and (B) outline cells exhibiting unusually high FRET efficiency between IFN-γ receptor chains (See Supp. Text 5). Error bars in (A) and (B) indicate the mean and standard deviation of the relative protein levels (horizontal) and FRET efficiency (vertical) of the cells transfected with Superfect (black bars) and liposomes (gray bars).

3.1.1. Reduced levels of proteins lower the observed FRET efficiency

In cells exhibiting incomplete FRET, we found that cells exhibiting lower FRET efficiencies almost always had low relative levels of either IFN-γR2/EYFP (Fig. 1A) or IFN-γR1/ECFP (Fig. 1B). As the levels of both receptor chains increased, far fewer cells with poor FRET efficiency were observed. The optimal FRET efficiency approached 90% in this population. We conclude that lower expression of one of the fluorescently labeled receptor chains contributes to lower FRET efficiencies in some cells.

We observed that a large fraction of cells transfected with Superfect exhibited poor FRET efficiencies. To understand why this occurred, we compared the relative levels of donor and acceptor proteins in each of the 120 cells in these transfected populations. Within most cells in the population, especially those transfected with DDAB:DOPE liposomes, the relative levels of IFN-γR2/EYFP exceeded the relative levels of IFN-γR1/ECFP, while in cells with poor FRET efficiency, IFN-γR1/ECFP levels were comparable to or exceeded those of IFN-γR2/EYFP (Supplementary Fig. 4). In Supplementary Text 6, we discuss these data in more detail.

3.1.2. Extreme acceptor:donor ratios lower the observed FRET

Observing that low FRET efficiencies were seen in cells when a molar excess of IFN-γR1/ECFP was present (Supp. Fig. 4), we hypothesized that the acceptor:donor molar ratio affects FRET efficiency in live cells in the same way as it does in vitro. We tested this hypothesis by analyzing the FRET efficiency with various pairs of proteins to ensure that a decrease in observed FRET efficiency seen with excess donor was a general property. In Fig. 2, we resolved FRET efficiency in each population as a function of the calculated molar ratio of EYFP to ECFP.

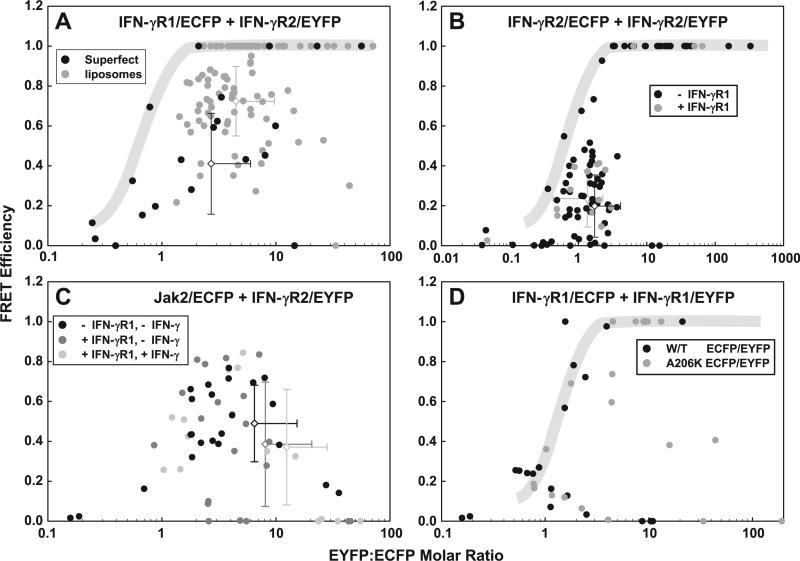

Fig. 2.

FRET efficiency at various acceptor:donor ratios for various protein pairs. FRET efficiency and the ratio of ECFP-tagged protein and EYFP-tagged protein were calculated for various protein pairs. (A) 293T cells are transfected with CMVγR2EYFP+EF3γR1ECFP (same data from Figs. 1) using either Superfect (black circles) or DDAB:DOPE liposomes (gray circles). (B) COS-1 cells are transfected with CMVγR2ECFP+CMVγR2EYFP, either in the absence of cotransfected pEF3-IFN-γR1 (black circles) or in its presence (gray circles). (C) 293T cells are transfected with pc3-Jak2/ECFPm and pc3-IFN-γR2/EYFPm alone (black circles) or also with pEF3-IFN-γR1 (dark gray circles). The latter population was treated with 1000 U/mL IFN-γ for at least 5 min and more cells analyzed (light gray circles). (D) 293T cells were transfected with either EF3γR1ECFP+EF3γR1EYFP (black circles) or EF3γR1ECFPm+EF3γR1EYFPm (gray circles). The shaded regions in (A), (B) and (D) outline cells exhibiting unusually high FRET efficiency between IFN-γ receptor chains (See Supp. Text 5). The error bars are colored to match the color of its corresponding dataset.

We chose to analyze the pair IFN-γR2/EYFP and IFN-γR1/ECFP (Fig. 2A) to reuse the cells from Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4. We chose to analyze the pair IFN-γR2/EYFP and IFN-γR2/ECFP using tandem vector CMVγR2ECFP+CMVγR2EYFP to see if two identical proteins exhibit an optimal FRET efficiency at an equimolar ratio. (Fig. 2B, black circles). Simultaneously, we analyzed cells contemporaneously transfected with the tandem vector CMVγR2ECFP+CMVγR2EYFP+EF311S to see if the coexpression of IFN-γR1 affected the interaction between IFN-γR2/EYFP and IFN-γR2/ECFP (Fig. 2B, gray circles). We also analyzed a pair composed of a transmembrane receptor IFN-γR2/EYFP and its cytosolic tyrosine kinase Jak2/ECFP because this pair forms a complex whose interaction survives immunoprecipitation [17–20], and because one protein in this pair is not a transmembrane receptor. We expressed this pair as plasmids pc3-Jak2/ECFP and pc3-IFN-γR2/EYFP either by themselves (Fig. 2C, black circles) or with plasmid pEF3-IFN-γR1 that has no fluorescent protein present (Fig. 2C, gray circles) to see if IFN-γR1 alters the interaction between IFN-γR2 and Jak2. The cells from the latter population were either untreated (Fig. 2C, dark gray circles) or were treated with IFN-γ (Fig. 2C, light gray circles) to see if the Jak2/ECFP:IFN-γR2/EYFP pair changes its conformation when IFN-γ binds the transfected IFN-γR1 chain. Finally, we analyzed the interaction between two IFN-γR1 chains by expressing the tandem vector EF3γR1ECFP+EF3γR1EYFP, using either the original ECFP and EYFP cDNAs (Fig. 2D, black circles) or cDNA's mutated to discourage oligomerization of ECFP and EYFP (Fig. 2D, gray circles).

Except for the interaction between IFN-γR2 and Jak2, we always observed a subpopulation in which 100% FRET was observed (in a gray background); these artefactual cells are discussed in Supplementary Text 5.

Based on the data from Supp. Fig. 4, most of the cells in the population transfected with tandem vector CMVγR2EYFP+EF3γR1ECFP express more IFN-γR2/EYFP than IFN-γR1/ECFP. Again, the overlap between the two populations was apparent even though statistically, the two populations were nearly distinct (p = {0.064, 0.0002}). Unsurprisingly, cells expressing more IFN-γR1/ECFP than IFN-γR2/EYFP (i.e., molar ratio less than one) exhibited poor FRET efficiency (Fig. 2A). In cells where levels of IFN-γR2/EYFP exceeded those of IFN-γR1/ECFP (i.e., molar ratio greater than one) the observed FRET efficiency increased to a EYFP:ECFP molar ratio of 2–4 and an optimal FRET efficiency of 0.9, and then decreased with increasing EYFP:ECFP molar ratios. At the optimal EYFP:ECFP molar ratio, the FRET efficiency varied only from 0.6 to 0.9.

As expected, when ECFP and EYFP were conjugated to IFN-γR2 and transfected as tandem vector CMVγR2ECFP+CMVγR2EYFP, optimal FRET was observed at a nearly equimolar ratio (1.5), where the optimal FRET efficiency of 0.5 was observed (Fig. 2B, black circles). Above and below this ratio, the FRET efficiency decreased. The coexpression of IFN-γR1 did not alter the interaction between two IFN-γR2 chains (Fig. 2B, gray circles); statistically, p = {0.34, 0.39}. This is not surprising because expression of IFN-γR2 exceeds that of IFN-γR1 in most cells (Fig. 2A) and we would not expect a protein present in sub-stoichiometric quantities to affect the observed interaction.

As we mentioned above, no cells expressing IFN-γR2/EYFP and Jak2/ECFP exhibited 100% FRET efficiency, whether IFN-γR1 was co-transfected or not, and whether IFN-γ was added to the cells or not (Fig. 2C). Similar to that seen in Fig. 2A, FRET between IFN-γR2/EYFP and Jak2/ECFP increased until a EYFP:ECFP molar ratio of 2–5 was achieved (Fig. 2C, black circles), where the optimal FRET efficiency was about 0.85; above that ratio, the FRET efficiency decreased with increasing EYFP:ECFP molar ratio. We observed that in most cells, the levels of IFN-γR2/EYFP exceeded those of the Jak2/ECFP.

Interestingly, the coexpression of IFN-γR1 greatly reduced the FRET between IFN-γR2/EYFP and Jak2/ECFP (Fig. 2C, dark gray circles), but only in a few cells. These cells possessed moderate EYFP:ECFP molar ratios. Interestingly, after IFN-γ was added to these cells, these cells were no longer seen (Fig. 2C, light gray circles). In most cells, the three population overlapped extensively, and showed no statistical distinctiveness (p = {0.64, 0.22}, {0.20, 0.18}, {0.38, 0.88} comparing the first and second, first and third, and second and third populations respectively).

For reasons we do not understand, a cohesive population exhibiting a biphasic change in FRET efficiency as a function of the EYFP:ECFP molar ratio was not observed in cells expressing IFN-γR1/ECFP and IFN-γR1/EYFP (Fig. 3D, black circles). Cells coalesced into two groups: One group had an optimal FRET efficiency of 0.8 (however, see Supplementary Text 5), while the other group possessed an optimal FRET efficiency of only 0.25. This result was striking as we biased our search for cells with blue-greenish hue for this experiment (we observed that most of the cells in this population exhibited only yellowish hue and 100% FRET efficiency). Statistical analysis was not performed as the data overlapped but did not coalesce into a single population.

Fig. 3.

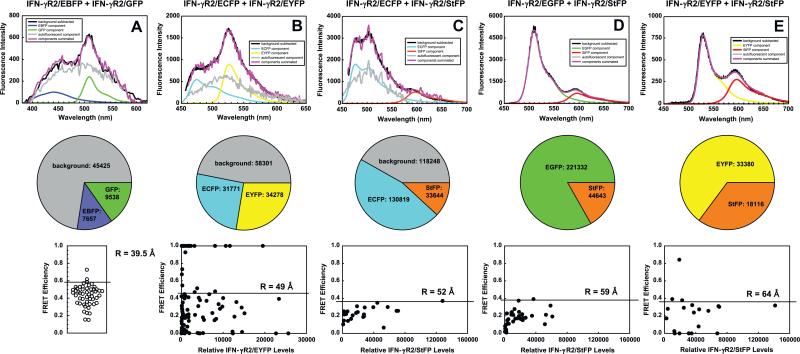

FRET between IFN-γR2 chains using red-shifted GFP variants. Cells were transfected with the following tandem vectors: (A) CMVγR2EBFP+CMVγR2GFP (B) CMVγR2ECFP+CMγR2EYFP, (C) CMVγR2ECFPm+CMVγR2StFP, (D) CMVγR2EGFPm+CMVγR2StFP, (E) CMVγR2EYFPm+CMVγR2StFP. (top) One representative spectrum was deconvolved and the result shown. Black lines are the resultant spectra after background noise was removed. Gray lines denote the component of the total spectra attributable to endogenous fluorescence. Blue, green, cyan, yellow, or orange-red lines denote the amount of total observed fluorescence due to EBFP, EGFP, ECFP, EYFP, or StFP respectively. The purple line denotes the summation of fluorescence from the two FPs and endogenous fluorescence. (middle) Pie charts show the fraction of total fluorescence from the above spectra deriving from endogenous fluorescence (background), from donor or from acceptor. The filled colors correspond to the line colors in the spectra. (bottom) The data from at least twenty deconvolved spectra are shown, as FRET efficiency vs. relative levels of acceptors. The optimal FRET level in each population is shown in each plot with a horizontal line; the inferred inter-FP distance, assuming random orientation of fluorophores, is placed above each horizontal line. Simultaneous analysis of cells expressing IFN-γR2/EBFP and IFN-γR2/GFP with two lasers could not be done due to instrumental limitations at the time [5], so only the distribution of FRET efficiencies are displayed for that pair. Note that the spectra of endogenous fluorescence is noisy because we used raw data obtained with our machine as a reference spectrum for endogenous fluorescence in these analyses. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Because both ECFP and EYFP derive from jellyfish, whose fluorescent proteins are known to dimerize (albeit with low affinity), we implemented A206K mutations into both ECFP and EYFP to reduce their potential interaction [21], hypothesizing that a more normal interaction between IFN-γR1 chains would result. Incorporation of the A206K mutation into ECFP and EYFP allowed a sub-population to appear whose EYFP:ECFP ratios were supra-optimal and with an optimal FRET efficiency of 0.7; otherwise, FRET between IFN-γR1 chains was not altered (Fig. 3D, gray circles).

Overall, our data so far demonstrate that not only sufficiently high protein levels but also a reasonable balance of donor and acceptor fluorophores are important to observe optimal interactions between fluorescent proteins in intact cells. Analysis of large numbers of cells is necessary to ensure that cells containing proteins with these properties are found.

3.2. Use of red-shifted and non-jellyfish fluorescent proteins

The presence of artefactual fluorescent interactions in some cells expressing IFN receptors and in many cells expressing IFN-γR1 prompted us to question whether artefacts are being introduced into our biological system by ECFP and EYFP themselves. Because jellyfish fluorescent proteins are known to dimerize [21], we hypothesized that investigating FRET with fluorescent proteins deriving from different biological species will minimize interactions between fluorescent proteins and consequently improve the precision and quantitation of FRET efficiencies in live cells.

Our initial studies showed that lower quantities of autofluorescence are generated with red-shifted fluorescent proteins or when using red-shifted lasers [5]. Additionally, use of red-shifted lasers to preferentially excite these proteins will not damage cells as extensively. Thus we used EGFP (or less frequently, mCitrine (CiFP), EYFP or mTeal (TFP)) as donor fluorophores and mOrange (OFP) and mStrawberry (StFP) or less frequently tdTomato (ToFP) or mCherry (ChFP) as acceptor fluorophores. Our donor of choice was GFP because (1) TFP and ECFP generate comparable levels of cellular autofluorescence, and (2) CiFP and EYFP are poorly excited (while EGFP remains well excited) with the 442 nm laser, our preferred donor laser due to its poor direct excitation of acceptors. Our acceptor of choice is StFP because (1) OFP matures sufficiently slowly in cells (t1/2 = 2.5 h [13]) such that a green fluorescent peak (λmax = 510 nm) can be seen when exciting living cells with 442 or 457 nm lasers (Supp. Fig. 5), (2) ChFP has a lower quantum efficiency (φ = 0.22) and less efficient spectral overlap with the EGFP, EYFP, and CiFP than does StFP (φ = 0.29), (3) ToFP is a dimer, complicating data analysis, and (4) StFP has similar maturation kinetics to EGFPm, EYFPm, and CiFPm, and matures faster than ECFP, TFP and OFP.

3.2.1. Systematically decreased FRET with decreased cellular autofluorescence

We compared the FRET between two IFN-γR2 chains tagged with various red-shifted donor:acceptor pairs to investigate whether use of various red-shifted donor:acceptor pairs has any advantages over the use of EBFP:GFP or ECFP:EYFP pairs. We noticed that, as the donor:acceptor pair becomes progressively red-shifted, the amount of non-FP fluorescence seen in the deconvolved spectra diminishes (Fig. 4, top and middle). The amount of cellular autofluorescence was highest with EBFP as a donor (Fig. 4A). Autofluorescence was somewhat lower when ECFP was the donor, whether EYFP (Fig. 4B) or StFP (Fig. 4C) was the acceptor. Cellular autofluorescence was only occasionally seen when EGFP was a donor (Fig. 4D), and was negligible when EYFP was the donor (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

FRET between various protein pairs tagged with donor:acceptor pairs that derive from different species. The following tandem vectors or pairs of plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and the spectra of fluorescent cells analyzed: (A) CMVγR2EGFPm+CMVγR2StFP (black circles), CMVγR2StFP+CMVγR2EGFPm (dark gray circles), or pc3-IFN-γR2/EGFPm and pc3-IFN-γR2/StFP (light gray circles), (B) pc3-IFN-γR1/CiFPm and pc3-IFN-γR2/StFP (unfilled and gray filled black circles), CMVγR2StFP+EF3γR1EGFPm (filled black circles), pc3-IFN-γR2/CiFPm and pEF3-IFN-γR1/TFP (unfilled gray circles), or pc3-IFN-γR2/OFP and pEF3-IFN-γR1/EGFPm (filled gray circles) (C) pEF3-IFN-γR1/EGFPm and pEF3-IFN-γR1/OFP (gray circles) or pEF3-IFN-γR1/EGFPm and pEF3-IFN-γR1/StFP (black circles), and (D) pc3-IL-10R2/OFP and pEF3-Tyk2/EGFPm (filled gray circles), pc3-IFN-γR2/StFP and pCMVi.5-Jak2/CiFPm (unfilled black circles), or pEF3-IFN-γR1/EGFPm and pc3-Jak1/StFPm (filled black circles). The ratio of acceptor-tagged protein to donor-tagged protein and the observed FRET efficiency were calculated and plotted for each pair. In (A) and (C) the error bars are colored to resemble the corresponding dataset. In (B) the black and gray filled error bars correspond to cells expressing pc3-IFN-γR1/CiFPm and pc3-IFN-γR2/StFP before (unfilled circles) and after (gray filled circles) IFN-γ treatment; the unfilled error bars are colored to match the colors of the other three datasets. In (D), the error bars are colored and filled to correspond to each dataset.

Coincident with a decrease in autofluorescence was a paradoxical decrease in FRET efficiency. R0 generally increased with increasing red-shiftedness of each pair, from 42.1 to 49.2 to 48.1 to 54.9 to 57.1 Å (Table 1). Mathematically, one would predict that the optimal FRET efficiency increases with increasing R0 if the inter-FP distance is fixed; this is demonstrated visually with a graph of FRET efficiency vs. inter-FP distance of several curves each possessing different R0 values (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, the optimal FRET efficiency decreased as the pair became more red-shifted. We observed (Fig. 3 bottom, from left to right) 60% optimal FRET efficiency with the EBFP:EGFP pair, 45–50% FRET efficiency with ECFP:EYFP (ignoring cells exhibiting unusually strong FRET), and 35–40% with ECFP:StFP, with EGFP:StFP and with EYFP:StFP. This paradox is also illustrated if one calculates inter-FP distances from the optimal FRET efficiencies. We calculated inter-FP distances of 39.5 Å for the EBFP:GFP pair, 49 Å for the ECFP:EYFP pair, 52 Å for the ECFP:StFP pair, 59 Å for the EGFP:StFP pair, and 64 Å for the EYFP:StFP pair. Assuming that spectra in which endogenous fluorescence is minimal are more representative of the biological spectroscopic interaction, we would predict that the distances obtained under conditions where endogenous fluorescence are not present are more reliable.

Table 1.

R0 values between various fluorescent proteins. These values were calculated as described in Section 2. The donor fluorophores are on the vertical axis, while the acceptor fluorophores are given on the horizontal axis. All values are given in Angstroms (Å). R0 values under 50 Å are set in red; those over 60 Å are set in blue. R0 values in a dark gray background were from pairs used extensively in this report; those in a light gray background were from pairs used only occasionally in this report.

| donors | acceptors | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mWasabi | EGFP | Clover | mNeGr | EYFP | CiFP | OFP | ToFP | TagRFP | StFP | mRuby2 | ChFP | Kate2 | |

| EBFP | 40.5 | 42.1 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 38.1 | 37.3 | 36.1 | 38 | 34.1 | 36 | 38.2 | 33.3 | 32.3 |

| ECFP | 46 | 45.8 | 50.8 | 51.5 | 49.2 | 47.4 | 46.9 | 48.1 | 46.1 | 48.1 | 49.5 | 44.9 | 43.1 |

| TFP | 53.7 | 52.8 | 59.4 | 60.3 | 55.6 | 54.8 | 53.9 | 55 | 52 | 54.2 | 56 | 50 | 47.6 |

| mWasabi | 59.1 | 56.2 | 55.5 | 56.1 | 56.9 | 55.2 | 57.1 | 58.8 | 53.1 | 50.6 | |||

| SaFP | 54.1 | 53.5 | 54 | 54.8 | 53.5 | 55.1 | 56.8 | 51.7 | 48.8 | ||||

| EGFP | 53.6 | 53 | 53.7 | 54.5 | 53.2 | 54.9 | 56.5 | 51.1 | 48.6 | ||||

| Clover | 55.1 | 54.9 | 56.9 | 58.1 | 57.5 | 59.2 | 60.9 | 55.3 | 52.8 | ||||

| mNeGr | 56.6 | 56.3 | 57.6 | 58.6 | 57.6 | 59.3 | 61 | 55.1 | 52.3 | ||||

| AmFP | 50.1 | 54.8 | 56.1 | 56.3 | 58.2 | 59.4 | 54.6 | 52.2 | |||||

| EYFP | 49.8 | 55.6 | 56.7 | 57 | 59.2 | 60.1 | 55.7 | 52.9 | |||||

| CiFP | 56.7 | 58.9 | 58.5 | 61.4 | 62.7 | 56.8 | 55.3 | ||||||

| OFP | 55.4 | 58.4 | 61.8 | 62 | 60.2 | 58.8 | |||||||

| TagRFP | 53.7 | 51.4 | 54.2 | 53.7 | |||||||||

| StFP | 49.6 | 49.6 | |||||||||||

| mRuby2 | 51.3 | 51.3 | |||||||||||

| ChFP | 44.2 | ||||||||||||

Supplementary Text 7 contains the scientific background and an experiment designed to test whether the excessively high FRET efficiency with blue-shifted donor:acceptor pairs is caused by quenching of blue-shifted fluorescence and the concomitant generation of endogenous fluorescence.

3.2.2. Reduced artefactual interactions by using donor and acceptor proteins from different species

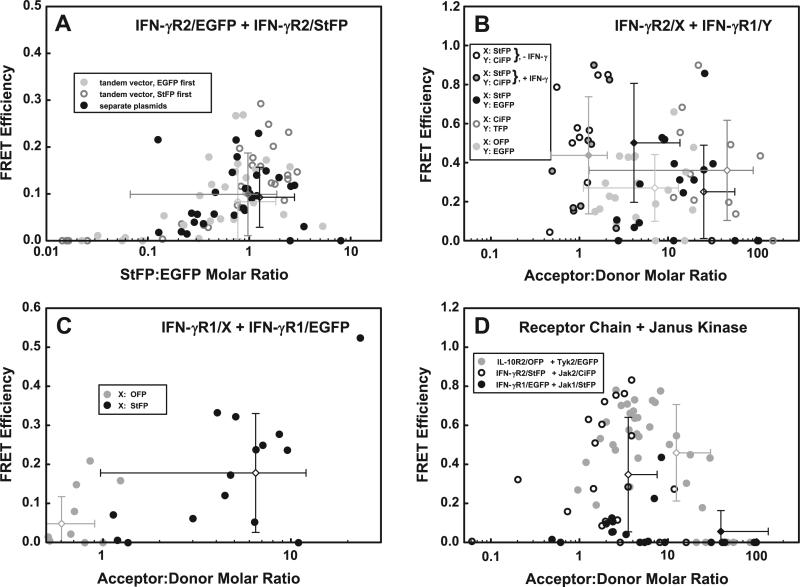

With these new donor:acceptor pairs that do not both derive from jellyfish, we observed far fewer cells in which only acceptor fluorescence was seen when excited with the donor laser. To illustrate this, we measured FRET efficiencies in four different pairs of proteins (IFN-γR2:IFN-γR2, IFN-γR1:IFN-γR2, IFN-γR1:IFN-γR1 and receptor:Janus kinase) as a function of the donor:acceptor molar ratio.

First, we analyzed FRET between the IFN-γR2/EGFP and IFN-γR2/StFP pair in thirty cells from three distinct transfections using DDAB:DOPE liposomes (ninety cells total). The transfections were done with tandem vector CMVγR2EGFP+CMVγR2StFP (Fig. 4A, black circles), with tandem vector CMVγR2StFP+CMVγR2EGFP (where the order of the two transcriptional units is reversed, Fig. 4A, dark gray circles), or with an equimolar mixture of the single-cDNA plasmids pc3-FL-IFN-γR2/EGFP and pc3-FL-IFN-γR2/StFP (Fig. 4A, light gray circles). When we resolved the obtained FRET efficiencies as a function of the StFP:EGFP molar ratio in each population, we found that the three datasets overlapped extensively (p = {0.43, 0.45}, {0.15, 0.59}, and {0.37, 0.74} for the first and second, first and third, and second and third populations, respectively), inferring that the expression of a cDNA does not strongly vary whether first in a tandem vector, second in a tandem vector, or expressed in isolation. The average acceptor:donor ratio was slightly higher when the acceptor protein was “upstream” in a tandem vector than when the acceptor protein was “downstream” (implying a slight preference for expression of the upstream gene in a tandem vector). We attribute an apparent majority of cells with excess donor in all three populations in our data to subjective bias by searching for green cells. The optimal FRET efficiency observed was 0.28–0.30, corresponding to an inter-FP distance of 63–64 Å, seen when the StFP:EGFP ratio was nearly equimolar (0.8–1.2). As expected, the FRET efficiency decreases with increasing imbalance of acceptor or donor levels.

Second, we measured FRET between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 with various donor:acceptor pairs using separate plasmids expressing IFN-γR2/StFP and IFN-γR1/CiFP (Fig. 4B, black unfilled and gray-filled circles), tandem vector CMVγR2StFP+EF3γR1EGFP (Fig. 4B, black filled circles), separate plasmids expressing IFN-γR2/CiFP and IFN-γR1/TFP (Fig. 4B, gray unfilled circles), and tandem vector CMVγR2OFP+EF3γR1EGFP (Fig. 4B, gray filled circles). Irrespective of which donor:acceptor pair was used, use of FPs from distinct species removed cells exhibiting 100% FRET, demonstrating that the use of the ECFP:EYFP pair produces artefactual interactions in some circumstances.

Cells expressing IFN-γR1/CiFP and IFN-γR2/StFP, both in the absence of IFN-γ (unfilled black circles) and in the presence of 1700 U/mL IFN-γ for at least 10 min (gray-filled circles), exhibited an optimal FRET efficiency of 0.90 at a nearly equimolar ratio. This dataset was statistically as well as spatially distinct from the second, third and fourth populations (p = {0.007, 0.011}, {0.003, 0.26}, and {0.036, 0.014}, respectively). We attained equimolarity by intentionally transfecting half the normal amount of pc3-IFN-γR2/StFP plasmid with a normal amount of pEF3-IFN-γR1/CiFP plasmid. Addition of IFN-γ did not change the visual or statistical distribution of the data (p = {0.36, 0.63}).

When IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR2/StFP were coexpressed, the FRET efficiency peaks at about 0.85 at an acceptor:donor molar ratio of about 25. Similarly, the FRET efficiency peaks at 0.90 at an acceptor:donor molar ratio of 20 when IFN-γR1/TFP and IFN-γR2/CiFP were coexpressed. Although these two datasets overlapped with each other (p = {0.15, 0.17}), they were spatially and statistically distinct from the fourth statistically (p = {0.03, 0.62} and {0.006, 0.26} respectively). When we coexpressed IFN-γR2/OFP and IFN-γR1/EGFP, the optimal FRET of 0.65 was observed at an acceptor:donor molar ratio of 10.

Third, we investigated FRET between IFN-γR1 chains by cotransfecting individual plasmids and measuring FRET between IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR1/StFP (Fig. 4C, black circles) or between IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR1/OFP (Fig. 4C, gray circles). Although we found no cells with a large FRET efficiency, neither population gave a spatially cohesive data set with a conclusive optimal FRET efficiency; the two populations were spatially and statistically distinct (p = {0.001, 0.007}). Ignoring one cell with a questionably high FRET efficiency, the remaining cells expressing IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR1/StFP exhibited an optimal FRET efficiency of 0.30–0.35 at an acceptor:donor molar ratio of about 4. This FRET efficiency corresponds to an inter-FP distance of 61–63 Å.

Fourth, we analyzed FRET between a receptor chain and a tyrosine kinase by cotransfecting the separate plasmid pairs IL-10R2/OFP and Tyk2/EGFP (Fig. 4D, gray circles), IFN-γR2/StFP and Jak2/CiFP (Fig. 4D, unfilled black circles), and IFN-γR1/EGFP and Jak1/StFP (Fig. 4D, black filled circles). In most cells, the levels of IL-10R2 exceeded that of Tyk2 and (similar to that seen in Fig. 2C) the levels of IFN-γR2 exceeded that of Jak2; the optimal FRET efficiency within each population is 0.85 at an optimal acceptor:donor molar ratio of 2–4; this results in an inter-FP distance of 40 and 46 Å respectively. Though the two populations overlap, they are statistically distinct (p = {0.007, 0.15}).

Interestingly, the levels of Jak1 generally exceeded those of IFN-γR1, and in most cells, FRET between the two was poor or absent. In cells where FRET was present, the optimal observed FRET efficiency of 0.42 implies an inter-FP distance of 62 Å. We attempt to understand why FRET was observed only in some cells elsewhere [22]. This population was statistically significant from the other two populations, (p = {0.22, 4× 10–11}, and {0.11, 0.0003} between it and the IL10R2:Tyk2 and IFN-γR2:Jak2 populations, respectively).

3.3. Incomplete interaction between proteins in cells

Even after resolving FRET efficiencies as a function of acceptor:donor molar ratios, there is still considerable variation in FRET at a given molar ratio. Because FRET between two proteins tends to increase as the levels of each protein increase (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that the interaction between proteins tagged to acceptor or donor is reversible. Thus, we evaluated the existence of an incomplete binding between acceptor-tagged protein and donor-tagged protein.

We evaluated two methodologies to analyze the efficiency of protein binding in intact cells. To illustrate the validity of these approaches, a large pool of data must be analyzed; we restricted our analysis to the interaction between IFN-γR2/StFP and IFN-γR2/EGFP in this report as this is the only pair we analyzed in which we have a sufficient number of cells analyzed to permit reliable conclusions.

3.3.1. Fractional incorporation of donors or acceptors into complexes

First, we measured the fraction of donor in donor:acceptor complexes as a function of donor levels (Fig. 5A, gray circles), overlaying this data with the fraction of acceptor in donor:acceptor complexes as a function of acceptor levels (Fig. 5A, black circles) because both datasets overlapped; curiously, the two populations were almost but not fully distinct statistically (p = {0.11, 0.059}). Measuring these fractions requires knowing the optimum FRET efficiency possible with this pair (that we estimated to be 0.30, Fig. 4A). In these studies, we assume that each IFN-γR2:IFN-γR2 complex formed exhibits FRET identical to the optimal observed FRET efficiency, and that any excess donor fluorescence that lowers observed FRET efficiency derived from uncoupled donors.

Fig. 5.

Reversibility and incomplete interactions between IFN-γR2/EGFPm and IFN-γR2/StFP. Pooled data from Fig. 4A was used. (A) The fraction of incorporation of either IFN-γR2/EGFPm (gray circles) or IFN-γR2/StFP (black circles) into IFN-γR2/EGFPm:IFN-γR2/StFP complexes was plotted as a function of relative levels of the respective chain. Error bars are color coded to match the respective datasets. (B) FRET efficiency was plotted as a function of the relative numbers of complexes of IFN-γR2/EGFP:IFN-γR2/StFP formed in each cell. The mean and standard deviation are shown for each dimension in this population. (C) The levels of IFN-γR2/EGFPm and IFN-γR2/StFP in each cell were plotted pairwise, and a bubble plot was overlaid where the diameter of the bubble (black-bordered circles) is proportional to the magnitude of Qeq. The black diagonal line denotes the locations on the graph where cells possessing equal levels of IFN-γR2/EGFP to IFN-γR2/StFP chains would lie. The mean and standard deviation are shown for the donor and acceptor in this population. (D) The Qeq for each cell was plotted as a function of the obtained FRET efficiency between two IFN-γR2 chains. Cells were transfected with IFN-γR2 tagged to either ECFP and EYFP (filled light gray circles), EGFP and StFP (filled black circles), TFP and CiFPm (unfilled black circles), TFP and StFP (unfilled light gray circles), or TFP and ChFP (unfilled dark gray circles). The error bars are color coded and filled to match its corresponding dataset.

We observed that, below 20,000–40,000 relative IFN-γR2 chains per cell, the fraction of incorporation of IFN-γR2 chains into complexes increases with increasing numbers of IFN-γR2 chains (Fig. 5A). This demonstrates that the interaction between IFN-γR2 chains is reversible. We also observed that complex formation is not efficient in most cells in the population.

3.3.2. Complexes formed per cell and how efficiently complexes form

Evidence supporting reversible and inefficient complex formation is also observed when we plotted the observed FRET efficiency as a function of the numbers of IFN-γR2:IFN-γR2 pairs formed in each cell (Fig. 5B). In this relation, we found that the optimal observed FRET efficiency increased hyperbolically with increasing numbers of complexes formed per cell. No more than 50,000 complexes per cell were observed; this limit resembled the upper range of the peaks in Fig. 5A. In both graphs, half-optimal FRET efficiency and a 50% coupling of acceptors or donor occurred at about 5000 relative IFN-γR2 chains per cell. We interpret this number as an apparent affinity constant for the IFN-γR2:IFN-γR2 interaction. In this graph we observe that there is a minimum FRET efficiency imposed on the system when a given number of complexes form per cell. Both figures demonstrate that only some cells show an effective coupling of donor and acceptor proteins. Supporting this, the two-dimensional mean of this population of data (12,500 pairs, 15.5% FRET efficiency) underestimates both the number of donor:acceptor pairs formed and the optimal FRET efficiency observed. Thus, in most cells only some of the donor-fused and acceptor-fused proteins are interacting.

3.3.3. Equilibrium or disequilibrium of protein interactions in cells

We investigated the poor overall binding of donor and acceptor throughout the cell by calculating the equilibrium reaction quotient (Qeq) that quantifies the effectiveness of the coupling of acceptor-tagged protein to donor-tagged protein. This quotient is defined as the amount of complexes divided by the amounts of uncomplexed proteins. We plotted the Qeq as a function of donor and acceptor levels in a bubble plot (Fig. 5C), where the size of the bubble is proportional to increasing magnitude of Qeq (i.e., more efficient coupling of donor and acceptor). In many cells where the most progressive interactions occurred (Fig. 5C, black unfilled circles) the levels of donor and acceptor were comparable. The average levels of donor and acceptor in this population are shown (30,000 ± 32,000 relative molecules IFN-γR2/StFP, 38,000 ± 34,000 relative molecules IFN-γR2/EGFP).

Finally, when we plotted the Qeq as a function of the observed FRET efficiency, we found that higher Qeq values were seen in cells with higher observed FRET between the receptor chains within a transfected population (Fig. 5D, black filled circles). This result agrees with our observations that the highest FRET is seen between IFN-γR2 chains when the highest Qeq is seen: when donor and acceptor levels are balanced, and when most of the donors and acceptors in the cell are coupled. Although Qeq was not high in most cells in the population, a high Qeq was obtained in a few cells in the population – in these cells a high FRET efficiency was seen and over 90% of both donor and acceptor are coupled. This suggests that, if a sufficiently large population of cells is analyzed, a Qeq value can be obtained that may approximate the Keq. Nevertheless, the interaction between donor- and acceptor-tagged proteins has not achieved equilibrium in most cells; this phenomenon occurs with most protein pairs we analyzed in cells (data not shown) and is probably a consequence at least partially of dynamic in vivo expression and/or turnover of fluorescent protein pairs in intact living cells.

To support that Keq can be achieved in cells, we found that cellular equilibrium may be achieved in a significant fraction of cells in limited cases. While Qeq increases throughout the entire range of observed FRET efficiencies in cells expressing IL-10R2/OFP and Tyk2/EGFP (Supp. Fig. 8, gray circles), Qeq instead forms a plateau with increasing FRET efficiencies in the population expressing IFN-γR2/StFP and Jak2/CiFP (Supp. Fig. 8, black circles). The fact the Qeq cannot surpass a given value of 1 × 10–1 in many cells in a population with high FRET efficiency implies that the optimal Qeq may in fact equal Keq, implying that in those cells, equilibrium was achieved.

We rationalized that the artificial coupling of jellyfish fluorescent proteins may manifest with artificially high Qeq's. To illustrate this, we plotted Qeq as a function of FRET efficiency between two IFN-γR2 chains coupled to various donor:acceptor pairs. With both donor and acceptor from jellyfish (ECFP and EYFP, Fig. 5D, gray filled circles), the optimal Qeq obtained was highest: 3 × 10–1. When only one protein comes from jellyfish, the optimal Qeq was lower: 7 × 10–3 with EGFP[A206K] and StFP (filled black circles) and 4 × 10–3 with TFP and CiFP[A206K] (unfilled black circles). When neither protein is from jellyfish, the Qeq was lowest: 9 × 10–4 with TFP and StFP (unfilled light gray circles) and 3 × 10–4 with TFP and ChFP (unfilled dark gray circles). The average Qeq of each population corresponded with the optimal Qeq observed. Statistically significant decreases in average Qeq were observed when progressing from ECFP:EYFP to other pairs (p = 0.038 with EGFP:StFP or to TFP:CiFP or 0.037 to TFP:StFP or to TFP:ChFP), but not between the other pairs, supporting our conclusion that removal of one fluorescent protein will remove most but not all nonspecific interactions. We conclude that caution must be exercised when using jellyfish donors or acceptors to ensure artefactual donor:acceptor interactions are not occurring.

3.3.4. Distinguishing specific from nonspecific interactions in cells

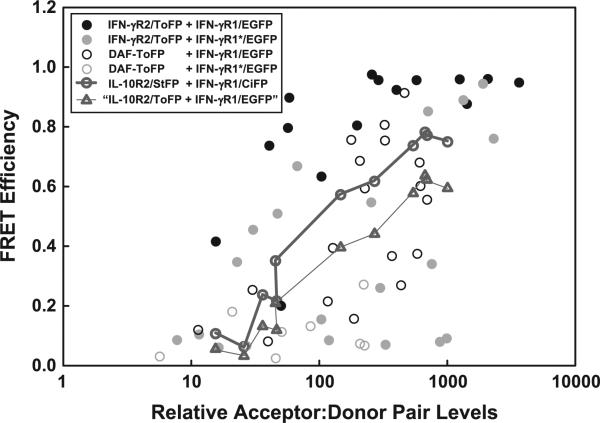

We can judge the affinities of proteins pairs by comparing their ability to form large numbers of complexes at a given level of proteins. The interaction between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 has an unusually high FRET efficiency, and both proteins are confined to the plasma membrane, effectively occupying a very small cellular volume. We questioned whether some of the observed FRET arose from concentration of receptor chains within confined spaces that would increase the frequency of random collisions and juxtapositions. It is important to determine how much of the FRET between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 is due to a longer-lived biophysical interaction and how much is due to nonspecific interactions like the random collisions mentioned above.

To estimate nonspecific interactions between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2, we compared the apparent affinity between IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR2/ToFP to the apparent affinity between IFN-γR1 and proteins to which it should not interact in live cells, such as IL-10R2/StFP [5,7] and a glycosylphosphatidylinisitol-anchored ToFP that has no other protein component (called DAF-ToFP). We hypothesized that if there is a specific interaction between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2, that its affinity will be stronger than that between IFN-γR1 and IL-10R2 or between IFN-γR1 and DAF-ToFP. Because the data are quite diverse along both axes, arithmetic mean-based statistical analyses were not performed.

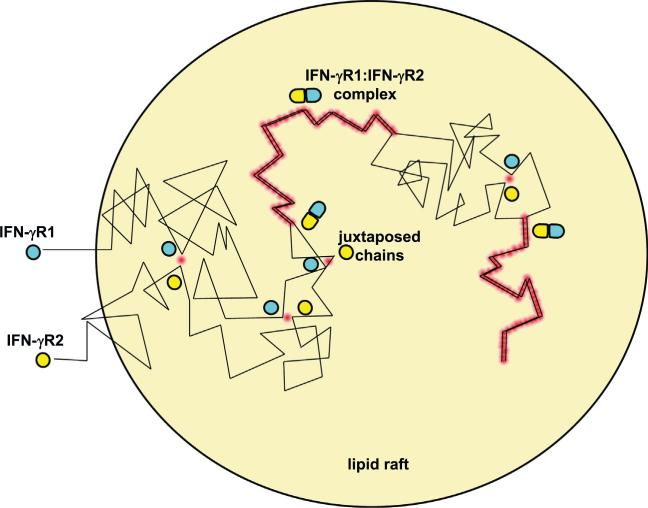

We found that the affinity between IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR2/ToFP (Fig. 6, filled black circles) was about threefold higher than that between IFN-γR1/CiFP and IL-10R2/CiFP (thick unfilled dark gray circles connected by dark gray lines) and about sevenfold higher than that between IFN-γR1/EGFP and DAF-ToFP (thin unfilled black circles). If we convert the FRET efficiencies between IFN-γR1 and IL-10R2 from CiFP:StFP to EGFP:ToFP (assuming the distance between fluorophores is independent of which fluorophore is used) to make the donors and acceptors uniform throughout the experiment, the difference between the two sets of data increased to about sevenfold (Fig. 7, thick unfilled dark gray triangles connected by thin gray lines). Because FRET between IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR2/ToFP are seen at levels when FRET between IFN-γR1/EGFP and IL-10R2/CiFP are poorer (i.e., less than 100 donor:acceptor pairs), we conclude that at least some of the FRET between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 arises from a direct biochemical interaction, while the remainder of FRET between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 is mediated by their nano-colocalization within subsections of the biological membrane. To estimate a true FRET efficiency in which nonspecific interactions are removed, we can subtract the FRET between “nonspecific” interactions from the FRET between the “specific and nonspecific” at similar levels of donor:acceptor pairs. The maximum difference between the two is about 0.6; this efficiency corresponds to an upper-limit for the inter-FP distance between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 of 51 Å.

Fig. 6.

Affinities of membrane localization or receptor interaction. FRET efficiency between the following pairs of fluorescent proteins excited at 488 nm was determined as a function of the numbers of donor:acceptor pairs measured: IFN-γR1/EGFP and IFN-γR2/ToFP (filled black circles), IFN-γR1[P284L]/EGFP and IFN-γR2/ToFP (filled gray circles), IFN-γR1/EGFP and DAF-ToFP (unfilled black circles), IFN-γR1[P284L]/EGFP and DAF-ToFP (unfilled gray circles), and IFN-γR1/CiFP and IL-10R2/StFP (unfilled thick dark gray circles, connected with the thick gray line segments). The data from filled circles come from a matched receptor pair, while the data from unfilled circles come from proteins that should not interact and therefore at most colocalize or nonspecifically interact. The data between IFN-γR1/CiFP and IL-10R2/StFP were translated to that predicted between EGFP and ToFP (unfilled thick dark gray triangles, connected with the thin gray line segments) to make all datasets more comparable.

Fig. 7.

FRET from colocalization and from direct biochemical interaction. A pair of proteins (shown here are IFN-γR1, in blue–green and IFN-γR2, in yellow) that are confined to a smaller areas will randomly collide with each other more frequently (black crooked lines denote their random migration). Each juxtaposition will result in a FRET event (red spot). Occasionally, the collided pair has the proper relative orientation, and interacts biochemically to form the receptor complex (blue–green and yellow flattened ellipses). The pair migrate together and persistently undergo FRET until the pair dissociates. Because the association is reversible, each receptor chain can associate with other receptor chains and form new complexes. However, to simplify the figure, the same two proteins are shown to re-associate. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We also queried the affinity of the interaction between IFN-γR2/ToFP or DAF-ToFP and the mutant IFN-γR1[P284L]/EGFP, that interacts poorly with IFN-γR2 [6] and may localize in the membrane in an unusual fashion relative to wild-type IFN-γR1 [23]. The results we obtained with IFN-γR1[P284L]/EGFP were interesting, but are relegated to Supplementary Text 8.

4. Discussion

4.1. Justifying and managing the analysis of variations in FRET

The most common approach to demonstrate FRET efficiency between two proteins is to show a few representative cells or report an average of multiple measurements. However, we found that many factors can alter the apparent FRET efficiency of protein pairs expressed within cells in a transfected population. Some variables (such as sufficiently high levels of donor or of acceptors) can be controlled by choosing the correct cells. The expression of individual proteins can also be tuned by altering promoters or 3′ untranslated regions controlling the expression of a given cDNA, or by changing the total amount of plasmid being transfected. Other variables (such as the proper acceptor:donor molar ratio) can be accounted by examining enough cells that optimal conditions can be identified within the resulting dataset. Others still (such as optimal transfection efficiencies or reagents) are mastered by empirical optimization prior to data collection. Some cannot be controlled and must be taken into account, such as variations in laser power. Other variables cannot be resolved without dramatic changes to the experimental system, such as stability of fluorescent fusion proteins, folding or maturation efficiency of various fluorescent proteins, or the speed of protein interactions in cells. In this report we discovered and analyzed several factors that change the apparent FRET between a given pair of proteins.

We implemented a rigorous protocol to separate and quantify endogenous fluorescence, donor fluorescence, and the two sources of acceptor fluorescence (Supp. Text 4). Separation of donor, acceptor, and endogenous fluorescence is done by spectral deconvolution. Excitation of samples containing only the acceptor with both the donor and acceptor lasers gave a determination of the amount of acceptor fluorescence that arose directly from laser excitation. Subtracting this quantity from total observed acceptor fluorescence when donor is present gives the amount of fluorescence involved in FRET from the donor (Supp. Fig. 2). These subdivisions correlate with potential light pathways through the donor:acceptor system (Supp. Fig. 3A). If we assume a kinetic scenario of photon transfer through these pathways, we can create equations that correlate observed fluorescent quantities with combinations of the kinetic constants that quantitatively characterize these pathways (Supp. Fig. 3B). Because the FRET efficiency and the quantum yield of fluorescence also are characterized in terms of kinetic constants, we used algebraic methods to define FRET efficiency in terms of observed fluorescent quantities and known fluorescence constants (Supp. Fig. 3C and D). Coupled with equations to calculate relative numbers of donors, acceptors, and acceptor:donor complexes, we have improved the quantitative analysis of fluorescence emission data.

4.2. Variables lowering the optimal FRET observed between two proteins

We observed that emission spectra vary considerably throughout the cells in a population. In correlation, the levels of donor and acceptor varied throughout a transfected population. We have assumed that the FRET between any given pair of molecules does not change in various environments, and instead state that lower apparent FRET efficiencies arises from excess donor fluorescence from uncoupled donors. We observed that lower amounts of donors or acceptors in cells caused the observed FRET to be quite poor (Fig. 1), most likely by preventing the formation of large numbers of complexes (Fig. 5A and B). Because cells generally cannot produce large numbers of proteins, excessive expression of one protein often leads to poor production of the other protein. This can explain why the observed FRET efficiency will be suboptimal at extreme acceptor:donor ratios (Figs. 2 and 4). Additionally, excess uncoupled donor will produce excess donor fluorescence; this will additionally lower the observed FRET efficiency. We have observed that relatively few cells in the population will exhibit optimal FRET between donor and acceptor; these cells are identified by an analysis of sufficiently large numbers of cells.

4.3. Errors in obtaining accurate FRET efficiencies

In these studies we noticed several factors that will introduce systematic errors in the estimation of FRET efficiency. The largest source involves the proper choice of fluorescent proteins. Supplementary Text 9 gives a background on the various newer-generation FPs that can be used and why some newer-generation FPs should replace older FPs; in the main text we focus on more relevant aspects of the various next-generation fluorescent proteins that surfaced during our studies.

Most importantly, use of donors or acceptors that generate large amounts of endogenous fluorescence yielded overestimated FRET efficiencies (Fig. 3). This is probably caused by quenching of blue-shifted fluorescence by endogenous fluorophores in cells (Supp. Fig. 7).

Use of fluorescent proteins that fold or mature slowly also introduced systematic errors in obtained data. We have noticed that use of OFP as an acceptor often gave not only lower-than-excepted FRET efficiencies but also lower acceptor:donor ratios and often lower apparent affinities for complex formation (Fig. 4B and C, unpublished observations). We attribute this to a slower maturation rate of OFP compared to most other fluorescent proteins, resulting in lower-than-expected levels of OFP. This slow maturation in cells is revealed by the presence of a weakly green fluorescent intermediate when exciting cells with 442 or 457 nm lasers (Supp. Fig. 4, right panels). Similar blue-shifted fluorescent intermediates are seen in the maturation of far-red fluorescent proteins based on mKate [24]. One can deduce that cellular proteins tagged to fluorescent proteins that mature slowly will have subpopulations that are fluorescent and significant populations that are not yet fluorescent. The latter will compete with the former in interacting with other fluorescently labeled cellular proteins and function as cellular antagonists of FRET.

Reliance upon arithmetic averages of populations, or assuming an entire population can be described as a distribution of randomly error-prone values along either side of an “average” interaction, assumes that the same (and presumably optimal) interaction is occurring among all cells in a population. However, we outline in this manuscript several variables that conspire to inhibit the optimal observed FRET efficiency, so that few cells in the population contain acceptors and donors that are optimally interacting. This was true not only for interactions that do not survive immunoprecipitation (between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2) but also for interactions that persist after immunoprecipitation (such as receptors to Janus kinases). Thus, the calculated average FRET for a number of cells will almost always underestimate the true FRET efficiency (Fig. 5B). Though this is caused by an over-representation of cells with suboptimally interacting donors and acceptors, the extent of this underestimation can be mitigated by probing high-affinity interactions.

Also, use of jellyfish fluorescent proteins, because of their ability to interact with each other albeit weakly [21] (Fig. 5D), will produce FRET efficiencies that may be artificially high, due to interactions not only between the cognate proteins but also between the donors and acceptors themselves. In fact, we found that these proteins artificially catalyzed what is normally a very weak and poor interaction between IFN-αR1 and IFN-αR2c [25]. Much of this error in FRET overestimation will be reduced if only one fluorescent protein is from jellyfish.

Finally the confined localization of proteins within cells (expected with luminal proteins, membrane-associated proteins, and transmembrane proteins) will increase the amount of nonspecific interactions between donors and acceptors in cells. Interactions whether they be transient and nonspecific or long-lasting and specific will contribute to FRET (Fig. 7). Nonspecific interactions will artificially increase the observed FRET efficiency, but this can be indirectly corrected.

4.4. Discriminating specific from nonspecific interactions

Discovering that relative affinities of interactions can be determined using our protocol, we can determine apparent affinities of “specific” interactions (that are a combination of truly specific interactions and nonspecific interactions) and nonspecific interactions. The latter is most effectively done by substituting one of the cognate proteins for a paralog (whose folding is similar but binding is known not to occur) so that the folding, maturation, and overall expression of the fusion protein is most similar, and if there are unusual localizations, that the localization is also faithfully conserved. Alternatively, use of a cognate protein with no known homology but with similar localization may also suffice. In our studies we utilized both a paralog of IFN-γR2 (IL-10R2) and ToFP with only a glycosylphosphatidylinositol linkage as a localization control. Affinities between either IL-10R2 or DAF-ToFP and IFN-γR1 were significantly less than the affinity between IFN-γR2 and IFN-γR1 (Fig. 6).

As done with binding curves, subtraction of nonspecific binding from total observed binding approximates specific binding. Subtraction of two hyperbolic plots (arithmetic plot) or sigmoidal plots (logarithmic plot) gives a gumdrop-shaped curve whose maximum gives an estimation of the true FRET efficiency. However, if nonspecific interactions strongly contribute to overall interactions, then the lower limit after removing nonspecific interactions may significantly underestimate the true FRET efficiency.

4.5. Detecting reversible protein interactions in cells

Many protein interactions in cells are reversible on a second-to-minute timescale. Prior to embarking on this work, we believed that the interaction between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 was reversible because, while their interaction is observed spectroscopically in intact cells, their preassociation is not observed by coimmunoprecipitation when detergents that completely disrupt membranes are used [17,19]. In this manuscript, we discovered that IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2 do not progressively form complexes, especially at lower levels of either receptor chain (Fig. 1) or when lower levels of IFN-γR1:IFN-γR2 complexes form (Fig. 6). The interaction between two IFN-γR2 chains is also reversible (Fig. 5).

We confirmed the reversibility of reactions by three empirical: (1) the fraction of occupation increases as the protein levels increase, (2) the overall FRET efficiency increases with increasing numbers of acceptor:donor complexes, and (3) Qeq increases with increasing FRET efficiency between the donors and acceptors in the cell (Fig. 5A, B, and D).

An analysis of different pairs of donor- and acceptor-tagged proteins reveals that differences can be seen among different pairs of proteins (Table 2). This result in itself is not novel, except that few technologies exist to compare the affinity of protein interactions in intact cells; in this report we present multiple methods to discern these interactions and their relative affinities.

Table 2.

FRET-derived statistics for various protein pairs within the IFN-γ receptor complex. The overall results of the analysis of FRET among at least 10 cells excited by the 442 nm laser in a transfected population are shown. The first two columns are the donor and acceptor proteins. The third column contains any extra co-transfected proteins. The fourth column lists the cell lines used for the experiment; the term ‘(488)’ indicates that 488 nm excitation was used. The fifth column indicates the optimal FRET efficiency; the sixth column contains the calculated distance between randomly-oriented fluorophores. The seventh column lists the maximum Qeq, with 10–4 factored out; the eighth column indicates the relative numbers of donor:acceptor pairs formed when half-optimal FRET are seen (EC50). Interactions are subdivided by category. From top to bottom are interactions (from top to bottom) between IFN-γR2 chains, between IFN-γR1 chains, between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2, between either Jak1 and IFN-γR1 or Jak2 and IFN-γR2, and between a receptor chain and a lipidated ToFP (ToFP linked to the acylation motif of either human c-lyn or human GAP). A range of EC50 values indicates that the obtained data fell evenly through that range; a comma-delimited list of EC50 values indicates that the obtained data clustered between two groups whose individual EC50 values could be determined. An EC50 value denoted as an upper limit denotes that insufficient numbers of cells with sufficiently low pairs were obtained in the experiment for a conclusive value to be determined. The estimated error of the maximal FRET efficiency, inter-FP distance, Qeq, and EC50 is about 15%, 10%, 50%, and 30%, respectively.

| Donor | Acceptor | Extra protein(s) | Cell line | Dist (Å) | Qeq (×10–4) | EC50 (comp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactions between accessory chains | |||||||

| IFN-γR2/ECFP | IFN-γR2/EYFP | COS-1 | 0.5 | 49 | 3000 | 90–3500 | |

| IFN-γR2/ECFPm | IFN-γR2/StFP | 293T | 0.38 | 52 | 150 | 4000–8000 | |

| IFN-γR2/EGFPm | IFN-γR2/StFP | 293T | 0.38 | 59 | 15 | 2000–8000 | |

| IFN-γR2/EYFPm | IFN-γR2/StFP | 293T | 0.38 | 64 | 11 | 2000–8000 | |

| IFN-γR2/TFP | IFN-γR2/CiFPm | 293T | 0.6 | 51 | 20 | 2500 | |

| IFN-γR2/TFP | IFN-γR2/OFP | 293T | 0.16 | 70 | 4 | 2000–4000 | |

| IFN-γR2/TFP | IFN-γR2/StFP | 293T | 0.43 | 56 | 9 | 2200 | |

| IFN-γR2/TFP | IFN-γR2/ChFP | 293T | 0.37 | 65 | 3 | 1700–4400 | |

| Interactions between ligand-binding chains | |||||||

| IFN-γR1/EGFPm | IFN-γR1/OFP | 293T | 0.2 | 68 | 400 | 400–1600 | |

| IFN-γR1/EGFPm | IFN-γR1/StFP | 293T | 0.53 | 54 | 4.4 | 250–2500 | |

| Interactions between ligand-binding chain and accessory chain | |||||||

| IFN-γR1/TFP | IFN-γR2/CiFPm | 293T | 0.9 | 38 | 1200 | 35–150 | |

| IFN-γR1/TFP | IFN-γR2/CiFPm | (null) | B16 | 0.8 | 43 | 2340 | 35,150 |

| IFN-γR1/TFP | IFN-γR2/CiFPm | Lyn-ToFP | B16 | 0.7 | 48 | 11 | 37–350 |

| IFN-γR1/EGFPm | IFN-γR2/OFP | 293T | 0.65 | 48 | 100 | 80–450 | |

| IFN-γR1/EGFPm | IFN-γR2/StFP | 293T | 0.85 | 46 | 16 | 100–1500 | |

| IFN-γR1/CiFPm | IFN-γR2/ToFP | Jak1/TFP | 293T | 0.78 | 48 | 6000 | 65,600–2000 |

| IFN-γR1PL/CiFPm | IFN-γR2/ToFP | Jak1/TFP | 293T | 0.88 | 42 | 2000 | 500 |

| IFN-γR1/OFP | IFN-γR2/ChFP | Jak1/TFP, Jak2/CiFP | 293T | >0.9 | <38 | ND | 5–10 |

| Interactions between receptors and Janus kinases | |||||||

| Jak1/TFP | IFN-γR1/CiFPm | IFN-γR2/ToFP | 293T | 0.5 | 55 | 2500 | <10 |

| Jak1/TFP | IFN-γR1/CiFPm | Lyn-ToFP | 293T | 0.46 | 56 | 17,000 | 5 |

| Jak1/TFP | IFN-γR1PL/CiFPm | IFN-γR2/ToFP | 293T | 0.57 | 52 | 450 | 10 |

| Jak1/TFP | IFN-γR1PL/CiFPm | Lyn-ToFP | 293T | 0.49 | 55 | 5000 | 10 |

| Jak2/ECFPm | IFN-γR2/EYFPm | 293T | 0.85 | 37 | 350 | 100–1000 | |

| Jak2/CiFPm | IFN-γR2/StFPm | 293T (488) | 0.85 | 42 | 1000 | 10–30 | |

| Interactions between receptors and lipidated ToFPs | |||||||

| IFN-γR1/EGFPm | Lyn-ToFP | HeLa | 0.75 | 45 | 8000 | 10–100 (50) | |

| IFN-γR1/TFP | Lyn-ToFP | IFN-γR2 | B16 | 0.91 | 38 | 2000 | 150 |

| IFN-γR1/TFP | Lyn-ToFP | IFN-γR2/CiFPm | B16 | 0.85 | 41 | 400 | 50–400 |

| IFN-γR1/CiFPm | Lyn-ToFP | Jak1/TFP | 293T | 0.72 | 50 | 4500 | 50–500 |

| IFN-γR1PL/CiFPm | Lyn-ToFP | Jak1/TFP | 293T | 0.75 | 49 | 250 | 500 |

| IFN-γR2/CiFPm | Lyn-ToFP | IFN-γR1 | B16 | 0.8 | 47 | 500 | 300–2000 |

| IFN-γR2/CiFPm | Lyn-ToFP | IFN-γR1/TFP | B16 | 0.65 | 53 | 60 | 300–4000 |

| IFN-γR1/CiFPm | GAP-ToFP | IFN-γR2/TFP | B16 | 0.87 | 42 | 100 | 450–3000 |

| IFN-γR1/EGFPm | GAP-ToFP | 293T | 0.9 | 37 | 500 | 3000 | |

| IFN-γR2/TFP | GAP-ToFP | IFN-γR1/CiFPm | B16 | 0.65 | 50 | 300 | 200–1800 |

4.6. Assembling the IFN-γ receptor complex by affinity

Interactions among the various proteins composing the IFN-γ receptor complex have various affinities. Using Table 2, we can attempt to construct an interaction matrix. Inspecting Table 2, the highest-affinity interaction is between Jak1 and IFN-γR1. Interestingly, the P284L mutation that critically alters the Jak1 association site and inhibits the interaction between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2, did not strongly inhibit the binding of Jak1. The next strongest interaction is between IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2. This result is curious because this interaction does not survive immunoprecipitation while the weaker Jak2:IFN-γR2 interaction survives immunoprecipitation. Perhaps the membrane, that is dissolved during immunoprecipitation, plays a physical role in maintaining the receptor structure; data supporting this hypothesis is presented elsewhere [22]. Jak1 also plays a role in the association of IFN-γR1 and IFN-γR2. The next strongest interaction is between Jak2 and IFN-γR2. We have observed that interactions between accessory chains and Janus kinases are generally of lower affinity than interactions between the ligand-binding chain and Jak1; data from the related Type I IFN receptor support this observation [25].

At this stage we have fully assembled the biologically active IFN-γ receptor complex. Interactions between IFN-γR1 chains have a lower affinity, resembling that observed between IFN-γR1 and the GAP-ToFP fusion protein, a pair that should not interact. The interaction between IFN-γR2 chains is of very low affinity, comparable to that observed between IFN-γR2 and a Lyn-ToFP fusion protein and those between either IFN-γR2 or IFN-γR2 and GAP-ToFP; none of the latter three pairs of proteins should interact. We therefore believe that most if not all FRET between two IFN-γR2 chains or between two IFN-γR1 chains is mediated by their colocalization; we thus classify it as nonspecific.

4.7. Modifying protein:protein interactions

In the absence of other proteins, FRET between IFN-γR2 and Jak2 was quite high (Figs. 2C and 4D). When IFN-γR1 was cotransfected, the interaction between IFN-γR2 and Jak2 was unaltered in most cells but was greatly reduced in a few cells. Because IFN-γR1 levels equal or exceed those of IFN-γR2 in only a few cells when equimolar amounts of plasmids are used (Figs. 2A and 4B), we hypothesize that IFN-γR1 decreased the FRET efficiency between Jak2/ECFP and IFN-γR2/EYFP only in those few cells in which the levels of IFN-γR1 approach those of Jak2/ECFP and IFN-γR2/EYFP, and that IFN-γR1 somehow alters the configuration of Jak2 or of IFN-γR2. Proof of this requires analysis of more than two proteins simultaneously [22].

The decrease in FRET efficiency in a few cells expressing IFN-γR1, IFN-γR2/EYFP and Jak2/ECFP is only observed in the absence of IFN-γ. In the presence of IFN-γ, these few cells are no longer seen, and the interaction resembles that seen in the absence of IFN-γR1 (Fig. 2C). We speculate that the addition of IFN-γ removes the influence of IFN-γR1 on the interaction between IFN-γR2 and Jak2.

Notably, IFN-γ did not alter the interaction appreciably between IFN-γR1/CiFP and IFN-γR2/StFP (Fig. 4B), and in these cells, the levels of IFN-γR1 were comparable to those of IFN-γR2 in most cells. We speculate that conformational changes induced in the extracellular domains by IFN-γ are not effectively transmitted to the carboxy termini where the fluorescent proteins are attached. Unlike the extracellular domains and the Janus kinases that are highly structured [6], the structure of the intracellular domains are likely to be unstructured, as there are no long stretches of conserved amino acids suggestive of stable secondary protein structure (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). The lack of a firm structure may muffle conformational changes through long intracellular domains (that that of IFN-γR1) induced by ligand; conversely, the restricted mobility of a fluorescent protein attached to a Janus kinase may be more susceptible to ligand-induced changes. Conformational changes may be transmitted through IFN-γR2 to the carboxyl terminus as there is little sequence remaining in IFN-γR2 after the Jak2 association site; conformational changes are apparently easily transmitted to Jak2 from IFN-γR2, as the Jak2 attachment site is near the plasma membrane, whose sequence is also well conserved.

5. Conclusion

Overall, we have developed an experimental protocol to analyze cells to accurately gauge FRET efficiency. This protocol delineates the energy flow through the donor:acceptor system, and gives estimations of the relative levels of proteins and of donor:acceptor complexes within cells. We have shown that the analysis of many cells in a population is essential to determine the conditions necessary to observe optimal FRET between a given donor and acceptor, because the interaction between donors and acceptors is incomplete and reversible in most cells. The proper use of donor and acceptor fluorophores allows biophysically accurate measurements of FRET efficiencies between proteins in intact cells or in complex environments. We can identify conformational changes induced by additional proteins. Finally, comparison of relative affinities of donor:acceptor complexes can be used to contrast various protein complexes or distinguish specific from nonspecific interactions between donors and acceptors in live cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chin-kuei Kuo and Robin Hochstrasser of the Regional Laser Biotech Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania for their instrumental support to perform the fluorescence lifetime measurements. We also thank Gary Brewer for critical review of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases R01-AI043369, R01-AI36450, R01-AI059465 (all to S.P.), P01 AI057596 and 3P01 AI057596-05S1 (in part to S.P.).

Abbreviations

- CFS

confocal fluorescence spectroscopy

- ChFP

mCherry/cherry fluorescent protein

- CiFP

mCitrine/monomeric citrine fluorescent protein

- EBFP

enhanced blue fluorescent protein

- ECFP

enhanced cyan fluorescent protein

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- ESaFP

enhanced Sapphire fluorescent protein

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- FL

FLAG epitope (DYKDDDD)

- FP

fluorescent protein

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- IFN

interferon

- IFN-α

interferon-α

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- OFP

mOrange/orange fluorescent protein

- ORF

open reading frame

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- StFP

mStrawberry/strawberry fluorescent protein

- TFP

mTeal/teal fluorescent protein

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no financial, personal or academic conflict of interest during the research or the publication of this manuscript.

Policy and ethical statement

The work in this manuscript was carried out in accordance with ‘The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans’, with the ‘EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments’, and with the ‘Uniform Requirements for manuscripts submitted to Biomedical journals’.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2013.05.026.

References

- 1.Bach EA, Aguet M, Schreiber RD. The IFNc receptor: a paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:563–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pestka S, Kotenko SV, Muthukumaran G, Izotova LS, Cook JR, Garotta G. The interferon γ (IFN-γ) receptor: a paradigm for the multichain cytokine receptor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:189–206. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:8–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer JA, Cutrone EC, Kotenko S. The Class II cytokine receptor (CRF2) family: overview and patterns of receptor-ligand interactions. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause CD, Mei E, Xie J, Jia Y, Bopp MA, Hochstrasser RM, et al. Seeing the light: preassembly and ligand-induced changes of the interferon γ receptor complex in cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:805–15. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200065-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause CD, Lavnikova N, Xie J, Mei E, Mirochnitchenko OV, Jia Y, et al. Preassembly and ligand-induced restructuring of the chains of the IFN-γ receptor complex: the roles of Jak kinases, Stat1 and the receptor chains. Cell Res. 2006;16:55–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krause CD, Mei E, Mirochnitchenko O, Lavnikova N, Xie J, Jia Y, et al. Interactions among the components of the interleukin-10 receptor complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:377–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinsimer KS, Gratacos FM, Knapinska AM, Lu J, Krause CD, Wierzbowski AV, et al. Chaperone Hsp27, a novel subunit of AUF1 protein complexes, functions in AU-rich element-mediated mRNA decay. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5223–37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00431-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]