Abstract

There is strong evidence to show that men and women differ in terms of neurodevelopment, neurochemistry and susceptibility to neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disease. The molecular basis of these differences remains unclear. Progress in this field has been hampered by the lack of genome-wide information on sex differences in gene expression and in particular splicing in the human brain. Here we address this issue by using post-mortem adult human brain and spinal cord samples originating from 137 neuropathologically confirmed control individuals to study whole-genome gene expression and splicing in 12 CNS regions. We show that sex differences in gene expression and splicing are widespread in adult human brain, being detectable in all major brain regions and involving 2.5% of all expressed genes. We give examples of genes where sex-biased expression is both disease-relevant and likely to have functional consequences, and provide evidence suggesting that sex biases in expression may reflect sex-biased gene regulatory structures.

Men and women differ in terms of their neurochemistry, behaviour and susceptibility to disease. Here the authors show that sex differences in gene expression and splicing are widespread in adult human brain, and that sex-biased expression is likely to have functional consequences.

Men and women differ in terms of their neurochemistry, behaviour and susceptibility to disease. Here the authors show that sex differences in gene expression and splicing are widespread in adult human brain, and that sex-biased expression is likely to have functional consequences.

The issue of differences between the ‘male brain’ and ‘female brain’ has been endlessly debated in the psychological literature and popular press. Sex differences in human brain structure, neurochemistry, behaviour and susceptibility to neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disease have all been reported1,2,3. Understanding the molecular basis of observed sex differences in structure, neurochemistry, behaviour and susceptibility to disease is of obvious importance both to basic neurobiology and neuropathophysiology. However, the limited scope and power of existing studies make it difficult to place these discussions in a molecular context4,5,6,7,8. The maximum number of adults investigated within any single study is 18, with only one study exploring sex-biased alternative splicing in a genome-wide manner4. Furthermore, while the existence of sex-specific genetic architectures in humans has been postulated9, genome-wide analyses of genetic variants associated with variation in gene expression in one sex, but not the other, have never been conducted in human brain.

To address these limitations, we analysed data from the UK Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC)10,11. This data set is particularly valuable because (i) it is large with post-mortem samples originating from 137 neuropathologically confirmed control individuals (Supplementary Data 1 and 2), (ii) up to 12 central nervous system (CNS) regions have been sampled from each individual and (iii) transcriptome profiling was performed using the Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST Array, which features 1.4 million probe sets assaying expression across each individual exon. In order to explore the possibility of sex-biased gene regulatory architectures we also conducted an expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis with the aim of finding significant interactions between sex and genotype. To maximize power, we used paired genotyping and gene-level expression data provided jointly by the North American Brain Expression Consortium12,13 and UKBEC. In this way this study provides unequivocal evidence that sex-biased gene expression in the adult human brain is widespread in terms of both the number of genes and range of brain regions involved. We also show that in some specific cases, molecular differences are likely to have functional consequences relevant to human disease and finally that sex biases in expression may reflect sex-biased gene regulatory structures.

Results

Discovery of sex-biased gene expression and splicing

In total we analysed 1,182 post-mortem brain samples dissected from frontal cortex, occipital cortex (BA17, primary visual cortex), temporal cortex, intralobular white matter, thalamus, putamen, substantia nigra, hippocampus, hypothalamus, medulla, cerebellar cortex and spinal cord. These samples originated from 137 individuals of which 101 were male and 36 were female. The demographic details related to these samples are provided in Table 1. While we found no significant difference in brain pH (Mann–Whitney P-value=0.643, N=10), cause of death (χ2 test P-value=0.339, N=137) or age at death (Mann–Whitney P-value=0.067, N=137) between samples originating from men and women, we did detect a significant difference in the post-mortem interval between the sexes (Mann–Whitney P-value=0.037, N=137). However, we verified that none of the findings reported in this study could be accounted for by sex differences in any of these factors (Methods).

Table 1. Summary of the demographic details of the individuals sampled in this study stratified by sex.

| Sex | N | Age (years) | PMI (h) | pH | Modal cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 36 | 64 (20–102) | 41 (1–96) | 6.34 (5.44–6.58) | IHD (30.6%) |

| Male | 101 | 57 (16–91) | 47 (1.5–99) | 6.34 (5.42–6.63) | IHD (48.5%) |

Median values and ranges are supplied

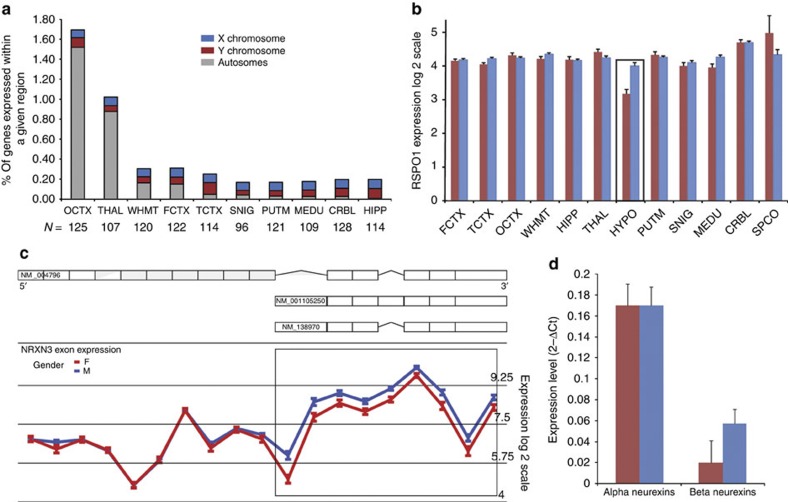

Sex-biased expression and splicing was investigated in each brain region separately and by averaging gene-level signals across all brain regions. This analysis demonstrated that sex-biased gene expression was widespread in terms of the numbers of genes, chromosomes and range of brain regions involved (Fig. 1a). Using a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.01 for gene-level changes (unpaired t-test, N ranging from 13–128; Supplementary Data 3) and a more stringent FDR of 0.001 for calling alternate splicing (due to the potentially higher false positive rate; unpaired t-test, N ranging from 13–128, Supplementary Data 4), we identified 448 genes with evidence of sex-biased expression, equating to 2.6% (448/17,501) of all genes expressed in the human CNS. Over 5% of regional findings are validated using qRT–PCR or have supporting evidence in the literature (Supplementary Data 5).

Figure 1. Sex-biased gene expression is widespread.

(a) Bar chart showing the percentage of expressed genes with evidence of sex-biased expression or splicing in each brain region. FCTX, frontal cortex; TCTX, temporal cortex; OCTX, occipital cortex; WHMT, white matter; HIPP, hippocampus; THAL, thalamus; HYPO, hypothalamus; PUTM, putamen; SNIG, substantia nigra; MEDU, medulla; CRBL, cerebellum; SPCO, spinal cord. The number of samples analysed for each region is provided as additional labelling on the x axis. (b) RSPO1 expression in women (red) and men (blue) in the human CNS. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (N=13). Hypothalamus (boxed) is the only brain region showing significant sex-biased gene expression. (c) Gene structure of NRXN3 and expression levels (y axis) plotted for each probe set (x axis) covering NRXN3 in males (blue line) and females (red line) in thalamus. All differentially expressed exons map to β-neurexins (boxed region) indicating sex-biased expression of these transcripts. Error bars represent the Standard error of the mean (s.e.m). (d) Successful quantitative RT–PCR validation of α-neurexin and β-neurexin expression in thalamus in men (blue) and women (red). The 2−ΔCt values have been plotted to show relative gene expression levels. Error bars represent the s.e.m. (N=29).

Over 85% of the identified genes (395/448) were detected on the basis of sex-biased splicing alone, suggesting that qualitative as opposed to quantitative differences in gene expression drive sexual dimorphism in adult brain. As 95% of genes with sex-biased splicing and 34% of genes with sex-biased gene-level expression map to autosomes, sex differences were not accounted for by the sex chromosomes alone and all autosomes were involved (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, sex-biased expression was detected in all 11 brain regions, making spinal cord the exception, though even this finding is probably explained by the small sample size available for this tissue (N=13). Thus, we show that in common with other species, including fruit flies, fish and rodents, sex-biased gene expression and splicing is a frequent phenomenon in adult human brain1,2,3.

The biological significance of sex-biased expression

We explored the biological significance of this observation by investigating our list of genes with sexually dimorphic expression for involvement in human disease. We found a significant enrichment of disease-related genes (as defined by membership in the OMIM catalogue) within our list (Yates-corrected χ2 P-value=3.58 × 10−9, N=448). Of the 114 genes with both evidence of sex-biased expression and an OMIM entry, 12 mapped to the sex chromosomes, with the remaining 102 genes located on autosomes. Amongst these genes, 39 were associated with a disease with a sex-biased incidence, 5 were associated with diseases directly affecting the development/maintenance of the reproductive system and 3 were implicated in breast, ovarian or prostate cancer (Supplementary Data 6). These findings suggest that sex differences in gene expression in human brain relate and may even help explain well-recognised differences between men and women in disease incidence and presentation14,15,16,17,18,19.

RSPO1 is one of the autosomal genes highlighted by this analysis. Although expressed throughout the brain, RSPO1 has significantly higher expression (1.8-fold change, unpaired t-test, P-value=4.09 × 10−6, N=13) in males only in the hypothalamus (Fig. 1b). Given the importance of this region in maintenance of reproductive functions, and that disruption of RSPO1 in XX individuals leads to a sex-reversal phenotype20, this finding suggests that sex-biased gene expression can have important functional consequences. Furthermore, this example demonstrates that although sex-biased gene expression may be widespread it is not necessarily uniform and implies that some brain regions may be more sexually dimorphic than others. In fact, focusing on the 10 brain regions with similar sample sizes and using the percentage of expressed genes (as documented in Supplementary Table S1) with sex-biased expression as a measure of sexual dimorphism, we found wide variation within the human CNS (Fig. 1a) and identified the primary visual cortex as the most sexually dimorphic region (1.8%). However, we recognise that this measure of sexual dimorphism has limitations because it neither accounts for the magnitude of sex differences in expression nor does it recognise major qualitative differences (such as the expression of Y chromosome genes with no X chromosome orthologue). With regard to the former concern, it should be recognised that there was considerable variability in the magnitude of sex differences in gene level expression amongst autosomal genes (median fold change=1.29).

NRXN3, which has been implicated in autism21, is another disease-relevant gene identified by this analysis, but in this case due to sex-biased splicing. In common with all neurexin genes, NRXN3 has two major isoforms, α-neurexins and β-neurexins generated through the use of two alternate promoters22. Whereas α-neurexins were expressed similarly in men and women, β-neurexin expression was significantly lower in women in the thalamus (unpaired t-test, P-value=2.67 × 10−13, N=107; Fig. 1c,d). Given that α- and β-neurexins have distinct functions and assuming that sex-biased splicing is not restricted to adult life, this observation could be important in understanding the higher incidence of autism in males23,24. Furthermore, within NRXN3’s signalling pathway are genes reported to be androgen-responsive25 (including NLGN4X, GRIA1 and GRIA2), adding weight to the idea that there may indeed be differences in neurexin–neuroligin signalling between males and females. In fact, amongst genes with evidence of sex-biased splicing generally there was a significant enrichment of androgen25 but not oestrogen-responsive26 genes (androgens, P-value=9.64 × 10−12; oestrogens, P-value=0.97, Yates-corrected χ2 tests, N=395). This would suggest that sex-biased splicing is a means of regulating responses to sex hormones, predominantly androgens, though this particular finding may be influenced by the fact that the majority of women included in this study would be predicted to be post-menopausal on the basis of age27 (Methods).

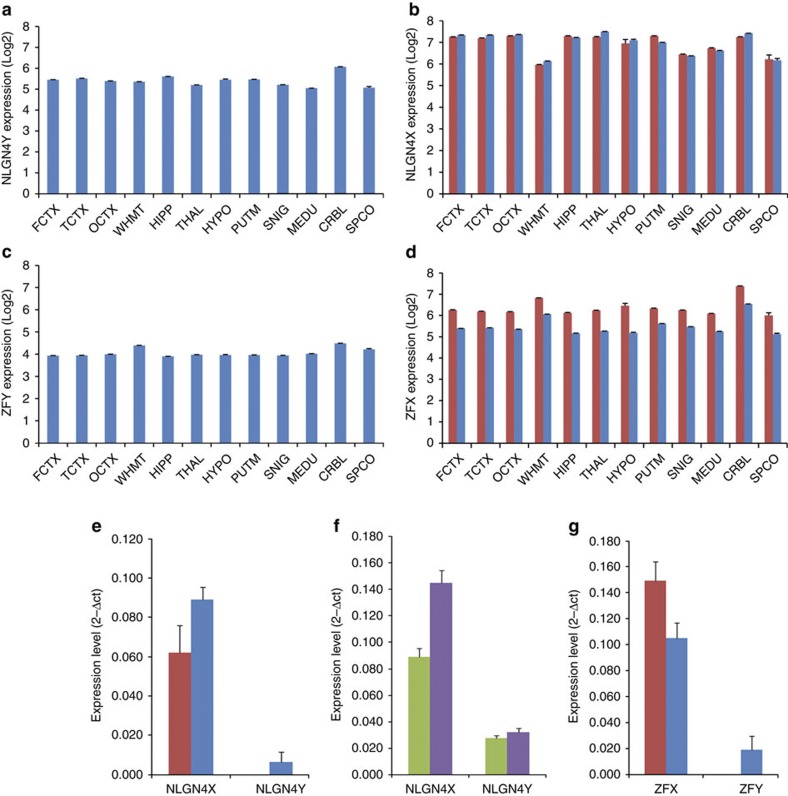

Within our list of genes with sex-biased expression are some notable omissions, namely NLGN4X, PRKX and TMSB4X. These genes are worth noting because they are all non-pseudoautosomal X chromosome genes with Y-linked copies (NLGN4Y, PRKY and TMSB4Y) that are expressed in human brain28,29. Consequently in order to have two expressed alleles in both male and female brain tissue these X chromosome genes would be expected to escape X inactivation resulting in higher expression in women as compared with men30,31. However, in all three cases (and in contrast to genes like ZFX) expression appeared to be similar in men and women, suggesting unequal dosage of these ‘functional’ orthologues between the sexes (Fig. 2a–d). For example, although NLGN4Y was expressed throughout the male CNS, there was no significant sex difference in the expression of NLGN4X either by array or quantitative RT–PCR measurements (Fig. 2e–f). Furthermore, the pattern of expression within the CNS differed between the orthologues, suggesting that there are subtle differences in their respective functions (Fig. 2). Given that loss-of-function mutations in NLGN4X are linked to autism32, sexually dimorphic expression of NLGN4 species might also relate to the higher incidence of autism within men23,24.

Figure 2. Variable dosage compensation between X chromosome genes with Y-linked orthologues.

(a) Bar chart to show the expression of NLGN4Y in men in all CNS regions. (b) Bar chart to show the expression of NLGN4X in women (red bars) and men (blue bars) in all CNS regions. (c) Bar chart to show the expression of ZFY in men in all CNS regions. (d) Bar chart to show the expression of ZFX in women (red bars) and men (blue bars) in all CNS regions. (e) Quantitative RT–PCR validation of NLGN4X and NLGN4Y expression in women (red bars) and men (blue bars) in the thalamus. The 2−ΔCt values have been plotted to show relative gene expression levels. (f) Quantitative RT–PCR validation of NLGN4X and NLGN4Y expression in white matter (green bars) and thalamus (purple bars) in males. The 2−ΔCt values have been plotted to show relative gene expression levels. (g) Quantitative RT–PCR validation of ZFX and ZFY expression in women (red bars) and men (blue bars) in the thalamus. The 2−ΔCt values have been plotted to show relative gene expression levels. The error bars in all panels represent the s.e.m. (N=34).

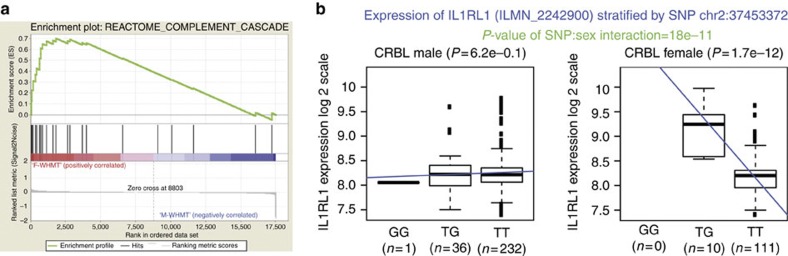

Moving beyond single genes, we looked for sexually dimorphic expression of entire gene networks. Using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)33 we tested 71 CNS-relevant gene sets from the KEGG34,35, Reactome36 and BioCarta pathway databases (Supplementary Data 7) in all 12 CNS regions. Significant sex-biased enrichment in at least one region (P-value<0.05, where enrichment P-values were estimated using an empirical permutation-based procedure) was detected for 12 canonical pathways of which 7 could be considered independent (Supplementary Table S2). For example, we found enrichment of two immune-related pathways in females in white matter (Fig. 3a), suggesting that sex-specific thresholds for susceptibility to immune-mediated diseases might exist and potentially explaining the higher incidence of multiple sclerosis14, a white matter disease of immune origin in women.

Figure 3. Sex-biased expression of immune system-related genes.

(a) GSEA results for the Reactome complement cascade gene set demonstrated enrichment of this pathway in female as compared with male white matter (nominal P-value=0.04, enrichment P-values are estimated using an empirical permutation-based procedure). The top portion of the plot shows the running enrichment score for the gene set as the analysis walks down the ranked list and the presence of a distinct peak at the beginning suggests significant enrichment in women. The middle portion of the plot shows where members of the complement cascade gene set appear in the ranked list of genes. The bottom portion of the plot shows the value of each gene’s correlation with the phenotype, sex. (b) Box plots showing IL1RL1 expression by genotype at rs34990056 (chr2: 37453372) (GG, TG and TT) in male and female cerebellum samples demonstrate a significant association with gene expression in women only. The bottom and top of the box are the first and third quartiles, and the band inside the box is the median value. Whiskers extend from the box to 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Evidence in support of sex-biased gene regulation

This finding also raises the possibility of sex-biased gene regulatory architectures. This idea was explored by conducting an eQTL analysis with the aim of finding significant interactions between sex and genotype. To maximize power, we used paired genotyping and gene level expression data provided jointly by the North American Brain Expression Consortium12,13 and UKBEC10,11 on 390 cerebellar and 390 frontal cortex samples (121 women and 269 men). Although no signals passed a Bonferroni correction of multiple testing (~3.7 × 10−12), amongst the genes associated with the most significant sex-biased eQTLs (P-value cutoff <1 × 10−9; Supplementary Data 8 and 9) there was enrichment of genes related to the immune system (Benjamini-corrected modified Fisher’s Exact P-value=0.02), interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 being an example (IL1RL1/rs34990056, P-value for sex-genotype interaction=1.77 × 10−11, N=390; Fig. 3b). While these results are not conclusive, they are consistent with the well-recognised sex-bias in the incidence of immune-related diseases37 and could help explain the sex-bias in the incidence of CNS diseases with a known immune component, such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease38,39.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive, genome- and CNS-wide analysis of sex-biased gene expression, splicing and regulation in the control adult CNS. The first and most important finding of this study is that once we account for alternative splicing, sex-biased gene expression in the adult human brain is widespread both in terms of the number of genes and range of brain regions involved. We found that 2.6% of the genes expressed in the human CNS show evidence of differential expression by sex in at least one brain region and that sex differences could be detected in all eleven brain regions analysed. Secondly, although sexually dimorphic gene expression is common in the human brain, it is not uniform, with some genes showing region-specific sex-biased expression and some brain regions possibly having a higher burden of sex-biased expression. Thirdly, this study provides evidence to suggest that sex-biased gene expression and splicing is likely to have functional consequences relevant to human disease, with a significant enrichment of disease-related genes (as defined by membership in the OMIM catalogue) among our list of genes with sex-biased expression. Finally, we present evidence in support of the existence sex-biased eQTLs in humans, implying that sex-specific gene regulatory structures may exist in human brain. Although we recognize that this study has its limitations, it does provide the most complete information to date on sex-biased gene expression, splicing and regulation in the adult human brain. As such we hope that it will become an important resource for the neuroscience community.

Methods

Collection of samples analysed by Affymetrix Exon Arrays

CNS tissues originating from 137 control individuals was collected by the Medical Research Council (MRC) Sudden Death Brain and Tissue Bank, Edinburgh, UK40, and the Sun Health Research Institute (SHRI) an affiliate of Sun Health Corporation, USA41. A detailed description of the samples used in the study, tissue processing and dissection is provided in the study by Trabzuni et al.10 and in Supplementary Data 1. All samples had fully informed consent for retrieval and were authorized for ethically approved scientific investigation (National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and Institute of Neurology Research Ethics Committee, 10/H0716/3).

Processing of samples analysed by Affymetrix Exon Arrays

Total RNA was isolated from human post-mortem brain tissues using the miRNeasy 96 kit (Qiagen). The quality of total RNA was evaluated by the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent) before processing with the Ambion WT Expression Kit and Affymetrix GeneChip Whole Transcript Sense Target Labelling Assay, and hybridization to the Affymetrix Exon 1.0 ST Arrays following the manufacturers’ protocols. Hybridized arrays were scanned on an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G. Further details regarding RNA isolation, quality control and processing are reported in Trabzuni et al.10. A full list of the CEL files used in this study is provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Analysis of Affymetrix Exon Array data. All arrays were pre-processed using Robust Multi-array Average quantile normalisation with GC background correction (GC-RMA)42 and log2 transformation in Partek’s Genomics Suite v6.6 (Partek Incorporated, USA). We also calculated the ‘detection above background metric’ (DABG) using Affymetrix Power Tools (Affymetrix). After re-mapping the Affymetrix probe sets onto human genome build 19 (GRCh37) using Netaffx annotation file HuEx-1_0-st-v2 Probeset Annotations, Release 31, we restricted analysis to 174,228 probe sets annotated with gene names, containing at least three probes with unique hybridization and DABG P-values <0.001 in 50% of male or female individuals. The gene-level expression was calculated for up to 17,501 genes by using the median signal of probe sets corresponding to each gene.

Using the age at death and the reported age-related probability of being pre-menopausal in the US Caucasian population27 we predicted that 67% of the female donors (n=24) were post-menopausal, whereas 17% (n=6) were likely to be pre-menopausal. As we were unable to detect any significant differences in gene expression between pre- and post-menopausal women our analysis is limited to sex differences alone.

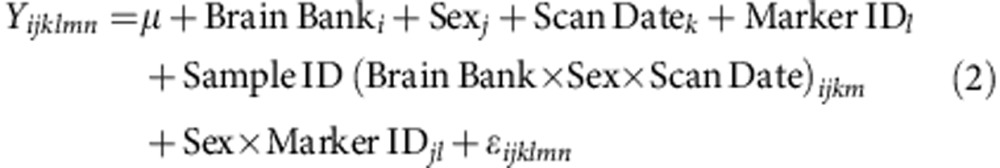

Sex-biased expression and splicing was investigated in each brain region separately using Partek’s mixed-model ANOVA (equation 1) and alternative splice ANOVA (equation 2, Partek Genomics Suite v6.6) as described below:

|

Where Yijkl represents the lth observation on the ith Brain Bank jth Sex kth Scan Date, μ is the common effect for the whole experiment, εijkl represents the random error present in the lth observation on the ith Brain Bank jth Sex kth Scan Date. The errors εijkl are assumed to be normally and independently distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation δ for all measurements. Brain Bank and Scan Date are modelled as random effects.

|

Where Yijklmn represents the nth observation on the ith Brain Bank jth Sex kth Scan Date lth Marker ID mth Sample ID, μ is the common effect for the whole experiment. εijklmn represents the random error present in the nth observation on the ith Brain Bank jth Sex kth Scan Date lth Marker ID mth Sample ID. The errors εijklmn are assumed to be normally and independently distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation δ for all measurements. Marker IDl is exon-to-exon effect (alt-splicing independent to tissue type).

Gender × Marker IDjl represent whether an exon expresses differently in different levels of the specified Alternative Splice Factor(s). Sample ID (Brain Bank × Gender × Scan Date)ijkm is a sample-to-sample effect. Brain Bank, Scan Date and Sample ID are modelled as random effects.

In order to reduce the likelihood of false positives only probe sets called as present in both male and female samples were analysed for evidence of alternative splicing by sex. In all types of analysis, the date of array hybridisation and brain bank (SHRI or MRC Sudden Death Brain Bank) were included as cofactors to eliminate batch effects as discussed in detail in Trabzuni et al.10 All P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the FDR step-down method.

We also investigated the value of integrating data across the different brain regions based on the idea that small yet consistent differences in gene expression may exist between male and female brain samples and while such differences might not be significant in a single brain region they might be detected when all samples are considered together. In order to test this approach we calculated the average expression of each gene-level signal across all regions for each individual. The resulting values were tested for sex-biased expression (including scan date and brain bank as covariates).

In order to ensure that any reported sex differences in gene level expression or splicing could not be explained by any of the other known covariates, we performed additional analyses, where we modelled the effects of cause of death, post-mortem interval, age at death and RIN as well as the factors described above. We found that in fact the findings reported remained substantively the same.

Quantitative RT–PCR

Aliquots of total RNA previously extracted from each brain region and analysed on Exon Arrays were used for validation by quantitative RT–PCR analysis. These experiments were performed on a subset of samples (N=85) and analysed for the expression of genes/transcripts using human-specific TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, UK). RPLP0-, TUBB- and UBC-specific assays were used as endogenous controls. Samples were analysed using Fluidigm 96.96 Dynamic (Fluidigm Europe) arrays with assay triplicates in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA (100 ng) was used as input, reverse transcription performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol and amplified as described in the ‘Fluidigm Specific Target Amplification Quick Reference Manual’ (Fluidigm, Europe). The Ct value (cycle number at threshold) was used to calculate the relative amount of mRNA molecules. The Ct value of each target gene was normalized by subtraction of the Ct value from the geometric mean of the three endogenous control genes to obtain the ΔCt value. The relative gene expression level was shown as 2−ΔCt. Sex-biased gene expression or splicing candidates were considered confirmed if the P-value calculated by unpaired t-test was <0.05.

Gene set enrichment analysis

GSEA was performed using GSEA v2.0.6 software33 with phenotype permutation. We investigated sex-biased enrichment of 71 gene sets annotated by the KEGG34,35), Reactome36 and BioCarta pathway databases with relevance to CNS function (Supplementary Table S1).

DNA genotyping and imputation

Genomic DNA was extracted from subdissected samples of human post-mortem brain tissue using either Qiagen’s DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, UK) or phenol–chloroform. The samples provided by either the MRC Sudden Death Brain and Tissue Bank or San Health Research Institute were genotyped on the Illumina Infinium Omni1-Quad BeadChip and on the Immunochip, a custom genotyping array designed for the fine-mapping of auto-immune disorders43. The other samples were genotyped using the Illumina Infinium HumanHap550 v3 (Illumina, USA). In all cases, the BeadChips were scanned using an iScan (Illumina) with an AutoLoader (Illumina, USA). GenomeStudio v.1.8.X (Illumina, USA) was used for analysing the data and generating SNP calls.

After standard quality controls both genotype data sets were combined and imputed using MaCH44,45 and Minimac using the European panel of the 1,000 Genomes Project (March 2012: Integrated Phase I haplotype release version 3, based on the 2010-11 data freeze and 2012-03-14 haplotypes). We used the resulting ~5.5 million SNPs with good post-imputation quality (Rsq>0.50) and minor allele frequency of at least 5%.

Processing of samples analysed by illumina expression arrays

Subdissected samples from cerebellar and frontal cortex samples originating from 390 control individuals were frozen before processing12,13,43. Total RNA was extracted from subdissected samples using either Qiagen’s miRNeasy Kit (Qiagen,UK) or using a glass-Teflon homogenizer and 1 ml TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was biotinylated and amplified using the Illumina TotalPrep-96 RNA Amplification Kit and directly hybridized onto HumanHT-12 v3 Expression BeadChips (Illumina Inc.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of illumina expression arrays

In order to maximise the number of samples available, this analysis was performed using expression data generated from 390 individuals who were expression-profiled on the HT-12 v3 BeadChip array, some of whom had also been analysed using the Exon Arrays. Raw intensity values for each probe were transformed using the cubic spline normalization method and then log2-transformed for mRNA analysis. After re-mapping the annotation for probes according to ReMOAT46, we restricted the analysis to probes that uniquely hybridized, were associated with gene descriptions, were located on autosomal chromosomes and that passed Illumina Detection P-values of <0.01 in >10% of male or female individuals. We also removed all probes containing SNPs or indels present in the European panel of the 1,000 Genomes Project (March 2012: Integrated Phase I haplotype release version 3, based on the 2010-11 data freeze and 2012-03-14 haplotypes) with a frequency of at least 1%. This resulted in the analysis of 13,425 transcripts in cerebellum and 13,396 transcripts in frontal cortex. The resulting expression data was adjusted for age, post-mortem interval and batch effects.

Identification of sex-biased eQTLs

A combined data set of 390 individuals (121 women and 269 men) was used to identify expression QTLs that behave differently in men and women. For each probe, an expression value that exceeded 3 s.d. from the mean was considered as an outlier and removed from analysis. The outlier detection was run in men and women separately and a total of 1.2% of the expression values was removed. The QTL analysis was run for each probe against a SNP, sex and the interaction term between sex and SNP in MatrixEQTL47. The P-value for the interaction term was used to select combinations of SNPs and probes for further analysis in R ( http://www.r-project.org/). We treated multiple expression QTLs from a tissue as one signal if the SNPs involved were clustered with linkage disequilibrium >0.50 and report the most significant expression QTL. The P-value threshold corresponding to the Bonferroni correction of multiple testing is ~3.7 × 10−12.

Author contributions

D.T., M.R. and NABEC performed the experiments. M.R., A.R., M.E.W. and S.I. analysed the data. R.W., C.S. procured and examined the tissue. M.R., J.H. and M.W. designed the study. M.R. wrote the manuscript, which all authors edited.

Additional information

Accession codes: Affymetrix exon array data has been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE46706. Illumina HT12-v3 Expression Beadchip array data has been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE36192.

How to cite this article: Trabzuni, D. et al. Widespread sex differences in gene expression and splicing in the adult human brain. Nat. Commun. 4:2771 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3771 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1 and S2 and Supplementary Note 1

Demographic details of donors

Sample details

List of genes with evidence of sex-biased expression in at least one CNS region

List of genes with evidence of sex-biased splicing in at least one CNS region

Evidence for sex-biased gene expression and splicing independent of the array results

Table of autosomal genes showing sex-biased expression or splicing in the human CNS, which are also members of the OMIM catalogue

List of all canonical pathways tested using GSEA

List of sex-biased expression QTLs detected in the cerebellar cortex

List of sex-biased expression QTLs detected in the frontal cortex

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MRC through the MRC Sudden Death Brain Bank (C.S.), a Project Grant (to J.H. and M.E.W.) and Training Fellowship (G0802462 to M.R.). D.T. was supported by the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Saudi Arabia. The work performed by the North American Brain Expression Consortium was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, part of the US Department of Health and Human Services; project number ZIA AG000932-04. We are grateful to the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona for the provision of human biospecimens. The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Computing facilities used at King’s College London were partially supported by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

References

- Cahill L. Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 477–484 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove K. P., Mazure C. M. & Staley J. K. Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 847–855 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazin E. & Cahill L. Sex differences in molecular neuroscience: from fruit flies to humans. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 9–17 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. J. et al. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature 478, 483–489 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simunovic F., Yi M., Wang Y., Stephens R. & Sonntag K. C. Evidence for gender-specific transcriptional profiles of nigral dopamine neurons in Parkinson disease. PLoS One 5, e8856 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter M. P. et al. Gender-specific gene expression in post-mortem human brain: localization to sex chromosomes. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 373–384 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert C. S. et al. Transcriptome analysis of male-female differences in prefrontal cortical development. Mol. Psychiatry 14, 558–561 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri I. et al. Effects of gender on nigral gene expression and parkinson disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 26, 606–614 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober C., Loisel D. A. & Gilad Y. Sex-specific genetic architecture of human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 911–922 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabzuni D. et al. Quality control parameters on a large dataset of regionally dissected human control brains for whole genome expression studies. J. Neurochem. 119, 275–282 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabzuni D. et al. MAPT expression and splicing is differentially regulated by brain region: relation to genotype and implication for tauopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 4094–4103 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J. R. et al. Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000952 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D. G. et al. Integration of GWAS SNPs and tissue specific expression profiling reveal discrete eQTLs for human traits in blood and brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 47, 20–28 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker B. G. et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. 3. Multivariate analysis of predictive factors and models of outcome. Brain 114, (Pt 2): 1045–1056 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman A., Kahn R. S. & Selten J. P. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 565–571 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K. et al. Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia: The EURODEM Studies. EURODEM Incidence Research Group. Neurology 53, 1992–1997 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gater R. et al. Sex differences in the prevalence and detection of depressive and anxiety disorders in general health care settings: report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55, 405–413 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller I. N. & Cronin-Golomb A. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease: clinical characteristics and cognition. Mov Disord. 25, 2695–2703 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. et al. Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr. 22, 1–15 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parma P. et al. R-spondin1 is essential in sex determination, skin differentiation and malignancy. Nat. Genet. 38, 1304–1309 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaags A. K. et al. Rare deletions at the neurexin 3 locus in autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 133–141 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A. M. & Kang Y. Neurexin-neuroligin signaling in synapse development. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 43–52 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newschaffer C. J. et al. The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu. Rev. Public Health 28, 235–258 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuse D. H. Imprinting, the X-chromosome, and the male brain: explaining sex differences in the liability to autism. Pediatr. Res. 47, 9–16 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M. et al. Androgen-responsive gene database: integrated knowledge on androgen-responsive genes. Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 1927–1933 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Han H. & Bajic V. B. ERGDB: Estrogen Responsive Genes Database. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 32, D533–D536 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato I. et al. Prospective study of factors influencing the onset of natural menopause. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 51, 1271–1276 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaletsky H. et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature 423, 825–837 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. T. et al. The DNA sequence of the human X chromosome. Nature 434, 325–337 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berletch J. B., Yang F., Xu J., Carrel L. & Disteche C. M. Genes that escape from X inactivation. Hum. Genet. 130, 237–245 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard E. & Disteche C. M. Dosage compensation in mammals: fine-tuning the expression of the X chromosome. Genes Dev. 20, 1848–1867 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamain S. et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat. Genet. 34, 27–29 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. & Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S., Sato Y., Furumichi M. & Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D109–D114 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews L. et al. Reactome knowledgebase of human biological pathways and processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D619–D622 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombe P. A., Greer J. M. & Mackay I. R. Sexual dimorphism in autoimmune disease. Curr. Mol. Med. 9, 1058–1079 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor S., Puentes F., Baker D. & van der Valk P. Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 129, 154–169 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung A., Vizcaychipi M., Lloyd D., Wan Y. & Ma D. Central nervous system inflammation in disease related conditions: mechanistic prospects. Brain Res. 1446, 144–155 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar T. et al. Tissue and organ donation for research in forensic pathology: the MRC Sudden Death Brain and Tissue Bank. J. Pathol. 213, 369–375 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach T. G. et al. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987-2007. Cell Tissue Bank 9, 229–245 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry R. A. et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalls M. A. et al. Imputation of sequence variants for identification of genetic risks for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet 377, 641–649 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Willer C., Sanna S. & Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10, 387–406 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Willer C. J., Ding J., Scheet P. & Abecasis G. R. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet. Epidemiol. 34, 816–834 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Morais N. L. et al. A re-annotation pipeline for Illumina BeadArrays: improving the interpretation of gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e17 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalin A. A. Matrix eQTL: Ultra fast eQTL analysis via large matrix operations. Bioinformatics 28, 1353–1358 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1 and S2 and Supplementary Note 1

Demographic details of donors

Sample details

List of genes with evidence of sex-biased expression in at least one CNS region

List of genes with evidence of sex-biased splicing in at least one CNS region

Evidence for sex-biased gene expression and splicing independent of the array results

Table of autosomal genes showing sex-biased expression or splicing in the human CNS, which are also members of the OMIM catalogue

List of all canonical pathways tested using GSEA

List of sex-biased expression QTLs detected in the cerebellar cortex

List of sex-biased expression QTLs detected in the frontal cortex