Abstract

Background:

Augmentation of collateral flow is proposed as a method to reduce ischemic injury in the posterior circulation. However, collateral formation in basilar artery stenosis (BAS) and basilar artery occlusion (BAO) has not been studied thoroughly.

Methods:

We identified 24 consecutive patients admitted over a 4-year period with angiographically demonstrated BAS of more than 50% or occlusion. Angiographic images were reviewed for pattern of collaterals by a blinded reviewer. A new grading system by Qureshi [1] (Qureshi AI (2012) J Neuroimaging in press) was utilized for grading. Grades I and II had retrograde filling of the basilar artery through PCA with or without filling of the superior cerebellar artery, respectively. Grades III and IV were bilateral or unilateral anastomoses of cerebellar arteries or PCAs, respectively. Risk factors such as age, gender, race/ethnicities, co-morbidities, NIHSS sore on admission and discharge, tPA administration, in-hospital complications, and discharge status measured by the modified Rankin score were ascertained.

Results

The collaterals were categorized as: Grade I A (n = 8), Grade IIIA (n = 5), and none (n = 11). No patient had Grade II collaterals. Grade IA collaterals were more frequent in patients with BAO than those with BAS. The rate of good outcomes (mRS 0–2) at discharge was significantly higher among patients with IA collaterals compared with patients with grade IIIA collaterals (62% vs. 20%). The rate of good outcomes was 54% of patients without collaterals.

Conclusions

The pattern of collateral formation in BAS and BAO varies and is associated with patient outcomes.

Keywords: basilar artery occlusion, basilar artery stenosis, collaterals, Qureshi grading scale, posterior circulation collaterals

Introduction

Basilar artery occlusion (BAO) accounts for 1% of all strokes by 2007 [1, 2]. The most common causes for BAO are atherosclerotic occlusions resulting from local thrombosis due to severe stenosis and embolic occlusions from cardiac and large artery sources [3, 4]. In acute BAO the patient may present with altered mental status, dysarthria, paresis, hemiplegia, ataxia, cranial nerve deficits, or supranuclear oculomotor disturbances. Although prognosis of such patients can vary, BAO has been mostly associated with a poor outcome [2, 5, 6]. In the Warfarin and Aspirin for Symptomatic Intracranial Disease study (WASID), basilar artery stenosis (BAS) had the highest stroke rate in any vascular territory (15.0 per 100 patient-years), and also the highest stroke rate in the territory of the stenotic artery (10.7 per 100 patient-years) [7].

Several studies have determined the pattern of collaterals in both occlusions and stenosis involving the anterior circulation. Methods to categorize the patterns of collaterals in the anterior circulation have been described and found to be predictive of patient outcomes [8–10]. Augmentation of collateral flow has been proposed to reduce the ischemic injury in the territory of occluded or stenotic artery [9, 10]. Strategies such as induced hypertension using intravenous vasopressors [11–13] and partial aortic balloon occlusion [14] have focused on augmentation of collaterals. While there are anectodal reports of collateral formation in the posterior circulation, there appears to be limited data on patterns and associated prognostic value [15].

Methods

We identified patients with BAS or occlusions who were admitted to one of the two hospitals from a prospective endovascular procedure database which records information regarding the procedural components, devices used, and intraprocedural medication with doses. The protocol for collecting data was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution as part of a standardized database.

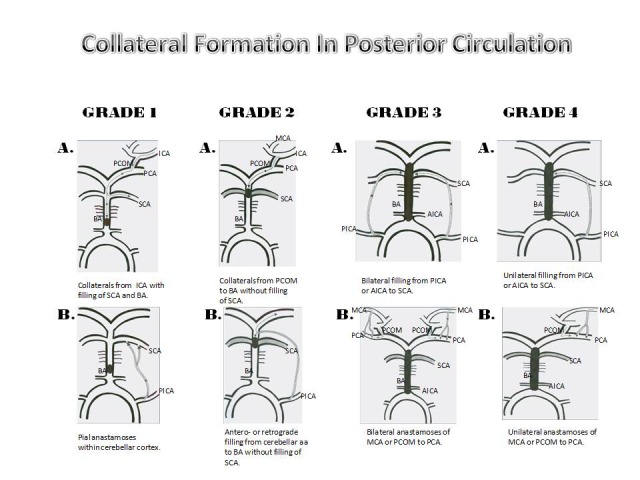

The angiographic images of each patient were reviewed by a single reviewer who was unaware of the patient outcomes. The presence of any collateral flow was identified and further categorized using a new grading system proposed by Qureshi [1] designed specifically to assess collaterals in BAS and occlusion. The classification includes four grades: Grade I represents presence of retrograde filling of the basilar artery through PCA with filling of the superior cerebellar artery. Grade II represents presence of retrograde filling of the basilar artery through the PCA but no filling of the superior cerebellar artery. Grade III is when there are bilateral anastomoses of cerebellar arteries or PCAs. Grade IV is when there are unilateral anastomoses of cerebellar arteries or PCAs [1] (see Figure 1). We collected the following information from each eligible patient’s medical records: (1) age, sex, and race/ethnicity and (2) the risk factors present before onset of diagnosis: for example, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, current cigarette smoking, and hyperlipidemia. We attempted to obtain information not mentioned in the medical records by retrospectively reviewing previous medical records, results of previous imaging and laboratory tests, and the pharmacy record from preceding clinic visits. The admission and discharge NIHSS score, IV tPA or endovascular treatment received, occurrence of symptomatic ICH, and modified Rankin scores (mRS) at discharge were recorded. Favorable outcome was defined by mRS 0–2.

Figure 1:

Demonstration of the Qureshi grading scheme for collateral patterns found in basilar artery stenosis and occlusion.1 MCA middle cerebral artery; ICA internal carotid artery; PCA posterior cerebral artery; PCOM posterior communicating artery; SCA superior cerebellar artery; BA basilar artery; AICA anterior inferior cerebellar artery; PICA posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

All data were descriptively presented using means (±standard deviation) for continuous data and frequencies for categorical data. We identified demographic and clinical factors associated with the various collateral grades. We also report the frequency of favorable outcome in groups defined by patterns of collaterals.

Results

A total of 24 patients were included in the analysis mean age 67 ± 9.6. The collaterals were categorized as: Grade I A (n = 8), Grade IIIA (n = 5), and none (n = 11). No patients had Grade II collaterals (see Table 1). The mean age of patients with collaterals—grade IA, IIIA and without collaterals was 63.7, 66.4 and 69.6 years, respectively. The proportion of patients aged ≥65 years was 25%, 60%, and 54% in patients with Grade IA, Grade IIIA, and no collaterals, respectively. The proportion of women was higher in patients without collaterals. The proportions of diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia were higher in patients without collaterals. The proportion of patients with NIHSS score ≥10 was higher in patients with grade IIIA collaterals compared with patients without collaterals. The rate of good outcomes (mRS 0–2) at discharge was significantly higher among patients with IA collaterals compared with patients with grade IIIA collaterals (62% vs. 20%). The rate of good outcomes was 54% of patients without collaterals.

Table 1.

The characteristics of 24 patients of basilar artery stenosis or occlusion with (n = 13) or without (n = 11) collaterals

| Overall number (%) | Collaterals (n = 13) | Without collaterals (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Grade Age mean (95% CI) |

IA (n = 8) | IIIA (n = 5) | |

| 63.7(57.8 –69.6) | 66.4 (52.8 – 80) | 69.6(62.3 – 76.8) | |

| 45–64 years | 6(75) | 2(40) | 5(45.4) |

| >65 years | 2(25) | 3(60) | 6(54.5) |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 7(87.5) | 3(60) | 2(18.1) |

| Women | 1(12.5) | 2(40) | 9(81.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 5(62.5) | 3(60) | 7(63.6) |

| African-Americans | 3(37.5) | 2(40) | 0(0) |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 5(62.5) | 4(80) | 10(91) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0(0) | 1(20) | 8 (72.7) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1(12.5) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| History of stroke/TIA | 3(37.5) | 2(40) | 5(45.4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 2(25) | 0(0) | 3(27.2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 5(62.5) | 3(60) | 10(91) |

| Cigarette smoking | 2(25) | 1(20) | 4(36.3) |

| Admission NIHSS score | |||

| NIHSS admission ≤ 10 | 7(87.5) | 3(60) | 10(91) |

| NIHSS score admission ≥ 10 | 1(12.5) | 2(40) | 1(9) |

| Discharge NIHSS score | |||

| NIHSS score ≤ 10 | 6(75) | 2(40) | 7(63.6) |

| NIHSS score ≥ 10 | 2(25) | 3(60) | 4(36.3) |

| tPA | |||

| IV-tPA | 1(12.5) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Endovascular treatment | 3(37.5) | 2(40) | 3(27.2) |

| In hospital complication | |||

| ICH | 0(0) | 2(40) | 2(18.1) |

| ICH symptomatic | 0(0) | 2(40) | 2(18.1) |

| In hospital mortality | 2(25) | 3(60) | 3(27.2) |

| Basilar artery status | |||

| Stenosis | 0(0) | 2(40) | 8 (72.7) |

| Occlusion | 8(100) | 3(60) | 3(27.2) |

| Outcome | |||

| Favorable(mRS ≤ 2) | 5(62.5) | 1(20) | 5(45.4) |

| Unfavorable(mRS ≥ 3) | 3(37.5) | 4(80) | 6(54.5) |

Discussion

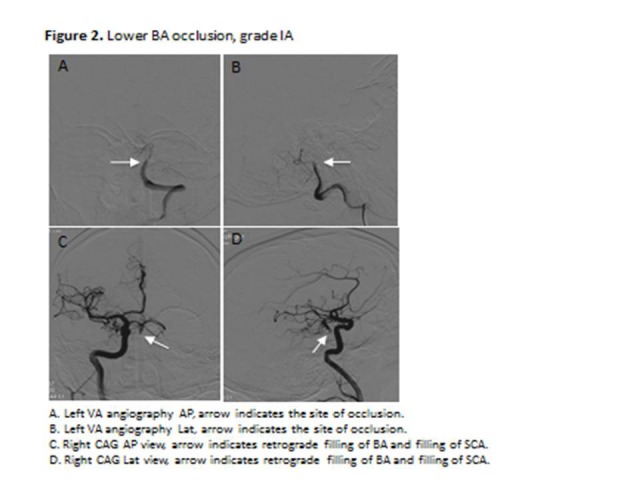

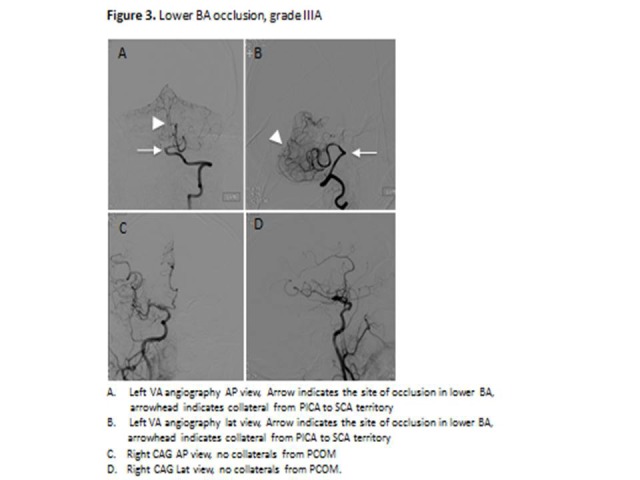

A new grading scheme was proposed to categorize collateral circulation in patients with basilar artery occlusion or stenosis by Qureshi [1]. We applied this grading to the individual patient diagnosed as ischemic stroke associated with basilar artery occlusion or stenosis. We found the following categories in the 24 patients: Grade I (n = 8); Grade II (n = 0); Grade III (n = 5), Grade IV (n = 0), and no collaterals (n = 11) (see Figure 2). Although we included a relatively small number of the patients and there was no statistical significance, some noteworthy findings were obtained through this study. The presence of Grade I (IA) collaterals appeared to be associated with better clinical outcomes defined by NIHSS score and mRS at discharge. This could be due to the fact that grade IA reflects the presence of better collaterals (see Figure 2). The presence of Grade III (IIIA) collaterals (see Figure 3) appeared to be associated with a higher NIHSS score at admission and discharge. Patients without collaterals were predominantly those with BAS (72%) and women (81.9%). As expected, these patients had lower NIHSS score at admission than other groups. However, the rate of favorable outcome at discharge appeared to be worse than those with Grade I collaterals. There was no presence of ICH observed in patients with Grade I (IA) collaterals. Conversely, ICH was observed in 40% of the patients with Grade III (IIIA) collaterals.

Presence of collateral circulation within the setting of BAO has been described in studies dated as far back as 1970s. Moscow and Newton reported nine cases of BAO. Patients in the study were shown to have collateral flow either through PCA or pial anastamoses from the MCA to the PCA [15, 16]. Subsequently, Archer and Horenstein [15] further explored the theory of collaterals supplying the cerebellum in 20 patients with BAO and 3 patients with bilateral vertebral artery occlusions. In the 1990s, a study by Cross et al [17] of 20 patients demonstrated that in symptomatic acute basilar artery thrombosis, neurologic outcome was better after intraarterial thrombolysis in patients who had collateral filling of the basilar artery, except in cases of proximal basilar thrombosis. Patients with collateral filling of the basilar artery also tolerated longer ischemic symptom duration [17]. Therefore, in this study we set out to evaluate the importance of collaterals in determining prognosis and presence of adverse events in the setting of BAS and BAO. Several studies [18–21] have defined collaterals based on the presence of antero- or retrograde filling of basilar artery. However, collaterals that form over the surface of cerebellum are not accounted in such categorization. In our analysis, the presence of Grade III (IIIA) collaterals appeared to have high NIHSS scores at admission and ICH was observed in 40% of these patients with Grade III (IIIA) collaterals. Such findings support categorization of collateral patterns to better stratify patients.

The present results must be interpreted considering the intrinsic limitations. In addition to the retrospective nature, the number of patients was relatively small and the analysis is exploratory. The current data supports stratifying patients with BAO or BAS based on patterns of collateral supply. Further data is required to determine the incorporation of such angiographic findings into clinical decision making.

Figure 2:

Lower BA occlusion, grade IA

Figure 3:

Lower BA occlusion, grade IIIA demonstrate angiographic images of IA collaterals and IIIA collaterals, which were the predominant type of collaterals found in the patient population examined with basilar artery stenosis and occlusion. VA vertebral artery; BA basilar artery; PICA posterior inferior cerebellar artery; SCA superior cerebellar artery; PCOM posterior communicating artery.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Qureshi has received funding from National Institutes of Health RO-1-NS44976-01A2 (medication provided by ESP Pharma) and 1U01NS062091-01A2, American Heart Association Established Investigator Award 0840053N, and Minnesota Medical Foundation, Minneapolis, MN.

References

- 1.Qureshi AI. A new method to classify the collateral patterns in the posterior circulation. J Neuroimaging. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith WS. Intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for acute basilar occlusion. Stroke. 2007;38:701–3. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000247897.33267.42. Pro. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubik CS, Adams RD. Occlusion of the basilar artery: a clinical and pathological study. Brain. 1946;69:73–121. doi: 10.1093/brain/69.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castaigne P, Lhermitte F, Gautier JC, Escourolle R, Derouesne C, Der Agopian P, Popa C. Arterial occlusions in the vertebro-basilar system. A study of 44 patients with post-mortem data. Brain. 1973;96(1):133–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/96.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulte-Altedorneburg G, Reith W, Bruckmann H, Dichgans M, Mayer TE. Thrombolysis of basilar artery occlusion--intra-arterial or intravenous: is there really no difference? Stroke. 2007;38(1):9, 10–11. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251686.28701.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis SM, Donnan GA. Basilar artery thrombosis: recanalization is the key. Stroke. 2006;37(9):2440. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000237069.89438.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prognosis of patients with symptomatic vertebral or basilar artery stenosis. The warfarin-aspirin symptomatic intracranial disease (wasid) study group. Stroke. 1998;29(7):1389–92. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.7.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi AI. New grading system for angiographic evaluation of arterial occlusions and recanalization response to intra-arterial thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(6):1405–14. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200206000-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammad YM, Christoforidis GA, Bourekas EC, Slivka AP. Qureshi grading scheme predicts subsequent volume of brain infarction following intra-arterial thrombolysis in patients with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke. J Neuroimaging. 2008;18(3):262–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammad Y, Xavier AR, Christoforidis G, Bourekas E, Slivka A. Qureshi grading scheme for angiographic occlusions strongly correlates with the initial severity and in-hospital outcome of acute ischemic stroke. J Neuroimaging. 2004;14(3):235–41. doi: 10.1177/1051228404265716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalela JA, Dunn B, Todd JW, Warach S. Induced hypertension improves cerebral blood flow in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2005;64(11):1979. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156360.70336.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marzan AS, Hungerbuhler HJ, Studer A, Baumgartner RW, Georgiadis D. Feasibility and safety of norepinephrine-induced arterial hypertension in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2004;62(7):1193–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118303.45735.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smrcka M, Ogilvy CS, Crow RJ, Maynard KI, Kawamata T, Ames A., 3rd Induced hypertension improves regional blood flow and protects against infarction during focal ischemia: time course of changes in blood flow measured by laser doppler imaging. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(3):617–24. 624–5. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199803000-00032. discussion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noor R, Wang CX, Todd K, Elliott C, Wahr J, Shuaib A. Partial intra-aortic occlusion improves perfusion deficits and infarct size following focal cerebral ischemia. J Neuroimaging. 2010;20(3):272–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2009.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archer CR, Horenstein S. Basilar artery occlusion: clinical and radiological correlation. Stroke. 1977;8(3):383–90. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moscow NP, Newton TH. Angiographic implications in diagnosis and prognosis of basilar artery occlusion. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119(3):597–604. doi: 10.2214/ajr.119.3.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross DT, 3rd, Moran CJ, Akins PT, Angtuaco EE, Derdeyn CP, Diringer MN. Collateral circulation and outcome after basilar artery thrombolysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(8):1557–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schonewille WJ, Wijman CA, Michel P, Rueckert CM, Weimar C, Mattle HP, Engelter ST, Tanne D, Muir KW, Molina CA, Thijs V, Audebert H, Pfefferkorn T, Szabo K, Lindsberg PJ, de Freitas G, Kappelle LJ, Algra A. Treatment and outcomes of acute basilar artery occlusion in the basilar artery international cooperation study (basics): a prospective registry study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(8):724–30. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfefferkorn T, Mayer TE, Opherk C, Peters N, Straube A, Pfister HW, Holtmannspotter M, Muller-Schunk S, Wiesmann M, Dichgans M. Staged escalation therapy in acute basilar artery occlusion: intravenous thrombolysis and on-demand consecutive endovascular mechanical thrombectomy: preliminary experience in 16 patients. Stroke. 2008;39(5):1496–1500. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy EI, Firlik AD, Wisniewski S, Rubin G, Jungreis CA, Wechsler LR, Yonas H. Factors affecting survival rates for acute vertebrobasilar artery occlusions treated with intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy: a meta-analytical approach. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(5):539–45. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199909000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandt T, von Kummer R, Muller-Kuppers M, Hacke W. Thrombolytic therapy of acute basilar artery occlusion. Variables affecting recanalization and outcome. Stroke. 1996;27(5):875–81. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.5.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]