Abstract

Background: Hyperglycemia is common and hard to control in surgical patients with diabetes. We retrospectively investigated short-term effects of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) in perioperative patients with diabetes.

Patients and Methods: Perioperative patients with diabetes discharged between January 1, 2006 and January 1, 2012 were included. Glucose control and postoperative outcomes were compared between the patients using CSII or non-CSII insulin therapy.

Results: We identified 108 pairs of patients matched by propensity and surgical category who were using CSII therapy (CSII group) or non-CSII insulin therapy (control group). The CSII group had significantly lower fasting glucose levels (on the first postoperative day, 9.06±3.09 mmol/L vs. 11.05±4.19 mmol/L; P=0.003) and lower mean glucose levels (on the operation day, 9.93±2.65 mmol/L vs. 12.05±3.86 mmol/L; P=0.001). The CSII group also had a lower incidence of fever (on the first postoperative day, 30.4% vs. 53.2%; P=0.005). Furthermore, patients in the CSII group experienced significantly shorter postoperative intervals for suture removal (P=0.02) and hospital discharge (P=0.03). No significant difference in the total medical expenditure was observed between the two groups (P=0.47). We also made a comparison between the 30 pairs of patients who were using CSII or multiple daily insulin injection therapy but observed no significant difference between these two therapies in glucose control or postoperative outcomes.

Conclusions: Compared with non-CSII insulin therapy, even short-term implementation of CSII can improve the postoperative control of glucose, reduce the incidence of postoperative fever, and shorten the time for suture removal and discharge in surgical patients with diabetes.

Introduction

Hyperglycemia is common in surgical patients and may become even worse and harder to control in those with diabetes.1 Perioperative factors such as anesthesia, metabolic stress, and critical illness may lead to insulin resistance, decreased insulin secretion, and impaired glucose metabolism, which contribute to hyperglycemia.2 Perioperative hyperglycemia has long been identified as a risk factor for postoperative morbidity and mortality.2 A series of studies has shown that poor perioperative glycemic control is associated with poor hospital outcomes,3,4 whereas tight control is associated with decreased infection rates and improved survival.2 Van den Berghe et al.5 reported that intensive insulin therapy (IIT) could significantly reduce overall in-hospital mortality and morbidity in surgical intensive care unit (ICU) patients compared with conventional treatment. However, recently, there has been controversy over the safety and benefits of IIT, as shown by studies suggesting that IIT does not reduce perioperative death or morbidity but leads to increasing hypoglycemia instead.6,7

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) via an insulin pump was first introduced in the 1970s as an approach to achieve normal glucose in patients with type 1 diabetes8 and is now a widely used form of IIT. Multiple daily injection (MDI) of insulin is another common form of IIT, but in patients with type 1 diabetes, CSII provides better glycemic control and stability without a higher rate of hypoglycemia.9–13 However, most studies for CSII were conducted in patients with type 1 diabetes who received long-term CSII therapy, and very few studies were focused on perioperative short-term application of CSII in different types of diabetes patients.

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all surgical patients with diabetes in our hospital between January 1, 2006 and January 1, 2012 and compared the patients using CSII therapy or non-CSII insulin therapy, in order to provide further evidence on the efficacy and safety of CSII in this context.

Patients and Methods

Data sources

All the data came from the existing medical records related to the hospitalization for surgery in Tongji Hospital (a tertiary teaching hospital affiliated with Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China). We collected detailed information on demographic characteristics, previous medical history, interventions, laboratory results, and hospital outcomes using data abstraction forms.14

Study cohort

Patients hospitalized in surgical department with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of diabetes (using the following International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification Codes: E14.901, E10.900, E10.901, E11.900, and E11.902) between January 1, 2006 and January 1, 2012 were identified (n=2,088) (Fig. 1). We abstracted 1,850 available medical records, reviewed each in detail, and excluded 803 patients who underwent no surgery during hospitalization. The 277 patients for whom glucose values were unavailable (defined as those who had no morning fasting glucose measurements within 1 day after admission or whose average number of capillary glucose measurements during the perioperative days was less than two times per day) were also excluded. Perioperative days in this study were defined as the period from 2 days before the surgery to the end of Day 5 after the surgery. This provided the study with a population consisting of 329 patients who received CSII therapy (CSII group) and 441 patients who did not receive CSII therapy (control group) during the hospitalization. We then excluded 48 patients who received less than 4 days of CSII therapy from the CSII group and 185 patients who received less than one insulin injection per day during the perioperative days from the control group. This led to a study population of 537 qualified subjects, with 281 patients in the CSII group and 256 patients in the control group. The patients in the control group received MDI (three or more injections of insulin per day) or conventional insulin therapy. The glucose levels of both groups were monitored by nurses, and insulin doses were adjusted under the supervision of endocrinologists. The target glucose levels were generally 7–10 mmol/L with slight variations according to the condition of each patient.

FIG. 1.

Study cohort. CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion.

Blood glucose management and data collection

In our hospital, fasting plasma glucose is routinely measured when a patient is admitted. If a perioperative patient has diabetes, a consultation of an endocrinologist will be arranged. The endocrinologist will set up a management plan for glucose control (including the target of glucose levels) for the patient during the hospitalization (including perioperation). If the patient receives the insulin therapy (including CSII), regular inspections will be provided twice per day by a nurse from the Department of Endocrinology. The inspection is usually arranged around 8 a.m.–10 a.m. and 3 p.m.–5 p.m. The nurse will confirm whether the insulin pumps work well and at the meantime record the glucose measurements and modify the insulin regimen for those patients according to the advice from an endocrinologist. Actually, most of the perioperative patients with diabetes who received short-term CSII therapy usually use an insulin pump provided by our hospital during his or her hospitalization.

In the present study, for the patients who had their normal diet, glucose measurements were collected at eight time points daily if available (preprandial and 2 h postprandial for each meal, before bedtime, and 5 h after bedtime15). For the patients who were fasting or who could only have an irregular liquid diet, glucose measurements were collected at or within 1 h of the following eight time points if available: 1 a.m., 4 a.m., 7 a.m., 10 a.m., 1 p.m., 4 p.m., 7 p.m., and 10 p.m. If two measurements were spaced less than 2 h apart, the second measurement was ignored. Because some patients in the CSII group did not receive CSII therapy for all perioperative days, for those patients who did not receive CSII therapy on some given day, the glucose measurements and those of corresponding matched patients in the control group on that day were excluded from further analysis.

Evaluation of preoperative status in patients: preoperative risk score

The preoperative risk scoring system adopted by our hospital was estimated by anesthesiologists according to variables including age, blood pressure, cardiac function, electrocardiogram, myocardial infarction history, respiratory function, liver function, renal function, electrolyte concentrations, body temperature, hemoglobin concentration, coagulation function, endocrine status, emergency of surgery, operative severity, and predicted duration of surgery.

Statistical analysis

To account for potential confounding variables, we divided the 537 patients into different groups according to the type of the surgeries, and matched-pair analysis was performed within each group based on the propensity score for receiving CSII therapy on the variables of age, gender, preoperative risk score, and baseline fasting glucose. Those groups with too small a sample size to conduct a propensity match were excluded from further analysis. If not specifically noted, differences in continuous variables between the CSII group and the control group were assessed for statistical significance by paired t tests if the differences were normally distributed and by paired Wilcoxon rank sum tests if the differences were not normally distributed. Differences in categorical variables were assessed for statistical significance by paired χ2 tests. To evaluate the fluctuation of blood glucose for the control and CSII groups during postoperative period, we defined a variable “glucose fluctuation index,” which was calculated as the SD of all the glucose measurements of each individual subject from both groups on postoperative Days 0, 1 and 2 (i.e., with a maximum of 19 points of glucose measurements: three measurements at 4 p.m., 7 p.m., and 10 p.m. for postoperative day 0 and a total of 16 measurements for postoperative Days 1 and 2). To evaluate some of the short-term outcomes with censored data, Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed. Significance was defined as a two-tailed P value of≤0.05. All analyses were performed with STATA version 11.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline characteristics

After the propensity match, we acquired 108 matched pairs of patients from the CSII group and the control group. Baseline characteristics of the 216 patients are detailed in Table 1. The matching procedure created two groups that were not significantly different with respect to all listed baseline variables. Both groups were mainly middle-aged or elderly patients, of which 60% were male, with a diabetes duration of about 6 years (0–25 years). About 30% of the patients had comorbidities, among which hypertension was the most common. Preoperative laboratory tests of both group were similar and generally within the normal range.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Pairs (n)a | CSII group | Control group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

108 |

58.8±11.0 |

59.4±9.6 |

0.42 |

| Male [n (%)] |

108 |

60 (55.6) |

60 (55.6) |

1.00 |

| Body weight (kg) |

83 |

67.2±14.0 |

66.0±10.9 |

0.52 |

| Smoking [n (%)] |

105 |

38 (36.2) |

38 (36.2) |

1.00 |

| Alcohol [n (%)] |

105 |

22 (21.0) |

26 (24.8) |

0.61 |

| Diabetes mellitus duration (years) |

49 |

6.2±5.4 |

6.4±6.5 |

0.87 |

| FBG (mmol/L) |

108 |

9.20±3.16 |

8.79±3.18 |

0.09 |

| Preoperative risk score |

108 |

9.5±4.4 |

9.5±4.3 |

0.88 |

| Preoperative comorbidity [n (%)] | ||||

| Hypertension |

108 |

18 (16.7) |

22 (20.4) |

0.57 |

| Coronary artery disease |

108 |

5 (4.6) |

4 (3.7) |

|

| Pulmonary disease |

108 |

6 (5.5) |

6 (5.5) |

|

| Abnormal renal function |

108 |

0 (0) |

1 (0.9) |

|

| Abnormal liver function |

108 |

4 (3.7) |

3 (2.8) |

|

| Preoperative laboratory values | ||||

| Hematocrit (%) |

103 |

36.8±6.2 |

36.1±6.8 |

0.38 |

| WBC (×109/L) |

103 |

6.7±3.1 |

7.3±4.0 |

0.21 |

| Neutrophil/WBC (%) |

102 |

62.0±11.0 |

64.3±13.0 |

0.15 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) |

98 |

64.2±29.0 |

65.3±23.4 |

0.76 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 98 | 39.1±4.7 | 39.0±6.2 | 0.89 |

Data are mean±SD values or n (%) as indicated.

Pairs represent the number of the matched pairs of patients that were available for analysis.

FBG, fasting blood glucose; WBC, white blood cell.

The surgical types are described in Table 2. Because there were 27.8% (n=30) of patients receiving MDI therapy and 72.2% (n=78) of patients receiving conventional insulin therapy in the control group during the perioperative days, we defined the insulin regimen for the control group as non-CSII insulin therapy. For further analysis, we abstracted the data of the 30 patients who received MDI therapy (MDI group, n=30) and their matched patients in the CSII group (n=30) and made a direct comparison between the CSII and MDI groups with the same method. The baseline characters of the 30 pairs of patients are similar to the whole study population, and there was no significant difference between the CSII and MDI groups in most baseline variables except that the MDI group had a slightly higher neutrophil/white blood cell (WBC) percentage ratio than the CSII group (MDI vs. CSII, 66.4±11.5% vs. 60.5±9.8%; P=0.03).

Table 2.

Surgical Procedures

| Type of surgeries | Pairs (n) |

|---|---|

| Abdominal surgery (n=48) (44.4%) | |

| Biliary surgery other than cholecystectomy |

10 |

| Distal or total gastrectomy |

7 |

| Cholecystectomy, laparoscopic |

7 |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy |

5 |

| Colectomy |

5 |

| Hepatic resection |

4 |

| Splenectomy |

3 |

| Proximal gastrectomy |

3 |

| Rectal cancer resection |

3 |

| Orthotopic liver transplantation |

1 |

| Urology (n=22) (20.4%) | |

| Transurethral resection of the prostatea |

7 |

| Transurethral lithotripsya |

6 |

| PCNL |

3 |

| Adrenal tumor resection |

3 |

| Radical nephrectomy |

3 |

| Neurosurgery (n=13) (12.0%) | |

| Laminectomy/laminotomy |

11 |

| Intracranial surgery |

2 |

| Orthopedics (n=9) (8.3%) | |

| Limb operation |

5 |

| Hip arthroplasty |

4 |

| Cardiothoracic (n=9) (8.3%) | |

| CABG |

6 |

| Pulmonary lobectomy |

3 |

| Breast and thyroid surgery (n=7) (6.5%) | |

| Radical mastectomy |

4 |

| Subtotal thyroidectomy |

3 |

| Total | 108 |

The patients underwent these two types of surgeries were excluded from the analysis of the “suture removal” in Table 3.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCNL, percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

In our study, 90% of patients had type 2 diabetes, and 10% of patients had type 1 diabetes or diabetes of uncertain type. Because oral glucose tolerance tests and hemoglobin A1c tests were performed in very few patients, these data were not included in Table 1.

Perioperative glycemic control

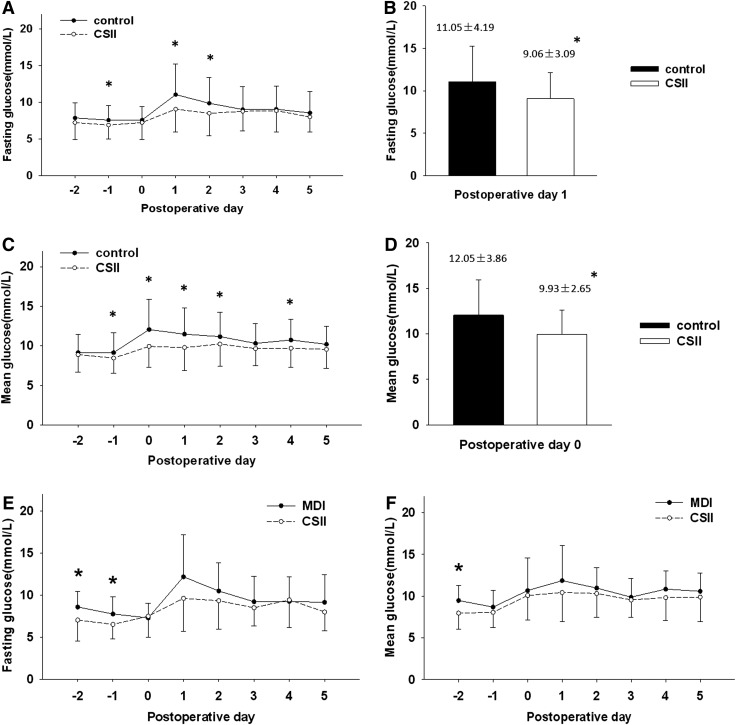

During the perioperative days, the average number of glucose measurements per patient was 4.3/day in the CSII group and 3.5/day in the control group. Compared with the control group, the CSII group had significantly lower mean and fasting glucose levels on the first and second postoperative days (P<0.05 for all; Fig. 2A–D). The blood glucose levels in the CSII group were more stable than those in the control group during the early postoperative period, as indicated by the lower glucose fluctuation index (CSII vs. control, 2.35±1.05 mmol/L vs. 2.94±1.57 mmol/L; P=0.01).

FIG. 2.

Fasting and mean glucose levels in perioperative patients who received insulin therapy. (A and C) The glucose level of the continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) group is presented as the mean (○) with the negative side of SD; the glucose level of the control group is presented as the mean (●) with the positive side of SD. Postoperative Day 0 represents the operation day. *P≤0.05 for comparison of the CSII group versus the control group. (A) Fasting glucose represents the morning fasting glucose measured before breakfast or at around 7 a.m. for patients who could not have normal meals. (C) Mean glucose was defined as the average of all glucose measurements of each patient on a single day. Mean glucose on the operation day is defined as the average of the glucose measurements at the time points of 4 p.m., 7 p.m., and 10 p.m. The CSII group had (B) significantly lower fasting glucose levels on the morning of the first postoperative day and (D) significantly lower mean glucose levels during the evening of the operation day. (E and F) The glucose level of the CSII group is presented as the mean (○) with the negative side of SD; the glucose level of the multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin group is presented as the mean (●) with the positive side of SD. Postoperative day 0 represents the operation day. *P≤0.05 for comparison of the CSII group versus the MDI group.

During the perioperative days, hypoglycemia (defined as a glucose level of ≤3.3 mmol/L16) occurred in six patients in the CSII group and in nine patients in the control group, whereas severe hypoglycemia (defined as a glucose level of ≤2.2 mmol/L5) occurred in no patient in the CSII group and in three patients in the control group. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups.

CSII and MDI had a similar effect on blood glucose in perioperative patients because there was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to mean and fasting blood glucose levels (Fig. 2E and F), although the overall trend of the glucose levels seemed to be lower and more stable in the CSII group.

Postoperative fever status

In this study, we defined a patient with a maximum body temperature in a single day over 37.3°C as having fever on that day. We included patients in the CSII group who had started their CSII therapy before the operation and continued at least until postoperative Day 3 (n=29). Finally, we included 79 patients from the CSII group and the 79 matched patients from the control group in the analysis of postoperative fever incidence. Generally speaking, the proportion of patients with fever in both groups gradually increased after the operation, reaching the maximum during the first postoperative day and then gradually decreasing (Fig. 3A). The CSII group had a lower incidence of fever than the control group after the operation, especially on the first postoperative day (30.4% vs. 53.2%; P=0.005).

FIG. 3.

Fever status in perioperative patients who received insulin therapy: (A) continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) versus control and (B) CSII versus multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin. Day 0, the operation day. *P≤0.05 for comparison.

In the same manner, we included 23 pairs of patients from the CSII and MDI groups in the analysis of postoperative fever incidence. The results showed no significant difference between the CSII and MDI groups in the incidence of fever (Fig. 3B); however, the general trend of both groups was similar to that in Figure 3A.

Other postoperative outcomes

Table 3 shows comparison of postoperative short-term outcomes between the CSII and control groups for other than fever status. The results showed that both groups had some patients who did not have sutures removed before discharge, and we defined the discharge time of these patients as the end of observation, marked their information as censored data, and performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis on the data of the 95 pairs of patients. The results showed that the patients in the CSII group had their sutures removed in a significantly shorter period of time (14.0 days vs.16.0 days; P=0.02). Furthermore, the CSII group also experienced a significantly shorter postoperative hospital stay (12.7 days vs. 14.4 days; P=0.03).

Table 3.

Postoperative Outcomes

| Pairs (n) | CSII | Control | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suture removala |

95 |

54 (50.0) |

47 (43.5) |

0.34 |

| Days to suture removal (days)b |

95 |

14.0 (13.1, 14.9) |

16.0 (13.8, 18.2) |

0.02 |

| Days to drainage tube removalcd |

58 |

6.0 (3.0, 8.0) |

5.0 (2.0, 8.0) |

0.76 |

| Postoperative drainage volume (mL)c |

43 |

600 (200, 1,150) |

510 (200, 2,180) |

0.52 |

| ICUe |

108 |

9 (8.3) |

11 (10.2) |

0.77 |

| Mechanical ventilationf |

108 |

13 (12.0) |

10 (9.3) |

0.45 |

| Postoperative infection | ||||

| Cultures positive |

108 |

4 (3.7) |

2 (1.9) |

|

| Urinary tract infection |

108 |

2 (1.9) |

3 (2.8) |

|

| Pneumonia |

108 |

2 (1.9) |

1 (0.9) |

|

| Postoperative Day 3 | ||||

| WBCs (×109/L) |

48 |

10.6±3.8 |

10.0±4.3 |

0.35 |

| Neutrophils/WBCs (%) |

48 |

77.2±9.8 |

74.9±11.2 |

0.25 |

| Postoperative duration of antibiotics use (days) |

102 |

12.3±7.1 |

12.5±6.7 |

0.61 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) |

108 |

12.7±5.3 |

14.4±7.5 |

0.03 |

| Total hospital stay (days) |

108 |

21.2±7.5 |

22.3±8.7 |

0.22 |

| Total medical expenditure (CNY)cg | 80 | 51,547 (27,459, 66,912) | 48,106 (23,500, 68,800) | 0.42 |

Values are n (%) or mean±SD values unless indicated otherwise.

Number of patients who had their suture removed before discharge.

Median (95% confidence interval) for both groups acquired by Kaplan–Meier analysis with censored data included. Twenty-six patients who underwent transurethral surgery (noted in Table 2) did not need suture removal and were excluded from the analysis of suture removal.

Median (25th, 75th percentile).

Thirty-nine patients in the continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) group and 36 patients in the control group did not experience drainage tube placement, so only 58 pairs of patients were included in the analysis of drainage tube removal.

ICU represents the number of patients who once stayed in the intensive care unit (ICU) after the operation.

Mechanical ventilation represents the number of patients who once received mechanical ventilation after the operation.

1 USD($) equals approximately 6.8 CNY(¥) in 2010.

WBC, white blood cell.

There was no significant difference between the CSII and control groups in the days to drainage tube removal and the postoperative drainage volume. Patients who stayed in the ICU or received mechanical ventilation were also similar between the two groups. The blood WBC and neutrophil/WBC counts on the third postoperative day showed no significant difference, and the length of postoperative antibiotic use was also similar between the two groups. However, it was difficult to compare the incidence of postoperative infection directly because of the very few cases in both groups. In addition, we did not observe a significant difference in the total medical expenditure between the two groups (P=0.47). Both groups had no death during the hospitalization, but this study was not powerful enough to estimate mortality.

Similar results were obtained as above for the comparison between the CSII and MDI group, except that no significant difference was found in suture removal (CSII vs. MDI, 14.0 days vs. 14.0 days; P=0.74) and postoperative hospital stay (14.6 days vs. 16.5 days; P=0.26).

Discussion

A series of studies has shown that long-term use of CSII in patients with type 1 diabetes provides better control of glucose, indicated by lower levels of blood glucose and HbA1c, and less glucose fluctuation without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia, compared with MDI.9–13,15 However, relatively fewer studies were conducted in patients with type 2 diabetes, and the studies in type 2 diabetes patients generally showed no significant difference between CSII and MDI with respect to HbA1c and risk of hypoglycemia.17–20 Recently, growing attention has been paid to the hyperglycemia control in perioperative patients with diabetes, and experience is gradually being accumulated in this regard.21–26 In our hospital, CSII had been successfully applied to perioperative patients with diabetes for several years, and the management policy is similar to the guidelines published recently.23 Our results show that there were lower levels and less fluctuation of glucose in the patients of the CSII group. In addition, no significant difference was observed between the CSII and control groups for occurrence of hypoglycemia, which is similar to other studies.17,18 However, probably because of the reduced sample size, blood glucose levels between the CSII and MDI groups showed no significant difference.

For the postoperative outcomes, there is abundant evidence to support the association between perioperative hyperglycemia and poor outcomes,4 most of which comes from retrospective or prospective observational studies conducted in ICU patients or patients undergoing cardiac surgeries.5,27,28 However, there is no unified definition of perioperative “hyperglycemia” at present, and how tight the glucose control should be is still a controversial problem. Although the study by van den Berghe et al.5 provided strong evidence for the benefits of IIT, the results could not be extrapolated to patients who were not in the surgical ICU. In our study, the difference in glucose control between the CSII and control groups were not as significant as the difference between the intensive and conventional insulin treatments in the study of van den Berghe et al.5 However, considering that both the CSII and control groups in our study had the same glucose target of about 7–10 mmol/L, this difference was still striking. Furthermore, although the CSII group in our study did not show an exciting advantage over the control group in mortality and morbidity as the study of van den Berghe et al.5 did, we still observed some advantages of CSII therapy such as fewer postoperative days to suture removal and discharge. Although there was a significant lower incidence of fever in the CSII group, the blood WBC and neutrophil/WBC counts between the two groups were similar on the third postoperative day. Therefore, we speculate that the lower incidence of fever in the CSII group may not be attributed to reduced infection, but to better tissue repairing and a lower level of inflammatory factors in the CSII group, as insulin delivery by CSII more closely mimics physiological insulin secretion. Actually, the fewer postoperative days to suture removal and discharge in the CSII group provide us further evidence that the implementation of CSII might benefit the patients in better recovering from surgeries.

The relatively high cost of CSII is another prevalent concern,29–31 especially among those uninsured patients who have economic difficulties. Although the cost directly associated with glucose control was not obtainable from the medical records, it should be certainly higher in the CSII group because of the cost of insulin pump devices, the increased nursing and physician time, and the increased number of daily glucose measurements. However, we did not observe a significant increase in the total medical expenditure in the CSII group, which suggested that the implementation of CSII might lower patients' other medical expenditures. In addition, although we could not directly assess the life quality of the patients, the better control of postoperative glucose, the lower proportion of patients with fever, and the earlier removal of sutures in the CSII group suggested that the implementation of CSII might improve patients' postoperative life quality.

The strengths of this study were as follows: (1) The propensity match analysis greatly helped us reduce the baseline differences between the two groups and increase the power of the conclusion. (2) Few studies have been conducted in patients with diabetes undergoing noncardiac surgeries, and we are unaware of studies comparing the short-term effect of CSII with non-CSII insulin therapy in Asian patients undergoing different surgeries. Our study, for the first time, provided a general profile of the implementation of CSII in perioperative diabetes patients with an Asian background.

Limitations of this study should be noted. First, this is a retrospective study, and patients were not randomly assigned to treatment groups. Generally speaking, the patients in the CSII group had more difficulty in hyperglycemia control than the patients in the control group. Although we performed a propensity match between the two comparison groups to diminish the potential confounding, this bias cannot be completely eliminated because of some unmeasured confounders. Second, because the strategies we used to select the patients limited the sample size of this study and, additionally, this was a short-term study, we cannot investigate the long-term effect of CSII on the postoperative morbidity and mortality. Third, because this is a retrospective study, the insulin regimen in the control group was relatively variable, and we could not strictly define the insulin regimen for the control group (27.8% were treated with MDI, whereas 72.2% were treated with conventional insulin therapy); thus we could only generally define it as non-CSII insulin therapy. Finally, this study only focused on the short-term effect of CSII in perioperative patients within their hospitalization, and further evidence is still needed in exploring the long-term postoperative effect of CSII implementation in perioperative diabetes patients.

In conclusion, this study showed that even short-term implementation of CSII could improve the glucose management, reduce the incidence of postoperative fever, and shorten the postoperative days for suture removal and discharge. In addition, there was no significant difference between the CSII group and the control group in terms of hypoglycemia and the total medical expenditure of each patient.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all the staff in the Medical Records Department of our hospital who preserved and provided the medical records for this study. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Projects of Wuhan (grant 201060938360-04 from the Wuhan Science and Technology Bureau).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

D.M. contributed to the research design, data collection and statistical analysis, and the writing of the manuscript. C.C. and J.X. contributed to the data collection. Y.L., J.M., and P.Y. contributed to the statistical data analysis. Y.Y., S.S., Z.L., X.Z., and G.Y. contributed to the data interpretation and manuscript review. X.Y. contributed to the research design, data interpretation, and critical manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Krinsley J: Perioperative glucose control. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2006;19:111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipshutz AK, Gropper MA: Perioperative glycemic control: an evidence-based review. Anesthesiology 2009;110:408–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomposelli JJ, Baxter JK, 3rd, Babineau TJ, Pomfret EA, Driscoll DF, Forse RA, Bistrian BR: Early postoperative glucose control predicts nosocomial infection rate in diabetic patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1998;22:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhtar S, Barash PG, Inzucchi SE: Scientific principles and clinical implications of perioperative glucose regulation and control. Anesth Analg 2010;110:478–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R: Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1359–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirdemir P, Yildirim V, Kiris I, Gulmen S, Kuralay E, Ibrisim E, Ozal E: Does continuous insulin therapy reduce postoperative supraventricular tachycardia incidence after coronary artery bypass operations in diabetic patients? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2008;22:383–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi GY, Nuttall GA, Abel MD, Mullany CJ, Schaff HV, O'Brien PC, Johnson MG, Williams AR, Cutshall SM, Mundy LM, Rizza RA, McMahon MM: Intensive intraoperative insulin therapy versus conventional glucose management during cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:233–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickup JC, Keen H, Parsons JA, Alberti KG: Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: an approach to achieving normoglycaemia. BMJ 1978;1:204–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boland EA, Grey M, Oesterle A, Fredrickson L, Tamborlane WV: Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. A new way to lower risk of severe hypoglycemia, improve metabolic control, and enhance coping in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1779–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fatourechi MM, Kudva YC, Murad MH, Elamin MB, Tabini CC, Montori VM: Clinical review: hypoglycemia with intensive insulin therapy: a systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized trials of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion versus multiple daily injections. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:729–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeitler K, Horvath K, Berghold A, Gratzer TW, Neeser K, Pieber TR, Siebenhofer A: Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion versus multiple daily insulin injections in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2008;51:941–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanaire-Broutin H, Melki V, Bessieres-Lacombe S, Tauber JP: Comparison of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injection regimens using insulin lispro in type 1 diabetic patients on intensified treatment: a randomized study. The Study Group for the Development of Pump Therapy in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1232–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruttomesso D, Pianta A, Crazzolara D, Scaldaferri E, Lora L, Guarneri G, Mongillo A, Gennaro R, Miola M, Moretti M, Confortin L, Beltramello GP, Pais M, Baritussio A, Casiglia E, Tiengo A: Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) in the Veneto region: efficacy, acceptability and quality of life. Diabet Med 2002;19:628–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golden SH, Peart-Vigilance C, Kao WH, Brancati FL: Perioperative glycemic control and the risk of infectious complications in a cohort of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1408–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeVries JH, Snoek FJ, Kostense PJ, Masurel N, Heine RJ: A randomized trial of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and intensive injection therapy in type 1 diabetes for patients with long-standing poor glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2002;25:2074–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Goyal A, Krumholz HM, Masoudi FA, Xiao L, Spertus JA: Relationship between spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2009;301:1556–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman WH, Ilag LL, Johnson SL, Martin CL, Sinding J, Al Harthi A, Plunkett CD, LaPorte FB, Burke R, Brown MB, Halter JB, Raskin P: A clinical trial of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion versus multiple daily injections in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1568–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raskin P, Bode BW, Marks JB, Hirsch IB, Weinstein RL, McGill JB, Peterson GE, Mudaliar SR, Reinhardt RR: Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injection therapy are equally effective in type 2 diabetes: a randomized, parallel-group, 24-week study. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2598–2603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bode BW: Insulin pump use in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010;12(Suppl 1):S-17–S-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson SL, McEwen LN, Newton CA, Martin CL, Raskin P, Halter JB, Herman WH: The impact of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injections of insulin on glucose variability in older adults with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2011;25:211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vann MA: Perioperative management of ambulatory surgical patients with diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:718–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corney SM, Dukatz T, Rosenblatt S, Harrison B, Murray R, Sakharova A, Balasubramaniam M: Comparison of insulin pump therapy (continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion) to alternative methods for perioperative glycemic management in patients with planned postoperative admissions. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:1003–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyle ME, Seifert KM, Beer KA, Apsey HA, Nassar AA, Littman SD, Magallanez JM, Schlinkert RT, Stearns JD, Hovan MJ, Cook CB: Guidelines for application of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (insulin pump) therapy in the perioperative period. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:184–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyle ME, Seifert KM, Beer KA, Mackey P, Schlinkert RT, Stearns JD, Cook CB: Insulin pump therapy in the perioperative period: a review of care after implementation of institutional guidelines. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:1016–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Killen J, Tonks K, Greenfield JR, Story DA: New insulin analogues and perioperative care of patients with type 1 diabetes. Anaesth Intensive Care 2010;38:244–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stooksberry L: Perioperative management of people with diabetes using CSII therapy. J Diabetes Nurs 2012;16:70–76 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandhi GY, Nuttall GA, Abel MD, Mullany CJ, Schaff HV, Williams BA, Schrader LM, Rizza RA, McMahon MM: Intraoperative hyperglycemia and perioperative outcomes in cardiac surgery patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:862–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouattara A, Lecomte P, Le Manach Y, Landi M, Jacqueminet S, Platonov I, Bonnet N, Riou B, Coriat P: Poor intraoperative blood glucose control is associated with a worsened hospital outcome after cardiac surgery in diabetic patients. Anesthesiology 2005;103:687–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St Charles M, Lynch P, Graham C, Minshall ME: A cost-effectiveness analysis of continuous subcutaneous insulin injection versus multiple daily injections in type 1 diabetes patients: a third-party US payer perspective. Value Health 2009;12:674–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummins E, Royle P, Snaith A, Greene A, Robertson L, McIntyre L, Waugh N: Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion for diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:iii–iv, xi–xvi, 1–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynch PM, Riedel AA, Samant N, Fan Y, Peoples T, Levinson J, Lee SW: Resource utilization with insulin pump therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:892–896 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]