Abstract

Objectives: In Germany since 2007 children with advanced life-limiting diseases are eligible for Pediatric Palliative Home Care (PPHC), which is provided by newly established specialized PPHC teams. The objective of this study was to evaluate the acceptance and effectiveness of PPHC as perceived by the parents.

Methods: Parents of children treated by the PPHC team based at the Munich University Hospital were eligible for this prospective nonrandomized study. The main topics of the two surveys (before and after involvement of the PPHC team) were the assessment of symptom control and quality of life (QoL) in children; and the parents' satisfaction with care, burden of patient care (Häusliche Pflegeskala, home care scale, HPS), anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS), and QoL (Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness–Family Carer Version, QOLLTI-F).

Results: Of 43 families newly admitted to PPHC between April 2011 and June 2012, 40 were included in the study. The median interval between the first and second interview was 8.0 weeks. The involvement of the PPHC team led to a significant improvement of children's symptoms and QoL (P<0.001) as perceived by the parents; and the parents' own QoL and burden relief significantly increased (QOLLTI-F, P<0.001; 7-point change on a 10-point scale), while their psychological distress and burden significantly decreased (HADS, P<0.001; HPS, P<0.001).

Conclusions: The involvement of specialized PPHC appears to lead to a substantial improvement in QoL of children and their parents, as experienced by the parents, and to lower the burden of home care for the parents of severely ill children.

Introduction

Providing care for terminally ill and dying children is one of the most challenging situations in clinical medicine. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), pediatric palliative care (PPC) is focused on achieving the best possible quality of life (QoL) for patients and their families and requires a multidisciplinary approach, encompassing physical, emotional, social and spiritual domains.1–3 Based on this principle, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committees on Bioethics and Hospital Care recommended the development and broad availability of PPC services with child specific guidelines and standards.4

Over the past decade, these standards have increasingly been integrated into the care of children and adolescents with severe, advanced life-limiting diseases in Germany. Former research showed that the majority of caregivers preferred the children to be at home at the end of life.5–8 Since 2007, these patients are eligible for a specialized Pediatric Palliative Home Care (PPHC) service.9 However, little data is available on the effects of PPHC to date. The goal of this prospective study was to evaluate whether the involvement of a specialized PPHC team addresses the needs of patients and their families and thus leads to an increase in the acceptance and effectiveness of PPC as experienced by primary caregivers.

Methods

Study design

The prospective, nonrandomized study was conducted at the Coordination Center for Pediatric Palliative Care at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich. The center was implemented in 2004 to provide palliative home care for children, adolescents, and young adults with life-limiting diseases in southeastern Bavaria (population approx. 4.5 million). In 2009 a multiprofessional PPHC team consisting of three pediatricians, two nurses, a social worker and a chaplain, all with special training in palliative care, was established at the center. Main tasks of the team are provision of palliative medical and nursing care, including a 24/7 on-call service, as well as psychosocial support and coordination of professional assistance in cooperation with the local Health Care Professionals (HCPs). The main goal is to improve QoL in children and their families and thus enable them to live through the palliative and dying phase at home.

Participants

All primary caregivers of severely ill children receiving specialized palliative home care through the PPHC team in Munich for the first time between April 2011 and June 2012 were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria were caregivers' inadequate German language proficiency or intellectual ability to understand the questionnaire. Due to young age, mental impairment or poor condition, the additional assessment of the children by self-report as initially intended could only be accomplished in three children, thus these data were not evaluable.

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Munich University Hospital, and participants provided informed consent.

Questionnaires

To assess the acceptance and effectiveness of PPHC, two questionnaires for the children's primary caregivers (caregivers' questionnaire 1, CQ1, and caregivers' questionnaire 2, CQ2) were developed based on clinical practice and validated scales. The first assessment took place during the first week of involvement of the PPHC team. The second assessment was scheduled within the following six months and took place after consultation with the palliative medicine specialists according to the child's condition. The diversity of syndromes in children with life-limiting diseases and the resulting variable period of PPC necessitated taking into account the individual circumstances in this respect. In addition, palliative medicine specialists provided objective data concerning the child's functional status as Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score10 as well as their current medication at both assessment time points.

The CQ 1 comprised 71 items, 10 of which surveyed caregivers' sociodemographic data. For 18 items, numeric rating scales (NRS, 0–10) were used to assess the children's QoL, the caregivers' satisfaction with various aspects of the care (14 items), as well as the caregivers' adjustment before and after significant involvement of the PPHC team (four items). The caregivers' QoL was investigated using the Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness – Family Carer Version (QOLLTI-F, 19 items),11 and their anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, 14 items).12–14 The burden of care was measured by a short version of the Häusliche Pflegeskala (home care scale, HPS, 10 items).15–17 The CQ2 consisted of the same items without sociodemographic data (61 items). In addition, an open question regarding the caregivers' satisfaction with problem solving by the PPHC team was added.

Both questionnaires were completed in dialogue form at the families' home by a trained psychologist who was not part of the PPHC team. The original questionnaires are available from the authors upon request.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the demographic data, objective care data, and evaluation of care. The significances of the differences before and after involvement of the PPHC team were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonparametric data, as some of the variables were not normally distributed. For all analyses, Bonferroni adjustments were conducted. Significance level was set at P<0.05 for single comparisons and on the respective adjusted level for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Boxplots were used as a means of conveying graphically the magnitude of difference in pre/post responses and the extent of variability. The caregivers' answers on the single open question regarding their satisfaction with problem solving by the PPHC team were screened and categorized following the contents “medical care,” “psychosocial support” and “practical concerns.”

Results

Study participants

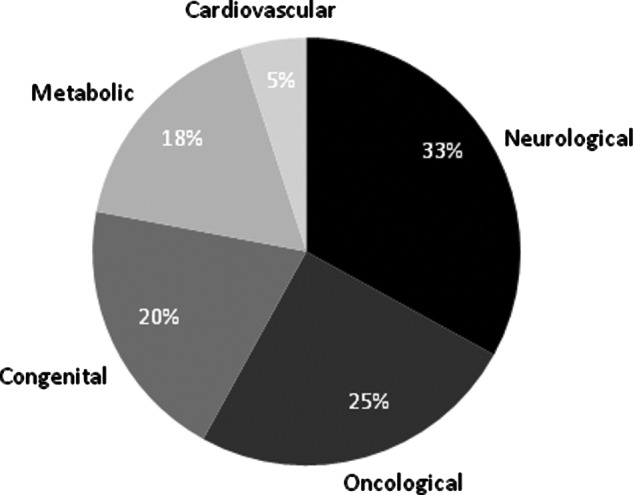

Between April 2011 and June 2012, a total of 43 children were treated by the PPHC team; 40 of the families were included in the study. Three (7%) families were excluded because of parental refusal. In the 40 remaining families (93%), sociodemographic data were collected and primary caregivers answered the questionnaires CQ1 and CQ2. Median age of the 40 children was 6.0 years (range=1 month to 18 years), 23 (57%) were male. The majority of patients were Christians (35; 88%); five of them were Muslims (12%). Fourteen patients had a migration background (35%). Non-malignant diseases were the predominant underlying conditions (30; 75%), one-third of which were neurologic diseases (see Figure 1). In 78% of the families, the patient had at least one sibling, 13% of whom were diagnosed with the same disorder. Eighteen (45%) of the patients died before the study ended, 16 (88%) of them at home. The median period of PPHC was 11.8 weeks (range=0.5–58.0 weeks). The interval between the first and the second assessment ranged from a few days to six months (median=8.0 weeks, interquartile range=10 weeks). None of the patients had an additional support service added to his or her care during PPHC involvement that was not a direct result of the PPHC team's work.

FIG. 1.

Underlying diseases by main categories (n = 40). As a result of rounding, the values sum to 101%.

Of the 40 participating caregivers, 38 were female (95%). In 37 families the questionnaires were completed by the mothers (92%), in two families by the fathers (5%), and in one case by the cousin of the patient. Their age ranged from 18 to 52 years, with a median of 39 years. Twenty-nine of the respondents were married (72%). As 78% of patients required care for 24 hours a day, the majority of caregivers (85%) were either unemployed, on leave of absence, or worked part-time at the time of the first assessment.

Since the questionnaires were completed in dialogue form by a trained psychologist and the assessment took place on-site in the familiar environment of the patients and caregivers, no missing data arose.

Assessment of care

After the involvement of specialized PPHC, caregivers' satisfaction with care and the quality of care significantly improved, as could be documented for 12 of 14 issues (NRS) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Caregivers' Satisfaction with the Quality of Care and Their Adjustment before and after Involvement of Specialized Pediatric Palliative Home Care

| |

|

Involvement of PPHC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment instrument | Before Median (IQR) | After Median (IQR) | n | p | |

| Burden relief for caregivers |

NRS |

2.0 (3) |

9.0 (3) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Psychological support |

NRS |

5.0 (3) |

8.5 (2) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Support for activities of daily living |

NRS |

4.0 (4) |

8.0 (3) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Communication with the child |

NRS |

7.0 (3) |

8.0 (3) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Communication with the general practitioner |

NRS |

8.0 (3) |

8.0 (3) |

40 |

n. s. |

| Communication with local HCPs |

NRS |

8.0 (2) |

9.0 (2) |

40 |

<0.050b |

| Quality of medical information |

NRS |

7.0 (2) |

10.0 (0) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Quality of medical care |

NRS |

6.0 (2) |

10.0 (0) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Quality of nursing information |

NRS |

7.0 (2) |

10.0 (0) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Quality of nursing care |

NRS |

7.0 (2) |

10.0 (0) |

40 |

<0.050b |

| Support in provision of care for the patient |

NRS |

5.0 (3) |

10.0 (0) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Clarification of important questions on the diagnosis and prognosis |

NRS |

5.0 (3) |

10.0 (0) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Support in socio-legal issues (e.g., entitlement to benefits) |

NRS |

2.0 (5) |

10.0 (2) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Spiritual care |

NRS |

6.5 (3) |

7.0 (2) |

40 |

n. s. |

| Subjective burden due to patients' disease |

NRS |

10.0 (2) |

7.0 (3) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Patients' QoL |

NRS |

2.5 (2) |

4.0 (4) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| Symptom control |

NRS |

5.0 (3) |

9.0 (2) |

40 |

<0.001a |

|

Caregivers' QoL |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

NRS |

3.0 (3) |

5.0 (4) |

40 |

<0.001a |

| |

QOLLTI-F total score |

5.8 (1) |

7.1 (1.3) |

40 |

<0.001 |

|

Caregivers' stress and burden |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

HADS total score |

28.0 (8.5) |

19.0 (6) |

40 |

<0.001 |

| HPS total score | 20.0 (10.5) | 14.5 (8.8) | 40 | <0.001 | |

Bonferroni-corrected p<0.000056.

Bonferroni-corrected p<0.002778.

Assessed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test [two-tailed].

HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HPS, Häusliche Pflegeskala (home care scale);

IQR, interquartile range; NRS, numeric rating scale; QOLLTI-F, Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness–Family Carer Version; PPHC, Pediatric Palliative Home Care.

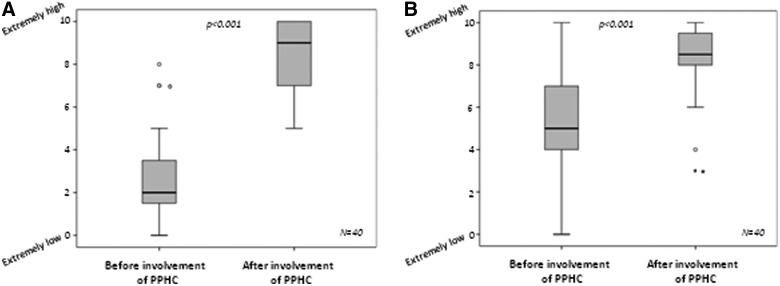

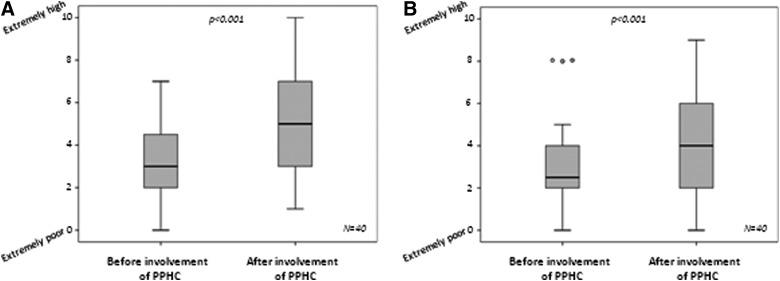

The perceived burden relief for caregivers and the perception of psychological support increased through the involvement of PPHC (see Figure 2), as did the support for activities of daily living. The children's general care situation was significantly improved from the caregivers' point of view. Caregivers felt much better informed about the disease situation (see Figure 4B), and they also felt better taken care of by the PPHC team. In addition, their communication with the child was significantly enhanced. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonparametric data can detect significant differences between two groups even if the medians are equal. No significant changes could be found in the caregivers' communication with the children's general practitioners (GPs). In addition, caregivers reported no changes concerning spiritual care.

FIG. 2.

Perceived burden relief (A) and psychological support (B) for caregivers as assessed by NRS. NRS, numeric rating scales; PPHC, Pediatric Palliative Home Care.

FIG. 4.

Symptom control (A) and clarification of important questions on the diagnosis and prognosis (B) from the caregivers' perspective. Assessed by NRS. NRS, numeric rating scales; PPHC, Pediatric Palliative Home Care.

Regarding their satisfaction with problem solving, the caregivers named psychosocial support by the PPHC team as the most helpful aspect of care (n=40). They particularly identified the 24/7 on-call service, sufficient time for detailed conversations in conjunction with active and continuous investigation of the PPHC team about the patients' and caregivers' condition, and information about the expected course of the child's disease as the most helpful aspects of PPHC. Beside the medical care for the child (n=19), practical concerns such as organization of technical aids, home visits, and assistance in children's advance care planning played an important role (n=23). In four cases the caregivers named specific problems that could not be solved sufficiently (e.g., organizational issues and recognition of parental worries).

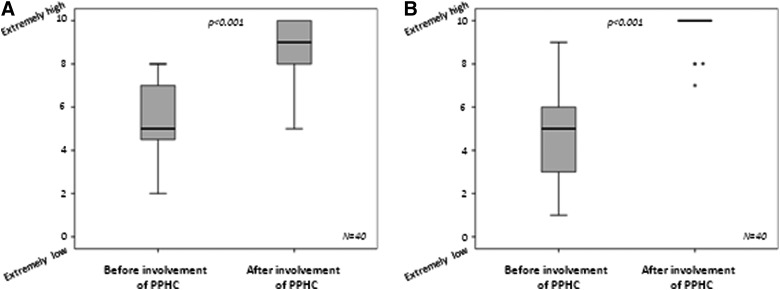

Quality of life, function, and symptoms

After involvement of the PPHC team, the subjective burden of primary caregivers due to the child's disease decreased (see Table 1). Both the caregivers' and the children's QoL improved significantly (see Figure 3), whereby caregivers perceived their own QoL as slightly better than the children's QoL. These findings were confirmed by the results of the validated assessment of caregivers' QoL (QOLLTI-F).

FIG. 3.

Caregivers' QoL (A) and childrens' QoL (B) according to caregivers' ratings. Assessed by NRS. NRS, numeric rating scales; PPHC, Pediatric Palliative Home Care; QoL, quality of life.

While the palliative medicine specialists did not observe a significant change in the children's functional status between first and second assessment (ECOG, mean/median before PPHC=2.4/2 versus after PPHC=2.4/2; n.s.), symptom control was significantly improved through the involvement of the PPHC team as perceived by the caregivers (see Figure 4).

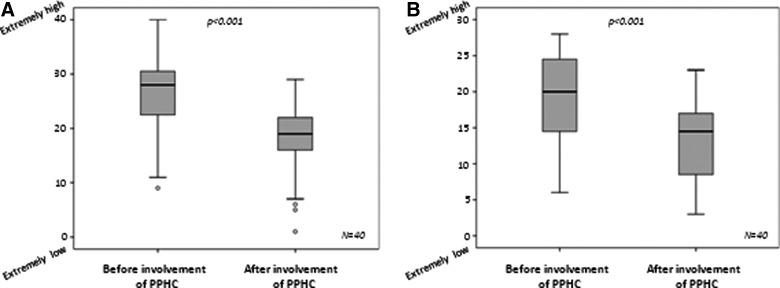

Caregivers' psychological distress and burden

The overall psychological distress and burden of caregivers was also significantly decreased by involvement of the PPHC team (see Figure 5 and Table 1). However, the degree of burden due to the care for a seriously ill child remained high in a significant proportion of parents. Before involvement of the PPHC team, 33 caregivers (83%) showed clinically relevant anxiety (HADS anxiety score≥11), which decreased to 14 (35%) afterwards (P<0.001). Concurrently, the number of caregivers with clinically relevant depression (HADS depression score≥11) decreased from 30 (75%) to 10 (25%; P<0.001). While 18 caregivers (45%) had a high rate in HPS (>20) before involvement of the PPHC team, the HPS score remained high afterwards only in three cases (8%) (P<0.001).

FIG. 5.

Caregivers' psychological distress as assessed by HADS (A) and their burden of care as assessed by HPS (B). HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale; HPS, Häusliche Pflegeskala (home care scale); PPHC, Pediatric Palliative Home Care.

Discussion

Caring for a dying child is one of the most stressful life events possible. Our results suggest that the coordination and provision of palliative home care by a PPHC team can make an important contribution to the quality of care during the children's palliative and dying phase. The high value of PPHC as stressed by former research was clearly supported by our findings.5,18–24 Our data also support the notion that appropriate PPHC provided by a specialized team is able to alleviate caregivers' psychological distress and burden.5,25–28 Knapp and colleagues29 analyzed the status of PPC provision around the world, emphasizing the importance of future advancement in this field. But since the majority of existing studies have taken place after the death of a child, little data are available on the caregivers' needs and experiences with PPHC during the child's illness to date.18,25,26,30–32

Previous studies showed that it is of crucial importance for caregivers to receive information about the child's expected time and way of dying.32,33 In our study, all caregivers identified the possibility to receive accurate information about the child's prognosis and course of the disease as essential components of PPHC. The 24/7 availability of a PPC specialist played a crucial role for caregivers and patients as well. Providing a feeling of safety and shared responsibility in caregivers, PPHC raises the rate of children dying at home and contributes to avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations.5,34,35

Many believe that community pediatricians and GPs have a crucial role in comprehensive PPHC.36–39 However, studies suggest that these pediatricians, many of whom encounter few dying children throughout their career, are uncertain about how to provide such care.40–42 Our study showed that the involvement of a PPHC team did not change caregiver communication with the treating GP or pediatrician, although it did not assess caregivers' attitudes about such communication or about the role of these physicians more generally. This indicates an area for future research, namely, whether efforts to educate private practitioners in PPC might reduce their uncertainty in contact with PPC patients and their families and thereby improve their communication.43,44

Hexem and colleagues45 suggested that religion and spirituality play an important role in the lives of parents whose children are receiving pediatric palliative care. According to Knapp and colleagues,46 spiritual assessments should be conducted for all parents, as different supportive strategies may be required. However, despite the availability of a chaplain in our center, we did not find any significant changes regarding spiritual care in this study. Most of the caregivers explicitly refused any form of spiritual support, which might be due in part to the difficulty in distinguishing between religion and spirituality. In addition, further attention to the specific requirements of families with diverse religious and spiritual backgrounds is needed.47 Despite the growing consensus on spirituality as an integral part of health care, particularly palliative care, its integration into clinical practice remains a challenge.48–50

This study has several limitations. Although not a member of the PPHC team, the interviewer was not blind to the responses and might therefore unconsciously have influenced their direction. In addition, participants' responses may be subject to social desirability bias. Since the study was conducted at a single center, only a relatively small number of families could be enrolled, and therefore no control group could be included and generalizability is limited. On the other hand, due to the personal conduct of the survey in dialogue form, an excellent response rate was achieved and no missing data arose.

Conclusion

Coordination and provision of palliative home care by a specialized PPHC team appears to provide an important contribution to the quality of care in a child's palliative and dying phase. Further research is needed to prove our findings in a larger patient population with varied health care settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all children and parents for their willingness to participate and to share their experiences. Special thanks go to all colleagues of the Coordination Center for Pediatric Palliative Care in Munich for their efforts in identifying potential participants, and to the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung for the financial support of the professorship for Pediatric Palliative Care in Munich. Thanks are also due to Rüdiger Laubender for his statistical counselling. This study was funded by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Aid, Grant-Nr. 107627), which was not involved in the development of the submission or the conduct of the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing interests exist.

References

- 1.McGrath PA: Development of the World Health Organization Guidelines on Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care in Children. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12(2):87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergstraesser E: Pediatric palliative care: When quality of life becomes the main focus of treatment. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172(2):139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchinson F, King N, Hain RD: Terminal care in paediatrics: Where we are now. Postgrad Med J 2003;79(936):566–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care: Palliative care for children. Pediatrics 2000;106(2 Pt 1):351–357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff J, Robert R, Sommerer A, Volz-Fleckenstein M: Impact of a pediatric palliative care program. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010;54(2):279–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vickers JL, Carlisle C: Choices and control: Parental experiences in pediatric terminal home care. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2000;17(1):12–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vickers J, Thompson A, Collins GS, Childs M, Hain R, Paediatric Oncology Nurses' Forum/United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group Palliative Care Working Group: Place and provision of palliative care for children with progressive cancer: A study by the Paediatric Oncology Nurses' Forum/United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group Palliative Care Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(28):4472–4476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy CM, Pollock P, Levy M, Budd E, Caulfield L, Koren G: Home-based palliative care for children—Part 2: The benefits of an established program. J Palliat Care 1990;6(2):8–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess R: Guideline for the regulation of Specialized Outpatient Palliative Care. www.g-ba.de/downloads/62-492-243/RL-SAPV2007-12-20.pdf 2007. (Last accessed October21, 2013)

- 10.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al.: Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5(6):649–655 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen R, Leis AM, Kuhl D, Charbonneau C, Ritvo P, Ashbury FD: QOLLTI-F: Measuring family carer quality of life. Palliat Med 2006;20(8):755–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snaith RP: The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Br J Gen Pract 1990;40(336):305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann-Lingen C, Buss U, Snaith RP: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – German Version. Berne: Verlag Hans Huber, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gough K, Hudson P: Psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37(5):797–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gräßel E: Home Care Scale for the Assessment of Subjective Burden of Mentoring or Nurturing Persons. Ebersberg: Vless Verlag, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichte T, Beyer M, Mand P, Rohde-Kampmann R, Berndt M, Rentz P, et al. : Guidelines for family caregivers—No. 6. German Society for General Medicine, Düsseldorf. leitlinien.degam.de/index.php?id=68 2011. (Last accessed October21, 2013)

- 17.Gräßel E, Chiu T, Oliver R: Development and Validation of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC). Toronto: COTA: Comprehensive Rehabilitation and Mental Health Services, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vollenbroich R, Duroux A, Grasser M, Brandstatter M, Borasio GD, Fuhrer M: Effectiveness of a pediatric palliative home care team as experienced by parents and health care professionals. J Palliat Med 2012;15(3):292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedrichsdorf SJ, Menke A, Brun S, Wamsler C, Zernikow B: Status quo of palliative care in pediatric oncology: A nationwide survey in Germany. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29(2):156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe J: Recognizing a global need for high quality pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57(2):187–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraser LK, Miller M, Draper ES, McKinney PA, Parslow RC, Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network: Place of death and palliative care following discharge from paediatric intensive care units. Arch Dis Child 2011;96(12):1195–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kremeike K, Sander A, Eulitz N, Reinhardt D: Specialized ambulatory pediatric palliative care (SAPPV): A concept for implementing comprehensive care in Lower Saxony. Kinderkrankenschwester 2010;29(10):419–423 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen G, Friedland C, Richter U, Leonhardt H, Gobel U: Out-patient palliative care of children with cancer and their families. Klinische Padiatrie 2004;216(3):183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kopecky EA, Jacobson S, Joshi P, Martin M, Koren G: Review of a home-based palliative care program for children with malignant and non-malignant diseases. J Palliat Care 1997;13(4):28–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapp CA, Contro N: Family support services in pediatric palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2009;26(6):476–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zelcer S, Cataudella D, Cairney AE, Bannister SL: Palliative care of children with brain tumors: A parental perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164(3):225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy MC, Clarke NE, Ting CL, Conroy R, Anderson VA, Heath JA: Prevalence and predictors of parental grief and depression after the death of a child from cancer. J Palliat Med 2010;13(11):1321–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knapp C, Madden V, Wang H, Curtis C, Sloyer P, Shenkman E: Factors affecting decisional conflict for parents with children enrolled in a paediatric palliative care programme. Int J Palliat Nurs 2010;16(11):542–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knapp C, Woodworth L, Wright M, Downing J, Drake R, Fowler-Kerry S, et al.: Pediatric palliative care provision around the world: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57(3):361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheetz MJ, Bowman MA: Parents' perceptions of a pediatric palliative program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013;30(3):291–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Widger K, Picot C: Parents' perceptions of the quality of pediatric and perinatal end-of-life care. Pediatr Nurs 2008;34(1):53–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, Duncan J, Salem-Schatz S, Emanuel EJ, et al.: Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: Impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA 2000;284(19):2469–2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, Bjork O, Steineck G, Henter JI: Care-related distress: A nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(36):9162–9171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider W, Eschenbruch N, Thoms U, Eichner E, Stadelbacher S: Effectiveness and quality assurance in the practice of Specialized Outpatient Palliative Care (SOPC): An exploratory monitoring study. www.philso.uni-augsburg.de/lehrstuehle/soziologie/sozio3/forsohung/pdfs/SAPV_Endbericht_durchgesehen.pdf/ 2012. (Last accessed October21, 2013)

- 35.Bradford N, Irving H, Smith AC, Pedersen LA, Herbert A: Palliative care afterhours: A review of a phone support service. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2012;29(3):141–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Junger S, Vedder AE, Milde S, Fischbach T, Zernikow B, Radbruch L: Paediatric palliative home care by general paediatricians: A multimethod study on perceived barriers and incentives. BMC Palliat Care 2010;9:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubble R, Trowbridge K, Hubbard C, Ahsens L, Ward-Smith P: Effectively using communication to enhance the provision of pediatric palliative care in an acute care setting. J Multidiscip Healthc 2008;1:45–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pirie A: Pediatric palliative care communication: Resources for the clinical nurse specialist. Clin Nurse Spec 2012;26(4):212–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hechler T, Blankenburg M, Friedrichsdorf SJ, Garske D, Hubner B, Menke A, et al.: Parents' perspective on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death and end-of-life decisions for children dying from cancer. Klinische Padiatrie 2008;220(3):166–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies B, Sehring SA, Partridge JC, Cooper BA, Hughes A, Philp JC, et al.: Barriers to palliative care for children: Perceptions of pediatric health care providers. Pediatrics 2008;121(2):282–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carroll JM, Santucci G, Kang TI, Feudtner C: Partners in pediatric palliative care: A program to enhance collaboration between hospital and community palliative care services. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2007;24(3):191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ: Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics 2004;114(5):1248–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCabe ME, Hunt EA, Serwint JR: Pediatric residents' clinical and educational experiences with end-of-life care. Pediatrics 2008;121(4):e731–e737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michelson KN, Ryan AD, Jovanovic B, Frader J: Pediatric residents' and fellows' perspectives on palliative care education. J Palliat Med 2009;12(5):451–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hexem KR, Mollen CJ, Carroll K, Lanctot DA, Feudtner C: How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality, or life philosophy in tough times. J Palliat Med 2011;14(1):39–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knapp C, Madden V, Wang H, Curtis C, Sloyer P, Shenkman E: Spirituality of parents of children in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2011;14(4):437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schultz M, Baddarni K, Bar-Sela G: Reflections on palliative care from the Jewish and Islamic tradition: Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. eCAM 2012;2012:693092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vermandere M, De Lepeleire J, Smeets L, Hannes K, Van Mechelen W, Warmenhoven F, et al.: Spirituality in general practice: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61(592):e749–e760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C: The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: A meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med 2010;24(8):753–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fitchett G, Lyndes KA, Cadge W, Berlinger N, Flanagan E, Misasi J: The role of professional chaplains on pediatric palliative care teams: Perspectives from physicians and chaplains. J Palliat Med 2011;14(6):704–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]