Abstract

Invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites is a complex multi-step process mediated by specific interactions between host receptors and parasite ligands. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologues (RHs) and erythrocyte-binding-like (EBL) proteins are discharged from specialized organelles and used in early steps of invasion. Here we show that monoclonal antibodies against PfRH1 (an RH) block merozoite invasion by specifically inhibiting calcium signalling in the parasite, whereas invasion-inhibiting monoclonal antibodies targeting EBA175 (an EBL protein) have no effect on signalling. We further show that inhibition of this calcium signalling prevents EBA175 discharge and thereby formation of the junction between parasite and host cell. Our results indicate that PfRH1 has an initial sensing as well as signal transduction role that leads to the subsequent release of EBA175. They also provide new insights on how RH–host cell interactions lead to essential downstream signalling events in the parasite, suggesting new targets for malaria intervention.

Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 1 (PfRH1) and erythrocyte-binding-like protein EBA175 are important for parasite invasion of host cells. Here, Gao et al. show that PfRH1 activates calcium signalling, which induces release of EBA175 and allows junction formation between host cell and parasite.

Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 1 (PfRH1) and erythrocyte-binding-like protein EBA175 are important for parasite invasion of host cells. Here, Gao et al. show that PfRH1 activates calcium signalling, which induces release of EBA175 and allows junction formation between host cell and parasite.

Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum) is the most virulent malaria parasite and accounts for the vast majority of deaths (WHO, http://www.rbm.who.int, 2010). Erythrocyte invasion is a complex multi-step process that is mediated by specific interactions between host receptors and parasite ligands. Junction formation between the merozoite and erythrocyte is a crucial step that allows the parasite to irreversibly bind to the host followed by the activation of its motor machinery system that drives the parasite completely into the erythrocyte1. Previous studies suggest the involvement of apical secretory organelles termed rhoptries and micronemes2. In Plasmodium species, a number of key parasite ligands that mediate critical interactions with host receptors during invasion are localized in these apical organelles1. Two protein families are used in early steps of invasion in P. falciparum: reticulocyte-binding protein homologues (RHs) and erythrocyte-binding-like proteins (EBLs)3. RHs and EBLs have been shown to have a crucial role in host cell recognition and sensing as well as virulence4. Members of both protein families can be found in all Plasmodium species, further highlighting their importance in malaria parasite biology. In EBLs, a duffy-binding-like (DBL) domain mediates specific binding to different host cell receptors5 including glycophorins A, B and C as well as the Duffy blood group antigen3. In RHs, the precise erythrocyte-binding regions are still being delineated4,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13; complement receptor 1 (CR1) and basigin have been identified to be the receptors for PfRH4 (ref. 14) and PfRH5 (ref. 15), respectively. Although RHs have been proposed to have an early role in host cell sensing16,17, the EBLs are thought to have a direct role in junction formation18. This suggests that RH sensing and subsequent interaction with a suitable host erythrocyte sends a signal to the merozoite that triggers the subsequent steps of invasion4.

Here we generate monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against the erythrocyte-binding region RII-3 of PfRH1 (a member of the RH family in P. falciparum7). We show that PfRH1 mAbs block merozoite invasion by specifically inhibiting calcium signalling in the parasite rather than by directly interfering with the erythrocyte binding of the parasite. We further show that the inhibition of this calcium signalling prevents EBA175 discharge and thereby prevents junction formation (a key step that enables the parasite to penetrate the erythrocyte using an actin-myosin motor3). Our results demonstrate that PfRH1 and EBA175 have distinct functions, with PfRH1 having an initial sensing and signal transduction role that leads to subsequent EBA175 release from the microneme and to junction formation. These new insights might help to identify new targets for malaria intervention.

Results

Specific PfRH1 mAbs inhibit merozoite invasion

In this work, we use PfRH1 to study key intracellular signalling events that lead to successful erythrocyte invasion. We have previously shown that antibodies targeting an erythrocyte-binding region (RII-3) of PfRH1 (Fig. 1a) can inhibit merozoite invasion7. Here we generated four monoclonal antibodies (mAbs: C49, C41, C2 and C50) against this region and validated their specificity using western blot and immunofluorescence assays. All antibodies recognize the expected 240- and 140-kDa-processed form of PfRH1 in T994 parasite culture supernatant, merozoite and schizont extracts, whereas no equivalent bands were detected in the PfRH1 knockout line T994ΔRH1 (Supplementary Fig. S1a–c). Immunofluorescence assays showed that all mAbs give punctuate patterns that are partially localized with EBA175 (a known microneme protein) at the apical end of merozoites in T994, consistent with the expected location of PfRH1 (Supplementary Fig. S1d). No staining was observed in T994ΔRH1 (Supplementary Fig. S1e), further confirming the specificity of the mAbs.

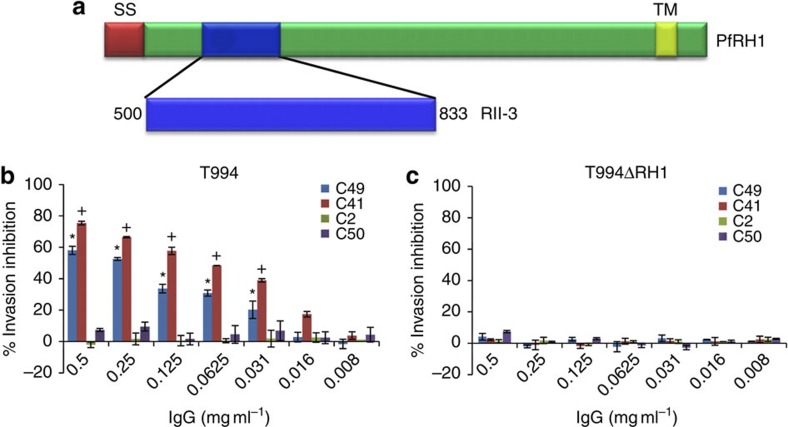

Figure 1. Anti-PfRH1 mAbs significantly block parasite invasion.

(a) Full-length PfRH1 including signal sequence (SS, red), erythrocyte-binding region RII-3 (blue, encompassing amino acids 500–833) and transmembrane domain (TM, yellow). (b,c) Invasion inhibition assays using anti-PfRH1 mAbs (IgG) in T994 (b) and T994ΔRH1 (c). Bar charts show mean±s.e.m.; n=3. *P≤0.0003 by one-way ANOVA, indicating that C49 successfully blocked the invasion in T994 compared with the invasion in the presence of C2 and C50.+P≤0.0003 by one-way ANOVA, indicating that C41 significantly inhibited the invasion compared with C2 and C50.

To establish whether the different mAbs were able to inhibit merozoite invasion, inhibition assays with increasing concentration of antibodies were carried out using T994 and T994ΔRH1 (Fig. 1b,c). We found that mAbs C2 and C50 have no significant effect on invasion, whereas both mAbs C49 and C41 inhibit invasion in a dose-dependent manner in T994. In contrast, none of the antibodies has any impact on T994ΔRH1, in line with their specificity to PfRH1. Similar results (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b) were obtained when using the parasite lines W2mef and W2mef/NM, which are known to differ in their requirement for PfRH1 in invasion7,19, suggesting that both C49 and C41 are invasion-inhibiting mAbs. To ensure that the invasion inhibitory effect is not because of the large size of the mAb (which could lead to a secondary blocking effect), we purified the Fab fragment of mAb C41 (Supplementary Fig. S2c, insert) and performed invasion inhibition assays20,21. The purified C41 Fab fragment significantly blocks invasion in a dose-dependent manner in T994 parasites (Supplementary Fig. S2c), confirming that mAb C41 directly targets PfRH1.

Inhibitory mAbs block invasion before junction formation

Merozoite invasion inhibition by antibodies is often caused by antibodies directly interfering with the binding of the parasite to its receptor. We therefore assessed the ability of the different mAbs to inhibit PfRH1 binding to erythrocytes. Both non-inhibitory mAbs (C2 and C50) and inhibitory mAbs (C49 and C41), at concentrations (0.3 mg ml−1) shown to effectively inhibit merozoite invasion (Fig. 1b), have no impact on erythrocyte binding by PfRH1 (Fig. 2a,b), suggesting that invasion-blocking mAbs act independently of erythrocyte binding. To further determine the epitope specificity, four N-terminal overlapping fragments (N1–N4) derived from RII-3 were expressed as recombinant proteins and screened using the mAbs (Supplementary Fig. S3). The size of each fragment was confirmed using anti-His-tag mAbs (Supplementary Fig. S3f). None of the PfRH1 mAbs recognizes N1, whereas C2, C41 and C49 recognize N4 only. C50 is able to detect N2, N3 and N4 (Supplementary Fig. S3b–e), suggesting that C50 binds to a different epitope from that of C2, C41 or C49. On the basis of the western blot results, we further synthesized six overlapping peptides (Supplementary Fig. S3g). The inhibitory mAbs C41 and C49, as well as the non-inhibitory mAb C2, recognize the same 15-mer peptide, whereas another non-inhibitory mAb C50 recognizes a different peptide (Supplementary Fig. S3h). It is somewhat surprising that the non-inhibitory and inhibitory mAbs recognize the same peptide; however, as an epitope is 5–8 amino-acid long, it is possible that multiple distinct epitopes lie within the same peptide. In fact, previous studies have shown that mAbs against epitopes that are very close to each other exhibit different effects on cellular or biological functions20,21,22.

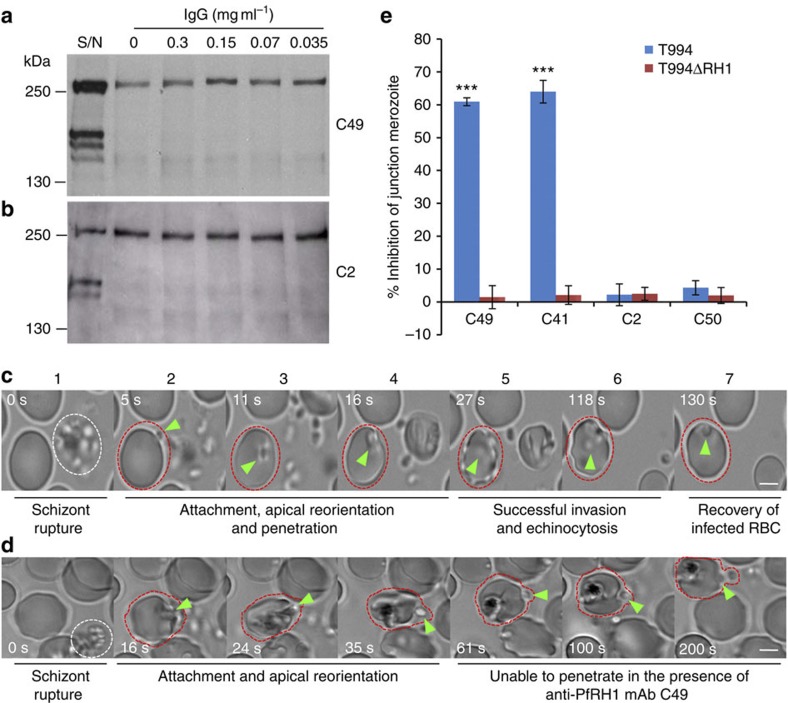

Figure 2. Anti-PfRH1 mAbs inhibit invasion before junction formation.

(a,b) Erythrocyte binding assays of T994 parasite culture supernatants using the C49 (a) and C2 (b) mAbs. Neither C49 nor C2 (0.035–0.3 mg ml−1) was able to inhibit the erythrocyte binding of PfRH1. T994 parasite culture supernatants (S/N) were used as a quality control. Molecular sizes are indicated on the left (in kDa). (c,d) Snapshots taken from time-lapse live movie microscopy of invasion of W2mef by merozoites in the absence (c) or presence (d) of C49 mAb. Time-elapsed post schizont rupture is indicated in each snapshot in seconds (sec, white). A white dotted circle indicates a rupturing schizont. Green arrows point to merozoites. A red dotted circle around an erythrocyte is added to help follow the infection. Scale bars=5 μM. (c) In the absence of mAb, the merozoite released from a mature schizont (white cycle) attaches, apically reorients and penetrates into an uninfected erythrocyte. Following successful invasion, deformation of infected erythrocytes occurs (echinocytosis) and by 2 min the erythrocytes recover back to its normal shape. (d) In the presence of C49, the merozoite released from a mature schizont attaches and apically reorients, but it is unable to penetrate the erythrocyte even after 3 min. Also see Supplementary Movies 1,2. (e) Anti-PfRH1 inhibitory mAbs significantly reduce merozoite junction formation. T994 or T994ΔRH1 schizonts were pretreated with Cyto D and allowed to rupture in the absence or presence of anti-PfRH1 mAbs (0.2 mg ml−1). Junction-arrested merozoites were counted microscopically. Bar chart indicates the counting of junction-arrested merozoites with mAbs C2, C41, C49 and C50 in T994 and T994ΔRH1 compared with the arrested parasites in the absence of mAbs. Inhibitory mAbs C49 and C41 significantly blocked merozoite junction formation in T994. The error bar indicates the s.e.m.; n=3. ***P≤0.00014 by one-way ANOVA indicates the significant differences between the effects of inhibitory mAbs (C49 and C41) and those of non-inhibitory mAbs (C2 and C50).

Live video microscopy is a powerful tool to dissect merozoite invasion, and it has been effectively used to demonstrate the role of another merozoite invasion protein, PfAMA1, during merozoite re-orientation step in invasion23. Using time-lapse live video microscopy, we followed the process of merozoite invasion both in the presence and absence of invasion inhibitory antibodies (Fig. 2c,d, Supplementary Fig. S4a,b and Supplementary Movies 1–7). We found that, in the absence of antibodies, newly released merozoites rapidly attach, reorient and invade erythrocytes (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Movie 1). Immediately after invasion, the erythrocyte shrinks and echinocytosis occurs, with the infected erythrocyte recovering its shape within 2 min. Interestingly, in the presence of the invasion inhibitory antibody C49 (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Movie 2,6) or C41 (Supplementary Fig. S4a and Supplementary Movie 3,7), merozoites are able to attach and reorient themselves but are unable to penetrate the erythrocyte even after 3 min, despite extensive distortions of the erythrocyte being observed. In contrast, invasion similar to that seen in the absence of any antibody is observed in the presence of the non-inhibitory antibodies C2 (Supplementary Fig. S4b and Supplementary Movie 4) or C50 (Supplementary Movie 5). The inability of the merozoite to penetrate the erythrocyte despite reorientation and clear binding suggests that the inhibitory antibodies interfere with a subsequent step of the invasion process. Junction formation is known to be linked to the irreversible commitment of the merozoite to invasion, and recent studies have shown that PfRH1, PfRH2a/2b and PfRH5 localize at the tight junction, suggesting a specific role for the PfRH proteins during this part of the invasion process6,24,25,26. Therefore, to assess whether the inhibitory mAbs prevented junction formation, merozoites were arrested at the tight junction by treatment with cytochalasin D (Cyto D)27. Experiments were carried out in the absence and presence of PfRH1 mAbs, and junction-arrested merozoites were counted. Similar to the invasion inhibition assay, inhibitory mAbs C49 and C41 significantly reduce junction-arrested merozoites as compared with C2 and C50 in both T994 and W2mef (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S4c). In contrast, no effect is seen in T994ΔRH1 and W2mef/NM, in line with PfRH1 not having a role in these parasites. Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that inhibitory mAbs inhibit the invasion before junction formation and suggest that PfRH1 could have a key signalling role ahead of junction formation.

PfRH1 inhibitory mAbs block Ca2+ signalling during invasion

Previous work has suggested that secretion of EBA175 from the micronemes onto the surface of the merozoite is a prerequisite for junction formation and is triggered by calcium (Ca2+) release in the merozoite28. Here we carried out real-time measurement of Ca2+ signalling in the presence/absence of Cyto D during merozoite invasion using freshly isolated free merozoites from T994 parasite. We found that Ca2+ signal increases both in the presence and absence of Cyto D (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Data 1–6), demonstrating that the signal originates before or at junction formation. This allowed us to further elucidate whether the invasion inhibitory mAbs targeting PfRH1 directly had an impact on Ca2+ signalling. We observed that the cumulative intracellular Ca2+ signal during merozoite invasion is significantly reduced in the presence of the inhibitory mAbs C41, as compared with the non-inhibitory mAbs C2 or no antibody control (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Data 1–6). No antibody effect on Ca2+ signalling is seen in T994ΔRH1 (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Data 1–6). These results suggest that PfRH1 inhibitory mAbs inhibit invasion by blocking Ca2+ signalling. Control experiments using the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM showed that treatment of merozoites with A23187 leads to a significant increase in the Ca2+ signal over time, whereas pretreatment with BAPTA-AM significantly reduces Ca2+ signals (Supplementary Fig. S5, Supplementary Data 1–6 and Supplementary Table S2). Although the Ca2+ signal observed during invasion assays is only derived from successfully invading merozoites, all viable merozoites are expected to give Ca2+ signals after A23187 treatment, explaining the higher signal obtained (compare Fig. 3b with Supplementary Fig. S5). Importantly, functional C41 Fab fragments also block Ca2+ signalling in T994 parasite during invasion (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Data 1–6) as effectively as mAbs C41. This further confirms that the specific binding of inhibitory mAbs to PfRH1 is important for blocking Ca2+ signalling.

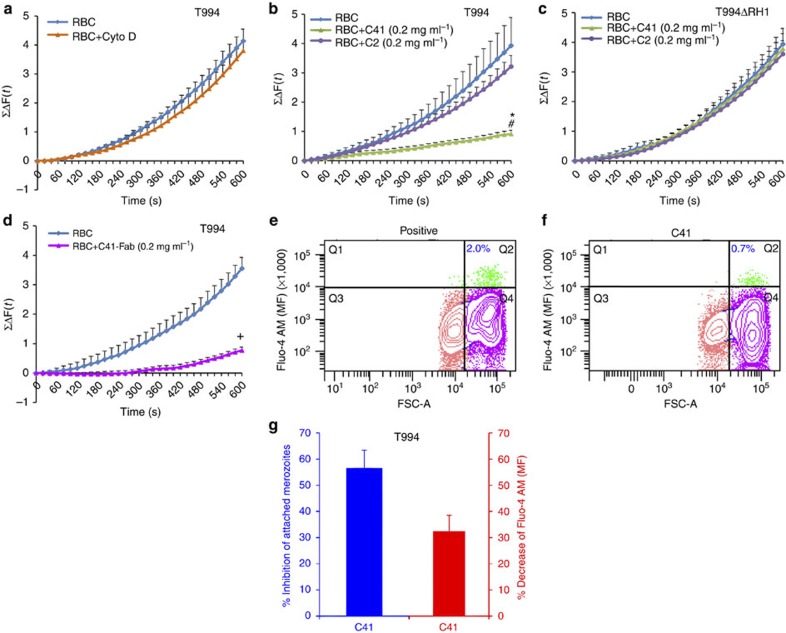

Figure 3. Detection of cytosolic Ca2+ levels during merozoite invasion.

(a–d) Cytosolic Ca2+ levels were detected using a fluorescence plate reader. (a) Preloaded T994 merozoites with Fluo-4AM were incubated with erythrocytes in the absence (RBC) or presence of Cyto D (RBC+Cyto D). (b,c) Preloaded T994 (b) or T994ΔRH1 (c) merozoites were incubated with erythrocytes in the absence (RBC) and presence of either C41 (RBC+C41 (0.2 mg ml−1)) or C2 (RBC+C2 (0.2 mg ml−1)). (d) Preloaded T994 merozoites were incubated with erythrocytes in the absence (RBC) or presence of mAb C41 Fab fragment (C41 Fab (0.2 mg ml−1)). The cumulative changes of Ca2+ levels (≤ΔF (t)) in merozoites over 600 s were summed up and plotted against time (s). Experimental data were presented as the mean±s.e.m.; n=3. *P≤0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, indicating that C41 successfully blocked the Ca2+ signalling in T994 when compared with the absence of C41. #P≤0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, indicating that C41 successfully blocked the Ca2+ signalling in T994 when compared with the presence of C2.+P≤0.0001 by one-way ANOVA, indicating that C41 Fab fragment significantly inhibited the Ca2+ signalling in T994, when compared with the absence of C41 Fab fragment. (e–g) Cytosolic Ca2+ levels detected by flow cytometry. Representative FACS contour plots (e,f) were gated by size (FSC-A) versus mean fluorescence (MF) of Fluo-4 AM of merozoite (DAPI (+)) incubated with erythrocytes in the absence (e, Positive) or presence of C41 (f, C41). Vertical gating is to separate the free merozoites with low FSC from the RBC-attached merozoites with high FSC, whereas horizontal gating is to differentiate intercellular Ca2+ levels. Q1 (green) represents free merozoites with Fluo-4 AM signals. Q2 (green) represents invading merozoites with increasing Fluo-4 AM signals. The number (blue) in Q2 represents % population of attached merozoites. Q3 (peach) represents free merozoites with no signal. Q4 (pink) represents attached merozoites with no signal. (g) Statistical analysis of the effect of C41 on Ca2+ signalling during T994 merozoite invasion by FACS. C41 was able to reduce the number of invading merozoites to 56.6% (blue) and to decrease the overall Ca2+ level to 32.42% (red) during invasion, as compared with that in the absence of C41. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.; n=3.

We performed similar experiments using flow cytometry to measure Ca2+ levels during invasion of fresh erythrocytes by free merozoites in the presence of Cyto D, as well as in the presence/absence of inhibitory mAbs. Invading merozoites will be arrested by Cyto D after junction formation, whereas merozoites in the presence of inhibitory antibodies will either detach or remain attached to the RBC without forming a junction. On the basis of these criteria, there are two distinct populations: free merozoites and RBC-bound merozoites. Staining for DAPI (+) events identifies all merozoites, whereas gating for size enables us to distinguish between free and RBC-bound merozoites (Fig. 3e,f). An inhibitory antibody C41 can reduce the number of invading merozoites to 56.6% (Fig. 3g-blue) and decrease the overall Ca2+ level to 32.42% (Fig. 3g-red) during invasion, when compared with the absence of inhibitory mAbs. This result is consistent with our previous conclusion, supporting the accessibility and reproducibility of real-time measurement of Ca2+ signalling by using a fluorescence plate reader. Taken together, these results strongly support the conclusion that PfRH1 has a direct or indirect role in the regulation of Ca2+ signalling during invasion. Hence, we propose that binding of the mAbs to PfRH1 directly inhibits a signal to trigger Ca2+ signal, or it has an indirect effect by preventing the recruitment of other proteins important for the initiation of the signal.

Merozoite viability

To ensure that the observed Ca2+ signal was indeed due to merozoite invasion, each merozoite preparation in parallel to Ca2+ signalling studies was assessed for their ability to invade fresh erythrocytes. T994 and T994ΔRH1 merozoites from each preparation successfully invade erythrocytes, and T994 invasion is successfully inhibited by C41 but not C2. In contrast, none of the antibodies has any impact on invasion in the case of T994ΔRH1 (Supplementary Table S3). Importantly, there is a clear correlation (R2=0.836) between invasion and Ca2+ signal, with low invasion (due to antibody blocking) leading to low Ca2+ signal (Fig. 4a). In addition, we followed the kinetics of merozoite invasion using heparin treatment29 and observed that almost 75% of isolated merozoites invade erythrocytes in a linear manner (R2=0.991) over the first 10 min (Fig. 4b), which is in line with time-dependent Ca2+ data. Only a small proportion (25%) of the total invading merozoites have not invaded within 10 min, confirming that the observed increase in Ca2+ signal was contributed by the majority proportion of invading merozoites over the first 10 min. Taken together, these data clearly indicate that viable invasion-competent merozoites contribute to the signals.

Figure 4. Correlation between invasion and Ca2+ signal.

(a) T994 merozoites isolated from each Ca2+ measurement experiment (Fig. 3b) were also used in parallel to test invasion (Supplementary Table S3). The percentage of invasion (Parasitemia (%), horizontal axis) is plotted against the Ca2+ signals at t=600 s (≤ΔF (t=600 s), vertical axis) (Fig. 3b). Blue diamonds represent merozoites incubated with erythrocytes in the absence of mAbs (RBC). Green triangles represent merozoites incubated with erythrocytes in the presence of inhibitory mAb C41 (RBC+C41 (0.2 mg ml−1)). Purple circles represent merozoites incubated with erythrocytes in the presence of non-inhibitory mAb C2 (RBC+C2 (0.2 mg ml−1)). The R-square (R2) with value of 0.836 indicates strong correlation between invasion and Ca2+ signalling. (b) Merozoite invasion kinetics assay under heparin treatment. Freshly isolated T994 merozoites were allowed to invade erythrocytes followed by treatment with heparin (200 μg ml−1) at different time points (2–10 min with 2 min interval) to inhibit invasion. After the final time point, cultures were incubated for 40 h, and resulting parasitemias were analysed by flow cytometry. The proportion of merozoites that have invaded with increasing time is shown as % of maximum invasion obtained in uninhibited culture. The rate of merozoite invasion over time is linear (R2=0.991). Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.; n=3.

An EBA175 inhibitory mAb has no effect on Ca2+ signalling

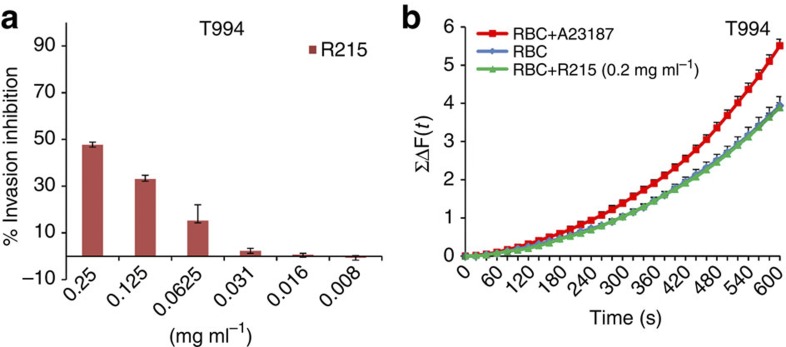

In line with published data, our results indicate that PfRH1 has a direct role in Ca2+ release, which then triggers microneme and EBA175 secretion. If this is indeed correct, it would be expected that blocking EBA175 function and thereby junction formation would have no impact on Ca2+ signalling. To investigate this further, we used the invasion-blocking mAb R215, which targets EBA175 region II (ref. 30). As previously described, mAb R215 is able to dose-dependently block invasion, with maximum inhibition around 47.7% ±1.11 at 0.25 mg ml−1 (Fig. 5a)30. However, this antibody has no effect on intracellular Ca2+ signalling during invasion (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Data 1–6). This result confirms that invasion-blocking antibodies targeting EBA175 act after Ca2+ signalling, whereas those targeting PfRH1 act before Ca2+ signalling, and clearly highlights the different roles that are performed by PfRH1 and EBA175.

Figure 5. The R215 mAb against EBA175 region II inhibits invasion but not Ca2+ signalling.

(a) Invasion inhibition assay using anti-EBA175 mAb R215 in T994 parasites. Bar charts show invasion inhibition of different concentrations (0.25–0.008 mg ml−1) of the EBA175-specific mAb R215 in T994. Bar charts show mean±s.e.m.; n=3. (b) Cytosolic Ca2+ levels were detected by using a fluorescence plate reader. Preloaded T994 merozoites with Fluo-4AM were incubated with erythrocytes in the absence (RBC) or presence of R215 (RBC+R215 (0.2 mg ml−1)). Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (RBC+A23187) was used as positive control. Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels during merozoite invasion were assessed over time using a fluorescence plate reader. ≤ΔF(t) that reflects the total changes of cytosolic Ca2+ levels in merozoites were plotted against time (s). Experimental data were presented as the mean±s.e.m.; n=3.

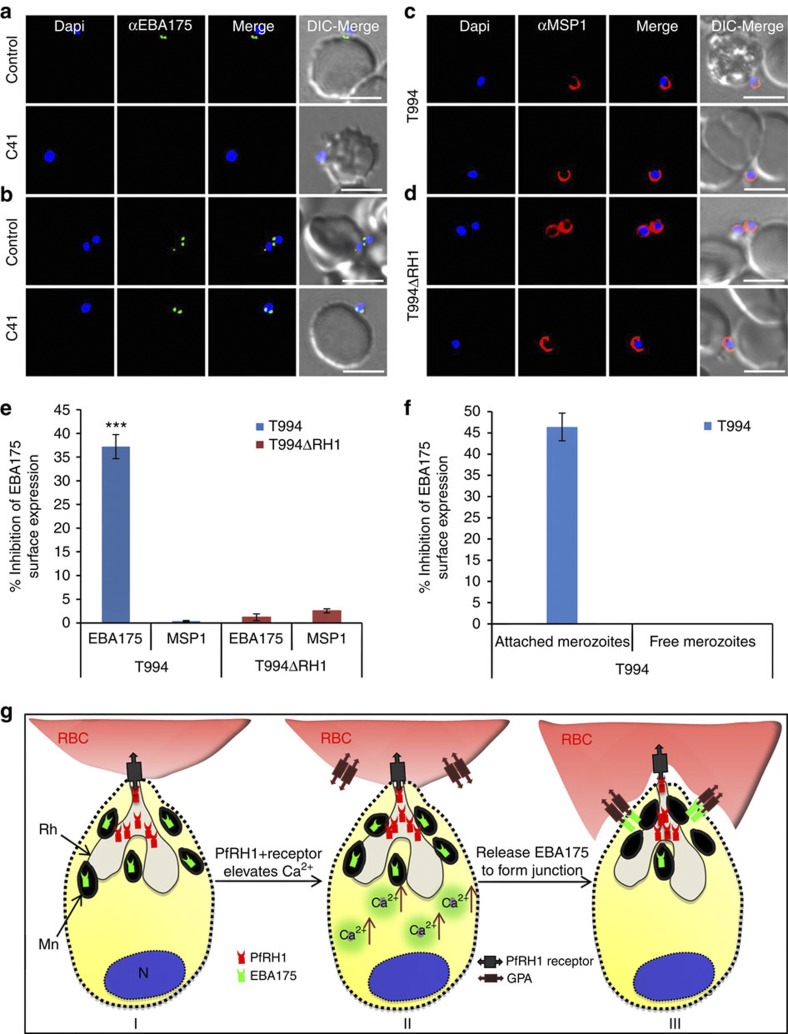

PfRH1 inhibitory mAbs block EBA175 expression

To investigate whether the inhibition of Ca2+ signalling by PfRH1 inhibitory mAbs has a downstream effect on the surface expression of EBA175, we assessed the translocation of EBA175 onto the merozoite surface. Merozoites arrested by Cyto D during erythrocyte invasion in the presence/absence of invasion inhibitory mAbs were surface stained with either antibodies against EBA175 or the merozoite surface marker MSP1. Surface expression of EBA175 was observed under fluorescence microscopy or measured under the fluorescence plate reader. Microneme protein EBA175 of impermeabilized merozoites will not be stained unless they are translocated to the surface of merozoites. Immunofluorescence assays clearly showed that the invasion inhibitory antibody C41 blocks surface expression of EBA175 in T994 (Fig. 6a lower panel), whereas it has no effect on T994ΔRH1 parasites (Fig. 6b lower panel). In the absence of C41, EBA175 is expressed on the surface of both T994 and T994ΔRH1 (upper panels of Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, the inhibitory antibody has no effect on the detection of MSP1 on the surface of merozoites (Fig. 6c,d). Quantification of the overall impact of EBA175 surface expression in the parasite population was assessed using a fluorescent plate reader. In T994, overall EBA175 surface expression is reduced by >35% by the inhibitory antibody C41, whereas no impact is seen in T994ΔRH1 or on the surface expression of MSP1 (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Table S4). Streptolysin O (SLO) is often used to selectively permeabilize the plasma membrane of P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes by forming stable proteinaceous pores without altering the orientation of membrane proteins31. Permeabilization of T994 merozoites with SLO before staining with EBA175 antibody showed no difference in overall EBA175 expression (internal and surface) between free and junction-arrested merozoites in C41-treated cultures as compared with the control. This result was confirmed by performing immunofluorescence assays and by measurement using the fluorescent plate reader (Supplementary Fig. S6 and Supplementary Table S5). To further determine whether SLO could effectively permeabilize merozoite membrane to distinguish protein expression internally or on the surface, nucleoporin 100 (Nup 100; a nuclear periphery marker) and histone marker H3K9ac were used32. In merozoite permeabilized with SLO, Nup 100 localizes in the nuclear periphery outside the DAPI-stained area, whereas H3K9ac tends to co-localize with DAPI-stained area (Supplementary Fig. S7a,b). No staining was found in impermeabilized merozoites (Supplementary Fig. S7c,d). Taken together, these data confirm that C41 blocks EBA175 surface expression on merozoites during invasion.

Figure 6. Effect of anti-PfRH1 inhibitory mAbs on merozoite surface expression of EBA175 during invasion.

(a–d) Surface expression of EBA175 and MSP1 on T994 and T994ΔRH1 was detected by immunofluorescence assays. Isolated T994 (a,c) or T994ΔRH1 (b,d) merozoites were directly incubated with erythrocytes containing 4 μM Cyto D in the absence (Control) and presence (C41) of C41 (0.2 mg ml−1) before analysis of expression of EBA175 and MSP1 at the junction. Both differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images were captured. Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI (blue). EBA175 is shown in green, whereas MSP1 is shown in red. Fluorescence images, merged fluorescence images (DAPI and green or DAPI with red) and merged fluorescence images with DIC images are shown. Scale bars=10 μM. (e) EBA175 surface expression on merozoites was detected by using a fluorescence plate reader. Surface expression of EBA175 and MSP1 on merozoite in the presence of C41 was compared with their controls. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.; n=3. ***P≤0.000025 by one-way ANOVA, indicating that C41 significantly decreases the surface expression of EBA175 in T994. (f) T994 merozoite EBA175 surface expression was also detected by flow cytometry during invasion (detail shown in Supplementary Fig. S8). Statistical analysis of the effect of C41 on merozoite EBA175 surface expression is shown. Merozoite attached to RBCs surface expression of EBA175 in the presence of C41 was compared with its positive control. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.; n=4. (g) Schematic diagram of Ca2+ signalling in junction formation during erythrocyte invasion. After the merozoite initially attaches to the erythrocyte (RBC) and reorients itself, PfRH1 released from rhoptry (Rh) is responsible for sensing the apical end interaction (I). The binding of PfRH1 to its receptor triggers an increase of intracellular Ca2+ (II). Rise in cytosolic Ca2+ levels results in release of microneme (Mn) proteins such as EBA175 to bind to glycophorin A (GPA), which leads to tight junction formation (III).

We provide additional support for the surface expression of EBA175 on junction-arrested T994 merozoites using flow cytometry. Isolated merozoites were allowed to invade fresh erythrocytes in the presence of Cyto D as well as in the presence/absence of inhibitory mAbs. In addition, labelling for EBA175 surface expression with anti-EBA175 antibodies allowed us to identify the population of free and arrested merozoites that express EBA175 on their surface. Analysis of ~5,000 DAPI (+) merozoites showed that, in the absence of inhibitory antibodies, free merozoites make up 47.1% of population, of which 0.2% show EBA175 staining. In contrast, 40.7% of the 52.9% RBC-bound merozoites show EBA175 staining. In the presence of invasion inhibitory antibodies, free merozoites make up 52% of population, of which 0.5% are EBA175 positive, whereas only 17% of the 47.8% RBC-bound merozoites are EBA175 positive (Supplementary Fig. S8). The data show that there is an ~45% inhibition of EBA175 surface expression in RBC-bound merozoites in the presence of the invasion inhibitory antibody (Fig. 6f), in line with the data obtained using the fluorescence plate reader (Fig. 6e). In addition, these results show that free merozoites hardly express EBA175 on the surface; furthermore, it also shows that in the absence of invasion inhibitory antibodies more RBC-attached merozoites are expressing EBA175, in line with them having formed a junction. Taken together, our data provide the first evidence that PfRH1 has a crucial role in triggering intracellular Ca2+ signal, which then leads to the subsequent release of EBA175 to form tight junction.

Discussion

Ca2+ is a second messenger in eukaryotic cell signalling and is typically released from intracellular stores in response to an external stimulus (chemical, electrical or mechanical) that triggers a signalling cascade, which leads to a rise in cytoplasmic-free calcium33. Apical secretion of micronemal and rhoptry proteins has been observed upon contact of the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii34,35 as well as P. falciparum36,37 with their host cells, thereby mediating invasion. In T. gondii increased intracellular Ca2+ has been shown to trigger both microneme protein secretion as well as parasite egress from host cell35,38, and recently it has been shown that a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ because of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 triggers secretion of microneme proteins such as EBA175 to the merozoite surface28. The precise signalling mechanisms that lead to the release of invasion proteins in a coordinated manner during invasion are not clear. Recent work by Singh et al. has shown that increase in the intracellular Ca2+ is the key step leading to the release of EBA175 from the microneme. EBA175 binding to its glycophorin receptor subsequently leads to the release of rhoptry proteins CLAG3.1 and PfRH2b. This is in line with our findings that PfRH1-induced Ca2+ signalling triggers EBA175 release. Previous work has shown that RH proteins appear to be located at the rhoptry neck, and our data would indicate that this enables at least some of the RHs to mediate the initial interactions with the erythrocyte thereby triggering Ca2+ release and microneme discharge. The bulk of the rhoptry content, including the majority of RH, is discharged only after microneme release. It will now be interesting to establish any additional roles for RHs beyond the initial sensing. In the study by Singh et al., Ca2+ release is triggered by changing the concentration of K+ in the buffer from a high to a low to reflect difference in the concentration of K+ inside erythrocyte as compared with the blood plasma. In contrast, in our study, merozoites are kept in normal growth media that require PfRH1 engagement with erythrocytes to trigger Ca2+ release. In future, it is desirable to further address the effect of K+ level changes compared with PfRH1-mediated changes for eliciting Ca2+ level increases. This could determine whether the K+-mediated signalling is upstream or independent of the PfRH1-mediated signalling during invasion. The relative importance of the two mechanisms in vivo also needs to be resolved. On the basis of our data, we hypothesize that the complex invasion process begins with a relatively small amount of PfRH1 exposed at the rhoptry duct interacting with its receptor on the erythrocyte surface, thereby either directly or indirectly activating a signalling cascade that leads to the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores, followed by triggering microneme and rhoptry discharge and junction formation (Fig. 6g). This is consistent with a recent finding showing that Ca2+-mediated microneme discharge is important for invasion in both T. gondii and P. falciparum39. Our results also demonstrate a function for RHs that is independent of rhoptry discharge and occurs after microneme secretion, possibly indicating that RHs are moved to an active site ahead of the release of the rest of the rhoptry content.

In future, it will now be important to further determine the mechanism by which the RH-mediated signal is passed to the merozoite to trigger Ca2+ release. Overall, our results provide new insights on the finely regulated signalling cascade that is required to ensure successful invasion of the merozoite and to open up a path for the analysis of signalling pathways involved in regulated secretion of apical organelles during invasion. Together this will provide us with a better understanding of the signalling mechanisms important in merozoite invasion and how these processes might be a new target for malaria intervention.

Methods

P. falciparum strains and culture

P. falciparum parasite lines T994, W2mef (MR4) and T994ΔRH1 (ref. 40) were cultured in fresh erythrocytes from healthy human donors (after obtaining informed consent) and RPMI supplemented with 5% albumax (Invitrogen)41. W2mef parasites were allowed to grow in erythrocytes treated with 10 mU ml−1 neuraminidase (Nm; Roche). After 2–3 weeks, the W2mef parasite adapts and grows in neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes (sialic acid independent)7,26. This switched parasite was named W2mef/NM parasite.

PfRH1 monoclonal antibodies generation and purification

PfRH1 hybridoma cells were developed by BioGenes (Germany) using purified soluble recombinant protein PfRH1-RII-3 (ref. 7). Positively selected hybridoma cells were cultured in 2% FBS-DMEM (Invitrogen). Purification of PfRH1 mAbs IgG from cell culture medium was carried out by using standard purification procedures (HiTrap Protein G HP, GE healthcare). Monoclonal antibody C41 Fab fragment was generated and purified by using standard procedures (Pierce Fab Micro Preparation Kit, Thermo Scientific). The authenticity of the Fab fragment was confirmed by 12% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad) followed by coomassie blue staining (Sigma), which yielded one band of ~50 kDa under nonreducing conditions.

Western blot of parasite extracts and culture supernatants

Parasite culture was synchronized at the ring stage with 5% D-sorbitol (Sigma) and cultured to mature schizont stages42,43. Tightly synchronized late schizonts were purified using 68% Percoll gradient centrifugation44. Merozoites were purified from schizont extract by filtration under nitrogen cavitation45,46,47,48. Schizonts and merozoite extracts were washed twice with PBS, lysed directly into sample buffer and frozen and thawed three times, followed by separation on 12% SDS-PAGE. Mouse mAb g12 (1:1,000, MR4)49 was used as a loading control for merozoite extracts, whereas rabbit α-actin polyclonal antibodies (1:1,000, Sigma) were used for schizont extracts. To make parasite culture supernatant, purified schizonts were allowed to grow in the absence of RBC at 37 °C with shaking. Cells were collected by centrifugation after 16 h, and supernatants were either stored in aliquots at −80 °C or directly separated on 6% SDS-PAGE. Micronemal marker EBA175-specific antibody50 (1:5,000, MR4) was a loading control for parasite culture supernatant. Following electrophoresis, gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (0.2 μm) (Bio-Rad). Specific proteins were detected by using PfRH1 mAbs (1:5,000), followed by HRP-linked secondary antibodies (1:10,000) and enhanced chemiluminescence (GE healthcare).

Invasion inhibition assay

Synchronized late-stage schizonts were purified, and 160 μl of parasite suspension was added in duplicate in a 96-well flat bottom microtitre plate containing PfRH1 mAbs (0.008–0.5 mg ml−1), purified C41 Fab fragment (0.008–0.5 mg ml−1) or EBA175 mAb R215 (0.008–0.25 mg ml−1), respectively. A total of 1,000 erythrocytes were scored for presence of rings on Giemsa-stained smears after 24 h for reinvasion. Invasion (Inv) was assessed as (%) parasitemia. (%) Parasitemia=(total number of ring-infected RBCs/total number of RBCs) × 100. Invasion in the presence of mAbs was compared with positive controls of invasion of the same parasite lines in normal complete RPMI. Invasion inhibition efficiencies were determined as follows: (%) inhibition efficiency=(1−Inv(mAbs)dilu/Inv(positive)) × 100. Data shown are from three biological replicates. Each biological replicate has two technical replicates. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Erythrocyte binding assays

Hundred microliters of T994 parasite culture supernatant was incubated with 100 μl of packed normal erythrocytes in the presence of PfRH1 mAbs (at final concentration ranging from 0.3 down to 0.035 mg ml−1) at 37 °C for 1 h7,26.

Junction merozoite blocking assay

Merozoites were arrested in the erythrocyte junction by treatment with cytochalasin D (Cyto D) (Sigma)26,27. Purified late-stage schizont parasites were added to the completed RPMI containing fresh erythrocytes in 96-well plates. Cyto D was added to the final concentration of 0.1 μM. PfRH1 mAbs were also present at 0.2 mg ml−1 concentration if required. After 8 h incubation, Giemsa (Sigma)-stained smears were prepared for counting merozoites arrested at junction formation by using light microscopy. A total of 1,000 erythrocytes were scored. The number of junction-arrested merozoites in the presence of mAbs was compared with that in a positive control of the same parasite. Junction merozoite inhibition efficiencies were determined as follows: % inhibition of junction merozoite=(1−total number of junction merozoites (mAbs)/total number of junction merozoites (positive control)) × 100. Data shown are from three biological replicates. Each biological replicate has two technical replicates. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Expression of four overlapping regions from RII-3

Four N-terminal overlapping fragments from RII-3 were amplified by PCR, expressed as His-tag recombinant proteins by BL21 (DE3) (Stratagene)7, named N1 (500–692 amino acid (aa)), N2 (500–726 aa), N3 (500–746 aa) and N4 (500–773 aa), followed by 12% SDS-PAGE and probed with mAbs C49, C41, C2 and C50, respectively (1:5,000). A mAb against 6X His-tag (αHis, 1:5,000, Clonetech) was used as loading control. For the PCR, the forward primer was 5′-GACCATATGTTACAAATAGTACAACAAAAACTTTTAGAAATC-3′ and the reverse primers were 5′-AACCTCGAGAGAAATAAGTTGAATCGTCTCATTATTTT-3′ (N1), 5′-AACCTCGAGGGATTTAAGAAGATTTTGGATGTTTT-3′ (N2), 5′-AACCTCGAGTTGTTTTAATATATATTTAGAAATTGTGTCTATGAA-3′ (N3), and 5′-AACCTCGAGGTTTTGTTCATTTTTTATTTCTTCAAGAT-3′ (N4).

Peptide generation and epitope mapping of PfRH1

Peptide design was based on the mAbs recognition of four His-tag recombinant overlapping fragments derived from RII-3 by western blot (Supplementary Fig. S3a–e). All biotinylated overlapping synthetic peptides were synthesized by Peptide Synthesis Core facilities, SBS, NTU. The lyophilized peptides were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma). Peptide stocks were diluted in PBS+0.1% BSA to make up 2.5 μg ml−1. The streptavidin-coated 96-well plate, pre-blocked with Superblock blocking buffer (Thermo Scientific), was washed three times with 200 μl wash buffer (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2, 0.1% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20). Hundred microliters of the peptide solution was added into each well of the streptavidin-coated plate and incubated for 2 h at room temperature (RT) with gentle shaking. After four washes, 100 μl of mAb (C49, C41, C2 or C50 in 25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2, 0.1% BSA) at a concentration of 2.5 μg ml−1 was added into each well and incubated for 1 h at RT. The peptide was washed four times followed by the addition of 100 μl of HRP goat anti-mouse IgG (1:3,000; Biolegend). After six washes, 50 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) high sensitive substrate solution (Biolegend) was added into each well. The plates were incubated for 3–5 min before analysing by using a Benchmark PlusMicroplate Spectrophotometer (BioRad Laboratories Inc) at 370 nm.

Live video microscopy

For live video microscopy23, we used an Axiovert 200 M cell observer with a 37 °C chamber with a continuous supply of 5% CO2. Five to ten percentage of the late-schizont stage parasites were diluted at 1:100 in complete RPMI. Live video was performed using 35 mm glass bottom dishes. The video was captured in the presence or absence of PfRH1 mAbs (C2, C41, C49 and C50) at a final concentration of 0.2 mg ml−1. AxioCam HRm camera and Axiovision software, or Cool SNAP camera and MetaMorph software, were used for image acquisition. The video files were prepared using Image J.

Isolation of P. falciparum merozoites

Purified P. falciparum schizonts were resuspended in warm complete RPMI and allowed to rupture and release merozoites over a period of 2 h at 37 °C. Cultures containing unruptured schizonts and released merozoites were centrifuged at 2,200 r.p.m. (942 g) on an Eppendorf 5810R centrifuge for 3 min to separate released merozoites from unruptured schizonts and uninfected erythrocytes. Supernatants containing free merozoites were then centrifuged at 5,000 r.p.m. (4,500 g, Sigma 3K15) for 3 min to collect merozoites. The merozoites were immediately resuspended in warm complete RPMI medium for further studies.

Viability assay of free merozoites

Erythrocyte invasion assays were performed in parallel to assess the viability of isolated free merozoites tested for Ca2+ measurement. After 24–30 h post-invasion, newly invaded ring-infected erythrocytes were scored by Giemsa (Sigma, USA) staining. Invasion rates were determined as (%) parasitemia. Data were shown from three biological replicates.

Kinetics of merozoite invasion by heparin treatment

To define the kinetics of merozoite invasion, the invasion inhibitor heparin was used to block merozoite invasion29. In brief, freshly isolated T994 merozoites were allowed to invade erythrocytes in the 96-well plate followed by addition of heparin (200 μg ml−1) at different time points (2–10 min with 2 min interval) to inhibit further invasion. After the final time point, cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 40 h. The plate was centrifuged at 2,200 r.p.m. (942 g) for 3 min to separate free merozoites from uninfected and infected erythrocytes. The culture was washed with complete RPMI twice and stained with 40 nM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Molecular Probes, USA). The resulting parasitemias were analysed by flow cytometry. The cells were first gated by size in SSC/FSC, followed by further gating in FSC-A/FSC-H to discriminate doublets from single cells. Uninfected erythrocytes were gated as baseline by DAPI fluorescence in FSC-A/DAPI-A. The proportion of merozoites that have invaded with increasing time is shown as % of maximum invasion obtained in uninhibited culture. Data shown were from three biological replicates. Experimental data were presented as the mean±s.e.m.; n=3.

Real-time Ca2+ measurement in merozoites during invasion

Fresh isolated merozoites were preloaded with 6 μM Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen) in complete RPMI at 37 °C for 20 min. Preloaded merozoites were washed twice with warm complete RPMI and then immediately resuspended in fresh erythrocytes or in the presence of 4 μM Cyto D, C41, C2, C41 Fab fragment or EBA175 mAbs R215 at 0.2 mg ml−1, or 10 μM Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (Calbiochem, USA), or pretreated with 50 μM Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM (Calbiochem, USA) followed by A23187 (ref. 28), and cultured in Greiner 96 Black Flat Bottom Polystyrol plates. Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels during merozoite invasion were timely assessed using a fluorescence plate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan). Fluorescence intensity was measured for 600 s with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 530 nm by TECAN-i-control 1.8.20.0 software. The maximum increase of Ca2+ green fluorescence (F) during a period of 600 s after the start of the stimulation was normalized to the fluorescence intensity before stimulation (F0). Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels (ΔF(t)) were expressed as changes in fluorescence intensity as a percentage of the starting fluorescence levels: ΔF(t)=(F−F0)/F0 where F=fluorescence intensity (t), F0=starting fluorescence signal. The total changes of Ca2+ levels (≤ΔF(t)) in merozoites along the 600 s were summed up and plotted against time (s). Data shown were from three biological replicates. Experimental data were presented as the mean±s.e.m. TECAN scanning was performed at 37 °C.

Flow cytometry Ca2+ measurement in merozoites during invasion

Isolated T994 merozoites were preloaded with Fluo-4 AM as well as labelled with DAPI as described above, followed by incubation with fresh warm erythrocytes containing 4 μM Cyto D in the absence and presence of mAb C41 (0.2 mg ml−1). The culture was immediately processed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Merozoites that are invading will be arrested by Cyto D after junction formation, whereas merozoites in the presence of inhibitory antibodies will either detach or remain attached to the RBC without forming a junction. Each culture was excited with light at 488 and 355 nm, and fluorescence signal was detected with a 530/30 and 440/40 nm band pass filters. In each experiment, data were acquired for~20,000 DAPI (+) merozoites with the same settings for each condition. A histogram representing two distinct cell populations among these 20,000 cells indicates free merozoites and RBC-bound merozoites. Preloaded merozoites alone were measured as the baseline for detection of Fluo-4 AM signals. The cells were gated by FSC-A versus Fluo-4 AM mean fluorescence (MF). We observed the % parent population of attached merozoites with increasing Ca2+ signal from the culture in the absence (positive) or presence of C41 (C41) and investigated the effect of C41 on signalling during invasion. Data were analysed by using BD FASCDiva software. (%) Inhibition of attached merozoites=(1−% parent population (C41)/% parent population (positive)) × 100. (%) Decrease of Fluo-4 AM mean fluorescence (MF)=(1−MF (C41)/MF (positive)) × 100. Data shown are from three biological replicates. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ levels on free merozoites

Merozoites preloaded with Fluo-4 AM as described above were immediately resuspended in complete RPMI only or treated with 10 μM A23187 for 15 min at 37 °C with or without pretreatment with 50 μM BAPTA-AM for 15 min at 37 °C (ref. 28). Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels were assessed using flow cytometry. Preloaded merozoites in complete RPMI were measured as baselines. Merozoites were excited at 488 nm, and fluorescence signal is detected with a 530/30 nm band pass filter for periods of 2 min on BD LSR II (BD Biosciences). Merozoites were gated on the basis of their forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC). Data were evaluated by using dot plot of Fluo-4 AM mean fluorescence (MF) versus time using BD FACSDiva software to visualize the cytosolic Ca2+ levels in merozoites. The effect of BAPTA-AM (MFBAPTA-AM) on free merozoites Ca2+ signalling was compared with that of A23187 (MFA23187). (%) Inhibition of BAPTA-AM=(1−(MFBAPTA-AM/MFA23187)) × 100. Data shown are from three biological replicates. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Immunofluorescence assays and microscopy

Synchronized late-stage schizonts were smeared and air-dried followed by fixation with acetone (Merck) for 5 min at RT. Smears were incubated with PfRH1 mAbs (1:800) and co-incubated with rabbit α-EBA175 (1:800) for 1 h in 3% BSA/PBS buffer, followed by three times for 5 min washes in 1 × PBS. They were then incubated with a mixture of Alex Flour 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) and Alex Flour 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibodies (1:1,000, respectively, Molecular Probe) for 1 h. Slides were washed in 1 × PBS for three times for 5 min. Slides were air-dried, mounting medium containing DAPI was applied (Vector laboratories), and the coverslips were sealed. The fluorescence images were captured using a LSM510 Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Immunofluorescence assay for merozoites

Isolated T994 merozoites were incubated with or without streptolysin O (SLO, Sigma)51. The culture was washed three times with incomplete RPMI and then fixed with 1% p-formaldehyde (Sigma) for 45 min at RT followed by centrifugation at 5,000 r.p.m. (4,500 g, Sigma 3K15) for 3 min. After two washes, the culture was incubated with either rabbit α-Nucleoporin 100 (α-Nup 100, 1:500), a nuclear periphery marker, or rabbit α-acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys9) antibody (α-H3K9ac, 1:500, Millipore), a histone marker32 for 45 min at 37 °C. The culture was washed three times in incomplete RPMI followed by incubation with Alex Flour 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:1,000) or Alex Flour 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:1,000) together with DAPI for 45 min at RT. The culture was washed three times and then applied to the slides. The images were captured by Nikon TE2000-U Inverted Fluorescence Microscopy.

Detection of EBA175 on merozoite surface by fluorescence-based methods

Isolated merozoites from T994 and T994ΔRH1 were incubated with fresh erythrocytes containing 4 μM Cyto D in the absence and presence of mAb C41 (0.2 mg ml−1) at 37 °C for 20 min followed by incubation with or without Streptolysin O (SLO, Sigma)51. The culture was washed three times with 1% BSA/PBS and then fixed with 1% p-formaldehyde (Sigma) for 45 min at RT followed by centrifugation at 5,000 r.p.m. (4,500 g, Sigma 3K15) for 3 min. After two washes, the culture was incubated with rabbit α-EBA175 (1:500) for 45 min at 37 °C. The culture was washed three times with incomplete RPMI followed by incubation with Alex Flour 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:1,000) together with DAPI for 45 min at RT. The culture was washed three times with incomplete RPMI. The culture was finally resuspended in 100 μl complete RPMI and transferred into Greiner 96 Black Flat Bottom Polystyrol plates for analysis by using a fluorescence plate reader using the program TECAN-i-control 1.8.20.0. The duplicated culture (except SLO treated culture) was also tested using rabbit α-MSP1 (1:1,000, MR4) followed by incubation with Alex Flour 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:1,000) together with DAPI. The samples were applied to the slides. The images were captured by Nikon TE2000-U Inverted Fluorescence Microscopy. To further confirm and quantify the effect of inhibitory mAbs C41 on the surface expression of EBA175, fluorescence intensity was also measured by using a fluorescence plate reader. Fluorescence signal of EBA175 (FEBA175) was excited at 488 nm and emitted at 519 nm, MSP1 surface staining (FMSP1) was excited at 590 nm and emitted at 617 nm and nuclear signal (FEBA175-DAPI or FMSP1-DAPI) was excited at 375 nm and emitted at 461 nm. Fluorescence signal was normalized to nuclear DAPI signal as follows: EBA175 ratio=FEBA175/FEBA175-DAPI and MSP1 ratio=FMSP1/FMSP1-DAPI. Protein expression on merozoite surface in the presence of mAbs C41 was compared with its control of the same culture incubated in the absence of C41. Surface expression inhibition efficiencies were determined as follows: (%) inhibition of EBA175 surface expression=(1−EBA175 ratio (C41)/EBA175 ratio (control)) × 100 and (%) inhibition of MSP1 surface expression=(1−MSP1 ratio (C41)/MSP1 ratio (control)) × 100. Protein expression on merozoite permeabilized with SLO in the presence of mAbs C41 were compared with its control of the same culture in the absence of C41. EBA175 expression inhibition efficiencies were determined as follows: (%) inhibition of EBA175 expression=(1−EBA175 ratio (C41−SLO)/EBA175 ratio (control−SLO)) × 100. Data shown are from three biological replicates. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Detection of EBA175 on merozoite surface by flow cytometry

The culture prepared for detection of EBA175 by fluorescence microscopy, mentioned above, was resuspended in complete RPMI and used for analysis by BD LSR II (BD Biosciences). In each experiment, data were acquired for 5,000 DAPI (+) merozoites with the same settings for each condition. A histogram representing two distinct cell populations among these 5,000 cells indicates free merozoites (Free Mero) and RBC-bound merozoites (Attached Mero+RBCs). We observed these two populations individually and investigated the effect of C41 on EBA175 surface expression in T994. Each culture was excited with light at 488 and 355 nm, and fluorescence signal was detected with 530/30 and 440/40 nm band pass filters. The cells were gated on the basis of their FSC and SSC. Data were analysed using BD FASCDiva software. Histograms showing logarithmic green fluorescence intensities (FITC-A) versus blue fluorescence intensities (DAPI-A) were plotted. For each experiment, fixed untreated cultures were stained only with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG to establish background staining and to set up a gate before calculating the percentage of FITC(+) merozoites (that is, those expressing EBA175 on their surface) in the parent population. EBA175 surface expression on junction-arrested merozoites in the presence of mAb C41 was compared with a positive control in the absence of C41. EBA175 surface expression inhibition efficiencies were determined as follows: (%) inhibition of EBA175 surface expression=(1−% parent population (C41)/% parent population (positive)) × 100. Data shown are from four biological replicates. Experimental data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparison was done using one-way ANOVA as appropriate. The significance level was set at P<0.05. The P-value is provided for some individual experiments.

Raw data of absolute measurement Ca2+ signalling

Absolute measurement raw data of all Ca2+ signalling experiments have been provided in Supplementary Data 1–6.

Author contributions

X.G. and K.G. contributed extensively to the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. X.G. and P.R.P. conceived the experiments. S.S.L.Y. performed the epitope mapping experiment and analysed the data. P.R.P. supervised the project, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Gao, X. et al. Triggers of key calcium signals during erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 4:2862 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3862 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Tables S1-S5

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3a

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3b

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3c

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3d

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 5b

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Supplementary Figure S5a

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C49.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C41.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C2.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C50.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C49.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C41.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the blood donors. We thank Dr. Tim Gilberger and his laboratory for technical support of live video microscopy. We thank MR4 for providing us with rabbit anti-EBA175 polyclonal antibodies (contributed by Professor John Adams) and monoclonal antibody g12 (contributed by M. Wiser). We thank Dr. Mike Blackman for PfMSP1 antibodies. T994ΔRH1 and anti-nucleoporin 100 (Nup 100) antibodies were kind gifts from Dr. Alan Cowman, Australia. We also thank Dr. David Narum for anti-EBA175 mAb R215. This research is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under its Individual Research Grant (NMRC/1308/2011) and Singapore Biomedical Research Council (08/1/22/19/581).

References

- Cowman A. F. & Crabb B. S. Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell 124, 755–766 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum J., Gilberger T. W., Frischknecht F. & Meissner M. Host-cell invasion by malaria parasites: insights from Plasmodium and Toxoplasma. Trends Parasitol. 24, 557–563 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur D. & Chitnis C. E. Molecular interactions and signalling mechanisms during erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 422–428 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunalan K., Gao X., Yap S. S., Huang X. & Preiser P. R. The role of the reticulocyte-binding-like protein homologues of Plasmodium in erythrocyte sensing and invasion. Cell Microbiol. 15, 35–44 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis C. E. & Miller L. H. Identification of the erythrocyte binding domains of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium knowlesi proteins involved in erythrocyte invasion. J. Exp. Med. 180, 497–506 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum J. et al. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 5 - an essential adhesin involved in invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol. 39, 371–380 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X. et al. Antibodies targeting the PfRH1 binding domain inhibit invasion of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. PLoS Pathog 4, e1000104 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur D., Singh S., Jiang L., Diouf A. & Miller L. H. Recombinant Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte homology protein 4 binds to erythrocytes and blocks invasion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17789–17794 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner J. C., Vargas-Serrato E., Huber C. S., Galinski M. R. & Barnwell J. W. A Plasmodium falciparum homologue of Plasmodium vivax reticulocyte binding protein (PvRBP1) defines a trypsin-resistant erythrocyte invasion pathway. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1571–1581 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahar T. et al. Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte binding-like homologue protein 2 (PfRH2) is a key adhesive molecule involved in erythrocyte invasion. PLoS One 6, e17102 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham W. H. et al. Antibodies to reticulocyte binding protein-like homologue 4 inhibit invasion of Plasmodium falciparum into human erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 77, 2427–2435 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triglia T. et al. Identification of proteins from Plasmodium falciparum that are homologous to reticulocyte binding proteins in Plasmodium vivax. Infect. Immun. 69, 1084–1092 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M., Lustigman S., Montero E., Oksov Y. & Lobo C. A. PfRH5: a novel reticulocyte-binding family homolog of Plasmodium falciparum that binds to the erythrocyte, and an investigation of its receptor. PLoS One 3, e3300 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham W. H. et al. Complement receptor 1 is the host erythrocyte receptor for Plasmodium falciparum PfRh4 invasion ligand. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17327–17332 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnier C. et al. Basigin is a receptor essential for erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 480, 534–537 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinski M. R., Medina C. C., Ingravallo P. & Barnwell J. W. A reticulocyte-binding protein complex of Plasmodium vivax merozoites. Cell 69, 1213–1226 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinski M. R., Xu M. & Barnwell J. W. Plasmodium vivax reticulocyte binding protein-2 (PvRBP-2) shares structural features with PvRBP-1 and the Plasmodium yoelii 235 kDa rhoptry protein family. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 108, 257–262 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. P. et al. Targeted deletion of Plasmodium knowlesi Duffy binding protein confirms its role in junction formation during invasion. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1925–1934 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J. et al. Molecular mechanism for switching of P. falciparum invasion pathways into human erythrocytes. Science 309, 1384–1387 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopineau M., Maurel M. C., Combarnous Y. & Durand P. Topography of equine chorionic gonadotropin epitopes relative to the luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor interaction sites. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 92, 229–239 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imakiire T. et al. Generation, immunologic characterization and antitumor effects of human monoclonal antibodies for carcinoembryonic antigen. Int. J. Cancer 108, 564–570 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P. J. et al. Identification and functional characterization of two distinct epitopes on the human T cell surface protein Tp50. J. Immunol. 131, 180–185 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treeck M. et al. Functional analysis of the leading malaria vaccine candidate AMA-1 reveals an essential role for the cytoplasmic domain in the invasion process. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000322 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triglia T., Tham W. H., Hodder A. & Cowman A. F. Reticulocyte binding protein homologues are key adhesins during erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Cell Microbiol. 11, 1671–1687 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triglia T. et al. Plasmodium falciparum merozoite invasion is inhibited by antibodies that target the PfRh2a and b binding domains. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002075 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunalan K., Gao X., Liew K. J. & Preiser P. R. Differences in erythrocyte receptor specificity of different parts of the Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte binding protein homologue 2a. Infect. Immun. 79, 3421–3430 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. H., Aikawa M., Johnson J. G. & Shiroishi T. Interaction between cytochalasin B-treated malarial parasites and erythrocytes. Attachment and junction formation. J. Exp. Med. 149, 172–184 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Alam M. M., Pal-Bhowmick I., Brzostowski J. A. & Chitnis C. E. Distinct external signals trigger sequential release of apical organelles during erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000746 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M. J. et al. Isolation of viable Plasmodium falciparum merozoites to define erythrocyte invasion events and advance vaccine and drug development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14378–14383 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim B. K. et al. Delineation of stage specific expression of Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 by biologically functional region II monoclonal antibodies. PloS One 6, e18393 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge I., Benting J., Bhakdi S. & Lingelbach K. Protein sorting in Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells permeabilized with the pore-forming protein streptolysin O. Biochem. J. 315, (Pt 1): 307–314 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz J. et al. Potential epigenetic regulatory proteins localise to distinct nuclear sub-compartments in Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol. 40, 109–121 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erxleben C. et al. Microdomain Ca2+ activation during exocytosis in Paramecium cells. Superposition of local subplasmalemmal calcium store activation by local Ca2+ influx. J. Cell Biol. 136, 597–607 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers V. B. & Sibley L. D. Sequential protein secretion from three distinct organelles of Toxoplasma gondii accompanies invasion of human fibroblasts. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 73, 114–123 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers V. B. & Sibley L. D. Mobilization of intracellular calcium stimulates microneme discharge in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 421–428 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson S., Charron A. J. & Sibley L. D. Toxoplasma evacuoles: a two-step process of secretion and fusion forms the parasitophorous vacuole. EMBO J. 20, 3132–3144 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besteiro S., Michelin A., Poncet J., Dubremetz J. F. & Lebrun M. Export of a Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry neck protein complex at the host cell membrane to form the moving junction during invasion. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000309 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett J. L. & Sibley L. D. Intracellular calcium stores in Toxoplasma gondii govern invasion of host cells. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3009–3016 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell A. et al. A DOC2 protein identified by mutational profiling is essential for apicomplexan parasite exocytosis. Science 335, 218–221 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triglia T., Duraisingh M. T., Good R. T. & Cowman A. F. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 1 is required for sialic acid-dependent invasion into human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 162–174 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W. & Jensen J. B. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science 193, 673–675 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambros C. & Vanderberg J. P. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J. Parasitol. 65, 418–420 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aley S. B., Sherwood J. A., Marsh K., Eidelman O. & Howard R. J. Identification of isolate-specific proteins on sorbitol-enriched Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes from Gambian patients. Parasitology 92, (Pt 3): 511–525 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner S., Breuer W. V., Ginsburg H., Aley S. B. & Cabantchik Z. I. Characterization of permeation pathways in the plasma membrane of human erythrocytes infected with early stages of Plasmodium falciparum: association with parasite development. J. Cell Physiol. 125, 521–527 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidrich H. G. Isolation and functional characterization of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens. Biol. Cell 64, 205–214 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman M. J. Purification of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites for analysis of the processing of merozoite surface protein-1. Methods Cell Biol. 45, 213–220 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S., Shimura K., Ito S. & Minami T. Babesia ovata: isolation from erythrocytes and development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibodies. Parasitol. Res. 78, 684–688 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss C. et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals new insights into erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Cell Proteomics 11, 010645 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser M. F. & Plitt B. Plasmodium berghei, P. chabaudi, and P. falciparum: similarities in phosphoproteins and protein kinase activities and their stage specific expression. Exp. Parasitol. 64, 328–335 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim B. K., Toyoshima T., Haynes J. D. & Aikawa M. Localization of the 175-kilodalton erythrocyte binding antigen in micronemes of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 51, 157–159 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niang M., Yan Yam X. & Preiser P. R. The Plasmodium falciparum STEVOR multigene family mediates antigenic variation of the infected erythrocyte. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000307 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Tables S1-S5

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3a

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3b

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3c

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 3d

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Figure 5b

Raw data for calcium signalling experiments described in Supplementary Figure S5a

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C49.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C41.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C2.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C50.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C49.

Live video microscopy of erythrocytes being invaded by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites in the presence of anti-PfRH1 mAb C41.