Abstract

Objective

To assess the reliability and convergent validity of two outcome instruments for assessing cutaneous sarcoidosis: Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Instrument (CSAMI) and Sarcoidosis Activity and Severity Index (SASI).

Design

Cross-sectional study evaluating cutaneous sarcoidosis disease severity using CSAMI, SASI, and Physician's Global Assessment (PGA) as reference.

Setting

Cutaneous sarcoidosis clinic.

Participants

8 dermatologists evaluated 11 patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes: Inter- and intra-rater reliability and convergent validity. Secondary outcomes: Correlation with quality of life measures and time required for completion.

Results

All instruments demonstrated good to excellent intra-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability was excellent for CSAMI Activity scores (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66-0.94), and fair to poor for CSAMI Damage (0.42; 0.21-0.72), modified Facial SASI (0.40; 0.17-0.72), and PGA scores (0.40; 0.18-0.70). CSAMI Activity, Damage, and modified Facial SASI scores all demonstrated convergent validity with statistically significant correlations with PGA scores. Trends for correlations were seen between CSAMI scores and specific Skindex-29 quality of life domains. While CSAMI required longer time to complete than SASI, both were scored within adequate time for use in clinical trials.

Conclusions

CSAMI appears to be a reliable and valid outcome instrument to measure cutaneous sarcoidosis and may capture a wide range of body surface and cutaneous morphologies. Future research is necessary to demonstrate its sensitivity to change and to confirm its correlation with quality of life measures.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is an uncommon multisystem disease of unknown etiology characterized by granulomatous infiltrates, with cutaneous involvement occurring in 25-30% of cases1. Recent advances in the pathogenesis of cutaneous sarcoidosis have resulted in broadening therapeutic options; nonetheless, most treatment recommendations are currently based on anecdotal reports or small case series, with a general lack of high-quality evidence for clinical efficacy2. The development and validation of standardized disease severity instruments are required for rigorous clinical research and evidence-based dermatology3.

To our knowledge, no gold-standard instrument has been established for the objective assessment of cutaneous sarcoidosis severity. Many previous studies on sarcoidosis treatments relied on subjective assessments of photographs or clinical descriptors, making objective interpretation of response challenging4-7. The Sarcoidosis Activity and Severity Index (SASI) was the first outcome instrument proposed to measure cutaneous sarcoidosis severity and has been incorporated into clinical trials8, 9. SASI has been reported to be reliable; however, its construct validity and other psychometric properties have not been reported.

In this study, we propose a novel instrument, the Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Instrument (CSAMI), designed to capture disease activity and morphologic type for use in clinical trials and prognostic studies. Our primary objectives were to assess intra- and inter-rater reliability and convergent validity of CSAMI and SASI as compared to the Physician's Global Assessment (PGA) as reference. Our secondary objectives were to evaluate the instruments’ correlations with quality of life measures and the time required for their completion.

Methods

The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and reported based on the STROBE statement10. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Physician Participants

Eight dermatologists with experience diagnosing and managing patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, including 7 board-certified dermatologists and 1 dermatology chief resident, were invited to complete this 1-day study in June 2012. All completed a training session with images of cutaneous sarcoidosis to become familiarized with the three outcome instruments and their scoring methods. Questions regarding the outcome instruments were addressed prior to patient evaluation.

Patient Participants

Eleven patients were recruited from the cutaneous sarcoidosis clinic at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania via telephone. Eligible patients had clinical and/or pathological evidence consistent with the diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Patients were selected purposively by the principal investigator to include a wide range of sarcoidosis presentation and severity. On the study day, all patients completed three surveys on the impact of cutaneous sarcoidosis on health-related quality of life.

Study Design

Patients were randomly divided into two groups: physicians scored one group of patients using CSAMI first, followed by SASI and PGA, and the other group using SASI first, then CSAMI and PGA. Physicians were instructed to document their start and stop times for each instrument. Physicians rotated among individual patient rooms, rating each of 11 patients using all three instruments, and then re-rating 3 patients. Re-rating was carried out based on patient availability: all but 1 patient were re-rated, with 3 patients re-rated by 1 physician, 2 patients re-rated by 2 physicians, 3 patients re-rated by 3 physicians, and 2 patients re-rated by 4 physicians.

Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Instrument (CSAMI)

CSAMI was developed by the principal investigator (MR) to capture disease activity and morphology after reviewing relevant literature on cutaneous sarcoidosis and outcome instruments in dermatology11, 12. Lessons learned through developing cutaneous scoring instruments for lupus, dermatomyositis, and pemphigus were incorporated into instrument design. Face validity, or the extent to which CSAMI appeared to represent its underlying construct of cutaneous sarcoidosis severity, was established: a preliminary instrument was reviewed by multiple authors for its format and content (EJK, JT, JMG, VPW) and piloted in clinic (HY, EJK, KW, MR) with changes made to enhance clarity and usability.

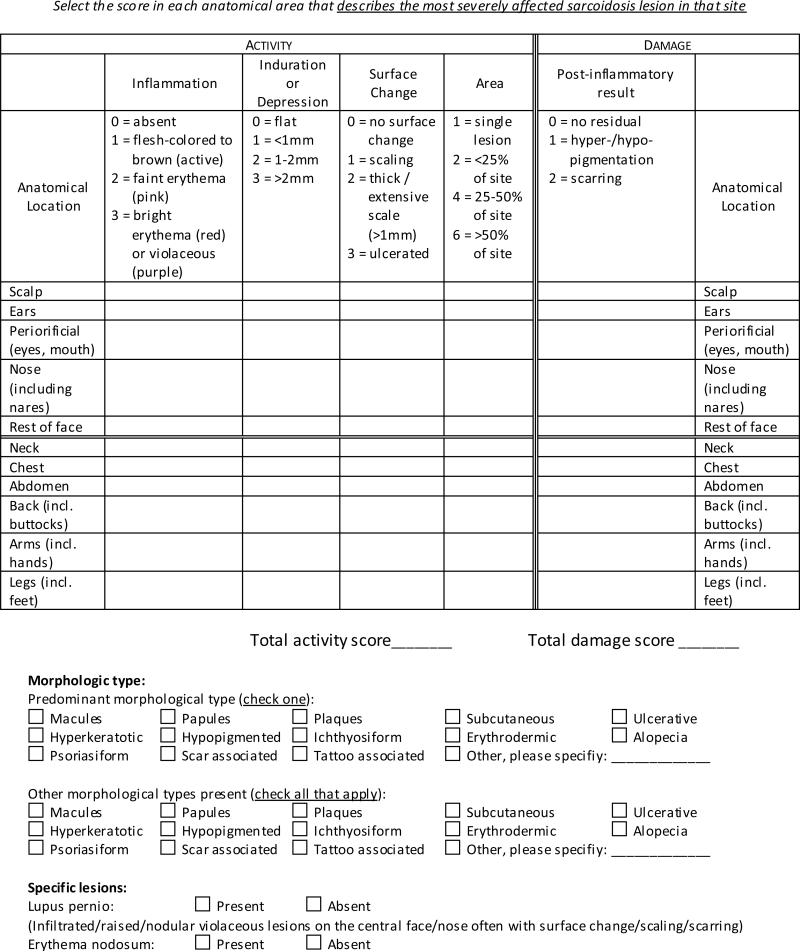

The final CSAMI consists of two scores measuring disease activity and damage done by the disease (Figure 1). Activity and Damage scales are considered separately to aid the instrument in detecting changes in disease activity, rather than remaining stable as one conglomerate outcome as inflammatory activity subsides and chronic damage develops11. Activity is scored based on inflammation, induration and/or depression, surface changes such as scaling and ulceration, and area of involvement. Damage is scored based on dyspigmentation and scarring. Clinical signs are documented according to the worst affected lesion within each anatomic area and summed, with maximal score ranges of 0-165 for Activity and 0-22 for Damage. In addition, CSAMI assesses morphologic types of cutaneous sarcoidosis lesions, documenting both a predominant type and all other types present. It also examines the presence of specific lesions for sarcoidosis, including lupus pernio and erythema nodosum.

Figure 1.

Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Index.

Sarcoidosis Activity and Severity Index (SASI)

SASI was the first proposed outcome instrument for cutaneous sarcoidosis8, 9. It evaluates 4 features for each of 4 facial quadrants and the nose: erythema, induration, and desquamation, each ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (very severe), and an area score ranging from 0 (0%) to 6 (90-100%). Thus SASI produces 5 separate sets of scores per patient. The Facial SASI score weighs these SASI components to provide a composite index for the face; however, it requires re-scoring for the lower face and the nose. SASI has been previously modified and incorporated into clinical trials8. Similarly, the Facial SASI was modified here to simplify its computation: the sums of the erythema, induration and desquamation scores for each quadrant of the face and the nose were multiplied by their respective area scores and then averaged with equal weight on all 5 regions. The maximal range of modified Facial SASI scores is 0 to 72.

Physician's Global Assessment (PGA)

PGA is a visual analog scale ranging from 0 (perfect health) to 10 (worst skin condition imaginable). This form of PGA has been used to rate the overall impression of disease severity in instrument validation studies for dermatomyositis and pemphigus13, 14. Since there is no gold-standard instrument for cutaneous sarcoidosis against which we could evaluate criterion validity, we used the PGA to assess convergent validity, expecting positive correlations between both CSAMI and modified Facial SASI with PGA in reflecting the overall level of disease severity.

Quality of Life Surveys

Each patient completed 3 self-administered, health-related quality of life surveys: Skindex-29, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire (SHQ). Skindex-29 and DLQI are validated dermatology-specific quality of life instruments widely used in the literature. Skindex-29 is a 29-item survey with 3 domains: Emotions, Symptoms, and Functioning, each ranging from 0 (no effect on quality of life) to 100 (effect always experienced)15. DLQI is a 10-item survey on the impact of skin diseases, with scores ranging from 0 (no effect on patient's life) to 30 (extremely large effect)16. SHQ is a 29-item validated sarcoidosis-specific survey assessing the impact of sarcoidosis involvement of multiple organ systems, summarized by a total score ranging from 1 (effect experienced all of the time) to 7 (none of the time)17. However, SHQ contains only one question pertinent to the skin and may not capture the full impact on skin-related quality of life.

Statistical analysis

Scores from each outcome instrument were summarized descriptively. Skewness and kurtosis test was used to assess normality of score distributions. Reliability was analyzed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), a more robust measure of agreement than other statistics18. Intra-rater and inter-rater ICCs were respectively calculated using one-way and two-way random-effects models, and interpreted by the following: <0.4 is poor, 0.4–0.75 is fair to good, and >0.75 is excellent18, 19. Since SASI provides multiple scores per patient, its intra- and inter-rater reliability were calculated by each facial region of each patient9. All other instruments, including the modified Facial SASI, were calculated by patient. SASI scores from one patient with no facial involvement were excluded to minimize bias in reliability analysis. Reliability of CSAMI morphology types was analyzed using κ and interpreted by the following: 0-0.2 is slight agreement, 0.2-0.4 is fair, 0.4-0.6 is moderate, 0.6-0.8 is substantial, and >0.8 is almost perfect20-22.

Construct validity refers to the degree to which one measure correlates to another measure, with which it theoretically should correlate. Convergent validity, a form of construct validity that compares against a similar construct of disease severity, was assessed in terms of the correlation between both CSAMI and modified Facial SASI with the PGA using Spearman's ρ. Mixed-effects linear regression was used to confirm the linearity of these associations, adjusting for inter- and intra-rater variations as random effects and PGA scores as a fixed effect. Construct validity was also evaluated in terms of the correlation between mean instrument scores and quality of life metrics, using Pearson's r or Spearman's ρ, as appropriate.

Time required for instrument scoring was calculated from instrument start and end times, rounded up by the minute, and compared using 2-tailed t-tests. Physicians did not calculate the CSAMI Activity and Damage scores or modified Facial SASI score while evaluating patients; thus the scoring time did not reflect time required for manual calculation. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Sample size

We planned to have 12 patients with 8 physician ratings per patient to detect an inter-rater ICC of 0.7 with 80% power, when the ICC is 0.4 under the null hypothesis, using an F-test with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Eleven patients were available and participated in this study. Their mean (SD) age was 52.5 (7.6) years; 2 patients were male. Nine patients were African American while 2 were Caucasian. Sarcoidosis involvement was documented in a mean (SD) of 3 (1) organ systems, with skin and lung involvement seen in all patients. A wide spectrum of skin disease severity was represented as demonstrated by the range of PGA scores (Table 1). Patients’ cutaneous morphologies and anatomic area affected, as measured by CSAMI, as well as current treatments were shown in Table 2. CSAMI and SASI scores had positively skewed distributions, while PGA scores were approximately normally distributed.

Table 1.

Disease severity scores of patient participants.

| Range (Max. Range) | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| CSAMI Activity | 4-70 (0-165) | 23 (17-38) |

| Inflammation | 1-26 (0-33) | 8 (5-13) |

| Induration / Depression | 0-19 (0-33) | 5 (3.5-8) |

| Surface changes | 0-11 (0-33) | 1 (0-2) |

| Area | 2-22 (0-66) | 9 (7-14) |

| CSAMI Damage | 0-14 (0-22) | 2 (1-3) |

| Modified Facial SASIa | 0-18.4 (0-72) | 4.6 (3.1-7.7) |

| SASI Componentsa | ||

| Erythema | 0-4 (0-4) | 1 (0-2) |

| Induration | 0-4 (0-4) | 1 (0-2) |

| Desquamation | 0-3 (0-4) | 0 (0-1) |

| Area | 0-6 (0-6) | 1 (1-2) |

| PGA | 2-8 (0-10) | 5 (4-6) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; CSAMI, Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Instrument; SASI, Sarcoidosis Activity and Severity Index; PGA, Physician's Global Assessment.

Re-scored disease severity scores for reliability analysis in selected patients were excluded for baseline descriptions.

Table 2.

Cutaneous sarcoidosis characteristics and treatment history.

| Patient | Morphologya | Anatomic Areasa | Current Treatmentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Papules, Plaques, Alopecia | Scalp, Ears, Periorificial, Nose, Rest of face, Neck | Hydroxychloroquine, Minocycline, Topical tacrolimus |

| 2 | Papules, Plaques | Periorificial, Nose | Hydroxychloroquine, Topical tretinoin |

| 3 | Macules, Papules, Plaques, Hyperkeratotic, Other (Patch) | Scalp, Ears, Periorificial, Nose, Rest of face, Neck, Chest, Abdomen, Back, Arms | Adalimumab |

| 4 | Papules, Plaques | Ears, Periorificial, Nose, Rest of face | None |

| 5 | Macules, Papules, Plaques, Hyperkeratotic, Psoriasiform | Scalp, Ears, Periorificial, Nose, Rest of face, Neck, Chest, Abdomen, Back | Mycophenolate Mofetil, Topical tacroliumus, Topical steroid |

| 6 | Papules, Plaques, Subcutaneous | Ears, Periorificial, Nose, Rest of face, Neck, Chest, Abdomen, Back, Arms, Legs | Methotrexate |

| 7 | Papules, Plaques, | Nose | Chloroquine, Minocycline, Topical steroid |

| 8 | Macules, Papules, Plaques, Other (Patch) | Abdomen, Back, Arms, Legs | Topical steroid, topical tacrolimus |

| 9 | Papules, Plaques | Periorificial, Nose, Arms | Minocycline, Hydroxychloroquine, Quinacrine |

| 10 | Papules, Plaques | Ears, Periorificial, Nose, Rest of face, Chest | Hydroxychloroquine, Minocycline, Topical steroid |

| 11 | Papules, Plaques | Ears, Periorificial, Nose, Rest of face | Chloroquine, Minocycline |

Morphology and anatomic area involvement are documented using the CSAMI as agreed upon by 2 or more dermatologists.

Topical steroids vary depending on site of involvement, disease extent, lesion morphology, and patient vehicle preference.

Intra- and Inter-rater Reliability

Excellent intra-rater reliability was demonstrated with CSAMI Activity, SASI components, modified Facial SASI, and PGA scores, while CSAMI Damage scores had good intra-rater reliability (Table 3). CSAMI Activity scores demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability; in contrast, CSAMI Damage, SASI components, modified Facial SASI and PGA scores had inter-rater reliability ranging from fair to poor.

Table 3.

Intra- and inter-rater reliability and convergent validity of cutaneous sarcoidosis severity measures

| Intra-rater reliability | Inter-rater reliability | Convergent validity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICC (95% CI) | ICC (95% CI) | Spearman's ρ (95% CI) | |

| CSAMI Activity | 0.84 (0.66 – 0.93) | 0.82 (0.66 – 0.94) | 0.51 (0.36 – 0.64) |

| Inflammation | 0.85 (0.69 – 0.93) | 0.85 (0.70 – 0.95) | 0.44 (0.27 – 0.58) |

| Induration / Depression | 0.81 (0.62 – 0.91) | 0.59 (0.36 – 0.83) | 0.50 (0.35 – 0.63) |

| Surface changes | 0.82 (0.63 – 0.92) | 0.74 (0.53 – 0.90) | 0.40 (0.23 – 0.55) |

| Area | 0.72 (0.46 – 0.87) | 0.76 (0.57 – 0.91) | 0.51 (0.35 – 0.63) |

| CSAMI Damage | 0.70 (0.42 – 0.86) | 0.42 (0.21 – 0.72) | 0.23 (0.04 – 0.40) |

| Modified Facial SASI | 0.90 (0.77 – 0.96) | 0.40 (0.17 – 0.72) | 0.43 (0.27 – 0.57) |

| SASI components | |||

| Erythema | 0.83 (0.76 – 0.88) | 0.55 (0.43 – 0.68) | N/Aa |

| Induration | 0.74 (0.64 – 0.81) | 0.57 (0.45 – 0.69) | N/Aa |

| Desquamation | 0.80 (0.72 – 0.86) | 0.54 (0.42 – 0.66) | N/Aa |

| Area | 0.87 (0.82 – 0.91) | 0.81 (0.74 – 0.88) | N/Aa |

| PGA | 0.82 (0.62 – 0.92) | 0.40 (0.18 – 0.70) | N/A |

Abbreviations: ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; CSAMI, Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Instrument; SASI, Sarcoidosis Activity and Severity Index; PGA, Physician's Global Assessment.

Correlation between SASI component scores and PGA were not calculated since multiple SASI scores were provided per patient.

The proportional overlap of selected morphologic types demonstrated substantial intra-rater reliability (κ, 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.47-0.84) and moderate inter-rater reliability (0.46; 0.33-0.59). The predominant morphologic type selected also showed substantial intra-rater reliability (0.66; 95% CI, 0.35-0.90) and fair inter-rater reliability (0.35; 0.23-0.50). The presence of lupus pernio displayed substantial intra-rater reliability (0.74; 95% CI, 0.46-1.00) and fair inter-rater reliability (0.34; 0.15-0.55). Erythema nodosum was rated as absent in all patients.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity was assessed by correlating each instrument against PGA as the reference measure, with significant correlations expected between similar constructs of disease severity (Table 3). CSAMI Activity and modified Facial SASI scores showed moderate correlations with PGA, while Damage scores showed a weak correlation. Mixed-effects regression modeling also demonstrated that a unit increase in PGA significantly predicted linear increases in CSAMI Activity (regression coefficient β, 4.92; 95% CI, 3.30-6.54, p < 0.001), CSAMI Damage (0.59; 0.30-0.88, p < 0.001), and modified Facial SASI scores (1.14; 0.78-1.51, p < 0.001).

Construct validity with quality of life measures

Construct validity was evaluated by comparing the disease severity instruments against health-related quality of life measures, expecting positive correlations between the two. Mean (SD) of Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire (SHQ) total score was 4.1 (1.0) and of Skindex-29 Emotions, Symptoms, and Functioning domain scores were 66.2 (21.0), 47.3 (20.3), and 43.0 (21.2), respectively. Median Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score was 5 (interquartile range, 2-7). Strong to moderate correlations were demonstrated between CSAMI Activity and Damage scores with the Skindex-29 Emotions and Functioning domains, respectively (Table 4). Moderate to weak non-significant correlations were found between CSAMI with DLQI and SHQ total score, while weak to slight non-significant correlations were found between modified Facial SASI and all quality of life measures.

Table 4.

Correlation between disease severity and quality of life measures.

| Skindex-29 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson's r (95% CI) | Emotions | Symptoms | Functioning | DLQIa | SHQ Total Score |

| CSAMI Activity | 0.74 (0.26 – 0.93) | 0.29 (−0.38 – 0.76) | 0.59 (−0.02 – 0.88) | 0.35 (−0.31 – 0.79) | −0.39 (−0.80 – 0.28) |

| CSAMI Damage | 0.54 (−0.09 – 0.86) | 0.51 (−0.13 – 0.85) | 0.68 (0.13 – 0.91) | 0.29 (−0.38 – 0.76) | −0.16 (−0.69 – 0.49) |

| Modified Facial SASI | 0.15 (−0.53 – 0.71) | 0.22 (−0.47 – 0.75) | 0.24 (−0.46 – 0.76) | 0.20 (−0.50 – 0.74) | 0.13 (−0.54 – 0.70) |

| PGA | 0.47 (−0.18 – 0.84) | 0.41 (−0.25 – 0.81) | 0.38 (−0.28 – 0.80) | 0.24 (−0.42 – 0.73) | −0.18 (−0.70 – 0.47) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CSAMI, Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Instrument; SASI, Sarcoidosis Activity and Severity Index; PGA, Physician's Global Assessment; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; SHQ, Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire.

Spearman's ρ was used since DLQI scores were not normally distributed.

Clinical acceptability

Overall, CSAMI required 1.8 minutes longer on average to complete than SASI (4.5 vs. 2.7 minutes; unpaired t-test p < 0.001). Among cases that were re-rated, the mean (SD) of CSAMI scoring time decreased from 5.0 (1.7) to 3.5 (1.2) minutes from the first to the second ratings (paired t-test p < 0.001), while that of SASI decreased from 3.0 (1.0) to 2.4 (0.9) minutes respectively (paired t-test, p = 0.02). Scoring time for PGA was not assessed.

Discussion

Cutaneous sarcoidosis, like other chronic inflammatory dermatoses, may confer substantial morbidity and impairments in quality of life23, 24. However, the lack of an established and validated disease severity instrument hinders rigorous research in tracking sarcoidosis severity and evaluating therapeutic efficacy. The ideal outcome instrument should be reliable and accurate in scoring disease severity, simple to use in clinical practice, and sensitive to changes in disease course over time, with improvements in the instrument gained by iterative revisions25-27. In this study, we evaluated the reliability, convergent validity, construct validity, and practical applicability of the newly proposed CSAMI and the existent SASI in evaluating cutaneous sarcoidosis.

All three instruments demonstrated high intra-rater reliability. Fair to poor inter-rater reliability of individual SASI component scores and modified Facial SASI scores are consistent with results from their original study9. In contrast, the inter-rater reliability of CSAMI Activity scores were excellent and significantly higher than that of SASI scores, while the inter-rater reliability of CSAMI Damage scores were fair and comparable to that of SASI scores.

CSAMI Activity, Damage, and modified Facial SASI correlated modestly with PGA, with significant linear associations demonstrated. Given its poor inter-rater reliability, PGA is an imperfect reference that may not per se be very useful in assessing cutaneous sarcoidosis activity. Nevertheless, since there is no established gold standard against which criterion validity may be construed, convergence between CSAMI and modified Facial SASI scores with the PGA suggested that both instruments reflected physicians’ global impression of disease activity. It is unsurprising that CSAMI damage does not correlate particularly well with the PGA, as the damage scale is designed to capture residua and not active disease, while many physicians may utilize PGA to measure disease activity.

Strong to moderate correlations between CSAMI and Skindex-29 domains provided preliminary evidence for construct validity, wherein objective evaluation using CSAMI correlated well with patients’ subjective impression of disease impact. Given our small sample size, the analysis is underpowered to detect more modest correlations with other quality of life metrics. Nonetheless, point estimates of these correlations trended higher with CSAMI than with SASI. Larger studies to confirm the ability of CSAMI and/or SASI in predicting quality of life impacts are needed.

Both instruments were scored in less than 5 minutes, which is considered adequate for use in clinical trials and may be acceptable for routine clinical practice28. While CSAMI required longer to score than SASI, both instruments required less time to complete in repeat ratings.

CSAMI captured lesion morphologic types with substantial intra-rater and moderate inter-rater reliability. While prognostic implications of specific lesions like lupus pernio and erythema nodosum are widely recognized, those of other morphologies are less well established2. Previous studies have implicated lupus pernio with increased risks of sinus disease and bone cysts and subcutaneous lesions with increased risks of systemic disease29. Documentation of morphologic types using CSAMI may facilitate studies on prognostic relationships between lesional morphologies and systemic involvement as well as treatment response.

We feel that it is important for a cutaneous sarcoidosis instrument to include physician rating of inactive lesions including hyperpigmentation, with the caveat that given the protean nature of sarcoidosis, it may be challenging in some cases to distinguish inactive post-inflammatory residua from active lesions. However, persistent hyperpigmentation or scarring may be inelastic to therapy and significantly impact patients’ quality of life, thus separately categorizing these lesions may be important for evaluating therapeutic response in clinical trials. CSAMI is designed to capture the impact of involved area size, without subjecting that metric to a multiplier that could magnify carried errors in the final numbers. Treatments often first impact lesion erythema or induration, while area may be slower to respond; thus we felt that incorporating area as a separate value in CSAMI may better reflect cutaneous sarcoidosis activity than as a multiplier, as done in SASI.

Our study should be reviewed in light of its limitations. Recall bias on intra-rater reliability cannot be excluded given the relatively short time elapsed between first and second ratings within a single afternoon, but it was minimized since neither the physicians nor the patients were told about the re-scoring session at the study onset. While our patients were selected to represent a wide spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis activity, the smaller than planned sample size limited our data's external validity, particularly for patients with different clinical presentations, disease severity, and/or treatment history. All physician participants were dermatologists, so our results may not be generalized for instrument use by non-dermatologists. Future studies are necessary to confirm the instruments’ correlations to quality of life measures, show their sensitivity to change, and provide meaningful interpretation in terms of minimal clinically important differences3. Iterative revisions of the instruments, particular on the less reliable subscales, may optimize their psychometric properties and refine their ability to categorize cutaneous sarcoidosis severity.

In conclusion, this study provided psychometric validation of CSAMI and SASI in patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis. CSAMI has demonstrated reasonable reliability, convergent validity, and clinical acceptability and captured a wide range of body surface and cutaneous morphologies. Sensitivity to change and preliminary evidence of construct validity between CSAMI and quality of life measures should be further examined. CSAMI should be considered as an outcome instrument for the evaluation of disease severity and documentation of lesion morphologies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rosemary Attor for administrative support during the research day.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the training grant T32-AR07465 from the National Institutes of Health (H.Y.); National Psoriasis Foundation Fellowship (J.T.); Department of Veterans Affairs (Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development) and NIH K24-AR02207 (V.P.W.); and Medical Dermatology Career Development Award from the Dermatology Foundation (M.R.).

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Rosenbach and Mr. Yeung contributed equally to the work. Dr. Rosenbach and Mr. Yeung have full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Rosenbach, Yeung, Werth; Acquisition of data: Rosenbach, Yeung, Chu, Kim, Payne, Takeshita, Vittorio, Wanat, Gelfand; Analysis and interpretation of data: Rosenbach, Yeung; Drafting of the manuscript: Rosenbach, Yeung; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Rosenbach, Yeung, Chu, Kim, Payne, Takeshita, Vittorio, Wanat, Werth, Gelfand; Statistical analysis: Rosenbach, Yeung, Gelfand; Obtained funding: Rosenbach, Werth; Administrative, technical, or material support: Rosenbach, Werth; Study supervision: Rosenbach, Werth, Gelfand.

Financial Disclosure:

1) Relevant to this manuscript: Dr. Rosenbach led the development of the Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Instrument. Other authors have no relevant disclosures to report.

2) All other relationships: None reported.

References

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 22;357(21):2153–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. Cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 May;66(5):699, e691–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.11.965. quiz 717-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spuls PI, Lecluse LL, Poulsen ML, Bos JD, Stern RS, Nijsten T. How good are clinical severity and outcome measures for psoriasis?: quantitative evaluation in a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol. 2010 Apr;130(4):933–943. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachelez H, Senet P, Cadranel J, Kaoukhov A, Dubertret L. The use of tetracyclines for the treatment of sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Jan;137(1):69–73. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein AS, Moller DR, Lower EE. Thalidomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Chest. 2002 Jul;122(1):227–232. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen YT, Dupuy A, Cordoliani F, et al. Treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis with thalidomide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Feb;50(2):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stagaki E, Mountford WK, Lackland DT, Judson MA. The treatment of lupus pernio: results of 116 treatment courses in 54 patients. Chest. 2009 Feb;135(2):468–476. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Ingledue R, Craft NL, Lower EE. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Feb;148(2):262–264. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein A, et al. Chronic facial sarcoidosis including lupus pernio: clinical description and proposed scoring systems. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(3):155–161. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007 Oct 20;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin JA, et al. The CLASI (Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 2005 Nov;125(5):889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein RQ, Bangert CA, Costner M, et al. Comparison of the reliability and validity of outcome instruments for cutaneous dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Sep;159(4):887–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08711.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenbach M, Murrell DF, Bystryn JC, et al. Reliability and convergent validity of two outcome instruments for pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009 Oct;129(10):2404–2410. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goreshi R, Okawa J, Rose M, et al. Evaluation of reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the CDASI and the CAT-BM. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Apr;132(4):1117–1124. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ. Improved discriminative and evaluative capability of a refined version of Skindex, a quality-of-life instrument for patients with skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1997 Nov;133(11):1433–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994 May;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, Kataria YP, Judson MA. The Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire: a new measure of health-related quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Aug 1;168(3):323–329. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1343OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gourraud PA, Le Gall C, Puzenat E, Aubin F, Ortonne JP, Paul CF. Why Statistics Matter: Limited Inter-Rater Agreement Prevents Using the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index as a Unique Determinant of Therapeutic Decision in Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 May 17; doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979 Mar;86(2):420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull. 1971;76(5):378–382. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mezzich JE, Kraemer HC, Worthington DR, Coffman GA. Assessment of agreement among several raters formulating multiple diagnoses. J Psychiatr Res. 1981;16(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(81)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977 Mar;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Vries J, Lower EE, Drent M. Quality of life in sarcoidosis: assessment and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Aug;31(4):485–493. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guryleva ME. [Life quality in patients with sarcoidosis and isolated skin syndrome in chronic dermatoses]. Probl Tuberk Bolezn Legk. 2003;(8):28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaines E, Werth VP. Development of outcome measures for autoimmune dermatoses. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008 Jan;300(1):3–9. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0813-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chren MM. Giving “scale” new meaning in dermatology: measurement matters. Arch Dermatol. 2000 Jun;136(6):788–790. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.6.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlay AY. Measurement of disease activity and outcome in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Oct;135(4):509–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt J, Langan S, Williams HC. What are the best outcome measurements for atopic eczema? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007 Dec;120(6):1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed I, Harshad SR. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: is it a specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Jan;54(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]