Abstract

Background: The diagnosis of motor neurone disease (MND) has a profound effect on the functioning and well-being of both the patient and their family, with studies describing an increase in carer burden and depression as the disease progresses.

Aim: This study aimed to assess whether patient use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) impacted on their family carer, and to explore other sources of carer burden.

Design: The study used qualitative interviews and scaled measures of carer health and well-being completed at three monthly intervals until patient end of life.

Participants: Sixteen family carers were followed up over a period ranging from one month to two years.

Results: NIV was perceived as having little impact on carer burden. The data however highlighted a range of sources of other burdens relating to the physical strain of caring. The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36 Health Survey) Physical Component Summary (PCS) scores were considerably below that of the Mental Component Summary (MCS) score at baseline and at all following time points. Carers described the physical effort associated with patient care and role change; the challenge inherent in having time away; and problems relating to the timing of equipment and service delivery.

Conclusions: NIV can be recommended to patients without concerns regarding increasing carer burden. The predominant source of burden described related to the physical impact of caring for a patient with MND. Services face challenges if this physical burden is to be reduced by providing equipment at an optimal time and successfully coordinating their input.

Introduction

The diagnosis of motor neurone disease (MND) has a profound effect on the functioning and well-being of both the patient and carers.1,2 Families have been described as making a parallel journey to that of the patient, from diagnosis, to increasing disability, and ultimately decisions about death.3 Several studies have described an increase in carer burden and depression as the patient's disease progresses.4–6 Patient and carer perceptions of each other's burden and quality of life may however differ. It has been found that patients rate caregivers as more burdened than they rate themselves, and that carers perceive patients as having a lower quality of life than patients self-report.5 This has led researchers to recommend that the needs of carers should be assessed separately from patient needs.7–9

A number of studies have examined the stress experienced by families who care for a patient with MND. This work has highlighted the importance of providing appropriate emotional support.1,10 Other areas of burden that have been reported are time dependence (the limited availability of time for oneself); role overload due to heavy care needs; and “role captivity” resulting from caregiving excluding other aspects of a carer's life.4,10,11

Disease progression and worsening of disability may lead to a requirement for input from paid caregivers.11 It is currently unclear, however, whether the presence of paid caregivers decreases the burden on the family carer.12,13 The offer of professional support may be refused, or the level of input provided may be inadequate or too late.13 A range of factors may underpin a lack of paid support for carers including a lack of awareness of availability; lack of knowledge regarding entitlement to services; a wish to maintain a sense of normalcy; and the desire to retain independence, dignity, or control over their lives.9,14 Professional caregiving has been criticized for failing to adequately integrate services, or for lacking mechanisms to provide the speed of response required in a rapidly progressing condition.15

Respiratory muscle weakness in MND may impact on a patient's everyday functioning to a greater extent than physical disability, and therefore have a significant effect on a carer.16 Indeed, a previous study has suggested that the distress of caregivers in MND might be related to patient respiratory issues.17 Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is now a widely used intervention to address poor respiratory functioning. The system has been reported to improve patient longevity and quality of life.16 Concerns that patient use of NIV may increase carer burden or stress have not been supported using questionnaire measures.16 However, there is a lack of qualitative work exploring carer perceptions in MND, with significant gaps in research.10,18

This study followed patients and family carers over the course of the disease following the recommendation to start NIV. We aimed to assess whether patient use of NIV impacted on carers, and to explore sources of other burdens.

Methods

The study used a longitudinal mixed-methods approach including questionnaires and qualitative interviews with carers. Interviews were carried out at three monthly intervals from initiation on NIV until death of the patient. Patients were recruited sequentially at outpatient clinic appointments with inclusion criteria being a clinically definite diagnosis of MND as per revised El Escorial criteria;19 symptoms of muscle weakness; and objective evidence of respiratory failure. All carers were invited to participate, with patient inclusion not requiring their carer to also take part. Ethical approval was granted by Leeds Research Ethics Committee, with all participants receiving detailed information sheets and completing consent forms prior to data collection. Initiation on the NIV system took place either at home or during a short inpatient stay with demonstration, explanation, written information, and helpline access provided. Semistructured interviews were carried out by experienced qualitative researchers (SB and ST) in the patients' home, and questionnaires were left for completion (with a reply envelope for return). The interviews were based on a topic guide (see Appendix 1) that was developed and tested via pilot interviews. Participants completed a range of questionnaires at baseline (before the introduction of NIV) and three monthly intervals, including two measures of carer health and well-being, SF-3620 and the Caregiver Strain Index (CSI).21

The CSI is a 13-item tool that measures strain related to care provision, including items relating to sleep disturbance, physical strain, and social and emotional adjustment. The CSI does not provide a scale of severity; however, more than seven “yes” responses are indicative of high strain. The SF-36 has eight concepts or scales. Two summary scores of health may be calculated from the subscales: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores. These summary scores are calculated using norm-based scoring and are standardized to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 (the same as the reference population), with higher scores indicating better health.22

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Qualitative data were analyzed using techniques of thematic analysis. In this method, interview transcripts are read line by line and concepts (or themes) identified and assigned a code.23 Following this initial coding of each interview transcript, data within each code are examined and compared to develop a coding tree of themes and subthemes across all the interviews. We used NVivo8 software (QSR International, Burlington, MA) to manage this process of data coding and retrieval. Following initial coding by SB, the coding tree and data underpinning each theme were presented at several team meetings. Potential overlaps in themes or differing opinion in the coding assigned were discussed to establish consensus.

Results

Twenty patients were recruited to the study. One patient had no carer, two carers declined to participate, and one carer later withdrew. Sixteen carers (11 wives, 3 husbands, and 2 other family members) took part. See Table 1 for characteristics of the participants. Five patients and their carers were followed for six months or less, and 11 were followed for 10 months or more. The longest follow-up period was two years. In the following section we first outline the results from analysis of the quantitative data before describing the key themes from the qualitative interviews, which provide additional insight into the questionnaire findings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 16 Carer and MND Patient Participants

| Carer | Follow-up period | Patient age | Site of onset | Patient ALSFRS Bulbar subscorea(0=severe impairment; 12=normal) | Patient ALSFRS Limb subscoreb(0=severe impairment; 12=normal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wife |

20 months |

60–69 |

Limb |

12 |

8 |

| Husband |

One month |

70+ |

Limb |

12 |

0 |

| Wife |

26 months |

70+ |

Limb |

5 |

10 |

| Wife |

25 months |

60–69 |

Limb |

10 |

7 |

| Husband |

19 months |

70+ |

Limb |

10 |

7 |

| Wife |

19 months |

60–69 |

Limb |

12 |

9 |

| Husband |

10 months |

60–69 |

Bulbar |

3 |

10 |

| Other family |

14 months |

60–69 |

Limb |

12 |

8 |

| Wife |

23 months |

70+ |

Respiratory |

8 |

6 |

| Wife |

3 months |

70+ |

Limb |

9 |

6 |

| Wife |

5 months |

70+ |

Limb |

12 |

7 |

| Wife |

19 months |

70+ |

Limb |

12 |

8 |

| Wife |

18 months |

Under 60 |

Limb |

10 |

9 |

| Wife |

18 months |

70+ |

Limb |

8 |

8 |

| Daughter |

3 months |

70+ |

Respiratory |

12 |

9 |

| Wife | 3 months | 60–69 | Limb | 12 | 11 |

Composite of speech, saliva, and swallowing scores.

Composite of handwriting, feeding, and dressing/hygiene scores.

ALSFRS, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale.

Questionnaire data

Carer strain scores

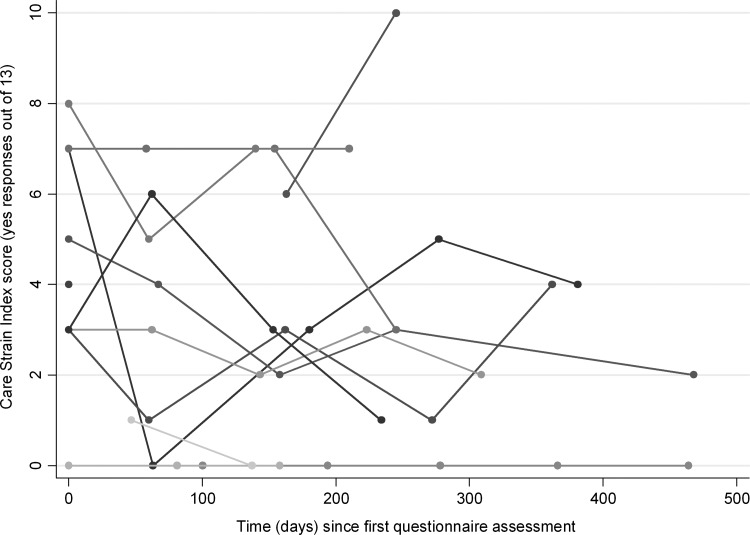

Fifteen carers completed the CSI on at least one occasion, with nine completing three or more (See Table 2 and Figure 1). One carer opted out of completion. There was a large range in level of strain recorded among participants. Three carers scored higher than 7 at least once during the data collection period, whereas four other individuals scored 0 at least once. Scores generally were in the lower strain range with a mean score of 4 (over five time points) and no clear time trend.

Table 2.

Median Caregiver Strain Index Scores over Time

| |

Number of “yes” responses out of 13 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median | Percentile, 25th | Percentile, 75th | |

| Baseline |

15 |

4 |

3 |

7 |

| Second |

11 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

| Third |

11 |

3 |

0 |

6 |

| Fourth |

9 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

| Fifth |

5 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

| Sixth | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

FIG. 1.

Individual carer Strain Index scores over time (N=13).

Carer physical and mental health scores

Thirteen carers completed the SF-36 measure at least once, with nine completing it four or more times (see Table 3 and Figures 2 and 3). The PCS and MCS scores are calculated using norm-based scoring and are standardized to have a mean of 50 and an SD of 10, with a potential range of −100 to +100. While the use of summary measures can create seemingly counterintuitive negative values (as found in our data), the method is a useful way of standardizing change, enabling meaningful comparison between different subscale scores. Analysis of these component summary scores found that (as may be expected) they were much lower for the sample than the average for the reference population (most below three SDs). Perhaps more surprisingly, the scores were fairly constant over time. There was a notable difference between the summary scores, with the PCS scores much lower than the MCS scores (mean 0.5 [SD 15.4] versus mean 14.6 [SD 14.3]). These data suggest that caring had more of an effect on physical than on mental health.

Table 3.

Carer Mean SF-36 PCS and MCS Scores over Time (Maximum N=13)

| |

|

MCS |

PCS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of questionnaire | ValidN | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Baseline/first questionnaires |

13 |

14.6 |

14.3 |

.05 |

15.4 |

| Second questionnaires |

10 |

13.6 |

8.3 |

−4.6 |

15.7 |

| Third questionnaires |

9 |

17.1 |

12.0 |

−0.8 |

11.8 |

| Fourth questionnaires |

9 |

11.9 |

12.4 |

−4.0 |

13.3 |

| Fifth questionnaires |

5 |

15.8 |

15.0 |

−4.1 |

22.3 |

| Sixth questionnaires | 2 | 14.0 | 12.8 | −0.9 | 20.4 |

MCS, Mental Component Summary score; PCS, Physical Component Summary score; SF-36, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form.

FIG. 2.

Individual carer SF-36 Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores over time (N=13).

FIG. 3.

Individual carer SF-36 Physical Component Summary scores over time (N=13).

Carer perceptions regarding the impact of noninvasive ventilation

During the interviews we explored perceptions regarding the impact of NIV and whether this created any additional burden for carers. Participants reported that they found the system easy to operate and maintain, and there were no reports in the data of NIV significantly contributing to carer burden.

“It's not made a great deal of difference to me…. It's just an extra bit of machinery to sort of look after, although it doesn't take a lot.” [carer(c)5interview(i)2]

Some recalled that in the early weeks the machine had “taken over” before it became part of everyday routine.

“It did seem to take over, that became extremely important. But as the time's gone on, as I say, we've got a lot more relaxed with it.” [c4i5]

Some carers had found an initial issue with noise.

“Just to start with, you have to get used to the noise at nighttime.” [c1i4]

The sole example of burden mentioned by a small number of carers was the weight of the device.

“It's very heavy for me to carry the machine and move it around.” [c16i2]

Carer perceptions regarding sources of burden

Related to the findings on NIV impact, the study data provide valuable insight into sources of other potential burden. Carers described how as the disease progressed there were role changes within the home. They also found difficulty having time away; reported accepting professional help to be a challenge; and described how the timing of equipment and services could be problematic. These aspects may underpin the increasing physical burden recorded in the questionnaire data.

Role change and patient needs

Carers described physical demands resulting from addressing the needs of the patient and from changes in roles and responsibilities as the patient's disability increased. The physical strain of lifting the patient, and moving and managing necessary equipment was described.

“I just thought…what am I going to do now, because the wheelchair's heavy by itself, let alone I can't lift [patient]'s weight.” [c1 i1]

Activities that their partner used to carry out were taken on by the carer, such as driving, housework, and meal preparation.

“I'd never had to do any ironing but I've done it now. So if it comes to a pinch I can do it.” [c8i1]

Carers frequently described overwhelming tiredness from these additional duties.

“I'm continually whacked, you know…it's draining.” [c11i1]

The exhaustion was exacerbated by a lack of sleep.

“I'll wake up at 12 o'clock and then at 2 o'clock, then at 4 o'clock…. It's just as if I'm conditioned to wake every two hours, and I'll listen to him and then I go back to sleep. Well if I'm lucky.” [c12i4]

The adaptation to roles was so gradual for some that it appeared to pass unnoticed until they reflected at interview on how things used to be.

“I dress him more than I used to…and that's a gradual thing, but you don't notice it's happening until you look back.” [c16i3]

Difficulty having time away

As the disease progressed and physical limitations made going out more problematic for the patient, carers described how their life also became more centered around the home.

“I suppose the fact that we can't get out as much as we used to do…it means that I sometimes can't get out. Or if I do it's a sort of quick nip into town and hope my phone doesn't ring while I'm gone.” [c5i1]

While many carers had access to respite or paid services that would have enabled them to leave the patient safely, they described feelings of worry or guilt when leaving for anything but short periods. Some carers preferred not to take up these offers of help, or chose to remain in the home while staff were there.

“I'm not saying I can't go because of him. It's I can't go because I don't think I'm fully up to it either because I think my mind would wander and I'd start to worry.” [c6i3]

Acceptance of professional help

The acceptance of assistance was reported to be a key challenge. Some carers perceived that it was their responsibility to care for the patient.

“Well I was quite happy to continue as long as I could, doing it myself, and it was left like that.” [c13i6]

For others, the patient had refused to accept support from external agencies, and that decision was accepted by carers.

“We did try carers for a very short time, but [patient] wasn't happy with them, he just didn't want it.” [c1i4]

Some carers also reported bad experiences.

“You know they just shoved him and pulled him and he looked at me as if to say, For God's sake stop them…. They come and they've got to get it done…and it just was too much for him.” [c12i5]

Timing of equipment and support services

Problems were apparent with timing the introduction of equipment that may have reduced carer physical effort. Some carers described equipment being provided before a patient perceived that it was necessary.

“They're on about him having a stair lift but he can go up the stairs quite good and he can come down the stairs quite good…and he thought they were rushing him.” [c15i2]

Others, in contrast had found that equipment had arrived too late.

“It's a bit unkind to say that they don't provide the things because they do, but…they make the assessment and with a progressive disease by the time they've actually installed it it's no use.” [c2i2]

The introduction of equipment into the home was also perceived as intrusive and a struggle for carers to come to terms with.

“And then it becomes not your house anymore because these people are coming in and telling you what to do and they're measuring up for this and that.” [c4i6]

The involvement of many different agencies was also described as a challenge.

“The day after he came home, there were seven people in this house, seven different agencies. And in the end I just told them all to go away because I couldn't stand it any longer.” [c6i5]

This inundation of services was described as happening particularly in the early weeks after diagnosis.

“Initially there were so many people coming, you know, at first, and I thought, I don't want all these people in my house. Well since then it's tapered off so much we hardly see anybody.” [c4i2]

Discussion

This study reports a low perceived impact on carers when patients with MND are advised to use NIV. It found a lack of change in carer scores on self-reported questionnaire measures from baseline introduction of NIV, and carer descriptions indicated little or no impact of NIV on everyday living. This intervention therefore may be recommended without concern regarding increasing carer burden. The heavy weight of the device was mentioned by some (the machine weighs 1.8 kg and the battery adds 6.0 kg), suggesting that it may be optimal for patients to have more than one machine to reduce relocation between day and night use.

The data we collected during the course of the study also provides broader insight into other sources of potential carer burden. In particular it highlights the physical burden that is experienced. Authors of a previous investigation called for greater access to training in manual handling and improved training in physical care to be provided for carers.14 Findings from the current study are supportive of this recommendation. The data also report the perception of inundation of services in the early phases following diagnosis. This suggests that coordination of visits between agencies should be better planned.

Previous work has reported a close relationship between patient physical function and carer burden, with the burden increasing as there is greater functional impairment.13 A surprising finding from our data therefore was that SF-36 scores appeared to change little over time. Data from the CSI similarly remained fairly constant during the period of data collection and appeared to indicate a generally low level of strain among the sample (although it should be noted that there was considerable individual variability). The low level of strain found in the CSI scores, however, contrasted sharply with the SF-36 results, which raises some concerns regarding the sensitivity of this instrument.

The use of SF-36 summary component scores, while widely reported, has been criticized on the grounds that the PCS and MCS scores are not independent of each other.24 The data we present may therefore overemphasize the distinction between closely interrelated elements of carer burden. The emphasis on physical impact that we found may also be related to the demographics of the participants. The mean age of onset of MND varies; however it is reported to be between 55 and 65 in most studies.25,26 Our sample contained a higher proportion of patients in an older age group than might be expected, with nine over 70 and only one below 60. We omitted collecting carer age data; however all appeared to be in the same over-60s age range as the patients. A proportion of the spouses themselves had health problems associated with older age such as a hip replacement, arthritis, or back problems, which presented additional challenges in caring for their partner. A further feature of the sample is the high proportion of female carers, which may also be significant when considering the data.

The study reports data from a very small sample for quantitative analysis, with loss of participants over time due to patient death or noncompletion of questionnaires. Caution is therefore required in interpreting the scaled data. The sample also represents only carers of patients who had been advised to use NIV, and may therefore not be representative of other carers. The data, however, is useful in providing a baseline measure before and after the introduction of NIV, indicating that NIV does not significantly contribute to carer burden.

Conclusions

The study found no evidence of patient use of NIV significantly adversely impacting on carer burden. Provision of more than one device may avoid transporting a heavy machine around the home. While the study reports findings from a small number of carers, and the sample overrepresents females and older adults, our data are valuable in highlighting the physical demands of acting as a family carer. The initial weeks following diagnosis were described as being a time of being inundated by services entering the home. The recommendation from other authors that support for carers should be started early13 should therefore be balanced with coordination of input from different agencies in order that carers do not become overwhelmed. The timing of equipment supply is also crucial to ensure that aids are present when needed but that provision is not perceived by patients as being too early. The obstacles to accessing support should be further considered if carer burden is to be reduced.

Appendix 1. Interview Topic Guide

Introduction: consent / confidentiality, anonymity / break if needed.

1. Focus on NIV and its impact: What has changed since last time?

2. Using the equipment: frequency; take me through procedure for starting and finishing; mask/user interface (fit, skin); using the machine (self or with carer assistance); anxious feelings/claustrophobia; mouth care (dryness, extra secretions).

3. Who looks after the NIV equipment, setting up; involvement of anyone else?

4. Day-to-day activity: breathing; sleeping; communication (speech/writing); appetite; washing/showering/dressing/shaving;concentration; fatigue levels; coughing/choking; getting out and about (if relevant); battery pack for getting out; isolation; independence; impact on family and friends.

5. What is a typical day like for you?

6. Has the NIV made any difference to patient/carer's life?

7. Support: How much needed over last month; source of support (gaps); success in getting support; how often was it needed; NIV support; information needs.

8. Reliability and help if not working.

9. What would you tell someone else about NIV?

10. Any changes to the support and information to help people on NIV in the future?

11. Obstacles: Any way things could have been better managed?

12. What were the main problems at first/How did you manage them?

13. Anything else which would have helped at initiation?/Was there enough support?

14. Benefits of NIV? Does carer agree? How important is it to you?

15. Problems/frustrations/worries/unexpected difficulties. Does carer agree?

16. How have you/carer coped with the NIV?

17. What do they think of the NIV?

18. Have you/carer had to make any adjustments to your day-to-day life because of the NIV?

19. How are things going for you at the moment? What keeps you going/helps you cope? Any worries?

20. Summary+anything else you would like to add?

Acknowledgments

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) program (grant PB-PG-1207-15122). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. We would like to thank the patients and their carers who took part in the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Aoun S, Connors S, Priddis L, Breen L, Colyer S: Motor neurone disease family carers' experiences of caring, palliative care and bereavement: An exploratory qualitative study. Palliat Med 2012;26:842–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Swash M, Peto V, and the ALS-HPS Steering Group: The ALS health profile study: Quality of life of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and carers in Europe. J Neurol 2000;415:835–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabkin J, Albert S, Rowland L, Mitsumoto H: How common is depression among ALS caregivers? A longitudinal study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009;10:448–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gauthier A, Vignola A, Calvo A, Cavallo E, Moglia M, Sellitti L, et al. : A longitudinal study on quality of life and depression in ALS patient-caregiver couples. Neurology 2007;68:923–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adelman E, Albert S, Rabkin J, Bene M, Tider T, O'Sullivan I: Disparities in perceptions of distress and burden in ALS patients and family caregivers. Neurology 2004;62:1766–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein L, Atkins L, Landau S, Brown R, Leigh P: Predictors of psychological distress in carers of people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A longitudinal study. Psychol Med 2006;36:865–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson A, Markhede I, Strang S, Persson L: Differences in quality of life modalities give rise to needs of individual support in patients with ALS and their next of kin. Palliat Support Care 2010;8:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trail M, Nelson N, Van J, Appel S, Lai E: A study comparing patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their caregivers on measures of quality of life, depression, and their attitudes toward treatment options. J Neurol Sci 200;209:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grande G, Todd C, Barclay S: Support needs in the last year of life: Patient and carer dilemmas. Palliat Med 1997;11:202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyebode J, Smith H, Morrison K: The personal experience of partners of individuals with motor neuron disease. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012. E-pub ahead of print. DOI: 10.3109/17482968.2012.719236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chio A, Gauthier A, Vignola A, Calvo A, Ghiglione P, Cavallo E, et al. : Caregiver time use in ALS. Neurology 2006;67:902–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chio A, Gauthier A, Calvo A, Ghiglione P, Mutani R: Caregiver burden and patients' perceptions of being a burden in ALS. Neurology 2005;64:1780–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hecht M, Graesel E, Tigges S, Hillemacher T, Winterholler M, Hilz M, et al. : Burden of care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Palliat Med 2003;17:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Brien M, Whitehead B, Murphy P, Mitchell J, Jack B: Social services homecare for people with motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Why are services used or refused? Palliat Med 2012;26:123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown J, Lattimer V, Tudball T: An investigation of patients and providers' views of services for motor neurone disease. Brit J Neurosci Nurs 2005;1:249–252 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mustafa N, Walsh E, Bryant V, Lyall R, Addington-Hall J, Goldstein L, et al. : The effect of noninvasive ventilation on ALS patients and their caregivers. Neurology 2006;66:1211–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagnini F, Banfi P, Lunetta C, Rossi G, Castelnuovo G, Marconi A, et al. : Respiratory function of people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and caregiver distress level: A correlational study. ByoPsychosocial Med 2012;6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson PL, Zordan R, Trauer T: Research priorities associated with family caregivers in palliative care: International perspectives. J Palliat Med 2011;14:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL: El Escorial revisited: Revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Sc 2000;1;293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware J, Sherbourne C: The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): Conceptual framework and items selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson B: Validation of a caregiver strain index. J Gerentol 1983;39:344–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen S, Stewart Brown S, Peto V: Health and Lifestyles in Four Counties: Results from the Third Healthy Lifestyle Survey. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason J: Qualitative Researching, 2nded.London, UK: Sage, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M: Do SF-36 summary component scores accurately summarize subscale scores? Qual Life Res 2001;10:395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blasco H, Guennoc A, Veyrat-Durebex C, Gordon P, Andres C, Camu W, et al. : Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A hormonal condition? Amyotroph Later Scler 2012;13:585–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw P: Motor neurone disease. BMJ 1999;318:1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]