Abstract

Mechanisms of regulation of mitochondrial metabolism in trypanosomes are not completely understood. Here we present evidence that the Trypanosoma brucei mitochondrial calcium uniporter (TbMCU) is essential for regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics, autophagy, and cell death, even in the bloodstream forms that are devoid of a functional respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation. Localization studies reveal its co-localization with MitoTracker staining. TbMCU overexpression increases mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation in intact and permeabilized trypanosomes, generates excessive mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), and sensitizes them to apoptotic stimuli. Ablation of TbMCU in RNAi or conditional knockout trypanosomes reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake without affecting their membrane potential, increases the AMP/ATP ratio, stimulates autophagosome formation, and produces marked defects in growth in vitro and infectivity in mice, revealing its essentiality in these parasites. The requirement of TbMCU for proline and pyruvate metabolism in procyclic and bloodstream forms, respectively, reveals its role in regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics.

Trypanosoma brucei belongs to the group of parasites that causes nagana in cattle and African sleeping sickness in humans, one of the most neglected diseases in the World. Two of its life cycle stages that are easily grown in the laboratory are the procyclic form (PCF), which is one of the forms present in the tse tse fly vector, and the bloodstream form (BSF), which is present in the blood of the infected mammalian host. Each form has a single mitochondrion that greatly differs in morphology and metabolism. The PCF mitochondrion is well developed and has a respiratory chain, while the BSF mitochondrion is more rudimentary, does not possess a functional respiratory chain or oxidative phosphorylation, and relies on the reverse action of the ATP synthase to maintain the mitochondrial membrane potential 1-4. Proline is the key energy source within the tse tse fly 5,6 and probably the main energy source of the PCF 7-9 through the mitochondrial generation of ATP by oxidative phosphorylation 10,11. In contrast, glucose is abundant in the blood of the mammalian host and the parasite has adapted to the availability of this substrate by using glycolysis as the main source of ATP, with generation of pyruvate, which is mostly excreted to maintain its intracellular pH 12.

In mammalian cells, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) is required to provide reducing equivalents to support oxidative phosphorylation 13 through activation of three intramitochondrial dehydrogenases 14,15 and the ATP synthase 16. Interestingly, BSF possess a MCU 1 despite the absence of respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation 17.

The MCU has low affinity and high capacity for Ca2+ uptake and although it was first identified more than 50 years ago 18,19 its molecular nature was discovered only recently 20,21. Evidence of the presence of a MCU in trypanosomes 22,23 and its absence in yeast 24 was the key to the discovery of the molecular identity of MCU 20,21, and of one modulator of the uniporter, the mitochondrial calcium uptake 1 or MICU1 25, in mammalian cells 17.

Although the relevance of the MCU in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake has been elucidated 20,21,26 it is not yet known whether this channel is essential for the survival of any organism. In addition, the presence of a MCU in the mitochondria of BSF, which are devoid of respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation, suggests that Ca2+ could have other functions in the mitochondria of these cells.

In this work we report that knockdown of the TbMCU gene by RNAi in PCF and BSF trypanosomes or by conditional knockout in BSF trypanosomes led to marked decrease in mitochondrial calcium uptake without affecting their membrane potential, and marked growth defects and reduced infectivity in vivo, underscoring the relevance of this channel for parasite survival. In addition, we demonstrate the role of the MCU in maintaining mitochondrial bioenergetics in both PCF and BSF trypanosomes.

Results

Characterization of TbMCU

One gene (Tb927.11.1350) encoding a putative MCU was found in the T. brucei genome at the TriTryp database (http://tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb/) and named TbMCU. The full-length cDNA of TbMCU was cloned by PCR amplification and confirmed by sequencing as described in Methods. The orthologs identified in T. cruzi (TcCLB.503893.120) and Leishmania major (LmjF27.0780) shared 49% and 41% amino acid identity, respectively, to TbMCU, which shares 20% identity and 33% similarity with the human MCU. Structural analysis (ELM and TMHMM servers) predicted 2 transmembrane domains in the C-terminal region between amino acids 201-223, and 233-250. The ORF predicts a mature (or processed) protein of 259 amino acids (aa) with an apparent molecular weight of 30 kDa, preceded by a 48-aa N-terminal mitochondrial-targeting signal. A motif for the putative Ca2+-specific selectivity filter (WDIMEPV) is present in the loop between transmembrane domains at the C-terminal region.

TbMCU localization in PCF and BSF trypanosomes

To investigate the localization of T. brucei MCU, a C-terminal GFP-tagged TbMCU transgenic cell line was generated in PCF trypanosomes. Western blot analysis confirmed expression of proteins of the expected size (Supplementary Fig. S1a). The detection of two bands of tagged TbMCU has been shown before when tagging the mammalian MCU 20,27 and could be due to interference of the tag with the processing of the N-terminal mitochondrial targeting signal, as only one band is detected when using antibodies against the protein (see below; Fig. 1h and i). The GFP-tagged cells grew as well as the wild type cells (Supplementary Fig. S1b). TbMCU localized to the mitochondria, as demonstrated by co-localization with MitoTracker (Fig. 1a). To eliminate the possibility of mis-targeting of the GFP tagged protein, antibodies against TbMCU were generated through immunization of mice with the recombinant protein. The purified antibody specifically bound to the mitochondria of PCF (Fig. 1b) and BSF (Fig. 1c) trypanosomes, as shown by co-localization with MitoTracker.

Figure 1. TbMCU co-localizes with MitoTracker and its downregulation by RNAi affects growth in PCF and BSF trypanosomes.

(a) TbMCU-GFP co-localization with MitoTracker (MT) in mitochondria of PCF trypanosomes as detected by immunofluorescence analyses with antibodies against GFP (Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC): 0.912). (b and c) TbMCU co-localization with MitoTracker in mitochondria of PCF (b) or BSF (c) trypanosomes, as detected by immunofluorescence analyses with antibodies against TbMCU. PCC: 0.930 and 0.920, respectively. Merge images show the co-localization in yellow. DIC, differential interference contrast microscopy. Bars in (a-c) = 10 μm. (d and e) Growth of BSF (d) and PCF (e) trypanosomes in the absence (black lines, −Tet) or presence (red lines, +Tet) of 1 μg/ml tetracycline for the indicated number of days. Values are mean ± S.D. (n = 3). (f and g) Northern blot analyses of TbMCU RNAi of BSF (f) and PCF (g) trypanosomes grown in the absence (0) and presence (2-8; 2-10) of tetracycline (top). Tubulin is shown as a loading control (bottom). Markers are shown on the right. The transcript of TbMCU, including the 5′- and 3′-UTR was ~1.5 kb in length. (h and i) Western blot analyses of TbMCU RNAi of BSF (h) and PCF (i) trypanosomes grown in the absence (0) or presence (2-8; 2-10) of tetracycline. Total lysates (30 μg) were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis before transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane and then stained with antibodies against TbMCU (top). One band of ~30 kDa was detected in T. brucei homogenates. Membranes were stripped and re-incubated with antibody against the voltage-dependent anion channel (TbVDAC) as a loading control (bottom).

TbMCU is required for optimal growth in vitro

Knockdown of TbMCU by induction of double-stranded RNA resulted in growth defects in both BSF (Fig. 1d) and PCF trypanosomes (Fig. 1e). The effects were most pronounced with PCF trypanosomes, with up to 64 ± 7 % reduction in the number of cells at day 10 while there was a 56 ± 6% reduction in the number of BSF trypanosomes at day 6. Northern blot and ImageJ analyses showed that the mRNA was downregulated by 32 to 75% after 4-10 days of tetracycline addition to PCF trypanosomes (Fig. 1g). Similar results were observed after RNAi of BSF trypanosomes (Fig. 1f), although the mRNA recovered from 60% at 4 days to 45% knockdown after 8 days. Western blot analyses revealed a correlative decrease in TbMCU expression in both BSF (Fig. 1h) and PCF (Fig. 1i) trypanosomes. All further phenotypic analyses were performed on day 4 of RNAi induction for both PCF and BSF trypanosomes, unless indicated otherwise.

RNAi of TbMCU reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake

Mitochondrial Ca2+ ([Ca2+]m] was significantly decreased under resting conditions in TbMCU knockdown PCF trypanosomes (Supplementary Fig. S1c) while cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i] was not affected (Supplementary Fig. S1d). To determine their ability to take up Ca2+, we selectively permeabilized the plasma membrane of PCF trypanosomes with digitonin, as described before 1, and monitored Ca2+ uptake with Calcium Green-5N. Fig. 2a shows that when 50 μM digitonin was added to a reaction medium containing PCF trypanosomes, 2 mM succinate, and 40 μM Ca2+, a fast decrease in Ca2+ concentration started after a period of about 30 s and continued until addition of the uncoupler FCCP released the Ca2+ taken up. This Ca2+-transporting activity was fully abrogated by the addition of 40 μM of the MCU inhibitor ruthenium red, indicating that it is due to the MCU. Knockdown of the expression of TbMCU in PCF trypanosomes by RNAi significantly reduced their ability take up Ca2+, which was also abrogated by ruthenium red (Fig. 2a and b). Mitochondria of permeabilized control PCF trypanosomes were capable of buffering multiple pulses of exogenously added Ca2+ (Fig. 2c). However, TbMCU-silenced PCF trypanosomes showed a strong attenuated response, hardly buffering a single pulse (Figs. 2c and d).

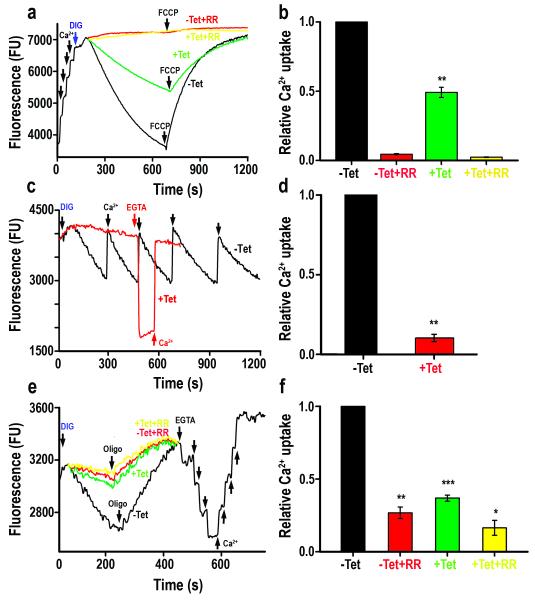

Figure 2. Silencing of TbMCU expression decreases Ca2+ uptake of digitonin-permeabilized PCF and BSF trypanosomes.

(a) The reaction buffer contained 2 mM succinate, and 1 μM Calcium Green 5-N. After several pulses of Ca2+ (8 μM final concentration) cells (5 × 107 trypanosomes grown in the absence (black tracing) or presence (green tracing) of tetracycline) were added to the reaction medium (2.45 ml) and the reaction was started adding 50 μM digitonin. Ruthenium red (RR, 40 μM, yellow and red tracing), and FCCP (5 μM) were added where indicated. A decrease in fluorescence indicates decreasing medium Ca2+ or increasing vesicular Ca2+. (b) Relative Ca2+ uptake at 700 sec as compared to that of control trypanosomes grown in the absence of tetracycline considered as 1.0 (−Tet) (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.001, Student’s t test). (c) Similar conditions as in (a) except that further CaCl2 additions (8 μM each time) were added to −Tet trypanosomes to show the high mitochondrial capacity to take up Ca2+. EGTA (8 μM) and CaCl2 (Ca2+) were added where indicated to show the presence of medium Ca2+. (d) Relative initial rate of Ca2+ uptake by +Tet as compared to −Tet trypanosomes (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.001, Student’s t test). (e) Representative traces of Ca2+ uptake kinetics in digitonin-permeabilized TbMCU BSF trypanosomes cultured in the absence (−Tet) or presence (+Tet) of tetracycline. The reactions were started adding 40 μM digitonin in the presence of 1 mM ATP and 500 μM sodium orthovanadate. Ca2+ uptake was monitored over time using 1 μM Calcium Green-5N. Ruthenium red (RR, 40 μM, yellow and red tracings), oligomycin (Oligo, 2.5 μg/ml), EGTA (0.4 μM) and CaCl2 (pulses of 0.4 μM) were added where indicated. (f) Relative Ca2+ uptake at 200 sec as compared to that of control BSF trypanosomes grown in the absence of tetracycline considered as 1 (−Tet) (means ± SD, n = 3, ** (−Tet ± RR) *** (−Tet/+Tet)* (+Tet ± RR), p < 0.001, Student’s t test).

The mitochondria of BSF trypanosomes lack cytochromes and does not have oxidative phosphorylation. Ca2+ uptake by these mitochondria can be measured by addition of ATP in the presence of sodium orthovanadate to inhibit other non-mitochondrial Ca2+-ATPases (Fig. 2e) 1. Ca2+ uptake was significantly lower when the expression of TbMCU was silenced by RNAi and in both cases it was almost completely abrogated by addition of ruthenium red (Figs. 2e and f). Addition of oligomycin released Ca2+ taken up indicating the inhibition of the ATP synthase working as an ATPase 1. Additions of EGTA and Ca2+ shown in Fig. 2e were done to calibrate the Ca2+ concentrations.

RNAi of TbMCU does not alter membrane potential

Previous work with the use of safranine determined that mitochondria in situ of PCF trypanosomes are able to build up and retain a membrane potential of the order of 140 mV 1. Fig. 3a shows that addition of ADP to these preparations was followed by the expected 28 small decrease in membrane potential that was inhibited by addition of the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin, indicating ADP phosphorylation. Addition of 40 μM CaCl2 was followed by a larger decrease compatible with the electrophoretic influx of Ca2+ into the mitochondria, which returned almost to basal levels after addition of 200 μM EGTA. Further addition of FCCP collapsed the membrane potential. Knockdown of the expression of TbMCU in PCF trypanosomes by RNAi significantly reduced the ability of their mitochondria to decrease the membrane potential due to Ca2+ uptake, without affecting the mitochondrial membrane potential or ADP phosphorylation (Fig. 3a and b), indicating that only the ability of taking up Ca2+ was affected.

Figure 3. Silencing of TbMCU expression does not affect the mitochondrial membrane potential of digitonin-permeabilized PCF and BSF trypanosomes.

(a) PCF trypanosomes (5 × 107 cells) were added to the reaction buffer (2.45 ml) containing 2 mM succinate, and 5 μM safranine, and the reaction was started with digitonin (50 μM). ADP (10 μM), oligomycin (Oligo, 2 μg/ml), CaCl2 (40 μM), EGTA (200 μM) and FCCP (10 μM) were added where indicated. (b) Changes in safranine fluorescence after addition of ADP or Ca2+ to −Tet and +Tet PCF trypanosomes (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.01, Student’s t test). (c) BSF trypanosomes (2 × 108 cells) were added to the reaction buffer (2.45 ml) containing EGTA (20 μM), ATP (1 mM), sodium orthovanadate (500 μM), and 12.5 μM safranine. The reaction was started with digitonin (40 μM). CaCl2 (50 μM), EGTA (200 μM) and FCCP (10 μM) were added where indicated. Bar = 10 μm (d and e) Changes in safranine fluorescence after addition of Ca2+ (d) or FCCP (e) to −Tet and +Tet BSF trypanosomes (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.01, Student’s t test).

When safranine was added to a reaction medium containing permeabilized BSF trypanosomes in the presence of ATP and vanadate, there was a decrease in fluorescence, which indicates stacking of safranine to the energized inner mitochondrial membrane 28. This decrease was completely reversed by oligomycin (Supplementary Fig. S1e), or by the protonophore FCCP (Fig. 3c). In contrast with the mitochondria of trypanosomes (Fig. 3a), the decrease in ΔΨ caused by Ca2+ was only partially reversed by EGTA probably indicating a higher sensitivity of these mitochondria to Ca2+ damage and opening of the permeability transition pore. The decrease in ΔΨ in BSF trypanosomes, in which TbMCU was silenced by RNAi, was significantly lower than in control cells (Figs. 3c, d and e).

Phenotypic changes after RNAi of TbMCU

Trypanosomes rely on amino acid catabolism when in their insect host, with a preference for L-proline 10. However, PCF prefer glucose when grown in medium rich in this sugar 10. Accordingly, silencing of TbMCU in PCF trypanosomes grown in glucose-rich medium (SDM-79) had a small effect on the AMP/ATP ratio after a short incubation in glucose-rich buffer but the ratio increased more significantly in the absence of glucose (Fig. 4a). To investigate the relevance of mitochondrial Ca2+ for proline metabolism we cultured PCF trypanosomes in glucose-depleted medium (SDM-80) 10 and found that silencing of TbMCU increased more than ~2 fold the AMP/ATP ratio of these cells (Fig. 4b). In agreement with these results, growth of the RNAi parasites in this medium was more strongly affected (Supplementary 2a) than in SDM-79 medium (Fig. 1e), suggesting that the decrease in ATP levels were not compatible with growth and survival.

Figure 4. Phenotypic changes after RNAi of TbMCU.

(a) Comparison of AMP/ATP ratios between PCF trypanosomes grown in the absence (−Tet) or presence (+Tet) of tetracycline to induce RNAi, and with or without glucose (Gl), expressed as fold increase (means ± SD, n = 3; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01, Student’s t test). (b) Comparison of AMP/ATP ratios between (−Tet) and (+Tet) PCF trypanosomes grown in a glucose-depleted medium (SDM-80) containing 5.2 mM L-proline for 2 days after 2-days growth in SDM-79 ± tetracycline, expressed as fold increase (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.01, Student’s t test). (c) Fluorescence microscopic images of TbATG8.2 in PCF trypanosomes cultured in SDM-79 in the absence (WT) or presence (RNAi) of tetracycline to induce RNAi; bars = 10 μm (d) Quantification of autophagosome formation in RNAi PCF trypanosomes grown in SDM-79 or SDM-80 medium in the presence (+Tet) or absence (−Tet) of tetracycline. Over 500 cells from three experiments with 20 random fields/experiment were analyzed (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.001, Student’s t test). (e) Western blot analysis of TbATG8.2 or tubulin in PCF trypanosomes cultured in SDM-79 or SDM-80 in the absence (−Tet) or presence (+Tet) of tetracycline to induce RNAi. Cell lysates (30 μg) were fractionated in 12% urea-SDS-PAGE gel. Immunoblots were labeled with anti-TcATG8.2 or anti-tubulin antibody. (f) Quantification of ATG8.2-II/(ATG8.2-II + ATG8.2-I) presented as mean ratios ± SD (n = 3, ** p < 0.01, Student’s t test). (g) Groups of five mice were infected with WT T. brucei (black line) or trypanosomes transfected with the construct for RNAi of TbMCU (red line). Doxycycline (green line; 200 μg/ml) was given in the drinking water throughout a 30-day period. (h) Parasitemia levels in surviving mice were monitored at two-day intervals after infection. The results are means ± SD (n = 2).

Autophagy has been reported as a starvation response in different trypanosomatids (reviewed in 29,30), and block of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by inhibitors like Ru360 in DT40 cells 13 or knockdown of MCU in HeLa cells 27 were shown to increase autophagy as a survival mechanism. In agreement with those reports, knockdown of TbMCU expression by RNAi increased the percentage of cells with autophagosomes when grown in both SDM-79 and SDM-80 media (Fig. 4c and d). Elevated autophagy in knockdown cells was also detected by quantitative measurements of the autophagy marker Atg8.2-II (the ortholog of LC3-II in mammalian cells) 31 (Fig. 4e and f).

To investigate whether TbMCU is essential for the establishment of an infection in animals, we inoculated groups of 5-6 mice with wild type and RNAi transgenic BSF trypanosomes for TbMCU. Induction of RNAi was obtained by feeding mice with water containing doxycycline. Mice infected with the wild type and non-induced cells died 5-7 days post-infection or had to be euthanized for ethical reasons when reaching parasitemias of 108/ml (Fig. 4g and h). This was in contrast to the doxycycline-fed mice, where most mice survived more than 10 days. By 16 days, all, except one doxycycline-fed mice died, suggesting that a small number of parasites (RNAi escape mutants) are able to survive in the presence of doxycycline and subsequently outgrow and kill the mice. In agreement with this suggestion, tetracycline addition in vitro reduced but did not completely eliminate the expression of TbMCU (Fig. 1h). Doxycycline alone is known to have no effects on mice survival under the conditions used 32.

TbMCU is essential in BSF trypanosomes

Silencing of TbMCU by RNAi caused marked growth defects in vitro (Fig. 1d-e) and in vivo (Fig. 4g-h). To confirm the essentiality of TbMCU, we analyzed the phenotypic changes of BSF trypanosomes with a conditional knockout (KO) of the gene. In these cells, we replaced both TbMCU alleles with drug resistance genes (Supplementary Fig. S3a-c, Supplementary Table S1), but, since TbMCU could be required for growth, we introduced an ectopic copy of the TbMCU gene tagged with HA, whose expression depended on presence of tetracycline in the culture medium. Growth of the parasites in culture was greatly decreased in the absence of tetracycline and the cells died after 4-5 days of culture (Fig. 5a). The genotype of the mutant cell line was verified by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 5b). Levels of mRNA in the presence or absence of tetracycline were analyzed by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 5c). As expected, no TbMCU mRNA was detected in the absence of tetracycline for the KO cell line. In the presence of tetracycline, TbMCU mRNA level of the KO mutant was comparable to that of wild type cells because of the ectopic gene expression. After removal of tetracycline the expression level of ectopic TbMCU in these mutants was confirmed by western blot (Fig. 5d) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 5e) analyses using mouse monoclonal antibodies against HA. Mitochondria of permeabilized conditional knockout BSF trypanosomes obtained after 4 days in the absence of tetracycline showed a profound and complete loss of Ca2+ uptake in response to pulses of Ca2+ (Fig. 5f), while their mitochondrial membrane potential remained unaffected (Fig. 5g-i). In vivo studies done in mice with the conditional knockouts showed higher survival of mice infected with mutant parasites, compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. S2b and S2c). Wild type and doxycycline-treated mice died by 5-7 days, while in the absence of doxycycline most mice, except two that died by day 15, survived for the duration of the experiment (30 days) (Supplementary Fig. S2b) and parasitemia was not detectable after 15 days in these surviving mice (Supplementary Fig. S2c).

Figure 5. Changes in BSF trypanosomes after conditional knockout of TbMCU.

(a) Growth of TbMCU-knockout BSF in the absence (black line) or presence (red line) of 1 μg/ml tetracycline for the indicated number of days. Addition of 10 mM threonine to the medium (green line) partially rescued the mutant BSF trypanosomes but had no effect on +Tet cells (yellow line) (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.001, Student’s t test). (b) Southern blot analysis of the BSF conditional knockouts. Genomic DNA from the T. brucei SM parental strain (+/+), single- (+/−) or double-allele (−/-) knockout cells. (c) Northern blot analysis of wild-type (WT) and TbMCU-knockout BSF cultured in the presence (+Tet) or absence (−Tet) of tetracycline for 2 days. Tubulin is shown as a loading control (bottom panel). (d) Western blot analysis of total cell lysates. Proteins from BSF trypanosomes cultured in the presence (+Tet) or absence (−Tet) of tetracycline were detected using anti-HA antibody. VDAC was used as loading control. (e) Immunofluorescence analysis of control (upper panels) and TbMCU-knockout (lower panels) trypanosomes. TbMCU co-localized with MitoTracker (MT) in the control parasites (+Tet; PCC = 0.808). Bar = 10 μm. (f) Conditional TbMCU-knockout BSF trypanosomes were grown in the presence (+Tet) or absence (−Tet) of tetracycline for 2 days. BSF trypanosomes (2 × 108 cells) were incubated as in Fig. 2e. Multiple pulses of CaCl2 (arrowheads) were added to a final concentration of 20 μM. A representative trace (red or black) of Ca2+ uptake from one of 3 independent experiments is shown. (g) Representative traces of mitochondrial membrane potential of digitonin-permeabilized BSF trypanosomes grown in the presence (+Tet) or absence (−Tet) of tetracycline. The reactions were incubated as in Fig. 3c. CaCl2 (50 μM), EGTA (200 μM) and FCCP (10 μM) were added where indicated. (h and i), Changes in safranine fluorescence after addition of Ca2+ (h, as in g, but 25, 50 and 100 μM CaCl2) or FCCP (i) to +Tet and −Tet BSF trypanosomes (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.001, Student’s t test).

Although none of the dehydrogenases (PDHs) stimulated by Ca2+ in vertebrates have been studied in detail in trypanosomatids 17, the PDH E1α subunit seems to possess phosphorylation sites with similarity to those of the mammalian enzyme 33, suggesting that, as the mammalian enzyme, it could be activated by Ca2+-stimulated dephosphorylation. Generation of acetyl-CoA by the pyruvate dehydrogenase is required for the formation of mitochondrial acetate, which translocates to the cytosol and is used for fatty acid synthesis 34, a process that is required for efficient mouse infections by BSF trypanosomes 35. Acetyl-CoA is also used for mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis through a FAS II pathway, which is also essential in BSF trypanosomes 36. In this regard, we were able to detect PDH activity in BSF trypanosome lysates, although at lower levels than in PCF trypanosomes (Supplementary Fig. S2d).

T. brucei possess a threonine dehydrogenase 37 that can also produce acetyl-CoA bypassing the need of pyruvate dehydrogenase and presumably without a mitochondrial Ca2+ requirement. In agreement with this hypothesis, addition of 10 mM threonine to the culture medium could partially rescue the BSF trypanosome mutants (Fig. 5a).

Overexpression of TbMCU increases oxidative stress

Overexpressed TbMCU was also localized to the mitochondria of PCF trypanosomes as detected by its co-localization with MitoTracker (Supplementary Fig. S2e and S2f). Mitochondrial (Fig. 6a and b) but not cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 6c) was constitutively elevated under resting conditions in TbMCU overexpressing PCF trypanosomes. In agreement with these results, overexpression of TbMCU increased the ability of their mitochondria to accumulate Ca2+ in response to Ca2+ pulses (Fig. 6d and e), without affecting the mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 6f, and g).

Figure 6. Changes upon overexpression of TbMCU.

(a) Rhod-2 fluorescence in control or overexpressing TbMCU (TbMCU-OE) PCF. Bar = 10 μm. (b and c) Rhod-2 (mitochondrial) (b) and Fluo-4 (cytosolic) (c) fluorescence in control (−Tet) and overexpressing TbMCU (+Tet) PCF (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.05, Student’s t test); ns, not significant. (d) Ca2+ uptake by digitonin-permeabilized PCF overexpressing TbMCU. Trypanosomes were incubated as in Fig. 2c. Multiple pulses of CaCl2 (arrowheads) were added to a final concentration of 8 μM. (e) Ca2+ uptake in TbMCU-OE PCF (+Tet) 200 s after addition of Ca2+, as compared to uninduced trypanosomes considered as 1 (−Tet) (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.01, Student’s t test). (f) Mitochondrial membrane potential of digitonin-permeabilized control (−Tet) and TbMCU-OE (+Tet) PCF. The reactions were incubated as in Fig. 3a. (g) Changes in safranine fluorescence after addition of ADP, Ca2+, or FCCP to −Tet and +Tet PCF trypanosomes (means ± SD, n = 3, ** p < 0.001, Student’s t test). (h) Mitochondrial oxidative stress as measured with MitoSOX Red in control (C) and TbMCU-overexpressing (OE) PCF permeabilized with 50 μM digitonin in the presence of 0.4 mM Ca2+. Controls were treated with 2 μM antimycin A (C +AA); or were trypanosomes exposed to 0.4 mM Ca2+ in the absence of digitonin (−DIG +Ca2+), and trypanosomes permeabilized with digitonin in the absence of Ca2+ (C, yellow line). (i) Quantification of change at 900 seconds. Results are expressed as mean fluorescence ± SD (n = 3, ** p < 0.001, Student’s t test). (j) Growth of trypanosomes in the absence (control, black lines) or presence (TbMCU-OE, red lines) of 1 μg/ml tetracycline (means ± SD, n = 3). (k) Dead cells in representative fields of control (−Tet) and TbMCU-OE (+Tet) PCF are indicated (white arrows). Bar = 10 μm. (l) Cell viability upon apoptotic challenge of control (−Tet) or TbMCU-OE (+Tet) PCF trypanosomes with H2O2 and C2-ceramide. The percentage of cell death was obtained from means ± SD by analyzing >60 fields (including >400 cells) (n = 3). ** p < 0.01, Student’s t test.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ overload is known to generate oxidative stress and sensitize cells to apoptotic stimuli. Accordingly, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was increased in TbMCU overexpressing PCF trypanosomes as compared with control cells and to comparable levels to those produced by antimycin A addition (Fig. 6h and i). Growth in rich medium was slightly affected by overexpression of TbMCU (Fig. 6j). However, overexpression of TbMCU sensitized PCF trypanosomes to apoptopic challenge. Microscopy counts of cell viability after treatment with C2-ceramide or H2O2 showed that TbMCU overexpressing trypanosomes were more efficiently killed (Fig. 6k and l), in agreement with the notion that mitochondrial Ca2+ loading synergizes with apoptotic stimuli 38,39.

Discussion

The most significant finding of our studies is that the mitochondrial calcium uniporter is essential in BSF trypanosomes, which are organisms devoid of oxidative phosphorylation. This pathway has been reported to be the main target of intramitochondrial Ca2+ in vertebrate cells 13-16. The partial rescue by threonine of the lethal effect of the TbMCU knockout suggests that, in contrast to what occurs in vertebrate cells, TbMCU in BSF trypanosomes appears necessary for the generation of acetyl-CoA, not as a substrate of the Krebs cycle (TCA) that is absent, but as either a source of intramitochondrial ATP through substrate level phosphorylation, needed for intramitochondrial anabolic reactions 40 or maintenance of the membrane potential by the ATPase 1, or for mitochondrial 36 and/or cytosolic fatty acid synthesis 41.

The current metabolic model in BSF trypanosomes excludes a role of the mitochondrion in the cellular provision of ATP 40,42. BSF trypanosomes appear to rely exclusively on glycolysis, with cytosolic generation of ATP and excretion of pyruvate 43. However, our results indicate that some Ca2+-stimulated pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity is present in their mitochondria and that dephosphorylation of PDH E1 α subunit (E1α) is activated by Ca2+, as occurs in vertebrate mitochondria. In addition to our detection of PDH activity in lysates of BSF trypanosomes, recent proteomic studies have detected the presence of not only PDH E1α and E1β 44 but also of the PDH E2 and E3 subunits 45,46. An ortholog of the PDH phosphatase that activates the PDH E1α subunit (Tb927.5.1660) was also identified 46. Studies of purified PDH from bovine kidney and heart mitochondria 47 and pig heart mitochondria 48 have identified the Ser-5 of the PDH E1α sequence: Tyr-His-Gly-His-Ser-Met-Ser-Asn-Pro-Gly-Val-Ser-Tyr-Arg, as the site responsible for inactivation by phosphorylation by their intrinsic kinase. A similar peptide Tyr-Met-Gly-His-Ser-Met-Ser-Asp-Pro-Asp-Ser-Gln-Tyr-Arg is present in the T. brucei (Tb927.10.12700) ortholog. The presence of this specific serine residue in the T. brucei PDH could account for a phosphorylation/dephosphorylation model resembling mammalian E1α. The threonine dehydrogenase (TDH) reaction would bypass the need of a Ca2+-stimulated step in the mutant parasites.

Acetyl-CoA generated from pyruvate in the reaction catalyzed by PDH is converted to acetate by the acetate:succinate CoA-transferase (ASCT) 49 or by an acetyl-CoA thioesterase 34 in PCF trypanosomes. ASCT transfers the CoA group of acetyl-CoA to succinate to form succinyl-CoA, which is consequently converted back to succinate by succinyl-CoA synthase (SCoAS) with a net production of one molecule of ATP per molecule of acetyl-CoA 34,49. ATP generated by this reaction, if it occurs in BSF, or alternatively, incorporated from the cytosol by the recently described ADP/ATP carrier TbMCP5 that is also present in BSF trypanosomes 50, could be used for intramitochondrial metabolic reactions or for the ATPase to maintain the membrane potential. Acetate formed could then be transferred to the cytosol where is converted back into acetyl-CoA by acetyl-Co synthetase and can be used for fatty acid synthesis 34. Cytosolic fatty acid synthesis appears to be essential when the BSF trypanosomes are in their mammalian host 35 despite their non-essentiality under culture conditions 41. Alternatively, acetyl-CoA could be used for mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis, which is known to result in the generation of lipoic acid and myristic acid, a pathway that is essential in BSF trypanosomes 36. Fig. 7a shows a scheme of these reactions occurring in BSF trypanosomes.

Figure 7. Energy metabolism in T. brucei.

Scheme of metabolic pathways in BSF (a) and PCF (b) trypanosomes. Arrows indicate steps of glucose, proline, and threonine metabolism and glycerolipid biosynthesis; dashed arrows indicate steps for which no evidence of flux is available 34. Abbreviations: A, ATPase (a) or ATP synthase (b); AcCoA, acetyl-CoA; Cit, citrate, CoASH, coenzyme A; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; FAS II, type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; G3P, glycerol 3-phosphate; GPDH, glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; KG, 2-ketoglutarate; Mal, malate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Pyr, pyruvate; Resp. Ch., respiratory chain; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; UQ, ubiquinone. Enzymes are: 1, pyruvate dehydrogenase; 2, acetyl-CoA thioesterase; 3, acetate:succinate CoA-transferase; 4, succinyl-CoA synthetase; 5, F0F1-ATP synthase; 6, acetyl-CoA synthetase; TAO, trypanosome alternative oxidase; 7, threonine dehydrogenase; 8, proline dehydrogenase. Activities potentially stimulated by Ca2+ are indicated.

Similarly to what occurs in vertebrate cells, and in contrast to what occurs in BSF trypanosomes, reduction of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport in PCF trypanosomes in a glucose-depleted environment, or when proline is used as substrate, resulted in an increased AMP/ATP ratio. It has been demonstrated 51 that in a glucose-depleted environment, conditions present in the insect vector, PCF trypanosomes increase the rate of proline consumption and are more sensitive to oligomycin supporting the view that oxidative phosphorylation becomes essential. Proline is oxidized to glutamate through two mitochondrial steps. The first catalyzed by proline dehydrogenase or proline oxidase oxidizes L-proline to Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate, which is further hydrolyzed non-enzymatically to glutamic acid gamma semialdhyde (SAG). In a second enzymatic step Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate is oxidized to L-glutamate by Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase. Glutamate can be deaminated by transaminases or dehydrogenases to be converted into α-ketoglutarate, which through some of the Krebs cycle reactions is converted into succinate. Interestingly, the first enzyme in the proline metabolic pathway, proline dehydrogenase (Tb927.7.210), possesses an EF-hand domain and it is possibly the target for intramitochondrial Ca2+ under these conditions. Fig. 7b shows the possible reactions occurring in PCF trypanosomes.

Downregulation of TbMCU in PCF trypanosomes resulted in increased autophagy, as it has also been reported when MCU was downregulated in mammalian cells 27. It has been reported 31 that autophagy has a role in PCF trypanosomes death, although it can also be considered as a survival mechanism 13. Although the percentage of cells with autophagosomes increased by 33% in cells grown in SDM-80, as compared to cells grown in SDM-79 medium, the difference was not significant (p = 0.065, Student’s t test). It is known that the breakdown products derived from autophagy have a dual role providing substrates for both energy generation and biosynthesis 52. Although we cannot rule out other mechanisms, one possible explanation for the lack of difference is that the autophagic process requires energy, for example for the activity of the different kinases involved as well as for the synthesis/incorporation of the phagosomal membrane components 52. Most of the products of autophagy such as amino acids and lipids yield ATP through oxidative phosphorylation 52, which would be deficient in the absence of TbMCU, while glycogen reserves are absent in trypanosomatids. The considerable increase in the AMP/ATP ratio in cells grown in proline-rich medium (SDM-80) in the absence of oxidative phosphorylation would prevent an increase in autophagosome formation over the level observed in cells grown in glucose-rich medium (SDM-79).

Overexpression of TbMCU in PCF trypanosomes increased the ability of their mitochondria to take up Ca2+, resulting in mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, oxidative stress, and higher sensitivity of these mutants to pro-apoptotic stimuli. These results are in agreement with the results obtained after overexpression of MCU in HeLa cells 21. However, other authors 20 did not detect marked gain of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in HeLa cells overexpressing MCU. The role of mitochondrial Ca2+ in activation of programmed cell death in mammalian cells is well recognized 53,54. Mitochondrial Ca2+ has also been recognized as important for apoptosis-like or programmed cell death (PCD) in trypanosomatids. Mitochondrial Ca2+ overload upon different triggers of cell death results in reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and release of cytochrome c 55. The production of ROS in T. brucei impairs mitochondrial Ca2+ transport, and leads to its accumulation in the nucleus and cell death 56. T. cruzi is highly resistant to the mitochondrial permeability transition 22, and apoptosis-like death upon mitochondrial Ca2+ overload is apparently dependent on ROS generation 57.

In vertebrate cells mitochondrial Ca2+ is important not only for the regulation of cellular ATP concentration but also for shaping Ca2+ signals 58-60. It is well established, through experiments using aequorin targeted to the mitochondria of T. brucei, that, as in vertebrate cells, intramitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations in T. brucei can reach values much higher than cytosolic Ca2+ rises when Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane or Ca2+ release from acidic calcium stores (acidocalcisomes) are stimulated 61. These results suggest a very close proximity of the sole mitochondrion of the parasites with the plasma membrane and acidocalcisomes and the presence of microdomains of high Ca2+ concentration in their vicinity. The recent finding of an IP3 receptor in acidocalcisomes of T. brucei 62 and of a close proximity of acidocalcisomes and mitochondria in trypanosomatids 63 are compatible with a role of IP3-stimulated Ca2+ release from acidocalcisomes and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake as a requirement for efficient mitochondrial metabolism and normal cell bioenergetics, as it has been described for the ER and mitochondria of vertebrate cells 13. In this regard TbIP3R was found to be essential even in BSF trypanosomes 62. One of the main functions of the MCU in trypanosomes would be, as in vertebrate mitochondria, to shape the amplitude and spatiotemporal patterns of cytosolic Ca2+ increases 17.

In summary, our results indicate for the first time that the MCU is essential for the survival of a eukaryotic organism. In contrast to what has been recently described in some mammalian cells, where transient receptor potential 3 channels also regulate mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake 64, TbMCU is the sole responsible for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in T. brucei. This channel is essential for growth in vitro and in vivo, and has important roles in the regulation of the cell bioenergetics in the two main life stages investigated.

Methods

Reagents

The p2T7Ti vector 65 was a gift from Dr. John Donelson (University of Iowa). Rabbit polyclonal antibody against TcATG8.2 was a gift from Dr. Vanina Alvarez (Universidad Nacional de San Martin, Argentina). Rabbit polyclonal antibody against TbVDAC was a gift from Dr. Minu Chaudhuri (Meharry Medical College, TN). Other reagents used are described in Supplementary Methods.

Culture methods

T. brucei PCF (wild type and 29-13 strains) and BSF (wild type and single marker strains) were used. PCF 29-13 (T7RNAP NEO TETR HYG) co-expressing T7 RNA polymerase and Tet repressor were a gift from Dr. George A. M. Cross (Rockefeller University, NY) and were grown in SDM-79 medium 66 supplemented with hemin (7.5 μg/mL) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and at 27°C in the presence of G418 (15 μg/ml) and hygromycin (50 μg/ml) to maintain the integrated genes for T7 RNA polymerase and tetracycline repressor, respectively. BSF (single marker strain) were also a gift from Dr. G.A.M. Cross and were grown at 37°C in HMI-9 medium 66 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% serum plus (JRH Biosciences, Inc.), and 2.5 μg/ml G418.

Anti-TbMCU antibodies

The cDNA fragment of TbMCU corresponding to amino acids 49-200 was amplified by PCR and cloned in frame into the expression vector pET32 EK/Lic (Novagen) to generate pET32-TbMCU. The correct plasmid pET32-TbMCU was confirmed by sequencing and then transformed into E. coli OverExpress C43 (DE3) strain (Lucigen, WI). His-tagged TbMCU fusion protein was affinity purified with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) based on the manufacturer’s protocol. The purified protein was used to immunize mice and polyclonal antibodies were purified from anti-serum with Protein G Agarose Resins (Qiagen). The animal protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Georgia.

Western blot analyses

The blots were incubated with mouse antibodies against TbMCU (1:500), rabbit antibodies against GFP (1:10,000), mouse antibodies against HA (1:2,500), rabbit antibodies against TcATG8.2 (1:1,000), rabbit antibodies against TbVDAC (1:2,000), or rabbit antibodies against tubulin (1:20,000) for 1 h. After 5 washings with PBS-T, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) antibody at a dilution of 1:20,000 for 1 h. After washing 5 times with PBS-T, the immunoblots were visualized using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Full-length images of gels and immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4.

TbMCU RNAi constructs

To knockdown the expression of the TbMCU gene (Tb927.11.1350) by double-stranded RNA expression, the inducible T7 RNA polymerase-based protein expression system and the p2T7Ti vector with dual-inducible T7 promoters were employed. A 921-bp cDNA fragment of TbMCU (targeted to the nucleotides 4-924 of the open reading frame- ORF) was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CCCAAGCTTTGGAGGCCTTATACTTTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CGGGATCCTCAGTGATGTTTAAACCACTTCCG-3′ (where the underlined nucleotides indicate the introduced BamHI and HindIII sites, respectively) digested with BamHI and HindIII, and then cloned into the enzyme-cut p2T7Ti vector to generate p2T7(TbMCU). The recombinant construct p2T7(TbMCU) was confirmed by sequencing at the DNA Analysis Facility at Yale University (New Haven, CT), NotI-linearized, and then purified with QIAGEN’s DNA purification kit for cell transfections. TbMCU has a novel nucleotide sequence without homologues (> 20 nucleotide identity) in T. brucei genome/transcript databases (TriTrypDB), suggesting the absence of any other potential gene targets. Cell transfections are described in Supplementary Methods.

GFP-tagged or HA-tagged TbMCUs

To construct C-terminally enhanced GFP-tagged TbMCU for localization of TbMCU in T. brucei, the full-length cDNA of TbMCU was amplified from T. brucei genomic DNA by PCR using the forward primer 5′-CCCAAGCTTATGTGGAGGCCTTATACTTTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCGCTCGAGGTGATGTTTAAACCACTTCCG-3′ (where the underlined nucleotides indicate the introduced HindIII and XhoI sites, respectively). The PCR product was digested with HindIII and XhoI and then cloned in frame into the insertion sites of TbVTC1 in the pUB39 (TbVTC1-GFP) vector 66 to replace TbVTC1 and thus generate pUB39(TbMCU-GFP). To construct C-terminally HA-tagged TbMCU for overexpression or conditional knockout of TbMCU in BSF as described below, the full-length cDNA of TbMCU (924 bp) was amplified with Pfu Ultra HF DNA polymerase (Agilent) from T. brucei genomic DNA by PCR using the forward primer 5′-CCCAAGCTTATGTGGAGGCCTTATACTTTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′CGGGATCCCTATG CGTAATCGGGCACATCGTACGGGTATGCGTAGTCGGGCACGTCGTATGGGTACGCGTAATCAGGCACATCGTAAGGGTAGTGATGTTTAAACCATTCCG-3′ (where the underlined nucleotides indicate the introduced HindIII and BamHI sites, respectively, and where the italicized nucleotides indicate 3 × HA coding sequence in the reverse primer), and then cloned into the enzyme-cut pLew100v5_bsd vector to generate pLew100(TbMCU-HA). The double-stranded sequences of GFP-tagged TbMCU in the expression vector pUB39 and HA-tagged TbMCU in the expression vector pLew100v5_bsd were confirmed by sequencing as indicated above. The correct constructs pUB39(TbMCU-GFP) and pLew100(TbMCU-HA) with the inducible T7 RNA polymerase-based protein expression system were linearized by NotI and transfected into T. brucei PCF 29-13 or BSF single marker (SM) trypanosomes.

Northern and Southern blot analyses

The TbMCU probe was generated from p2T7(TbMCU), by PCR using the same primers described in the text, and labeled with [α-32P]-dCTP using a Prime-a-Gene Labeling System according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The [α-32P]-dCTP-labeled probe of Tbβ-tubulin gene (GeneDB Tb927.1.2390) was generated from T. brucei genomic DNA by PCR using the gene-specific primers (5′-ATGCGCGAAAATCGTCTGCGTTCAGG-3′ and 5′-AGTGCAGACGCGGGAATGGGACAAG-3′). For Southern blot analysis, 10 μg ClaI-digested genomic DNA was separated on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred to a Zeta-Probe nylon membrane. The membrane was probed with a 295-bp 32P-labeled PCR product of the TbMCU 3′UTR (Supplementary Fig. S3) generated with the Prime-a-Gene labeling system. The RNA- or DNA-bound membranes were hybridized with the 32P-labeled TbMCU or Tbβ-tubulin probe in 0.5 M Na2HPO4, pH 7.4 and 7% SDS at 65 °C overnight with agitation. After hybridization, the membranes were washed twice for 10 min each at 68 °C with 1 × SSC and 0.1% SDS and then twice for 30 min at 65 °C with 0.1 × SSC and 0.1% SDS. The hybridized blots were visualized by autoradiography.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

To determine the localization and expression of TbMCU in T. brucei, trypanosome live cells were labeled for 30 min with Mitotracker Red CMXRos (Invitrogen) at 50 nM in trypanosome culture medium. Bloodstream trypanosomes were washed in ice-cold PBS with 1% glucose and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C for 1 h. Procyclic trypanosomes were washed with PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at RT for 1 h. The fixed parasites were washed twice with PBS, allowed to adhere to poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips, and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS for 3 min for PCF or 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 5 min for BSF. After blocking with PBS containing 3% BSA, 1% fish gelatin, 50 mM NH4Cl and 5% goat serum for 1 h, trypanosomes were stained in 3% BSA/PBS with the purified HA.11 clone 16B12 monoclonal antibody against HA (1:250), rabbit polyclonal antibody against GFP (1:1,000), rabbit polyclonal antibody against TcATG8.2 (1:250), or mouse polyclonal antibody against TbMCU (1:50) for 1 h. After thoroughly washing with PBS containing 3% BSA, cells were incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody at 1:1,000 for 1 h. The cells were counterstained with DAPI before mounting with Gold ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes). Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescent optical images were captured using an Olympus IX-71 inverted fluorescence microscope with a Photometrix CoolSnapHQ CCD camera driven by DeltaVision software (Applied Precision, Seattle, WA). Images were deconvolved for 15 cycles using Softwarx deconvolution software. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCC) were calculated using the Softwarx software by measuring the whole cell images.

TbMCU conditional knockout mutants

To replace the endogenous TbMCU genes, phleomycin- and puromycin-resistance gene cassettes were generated by PCR amplification using the plasmids p2T7Ti and pMOTag2T as templates with the gene-specific primers, which were designed to bind the 5′- and 3′-termini of the resistance genes followed by 149-bp 5′UTR or 147-bp 3′UTR of TbMCU. To express the ectopic copy of TbMCU, the inducible expression construct pLew100 (TbMCU-HA) was generated as described above. The resistance gene cassettes and NotI-linearized pLew100(TbMCU-HA) (~10 μg) were introduced into T. brucei BSF SM cells by nucleofection using program X-001 and Amaxa Human T-solution following the manufacturer’s instructions. After nucleofection, clones were obtained by limiting dilution and antibiotic selection (2.5 μg/ml phleomycin, 5 μg/ml blasticidin or/and 0.1 μg/ml puromycin). The correct gene replacement or integration in the genome was confirmed by PCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3), followed by Southern blot analysis. TbMCU conditional knockout BSF mutants were maintained in HMI-9 with 1 μg/ml tetracycline, 2.5 μg/ml G418, and 5 μg/ml blasticidin. To remove tetracycline and shut down expression of ectopic TbMCU, trypanosomes were washed twice and resuspended in culture medium lacking tetracycline.

Ca2+ uptake by digitonin-permeabilized T. brucei

The uptake of Ca2+ by permeabilized T. brucei was assayed by fluorescence measurements at 28 °C using Calcium Green-5N. For PCF, trypanosome cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 7 min and washed twice with cold buffer A with glucose, which contained 116 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 5.5 mM D-glucose, and 50 mM Hepes at pH7.0. PCF cells were resuspended to a final density of 1 × 109 cells per ml in the buffer A with glucose and kept on ice. For BSF, trypanosome cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 7 min and washed twice with cold separation buffer, which contained 44 mM NaCl, 55 mM D-glucose, 57 mM Na2HPO4, and 3 mM KH2PO4 at pH 8.0. BSF trypanosomes were resuspended to a density of 2 × 107 cells per ml in the separation buffer and kept on ice. Before each experiment, a 10-ml aliquot of the BSF cells was concentrated to 50-μl by centrifugation at 1,600 g at RT for 3 min. A 50-μl aliquot of PCF (5 × 107 cells) or BSF (2 × 108 cells) of the cell suspension was added to the reaction buffer (125 mM sucrose, 65 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes-KOH buffer, pH 7.2, 1 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM potassium phosphate; 2.45 ml) containing 1 μM Calcium Green-5N and the reagents indicated in the figure legends. Ca2+ uptake by the cells was initiated by the addition of 50 μM digitonin (for PCF) or 40 μM digitonin (for BSF). Fluorescence changes were monitored in a F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi) with excitation at 490 nm and emission at 525 nm. Permeabilized cells grown in the presence of tetracycline under the assay conditions used did not show any fluorescence (excitation at 390 nm and emission at 400-650 nm) that could be attributed to tetracycline or its complexes.

Mitochondrial membrane potential and phosphorylation

Estimation of mitochondrial membrane potential in situ was done spectrofluorometrically using the indicating dye safranine 28. T. brucei PCF and BSF trypanosomes were incubated at 28 °C in the media described in the figure legends. Fluorescence changes were monitored on an Hitachi 4500 spectrofluorometer (Excitation = 496 nm; Emission = 586 nm).

Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations

T. brucei PCF cells were collected by centrifugation and suspended in 5 ml buffer A with glucose containing 2 μM Rhod-2 AM and 0.02% Pluronic F127. After incubation at 27 °C for 50 min in the dark with gentle shaking, cells loaded with Rhod-2 dye were washed and then re-loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4 AM for additional 30 min at 27 °C, followed by an additional 10-min incubation in a dye-free buffer A with glucose. Cells were resuspended to a final density of 1×109 cells/ml in buffer A with glucose and kept on ice. A 100-μl aliquot (1×108 cells) of the cell suspension was added to the 1.9-ml reaction buffer. The cytoplasmic and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration of cells was monitored in a fluorometer with excitation at 552 nm and emission at 581 nm for Rhod-2 and excitation at 494 nm and emission at 516 nm for Fluo-4, respectively. Fluorescence imaging of [Ca2+]m was carried out by using an Olympus IX-71 inverted fluorescence microscope with a Photometrix CoolSnapHQ CCD camera driven by DeltaVision software.

Mitochondrial oxidative stress

Mitochondrial ROS production was measured during the exposure of PCF trypanosomes to digitonin in the presence or absence of Ca2+ using the fluorescent, mitochondrially-targeted probe MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen) as described 57 with some modifications. PCF trypanosomes (2.5 × 108 cells/ml) were loaded with 5 μM MitoSOX Red in buffer A with glucose for 10 min at 27 °C and washed once with the same buffer. Cells were resuspended to a final density of 1 × 109 cells per ml in the buffer A with glucose and kept on ice. A 100-μl aliquot (1 × 108 cells) of the cell suspension was added to the reaction buffer with or without 0.4 mM Ca2+ and the reagents indicated in the figure legends. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 50 μM digitonin. Fluorescence changes were monitored in a fluorometer with excitation at 510 nm and emission at 580 nm.

Adenine nucleotide levels

TbMCU RNAi PCF trypanosomes were cultivated in SDM-79 for 4 days with or without tetracycline or in a glucose-depleted medium (SDM-80) containing 5.2 mM L-proline 51 for 2 days in the absence or presence of tetracycline after a 2-day culture in SDM-79 with or without tetracycline. Cells were harvested and washed once with cold buffer A. The cells grown for 4 days in SDM-79 medium were further incubated in buffer A with or without glucose for 1 h at room temperature. After washing or incubation, 1 × 108 cells per treatment were centrifuged, and resuspended in 100 μl of buffer A, and then lysed on ice for 30 min by addition of 300 μl of 0.5 M HClO4. The lysates were neutralized (pH 6.5) by addition of ~150 μl of 0.72 M KOH/0.6 M KHCO3. ATP, ADP, and AMP in extracted samples were quantified by a luciferin-luciferase bioluminescence assay in a luminometer as described 67,68 with some modifications. We used an ATP Determination Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with adenylate kinase (AK) and/or nucleoside-diphosphate kinase (NDK) (Sigma). To determine the amount of adenine nucleotides four measurements were taken of three different reactions for each sample by endpoint determination of the ATP concentration: one reaction without addition of any ATP-generating enzyme (for ATP), another reaction adding NDK (for ATP + ADP), and the third reaction adding both AK and NDK (for ATP + ADP + AMP). The amount of ADP was obtained by subtracting the ATP value from the (ATP + ADP) value and the amount of AMP was calculated from the difference between the (ATP + ADP + AMP) content and the (ATP + ADP) content.

Autophagy assay

Autophagosome formation in PCF trypanosomes grown in SDM-79 or SDM-80 media, as described above, was estimated by using the autophagy marker TbATG8.2 exactly as described 31. Effects of RNAi of TbMCU on autophagosome formation were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy and western blotting using anti-TcATG8.2 antibody as described above.

Enzyme assays

Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity was assayed by using a spectrophotometric method as described 69 with some modifications. Briefly, midlog phase PCF and BSF trypanosomes (~2 × 108 parasites) were washed in ice-cold PBS with 1% glucose and resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were lysed by freezing and thawing 5 times using liquid nitrogen (5 min) and a 37 °C water bath (1 min). The protein concentration was determined by using Bio-Rad Bradford assay kit. PDH assays were carried out at 30 °C in the reaction buffer containing 0.3 mM thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), 2 mM NAD+, 2.6 mM cysteine-HCl, 0.12 mM coenzyme A (CoA), 0.01 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 mM MOPS-HCl (pH 7.4). The reaction was initiated by adding 50 μl of cell lysate in a cuvette (light path = 1 cm) containing 2.95-ml reaction buffer. The reduction of NAD+ was monitored continuously for 5 min by the increase in absorbance (A) at 340 nm in a SpectraMax M2e cuvette reader (Molecular Devices). One unit of enzyme activity is the amount of PDH catalyzing the reduction of 1 μmol NAD+ per min.

Cell death assay

T. brucei transgenic PCF trypanosomes overexpressing TbMCU-HA (2 × 106 parasites/ml) grown in six well plates were treated with C2-Ceramide (40 μM) for 20 h or H2O2 (100 μM) for 4 h. Cell viability upon apoptotic challenge (H2O2 and C2-ceramide) were evaluated by using phase contrast microscopy and further confirmed by using 0.1% Trypan Blue staining. Rounded or straight cells without movement and with Trypan Blue dye staining were defined to be dead cells. The number of viable cells was determined by a hemocytometer using phase contrast microscopy and over 60 fields (including >400 cells) were analyzed from each experiment. The percentage of dead cells was obtained by analyzing 3 independent experiments and is expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analyses are described in Supplementary Methods.

In vivo studies

Exponentially growing cell lines (WT, RNAi, and conditional knockout mutants) were washed once in HMI-9 medium without selectable drugs and suspended in the same medium. Eight weeks-old female Balb/c mice (five to ten per group) were infected with a single intraperitoneal injection of 2 × 104 BSF trypanosomes in 0.2 ml HMI-9 medium. For the RNAi and conditional knockout mutants, a single inoculum of non-induced trypanosomes was used in two sets of mice with one group being given 200 μg/ml doxycycline in 5% sucrose in their drinking water, and the other group being supplied with drinking water containing 5% sucrose only. The drinking water with or without doxycycline was provided 3 days before infection, exchanging it every 2-3 days, and continuing throughout the 30-day period. Feeding doxycycline induced down-regulation of TbMCU expression in the RNAi parasites while doxycycline induced the expression of ectopic TbMCU in the conditional knockout parasites. Animals were fed ad libitum on standard chow. Parasitemia levels were monitored at 2-d intervals after infection 70. Mice showing impaired health status and/or with a parasite load > 108 cells per ml of blood were euthanized. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Georgia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Minu Chaudhuri and Vanina Alvarez for antibodies; George A.M. Cross, and John Donelson for reagents; Melissa Storey and Melina Galizzi for technical help for the mice immunizations and Christina Moore for the drawings of Fig. 7. This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant AI077538 (to R.D.) and FAPESP 11/50400-0 (to A.E.V.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

G.H., A.E.V., and R.D. designed and performed experiments. G.H., and R.D. wrote the manuscript. A.E.V. reviewed the manuscript.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Vercesi AE, Docampo R, Moreno SN. Energization-dependent Ca2+ accumulation in Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream and procyclic trypomastigotes mitochondria. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;56:251–257. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90174-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnaufer A, Clark-Walker GD, Steinberg AG, Stuart K. The F1-ATP synthase complex in bloodstream stage trypanosomes has an unusual and essential function. Embo J. 2005;24:4029–4040. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolan DP, Voorheis HP. The mitochondrion in bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei is energized by the electrogenic pumping of protons catalysed by the F1F0-ATPase. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown SV, Hosking P, Li J, Williams N. ATP synthase is responsible for maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential in bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:45–53. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.1.45-53.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balogun RA. Studies on the amino acids of the tse tse fly, Glossina morsitans, maintained on in vitro and in vivo feeding systems. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1974;49:215–222. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(74)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bursell E, Billing KJ, Hargrove JW, McCabe CT, Slack E. The supply of substrates to the flight muscle of tsetse flies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1973;67:296. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(73)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford WC, Bowman IB. Metabolism of proline by the culture midgut form of Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1973;67:257. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(73)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans DA, Brown RC. The utilization of glucose and proline by culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei. J Protozool. 1972;19:686–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1972.tb03561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ter Kuile BH, Opperdoes FR. Comparative physiology of two protozoan parasites, Leishmania donovani and Trypanosoma brucei, grown in chemostats. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2929–2934. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2929-2934.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coustou V, et al. Glucose-induced remodeling of intermediary and energy metabolism in procyclic Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16342–16354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zikova A, Schnaufer A, Dalley RA, Panigrahi AK, Stuart KD. The F0F1-ATP synthase complex contains novel subunits and is essential for procyclic Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000436. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderheyden N, Wong J, Docampo R. A pyruvate-proton symport and an H+-ATPase regulate the intracellular pH of Trypanosoma brucei at different stages of its life cycle. Biochem J. 2000;346:53–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardenas C, et al. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell. 2010;142:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denton RM, McCormack JG. Ca2+ as a second messenger within mitochondria of the heart and other tissues. Annu Rev Physiol. 1990;52:451–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Seitz MB, Thomas AP. Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell. 1995;82:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balaban RS. The role of Ca2+ signaling in the coordination of mitochondrial ATP production with cardiac work. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:1334–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Docampo R, Lukes J. Trypanosomes and the solution to a 50-year mitochondrial calcium mystery. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Luca HF, Engstrom GW. Ca2+ uptake by rat kidney mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1961;47:1744–1750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.11.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasington FD, Murphy JV. Ca ion uptake by rat kidney mitochondria and its dependence on respiration and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:2670–2677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baughman JM, et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Docampo R, Vercesi AE. Characteristics of Ca2+ transport by Trypanosoma cruzi mitochondria in situ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;272:122–129. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Docampo R, Vercesi AE. Ca2+ transport by coupled Trypanosoma cruzi mitochondria in situ. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:108–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carafoli E, Balcavage WX, Lehninger AL, Mattoon JR. Ca2+ metabolism in yeast cells and mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;205:18–26. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(70)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perocchi F, et al. MICU1 encodes a mitochondrial EF hand protein required for Ca2+ uptake. Nature. 2010;467:291–296. doi: 10.1038/nature09358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhuri D, Sancak Y, Mootha VK, Clapham DE. MCU encodes the pore conducting mitochondrial calcium currents. eLife. 2013;2:e00704. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallilankaraman K, et al. MCUR1 is an essential component of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that regulates cellular metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1336–1343. doi: 10.1038/ncb2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figueira TR, Melo DR, Vercesi AE, Castilho RF. Safranine as a fluorescent probe for the evaluation of mitochondrial membrane potential in isolated organelles and permeabilized cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;810:103–117. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-382-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarez VE, et al. Autophagy is involved in nutritional stress response and differentiation in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3454–3464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duszenko M, et al. Autophagy in protists. Autophagy. 2011;7:127–158. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.2.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li FJ, et al. A role of autophagy in Trypanosoma brucei cell death. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1242–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang G, et al. Adaptor protein-3 (AP-3) complex mediates the biogenesis of acidocalcisomes and is essential for growth and virulence of Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36619–36630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.284661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buscaglia CA, et al. A putative pyruvate dehydrogenase alpha subunit gene from Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1309:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Millerioux Y, et al. ATP synthesis-coupled and -uncoupled acetate production from acetyl-CoA by mitochondrial acetate:succinate CoA-transferase and acetyl-CoA thioesterase in Trypanosoma. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17186–17197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vigueira PA, Paul KS. Requirement for acetyl-CoA carboxylase in Trypanosoma brucei is dependent upon the growth environment. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:117–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephens JL, Lee SH, Paul KS, Englund PT. Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis in Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4427–4436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linstead DJ, Klein RA, Cross GA. Threonine catabolism in Trypanosoma brucei. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;101:243–251. doi: 10.1099/00221287-101-2-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinton P, et al. The Ca2+ concentration of the endoplasmic reticulum is a key determinant of ceramide-induced apoptosis: significance for the molecular mechanism of Bcl-2 action. Embo J. 2001;20:2690–2701. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pacher P, Hajnoczky G. Propagation of the apoptotic signal by mitochondrial waves. Embo J. 2001;20:4107–4121. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Hellemond JJ, Opperdoes FR, Tielens AG. The extraordinary mitochondrion and unusual citric acid cycle in Trypanosoma brucei. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:967–971. doi: 10.1042/BST20050967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SH, Stephens JL, Paul KS, Englund PT. Fatty acid synthesis by elongases in trypanosomes. Cell. 2006;126:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michels PA, Bringaud F, Herman M, Hannaert V. Metabolic functions of glycosomes in trypanosomatids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1463–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haanstra JR, et al. Proliferating bloodstream-form Trypanosoma brucei use a negligible part of consumed glucose for anabolic processes. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vertommen D, et al. Differential expression of glycosomal and mitochondrial proteins in the two major life-cycle stages of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;158:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roldan A, Comini MA, Crispo M, Krauth-Siegel RL. Lipoamide dehydrogenase is essential for both bloodstream and procyclic Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81:623–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunasekera K, Wuthrich D, Braga-Lagache S, Heller M, Ochsenreiter T. Proteome remodelling during development from blood to insect-form Trypanosoma brucei quantified by SILAC and mass spectrometry. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:556. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeaman SJ, et al. Sites of phosphorylation on pyruvate dehydrogenase from bovine kidney and heart. Biochemistry. 1978;17:2364–2370. doi: 10.1021/bi00605a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugden PH, Kerbey AL, Randle PJ, Waller CA, Reid KB. Amino acid sequences around the sites of phosphorylation in the pig heart pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem J. 1979;181:419–426. doi: 10.1042/bj1810419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Hellemond JJ, Opperdoes FR, Tielens AG. Trypanosomatidae produce acetate via a mitochondrial acetate:succinate CoA transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3036–3041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pena-Diaz P, et al. Functional characterization of TbMCP5, a conserved and essential ADP/ATP carrier present in the mitochondrion of the human pathogen Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41861–41874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamour N, et al. Proline metabolism in procyclic Trypanosoma brucei is down-regulated in the presence of glucose. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11902–11910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science. 2010;330:1344–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1193497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:99–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Figueira TR, et al. Mitochondria as a source of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: from molecular mechanisms to human health. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:2029–2074. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smirlis D, Soteriadou K. Trypanosomatid apoptosis: ‘Apoptosis’ without the canonical regulators. Virulence. 2011;2:253–256. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.3.16278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ridgley EL, Xiong ZH, Ruben L. Reactive oxygen species activate a Ca2+-dependent cell death pathway in the unicellular organism Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Biochem J. 1999;340(Pt 1):33–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Irigoin F, et al. Mitochondrial calcium overload triggers complement-dependent superoxide-mediated programmed cell death in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem J. 2009;418:595–604. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hajnoczky G, Hager R, Thomas AP. Mitochondria suppress local feedback activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors by Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14157–14162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boitier E, Rea R, Duchen MR. Mitochondria exert a negative feedback on the propagation of intracellular Ca2+ waves in rat cortical astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:795–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tinel H, et al. Active mitochondria surrounding the pancreatic acinar granule region prevent spreading of inositol trisphosphate-evoked local cytosolic Ca2+ signals. Embo J. 1999;18:4999–5008. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiong ZH, Ridgley EL, Enis D, Olness F, Ruben L. Selective transfer of calcium from an acidic compartment to the mitochondrion of Trypanosoma brucei. Measurements with targeted aequorins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31022–31028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang G, Bartlett PJ, Thomas AP, Moreno SN, Docampo R. Acidocalcisomes of Trypanosoma brucei have an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor that is required for growth and infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1887–1892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216955110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girard-Dias W, Alcantara CL, Cunha-e-Silva N, de Souza W, Miranda K. On the ultrastructural organization of Trypanosoma cruzi using cryopreparation methods and electron tomography. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;138:821–831. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-1002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feng S, et al. Canonical transient receptor potential 3 channels regulate mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309531110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.LaCount DJ, Barrett B, Donelson JE. Trypanosoma brucei FLA1 is required for flagellum attachment and cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17580–17588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fang J, Rohloff P, Miranda K, Docampo R. Ablation of a small transmembrane protein of Trypanosoma brucei (TbVTC1) involved in the synthesis of polyphosphate alters acidocalcisome biogenesis and function, and leads to a cytokinesis defect. Biochem J. 2007;407:161–170. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jansson V, Jansson K. An enzymatic cycling assay for adenosine 5′-monophosphate using adenylate kinase, nucleoside-diphosphate kinase, and firefly luciferase. Anal Biochem. 2003;321:263–265. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spielmann H, Jacob-Muller U, Schulz P. Simple assay of 0.1-1.0 pmol of ATP, ADP, and AMP in single somatic cells using purified luciferin luciferase. Anal Biochem. 1981;113:172–178. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown JP, Perham RN. Selective inactivation of the transacylase components of the 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase multienzyme complexes of Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1976;155:419–427. doi: 10.1042/bj1550419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Herbert WJ, Lumsden WH. Trypanosoma brucei: a rapid “matching” method for estimating the host’s parasitemia. Exp Parasitol. 1976;40:427–431. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(76)90110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.