Abstract

The application of ribosome profiling and mass spectrometry technologies has recently revealed that the human proteome is larger than previously appreciated. Short open reading frames (sORFs), which are difficult to identify using traditional gene-finding algorithms, constitute a significant fraction of unknown protein-coding genes. Thus, experimental approaches to identify sORFs provide invaluable insight into the protein-coding potential of genomes. Here, we report an affinity-based approach to enrich and identify cysteine-containing human sORF-encoded polypeptides (ccSEPs) from cells. This approach revealed sixteen novel ccSEPs, each derived from an uncharacterized sORF, demonstrating its potential for discovering new genes. We validated expression of a SEP from its endogenous RNA, and demonstrated the specificity of our labeling approach using synthetic SEP. The discovery of additional human SEPs and their conservation indicate the potential importance of these molecules in biology.

Short open reading frame (sORFs)–encoded polypeptides (SEPs) are an emerging class of biomolecules that are comprised of peptides and small proteins from sORFs (defined here as < 150 codons)1. The existence of these molecules is of interest because they appear to be present in a variety of different cells1,2 and organisms3,4 but are missed by traditional gene finding algorithms5. The discovery of these molecules has already revealed a great deal about protein translation in cells1,2,6,7. Ribosome profiling2 and mass spectrometry discovery of sORFs1,2,7, for example, revealed the prevalent use of non-ATG start codons.

Genetic screens have also identified several bioactive protein-producing sORFs4. The search for genes that prevent cell death, for instance, led to the discovery of a 75-bp sORF that inhibits apoptosis of neuronal cells. It was shown that this sORF produces a 24-amino acid peptide4 called humanin that binds and inhibits BAX8, revealing a new endogenous molecule with a role in cell death. The complete extent of SEPs in the human genome is unknown and therefore there may be additional bioactive peptides and small proteins awaiting discovery.

SEPs are difficult to predict with traditional gene annotation algorithms due to their small size3. Additionally, SEPs have been shown to violate several canonical rules of protein translation. They often initiate with non-ATG start codons and some have been shown to be bicistronic1,2. The recent discovery of this hidden proteome by ribosome profiling2 and mass spectrometry1 has generated intense interest towards identifying additional SEPs.

In order to identify additional SEPs, and also to discover SEPs that have properties similar to functional proteins, making them more likely to be functional, we applied a cysteine affinity enrichment approach to identify novel cysteine containing SEPs (ccSEPs). Reactive cysteines play a variety of critical roles in protein structure and function. In particular, cysteines are important catalytic residues in the active site of many enzymes9. Furthermore, cysteine oxidation to sulfenic, solfinic, and sulfonic acid in addition to S-nitrosylation are important post translational modifications10. For example, S-nitrosylation on histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) was found to induce chromatin remodeling in neurons11. Lastly, cysteines are important metal chelators and are found in the metal binding site of many metalloproteins. The incorporation of metal ions in metalloproteins is important for metalloprotein folding and also stabilizes metalloprotein secondary structure12-14. The ability of metal binding cysteines to stabilize the secondary structure of proteins is particularly interesting in the case of SEPs. Short proteins are intrinsically more disordered so SEPs that contain metal binding cysteines are more likely to be structured and consequently more likely to be functional15,16. In addition to selecting for cysteines that may be amenable to further functional characterization, by using a different strategy to enrich the peptidome we anticipate the discovery of novel ccSEPs.

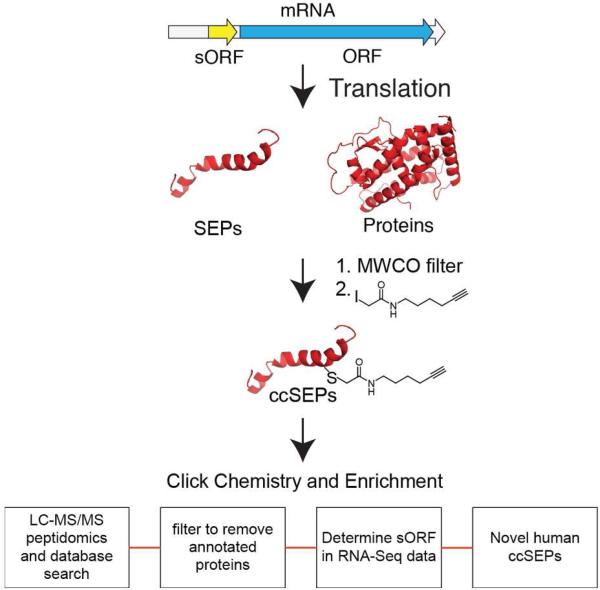

Our strategy began with isolating the peptidome from K-562 cells, a human leukemia cell line, by lysis of these cells followed by a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) filter to remove proteins larger than 30 kDa (Figure 1 and S1)1. We incubated the peptidome with a previously described iodoacetamide-alkyne (IA-alkyne) probe17,18 that reacts with the sulfhydryl side chain of cysteine to form a covalent bond to the peptide. Notably, when used at 100 μM concentrations the IA-alkyne probe will only label reactive cysteines18. After cysteine capture by IA-alkyne, the probe is conjugated to a biotin-labeled tobacco etch virus (TEV) recognition peptide through copper-activated click chemistry (CuACC)17-19. Probe-labeled peptides are then separated from unlabeled peptides via streptavidin affinity chromatography to afford an enriched peptidome sample. On-bead trypsin digestion was performed, and unlabeled peptides were eluted and analyzed by offline Electrostatic hydrophilic Repulsion LIquid Chromatography (ERLIC) fractionation followed by LC-MS/MS1,20. The remaining bead-bound labeled peptides were subsequently released from the beads by the addition of TEV protease, and were then analyzed by MudPIT-LC-MS/MS21.

Figure 1. Workflow for identifying cysteine-containing SEPs (ccSEPs).

The proteome and peptidome are separated by a MWCO filter and the peptidome fraction is carried forward to identify ccSEPs. Incubation of the peptidome with an iodoacetamide-alkyne (IA) probe leads to alkylation of cysteine-containing peptides including ccSEPs. Labeled peptides were then selectively enriched by conjugation to an azide-TEV-biotin tag using copper-activated click chemistry (CuACC) followed by affinity chromatography with streptavidin-coated beads. This sample is then analyzed by LC-MS/MS peptidomics and filtered to remove annotated proteins, which led to the identification of novel protein-generating sORFs that produce ccSEPs.

The data from this peptidomics analysis contains known as well as novel (i.e. non-annotated) peptides, including ccSEPs. In order to identify peptides originating from non-annotated RNAs, we used a custom database using K-562 RNA-Seq data1,22, which contains information on the vast majority of mRNAs in K-562 cells. Since these RNAs must be the source of any polypeptide produced we can include non-annotated genes in our peptidomics search by translating this database in three frames to generate a protein database that contains all possible peptide products.

We then matched our peptide spectra against this RNA-Seq database to reveal candidate SEPs. This approach yielded 175 hits that surpassed our preliminary cross correlation score requirements17. After removing annotated peptides we were left with 109 candidate SEPs. Our K-562 RNA-Seq database was too large to perform a reverse database search directly. To overcome this, we constructed a forward and reversed database by appending our candidate SEPs to the Uniprot database. We used this database to filter our candidate SEP spectra using a reversed database search, and only accepted peptides with a false discovery rate < 0.05. Subsequently, we validated that detected peptides could only originate from a single sORF (i.e. there are not two different ORFs in the RNA-Seq data that could account for the peptide). Additionally, SEPs with more than 2 missed cleavages were removed along with SEPs detected from peptides fewer than 7 amino acids in length. Furthermore spectra were visually inspected to ensure good sequence coverage and confirm that peptides detected from the TEV fraction contained an IA-modified cysteine residue (Figure S2). After this, we were left with 16 novel human ccSEPs (Table 1 and S1), with the majority having less than 6-ppm mass error (Table S2).

Table 1.

newly discovered ccSEPs

| Detected Peptidea | Start codon | Length (aa) | transcript origin | conserved? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C*GFFSYCSSESVSCSTS | ATC | 34 | non annotated | no |

| STSLYCHSTILC* | AAG | 24 | CDS | no |

| TC*DGNSNEGGGTR | AAG | 19 | non annotated | no |

| NFPLASSPERC*FFVPK | AAG | 48 | 3' UTR | yes |

| VEKLELLYIAGGNVNWYSPC* | GTG | 22 | non annotated | yes |

| YPAC*SPSPALI | CTG | 29 | non annotated | no |

| GRGCC*RGFSAVGQGPSST | ATG | 84 | non annotated | no |

| CPSINFQHFCHFVLCAFPIHC* | CTG | 35 | non annotated | no |

| TC*TIPVPAGGRPR | CTG | 32 | non annotated | no |

| IC*DIKGLIDNV | TTG | 41 | non annotated | no |

| TSPADAVC*PGLGRDLCGSSRCCLRP | ATG | 79 | 5' UTR | yes |

| RGPGEAGMSWEEAGGLAPHLLC*CR | GTG | 86 | CDS | yes |

| QIVLGGC*GEMV | alternate | 16 | non annotated | no |

| GASFSEDGC*LLVG | CTG | 37 | non annotated | no |

| GSSDIISVPC* | ATG | 40 | 3'UTR | yes |

| SSMPLIC*FLILEGLGR | ATG | 29 | 3' UTR | yes |

asterisk denotes labeled cysteine

In cases where a detected peptide contained multiple cysteines, the labeled cysteine could be determined from the MS/MS data (Figure 2A). To verify that our labeling and enrichment is specific to the cysteine on a ccSEPs, we performed an in vitro assay in cell lysates. We first synthesized TCT-SEP (named for the detected peptide; Figure 2B) by solid phase peptide synthesis, along with a mutant of this TCT-SEP where the cysteine is replaced by a serine, TST-SEP. We incubated TCT-SEP in K-562 cell lysates and then added the IA-alkyne probe. After labeling, the lysate was mixed with a fluorescent azide in the presence of copper (II) sulfate and TCEP to promote CuACC. This fluorescently labeled lysate was then resolved on an SDS page gel to assess labeling of the TCT-SEP. Labeling of TCT-SEP was specific and robust and could be easily observed within total K-562 lysate (Figure 2B). The control TST-SEP was not labeled when probe-treated alone or in K-562 lysate demonstrating that labeling is occurring on the cysteine residue (Figure S3).

Figure 2. Validation of site of labeling and cellular expression of newly discovered ccSEPs.

(A) In the case of ccSEPs with multiple cysteines, examination of the tandem MS spectra reveals the site of labeling. In this case, STS-ccSEP labels at the C terminal cysteine. Red indicates fragments detected by y ions, blue indicates fragments detected by b ions, and purple indicates fragments detected by both. (B) We tested labeling of one of the ccSEPs in a complex mixture by spiking the purified ccSEP into lysate and then performing a labeling reaction with rhodamine azide. If the ccSEP reacted it would fluorescently labeled. Mutation of the cysteine on the ccSEP to a serine abrogates labeling. (C) A C-terminal Flag tag appended to the sORF coding for TSP-ccSEP validated that this sORF does indeed produce protein. Staining of the protein product with an anti-Flag antibody confirmed expression and cellular stability of the ccSEP.

To validate the production of ccSEPs from their endogenous RNA, we transfected cells with a vector containing the sORF TSP-ccSEP, which is found on the same transcript as MRS2L. This construct contained the entire endogenous 5’UTR, which includes the sORF, and a FLAG tag was appended to the sORF to enable easy detection of protein production (Figure 2C and S4). Stable ccSEP expression was then observed by immunofluorescence using an anti-FLAG antibody (green) (Figure 2C and S5) and western blot (Figure S6). This sORF was not annotated previously, thereby highlighting the ability of this workflow to discover novel protein-coding genes. More generally, this affinity strategy successfully identified a new pool of SEPs with characteristic hallmarks of this emerging class of peptides1.

An overview of these newly identified ccSEPs revealed many similarities with previously identified SEPs. First, the length of their sORFs ranged between 16 and 86 codons (Figure 3A). SEP length was determined by measuring the number of codons between the stop codon of the sORF and the first start codon on the 5’ side of this stop codon. In the case where a start codon couldn’t be identified, the number of codons reflects the distance between the stop codon of the sORF and the 5’ end of the transcript. Second, these SEPs had both AUG start codons or non-canonical near cognate start codons (Figure 3B), similar to previously discovered SEPs. Moreover, SEPs could be found in the 3’UTR, frameshifted within known genes or within the 5’ UTR, in non-annotated RNAs, or in antisense transcripts (Supporting Information). As expected, we did not detect any previously observed SEPs, since our workflow was optimized towards the detection of SEPs with reactive cysteines. These identified SEPs are very small relative to the average length of a human protein, which is 335 amino acids23. The small size of these SEPs contributes to the difficulties associated with computationally predicting the sORFs that encode them.

Figure 3. ccSEP overview.

(A) Distribution of ccSEPs by their length in amino acids. SEP length was determined using the distance from an upstream in frame AUG start codon to a downstream in frame stop codon, or, when no inframe AUG was present, a near cognate start codon or stop codon was used instead. (B) While AUG is the predominant start codon for the production of ccSEPs, near cognate start codons (i.e. one base different from AUG) are also common. (C) TSP-SEP is strongly conserved amongst several species of primates suggesting this SEP may be functional.

While specific functions for these ccSEPs await future studies, we examined these ccSEPs for sequence conservation, which is an important and well-documented signifier of biological function24. We examined the conservation of our SEPs in several species by alignment of the translated RNA to in silico translated RNA and DNA databases comprising the GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, PDB, and Refseq sequences. Of the ccSEPs we discovered, over one third (6/16) are conserved amongst several species of primates indicating that they have been maintained throughout evolution and highlighting these ccSEPs as likely having functions. Notably, the cysteine residue that we find labeled by the IA probe is also conserved between species, including mice, despite the low overall sequence conservation across the entire SEP. This implies that this residue may be important for the SEP’s biological function (Figure 3C and S7). The conservation of these SEPs makes them good leads for further functional characterization, and demonstrates that this platform allows for the identification of peptides that are of significant biological interest.

In summary, we have utilized a chemoproteomics approach to identify new human ccSEPs. These results demonstrate the value of chemoproteomics to promote the discovery of additional sORFs. In this case, we identified 16 novel ccSEPs indicating the presence of even more of these molecules than had been predicted, and representing a 15% increase in the number of known SEPs. Moreover, conservation indicates that some of these ccSEPs may be functional. Furthermore, cysteine reactivity is governed by secondary structure and local environment, suggesting that enriching ccSEPs with highly reactive cysteines may identify proteins with distinct secondary structures. Additionally, certain biologically important post translational modifications, such as protein S-nitrosylation, occur at, and can be regulated by, redox active cysteines25. Some of these ccSEPs are likely targeted by these oxidative modifications, which could serve to further regulate SEP function. The struggle to identify the whole range of SEPs in human cells as well as their functional role remains a key question in biology. The development of mass spectrometry methods focused on the identification of SEPs, such as chemoproteomic approaches, is a critical step towards answering these questions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Xian Adiconis and Lin Fan for constructing the cDNA libraries used in this study. S.A.S. is supported by an NRSA postdoctoral fellowship (1F32GM099408-01). This work was supported by a Eli Lilly graduate fellowship (A.G.S), an NIH grant R01GM102491 (A.S.), an US National Human Genome Research Institute grant HG03067 (J.Z.L), the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation grant DRR-18-12 (EW) and the Smith Family Foundation (EW).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Slavoff SA, Mitchell AJ, Schwaid AG, Cabili M, Ma J, Levin JZ, Budnik B, Rinn JLS. A Nature Chemical Biology. 2012;9:59. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Cell. 2011;147:789. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galindo IG, Pueyo JI, Fouix S, Bishop SA, Couso JP. PLOS Biology. 2007;5:1052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Tajima H, Yasukawa T, Sudo H, Ito Y, Kita Y, Kawasumi M, Kouyama K, Doyu M, Sobue G, Koide T, Tsuji S, Lang J, Kurokawa K, Nishimoto I. PNAS. 2001;98:6336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101133498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frith MC, Forrest AR, Nourbakhsh E, Pang KC, Kai C, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Bailey TL, Grimmond SM. Proteins. 2006:2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Liu B, Lee S, Huang S, Shen B, Qian S. PNAS. 2012:109. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern-ginossar NW,B, Michalski A, Le VTK, Hein MY, Huang S, Ma M, Shen B, Qian S, Hengel H, Mann M, Ingolia NTW,JS. Science. 2013;338:1088. doi: 10.1126/science.1227919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo B, Zhai D, Cabezas E, Welsh K, Nouraini S, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Nature. 2003;423:456. doi: 10.1038/nature01627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman HA, Riese RJ, Shi G-P. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1997;59:63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddie KG, Carroll KS. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2008;12:746. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nott A, Nitarska J, Veenvliet JV, Schacke S, Derijck AAHA, Sirko P, Muchardt C, Pasterkamp RJ, Smidt MP, Riccio A. PNAS. 2013;110:3113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218126110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeguchi M, Kuwajima K, Sugai SJ. Biochem. 1986;99:1191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne HJ, III, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Banci L, Bertini I, Zhang L, George GN, Winge DR. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:8926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morleo A, Bonomi F, Iamentti S, Huang VW, Kurtz D., Jr Biochemistry. 2010;49:6627. doi: 10.1021/bi100630t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholtz JM, Baldwin RL. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1992;21:95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozlowski H, Bal W, Dyba M, Kowalik-Jankowska T. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 1999;184:319. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weerapana E, Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:1414. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weerapana E, Wang C, Simon G, Richter F, Khare S, Dillon MBD, Bachovchin DA, Mowen K, Baker D, Cravatt BF. Nature. 2010;468:790. doi: 10.1038/nature09472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu PF,AK, Nugent AK, Hawker CJ, Scheel A, Voit B, Pyun J, Fréchet JMJ, Sharpless BK, Fokin VV. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3928. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alpert A. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:62. doi: 10.1021/ac070997p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Washburn M, Wolters D, Yates J. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19:242. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, World B. Nature Methods. 2008;5:621. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, Otsuki T, Sugiyama T, Irie R, Wakamatsu A, Hayashi K, Sato H, Nagai K. Nature Genetics. 2004;36:40. doi: 10.1038/ng1285. al., e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponjavic J, Ponting C, Lunter G. Genome Research. 2007;17:556. doi: 10.1101/gr.6036807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim S, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Nature Reviews Molecullar Cell Biology. 2005;6:150. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.