Abstract

Background

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) may play a critical role in alcohol reinforcement and consumption. The effects of varenicline, a nAChR partial agonist, on alcohol seeking and self-administration responses were evaluated in 2 groups of baboons trained under a 3-component chained schedule of reinforcement (CSR).

Methods

Alcohol (4% w/v; n=4; alcohol group) or a preferred non-alcoholic beverage (n=4; control group) was available for self-administration only in component 3 of the CSR. Responses in component 2, required to gain access to alcohol, provided indices of seeking behavior. Varenicline (0.032 – 0.32 mg/kg; 0.32 mg/kg BID) and vehicle were administered before CSR sessions subchronically (5 consecutive days). Higher doses (0.56, 1.0 mg/kg) were attempted but discontinued due to adverse effects.

Results

Subchronic varenicline administration significantly (p<0.05) decreased the seeking response rate and increased the time to complete the response requirement to gain access to the daily supply of alcohol at the higher doses (0.32 mg/kg, 0.32 mg/kg BID dosing) in the alcohol group compared to the control group. Mean number of drinks was significantly decreased (p<0.05), but effects did not differ between groups. The pattern of drinking was characterized by a high rate during an initial bout. Number of drinks during and duration of the initial bout were significantly decreased in the alcohol group, compared to the control group, at 0.32 mg/kg (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Varenicline may be clinically useful for reducing alcohol seeking behaviors prior to alcohol exposure. Given the modest effects on drinking itself, varenicline may be better suited as a treatment in combination with a pharmacotherapy that significantly reduces alcohol consumption.

Keywords: Craving, cues, drinking, ethanol, self-administration

Introduction

There are currently three Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications for the treatment of alcohol dependence, the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone (oral and depot formulations), the aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor disulfiram, and acamprosate, which appears to modulate gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate neurotransmission (Litten et al. 2012). Although these medications have demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials, effect sizes are generally modest and the majority of patients relapse to heavy drinking. Given the chronically relapsing nature of alcoholism and the limitations of the currently available medications, identification and development of new treatment medications is clearly needed.

Varenicline (Chantix®) was originally developed for use as a smoking cessation agent and is currently FDA-approved for this purpose (Cahill et al., 2012). Varenicline functions as a partial agonist at the α4β2, α3β2 and α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) subtypes, and a full agonist at α3β4 and α7 nAChR subtypes (Coe et al., 2005; Rollema et al., 2009). The strong association between heavy alcohol drinking and tobacco use (Chatterjee and Bartlett, 2010) has lead to a growing interest in the use of varenicline for the treatment of alcohol dependence. In smokers who were also heavy drinkers, varenicline (2 mg/day) reduced alcohol craving and the number of heavy drinking days in preliminary placebo-controlled clinical trials (Fucito et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2012). Varenicline also reduced craving and the positive subjective effects of alcohol in human laboratory studies (McKee et al., 2009; Childs et al., 2012).

To date, the majority of preclinical varenicline studies have primarily focused on alcohol consumption using 2-bottle choice procedures, where solutions of alcohol or water are freely available, in rodents. Using these procedures, varenicline decreased alcohol consumption in rats chronically exposed to alcohol for 2 months before varenicline treatment (Steensland et al., 2007). In C57BL/6J mice, an inbred mouse strain that shows high alcohol intake and preference (Belknap et al., 1993), varenicline selectively decreased ethanol consumption in a 2-bottle procedure and at doses that did not affect saccharin or water consumption (Kamens et al., 2010). Recent studies using knock-out and knock-in technology in C57BL/6J mice and the 2-bottle choice procedure found that the α4 subunit modulates varenicline effects on alcohol intake (Hendrickson et al., 2010), whereas the β2 or α7 subtypes do not (Kamens et al., 2010). While these studies provide evidence that varenicline reduces alcohol consumption, per se, they do not provide information about whether varenicline specifically alters self-administration responding maintained by alcohol reinforcement or how it affects the pattern of drinking.

The nAChRs have been shown to mediate release of dopamine (DA) in the mesolimbic system and, as a result, it has been suggested that they may play an important role in alcohol reinforcement (for a review see Söderpalm et al., 2000). The finding that varenicline reduces alcohol-induced dopamine release is consistent with this hypothesis (Ericson et al., 2009). Only a few studies in rats have evaluated pretreatment with varenicline on responding maintained by alcohol as a reinforcer using operant alcohol self-administration procedures. In these studies, varenicline significantly decreased operant self-administration of alcohol (Steensland et al., 2007; Bito-Onon et al., 2011) and attenuated cue-induced reinstatement of extinguished operant responses previously maintained by alcohol (Wouda et al., 2011). The effects of varenicline on non-drug reinforcement are not clear. One study found no effect of varenicline on operant responding for sucrose (Steensland et al., 2007), and a second study reported varenicline increased sucrose responding (Wouda et al., 2011). When a non-drug reinforcer (food) was available concurrently, low doses of varenicline increased self-administration for alcohol but not food while high doses disrupted responding for both (Ginsburg and Lamb, 2013).

Although the recent rodent studies suggest that varenicline may be effective for reducing alcohol consumption and self-administration, important questions relevant to its potential effectiveness as a therapeutic remain. Of high clinical significance is the question of whether varenicline reduces behavior directed towards obtaining access to alcohol (e.g., seeking) and, if changes do occur, whether they are accompanied by reductions and/or changes in pattern of drinking. The current study examined the effects of varenicline on alcohol seeking, as well as self-administration, in large nonhuman primates (baboons) under a chained schedule of reinforcement (CSR) (Weerts et al., 2006; Kaminski et al., 2008). The CSR provides an extended sequence of behavior to model key features of anticipation, seeking, and compulsive drinking associated with alcohol use disorders. The CSR includes a sequence of distinct stimuli (lights and tones) each correlated with behavioral contingencies (i.e., reinforcement schedule requirements) that must be completed in order to gain access to the daily supply of alcohol. Alcohol is only available for self-administration in the last component of the CSR. Thus, alcohol-seeking responses in the earlier components of the CSR provide a quantitative measure of seeking that does not involve extinction procedures, and can be separated from alcohol self-administration responses. Further, by retaining a self-administration component (unlike the 2-bottle choice procedures described above), the CSR allows evaluation of alcohol reinforcement, response rates, and patterns of drinking.

The patterns of alcohol consumption, and blood alcohol levels achieved (>0.08%, Kaminski et al., 2008) in the CSR procedure model the “drinking too much, too fast, and too often” pattern of “at risk” drinking defined by The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Further, these baboons maintain these levels 7 days/week and have been doing so for 7 years (Weerts et al., 2006; Kaminski et al., 2008), modeling long-term use characteristics of heavy drinking and abuse in humans and satisfying the recommended level of volitional alcohol intake for medications development (Grant and Bennett, 2003; Egli, 2005). Drinking in this model, then, allows clear detection of changes in behavior and alcohol intake while modeling, under controlled laboratory conditions, key characteristics of human “at risk” heavy drinking. In order to determine the specificity of effects on alcohol-related behaviors, varenicline was also administered to our matched control group of baboons that share a similar CSR self-administration history with a preferred, non-alcoholic beverage.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Eight singly-housed adult male baboons (Papio anubis; Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, TX) weighing 28.3 kg (+ 5.7 SD) served as subjects. Baboons were housed under conditions previously described (Kaminski et al., 2012). For the alcohol group (N=4), the reinforcer delivered was 4% alcohol w/v. For the control group (N=4), the reinforcer delivered was a preferred non-alcohol beverage (orange-flavored Tang®), diluted to a concentration that maintained breaking points comparable to those maintained by alcohol under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement (Duke et al., 2012). All baboons had extensive histories of self-administration of the reinforcer under the CSR. Baboons were not food deprived and received standard primate chow (50-73 kcals/kg), fresh fruit or vegetables, and a children's chewable multivitamin daily. Drinking water was available ad libitum except during sessions. Facilities were maintained in accordance with US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) standards. The protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996).

Apparatus

Each baboon's cage also functioned as the experimental chamber (for details, see Weerts et al., 2006) and contained a panel with three colored “cue” lights, an intelligence panel with 2 vertically operated levers with a different colored “jewel” lights mounted above each lever and a “drinkometer” (connected to a calibrated 1000-ml bottle), and a speaker mounted above the cage. A computer interfaced with Med Associates hardware and software remotely controlled the experimental conditions and data collection.

Drugs

All solutions for oral consumption were mixed using reverse osmosis (RO) purified drinking water. Ethyl alcohol (190 Proof, Pharmco-AAPER, Brookville CT) was diluted with RO water to 4% w/v alcohol. Orange-flavored Tang® powder (Kraft Foods) was dissolved in RO water following package instructions and then diluted from full strength to concentrations of 25-50% as described previously (Kaminski et al. 2012). Varenicline dihydrochloride (NIDA Research Resources Drug Supply Program; 0.032-1.0 mg/kg) was dissolved in 2 ml of saline and administered via subcutaneous (SC) injection. Vehicle (VEH) tests were completed using the same volume and procedures. While baboons will drink high concentrations of alcohol (e.g., 16% w/v) during induction of alcohol drinking (Henningfield et al., 1981), we selected the 4% w/v concentration based on our prior studies showing 1) this concentration is preferred by the majority of baboons tested in alcohol vs. water choice procedures (Ator and Griffiths, 1992), and 2) it maintains high stable rates of self-administration under the CSR (Kaminski et al., 2008, 2012; Weerts et al., 2006).

Chained Schedule of Reinforcement (CSR) Procedure

During all sessions, fluids were available only via the drinkometer. The CSR procedures have been described in detail previously (Weerts et al., 2006, Kaminski et al., 2008) and were identical for the alcohol and control groups. Daily sessions (7 d/week for both groups) were initiated at the same time (8:30 AM) and were signaled by a 3-s tone. During component 1, a red cue light was illuminated for 20 min and all instrumental responses were recorded but had no consequence. Component 2 was signaled by illumination of a yellow cue light and was composed of two links; each associated with a different operant schedule and distinguished by the status of a yellow jewel light over the left lever. During the first link of component 2, the yellow jewel light over the left lever was continuously illuminated and transition to the second link occurred after either (1) the completion of a fixed-interval (FI) 10 min schedule or (2) after 20 min if no response occurred. In the second link, the yellow jewel light over the lever flashed and a fixed-ratio (FR 10) schedule was in effect on the left lever for transition to component 3. If the FR 10 requirement was not completed within 10 min, the session terminated without transitioning to component 3 (i.e., no access to alcohol or the non-alcoholic beverage for the day). During component 3, a blue cue light and a blue jewel light over the right lever were illuminated, and “drinks” of alcohol or the non-alcoholic beverage were available under an FR 10 (FR 5 for baboon WI) schedule on the right lever followed by contact with the drinkometer spout. Fluid was delivered for the duration of spout contact or for a programmed duration (5 s), whichever came first. Thus, use of the term ‘drink’ for the current paper is operationally defined as each contact with the drinkometer spout resulting in fluid delivery. Component 3 (and the session) ended after 120 min.

Varenicline Test Procedures

Stable baseline (BL) CSR self-administration was based on component 3 responding only and was defined as criterion was defined as self-administration responding (FR lever responses/number of drinks obtained) within ± 20% for three consecutive CSR sessions. Doses of varenicline (0.032-1.0 mg/kg, SC) or VEH were administered subchronically. Each dose was administered 30 min before CSR sessions according to a standard sub-chronic dosing regimen (5 consecutive days) to baboons in both groups. The CSR was re-established and CSR BL criterion was met before each test dose of varenicline or VEH. Doses were tested in randomized mixed order. Stable BL intake was sometimes disrupted after drug treatments and required additional time to stabilize before testing the next dose (e.g., 2 weeks). Administration of 0.56 and 1.0 mg/kg resulted in complete suppression of responding, vomiting, and food suppression and, therefore, evaluation of these doses was terminated after 1-3 days of dosing and the data are not included in the analyses. Because evaluation of a high dose was of interest, the 0.32 mg/kg dose was administered twice daily (BID), resulting in 0.64 mg/kg delivered over a 24-h period.

Blood Alcohol Analysis Procedures

Immediately following an alcohol self-administration session, baboons were anesthetized with ketamine and 5-ml blood samples were collected from a saphenous vein. Double determinations of blood analysis level (BAL) were completed using a rapid high performance plasma alcohol analysis using alcohol oxidase with AMI analyzer (Analox Instruments USA, Lenenberg, MA) with Analox Kit GMRD-113 (detects ranges from 0 to 350 mg/dl, using internal standard of 100 mg/dl). This assay has previously been used in our laboratory to determine BALs in baboons (Kaminski et al., 2008).

Data Analysis

Initial analysis revealed that rate of drinking differed substantially between the two groups (see Results below). To facilitate comparisons between groups, for each measure, for each baboon the mean of the 5 days of each varenicline dose was converted to the percentage of the grand BL mean (the mean of all 3-day BL periods immediately preceding a dose evaluation for that baboon) prior to analysis. Individual subject data of non-transformed data are available as supplemental figures online (Figs S1 – S3). Data were analyzed using statistical two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Group (Alcohol or Control) and Dose (0-0.32, and 0.32 BID) as factors. Post hoc Bonferroni's t-tests were used for comparisons between groups at each dose, and p < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Total g/kg of alcohol was calculated based on individual body weights and total volume of alcohol consumed. Change in g/kg of alcohol consumed was calculated as test dose – BL; doses of varenicline were compared to VEH for analysis. The data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with varenicline dose (0-0.32, and 0.32 BID mg/kg) as a repeated measure.

Patterning of drinking was analyzed as a function of drinking “bouts.” A drinking bout was operationally defined by Grant and colleagues (Grant, personal communication 2012; Grant et al., 2008) as two or more drinks with less than 5 min between each drink, beginning with the first drink. The number of drinks and duration (s) of bouts, and median inter-drink interval as a function of varenicline dose were converted to percent of grand BL and analyzed using two-way ANOVA as described above, with post-hoc Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons, as appropriate. A p of 0.05 < accepted as significant.

Results

During the criterion BL CSR sessions, stable, reliable drinking was observed in all baboons, in both groups. Both alcohol and the non-alcoholic beverage maintained self-administration responses (right lever responses; drink contacts) and high intake (ml). The volume of each drink, within the constraints described above, was under the control of the baboon. The average amount of alcohol consumed per drink (total volume consumed/number of drinks in the session) was approximately 30 ml and did not vary systematically as a function of varenicline administration (data not shown). Few or no responses were recorded on the inactive operanda (all operanda in component 1, right lever and drinkometer in component 2, left lever in component 3) during BL sessions.

To determine if there were any differences in BL responding in the alcohol and control groups, responding was compared for the two groups. There were no differences between the groups for early components of the chained schedule associated with seeking (component 1 and 2 measures). As in previous studies, the non-alcoholic reinforcer maintained higher intake volumes than alcohol (t-test, t(6)=7.34, p<0.001). The grand mean (+ SEM) non-alcoholic beverage intake during BL sessions was 992.1.0 (+15.9) ml. Under BL conditions, the grand mean alcohol intake was 627.6 (+93.0) ml and 1.05 (+0.20) g/kg. During blood sampling sessions, the mean alcohol intake was 1.30 g/kg (range 1.06 g/kg to 1.4 g/kg), which produced a mean BAL of 105.51 mg/dl (range 77.4 mg/dl to 126.8 mg/dl).

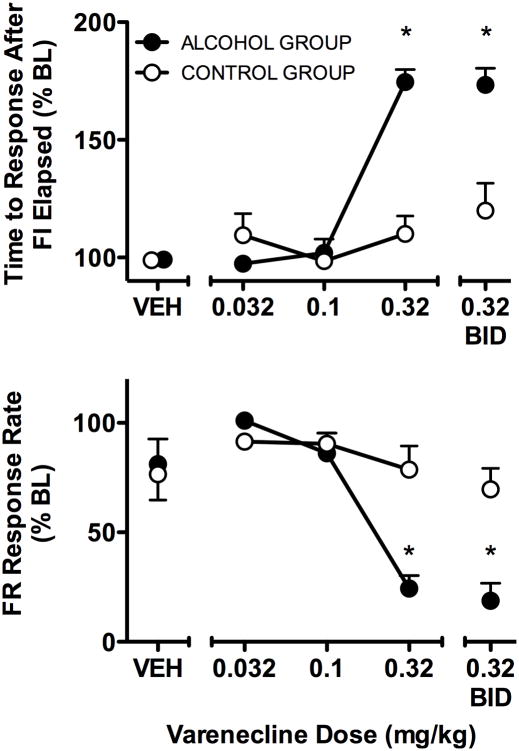

Varenicline administration produced significant changes in component 2 seeking measures (Fig 1). There was a significant interaction between group and dose (F = 16.74, df = 1,6, p < 0.005) in the time to the response after the FI elapsed, indicating that the effects of varenicline differed between groups significantly at 0.32 mg/kg and 0.32 mg/kg BID (both p<0.05) (Fig 1, top panel). The percentage of sessions in which the FI requirement was not completed was 60% in the alcohol group and 8% in the control group at 0.32 mg/kg, and 70% in the alcohol group and 15% for the control group at 0.32 mg/kg BID. In those cases, the time to the “response” after the FI requirement elapsed was the maximum duration (600 s) before the transition to link 2. In contrast, both groups of baboons always completed the FI 10-min schedule under BL. The subsequent link 2 requirement (and transition to component 3) was completed on all but one occasion in each of group. A significant interaction (F = 8.97, df = 1,6, p < 0.001) was obtained for rate of responding under the component 2, link 2 FR schedule. In particular, response rate was decreased more in the alcohol group than the control group at 0.32 mg/kg and 0.32 mg/kg BID (both p<0.05) (Fig 1, bottom panel).

Fig 1.

The effects of varenicline on seeking measures for alcohol or a nonalcoholic reinforcer in component 2 of the CSR in the alcohol group (n=4; filled circles) and the control group (n = 4; unfilled circles). Data shown are the percent of the BL grand mean (SEM) of the five days of varenicline administration for each dose and VEH. 2-way ANOVA confirmed significant effects (p < 0.05) of Dose and Group, as well as a significant interaction of the two factors, for the time to the response after the FI elapsed (i.e., the response that completed the FI requirement) and FR response rate. * indicates p<0.05 for Bonferroni comparison of alcohol versus control group at the indicated doses.

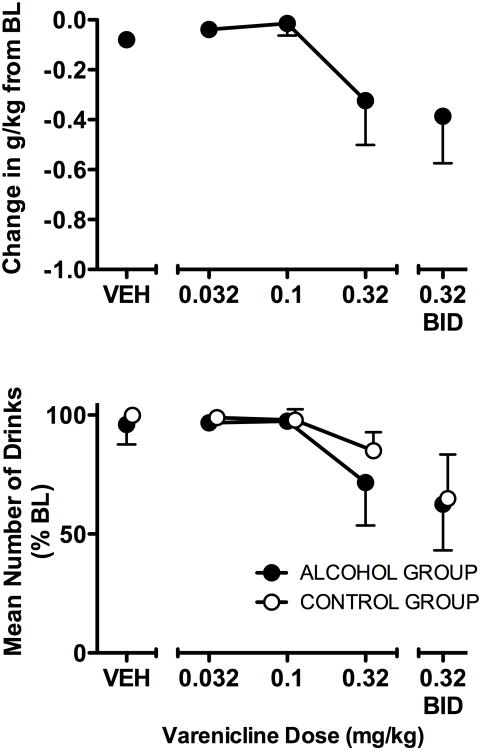

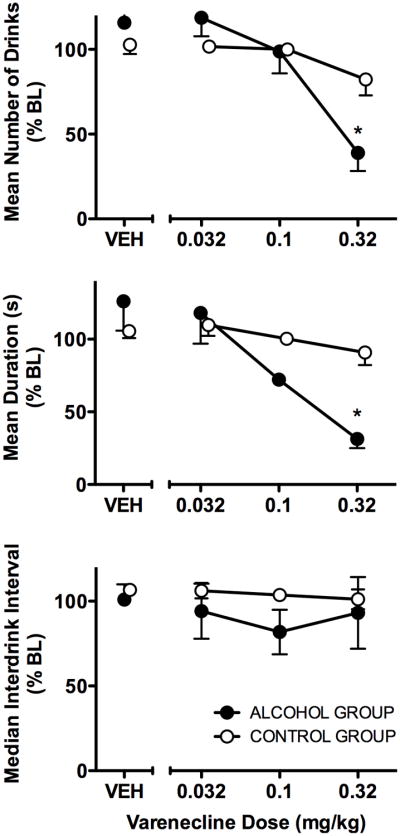

As shown in Fig 2, varenicline dose-dependently decreased alcohol intake (g/kg) from BL (F = 4.80, df = 4,12, p < 0.02). However, varenicline also dose-dependently decreased the number of drinks obtained regardless of group (F = 4.41, df = 4,24, p < 0.01). Analysis of drinking patterns showed that for both groups, during BL and VEH sessions, the majority of drinks occurred during the first bout and the pattern of drinks was rapid. In the alcohol group, during BL 59.5% of total drinks occurred during the first bout with a median inter-drink interval of 22.67 s and during VEH 69.8% of drinks occurred during the first bout with an inter-drink interval of 23.61 s. In the control group, during BL 97.1% of total drinks occurred during the first bout with a median inter-drink interval of 9.8 s and during VEH 98.5% of drinks occurred during the first bout with an inter-drink interval of 9.8 s. Characteristics of the first bout were analyzed as a function of varenicline dose for both groups. Sessions during which either there were no drinks or drinking was initiated but only one drink occurred before the first > 5 min break did not satisfy the criterion for a bout (two or more drinks with less than 5 min between each drink) and were not included in analyses of measures of the first drinking bout. Due to the number of such sessions during 0.32 mg/kg BID dosing, data for this dose were not included in the bout analyses. Varenicline produced dose-related, significant changes in bout measures in the alcohol group but not the control group. There was a significant interaction between group and dose in the mean number of drinks in the first bout (F = 11.80, df = 3,18, p < 0.001), with varenicline decreasing the number of drinks at 0.32 mg/kg in the alcohol group, compared to the control group (p<0.05). Varenicline also decreased the duration of the first bout, with a significant interaction between group and dose (F = 11.95, df = 3,18, p < 0.001) that was characterized by a significant difference between the alcohol and control groups at the 0.32 mg/kg dose (p<0.05). For varenicline doses in which drinking bouts occurred (0.032-0.32), the median inter-drink interval not significantly altered by varenicline.

Fig. 2.

The effects of varenicline on self-administration in component 3 of the CSR in the alcohol group (n=4; filled circles) and the control group (n=4; unfilled circles). Data shown for change in g/kg of alcohol consumed are the mean of the five days of varenicline administration - mean BL g/kg. Data shown for mean number of drinks are the percent of the BL grand mean (SEM) of the five days of varenicline administration for each dose and VEH. 2-way ANOVA a confirmed significant main effect (p<0.05) of Dose for number of drinks.

Discussion

The high rate of nicotine and alcohol co-use (Gulliver et al.,1995) and the fact that both nicotine and alcohol activate nAChRs, which mediate release of DA in the mesolimbic system (Söderpalm et al., 2000), lead to the current theory that nAChRs may play a role in alcohol use and reinforcement. As a result, nAChRs have become a potential target for development of therapeutic agents to treat alcohol abuse and dependence. One of the primary obstacles to successful treatment is the persistence of urges to drink that can trigger relapse to heavy drinking. Cravings/urges to drink are thought to be due in part to conditioned (i.e., learned) states that prompt alcohol seeking. Thus, studies in laboratory animals that include independent measures of both seeking and self-administration can provide important information to increase our understanding of treatment effects on basic behavioral processes thought to be associated with alcohol use disorders. The current study provides new data showing that varenicline reduced alcohol seeking and altered the pattern of alcohol drinking in baboons with long-term heavy drinking experience.

The baboons in the current study had long-term experience with self-administration under the CSR with either alcohol or the non-alcoholic beverage. In the alcohol group, intake of approximately 1 g/kg/day has been maintained for 7 years. Our NHP model is an advance from typical self-administration models by modeling the ‘too much, too fast, too often’ drinking patterns associated with ‘at risk’ problem drinking as defined by NIAAA. This includes drinking to intoxication (e.g., 0.8 to 1 g/kg, BAL >0.08%) with a single 2-3 hr drinking period (i.e., a “binge”) and regular drinking at this level across days (“heavy drinking”). The level and pattern of frequent alcohol intake by baboons under the CSR meets this NIAAA definition. Previously we have shown alcohol self-administration in this group of baboons is highly resistant to change, and that baboons will complete high response ratios to obtain the daily supply of alcohol and defend high alcohol intake levels (Kaminski et al., 2008). Taken together with the long-term drinking history and exposure to alcohol-related cues in the drinking environment, the current study uniquely models aspects of human problem drinking under carefully controlled laboratory conditions, and without confounds common to human research.

In the current study, the strongest effect of varenicline was on “seeking” measures, i.e., behaviors that produced access to the opportunity to self-administer alcohol. In our nonhuman primate model, alcohol-seeking behavior has been highly resistant to change and has been maintained over prolonged periods (months) under conditions of daily alcohol access and of prolonged abstinence and extinction (Kaminski et al., 2008). It is noteworthy, then, that in the present study, varenicline increased the time to complete the FI response requirement and decreased the subsequent FR response rate. These changes in seeking cannot be attributed to general rate-decreasing effects of varenicline, as they were not also obtained in the control group. Further, because alcohol was not available until component 3, these decreases in seeking are also not the result of the combined pharmacological effects of varenicline and the alcohol consumed. One possible interpretation, consistent with previous research, is that varenicline changes the behavioral response to stimuli previously associated with alcohol availability. In a reinstatement model in rats, varenicline reduced cue-induced relapse to alcohol, but not nicotine (Wouda et al., 2011). Given that environmental or contextual stimuli associated with drug use are an important contributing factor in relapse to drug use (Childress et al., 1992; Collins and Brandon, 2002; Crombag and Shaham, 2002), decreases in stimulus-controlled seeking, reinstatement, and craving, would suggest that varenicline could be particularly useful for reducing cue-reactivity and alcohol seeking behaviors. Indeed, self-reported alcohol craving was attenuated in heavy-drinking smokers after 1 week (McKee et al., 2009) and 3 weeks (Fucito et al., 2011) of varenicline pretreatment.

A strength of the CSR is that it allows examination of whether any changes in seeking are accompanied by changes in the subsequent drinking. Analyses of drinking characteristics of the initial drinking bout provide some evidence that varenicline may decrease the reinforcing effectiveness of alcohol once alcohol consumption is initiated. In the CSR, the majority of drinking occurs within the first 20 min of alcohol availability (Duke et al., 2012; Kaminski et al., 2012). This is generally followed by a substantial (generally > 5 min) break in drinking and a low rate of drinking (either occasional “sipping” or several smaller bouts) over the remaining two hours. This within-day pattern, with an initial bout that is characterized by a high rate of drinking followed by a pause, is similar to what has been reported in both rhesus monkeys (Grant et al., 2008) and humans (Samson and Fromme, 1984; Spiga et al., 1997). In the present study, the rate of alcohol drinking, once initiated, was not significantly decreased. The number of drinks within and duration of the first bout, however, were significantly decreased as a function of varenicline dose. In a study of “smoking cessation,” in which drinking behaviors were specifically measured, Mitchell et al. (2012) reported that while varenicline did not decrease the number of drinking days, heavy-drinking smokers drank less once drinking was initiated.

One of the proposed behavioral mechanisms underpinning varenicline effects on alcohol self-administration is a decrease in the reinforcing efficacy of alcohol due to an increase in the aversive and/or sedating effects of alcohol. In C57BL/6J mice, varenicline increased ethanol-induced ataxia and decreased locomotor activity (Kamens et al., 2010). In human subjects, which to date have all been alcohol-drinking smokers, pretreatment with varenicline has produced increases in the sedating effects of alcohol (Fucito et al., 2011), decreases in alcohol positive subjective effects (McKee et al., 2009; Childs et al., 2012), and increases in ratings of dysphoria (Childs et al., 2012). In rats, high doses of varenicline (3.2 – 5.6 mg/kg) have been reported to disrupt responding for both alcohol and food (Ginsburg and Lamb, 2013). While the present procedure did not include a direct measure of aversive effects, in the present study 0.32 mg/kg when delivered BID, and to a lesser extent when delivered daily, produced increases in latency to initiate drinking and suppression of drinking in the first bout in both groups, suggesting that non-specific aversive effects cannot be ruled out.

Although alcohol self-administration (number of drinks) was significantly decreased as a function of varenicline administration, overall the effects of varenicline on g/kg alcohol consumption were modest. Baboons continued to consume about 0.7 g/kg alcohol at the highest doses of varenicline tolerated (0.32 mg/kg once daily and BID dosing). While this is a statistically significant decrease when compared to intakes of 1 g/kg, it is only a modest reduction in alcohol intake. Similarly, although statistically significant decreases have been reported in self-administration studies in rodents, the decreases were also relatively modest and substantial levels of self-administration responding and/or intake remained (Steensland et al., 2007; Wouda et al., 2011). Further, the decrease obtained in the present study is not an improvement when compared to the opiate antagonist naltrexone (Kaminski et al., 2012). In the study reported by Kaminski et al. (2012), the highest dose of naltrexone evaluated (0.32 mg/kg), when delivered under similar subchronic conditions, significantly decreased g/kg alcohol intake to 0.46 g/kg/session. The results of the present study showing that alcohol-seeking behaviors directed toward obtaining access to alcohol, which are highly resistant to change, were reduced significantly by varenicline suggest that it may be clinical useful for reducing craving and/or seeking behaviors prior to alcohol exposure. However, the small effect size on actual alcohol intake suggests it may not reduce drinking if a relapse occurs. Since naltrexone reduces intake during early drinking episodes to reduce full-fledged relapse into heavy drinking (O'Malley and Froehlich, 2003; Anton et al., 2006; Pettinati et al., 2006), varenicline may be better suited as a treatment in combination with naltrexone.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 3.

The effects of varenicline on the pattern of drinking in the first drinking bout in the alcohol group (n=4; filled circles) and control group (n=4; unfilled circles). Data shown are the percent of BL grand mean (SEM) of the number of drinks in the first bout, duration (s) of the first bout, and median inter-drink interval (s) during the first bout for each varenicline dose and VEH. 2-way ANOVA confirmed significant (p < 0.05) main effects of dose for mean number of drinks and mean duration. * indicates p<0.05 for Bonferonni comparison of alcohol versus control group at the indicated dose.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, NIAAA R01AA15971. The authors wish to thank the National Institute on Drug Addiction (NIDA) Research Resources Drug Supply Program for supplying the varenicline used for this research.

This research was supported by NIH/NIAAA R01AA15971 (Weerts).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- Ator NA, Griffiths RR. Oral self-administration of triazolam, diazepam, and ethanol in the baboon: drug reinforcement and benzodiazepine physical dependence. Psychopharmacol. 1992;108:301–312. doi: 10.1007/BF02245116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton R, O'Malley S, Ciraulo D, Cisler R, Couper D, Donovan D. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J, Crabbe J, Young E. Voluntary consumption of ethanol in 15 inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacol. 1993;112:503–510. doi: 10.1007/BF02244901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bito-Onon J, Simms J, Chatterjee S, Holgate J, Bartlett S. Varenicline, a partial agonist at neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, reduces nicotine-induced increases in 20% ethanol operant self-administration in Sprague-Dawley rats. Addict Biol. 2011;16:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill K, Stead L, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Bartlett S. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as pharmacotherapeutic targets for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:60–76. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress A, Ehrman R, Rohsenow D, Robbins S, O'Brien C. Classically conditioned factors in drug dependence. In: Lowinson P, Luiz P, Millman RB, Langard G, editors. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1992. pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Childs E, Roche D, King A, de Wit H. Varenicline potentiates alcohol-induced negative subjective responses and offsets impaired eye movements. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:906–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe J, Brooks P, Vetelino M, Wirtz M, Arnold E, Huang J, Sands S, Davis T, Lebel L, Fox C, Shrikhande A, Heym J, Schaeffer E, Rollema H, Lu Y, Mansbach R, Chambers L, Rovetti C, Schulz D, Tingley Fr, O'Neill B. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B, Brandon T. Effects of extinction context and retrieval cues on alcohol cue reactivity among nonalcoholic drinkers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag H, Shaham Y. Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:169–173. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AN, Kaminski BJ, Weerts E. Baclofen effects on alcohol seeking, self-administration and extinction of seeking responses in a within-session design in baboons. Addict Biol. 2012 Mar 28; doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00448.x. 2012 epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli M. Can experimental paradigms and animal models be used to discover clinically effective medications for alcoholism? Addict Biol. 2005;10:309–319. doi: 10.1080/13556210500314550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Lof E, Stomberg R, Soderpalm B. The smoking cessation medication varenicline attenuates alcohol and nicotine interactions in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system. J Pharm Exp Thera. 2009;329:225–230. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito L, Toll B, Wu R, Romano D, Tek E, O'Malley S. A preliminary investigation of varenicline for heavy drinking smokers. Psychopharmacol. 2011;215:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2160-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. Effects of varenicline on ethanol- and food-maintained responding in a concurrent access procedure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013 Feb 15; doi: 10.1111/acer.12085. 2013 epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant K, Leng X, Green H, Szeliga K, Rogers L, Gonzales S. Drinking Typography Established by Scheduled Induction Predicts Chronic Heavy Drinking in a Monkey Model of Ethanol Self-Administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1824–1838. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Bennett AJ. Advances in nonhuman primate alcohol abuse and alcoholism research. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;100:235–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver SB, Rohsenow DJ, Colby SM, Dey AN, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Monti PM. Interrelationship of smoking and alcohol dependence, use and urges to use. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:202–206. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson L, Zhao-Shea R, Pang X, Gardner P, Tapper A. Activation of alpha4* nAChRs is necessary and sufficient for varenicline-induced reduction of alcohol consumption. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10169–10176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningfield JE, Ator NA, Griffiths RR. Establishment and maintenance of oral ethanol self-administration in the baboon. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1981;7:113–124. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(81)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. Update on neuropharmacological treatment for alcoholism: scientific basis and clinical findings. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:34–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens H, Andersen J, Picciotto M. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline increases the ataxic and sedative-hypnotic effects of acute ethanol administration in C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:2053–2060. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski BJ, Duke AN, Weerts EM. Effects of naltrexone on alcohol drinking patterns and extinction of alcohol seeking in baboons. Psychopharmacology. 2012;223:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski BJ, Goodwin AK, Wand G, Weerts EM. Dissociation of alcohol-seeking and consumption under a chained schedule of oral alcohol reinforcement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1014–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Heilig M, Cunningham CL, Stephens DN, Duka T, O'Malley SS. Ethanol consumption: how should we measure it? Achieving consilience between human and animal phenotypes. Addict Biol. 2010;15:109–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten R, Egli M, Heilig M, Cui C, Fertig J, Ryan M, Falk D, Moss H, Huebner R, Noronha A. Medications development to treat alcohol dependence: a vision for the next decade. Addict Biol. 2012;17:513–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee S, Harrison E, O'Malley S, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault J, Picciotto M, Petrakis I, Estevez N, Balchunas E. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Harrison EL, Shi J. Alcohol expectancy increases positive responses to cigarettes in young, escalating smokers. Psychopharmacol. 2010;210:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1831-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J, Teague C, Kayser A, Bartlett S, Fields H. Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy-drinking smokers. Psychopharmacol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2717-x. Published onlne 1 May 2012 epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley S, Froehlich J. Advances in the use of naltrexone: an integration of preclinical and clinical findings. Recent Dev Alcohol. 2003;16:217–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati H, O'Brien C, Rabinowitz A, Wortman S, Oslin D, Kampman K, Dackis C. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: specific effects on heavy drinking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:610–625. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000245566.52401.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Hajos M, Seymour P, Kozak R, Majchrzak M, Guanowsky V, WE H, Chapin D, Hoffmann W, Johnson D, Mclean S, Jody Freeman J, Williams K. Preclinical pharmacology of the a4b2 nAChR partial agonist varenicline related to effects on reward, mood and cognition. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:813–824. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Fromme K. Social drinking in a simulated tavern: An experimental analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1984;14:141–163. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(84)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderpalm B, Ericson M, Olausson P, Blomqvist O, Engel J. Nicotinic mechanisms involved in the dopamine activating and reinforcing properties of ethanol. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga R, Macenski MJ, Meisch RA, Roache JD. Human ethanol self-administration. I: Interaction between response requirement and ethanol dose. Behav Pharmacol. 1997;8:91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensland P, Simms J, Holgate J, Richards J, Bartlett S. Varenicline, an α4β nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Pnas. 2007;104:12518–12523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705368104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerts EM, Goodwin AK, Kaminski BJ, Hienz RD. Environmental cues, alcohol seeking, and consumption in baboons: effects of response requirement and duration of alcohol abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:2026–2036. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouda J, Riga D, De Vries W, Stegeman M, van Mourik Y, Schetters D, Schoffelmeer A, Pattij T, De Vries T. Varenicline attenuates cue-induced relapse to alcohol, but not nicotine seeking, while reducing inhibitory response control. Psychopharmacol. 2011;216 doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.