Abstract

A real-time wireless electronic adherence monitor(EAM) and weekly self-report of missed doses via interactive voice response (IVR) and short message service (SMS) queries were used to measure ART adherence in 49 adults and 46 children in rural Uganda. Median adherence was 89.5% among adults and 92.8% among children by EAM, and 99–100% for both adults and children by IVR/SMS self-report. Loss of viral suppression was significantly associated with adherence by EAM (OR 0.58 for each 10% increase), but not IVR/SMS. Wireless EAM creates an exciting opportunity to monitor and potentially intervene with adherence challenges as they are happening.

Introduction

Traditional ART adherence assessments include self-report, pill counts, electronic monitoring, and drug levels.1These measures typically detect adherence challenges after HIV viral suppression has been lost and possibly after drug resistance has developed. Real-time, wireless monitoring strategies could identify adherence challenges before the loss of viral suppression, thus sustaining the effectiveness of first-line regimens.2Experience with real-time adherence monitoring in developing settings to date has been limited to proof-of-concept studies.3,4

This manuscript presents data on the feasibility, validity, and acceptability of real-time adherence monitoring among adults and children in rural Uganda using a wireless electronic adherence monitor (EAM) called Wisepill and self-reported missed doses via interactive voice response (IVR) and short message service (SMS).

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from Partners Healthcare, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. Participants were enrolled by convenience from two longitudinal, observation alcohorts: the Ugandan AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes Study (NCT01596322) and Children's ART Adherence Study (NCT00868257).

Wisepill wirelessly transmits a date-time stamp with each opening using general packet radio service (GPRS). Data are stored for later transmission if network access is temporarily unavailable.

Adults and caregivers of children were offered their choice of IVR or SMS for weekly queries of missed doses in their local language. Successful responses required confirmation of a person identification number and receipt of a numeric response. Queries were repeated multiple times, if needed.

Plasma HIV RNA levels were determined at baseline and six months(lower detection limit of 400 copies/ml).

After one month, adults and caregivers were asked “How would you describe using the Wisepill medication container?” and “How do you feel about someone monitoring how you are taking your medicine every day?”.

Associations between loss of viral suppression at six months and percent adherence during the prior month were determined by logistic regression. The six-month time point was used for both adults and children to ensure uniform exposure to the adherence measures and allow for habituation to monitoring.5Given similar findings, data from adults and children were analyzed together, and data for IVR and SMS were analyzed together. Categories of average adherence were compared with loss of viral suppression by Fisher exact test.6Wireless EAM and IVR/SMS-reported adherence were compared by Spearman correlation. Participants with missing data were excluded from analysis.

Results

Forty-nine adults and 46 children were enrolled. Among adults, median age was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR] 32–43);77.6% were women. At enrollment, median CD4count was 299 cells/mm3 (IQR 246–392), median duration of ART was 15 months (IQR 11 –19), and 43 participants (87.8%) had undetectable HIV RNA. Among children, median age was 7 years (IQR 4–8); 44% were female. At enrollment,medianCD4 percentage was 38 (IQR 30–48), median duration of ART was 32 months (IQR 18–48), and 20 (43.4%) had undetectable HIV RNA. All but two participants were taking twice daily non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based ART.

Adult participants were followed for 53.6 person-years (median 14 months per participant); children were followed for 22.8 person-years (median 6 months per participant). Follow-up periods differed due to distinct funding mechanisms. No participants were lost; one adult died.

Median adherence by wireless EAM was 89.5% (IQR 83.9%–92.3%) among adults and 92.8% (IQR 89.2%–94.6%) among children.

Five adults (10.2%) and 15 caregivers of children (32.6%) received SMS adherence queries. Median percent of successful responses was 86.5% (IQR 48.5%–87.9%)for adults and 84.5% (IQR 66.5%–94.1%)for caregivers. Median self-reported adherence by SMS was 100% (IQR 99.6–100%) for adults and 100% (IQR 99.1–100%) for children.

Thirty-nine adults (79.6%) and 30 caregivers (65.2%) received IVR adherence queries. Median percent of successful responses was 65.0% (IQR 10.0–94.7%) for adults, and 76.1% (IQR 50.8–88.2%) for caregivers. Median adherence was 99.0% (IQR 96.5–100%) for adults and 100% (99.8–100%) for children.

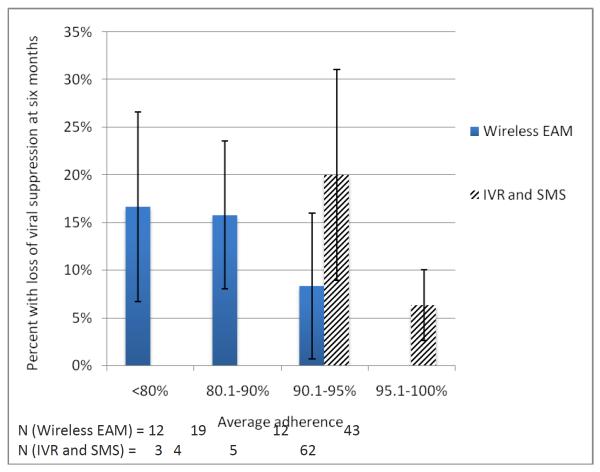

HIV RNA was missing for four adults and four children. Three adults and three children lost viral suppression (7.0% and 15.0% of participants with baseline viral suppression, respectively). Percent adherence by wireless EAM was significantly associated with loss of viral suppression (OR 0.58 for each 10%increase in adherence, IQR 0.34–0.98; p=0.04). Percent adherence by IVR/SMS-report was not associated with loss of viral suppression (OR 1.7, 0.2–15.9; p=0.64) or adherence by wireless EAM (r=0.11, p=0.35). Loss of viral suppression was significantly associated with categories of average adherence with wireless EAM(p=0.02), but not IVR/SMS-report(p=0.54; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Loss of viral suppression and adherence.Loss of viral suppression was significantly associated with categories of average adherence by wireless EAM (p=0.02), but not by IVR and SMS (p=0.54).

All but two participants (97.9%) reported Wisepill was “easy/very easy” to use. All stated they “liked/really liked” being monitored.

Discussion

Real-time wireless electronic adherence monitoring is feasible, valid, and acceptable for HIV-infected adults and children in a rural African setting. While IVR was preferred over SMS, self-reported adherence was less feasible by IVR compared to SMS; neither was a valid measure of adherence.

Wireless EAM has several limitations. First, it is currently prohibitively expensive for routine careat$185per device. Significant cost reductions, however, could be achieved through mass production. Second, several technical problems were encountered, including failed data transmission and inadequate battery life. Technical limitations at the time of data collection prevented quantification of these problems, which may have affected the adherence assessments. Multiple improvements have since been made, including SMS for back-up data transmission7 and a daily “heartbeat” to indicate battery life, device airtime, and signal strength. Third, dedicated data personnel are required to manage this real-time adherence monitoring system, potentially limiting scalability.

The high adherence seen with self-report by IVR and SMS is consistent with traditional forms self-reported adherence.8 While the relative anonymity of technology-assisted adherence reporting could decrease social desirability bias9and frequent reporting could decrease recall bias, data in this study do not support using IVR and SMS for adherence assessment.

Real-time wireless adherence monitoring creates a unique and exciting opportunity to potentially intervene with adherence challenges as they are happening and thusprolong the effectiveness of inexpensive and accessiblefirst-line therapies. Such efficiencies are especially important given current economic constraints and consideration of treatment for many, if not all, of the 34 million people living with HIV.10

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- 1.Kerr T, Walsh J, Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E. Measuring adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: implications for research and practice. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2005;2(4):200–205. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bangsberg DR. Preventing HIV antiretroviral resistance through better monitoring of treatment adherence. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(Suppl 3):S272–8. doi: 10.1086/533415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haberer JE, Kahane J, Kigozi I, Emenyonu N, Hunt P, et al. Real-time adherence monitoring for HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1340–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9799-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haberer JE, Kiwanuka JP, Nansera D, Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR. Challenges in Using Mobile Phones for Collection of Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Data in a Resource-Limited Setting. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1294–1301. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9720-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deschamps AE, Van Wijngaerden E, Denhaerynck K, De Geest S, Vandamme AM. Use of electronic monitoring induces a 40-day intervention effect in HIV patients. J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr. 2006;43:247–248. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000246034.86135.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, et al. Adherence to Protease Inhibitor Therapy and Outcomes in Patients with HIV Infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siedner MJ, Lankowski A, Musinga D, Jackson J, Muzoora C, et al. Optimizing Network Connectivity for Mobile Health Technologies in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, et al. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mensch BS, Hewett PC, Abbott S, Rankin J, Littlefield S, et al. Assessing the reporting of adherence and sexual activity in a simulated microbicide trial in South Africa: an interview mode experiment using a placebo gel. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):407–421. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9791-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garnett GP, Baggaley RF. Treating our way out of the HIV pandemic: could we, would we, should we? Lancet. 2009;373(9657):9–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]