Background: BMPs have emerged as key regulators of kidney fibrosis.

Results: Deletion of miR-22 attenuated renal fibrosis via direct targeting of BMP-7/6. BMP-7/6 in turn transcriptionally regulates miR-22 expression.

Conclusion: miR-22 and BMP-7/6 form a negative feedback circuit.

Significance: The present study is the first to report the effect of miR-22 on BMP signaling and kidney fibrosis.

Keywords: Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), Fibrosis, Gene Regulation, Kidney, MicroRNA

Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests that microRNAs (miRNAs) contribute to a myriad of kidney diseases. However, the regulatory role of miRNAs on the key molecules implicated in kidney fibrosis remains poorly understood. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) and its related BMP-6 have recently emerged as key regulators of kidney fibrosis. Using the established unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model of kidney fibrosis as our experimental model, we examined the regulatory role of miRNAs on BMP-7/6 signaling. By analyzing the potential miRNAs that target BMP-7/6 in silica, we identified miR-22 as a potent miRNA targeting BMP-7/6. We found that expression levels of BMP-7/6 were significantly elevated in the kidneys of the miR-22 null mouse. Importantly, mice with targeted deletion of miR-22 exhibited attenuated renal fibrosis in the UUO model. Consistent with these in vivo observations, primary renal fibroblast isolated from miR-22-deficient UUO mice demonstrated a significant increase in BMP-7/6 expression and their downstream targets. This phenotype could be rescued when cells were transfected with miR-22 mimics. Interestingly, we found that miR-22 and BMP-7/6 are in a regulatory feedback circuit, whereby not only miR-22 inhibits BMP-7/6, but miR-22 by itself is induced by BMP-7/6. Finally, we identified two BMP-responsive elements in the proximal region of miR-22 promoter. These findings identify miR-22 as a critical miRNA that contributes to renal fibrosis on the basis of its pivotal role on BMP signaling cascade.

Introduction

Kidney fibrosis represents a failed wound healing process following a chronic and sustained injury and, regardless of the type of injury and etiology, is the common final outcome of many progressive chronic kidney diseases leading to the destruction and collapse of renal parenchyma and progressive loss of kidney function (1–3). Activated fibroblasts, also known as myofibroblasts, are commonly regarded as the main effector cells responsible for the excess of extracellular matrix production, a key pathological feature of renal fibrosis. Although the origin of the activated fibroblasts pool in the kidney remains controversial, a growing body of evidence indicates that fibrogenic cues in the kidney evoke multiple intracellular signaling pathways that ultimately lead to phenotypic changes in the fibroblasts, resulting in their activation with characteristic expression of several smooth muscle cell markers (1–3). Among the many fibrogenic factors that regulate renal fibrotic processes, TGF-β and connective tissue growth factor are regarded as key fibrogenic cytokines (1–4), whereas bone morphogenic protein-7 (BMP-7)3 and BMP-6, have been known as natural antagonists of TGF-β signaling and anti-fibrogenic factors that have been shown to prevent renal fibrosis in several experimental models (5–11).

BMPs are important signaling molecules that were first identified by their ability to induce bone and cartilage and subsequently were shown to be pleiotropic cytokines controlling a wide variety of biological processes (12, 13). Signaling by BMPs has been long implicated in kidney homeostasis and kidney injury repair (14). In the BMP canonical signaling pathway, the constitutively active type II receptors, upon binding to BMP ligands, phosphorylate and thus activate their type I partners, which in turn phosphorylate their intracellular effectors, the receptor-regulated Smad proteins 1, 5, and 8 (Smad1/5/8) (12, 13, 15). Phosphorylated Smads form complexes with Smad4 and translocate to the nucleus where they regulate expression of their target genes by binding to BMP-responsive elements (BRE) on the promoter region of their target genes (14–17). Although much is known on the BMP canonical pathway, the precise mechanism of its regulation remains inadequately described.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) comprise a broad class of small noncoding RNAs that negatively regulate gene expression by base-pairing to partial or perfect complementary sites in the 3′-UTRs of specific target mRNAs (18, 19). Recent studies from our group (20, 21) and others (22–26) suggest that miRNAs are involved in the pathogenesis and progression of a variety of kidney diseases and hold great therapeutic potential. However, limited information is available on the exact role of miRNAs on renal fibrosis in vivo.

Herein, using the established unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) mouse model of renal fibrosis as our experimental model, we found that miR-22 deletion attenuates kidney fibrosis in vivo by targeting BMP-7/6 and BMP receptor type I receptor (BMPR1B). Our findings also suggest that there is a regulatory feedback circuit between miR-22 and BMP-7/6 signaling, whereby miR-22 targets BMP-7/6, but it is by itself induced by this pathway. Furthermore, we identified two BREs in the miR-22 promoter region, which are responsible for the transcriptional regulation of BMP-7/6 on miR-22 expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue Culture

BALB/c mouse primary kidney fibroblasts were purchased from Cell Biologicals (Chicago, IL). Primary kidney fibroblasts were isolated from wild type or miR-22-deficient kidney cortex as previously described (27). TGF-β1 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). HEK 293T cells and HeLa cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured as previously described (28).

miRNA Extraction, Real Time RT-PCR, in Situ Hybridization, and Northern Blot

miRNAs were extracted using a total RNA purification kit (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, Canada) (15). The TaqMan microRNA reverse transcription kit and its compatible TaqMan microRNA assays for U6 snRNA and miR-22–3p (Applied Biosystems) were used to quantify the expression level of mir-22 on a CFX96 real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Individual samples were run in duplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least three times. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (29). miR-22 chromogenic in situ hybridization assays were carried out as previously described (30), in collaboration with Bioneer A/S (Hørsholm, Denmark) using specific miR-22–3p probe (ACAGTTCTTCAACTGGCAGCTT) or scramble probe (TGTAACACGTCTATACGCC CA). Northern blots were carried out using [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) end-labeled miRNA locked nucleic acid probes for miR-22 and control U6 snRNA (Exiqon) (31).

In Silica Targeted Gene Analysis of miR-22

Three separate algorithms (miRanda, TargetScan, and PicTar) were used to assess potential miRNAs that target BMP-7 and BMP-6. These programs were also used to analyze binding sites in target mRNAs for miR-22. The RNA Hybrid program (32) was used to predict the secondary structure and free energy of the RNA/miRNA duplex.

Plasmids, Mutagenesis, and miRNA Transfection

The 3′-UTRs of the mouse Bmp6 gene (NM_001718), Bmp7 gene (NM_001719), and Bmpr1b gene (NM_001203) were amplified from mouse primary kidney fibroblasts genomic DNA by PCR using HotMaster TaqDNA Polymerase (5PRIME), with the following primers: GTCTCGAGTTGAAGCTGGTGTGTGTGT (Bmp6 forward) and GAGAATTCACCACCGAGAGTCAACACA (Bmp6 reverse); GTCTCGAGCTCTTCCTGAGACCCTGACC (Bmp7 forward) and GAGAATTCGTCAGAATAAACCAAGAAACGG (Bmp7 reverse); and GTCTCGAGTGCCTGGGACCACAGCTTGG (Bmpr1b forward) and GAGAATTCACTGTGCCGTGCACACTTCT (Bmpr1b reverse). The PCR products were cloned between the XhoI and EcoRI sites of luciferase reporter vector 3.1-luc, kindly provided by Dr. Ralph Nicholas (Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH) (33). Putative miR-22 binding site GGCAGCU (nucleotides 153–159) in mouse Bmp7 was mutated into GAUGAUU by oligonucleotide-directed PCR.

Human miR-22 gene proximal promoter (−1197 to +49) (34) was cloned from HEK 293T genomic DNA by PCR using HotMaster TaqDNA Polymerase, with the following primers: GTAGGTACCGAAGGAAAAGGCATGGATTTCAGTCC (forward), GCAGCTAGCAGGGGGAGCAAATCACTGCGTCC (reverse). The 1246-bp PCR product was cloned between KpnI and NheI site of promoter-less luciferase reporter vector pGL4.10 [luc2] (Promega, Madison, WI). Putative mouse miR-22 promoter was retrieved from GenBank and aligned to human miR-22 promoter using Clustal Omega. Binding sites for transcription factors were analyzed using rVista 2.0 (35). Potential BREs in this promoter region were mutated through oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis by regular PCR using the following primers: GCTCGTGCGTCACGAATTCGCCAGCTGATCGG (for BRE-1), CAATCAGAGCCAGAGAATCCGGAGAGGCGGGA (for BRE-2) and CATTGCAAACGCAGAATTCGTGGCTTTCGCCT (for BRE-3), where the mutated BRE sequence is underlined. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Pre-miRNA precursor and anti-miR miRNAs molecules were purchased from Invitrogen. miRNA mimics and miRNA inhibitors were transfected into cultured cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 40 nm (20, 21).

For experiments testing the effect of BMP-7/6 signaling on miR-22 expression, HEK 293T cells or HeLa cells were serum-starved overnight and pretreated with vehicle (Me2SO) or 10 μm dorsomorphin (Sigma) for 30 min before treatment with 100 ng/ml BMP-6 or 100 ng/ml BMP-7 (R&D Systems) for the indicated time (36).

Luciferase Reporter Assays

For experiments using 3.1-luc luciferase reporter constructs in vitro, 1.5 × 105 HeLa cells were plated in 12-well plates. 1.5 μg of 3.1-luc empty vector, or 3.1-luc-Bmp7,-Bmp6 or-Bmpr1b constructs, 50 ng of pSV-β-gal control vector (Promega), and 30 nm of miR-22 mimics were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Following 48 h of transfections, luciferase activity was measured using Steady-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) on a FLUOstar Omega luminometer (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC) as previously reported (20, 21), using β-gal as an internal control.

For experiments using pGL4.10 luciferase reporter constructs in vitro, 1.5 × 105 HEK 293T cells were plated in 12-well plates. 3.3 μg of pGL4.10 empty vector or miR-22 promoter constructs (wild type or BRE mutants) and 50 ng of pSV-β-gal control vector (Promega) were transfected into each well using a calcium phosphate transfection kit (Invitrogen) following manufacturer's instructions. 24 h post-transfection, cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured using a Steady-Glo luciferase assay system on a FLUOstar Omega luminometer, using β-gal as an internal control (20, 21).

Biotin-miR-22 Pulldown

Capture of miR-22 target mRNAs by streptavidin beads pulldown using biotinylated synthetic miR-22 was carried out as previously described (37, 38). Briefly, primary renal fibroblasts isolated from kidney cortex of miR-22−/− mice were transfected with 50 nm biotin-labeled nontargeting mimic or biotin-miR-22 mimic (custom synthesized from Sigma). Cells were harvested 24 h later in biotin pulldown lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm KCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1/100 complete protease inhibitor (Sigma), and RNase OUT (50 units/ml; Invitrogen)). 100 μl of M-280 streptavidin-coated Dynabeads at a concentration of 10 ng/ml (Invitrogen) were washed two times in lysis buffer and added to 1 ml of cell extract, incubated overnight at 4 °C. Pulldowns were washed five times in lysis buffer. RNAs from the beads (pulldown RNA) or from 10% of the cell extract (input RNA) were extracted for downstream applications. The level of mRNA in the biotin-labeled control miRNA or miR-22 was quantified by RT-qPCR. For RT-qPCR, mRNA levels were normalized to a housekeeping gene (Gapdh or Ubiquitin C). The enrichment ratio of the control-normalized pulldown RNA to the control-normalized input levels was then calculated (37).

Quantitative Real Time PCR

SYBR Green-based qPCR on a CFX96 real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) were used to analyze the relative expression levels of the following genes with the different primer sets: collagen I, TGCCGCGACCTCAAGATGTG (forward) and CACAAGGGTGCTGTAGGTGA (reverse); collagen III, GCGGAATTCCTGGACCAAAAGGTGATGCTG (forward) and CGGATCCGAGGACCACGTTCCCCATTATG (reverse); fibronectin, 5′-GCGGTTGTCTGACGCTGGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGGTTCAGCAGCCCCAGGT-3′ (reverse); αSMA, ACTGGGACGACATGGAAAAG (forward) and CATCTCCAGAGTCCAGCACA (reverse); Bmp7, TGTGGCAGAAAACAGCAGCA (forward); TCAGGTGCAATGATCCAGTCC (reverse); Bmp6, CCAACCACGCCATTGTACAGA (forward); GGAATCCAAGGCAGAACCATG (reverse); Id1, ACCCTGAACGGCGAGATCA (forward) and TCGTCGGCTGGAACACATG (reverse); pri-mir-22, GGAACCTGTGCCTCCCAC (forward) and TTCCCACTGCCACACAGAC (reverse); and Gapdh, 5′-CCTTCATTGACCTCAACTAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGAAGGCCATGCCAGTGAGC-3′ (reverse).

Animal Studies

All animal studies were conducted according to the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (National Institutes of Health publication 85023, revised 1985) and the guidelines of the IACUC of Baylor College of Medicine. For experiments using the UUO model of kidney injury, 8-week-old male C57BL/6J-Albino miR-22+/+ and C57BL/6J-Albino miR-22−/− mice were obtained from our in-house breeding colony (39). Obstructive surgery was performed following the administration of anesthetics by left flank ureteral ligation according to previously described reports (26, 40). Mice subjected to sham surgery received the same treatment, without ligation of the ureter. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after initial surgery. Isolated kidneys were cold-perfused with Hanks' balanced salt solution, formalin-fixed for kidney histology, and snap-frozen for subsequent RNA and protein isolation, respectively. Immunohistochemistry staining and quantification of Picosirius Red and αSMA were carried out as previously described (39, 41).

Statistical Analysis

All data are shown as means ± S.E. Statistical significance was assessed by performing analysis of variance followed by the Turkey-Kramer post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons using an α value of 0.05 in GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA). Western blot signals were quantitated using software National Institutes of Health ImageJ version 1.42q.

RESULTS

Screening of miRNAs That Target BMP-7/6 in the Kidney

BMP-7 and BMP-6 have recently emerged as key anti-fibrogenic proteins in several experimental models of kidney fibrosis (5–11). Although it is known that BMP signaling is tightly regulated at various layers, the potential interaction between miRNAs and BMP-7/6 signaling in the kidney has not been established. We hypothesized that miRNAs may play critical roles in regulating BMP-7/6 signaling and hence contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of kidney fibrosis.

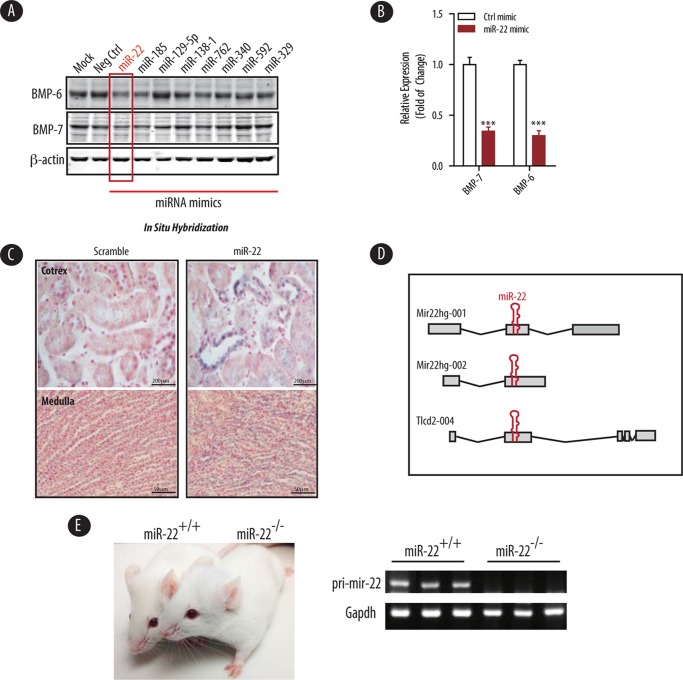

To test this hypothesis, we employed several in silica analyses of BMP-7/6 mRNAs for potential miRNAs predicted to target these two genes by binding to their 3′-UTRs. Among a number of conserved, putative BMP-7/6 targeting miRNAs, we identified miR-22 and miR-185 as potential contributors to the regulation of BMP-7/6 proteins. To examine whether these miRNAs could indeed repress BMP-7/6 expression, we transfected primary mouse renal fibroblasts with either control mimic or mimics from each respective potential miRNA. Immunoblot assays revealed that the protein expression of BMP-7/6 was significantly repressed by miR-22 (Fig. 1A). Importantly, miR-22 overexpression elicited knockdown of BMP-7 and BMP-6 protein levels by ∼65 and ∼70%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Thus, we selected miR-22 as our primary target for further investigation.

FIGURE 1.

BMP-7/6 are direct targets of miR-22 in the kidney. A, cultured primary renal fibroblasts were transfected with the indicated miRNA mimics predicted to target BMP-7 in silica. Cell lysate were analyzed for the expression of BMP-6 and BMP-7 by immunoblotting using β-actin as a loading control. B, densitometric analysis of BMP-7 and BMP-6 expression in cells transfected with control mimic (Ctrl mimic) or miR-22 mimics shown in A (n = 3). C, expression pattern of miR-22 in a wild type C57 mouse kidney cortex as detected by in situ hybridization with the indicated probes. Blue is the in situ hybridization signal, and red is nuclear counterstaining. Scale bars denote 200 μm. D, genomic structure of the mouse mir-22 host gene. The miR-22 host gene is depicted along with several alternative splice variants. E, representative image of wild type and miR-22−/− mice (left panel). Real time PCR of kidney cortex RNA to show that pri-mir-22 expression could not be detected in miR-22−/− mice compared with miR-22+/+ controls. Gapdh served as the reference gene (right panel).

To examine the subcellular localization of miR-22 within the kidney, we performed in situ hybridization with probes specific to mature miR-22. Our data depicted in Fig. 1C indicate that miR-22 is predominantly localized to the cortical distal convoluted tubules. However, we also observed a lesser degree of miR-22 staining in the collecting ducts, proximal tubules, and within the medullary regions (Fig. 1C, lower panels). No signal was observed in negative control sections labeled with the scramble probe.

To experimentally validate these results in vivo, we generated miR22 knock-out mice on C57 background. miR-22 is expressed from a single locus on mouse chromosome 11 that encodes a non-protein-coding gene (mir22hg) with three putative exons. The host gene has two transcripts in mouse because of alternative splicing (Fig. 1D). miR-22 is also embedded within exon 2 of a non-protein-coding transcript Tlcd2 (Fig. 1D). To generate miR-22 knock-out mice, we deleted the whole exon containing pri-mir-22 as recently described (Fig. 1D) (39). miR-22 knock-out mice were then backcrossed into C57BL/6 background. miR-22-deficient mice were healthy with normal fertility, body weight, and life span when housed in standard sterile conditions (Fig. 1E, left panel). Real time PCR analysis confirmed that pri-mir-22 expression was not detected in the homozygote knock-out mice (Fig. 1E, right panel).

Targeted Deletion of miR-22 Ameliorates Features of Renal Fibrosis in the UUO Model of Kidney Fibrosis

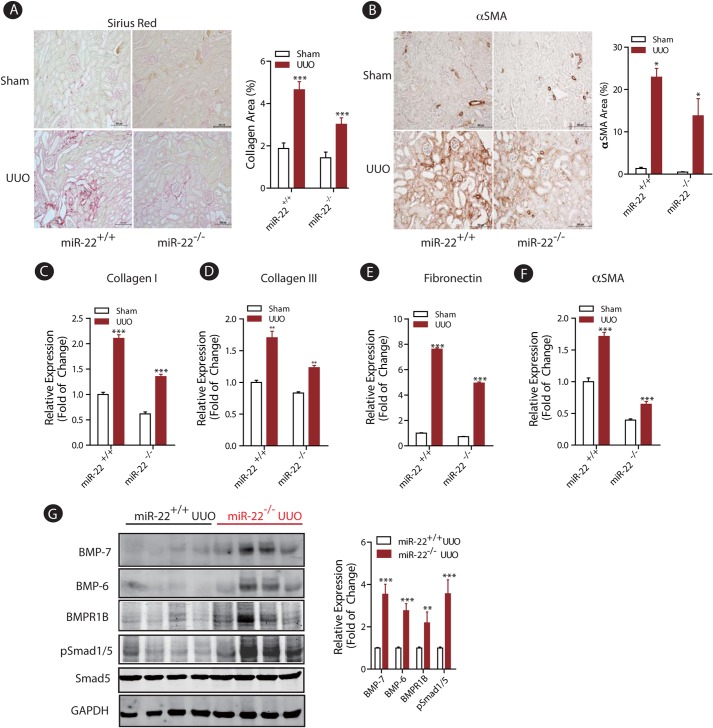

To test the role of miR-22 on renal fibrosis in vivo, we used the well characterized UUO mouse model of kidney injury, which results in progressive interstitial fibrosis (42). Wild type and miR-22−/− mice were subjected to obstructive or sham injury for 10 days. Following this period, the degree of renal fibrosis was evaluated by Picrosirius Red staining of kidney sections. As expected, the UUO injury in wild type mice led to a significant increase in type I collagen deposition as measured by relative intensity of Picrosirius Red-positive tissue (Fig. 2A). Targeted deletion of miR-22, however, impeded the observed abundance of type 1 collagen in the UUO model (Fig. 2A). We also quantified the expression of αSMA, a key marker of activated myofibroblasts. Immunohistochemistry staining revealed that UUO led to significantly elevated expression of αSMA in wild type mice (Fig. 2B), whereas similar to attenuated type 1 collagen expression, the expression of αSMA was significantly reduced in the miR-22−/− mice compared with wild type (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Targeted deletion of miR-22 significantly improved renal fibrosis in the UUO model of kidney injury. A, representative Picosirius Red staining pictures of kidney tissues from wild type or miR-22 knock-out mice subjected to sham or UUO injury (10 days, n = 5). Quantitative results of the percentage of collagen-positive area are shown as means ± S.E. ***, p < 0.001 (n = 5). Scale bars denote 500 μm. B, representative light micrographs of kidney tissues from wild type or miR-22 knock-out mice subjected to sham or UUO injury (10 days, n = 5) stained for αSMA protein. Quantitative results of the percentage of αSMA area are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05 (n = 5). Scale bars denote 500 μm. C–F, real time qPCR analysis depicts expression of several pro-fibrotic genes from kidney cortices of wild type or miR-22 knock-out mice subjected to sham or UUO injury (10 days, n = 5). Measured transcript levels were normalized to Gapdh mRNA expression. Samples were run in triplicate (n = 5). The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001(n = 5). G, immunoblot analysis of kidney cortices of miR-22 knock-out mice subjected to UUO injury compared with injured wild type controls. GAPDH served as a loading control. Densitometric analysis results of the indicated protein expression level normalized to GAPDH are shown. The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 4).

In considering the ramifications of the effect of miR-22 on other key fibrotic genes, total RNAs were extracted from kidney cortices of mice after UUO injury from each group and subjected to quantitative real time PCR. As expected, UUO injury induced the expression of several fibrotic marker genes in wild type mice (Fig. 2, C–F). In contrast, mRNA expression of each of these genes, including collagen I, collagen III, fibronectin, and αSMA, was significantly suppressed in miR-22-deficient mice following UUO (Fig. 2, C–F).

To establish the regulatory role of miR-22 on BMP-7/6 protein expression in vivo, we extracted kidney cortex proteins from wild type and miR-22 knock-out mice following UUO injury and performed several immunoblot assays. As shown in Fig. 2G, the protein levels of BMP-7 and BMP-6 were ∼3.5- and 2.5-fold higher, respectively, in miR-22−/− mice compared with wild type controls in UUO conditions. BMPR1B, the type I receptor for BMP-7/6 signaling, was similarly up-regulated by ∼2.0-fold in miR-22−/− UUO mice compared with UUO control mice (Fig. 2G). To assess whether these genetic changes had downstream functional consequences, we probed our samples for phospho-Smad1/5, the critical downstream mediator of BMP signaling. Although total Smad5 levels were comparable among wild type and miR-22−/− mice following UUO injury, deletion of miR-22 led to significantly higher phosphorylation of Smad1/5, indicating enhanced expression of BMP downstream targets in miR-22-deficient mice (Fig. 2G). Thus, our findings suggest that targeted deletion of miR-22 enhances BMP-7/6 signaling in vivo, which may contribute to the amelioration of renal fibrosis.

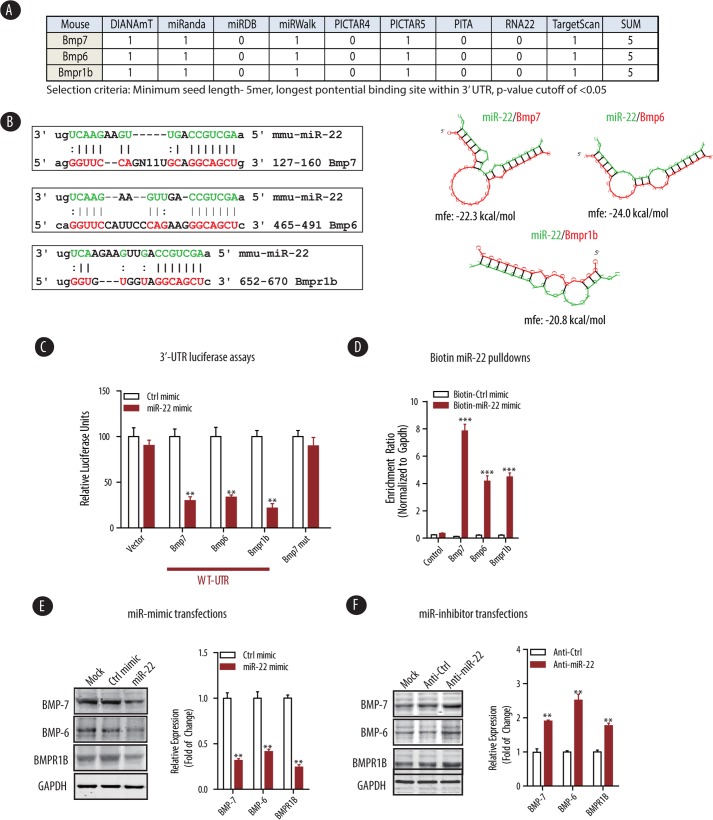

miR-22 Directly Targets Key Components of BMP Signaling

Several algorithms suggest the existence of miR-22 binding sites in the 3′-UTR of mouse Bmp7, Bmp6, and Bmpr1b mRNAs (Refs. 18 and 19 and Fig. 3A). Thus, to examine whether BMP-7/6 mRNAs are bona fide targets of miR-22, we evaluated the 3′-UTR sequence of BMP-7/6 mRNAs for the presence of a miR-22 binding site. As shown in Fig. 3B, complementary binding of miR-22 seed sequence to these binding sites in the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs are expected to generate a relatively stable secondary structure between miR-22 and Bmp7, Bmp6, or Bmpr1b (ΔG<-20 kcal/mol) (Fig. 3B). To confirm that miR-22 indeed binds directly to 3′-UTR to repress the expression of these target genes, we amplified the 3′-UTR of Bmp7, Bmp6, or Bmpr1b from mouse genomic DNA by PCR and subcloned them into the pcDNA3.1-luc empty vector. Luciferase reporter assays indicated that when these 3′-UTR reporter constructs were introduced into HeLa cells, their transcriptions were markedly repressed by co-transfection of miR-22 mimics but not with the control mimic (Fig. 3C). Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis of the putative miR-22 binding site in Bmp7 from GGCAGCU into GAUGAUU, however, abrogated the miR-22-mediated repression of the mutant Bmp7 luciferase construct (Fig. 3C), suggesting that miR-22 represses the expression of BMP-7 by binding to a unique binding site in the BMP-7 3′-UTR.

FIGURE 3.

miR-22 targets several components of BMP-7/6 signaling, including BMPR1B. A, representative table of algorithms highlighting the potential number of miR-22 binding sites within the 3′-UTR of indicated genes in BMP signaling. B, sequence alignment of miR-22 with the mouse Bmp7, Bmp6, and Bmpr1b 3′-UTRs based on TargetScan algorithm (left panel). miR-22 can potentially form strong secondary structures with the target sequence of 3′-UTRs of Bmp7, Bmp6, and Bmpr1b (right panel, predicted by the RNA Hybrid program). C, HeLa cells were co-transfected with empty vector (Vector) and three independent plasmids expressing either 3.1-luc-Bmp7, -Bmp6, or -Bmpr1b wild type 3′-UTR (WT-UTR) or a 3.1-luc-Bmp7 mutant 3′ UTR (BMP-7 mut) and the indicated control mimic (Ctrl mimic) or miR-22 mimic. Luciferase activities were normalized to β-gal activities. The results were obtained from three independent experiments. The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01 (n = 3). D, miR-22-deficient renal fibroblasts were transfected with either biotin-control mimic (Biotin-Ctrl mimic) or biotin-miR-22 mimic (Biotin-miR-22 mimic) and subjected to streptavidin pulldown, followed by qPCR detection of enrichment of indicated miR-22 target genes (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). The results were obtained from three independent experiments. The data are shown as means ± S.E. ***, p < 0.001 (n = 4). E, wild type renal fibroblasts were transfected with control mimic (Ctrl mimic) or miR-22 mimic followed by immunoblot analysis of expression level of the indicated miR-22 targets. Densitometric analysis results of the indicated protein expression level normalized to GAPDH are shown. The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01 (n = 3). F, wild type renal fibroblasts were transfected with control inhibitor (Anti-Ctrl) or miR-22 inhibitor (Anti-miR-22) followed by immunoblot analysis of expression level of the indicated miR-22 targets. Densitometric analysis results of the indicated protein expression level normalized to GAPDH are shown. The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01 (n = 3).

To further provide a direct evidence for miR-22 regulated silencing of its target mRNAs, we used a biotin-miRNA pulldown assay to capture target mRNAs bound to biotin-labeled miR-22 within the functional RNA-induced silencing complex (37, 38). To eliminate endogenous miR-22 interference with this procedure, we isolated primary renal fibroblasts from the kidney cortices of miR-22−/− mice and transfected them with a biotin-labeled control miRNA mimic or miR-22 mimic. Cell lysates were extracted and subjected to pulldown assay using streptavidin-coated Dynabeads. Total RNAs were isolated from the precipitated beads and subjected to quantitative RT-qPCR analysis (Fig. 3D). In the biotin-miR-22 pulldown, transcripts of potential miR-22 targets, including Bmp7, Bmp6, and Bmpr1b were enriched to 7.9-, 4.2-, and 4.5-fold respectively, whereas transcript of control Ubc (ubiquitin C, coding gene for polyubiquitin precursor) was not enriched (Fig. 3D), suggesting that biotin-labeled miR-22 mimic incorporates into a functional RNA-induced silencing complex with its potential target mRNAs, including Bmp7, Bmp6, and Bmpr1b.

To confirm the impact of miR-22 on BMP expression, we employed a classic dual gain of function and loss of function approach. We used primary renal fibroblasts from wild type miR-22 mice to assess the impact of miR-22 mimic or inhibitor on BMP family member expression. Consistent with our initial findings in Fig. 1A, we found that miR-22 mimic inhibits the protein expression of BMP-7, BMP-6, and BMPR1B in primary renal fibroblasts (Fig. 3E). Conversely, inhibition of miR-22 could potentiate the expression of BMP-7, BMP-6, and BMPR1B (Fig. 3F). Taken together, these results suggest that miR-22 directly represses the protein expression of BMP-7, BMP-6, and BMPR1B by binding to the 3′-UTR of these target mRNAs.

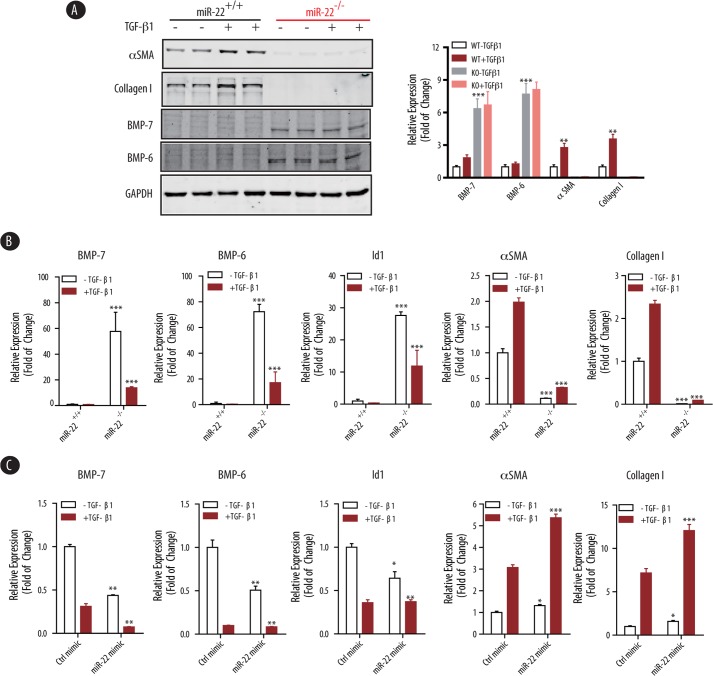

miR-22 Regulates TGF-β1-mediated Profibrotic Program in Renal Fibroblasts

Given the importance of the dynamic interplay between TGF-β and BMP-7/6 signaling pathways (1–4), we next examined the effect of miR-22 on TGF-β-induced pro-fibrogenic genes and BMP-7/6 in a well defined in vitro culture system, in which isolated renal fibroblasts from kidney cortices of wild type and miR-22−/− mice fibroblasts were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Expression of BMP-7/6, BMPR1B, and several fibrogenic genes were analyzed at the protein and mRNA levels. As expected, TGF-β1 significantly induced both protein and mRNA expression of αSMA and collagen I in wild type primary renal fibroblasts (Fig. 4, A and B). However, αSMA and collagen I expression in renal fibroblasts from miR-22−/− mice were abolished (Fig. 4, A and B), suggesting that knock-out of miR-22 leads to potent suppression of these fibrotic genes. Consistent with our previous findings, both protein and mRNA expression levels of BMP-7 and BMP-6 were significantly higher in the miR-22−/− fibroblasts than wild type controls. We also found that the expression of Id1 (inhibitor of DNA binding 1), a well characterized downstream target gene for BMP-7/6, was significantly higher in the miR-22−/− fibroblasts as compared with wild type controls (Fig. 4B), suggesting enhanced BMP-7/6 signaling in miR-22 knock-out renal fibroblasts.

FIGURE 4.

Knock-out of miR-22 attenuates, and rescue of miR-22 partially restores, the pro-fibrogenic program induced by TGF-β1. A, primary mouse renal fibroblasts isolated from wild type or miR-22 knock-out mice were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, 24 h). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. GAPDH served as a loading control. Densitometric analysis results of the indicated protein expression level normalized to GAPDH are shown on the right panel. The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 3). B, real time qPCR analysis of total RNAs extracted from the wild type or miR-22 knock-out renal fibroblasts as in A. Measured transcript levels were normalized to Gapdh mRNA expression. Samples were run in triplicate. The data are shown as means ± S.E. ***, p < 0.001 (n = 3). C, primary renal fibroblasts isolated from miR-22 knock-out mice were transfected with control mimic (Ctrl mimic) or miR-22 mimic, treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, 24 h), followed by real time qPCR analysis. Measured transcript levels were normalized to Gapdh mRNA expression. Samples were run in triplicate. The data are shown as the means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 3).

We then examined whether the effects of miR-22 on BMP-7/6 signaling could be rescued when cells were transfected with miR-22 mimic. To this end, miR-22−/− renal fibroblasts were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml for 24 h), followed by RT-qPCR analysis. Although overexpression of miR-22 led to the repression of Bmp7 and Bmp6 at the post-transcriptional level with decreased expression of downstream Id1 gene (Fig. 4C), ectopic expression of miR-22 with miR-22 mimic in miR-22−/− renal fibroblasts partially restored the expression of αSMA and collagen I, at the basal level (cells without TGF-β treatment) as well as following induction with TGF-β1 (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these findings suggest that miR-22 plays a critical role in the dynamic interactions between BMP-7/6 and TGF-β signaling pathways.

Transcriptional Regulation of miR-22 by BMP-7/6 Signaling

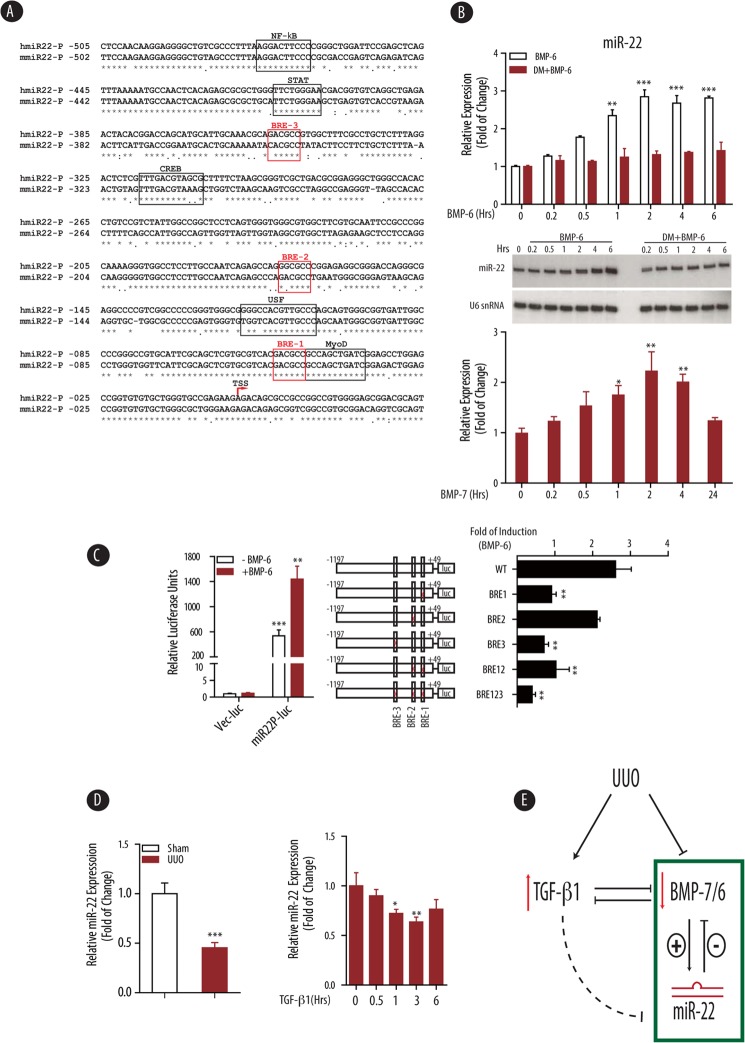

The regulation of miR-22 expression is largely unknown, although there are reports indicating that miR-22 expression can be induced by several nuclear receptors, including vitamin D3 (43, 44), testosterone (45), and retinoic acids (46). To study the transcriptional regulation of miR-22, we retrieved mouse miR-22 promoter sequence from genomic sequence of mir22hg gene, based on homologous alignment to recently published human miR-22 promoter sequence (34). As shown in Fig. 5A, the proximal region (−500 bp upstream of transcription starting site) of mouse and human miR-22 promoter is highly homologous (80% identical), suggesting a possible conserved regulation of miR-22 expression. Further careful examination of the miR-22 proximal promoter region for transcription factor binding sites revealed several binding sites for MyoD, CREB, and NF-κB (Fig. 5A). Importantly, there were three consensus BREs in this region, including GACGCC (BRE-1 and BRE-3) and GGCGCC (BRE-2) (Fig. 5A). This was quite surprising because BREs, which are believed to serve as the binding sites for phosphorylated Smad1/5 transcription complex (12, 15–17), are commonly found in BMP target genes (e.g., Id1 GACGCC, Id2 GGCGCC, and Id3 GGCGCC) (47–51).

FIGURE 5.

Transcriptional regulation of miR-22 by BMP-7/6 signaling. A, sequence alignment of human and mouse putative mir-22 promoter proximal region (−505 to +35 nucleotides for human mir-22). Consensus binding sites for indicated transcription factors are indicated. TSS, transcription start site. B, HEK 293T cells were pretreated with vehicle or dorsomorphin (DM, 10 μm, 0.5 h) followed by BMP-6 treatment (100 ng/ml) for the indicated time. Expression of mir-22 in total RNAs was analyzed by real time qPCR (upper panel) and Northern blot using U6 snRNA as a loading control (middle panel). HeLa cells were stimulated with BMP-7 (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Expression of mir-22 in total RNAs was analyzed by real time qPCR (lower panel). Measured mir-22 transcript levels were normalized to U6 snRNA expression. Samples were run in triplicate. The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 3). C, luciferase assays of wild type or BRE mutants of human mir-22 promoter in HEK 293T cells. Left panel, HEK 293T cells were transfected with pGL4 vector control (Vec-luc) or human miR-22 promoter construct (miR22P-luc), treated with or without BMP-6 (100 ng/ml, 24 h), and followed by luciferase assay. Middle panel, schematic structure of wild type and combinations of BRE-mutants. The locations of three potential BREs are indicated. Right panel, HEK 293T cells were transfected with the indicated human miR-22 promoter constructs, treated with or without BMP-6 (100 ng/ml, 24 h), and followed by luciferase assay. Luciferase activities were normalized to β-gal activities. Fold of induction by BMP-6 treatment relative to no BMP-6 treatment are shown. The results were obtained from three independent experiments. The data are shown as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 3). D, miR-22 level is down-regulated in wild type mice subjected to UUO injury in vivo (left panel) and down-regulated by TGF-β1 in primary mouse renal fibroblasts in vitro (right panel). Wild type mice were subjected to sham or UUO injury (10 days, n = 5). Renal fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Expression of mir-22 in total RNAs was analyzed by real time qPCR. Measured mir-22 transcript levels were normalized to U6 snRNA expression. Samples were run in triplicate. The data are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 3). E, proposed regulatory mechanism of miR-22 on BMP-7/6 signaling in the context of UUO. UUO injury leads to up-regulated TGF-β1 levels and decreased levels of BMP-7/6. BMP-7/6 induces miR-22 transcription, which in turn represses BMP-7/6 signaling by targeting BMP-7, BMP-6, and BMPR1B. TGF-β1 can also indirectly down-regulate miR-22 expression level.

The existence of several BREs in miR-22 promoter prompted us to examine whether miR-22 and BMP-7/6 are in a regulatory negative feedback loop, in which not only miR-22 inhibits BMP-7/6 gene, but miR-22 by itself is regulated by BMP-7/6. To test this possibility, cultured human embryonic fibroblasts HEK 293T cells were treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-6 in different time points. RT-qPCR analysis of mir-22 gene revealed that BMP-6 treatment indeed leads to increased levels of miR-22 in a time-dependent manner, reaching a plateau at ∼2 h (Fig. 5B, top panel), indicating that mir-22 is an early responsive gene of BMP-6. To further test whether BMP signaling directly enhances miR-22 expression, we examined the effect of BMP inhibition on the endogenous levels of miR-22 RNA. To this end, HEK 293T cells were pretreated with dorsomorphin, a selective small molecule inhibitor of BMP type 1 receptors (36), prior to BMP-6 treatment. Pretreatment of dorsomorphin abrogated the expected response of miR-22 to BMP-6 (Fig. 5B, top panel), suggesting that induction of miR-22 by BMP-6 requires functional type I BMP receptors. Total RNAs from these cells were also subjected to Northern blot using specific miR-22 probe. Consistent with our previous findings in RT-qPCR (Fig. 5B, top panel), we observed that miR-22 RNA level was also rapidly induced by BMP-6 within 6 h as detected by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 5B, middle panel). In a similar study using BMP-7, we observed an almost identical pattern, showing early response of miR-22 to BMP-7 (Fig. 5B, bottom panel). Thus, our data suggest that miR-22 is an immediate early gene induced by BMP-7/6 signaling.

We then generated luciferase reporter construct with the human miR-22 proximal promoter and examined its response to BMP-7/6 signaling. Cells were transfected with empty vector pGL4.1 and wild type miR-22 promoter construct, treated with BMP-6 (100 ng/ml for 16 h) prior to luciferase assay. Under these conditions, wild type human miR-22 promoter construct showed an average of ∼500-fold higher luciferase activity compared with empty vector (Fig. 5C). Importantly, BMP-6 treatment further increased miR-22 promoter activity ∼2.6-fold (Fig. 5C, left panel), indicating that miR-22 responds to BMP-6 stimulus at the transcriptional level.

To delineate the BRE element(s) responsible for BMP induction in miR-22 promoter, we generated a series of miR-22 promoter mutant constructs, where BRE-1, BRE-2, and BRE-3 were each separately or in combination mutated (Fig. 5C, middle panel). Subsequent luciferase assays indicated that mutation of BRE-1 and BRE-3, but not BRE-2, significantly reduced the response of miR-22 to BMP-6 (Fig. 5C, right panel). Double mutant BRE-1/BRE-2 had similar BMP-6 response to BRE-1, whereas triple mutant BRE-1/BRE-2/BRE-3 was completely unresponsive to BMP-6 treatment (Fig. 5C, right panel). Taken together, these findings indicate that BRE-1 and BRE-3, but not BRE-2, are responsible for BMP-6 induction in miR-22 and support the notion that miR-22 forms a regulatory loop with BMP-7/6 signaling.

In light of the observed transcriptional regulation of miR-22 by BMP-7/6, we decided to verify whether miR-22 underwent a similar pattern of down-regulation in vivo under UUO conditions. To this end, we examined miR-22 expression by qPCR in kidney cortices from wild type mice that had undergone UUO and found that miR-22 was indeed down-regulated by ∼2-fold when compared with sham controls (Fig. 5D, left panel). This result suggests sustained BMP-7/6 is critical for miR-22 regulation within the kidney.

In addition to BMP signaling, we were also interested in exploring whether known fibrogenic factors, i.e., TGF-β1, could likewise down-regulate miR-22 expression. To test this, mouse renal fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) over several time points. We found significant down-regulation of miR-22 by qPCR (Fig. 5D, right panel). Taken together, these results suggest that both TGF-β1 and BMP-7/6 may contribute to the expression levels of miR-22 in the kidney.

DISCUSSION

Emerging evidence suggests that BMP-7/6, members of the TGF-β superfamily of cysteine knot cytokines, play pivotal roles in kidney homeostasis mainly by antagonizing TGF-β-induced profibrogenic signaling that contribute to the accumulation of the extracellular matrix (5–11). In this study, we uncover a critical role of miR-22 on BMP signaling and renal fibrosis by providing strong evidence that miR-22 directly targets BMP-7, BMP-6, and BMPR1B. In support of our conclusions, we found that targeted deletion of miR-22 significantly attenuated renal fibrosis in the well characterized UUO model of kidney fibrosis. Knockdown of miR-22 both genetically or pharmacologically, resulted in elevated BMP-7/6 protein levels and enhanced BMP-7/6 downstream targets. Importantly, using miR-22-deficient primary renal fibroblasts, we demonstrated that miR-22 mimic could partially rescue the profibrotic effect of TGF-β1. Finally, we made the novel observation that BMP-7/6 per se could induce miR-22 at the transcriptional level through two consensus BREs in the proximal promoter region of miR-22 gene. Our findings suggest that miR-22 is an immediate early target gene of BMP-7/6, requiring an intact BMP-7/6 signaling, because pretreatment with dorsomorphin, a selective small molecule inhibitor of BMP type 1 receptor, abolished the induction of miR-22 expression by BMP-6. Taken together, our data suggest that miR-22 serves as an important regulator of BMP homeostasis and kidney fibrosis in response to extracellular signals.

Recent studies from our group (20, 21) and others (22–26) have demonstrated that microRNAs play important roles in the development and progression of a variety of kidney diseases leading to kidney fibrosis as their final common pathway. Among miRNAs modulating kidney fibrosis, miR-21 has been recently reported by several groups to positively regulate renal fibrosis in UUO and ischemia reperfusion injury (22, 26, 52–55). Similarly, miR-200 has also been implicated in renal fibrosis (56, 57). The present study is the first to report the effect of miR-22 on BMP homeostasis and kidney fibrosis. However, we recognize that the effect of miR-22 on BMP-7/6 could be kidney- and tissue-specific. For instance, we have recently reported an association between miR-22 and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis (39), where in contrast to the current findings, deletion of miR-22 was associated with enhanced cardiac fibrosis (39, 58). Our interpretation of these functional differences on the effect of miR-22 on tissue fibrosis is that the effect of miRNAs on their target mRNAs have been convincingly shown to be tissue- and temporal-dependent (59, 60). Thus, miR-22 could preferentially target BMP-7/6 in the kidney, where BMP-7/6 are highly expressed, whereas other miR-22 targets (e.g., purine-rich element-binding protein B (39) or HDAC4 (58)) could be preferentially targeted by miR-22 in the heart. Finally, it is a canonical feature of miRNAs to exert their effects on target genes in a pleiotropic manner. Therefore, several other important targets, in addition to BMP-7/6 and BMPR1B, may potentially mediate the effect of miR-22 on renal fibrosis.

Our findings also suggest that miR-22 forms a negative feedback circuit with BMP-7/6 signaling (Fig. 5E). This finding is of considerable interest because accumulating evidence suggests that not only miRNAs can regulate their target genes, but also these target genes may in turn interact with and regulate these specific miRNAs positively or negatively, either at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level (61, 62). In our current study, we established such a relationship between miR-22 and BMP-7/6, whereby we identified BMP-7/6 and BMPR1B as direct targets of miR-22. On the other hand, we provided strong evidence that BMP-7/6 are also positive regulators of miR-22 levels mainly via their direct transcriptional regulation on miR-22 expression. These findings further extend the observations of others and validate the regulatory effects of miRNAs as fine-tuning elements (63), critical in the homeostasis of genes in response to a particular stimulus.

Much attention has recently been paid to canonical BMP signaling, which is known to be largely mediated through activation of Smad1/5/8, whereas TGF-β signaling is mainly mediated by activation of Smad2/3. Both signaling pathways share Smad4 as a common assembly point into a heteromeric signaling complex that translocates into the nucleus to regulate target gene expression in coordination with several other transcription factors (12–17). Cross-talk between TGF-β and BMP signaling is a well known feature of the TGF-β superfamily. BMP-7/6 is a potent antagonistic factor of TGF-β signaling (6), and repression of BMP-7/6 expression leads to increased activation of TGF-β signaling, a key pathogenic factor within renal fibrosis (Fig. 4B). Within our model system, knock-out of miR-22 led to increased BMP-7/6 mRNA and protein levels, while it concomitantly caused blunting of the TGF-β1 induced profibrogenic genes (Fig. 4, A and B). These findings suggest that miR-22 plays a critical role in the cross-talk between TGF-β and BMP-7/6 signaling pathways.

Interestingly, miR-22 itself is reduced under wild type UUO conditions, most likely as a consequence of reduced expression of its key regulators BMP-7/6, and an indirect effect via up-regulation of its negative regulator, TGF-β1 (Fig. 5E). The renoprotective effect of complete knock-out of miR-22 highlights the importance of sustained miR-22 expression to modulate levels of BMP-7/6 and BMPR1B under normal and pathogenic conditions.

A surprising finding of this study was that we identified two conserved BREs within the proximal promoter region of the miR-22 host gene. A reporter gene expression assay indicated that these elements are necessary to enhance miR-22 promoter activity in response to BMP-7/6. These BREs presumably elicit their activation of miR-22 via Smad transcription interactions, likely Smad1/5/8, whose activity is directly related to BMP-mediated signaling. Further studies are needed to determine the role of different Smad complexes on BREs.

In summary, our results provide a significant advance in our current understanding of BMP signaling and regulation in three distinct, yet related aspects: first, our in vitro and in vivo experiments indicate that BMP-7/6 and BMPR1B are direct targets of miR-22; second, our results demonstrate that the targeted deletion of miR-22 significantly attenuates renal fibrosis in an established model of kidney fibrosis; and third, our results reveal the existence of a local regulatory circuit, wherein miR-22 inhibits BMP-7/6 expression, which in turn acts to enhance miR-22 expression in a rapid, time-dependent manner. In this regard, we also characterized the regulatory mechanism of BMP-7/6 on miR-22 by identifying two BREs in the proximal region of miR-22 promoter. Taken together, our findings uncover a miR-22-BMP regulatory relationship in the kidney and suggest that BMP homeostasis is balanced through interactions between miR-22 and TGF-β activation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Ralph C. Nicholas at Dartmouth Medical School for luciferase reporter construct 3.1-luc. We thank the Sequencing Core at Baylor College of Medicine.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1DK091310 and RO1DK078900 (to F. R. D.).

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- miRNA

- microRNA

- BMPR1B

- bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type 1B

- αSMA

- smooth muscle α-actin

- UUO

- unilateral ureteral obstruction

- BRE

- BMP-responsive element

- RT-qPCR

- real time quantitative PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boor P., Ostendorf T., Floege J. (2010) Renal fibrosis. Novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6, 643–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farris A. B., Colvin R. B. (2012) Renal interstitial fibrosis. Mechanisms and evaluation. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 21, 289–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu Y. (2011) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 7, 684–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lan H. Y. (2011) Diverse roles of TGF-β/Smads in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 7, 1056–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morrissey J., Hruska K., Guo G., Wang S., Chen Q., Klahr S. (2002) Bone morphogenetic protein-7 improves renal fibrosis and accelerates the return of renal function. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, S14–S21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zeisberg M., Hanai J., Sugimoto H., Mammoto T., Charytan D., Strutz F., Kalluri R. (2003) BMP-7 counteracts TGF-β1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat. Med. 9, 964–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dendooven A., van Oostrom O., van der Giezen D. M., Leeuwis J. W., Snijckers C., Joles J. A., Robertson E. J., Verhaar M. C., Nguyen T. Q., Goldschmeding R. (2011) Loss of endogenous bone morphogenetic protein-6 aggravates renal fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 1069–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jenkins R. H., Fraser D. J. (2011) BMP-6 emerges as a potential major regulator of fibrosis in the kidney. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 964–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weiskirchen R., Meurer S. K., Gressner O. A., Herrmann J., Borkham-Kamphorst E., Gressner A. M. (2009) BMP-7 as antagonist of organ fibrosis. Front. Biosci. 14, 4992–5012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yan J. D., Yang S., Zhang J., Zhu T. H. (2009) BMP6 reverses TGF-β1-induced changes in HK-2 cells. Implications for the treatment of renal fibrosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30, 994–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boon M. R., van der Horst G., van der Pluijm G., Tamsma J. T., Smit J. W., Rensen P. C. (2011) Bone morphogenetic protein 7. A broad-spectrum growth factor with multiple target therapeutic potency. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 22, 221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blitz I. L., Cho K. W. (2009) Finding partners. How BMPs select their targets. Dev. Dyn. 238, 1321–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bragdon B., Moseychuk O., Saldanha S., King D., Julian J., Nohe A. (2011) Bone morphogenetic proteins. A critical review. Cell Signal. 23, 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cain J. E., Hartwig S., Bertram J. F., Rosenblum N. D. (2008) Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in the developing kidney. Present and future. Differentiation 76, 831–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miyazono K., Maeda S., Imamura T. (2005) BMP receptor signaling. Transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross-talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feng X. H., Derynck R. (2005) Specificity and versatility in TGF-β signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 659–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Massagué J. (2012) TGFβ signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 616–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ambros V. (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bartel D. P. (2009) MicroRNAs. Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Long J., Wang Y., Wang W., Chang B. H., Danesh F. R. (2010) Identification of microRNA-93 as a novel regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor in hyperglycemic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23457–23465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Long J., Wang Y., Wang W., Chang B. H., Danesh F. R. (2011) MicroRNA-29c is a signature microRNA under high glucose conditions that targets Sprouty homolog 1, and its in vivo knockdown prevents progression of diabetic nephropathy. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11837–11848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dey N., Das F., Mariappan M. M., Mandal C. C., Ghosh-Choudhury N., Kasinath B. S., Choudhury G. G. (2011) MicroRNA-21 orchestrates high glucose-induced signals to TOR complex 1, resulting in renal cell pathology in diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 25586–25603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Q., Wang Y., Minto A. W., Wang J., Shi Q., Li X., Quigg R. J. (2008) MicroRNA-377 is up-regulated and can lead to increased fibronectin production in diabetic nephropathy. FASEB J. 22, 4126–4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kato M., Zhang J., Wang M., Lanting L., Yuan H., Rossi J. J., Natarajan R. (2007) MicroRNA-192 in diabetic kidney glomeruli and its function in TGF-β-induced collagen expression via inhibition of E-box repressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3432–3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wei Q., Bhatt K., He H. Z., Mi Q. S., Haase V. H., Dong Z. (2010) Targeted deletion of Dicer from proximal tubules protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 756–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chau B. N., Xin C., Hartner J., Ren S., Castano A. P., Linn G., Li J., Tran P. T., Kaimal V., Huang X., Chang A. N., Li S., Kalra A., Grafals M., Portilla D., MacKenna D. A., Orkin S. H., Duffield J. S. (2012) MicroRNA-21 promotes fibrosis of the kidney by silencing metabolic pathways. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 121ra118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grimwood L., Masterson R. (2009) Propagation and culture of renal fibroblasts. in Methods in Molecular Biology: Kidney Research (Hewitson T. D., Becker G. J., eds) pp. 25–37, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Long J., Matsuura I., He D., Wang G., Shuai K., Liu F. (2003) Repression of Smad transcriptional activity by PIASy, an inhibitor of activated STAT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9791–9796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jørgensen S., Baker A., Møller S., Nielsen B. S. (2010) Robust one-day in situ hybridization protocol for detection of microRNAs in paraffin samples using LNA probes. Methods 52, 375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Várallyay E., Burgyán J., Havelda Z. (2008) MicroRNA detection by Northern blotting using locked nucleic acid probes. Nat. Protoc. 3, 190–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rehmsmeier M., Steffen P., Hochsmann M., Giegerich R. (2004) Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. RNA 10, 1507–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Du M., Roy K. M., Zhong L., Shen Z., Meyers H. E., Nichols R. C. (2006) VEGF gene expression is regulated post-transcriptionally in macrophages. FEBS J. 273, 732–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bar N., Dikstein R. (2010) miR-22 forms a regulatory loop in PTEN/AKT pathway and modulates signaling kinetics. PLoS ONE 5, e10859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loots G. G., Ovcharenko I. (2004) rVISTA 2.0. Evolutionary analysis of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W217–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yu P. B., Hong C. C., Sachidanandan C., Babitt J. L., Deng D. Y., Hoyng S. A., Lin H. Y., Bloch K. D., Peterson R. T. (2008) Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lal A., Thomas M. P., Altschuler G., Navarro F., O'Day E., Li X. L., Concepcion C., Han Y. C., Thiery J., Rajani D. K., Deutsch A., Hofmann O., Ventura A., Hide W., Lieberman J. (2011) Capture of microRNA-bound mRNAs identifies the tumor suppressor miR-34a as a regulator of growth factor signaling. PLoS Genet 7, e1002363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Orom U. A., Lund A. H. (2007) Isolation of microRNA targets using biotinylated synthetic microRNAs. Methods 43, 162–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gurha P., Abreu-Goodger C., Wang T., Ramirez M. O., Drumond A. L., van Dongen S., Chen Y., Bartonicek N., Enright A. J., Lee B., Kelm R. J., Jr., Reddy A. K., Taffet G. E., Bradley A., Wehrens X. H., Entman M. L., Rodriguez A. (2012) Targeted deletion of microRNA-22 promotes stress-induced cardiac dilation and contractile dysfunction. Circulation 125, 2751–2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Satoh M., Kashihara N., Yamasaki Y., Maruyama K., Okamoto K., Maeshima Y., Sugiyama H., Sugaya T., Murakami K., Makino H. (2001) Renal interstitial fibrosis is reduced in angiotensin II type 1a receptor-deficient mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12, 317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang W., Wang Y., Long J., Wang J., Haudek S. B., Overbeek P., Chang B. H., Schumacker P. T., Danesh F. R. (2012) Mitochondrial fission triggered by hyperglycemia is mediated by ROCK1 activation in podocytes and endothelial cells. Cell Metab. 15, 186–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Klahr S., Morrissey J. (2002) Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 283, F861–F875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alvarez-Diaz S., Valle N., Ferrer-Mayorga G., Lombardia L., Herrera M., Dominguez O., Segura M. F., Bonilla F., Hernando E., Munoz A. (2012) MicroRNA-22 is induced by vitamin D and contributes to its antiproliferative, antimigratory and gene regulatory effects in colon cancer cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 2157–2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang W. L., Chatterjee N., Chittur S. V., Welsh J., Tenniswood M. P. (2011) Effects of 1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 and testosterone on miRNA and mRNA expression in LNCaP cells. Mol. Cancer 10, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Delic D., Grosser C., Dkhil M., Al-Quraishy S., Wunderlich F. (2010) Testosterone-induced upregulation of miRNAs in the female mouse liver. Steroids 75, 998–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jian P., Li Z. W., Fang T. Y., Jian W., Zhuan Z., Mei L. X., Yan W. S., Jian N. (2011) Retinoic acid induces HL-60 cell differentiation via the upregulation of miR-663. J. Hematol. Oncol. 4, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. López-Rovira T., Chalaux E., Massagué J., Rosa J. L., Ventura F. (2002) Direct binding of Smad1 and Smad4 to two distinct motifs mediates bone morphogenetic protein-specific transcriptional activation of Id1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3176–3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nakahiro T., Kurooka H., Mori K., Sano K., Yokota Y. (2010) Identification of BMP-responsive elements in the mouse Id2 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 399, 416–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Korchynskyi O., ten Dijke P. (2002) Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4883–4891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Katagiri T., Imada M., Yanai T., Suda T., Takahashi N., Kamijo R. (2002) Identification of a BMP-responsive element in Id1, the gene for inhibition of myogenesis. Genes Cells 7, 949–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shepherd T. G., Thériault B. L., Nachtigal M. W. (2008) Autocrine BMP4 signalling regulates ID3 proto-oncogene expression in human ovarian cancer cells. Gene 414, 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ben-Dov I. Z., Muthukumar T., Morozov P., Mueller F. B., Tuschl T., Suthanthiran M. (2012) MicroRNA sequence profiles of human kidney allografts with or without tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Transplantation 94, 1086–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Glowacki F., Savary G., Gnemmi V., Buob D., Van der Hauwaert C., Lo-Guidice J. M., Bouyé S., Hazzan M., Pottier N., Perrais M., Aubert S., Cauffiez C. (2013) Increased circulating miR-21 levels are associated with kidney fibrosis. PLoS ONE 8, e58014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zarjou A., Yang S., Abraham E., Agarwal A., Liu G. (2011) Identification of a microRNA signature in renal fibrosis. Role of miR-21. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301, F793–F801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhong X., Chung A. C., Chen H. Y., Meng X. M., Lan H. Y. (2011) Smad3-mediated upregulation of miR-21 promotes renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 1668–1681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Oba S., Kumano S., Suzuki E., Nishimatsu H., Takahashi M., Takamori H., Kasuya M., Ogawa Y., Sato K., Kimura K., Homma Y., Hirata Y., Fujita T. (2010) miR-200b precursor can ameliorate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. PLoS ONE 5, e13614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xiong M., Jiang L., Zhou Y., Qiu W., Fang L., Tan R., Wen P., Yang J. (2012) The miR-200 family regulates TGF-β1-induced renal tubular epithelial to mesenchymal transition through Smad pathway by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 302, F369–F379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huang Z. P., Chen J., Seok H. Y., Zhang Z., Kataoka M., Hu X., Wang D. Z. (2013) MicroRNA-22 regulates cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling in response to stress. Circ. Res. 112, 1234–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sayed D., Abdellatif M. (2011) MicroRNAs in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 91, 827–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Rooij E. (2011) The art of microRNA research. Circ. Res. 108, 219–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mendell J. T., Olson E. N. (2012) MicroRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell 148, 1172–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Davis B. N., Hilyard A. C., Lagna G., Hata A. (2008) SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature 454, 56–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Iliopoulos D., Malizos K. N., Oikonomou P., Tsezou A. (2008) Integrative microRNA and proteomic approaches identify novel osteoarthritis genes and their collaborative metabolic and inflammatory networks. PLoS ONE 3, e3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]