Background: O-GlcNAcylation plays important roles in breast cancer metastasis, but the underlying mechanism is not fully known.

Results: Cofilin is O-GlcNAcylated at Ser-108, which is required for its proper localization in invadopodia and is implicated in promoting breast cancer cell invasion.

Conclusion: O-GlcNAcylation plays an important role in fine-tuning the regulation of cofilin.

Significance: These findings reveal the implications of aberrant cofilin O-GlcNAcylation in cancer metastasis.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Cell Invasion, Cell Motility, Cofilin, O-GlcNAcylation, Invadopodia, OGT

Abstract

O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification that regulates a broad range of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins and is emerging as a key regulator of various biological processes. Previous studies have shown that increased levels of global O-GlcNAcylation and O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) are linked to the incidence of metastasis in breast cancer patients, but the molecular basis behind this is not fully known. In this study, we have determined that the actin-binding protein cofilin is O-GlcNAcylated by OGT and mainly, if not completely, mediates OGT modulation of cell mobility. O-GlcNAcylation at Ser-108 of cofilin is required for its proper localization in invadopodia at the leading edge of breast cancer cells during three-dimensional cell invasion. Loss of O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin leads to destabilization of invadopodia and impairs cell invasion, although the actin-severing activity or lamellipodial localization is not affected. Our study provides insights into the mechanism of post-translational modification in fine-tuning the regulation of cofilin activity and suggests its important implications in cancer metastasis.

Introduction

Protein glycosylation with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc)4 is a reversible post-translational modification occurring on serine or threonine residues of a variety of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins (1). O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) catalyzes the attachment of O-GlcNAc to proteins, whereas O-GlcNAcase is responsible for sugar removal (2). O-GlcNAcylation has emerged lately as a key regulator of various cellular processes, such as signal transduction, transcription, and proteasomal degradation (3). Intriguingly, it has been observed that O-GlcNAcylation is particularly abundant in cytoskeletal proteins or their regulators, implying an important role in modulating cell motility-driven processes, such as cell migration (1, 4, 5).

The actin-binding protein cofilin is a major regulator of actin dynamics that drives cell motility (6–8). Activation of cofilin starts with an increase in actin-severing activity, which in turn increases the number of free barbed ends to initiate actin polymerization. In invasive cells, cofilin is locally enriched and activated in two subcellular compartments known as lamellipodia and invadopodia, where cofilin disassembles filamentous actin (F-actin) from the rear part of the actin network to recycle monomeric G-actins to the front for further rounds of polymerization (9). Meanwhile, the F-actin-severing activity of cofilin promotes actin filament elongation by increasing the number of free barbed ends that are used as new nucleation sites for filament growth (10).

The precise regulatory control of cofilin activity is critical to maintain the normal physiology of the cell, whereas overactivated cofilin activity has been linked to pathological events, such as tumor metastasis (11–13). It is known that the severing activity of cofilin is tightly regulated via multiple mechanisms, which involve binding of cofilin to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) at lamellipodia or cortactin at invadopodia (14, 15), as well as covalent modification through phosphorylation (16, 17). Among these, phosphorylation at Ser-3, catalyzed by LIM and TES family kinases (18, 19), is known to play a fundamental role in regulating cofilin activity. Constitutive phosphorylation abolishes cofilin binding to actin and in turn fails to sever or depolymerize F-actin, resulting in decreased cell motility. Removal of phosphorylation at Ser-3 upon stimulation activates actin-severing activity and leads to dynamic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, which is required for directed cell migration and chemotaxis. Notably, LIMK1 (LIM kinase 1) overexpression, which leads to inhibition of cofilin activity (20, 21), is correlated with increased invasion (22, 23). In additional, lines of evidence from global proteomic analysis have suggested that post-translational modifications of cofilin are likely not limited to phosphorylation. Other forms of modifications, such as O-GlcNAcylation (24, 25), appear to occur as well, suggesting a more sophisticated regulatory network of cofilin.

In this study, we shows that cofilin is O-GlcNAcylated by OGT and that cofilin mediates OGT-associated cell mobility changes. O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin at Ser-108 is required for its proper function in invadopodia. Our findings provide insights into the regulatory mechanisms of cofilin function and reveal the implications of aberrant cofilin O-GlcNAcylation in cancer malignancies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in the appropriate medium as suggested by the manufacturer. Rat mammary adenocarcinoma MTLn3 cells (kindly provided by Dr. John S. Condeelis, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) were grown in α-minimal essential medium containing 5% FBS. Transient transfection for MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For MTLn3 cells, transfection was terminated after 1 h by replacement with α-minimal essential medium containing 5% FBS. In the case of cotransfection, each plasmid was used at a 1:1 ratio.

Reagents and Antibodies

Anti-cofilin (catalog no. 3312), anti-phospho-cofilin Ser-3 (catalog no. 3311), and anti-actin (catalog no. 4967) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling. Anti-FLAG antibody (sc-807) and Protein A/G PLUS-agarose were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-cortactin antibody (catalog no. 2067-1) was obtained from Epitomics. Anti-PIP2 antibody (ab11039) was obtained from Abcam. Anti-O-GlcNAc antibody (CTD110.6) was from Covance. Anti-mouse IgM-agarose and dimethyl pimelimidate were from Sigma. Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (catalog no. A2220) was obtained from Sigma. cOmplete protease inhibitor mixture and phosphatase inhibitor mixture were obtained from Roche Applied Science.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (20 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 137 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 0.25% deoxycholate, and cOmplete protease inhibitor mixture; Beyotime). Lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce). Immunoprecipitations were performed by incubating the lysate with the appropriate antibody for 6 h at 4 °C. For detection of endogenous protein, immunoprecipitation was followed by incubation with Protein A/G PLUS-agarose for another 4 h. For FLAG immunoprecipitation, the lysate was incubated with anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma) for 2 h. For CTD110.6 immunoprecipitation, the lysate was incubated with agarose covalently cross-linked to CTD110.6, in which anti-O-GlcNAc antibody CTD110.6 was covalently immobilized onto anti-IgM-agarose as described previously (26). After washing four times with lysis buffer, the immune complex was resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was carried out using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG and the ECL system for detection.

Plasmids

Vectors pcDNA3.1-myc-His(A) and pBAD-His(A) were obtained from Invitrogen, and pEGFP-N1 and pDsRed-N1 was obtained from Clontech. Cofilin mutants were generated using a Muta-directTM site-directed mutagenesis kit (Beijing SBS Genetech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The primers for generating cofilin siRNA-resistant mutations were GAT GGT GTC ATC AAA GTC TTT AAC GAC ATG AAG GTG CG (sense) and CGC ACC TTC ATG TCG TTA AAG ACT TTG ATG ACA CCA TC (antisense).

RNA Interference

Shanghai GenePharma (Shanghai, China) synthesized siRNA sequences specifically targeting cofilin (sense, AAG GUG UUC AAU GAC AUG AAA TT; and antisense, UUU CAU GUC AUU GAA CAC CUU TT) and OGT (sense, GCG CAC UGU UCA UGG AUU ATT; and antisense, UAA UCC AUG AAC AGU GCG CTT).

Transwell Cell Migration and Invasion Assay

Cells were trypsinized and seeded into Transwell inserts in a normalized amount. For invasion assay, the inserts were precoated with diluted Matrigel at a final concentration of 0.125 μg/μl. After 12 h, the upper side of the membrane was rubbed with a cotton swap, and the migrated/invaded cells in the basal side insert were fixed and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Cells that migrated to the bottom side of the filter were counted in 10 fields/well at ×200 magnification. The experiments were repeated three times.

Time-lapse Video Microscopy

Time-lapse imaging experiments were performed using a fully automated Olympus FV1000 system. Image were acquired using FV10-ASW 2.1 imaging software. Time-lapse images were recorded at 15- or 25-s time intervals. NIH ImageJ2x 2.1.4.7 software and the MTrackJ plug-in were used to track cell paths. The Chemotaxis and Migration Tool Version 1.01 plug-in (ibidi Integrated BioDiagnostics) was used for plotting cell tracks and for velocity and distance measurements. Movies were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS3 software.

F-actin and G-actin Fractionation

Cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in F-actin stabilizing buffer (50 mm Pipes (pH 6.9), 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EGTA, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.001% antifoam, protease inhibitor mixture, and 1 mm ATP) by homogenizing with a 26.5-gauge syringe. The lysates were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 37 °C. The supernatants (G-actin) were collected and placed on ice. The pellets (F-actin) were resuspended in the same volume as the supernatant of distilled H2O containing 2 mm cytochalasin D and incubated on ice for 1 h. Equal amounts of G-actin and F-actin were subjected to immunoblot assay with anti-actin antibody. The intensity of bands was quantified with ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

Three independent experiments were performed, and data are presented as means ± S.D. Student's t test was performed, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

O-GlcNAcylation of Cofilin Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Mobility

It has recently been reported that increased levels of global GlcNAcylation and OGT are closely linked to the metastasis occurrence of breast cancer (27), suggesting that O-GlcNAcylation may play an important role in modulating the proteins associated with cell mobility. In agreement with this evidence, O-GlcNAcylation is known to be particularly abundant on structural or regulatory proteins of the cytoskeleton, the fundamental players in cell motility (1, 4).

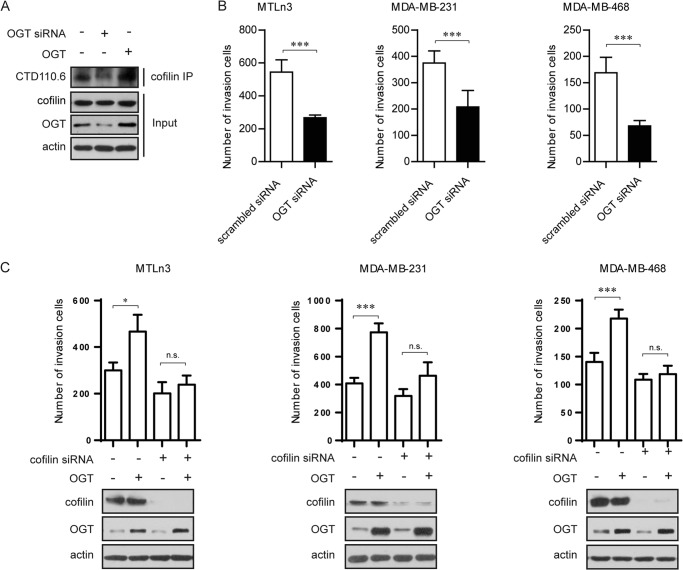

To test whether cofilin is indeed O-GlcNAcylated in breast cancer cells as revealed by proteomic evidence (27), we examined the O-GlcNAc modification of cofilin by specifically enriching endogenous cofilin, followed by detection with pan-O-GlcNAcylation antibody CTD110.6. An apparent band of O-GlcNAcylation was detected upon cofilin enrichment. Importantly, OGT overexpression increased the level of O-GlcNAcylation. Likewise, disruption of OGT using siRNA largely decreased O-GlcNAcylated cofilin (Fig. 1A). These data suggest that cofilin is O-GlcNAcylated in breast cancer cells.

FIGURE 1.

OGT promotes breast cancer cell invasion in a cofilin-dependent manner. A, cofilin is O-GlcNAcylated in breast cancer cells. MTLn3 cells were transfected with OGT siRNA or pcDNA3.1-OGT for 48 h. Immunoprecipitates (IP) were obtained from cell extracts using the anti-cofilin antibody and were analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated antibodies. B, OGT disruption leads to impaired cell invasion. MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MTLn3 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (control) or OGT siRNA, and cell invasion was assessed using a Transwell assay. Cells that migrated into the lower chamber were counted. Data are means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. ***, p < 0.001. C, cofilin knockdown reverses OGT-promoted cell invasion. MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MTLn3 cells treated with control siRNA or cofilin siRNA were further transfected with a vector plasmid or pcDNA3.1-OGT (OGT). After 48 h, cell invasion was assessed as described for B. Data are shown as means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; n.s., not significant.

We then asked whether the observed association between OGT expression and breast cancer metastasis is mediated by cofilin. To this end, MTLn3 cells and two human breast cancer cell lines were transfected with ectopic human OGT, and cell mobility was assessed using Transwell cell invasion assay. Overexpression of OGT considerably increased cell mobility in all three cell lines. Most importantly, silencing of cofilin using siRNA in OGT-overexpressing cells almost entirely reversed OGT-enhanced cell mobility (Fig. 1, B and C). These results suggest that OGT-promoted breast cancer cell motility may involve modulation of cofilin O-GlcNAcylation.

Cofilin Is O-GlcNAcylated at Ser-108

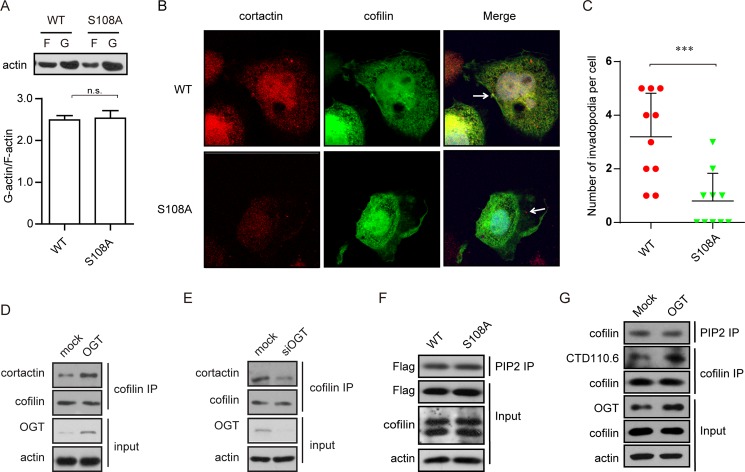

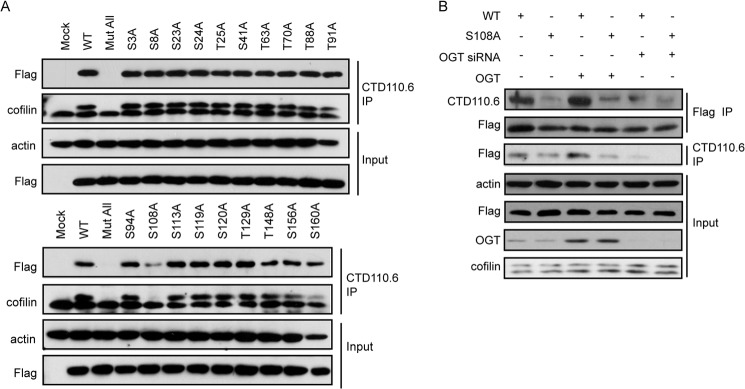

O-GlcNAcylation is known to occur at Thr and Ser residues. Cofilin consists of 167 amino acids, including 19 Ser/Thr residues. To identify O-GlcNAcylated sites on cofilin, we constructed FLAG-tagged cofilin in which all Ser/Thr sites were individually replaced with Ala to abolish O-GlcNAcylation. In MTLn3 cells ectopically expressing cofilin mutants, global O-GlcNAcylated proteins were immunoprecipitated with antibody CTD110.6, and the presence of cofilin in the immunoprecipitates was determined using anti-FLAG or anti-cofilin antibodies. The results show that a mutant with all Ser/Thr residues replaced with Ala completely abolished the cofilin signal in the immunoprecipitates, suggesting that all of the cofilin detected in the precipitates was O-GlcNAcylated, ruling out nonspecific detections. Among a series of mutants bearing single-site mutations, S108A was the only one that considerably reduced cofilin O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 2A), suggesting that Ser-108 is the major site where O-GlcNAcylation occurs on cofilin.

FIGURE 2.

O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin occurs at Ser-108. A, cofilin alanine-scanning mutagenesis. MTLn3 cells were transfected with empty vector (Mock) or the indicated FLAG-tagged cofilin mutants in pcDNA3.1 for 48 h. A plasmid with all Ser and Thr residues substituted with Ala (Mut All) was used as a negative control. O-GlcNAcylated proteins were enriched using anti-O-GlcNAc antibody, and the presence of cofilin was analyzed by immunoblotting with FLAG or cofilin. B, MTLn3 cells were cotransfected with FLAG-tagged wild-type or S108A mutant cofilin along with OGT siRNA/plasmid for 48 h. Cofilin was enriched using FLAG M2 beads, and the O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin was detected using antibody CTD110.6. IP, immunoprecipitate.

To further confirm this finding, OGT was cotransfected with wild-type or S108A mutant cofilin. The impact of OGT overexpression on the O-GlcNAcylation of both constructs was assessed. Overexpression of OGT apparently increased O-GlcNAcylation in wild-type cofilin, which was largely blocked by OGT siRNA, but barely affected the S108A mutant. These results suggest that Ser-108 is the major O-GlcNAcylation site on cofilin (Fig. 2B).

O-GlcNAcylation at Ser-108 Facilities Cofilin Localization in Invadopodia

We next investigated the biological significance of the GlcNAcylation of cofilin. Cofilin is known to regulate cell mobility via modulating actin polymerization, which requires its actin-binding and actin-severing activities. We first assessed actin polymerization by measuring the ratio of G-actin and F-actin. The results show that in cells overexpressing wild-type or S108A cofilin, impaired O-GlcNAcylation at Ser-108 did not affect the G-actin/F-actin ratio (Fig. 3A), implying that O-GlcNAcylation has no impact on actin-binding and actin-severing activities.

FIGURE 3.

O-GlcNAcylation at Ser-108 facilities cofilin localization in invadopodia. A, MTLn3 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged wild-type or S108A mutant cofilin for 48 h. Cell extracts were extracted for F-actin (F)/G-actin (G) fractionation assay. n.s., not significant. B, MTLn3 cells transfected with EGFP-tagged wild-type or S108A mutant cofilin were starved overnight and then stimulated with EGF for 5 min and subjected to cell immunofluorescence for cortactin. C, quantification of the number of invadopodium precursors/cell that contain co-localization of cofilin and cortactin. Data are represented as means ± S.D. (n = 10). ***, p < 0.001. D and E, MTLn3 cells were transfected with OGT siRNA (siOGT) or the indicated plasmids. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was conducted using anti-cofilin antibody, followed by immunoblot analysis for the presence of cortactin. F, cell extracts as described for A were immunoprecipitated using anti-PIP2 antibody, followed by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody. The G-actin/F-actin ratio was calculated based on the intensity of bands, which was quantified by ImageJ software. G, MTLn3 cells transfected with OGT or empty vector (Mock) for 48 h were treated with EGF for 5 min. Immunoprecipitates with anti-PIP2 or anti-cofilin antibody were subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

In invasive cells, cofilin is locally enriched and activated in lamellipodia and invadopodia. The intracellular localization of cofilin is crucial for its enabled cell motility change. Immunofluorescence staining was used to monitor the localization of cofilin in MTLn3 cells upon EGF stimulation. Cofilin was visualized via conjugation to EGFP. MTLn3 cells transfected with GFP-tagged wild-type or mutant cofilin were stimulated with EGF following overnight serum starvation. As shown in Fig. 3B, EGF treatment resulted in dot-like enrichment of wild-type cofilin clustered with cortactin, an invadopodium marker, suggesting a proper activation in invadopodia. In contrast, the S108A mutant, with impaired O-GlcNAcylation, exhibited a defect in localizing in invadopodia (Fig. 3, B and C). Overexpression of OGT in MTLn3 cells, which caused an increase in O-GlcNAcylated cofilin, consistently increased its association with cortactin (Fig. 3D), whereas disruption of OGT using siRNA led to a reduced association between cofilin and cortactin (Fig. 3E). Meanwhile, association of cofilin with PIP2, a cofactor regulating cofilin activation, was not affected (Fig. 3, F and G). These data suggest that O-GlcNAcylation is required for activation of cofilin via facilitating its localization in invadopodia.

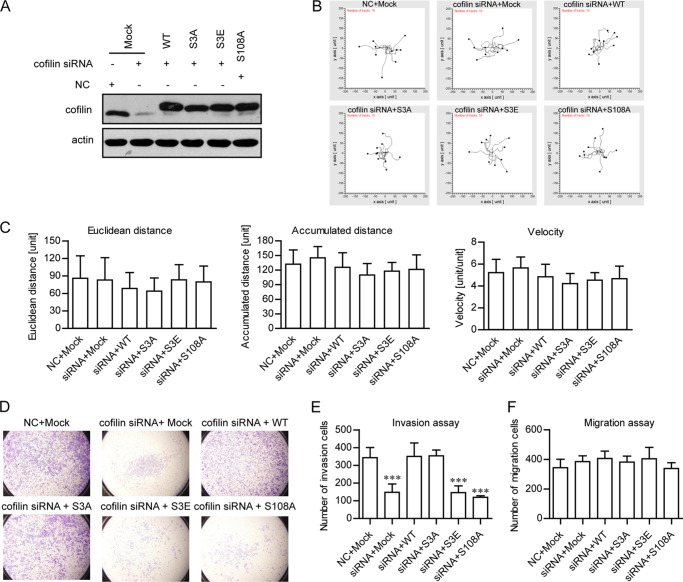

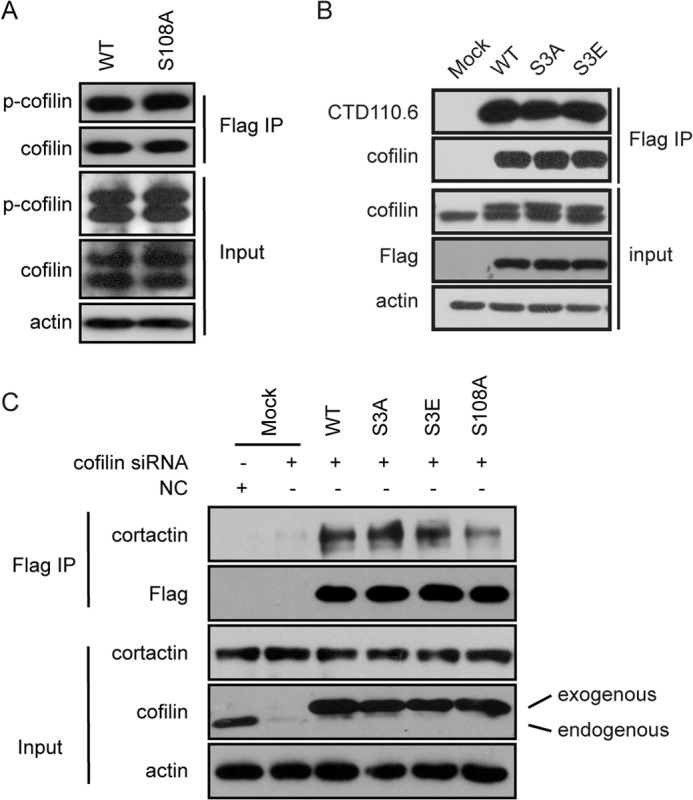

O-GlcNAcylation at Ser-108 Is Independent of Phosphorylation at Ser-3

The activity of cofilin is known to be fundamentally regulated by its phosphorylation at Ser-3 (8). Dephosphorylation of Ser-3 marks the initiation of its local activation in lamellipodia and invadopodia and drives a change in actin dynamics. Mounting evidence has suggested that O-GlcNAcylation may have a reciprocal relationship with O-phosphorylation (2, 26, 28). We then asked whether the defective invadopodium localization of S108A was simply due to impaired Ser-3 phosphorylation. MTLn3 cells transfected with wild-type or S108A mutant cofilin were stimulated with EGF for 5 min. Exogenous cofilin was immunoprecipitated, and the phosphorylation of cofilin in the immunoprecipitates was detected. As shown in Fig. 4A, wild-type cofilin and the S108A mutant were similarly phosphorylated at Ser-3, suggesting that O-GlcNAcylation does not affect the phosphorylation of cofilin. In contrast, O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin occurred regardless of the status of phosphorylation at Ser-3, as suggested by a comparable level of O-GlcNAcylation in the phosphomimetic mutant S3E and the phospho-dead mutant S3A (Fig. 4B). It appeared to us that the O-GlcNAcylation and O-phosphorylation of cofilin occur independently.

FIGURE 4.

O-GlcNAcylation at Ser-108 is independent of phosphorylation at Ser-3. A, MTLn3 cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs or plasmids were stimulated with EGF for 5 min. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was conducted using anti-FLAG antibody, followed by immunoblot analysis for the presence of cortactin. B, MTLn3 cells were transfected with OGT siRNA or the indicated plasmids. Immunoprecipitation was conducted using anti-cofilin antibody, followed by immunoblot analysis for the presence of cortactin. C, MTLn3 cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs or plasmids were stimulated with EGF for 5 min. Immunoprecipitation was conducted using anti-FLAG antibody, followed by immunoblot analysis for the presence of cortactin. NC, negative control.

Indeed, the S3E mutant, which lost activity due to defective binding to F-actin (8), similarly associated with cortactin compared with wild-type cofilin, implying a competent ability in localizing in invadopodia. Likewise, the combination of the constitutively active S3A mutant and the inactive S108A mutant exhibited similar defects as the S108A single mutant in the clustering in invadopodia over time in response to EGF induction (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that O-GlcNAcylation modulates the function of cofilin independent of phosphorylation at Ser-3.

O-GlcNAcylation of Cofilin at Ser-108 Is Important for Cell Invasion

The ability to form invadopodia is linked to the invasive and metastatic properties of cancer cells. The presence of cofilin in invadopodia is particularly required for the matrix degradation during cell invasion (27). To evaluate the impact of O-GlcNAcylation on the cofilin-induced metastatic properties of breast cancer cells, we compared the capability of cells bearing wild-type cofilin and the S108A mutant in two-dimensional and three-dimensional migration. Two-dimensional migration reflects mainly the capacity for lamellipodium-dependent chemotaxis, whereas three-dimensional migration assay supplemented with Matrigel shows the capability for invadopodium-dependent invasion (29). Given that cofilin is highly abundant in cells and that only a small proportion of cofilin located at the leading edge is functional via its actin-severing activity (30), siRNA against cofilin was used prior to introduction of mutant variants to exclude the influence of endogenous cofilin (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Impaired O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin leads to defects in cell invasion. MTLn3 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (negative control (NC)) or cofilin siRNA for 24 h were further transfected with siRNA-resistant FLAG-tagged wild-type cofilin or empty vector (Mock) for 48 h. A, cell extracts were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. B, multiple tracks of individual cells were recorded upon EGF stimulation for 40 min. The starting points of the recorded cell tracks were artificially set to the same origin. The experiments were repeated three times. A representative result is shown. C, the Euclidean distances, accumulated distances, and velocities of individual cells were calculated from the recorded tracks. Data are shown as means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Cells were allowed to migrate either across non-treated Transwell inserts (F) or across a Matrigel layer on top of a Transwell insert (D and E) in the presence of EGF in the lower compartment. The percentages of migrated cells were determined. The means ± S.E. of three independent experiments are shown. ***, p < 0.001.

Indeed, when cells transfected with wild-type or S108A mutant cofilin were allowed to migrate either on a two-dimensional surface or in a three-dimensional environment, we did not observe the obvious defect of the S108A mutant. Specifically, the two-dimensional position changes were stimulated by EGF, recorded, and imaged. Centroid plot analysis, which traced the positions of the centroids of cells at consecutive time intervals, indicated that the cells with wild-type or S108A mutant cofilin behaved similarly in terms of speed and directionality upon EGF stimulation (Fig. 5, B and C). Likewise, in a chemotactic three-dimensional transmigration assay, cells transfected with S108A showed similar behavior compared with the wild-type cells.

Furthermore, we examined the impact of the S108A mutant on the invasive ability of cells using the Matrigel Transwell assay, in which migrating to the low chamber requires degradation of the Matrigel layer. The S108A mutant cells showed an apparent defect in invading through the Matrigel layer compared with the wild-type cells (Fig. 5, D–F). These results support the role of O-GlcNAcylated cofilin in invadopodia and imply the importance of this modification in fine-tuning cell invasion.

DISCUSSION

Cell invasion is a multistep and tightly regulated process that requires the cooperation of a variety of intracellular and extracellular regulators (31). As an actin-severing protein, the critical role of cofilin in regulating actin dynamics and driving cell motility has been well recognized. Meanwhile, increasing evidence has suggested that multilevel mechanisms are involved in regulating the function of cofilin. Here, we have discovered a novel regulatory mechanism of cofilin by a type of post-translational modification, namely O-GlcNAcylation. We have shown that O-GlcNAcylation at Ser-108 is important for the subcellular localization of cofilin in invadopodia. Impaired O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin results in defects in invasive migration that particularly requires matrix degradation. Importantly, our evidence implies that deregulated O-GlcNAcylation of cofilin may be linked to metastasis of breast cancer.

In addition to O-GlcNAcylation, cofilin has been reported to be phosphorylated at several sites. Among them, phosphorylation at Ser-3 is a primary regulatory mechanism that shuts off cofilin activity, whereas phosphorylation at Tyr-68 is linked to the degradation of cofilin. Given that O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation both occur at serine and threonine residues, the two modifications often compete for occupancy at the same site. In other cases, O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation at proximal residues of the same protein affect each other via spatial interactions, such as p53 and Akt (26, 28). Indeed, the reciprocal relationship between O-GlcNAcylation and O-phosphorylation gives rise to the most acceptable “yin-yang hypothesis” for understanding the function of O-GlcNAcylation (2, 3). However, in the case of cofilin, the impact of O-phosphorylation seems independent of phosphorylation at Ser-3 (32, 33). It appears to us that phosphorylation at Ser-3 plays a fundamental role in maintaining cofilin in an inactive stage. Stimuli such as EGF activate cofilin by locally dephosphorylating at Ser-3, whereas the full activation in invadopodia requires further O-GlcNAcylation. Our results suggest a more sophisticated regulatory mechanism involved in the spatial and temporal regulation of cofilin.

The high spatial and temporal precision is particularly important for a protein like cofilin, which is highly abundant and ubiquitously distributed in cells but functions locally in initiating protrusion and determining cell direction (8, 14, 30). Hence, the general expression or modification status may not be sufficient to ensure the rapid response at the right location to allow instant cell motility changes. Thus far, the primary on/off regulation of cofilin can be grouped into two broad categories. Phosphorylation represents a more general regulatory mechanism that attenuates the ability of cofilin to bind to actin regardless of its subcellular locations. Compared with phosphorylation, binding to either PIP2 or cortactin is closely relevant to the subcellular compartment: PIP2 in lamellipodia and cortactin in invadopodia. Apart from these two primary on/off mechanisms, other mechanisms have been shown to contribute to the amplitude of cofilin activity resulting from the turning on/off of cofilin, including regulation by pH; scaffolding activators such as cyclase-associated protein, Aip1, β-arrestin, and coronin; and modifications such as O-GlcNAcylation described in this study (11). O-GlcNAcylation features a rapid and dynamic modification in signaling transduction. Previous studies using a membrane sensor showed highly localized O-GlcNAc activity at the edges of the membrane in response to serum stimulation (34, 35). The results from this study indicate the co-localization of OGT and cofilin in invadopodia (data not shown). These evidences support the model that, as a secondary regulation, O-GlcNAcylation functions to fine-tune the primary on/off regulation by cortactin binding in invadopodia.

Such a complex regulatory network makes the precise function of cofilin possible. Loss of O-GlcNAcylation does not affect the severing activity or PIP2-binding ability of cofilin. S108A mutant cofilin is normally located in lamellipodia, which is important for cell migration in chemotaxis. Loss of O-GlcNAcylation specifically impairs its localization in invadopodia. As a result, O-GlcNAcylation is required only for three-dimensional cell invasion that involves matrix degradation. In summary, we herein reported a new regulatory mechanism of cofilin by O-GlcNAcylation, which provides insights into the precise regulation of cofilin for its allowed cell motility changes and implies the involvement of aberrant O-GlcNAcylation in cancer metastasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wenlong Huang (China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China) for insightful discussions and Dr. John S. Condeelis for kindly providing MTLn3 cells.

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China for Innovation Research Group Grant 81021062 and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 91229204 and 81302791.

- O-GlcNAc

- O-linked N-acetylglucosamine

- OGT

- O-GlcNAc transferase

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zachara N. E., Hart G. W. (2006) Cell signaling, the essential role of O-GlcNAc! Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 599–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hart G. W., Housley M. P., Slawson C. (2007) Cycling of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature 446, 1017–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slawson C., Hart G. W. (2011) O-GlcNAc signalling: implications for cancer cell biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 678–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Love D. C., Hanover J. A. (2005) The hexosamine signaling pathway: deciphering the “O-GlcNAc code”. Sci. STKE 2005, re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zachara N. E., Hart G. W. (2004) O-GlcNAc a sensor of cellular state: the role of nucleocytoplasmic glycosylation in modulating cellular function in response to nutrition and stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1673, 13–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sidani M., Wessels D., Mouneimne G., Ghosh M., Goswami S., Sarmiento C., Wang W., Kuhl S., El-Sibai M., Backer J. M., Eddy R., Soll D., Condeelis J. (2007) Cofilin determines the migration behavior and turning frequency of metastatic cancer cells. J. Cell Biol. 179, 777–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kiuchi T., Ohashi K., Kurita S., Mizuno K. (2007) Cofilin promotes stimulus-induced lamellipodium formation by generating an abundant supply of actin monomers. J. Cell Biol. 177, 465–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghosh M. (2004) Cofilin promotes actin polymerization and defines the direction of cell motility. Science 304, 743–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlier M. F., Laurent V., Santolini J., Melki R., Didry D., Xia G. X., Hong Y., Chua N. H., Pantaloni D. (1997) Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 136, 1307–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ichetovkin I., Grant W., Condeelis J. (2002) Cofilin produces newly polymerized actin filaments that are preferred for dendritic nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Curr. Biol. 12, 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang W., Eddy R., Condeelis J. (2007) The cofilin pathway in breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 429–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bamburg J. R., Wiggan O. P. (2002) ADF/cofilin and actin dynamics in disease. Trends Cell Biol. 12, 598–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang L.-h., Xiang J., Yan M., Zhang Y., Zhao Y., Yue C.-f., Xu J., Zheng F.-m., Chen J.-n., Kang Z., Chen T.-s., Xing D., Liu Q. (2010) The mitotic kinase Aurora-A induces mammary cell migration and breast cancer metastasis by activating the cofilin-F-actin pathway. Cancer Res. 70, 9118–9128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Rheenen J., Song X., van Roosmalen W., Cammer M., Chen X., Desmarais V., Yip S. C., Backer J. M., Eddy R. J., Condeelis J. S. (2007) EGF-induced PIP2 hydrolysis releases and activates cofilin locally in carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 179, 1247–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oser M., Yamaguchi H., Mader C. C., Bravo-Cordero J. J., Arias M., Chen X., Desmarais V., van Rheenen J., Koleske A. J., Condeelis J. (2009) Cortactin regulates cofilin and N-WASp activities to control the stages of invadopodium assembly and maturation. J. Cell Biol. 186, 571–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mizuno K. (2013) Signaling mechanisms and functional roles of cofilin phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Cell. Signal. 25, 457–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frantz C., Barreiro G., Dominguez L., Chen X., Eddy R., Condeelis J., Kelly M. J. S., Jacobson M. P., Barber D. L. (2008) Cofilin is a pH sensor for actin free barbed end formation: role of phosphoinositide binding. J. Cell Biol. 183, 865–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meng Y. (2004) Regulation of ADF/cofilin phosphorylation and synaptic function by LIM-kinase. Neuropharmacology 47, 746–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sarmiere P. D., Bamburg J. R. (2004) Regulation of the neuronal actin cytoskeleton by ADF/cofilin. J. Neurobiol. 58, 103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li R., Doherty J., Antonipillai J., Chen S., Devlin M., Visser K., Baell J., Street I., Anderson R. L., Bernard O. (2013) LIM kinase inhibition reduces breast cancer growth and invasiveness but systemic inhibition does not reduce metastasis in mice. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 30, 483–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McConnell B. V., Koto K., Gutierrez-Hartmann A. (2011) Nuclear and cytoplasmic LIMK1 enhances human breast cancer progression. Mol. Cancer 10, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davila M. (2003) LIM kinase 1 is essential for the invasive growth of prostate epithelial cells. Implications in prostate cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36868–36875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang W. (2006) The activity status of cofilin is directly related to invasion, intravasation, and metastasis of mammary tumors. J. Cell Biol. 173, 395–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoo Y., Ho H. J., Wang C., Guan J. L. (2010) Tyrosine phosphorylation of cofilin at Y68 by v-Src leads to its degradation through ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Oncogene 29, 263–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wells L. (2002) Mapping sites of O-GlcNAc modification using affinity tags for serine and threonine post-translational modifications. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang S., Huang X., Sun D., Xin X., Pan Q., Peng S., Liang Z., Luo C., Yang Y., Jiang H., Huang M., Chai W., Ding J., Geng M. (2012) Extensive crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation regulates Akt signaling. PLoS ONE 7, e37427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gu Y., Mi W., Ge Y., Liu H., Fan Q., Han C., Yang J., Han F., Lu X., Yu W. (2010) GlcNAcylation plays an essential role in breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 70, 6344–6351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang W. H., Kim J. E., Nam H. W., Ju J. W., Kim H. S., Kim Y. S., Cho J. W. (2006) Modification of p53 with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine regulates p53 activity and stability. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1074–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klemke M., Kramer E., Konstandin M. H., Wabnitz G. H., Samstag Y. (2010) An MEK-cofilin signalling module controls migration of human T cells in 3D but not 2D environments. EMBO J. 29, 2915–2929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mouneimne G., DesMarais V., Sidani M., Scemes E., Wang W., Song X., Eddy R., Condeelis J. (2006) Spatial and temporal control of cofilin activity is required for directional sensing during chemotaxis. Curr. Biol. 16, 2193–2205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gupta G. P., Massagué J. (2006) Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell 127, 679–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Z., Udeshi N. D., Slawson C., Compton P. D., Sakabe K., Cheung W. D., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Hart G. W. (2010) Extensive crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation regulates cytokinesis. Sci. Signal. 3, ra2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Z., Gucek M., Hart G. W. (2008) Cross-talk between GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in response to globally elevated O-GlcNAc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13793–13798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang X., Ongusaha P. P., Miles P. D., Havstad J. C., Zhang F., So W. V., Kudlow J. E., Michell R. H., Olefsky J. M., Field S. J., Evans R. M. (2008) Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature 451, 964–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carrillo L. D., Froemming J. A., Mahal L. K. (2011) Targeted in vivo O-GlcNAc sensors reveal discrete compartment-specific dynamics during signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 6650–6658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]