Background: The microRNA that regulates the expression of CAGE is unknown.

Results: miR-200b and CAGE exert opposite regulations on the response to microtubule-targeting drugs, invasion, tumorigenic potential, and angiogenic potential.

Conclusion: CAGE and miR-200b form a feedback regulatory loop.

Significance: miR-200b may be a target for the treatment of CAGE-driven cancers.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Anticancer Drug, Cancer Biology, Invasion, MicroRNA, Angiogenic Potential, CAGE, Feedback Regulatory Loop, Tumorigenic Potential, miR-200b

Abstract

Cancer/testis antigen cancer-associated gene (CAGE) is known to be involved in various cellular processes, such as proliferation, cell motility, and anti-cancer drug resistance. However, the mechanism of the expression regulation of CAGE remains unknown. Target scan analysis predicted the binding of microRNA-200b (miR-200b) to CAGE promoter sequences. The expression of CAGE showed an inverse relationship with miR-200b in various cancer cell lines. miR-200b was shown to bind to the 3′-UTR of CAGE and to regulate the expression of CAGE at the transcriptional level. miR-200b also enhanced the sensitivities to microtubule-targeting drugs in vitro. miR-200b and CAGE showed opposite regulations on invasion potential and responses to microtubule-targeting drugs. Xenograft experiments showed that miR-200b had negative effects on the tumorigenic and metastatic potential of cancer cells. The effect of miR-200b on metastatic potential involved the expression regulation of CAGE by miR-200b. miR-200b decreased the tumorigenic potential of a cancer cell line resistant to microtubule-targeting drugs in a manner associated with the down-regulation of CAGE. ChIP assays showed the direct regulation of miR-200b by CAGE. CAGE enhanced the invasion potential of a cancer cell line stably expressing miR-200b. miR-200b exerted a negative regulation on tumor-induced angiogenesis. The down-regulation of CAGE led to the decreased expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, a TGFβ-responsive protein involved in angiogenesis, and VEGF. CAGE mediated tumor-induced angiogenesis and was necessary for VEGF-promoted angiogenesis. Human recombinant CAGE protein displayed angiogenic potential. Thus, miR-200b and CAGE form a feedback regulatory loop and regulate the response to microtubule-targeting drugs, as well as the invasion, tumorigenic potential, and angiogenic potential.

Introduction

Cancer/testis antigen CAGE3 was identified by serological analysis of the recombinant cDNA expression library using the sera of patients with gastric cancers (1). CAGE contains the DEAD box domain and encodes a putative protein of 630 amino acids with possible helicase activity (1). CAGE is expressed in a variety of cancers but not in normal tissues except for testis (1). This makes CAGE a valuable target of antitumor immunotherapy. CAGE enhances cellular proliferation, and CAGE-derived peptides induce cytolytic T lymphocyte activity (2). CD8+ T cells presensitized with these peptides display cytotoxic effects against cancer cells expressing CAGE (2).

CAGE is present in the sera of patients with gastric cancers (1), endometrial cancers (3), and patients with hematological malignancies (4). The methylation status of the CpG sites of CAGE determines its expression (5). The hypomethylation of CAGE precedes the development of gastric cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (5). This suggests that the high frequencies of hypomethylation of CAGE in various cancers would be valuable as a cancer diagnostic marker. These reports suggest that CAGE can be a valuable marker for the detection of cancers.

The expression of CAGE is increased in cancer cell lines resistant to microtubule-targeting drugs (6). CAGE, through interaction with HDAC2, represses the expression of p53 and confers resistance to microtubule-targeting drugs (5). CAGE possesses oncogenic potential and promotes cell cycle progression by inducing AP-1- and E2F-dependent expression of cyclins D1 and E (7).

miRNAs are a class of endogenous, 18–25-nucleotide, noncoding RNAs that regulate the expression of target genes either through translational inhibition or destabilization of mRNA (8). miRNAs play important roles in tumor development by regulating the expression of various oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (8). miRNAs suppress tumorigenicity and multidrug resistance. For example, miR-199a suppresses tumorigenicity and multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer-initiating cells (9). miR-200b in the renal cell carcinoma cell line inhibits cell proliferation and migration, suggesting that miR-200b functions as tumor suppressors in the renal cell carcinoma (10).

miR-200b is decreased in taxol-resistant human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells (SPC-A1) (11). miR-200b reverses the phenotype of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in drug-resistant human tongue cancer cells and sensitizes them to chemotherapy (12). The up-regulation of miR-200b leads to the reversal of EMT in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells (13). miR-200b reverses the chemo-resistance of taxol by targeting E2F3 and by cell proliferation inhibition and apoptosis enhancement (14). miR-200b reverses resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor therapy by regulating the EMT process (15). Notch-1 induces an EMT consistent with cancer stem cell phenotype in pancreatic cancer cells by down-regulating the expression of miR-200b (16). Re-expression of miR-200b leads to the decreased expression of ZEB1 and vimentin and the increased expression of E-cadherin (16). miR-200b is involved in the Smad 3 pathway by regulating the expression of E-cadherin (17). miR-200b regulates EMT by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1 (18). Tamoxifen down-regulates miR-200b and promotes EMT by up-regulating c-Myc (19). These reports suggest roles of miR-200b in tumorigenesis, anti-cancer drug resistance, and EMT.

A number of miRNAs have been known to have pro- or anti-angiogenic effects. For example, miR-210 (20) and miR-29a (21) promotes angiogenesis whereas miR-200b inhibits angiogenesis (22). Vasohibin-2 promotes angiogenesis by exerting a negative regulation on the expression of miR-200b (23). miR-200b mimic prevents diabetes-induced increased VEGF expression, glucose-induced increased permeability, and angiogenesis (24). miR-200b binds to 3′-UTR of VEGFA promoter sequences to repress the expression of VEGF (24). The down-regulation of endothelial miR-200b promotes cutaneous wound angiogenesis by inducing the expression of GATA-binding protein 2 and VEGFR2 (25). miR-200b targets Ets-1, and the down-regulation of miR-200b induces an angiogenic response (26). Overexpression of Ets-1 rescues miR-200b-dependent impairment in angiogenic response (26). CAGE is a member of the Ets family transcription factors (5). These reports (5, 26) imply a role of CAGE in angiogenesis and the possibility of a feedback regulatory loop between CAGE and miR-200b.

A number of reports suggest a close relationship between CAGE and miR-200b. Previous reports imply that CAGE may serve as a target of miR-200b. Although the roles of CAGE in tumorigenesis and anti-cancer resistance have been demonstrated, the effect of CAGE on tumor-induced angiogenesis remains unknown. Based on previous reports, we hypothesized that CAGE and miR-200b would form a feedback regulatory loop and regulate various cellular processes, such as response to anti-cancer drugs, invasion, tumorigenic potential, and angiogenesis.

In this study, we examined the possibility of a feedback regulatory loop between CAGE and miR-200b. We examined the effect of miR-200b on the expression of CAGE and vice versa. We demonstrated that miR-200b and CAGE exerted opposite regulations on in vitro response to microtubule-targeting drugs, and the invasion potential of cancer cells is demonstrated. We investigated the effect of CAGE and miR-200b on the invasion potential of cancer cells. We found that miR-200b decreased the tumorigenic potential of cancer cells in a manner associated with the down-regulation of CAGE. Evidence of the involvement of CAGE in tumor-induced angiogenesis and VEGF-promoted angiogenesis was demonstrated. In this study, we revealed that miR-200b is a novel regulator of CAGE, which may provide a therapeutic target for the treatment of CAGE-driven cancers.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Cancer cell lines used in this study were cultured in Dulbecco's modified minimal essential medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) and antibiotics at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with a mixture of 95% air and 5% CO2. SNU387R or Malme3MR cells stably expressing miR-200b were generated by transfection of miR-200b cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector. Stable transfectants were selected by G418 (400 μg/ml). Cancer cell lines made resistant to celastrol or taxol were established by stepwise addition of celastrol or taxol. Malme3MR, SNU387R, or AGSR cells denote cells selected for resistance to celastrol. Cells surviving drug treatment (attached fraction) were obtained and used throughout this study. SNU387R-AS-CAGE or Mame3MR-AS-CAGE cell line was established by transfection with anti-sense CAGE cDNA. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated from human umbilical cord veins by collagenase treatment and used in passages 3–6. The cells were grown in M199 medium supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 3 ng/ml bFGF (Upstate Biotechnology, Waltham, MA), and 5 units/ml heparin at 37 °C under 5% CO2, 95% air.

Materials

Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate antibodies were purchased from Pierce. An enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit was purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Lipofectamine and PlusTM reagent were purchased from Invitrogen. Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea) synthesized all primers used in this study. Human recombinant VEGF protein was purchased from Millipore. Human recombinant CAGE protein was purchased from Abnova.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis and immunoprecipitation were performed according to the standard procedures (6). For analysis of proteins from tumor tissues, frozen samples were ground to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle over liquid nitrogen. Proteins were solubilized in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation.

Northern Blot

Total RNAs were isolated by TRIzol reagent according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). RNA samples (10 μg) were denatured with formaldehyde, electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels containing 2.2 m formaldehyde in MOPS buffer, and blotted to a nylon membrane (Pierce). A DIG-labeled CAGE probe was generated with a DIG-PCR amplification kit (Roche Applied Science). Northern hybridization was performed in buffer containing 5× SSC, 50% formamide, 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.02% SDS, and 2% blocking reagent (Roche Applied Science) at 68 °C for 12 h. The membrane was washed with 2× SSC containing 0.1% SDS at room temperature for 30 min and with 0.1× SSC containing 0.1% SDS at 68 °C for 45 min and incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (Roche Applied Science). For the detection of the hybridized probe, the membrane was soaked in CDP-Star chemiluminescence substrate (Roche Applied Science) and exposed to x-ray film, which was processed for imaging. As a loading control, the membrane was used for re-hybridization with a DIG-labeled probe of actin.

Cell Viability Determination

The cells were assayed for their growth activity using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma). Viable cell number counting was carried out by trypan blue exclusion assays.

Anchorage-independent Growth Assays

Anchorage-independent growth assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore). The assays were done in 96-well plates, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 21–28 days. Anchorage-independent growth was evaluated by using the cell stain solution. Stained colonies were counted using a microscope, and the intensity of staining was quantified by measuring absorbance at 490 nm.

Annexin V-FITC Staining

Apoptosis determination was carried out by using annexin V-FITC according to the manufacturer's instructions (Biovision). Ten thousand cells were counted for three independent experiments.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total miRNA was isolated using the mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion). miRNA was extended by a poly(A) tailing reaction using the A-Plus poly(A) polymerase tailing kit (CellScript). cDNA was synthesized from miRNA with poly(A) tail using a poly(T) adaptor primer and qScriptTM reverse transcriptase (Quanta Biogenesis). Expression levels of miR-200b were quantified with a SYBR Green qRT-PCR kit (Ambion) using a miRNA-specific forward primer and a universal poly(T) adaptor reverse primer. The expression of miR-200b was defined based on the threshold (Ct), and relative expression levels were calculated as 2−((Ct of miR-200b) − (Ct of U6)) after normalization with reference to expression of U6 small nuclear RNA. For quantitative PCR, SYBR PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used in a CFX96 real time system thermocycler (Bio-Rad). For detection of CAGE mRNA level, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and 1 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize complementary DNA using random primers and reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II RT; Invitrogen). The mRNA level for CAGE was normalized to the β-actin value, and relative quantification was determined using the ΔC model presented by PerkinElmer Life Sciences.

ChIP Assays

Assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Upstate Biotechnology). For detection of binding the protein of interest to miR-200b promoter sequences, specific primers of miR-200b promoter-1 sequences (5′-CACCCCCTGCCCTCAGAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCCACGTGCTGCCTTGTC-3′ (antisense)), miR-200b promoter-2 sequences (5′-CTTCCTATGGGACCACCCAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGGCACTGAGGACAGCATC-3′ (antisense)), and miR-200b promoter-3 sequences (5′-GGTGGAAGGTGCCAGAAAAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTGGAGCCCAGAGACCCTA-3′ (antisense)) were used. For detection of binding the protein of interest to the E-cadherin promoter sequences, specific primers of E-cadherin promoter-1 sequences (5′-ACAGAGCATTTATGGCTCAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCATGGGTTAGTGAGTCAGC-3′ (antisense)) and E-cadherin promoter-2 sequences (5′-AAGCCCTTTCTGATCCCAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGCTGATTGGCTGAGGGT-3′ (antisense)) were used in the miR-200b and pGL3–3′-UTR-CAGE construct.

To generate miR-200b expression vector, a 330-bp genomic fragment encompassing the primary miR-200b gene was PCR-amplified and cloned into BamHI/XhoI site of pcDNA3.1 vector. To generate the pGL3–3′-UTR-CAGE construct, a 136-bp human CAGE gene segment encompassing 3′-UTR was PCR-amplified and subcloned into the XbaI site of pGL3 luciferase plasmid. The mutant pGL3–3′-UTR-CAGE construct was made with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Luciferase activity assay was performed according to the instruction manual (Promega).

Transfection

Transfections were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Lipofectamine and Plus reagents (Invitrogen) were used. The construction of siRNA was carried out according to the instruction manual provided by the manufacturer (Ambion, Austin, TX). For miR-200b knockdown, cells were transfected with 200 nm of oligonucleotide (inhibitor) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The sequences used were 5′-UCAUCAUUACCCAGUAUUA-3′ (miR-200b inhibitor) and 5′-GCAUAUAUCUAUUCCACUA-3′ (control inhibitor).

In Vivo Metastasis Assay

Female athymic nude mice were used for the studies. Cells evaluated included Malme3M, Malme3MR, and Malme3MR-miR-200b. Cells (106 cells in PBS) were injected intravenously into the tail vein of 4-week-old athymic nude mice, and the extent of lung metastasis was evaluated. Control inhibitor (50 μm/kg) or miR-200b inhibitor (50 μm/kg) was injected intravenously into the tail vein of athymic nude mice five times. Four weeks after injection of cancer cells, surface metastatic nodules per lung were determined.

In Vivo Tumorigenic Potential

Athymic nude mice (BALB/c nu/nu, 5–6-week-old females) were obtained from Orient Bio Inc. (Seoul, Korea) and were maintained in a laminar air-flow cabinet under aseptic conditions. Cancer cells (1 × 106) of interest were injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flank area of the mice. Tumor volume was determined by direct measurement with calipers and calculated by the following formula: length × width × height × 0.5. To determine the effect of miR-200b on in vivo tumorigenic potential, control inhibitor (40 μg/kg or 50 μm/kg) or miR-200b inhibitor (40 μg/kg or 50 μm/kg) was injected via the tail vein seven times at a total of 37 days.

Chemoinvasion Assays

The invasion potential was determined by using a transwell chamber system with 8-μm pore polycarbonate filter inserts (CoSTAR, Acton, MA). The lower and upper sides of the filter were coated with gelatin and Matrigel, respectively. Trypsinized cells (5 × 103) in the serum-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin were added to each upper chamber of the transwell. RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum was placed in the lower chamber, and cells were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. The cells were fixed with methanol, and the invaded cells were stained and counted. To determine the effect of miR-200b on invasion potential, cells of interest were transfected with miR-200b construct (1 μg) or miR-200b inhibitor (200 nm). 48 h after transfection, the invasion potential of cancer cells was determined. To determine the effect of CAGE on invasion of HUVECs, conditioned medium obtained from each cancer cell line was placed onto the lower chamber of the transwell. The trypsinized HUVECs (4 × 104) in M199 medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 1% FBS were added to the upper chamber of the transwell. The number of invading cells was determined at 24 h after addition of HUVECs.

Endothelial Cell Tube Formation Assays

Growth factor-reduced Matrigel was pipetted into prechilled 24-well plates (200 μl of Matrigel per well) and polymerized for 30 min at 37 °C. The HUVECs were placed onto a layer of Matrigel in 1 ml of M199 containing 1% FBS. After 6–8 h of incubation at 37 °C in a 95:5% (v/v) mixture of air and CO2, the endothelial cells were photographed using an inverted microscope (magnification, ×100; Olympus). Tube formation was observed using an inverted phase contrast microscope. Images were captured with a videograph system. The degree of tube formation was quantified by measuring the length of tubes in five randomly chosen low power fields (×100) from each well using the Image-Pro Plus Version 4.5 (Media Cybernetics, San Diego).

Intravital Microscopy

Male BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Daehan Biolink (Korea). In vivo angiogenesis was assessed as follows. The mice were anesthetized with 2.5% avertin (v/v) via intraperitoneal injection (Surgivet), and abdominal wall windows were implanted. Next, a titanium circular mount with eight holes on the edge was inserted between the skin and the abdominal wall. Growth factor-reduced Matrigel containing conditioned medium was applied to the space between the windows, and a circular glass coverslip was placed on top and fixed with a snap ring. After 4 days, the animals were anesthetized and injected intravenously with 50 μl of 25 ng/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran (Mr ∼2,000,000) via the tail vein. The mice were then placed on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope. The epi-illumination microscopy setup included a 100-watt mercury lamp and filter set for blue light. Fluorescence images were recorded at random locations of each window using an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Photo Max 512, Princeton Instruments) and digitalized for subsequent analysis using the Metamorph program (Universal Imaging). The assay was scored from 0 (negative) to 5 (most positive) in a double-blind manner.

In Vivo Matrigel Plug Assay

Seven-week-old BALB/c mice (DBL Co., Ltd., Korea) were injected subcutaneously with 0.1 ml of Matrigel containing conditioned medium and 10 units of heparin (Sigma). The injected Matrigel rapidly formed a single and solid gel plug. After 8 days, the skin of the mouse was easily pulled back to expose the Matrigel plug, which remained intact.

Aortic Ring Formation Assays

In brief, 96-well plates were coated with 30 μl of Matrigel per well and polymerized in an incubator. Aortas isolated from 6-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats were cleared of periadventitial fat and connective tissues in cold PBS and cut into rings of 1–1.5 mm in circumference. The aortic rings were randomized into wells and sealed with a 30-μl overlay of Matrigel. PBS, conditioned medium, recombinant VEGF protein, or recombinant CAGE protein was added. After 6 days, the extent of micro vessel sprouting was determined by using an inverted microscope (magnification, ×100; Olympus). The assay was scored from 0 (negative) to 5 (most positive) in a double-blind manner. Conditioned medium was also employed to examine the effect of CAGE on aortic ring formation.

Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assay

Chick CAM assay was carried out as described previously (11). Briefly, salt-free solution (10 μl) containing recombinant VEGF (final at 20 ng/ml) or recombinant CAGE (final 20 ng/ml) was applied to Thermanox discs, and incubation was continued for 30 min. The discs were loaded onto the CAM of 9-day-old embryos. After 5 days of incubation at 37 °C, the area around the loaded disc was photographed with a digital camera, and the number of newly formed vessels was counted inside the disc area. Conditioned medium of Malme3M, Malme3MR, or Malme3MR-AS-CAGE was also employed to determine the effect of CAGE on blood vessel formation based on CAM assays.

Cytokine Array Analysis

Expression levels of cytokines were determined by using Proteom ProfilerTM mouse cytokine array kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences in this were determined by using the Student's t test.

RESULTS

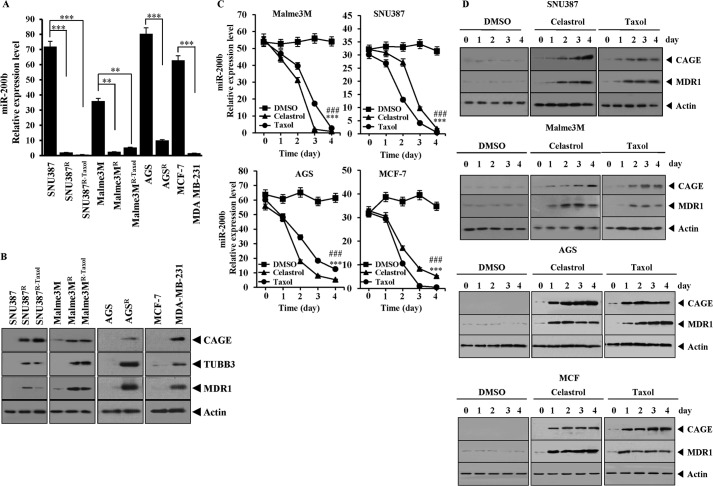

miR-200b Is Decreased in Cancer Cell Lines Resistant to Microtubule-targeting Drugs

Previously, the role of CAGE in anti-cancer drug resistance was reported (6). However, factor(s) that regulate the expression of CAGE remain unknown. It was hypothesized that miRNAs that are decreased in cancer cell lines resistant to anti-cancer drugs would regulate the expression of CAGE. To identify these miRNAs, miRNA array analysis was performed, which revealed that miR-200b was greatly decreased in Malme3MR, a melanoma cell line resistant to celastrol (data not shown). Several reports suggest a possible feedback regulatory loop between CAGE and miR-200b (5, 26). qRT-PCR was performed to examine the expression level of miR-200b in various cancer cell lines. miR-200b showed lower expression in SNU387R and SNU387R-Taxol, hepatic cancer cell lines made resistant to celastrol and taxol, respectively, than in non-resistant counterparts (Fig. 1A). miR-200b also showed lower expression in Malme3MR and Malme3MR-Taxol, melanoma cell lines made resistant to celastrol and taxol, respectively (Fig. 1A). AGS, a gastric cancer cell line, showed a higher expression of miR-200b than AGSR, a gastric cancer cell line made resistant to celastrol (Fig. 1A). MDA-MB-231, a malignant breast cancer cell line, showed lower expression level of miR-200b than MCF-7, a less malignant breast cancer cell line (Fig. 1A). The expression of CAGE was higher in cancer cell lines resistant to microtubule-targeting drugs than in cancer cell lines sensitive to microtubule-targeting drugs (Fig. 1B). Cancer cell lines resistant to microtubule-targeting drugs showed higher expression levels of tubulin β3 and MDR1 (Fig. 1B). The increased expression level of tubulin β3 is closely related to taxol resistance (27). Celastrol and taxol decreased the expression of miR-200b in SNU387, Malme3M, AGS, and MCF-7 cells based on qRT-PCR (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the down- regulation of miR-200b is associated with resistance to microtubule-targeting drugs. Celastrol and taxol increased the expression of CAGE and MDR1 in SNU387, Malme3M, AGS, and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these results suggest that the down-regulation of miR-200b and the increased expression of CAGE may result in resistance to microtubule-targeting drugs.

FIGURE 1.

Expression level of miR-200b shows an inverse relationship with CAGE. A, expression level of miR-200b in each cell line was determined by qRT-PCR. Each value represents an average obtained from three independent experiments. Data are expressed as a mean ± S.D. **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.0005. B, cell lysate prepared from each cell line was subjected to Western blot analysis. C, indicated cell line was treated with or without celastrol (100 nm) or taxol (100 nm) for various time intervals. The expression level of miR-200b was determined by qRT-PCR. Each value represents an average obtained from three independent experiments. Data are expressed as a mean ± S.D. ***, p < 0.0005; ###, p < 0.0005. Comparison was made between the cells treated with celastrol or taxol and the cells untreated. *** denotes statistical significance in response to celastrol. ### denotes statistical significance in response to taxol. D, same as C except that Western blot analysis was performed.

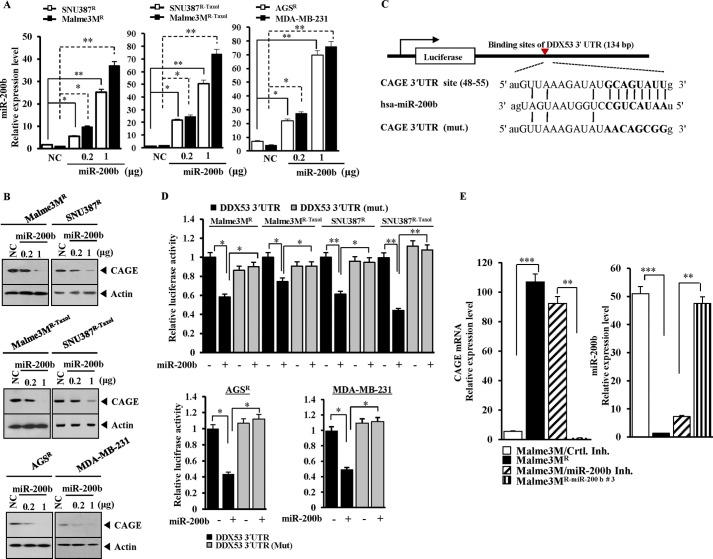

miR-200b Directly Regulates the Expression of CAGE

Because miR-200b showed an inverse relationship with CAGE (Fig. 1, A and B), it was hypothesized that miR-200b might regulate the expression of CAGE. The transfection of miR-200b in SNU387R, SNU387R-Taxol, Malme3MR, Malme3MR-Taxol, AGSR, and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2A) decreased the expression of CAGE (Fig. 2B). Target scan analysis predicted the binding of miR-200b to 3′-UTR of CAGE (Fig. 2C). The transfection of miR-200b decreased the luciferase activity of the Luc-3′-wild type UTR of CAGE but not Luc-3′-mutant UTR of CAGE in cancer cell lines resistant to microtubule-targeting drugs (Fig. 2D). Malme3MR cells showed a higher expression level of CAGE mRNA than Malme3M cells based on qRT-PCR (Fig. 2E). The stable expression of miR-200b decreased the CAGE mRNA level in Malme3MR (Fig. 2E). The transfection of miR-200b inhibitor in Malme3M cells increased the expression level of CAGE mRNA (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results suggest that miR-200b targets CAGE.

FIGURE 2.

miR-200b targets CAGE. A, indicated cell line was transfected with control vector (NC, 1 μg) or miR-200b construct (0.2, 1 μg). 48 h after transfection, qRT-PCR was performed. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005. B, same as A except that Western blot analysis was performed. NC, negative control vector. C, potential binding of miR-200b to 3′-UTR-CAGE. D, wild type Luc-CAGE-3′-UTR or mutant Luc-CAGE-3′-UTR was transfected along with control vector (−) or miR-200b construct (+) into the indicated cell line. 48 h after transfection, luciferase activity was performed as described. E, Malme3M cells were transfected with control inhibitor (200 nm) or miR-200b inhibitor (200 nm). 48 h after transfection, mRNAs were prepared from the indicated cancer cells and subjected to qRT-PCR. miRNAs were also isolated from the indicated cancer cells and subjected to qRT-PCR. ***, p < 0.005.

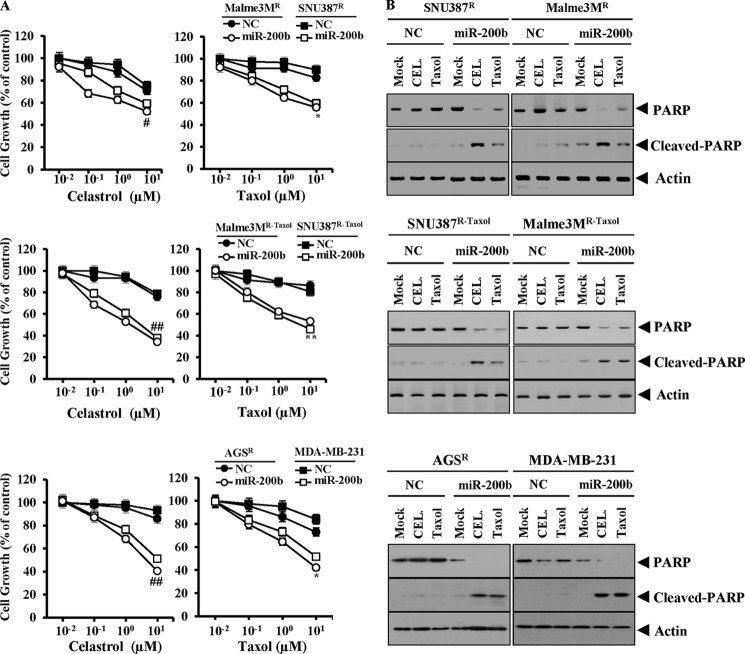

miR-200b Regulates the Response to Microtubule-targeting Drugs in Vitro

Because miR-200b targets CAGE, the effect of miR-200b on the response to microtubule-targeting drugs was next investigated. The transfection of miR-200b enhanced the sensitivity of SNU387R/Malme3MR, SNU387R-Taxol/Malme3MR-Taxol, AGSR, and MDA-MB231 cells to celastrol and taxol (Fig. 3A). The transfection of miR-200b enhanced the cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in response to celastrol and taxol in these anti-cancer drug-resistant cancer cell lines (Fig. 3B). miR-200b inhibitor decreased the expression of miR-200b in Malme3MR/SNU387R cells that stably express miR-200b (Malme3MR miR-200b/SNU387R-miR-200b) (Fig. 4A). miR-200b inhibitor induced the expression of CAGE and MDR1 in Malme3MR-miR-200b and SNU387R-miR-200b cells (Fig. 4B). The transfection of the Luc-3′-wild type UTR of CAGE, but not the Luc-3′-mutant UTR of CAGE, led to the decreased luciferase activity in Malme3MR-miR-200b and SNU387R-miR-200b cells (Fig. 4C). the miR-200b inhibitor prevented miR-200b from decreasing the luciferase activity associated with the transfection of the Luc-3′-wild type UTR of CAGE (Fig. 4C). Malme3MR- miR-200b/SNU387R-miR-200b cells showed a higher proportion of annexin V-positive cells in response to celastrol and taxol (Fig. 4D). The transfection of miR-200b inhibitor decreased the proportion of annexin V-positive cells in response to celastrol and taxol in these cancer cells (Fig. 4D). The transfection of miR-200b inhibitor decreased the proportion of annexin V-positive cells in response to celastrol and taxol in SNU387 and Malme3M cells (data not shown). The transfection of miR-200b inhibitor prevented the cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in response to microtubule-targeting drugs in SNU387 and Malme3M cells (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that the expression level of miR-200b determines the response to microtubule-targeting drugs.

FIGURE 3.

miR-200b confers sensitivity to microtubule-targeting drugs. A, indicated cell line was transfected with control vector (NC) (1 μg) or miR-200b (1 μg). 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without various concentrations of celastrol or taxol for 24 h, followed by 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assays. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005; #, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.005. Comparison was made between cells transfected with miR-200b construct and cells transfected with control vector. * and ** denote statistical difference in response to taxol. # and ## denote statistical difference in response to celastrol (CEL). B, indicated cell line was transfected with control vector (NC) or miR-200b construct. 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without celastrol (1 μm) or taxol (1 μm) for 24 h, followed by Western blot analysis. PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of miR-200b induces resistance to microtubule-targeting drugs and increases expression of CAGE. A, Malme3MR cells stably expressing miR-200b (Malme3MR-miR-200b) or SNU387R cells stably expressing miR-200b (SNU387R-miR-200b) were transfected with control inhibitor (200 nm) or miR-200b inhibitor (200 nm). 48 h after transfection, qRT-PCR was performed as described. miRNA isolated from Malme3MR or SNU387R cells transfected with control inhibitor was also subjected to qRT-PCR.**, ***, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.0005. B, same as A except that Western blot analysis was performed. C, indicated cell line was transfected with Luc-wild type 3′-UTR-CAGE (1 μg) or Luc-mutant 3′-UTR-CAGE construct (1 μg) with or without control inhibitor (Ctrl. Inh.) (200 nm) or miR-200b inhibitor (200 nm). 48 h after transfection, luciferase activity assays were performed. D, Malme3MR-miR-200b or SNU387R-miR-200b cells were transfected with miR-200b inhibitor (200 nm) or control inhibitor (200 nm). Malme3MR or SNU387R cells were transfected with control inhibitor (200 nm). 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without celastrol (1 μm) or taxol (1 μm) for 24 h, followed by annexin V-FITC staining. E, Malme3MR cells were transfected with control inhibitor (200 nm). 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without celastrol (1 μm) or taxol (1 μm) for 24 h, followed by Western blot analysis. PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

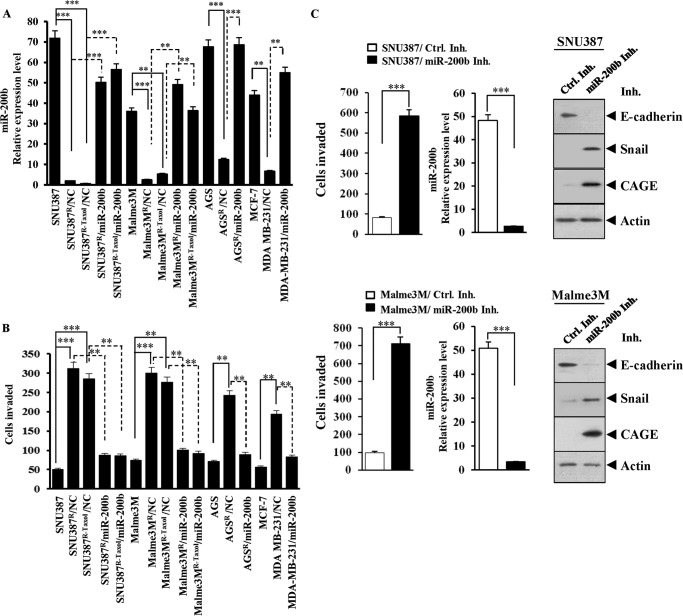

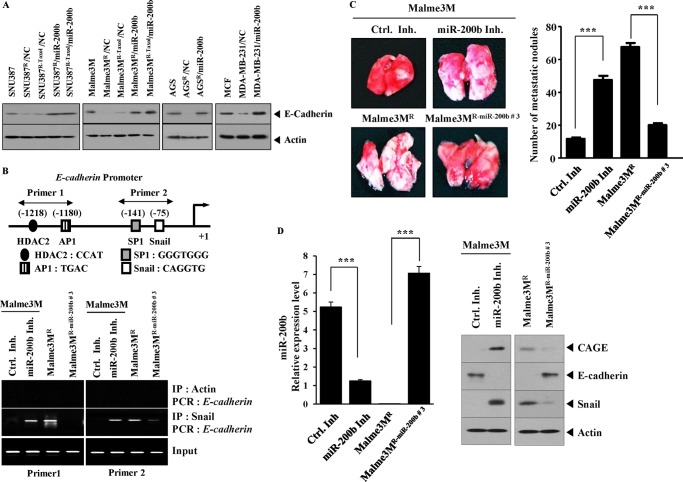

miR-200b Exerts Regulations on the Invasion and Metastatic Potential of Cancer Cells

miR-200b regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (17, 28). The effect of miR-200b on invasion potential in relation to CAGE was examined. Anti-cancer drug-resistant cancer cell lines showed higher invasion potential than anti-cancer drug-sensitive counterparts (Fig. 5B). The transfection of miR-200b (Fig. 5A) decreased the invasion potential of these anti-cancer drug-resistant cancer cell lines (Fig. 5B). miR-200b inhibitor enhanced the invasion potential of SNU387 and Malme3M cells (Fig. 5C). miR-200b inhibitor increased the expression of CAGE and Snail while decreasing the expression of E-cadherin in SNU387 and Malme3M cells (Fig. 5C). The anti-cancer drug-resistant cancer cell lines showed lower expression of E-cadherin than the anti-cancer-sensitive counterparts (Fig. 6A). The transfection of miR-200b increased the expression of E-cadherin in these anti-cancer drug-resistant cancer cell lines (Fig. 6A). The E-cadherin promoter sequences contain putative binding sites for transcription factors, such as AP1, HDAC2, SP1, and Snail (Fig. 6B). ChIP assays showed the binding of Snail to the promoter sequences of E-cadherin in Malme3MR cells (Fig. 6B). E-cadherin promoter sequences contain a binding site for HDAC2 (Fig. 6B). Malme3MR cells express a higher level of HDAC2 than Mame3M cells (6). HDAC2 interacts with Snail to repress E-cadherin expression (29). It is probable that HDAC2 binds to the promoter sequences of E-cadherin in Malme3MR cells through interaction with Snail. An athymic nude mouse model was employed to examine the effect of miR-200b on the metastatic potential of cancer cells. Malme3MR cells displayed higher metastatic potential than Mame3M cells (Fig. 6C). Malme3MR-miR-200b cells showed lower metastatic potential than Malme3MR cells (Fig. 6C). The miR-200b inhibitor enhanced the metastatic potential of Malme3M cells (Fig. 6C). The Western blot of lung tumor tissue lysates showed a negative regulatory role of miR-200b in the expression of CAGE and Snail (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these results suggest that the effect of miR-200b on invasion and metastatic potential involves the expression regulation of CAGE by miR-200b.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of miR-200b on invasion potential of cancer cells involves expression regulation of CAGE. A, SNU387R, SNU387R-taxol, Malme3MR, Malme3MR-taxol, AGSR, or MDA-MB231 cells were transfected with control vector (NC, 1 μg) or miR-200b construct (1 μg). 48 h after transfection, miRNAs were isolated, and qRT-PCR was performed. miRNAs were also isolated from SNU387, Malme3M, AGS, or MCF-7 cells and subjected to qRT-PCR. **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.0005. B, same as A except that invasion potential was measured as described. C, SNU387 or Malme3M cells were transfected with control inhibitor (Ctrl. Inh.) (200 nm) or miR-200b inhibitor (200 nm). 48 h after transfection, invasion potential was measured (left panel). miRNAs were isolated and subjected to qRT-PCR (middle panel). Cell lyastes were isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis (right panel).

FIGURE 6.

miR-200b regulates metastatic potential of cancer cells. A, cell lysates prepared from the indicated cell lines were subjected to Western blot analysis. B, Malme3M cells were transfected with control inhibitor (Ctrl. Inh.) (200 nm) or miR-200b inhibitor (200 nm). 48 h after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to ChIP assays. Cell lysates prepared from Malme3MR and Malme3MR-miR-200b cells were also subjected to ChIP assays. IP, immunoprecipitation. C, each experimental group consists of five athymic nude mice. Each figure shows a representative image of the mice in each experimental group. Control inhibitor (50 μm/kg) or miR-200b inhibitor (50 μm/kg) was intravenously injected five times over a total of 4 weeks. miR-200b significantly decreases the metastatic potential of Malme3MR cells. miR-200b inhibitor enhances the metastatic potential of Malme3M cells. D, miRNAs isolated from mice of each experimental group were subjected to qRT-PCR (left panel). Tissue lysates isolated from mice of each experimental group were subjected to Western blot analysis (right panel). ***, p < 0.0005.

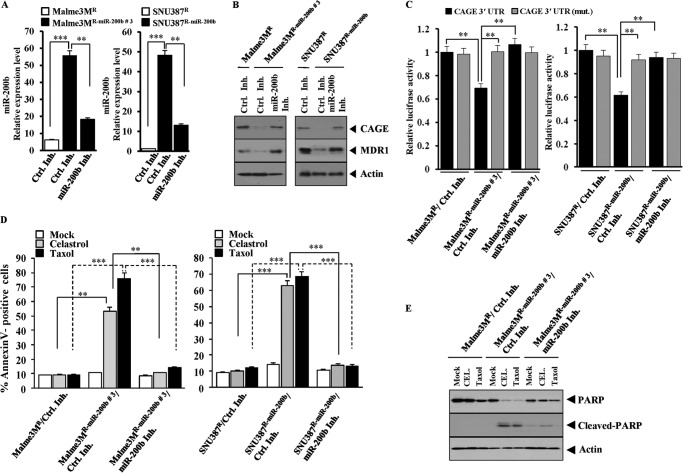

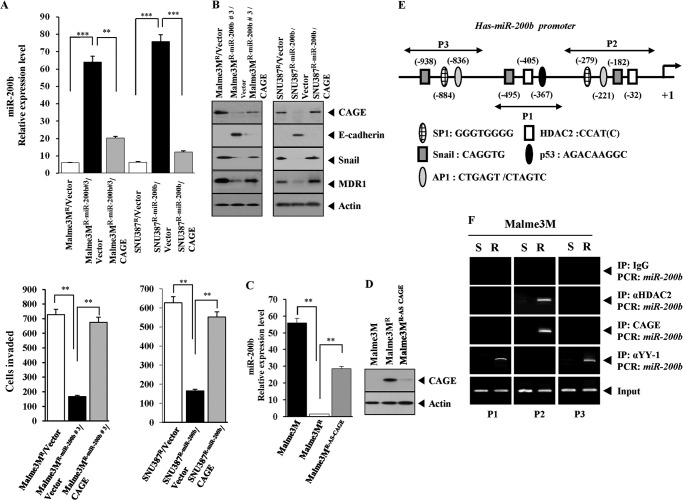

CAGE Directly Regulates the Expression of miR-200b

The possibility of expression regulation of miR-200b by CAGE was examined. The transfection of CAGE into Malme3MR-miR-200b or SNU387R-miR-200b cells decreased the expression of miR-200b (Fig. 7A). CAGE enhanced the invasion potential of Malme3MR-miR-200b and SNU387R-miR-200b cells (Fig. 7A). The transfection of CAGE into Malme3MR-miR-200b or SNU387R-miR-200b cells induced the expression of Snail and MDR1 while decreasing the expression of E-cadherin (Fig. 7B). Malme3MR cells that stably express antisense CAGE showed a higher expression level of miR-200b than Malme3MR cells (Fig. 7, C and D). The direct involvement of CAGE in the expression regulation of miR-200b was examined. According to promoter analysis, miR-200b promoter sequences contain putative binding sites for transcription factors, including HDAC2, p53, Snail, and SP1 (Fig. 7E). Because CAGE interacts with HDAC2 to repress the expression of p53, it was hypothesized that CAGE would bind to the promoter sequences of miR-200b. CAGE and HDAC2 were shown to bind to the miR-200b promoter sequences in Malme3MR cells (Fig. 7F). YY1 interacts with HDAC2 and regulates the expression of human B type natriuretic peptide (30). YY1 negatively regulates the mouse myelin proteolipid protein (Plp1) gene (31). YY1 represses muscle miRNA expression in myoblasts, and the repression is mediated through multiple enhancers and the recruitment of Polycomb complex to several YY1-binding sites (32). YY1 forms a feedback regulatory loop with miR-1 in myoblasts (32). YY1 showed binding to the promoter sequences of miR-200b in Malme3MR cells (Fig. 7F), suggesting that YY1 may be a negative regulator of miR-200b. p53 regulates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition through microRNAs, such as miR-200b, targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 (33). It is probable that p53 up-regulates the expression of miR-200b in the drug-sensitive cancer cell lines employed in this study. Taken together, these results show that miR-200b and CAGE target each other. In other words, miR-200b and CAGE form a feedback regulatory loop.

FIGURE 7.

CAGE regulates the expression of miR-200b. A, Malme3MR-miR-200b or SNU387R-miR-200b cells were transfected with control vector (1 μg) or CAGE cDNA (1 μg). 48 h after transfection, miRNA was isolated and subjected to qRT-PCR (upper panel). miRNAs isolated from Malme3MR or SNU387R cells transfected with control vector were also subjected to qRT-PCR. Effect of CAGE on invasion potential was examined (lower panel). **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.0005. B, same as A except that Western blot analysis was performed. C, miRNAs isolated from the indicated cell lines were subjected to qRT-PCR. D, same as C except that Western blot analysis was performed. Malme3MR-AS-CAGE denotes Malme3MR cells stably expressing antisense CAGE cDNA. E, miR-200b promoter sequences. F, cell lysates prepared form the indicated cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the indicated antibody (2 μg/ml), followed by ChIP assays. S denotes drug-sensitive Malme3M, and R denotes drug-resistant Malme3M cells.

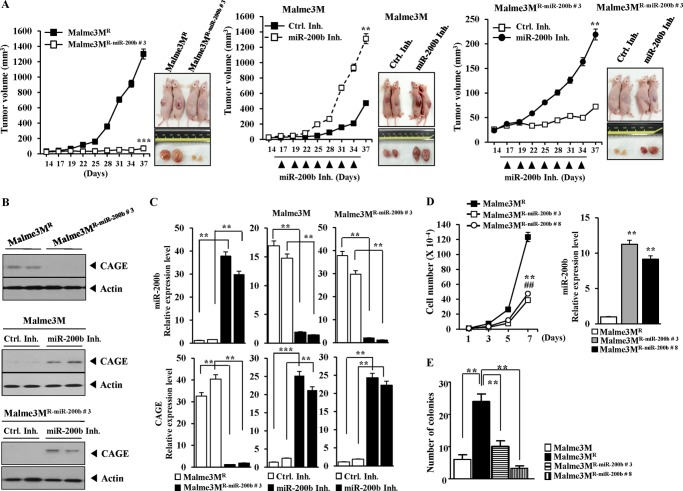

miR-200b Decreases in Vivo Tumorigenic Potential in a Manner Associated with the Down-regulation of CAGE

The effect of miR-200b on tumorigenic potential was examined. Malme3MR cells showed higher tumorigenic potential than Malme3MR-miR-200b cells (Fig. 8A). miR-200b inhibitor enhanced tumorigenic potential of Malme3M cells (Fig. 8A). miR-200b inhibitor enhanced tumorigenic potential of Malme3MR-miR-200b cells (Fig. 8A). Western blot analysis of tumor tissue lysates showed a negative regulatory effect of miR-200b on the expression of CAGE (Fig. 8B). The qRT-PCR analysis of tumor tissue showed a negative regulatory effect of miR-200b on the expression of CAGE mRNA (Fig. 8C). The miR-200b inhibitor decreased the expression of miR-200b in Malme3M and Malme3MR-miR-200b cells (Fig. 8C). The Malme3MR-miR-200b cell lines showed lower cellular proliferation rates than Malme3MR cells (Fig. 8D). Malme3MR-miR-200b cell lines also showed lower growth rate under anchorage-independent conditions than Malme3MR cells (Fig. 8E). Taken together, these results suggest that the negative regulatory role of miR-200b in tumorigenic potential involves the expression regulation of CAGE by miR-200b.

FIGURE 8.

miR-200b regulates the tumorigenic potential of cancer cells in vivo. A, Malme3MR (1 × 106) or Malme3MR-miR-200b (1 × 106) cells were injected into the dorsal flanks of athymic nude mice (left panel). Malme3M (1 × 106) cells were injected into the dorsal flanks of athymic nude mice (middle panel). Following the establishment of sizeable tumor, control inhibitor (Ctrl Inh.) (40 μg/kg or 50 μm/kg) or miR-200b inhibitor (40 μg/kg or 50 μm/kg) was injected. Malme3MR-miR-200b (1 × 106) cells were injected into the dorsal flanks of athymic nude mice (right panel). Following the establishment of a sizeable tumor, control inhibitor (40 μg/kg or 50 μm/kg) or miR-200b inhibitor (40 μg/kg or 50 μm/kg) was injected. Each experimental group consisted of five mice. Each value represents an average obtained from the five athymic nude mice of each group. Data are expressed as a mean ± S.D. Each figure shows a representative image of the mice in each group at the time of sacrifice. B, lysates isolated from each tumor tissue were subjected to Western blot. C, miRNAs isolated from the indicated tumor tissues were subjected to qRT-PCR. Messenger RNAs isolated from the indicated tumor tissues were also subjected to qRT-PCR to determine the expression level of CAGE mRNA. ***, p < 0.0005. D, cellular proliferation of each indicated cell line was measured (left panel). Malme3MR-miR-200b#3 and Malme3MR-miR-200b#8 denote Malme3MR cells stably expressing miR-200b. The number of viable cells was determined by trypan blue exclusion staining. ** denotes statistical difference between Malme3MR and Malme3MR-miR-200b #8. ## denotes statistical difference between Malme3MR and Malme3MR-miR-200b#3. The expression level of miR-200b in the indicated cell line was determined by qRT-PCR (right panel). E, indicated cell lines were subjected to anchorage-independent growth assays.

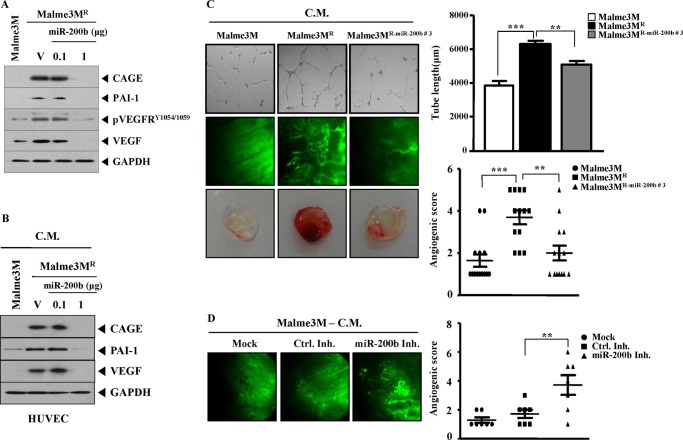

miR-200b Regulates Tumor-induced Angiogenesis

miR-200b regulates the expression of VEGF (25). The effect of miR-200b on tumor-induced angiogenesis was next examined. Malme3MR cells showed higher expression levels of CAGE, PAI-1, VEGF, and pVEGFR2Y1054/1059 than Malme3M cells (Fig. 9A). This suggests that Malme3MR cells may enhance the angiogenic potential of human endothelial cells via angiogenic factors such as VEGF and PAI-1. PAI-1 facilitates retinal angiogenesis (34) and is necessary for sonic hedgehog-induced cerebral angiogenesis (35). VEGF-B binds to VEGFRI and regulates PAI-1 activity (36). Tumor angiogenesis is dependent on HIF-1-dependent PAI-1 expression (37). These findings suggest a role for PAI-1 in angiogenesis. miR-200b decreased the expression of CAGE, PAI-1, VEGF, and pVEGFR2Y1054/1059 in Malme3MR cells (Fig. 9A). The conditioned medium obtained from Malme3MR cells, but not from Malme3M cells, increased expression of CAGE, PAI-1, and VEGF in HUVECs (Fig. 9B). The conditioned medium obtained from Malme3MR transfected with miR-200b did not affect the expression of CAGE, PAI-1, or VEGF in HUVECs (Fig. 9B), suggesting that miR-200b has a negative effect on tumor-induced angiogenesis. The conditioned medium of Malme3MR cells enhanced endothelial cell tube formation when added to HUVECs (Fig. 9C). However, the conditioned medium of Malme3MR-miR-200b cells did not enhance endothelial cell tube formation (Fig. 9C). The conditioned medium of Malme3MR cells enhanced blood vessel formation when mixed with Matrigel for intravital microscopy (Fig. 9C). However, the conditioned medium of Malme3MR-miR-200b cells did not enhance blood vessel formation (Fig. 9C). Matrigel plug assays also showed that miR-200b had a negative effect on tumor-induced angiogenesis (Fig. 9C). The conditioned medium obtained from Malme3M cells transfected with miR-200b inhibitor enhanced blood vessel formation in intravital microscopy analysis (Fig. 9D). Taken together, these results suggest that miR-200b acts as a negative regulator of tumor-induced angiogenesis by regulating the expression of CAGE.

FIGURE 9.

miR-200b regulates tumor-induced angiogenesis. A, Malme3MR cells were transfected with control vector (1 μg) or miR-200b construct (0.1, 1 μg). 48 h after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis. Cell lysates from Malme3M cells were also subjected to Western blot analysis. V denotes control vector. B, conditioned medium (C.M.) obtained from the indicated cells was added to HUVECs for 1 h, followed by Western blot analysis. C, conditioned medium obtained from the indicated cell line was added to HUVECs for 8 h, and endothelial cell tube formation assays were performed (upper panel). Concentrated conditioned medium (10 μl) obtained from the indicated cell line was mixed with 100 μl of Matrigel, and intravital microscopy was performed as described (middle panel). The conditioned medium was also subjected to Matrigel plug assays as described (bottom panel). **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.0005. D, Malme3M cells were transfected with control inhibitor (Ctrl. Inh.) or miR-200b inhibitor. 48 h after transfection, conditioned medium was obtained, and intravital microscopy was performed. The conditioned medium obtained from Malme3M cells was also subjected to intravital microscopy.

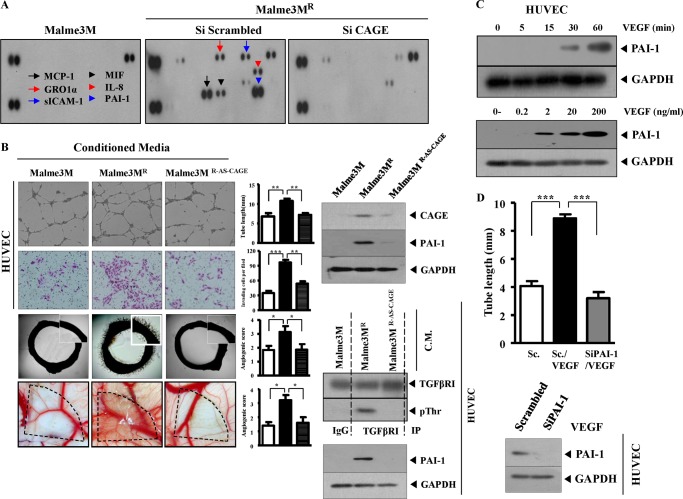

CAGE Mediates Tumor-induced Angiogenesis

In an effort to investigate the role of CAGE in angiogenesis, cytokine array analyses were performed to identify the factors that are regulated by CAGE. Malme3MR cells showed a higher expression of angiogenic factors such as PAI-1 than Malme3M cells (Fig. 10A). The down-regulation of CAGE decreased the expression of PAI-1 in Malme3MR cells. Soluble cytokines such as MCP1, GRO1-α, and sICAM-1 were also regulated by CAGE (Fig. 10B). The functional roles of these cytokines in angiogenesis in relation to CAGE require further investigation. The conditioned medium of Malme3MR cells enhanced human endothelial cell tube formation and also enhanced the invasion potential of HUVECs (Fig. 10B). The conditioned medium of Malme3MR cells that stably express antisense CAGE cDNA did not affect human endothelial cell tube formation or invasion potential (Fig. 10B). CAM assays confirmed the role of CAGE in tumor-induced angiogenesis (Fig. 10B). The conditioned medium of Malme3MR cells enhanced the aortic ring formation, and CAGE was necessary for this enhanced aortic ring formation (Fig. 10B). The conditioned medium of Malme3MR cells, when added to HUVECs, induced the activation of TGFβRI and the expression of PAI-1 (Fig. 10B). However, the conditioned medium of Malme3MR cells that stably express antisense CAGE cDNA did not induce the activation of TGFβRI or the expression of PAI-1 in HUVECs (Fig. 10B). VEGF induced the expression of PAI-1 in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 10C). PAI-1 was necessary for enhanced endothelial cell tube formation by VEGF (Fig. 10D). Taken together, these results suggest that CAGE mediates tumor-induced angiogenesis by regulating the expression of angiogenic factors such as PAI-1.

FIGURE 10.

CAGE mediates tumor-induced angiogenesis. A, cell lysates isolated from the indicated cell line were subjected to cytokine array analysis. B, conditioned medium (C.M.) (0.1 ml) obtained from the indicated cell line was added to HUVECs. Eight hours after addition of conditioned medium, endothelial cell tube formation assays were performed. Conditioned medium was also employed to examine the effect of CAGE on angiogenic potential of Malme3MR cells based on aortic ring formation and CAM assays. The effect of CAGE on the invasion potential of HUVECs was determined using a transwell chamber system. Data are expressed as a mean ± S.D. Cell lysates prepared from the indicated cancer cell line were also subjected to Western blot analysis (right upper panel). Conditioned medium of the indicated cell line was added to HUVECs. One hour after addition of conditioned medium, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the indicated antibody, followed by Western blot analysis (right lower panel). Cell lyastes were also subjected to Western blot analysis (right lower panel). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.0005. C, HUVECs were treated with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for various time intervals. Cell lysates prepared at each time point were subjected to Western blot analysis (upper panel). HUVECs were treated with various concentrations of VEGF for 1 h, followed by Western blot analysis (lower panel). D, HUVECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (10 nm) or PAI-1 siRNA (10 nm). 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. Cells were then subjected to endothelial cell formation assays. Data are expressed as a mean ± S.D. HUVECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (10 nm) or PAI-1 siRNA (10 nm). 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 1 h, followed by Western blot analysis. Sc denotes scrambled.

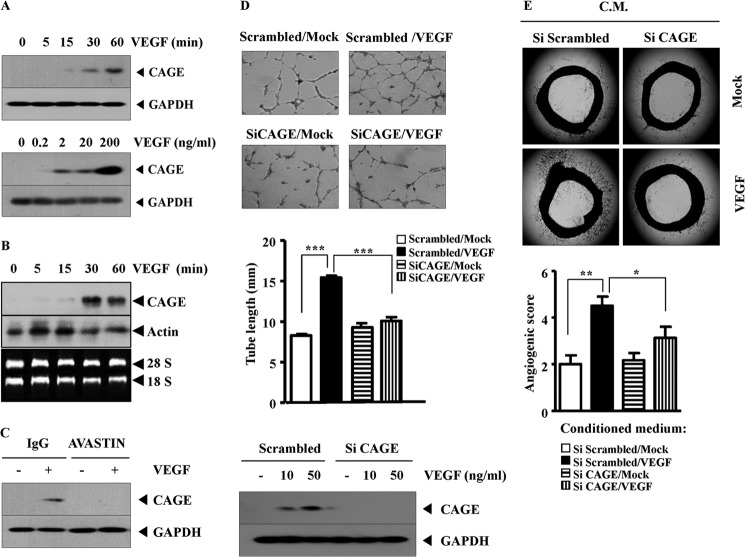

CAGE Mediates VEGF-promoted Angiogenesis

Because CAGE was necessary for tumor-induced angiogenesis, the necessity of CAGE for VEGF-promoted angiogenesis in HUVECs was examined. VEGF induced the expression of CAGE, in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 11A). Northern blot analysis showed the induction of CAGE at the transcriptional level (Fig. 11B). AVASTIN, a VEGF-naturalizing antibody, prevented VEGF from inducing the expression of CAGE (Fig. 11C), suggesting that VEGF specifically induces the expression of CAGE. The down-regulation of CAGE prevented VEGF from enhancing endothelial cell tube formation in HUVECs (Fig. 11D). CAGE was necessary for blood vessel formation according to aortic ring formation assays (Fig. 11E). Taken together, these results suggest that CAGE is induced by VEGF and mediates the VEGF-promoted angiogenesis.

FIGURE 11.

CAGE mediates VEGF-promoted angiogenesis. A, HUVECs were incubated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for various time intervals (upper panel), or HUVECs were incubated with various concentrations of VEGF for 1 h (lower panel). Prepared cell lysates were then subjected to Western blot analysis. B, HUVECs were treated with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for various time intervals. Total RNAs were isolated, and Northern blot analysis was performed. C, HUVECs were preincubated with IgG (4 μg/ml) or AVASTIN (4 μg/ml) for 4 h. Cells were then incubated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 1 h, followed by Western blot analysis. D, HUVECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (10 nm) or CAGE siRNA (10 nm). 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. Endothelial cell tube formation assays were performed as described (upper panel). HUVECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (10 nm) or CAGE siRNA (10 nm). At 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with various concentrations of VEGF for 1 h, followed by Western blot analysis (lower panel). Data are expressed as a mean ± S.D. E, HUVECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (10 nm) or CAGE siRNA (10 nm). 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 10 h. Conditioned medium (C.M.) was obtained and subjected to rat aortic ring formation assays as described. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.0005.

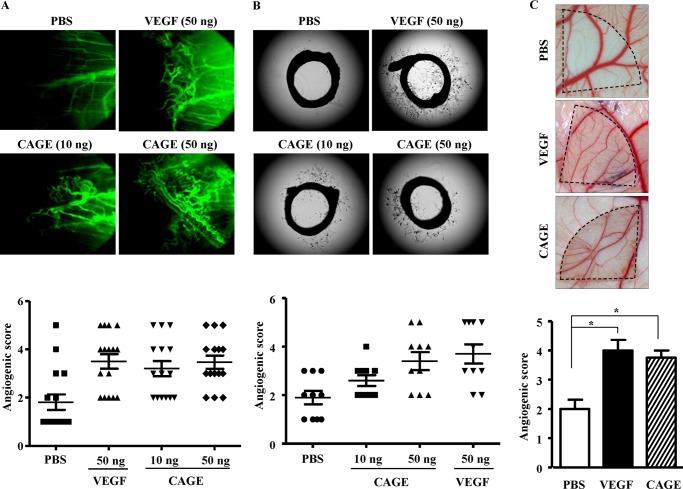

Recombinant CAGE Protein Displays Angiogenic Potential

CAGE is present in the sera of patients with various cancers (1, 3, 4). The conditioned medium of HUVECs treated with VEGF shows the expression of CAGE.4 This led to the hypothesis that CAGE might be a secreted protein. The direct role of CAGE in angiogenesis was therefore assessed. Recombinant CAGE protein was mixed with Matrigel and injected intradermally into the back of a BALB/c mouse. VEGF and recombinant CAGE protein enhanced blood vessel formation, as evidenced by intravital microscopy (Fig. 12A). Rat aortic ring formation assays also showed blood vessel formation by recombinant CAGE protein (Fig. 12B). Recombinant CAGE protein enhanced blood vessel formation in CAM assays (Fig. 12C). These results suggest that CAGE is an angiogenic factor.

FIGURE 12.

CAGE promotes angiogenesis. A, indicated amount of human recombinant CAGE protein or recombinant VEGF protein was mixed with Matrigel. Four days later, FITC-dextran was injected via the tail vein to visualize blood vessel formation. Each figure shows a representative example of three independent experiments. Angiogenic scores were obtained by performing three independent experiments. Intravital microscopy analysis was conducted as described. B, indicated amount of recombinant CAGE or VEGF protein was added to rat aorta. After 6 days, the extent of microvessel sprouting was determined using an inverted microscope (magnification, ×100; Olympus). Photographs are representative of endothelial cell sprouts formed from the margins of vessel segments. Angiogenic scores were obtained by performing three independent experiments. C, CAM assays were performed. In brief, salt-free solution (10 μl) containing recombinant VEGF (20 ng/ml) or recombinant CAGE protein (20 ng/ml) was applied to Thermanox discs. Data are expressed as a mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

miR-200b is involved in resistance to taxol (14) and EGFR therapy (15). It was reported that the expression level of pEGFRY845 was increased in SNU387R and Malme3MR cells (6). It is probable that miR-200b has a negative effect on the activation of EGFR in cancer cell lines resistant to the microtubule-targeting drugs employed in this study. SNU387R and Malme3MR cells show resistance to EGFR inhibitors such as cetuximab and iressa.4 The down-regulation of CAGE leads to the enhanced sensitivity of SNU387R and Malme3MR cells to cetuximab and iressa.4 This suggests the involvement of miR-200b and CAGE in response to EGFR therapy, in addition to the response to microtubule-targeting drugs. It will be interesting to examine the effect of EGFR signaling on the expression of miR-200b and CAGE in cancer cell lines.

miR-200b regulates chemotherapy-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human tongue cancer cells by targeting BMI1 (12). miR-200b inhibits TGFβ1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (38). Smad3 binds to the Smad-binding element in the promoter sequences of miR-200b to regulate the expression of miR-200b at the transcriptional level (17). This suggests a feedback regulatory loop between miR-200b and TGFβ1 signaling. It is therefore reasonable that CAGE may affect TGFβ1 signaling. In this study, it was shown that CAGE acts as a negative regulator of miR-200b and binds to the promoter sequences of miR-200b. It was found that the down-regulation of CAGE leads to the decreased expression of pSmad2Ser-456/467 and pSmad3Ser-208 in SNU387R and Malme3MR cells.4 This suggests a close relationship between TGFβ signaling and CAGE. It may be necessary to examine the possible interaction between CAGE and Smad2/3.

The expression of miR-200b is epigenetically regulated (39). miR-200b promoter contains a binding site for HDAC2, and ChIP assays show the binding of HDAC2 to the promoter sequences of miR-200b in Malme3MR cells (Fig. 7F). This suggests that CAGE regulates the expression of miR-200b through interaction with HDAC2. The expression of CAGE is epigenetically regulated (5). DNMT1 acts as a negative regulator of CAGE expression (6). miR-152 directly down-regulates DNMT1 expression by targeting the 3′-untranslated regions of its transcript in nickel sulfide (NiS)-transformed human bronchial epithelial cells (40). It will be interesting to examine the effect of miR-152 on the expression of miR-200b and CAGE. It is probable that the expression of miR-152 is increased in cancer cell lines that are resistant to microtubule-targeting drugs and increases the expression of CAGE. miR-200b promoter contains a binding site for SP1 (Fig. 7E). The expression of SP1 is increased in SNU387R and Malme3MR cells.4 It will be interesting to examine the effect of SP1 on the expression of miR-200b and the possible interaction between CAGE and SP1.

miR-200b regulates VEGF signaling and angiogenesis (22, 41). miR-200b negatively regulates the expression of VEGF and PAI-1 (Fig. 9A). Cytokine array analysis shows that the down-regulation of CAGE leads to the decreased expression of angiogenic factors such as PAI-1, MCP1, GRO1-α, and sICAM-1 (Fig. 10A). Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1(MCP1) is involved in cathepsin G-promoted enhanced TGFβ signaling during angiogenesis (43). Growth-regulated oncogene 1-α (GRO1-α) is associated with angiogenesis and lymph node metastasis (44). Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (sICAM1) promotes angiogenesis (45). It will be necessary to examine the relationship between miR-200b and these cytokines. There have been few studies on cancer/testis antigens in relation to angiogenesis, if any. MAGE-11 activates a hypoxic response by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylase 2 (46). MAGE-D1 inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo (47).

We show that CAGE mediates VEGF-promoted angiogenesis (Fig. 11, D and E). VEGF increases the expression of HDAC2 in HUVECs.4 It is therefore reasonable that CAGE may mediate VEGF-promoted angiogenesis through interaction with HDAC2. It will be interesting to examine the role of HDAC2 in angiogenesis.

Human recombinant CAGE protein induces blood vessel formation (Fig. 12, A–C). The identification of receptor that interacts with CAGE is necessary for understanding CAGE-promoted angiogenesis. Interaction pathway analysis suggests the interaction between CAGE and EGFR. It will be necessary to examine the role of EGFR in CAGE-promoted angiogenesis and the interaction between CAGE and EGFR.

Because miRNAs have the potential to repress the mRNAs that encode transcription factors, which repress the same miRNAs, miRNAs are well suited to take part in the feedback regulatory loop. miRNAs regulate their own expression through feedback loops (48). miR-22 is up-regulated by Akt and down-regulates PTEN levels (49). A feedback regulatory loop exists between miR-195 and MBD1 in neural stem cell differentiation (50). Just like the miR-200b-CAGE feedback regulatory loop, MBD1 and miR-195 have been revealed to directly regulate each other. A feedback regulatory loop exists between miR-17 and cyclin D1 in breast cancer cell proliferation (51). miR-200b regulates the expression of cyclin D1 (52). CAGE regulates the expression of cyclin D1 in an AP1- and E2F-dependent manner (7). Because cyclin D1 has served as a common target for miR-200b and CAGE, it was hypothesized that there would be a feedback regulatory loop between miR-200b and CAGE.

Target scan analysis predicts the binding of miR-153 to 3′-UTR of CAGE. miR-153 is down-regulated in cells that have undergone EMT by TGFβ and inhibits tumor metastasis and EMT by targeting SNAI1 and ZEB2 (42). It will be interesting to examine the role of miR-153 in angiogenesis, invasion, and the response to microtubule-targeting drugs in relation to CAGE. Target scan analysis also predicts the binding of miR-145, -448, -217, -429, and -186 to the promoter sequences of CAGE. It will be interesting to examine the relationship between these miRNAs and the miR-200b-CAGE feedback regulatory loop. Some of these miRNAs may repress the expression of CAGE, which in turn up-regulates the expression of miR-200b in the drug-resistant cancer cell lines employed in this study.

In conclusion, it has been shown that miR-200b and CAGE form a feedback regulatory loop and regulate the response to microtubule-targeting drugs, as well as the invasion, tumorigenic potential, and angiogenic potential.

This work was supported by National Research Foundation Grants 2010-0021357, 2011-0010867, 2012H1B8A2025495, and C1008749-01-01 and by National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea Grant 1320160.

D. Jeoung, personal observations.

- CAGE

- cancer-associated gene

- CAM

- chick chorioallantoic membrane

- EMT

- epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- miR-200b

- microRNA-200b

- PAI-1

- plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real time PCR

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- DIG

- digoxigenin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cho B., Lim Y., Lee D. Y., Park S. Y., Lee H., Kim W. H., Yang H., Bang Y. J., Jeoung D. I. (2002) Identification and characterization of a novel cancer/testis antigen gene CAGE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292, 715–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shim E., Shim H., Bae J., Lee H., Jeoung D. (2006) CAGE displays oncogenic potential and induces cytolytic T lymphocyte activity. Biotechnol. Lett. 28, 515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iwata T., Fujita T., Hirao N., Matsuzaki Y., Okada T., Mochimaru H., Susumu N., Matsumoto E., Sugano K., Yamashita N., Nozawa S., Kawakami Y. (2005) Frequent immune responses to a cancer/testis antigen, CAGE, in patients with microsatellite instability-positive endometrial cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 3949–3957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liggins A. P., Lim S. H., Soilleux E. J., Pulford K., Banham A. H. (2010) A panel of cancer-testis genes exhibiting broad-spectrum expression in haematological malignancies. Cancer Immun. 10, 8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cho B., Lee H., Jeong S., Bang Y. J., Lee H. J., Hwang K. S., Kim H. Y., Lee Y. S., Kang G. H., Jeoung D. I. (2003) Promoter hypomethylation of a novel cancer/testis antigen gene CAGE is correlated with its aberrant expression and is seen in premalignant stage of gastric carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 52–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim Y., Park H., Park D., Lee Y. S., Choe J., Hahn J. H., Lee H., Kim Y. M., Jeoung D. (2010) Cancer/testis antigen CAGE exerts negative regulation on p53 expression through HDAC2 and confers resistance to anti-cancer drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25957–25968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Por E., Byun H. J., Lee E. J., Lim J. H., Jung S. Y., Park I., Kim Y. M., Jeoung D. I., Lee H. (2010) The cancer/testis antigen CAGE with oncogenic potential stimulates cell proliferation by up-regulating cyclins D1 and E in an AP-1- and E2F-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14475–14485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Calin G. A., Croce C. M. (2006) MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 857–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng W., Liu T., Wan X., Gao Y., Wang H. (2012) MicroRNA-199a targets CD44 to suppress the tumorigenicity and multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer-initiating cells. FEBS J. 279, 2047–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yoshino H., Enokida H., Itesako T., Tatarano S., Kinoshita T., Fuse M., Kojima S., Nakagawa M., Seki N. (2013) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related microRNA-200s regulate molecular targets and pathways in renal cell carcinoma. J. Hum. Genet. 58, 508–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rui W., Bing F., Hai-Zhu S., Wei D., Long-Bang C. (2010) Identification of microRNA profiles in docetaxel-resistant human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells (SPC-A1). J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14, 206–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sun L., Yao Y., Liu B., Lin Z., Lin L., Yang M., Zhang W., Chen W., Pan C., Liu Q., Song E., Li J. (2012) miR-200b and miR-15b regulate chemotherapy-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human tongue cancer cells by targeting BMI1. Oncogene 31, 432–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li Y., VandenBoom T. G., 2nd, Kong D., Wang Z., Ali S., Philip P. A., Sarkar F. H. (2009) Up-regulation of miR-200 and let-7 by natural agents leads to the reversal of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69, 6704–6712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feng B., Wang R., Song H. Z., Chen L. B. (2012) MicroRNA-200b reverses chemoresistance of docetaxel-resistant human lung adenocarcinoma cells by targeting E2F3. Cancer 118, 3365–3376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adam L., Zhong M, Choi W., Qi W., Nicoloso M., Arora A., Calin G., Wang H., Siefker-Radtke A., McConkey D., Bar-Eli M., Dinney C. (2009) miR-200 expression regulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in bladder cancer cells and reverses resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 5060–5072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bao B., Wang Z., Ali S., Kong D., Li Y., Ahmad A., Banerjee S., Azmi A. S., Miele L., Sarkar F. H. (2011) Notch-1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition consistent with cancer stem cell phenotype in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 307, 26–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17. Ahn S. M., Cha J. Y., Kim J., Kim D., Trang H. T., Kim Y. M., Cho Y. H., Park D., Hong S. (2012) Smad3 regulates E-cadherin via miRNA-200 pathway. Oncogene 31, 3051–3059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gregory P. A., Bert A. G., Paterson E. L., Barry S. C., Tsykin A., Farshid G., Vadas M. A., Khew-Goodall Y., Goodall G. J. (2008) The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bai J. X., Yan B., Zhao Z. N., Xiao X., Qin W. W., Zhang R., Jia L. T., Meng Y. L., Jin B. Q., Fan D. M., Wang T., Yang A. G. (2013) Tamoxifen represses miR-200 microRNAs and promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by up-regulating c-Myc in endometrial carcinoma cell lines. Endocrinology 154, 635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alaiti M. A., Ishikawa M., Masuda H., Simon D. I., Jain M. K., Asahara T., Costa M. A. (2012) Up-regulation of miR-210 by vascular endothelial growth factor in ex vivo expanded CD34+ cells enhances cell-mediated angiogenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 16, 2413–2421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang J., Wang Y., Wang Y., Ma Y., Lan Y., Yang X. (2013) Transforming growth factor β-regulated microRNA-29a promotes angiogenesis through targeting the phosphatase and tensin homolog in endothelium. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10418–10426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang S. H., Lu Y. C., Li X., Hsieh W. Y., Xiong Y., Ghosh M., Evans T., Elemento O., Hla T. (2013) Antagonistic function of the RNA-binding protein HuR and miR-200b in post-transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-A expression and angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 4908–4921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takahashi Y., Koyanagi T., Suzuki Y., Saga Y., Kanomata N., Moriya T., Suzuki M., Sato Y. (2012) Vasohibin-2 expressed in human serous ovarian adenocarcinoma accelerates tumor growth by promoting angiogenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 10, 1135–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McArthur K., Feng B., Wu Y., Chen S., Chakrabarti S. (2011) MicroRNA-200b regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated alterations in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 60, 1314–1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chan Y. C., Roy S., Khanna S., Sen C. K. (2012) Down-regulation of endothelial microRNA-200b supports cutaneous wound angiogenesis by desilencing GATA binding protein 2 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 1372–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan Y. C., Khanna S., Roy S., Sen C. K. (2011) miR-200b targets Ets-1 and is down-regulated by hypoxia to induce angiogenic response of endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2047–2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kavallaris M., Kuo D. Y., Burkhart C. A., Regl D. L., Norris M. D., Haber M., Horwitz S. B. (1997) Taxol-resistant epithelial ovarian tumors are associated with altered expression of specific β-tubulin isotypes. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 1282–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ahmad A., Aboukameel A., Kong D., Wang Z., Sethi S., Chen W., Sarkar F. H., Raz A. (2011) Phosphoglucose isomerase/autocrine motility factor mediates epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulated by miR-200 in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 71, 3400–3409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tong Z. T., Cai M. Y., Wang X. G., Kong L. L., Mai S. J., Liu Y. H., Zhang H. B., Liao Y. J., Zheng F., Zhu W., Liu T. H., Bian X. W., Guan X. Y., Lin M. C., Zeng M. S., Zeng Y. X., Kung H. F., Xie D. (2012) EZH2 supports nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell aggressiveness by forming a co-repressor complex with HDAC1/HDAC2 and Snail to inhibit E-cadherin. Oncogene 31, 583–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glenn D. J., Wang F., Chen S., Nishimoto M., Gardner D. G. (2009) Endothelin-stimulated human B-type natriuretic peptide gene expression is mediated by Yin Yang 1 in association with histone deacetylase 2. Hypertension 53, 549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zolova O. E., Wight P. A. (2011) YY1 negatively regulates mouse myelin proteolipid protein (Plp1) gene expression in oligodendroglial cells. ASN Neuro 3, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu L., Zhou L., Chen E. Z., Sun K., Jiang P., Wang L., Su X., Sun H., Wang H. (2012) A novel YY1-miR-1 regulatory circuit in skeletal myogenesis revealed by genome-wide prediction of YY1-miRNA network. PLoS One 7, e27596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim T., Veronese A., Pichiorri F., Lee T. J., Jeon Y.-J., Volinia S., Pineau P., Marchio A., Palatini J., Suh S.-S., Alder H., Liu C.-G., Dejean A., Croce C. M. (2011) p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through microRNAs targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2. J. Exp. Med. 208, 875–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Basu A., Menicucci G., Maestas J., Das A., McGuire P. (2009) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) facilitates retinal angiogenesis in a model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 4974–4981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Teng H., Chopp M., Hozeska-Solgot A., Shen L., Lu M., Tang C., Zhang Z. G. (2012) Tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 contribute to sonic hedgehog-induced in vitro cerebral angiogenesis. PLoS One 7, e33444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Olofsson B., Korpelainen E., Pepper M. S., Mandriota S. J., Aase K., Kumar V., Gunji Y., Jeltsch M. M., Shibuya M., Alitalo K., Eriksson U. (1998) Vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGF-B) binds to VEGF receptor-1 and regulates plasminogen activator activity in endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 11709–11714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jung S. Y., Song H. S., Park S. Y., Chung S. H., Kim Y. J. (2011) Pyruvate promotes tumor angiogenesis through HIF-1-dependent PAI-1 expression. Int. J. Oncol. 38, 571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen Y., Xiao Y., Ge W., Zhou K., Wen J., Yan W., Wang Y., Wang B., Qu C., Wu J., Xu L., Cai W. (2013) miR-200b inhibits TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes growth of intestinal epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 4, e541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li A., Omura N., Hong S. M., Vincent A., Walter K., Griffith M., Borges M., Goggins M. (2010) Pancreatic cancers epigenetically silence SIP1 and hypomethylate and overexpress miR-200a/200b in association with elevated circulating miR-200a and miR-200b levels. Cancer Res. 70, 5226–5237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ji W., Yang L., Yuan J., Yang L., Zhang M., Qi D., Duan X., Xuan A., Zhang W., Lu J., Zhuang Z., Zeng G. (2013) MicroRNA-152 targets DNA methyltransferase 1 in NiS-transformed cells via a feedback mechanism. Carcinogenesis 34, 446–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choi Y. C., Yoon S., Jeong Y., Yoon J., Baek K. (2011) Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling by miR-200b. Mol. Cells 32, 77–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu Q., Sun Q., Zhang J., Yu J., Chen W., Zhang Z. (2013) Down-regulation of miR-153 contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis in human epithelial cancer. Carcinogenesis 34, 539–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wilson T. J., Nannuru K. C., Futakuchi M., Singh R. K. (2010) Cathepsin G-mediated enhanced TGF-β signaling promotes angiogenesis via upregulation of VEGF and MCP-1. Cancer Lett. 288, 162–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shintani S., Ishikawa T., Nonaka T., Li C., Nakashiro K., Wong D. T., Hamakawa H. (2004) Growth-regulated oncogene-1 expression is associated with angiogenesis and lymph node metastasis in human oral cancer. Oncology 66, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gho Y. S., Kleinman H. K., Sosne G. (1999) Angiogenic activity of human soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Cancer Res. 59, 5128–5132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Aprelikova O., Pandolfi S., Tackett S., Ferreira M., Salnikow K., Ward Y., Risinger J. I., Barrett J. C., Niederhuber J. (2009) Melanoma antigen-11 inhibits the hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase 2 and activates hypoxic response. Cancer Res. 69, 616–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shen W. G., Xue Q. Y., Zhu J., Hu B. S., Zhang Y., Wu Y. D., Su Q. (2007) Inhibition of adenovirus-mediated human MAGE-D1 on angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell Biochem. 300, 89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim J., Inoue K., Ishii J., Vanti W. B., Voronov S. V., Murchison E., Hannon G., Abeliovich A. (2007) A microRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science 317, 1220–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bar N., Dikstein R. (2010) miR-22 forms a regulatory loop in PTEN/AKT pathway and modulates signaling kinetics. PLoS One 5, e10859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu C., Teng Z. Q., McQuate A. L., Jobe E. M., Christ C. C., von Hoyningen-Huene S. J., Reyes M. D., Polich E. D., Xing Y., Li Y., Guo W., Zhao X. (2013) An epigenetic feedback regulatory loop involving microRNA-195 and MBD1 governs neural stem cell differentiation. PLoS One 8, 51436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yu Z., Wang C., Wang M., Li Z., Casimiro M. C., Liu M., Wu K., Whittle J., Ju X., Hyslop T., McCue P., Pestell R. G. (2008) A cyclin D1/microRNA 17/20 regulatory feedback loop in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 182, 509–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xia W., Li J., Chen L., Huang B., Li S., Yang G., Ding H., Wang F., Liu N., Zhao Q., Fang T., Song T., Wang T., Shao N. (2010) MicroRNA-200b regulates cyclin D1 expression and promotes S-phase entry by targeting RND3 in HeLa cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 344, 261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]