Background: We sought to engineer highly efficacious agents that neutralize ricin toxin.

Results: We identified monomeric single-chain camelid VH domains (VHHs) capable of neutralizing ricin in vitro and engineered heterodimeric VHHs that neutralized ricin in vivo.

Conclusion: Stepwise engineering of VHHs resulted in highly potent ricin toxin-neutralizing antibodies.

Significance: This study highlights the potential use of a VHH platform as a strategy for therapeutics against diverse biological toxins.

Keywords: Antibody Engineering, Immunology, Immunotherapy, Mouse, Toxins, VHH

Abstract

In an effort to engineer countermeasures for the category B toxin ricin, we produced and characterized a collection of epitopic tagged, heavy chain-only antibody VH domains (VHHs) specific for the ricin enzymatic (RTA) and binding (RTB) subunits. Among the 20 unique ricin-specific VHHs we identified, six had toxin-neutralizing activity: five specific for RTA and one specific for RTB. Three neutralizing RTA-specific VHHs were each linked via a short peptide spacer to the sole neutralizing anti-RTB VHH to create VHH “heterodimers.” As compared with equimolar concentrations of their respective monovalent monomers, all three VHH heterodimers had higher affinities for ricin and, in the case of heterodimer D10/B7, a 6-fold increase in in vitro toxin-neutralizing activity. When passively administered to mice at a 4:1 heterodimer:toxin ratio, D10/B7 conferred 100% survival in response to a 10 × LD50 ricin challenge, whereas a 2:1 heterodimer:toxin ratio conferred 20% survival. However, complete survival was achievable when the low dose of D10/B7 was combined with an IgG1 anti-epitopic tag monoclonal antibody, possibly because decorating the toxin with up to four IgGs promoted serum clearance. The two additional ricin-specific heterodimers, when tested in vivo, provided equal or greater passive protection than D10/B7, thereby warranting further investigation of all three heterodimers as possible therapeutics.

Introduction

Ricin, a 65-kDa glycoprotein found in the seeds of the castor bean plant, is a member of the A-B family of protein toxins, which includes cholera toxin, Shiga toxins 1 (Stx1)3 and 2 (Stx2), botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), and anthrax toxin (1, 2). The ricin B subunit (RTB) is a galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine (Gal/GalNAc) lectin that promotes toxin attachment and entry into all mammalian cell types (3, 4). Following endocytosis, RTB mediates the retrograde trafficking of ricin from the plasma membrane to the trans-Golgi network and the endoplasmic reticulum. Once in the endoplasmic reticulum, the ricin A subunit (RTA) is liberated from RTB and is dislocated across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane into the cytoplasm, where it functions as an RNA N-glycosidase whose sole substrate is a universally conserved adenosine residue within the so-called sarcin/ricin loop of mammalian rRNA (5). Hydrolysis of the sarcin/ricin loop by RTA results in the cessation of cellular protein synthesis, activation of the ribotoxic stress response, and cell death via apoptosis (6).

Ricin, a category B toxin, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is extremely toxic in purified or semipurified forms by injection, inhalation, or ingestion (7–9). Recent high profile incidents involving ricin-laden envelopes addressed to members of the United States Congress and the President have accelerated efforts by the Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health to develop countermeasures against the toxin (10, 11). We and others have produced a large collection of RTA- and RTB-specific murine and chimeric mouse-human mAbs with toxin-neutralizing activity in vitro and in vivo (1, 12–16). Although many of these mAbs have therapeutic potential, funding agencies are increasing moving away from the “one bug, one drug” model of biodefense therapeutics to more broad-based platform technologies that can provide rapid onset against similarly acting biothreat agents.

Camelids produce a class of heavy chain-only antibodies which bind antigen strictly through their VH domain. Recombinant heavy chain-only VH domains (VHHs) are conformationally stable, frequently bind to active site pockets, and have excellent commercial properties (17–20). Additionally, monomeric VHHs can be genetically linked to express heteromultimeric binding agents with improved properties (21, 22). We previously reported a novel antitoxin strategy that promotes both toxin neutralization and serum clearance with two simple protein components (21). One component is a VHH heterodimer consisting of two toxin-neutralizing VHHs recognizing nonoverlapping epitopes. The linked VHHs lead to enhanced neutralization properties compared with the VHH monomers (22). In addition to toxin neutralization, the VHH heterodimers can promote toxin clearance from serum by co-administration of an effector antibody (efAb), which is an anti-tag mAb that recognizes two peptide tags separately engineered into sites flanking the VHH heterodimer. The efAb can bind at the two sites on each VHH heterodimer, which itself binds the toxin at two sites, thus resulting in toxin decoration with up to four Abs to promote serum clearance (21, 23), presumably by Fc receptor-mediated processes.

In this study, we produced and characterized a collection toxin-neutralizing and non-neutralizing VHHs specific for the enzymatic and receptor binding subunits of ricin. We next engineered VHH heterodimers consisting of pairs of VHH monomers and demonstrate their potential, in the absence and presence of efAb, to confer immunity to ricin in a mouse model. We demonstrate the capacity to stepwise engineer heterodimers with increased affinity and toxin-neutralizing activity and the significant boost in potency that efAb confers on passive protection in vivo. In light of our recent success in developing VHH antibodies against BoNT and Stx, we propose that this antitoxin technology platform may have important applications for biodefense.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Toxins, Chemicals, and Reagents

Ricin toxin (RCA-II), RTA, and RTB were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). A recombinant, attenuated form of the ricin toxin A subunit, known as RiVaxTM, was kindly provided by Dr. Robert Brey (Soligenix, Inc., Princeton, NJ) (24). Anti-E tag mAb was obtained from Phadia (Uppsala, Sweden), whereas HRP anti-E-tag mAb and HRP anti-M13 antibody were purchased from GE Healthcare. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless noted otherwise.

Ethics Statement

Studies involving the use of animals were carried out in strict accordance with recommendations from the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Institutes of Health. Studies involving alpacas were conducted at Tufts University and were approved by the Tufts University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All procedures involving mice were conducted at the Wadsworth Center and approved by the Wadsworth Center's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Alpaca Immunizations and VHH Display Library Preparation

A total of two alpacas (Vicugna pacos) were used in this study. One alpaca received five successive multisite subcutaneous injections at 3-week intervals using an immunogen consisting of RiVax (100 μg) and RTB (100 μg), followed by three additional immunizations with RiVax (200 μg) and ricin toxoid (200 μg) and then two immunizations with RiVax (200 μg), RTB (100 μg), and ricin toxoid (200 μg). RiVax was preadsorbed to aluminum salts adjuvant, whereas RTB was combined with alum/CpG adjuvant immediately prior to injection. The second alpaca received three immunizations of ricin toxoid (200 μg) and then two immunizations with RiVax (200 μg), RTB (100 μg), and ricin toxoid (200 μg). Following the final immunizations, animals had end point RTA- and RTB-specific serum IgG titers between 5 × 104 and 5 × 105 and ricin neutralization titers between 1,600 and 3,200. Three days following the final boost, blood was obtained for lymphocyte preparation, and a VHH display phage library was prepared from the immunized alpaca as previously described (21, 25, 26). 4 × 106 independent clones (>95% with VHH inserts) were prepared from B cells of the two alpacas and pooled to create the library.

Anti-RTA and anti-RTB VHH Identification, Expression, and Purification

Panning, phage recovery, and clone fingerprinting were performed essentially as described (21). Two rounds of panning were performed on purified RTA or RTB targets coated onto Nunc Immunotubes. A single low stringency panning using 10 μg/ml target antigen was performed on each subunit target. After phages were eluted, they were amplified and subjected to a second round of panning at high stringency with 1 μg/ml target antigen. Following the second round of panning, ∼150 individual Escherichia coli colonies were picked and grown overnight at 37 °C in 96-well plates. A replica plate was then prepared, cultured, and induced with IPTG, and the supernatant was assayed for RTA or RTB binding by ELISA.

For each two-cycle panning regimen, >50% of VHH clones bound to RTA or RTB, as evidenced by ELISA reactivity values that were >2-fold over negative controls. Approximately 60 of the strongest positive binding phage for RTA and RTB were selected for DNA sequence analysis (“fingerprinting”). Sixteen clones with unique DNA fingerprints were identified among the VHHs selected as strong positives for RTA binding, and nine unique clones for VHHs were selected as positives for RTB binding. The VHH coding DNAs from these clones were sequenced and analyzed by phylogenetic tree analysis to identify closely related VHHs likely to have common B cell clonal origins. Based on this analysis, eleven RTA-binding VHHs and nine RTB-binding VHHs were selected for protein expression.

We have previously described the protocols used for purification of VHHs from E. coli as recombinant thioredoxin fusion proteins containing N-terminal hexahistidine and C-terminal E epitope tag (GAPVPYPDPLEPR) (26) and for competition analysis to identify VHH binding to common or overlapping epitopes (21). Heterodimeric VHHs were engineered to contain a flexible spacer (GGGGS × 3) between the two VHH monomers and two copies of E-tag flanking the VHH heterodimer (21).

ELISA

Nunc-Immuno plates (ThermoScientific, Swedesboro, NJ) were coated overnight at 4 °C with 1 μg/ml target antigen (e.g., ricin), blocked for 2 h with 2% BSA in PBS, and then incubated for 1 h with 2-fold serial dilutions of VHHs. For competition assays, murine IgGs (10 μg/ml) were added to the ELISA plate wells 1 h prior to the addition of the VHHs (1 μg/ml). The plates were then washed with 0.1% PBS-T and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-E tag secondary antibody (1:10,000) for 1 h. The plates were developed with SureBlue Peroxidase Substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). The reaction was quenched with 1 m phosphoric acid, and absorbance was read at 450 nm using a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

VHH Affinity Determinations

Affinity of VHHs for ricin toxin was determined by surface plasmon resonance SPR using a Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare) instrument, as described previously (16). Ricin was attached to a CM5 chip at a density of 550–650 resonance units. HEPES-buffered saline with EDTA and surfactant P20 (HBS-EP; 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 3.4 mm EDTA, 0.005% of the surfactant P20 from GE Healthcare) was employed as the running buffer at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. Serial dilutions of each antibody were made in HBS-EP, pH 7.4, from 600 to 18.75 nm, with each concentration series having at least one cycle of a buffer-alone injection. Injection times were 3–4 min with dissociation times of 10 min. Regeneration of the chip surface was performed at a flow rate of 50 μl/min by two 30-s pulses of 10 mm glycine, pH 1.5. The regeneration was followed by a 2-min stabilization period. All kinetic experiments were run a 25 °C. Kinetic constants were obtained by analysis using the BIA evaluation software.

Vero Cell Cytotoxicity Assays

The Vero cell cytotoxicity assay has been described in detail elsewhere (27). Vero cells grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS were seeded (1 × 104 cells/well) in 96-well cell culture plates and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The cells were then overlaid with ricin (10 ng/ml, 150 pm) in the absence or presence of 5-fold serial dilutions of monomeric or heterodimeric VHHs and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The cells were then washed, and fresh medium was applied. Cell viability was assessed 45–48 h later using CellTiter-Glo (Promega, Madison, WI).

Passive Protection Studies in Mice

Female BALB/c mice aged 8–10 weeks (Taconic Laboratories, Hudson, NY) were separated into groups of five and allowed to acclimate to their surroundings for 1 week prior to initiation of an experiment. Mixtures of ricin (2 μg; 30 pmol; 10 × LD50) and VHH monomers or heterodimers, with or without the anti-E efAb (2:1 efAb:heterodimer ratio), were mixed at defined ratios in sterile PBS to a final volume of 400 ml. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 1 h and then administered to mice by intraperitoneal injection. Hypoglycemia was used as a surrogate marker of ricin intoxication (28, 29). Blood (∼5 μl) was collected from the tail veins of mice just prior to ricin challenge (time 0) and at 24-h intervals thereafter. Blood glucose levels were measured with an Aviva ACCU-CHEK handheld blood glucose meter (Roche Applied Science). Survival following toxin challenge was monitored for up to 14 days, and animals surviving beyond day 14 were considered fully protected. The mice were euthanized when they became overtly moribund and/or blood glucose levels fell below 20 mg/dl. Statistical differences in survival were tested by the Mantel-Cox test, computed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0).

RESULTS

Identification of RTA- and RTB-specific VHHs with Ricin Toxin-neutralizing Activity

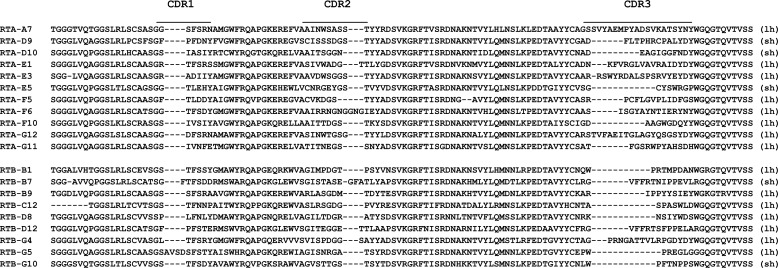

We prepared a VHH-displayed phage library representing the repertoires of two alpacas that were repeatedly immunized with ricin toxin subunit antigens and then boosted with ricin toxoid (see “Materials and Methods”). The VHH-displayed phage library was subjected to rounds of high and low stringency panning on purified RTA or RTB subunits. Ultimately, we identified 25 different phagemids encoding VHHs with RTA or RTB binding activity that were then subjected to DNA sequencing as a means to determine their relatedness. Of the 25 VHHs, there were 11 apparently unrelated RTA-specific VHHs and 9 unrelated RTB-specific VHHs (Table 1 and Fig. 1). All 20 unique VHHs were expressed and purified from E. coli as E-tagged thioredoxin fusion proteins.

TABLE 1.

Nomenclature of VHHs

| VHH | Protein | Clone | GenBankTM accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| RTA-F5 | JIV-F5 | JJS-17 | KF746018 |

| RTA-F6 | JIV-F6 | JJS-20 | KF746019 |

| RTA-G12 | JIV-G12 | JJS-21 | KF746020 |

| RTA-A7 | JIY-A7 | JJS-24 | KF746021 |

| RTA-D9 | JIY-D9 | JJS-25 | KF746022 |

| RTA-D10 | JIY-D10 | JJS-27 | KF746023 |

| RTA-E1 | JIY-E1 | JJS-29 | KF746024 |

| RTA-E3 | JIY-E3 | JJS-31 | KF746025 |

| RTA-E5 | JIY-E5 | JJS-33 | KF746026 |

| RTA-F10 | JIY-F10 | JJS-35 | KF746027 |

| RTA-G11 | JIY-G11 | JJS-37 | KF746028 |

| RTB-B1 | JIW-B1 | JJS-40 | KF746029 |

| RTB-C12 | JIW-C12 | JJS-41 | KF746030 |

| RTB-D12 | JIW-D12 | JJS-43 | KF746031 |

| RTB-G5 | JIW-G5 | JJS-45 | KF746032 |

| RTB-G10 | JIW-G10 | JJS-48 | KF746033 |

| RTB-B7 | JIZ-B7 | JJS-50 | KF746034 |

| RTB-B9 | JIZ-B9 | JJS-51 | KF746035 |

| RTB-D8 | JIZ-D8 | JJS-54 | KF746036 |

| RTB-G4 | JIZ-G4 | JJS-56 | KF746037 |

FIGURE 1.

Amino acid sequences of the VHH variable regions. Amino acid sequences of RTA-specific (top) and RTB-specific (bottom) VHHs are shown. Complementary determining regions (CDR) 1, 2, and 3 are indicated by the horizontal lines, and the presence of a short (sh) or long (lh) hinge is indicated in the right margin. GenBankTM accession numbers for the VHH sequences are indicated in Table 1.

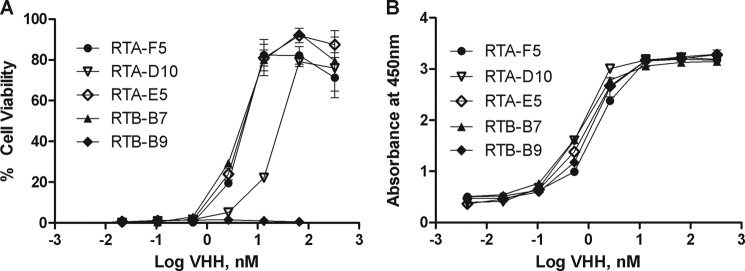

The 20 unique VHHs were tested in a Vero cell cytotoxicity assay for the ability to neutralize ricin. Five RTA-specific VHHs (RTA-F5, RTA-G12, RTA-D10, RTA-E5, and RTA-G11) and one RTB-specific VHH (RTB-B7) demonstrated a dose-dependent capacity to protect Vero cells from ricin-induced cytotoxicity (Table 2 and Fig. 2A). Three VHHs (RTA-F5, RTA-E5, and RTB-B7) had estimated IC50 values of ∼5 nm, (∼30:1 molar ratio VHH:ricin), one (RTA-D10) had an IC50 of ∼25 nm (∼150:1 VHH:ricin), and two (RTA-G12 and RTA-G11) had IC50 values of >90 nm. The remaining 14 VHHs had no detectable neutralizing activity, even at 330 nm (∼2,200:1 VHH:ricin).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of RTA- and RTB-specific VHHs

| VHHb | EC50c | Kd | IC50 | Competitive inhibition assaysa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB10 | SyH7 | IB2 | GD12 | ||||

| nm | nm | nm | |||||

| RTA-F5* | 1.50 | 2.24 | 5 | +++ | – | – | – |

| RTA-F6 | 1.00 | – | – | ++ | – | ||

| RTA-G12 | 0.50 | 0.62 | >330 | +++ | – | – | – |

| RTA-A7 | 1.20 | +++ | – | – | – | ||

| RTA-D9 | 3.30 | – | – | – | – | ||

| RTA-D10* | 0.66 | 0.63 | 25 | – | – | – | – |

| RTA-E1 | 3.00 | – | + | – | – | ||

| RTA-E3 | 2.00 | +++ | – | – | – | ||

| RTA-E5* | 0.83 | 1.94 | 5 | +++ | – | – | – |

| RTA-F10 | 13.20 | – | – | – | – | ||

| RTA-G11 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 90 | +++ | – | – | – |

| SylH3 | 24B11 | ||||||

| RTB-B1 | 4.10 | – | – | ||||

| RTB-C12 | 1.65 | – | – | ||||

| RTB-D12 | 0.83 | – | – | ||||

| RTB-G5* | 0.23 | – | – | ||||

| RTB-G10 | 1.65 | – | – | ||||

| RTB-B7* | 0.66 | 1.33 | 4 | – | – | ||

| RTB-B9* | 1.20 | – | – | ||||

| RTB-D8 | 3.63 | – | – | ||||

| RTB-G4 | 33.00 | – | – | ||||

a RTA- or RTB-specific murine mAbs were tested for capacity to prevent indicated VHHs binding to ricin in an ELISA format. The number of plus signs indicates the degree of relative inhibition (−, no reduction; +, 10–30% reduction; ++, 30–60% reduction; and +++, >60% reduction).

b Underlining indicates neutralizing VHHs. Asterisks indicate VHHs used in heterodimer formation.

c The values indicate the effective concentration of VHH required to achieve 50% maximal binding to ricin by ELISA.

FIGURE 2.

VHH toxin-neutralizing and binding activities. A, monomeric VHHs were tested for toxin-neutralizing activity in a Vero cell cytotoxicity assay, as described under “Materials and Methods.” VHHs (at indicated concentrations) were mixed with ricin (10 ng/ml) and applied to Vero cells in triplicate. Cell viability was assessed 48 h later. Shown is a representative experiment with error bars indicating S.D. B, to assess relative affinity of select VHHs for ricin, the VHHs (at indicated concentrations) were applied in duplicate to microtiter plates coated with ricin. The EC50 values are defined as the VHH concentration (nm) that achieved half-maximal binding. Shown is a representative experiment with error bars indicating S.D. The experiments described in A and B were replicated at least three times.

To determine the relationship between toxin-neutralizing activity and dissociation constants (KD), the six neutralizing VHHs were subjected to SPR analysis. All six VHHs had similar affinities for ricin, despite having varying degrees of toxin-neutralizing activity (Table 2). Furthermore, using dilution ELISA analysis, we compared the relative affinities of the neutralizing VHHs to those of the 14 non-neutralizing VHHs (Table 2 and Fig. 2B). This comparison revealed EC50 values ranging from 200 pm to 33 nm. Although the four most potent neutralizers (RTA-F5, RTA-D10, RTA-E5, and RTB-B7) were among the best ricin binders, the VHH with the highest relative affinity for ricin toxin was RTB-G5 (200 pm), a VHH with no detectable toxin-neutralizing activity. These data suggest that there is a certain threshold affinity required for toxin-neutralizing activity but that other factors like epitope specificity ultimately determine overall potency.

To determine whether any of the five RTA-specific neutralizing VHHs bind epitopes that overlap those recognized by previously identified neutralizing mouse mAbs PB10, SyH7, IB2, or GD12 (12, 30), we performed competitive ricin binding assays by ELISA. We found that VHHs RTA-F5, RTA-G12, RTA-E5, and RTA-G11 were inhibited by PB10, a mAb known to bind a solvent-exposed, immunodominant α-helix spanning residues 98–106 of RTA (31). RTA-D10, on the other hand, was not inhibited by any of the four murine mAbs tested and may therefore recognize a novel neutralizing epitope on RTA (Table 2).

We next examined whether mAbs 24B11 or SylH3 competitively inhibited RTB-B7 from binding to ricin. 24B11 and SylH3 are two well characterized RTB-specific toxin-neutralizing mAbs that are postulated to recognize epitopes on RTB subdomains 1α and 2γ, respectively (14, 16, 32). RTB-B7 binding to ricin by ELISA was unaffected by preincubation of the toxin with 24B11 or SylH3, indicating that RTB-B7 recognizes a previously unidentified neutralizing epitope on RTB (Table 2).

VHH Heterodimers Achieve Higher Affinity and Neutralizing Potency in Vitro

In the case of BoNT and Stx1 and Stx2, we have demonstrated that heterodimers created by covalently linking two different toxin-neutralizing VHH monomers resulted in bi-specific antibodies with increased toxin-specific affinities and improved toxin-neutralizing activities (21, 22). Therefore, we constructed three VHH heterodimers in which the RTB-specific neutralizing VHH, RTB-B7, was linked via the flexible peptide spacer (GGGGS)3 to each of the RTA-specific neutralizing VHHs, RTA-F5, RTA-D10, and RTA-E5; the resulting heterodimers are referred to as F5/B7, D10/B7, and E5/B7 (Table 3). In addition, we created two additional heterodimers. Heterodimer G5/B7 consists of RTB-B7 linked to RTB-G5 which is a high affinity, RTB-specific, non-neutralizing VHH. The second control heterodimer, G5/B9, consists of two anti-RTB non-neutralizing VHHs, RTB-G5 and RTB-B9 (Table 3). G5/B7 and G5/B9 are expected to bind to ricin with high affinities but have only moderate or no demonstrable toxin-neutralizing activity.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of VHH heterodimers

| Heterodimer | Constituents | EC50a | IC50b | Protectionc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | nm | |||

| D10/B7 | RTA-D10/RTB-B7 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 4 of 20 |

| F5/B7 | RTA-F5/RTB-B7 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 4 of 5 |

| E5/B7 | RTA-E5/RTB-B7 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 5 of 5 |

| G5/B7 | RTB-G5/RTB-B7 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0 of 5 |

| G5/B9 | RTB-G5/RTB-B9 | 0.10 | NAd | 0 of 5 |

a The values indicate the concentration of VHH required for 50% maximal ricin binding by ELISA.

b The values indicate the concentration of VHH required to neutralize 50% ricin in Vero cell assay.

c The values indicate the number of mice passively administered VHH (3 μg/mouse) that survived a 10 × LD50 ricin challenge.

d NA, not applicable.

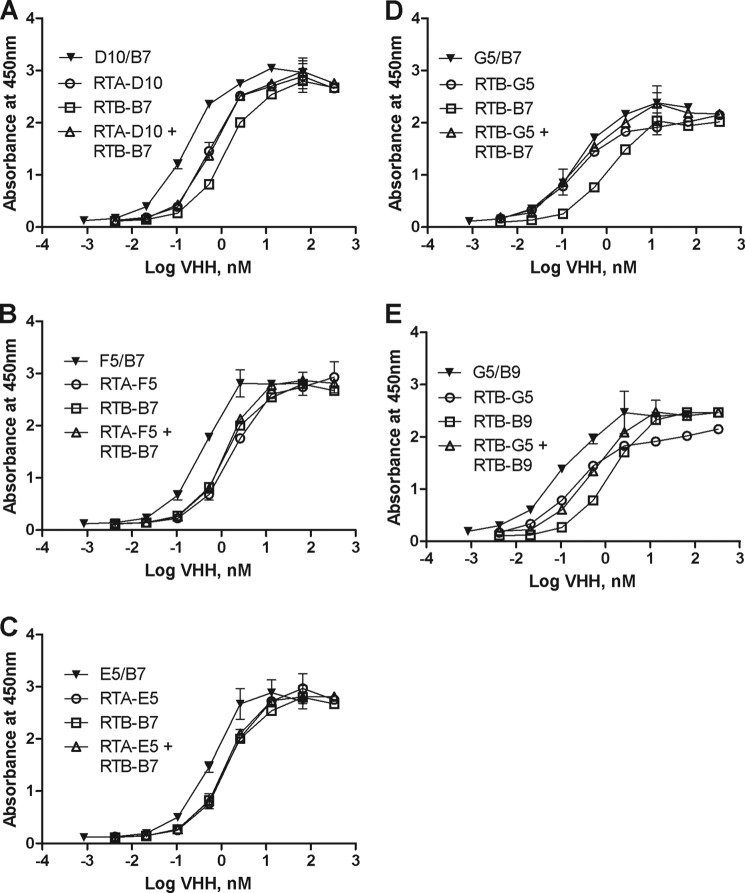

We first performed dilution ELISAs to determine the apparent affinities of the VHH heterodimers for ricin, as compared with the individual monomers or a 1:1 mixture of monomers. We found that each heterodimer had a lower EC50 than either of the component monomers or corresponding pool of monomers (Fig. 3, A–E). In the case of D10/B7, for example, there was a >8-fold decrease in EC50 compared with the RTB-B7 monomer alone (Table 3 and Fig. 3A). Thus, in this instance, physically linking the monomers resulted in approximately an order of magnitude increase in apparent affinity.

FIGURE 3.

Relative affinities of VHH heterodimers for ricin. To assess relative affinity of select VHH heterodimers (F5/B7, D10/B7, E5/B7, G5/B7, and G5/B9) and compare them to their monomeric constituents and equimolar mixtures of those monomers, the VHHs were applied at indicated concentrations (nm) in duplicate to microtiter plates coated with ricin, as described in the legend of Fig. 2. A–E show a single pair of monomeric VHHs (open symbols) and their corresponding heterodimers (solid symbols). Each panel represents one heterodimer and its corresponding monomers, as indicated in the legends embedded within the graphs. Shown are representative experiments with error bars indicating S.D. All experiments were replicated at least three times.

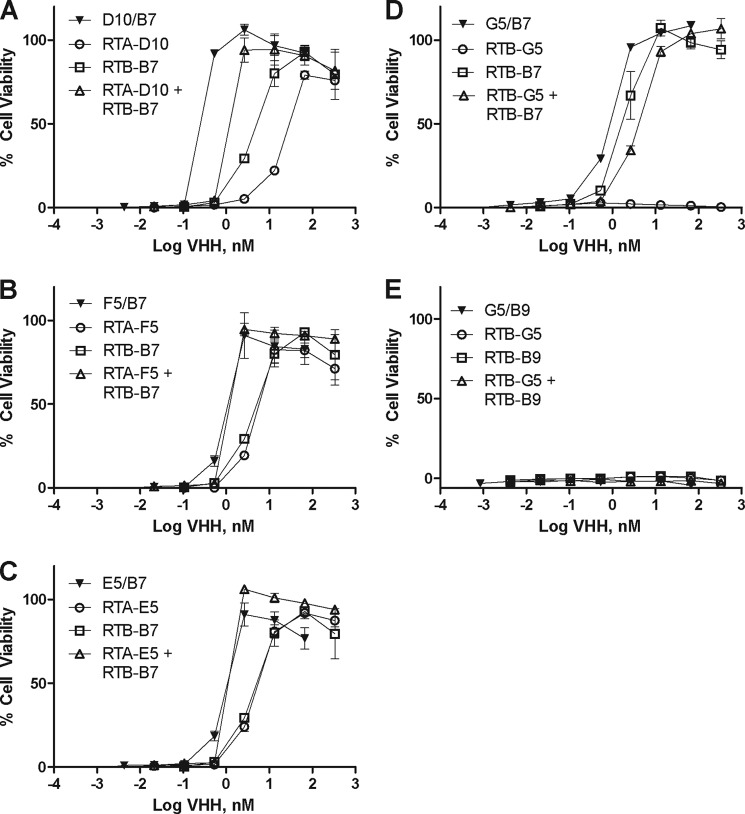

We next sought to determine whether the higher affinity heterodimers would be more potent toxin-neutralizers than their corresponding monomers. Each heterodimer was tested in the Vero cell cytotoxicity assay for ricin-neutralizing activity and compared with its corresponding monomers or a 1:1 pool of the monomers. Linking two non-neutralizing VHHs (G5/B9) did not result in an agent with any neutralizing activity, although G5/B7, composed of one neutralizing and one non-neutralizing VHH, was slightly more potent than its constituent neutralizing monomer (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

VHH heterodimers in vitro toxin-neutralizing activity. To assess toxin-neutralizing activities of select VHH heterodimers (F5/B7, D10/B7, E5/B7, G5/B7, and G5/B9) and compare them with their monomeric constituents and equimolar mixtures of those monomers, the VHHs were tested in a Vero cell cytotoxicity assay, as described in the legend of Fig. 2. VHHs (at indicated concentrations, nm) were mixed with ricin (10 ng/ml) and applied to Vero cells in triplicate. A–E show a single pair of monomeric VHHs (open symbols) and their corresponding heterodimers (solid symbols). Each panel represents one heterodimer and its corresponding monomers, as indicated in the legends embedded within the graphs. Shown are representative experiments with error bars indicating S.D. All experiments were replicated at least three times.

Despite their increased apparent affinities for ricin, F5/B7 and E5/B7, each consisting of two neutralizing VHH monomers, did not demonstrate enhanced toxin-neutralizing activity as compared with the pooled monomers (Fig. 4). On the other hand, D10/B7 did have markedly improved toxin-neutralizing activity, as compared with its respective individual monomers (∼30-fold) or with a 1:1 pool of monomers (>5-fold) (Table 3 and Fig. 4). D10/B7 was ∼7-fold more effective at neutralizing ricin in vitro than either F5/B7 or E5/B7 (Table 3).

In Vivo Passive Protection Afforded by VHH Heterodimer D10/B7 without and with a Secondary efAb

Because of its high in vitro neutralizing potency, we wished to test D10/B7 for its ability to passively protect mice from a 10 × LD50 dose of ricin toxin. D10/B7 was mixed with ricin at a heterodimer:toxin molar ratios of 1 (1.5 μg), 2 (3 μg), 4 (6 μg), and 8 (12 μg); incubated ex vivo for an hour; and then injected into mice via the intraperitoneal route. We also performed in vivo challenge studies in which we added a mouse monoclonal anti-E epitope tag IgG1 (effector antibody or efAb) to the heterodimer-toxin mixtures prior to injection into mice. We have previously shown that co-injection of the efAb with BoNT-specific VHH heterodimers improved toxin clearance (23) and the protective efficacy of VHH heteromultimers (21, 22). As controls for these studies, groups of mice received 10 μg (10:1 VHH:ricin ratio) of the individual VHH monomers (RTA-D10 or RTB-B7) or a mixture of 10 μg of each of RTA-D10 and RTB-B7. A final control group of animals received ricin but no antitoxin agents.

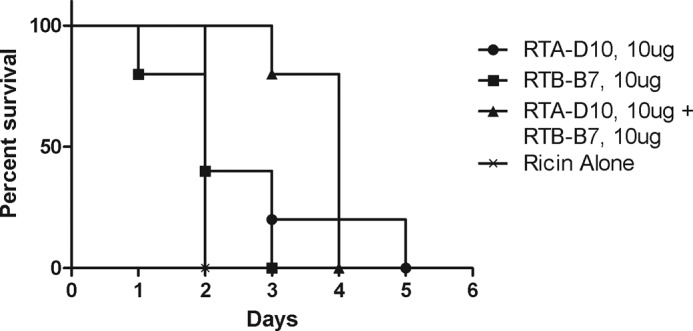

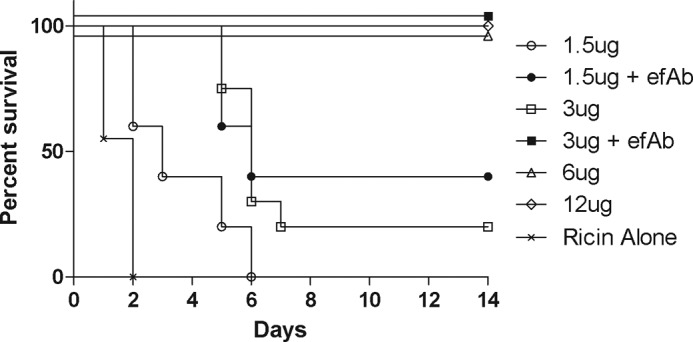

Mice that received monomeric VHHs alone had only a slightly greater time to death as compared with ricin-only treated animals. Mice that received a 1:1 mixture of monomers had a significantly longer time to death (p < 0.01), but eventually all mice in these groups succumbed as well (Fig. 5). However, the heterodimer D10/B7 demonstrated a dose-dependent capacity to protect mice against ricin challenge. Mice that received D10/B7 at 4- (6 μg) or 8-fold (12 μg) molar excess over ricin were completely protected from toxin challenge, whereas only 20% of the mice that received D10/B7 at 2-fold (3 μg) molar excess survived challenge. This dose, however, had a significantly longer time to death than ricin alone (p < 0.0001). A 1:1 ratio of D10/B7 to toxin provided no protection, although, again, there was a significant increase in mean time to death over ricin alone (p < 0.01). These data reveal that D10/B7 at 4-fold molar excess over ricin is sufficient to fully neutralize ricin in vivo. The addition of the efAb to the mixture markedly improved the performance of D10/B7 in vivo. In particular, whereas 2-fold (3 μg) molar excess D10/B7:ricin conferred only 20% protection in the challenge model, the same heterodimer:toxin ratio plus the efAb (2:1 efAb:heterodimer) conferred 100% protection (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 6). Note that, because the heterodimer binds twice to each toxin, a 2:1 ratio of agent:toxin is needed to saturate ricin binding. The addition of the efAb to a 1:1 D10/B7:ricin molar ratio resulted in 40% (two of five mice) protection, a significant improvement over D10/B7 alone at this dose (p < 0.05). This treatment also resulted in a prolonged time to death in the remaining mice (three of five mice), a significant improvement over animals that received ricin alone (p < 0.001).

FIGURE 5.

In vivo activity of monomeric VHHs upon ricin challenge. RTA-D10 and RTB-B7 VHH monomers (or an equimolar mixture of the monomers) were premixed at a 10:1 molar ratio (10 μg) with the equivalent of 10 × LD50 of ricin toxin (2 μg) and injected intraperitoneally into BALB/c mice. Survival was monitored over a 2-week period. Moribund mice with blood glucose levels less than 20 mg/dl were euthanized, as described under “Materials and Methods.” Each experimental group consisted of five mice (n = 5).

FIGURE 6.

In vivo protection conferred by VHH heterodimer D10/B7. D10/B7 (with or without efAb) was premixed at the indicated amounts with the equivalent of 10 × LD50 of ricin toxin (2 μg) and injected intraperitoneally into BALB/c mice. Survival was monitored over a 2-week period. Moribund mice with blood glucose levels less than 20 mg/dl were euthanized, as described under “Materials and Methods.” Each experimental group consisted of five mice, except the ricin control group (n = 20), the 3-μg dose group (n = 20), and the 3-μg dose + efAb group (n = 10).

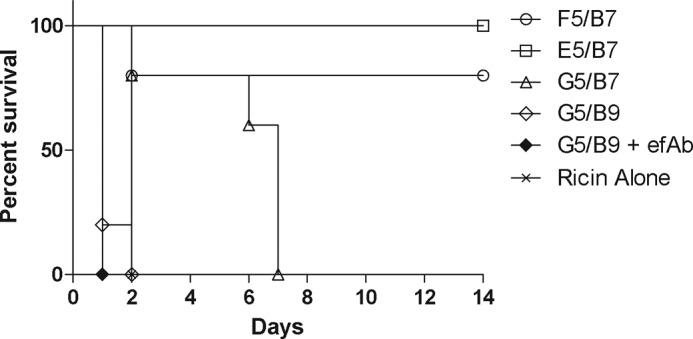

The observed improvement in protection afforded by efAb treatment is presumably the result of enhanced Fc receptor-mediated clearance of ricin-heterodimer complexes (23). However, we wished to investigate whether Fc receptor-mediated clearance is sufficient to promote ricin toxin-neutralization in vivo. We reasoned that if Fc receptor-mediated clearance is sufficient, then the addition of efAb to the non-neutralizing heterodimer G5/B9 would be expected to afford protection against ricin challenge, as compared with G5/B9 alone. Mice were passively administered G5/B9, without or with efAb, and then challenged with a 10 × LD50 dose of ricin toxin. We found that the efAb afforded no benefit to G5/B9, because mice treated or not with efAb succumbed to ricin intoxication with similar kinetics (Table 2 and Fig. 7). Therefore, Fc receptor-mediated clearance is itself not sufficient to neutralize ricin in vivo.

FIGURE 7.

In vivo protection by additional VHH heterodimers. Indicated heterodimers (with or without efAb) were premixed at a 2:1 molar ratio with the equivalent of 10 LD50 of ricin toxin (2 μg) and injected intraperitoneally into BALB/c mice. Survival was monitored over a 2-week period. Moribund mice with blood glucose levels less than 20 mg/dl were euthanized, as described under “Materials and Methods.” Each experimental group consisted of five mice (n = 5).

In Vivo Passive Protection Afforded by Other VHH Heterodimers

We tested the remaining VHH heterodimers, F5/B7, E5/B7 and RTB-G5/RTB-B7, for the ability to passively protect mice from a 10 × LD50 dose of ricin toxin. The heterodimers were mixed at a 2-fold molar excess (3 μg) with 10 × LD50 of ricin, a heterodimer:toxin ratio that in the case of D10/B7 afforded 20% protection, as shown in Fig. 5. Heterodimers F5/B7 and E5/B7 were able to protect 80% (p < 0.05) and 100% (p < 0.01) of mice, respectively. Heterodimer G5/B7 conferred no protection, although there was a significant increase in time to death over ricin alone (p < 0.05) (Table 2 and Fig. 7). Interestingly, even though D10/B7 is a more potent neutralizer in vitro, F5/B7 and E5/B7 were better able to protect mice from ricin intoxication at the 2:1 heterodimer:toxin ratio, in which both binding sites on ricin can be bound. Future experiments will be done to determine the most potent heterodimer and the lowest dose required for protection. Combined, these experiments show that VHH heterodimers display enhanced potency to protect animals from ricin exposure compared with VHH monomers, especially when both VHH components are toxin-neutralizing.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we engineered, using a unique platform technology, novel antitoxins against the category B toxin ricin. We initially identified 11 RTA-specific VHHs and 9 RTB-specific VHHs from a VHH library generated from two immunized alpacas. Among the 20 unique ricin-specific VHHs, we identified, six (five RTA-specific and one RTB-specific) had clear toxin-neutralizing activity in vitro. We next engineered a series of VHH heterodimers consisting of RTB-B7, the single neutralizing anti-RTB VHH, linked to one of three neutralizing anti-RTA VHHs. One heterodimer in particular, D10/B7, had a 6-fold increase in toxin-neutralizing activity in vitro as compared with an equimolar mixture of the component monomers. In vivo analysis revealed that D10/B7 was able to fully protect mice from a 10 × LD50 ricin challenge at a VHH:ricin ratio as low as 4:1. Co-administration of D10/B7 with an efAb improved the protective potential significantly, thereby demonstrating our capacity to engineer high affinity toxin-neutralizing antitoxins against ricin toxin. Two other neutralizing heterodimers, F5/B7 and E5/B7, appear to be slightly more potent than D10/B7 and will be tested further in the future. In light of our success in engineering protective VHH heterodimers against BoNT/A (21) and Shiga toxins Stx1 and Stx2 (22), these data reveal the power of this antitoxin technology to apply to a broad range of toxins. Therefore, we conclude that the technology is applicable to ricin and that this may have important implications as a general strategy for therapeutics against category A–C toxins.

Overall, five RTA-specific and one RTB-specific ricin-neutralizing VHHs were identified. Among the RTA-specific neutralizing VHHs, RTA-D10 appears to recognize an epitope that is distinct from the known neutralizing clusters (12), suggesting that it may recognize an as yet uncharacterized neutralizing epitope. However, four of the five were competitively inhibited from binding to ricin by the neutralizing murine mAb PB10, suggesting that these VHHs recognize epitopes that overlap or are identical with the epitope of PB10. We have previously defined the PB10 epitope at high resolution, showing that it recognizes a linear, solvent-exposed, immunodominant α-helix spanning residues 98–106 of RTA (31). This α-helix (called α-helix B) is a well known target of toxin-neutralizing antibodies (33) and is thought to be conserved among virtually all the ribosome-inactivating proteins (34). Interestingly, PB10 also competitively inhibited two non-neutralizing VHHs (RTA-A7 and RTA-E3) from binding to ricin. The failure of RTA-A7 and RTA-E3 to neutralize ricin could be because their epitopes, although overlapping the PB10 epitope, do not contact important neutralizing residues within the footprint of the contact region of PB10. Although the inability to neutralize ricin could be related to the VHH affinity for target, other results make this unlikely. For example, RTA-G12 and RTA-D10, both with affinities for ricin ∼600 pm, display vastly different neutralizing activities. RTA-G12 did not achieve 50% neutralization at the highest concentration tested (330 nm), whereas RTA-D10 had an IC50 of ∼25 nm. These results support the hypothesis that, beyond a certain affinity threshold, toxin-neutralizing activity is dictated by epitope specificity (1, 12).

From the nine RTB-specific VHHs identified, only one, RTB-B7, was able to neutralize the toxin in vitro. This is consistent with previous work from our lab with murine mAbs indicating that the vast majority of antibodies elicited to RTB are non-neutralizing and that neutralizing antibodies to RTB are extremely rare (1, 14). Moreover, as is the case for the RTA-specific VHHs, we found that affinity is not the sole factor in determining neutralizing activity. This was illustrated by the fact that RTB-B7 was one of the best neutralizers (IC50 of 4 nm), despite having a relatively low affinity for ricin (1.3 nm), and the fact that RTB-G5 failed to neutralize the toxin even though it has the highest relative affinity for ricin (EC50 of 230 pm) of all 20 VHHs identified in this study. At present, the epitope recognized by RTB-B7 has not been identified. Based on competitive binding assays, this epitope is clearly distinct from those recognized by the previously characterized RTB-specific neutralizing mAbs 24B11 and SylH3 (14, 16, 32). We speculate that RTB-B7 likely recognizes a conformation-dependent epitope based on its poor binding in Western blot analysis.4

We have recently reported that there are two types (I and II) of RTB-specific neutralizing mAbs (1, 15). Type I neutralizers are postulated to prevent RTB from binding to its receptors, thereby inhibiting toxin internalization. Type II neutralizers, however, recognize ricin when it is already bound to cell surfaces and are thought to interfere with toxin uptake and/or intracellular trafficking. Preliminary data suggest that RTB-B7 is a type II neutralizer.5 In the case of 24B11, we have evidence that the mAb shunts ricin away from the trans-Golgi network and promotes degradation through the lysosomal machinery.6

VHH monomers that neutralize ricin in vitro were unable to protect mice from ricin-induced death at the concentrations tested. In contrast, by covalently linking the monomers, the resulting VHH heterodimers were clearly effective in protecting mice from ricin intoxication. Furthermore, we showed that addition of efAb to the formulation significantly increased the protective efficacy. Because the VHH heterodimers each contain two copies of E-tag and because heterodimers can bind at two sites on the toxin, up to four efAbs can bind each toxin molecule. We have postulated that decorating the heterodimer-ricin complex with multiple efAbs leads to increased anti-toxin potency through the promotion of toxin clearance via low affinity FcγR (23). However, FcγR-mediated clearance is not itself sufficient to confer immunity to ricin, as evidenced by the fact that a high affinity heterodimer, G5/B9, consisting of two non-neutralizing VHHs, afforded no protection to mice against ricin challenge in the presence or absence of efAbs. This is in contrast to a previous study with BoNT in which co-administering efAb was able to improve the in vivo efficacy of non-neutralizing antitoxin VHH heterodimers (21). The differential effects of efAb could be due to the different cell tropisms exhibited by ricin and BoNT. BoNT toxicity is restricted to neurons, and uptake of non-neutralized toxin-antibody complexes into FcγR-bearing cells like macrophages should not cause pathology. In contrast, ricin intoxicates all cell types and is known to preferentially target macrophages, including Kuppfer cells in the liver (35). Therefore, accelerated FcγR-mediated clearance of ricin in the absence of neutralization may not improve the clinical results and could even enhance the toxicity.

Our future studies will be aimed at testing D10/B7 as well as two other neutralizing heterodimers, F5/B7 and E5/B7, as possible therapeutics for ricin intoxication. We have shown using murine and murine-human chimeric mAbs that antibody treatment within 4–6 h of toxin exposure is sufficient to rescue mice from the effects of ricin administered by intraperitoneal injection (13) or aerosol.7 Based on the results presented in this study, we propose that VHH heterodimers and the inclusion of efAbs will extend the therapeutic window beyond these time points. Finally, the VHHs identified in this study may also prove useful in ricin toxin detection. Indeed, Anderson et al. (36) developed a ricin-specific immunoassay using camelid VHHs that can differentiate between ricin and the closely related protein RCA I. With this assay, they were able to achieve sensitive ricin detection (<100 pg/ml) using an anti-RTB VHH, B4, with an affinity for ricin of 2 nm. In our study, RTB-G5, an anti-RTB VHH, had an EC50 of 231 pm. Therefore, the use of RTB-G5 alone or in combination with other VHHs may enable the development of a more sensitive detection assay.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daniela Bedenice (Tufts University) for alpaca veterinary assistance and Dr. Jean Mukherjee (Tufts University) and her staff for performing the alpaca immunizations, bleedings, and PBL preparation. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Jane Kasten-Jolly of the Wadsworth Center's Immunology Core for performing the Biacore analysis. We thank Drs. Joanne O'Hara and Anastasiya Yermakova for providing us with murine monoclonal antibodies used in the competition assays and for constructive feedback and technical advice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI097688 (to N. J. M.) and U54-AI057159 (to C. B. S.).

D. J. Vance, J. M. Tremblay, N. J. Mantis, and C. B. Shoemaker, unpublished data.

C. Herrera, D. J. Vance, and N. J. Mantis, unpublished observations.

A. Yermakova, T. I. Klokk, K. Sandvig, and N. Mantis, manuscript submitted.

E. Sully, K. Whaley, M. Pauly, L. Zeitlin, C. Roy, and N. Mantis, unpublished results.

- Stx

- Shiga toxin

- BoNT

- botulinum neurotoxins

- RTA

- ricin A subunit

- RTB

- ricin B subunit

- VHH

- heavy chain-only antibody VH domain

- efAb

- effector antibody.

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Hara J. M., Yermakova A., Mantis N. J. (2012) Immunity to ricin. Fundamental insights into toxin-antibody interactions. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 357, 209–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sandvig K., Torgersen M. L., Engedal N., Skotland T., Iversen T. G. (2010) Protein toxins from plants and bacteria. Probes for intracellular transport and tools in medicine. FEBS Lett. 584, 2626–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rutenber E., Ready M., Robertus J. D. (1987) Structure and evolution of ricin B chain. Nature 326, 624–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sandvig K., Olsnes S., Pihl A. (1976) Kinetics of binding of the toxic lectins abrin and ricin to surface receptors of human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 3977–3984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spooner R. A., Lord J. M. (2012) How ricin and Shiga toxin reach the cytosol of target cells. Retrotranslocation from the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 357, 19–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jandhyala D. M., Thorpe C. M., Magun B. (2012) Ricin and Shiga toxins. Effects on host cell signal transduction. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 357, 41–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Franz D. R. (2004) Defense against Toxin Weapons, Virtual Naval Hospital Project, Washington, D.C [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rotz L. D., Khan A. S., Lillibridge S. R., Ostroff S. M., Hughes J. M. (2002) Public health assessment of potential biological terrorism agents. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 225–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olsnes S. (1978) Ricin and ricinus agglutinin, toxic lectins from castor bean. Methods Enzymol. 50, 330–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reisler R. B., Smith L. A. (2012) The need for continued development of ricin countermeasures. Adv. Prev. Med. 2012, 149737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolfe D. N., Florence W., Bryant P. (2013) Current biodefense vaccine programs and challenges. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 9, 1591–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Hara J. M., Neal L. M., McCarthy E. A., Kasten-Jolly J. A., Brey R. N., 3rd, Mantis N. J. (2010) Folding domains within the ricin toxin A subunit as targets of protective antibodies. Vaccine 28, 7035–7046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Hara J. M., Whaley K., Pauly M., Zeitlin L., Mantis N. J. (2012) Plant-based expression of a partially humanized neutralizing monoclonal IgG directed against an immunodominant epitope on the ricin toxin A subunit. Vaccine 30, 1239–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yermakova A., Mantis N. J. (2011) Protective immunity to ricin toxin conferred by antibodies against the toxin's binding subunit (RTB). Vaccine 29, 7925–7935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yermakova A., Mantis N. J. (2013) Neutralizing activity and protective immunity to ricin toxin conferred by B subunit (RTB)-specific Fab fragments. Toxicon 72, 29–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yermakova A., Vance D. J., Mantis N. J. (2012) Sub-domains of ricin's B subunit as targets of toxin neutralizing and non-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. PLoS One 7, e44317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dumoulin M., Conrath K., Van Meirhaeghe A., Meersman F., Heremans K., Frenken L. G., Muyldermans S., Wyns L., Matagne A. (2002) Single-domain antibody fragments with high conformational stability. Protein Sci. 11, 500–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gibbs W. W. (2005) Nanobodies. Sci. Am. 293, 78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lauwereys M., Arbabi Ghahroudi M., Desmyter A., Kinne J., Hölzer W., De Genst E., Wyns L., Muyldermans S. (1998) Potent enzyme inhibitors derived from dromedary heavy-chain antibodies. EMBO J. 17, 3512–3520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Linden R. H., Frenken L. G., de Geus B., Harmsen M. M., Ruuls R. C., Stok W., de Ron L., Wilson S., Davis P., Verrips C. T. (1999) Comparison of physical chemical properties of llama VHH antibody fragments and mouse monoclonal antibodies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1431, 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mukherjee J., Tremblay J. M., Leysath C. E., Ofori K., Baldwin K., Feng X., Bedenice D., Webb R. P., Wright P. M., Smith L. A., Tzipori S., Shoemaker C. B. (2012) A novel strategy for development of recombinant antitoxin therapeutics tested in a mouse botulism model. PLoS One 7, e29941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tremblay J. M., Mukherjee J., Leysath C. E., Debatis M., Ofori K., Baldwin K., Boucher C., Peters R., Beamer G., Sheoran A., Bedenice D., Tzipori S., Shoemaker C. B. (2013) A single VHH-based toxin neutralizing agent and an effector antibody protects mice against challenge with Shiga toxins 1 and 2. Infect. Immun. 81, 4592–4603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sepulveda J., Mukherjee J., Tzipori S., Simpson L. L., Shoemaker C. B. (2010) Efficient serum clearance of botulinum neurotoxin achieved using a pool of small antitoxin binding agents. Infect. Immun. 78, 756–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Hara J. M., Brey R. N., 3rd, Mantis N. J. (2013) Comparative efficacy of two leading candidate ricin toxin a subunit vaccines in mice. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20, 789–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maass D. R., Harrison G. B., Grant W. N., Shoemaker C. B. (2007) Three surface antigens dominate the mucosal antibody response to gastrointestinal L3-stage strongylid nematodes in field immune sheep. Int. J. Parasitol. 37, 953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tremblay J. M., Kuo C. L., Abeijon C., Sepulveda J., Oyler G., Hu X., Jin M. M., Shoemaker C. B. (2010) Camelid single domain antibodies (VHHs) as neuronal cell intrabody binding agents and inhibitors of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) proteases. Toxicon 56, 990–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wahome P. G., Mantis N. J. (2013) Curr. Protoc. Toxicol., Chapter 2, Unit 2.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neal L. M., O'Hara J., Brey R. N., 3rd, Mantis N. J. (2010) A monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibody directed against an immunodominant linear epitope on the ricin A chain confers systemic and mucosal immunity to ricin. Infect. Immun. 78, 552–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pincus S. H., Eng L., Cooke C. L., Maddaloni M. (2002) Identification of hypoglycemia in mice as a surrogate marker of ricin toxicosis. Comp. Med. 52, 530–533 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O'Hara J. M., Mantis N. J. (2013) Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against ricin's enzymatic subunit interfere with protein disulfide isomerase-mediated reduction of ricin holotoxin in vitro. J. Immunol. Methods 395, 71–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vance D. J., Mantis N. J. (2012) Resolution of two overlapping neutralizing B cell epitopes within a solvent exposed, immunodominant α-helix in ricin toxin's enzymatic subunit. Toxicon 60, 874–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGuinness C. R., Mantis N. J. (2006) Characterization of a novel high-affinity monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibody against the ricin B subunit. Infect. Immun. 74, 3463–3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lemley P. V., Wright D. C. (1992) Mice are actively immunized after passive monoclonal antibody prophylaxis and ricin toxin challenge. Immunology 76, 511–513 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lebeda F. J., Olson M. A. (1999) Prediction of a conserved, neutralizing epitope in ribosome-inactivating proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 24, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simmons B. M., Stahl P. D., Russell J. H. (1986) Mannose receptor-mediated uptake of ricin toxin and ricin A chain by macrophages. Multiple intracellular pathways for a chain translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 7912–7920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson G. P., Bernstein R. D., Swain M. D., Zabetakis D., Goldman E. R. (2010) Binding kinetics of antiricin single domain antibodies and improved detection using a B chain specific binder. Anal Chem. 82, 7202–7207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]