Background: Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO) is hypothesized to play a pivotal role in regulating tryptophan metabolism in health and disease.

Results: Mice that were generated lacking KMO have alterations in the levels of several tryptophan metabolites.

Conclusion: KMO is a critical regulator of tryptophan metabolism.

Significance: KMO knock-out mice will be a useful research tool to dissect the biological and pathophysiological roles of tryptophan metabolism.

Keywords: Metabolism, Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection, Schizophrenia, Tryptophan, Kynurenic Acid, Kynurenine, Kynurenine 3-Monooxygenase

Abstract

Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO), a pivotal enzyme in the kynurenine pathway (KP) of tryptophan degradation, has been suggested to play a major role in physiological and pathological events involving bioactive KP metabolites. To explore this role in greater detail, we generated mice with a targeted genetic disruption of Kmo and present here the first biochemical and neurochemical characterization of these mutant animals. Kmo−/− mice lacked KMO activity but showed no obvious abnormalities in the activity of four additional KP enzymes tested. As expected, Kmo−/− mice showed substantial reductions in the levels of its enzymatic product, 3-hydroxykynurenine, in liver, brain, and plasma. Compared with wild-type animals, the levels of the downstream metabolite quinolinic acid were also greatly decreased in liver and plasma of the mutant mice but surprisingly were only slightly reduced (by ∼20%) in the brain. The levels of three other KP metabolites: kynurenine, kynurenic acid, and anthranilic acid, were substantially, but differentially, elevated in the liver, brain, and plasma of Kmo−/− mice, whereas the liver and brain content of the major end product of the enzymatic cascade, NAD+, did not differ between Kmo−/− and wild-type animals. When assessed by in vivo microdialysis, extracellular kynurenic acid levels were found to be significantly elevated in the brains of Kmo−/− mice. Taken together, these results provide further evidence that KMO plays a key regulatory role in the KP and indicate that Kmo−/− mice will be useful for studying tissue-specific functions of individual KP metabolites in health and disease.

Introduction

Under physiological conditions, the kynurenine pathway (KP)3 is responsible for >95% of tryptophan degradation in mammals, ultimately leading to the formation of NAD+ (1, 2). Located in a pivotal position in the KP, kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO) is a FAD-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the 3-hydroxylation of l-kynurenine (“kynurenine”) in the presence of NADPH and molecular oxygen. KMO localizes to the outer membrane of mitochondria and is highly expressed in peripheral tissues, including liver and kidney, and in phagocytes such as macrophages and monocytes (3, 4). In the central nervous system, KMO is expressed predominantly in microglial cells (5, 6). Notably, cytokines stimulate KMO activity both in the periphery and in the brain when the immune system is activated (7, 8).

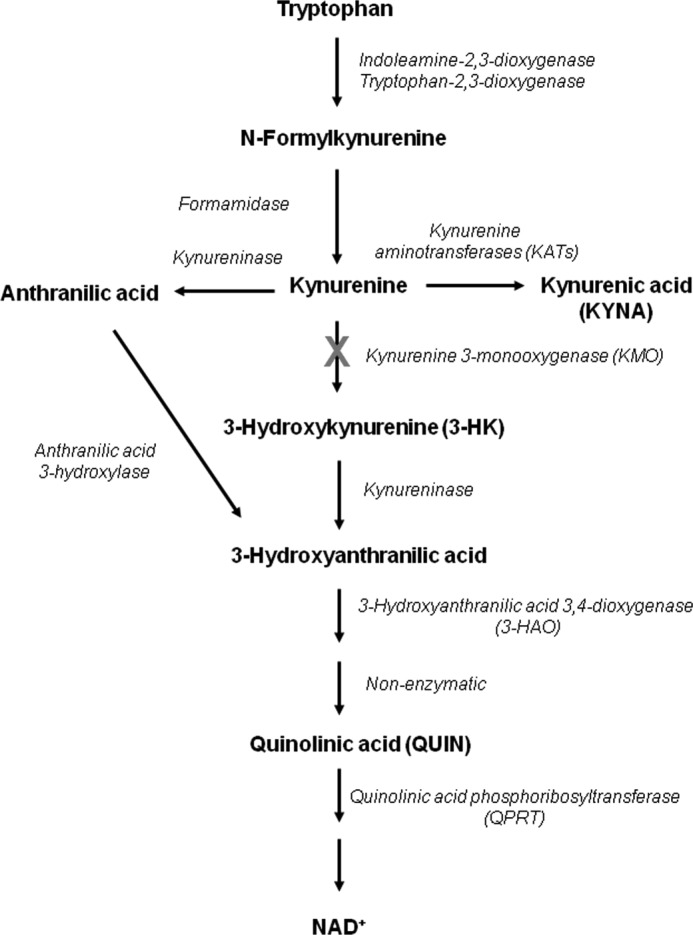

Because of its central location in the metabolic cascade, KMO controls the synthesis of several bioactive KP metabolites, including 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK), quinolinic acid (QUIN), and kynurenic acid (KYNA), as well as anthranilic acid (Fig. 1). Kynurenine, the substrate of KMO, itself promotes tumor formation (9), regulates vascular tone, and generates regulatory T cells by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and/or adenylate and guanylate cyclase pathways (10–13). 3-HK, the primary enzymatic product of KMO, is a potent free radical generator that can trigger neuronal apoptosis (14–16). Similar features have been described for the next KP metabolite in the major branch of the pathway, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (17). Its downstream product, QUIN, can also generate reactive free radicals (18), but is best known for its ability to produce excitotoxic lesions in the central nervous system by activating the NMDA subtype of glutamate receptors (1, 19, 20) and as a bioprecursor of the ubiquitous coenzyme NAD+.

FIGURE 1.

Major metabolites of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan degradation. KMO, located in a pivotal position of the pathway, is responsible for the conversion of kynurenine to neurotoxic metabolites (such as 3-hydroxykynurenine and quinolinic acid) in the main branch of the enzymatic cascade. However, kynurenine can also be enzymatically converted to anthranilic acid or to the neuroprotective metabolite kynurenic acid. The kynurenine pathway normally accounts for >95% of tryptophan metabolism in mammals.

Selective pharmacological inhibition of KMO leads to the increased formation of kynurenic acid (KYNA) in a dead end side arm of the KP (Fig. 1). At physiological concentrations, this metabolite has several biological targets, acting as an antagonist of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and the glycine co-agonist site of the NMDA receptor (21, 22) and as an agonist of the G protein-coupled receptor GPR35 (23) and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (24). Together with its capacity to scavenge free radicals (25), these actions account for the neuromodulatory and neuroprotective properties of KYNA (20, 26, 27) and for its ability to affect cytokine expression and function (24, 28).

KMO inhibition is increasingly recognized as a useful experimental approach to unravel the characteristics of KP metabolism in brain and periphery. This, as well as the realization that KP manipulation by specific KMO inhibitors may have therapeutic utility in human maladies ranging from neurodegenerative disorders and major depression to immunological diseases and cancer (1, 20, 29–32), has not only prompted the development of several potent enzyme inhibitors (33–36) but recently also led to the first reported crystal structure of KMO (37).

To expand the experimental armamentarium for the study of KP biology in mammals, we produced mice with a targeted deletion of the KMO gene. We describe here the generation of Kmo−/− mice and present an analysis of KP metabolites and enzymes in brain, liver, and plasma of these animals. Our study revealed novel characteristics of mammalian KP metabolism, indicating that the newly generated mutant mice will serve as a useful research tool for dissecting the proposed roles of bioactive metabolites in physiology and pathology.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Kmo−/− Mice

The Kmo conditional targeting construct was generated using the 4517D vector, kindly provided by Dr. Richard Palmiter (University of Washington). This vector contains a Pgk:neomycin resistance (NeoR) cassette for positive selection, which is flanked by FRT sites to allow FLP recombinase-mediated excision following selection of homologous recombinants (38). The vector also contains a 5′ diphtheria toxin cassette and a 3′ HSV:thymidine kinase cassette, both for negative selection. The targeting construct was designed such that exon 5 of Kmo is flanked by loxP sites and is thus targeted for deletion. A C57Bl/6J genomic DNA fragment containing the entire Kmo genomic region was obtained in the pBACe3.6 Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) vector (BACPAC Resource Center, Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, CA). The right arm of the targeting vector was derived from a 5.7-kb ApaI fragment from the Kmo BAC that was shotgun cloned into the pKS-Bluescript plasmid (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA). A 1.9-kb KpnI-PacI fragment from this construct was further subcloned into the PmeI site of 4517D downstream of the NeoR cassette, generating the 4517D (1.9-kb KpnI-PacI) construct. The left arm of the construct was derived from a 5.2-kb KpnI fragment from the above BAC, which was shotgun cloned into pKS-Bluescript. A double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding both a loxP site and a HpaI site was cloned into the StuI site of this 5.2-kb KpnI fragment, thereby generating a HpaI site and destroying the StuI site. The 5.2-kb KpnI loxP fragment was cloned into the 4517D (1.9-kb KpnI-PacI) construct upstream of the NeoR cassette using Acc651 (a neoschizomer of KpnI), yielding the final targeting construct.

The Kmo targeting construct was linearized at the 5′ end with NotI and electroporated into a mouse ES cell line, derived from the C57Bl/6J strain of mice. NeoR-positive ES cell clones were selected, and 96 were screened by PCR for correct integration on the 3′ end of the clone. Of the clones, 28 of 96 were positive, and they were screened by Southern blotting using a probe external to the targeting construct to confirm correct integration of both ends of the construct, yielding seven positive clones. Positive clones were injected into CBA inbred strain-derived murine blastocysts to produce chimeric founders, which were identified by coat color and mated to C57Bl/6J wild-type breeders to confirm germ line transmission, which was ascertained by coat color and PCR genotyping of the NeoR cassette. This founder line was then bred to mice carrying FLP-recombinase (39) to excise the NeoR cassette. This transgenic line of mice was designated as Kmoflox(ex)5-NeoRΔ and bred to β-actin Cre-C57Bl/6J (40) mice to generate KMO knock-out mice (Kmo−/−), which were subsequently backcrossed to the FVB/N background for at least six generations, using the Speed Congenics Service (The Jackson Laboratory) to identify the optimal breeders.

Detection of KMO by Immunoblotting

Mice were perfused with 0.9% NaCl, and the right hemi-brain was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (prechilled to 4 °C) for 48 h and then reduced to 2% paraformaldehyde for storage at 4 °C. One hemi-brain, as well as a portion of the liver, was snap frozen after saline perfusion and stored at −80 °C until use. The tissues were then defrosted on ice and homogenized with 400 μl of ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mm NaCl, 1% Igepal CA-630, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol and proteinase inhibitor mixture tablet) in a prechilled 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube with a matching pestle until no visible tissue chunks remained. Two hundred ml of ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer were then added to the homogenate. After rehomogenization (30 s), the samples were kept on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged (>11,000 × g) for 90 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected in aliquots and stored at −80 °C for future use. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Samples containing 25 and 100 μg of total liver and brain protein, respectively, were mixed with 8% SDS loading buffer and kept at room temperature for 5–10 min. Samples were then loaded on a 12% Tris-HEPES protein polyacrylamide gel and run at 100 V for ∼55 min. After separation, the protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was blocked with 5% nonfat milk in 0.1% TBST (1× TBS plus 0.1% Tween 20). The membrane was probed with KMO antibody (CHDI-90000271; 21 Century Biochemicals; 1:1,000 for brain, 1:5,000 for liver), and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5,000). Protein was detected by chemiluminescence (ECL kit; GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Chemicals

NADPH (tetrasodium salt) was purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA). l-Tryptophan, 3-dl-HK, QUIN, KYNA, anthranilic acid, [2H6]l-kynurenine, pentafluoropropionic anhydride, and 2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoro-1-propanol were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Ro 61-8048 was a generous gift from Dr. W. Fröstl (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland). l-Kynurenine sulfate (“kynurenine”; purity, 99.4%) was obtained from Sai Advantium (Hyderabad, India). 4-Chloro-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid was kindly provided by Drs. W. P. Todd and B. K. Carpenter (Department of Chemistry, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY). [2H3]QUIN was purchased from Synfine Research (Richmond Hill, Canada), and [2H5]l-tryptophan was obtained from CDN Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, Canada). [1-14C]3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid (6 mCi/mmol) was obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences, and [3H]QUIN (27 Ci/mmol) was custom-synthesized by Amersham Biosciences. All other fine biochemicals and chemicals were purchased from various commercial suppliers and were of the highest available purity.

Enzyme Activities and Metabolite Analyses

Animals were killed by cervical dislocation. Trunk blood was collected in EDTA-containing tubes, and red blood cells were rapidly removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g; microcentrifuge). The supernatant plasma was collected and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Brain (cerebral cortex) and liver tissues were rapidly dissected out, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C. Enzyme activities and metabolites were analyzed separately (n = 5–9/group). For enzyme assays, tissues were thawed out, homogenized 1:5 (w/v) in ultrapure water, and processed as detailed below.

Kynurenine 3-Monooxygenase (KMO; EC 1.14.13.9)

The original tissue homogenate was diluted 1:5 (brain) or 1:6,000 (liver) (v/v) in 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.1) containing 10 mm KCl and 1 mm EDTA. Eighty μl of the preparation were incubated for 40 min at 37 °C in a solution containing 1 mm NADPH, 3 mm glucose-6-phosphate, 1 unit/ml glucose-6 phosphate dehydrogenase, 100 μm kynurenine, 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.1), 10 mm KCl, and 1 mm EDTA, in a total volume of 200 μl. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μl of 6% perchloric acid. Blanks were obtained by adding the KMO inhibitor Ro 61-8048 (100 μm) to the incubation solution. After centrifugation (16,000 × g; 15 min), 20 μl of the supernatant were applied to a 3-μm HPLC column (HR-80; 80 mm × 4.6 mm; ESA, Chelmsford, MA), using a mobile phase consisting of 1.5% acetonitrile, 0.9% triethylamine, 0.59% phosphoric acid, 0.27 mm EDTA, and 8.9 mm sodium heptane sulfonic acid, and a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. In the eluate, the reaction product, 3-HK, was detected electrochemically using a HTEC 500 detector (Eicom Corp., San Diego, CA; oxidation potential: +0.5 V) (41). The retention time of 3-HK was ∼11 min.

Kynureninase (EC 3.7.1.3) Using 3-HK as the Substrate

The original tissue homogenate was diluted 1:40 (brain) or 1:4,000 (liver) (v/v) in 5 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.4) containing 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol and 50 μm pyridoxal-5′-phosphate. 100 μl of the preparation were then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a solution containing 90 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.4) and 4 μm dl-3-HK, in a total volume of 200 μl. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μl of 6% perchloric acid. To obtain blanks, tissue homogenate was added at the end of the incubation, i.e., immediately prior to the denaturing acid. After removing the precipitate by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 15 min), 25 μl of the resulting supernatant were applied to a 5-μm C18 reverse phase HPLC column (Adsorbosil; 150 × 4.6 mm; Grace, Deerfield, IL) using a mobile phase containing 100 mm sodium acetate (pH 5.8) and 1% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. In the eluate, the reaction product, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, was detected fluorimetrically (excitation wavelength, 322 nm; emission wavelength, 414 nm; S200 fluorescence detector; PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The retention time of 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid was ∼4 min.

Kynureninase (EC 3.7.1.3) Using Kynurenine as the Substrate

Essentially identical incubation conditions were used to determine enzyme activity with kynurenine as the substrate. In this case, the original tissue homogenate was either used undiluted (brain) or diluted 1:400 (liver) (v/v) in the same 5 mm Tris-HCl buffer described above, and 80 μl of the preparation were incubated for 2 h in the presence of 6 μm kynurenine. Following termination of the reaction, 25 μl of the supernatant were subjected to HPLC (as above), and the enzymatic product, anthranilic acid, was detected fluorimetrically in the eluate (excitation wavelength, 340 nm; emission wavelength, 410 nm; S200 fluorescence detector; PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The retention time of anthranilic acid was ∼7 min.

3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid 3,4-Dioxygenase (3-HAO; EC 1.13.11.6)

The original tissue homogenate was diluted 1:5 (brain) or 1:2,000 (liver) (v/v) in 60 mm MES buffer (pH 6.0), and 100 μl of the tissue preparation were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in a solution containing 0.01% ascorbic acid, 153 μm (FeNH4)2(SO4)3, and 3 μm (3.4 nCi) [1-14C]3-hydroxyanthranilic acid in a total volume of 200 μl. The incubation was terminated by the addition of 50 μl of 6% perchloric acid, and the product ([14C]QUIN) was recovered by ion exchange chromatography (Dowex 50, H+-form) and quantified by liquid scintillation spectrometry (42). Blanks were obtained by including the 3-HAO inhibitor 4-chloro-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (100 μm) in the incubation solution.

Quinolinic Acid Phosphoribosyltransferase (QPRT; EC 2.4.2.19)

The original tissue homogenate was either used undiluted (brain) or diluted 1:120 (liver) (v/v). Forty μl of the preparation were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a solution containing 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm phosphoribosylpyrophosphate, and 20 nm [3H]QUIN (30 nCi) in a total volume of 0.5 ml. Blanks were obtained by including the QPRT inhibitor phthalic acid (500 μm) in the incubation solution. The reaction was terminated by placing the tubes on ice, and particulate matter was separated by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 10 min). Newly formed [3H]nicotinic acid mononucleotide was recovered from a Dowex AG 1 × 8 anion exchange column and quantified by liquid scintillation spectrometry (43).

Kynurenine Aminotransferase II (KAT II; EC 2.6.1.7)

The original tissue homogenate was diluted 1:2 (brain) or 1:100 (liver) (v/v) in 5 mm Tris acetate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol and 50 μm pyridoxal-5′-phosphate. Eighty μl of the preparation were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a solution containing 150 mm Tris acetate buffer (pH 7.4), 100 μm kynurenine, 1 mm pyruvate, and 80 μm pyridoxal-5′-phosphate in a total volume of 200 μl. Blanks were obtained by adding aminooxyacetic acid (1 mm) to the incubation solution. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 20 μl of 50% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and 1 ml of 0.1 n HCl, and the precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 10 min). After diluting the resulting supernatant with ultrapure water (brain, 1:10; liver, 1:100), 20 μl of the supernatant were applied to a 3-μm C18 reverse phase column (HR-80; 80 × 4.6 mm; ESA), and KYNA was isocratically eluted using a mobile phase containing 250 mm zinc acetate, 50 mm sodium acetate, and 3% acetonitrile (pH 6.2) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. In the eluate, KYNA was detected fluorimetrically (excitation wavelength, 344 nm; emission wavelength, 398 nm; S200 fluorescence detector; PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The retention time of KYNA under these conditions was ∼7 min.

For the determination of KP metabolites, samples were thawed and processed as follows.

KYNA

Plasma was diluted (1:10, v/v), and tissues were homogenized (brain, 1:5; liver, 1:50; w/v) in ultrapure water. Twenty-five μl of 6% perchloric acid were added to 100 μl of the samples. After thorough mixing, the precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 15 min). Twenty μl of the resulting supernatant were subjected to HPLC analysis, and KYNA was assessed as described above (see “Kynurenine Aminotransferase II”).

3-HK

Plasma was diluted (1:2, v/v), and tissues (brain or liver) were homogenized (1:5, w/v) in ultrapure water. Twenty-five μl of 6% perchloric acid were added to 100 μl of the samples. After thorough mixing, the precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 15 min). Twenty μl of the resulting supernatant were subjected to HPLC analysis, and 3-HK was assessed as described above (see “Kynurenine 3-Monooxygenase”).

Anthranilic Acid

Anthranilic acid was measured according to the method of Cannazza et al. (44). Plasma was diluted (1:10, v/v), and tissues were homogenized (brain, 1:20; liver, 1:40; w/v) in ultrapure water. Twenty-five μl of 6% perchloric acid were added to 100 μl of the samples. After thorough mixing, the precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 15 min). Thirty μl of the resulting supernatant were subjected to HPLC analysis. Anthranilic acid was isocratically eluted from a 5-μm C18 reverse phase column (YMC-Pack Pro C18; 250 × 4.6 mm; YMC) using a mobile phase containing 20 mm sodium acetate and 10% methanol (pH adjusted to 5.5 with glacial acetic acid) and was detected fluorimetrically (excitation wavelength, 316 nm; emission wavelength, 420 nm; S200 fluorescence detector; PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The retention time of anthranilic acid was ∼18 min.

Tryptophan, Kynurenine, and QUIN

Tryptophan, kynurenine, and QUIN levels in brain and liver, and QUIN in plasma, were quantified by GC/MS. To this end, plasma was diluted (1:10, v/v), and tissues were homogenized (1:20, w/v) in an aqueous solution containing 0.1% ascorbic acid. Fifty μl of a solution containing internal standards (500 nm [2H5]l-tryptophan, 10 μm [2H6]l-kynurenine, and 50 nm [2H3]QUIN) were added to 50 μl of the tissue preparation, and proteins were precipitated with 50 μl of acetone. After centrifugation (13,700 × g, 5 min), 50 μl of a methanol:chloroform mixture (20:50, v/v) were added to the supernatant, and the samples were centrifuged (13,700 × g, 10 min). The upper layer was added to a glass tube and evaporated to dryness (90 min). The samples were then reacted with 120 μl of 2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoro-1-propanol and 130 μl of pentafluoropropionic anhydride at 75 °C for 30 min, dried down again, and taken up in 50 μl of ethyl acetate. One μl was then injected into the GC. GC/MS analysis was carried out with a 7890A GC coupled to a 7000 MS/MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), using electron capture negative chemical ionization (45).

For kynurenine measurement in plasma, 50 μl of 6% perchloric acid were thoroughly mixed with 100 μl of plasma, and the precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 15 min). Twenty μl of the supernatant were applied to a 3-μm C18 reverse phase column (HR-80; 80 × 4.6 mm; ESA), and kynurenine was isocratically eluted using a mobile phase containing 250 mm zinc acetate, 50 mm sodium acetate, and 3% acetonitrile (pH 6.2) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Kynurenine was detected fluorimetrically (excitation wavelength, 365 nm; emission wavelength, 480 nm; S200 fluorescence detector, PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The retention time of kynurenine under these conditions was ∼6 min.

NAD+

The levels of NAD+ were quantified using the EnzyChromTM NAD+/NADH assay kit according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 20 mg of tissue (brain or liver) were washed with cold PBS and homogenized in 100 μl of NAD+ extraction buffer. The samples were then heated at 60 °C for 5 min, and 20 μl of the assay buffer and 100 μl of NADH extraction buffer were added, thoroughly mixed, and centrifuged (16,000 × g, 5 min). The resulting supernatant was diluted 1:5 with ultrapure water. Forty μl of the diluted supernatant were then mixed with 90 μl of the working reagent mixture and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The absorbance was read both at time 0 and 15 min on a plate reader, with the reference and measuring filters set at 450 and 570 nm, respectively.

Microdialysis

The mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (360 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) and mounted in a David Kopf stereotaxic frame (Tujunga, CA). A guide cannula (outer diameter, 0.65 mm) was positioned over the striatum (anteroposterior, 0.5 mm anterior to bregma; lateral, 1.2 mm from midline; and ventral, 1.1 mm below the skull) and secured to the skull with an anchor screw and acrylic dental cement. A concentric microdialysis probe (membrane length, 1 mm; SciPro, Sanborn, NY) was then inserted through the guide cannula. The probe was connected to a microinfusion pump set to a speed of 1 μl/min and perfused with Ringer solution containing 144 mm NaCl, 4.8 mm KCl, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.7 mm CaCl2 (pH 6.7). Samples were collected every 60 min for 8 h. The concentration of KYNA was determined in the microdialysate as described (46), and data are reported without correction for recovery from the microdialysis probe.

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as the means ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. Asterisks indicate significance versus wild-type controls (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

RESULTS

Generation and Validation of Kmo−/− Mice

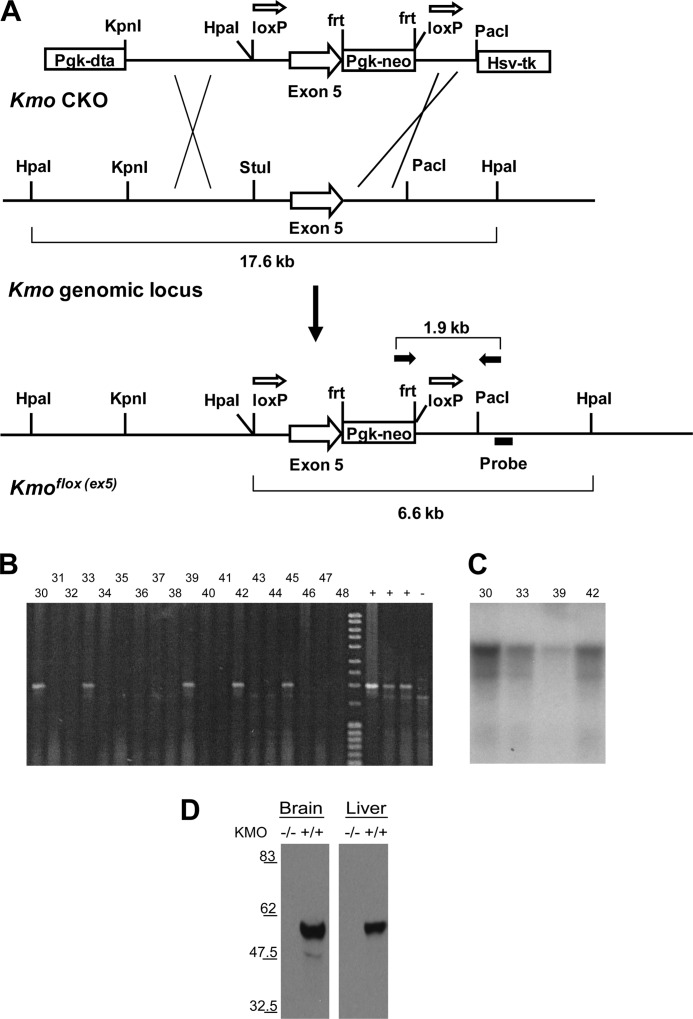

We employed ES cell-based transgenesis to generate transgenic mice with a targeted disruption of the Kmo gene. The Kmo targeting construct was designed with exon 5 of the Kmo locus flanked by loxP sites (Fig. 2A), such that Cre-mediated recombination is predicted to delete exon 5 and generate a putative null allele—a nonsense frameshift mutation with a premature stop in exon 7, which is expected to lead to nonsense-mediated degradation of the mutant mRNA. In combination with Cre recombinase, the Cre/loxP system allows for tissue-specific and temporal deletion of a candidate DNA sequence. Homologous recombination in murine ES cells was used to generate a putative conditional loxP allele of Kmo (Kmoflox(ex5)) as described (38). Correct targeting of the construct was confirmed by PCR and Southern hybridization (Fig. 2, B and C).

FIGURE 2.

Generation and characterization of Kmo knock-out mice. A, schematic of the targeting construct (Kmo CKO), the wild-type Kmo genomic locus, and the conditional allele of Kmo. Open arrows above loxP sites denote orientation of sites. Crosses indicate sites of homologous recombination between the arms of the targeting construct and the Kmo genomic locus. PCR primers (FP2 and RP2) used for the identification of homologous integrants are depicted as solid arrows above the Kmoflox (ex5) allele. The Southern hybridization probe used for confirmation of homologous integrants is indicated below the depiction of the Kmoflox (ex5) allele. B, screening of ES cell clone genomic DNAs by PCR amplification. Positive DNAs using FP2 and RP2 primers produce amplification products of 1.9 kb. C, HpaI digest and Southern blot of ES cells DNAs. The probe detects the presence of the 17.6-kb HpaI fragment in wild-type C57BL/6 genomic DNA. Correctly targeted ES cell clones are heterozygous for the conditional allele (clones 5 and 14 shown here) and contain both a wild-type 17.6-kb HpaI fragment and a 6.6-kb HpaI fragment indicative of a correctly targeted allele. D, detection of KMO by immunoblotting in the brain and liver. Mice homozygous for the deletion allele (Kmo−/−) lack KMO.

Mice carrying the (Kmoflox(ex5)) allele were hypomorphic for KMO activity (data not shown), likely because of the presence of the neomycin resistance cassette (NeoR) in intronic sequences (38). A true Kmo conditional allele (Kmoflox(ex)5-NeoRΔ) was generated by excision of the NeoR cassette, which is flanked by FRT recombination sites (see “Experimental Procedures”). Mice carrying the Kmoflox(ex)5-NeoRΔ allele were mated to transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase ubiquitously under the β-actin promoter to generate progeny lacking KMO systemically and throughout all developmental stages (hereafter referred to as Kmo−/− mice). We confirmed correct targeting of the Kmo locus by analysis of KMO protein levels in the brain and liver by immunoblotting, finding that Kmo−/− mice did not express KMO protein in either the brain or the liver (Fig. 2D). Notably, elimination of KMO activity in Kmo−/− mice did not cause embryonic lethality, did not lead to overt phenotypic abnormalities during postnatal development or in adulthood, and did not influence breeding or normal Mendelian inheritance (data not shown).

KP Enzymes and Metabolites in the Liver of Kmo−/− Mice

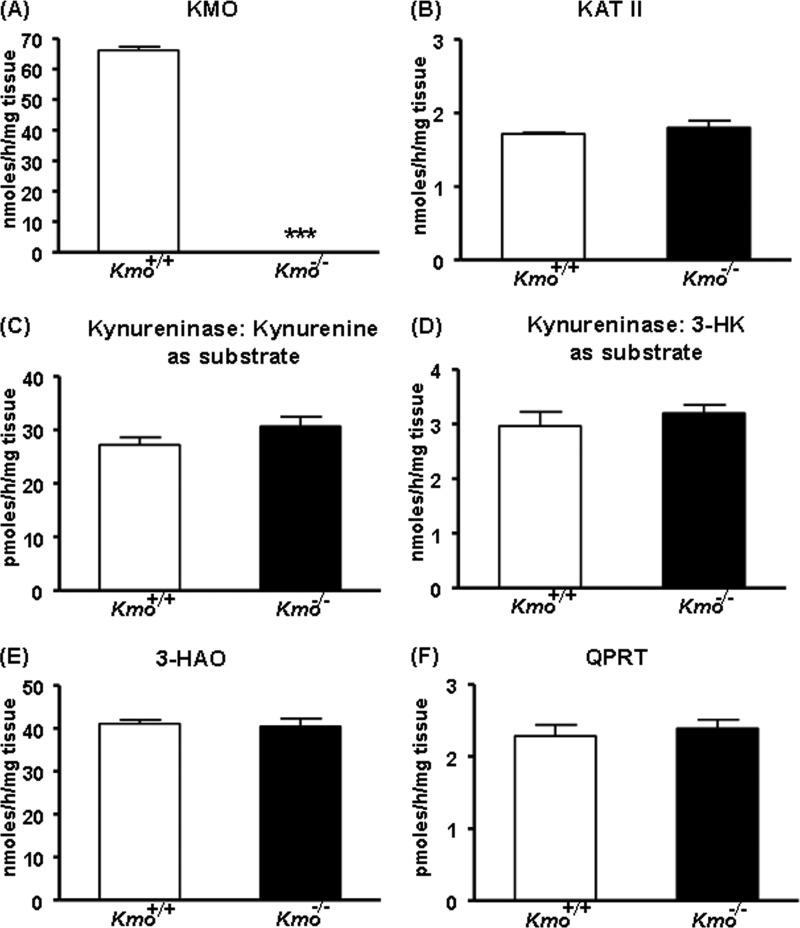

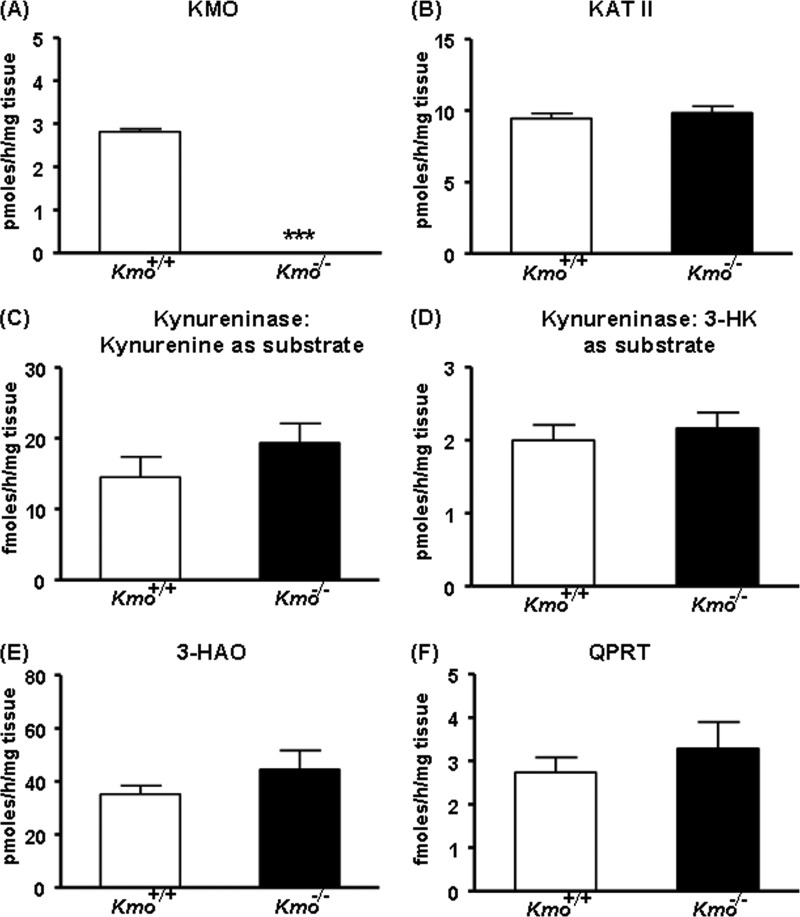

We next determined KMO activity in the liver of ∼2-month-old mice and observed that enzyme activity was eliminated in the Kmo−/− mice (Fig. 3A). This indicated that KMO is the sole enzyme responsible for catalyzing the production of 3-HK from kynurenine in the mouse liver. Aside from KMO, none of the KP enzymes tested (KAT II, kynureninase (using either kynurenine or 3-HK as substrate), 3-HAO, and QPRT) displayed significant changes in activity in Kmo−/− mice compared with wild-type (Kmo+/+) mice of the same age (Fig. 3, B–F). As expected, KMO activity was ∼50% of wild-type levels in brain and liver tissues of Kmo+/− mice (data not shown). A detailed analysis of these mice will be presented elsewhere.4

FIGURE 3.

KP enzyme activities in the liver. A, KMO activity is eliminated in Kmo−/− mice. B–F, compared with wild-type (Kmo+/+) mice, the activities of KAT II, kynureninase (using either kynurenine or 3-HK as a substrate), 3-HAO, and QPRT are unchanged in Kmo−/− mice. The data are the means ± S.E. (n = 6–7/group). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001 versus Kmo+/+.

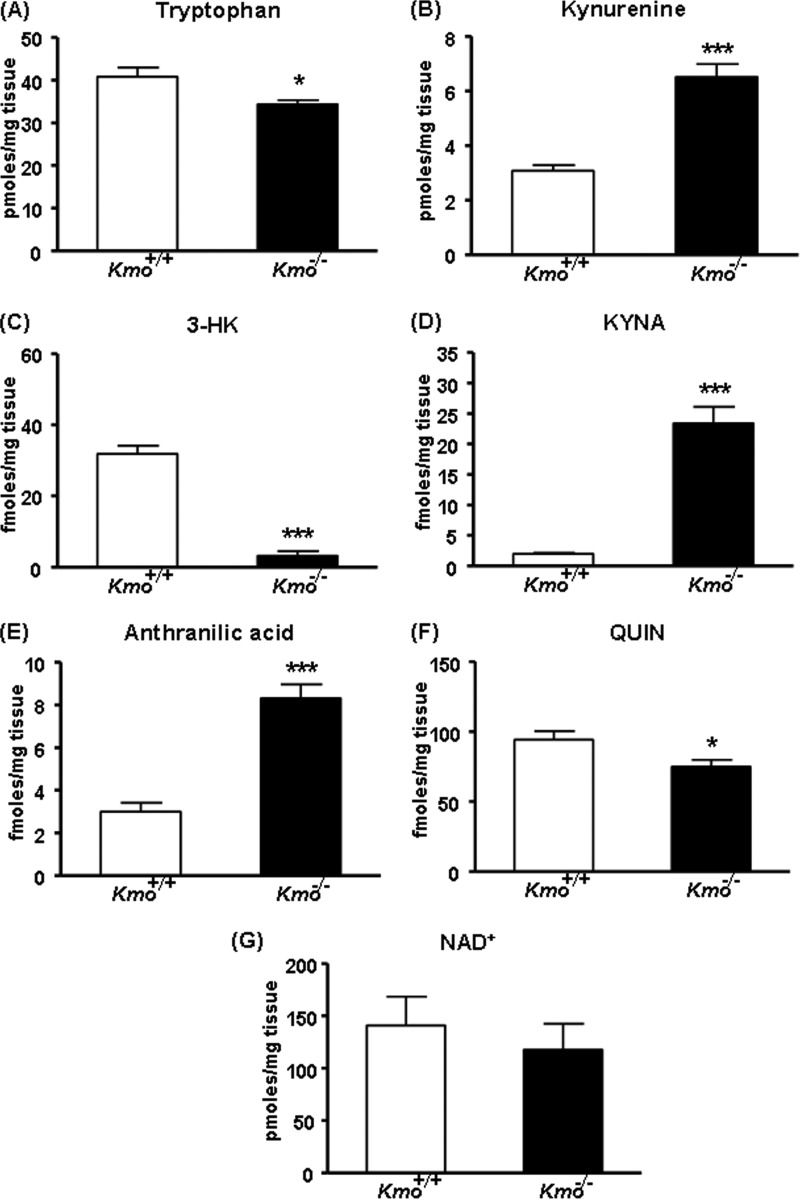

The hepatic levels of tryptophan tended to be lower in Kmo−/− mice than in Kmo+/+ littermate controls, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4A). In contrast, levels of kynurenine, the substrate of KMO, were significantly increased (∼5-fold) in Kmo−/− mice (Fig. 4B), whereas levels of the KMO product (3-HK) and its downstream metabolite (QUIN) were reduced to 42 and 3%, respectively, of wild-type levels (Fig. 4, C and F). Thus, despite the elimination of KMO, 3-HK was still detected in the liver of the mutant mice. Hepatic NAD+ levels were slightly, but not significantly, lower in Kmo−/− compared with Kmo+/+ mice (Fig. 4G). In line with the elevated kynurenine content, the levels of KYNA (the product of the irreversible transamination of kynurenine by KAT) and anthranilic acid (the product of kynureninase) were significantly increased (∼69- and ∼5-fold, respectively) in the liver of Kmo−/− mice (Fig. 4, D and E).

FIGURE 4.

KP metabolites in the liver. A, compared with wild-type (Kmo+/+) controls, the levels of tryptophan are unchanged in Kmo−/− mice. B, D, and E, compared with Kmo+/+ mice, the levels of kynurenine, KYNA, and anthranilic acid are significantly elevated in Kmo−/− mice. C, the levels of 3-HK are significantly reduced in Kmo−/− mice, F, QUIN levels are eliminated in Kmo−/− mice. G, the levels of NAD+ are unchanged in Kmo−/− mice. The data are the means ± S.E. (n = 5–9/group). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001 versus Kmo+/+.

KP Metabolites in the Plasma of Kmo−/− Mice

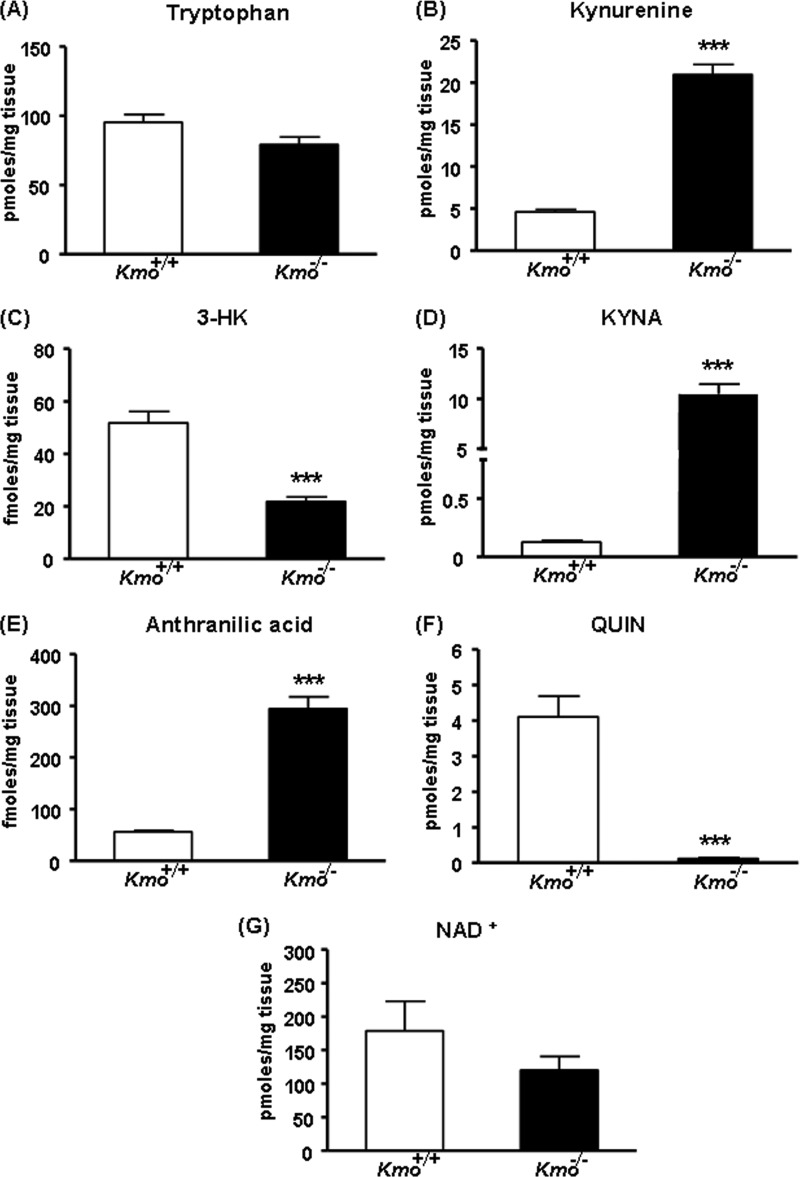

Compared with controls, the concentrations of kynurenine (∼17-fold), KYNA (∼159-fold), and anthranilic acid (∼4-fold) were substantially increased in the plasma of Kmo−/− mice, whereas 3-HK and QUIN levels were greatly reduced (Fig. 5, A–E). Still, as in the liver, considerable residual levels of 3-HK were detected in the plasma of Kmo−/− mice (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

KP metabolites in plasma. A, C, and D, compared with wild-type (Kmo+/+) controls, the levels of kynurenine (A), KYNA (C), and anthranilic acid (D) are significantly elevated in Kmo−/− mice. B, levels of 3-HK are greatly reduced in Kmo−/− mice. E, QUIN is essentially eliminated in Kmo−/− mice. The data are the means ± S.E. (n = 5–9/group). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus Kmo+/+.

KP Enzymes and Metabolites in the Brains of Kmo−/− Mice

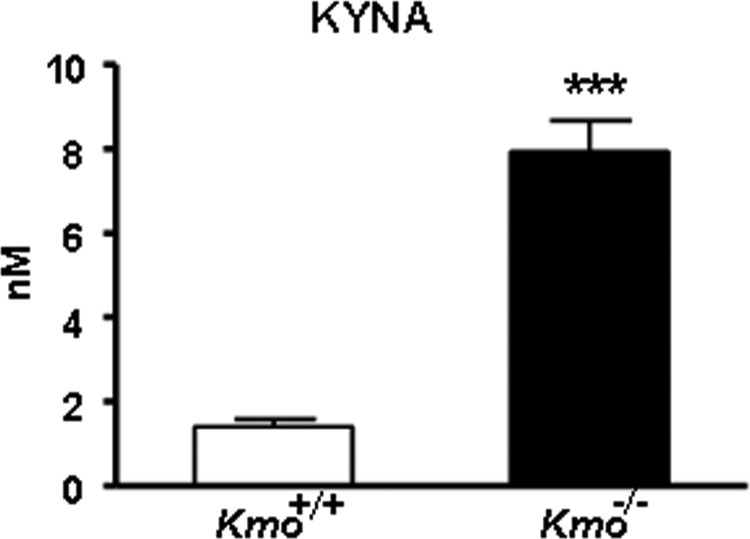

Similar to the liver, brain KMO activity was abolished in the Kmo−/− mutants (Fig. 6A), whereas none of the other KP enzyme activities (KAT II, kynureninase, 3-HAO, and QPRT) differed between genotypes (Fig. 6, B–F). However, examination of KP metabolites in the brain revealed remarkable differences from the periphery. Thus, cerebral 3-HK levels in the knock-out animals were very low (∼10% of wild-type controls; Fig. 7C), whereas QUIN levels were only slightly reduced (to ∼80% of Kmo+/+ controls) (Fig. 7F). Moreover, although brain KYNA levels were elevated (∼12-fold) in Kmo−/− mice (Fig. 7D), this increase was far less pronounced than in the periphery (cf. Figs. 4D and 5C). Similar to the results obtained in the liver, the brain levels of tryptophan were modestly decreased in Kmo−/− mice, kynurenine and anthranilic acid levels were significantly elevated (∼2- and ∼3-fold, respectively; Fig. 7, A, B, and E), and NAD+ levels were not significantly different from Kmo+/+ controls (Fig. 7G).

FIGURE 6.

KP enzyme activities in brain. A, KMO activity is eliminated in cortical homogenates of Kmo−/− mice. B–F, compared with wild-type (Kmo+/+) mice, the activities of KAT II, kynureninase (using either kynurenine or 3-HK as a substrate), 3-HAO, and QPRT are unchanged in Kmo−/− mice. The data are the means ± S.E. (n = 6–8/group). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001 versus Kmo+/+.

FIGURE 7.

KP metabolites in brain. A, compared with wild-type (Kmo+/+) controls, tryptophan levels are slightly reduced in the brain of Kmo−/− mice. B, D, and E, the levels of kynurenine (B), KYNA (D), and anthranilic acid (E) are significantly elevated in Kmo−/− mice. C, the levels of 3-HK are significantly reduced in the mutant animals. F, Kmo−/− mice exhibit a moderate, but significant, reduction in QUIN levels compared with Kmo+/+ controls. G, no significant differences between the levels of NAD+ in Kmo+/+and Kmo−/− genotypes. The data are the means ± S.E. (n = 6–7/group). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 versus Kmo+/+.

Extracellular Levels of KYNA in the Striatum of Kmo−/− Mice

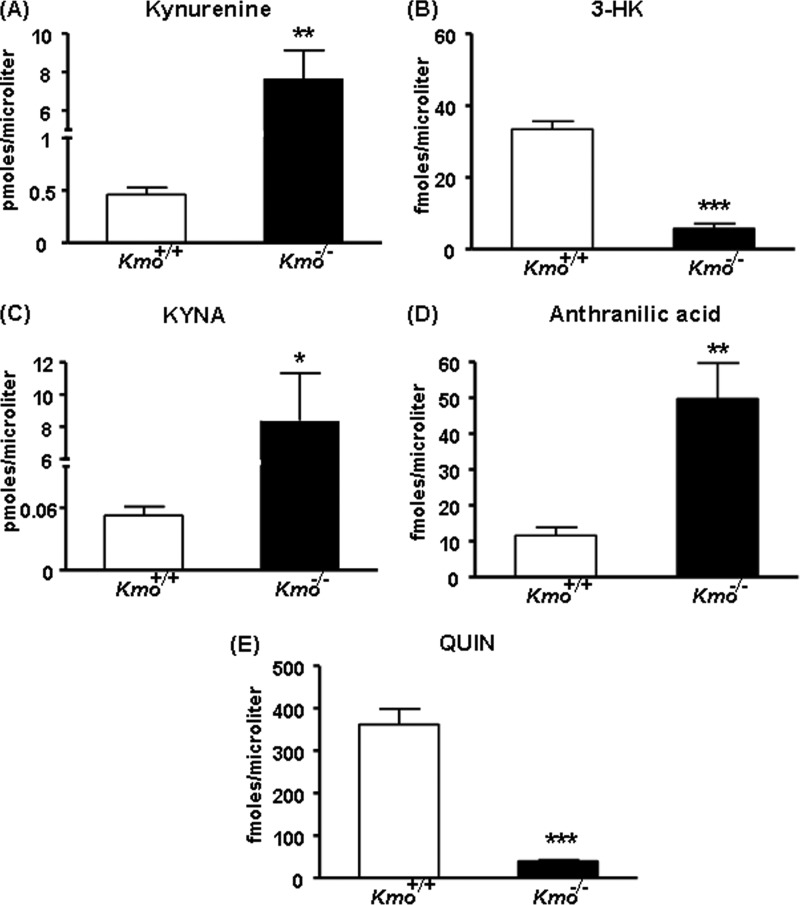

We next performed in vivo microdialysis in the striatum of awake, behaving mice to measure basal extracellular KYNA in Kmo−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 8, which illustrates basal levels averaged over an 8-h collection period, KYNA levels were significantly increased (∼6-fold) in the mutant animals compared with wild-type controls.

FIGURE 8.

Extracellular KYNA levels in the brain. KYNA was determined by in vivo microdialysis in the striatum of wild-type (Kmo+/+) and Kmo−/− mice. See text for experimental details. The data were compiled by using the average of eight hourly microdialysis samples from each animal and are expressed as the means ± S.E. (n = 8/group). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001 versus Kmo+/+.

DISCUSSION

We describe here the generation and characterization of Kmo−/− mice, confirming that genetic disruption of the Kmo locus is sufficient to eliminate KMO detection by immunoblotting and to reduce enzymatic activity in brain and liver to undetectable levels. Although 3-HK was still clearly measurable in the mutant animals and our study therefore does not categorically rule out the existence of functional KMO isoforms, this indicates that a single KMO is largely responsible for the production of 3-HK from kynurenine in mice. Moreover, none of the other KP enzymes analyzed in liver and brain showed any significant changes in adult Kmo−/− mice. The mutant mice were viable and overtly healthy, demonstrating that the deleted KMO was not essential for embryonic and postnatal survival.

Tryptophan levels were marginally reduced in the brain, but not in the liver, of knock-out compared with wild-type mice, suggesting that the elimination of KMO has only a small effect on the activity of the upstream enzymes, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, which initiate catabolism along the KP (Fig. 1). However, further analysis of Kmo−/− mice revealed several biochemical features that support the idea that KMO normally plays a critical role in the regulation of KP metabolism. Thus, the steady-state levels of kynurenine, the substrate of KMO, were substantially increased both in the periphery and in the brain of the mutant animals. It is likely that this, in turn, accounted for the fact that the levels of two primary degradation products of kynurenine, KYNA and anthranilic acid, were also significantly elevated in Kmo−/− mice. Notably, these effects did not involve changes in the activities of KAT II and kynureninase, the enzymes that catalyze the formation of KYNA and anthranilic acid, respectively, from kynurenine (Fig. 1). Thus, the accumulation of KYNA and anthranilic acid in Kmo−/− mice further suggests that KATs and kynureninase are operating below saturation under physiologic conditions.

Although the levels of 3-HK, the product of KMO, were substantially reduced in the liver, serum, and brain of Kmo−/− mice, specific deletion of the enzyme did not totally eliminate 3-HK from either of the three tissues examined. The liver of mutant animals, in particular, contained considerable residual 3-HK (Fig. 4C), and additional studies will be required to identify both its source and its possible functional significance.

Interestingly, our study revealed substantial quantitative differences in KP metabolism between the periphery and the brain as a result of the KMO deletion. For example, the increase in KYNA levels in Kmo−/− mice was far more pronounced in the liver and even more so in the plasma, than in the brain, whereas the increases in the levels of anthranilic acid in the same animals were of comparable magnitude (∼3–5-fold) in periphery and brain. This phenomenon may be related to the fact that in the brain KAT II is contained in astrocytes, whereas KMO and kynureninase are localized in microglial cells (5, 47). The cellular segregation of the two KP arms, which does not exist in the periphery, may therefore prevent the preferential conversion of kynurenine to KYNA in the brain of Kmo−/− mice.

The quantitatively similar increase in anthranilic acid levels in brain and periphery of mutant mice probably accounted for the fact that only a ∼20% reduction in QUIN levels was observed in the brain of Kmo−/− compared with wild-type mice, whereas QUIN was practically eliminated in the liver and plasma of the same animals (cf. Figs. 4, 5, and 7). Thus, in stark contrast to the periphery, anthranilic acid is far superior to 3-HK as a bioprecursor of 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid in the brain (48) and should therefore be much better suited to sustain cerebral QUIN levels when 3-HK formation is compromised. Our results also may indicate that the anthranilic acid branch of KP metabolism is the minor pathway for kynurenine catabolism in all tissues. Interestingly, in brains of Kmo−/− mice, the anthranilic acid to QUIN conversion is likely the dominant pathway for QUIN formation and may represent a compensatory mechanism to form QUIN when KMO activity is compromised. More importantly, our results indicate surprisingly that pharmacological inhibition of KMO in the brain is unlikely to dramatically lower QUIN levels, suggesting that peripheral inhibition of KMO may be sufficient to confer neuroprotection (30). Unfortunately, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid levels were below the limits of assay sensitivity in the present study and were therefore not available for testing this hypothesis directly. However, we examined whether the differential effects of KMO deletion on QUIN levels in brain and liver carried over to the important downstream metabolite NAD+. No significant differences in NAD+ content were seen between wild-type and mutant animals in either tissue, supporting the notion that alternative mechanisms readily maintain normal levels of NAD+, even when the KP is severely compromised by elimination of KMO (49–51).

Work in a large number of in vivo and in vitro model systems has revealed that kynurenine itself, as well as several KP metabolites, acting through a remarkably broad array of biological mechanisms (28, 52), normally operate as signaling molecules in physiological processes ranging from immune regulation (53) to cognitive functions (20). Although not investigated here, the newly generated Kmo−/− mice can therefore be expected to have abnormalities that are related to the impairments in KP metabolites described in the present study. Thus, in the periphery, the massive reduction in QUIN may compromise the function of the spleen and lymphoid tissue (54), and increased KYNA may adversely influence the function of endothelial cells (55). Functional consequences of fluctuations in KP metabolites are best documented in the brain, where decreased 3-HK and elevated KYNA levels are known to reduce neuronal vulnerability (16, 20). Notably, increased brain KYNA levels also cause a variety of distinct cognitive impairments (56–59). In a preliminary study evaluating such possible abnormalities in Kmo−/− mice, which may be a direct consequence of the increase in extracellular KYNA levels in the brain (Fig. 8), we indeed observed a pronounced deficit in contextual memory in the mutant animals (60).

Related to their role(s) in physiology, peripheral and central KP metabolites have recently received considerable attention as potential agents in human diseases ranging from cancer (61) to intestinal syndromes (62) and disorders of the endocrine (63), immune (64, 65), and central nervous systems (20, 66–69). Causal connections have been postulated either because genetic or biochemical KP abnormalities were found in specimens obtained from patients, as in schizophrenia (70–76), or because studies in animals had predicted etiologically significant links. In some instances, such as the neurodegenerative disorder Huntington disease, the case for causality is strengthened by converging evidence from both human tissues and relevant animal models (77, 78).

These insights and hypotheses, in turn, stimulated efforts to target individual KP enzymes pharmacologically to normalize functional impairments caused by KP metabolites. A rich armamentarium of selective and potent enzyme inhibitors is now available, and these compounds are not only used as experimental tools but also hold considerable promise as therapeutic agents in a number of human diseases (see Refs. 1, 20, 29, and 67 for recent reviews). Because of its pivotal position in the KP, KMO has attracted special attention in this regard. Mostly tested in the neurosciences so far, specific KMO inhibitors, including the prototypical Ro 61-8048 (35), indeed have significant biological activity in vivo. These studies have revealed, for example, anticonvulsive, neuroprotective, and anti-dyskinetic effects of KMO inhibition (30, 66, 79, 80) and led to the acceptance of KMO as a bona fide drug target (37). Notably, genetic elimination of KMO suppresses toxicity in yeast and Drosophila models of Huntington disease (32, 81), suggesting that Kmo−/− mice, too, may show resistance to endogenous or external insults. Nonetheless, pharmacological inhibition of KMO might also lead to undesirable consequences on the nervous and immune systems (20) that will have to be evaluated carefully in animals prior to clinical studies in humans.

In summary, the newly produced Kmo−/− mice should be an attractive experimental tool for the further elucidation of the role of the KP in mammalian physiology and pathology. This role involves the bi-directional cross-talk between periphery and brain (20), so that gene deletion in individual tissues will be of significant interest. Because our Kmo−/− mice were generated using the Cre/loxP system, studies currently in progress therefore target deletion of the Kmo locus in specific organs to characterize the regulatory functions of the enzyme in distinct biological compartments.

Acknowledgment

We thank Erin Stachowski for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants NS057715 and AG022074 from the United States Public Health Service.

K. V. Sathyasaikumar, F. M. Notarangelo, F. Giorgini, P. J. Muchowski, and R. Schwarcz, unpublished observations.

- KP

- kynurenine pathway

- 3-HAO

- 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid dioxygenase

- 3-HK

- 3-hydroxykynurenine

- KAT II

- kynurenine aminotransferase II

- KMO

- kynurenine 3-monooxygenase

- KYNA

- kynurenic acid

- QPRT

- quinolinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase

- QUIN

- quinolinic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thevandavakkam M. A., Schwarcz R., Muchowski P. J., Giorgini F. (2010) Targeting kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO). Implications for therapy in Huntington's disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 9, 791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leklem J. E. (1971) Quantitative aspects of tryptophan metabolism in humans and other species. A review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 24, 659–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heyes M. P., Saito K., Markey S. P. (1992) Human macrophages convert l-tryptophan into the neurotoxin quinolinic acid. Biochem. J. 283, 633–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De Castro F. T., Brown R. R., Price J. M. (1957) The intermediary metabolism of tryptophan by cat and rat tissue preparations. J. Biol. Chem. 228, 777–784 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guillemin G. J., Kerr S. J., Smythe G. A., Smith D. G., Kapoor V., Armati P. J., Croitoru J., Brew B. J. (2001) Kynurenine pathway metabolism in human astrocytes. A paradox for neuronal protection. J. Neurochem. 78, 842–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giorgini F., Möller T., Kwan W., Zwilling D., Wacker J. L., Hong S., Tsai L. C., Cheah C. S., Schwarcz R., Guidetti P., Muchowski P. J. (2008) Histone deacetylase inhibition modulates kynurenine pathway activation in yeast, microglia, and mice expressing a mutant huntingtin fragment. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7390–7400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alberati-Giani D., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Köhler C., Cesura A. M. (1996) Regulation of the kynurenine pathway by IFN-γ in murine cloned macrophages and microglial cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 398, 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Connor T. J., Starr N., O'Sullivan J. B., Harkin A. (2008) Induction of indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase and kynurenine 3-monooxygenase in rat brain following a systemic inflammatory challenge. A role for IFN-γ? Neurosci. Lett. 441, 29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Opitz C. A., Litzenburger U. M., Sahm F., Ott M., Tritschler I., Trump S., Schumacher T., Jestaedt L., Schrenk D., Weller M., Jugold M., Guillemin G. J., Miller C. L., Lutz C., Radlwimmer B., Lehmann I., von Deimling A., Wick W., Platten M. (2011) An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 478, 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nguyen N. T., Kimura A., Nakahama T., Chinen I., Masuda K., Nohara K., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Kishimoto T. (2010) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor negatively regulates dendritic cell immunogenicity via a kynurenine-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19961–19966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y., Liu H., McKenzie G., Witting P. K., Stasch J. P., Hahn M., Changsirivathanathamrong D., Wu B. J., Ball H. J., Thomas S. R., Kapoor V., Celermajer D. S., Mellor A. L., Keaney J. F., Jr., Hunt N. H., Stocker R. (2010) Kynurenine is an endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced during inflammation. Nat. Med. 16, 279–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Opitz C. A., Litzenburger U. M., Opitz U., Sahm F., Ochs K., Lutz C., Wick W., Platten M. (2011) The indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitor 1-methyl-d-tryptophan upregulates IDO1 in human cancer cells. PLoS One 6, e19823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mezrich J. D., Fechner J. H., Zhang X., Johnson B. P., Burlingham W. J., Bradfield C. A. (2010) An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 185, 3190–3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ishii T., Iwahashi H., Sugata R., Kido R. (1992) Formation of hydroxanthommatin-derived radical in the oxidation of 3-hydroxykynurenine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 294, 616–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hiraku Y., Inoue S., Oikawa S., Yamamoto K., Tada S., Nishino K., Kawanishi S. (1995) Metal-mediated oxidative damage to cellular and isolated DNA by certain tryptophan metabolites. Carcinogenesis 16, 349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Colín-González A. L., Maldonado P. D., Santamaría A. (2013) 3-Hydroxykynurenine. An intriguing molecule exerting dual actions in the central nervous system. Neurotoxicology 34, 189–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morita T., Saito K., Takemura M., Maekawa N., Fujigaki S., Fujii H., Wada H., Takeuchi S., Noma A., Seishima M. (2001) 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid, an l-tryptophan metabolite, induces apoptosis in monocyte-derived cells stimulated by interferon-γ. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 38, 242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rios C., Santamaria A. (1991) Quinolinic acid is a potent lipid peroxidant in rat brain homogenates. Neurochem. Res. 16, 1139–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stone T. W., Perkins M. N. (1981) Quinolinic acid. A potent endogenous excitant at amino acid receptors in CNS. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 72, 411–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwarcz R., Bruno J. P., Muchowski P. J., Wu H. Q. (2012) Kynurenines in the mammalian brain. When physiology meets pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 465–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hilmas C., Pereira E. F., Alkondon M., Rassoulpour A., Schwarcz R., Albuquerque E. X. (2001) The brain metabolite kynurenic acid inhibits α7 nicotinic receptor activity and increases non-α7 nicotinic receptor expression. Physiopathological implications. J. Neurosci. 21, 7463–7473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kessler M., Terramani T., Lynch G., Baudry M. (1989) A glycine site associated with N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptors. Characterization and identification of a new class of antagonists. J. Neurochem. 52, 1319–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang J., Simonavicius N., Wu X., Swaminath G., Reagan J., Tian H., Ling L. (2006) Kynurenic acid as a ligand for orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR35. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22021–22028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DiNatale B. C., Murray I. A., Schroeder J. C., Flaveny C. A., Lahoti T. S., Laurenzana E. M., Omiecinski C. J., Perdew G. H. (2010) Kynurenic acid is a potent endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that synergistically induces interleukin-6 in the presence of inflammatory signaling. Toxicol. Sci. 115, 89–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lugo-Huitrón R., Blanco-Ayala T., Ugalde-Muñiz P., Carrillo-Mora P., Pedraza-Chaverrí J., Silva-Adaya D., Maldonado P. D., Torres I., Pinzón E., Ortiz-Islas E., López T., García E., Pineda B., Torres-Ramos M., Santamaría A., De La Cruz V. P. (2011) On the antioxidant properties of kynurenic acid. Free radical scavenging activity and inhibition of oxidative stress. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 33, 538–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Foster A. C., Vezzani A., French E. D., Schwarcz R. (1984) Kynurenic acid blocks neurotoxicity and seizures induced in rats by the related brain metabolite quinolinic acid. Neurosci. Lett. 48, 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andiné P., Lehmann A., Ellrén K., Wennberg E., Kjellmer I., Nielsen T., Hagberg H. (1988) The excitatory amino acid antagonist kynurenic acid administered after hypoxic-ischemia in neonatal rats offers neuroprotection. Neurosci. Lett. 90, 208–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moroni F., Cozzi A., Sili M., Mannaioni G. (2012) Kynurenic acid. A metabolite with multiple actions and multiple targets in brain and periphery. J. Neural Transm. 119, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Costantino G. (2009) New promises for manipulation of kynurenine pathway in cancer and neurological diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 13, 247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zwilling D., Huang S. Y., Sathyasaikumar K. V., Notarangelo F. M., Guidetti P., Wu H. Q., Lee J., Truong J., Andrews-Zwilling Y., Hsieh E. W., Louie J. Y., Wu T., Scearce-Levie K., Patrick C., Adame A., Giorgini F., Moussaoui S., Laue G., Rassoulpour A., Flik G., Huang Y., Muchowski J. M., Masliah E., Schwarcz R., Muchowski P. J. (2011) Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase inhibition in blood ameliorates neurodegeneration. Cell 145, 863–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wonodi I., Schwarcz R. (2010) Cortical kynurenine pathway metabolism. A novel target for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 36, 211–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campesan S., Green E. W., Breda C., Sathyasaikumar K. V., Muchowski P. J., Schwarcz R., Kyriacou C. P., Giorgini F. (2011) The kynurenine pathway modulates neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of Huntington's disease. Curr. Biol. 21, 961–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carpenedo R., Chiarugi A., Russi P., Lombardi G., Carlà V., Pellicciari R., Mattoli L., Moroni F. (1994) Inhibitors of kynurenine hydroxylase and kynureninase increase cerebral formation of kynurenate and have sedative and anticonvulsant activities. Neuroscience 61, 237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Speciale C., Wu H. Q., Cini M., Marconi M., Varasi M., Schwarcz R. (1996) (R,S)-3,4-dichlorobenzoylalanine (FCE 28833A) causes a large and persistent increase in brain kynurenic acid levels in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 315, 263–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Röver S., Cesura A. M., Huguenin P., Kettler R., Szente A. (1997) Synthesis and biochemical evaluation of N-(4-phenylthiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamides as high-affinity inhibitors of kynurenine 3-hydroxylase. J. Med. Chem. 40, 4378–4385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amori L., Guidetti P., Pellicciari R., Kajii Y., Schwarcz R. (2009) On the relationship between the two branches of the kynurenine pathway in the rat brain in vivo. J. Neurochem. 109, 316–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amaral M., Levy C., Heyes D. J., Lafite P., Outeiro T. F., Giorgini F., Leys D., Scrutton N. S. (2013) Structural basis of kynurenine 3-monooxygenase inhibition. Nature 496, 382–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meyers E. N., Lewandoski M., Martin G. R. (1998) An Fgf8 mutant allelic series generated by Cre- and Flp-mediated recombination. Nat. Genet. 18, 136–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodríguez C. I., Buchholz F., Galloway J., Sequerra R., Kasper J., Ayala R., Stewart A. F., Dymecki S. M. (2000) High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat. Genet. 25, 139–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lewandoski M., Meyers E. N., Martin G. R. (1997) Analysis of Fgf8 gene function in vertebrate development. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 62, 159–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heyes M. P., Quearry B. J. (1988) Quantification of 3-hydroxykynurenine in brain by high-performance liquid chromatography and electrochemical detection. J. Chromatogr. 428, 340–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Foster A. C., White R. J., Schwarcz R. (1986) Synthesis of quinolinic acid by 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid oxygenase in rat brain tissue in vitro. J. Neurochem. 47, 23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Foster A. C., Zinkand W. C., Schwarcz R. (1985) Quinolinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 44, 446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cannazza G., Chiarugi A., Parenti C., Zanoli P., Baraldi M. (2001) Changes in kynurenic, anthranilic, and quinolinic acid concentrations in rat brain tissue during development. Neurochem. Res. 26, 511–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Notarangelo F. M., Wu H. Q., Macherone A., Graham D. R., Schwarcz R. (2012) Gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry detection of extracellular kynurenine and related metabolites in normal and lesioned rat brain. Anal. Biochem. 421, 573–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rassoulpour A., Wu H. Q., Ferré S., Schwarcz R. (2005) Nanomolar concentrations of kynurenic acid reduce extracellular dopamine levels in the striatum. J. Neurochem. 93, 762–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heyes M. P., Achim C. L., Wiley C. A., Major E. O., Saito K., Markey S. P. (1996) Human microglia convert l-tryptophan into the neurotoxin quinolinic acid. Biochem. J. 320, 595–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baran H., Schwarcz R. (1990) Presence of 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid in rat tissues and evidence for its production from anthranilic acid in the brain. J. Neurochem. 55, 738–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Terakata M., Fukuwatari T., Kadota E., Sano M., Kanai M., Nakamura T., Funakoshi H., Shibata K. (2013) The niacin required for optimum growth can be synthesized from l-tryptophan in growing mice lacking tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase. J. Nutr. 143, 1046–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Belenky P., Bogan K. L., Brenner C. (2007) NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Terakata M., Fukuwatari T., Sano M., Nakao N., Sasaki R., Fukuoka S., Shibata K. (2012) Establishment of true niacin deficiency in quinolinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase knockout mice. J. Nutr. 142, 2148–2153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stone T. W., Stoy N., Darlington L. G. (2013) An expanding range of targets for kynurenine metabolites of tryptophan. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34, 136–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mándi Y., Vécsei L. (2012) The kynurenine system and immunoregulation. J. Neural Transm. 119, 197–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moffett J. R., Espey M. G., Namboodiri M. A. (1994) Antibodies to quinolinic acid and the determination of its cellular distribution within the rat immune system. Cell Tissue Res. 278, 461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wejksza K., Rzeski W., Turski W. A. (2009) Kynurenic acid protects against the homocysteine-induced impairment of endothelial cells. Pharmacol. Rep. 61, 751–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shepard P. D., Joy B., Clerkin L., Schwarcz R. (2003) Micromolar brain levels of kynurenic acid are associated with a disruption of auditory sensory gating in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 1454–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Erhardt S., Schwieler L., Emanuelsson C., Geyer M. (2004) Endogenous kynurenic acid disrupts prepulse inhibition. Biol. Psychiatry 56, 255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chess A. C., Simoni M. K., Alling T. E., Bucci D. J. (2007) Elevations of endogenous kynurenic acid produce spatial working memory deficits. Schizophr. Bull. 33, 797–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chess A. C., Landers A. M., Bucci D. J. (2009) l-Kynurenine treatment alters contextual fear conditioning and context discrimination but not cue-specific fear conditioning. Behav. Brain Res. 201, 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Thomas M., Pocivavsek A., Sathyasaikumar K. V., Elmer G. I., Giorgini F., Muchowski P. J., Schwarcz R. (2012) Behavioral abnormalities in mice deficient in kynurenine 3-monooxygenase. Relevance to schizophrenia. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 37, 663.29 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Prendergast G. C., Chang M. Y., Mandik-Nayak L., Metz R., Muller A. J. (2011) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase as a modifier of pathogenic inflammation in cancer and other inflammation-associated diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 2257–2262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kaszaki J., Erces D., Varga G., Szabó A., Vécsei L., Boros M. (2012) Kynurenines and intestinal neurotransmission. The role of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. J. Neural Transm. 119, 211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oxenkrug G. F. (2011) Interferon-γ-inducible kynurenines/pteridines inflammation cascade. Implications for aging and aging-associated psychiatric and medical disorders. J. Neural Transm. 118, 75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Heyes M. P., Brew B. J., Saito K., Quearry B. J., Price R. W., Lee K., Bhalla R. B., Der M., Markey S. P. (1992) Inter-relationships between quinolinic acid, neuroactive kynurenines, neopterin and β2-microglobulin in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of HIV-1-infected patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 40, 71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Romani L., Fallarino F., De Luca A., Montagnoli C., D'Angelo C., Zelante T., Vacca C., Bistoni F., Fioretti M. C., Grohmann U., Segal B. H., Puccetti P. (2008) Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature 451, 211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cozzi A., Carpenedo R., Moroni F. (1999) Kynurenine hydroxylase inhibitors reduce ischemic brain damage. Studies with (m-nitrobenzoyl)-alanine (mNBA) and 3,4-dimethoxy-[-N-4-(nitrophenyl)thiazol-2yl]-benzenesulfonamide (Ro 61-8048) in models of focal or global brain ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 19, 771–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vécsei L., Szalárdy L., Fülöp F., Toldi J. (2013) Kynurenines in the CNS. Recent advances and new questions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 64–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stone T. W., Forrest C. M., Stoy N., Darlington L. G. (2012) Involvement of kynurenines in Huntington's disease and stroke-induced brain damage. J. Neural. Transm. 119, 261–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chen Y., Guillemin G. J. (2009) Kynurenine pathway metabolites in humans. Disease and healthy states. Int. J. Tryptophan. Res. 2, 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wonodi I., Stine O. C., Sathyasaikumar K. V., Roberts R. C., Mitchell B. D., Hong L. E., Kajii Y., Thaker G. K., Schwarcz R. (2011) Downregulated kynurenine 3-monooxygenase gene expression and enzyme activity in schizophrenia and genetic association with schizophrenia endophenotypes. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 665–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sathyasaikumar K. V., Stachowski E. K., Wonodi I., Roberts R. C., Rassoulpour A., McMahon R. P., Schwarcz R. (2011) Impaired kynurenine pathway metabolism in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 1147–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Miller C. L., Llenos I. C., Cwik M., Walkup J., Weis S. (2008) Alterations in kynurenine precursor and product levels in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neurochem. Int. 52, 1297–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schwarcz R., Rassoulpour A., Wu H. Q., Medoff D., Tamminga C. A., Roberts R. C. (2001) Increased cortical kynurenate content in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 50, 521–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Müller N., Schwarz M. (2006) Schizophrenia as an inflammation-mediated dysbalance of glutamatergic neurotransmission. Neurotox. Res. 10, 131–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Erhardt S., Schwieler L., Nilsson L., Linderholm K., Engberg G. (2007) The kynurenic acid hypothesis of schizophrenia. Physiol. Behav. 92, 203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Holtze M., Saetre P., Engberg G., Schwieler L., Werge T., Andreassen O. A., Hall H., Terenius L., Agartz I., Jönsson E. G., Schalling M., Erhardt S. (2012) Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase polymorphisms. Relevance for kynurenic acid synthesis in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 37, 53–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Guidetti P., Luthi-Carter R. E., Augood S. J., Schwarcz R. (2004) Neostriatal and cortical quinolinate levels are increased in early grade Huntington's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 17, 455–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Guidetti P., Bates G. P., Graham R. K., Hayden M. R., Leavitt B. R., MacDonald M. E., Slow E. J., Wheeler V. C., Woodman B., Schwarcz R. (2006) Elevated brain 3-hydroxykynurenine and quinolinate levels in Huntington disease mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 190–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chiarugi A., Carpenedo R., Molina M. T., Mattoli L., Pellicciari R., Moroni F. (1995) Comparison of the neurochemical and behavioral effects resulting from the inhibition of kynurenine hydroxylase and/or kynureninase. J. Neurochem. 65, 1176–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Grégoire L., Rassoulpour A., Guidetti P., Samadi P., Bédard P. J., Izzo E., Schwarcz R., Di Paolo T. (2008) Prolonged kynurenine 3-hydroxylase inhibition reduces development of levodopa-induced dyskinesias in parkinsonian monkeys. Behav. Brain Res 186, 161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Giorgini F., Guidetti P., Nguyen Q., Bennett S. C., Muchowski P. J. (2005) A genomic screen in yeast implicates kynurenine 3-monooxygenase as a therapeutic target for Huntington disease. Nat. Genet. 37, 526–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]