Background: In carp cones, 11-cis-retinal and all-trans-retinol are formed with 11-cis-retinol and all-trans-retinal present.

Results: The substrate specificity, reaction mechanism, and subcellular localization of this reaction were determined.

Conclusion: Substrate specificity is high for retinol but low for retinal, and the activity is present in the cone inner segment.

Significance: The possible contribution to efficient pigment regeneration in cones is suggested.

Keywords: Photoreceptors, Retinal Metabolism, Retinoid, Vision, Vitamin A, Cones, Müller Cells, Retinoid Cycle

Abstract

Our previous study suggested the presence of a novel cone-specific redox reaction that generates 11-cis-retinal from 11-cis-retinol in the carp retina. This reaction is unique in that 1) both 11-cis-retinol and all-trans-retinal were required to produce 11-cis-retinal; 2) together with 11-cis-retinal, all-trans-retinol was produced at a 1:1 ratio; and 3) the addition of enzyme cofactors such as NADP(H) was not necessary. This reaction is probably part of the reactions in a cone-specific retinoid cycle required for cone visual pigment regeneration with the use of 11-cis-retinol supplied from Müller cells. In this study, using purified carp cone membrane preparations, we first confirmed that the reaction is a redox-coupling reaction between retinals and retinols. We further examined the substrate specificity, reaction mechanism, and subcellular localization of this reaction. Oxidation was specific for 11-cis-retinol and 9-cis-retinol. In contrast, reduction showed low specificity: many aldehydes, including all-trans-, 9-cis-, 11-cis-, and 13-cis-retinals and even benzaldehyde, supported the reaction. On the basis of kinetic studies of this reaction (aldehyde-alcohol redox-coupling reaction), we found that formation of a ternary complex of a retinol, an aldehyde, and a postulated enzyme seemed to be necessary, which suggested the presence of both the retinol- and aldehyde-binding sites in this enzyme. A subcellular fractionation study showed that the activity is present almost exclusively in the cone inner segment. These results suggest the presence of an effective production mechanism of 11-cis-retinal in the cone inner segment to regenerate visual pigment.

Introduction

In the vertebrate retina, light is detected by rods and cones. Rods mediate night vision, whereas cones mediate day vision. In both cells, a light-absorbing molecule, visual pigment, is composed of a chromophore, 11-cis-retinal, and a protein moiety, opsin. Light isomerizes 11-cis-retinal to all-trans-retinal, which triggers a conformational change in opsin that leads to activation of the phototransduction cascade to generate an electrical response (1, 2). The activated visual pigment then bleaches, decomposes into opsin and all-trans-retinal, and loses its ability to detect light. In both rods and cones, all-trans-retinal released from bleached pigment is reduced to all-trans-retinol. To maintain the ability to detect light in photoreceptors, visual pigments should be regenerated. For regeneration of the pigment, 11-cis-retinal is required: all-trans-retinol formed after bleaching is converted to 11-cis-retinal through a multistep enzymatic process called the retinoid cycle (or the visual cycle). In vertebrate eyes, two pathways of the retinoid cycle are known (3–6). The first and classic cycle includes the reactions found in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).2 In this cycle (the RPE retinoid cycle), all-trans-retinol formed after pigment bleaching in rods and cones is sent to the RPE, where all-trans-retinol is esterified, isomerohydrolyzed, and oxidized to 11-cis-retinal (7–9). The 11-cis-retinal formed is sent back to the rods and cones to regenerate visual pigment. The second and recently discovered pathway is a cone-specific retinoid cycle (the cone retinoid cycle): the reduced all-trans-retinol is sent to Müller cells, where all-trans-retinol is isomerized to 11-cis-retinol (10, 11). The isomerized 11-cis-retinol is sent back to the cones, where 11-cis-retinol is oxidized to 11-cis-retinal to regenerate visual pigments (3, 5, 6).

The cone retinoid cycle has been suggested to contribute significantly to pigment regeneration in cones. According to Mata et al. (12), the maximum rate of the supply of 11-cis-retinal through the RPE retinoid cycle seems to be too low to regenerate the pigment for cones to function under high levels of steady illumination. They estimated that the cone retinoid cycle is 20-fold more effective than the classic RPE retinoid cycle in regenerating the cone pigment. In fact, Kolesnikov et al. (13) reported that, in mouse retina, the cone retinoid cycle promotes M/L-cone dark adaptation 8-fold faster than the RPE retinoid cycle.

In the cone retinoid cycle, 11-cis-retinol supplied from Müller cells is oxidized to 11-cis-retinal in cones (14, 15). It has been suggested that this oxidation is attained by retinol dehydrogenase activities in cones with NADP+ as a cofactor (12). However, in our previous study (16), purified carp cone membranes did not show significant activities of 11-cis-retinol oxidation in the presence of NADP+. Instead, without the addition of enzyme cofactors, a novel reaction showed a high activity of 11-cis-retinal formation in the presence of both 11-cis-retinol and all-trans-retinal. In this reaction, in addition to 11-cis-retinal, all-trans-retinol was produced, and the stoichiometry of the formation of 11-cis-retinal and all-trans-retinol was 1:1. On the basis of these findings, we postulated that, in this reaction, 11-cis-retinol was oxidized to 11-cis-retinal with the concomitant reduction of all-trans-retinal to all-trans-retinol. This postulated retinal (AL) reduction- and retinol (OL) oxidation-coupling reaction (AL-OL coupling reaction) showed a maximum rate of supply of 11-cis-retinal estimated to be 240 times higher than that attained by the RPE retinoid cycle (16). Because such activities were not found in purified carp rods, the AL-OL coupling reaction could be part of the mechanisms that effectively produce 11-cis-retinal from its alcohol in cones in the cone retinoid cycle.

In this study, we first confirmed that the reaction is actually a redox-coupling reaction between retinols and retinals. Then, to further characterize the AL-OL coupling reaction, we examined the substrate specificities of both oxidation and reduction, the reaction mechanism, and the subcellular localization of the activity. Oxidation was found to be specific for 11-cis-retinol and 9-cis-retinol, whereas reduction was observed rather widely with many aldehydes. On the basis of these findings, we now call the reaction the aldehyde-alcohol redox-coupling reaction with the same abbreviation as before (AL-OL coupling reaction). Our results suggest that the postulated enzyme(s) catalyzing the AL-OL coupling has two distinct substrate-binding sites for aldehydes and retinols. We found that the enzyme(s) is a tightly membrane-associated protein(s) localized in the inner segment (most probably in the ellipsoid region) of a cone. On the basis of these results, we discuss the possible functional mechanisms of the reaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Cone Membranes

Carp (Cyprinus carpio) cones were purified as described (17). Animals were cared for according to institutional guidelines. Our purified cones retained the outer segment and the ellipsoid, but lacked the nucleus and the terminal region. We always counted the number of cone cells in a small portion of our purified cone preparation to estimate the total number of the cells in a sample used for each experiment, and in this study, the AL-OL coupling activity is expressed as units/cone cell. Cone membranes were prepared as follows. Purified cones were disrupted by freeze-thawing and washed three times with potassium gluconate buffer (115 mm potassium gluconate, 2.5 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EGTA, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 10 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5) by centrifugation at 104,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The washed membranes were stored at −80 °C until used.

For the substrate specificity and kinetic analyses, stored cone membranes were thawed, suspended in potassium gluconate buffer, and used. To study the membrane localization of the activity, freshly obtained purified cones were freeze-thawed and then washed once by centrifugation at 104,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C in potassium gluconate buffer. When necessary, the supernatant obtained in this centrifugation was collected. The membrane precipitates obtained were suspended in isotonic buffer (potassium gluconate buffer), hypotonic buffer (2 mm EDTA, 10 mm HEPES-KOH, and 1 mm dithiothreitol, pH 7.5), hypertonic buffer (600 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES-KOH, and 1 mm dithiothreitol, pH 7.5), or detergent buffer (0.48 mm dodecyl-β-d-maltoside and 10 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5). The membranes suspended in detergent buffer were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with rotation. For other membrane samples, this step was omitted. The membranes thus prepared were centrifuged at 104,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to obtain a soluble supernatant and a membrane precipitate fraction; these were used to determine in which fraction AL-OL coupling activity was present.

To study the subcellular localization of the activity, we prepared a cone outer segment membrane-rich fraction and a cone inner segment membrane-rich fraction3 by stepwise sucrose density gradient centrifugation, a method modified from the one reported previously (16). The collected membranes were suspended in potassium gluconate buffer. The total protein content in each fraction was quantified with Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining after SDS-PAGE using BSA as a standard, and cone visual pigment was quantified spectrophotometrically (18, 19). The purity of each fraction was judged based on the content of cone visual pigment per total proteins in each fraction.

Preparation of Retinoids and 9-cis-Retinol Analogs

All-trans-retinal and 9-cis-retinal were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and 3-dehydro-all-trans-retinal (A2 all-trans-retinal) was kindly provided by Prof. T. Seki (Osaka Kyoiku University) or purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. Other retinal isomers (11-cis-retinal and 13-cis-retinal) were prepared as described (20): ∼10 mg of all-trans-retinal was dissolved in 4 ml of acetonitrile at a final concentration of 10 mm and isomerized by irradiation with a fluorescent lamp (15 watts) at a distance of 10 cm for 1 day at 4 °C. After the solvent was evaporated under nitrogen, a mixture of retinal isomers was dissolved in 1 ml of a diethyl ether/n-hexane (15:85) solvent so that the concentration of total retinal isomers was ∼40 mm. The following manipulations were carried out under dim red light to prevent further isomerization. The mixture was then applied to a JASCO LC 800 HPLC system, and each isomer was separated with a preparative normal-phase column (Develosil 60-5, Nomura Chemical) using diethyl ether/n-hexane (15:85) as the mobile phase. Retinals in the eluate were detected by monitoring the absorbance at 350 nm, and the eluate corresponding to each peak on the chromatogram was collected in a test tube. To identify and quantify the retinal isomer, the absorption spectrum was measured and compared with data in the literature (21, 22). After purification, the solvent was evaporated under nitrogen, and each retinal isomer was dissolved in ethanol and stored at −80 °C until used.

Each retinol isomer was prepared by reduction of the corresponding retinal isomer (23). Approximately 6 mg of NaBH4 was added to a 100–300-μl ethanol solution containing a retinal isomer, and solution was incubated for 30–60 min on ice, and water was added to the sample to a final volume of 500 μl to partition NaBH4 in an aqueous phase. Retinols were extracted twice with 450 μl of solvent A (10:5:0.2:85 benzene/tert-butyl methyl ether/ethanol/n-hexane). After extraction, the solvent was evaporated under nitrogen, and each retinol isomer was dissolved in ethanol and stored at −80 °C until used.

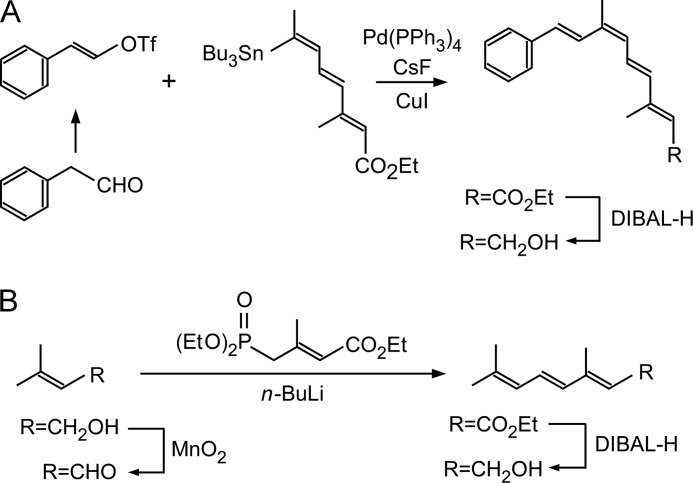

Analogs of 9-cis-retinol were prepared as follows. To obtain a tetraenol derivative (6Z-3,7-dimethyl-9-phenyl-2,4,6,8-nonatetraen-1-ol) (Fig. 1A), a mixture of the triflate (1.0 eq), obtained from the reaction of phenylacetaldehyde with N-phenyl-bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) (24), and tetraenylstannyl ester (1.3 eq) (25) was dissolved in dry dimethylformamide (4 ml), and CsF (2.0 eq), Pd(PPh3)4 (10 mol %), and CuI (20 mol %) were added. The flask was evacuated and refilled with argon five times. The mixture was stirred at 40–45 °C for 15 h, cooled to room temperature, quenched with water, and extracted with ether. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. The residue thus obtained was purified by column chromatography using neutralized SiO2/powdered KF (9:1) to give a coupling product. The coupled ester (1 eq) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (3 ml) and cooled to 0 °C. After diisobutylaluminium hydride (1 m solution in toluene, 2.2 eq) was added to the solution, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The resulting solution was quenched with aqueous silica gel (H2O/SiO2 = 1:4), stirred for 1 h, filtered through Celite (World Minerals), and dried over Na2SO4. After removal of the solvent, the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/ethyl acetate = 10:1) to give the alcohol.

FIGURE 1.

Scheme of the synthesis of 9-cis-retinol analogs. A, tetraenol derivative, 6Z-3,7-dimethyl-9-phenyl-2,4,6,8-nonatetraen-1-ol. B, trienol derivative, 3,7-dimethyl-2,4,6-octatrien-1-ol. DIBAL-H, diisobutylaluminium hydride. OTf, OSO2CF3 (O-trifluoromethanesulfonyl).

To synthesize a trienol derivative (3,7-dimethyl-2,4,6-octatrien-1-ol) (Fig. 1B), a mixture of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol (1 mmol) and MnO2 (25 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (20 ml) was stirred at room temperature for 6 h. After filtration through Celite, the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified using column chromatography on silica gel (ether/hexane = 1:4) to afford the aldehyde. A hexane solution of n-butyllithium (1.1 mmol) was added to a solution of triethyl 3-methyl-4-phosphonocrotonate (1.1 mmol) and N,N′-dimethyl propylene urea (3.5 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (5.5 ml) at 0 °C. After stirring for 30 min, the solution was cooled to −78 °C, and a solution of the aldehyde (1 mmol) obtained as described above and dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (3 ml) was added. The resulting mixture was stirred for an additional 2 h. The reaction was quenched with saturated NH4Cl, and the products were extracted with diethyl ether. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/AcOEt = 10:1), and the alcohol was obtained by reaction with diisobutylaluminium hydride.

Measurement of AL-OL Coupling Activity

The AL-OL coupling reaction was carried out under dim red light where pigment bleach was negligible. A cone membrane suspension (100 μl) obtained from 1–3 × 105 cones was transferred to a 5-ml glass vial. An alcohol substrate and an aldehyde/ketone substrate both dissolved in 0.5 μl of ethanol were added to the vial individually. In the case of ubiquinone, it was added as a 1,4-dioxane solution because it was difficult to dissolve it in ethanol. The sample was then incubated for 5–10 min at 25 °C. As a control, a sample containing cone membranes but devoid of one of the two substrates was incubated under similar conditions. The reaction was terminated by adding 300 μl of ice-chilled methanol. Retinal isomers in the sample were extracted in the form of oximes as described (26) with slight modifications: 100 μl of 1 m hydroxylamine, pH 7.5, was added, and the sample was incubated for 40 min at 25 °C. After incubation, retinoids (i.e. both retinal oximes and retinols) were extracted twice with 450 μl of solvent A. The solvent was then evaporated, and the extract was dissolved in 100 μl of solvent A. Each retinoid in the extract was separated by an analytical normal-phase column (Cosmosil 5SL-II, Nacalai Tesque) using the HPLC system and detected by monitoring the absorbance at 350 nm with solvent A as the mobile phase (26). Each retinoid was identified from its retention time by comparison with those of standard retinoids and quantified by comparing the peak area on the chromatogram with that of known amounts of each retinoid standard that had been quantified spectrophotometrically based on a reported extinction coefficient (27, 28). During incubation with cone membranes, retinoids are isomerized thermally (16). For this reason, the activity was determined by subtracting the amount of the isomer produced in a control measurement in which either aldehyde or alcohol was not added. Because an aldehyde and an alcohol are produced at a 1:1 ratio in the AL-OL coupling reaction, the activity was measured by the amount of one of the products, an aldehyde or an alcohol. For a practical reason to avoid the complexity of the quantification of the reaction product, in some of the measurements, we used a non-retinoid substrate, benzaldehyde. Whenever possible, we confirmed that the aldehyde and the alcohol were produced at a 1:1 ratio.

Kinetic Analysis of the AL-OL Coupling Reaction

The AL-OL coupling reaction is a two-substrate reaction, and typically, there are two types of reaction mechanisms in this type of reaction: a sequential reaction and a ping-pong reaction (29). To distinguish which was the case, the activity was measured by varying the concentrations of both substrates.

RESULTS

Evidence for a Redox Reaction

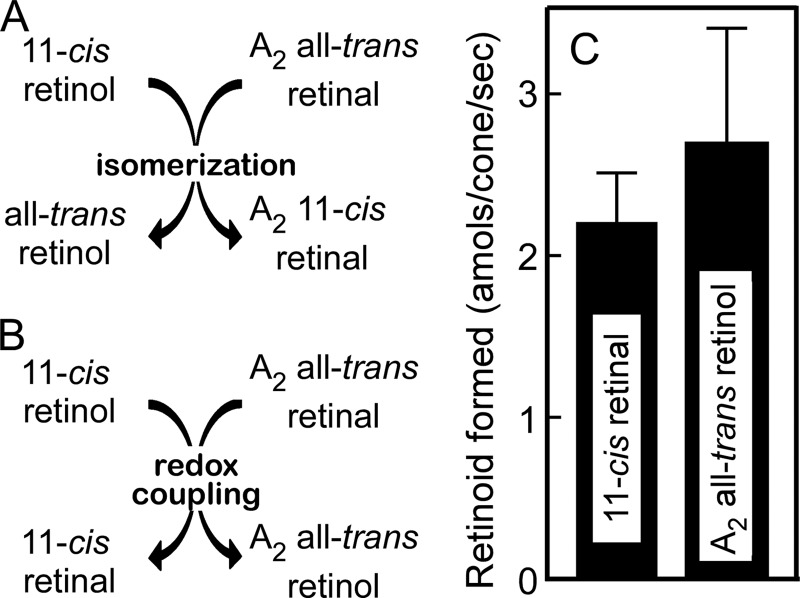

In our previous study (16), when 11-cis-retinol and all-trans-retinal were incubated with cone membranes, the corresponding aldehyde and alcohol, i.e. 11-cis-retinal and all-trans-retinol, were produced at a 1:1 ratio. Because this stoichiometry of the reaction could be easily explained by assuming that 11-cis-retinol was oxidized to 11-cis-retinal and that all-trans-retinal was reduced to all-trans-retinol concomitantly, we suggested that the reaction is a coupling of oxidation of an alcohol and reduction of an aldehyde. To confirm this idea and to exclude the possibility that the products were formed by isomerization, i.e. 11-cis-retinal was produced from all-trans-retinal, and all-trans-retinol was produced from 11-cis-retinol, we used 3-dehydro-all-trans-retinal (A2 all-trans-retinal) as the aldehyde and analyzed the reaction products. If 11-cis-retinal is produced from all-trans-retinal by isomerization, we should obtain A2 11-cis-retinal (Fig. 2A). Instead, if 11-cis-retinal is produced by oxidation of 11-cis-retinol, we should obtain A2 all-trans-retinol (Fig. 2B). Upon incubation of 11-cis-retinol and A2 all-trans-retinal, we obtained A2 all-trans-retinol (Fig. 2C). This result clearly shows that all-trans-retinol was formed by reduction of all-trans-retinal and that 11-cis-retinal was formed by oxidation of 11-cis-retinol (Fig. 2B). We therefore call this reaction the aldehyde-alcohol redox-coupling reaction (AL-OL coupling reaction; see below). In this reaction, 11-cis-retinal and A2 all-trans-retinol were produced at a 1:1 ratio (Fig. 2C), and the addition of enzyme cofactors was not necessary, in agreement with our previous study (16).

FIGURE 2.

Evidence for a redox reaction. There are potentially two possible mechanisms that account for the production of 11-cis-retinal: by isomerization (A) and by redox coupling (B). The products of the reaction in the presence of A2 all-trans-retinal and 11-cis-retinol were quantified (C). A2 all-trans-retinal was converted to its alcohol (n = 3).

Substrate Specificity of the AL-OL Coupling Reaction

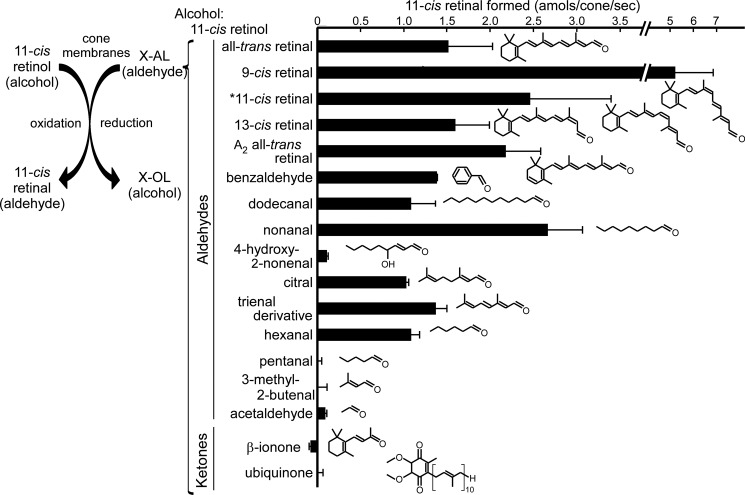

To understand the physiological role(s) of this reaction, it would be helpful to know the substrate specificity of this reaction. For the reduction of aldehydes, 11-cis-retinol was used as the alcohol substrate, and various aldehyde/ketone compounds, including retinal isomers, were examined at a concentration of 250 μm (Fig. 3). The activity was determined as the aldehyde/ketone-dependent formation of 11-cis-retinal (Fig. 3, left panel). As shown in Fig. 3, many aldehydes showed the activity: all-trans-retinal, 9-cis-retinal, 13-cis-retinal, A2 all-trans-retinal, benzaldehyde, medium-chain aldehydes (dodecanal, nonanal, and hexanal), citral, and a trienal derivative produced significant amounts of 11-cis-retinal. The activities detected were similar among the aldehydes examined, ranging from 1.03 ± 0.03 amol/cone/s with citral to 5.3 ± 1.6 amol/cone/s with 9-cis-retinal. In contrast, ketones (β-ionone and ubiquinone), pentanal, 3-methyl-2-butenal, and acetaldehyde were poor substrates at 250 μm. The compound 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is a lipid peroxidation product of polyunsaturated fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid and is produced in the retina in light (30). This aldehyde was not a good substrate either. It is noteworthy that some of the aldehydes (nonanal and hexanal) reported to be produced in mitochondria under oxidative stress (31) supported the reaction very effectively (Fig. 3). The activity was also measured and detected for 11-cis-retinal (Fig. 3, asterisk), and in this case, 9-cis-retinol instead of 11-cis-retinol was used as the alcohol (see below).

FIGURE 3.

AL-OL coupling activities for various aldehydes and ketones. Each substrate (250 μm) and 11-cis-retinol (250 μm) were incubated in the presence of cone membranes. The product (11-cis-retinal) was quantified, and the rate of its formation is shown by bars (mean ± S.D. (n > 3) or the range of variations (n = 2); n = 16 for all-trans-retinal, and n = 2–3 for the others). The structure of each substrate is shown. *, in the case of the measurement of 11-cis-retinal, 9-cis-retinol was used as the alcohol substrate, and the activity was determined as the formation of 11-cis-retinol.

In Fig. 3, pentanal and 3-methyl-2-butenal did not show activities at 250 μm. However, when the concentration was increased, they showed significant activities (0.44 ± 0.03 amol/cone/s with 1 mm pentanal and 0.43 ± 0.12 amol/cone/s with 2.5 mm 3-methyl-2-butenal; mean ± range of variations in two independent measurements). Acetaldehyde did not show significant activities even at 8.9 mm. These results therefore indicate that hydrophobic aldehydes are able to act as aldehyde substrates, although the affinity for the possible binding site seems to be dependent on the carbon chain length.

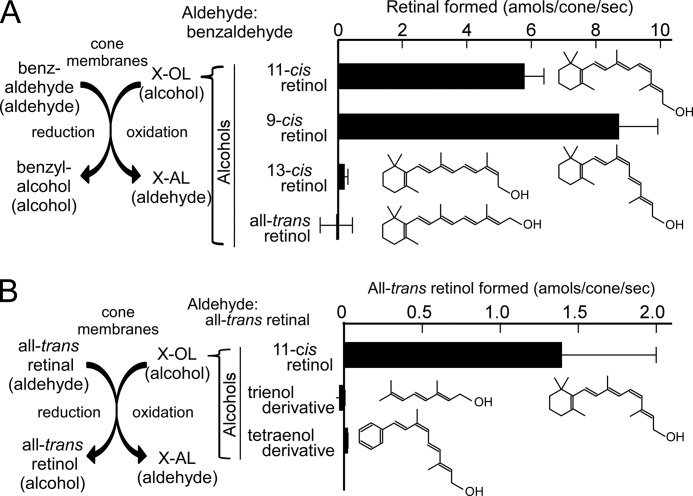

For the oxidation of alcohols, all-trans-, 9-cis-, 11-cis-, and 13-cis-retinols were first examined. As shown in Fig. 3, benzaldehyde can act as an aldehyde substrate. To avoid the complexity of quantification of the product among various cis- and trans-isomers produced during incubation, benzaldehyde was used as the common aldehyde for measurement of the oxidation of retinol isomers, and the oxidized product of each retinol was quantified (Fig. 4A, left panel). A retinol substrate (250 μm) and benzaldehyde (5 mm) were incubated in the presence of cone membranes. The results show that at 250 μm, only 11-cis-retinol and 9-cis-retinol supported the reaction, and all-trans-retinol and 13-cis-retinol were poor substrates (Fig. 4A). The activity was slightly higher for 9-cis-retinol (8.7 ± 1.2 amol/cone/s) compared with 11-cis-retinol (5.8 ± 0.6 amol/cone/s). To confirm that all-trans-retinol and 13-cis-retinol were poor substrates, the activities of these alcohols were measured at the higher concentration of 2.5 mm. No activity was observed for all-trans-retinol, whereas a low activity (1.2 ± 0.1 amol/cone/s, mean ± range of variations in two independent measurements) was observed for 13-cis-retinol at this concentration. It should be mentioned that, in general, the measured activity is dependent on the substrate and concentration used in the counterpart of the reaction. This is why the activities obtained in the presence of 11-cis-retinol and benzaldehyde were different in Fig. 3 (250 μm 11-cis-retinol and 250 μm benzaldehyde) and Fig. 4A (250 μm 11-cis-retinol and 5 mm benzaldehyde).

FIGURE 4.

AL-OL coupling activities for various alcohols. A, each retinol isomer (250 μm) and benzaldehyde (5 mm) were incubated in the presence of cone membranes. The aldehyde product of each isomer was quantified, and the rate of its formation is shown by bars. B, the activities of 9-cis-retinol analogs (250 μm) were measured in the presence of all-trans-retinal (250 μm), and one of the products (all-trans-retinol) was quantified. The rate of its formation is shown by bars. 11-cis-Retinol (250 μm) was used as a control. The structure of each alcohol is shown. In both A and B, the results are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n > 3) or the range of variations (n = 2).

For further analysis of alcohol specificity, 9-cis-retinol analogs (a trienol derivative and a tetraenol derivative) were examined at 250 μm (Fig. 4B). In this measurement, all-trans-retinal (250 μm) was used as the aldehyde substrate, and the all-trans-retinol formed was quantified as the product of the AL-OL coupling reaction (Fig. 4B, left panel). This way of quantification was necessary because the oxidized products of the trienol and tetraenol derivatives were difficult to quantify. Although the trienal derivative was a good aldehyde substrate (Fig. 3), its alcohol was a poor substrate (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the tetraenol derivative was not a good substrate (Fig. 4B). (The activity of the aldehyde of the tetraenol derivative was difficult to measure.) These results, together with the results shown in Fig. 4A, indicate that oxidation of the AL-OL coupling reaction is highly specific for 9-cis-retinol and 11-cis-retinol.

Reaction Mechanism of the AL-OL Coupling Reaction

The AL-OL coupling reaction is a two-substrate reaction that utilizes an alcohol substrate and an aldehyde substrate. To characterize the substrate-binding mechanism of AL-OL coupling, we performed a kinetic analysis. There are potentially two mechanisms that account for a two-substrate reaction. One is a sequential mechanism in which both substrates must bind to the enzyme before the products are formed and released. The other is a ping-pong mechanism in which one substrate first binds to the enzyme to form one product, followed by the second substrate binding to release the second product. These two mechanisms could be distinguished kinetically by measuring the enzyme activity at various concentrations of the first substrate at different fixed concentrations of the second substrate. When the relation between the substrate concentration and the enzyme activity is plotted double-reciprocally, the plots give a series of lines having a common intersection in the case of the sequential reaction and a series of parallel lines in the case of the ping-pong mechanism (29).

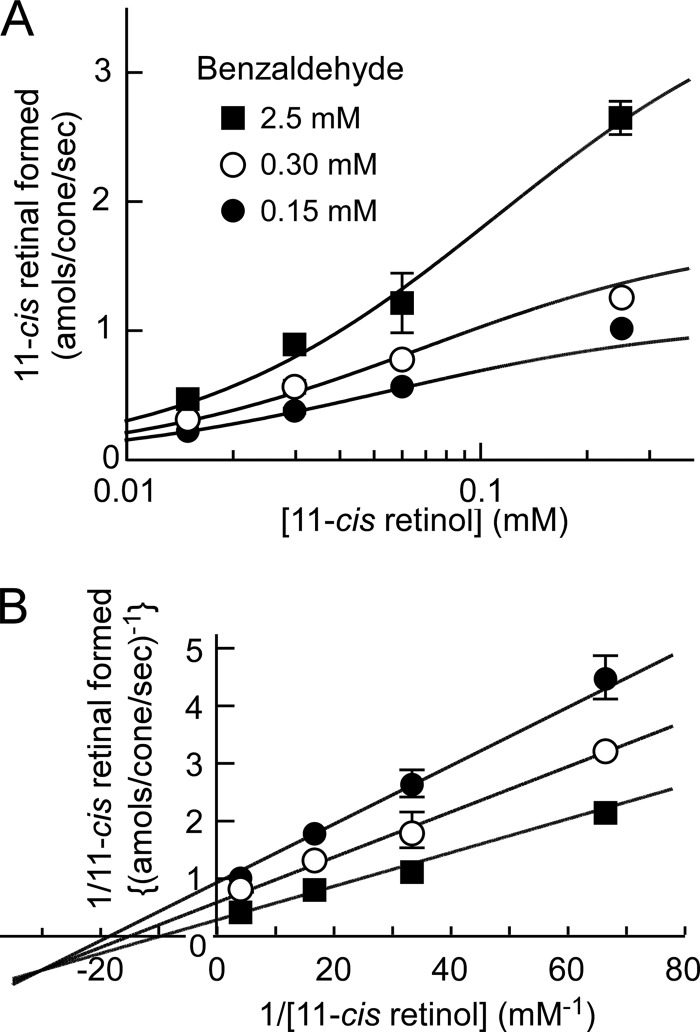

The AL-OL coupling activity was measured by varying both 11-cis-retinol and benzaldehyde concentrations. Fig. 5A shows the rate of the activity as a function of the concentration of 11-cis-retinol at three fixed benzaldehyde concentrations on a semilogarithmic scale. When the relation between the activity and the substrate concentration was plotted double-reciprocally, the lines seemingly had a common intersection and were not parallel. For this reason, the result was further analyzed on the basis of the sequential reaction.

FIGURE 5.

Kinetic analysis of the reaction mechanism. The AL-OL coupling reaction was performed in the presence of various concentrations of 11-cis-retinol and benzaldehyde, and the activity was measured as the formation of 11-cis-retinal. A, the activity was plotted semilogarithmically as a function of the concentration of 11-cis-retinol at three fixed benzaldehyde concentrations. All of the data were fitted to the equation formulated for the sequential reaction (solid lines; see “Results”). B, re-plot of A in a double-reciprocal plot. The data points are shown as the mean ± range of variations (n = 2).

The data in Fig. 5A were fitted to an equation formulated for the sequential reaction (29): v = (V1[A][B])/(KiAKmB +KmB[A] + KmA[B] + [A][B]), where v is the rate of the reaction; V1 is the maximum rate; [A] and [B] are the concentrations of substrates A and B (i.e. 11-cis-retinol and benzaldehyde, respectively); KiA is the binding constant of A for the free enzyme; and KmA and KmB are the Michaelis constants of A and B, respectively. The data fitted well to the equation with the following parameters: V1 = 4.5 amol of 11-cis-retinal formed per cone/s, KiA = 33 μm, KmA = 126 μm, and KmB = 469 μm (Fig. 5A, solid lines). The results are re-plotted double-reciprocally in Fig. 5B. Because the data fitted well to the equation for the sequential reaction, we concluded that the AL-OL coupling is a sequential reaction.

Localization of the AL-OL Coupling Activity in Cones

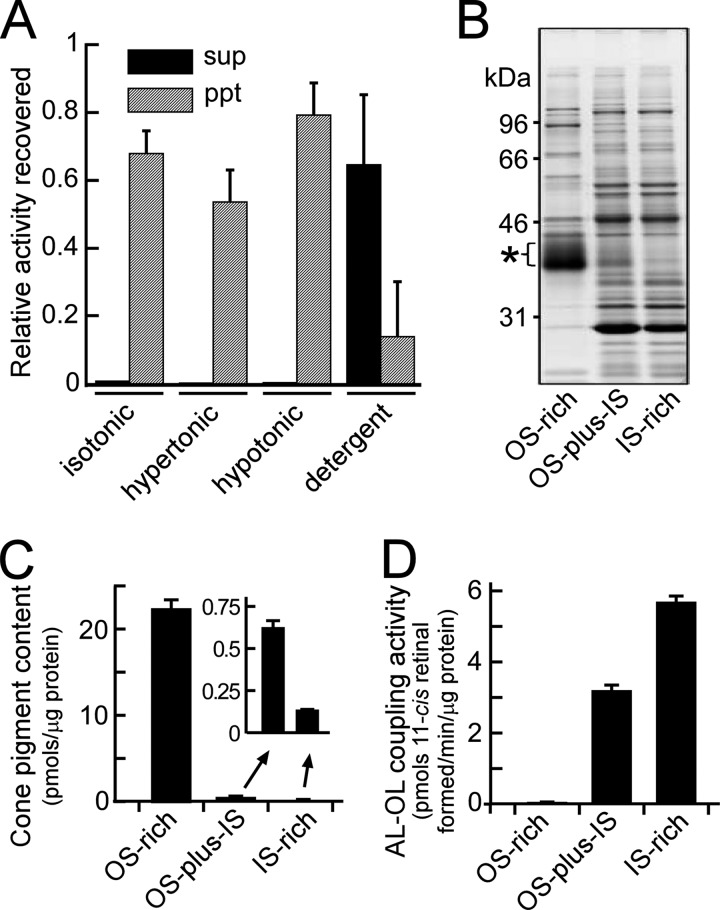

It would be also important to determine the localization of the AL-OL coupling reaction in a carp cone to understand the physiological role(s) of the reaction. First, we examined the membrane localization of the activity. For this purpose, freshly obtained purified carp cones were lysed by freeze-thawing and fractionated into a supernatant and a precipitate fraction by centrifugation. The activity was detected exclusively in the precipitate fraction (data not shown). For additional analyses, this precipitate was further resuspended in various kinds of buffers (isotonic, hypertonic, hypotonic, and detergent) and centrifuged to obtain supernatant and precipitate fractions. In all of the buffer solutions except the one containing a detergent, the activity was detected exclusively in the precipitate fraction (Fig. 6A). In the buffer containing a detergent, the activity was detected mostly in the supernatant fraction. These results indicate that the protein(s) responsible for the AL-OL coupling reaction is a tightly membrane-associated protein(s) in cone membranes.

FIGURE 6.

Localization of the AL-OL coupling activity in cones. A, cone membranes were washed by centrifugation with isotonic, hypertonic, or hypotonic buffer and buffer containing the detergent dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (0.48 mm). The activities of the AL-OL coupling reaction were determined in the supernatant and precipitate fractions after centrifugation. Each activity was normalized to that of the starting sample and is shown as the mean ± S.D. (n = 5 for the study in detergent buffer) or the range of variations (n = 2 for the others). B–D, SDS-PAGE pattern (B), cone pigment content (C), and AL-OL coupling activity (D) examined in the OS-rich and IS-rich preparations and in the starting purified cones (OS-plus-IS). For SDS-PAGE (B), each sample applied contained 2 μg of proteins. Cone pigment content (C) and AL-OL coupling activity (D) are expressed per unit amount of proteins and are shown as the mean ± range of variations (n = 2).

We then examined the subcellular localization of the activity. Purified carp cones were mechanically broken into the outer segment (OS) and the inner segment (IS). OS-rich and IS-rich fractions were obtained using a stepwise sucrose density gradient. Because the AL-OL coupling activity was tightly bound to membranes, soluble proteins lost during this OS-IS separation were ignored. The SDS-PAGE pattern of the total cone membranes containing both OS and IS membranes (Fig. 6B, OS-plus-IS) showed that, in this membrane preparation, visual pigment (Fig. 6B, asterisk) was a minor protein component and that other proteins (presumably those expressed in the cone IS) were the major proteins. This finding is consistent with our observation that the volume of the IS is much larger than that of the OS in carp cones (see, for example, Fig. 1A in Ref. 2). In the OS-rich fraction, cone visual pigment content was enriched by 36-fold compared with that in the starting cone membranes (Fig. 6, B and C, compare pigment contents in OS-rich and OS-plus-IS), whereas in the IS-rich fraction, most of the presumed IS proteins were retained, but the pigment content was reduced significantly (Fig. 6, B and C, compare pigment and other protein content in OS-plus-IS and IS-rich). When the activity of the AL-OL coupling reaction was measured, the activity was almost exclusively detected in the IS-rich fraction (Fig. 6D). Viewing our purified cone preparations under a light microscope showed that the majority of the cells were cone photoreceptors, and red blood cells were the only visible contaminants. The AL-OL coupling activity was not detected in purified red blood cells (data not shown). Likewise, the activity was not detected in the RPE (16). These results strongly suggest that the activity is present in the cone IS. Because our purified cones lacked the nucleus and terminal regions (18), the results shown in Fig. 6D indicate that the protein(s) responsible for the AL-OL coupling activity is probably localized in the ellipsoid region of a cone IS.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we first confirmed that 11-cis-retinal and all-trans-retinol formed in the presence of cone membranes are the products of oxidation of 11-cis-retinol and reduction of all-trans-retinal, respectively, and not those of isomerization (Fig. 2). On the basis of this result, we termed this reaction the aldehyde-alcohol redox-coupling reaction (AL-OL coupling reaction). We further examined the substrate specificity, substrate-binding mechanism, and subcellular localization of this reaction. Study of the substrate specificity demonstrated that reduction of aldehyde showed broad substrate specificity with a preference for aldehydes having a long carbon chain (Fig. 3), whereas alcohol oxidation was specific for 11-cis-retinol and 9-cis-retinol (Fig. 4). The binding of aldehyde and alcohol to the postulated enzyme could be explained by a sequential mechanism (Fig. 5). The AL-OL coupling activity was localized in the cone IS membranes, most probably in the cone ellipsoid membranes (Fig. 6). On the basis of these findings, we discuss below the possible structure of the binding site in the postulated enzyme and also possible functional mechanisms of the AL-OL coupling reaction.

Possible Structure of the Substrate-binding Site

The double-reciprocal plots of the relation between the substrate concentration and the AL-OL coupling activity show a common intersection (Fig. 5B). This demonstrates that the binding of an alcohol and an aldehyde to the enzyme is sequential. However, it was not possible in this analysis to determine whether one of the substrates should bind first or whether the binding order is random (29).

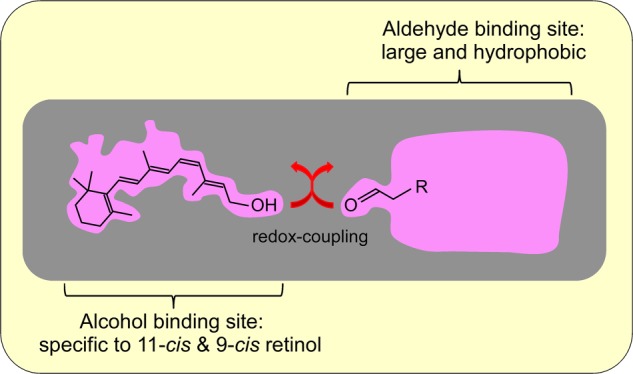

The binding of alcohols showed high specificity for 11-cis-retinol and 9-cis-retinol. In contrast, the binding of aldehydes showed broad specificity with preference for molecules containing a long carbon chain. This difference in substrate specificity between alcohols and aldehydes, together with the kinetic analysis showing sequential binding of the substrates, suggests that the binding site of alcohols is different from that of aldehydes. Because one substrate is oxidized and the other substrate is reduced, we speculate that the catalytic site of the redox reaction is probably present between the binding site of alcohols and that of aldehydes (Fig. 7). However, the mechanism through which the reaction proceeds requires further study.

FIGURE 7.

Model of the substrate-binding sites in a postulated enzyme(s) catalyzing the AL-OL coupling reaction.

The uniqueness of the AL-OL coupling reaction is that it oxidizes an alcohol and reduces an aldehyde at a 1:1 ratio without requiring exogenous cofactors. It is a beneficial reaction because high energy metabolites such as NADPH are not necessary. To our knowledge, this type of reaction is not known in vertebrates, but in bacteria, some alcohol dehydrogenases (e.g. nicotinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase) contain tightly bound NADH and catalyze the oxidation of an alcohol with the concomitant reduction of an aldehyde (32). The nicotinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase reaction obeys a ping-pong mechanism (32), whereas the AL-OL coupling reaction obeys a sequential reaction (Fig. 5). For this reason, the underlying mechanisms of these two reactions are not the same but could be similar in the sense that AL-OL coupling may utilize firmly bound cofactor. Actually, the addition of NADPH or NADP+ increased the AL-OL coupling activity under some conditions. This line of study is now in progress.

Possible Functional Mechanisms of the AL-OL Coupling Reaction

In our previous study (16), we postulated that, in the AL-OL coupling reaction, the physiologically relevant aldehyde and alcohol substrates are all-trans-retinal and 11-cis-retinol, respectively. The former is the product of pigment bleach, and the latter is the retinoid transported from Müller cells to cones. In fact, in the presence of total cone membranes, cone visual pigment was regenerated after bleaching the pigment when 11-cis-retinol was present during bleaching (16). This result suggested that AL-OL coupling utilized all-trans-retinal derived from the pigment as the aldehyde substrate to oxidize 11-cis-retinol. AL-OL coupling is advantageous in regenerating cone visual pigment for two reasons. First, the oxidizing activity of 11-cis-retinol was 50 times higher than that attained by retinol dehydrogenase activities (with NADP+) in cone membranes (16), and second, the reaction was specific to 11-cis-retinol and 9-cis-retinol (Fig. 4), both of which are effective in regenerating the pigment.

However, in this study, we found that the AL-OL coupling activity is present in the IS, most probably in the ellipsoid region of a cone. This finding raises a point that needs to be explained in our postulation: an aldehyde, all-trans-retinal, has to be transported to the IS, and an aldehyde, 11-cis-retinal produced from 11-cis-retinol, has to be transported to the OS. Because aldehydes are toxic, some cells contain CRALBP (cellular retinal-binding protein) to transport retinals within a cell. However, photoreceptors do not contain such proteins (33). Despite these facts, based on the results in previous studies, cones may be able to transport retinals within a cell.

In rods, when a large portion of pigment is bleached, the all-trans-retinal formed leaks from the OS to the IS (34). Although the cone OS contains a higher reduction activity for all-trans-retinal compared with the rod OS (16, 35, 36), the leakage of all-trans-retinal from the cone OS, if it is present, could be a route for the supply of the aldehyde for the AL-OL coupling reaction acting in the IS. Another potential source of aldehydes supporting the AL-OL coupling reaction could be the aldehydes produced in mitochondria in the ellipsoid region. As shown in Fig. 3, medium-chain aldehydes such as hexanal and nonanal effectively support the AL-OL coupling reaction. These aldehydes are produced in mitochondria under oxidative stress (31). If these aldehydes are produced under normal conditions, these aldehydes can act as the aldehyde substrate to support the AL-OL coupling reaction.

It has been suggested that cones have a specific pathway to transport 11-cis-retinal from the IS to the OS: when 11-cis-retinal was applied to the cell body of a salamander cone after bleaching the pigment, 11-cis-retinal was transported to the OS to regenerate visual pigments (37). A similar manipulation of the rods did not appreciably cause visual pigment regeneration. We suggest that, in this transport, cone opsin may play a similar role as CRALBP but in a different way. It has been shown that the chromophore of cone visual pigment, 11-cis-retinal, is replaced by exogenous 9-cis-retinal upon a simple incubation in a test tube (38). In a living cone cell, due to the low concentration of free 11-cis-retinal in the cell, 11-cis-retinal dissociates from the pigment, and ∼10% of the red cone opsin is free of 11-cis-retinal even in the dark (39). This less stable binding of the chromophore to opsin seems to be a general feature of a cone pigment (39) and could possibly be responsible for the transport of 11-cis-retinal from the IS to the OS: cone opsin may act as a relay station, and 11-cis-retinal is transported from one opsin to another, resulting in the net transport of 11-cis-retinal from the IS to the OS. Opsin is synthesized in the IS and transported continuously to the OS. So, if opsin acts as a relay station, the route of the 11-cis-retinal transport to the OS is always there. This hypothesis deserves further study. As an alternative mechanism, it is also possible that an unknown retinal-binding protein(s) is expressed in cones and acts as a transporter of aldehydes.

The AL-OL coupling activity is present specifically in the IS in carp cones, and the reaction is very effective in producing 11-cis-retinal from 11-cis-retinol. Obviously, further study is required to understand how this reaction contributes to retinoid metabolism in cones.

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants 20370060 and 23227002 (to S. K.) and 22770150 and 24570085 (to S. T.), a Human Frontier Science Program grant (to S. K.), and the Naito Foundation (to S. T.).

T. Fukagawa, S. Tachibanaki, and S. Kawamura, unpublished data.

- RPE

- retinal pigment epithelium

- AL-OL

- aldehyde-alcohol

- OS

- outer segment

- IS

- inner segment.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fu Y., Yau K. W. (2007) Phototransduction in mouse rods and cones. Pflugers Arch. 454, 805–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kawamura S., Tachibanaki S. (2008) Rod and cone photoreceptors: molecular basis of the difference in their physiology. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 150, 369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang J. S., Kefalov V. J. (2011) The cone-specific visual cycle. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 30, 115–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kiser P. D., Golczak M., Maeda A., Palczewski K. (2012) Key enzymes of the retinoid (visual) cycle in vertebrate retina. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 137–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saari J. C. (2012) Vitamin A metabolism in rod and cone visual cycles. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 32, 125–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tang P. H., Kono M., Koutalos Y., Ablonczy Z., Crouch R. K. (2013) New insights into retinoid metabolism and cycling within the retina. Prog. Retin. Eye. Res. 32, 48–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jin M., Li S., Moghrabi W. N., Sun H., Travis G. H. (2005) Rpe65 is the retinoid isomerase in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. Cell 122, 449–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moiseyev G., Chen Y., Takahashi Y., Wu B. X., Ma J. X. (2005) RPE65 is the isomerohydrolase in the retinoid visual cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12413–12418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Redmond T. M., Poliakov E., Yu S., Tsai J. Y., Lu Z., Gentleman S. (2005) Mutation of key residues of RPE65 abolishes its enzymatic role as isomerohydrolase in the visual cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13658–13663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Das S. R., Bhardwaj N., Kjeldbye H., Gouras P. (1992) Müller cells of chicken retina synthesize 11-cis-retinol. Biochem. J. 285, 907–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaylor J. J., Yuan Q., Cook J., Sarfare S., Makshanoff J., Miu A., Kim A., Kim P., Habib S., Roybal C. N., Xu T., Nusinowitz S., Travis G. H. (2013) Identification of DES1 as a vitamin A isomerase in Müller glial cells of the retina. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 30–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mata N. L., Radu R. A., Clemmons R. C., Travis G. H. (2002) Isomerization and oxidation of vitamin A in cone-dominant retinas: a novel pathway for visual-pigment regeneration in daylight. Neuron 36, 69–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kolesnikov A. V., Tang P. H., Parker R. O., Crouch R. K., Kefalov V. J. (2011) The mammalian cone visual cycle promotes rapid M/L-cone pigment regeneration independently of the interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein. J. Neurosci. 31, 7900–7909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones G. J., Crouch R. K., Wiggert B., Cornwall M. C., Chader G. J. (1989) Retinoid requirements for recovery of sensitivity after visual-pigment bleaching in isolated photoreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 9606–9610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ala-Laurila P., Cornwall M. C., Crouch R. K., Kono M. (2009) The action of 11-cis-retinol on cone opsins and intact cone photoreceptors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 16492–16500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyazono S., Shimauchi-Matsukawa Y., Tachibanaki S., Kawamura S. (2008) Highly efficient retinal metabolism in cones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16051–16056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tachibanaki S., Arinobu D., Shimauchi-Matsukawa Y., Tsushima S., Kawamura S. (2005) Highly effective phosphorylation by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 7 of light-activated visual pigment in cones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9329–9334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tachibanaki S., Tsushima S., Kawamura S. (2001) Low amplification and fast visual pigment phosphorylation as mechanisms characterizing cone photoresponses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14044–14049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okano T., Fukada Y., Artamonov I. D., Yoshizawa T. (1989) Purification of cone visual pigments from chicken retina. Biochemistry 28, 8848–8856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsumoto H., Nakamura Y., Tachibanaki S., Kawamura S., Hirayama M. (2003) Stimulatory effect of cyanidin 3-glycosides on the regeneration of rhodopsin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 3560–3563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zonta F., Stancher B. (1984) High-performance liquid chromatography of retinals, retinols (vitamin A1) and their dehydro homologues (vitamin A2): improvements in resolution and spectroscopic characterization of the stereoisomers. J. Chromatogr. 301, 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu R. S., Asato A. E. (1984) Photochemistry and synthesis of stereoisomers of vitamin A. Tetrahedron 40, 1931–1969 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suzuki T., Makino-Tasaka M. (1983) Analysis of retinal and 3-dehydroretinal in the retina by high-pressure liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 129, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wada A., Fukunaga K., Ito M., Mizuguchi Y., Nakagawa K., Okano T. (2004) Preparation and biological activity of 13-substituted retinoic acids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 12, 3931–3942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pazos Y., Iglesias B., de Lera A. R. (2001) The Suzuki coupling reaction in the stereocontrolled synthesis of 9-cis-retinoic acid and its ring-demethylated analogues. J. Org. Chem. 66, 8483–8489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Irie T., Seki T. (2002) Retinoid composition and retinal localization in the eggs of teleost fishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 131, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hubbard R., Brown P. K., Bownds D. (1971) Methodology of vitamin A and visual pigments. Methods Enzymol. 18, 615–653 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trehan A., Liu R. S., Shichida Y., Imamoto Y., Nakamura K., Yoshizawa T. (1990) On retention of chromophore configuration of rhodopsin isomers derived from three dicis retinal isomers. Bioorg. Chem. 18, 30–40 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bisswanger H. (2008) Multi-substrate reactions. in Enzyme Kinetics: Principles and Methods (Bisswanger H., ed), 2nd Ed., Section 2.6, pp. 124–134, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH &Co., Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tanito M., Elliott M. H., Kotake Y., Anderson R. E. (2005) Protein modifications by 4-hydroxynonenal and 4-hydroxyhexenal in light-exposed rat retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 3859–3868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reinheckel T., Noack H., Lorenz S., Wiswedel I., Augustin W. (1998) Comparison of protein oxidation and aldehyde formation during oxidative stress in isolated mitochondria. Free Radic. Res. 29, 297–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schenkels P., Duine J. A. (2000) Nicotinoprotein (NADH-containing) alcohol dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis DSM 1069: an efficient catalyst for coenzyme-independent oxidation of a broad spectrum of alcohols and the interconversion of alcohols and aldehydes. Microbiology 146, 775–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Collery R., McLoughlin S., Vendrell V., Finnegan J., Crabb J. W., Saari J. C., Kennedy B. N. (2008) Duplication and divergence of zebrafish CRALBP genes uncovers novel role for RPE- and Müller-CRALBP in cone vision. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 3812–3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen C., Thompson D. A., Koutalos Y. (2012) Reduction of all-trans-retinal in vertebrate rod photoreceptors requires the combined action of RDH8 and RDH12. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24662–24670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ala-Laurila P., Kolesnikov A. V., Crouch R. K., Tsina E., Shukolyukov S. A., Govardovskii V. I., Koutalos Y., Wiggert B., Estevez M. E., Cornwall M. C. (2006) Visual cycle: dependence of retinol production and removal on photoproduct decay and cell morphology. J. Gen. Physiol. 128, 153–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maeda A., Maeda T., Imanishi Y., Kuksa V., Alekseev A., Bronson J. D., Zhang H., Zhu L., Sun W., Saperstein D. A., Rieke F., Baehr W., Palczewski K. (2005) Role of photoreceptor-specific retinol dehydrogenase in the retinoid cycle in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18822–18832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jin J., Jones G. J., Cornwall M. C. (1994) Movement of retinal along cone and rod photoreceptors. Vis. Neurosci. 11, 389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matsumoto H., Yoshizawa T. (1975) Existence of a β-ionone ring-binding site in the rhodopsin molecule. Nature 258, 523–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kefalov V. J., Estevez M. E., Kono M., Goletz P. W., Crouch R. K., Cornwall M. C., Yau K. W. (2005) Breaking the covalent bond–a pigment property that contributes to desensitization in cones. Neuron 46, 879–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]