Abstract

PD 404182 [6H-6-imino-(2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyrimido)[1,2-c]-[1,3]benzothiazine], a heterocyclic iminobenzothiazine derivative, is a member of the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC) that is reported to possess antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. In this study, we used biochemical assays to screen LOPAC against human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase isoform 1 (DDAH1), an enzyme that physiologically metabolizes asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous and competitive inhibitor of nitric oxide (NO) synthase. We discovered that PD 404182 directly and dose-dependently inhibits DDAH. Moreover, PD 404182 significantly increased intracellular levels of ADMA in cultured primary human vascular endothelial cells (ECs) and reduced lipopolysaccharide-induced NO production in these cells, suggesting its therapeutic potential in septic shock–induced vascular collapse. In addition, PD 404182 abrogated the formation of tube-like structures by ECs in an in vitro angiogenesis assay, indicating its antiangiogenic potential in diseases characterized by pathologically excessive angiogenesis. Furthermore, we investigated the potential mechanism of inhibition of DDAH by this small molecule and found that PD 404182, which has striking structural similarity to ADMA, could be competed by a DDAH substrate, suggesting that it is a competitive inhibitor. Finally, our enzyme kinetics assay showed time-dependent inhibition, and our inhibitor dilution assay showed that the enzymatic activity of DDAH did not recover significantly after dilution, suggesting that PD 404182 might be a tightly bound, covalent, or an irreversible inhibitor of human DDAH1. This proposal is supported by mass spectrometry studies with PD 404182 and glutathione.

Introduction

We and others have applied high-throughput screening to discover small molecules that regulate the nitric oxide (NO) synthase (NOS)/dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) pathway (Hartzoulakis et al., 2007; Kotthaus et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Linsky and Fast, 2011, 2012; Linsky et al., 2011; Ghebremariam et al., 2012, 2013). This scientific interest stems from the essential biologic role that the NOS/DDAH pathway plays in metabolic, cardiovascular, pulmonary, immune, and nervous systems (Palm et al., 2007; Leiper and Nandi, 2011). The substrate l-arginine is converted to NO by the enzymatic activity of each of the three NOS isoforms, which are expressed in multiple cell types, including vascular endothelial cells (ECs), fibroblasts, macrophages, and lung epithelial cells. The first isoform, neuronal NOS (nNOS I), is constitutively expressed in the cytosol of neuronal cells and is physiologically involved in neurotransmission (Bryan et al., 2009). Overproduction of NO in the central nervous system has been implicated in tension-type and cluster headaches as well as migraine attacks (Lassen et al., 1998; Olesen, 2010). Type II NOS [inducible NOS (iNOS); NOS II] is an inducible isoform predominantly expressed in alveolar macrophages and other immune cells and plays a critical role in physiologic immune defense (Pechkovsky et al., 2002). The third isoform of NOS [endothelial NOS (eNOS); NOS III] is expressed in endothelial cells and is a major determinant of vascular tone, vascular growth, and interaction of the vessel wall with circulating blood elements (Dinerman et al., 1993).

The eNOS isoform produces small amounts of NO in a highly regulated manner. For example, the tractive force of fluid flow activates eNOS, leading to flow-mediated vasodilation that reduces endothelial shear stress (Cooke et al., 1991). In addition, physiologic concentrations of NO inhibit platelet and immune cell adherence to vessel walls and maintain quiescence of the underlying vascular smooth muscle (Cooke and Tsao, 1993). By contrast, iNOS is induced by cytokines and is not regulated by hemodynamic stimuli. Notably, the catalytic activity of iNOS is 1000-fold greater than eNOS. As a result, iNOS generally outstrips the local l-arginine supply. As a result, in addition to oxidizing l-arginine to NO, iNOS donates electrons to oxygen, generating superoxide anion, O2−. Because NO and O2− are highly reactive, they combine rapidly to form the peroxynitrite anion. This reactive molecule is useful in destroying pathogens. However, inappropriate activation of iNOS may be involved in peroxidation of lipids in cell membranes and nitration of tyrosines in signaling proteins, leading to impaired cell signaling, tissue injury, and further inflammation. In addition, peroxynitrite anion activates matrix metalloproteinases, which degrade collagen (Galis and Khatri, 2002). This activation of matrix metalloproteinases contributes to loss of normal tissue architecture, leading to pathologic conditions. Parenthetically, the nitrosative stress produced by iNOS activation may also induce endothelial dysfunction with impaired regulation of vascular tone as in septic shock (Julou-Schaeffer et al., 1990; Lorente et al., 1993; Landry and Oliver, 2001; Nandi et al., 2012). This could be in part due to uncoupling of eNOS (Münzel et al., 2005). The oxidative stress reduces levels of tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor that is necessary for proper eNOS dimerization and oxidation of l-arginine to NO. As a result, the uncoupled eNOS transfers electrons to oxygen, generating more superoxide anion, which promotes further inflammation and tissue injury.

The activity of each of the NOS isoforms is decreased by an endogenous inhibitor, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA). ADMA is derived from proteolysis of nuclear proteins containing methylated arginine residues; a chemically related endogenous inhibitor is monomethylarginine (MMA), but this is less common. Free ADMA (and MMA) molecules are largely degraded (∼80%) within the cell by DDAH (Palm et al., 2007) into citrulline and dimethylamine (monomethylamine the case of MMA). DDAH is widely expressed in mammalian cells in one of two isoforms (DDAH1 and DDAH2) (Palm et al., 2007). The activity of DDAH is reduced by oxidative stress that occurs in various cardiovascular disorders (Stühlinger et al., 2001; Palm et al., 2007). The reduced expression of DDAH causes an increase in circulating ADMA levels and consequent suppression of NOS activity. By contrast, DDAH is overly active in some diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (Pullamsetti et al., 2011; Janssen et al., 2013). Notably, DDAH expression has been reported to be induced by inflammatory cytokines (Ueda et al., 2003), which may explain its elevation in pulmonary fibrosis. Therefore, inhibition of DDAH activity using small molecules may increase local ADMA concentration and place a brake on the activity of iNOS.

In this study, our high-throughput screening for DDAH inhibitors revealed that the small molecule PD 404182 is a potent inhibitor of human DDAH1 activity and elevates cellular ADMA levels. In addition, PD 404182 reduced lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced elevation of NO. Moreover, PD 404182 abrogated angiogenic response of vascular ECs. We speculate that PD 404182 has therapeutic potential in diseases characterized by overproduction of NO.

Materials and Methods

High-Throughput Screening of DDAH Modulators.

The Stanford High Throughput Bioscience Center maintains a diverse collection of compounds gathered from various sources, including the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health. The Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds is a subset of this collection, which consists of about 1200 bioactive compounds obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (product LO1280; St. Louis, MO). We screened this library as part of a larger screen described recently (Ghebremariam et al., 2012). In brief, recombinant human DDAH1 was produced in a bacterial system, purified using affinity chromatography, and confirmed by Western blot and mass spectrometry. A biochemical assay was developed to monitor DDAH enzymatic activity by studying conversion of ADMA into l-citrulline and to identify small molecules that alter its activity (Ghebremariam et al., 2012). Initially, a single concentration screen was performed with the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds, and compounds that decreased DDAH activity by 30% or more compared with controls were confirmed using an 8-point dose response, as described (Ghebremariam et al., 2012). Hits were further validated using an orthogonal assay and freshly prepared compounds, as described below.

Validation of DDAH Inhibition by PD 404182.

The small molecules that consistently showed modulation of DDAH enzymatic activity in the colorimetric assay described above were cross-validated using a fluorimetric assay that uses a synthetic DDAH substrate, S-methyl-thiocitrulline (SMTC) (Linsky and Fast, 2011; Ghebremariam et al., 2012). The catabolism of SMTC produces methanethiol (CH3-SH), a product that can be quantified fluorimetrically upon reaction with a maleimido-coumarin–containing reagent (Ghebremariam et al., 2012). Comparison of fluorescence intensity with controls allowed the identification of small molecules that regulate DDAH enzymatic activity. Of the several inhibitors of DDAH activity, PD 404182 was identified as a novel and potent antagonist that inhibited DDAH activity in a dose-dependent fashion, as described below.

Cellular ADMA and NO Measurements.

To further confirm our in vitro finding and to validate the efficacy of PD 404182 as a viable DDAH antagonist, we performed cell culture studies of vascular endothelial cells to measure intracellular ADMA and NO levels, indicators of cellular DDAH activity. In brief, human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (female donor; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were cultured using standard techniques in cell culture flasks until ∼60% confluency. Next, the cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline, and fresh media were mixed with vehicle, PD 404182, or Nω-(2-methoxyethyl)-l-arginine (L-257) [a known and selective DDAH1 inhibitor (Leiper et al., 2007; Nandi et al., 2012) provided for this study by J. Leiper (Imperial College London, London, UK)] at a final compound concentration of 20 μM. The cells were cultured for 24 hours (with or without 100 ng/ml bacterial LPS), and the effect of the compounds on cellular ADMA and NO was studied in the cell lysate. The concentration of ADMA and NO was quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based biochemical assays following the recommendation of the suppliers (DLD Diagnostika, Hamburg, Germany, for ADMA and Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI, for NO).

In Vitro Angiogenesis Assay.

One of the characteristic features of ECs is their ability to form capillary-like tubes and cord-like structures, an in vitro model of angiogenesis, when seeded in Matrigel (Kiuchi et al., 2008). This ability of ECs to form tubes can be enhanced or inhibited by pharmacological agents that increase or decrease NO production, respectively. Accordingly, six-well plates were coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at 37°C for 45 minutes prior to seeding human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. The cells were treated with PD 404182 (50–100 μM), L-257 (50–100 μM), or vehicle and incubated at 37°C (5% CO2) for 18 hours to allow tube formation. The next day, the effect of the different pharmacological agents on tubulogenesis was assessed microscopically by scanning the wells. Representative images of each condition were captured from nonoverlapping fields. Meanwhile, a cell viability study was performed using the lactate dehydrogenase–release assay (Sigma-Aldrich) by incubating PD 404182 or L-257 with ECs at increasing compound concentration (10–300 μM each).

Enzymatic Activity Competition Assay.

To examine whether PD 404182 is an active-site competitive DDAH1 inhibitor, we assessed the effect of increased substrate concentration on the enzymatic reaction. First, we incubated DDAH (30 nM final concentration) with PD 404182 (10 μM final concentration) or vehicle [diluted dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)]. Next, various concentrations of SMTC (50 μM to 1 mM) were added to the wells (triplicate of each condition) to initiate the reaction. Fluorescence intensity, proportional to DDAH enzymatic activity, was monitored, and DDAH activity in the PD 404182–containing wells was calculated relative to the vehicle control wells.

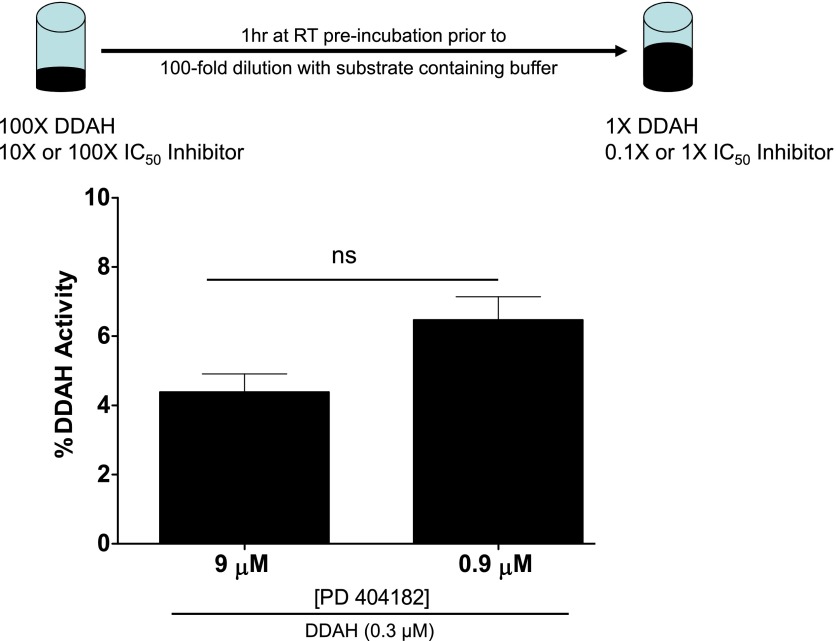

Reversibility Study.

To study whether DDAH1 inhibition by PD 404182 can be reversed, we performed a jump dilution assay, as described (Copeland et al., 2011). In brief, PD 404182 (at 10× or 100× its IC50 value) was preincubated with high concentration of DDAH (3 μM) for 1 hour at room temperature prior to a jump dilution by 100-fold with a solution containing the substrate SMTC. Subsequently, the recovery of DDAH enzymatic activity was evaluated by comparing data points for statistical significance.

Kinetic Characterization.

One of the classic properties of irreversible enzymatic inhibitors is the ability to progressively inhibit enzymatic activity over a period of time. To address whether PD 404182 shows this characteristic, we performed kinetic analyses by following inhibition of the conversion of SMTC into the product methanethiol in the presence of the compound (10 μM final concentration), vehicle or ebselen [a known irreversible DDAH1 inhibitor (Linsky et al., 2011)], over a period of several hours. The percent inhibition over time for PD 404182 and ebselen was calculated relative to the vehicle-treated wells and was expressed as mean ± S.E.M.

Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Study.

The interaction of PD 404182 with glutathione was examined by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. In brief, PD 404182 was dissolved in DMSO to make a 50 mM stock concentration. Next, the compound was reacted with glutathione in 50 mM sodium borate buffer, pH 7.7, by incubating for 2 hours at room temperature; both compounds were at 5 mM. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography- mass spectrometry on an Agilent 1260 HPLC equipped with an Agilent 6140 spectrometer. The column was a Synergi 4 μm Hydro-RP 80 Å 30 × 2.0 mm with initial conditions of 95% A (0.1% formic acid in water)/5% B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) held 0.3 minutes and then ramped to 100% B in 1.2 minutes at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. Ionization was in both positive and negative mode, with detection from 90 to 800 m/z. The column temperature was 40°C, and the injection volume was 1 μl. The UV wavelength was set to 254 nm. Experiments were also performed at pH 8.5 and 9.5, with similar results.

Results

PD 404182 Inhibits Human DDAH1 Enzymatic Activity.

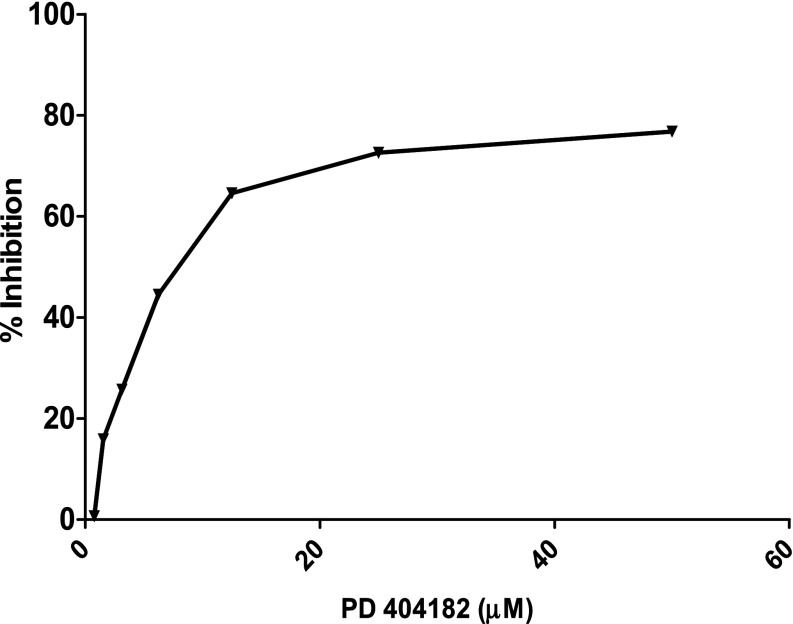

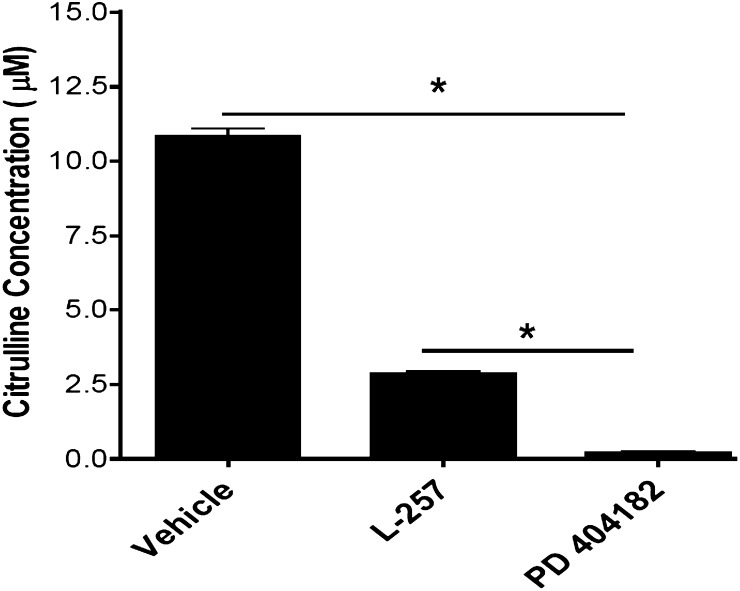

The enzymatic activity of human DDAH1 was significantly and dose-dependently inhibited by PD 404182 (Fig. 1), with an IC50 = 9 μM. Interestingly, PD 404182 possesses significantly higher in vitro potency than the substrate-like DDAH1 inhibitor L-257 [IC50 = 20 μM (Leiper et al., 2007)] in modulating DDAH enzymatic activity (Fig. 2), suggesting its feasibility as a probe to develop novel classes of inhibitors of human DDAH1.

Fig. 1.

Dose-dependent inhibition of DDAH activity by a novel small molecule, PD 404182. The biochemical conversion of the artificial substrate SMTC into methanethiol in the presence of PD 404182 is shown. The mean percent inhibition at 4 hours, in reference to vehicle control, from duplicate experiments is shown. The x-axis shows final compound concentration.

Fig. 2.

Validation of DDAH inhibition by PD 404182. In vitro production of L-citrulline from the endogenous substrate ADMA in the presence of vehicle (DMSO) control, PD 404182, or L-257 is shown. Compounds were used at 20 μM final concentration each. Data are mean ± S.E.M. from duplicate experiments (*P < 0.05).

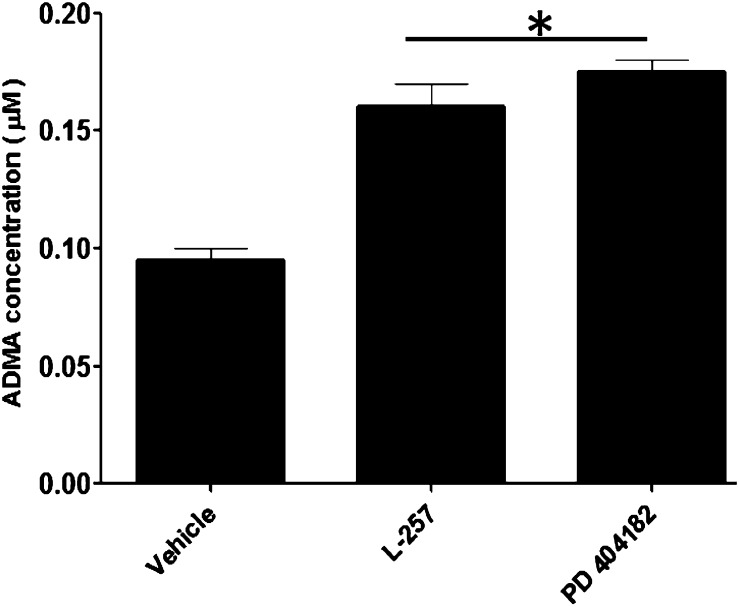

PD 404182 Increases Cellular ADMA Concentration.

The inhibition of DDAH enzymatic activity by PD 404182 in biochemical assays in vitro was corroborated by cell-based assays that quantify components of the DDAH/NOS pathway. In this study, PD 404182 caused significant elevation of the endogenous substrate ADMA in ECs incubated with the small molecule (Fig. 3). Treatment of ECs with PD 404182 resulted in an approximately 70% increase in cellular levels of ADMA compared with the 60% increase seen in the cells treated with L-257.

Fig. 3.

Intracellular inhibition of DDAH activity by PD 404182. Cellular ADMA concentration in vascular ECs following treatment with vehicle or the indicated small molecules at 20 μM each. Data are mean ± S.E.M. from duplicate experiments (*P < 0.05).

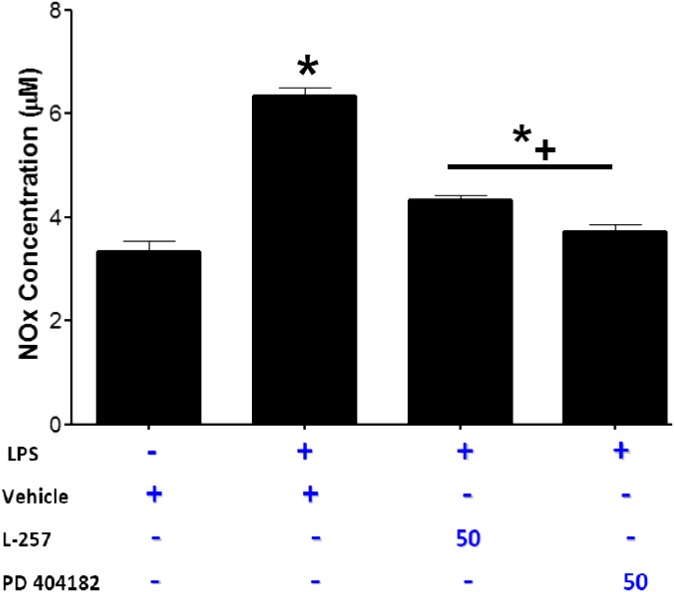

PD 404182 Reduces LPS-Induced NO Production.

One of the consequences of septic shock resulting from bacterial infection is uncontrolled increase in iNOS-derived vascular NO production resulting in pathologic decline in blood pressure. Because iNOS can be induced by bacterial LPS (Lowenstein et al., 1993), we studied the effect of PD 404182 on LPS-induced NO synthesis. In this study, LPS markedly increased NO production by the vascular ECs. Preincubation with PD 404182 significantly attenuated the increase in NO and nearly reversed NO concentrations to normal levels (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The effect of PD 404182 on NO production. Human vascular endothelial cells were treated with vehicle, PD 404182, or L-257 in the presence of LPS (100 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hours. Total nitrite (NOx) was measured using Griess reaction. Data are mean ± S.E.M. from duplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with non-LPS control. *+P < 0.05 compared with vehicle + LPS.

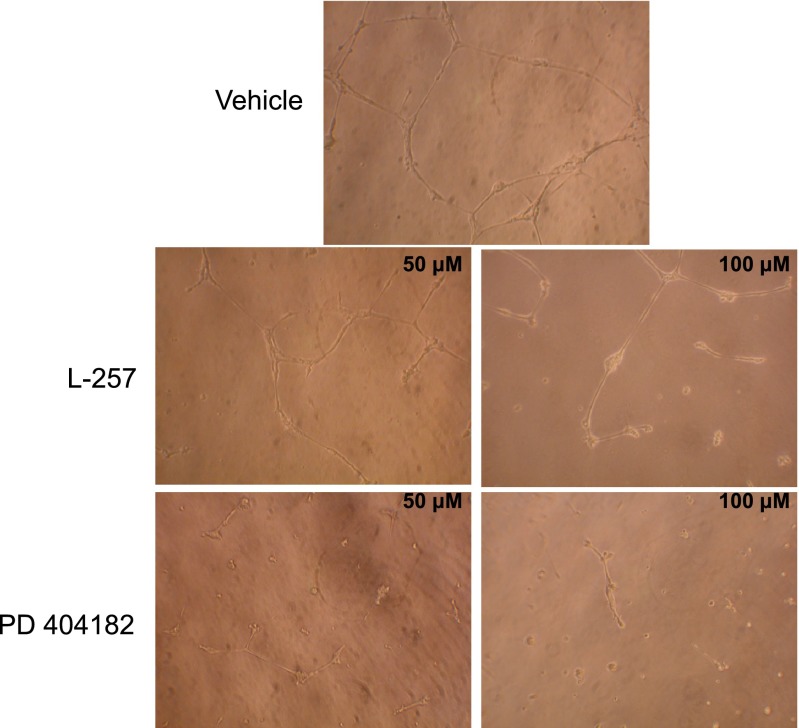

PD 404182 Inhibits In Vitro Angiogenesis.

NO plays a significant role in physiologic (as in wound healing) and pathologic (as in cancer metastasis) angiogenesis. Inhibitors of DDAH would limit NO production by elevating ADMA levels. In this study, we found that PD 404182 is a potent inhibitor of EC angiogenesis (Fig. 5). The compound concentration used in this study (50–100 μM) did not perturb cell membrane integrity (as demonstrated by lack of lactate dehydrogenase leakage into the conditioned media) (Supplemental Fig. 1) or induce cytotoxicity, as demonstrated by standard trypan blue staining, a finding that is validated by a previous report on several human cell lines (Chamoun et al., 2012). Interestingly, PD 404182 has been reported to inhibit EC sprouting in response to the potent proangiogenic protein vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Kalén et al., 2009), suggesting its therapeutic potential in pathologic angiogenesis. The antiangiogenic potency of PD 404182 is relatively modest compared with NOS inhibitors (Pfeiffer et al., 1996; Iwasaki et al., 1997; Takaoka et al., 2013) and other antiangiogenic agents, including inhibitors of tyrosine kinase, fibroblast growth factor, and its receptors, proteinases, prostaglandins, integrins, and adhesion molecules that have been tested in cancer malignancy and metastatic studies (Davis et al., 2008).

Fig. 5.

PD 404182 attenuated endothelial tube formation. Human microvascular endothelial cells were seeded on Matrigel and treated with vehicle, PD 404182, or L-257 for 18 hours, and formation of tube-like structures was visualized microscopically. Representative images are from duplicate experiments.

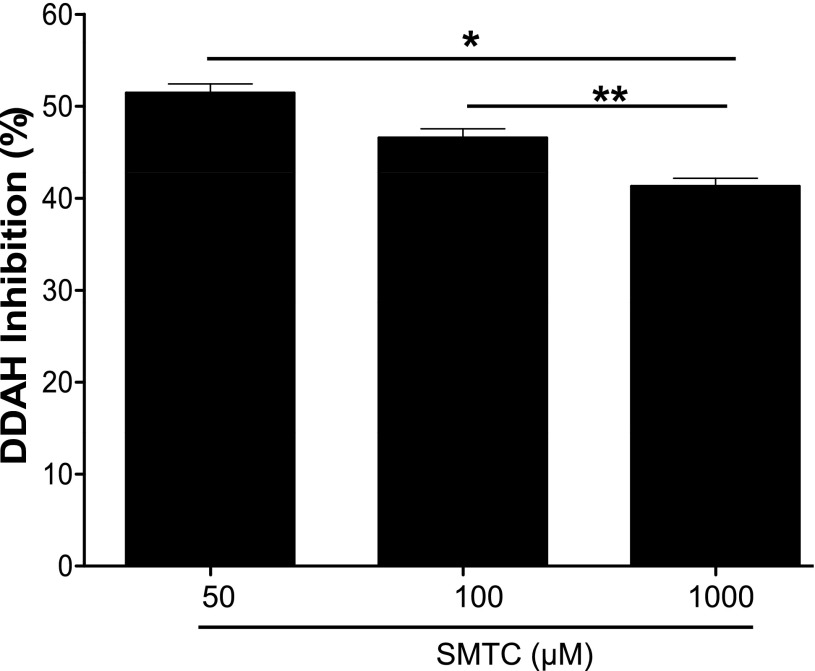

PD 404182 Is a Competitive DDAH Inhibitor.

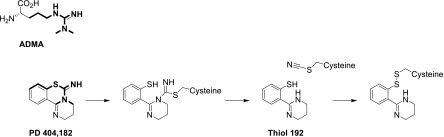

Our study of competition between DDAH substrate and PD 404182 for occupancy of the active site in DDAH revealed that the inhibitory action of PD 404182 can be significantly competed away by increasing the substrate concentration (Fig. 6), suggesting that PD 404182 inhibited DDAH activity, at least in part, by residing in the active site of the enzyme. This finding indicates that PD 404182 is a competitive inhibitor of human DDAH1. However, our attempt to reverse inhibition of DDAH activity by diluting away the inhibitor did not show significant recovery of enzymatic activity (Fig. 7), suggesting that PD 404182 might be an irreversible or slowly-dissociating inhibitor. These findings are consistent with the time-dependent inhibition of DDAH by PD 404182 (Supplemental Fig. 2). In addition, our electrospray ionization mass spectrometry study of PD 404182 with glutathione, a cysteine-containing compound, revealed the formation of new products. The observed masses of these products correspond to cyanylated glutathione and a disulfide-bonded adduct (Supplemental Fig. 3 and discussion below) (Degani and Patchornik, 1974). These results suggest that PD 404182 is inherently reactive to thiol groups such as the cysteine in the active site of DDAH1.

Fig. 6.

Competition assay. DDAH was incubated with PD 404182 (10 μM) or vehicle for 30 minutes, and various substrate (SMTC) concentrations were added to initiate the reaction. Fluorescence intensity was measured, and DDAH activity was calculated relative to vehicle controls. Data are mean ± S.E.M. from triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 versus 50 μM; **P < 0.05 between 100 and 1000 μM substrate concentration. The Michaelis constant (KM) for SMTC is ~ 3 μM (Wang et al., 2009).

Fig. 7.

Inhibitor dilution assay demonstrating low recovery of DDAH activity. PD 404182 (at 90 or 900 μM; IC50 is 9 μM) was preincubated with DDAH at high concentration and then serially diluted, as described above. The recovery of DDAH activity upon dilution of the inhibitor was evaluated. Data are mean ± S.E.M. from triplicate experiments. ns, not significant.

Discussion

Preclinical and clinical studies indicate an important role of the NOS/DDAH pathway in a number of acute and chronic cardiovascular, immune, neurologic, and pulmonary diseases. It is therefore logical to pharmacologically exploit this pathway for the management of such disorders. Inhibition of DDAH activity would be expected to increase endogenous ADMA, which would in turn inhibit iNOS and reduce nitrosative stress.

Recently, DDAH has been implicated in IPF. DDAH is upregulated in lung tissue from patients with IPF (Pullamsetti et al., 2011; Janssen et al., 2013) and would be expected to increase iNOS activity by reducing ADMA levels. The increased expression of DDAH would unleash iNOS, so as to generate toxic nitrosative radicals and increased lung injury (Genovese et al., 2005). Notably, bleomycin induces greater fibrosis and impairment of lung function in mice that overexpress DDAH (Pullamsetti et al., 2011). By contrast, inhibition of DDAH or iNOS ameliorates the lung injury induced by bleomycin (Pullamsetti et al., 2011). Other inflammatory diseases in which iNOS overactivity contributes to lung pathobiology include asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Batra et al., 2007; Seimetz et al., 2011).

In the present study, we identified a novel bioactive small molecule, PD 404182, that regulates ADMA and NO levels through inhibition of DDAH enzymatic activity. It appears that PD 404182 inhibits human DDAH1 activity competitively with substrate. Inhibitor dilution and time-dependent kinetic experiments show that PD 404182 is likely a competitive but slowly dissociating or irreversible inhibitor. Interestingly, the compound bears structural similarity with the endogenous substrate ADMA (Fig. 8), suggesting that it may interact covalently with the catalytic site of DDAH. The intriguing mechanism of PD 404182 interaction with sulfhydryl-containing compounds such as glutathione suggests that PD 404182 might transfer a cyano group to the sulfhydryl moiety on the protein. Protein cyanylation and cyanocysteine-mediated cyclization have been previously reported (Takenawa et al., 1998; Takahashi et al., 2007), although this was not known to be a characteristic of PD 404182. This mechanism may explain the low recovery of DDAH activity upon inhibitor dilution (Fig. 7). Crystallographic and protein mass-spectrometry studies will ultimately provide greater insight into this question.

Fig. 8.

Schematic of the structural resemblance of PD 404182 with the endogenous NOS inhibitor and DDAH substrate ADMA. The chemical similarities between the two are highlighted in bold. A putative reaction of PD 404182 with the active site cysteine (Cys273) of human DDAH-1 is also proposed. The active site cysteine first forms a covalent intermediate with PD 404182. This can fragment to release thiol 192 (a species with a molecular weight of 192), leaving the cysteine cyanylated. This could then form a mixed disulfide with thiol 192 or other thiols.

In addition to its inhibition of DDAH, PD 404182 has been reported to have antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antiangiogenic properties (Birck et al., 2000; Sansom, 2001; Kalén et al., 2009; Chamoun et al., 2012) as well as the ability to regulate mammalian circadian rhythms (Isojima et al., 2009). First discovered as an inhibitor of 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid 8-phosphate synthase (KDO 8-P synthase; in vitro inhibition constant, Ki, of less than 1 μM), an enzyme important for the synthesis of LPS and Gram-negative bacterial cell walls (Birck et al., 2000), PD 404182 has been considered as a candidate antibiotic against Gram-negative bacteria (Sansom, 2001). Recently, it was reported to have antiviral effects against human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus through an unknown mechanism (Chamoun et al., 2012). As a result of this promising polypharmacological potential, a number of facile synthetic methods for lead optimization have been proposed (Mizuhara et al., 2010, 2012a, 2012b, 2013).

In this study, we extend the pharmacological potential of PD 404182 by demonstrating its ability to directly regulate human DDAH1 enzymatic activity in biochemical and cell biological studies. It is intriguing that PD 404182 significantly reduced LPS-induced NO overproduction, as it also has antibacterial activity against LPS-containing Gram-negative bacteria (such as Escherichia coli). Such an agent could simultaneously oppose bacterial infection while reducing the adverse effect of LPS on blood pressure (Dellinger et al., 2008). In the United States alone, approximately 200,000 people die annually from sepsis-related complications, and sepsis costs over 16 billion dollars in direct and indirect medical expenses (Angus et al., 2001; Weycker et al., 2003; Jones, 2006).

Recently, Nandi et al. (2012) demonstrated the therapeutic potential of inhibiting DDAH1 to regulate blood pressure in a mouse model of endotoxic shock induced by LPS (Nandi et al., 2012). In their study, the selective DDAH1 inhibitor L-257 significantly prevented the drop in mean arterial blood pressure in response to LPS treatment. In our study of vascular ECs treated with LPS, PD 404182 was as effective as L-257 in suppressing the LPS-induced spike in NO (Fig. 4). Although our in vitro enzymatic assay study shows that PD 404182 (IC50 = 9 μM) is ~2-fold more potent against human DDAH1 than L-257 [IC50 = 20 μM (Leiper et al., 2007)], they possess similar potency in cell culture studies of ADMA and NO levels, perhaps due to the dynamic regulation of these endogenous molecules by a cascade of biochemical pathways, and/or due to cellular availability of these molecules (Meijer et al., 1990; Palm et al., 2007). However, because PD 404182 also possesses potent antibacterial activity (Birck et al., 2000; Sansom, 2001), in addition to reducing NO synthesis in response to LPS, it may be a better candidate for some forms of septic shock.

Our finding that PD 404182 has antiangiogenic effects is consistent with a previous report demonstrating inhibition of VEGF-induced sprouting of endothelial cells (Kalén et al., 2009). This property of PD 404182 might be useful in the development of drugs or as adjuvant therapy to reduce DDAH and/or NO-dependent cancer metastasis (Wink et al., 1998). NO is known to be involved in tumor progression and carcinogenesis, resulting in increased vascularity (angiogenesis) and spread of cancer (tumorigenesis) (Fukumura et al., 2006). In addition, glioma tumor cells that overexpress DDAH have been reported to show increased VEGF and NO production and present a more aggressive phenotype showing increased proliferation, vascularity, and tumor blood volume when implanted into animals (Kostourou et al., 2002, 2003). Furthermore, the DDAH/NOS machinery is upregulated in human prostate cancer (Vanella et al., 2011). However, any application of a DDAH antagonist must also take into account the physiologic importance of eNOS in the systemic vasculature. Thus, for most indications, it is likely that antagonists of DDAH would be administered with limitations in space and time (e.g., intermittent aerosolized administration to the lung). Nevertheless, given the lack of optimal therapies for several oncologic, cardiovascular, and pulmonary diseases, a novel therapeutic avenue is welcome, and antagonists of DDAH activity deserve further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. James Leiper (Imperial College London) for kindly providing L-257. They also thank Dr. David Solow-Cordero and Jason Wu of the Stanford High Throughput Bioscience Center for technical help during our high throughput screening effort and the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute for overall support.

Abbreviations

- ADMA

asymmetric dimethylarginine

- DDAH

dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- EC

endothelial cell

- iNOS

inducible nitric-oxide synthase

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- L-257

Nω-(2-methoxyethyl)-l-arginine

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MMA

monomethylarginine

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

NO synthase

- PD 404182

6H-6-imino-(2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyrimido)[1,2-c]-[1,3]benzothiazine

- SMTC

S-methyl-thiocitrulline

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Ghebremariam, Erlanson, Cooke.

Conducted experiments: Ghebremariam, Erlanson.

Performed data analysis: Ghebremariam, Erlanson, Cooke.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Ghebremariam, Erlanson, Cooke.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants 1U01HL100397 and K12HL087746] (to J.P.C.); the American Heart Association [Grant 11IRG5180026]; Stanford SPARK Translational Research Program (to Y.T.G.); the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant 1K01HL118683-01] (to Y.T.G.); and the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program of the University of California [Grant 18XT-0098]. Y.T.G. was a recipient of the Stanford School of Medicine Dean’s fellowship [Grant 1049528-149-KAVFB] and the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program of the University of California [Grant 20FT-0090].

Conflict of interest: Y.T.G. and J.P.C. are inventors on patents, owned by Stanford University, that protect the use of agents that modulate the NOS/DDAH pathway for therapeutic application. Ghebremariam YT and Cooke JP (2012) inventors; Stanford University, assignee. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase inhibitors and methods of use thereof. U.S. patent WO 2013123033A1. Application Pending.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 29:1303–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra J, Chatterjee R, Ghosh B. (2007) Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS): role in asthma pathogenesis. Indian J Biochem Biophys 44:303–309 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birck M, Holler T, Woodard R. (2000) Identification of a slow tight-binding inhibitor of 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid 8-phosphate synthase. J Am Chem Soc 122:9334–9335 [Google Scholar]

- Bryan NS, Bian K, Murad F. (2009) Discovery of the nitric oxide signaling pathway and targets for drug development. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 14:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoun AM, Chockalingam K, Bobardt M, Simeon R, Chang J, Gallay P, Chen Z. (2012) PD 404,182 is a virocidal small molecule that disrupts hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:672–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke JP, Rossitch E, Jr, Andon NA, Loscalzo J, Dzau VJ. (1991) Flow activates an endothelial potassium channel to release an endogenous nitrovasodilator. J Clin Invest 88:1663–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke JP, Tsao PS. (1993) Cytoprotective effects of nitric oxide. Circulation 88:2451–2454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland RA, Basavapathruni A, Moyer M, Scott MP. (2011) Impact of enzyme concentration and residence time on apparent activity recovery in jump dilution analysis. Anal Biochem 416:206–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DW, Herbst RS, Abbruzzese JL. (2008) Antiangiogenic Cancer Therapy, CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Degani Y, Patchornik A. (1974) Cyanylation of sulfhydryl groups by 2-nitro-5-thiocyanobenzoic acid: high-yield modification and cleavage of peptides at cysteine residues. Biochemistry 13:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R, et al. International Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. American College of Chest Physicians. American College of Emergency Physicians. Canadian Critical Care Society. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. European Respiratory Society. International Sepsis Forum. Japanese Association for Acute Medicine. Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Society of Critical Care Medicine. Society of Hospital Medicine. Surgical Infection Society. World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine (2008) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 36:296–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinerman JL, Lowenstein CJ, Snyder SH. (1993) Molecular mechanisms of nitric oxide regulation: potential relevance to cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 73:217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumura D, Kashiwagi S, Jain RK. (2006) The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 6:521–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galis ZS, Khatri JJ. (2002) Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling and atherogenesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Circ Res 90:251–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese T, Cuzzocrea S, Di Paola R, Failla M, Mazzon E, Sortino MA, Frasca G, Gili E, Crimi N, Caputi AP, et al. (2005) Inhibition or knock out of inducible nitric oxide synthase result in resistance to bleomycin-induced lung injury. Respir Res 6:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebremariam YT, Erlanson DA, Yamada K, Cooke JP. (2012) Development of a dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) assay for high-throughput chemical screening. J Biomol Screen 17:651–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebremariam YT, LePendu P, Lee JC, Erlanson DA, Slaviero A, Shah NH, Leiper J, Cooke JP. (2013) Unexpected effect of proton pump inhibitors: elevation of the cardiovascular risk factor asymmetric dimethylarginine. Circulation 128:845–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzoulakis B, Rossiter S, Gill H, O’Hara B, Steinke E, Gane PJ, Hurtado-Guerrero R, Leiper JM, Vallance P, Rust JM, et al. (2007) Discovery of inhibitors of the pentein superfamily protein dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH), by virtual screening and hit analysis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17:3953–3956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isojima Y, Nakajima M, Ukai H, Fujishima H, Yamada RG, Masumoto KH, Kiuchi R, Ishida M, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Minami Y, et al. (2009) CKIepsilon/delta-dependent phosphorylation is a temperature-insensitive, period-determining process in the mammalian circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:15744–15749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T, Higashiyama M, Kuriyama K, Sasaki A, Mukai M, Shinkai K, Horai T, Matsuda H, Akedo H. (1997) NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester inhibits bone metastasis after modified intracardiac injection of human breast cancer cells in a nude mouse model. Jpn J Cancer Res 88:861–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen W, Pullamsetti SS, Cooke J, Weissmann N, Guenther A, Schermuly RT. (2013) The role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in pulmonary fibrosis. J Pathol 229:242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AE. (2006) Evidence-based therapies for sepsis care in the emergency department: striking a balance between feasibility and necessity. Acad Emerg Med 13:82–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julou-Schaeffer G, Gray GA, Fleming I, Schott C, Parratt JR, Stoclet JC. (1990) Loss of vascular responsiveness induced by endotoxin involves L-arginine pathway. Am J Physiol 259:H1038–H1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalén M, Wallgard E, Asker N, Nasevicius A, Athley E, Billgren E, Larson JD, Wadman SA, Norseng E, Clark KJ, et al. (2009) Combination of reverse and chemical genetic screens reveals angiogenesis inhibitors and targets. Chem Biol 16:432–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi K, Matsuoka M, Wu JC, Lima e Silva R, Kengatharan M, Verghese M, Ueno S, Yokoi K, Khu NH, Cooke JP, et al. (2008) Mecamylamine suppresses Basal and nicotine-stimulated choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49:1705–1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostourou V, Robinson SP, Cartwright JE, Whitley GS. (2002) Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase I enhances tumour growth and angiogenesis. Br J Cancer 87:673–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostourou V, Robinson SP, Whitley GS, Griffiths JR. (2003) Effects of overexpression of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase on tumor angiogenesis assessed by susceptibility magnetic resonance imaging. Cancer Res 63:4960–4966 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotthaus J, Schade D, Muschick N, Beitz E, Clement B. (2008) Structure-activity relationship of novel and known inhibitors of human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase-1: alkenyl-amidines as new leads. Bioorg Med Chem 16:10205–10209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry DW, Oliver JA. (2001) The pathogenesis of vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med 345:588–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassen LH, Ashina M, Christiansen I, Ulrich V, Grover R, Donaldson J, Olesen J. (1998) Nitric oxide synthase inhibition: a new principle in the treatment of migraine attacks. Cephalalgia 18:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiper J, Nandi M. (2011) The therapeutic potential of targeting endogenous inhibitors of nitric oxide synthesis. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10:277–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiper J, Nandi M, Torondel B, Murray-Rust J, Malaki M, O’Hara B, Rossiter S, Anthony S, Madhani M, Selwood D, et al. (2007) Disruption of methylarginine metabolism impairs vascular homeostasis. Nat Med 13:198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsky T, Fast W. (2011) A continuous, fluorescent, high-throughput assay for human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase-1. J Biomol Screen 16:1089–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsky T, Wang Y, Fast W. (2011) Screening for dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase inhibitors reveals ebselen as a bioavailable inactivator. ACS Med Chem Lett 2:592–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsky TW, Fast W. (2012) Discovery of structurally-diverse inhibitor scaffolds by high-throughput screening of a fragment library with dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Bioorg Med Chem 20:5550–5558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente JA, Landín L, Renes E, De Pablo R, Jorge P, Ródena E, Liste D. (1993) Role of nitric oxide in the hemodynamic changes of sepsis. Crit Care Med 21:759–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein CJ, Alley EW, Raval P, Snowman AM, Snyder SH, Russell SW, Murphy WJ. (1993) Macrophage nitric oxide synthase gene: two upstream regions mediate induction by interferon gamma and lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:9730–9734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer AJ, Lamers WH, Chamuleau RA. (1990) Nitrogen metabolism and ornithine cycle function. Physiol Rev 70:701–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuhara T, Oishi S, Fujii N, Ohno H. (2010) Efficient synthesis of pyrimido[1,2-c] [1,3]benzothiazin-6-imines and related tricyclic heterocycles by S(N)Ar-type C-S, C-N, or C-O bond formation with heterocumulenes. J Org Chem 75:265–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuhara T, Oishi S, Ohno H, Shimura K, Matsuoka M, Fujii N. (2012a) Concise synthesis and anti-HIV activity of pyrimido[1,2-c][1,3]benzothiazin-6-imines and related tricyclic heterocycles. Org Biomol Chem 10:6792–6802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuhara T, Oishi S, Ohno H, Shimura K, Matsuoka M, Fujii N. (2012b) Structure-activity relationship study of pyrimido[1,2-c][1,3]benzothiazin-6-imine derivatives for potent anti-HIV agents. Bioorg Med Chem 20:6434–6441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuhara T, Oishi S, Ohno H, Shimura K, Matsuoka M, Fujii N. (2013) Design and synthesis of biotin- or alkyne-conjugated photoaffinity probes for studying the target molecules of PD 404182. Bioorg Med Chem 21:2079–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T, Daiber A, Ullrich V, Mülsch A. (2005) Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:1551–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi M, Kelly P, Torondel B, Wang Z, Starr A, Ma Y, Cunningham P, Stidwill R, Leiper J. (2012) Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 is protective in endotoxic shock. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32:2589–2597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen J. (2010) Nitric oxide-related drug targets in headache. Neurotherapeutics 7:183–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm F, Onozato ML, Luo Z, Wilcox CS. (2007) Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH): expression, regulation, and function in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293:H3227–H3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechkovsky DV, Zissel G, Stamme C, Goldmann T, Ari Jaffe H, Einhaus M, Taube C, Magnussen H, Schlaak M, Müller-Quernheim J. (2002) Human alveolar epithelial cells induce nitric oxide synthase-2 expression in alveolar macrophages. Eur Respir J 19:672–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer S, Leopold E, Schmidt K, Brunner F, Mayer B. (1996) Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis by NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME): requirement for bioactivation to the free acid, NG-nitro-L-arginine. Br J Pharmacol 118:1433–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullamsetti SS, Savai R, Dumitrascu R, Dahal BK, Wilhelm J, Konigshoff M, Zakrzewicz D, Ghofrani HA, Weissmann N, Eickelberg O, et al. (2011) The role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 3:87ra53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom C. (2001) LPS inhibitors: key to overcoming multidrug-resistant bacteria? Drug Discov Today 6:499–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimetz M, Parajuli N, Pichl A, Veit F, Kwapiszewska G, Weisel FC, Milger K, Egemnazarov B, Turowska A, Fuchs B, et al. (2011) Inducible NOS inhibition reverses tobacco-smoke-induced emphysema and pulmonary hypertension in mice. Cell 147:293–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stühlinger MC, Tsao PS, Her JH, Kimoto M, Balint RF, Cooke JP. (2001) Homocysteine impairs the nitric oxide synthase pathway: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine. Circulation 104:2569–2575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Arai M, Takenawa T, Sota H, Xie QH, Iwakura M. (2007) Stabilization of hyperactive dihydrofolate reductase by cyanocysteine-mediated backbone cyclization. J Biol Chem 282:9420–9429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka K, Hidaka S, Hashitani S, Segawa E, Yamamura M, Tanaka N, Zushi Y, Noguchi K, Kishimoto H, Urade M. (2013) Effect of a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor and a CXC chemokine receptor-4 antagonist on tumor growth and metastasis in a xenotransplanted mouse model of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the oral floor. Int J Oncol 43:737–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenawa T, Oda Y, Ishihama Y, Iwakura M. (1998) Cyanocysteine-mediated molecular dissection of dihydrofolate reductase: occurrence of intra- and inter-molecular reactions forming a peptide bond. J Biochem 123:1137–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda S, Kato S, Matsuoka H, Kimoto M, Okuda S, Morimatsu M, Imaizumi T. (2003) Regulation of cytokine-induced nitric oxide synthesis by asymmetric dimethylarginine: role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circ Res 92:226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanella L, Di Giacomo C, Acquaviva R, Santangelo R, Cardile V, Barbagallo I, Abraham NG, Sorrenti V. (2011) The DDAH/NOS pathway in human prostatic cancer cell lines: antiangiogenic effect of L-NAME. Int J Oncol 39:1303–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Monzingo AF, Hu S, Schaller TH, Robertus JD, Fast W. (2009) Developing dual and specific inhibitors of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase-1 and nitric oxide synthase: toward a targeted polypharmacology to control nitric oxide. Biochemistry 48:8624–8635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weycker D, Akhras KS, Edelsberg J, Angus DC, Oster G. (2003) Long-term mortality and medical care charges in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 31:2316–2323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink DA, Vodovotz Y, Laval J, Laval F, Dewhirst MW, Mitchell JB. (1998) The multifaceted roles of nitric oxide in cancer. Carcinogenesis 19:711–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.