Abstract

Interstitial adenosine stimulates neovascularization in part through A2B adenosine receptor-dependent upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that A2B receptors upregulate JunB, which can contribute to stimulation of VEGF production. Using the human microvascular endothelial cell line, human mast cell line, mouse cardiac Sca1-positive stromal cells, and mouse Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells, we found that adenosine receptor-dependent upregulation of VEGF production was associated with an increase in VEGF transcription, activator protein-1 (AP-1) activity, and JunB accumulation in all cells investigated. Furthermore, the expression of JunB, but not the expression of other genes encoding transcription factors from the Jun family, was specifically upregulated. In LLC cells expressing A2A and A2B receptor transcripts, only the nonselective adenosine agonist NECA (5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine), but not the selective A2A receptor agonist CGS21680 [2-p-(2-carboxyethyl) phenylethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine], significantly increased JunB reporter activity and JunB nuclear accumulation, which were inhibited by the A2B receptor antagonist PSB603 [(8-[4-[4-((4-chlorophenzyl)piperazide-1-sulfonyl)phenyl]]-1-propylxanthine]. Using activators and inhibitors of intracellular signaling, we demonstrated that A2B receptor-dependent accumulation of JunB protein and VEGF secretion share common intracellular pathways. NECA enhanced JunB binding to the murine VEGF promoter, whereas mutation of the high-affinity AP-1 site (−1093 to −1086) resulted in a loss of NECA-dependent VEGF reporter activity. Finally, NECA-dependent VEGF secretion and reporter activity were inhibited by the expression of a dominant negative JunB or by JunB knockdown. Thus, our data suggest an important role of the A2B receptor-dependent upregulation of JunB in VEGF production and possibly other AP-1–regulated events.

Introduction

The endogenous nucleoside adenosine is an intermediate product of adenine nucleotide metabolism. It is accumulated at sites of tissue injury, inflammation and local hypoxia. This results in increased local adenosine concentrations in the interstitium, where it exerts its actions via binding to extracellular G protein–coupled adenosine receptors, namely, A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 (Fredholm et al., 2001). Adenosine has long been known to stimulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production and angiogenesis (for reviews, see Adair, 2005; Feoktistov et al., 2009). In particular, we demonstrated that stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors upregulated VEGF secretion in various cell types, including cardiac mesenchymal stem-like cells (Ryzhov et al., 2012), retinal and skin endothelial cells (Grant et al., 1999, 2001; Feoktistov et al., 2002), certain types of cancer cells (Zeng et al., 2003; Ryzhov et al., 2008a), tumor-infiltrating hematopoietic cells (Ryzhov et al., 2008a), and mast cells (Feoktistov and Biaggioni, 1995; Feoktistov et al., 2003; Ryzhov et al., 2008b).

Although adenosine signaling through hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), a key transcription factor responsible for the tissue adaptation to ischemia, has been studied in detail (Merighi et al., 2005, 2006; De Ponti et al., 2007; Ramanathan et al., 2007, 2009; Alchera et al., 2008; Gessi et al., 2010), the role of other transcription factors in the adenosine-dependent VEGF production is not known. In addition to HIF-1, several transcription factor-binding sites for activator protein-1 (AP-1), AP-2, early growth response-1, specificity protein 1/3, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 have been identified within a 1.2 kb region of both mouse and human VEGF promoters (for review, see Pages and Pouyssegur, 2005). The AP-1 transcription factor family is composed of proteins belonging to the Jun (c-Jun, JunB, and JunD) subfamily proteins that can bind to AP-1 consensus sites either in their homodimeric forms or upon forming heterodimeric complexes with members of the Fos or the ATF subfamilies of AP-1 proteins (for review, see Karin et al., 1997).

There is growing evidence suggesting an important nonredundant role of JunB in the regulation of VEGF production and angiogenesis. When the different Jun members were deleted in mice, only the loss of JunB affected vascular development (Schorpp-Kistner et al., 1999). More recent studies have demonstrated that JunB can bind directly to an AP-1 consensus sequence within a 1.2 kb region of the mouse VEGF promoter and upregulate VEGF production in response to hypoxia or hypoglycemia independently of HIF-1 signaling (Textor et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2007). It is not known, however, whether JunB is involved in the adenosine-dependent regulation of VEGF production. To the best of our knowledge, the effects of adenosine on members of Jun subfamily of AP-1 proteins, including JunB, have not been reported yet. In our current study, we tested the hypothesis that A2B adenosine receptors upregulate JunB, which can contribute to stimulation of VEGF production and possibly many other AP-1–dependent events.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

PSB603 (8-[4-[4-((4-chlorophenzyl)piperazide-1-sulfonyl)phenyl]]-1-propylxanthine) was from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). NECA (5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine) and CGS 21680 [2-p-(2-carboxyethyl) phenylethylamino-NECA] were purchased from Research Biochemicals, Inc. (Natick, MA). PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate), forskolin, and Rp-cAMPS (Rp-adenosine 2′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). H-89 (N-[2-((p-bromocinnamyl)amino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide, dihydrochloride), U73122 [1-(6-{[17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5-(10)triene-17-yl]amino}hexyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione], U73343 [1-(6-{[17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5-(10)triene-17-yl]amino}hexyl)-2,5-pyrrolidine-dione], U0126 (1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio)butadiene), U0124, (1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(methylthio)butadiene), and Gö6983 (3-[1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-5-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl]-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Cell culture media were purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Mouse basic fibroblast growth factor was obtained from ProSpec-Tany Technogene, Ltd. (East Brunswick, NJ). Mouse interferon-γ was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), nonessential amino acids, antibiotic-antimycotic solution, α-thioglycerol, and dimethyl sulfoxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. When used as a solvent, final dimethyl sulfoxide concentrations in all assays did not exceed 0.1%, and the same dimethyl sulfoxide concentrations were used in vehicle controls.

Cell Culture.

Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1), obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Infectious Diseases (Atlanta, GA), were grown in 199 medium containing 15% FBS and supplemented with 30 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The human mast cell line (HMC-1) was a gift from Dr. Joseph H. Butterfield (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). HMC-1 cells were maintained in suspension culture at a density between 3 and 6 × 105 cells/ml by dilution with Iscove’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, and 1.2 mM α-thioglycerol. Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells (CRL-1642) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in 10% FBS Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) and maintained in DMEM–high glucose supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM glutamine. Mouse cardiac Sca-1+CD31− stromal cells (mCSC) were isolated as previously described elsewhere (Ryzhov et al., 2012). Cells were propagated on 0.1% gelatin-coated tissue culture dishes in DMEM–high glucose supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor, and 10 ng/ml interferon-γ at 33°C. Three days before the experiments, the cells were replated and cultured in the absence of interferon-γ at 37°C.

Real-Time Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction.

Total RNA was isolated from cells using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). One microgram of total DNase-treated RNA was used to generate cDNA with MMLV RT (Promega, Madison, WI) and random hexamers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed using the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems), as described previously elsewhere (Ryzhov et al., 2012). Primer pairs for human and murine adenosine receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, A3) were obtained from Applied Biosystems (human AdoRs: Hs00181231, Hs00169123, Hs00386497, and Hs00181232; and murine AdoRs: Mm01308023, Mm00802075, Mm00839292, and Mm00802076). Primer sequences for human and mouse JunB, JunD, c-Jun, and β-actin are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers for reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction used in this study

| Target | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse | ||

| JunB | TAAAGAGGAACCGCAGACCGTA | AGTGTCTTCACCTTGTCCTCCA |

| JunD | AGTTGGACTCCACACATCCCAT | TGTCAGTTTCACAGGGTGGAGT |

| c-Jun | GGTGGCACAGCTTAAGCAGAAA | TCTCTGTCGCAACCAGTCAAGT |

| β-Actin | AGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGTA | GCCAGAGCAGTAATCTCCTTCT |

| Human | ||

| JunB | TGGAACAGCCCTTCTACCAC | GGTTTCAGGAGTTTGTAGTC |

| JunD | GCCTCATCATCCAGTCCAAC | CCACCTTGGGGTAGAGGAAC |

| c-Jun | TGACTGCAAAGATGGAAACG | CAGGGTCATGCTCTGTTTCA |

| β-Actin | CGCCCCAGGCACCAGGGC | GGCTGGGGTGTTGAAGGT |

Western Blot Analysis.

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Total protein concentrations were quantified with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of protein (30–60 μg/well) were resolved in NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel in the presence 1× MES buffer (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid; Invitrogen) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane Immobilon-FL (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents, Temecula, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-JunB (sc-73), anti–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (anti-ERK) (sc-154), goat polyclonal phospho-ERK antibody (sc-7976), and mouse monoclonal anti–β-actin (sc-69879) were used at 1:750, 1:500, 1:200, and 1:1000 dilutions, respectively (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Anti–β-tubulin (DM1B) antibody (Millipore) was used at a concentration of 0.2 μg/ml (1:5000 dilution). After treatment with an appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, the bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence method (Nesbitt and Horton, 1992). The intensity of protein bands was quantified by a densitometer using ImageJ 1.45s software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). In some experiments, secondary anti-mouse IRDye@800CW (1:8000) and anti-rabbit IRDye@680LT (1:20,000) antibodies (Li-Cor Bioscience, Lincoln, NE) were used. The blots were scanned with LICOR Odyssey Infrared imager (Li-Cor Bioscience) to visualize the fluorescent immunocomplexes.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

LLC cells were seeded into glass eight-chamber slides and grown to 90–95% confluency. Cells were incubated in the presence of the reagents indicated in Results for 6 hours and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were incubated with rabbit anti-JunB (sc-73; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody overnight at 4°C, washed, and incubated with AlexaFluor 488–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) at 1:1000 dilution for 2 hours. The slides were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade reagent with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Invitrogen). Images were acquired with Olympus FV-1000 inverted confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using a 100×/1.40 SPlan-UApo oil immersion objective and excitation/emission wavelengths of 405 and 488, and processed using F10-ASW 1.6 Viewer. The corrected total cell fluorescence values were calculated as Integrated density − (Area of selected cell × Mean fluorescence of background readings) using ImageJ 1.45s software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay.

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed using the SimpleChIP Enzymatic Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, LLC cells (2 × 107 per immunoprecipitation) were cross-linked using formaldehyde. Cell nuclei were isolated after sonication (7 times with 20-second pulses on ice) using a Sonic Dismembrator 300 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of chromatin were immunoprecipitated with JunB antibody (sc-73; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Rabbit IgG was used as negative control. After reversal of crosslinks and DNA purification, the PCR amplification was performed using Mastercycler gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Forward primer 5′-AGCTGGCCTACCTACCTTTCTGA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CTTATCTGAGCCCTTGTCTG-3′ were used for amplification of the VEGF gene promoter region from −1140 to −733 harboring the putative AP-1 site (Schmidt et al., 2007), employing the following conditions: 94°C for 4 minutes; 30–35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 58.5°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds; and final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. The PCR products were analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Constructs and Luciferase Reporter Assays.

To construct mouse JunB promoter-driven luciferase reporter, mouse genomic DNA was isolated using DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen). The JunB genomic DNA, comprising 5′ flanking −870 to +133 base pairs of the murine JunB gene, was generated using PCR. MluI and XhoI restriction sites were introduced into forward 5′-GAGGTACAGCCTCACGCGTACAA-3′ and reverse 5′-AGTTGGCTCGAGTGCGTAAAGGC-3′ primers. After digestion with MluI and XhoI, the 1.0-kb PCR fragment was ligated upstream of a promoterless luciferase gene into the KpnI–XhoI sites of pGL2-basic vector (Promega). The sequence was verified against published database-accessible sequences. The pAP1-luc reporter was purchased from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA).

Mouse VEGF promoter-driven luciferase reporter, which encompasses 1.2 kb of the 5′-flanking sequence, the transcription start site, and 0.4-kb of corresponding 5′-UTR (Shima et al., 1996) was kindly provided by Dr. Patricia A. D’Amore (Harvard University, Boston MA). Mouse VEGF luciferase reporter with the putative AP-1 site at position −1093 to −1086 mutated from TGAATCA to AGGTTCC (Schmidt et al., 2007) was kindly provided by Dr. Marina Schorpp-Kistner (DKFZ-German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany). Human VEGF promoter-driven luciferase reporter VEGF-P7 (Forsythe et al., 1996) was kindly provided by Dr. Greg L. Semenza (Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD). Dominant negative JunB mutant construct pcDNA3-JunBΔN (Ikebe et al., 2007), was a kind gift from Dr. Mitsuyasu Kato (University of Tsukuba, Japan).

Cells were grown to 50% confluency and transfected with 1 μg/well of plasmid DNA using FugeneHD reagent (Roche). To test the effect of dominant negative JunB mutant on VEGF reporter activity, pcDNA3-JunBΔN, pVEGF-luc, and pRL-SV40 vectors were cotransfected at ratio 80:20:1. Twenty-four hours after transfections, cells were incubated in the presence of the reagents indicated in Results for an additional 6 hours. Reporter activity was measured using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Firefly luciferase reporter activities were normalized against Renilla luciferase activities from the coexpressed pRL-SV40 and expressed as relative luciferase activities over the basal level.

Stable Transfection of Dominant Negative JunB Mutant in LLC Cells.

LLC cells were transfected with pcDNA3-JunBΔN or empty pcDNA3 plasmid. After 24 hours, the growth medium was replaced with a fresh medium containing 0.8 mg/ml G-418. One week later, the colonies of LLCs that survived after G-418 treatment were selected, and the expression of dominant negative JunB mutant was verified by Western immunoblotting using rabbit polyclonal anti-JunB (sc-73; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Production and Stable Transduction of Lentiviral Vectors Encoding Short Hairpin RNA in LLC Cells.

MISSION pLKO.1-puro JunB short hairpin RNAs (shRNA1) (TRCN0000232241), shRNA2 (TRCN0000232242), shRNA3 (TRCN0000054488), shRNA4 (TRCN0000042698), shRNA5 (TRCN0000042699), empty vector (SHC001), and nontargeting control nonmammalian shRNA (SHC002) plasmids were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Lentiviral psPAX.2 packaging (cat. no. 12260) and pMD2.G (cat. no. 12259) envelope plasmids were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge MA). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cotransfected with MISSION pLKO.1-puro, psPAX.2, and pMD2.G plasmid constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus-containing supernatants were harvested 48 hours later and frozen at −80°C.

For infection, LLC cells (2 × 105 per well) were seeded on six-well plates and 12 hours later were incubated with lentiviral particles diluted 1:1000 in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for an additional 12 hours. After 36 hours’ recovery, stably transduced LLC cells were selected by culturing in the presence of 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Evaluation of Ras-Proximate-1 Activation.

After overnight serum starvation, HMEC-1 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 10 μM U73122 for 30 minutes followed by incubation in the presence of 10 μM NECA for 5, 10, or 15 minutes. Ras-proximate-1 (Rap1) activation was determined after pull-down of Rap1-GTP with GST-RalGDS-Rap1 binding domain using the Active Rap1 Pull-Down and Detection Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the supplier’s instructions.

Analysis of VEGF Secretion.

The VEGF protein level in culture media was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (R&D Systems).

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Comparisons between several treatment groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by appropriate post hoc tests. Comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tailed unpaired t tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

JunB Accumulation and Increase in AP-1 Activity Are Associated with Adenosine-Dependent Upregulation of VEGF Production in Different Human and Mouse Cell Types.

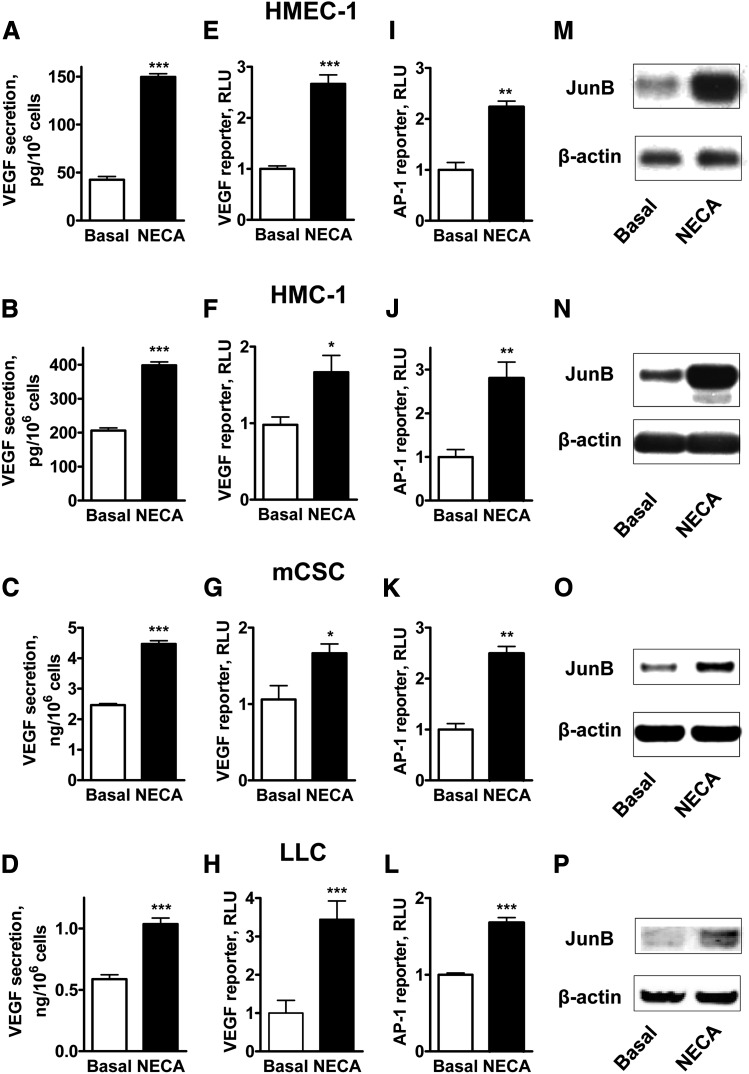

To determine the potential involvement of JunB in adenosine-dependent stimulation of VEGF production, we chose two human cell lines, HMEC-1 and HMC-1, and two mouse cell lines, mCSC and LLC, in all of which the A2B receptor dependent-regulation of VEGF secretion has been described (Feoktistov et al., 2002, 2003; Ryzhov et al., 2008a, 2012). Figure 1 demonstrates that stimulation of adenosine receptors with 10 μM NECA for 6 hours significantly increased VEGF release (Fig 1, A–D) from all cells studied. To determine whether the upregulation of VEGF production by NECA occurs at the transcriptional level, two mouse cell lines mCSC and LLC were transiently transfected with a mouse VEGF promoter-driven luciferase reporter, which encompasses 1.2 kb of the 5′-flanking sequence that includes AP-1 binding sites previously proven to physically interact with JunB (Schmidt et al., 2007). Human cell lines HMEC-1 and HMC-1 were transiently transfected with a homologous human VEGF promoter-driven luciferase reporter. Figure 1, E–H, shows that stimulation of adenosine receptors with 10 μM NECA for 6 hours significantly increased luciferase expression in all cells investigated, indicating that upregulation of VEGF production by NECA can occur at the transcriptional level.

Fig. 1.

NECA-dependent upregulation of VEGF production is associated with an increase in VEGF transcription, AP-1 activity, and JunB accumulation in various human and mouse cell types. HMEC-1 cells (A, E, I, M), HMC-1 cells (B, F, J, N), mCSC cells (C, G, K, O), and LLC cells (D, H, L, P) were either not transfected (A–D, M–P) or transfected with plasmids encoding VEGF (E–H) or AP-1 (I–L) luciferase reporters and were incubated in the absence (Basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA for 6 (A–L) or 3 (M–P) hours. VEGF release (A–D), VEGF (E–H), and AP-1 (I–L) reporter activities and JunB protein levels (M–P) were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3–10) in A–L. Asterisks indicate the statistical difference (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001) compared with basal values by two-tailed unpaired t tests. Representative blots of 3–5 experiments are shown in M–P.

Next, we tested whether stimulation with NECA increases AP-1 reporter activity. We transiently transfected cells with the AP-1 luciferase reporter construct pAP1-luc that contains seven times repeated AP-1–binding sites. Figure 1, I–L, shows that stimulation of adenosine receptors with 10 μM NECA for 6 hours significantly increased luciferase expression in all cells investigated.

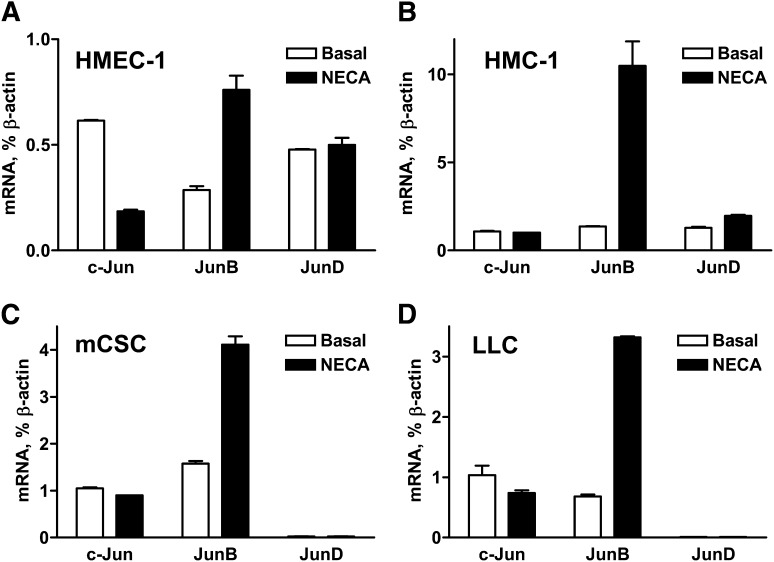

In parallel to the stimulation of the AP-1 and VEGF reporters, Western blot analysis of JunB protein content in cell lysates showed that stimulation of adenosine receptors with 10 μM NECA for 3 hours significantly increased JunB protein accumulation in all cells investigated (Fig. 1, M–P). Furthermore, we found that NECA significantly upregulated the expression of JunB but not the expression of other genes encoding transcription factors from the Jun family (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of NECA on the expression of members of the Jun family transcription factors in cells with adenosine-dependent regulation of VEGF. Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of mRNA encoding c-Jun, JunB, and JunD in (A) HMEC-1 cells, (B) HMC-1 cells, (C) mCSC cells, and (D) LLC cells incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA for 60 minutes. Values are normalized to β-actin mRNA expression and are expressed as the average of two determinations made in triplicate.

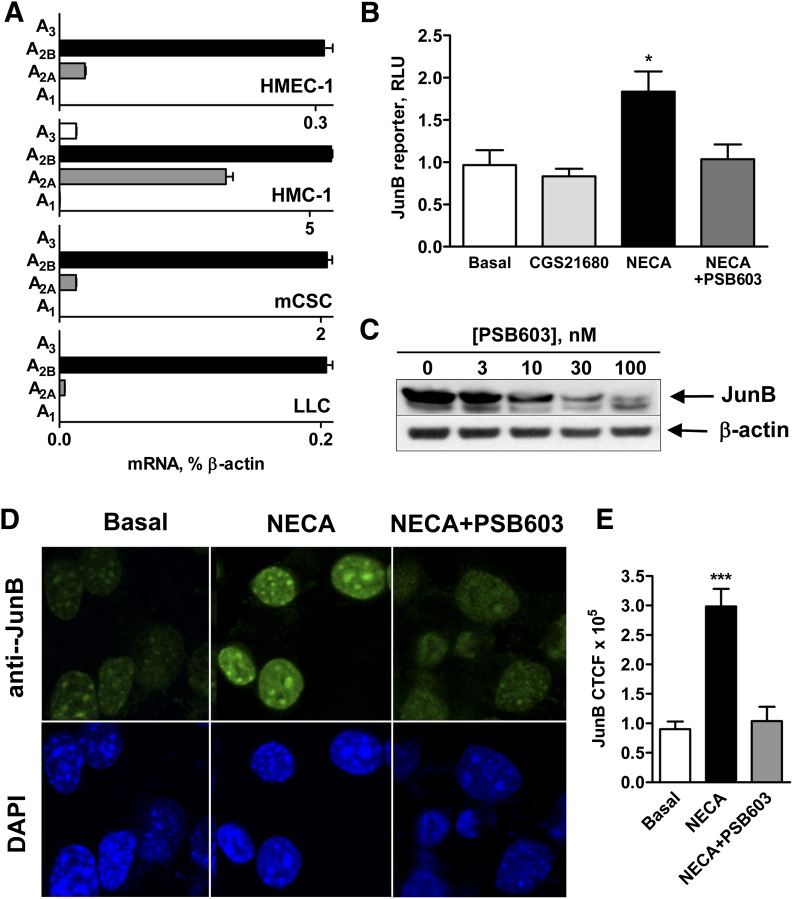

A2B Adenosine Receptors Promote JunB Expression at the Transcriptional Level and Increase Accumulation of JunB Protein in the Nucleus.

The expression of A2B receptors is a common feature of all cells investigated in this study. Figure 3A compares the results of real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of the expression of mRNA encoding subtypes of adenosine receptors in the HMEC-1, HMC-1, mCSC, and LLC cell lines. In addition to the expression of A2B, all cells also expressed A2A receptor transcripts with A2A/A2B receptor ratio lowest in LLC and highest in HMC-1 cells. No other receptor subtype transcripts were detected in these cells except for HMC-1 expressing A3 receptors in addition to A2A and A2B receptors.

Fig. 3.

A2B adenosine receptors mediate an increase in JunB promoter-driven reporter activity and JunB protein accumulation in the nucleus. (A) Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of mRNA encoding adenosine receptor subtypes in HMEC-1 cells, HMC-1 cells, mCSC cells, and LLC cells was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Values are expressed as average of two determinations made in triplicate. (B) Pharmacologic analysis of the role of A2 adenosine receptor subtypes in regulation of JunB promoter-driven reporter activity in LLC cells. LLC cells were transiently transfected with JunB promoter-driven luciferase reporter and then incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of the selective A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 (1 μM), or the nonselective adenosine receptor agonist NECA (10 μM) in the absence or presence of the selective A2B receptor antagonist PSB603 (100 nM) for 3 hours. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). An asterisk indicates the statistical difference (*P < 0.05) compared with basal levels. (C) Effect of increasing concentrations of the selective A2B receptor antagonist PSB603 on JunB protein levels in LLC cells stimulated with 10 μM NECA for 3 hours. A representative blot of three experiments is shown. (D) Pharmacologic analysis of the role of A2B adenosine receptors in regulation of JunB protein accumulation in LLC nuclei. LLC cells were incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of the nonselective adenosine receptor agonist NECA (10 μM) in the absence or presence of the selective A2B receptor antagonist PSB603 (100 nM) for 3 hours. Representative micrographs are shown of anti-JunB–stained LLC cells (green) and nuclei stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) from three experiments. (E) Quantification of the immunofluorescence data shown in D. Fluorescence intensity was measured in seven randomly chosen cells per slide using ImageJ, and the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistical difference (***P < 0.001) compared with basal levels.

To determine whether stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors can promote JunB expression at the transcriptional level, LLC cells were transiently transfected with a mouse JunB promoter-driven luciferase reporter, which encompasses 5′ flanking −870 to +133 base pairs. Figure 3B shows that only the nonselective adenosine agonist NECA (10 μM) but not the selective A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 (1 μM) significantly increased the reporter activity, and this effect was inhibited by the A2B receptor antagonist PSB603 (Borrmann et al., 2009) at a selective concentration of 100 nM.

PSB603 inhibited JunB protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner in whole lysates of LLC cells stimulated with 10 μM NECA for 3 hours (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors promoted JunB accumulation specifically in the cell nucleus. As seen in Fig. 3D, only faint immunofluorescence staining with anti-JunB antibody was detected in the nuclei of control cells (Basal), contrasting with the strong fluorescence present in the nuclei of NECA-treated cells after 3 hours of treatment. No JunB staining was detected in the cytoplasm.

The NECA-induced nuclear accumulation of JunB was reduced to nearly basal levels in the presence of 100 nM PSB603. Quantitative analysis of the immunofluorescence data confirmed a significant increase in JunB staining in cells stimulated with NECA in the absence but not in the presence of PSB603 (Fig. 3E). Taken together, our data suggest that stimulation of A2B receptors can activate the nuclear factor JunB at the transcriptional level, with subsequent accumulation of this protein in the nucleus.

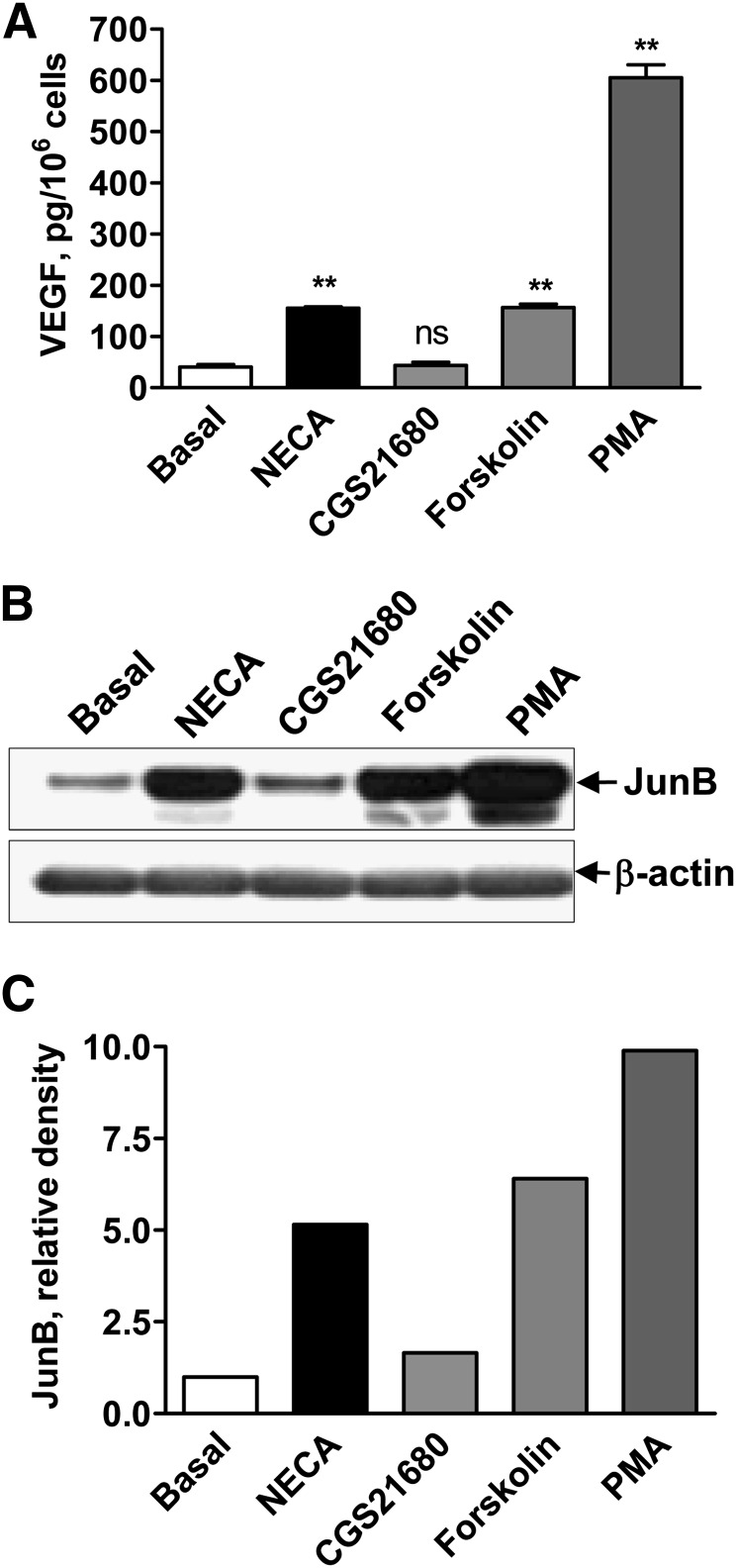

A2B Receptor-Dependent Upregulation of JunB Expression and VEGF Secretion Share Common Intracellular Pathways.

We chose HMEC-1 cells to conduct pharmacologic analysis of the intracellular pathways involved in the adenosine-dependent regulation of JunB protein expression and VEGF secretion because of their robust responses to stimulation of adenosine receptors (Fig. 1, A and M). These cells express A2A and A2B but not A1 or A3 adenosine receptor transcripts (Fig. 3A). The nonselective adenosine agonist NECA (10 μM) induced VEGF secretion (Fig. 4A) and increased JunB protein accumulation (Fig. 4, B and C). In contrast, the A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 had no effect when used at a selective concentration of 1 μM (Fig. 4, A–C). The A2B receptors in HMEC-1 cells are known to couple to Gs and Gq proteins, resulting in accumulation of cAMP and diacylglycerol (DAG)/inositol trisphosphate (Feoktistov et al., 2002). As seen in Fig. 4, stimulation of cAMP-dependent pathways with 1 μM forskolin or DAG-dependent pathways with 10 nM PMA increased both JunB protein expression and VEGF secretion.

Fig. 4.

Stimulation of A2B receptor-linked signaling pathways increases VEGF secretion and JunB protein levels. (A) VEGF release from HMEC-1 cells incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA, 1 μM CGS 21680, 1 μM forskolin, or 10 nM PMA for 6 hours. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significant difference (**P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test) and ns indicates nonsignificant difference compared with basal levels. (B) Western blot analysis of JunB protein levels in HMEC-1 cells incubated in the absence (basal) or presence 10 μM NECA, 1 μM CGS 21680, 1 μM forskolin, or 10 nM PMA for 3 hours. Arrows indicate positions of JunB and β-actin, the latter used as a loading control. A representative blot of three experiments is shown. (C) Graphic representation of data shown in B quantified by densitometry and expressed as relative density of JunB bands normalized to corresponding β-actin bands.

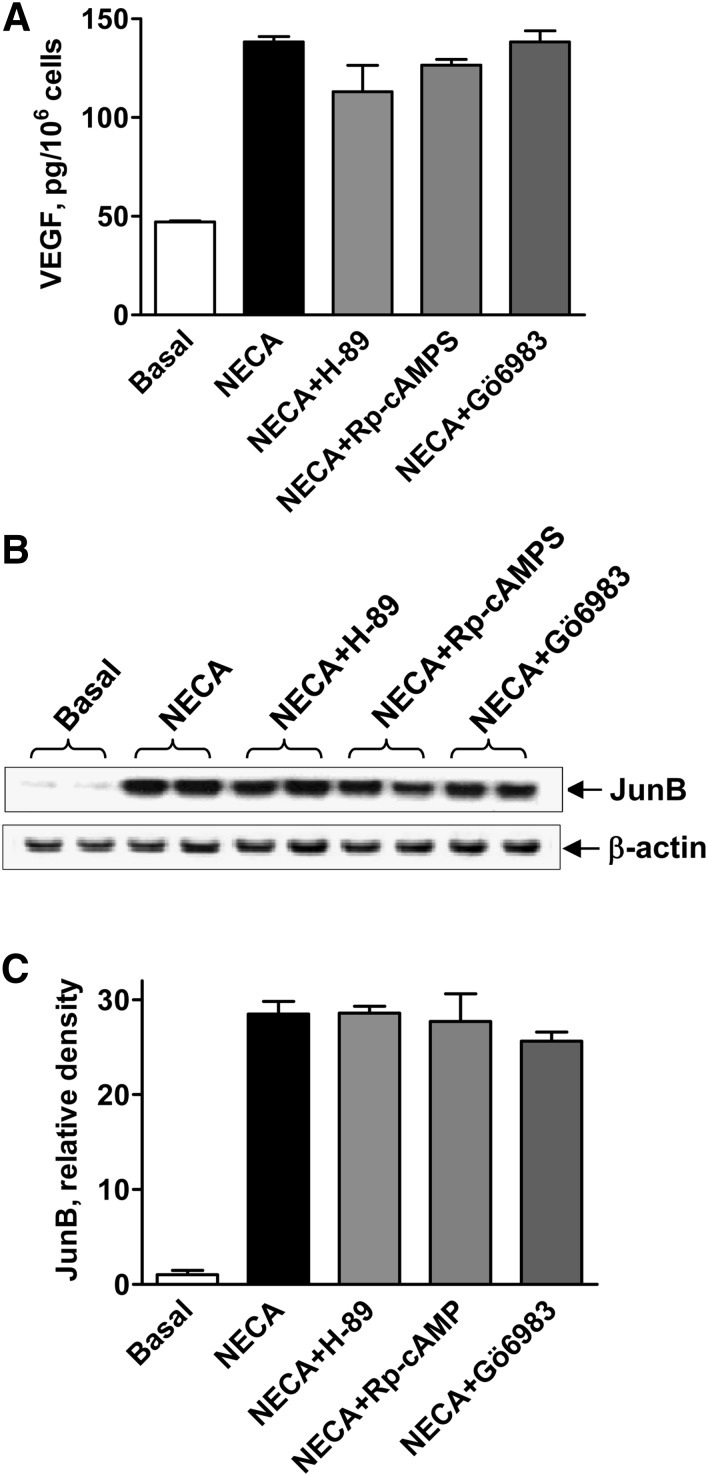

To explore the role of cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathways in adenosine-dependent upregulation of JunB and VEGF, HMEC-1 cells were stimulated with 10 μM NECA in the presence of PKA inhibitors. In ancillary experiments, we monitored cAMP/PKA signal transduction by the activity of luciferase reporter under control of tandem repeats of the cAMP-responsive elements transiently expressed in HMEC-1 cells. We estimated that the PKA inhibitor H-89 inhibited the activity of NECA-stimulated cAMP-responsive element reporter with an IC50 value of 3.2 × 10−7 M (Supplemental Fig. 1). However, 1 μM H-89 had little if any effect on VEGF release induced by 10 μM NECA (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, another PKA inhibitor Rp-cAMPS with a different mechanism of action and reported IC50 values in a low micromolar range (Rothermel et al., 1983) had also no effect on NECA-induced VEGF secretion at concentrations up to 10−4 M (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that adenosine actions on VEGF release are PKA-independent.

Fig. 5.

Effects of inhibitors of protein kinases A and C on A2B receptor-dependent increase in VEGF secretion and JunB protein levels. (A) VEGF secretion from HMEC-1 cells incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA, or in the presence of NECA and 1 μM H-89, 100 μM Rp-cAMPS, or 1 μM Gö6983 for 6 hours. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). (B) Western blot analysis of JunB protein levels in HMEC-1 cells incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA, or in the presence of NECA and 1 μM H-89, 100 μM Rp-cAMPS, or 1 μM Gö6983 for 3 hours. Arrows indicate positions of JunB and β-actin, the latter used as a loading control. A representative blot of three experiments is shown. (C) Graphic representation of data shown in B quantified by densitometry and expressed as relative density of JunB bands normalized to corresponding β-actin bands.

To explore a potential role of protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathways in adenosine-dependent upregulation of JunB and VEGF, we tested effects of the broad-spectrum inhibitor of PKC Gö6983, with reported IC50 values for most isoforms in a low nanomolar range (Gschwendt et al., 1996), on NECA-induced VEGF secretion. We found that 1 μM Gö6983 had no effect on NECA-induced VEGF secretion (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that Gö6983-sensitive PKC isoforms play no role in NECA-induced VEGF secretion. In parallel to their lack of effects on NECA-induced VEGF release, the PKA inhibitors H89 (1 μM) and Rp-cAMPS (100 μM), and the PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (1 μM) had also no effect on NECA-induced JunB protein accumulation in HMEC-1 cells (Fig. 5, B and C).

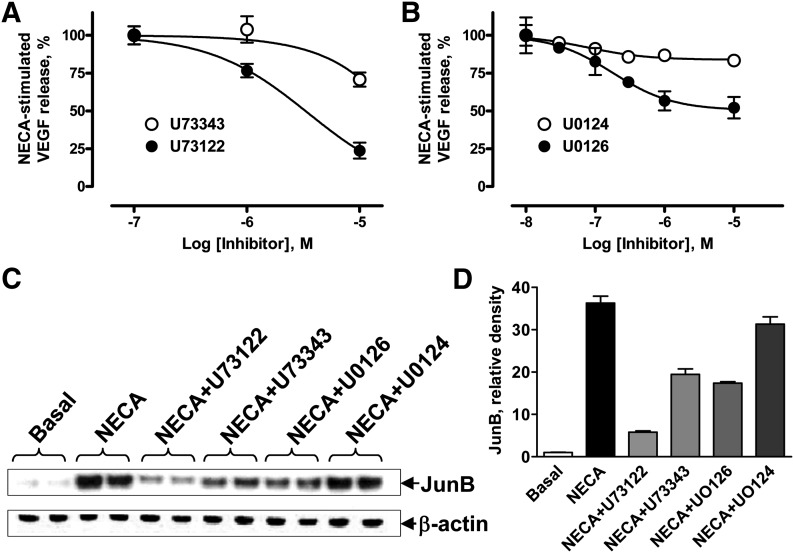

We next evaluated a potential role of alternative signaling pathways in A2B receptor-dependent VEGF production by using inhibitors of phospholipase C (PLC)-β (Fig. 6A) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) 1/2 (Fig. 6B). From these experiments we chose concentrations of inhibitors to test their effects on A2B receptor-dependent JunB protein accumulation (Fig. 6, C and D). To explore the role of A2B receptor-Gq–linked PLC-β pathways in adenosine-dependent upregulation of VEGF, we used the PLC inhibitor U73122 and its succinimido analog U73343 as a negative control (Bleasdale et al., 1990). Figure 6A shows that U73122 at concentrations of 1–10 μM produced a greater inhibition of NECA-stimulated VEGF release from HMEC-1 compared with U73343. A similar difference between U73122 and U73343 in their inhibitory actions on JunB protein accumulation was observed when these compounds were added at concentrations of 10 μM before stimulation of HMEC-1 cells with NECA (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 6.

Effects of PLC and MEK inhibition on VEGF secretion and JunB levels in HMEC-1 cells. (A) Effect of the PLC inhibitor U73122 (●) and its inactive control analog U73343 (○) on VEGF secretion from cells stimulated with 10 μM NECA. In the absence of inhibitors, 10 μM NECA increased concentrations of VEGF in the medium from 47 ± 1 to 138 ± 1 pg/106 cells. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 6). (B) Effect of increasing concentrations of the MEK inhibitor U0126 (●) and its inactive control analog U0124 (○) on VEGF secretion from cells stimulated with 10 μM NECA. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). (C) Western blot analysis of JunB protein levels in HMEC-1 cells incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA, or in the presence of NECA and 10 μM U73122, 10 μM U73343, 1 μM U0126, or 1 μM U0124 for 3 hours. Arrows indicate positions of JunB and β-actin, the latter used as a loading control. A representative blot of three experiments is shown. (D) Graphic representation of data shown in C quantified by densitometry and expressed as relative density of JunB bands normalized to corresponding β-actin bands.

We have previously reported that inhibition of MEK1/2 with U0126 partially reduced A2B receptor-dependent VEGF production in human and mouse mast cells (Ryzhov et al., 2008b). Therefore, we compared the effects of MEK1/2 inhibition on NECA-induced VEGF release and JunB protein accumulation in HMEC-1 cells. As seen in Fig. 6B, the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 at concentrations of 1–10 μM inhibited VEGF release by approximately 50%. In contrast, the inactive form of MEK1/2 inhibitor U0124 had no effect on NECA-dependent VEGF secretion at concentrations up to 10 μM. Similarly, 1 μM U0126 produced partial inhibition of NECA-induced JunB protein accumulation, whereas 1 μM U0124 had no effect (Fig. 6, C and D). However, U0126 at this concentration almost completely blocked ERK activity (Supplemental Fig. 2). Taken together, our data suggest that ERK1/2 activated by MEK1/2 may be partially responsible not only for NECA-induced VEGF release but also for JunB protein accumulation.

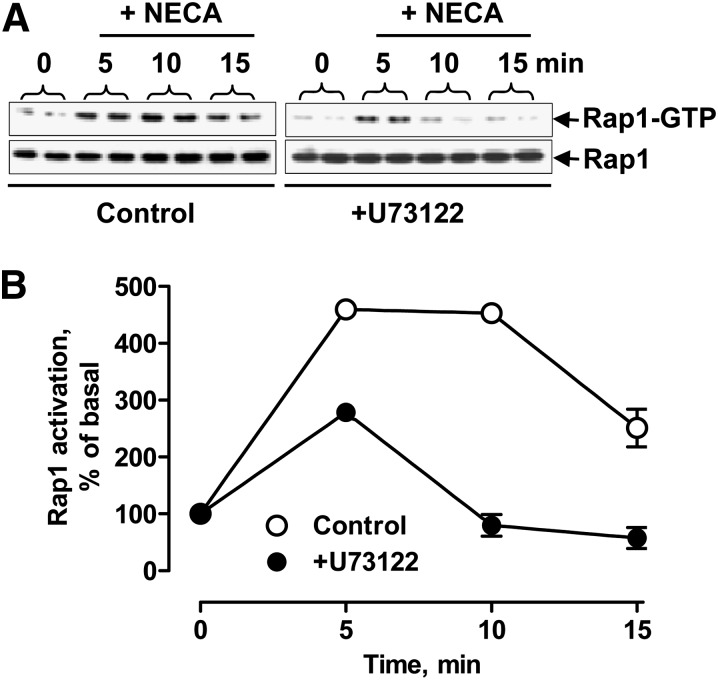

Calcium diacylglycerol guanine nucleotide exchange factor (CalDAG-GEF)–Rap1 pathway has been implicated in PMA-dependent ERK activation, thus providing a potential link between PLC and ERK (Stork and Dillon, 2005). To determine whether stimulation of adenosine receptors leads to PLC-dependent activation of Rap1 in HMEC-1, we stimulated cells with 10 μM NECA in the absence or presence of 10 μM U73122 and measured Rap1 activation. As seen in Fig. 7, stimulation of adenosine receptors with NECA indeed induces transient activation of Rap1. The NECA-induced activation of Rap1 was considerably lower in the presence of the PLC inhibitor U73122.

Fig. 7.

Effect of PLC inhibition on adenosine-dependent Rap1 activation. (A) Western blot analysis of active GTP-bound form of Rap1 obtained by glutathione S-transferase-Ral-GDS pull-down before and 5, 10, and 15 minutes after stimulation of HMEC-1 cells with 10 μM NECA in the absence (control) and presence of 10 μM U73122. Total Rap1 protein levels in corresponding cell lysate aliquots are shown in the bottom panels. Representative blots of three experiments are shown. (B) Graphic representation of data shown in A quantified by densitometry and expressed as a percentage of the corresponding levels in resting cells normalized to total Rap-1 protein levels used as internal control.

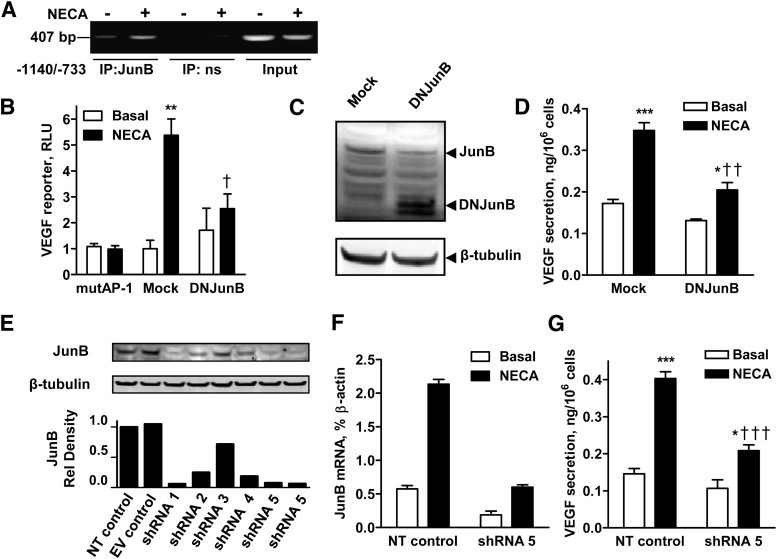

JunB Binding to the VEGF Promoter Is an Important Step in the A2B Receptor-Dependent Stimulation of VEGF Production.

Previous studies have identified the AP-1 recognition site located at position −1093 to −1086 of the murine VEGF promoter as the only high-affinity JunB-binding site and demonstrated that JunB acts primarily through this element to stimulate VEGF transcription during hypoxia (Schmidt et al., 2007). To prove that stimulation of A2B receptors induces physical interaction of JunB with the VEGF promoter, ChIP analysis was performed in LLC cells incubated in the absence or presence of 10 μM NECA. Primers were designed to amplify the region of the VEGF promoter (−1140 to −733) containing the high-affinity AP-1 site. We found weak basal JunB binding to this promoter region in the absence of NECA, which was considerably enhanced in cells stimulated with NECA (Fig. 8A). To demonstrate the requirement of JunB binding to the high-affinity AP-1 site for the A2B receptor-dependent stimulation of VEGF transcription, we used a luciferase reporter analysis. As seen in Fig. 8B, mutation of the high-affinity AP-1 site (−1093 to −1086) within the murine promoter fragment resulted in a loss of stimulation of luciferase activity by NECA. To further ascertain the role of JunB in the A2B receptor-dependent regulation of VEGF transcription, a plasmid encoding dominant negative mutant of JunB (DNJunB) or an empty expression vector (mock transfection) was cotransfected with VEGF promoter-driven luciferase reporter in LLC cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 μM NECA for an additional 6 hours. Figure 8B shows that the expression of DNJunB significantly suppressed NECA-stimulated reporter activity.

Fig. 8.

Role of JunB in A2B receptor-dependent VEGF production. (A) Effect of NECA on JunB binding to the VEGF promoter. ChIP analysis was performed using an antibody specific for JunB (IP: JunB) and IgG as a nonspecific control (IP: ns). Specific primer sets were used for the promoter region harboring the AP-1 site (−1140 to −733). JunB binding to the VEGF promoter region between −1140 and −733 was detected and was enhanced in LLC cells treated with 10 µM NECA for 3 hours. (B) Effects of AP-1 site mutation and dominant negative JunB on VEGF reporter activity. The role of JunB in A2B receptor-dependent regulation of the VEGF gene promoter was studied in LLC cells transiently cotransfected with VEGF luciferase reporter together with plasmid encoding DNJunB or with an empty vector (mock). A set of LLC cells was also transfected with VEGF luciferase reporter containing the mutated AP-1 site at −1093 (indicated on graph as mutAP-1). Twenty-four hours after transfections, cells were incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA for an additional 6 hours. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). Asterisks indicate statistical difference (**P < 0.01) compared with basal levels, and a dagger indicates the statistical difference (†P < 0.05) compared with mock controls by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. (C) Expression of JunB and DNJunB in LLC cells stably transfected with plasmid encoding DNJunB or with an empty vector (mock). Western blot analysis was performed using antibodies against a common epitope in the sequences of JunB and DNJunB. Arrows indicate positions of JunB and DNJunB. Immunostaining of β-tubulin was used as a loading control. (D) Effect of the expression of dominant negative JunB on VEGF secretion. The role of JunB in A2B receptor-dependent regulation of VEGF secretion was studied in LLC cells stably transfected with plasmid encoding DNJunB or with an empty vector (mock) by measuring VEGF release from cells incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA for 6 hours. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). Asterisks indicate statistical difference (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001) compared with basal levels; daggers indicate statistical difference (††P < 0.01) compared with mock controls by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test. (E) Efficacy of JunB silencing after stable lentiviral transfection of LLC cells with different shRNA constructs (shRNA1-5) compared with shRNA nontargeting (NT) and empty vector (EV) controls. Upper panels show representative Western blots of basal levels of targeted JunB protein and β-tubulin loading controls. The lower panel is a graphic representation of the data expressed as relative density of JunB bands normalized to corresponding β-tubulin bands and NT control. (F) Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of JunB mRNA levels in LLC cells stably transfected with lentiviral vectors encoding shRNA5 or nontargeting shRNA (NT control). Cells were incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA for 60 minutes. Values are normalized to β-actin mRNA expression and expressed as the average of two determinations made in triplicate. (G) Effect of JunB knockdown on VEGF secretion. The role of JunB in A2B receptor-dependent regulation of the VEGF secretion was studied in LLC cells stably expressing JunB silencing shRNA5 or nontargeting shRNA (NT control) incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 10 μM NECA for 6 hours. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). Asterisks indicate statistical difference (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001) compared with basal levels; daggers indicate statistical difference (†††P < 0.001) compared with NT controls by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

To further demonstrate the role of JunB in A2B receptor-dependent regulation of VEGF secretion, we established LLC colonies that either stably expressed DNJunB or underwent mock transfection with an empty vector. DNJunB protein expression was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 8C). Images of full-length gels are shown in Supplemental Fig. 3. We found that the stable expression of DNJunB resulted in significant suppression of NECA-induced VEGF secretion (Fig. 8C). It should be noted that the expression of DNJunB also affected basal VEGF secretion to some extent. However, a relative increase in VEGF secretion induced by NECA was still considerably lower in cells expressing DNJunB compared with mock-transfected control (1.5- and 2-fold, respectively).

Finally, we used an RNA interference approach to evaluate the effect of JunB knockdown on the A2B receptor-dependent VEGF production. Based on Western blot analysis of efficacy of JunB silencing after stable lentiviral transfection of LLC cells with different JunB shRNA constructs (shRNA1-5; Fig. 8E), we selected cells expressing shRNA5 for further experiments. We confirmed that both basal and NECA-induced JunB mRNA levels were largely suppressed in LLC cells expressing shRNA5 compared with cells expressing nontargeting control shRNA (Fig. 8F). We found that JunB knockdown resulted in significant suppression of NECA-induced VEGF secretion (Fig. 8G) similar to that seen in cells expressing DNJunB (Fig. 8D). Taken together, our results suggest that JunB plays an important role in the A2B receptor-dependent regulation of VEGF transcription.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated for the first time that JunB protein accumulation is induced in response to stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors in different types of murine and human cells. A2B receptor-dependent regulation of JunB abundance can occur at the transcriptional level, as evidenced from stimulation of a JunB reporter by the adenosine analog NECA, which was blocked by the selective A2B receptor antagonist PSB603. Stimulation with NECA induced a robust increase in JunB transcripts in all cells under investigation. In contrast, the expression of c-Jun was rather downregulated by NECA, albeit to a different extent depending on the cell type. NECA had little if any effect on the expression of JunD. Thus, our results suggest that of all members of the Jun subfamily, JunB is the principal target of A2B receptor signaling. Using an AP-1 reporter, we confirmed that adenosine-dependent increase in JunB results in formation of functional AP-1 proteins in these cells.

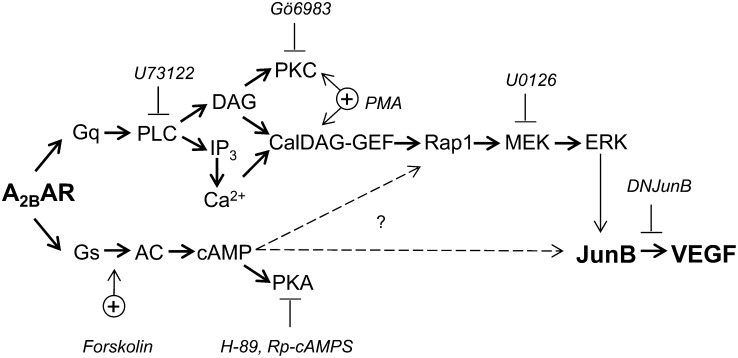

AP-1 proteins have been implicated in the induction of VEGF expression by UVB irradiation in fibroblasts (Dong et al., 2012), by hyperbaric oxygen in endothelial cells (Lee et al., 2006), and by tumor necrosis factor α in breast cancer cells (Yin et al., 2009). Because physical interaction of JunB with AP-1 binding sites of the VEGF promoter and subsequent stimulation of VEGF secretion have been previously demonstrated in fibroblasts and endothelial cells upon stimulation with hypoxia (Schmidt et al., 2007) or hypoglycemia (Textor et al., 2006), our new findings raised a possibility that JunB can be involved also in the upregulation of VEGF by A2B receptor signaling. We investigated signaling pathways linked to A2B receptors that may lead to JunB protein accumulation and VEGF secretion in HMEC-1 cells (Fig. 9). These cells express mRNA encoding A2A and A2B receptors, but not other adenosine receptor subtypes. Both A2A and A2B receptors are known to be coupled to Gs proteins linked to stimulation of adenylate cyclase and accumulation of cAMP (Fredholm et al., 2001). However, we have previously shown that only A2B receptors are functionally coupled to adenylate cyclase in these cells because only NECA but not the selective A2A agonist CGS 21680 stimulated cAMP accumulation (Feoktistov et al., 2002). In agreement with these data, CGS 21680 had no effect on either JunB or VEGF.

Fig. 9.

Schematic representation of A2B receptor-stimulated intracellular pathways involved in regulation of VEGF. A2B adenosine receptors (A2BAR) are coupled to adenylate cyclase (AC) via Gs proteins. Activation of this pathway results in accumulation of cAMP and stimulation of PKA. A2BAR are coupled also to PLC via a GTP-binding protein of the Gq family. Activation of this pathway results in accumulation of DAG and inositol trisphosphate (IP3), and the latter triggers mobilization of calcium from intracellular stores (Feoktistov and Biaggioni, 1995). In this study, we present evidence that A2BAR increase JunB protein levels and VEGF production via stimulation of PLC and ERK, which are possibly linked by the CalDAG-GEF–Rap1 pathway. PMA, an activator of PKC and CalDAG-GEF, also increased JunB protein levels and VEGF production. However, the broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor Gö6983 had no effect on the A2BAR-dependent increase in JunB protein levels and VEGF production. In contrast, the PLC inhibitor U73122 inhibited the A2BAR-dependent Rap1 activation, the increase in JunB protein levels, and VEGF production. The MEK inhibitor U0126 blocked the A2BAR-dependent stimulation of ERK and inhibited an increase in JunB protein levels and VEGF production. Stimulation of AC by forskolin also increased JunB protein levels and VEGF production. Broken arrows in the diagram signify potential effects of cAMP. These effects are PKA-independent because the PKA inhibitors with different mechanisms of action H-89 and Rp-cAMPS had no effect on the A2BAR-dependent increase in JunB protein levels and VEGF production. Finally, the overexpression of a DNJunB inhibited A2BAR-dependent increase in VEGF transcription and secretion, indicating an important role of JunB in this process.

In various cells including HMEC-1, A2B adenosine receptors were shown to not only stimulate adenylate cyclase via coupling to Gs, but also stimulate PLCβ via a GTP-binding protein of the Gq family resulting in accumulation of DAG and inositol trisphosphate (Feoktistov and Biaggioni, 1995; Linden et al., 1999; Feoktistov et al., 2002; Ryzhov et al., 2009). In the present study, we found that stimulation of adenylate cyclase by forskolin or activation of DAG-dependent pathways with PMA increased JunB protein levels and VEGF production. Further analysis employing inhibitors of PLC-linked pathways revealed their essential role in A2B receptor-dependent regulation of both JunB and VEGF. Inhibition of PLC with U73122 reduced A2B receptor-dependent JunB protein accumulation and VEGF secretion.

The most prominent intracellular targets of DAG and the functionally analogous phorbol esters belong to the PKC family (Ron and Kazanietz, 1999). However, the broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor Gö6983 had no effect on the A2B receptor-dependent increase in JunB protein levels and VEGF production. In addition to stimulation of PKC, PMA is known to activate CalDAG-GEF–Rap1 pathway, eventually leading to activation of ERK (Stork and Dillon, 2005). In the current study, we demonstrated that this pathway is indeed activated by stimulation of A2B receptors. Inhibition of NECA-induced Rap1 activation by the PLC inhibitor U73122 suggests that Rap1 and its activator CalDAG-GEF, which is known to respond to calcium and DAG (Kawasaki et al., 1998), are targets of A2B receptor-activated PLCβ. Although A2 receptor-dependent stimulation of Rap1 has been previously reported in cells overexpressing A2 receptors (Seidel et al., 1999; Schulte and Fredholm, 2003), this is the first evidence of PLC involvement in this process.

Further downstream, inhibition of A2B receptor-dependent stimulation of ERK with U0126 resulted in a partial inhibition of both JunB protein accumulation and VEGF production. Because complete inhibition of A2B receptor-dependent upregulation of JunB and VEGF was not achieved even at U0126 concentrations that almost entirely blocked ERK activity, it is likely that additional pathways are involved in this mechanism. Although stimulation of adenylate cyclase by forskolin also increased JunB protein levels and VEGF production, our data suggest involvement of PKA-independent pathways in this process because the PKA inhibitors with different mechanisms of action H89 and Rp-cAMPS had no effect on the A2B receptor-dependent increase in JunB protein levels and VEGF production.

A2B receptor-dependent stimulation of exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP, which are known to activate Rap1 (de Rooij et al., 1998), was recently demonstrated in endothelial cells (Fang and Olah, 2007). Whether this mechanism involved in A2B receptor-dependent increase in JunB protein levels and VEGF production remains to be elucidated. Finally, the overexpression of dominant negative mutant of JunB or JunB knockdown with shRNA inhibited A2B receptor-dependent increase in VEGF production, indicating an important role of JunB in this process. Thus, despite the apparent complexity and potential crosstalk between signaling pathways, our inhibitory analysis revealed a clear association and causal relationship between A2B receptor-dependent regulation of JunB accumulation and VEGF secretion.

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated that A2B adenosine receptor-dependent upregulation of JunB is a common feature shared by different cells known to be involved in angiogenesis. In addition to the regulation of VEGF production examined in this study, JunB has been implicated in cell cycle regulation (Hess et al., 2004), endothelial cell morphogenesis (Licht et al., 2006), osteoblast differentiation (Kenner et al., 2004), myeloid cell differentiation (Passegue et al., 2001), mast cell degranulation, and cytokine release (Textor et al., 2007). Almost all of these events are reportedly regulated also by adenosine via A2B receptors (Feoktistov and Biaggioni, 1995, 1997; Auchampach et al., 1997; Grant et al., 2001; Novitskiy et al., 2008; Ryzhov et al., 2011; Carroll et al., 2012). Therefore, it would be interesting to determine whether upregulation of JunB represents a common and important step in A2B receptor-dependent regulation of these cell functions by extracellular adenosine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. N. Issaeva (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) for help with immunofluorescence confocal microscopy and Dr. J. H. Butterfield (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) for providing the HMC-1 cell line. The authors also thank Dr. G. L. Semenza (Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore), Dr. P. A. D’Amore (Harvard University, Boston MA), Dr. M. Schorpp-Kistner (DKFZ-German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany), and Dr. Mitsuyasu Kato (University of Tsukuba, Japan) for generous gifts of human VEGF promoter-driven luciferase reporter, mouse VEGF promoter-driven luciferase reporter, mouse VEGF luciferase reporter with mutated AP-1 site, and dominant negative JunB mutant expression plasmids, respectively.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- CalDAG-GEF

calcium diacylglycerol guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- CGS 21680

2-p-(2-carboxyethyl) phenylethylamino-NECA

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DNJunB

dominant negative mutant of JunB

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- Gö6983

3-[1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-5-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl]-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione

- H-89

N-[2-((p-bromocinnamyl)amino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide, dihydrochloride

- HIF-1

hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- HMC-1

human mast cell line

- HMEC-1

human microvascular endothelial cell line

- LLC

Lewis lung carcinoma

- mCSC

mouse cardiac Sca-1+CD31− stromal cells

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PSB603

8-[4-[4-((4-chlorophenzyl)piperazide-1-sulfonyl)phenyl]]-1-propylxanthine

- Rp-cAMPS

Rp-adenosine 2′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate

- Rap1

Ras-proximate-1

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- U0126

1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio)butadiene

- U0124

1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(methylthio)butadiene

- U73122

1-(6-{[17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5-(10)triene-17-yl]amino}hexyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione

- U73343

1-(6-{[17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5-(10)triene-17-yl]amino}hexyl)-2,5-pyrrolidine-dione

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Ryzhov, Biktasova, Dikov, Feoktistov.

Conducted experiments: Ryzhov, Biktasova, Goldstein, Zhang.

Performed data analysis: Ryzhov, Biktasova, Feoktistov.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Ryzhov, Biktasova, Dikov, Biaggioni, Feoktistov.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant R01 HL095787] (to I.F.); and the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grant R01 CA138923] (to M.M.D. and I.F.).

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Adair TH. (2005) Growth regulation of the vascular system: an emerging role for adenosine. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289:R283–R296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alchera E, Tacchini L, Imarisio C, Dal Ponte C, De Ponti C, Gammella E, Cairo G, Albano E, Carini R. (2008) Adenosine-dependent activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 induces late preconditioning in liver cells. Hepatology 48:230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchampach JA, Jin X, Wan TC, Caughey GH, Linden J. (1997) Canine mast cell adenosine receptors: cloning and expression of the A3 receptor and evidence that degranulation is mediated by the A2B receptor. Mol Pharmacol 52:846–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleasdale JE, Thakur NR, Gremban RS, Bundy GL, Fitzpatrick FA, Smith RJ, Bunting S. (1990) Selective inhibition of receptor-coupled phospholipase C-dependent processes in human platelets and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 255:756–768 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrmann T, Hinz S, Bertarelli DC, Li W, Florin NC, Scheiff AB, Müller CE. (2009) 1-alkyl-8-(piperazine-1-sulfonyl)phenylxanthines: development and characterization of adenosine A2B receptor antagonists and a new radioligand with subnanomolar affinity and subtype specificity. J Med Chem 52:3994–4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SH, Wigner NA, Kulkarni N, Johnston-Cox H, Gerstenfeld LC, Ravid K. (2012) A2B adenosine receptor promotes mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to osteoblasts and bone formation in vivo. J Biol Chem 287:15718–15727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. (1998) Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 396:474–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ponti C, Carini R, Alchera E, Nitti MP, Locati M, Albano E, Cairo G, Tacchini L. (2007) Adenosine A2a receptor-mediated, normoxic induction of HIF-1 through PKC and PI-3K-dependent pathways in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 82:392–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Li Y, Gao M, Hu M, Li X, Mai S, Guo N, Yuan S, Song L. (2012) IKKα contributes to UVB-induced VEGF expression by regulating AP-1 transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res 40:2940–2955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Olah ME. (2007) Cyclic AMP-dependent, protein kinase A-independent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 following adenosine receptor stimulation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: role of exchange protein activated by cAMP 1 (Epac1). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322:1189–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I. (1995) Adenosine A2b receptors evoke interleukin-8 secretion in human mast cells. An enprofylline-sensitive mechanism with implications for asthma. J Clin Invest 96:1979–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I. (1997) Adenosine A2B receptors. Pharmacol Rev 49:381–402 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I, Cronstein BN. (2009) Adenosine receptors in wound healing, fibrosis and angiogenesis. Handbook Exp Pharmacol 193:383–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Goldstein AE, Ryzhov S, Zeng D, Belardinelli L, Voyno-Yasenetskaya T, Biaggioni I. (2002) Differential expression of adenosine receptors in human endothelial cells: role of A2B receptors in angiogenic factor regulation. Circ Res 90:531–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Ryzhov S, Goldstein AE, Biaggioni I. (2003) Mast cell-mediated stimulation of angiogenesis: cooperative interaction between A2B and A3 adenosine receptors. Circ Res 92:485–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza GL. (1996) Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 16:4604–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. (2001) International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 53:527–552 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessi S, Fogli E, Sacchetto V, Merighi S, Varani K, Preti D, Leung E, Maclennan S, Borea PA. (2010) Adenosine modulates HIF-1α, VEGF, IL-8, and foam cell formation in a human model of hypoxic foam cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30:90–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MB, Davis MI, Caballero S, Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I, Belardinelli L. (2001) Proliferation, migration, and ERK activation in human retinal endothelial cells through A2B adenosine receptor stimulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42:2068–2073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MB, Tarnuzzer RW, Caballero S, Ozeck MJ, Davis MI, Spoerri PE, Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. (1999) Adenosine receptor activation induces vascular endothelial growth factor in human retinal endothelial cells. Circ Res 85:699–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwendt M, Dieterich S, Rennecke J, Kittstein W, Mueller HJ, Johannes FJ. (1996) Inhibition of protein kinase C μ by various inhibitors. Differentiation from protein kinase C isoenzymes. FEBS Lett 392:77–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess J, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. (2004) AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J Cell Sci 117:5965–5973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikebe D, Wang B, Suzuki H, Kato M. (2007) Suppression of keratinocyte stratification by a dominant negative JunB mutant without blocking cell proliferation. Genes Cells 12:197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Liu Zg, Zandi E. (1997) AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 9:240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Toki S, Canales JJ, Harlan P, Blumenstiel JP, Chen EJ, Bany IA, Mochizuki N, Ashbacher A, et al. (1998) A Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor enriched highly in the basal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13278–13283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenner L, Hoebertz A, Beil FT, Keon N, Karreth F, Eferl R, Scheuch H, Szremska A, Amling M, Schorpp-Kistner M, et al. (2004) Mice lacking JunB are osteopenic due to cell-autonomous osteoblast and osteoclast defects. J Cell Biol 164:613–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Chen SC, Tsai SC, Wang BW, Liu YC, Lee HM, Shyu KG. (2006) Hyperbaric oxygen induces VEGF expression through ERK, JNK and c-Jun/AP-1 activation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Biomed Sci 13:143–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht AH, Pein OT, Florin L, Hartenstein B, Reuter H, Arnold B, Lichter P, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. (2006) JunB is required for endothelial cell morphogenesis by regulating core-binding factor beta. J Cell Biol 175:981–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J, Thai T, Figler H, Jin X, Robeva AS. (1999) Characterization of human A2B adenosine receptors: radioligand binding, western blotting, and coupling to Gq in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and HMC-1 mast cells. Mol Pharmacol 56:705–713 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Leung E, Maclennan S, Baraldi PG, Borea PA. (2005) A3 adenosine receptors modulate hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression in human a375 melanoma cells. Neoplasia 7:894–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Leung E, Maclennan S, Borea PA. (2006) Adenosine modulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in human glioblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol 72:19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt SA, Horton MA. (1992) A nonradioactive biochemical characterization of membrane proteins using enhanced chemiluminescence. Anal Biochem 206:267–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitskiy SV, Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Huang Y, Tikhomirov OY, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, Carbone DP, Feoktistov I, et al. (2008) Adenosine receptors in regulation of dendritic cell differentiation and function. Blood 112:1822–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagès G, Pouysségur J. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene—a concert of activating factors. Cardiovasc Res 65:564–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passegué E, Jochum W, Schorpp-Kistner M, Möhle-Steinlein U, Wagner EF. (2001) Chronic myeloid leukemia with increased granulocyte progenitors in mice lacking junB expression in the myeloid lineage. Cell 104:21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan M, Luo W, Csóka B, Haskó G, Lukashev D, Sitkovsky MV, Leibovich SJ. (2009) Differential regulation of HIF-1α isoforms in murine macrophages by TLR4 and adenosine A2A receptor agonists. J Leukoc Biol 86:681–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan M, Pinhal-Enfield G, Hao I, Leibovich SJ. (2007) Synergistic up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in macrophages by adenosine A2A receptor agonists and endotoxin involves transcriptional regulation via the hypoxia response element in the VEGF promoter. Mol Biol Cell 18:14–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Kazanietz MG. (1999) New insights into the regulation of protein kinase C and novel phorbol ester receptors. FASEB J 13:1658–1676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel JD, Stec WJ, Baraniak J, Jastorff B, Botelho LH. (1983) Inhibition of glycogenolysis in isolated rat hepatocytes by the Rp diastereomer of adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-phosphorothioate. J Biol Chem 258:12125–12128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryzhov S, Goldstein AE, Novitskiy SV, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. (2012) Role of A2B adenosine receptors in regulation of paracrine functions of stem cell antigen 1-positive cardiac stromal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341:764–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryzhov S, Novitskiy SV, Goldstein AE, Biktasova A, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, Dikov MM, Feoktistov I. (2011) Adenosinergic regulation of the expansion and immunosuppressive activity of CD11b+Gr1+ cells. J Immunol 187:6120–6129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryzhov S, Novitskiy SV, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Carbone DP, Biaggioni I, Dikov MM, Feoktistov I. (2008a) Host A2B adenosine receptors promote carcinoma growth. Neoplasia 10:987–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Matafonov A, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. (2009) Differential role of the carboxy-terminus of the A2B adenosine receptor in stimulation of adenylate cyclase, phospholipase Cβ, and interleukin-8. Purinergic Signal 5:289–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Novitskiy SV, Dikov MM, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. (2008b) Effect of A2B adenosine receptor gene ablation on proinflammatory adenosine signaling in mast cells. J Immunol 180:7212–7220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Textor B, Pein OT, Licht AH, Andrecht S, Sator-Schmitt M, Fusenig NE, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. (2007) Critical role for NF-κB-induced JunB in VEGF regulation and tumor angiogenesis. EMBO J 26:710–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorpp-Kistner M, Wang ZQ, Angel P, Wagner EF. (1999) JunB is essential for mammalian placentation. EMBO J 18:934–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte G, Fredholm BB. (2003) The Gs-coupled adenosine A2B receptor recruits divergent pathways to regulate ERK1/2 and p38. Exp Cell Res 290:168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel MG, Klinger M, Freissmuth M, Höller C. (1999) Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by the A2A-adenosine receptor via a rap1-dependent and via a p21ras-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 274:25833–25841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima DT, Kuroki M, Deutsch U, Ng YS, Adamis AP, D’Amore PA. (1996) The mouse gene for vascular endothelial growth factor. Genomic structure, definition of the transcriptional unit, and characterization of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory sequences. J Biol Chem 271:3877–3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork PJ, Dillon TJ. (2005) Multiple roles of Rap1 in hematopoietic cells: complementary versus antagonistic functions. Blood 106:2952–2961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor B, Licht AH, Tuckermann JP, Jessberger R, Razin E, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M, Hartenstein B. (2007) JunB is required for IgE-mediated degranulation and cytokine release of mast cells. J Immunol 179:6873–6880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor B, Sator-Schmitt M, Richter KH, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. (2006) c-Jun and JunB are essential for hypoglycemia-mediated VEGF induction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1091:310–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Wang S, Sun Y, Matt Y, Colburn NH, Shu Y, Han X. (2009) JNK/AP-1 pathway is involved in tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in MCF7 cells. Biomed Pharmacother 63:429–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D, Maa T, Wang U, Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I, Belardinelli L. (2003) Expression and function of A2B adenosine receptors in the U87MG tumor cells. Drug Dev Res 58:405–411 DOI: 10.1002/ddr.10212. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.