Abstract

Anthropologists and psychiatrists traditionally have used the salience of a mind–body dichotomy to distinguish Western from non-Western ethnopsychologies. However, despite claims of mind–body holism in non-Western cultures, mind–body divisions are prominent in non-Western groups. In this article, we discuss three issues: the ethnopsychology of mind–body dichotomies in Nepal, the relationship between mind–body dichotomies and the hierarchy of resort in a medical pluralistic context, and, lastly, the role of mind–body dichotomies in public health interventions (biomedical and psychosocial) aimed toward decreasing the stigmatization of mental illness. We assert that, by understanding mind–body relations in non-Western settings, their implications, and ways in which to reconstitute these relations in a less stigmatizing manner, medical anthropologists and mental health workers can contribute to the reduction of stigma in global mental healthcare.

Keywords: mind–body dichotomies, stigma, ethnopsychiatry, psychosocial, Nepal

Case one: Naresh1

“We were very relieved when the psychiatrist told us that Naresh did not have a mental illness. There is nothing wrong with his dimaag (brain-mind),” Naresh's mother explained to one of the authors a few weeks after she and her son visited the psychiatric outpatient department of a major hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. Naresh, an 11-year-old boy living in Kathmandu, had been suffering from headaches, nausea, vomiting, sudden episodes of sweating and facial flush, and repeated visions of his neighbor's corpse hanging. The family had pursued multiple forms of treatment including pediatricians, gastroenterologists, psychiatrists, a clinical psychologist, and a traditional healer. His diagnoses included intestinal parasites, posttraumatic stress disorder, and soul loss.

Naresh's father asserted that this was a gland problem because Naresh was nearing puberty. The boy's 18-year-old sister attributed his distress to puberty with the added explanation that, “It started when his gym teacher and his computer teacher beat him for being noisy in class. The gym teacher beat him on the head. His computer teacher beat his legs. He had bruises on his thighs.” Naresh's mother expressed concern that her son's condition arose from a bodily problem, specifically a bout of typhoid four months prior. She said that typhoid had weakened her son and made his man2 (heart-mind) more sensitive. She then added that loss of his saato (soul or spirit) likely had played a major role, as well. He lost his soul when he went to the apartment of the neighbor who had committed suicide by hanging a few months earlier. The loss of his saato also made his man weak and caused him to have the visions of hanging corpses.

Naresh was uncertain about the cause of his affliction. He described his man as heavy, and said he would know he was recovered when his man felt light again.

Case two: Kalpana

Kalpana, aged 37, who lives several hundred kilometers outside of Kathmandu in a rural area, had fallen ill after her sister-in-law had died some years earlier. She had since visited literally dozens of healers, including lama and mata (traditional healers) who had given her multiple explanations for her illness, including witchcraft, the evil eye and various forms of laago (a range of supernatural forces including ghosts and spirits that befall individuals from outside the body). Her entire family had moved house at one point after it was suggested that her home had been cursed by a witch and was one cause for her illness. While these healers had offered her temporary relief from her problems, the distress always returned.

More recently, Kalpana had visited a local mission hospital and been given a diagnosis of nasaako rog (nerve disease) and was started on amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant. It was at this point when one of the authors first met her. Kalpana expressed that her man (heart-mind) felt heavy and reflected the hot, heavy weather of Chait (April-May); as the local expression goes, Chait laagyo, (the month of Chait has befallen her). The hospital doctor, however, explained that her symptoms, which included bad dreams, headaches, gyaastrik (gastric complaints), and various forms of body ache were a result of a disease of the nerves. “Like the wires in a radio, nerves pass to all areas of the body, and this was why,” the doctor explained, “she had so many pains.” He continued, “The medicine treated the nerve condition.”

Kalpana's husband adamantly denied that she had chinta (anxiety) or any mental health problem. He reassured her continuously that her illness was nerve disease. Despite the diagnosis, Kalpana continued to believe in the supernatural explanations. For example, she told one of the authors that she did not want others to know how much better she was feeling as “some are friends, some are enemies,” indicting that the glance and bad feelings of others could make her ill again. Kalpana was intimating witchcraft, although, like many, she did not name it as such.

As her symptoms improved, however, Kalpana increasingly placed all her hopes in the medicine and the doctors who had prescribed them.

Introduction

A common theme runs through Naresh's and Kalpana's stories. Both individuals and their families struggled to understand their illnesses within the context of divisions of the self—the mind, body, and soul. Ultimately, both rejected the notion that their illnesses were a result of an imbalance or dysfunction of the dimaag (brain-mind) in order to avoid the stigma of mental illness. In both narratives, family members emphasized bodily explanations of distress and avoided connections with mental and psychological processes.

In this paper, we discuss the relationship between mind–body divisions, mental health, and stigma in the context of Nepal. We illustrate that mind–body divisions are not only a feature of the western Cartesian dichotomy but may also be central to understandings of the self in non-Western settings. We demonstrate how everyday Nepali discourse on mind–body divisions offers a window into understanding social stigma against mental illness. We follow the cases of Naresh and Kaplana as they navigate mental healthcare with different healers reinforcing and reconstituting mind–body divisions with varying effects on stigma and seeking care. And finally, we describe two public health approaches in Nepal that redefine mental illness using local mind–body divisions to decrease stigma and increase acceptability of mental healthcare. Ultimately, we emphasize the importance of a medical anthropology of mind–body relations to understand stigma against mental illness and improve global mental healthcare.

Mind–body divisions in medical anthropology are theoretically worthwhile to understand the construction and deconstruction of self across cultural groups. Furthermore, they provide a window into the stigma of mental illness in cross-cultural settings. In their prolegomenon on the “mindful body,” Scheper-Hughes and Lock (1987) characterize Cartesian thought as based on a divide between mind and body. The mind–body distinction thus draws on a whole hierarchy of dichotomies derived from our enlightenment metaphysical inheritance: mind–body, culture–nature, emotion–rationality, tradition–modernity, etc. A growing body of literature highlights the implications of this division in the biomedical context. For example, Sinclair (1997) and Luhrmann (2000) discuss how Western psychiatrists are trained and operate in a healing profession where the body is perceived as real, but the mind, less so. There are powerful social and healing implications and a profound resultant stigma based on the division of “real” pain versus “less-than-real” pain. A person feels “real” pain when a cause is located in the body, and can be profoundly stigmatized when it is said to be “all in the mind” (Jackson 1994). Thus, the training of physicians positions psychiatry at the margins of healthcare (Kleinman 1988; Kleinman 1995; Sinclair 1997). Ultimately, sufferers of mental illness find the “reality” of their distress questioned, and they must incur the stigma of a social and clinical label of a mental or psychological problem versus a “true” physical disease.

Whereas the Cartesian mind–body division is given primacy in explaining health in studies of biomedicine in the West, it frequently has been implied that mind–body divisions are not present in non-Western medical systems, which are characterized as philosophical traditions that emphasize holism and complimentary duality (Scheper-Hughes and Lock 1987; Wen 1998). In literature on South Asia, authors have supported the claim of mind–body holism. The renowned Indian psychiatrist N. N. Wig (1999) suggests that the mind–body division is not important in non-Western thought. Regarding Nepal, researchers have written that, “psychiatrists report high levels of conversion disorders and hysteria, reflecting the absence of a cultural distinction between mind and body,” (Tausig and Subedi 1997). In explaining higher somatic presentations among anxiety patients in Kathmandu versus Boston, Hoge and colleagues (2006) have written that, “traditional medicine in many parts of Asia do not distinguish between mind and body, making distinctions in symptom type irrelevant and increasing the likelihood that individuals will manifest psychological distress with somatic symptomatology,” (p. 964).

Our clinical and anthropological experience in Nepal suggests, to the contrary, that mind–body divisions play an important role in diverse healthcare settings and contexts of social relations. Moreover, rather than the lack of mind–body divisions, it is the very presence of such divisions and the stigma tied to mental illness based on mind–body divisions that drives emphasis on bodily presentations of psychological distress. In a recent work on Hindu ascetics, Hausner (2007) similarly has questioned the tendency for South Asian scholarship to act as a theoretical counterpoint to the Cartesian split. She argues, to the contrary, that Hindu conceptions of body-soul dualism look very similar, and that this split is not the exclusive development of the west, arguing that “our fears of structuralism and Cartesianism may have eclipsed or precluded the cross-cultural uses of dualism as a model” (p 204). Below we explore evidence for the prominence of these mind–body divisions in indigenous Nepali ethnopsychologies, the impact of biomedicine on these divisions, and the role of mind–body divisions in the origin of and implications for mental illness stigma.

Methods

To address mind–body divisions, mental health, and stigma in Nepal, we reviewed existing ethnographic literature on construction of the self in relation to psychological wellbeing with the results presented in part one. For part two, we relied upon our ethnographic research conducted over the past two decades in Nepal. This ethnographic work has been primarily among Nepali-speaking populations in Kathmandu and the rural districts of Palpa, Kailali, and Jumla. We reviewed our ethnographic records and interview transcripts for references to mind–body differences, mental illness, and stigma against mental illness. Both authors also iteratively reflected on the terms generated more generally in conversations with a wide range of people in Nepal, checking our emergent understanding with native Nepali speakers.

For part three, we drew upon ethnographic research, participant observation, and interviews with traditional healers, general physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists. Both authors have studied traditional healers. One author originally worked as a physician in rural Nepal. The other author worked in the psychiatric department of a major hospital in Nepal. Both are trained in medical anthropology. Additionally, we employed cases studies and life histories of persons seeking services from different practitioners.

For part four, both authors partook in participant observation: one author with traditional healers and allopathic practitioners (1998-2000) and the other author with psychosocial organizations in Nepal (2005-2007). The traditional healer and allopathic research involved partaking in trainings of traditional healers by health organization, observing traditional and allopathic healings and encounters, as well as interviewing clients of traditional healers and allopathic practitioners (Harper 2003). The psychosocial section research involved partaking in psychosocial trainings, review of psychosocial manuals and reports for Nepali organizations, and interviews with psychosocial practitioners and clients (Kohrt 2006).

Human subjects’ approval and ethical review for the studies drawn upon in this paper were obtained from the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital-Nepal Institute of Medicine, Nepal Health Research Council, Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, University of Edinburgh, and Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Part one: Mind–Body Divisions in Anthropological Literature on Nepal

Anthropologists addressing conceptions of body, mind, and self in Nepal have focused primarily on Tibeto-Burman language-speaking groups with Buddhist and animistic traditions. Although these works have required book-length monographs to give a sense of conceptions of self and the associated “aesthetics of healing” (Desjarlais 1992; Hardman 2000; Maskarinec 1995; Nicoletti 2004; Nicoletti 2006), our review here must by necessity be brief, and, therefore, it will not do full justice to these authors.

The work of McHugh (1989; 2001) among the Gurung ethnic group of Nepal challenges the notion that Western conceptions of self are more individualistic while non-Western conceptions are more social. McHugh describes how notions of self are comprised of plah (souls) and sae (heart-mind) as well as the physical body. Fright dissociates the plah from the body making one susceptible to illness and eventually death. The sae is the seat of consciousness, memory, and desire. “The [sae (heart-mind)] brings feeling, memory, and thought together in the body. In this place at the center of the chest, life in the world penetrates and modifies the inner self” (McHugh 2001, p. 44-45). The size of the sae, she suggests, determines how engaged the individual is with society. Similarly, amongst the Yolmo, another Tibeto-Burman language speaking group, the concept of sem has many parallels to sae and other concepts of heart-mind (Desjarlais 2003). Among the Yolmo, Desjarlais suggests, madness occurs when the brain fails to control the sem (heart-mind). Everyone's sem is different, but the klad pa (brain) is the same; it stands above the sem (Desjarlais 1992, p. 57). Among the Yolmo, madness occurs from intense emotion and desire in the heart-mind with lack of adequate control of the feeling by the brain.

Among the Lohorung Rai ethnic group, individual behavior issues from desires and actions by ancestral spirits, the saya (soul), and the niwa (mind), among other forces (Hardman 2000). The niwa is in part responsible for keeping the saya high. When the niwa hurts, the saya falls (p. 258). If the saya falls, an individual has fatigue and depression. Nicoletti (2006) deals with the whole complex of mind–body amongst the Kulunge Rai of eastern Nepal. Among the Kulunge Rai ethnic group, the loss of souls also causes illness. There is the “vital force” of family members. This is present in humans from the moment of birth, and abandons them only at the moment of death. Similar to the saya among Gurungs, “[the vital force is] usually located in the head, the vital force is capable of movement. Unlike the souls, which can leave the body, the vital force can fluctuate only between the head and the coccyx,” (p. 59). “Melancholy, apathy, emotional fragility, depression are some of the typical outer signs” (p. 60) of a fall in this “vital force.” As Nicoletti states, this vital force represents a complex reality, involving body and health, relations with tradition and invisible forces, inter-personal relations, and personal dignity.

Among Newars, the historical inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley, there is also a complex division of the self into mind, body, and other components (Parish 1994). For Newars, the nuga is the seat of morality, desire, emotion, and thinking. Divinity and god dwell in the nuga (p. 190). The bibek filters the processing of the nuga before behavior is manifest. Bibek is an abstract entity encompassing the cognitive power to assure one acts responsibly (pp. 197-198). Parish's descriptions illustrate the significance of brain-mind and heart-mind in relation to the ijjat (social self and social status). Lajya is the construct used to characterize an individual's ability to filter their behaviors and maintain their ijjat (p. 199); it is the result of proper bibek functioning. Lajya can be glossed as social anxiety, embarrassment, or shame (cf. Shweder 1999). Individuals with insufficient lajya do not tailor their behavior to the social situation and do not act within the proper caste hierarchy. Individuals without lajya lose their ijjat resulting in loss of personal social status and the social status of the family. Parish describes an individual with tarnished ijjat who states, “I am equal to dead.” (p. 205). Later in the paper, we describe how mental illness can damage severely personal and family ijjat.

Part 2: The Language of Mind and Body in Nepal

In contrast to the ethnographies described above, we examine mind–body discussions in the Nepali language with the majority of examples taken from areas where Nepali is the mother tongue for a significant portion of the population (the Kathmandu Valley and the districts of Palpa, Kailali, and Jumla). We have chosen to examine Nepali, as opposed to languages of ethnic minority groups, because anthropologists have neglected mind–body divisions in the Nepali language, with the exception of Hausner (2007). This reflects the general trend in Nepal and Himalayan anthropology which has focused on tribal groups to the exclusion of caste-Hindu Nepali speaking groups (Holmberg 2006). Furthermore, the Nepali language provides the hegemonic force of socialization and modernization in Nepal. Teachers in government schools instruct in Nepali; political and government discourse occurs in Nepali; and, Nepali is the language for the majority of exchanges in healthcare settings. It is important to examine mind–body divisions in the language of these institutions and groups in power because of their influence and effect on the perpetuation of stigma. Despite differences in linguistic heritage, there is also considerable semantic overlap with a number of the terms from ethnic minority groups that we have presented earlier.

Our approach to discussing mind–body dichotomies is rooted in everyday Nepali language rather than the language employed by healers. Healing practitioners represent an esoteric and limited pool of knowledge within a cultural group. In contrast, daily language employing mind and body represents more general and widespread ethnophysiological knowledge. We follow the ideas of Lakoff and Johnson (2003), Martin (1994), and others in examining how body—and mind—metaphors are used in everyday language.

In the Nepali language and discourse, we identify five elements of the self that are central to understanding conceptions of mental health and psychological wellbeing, and subsequent stigma. These five elements are man (heart-mind), dimaag (brain-mind), jiu (the physical body), saato (spirit), and ijjat (social status).

1. Man

From Turner's A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language (Turner 1931), we find that man refers to “mind; opinion, intention; feelings; Man Garnu- to intend, take delight; desire; man gari – intentionally” (p. 491). Linguistically, in other Sanskrit-derived languages of Nepal, such as Chaudary, Tharu, Maithili, and Bhojpuri, man refers to the heart-mind as well (McHugh 1989). The concept is not confined to Nepal and found widely throughout South Asia and beyond. For example Ecks, from research conducted in West Bengal suggests: “Mon is the Bengali term for mind (or ‘heart–mind’), mood, affection, concentration, intention, and personal opinion. It is etymologically related to Sanskrit manas, Greek menos, Latin mens, and English mind,” (Ecks 2005, p. 247). Many common linguistic Nepali exchanges continue to reflect Turner's earlier work. Statements connoting wants, desires, likes, and dislikes invoke man. Man laagchha means to have the heart-mind struck by something, e.g. struck by the desire to eat. Man parchha means to have something placed on top of the heart-mind, which refers to desiring something. Table 1 provides examples of the use of man in everyday language and idioms related to emotional states and mental health.

Table 1. Use of man (heart-mind) in everyday Nepali discourse.

| Nepali | Literal Translation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Malaai jaana man laagchha. | For me, the heart-mind is struck by going. | I would like to go. |

| Malaai timi sanga kura garna man laagdaina. | For me, the heart-mind is not struck by talking with you. | I do not want to talk with you. |

| Tapaailaai football man parchha? | For you, is football on top of the heart-mind? | Do you like football? |

| Manmaa kura khelne | Words playing in the heart-mind | Worrying |

| Man dukkhyo | The heart-mind hurts | Sadness or suffering |

| Manko ghaau | Scar or sore of the heart-mind | Emotionally or psychologically traumatic memories |

| Manko kushi | Happiness of the heart-mind | Happiness or satisfaction |

From a health standpoint, interviews and ethnographic observation suggests that the man is not specifically associated with illness such as when an organ becomes diseased. However, if one is too emotional and there is too much activity in the heart-mind, this can lead to physical and psychological complaints. Based on our clinical experiences and other ethnographic observations, there is not a salient tie between social stigma and function or dysfunction of the man. As we describe below, the maintenance of social status is the responsibility of the dimaag, not the man.

2. Dimaag

Turner's dictionary (Turner 1931) suggests that dimaag may be derived from dimaak, meaning “pride, conceit” (p. 312). The dimaag performs different activities from the man, but the two elements work in coordination. The dimaag is the brain-mind or social-mind more than the organ encased in the skull, which is the gidi (physical anatomical brain). The dimaag is the processing of the gidi. The dimaag is the seat of thoughts as opposed to desires. The dimaag represents the socialized and logical decision-making mind. In addition, the man and dimaag have differing relations to the personal and collective. The man reflects personal workings and desires. In contrast, the dimaag acts in accordance with collectivity and social norms. A primary school teacher in Jumla explains,

“The man and the dimaag must work together. The dimaag is responsible for controlling behavior and thinking. If someone can't control his alcohol drinking, that is a dimaag problem. There are two types of dimaag problems that you can identify: first, someone who is very aggressive, and second, a person who doesn't talk to anyone else.”

Table 2 provides examples of the use of dimaag in everyday discourse. Interestingly, two phrases used to describe dimaag dysfunction employ English language terms ‘crack’ and ‘out’ even in rural parts of Nepal.

Table 2. Use of dimaag (brain-mind) in everyday Nepali discourse.

| Nepali | Literal Translation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Dimaag gayo | His/her brain-mind is gone | Not understanding; feeling confused |

| Dimaag khaaeko | His/her brain-mind has been eaten | Irritation, frustration, and inability to concentrate |

| Dimaag taataeyo | His/her brain-mind has been heated | Irritation and anger accompanied by a hot feeling in the head |

| Dimaag out bhayo | His/her brain-mind is not present or not working. | Short spell of irrational behavior |

| Dimaag thik chhaina | His/her brain-mind is not good or not okay | Person with a history of abnormal or antisocial behavior |

| Dimaag bigreko chha | His/her brain-mind is broken or not working properly | Crazy, mad, psychotic |

| Dimaag crack bhayo | His/her brain-mind is broken or not working properly | Crazy, mad, psychotic |

| Dimaag kharaab bhayo | His/her brain-mind is broken or ruined | Crazy, mad, psychotic |

Generally, these idioms refer to a state of madness, irrationality, and other unsocial behavior. These terms fall along a spectrum from temporarily irrational behavior to incurable madness/psychosis. “Dimaag gayo” (brain-mind is gone) refers to a transient state of not understanding or being confused. “Dimaag taataeyo” (brain-mind heated) refer to states that any individual can suffer from being annoyed and angered, usually from others' misbehavior. It also implies the physical sensation of the head feeling hot. When one can no longer focus on their work or make reasonable decisions, they are described as “dimaag khaaeko.” One respondent described this state arising from doing too much work, “Kaamle dimaag khaayo” (Work ate [my] brain), another from frustration with one's in-laws, “Bhaaujule mero dimaag khaayo” ([My] sister-in-law ate my brain).

“Dimaag out bhayo” connotes a temporary inability to control one's desires, such as suddenly running off with a woman or drinking alcohol excessively. A 12-year-old boy in a shelter for street children in Kathmandu had been beaten numerous times by policemen. He described, upon seeing policemen, “I can't control my urge to kill them. I will kill them. Dimaag out bhayo.” While this is a transient state with a generally well functioning dimaag, the phrase “dimaag thik chhaina” refers to individuals who frequently behave in socially unacceptable ways. A young woman in Jumla uses “dimaag thik chhaina” to describe her 13-year-old sister:

“My father always drinks [alcohol] then comes home and beats my mother and my sister. One time he beat my sister until she was unconscious. She was in the hospital for one week. Now, dimaag thik chhaina [her brain-mind is not okay]. She fights with others and shouts. She sits alone at home and doesn't go out to play with other girls.”

At the extreme of dimaag dysfunction is the state of being paagal (also baulaahaa) meaning crazy, mad, or, in medical terms, psychotic. Paagal is recognized as originating from dysfunction of the dimaag. Pach (Pach III 1998) has described how behaviors labeled as paagal are stigmatized resulting in economic and social marginalization. Having an individual who is paagal or with dimaag thik chhaina in the family prevents not only the sufferer from marrying, but also prevents other relatives from marrying. A saying recorded in Jumla illustrates this profound stigma: “Marnu bhandaa bahulaaune jaati.3 [It is better to be dead than crazy.]” Madness also can be viewed as contagious. One woman in Kathmandu described how she moved her children out of her house because she was concerned they would catch madness from their father, who suffered from schizophrenia. In addition, her husband could use only specific utensils for fear that if others touched them, they also would become paagal.

Many symptoms of mental illness are lumped under the label of paagal. A psychosocial counselor in Jumla explains, “If people become paagal (mad) they think it is maanasik rog (mental illness). If people have problems such as thinking a lot, unable to sleep, unable to concentrate, they think ‘maybe I am paagal now’.” She adds that paagal is seen as a problem of the dimaag, not the man. “When someone is paagal they think, ‘My dimaag is not at the right place. It has stopped working and will not function properly.’”

Similar to paagal are concepts of permanent dimaag dysfunction, such as the group of terms connoting “broken”: bigreko, khaarab, and ‘crack’. Nepali speakers view these states, like paagal, as incurable, permanent conditions. In Kailali district, a shopkeeper pointed to a man sitting in the dirt. He was wearing a soiled dress shirt and shorts. He was unshaven with clumps of dried mud in his disheveled hair. He spoke to himself and laughed spontaneously. The shopkeeper explains:

“His dimaag crack bhayo [His brain–mind is broken]. He was walking one day with his friend. Then the Maoists killed his friend right in front of him. From that day on, his dimaag crack bhayo. He wanders around the road. He sleeps on the road. He laughs for no reason. No one can talk to him. He used to be very intelligent and had a good education.”

The crux of our perspective on mind–body divisions, mental illness, and stigma lies in the unique position that dimaag holds in Nepali conceptions of self. Because of the centrality of social relations in status and perceived wellbeing, any dysfunction that impairs social positioning is strongly stigmatized. The dimaag, as opposed to the other elements of self, is principally responsible for this regulation.

Man and dimaag interaction

Although the man and dimaag function differently, the two are connected in their operation. Perturbed activity in either alters how the other functions. An Ayurvedic practitioner in Kailali explains: “Jasto dimaag garchha, tyastai man aauchha.” [The heart-mind feels whatever the brain-mind does.] He gives the example of controlling one's desires to keep the dimaag healthy:

“Desires must be controlled. If in your man you want a great deal of money, you will take a loan. Then you will have very big debts and your dimaag will stop working. So, we should always keep our man peaceful.”

Any strong emotion, for example anger or love, can override the seat of rational behavior and lead to the various forms of dimaag malfunction or paagal behavior. In popular songs, there are many examples of strong emotions, which originate in the man, overriding the seat of rationality and social control, particularly love. “Dil ki paagal hai” (My heart is crazy) was a popular Hindi movie a decade ago, and the theme of love overriding socially accepted normative behavior is one of the most common genres of popular movies.

Thus, one is not stigmatized for having socially inappropriate thoughts or desires in the man, rather one is stigmatized if the dimaag is not functioning properly to regulate these thoughts and desires.

3. Jiu

The physical body is a third element. Turner (1931) defines jiu as “life; body; person”; jiu ko refers to “bodily, physical,” (p. 216). Another term for the body is sarir, “body; figure” (p. 573). The jiu is the corporal body and is seen as the site of physical pain. Diseases and injuries damage this physical body. Physical suffering and pain can lead to worries in the man. However, the reverse pathway of the man affecting the jiu is less salient. Physical injury to the jiu can also damage the dimaag. In the case above of the young girl with an alcoholic father, the girl explained her sister's odd behavior of “dimaag thik chhaina” [brain-mind not functioning properly] was the outcome of physical abuse by the father.

Another linguistic category in daily life is angha betha. Turner defines angha as “limb; body; person; portion; ingredient” and betha as “disease; illness; trouble; misfortune.” A mata (traditional healer) in Palpa views angha betha as diseases of the body for which one should be referred to the local mission hospital. She distinguishes this from laago or laag, sickness caused by spirit possession, which is her province of treatment. This division between laago and angha betha is acknowledged widely in Palpa and significantly influences where the ill decide to go for treatment.

The jiu, unlike the dimaag, is not stigmatized in daily discourse. Individuals discuss physical suffering, including angha betha, in a manner that reflects its social acceptability.

4. Saato

Turner (1931) defines saato as “spirit; presence of mind; saato jaanu – the spirit to go; to be greatly frightened. From Sanskrit – sattvaam (n) – reality, consciousness” (p. 598). Maskarinec's (1995) more recent translation of saato refers to “wits; awareness.” The souls are the vitality of the body. The saato has some overlap with the aatmaa, which Turner defines as “self, soul; reasoning faculty, mind” (p. 34). Proper functioning of the jiu is tied intrinsically to the presence of the saato, which provides the energy and vitality of life. The saato also helps prevent supernatural forces from invading the body. One of the many explanations for Kalpana's condition was such witchcraft.

Fear disrupts and dislodges the saato. When individuals become afraid, the saato is shocked out of the body, known as saato gayo.4 Traditional healers in many districts of western Nepal describe how fear easily dislodges children's souls (cf. (Desjarlais 1992). In Palpa, this happened to one of the author's two-year-old daughter, who was startled by a cat one evening and withdrew into herself. A traditional healer pronounced that her saato was lost. Her saato was recalled by a local practitioner who chanted a mantra (magical incantation). Similarly, visiting the site of a suicide caused Naresh to lose his saato.

Once the saato is gone the body is more susceptible to witchcraft, one can become boksi laagyo (struck by a witch) or bhut laagyo (struck by a ghost). The loss of the soul makes the body vulnerable to physical illness. Children often have saato gayo, which results in, or occurs concurrently with, physical illnesses such as fever and diarrhea. A lama-jhankri (traditional healer), who also ran a small allopathic medicine shop, was observed concomitantly treating a child both with rehydration salts for diarrhea and calling her soul back with a mantra. Similarly, Naresh's mother interpreted her son's weakness in terms of lost saato. Among adults as well, shocks and fears, such as seeing violence, is thought to dislodge the soul and make one vulnerable to illness. With aging, individuals begin to lose their souls and thus lose their vitality, coming closer to death (cf. Desjarlais 2003).

In addition to providing vitality to the body, the soul is affected also by the dimaag. Individuals who have problems with the dimaag cannot control their fears and worries and are thus more susceptible to losing their saato. In the case of the Jumli girl described above, whose father physically abused her, the damage to her dimaag also made her more susceptible to soul loss. Her sister explains,

“After my father beat my sister, her dimaag was not right. She would lose her saato easily. As soon as our father would begin to beat our mother, my sister's saato would go. Before she was beaten and hospitalized, her dimaag was okay so she didn't lose her saato so easily.”

Loss of saato, like problems with jiu and man, is not as stigmatized in daily discourse as dimaag dysfunction is. Individuals and families can thus describe some symptoms of psychological distress, such as frightening easily or lack of energy, easy fatigability, etc., as lost saato instead of dimaag dysfunction, and thus incur less stigmatization.

5. Ijjat

Turner defines ijjat as “honor, reputation” (Turner 1931, p. 40). Ijjat is the link between the individual and the social world. Ijjat refers to social status. Ijjat paeko refers to receiving respect. The behavior of oneself and especially one's children in a manner congruent with caste hierarchy and social norms is crucial to maintaining ijjat. When a child acts in a socially unapproved way, such as marrying out of one's caste, then for the family and the individual there is a loss of social status; this is particularly salient for the behavior of women (cf. Liechty 1996; Parish 1994). In daily discourse, idioms for damage to one's social self include ijjat gayo (social status is gone), bejjat (social shame), and naak khatne (to cut one's nose). As we have explained above, the mind–body divisions in Nepali have an important social significance with the dimaag specifically responsible for assuring that the processing of the man is coherent with social norms to maintain ijjat. The consequence of a poorly functioning dimaag is social shame and loss of ijjat for the individual and his or her family.

To conclude our discussion of mind–body divisions in daily discourse, we suggest that the model of self in Nepali has different constituents, including man, dimaag, jiu, saato, and ijjat. Of these elements, damage to or an abnormal dimaag has the strongest association with stigma and loss of ijjat. There are less salient connections between man, jiu, saato and ijjat with regard to mental illness and stigma. Below, we describe how different healers reinforce and reconstitute the divisions.

Part 3: Navigating Diagnoses: Mind–Body Relations in Healing Contexts

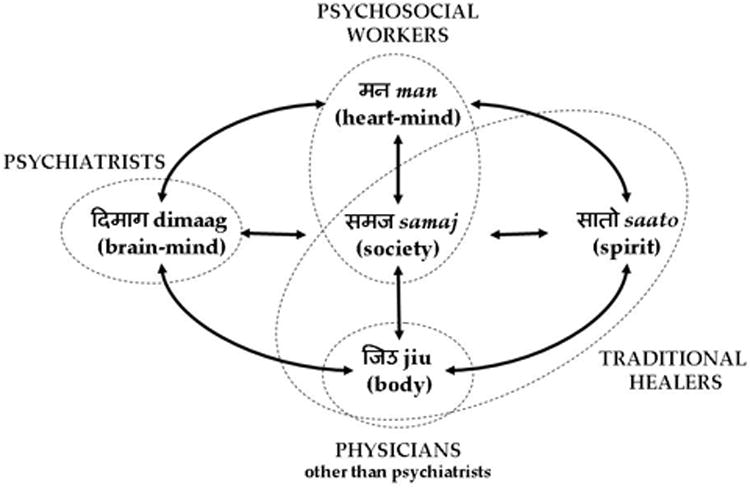

Although the general divisions of mind and body outlined above reflect public notions of what constitutes the self, the actual dividing lines and site of pathology are fluid. The divisions are context dependent, with different healers reinforcing or reconstituting the man, dimaag, jiu, saato, and ijjat in varied ways. It would be incorrect to say that there is a single Nepali ethnophysiology of these elements among Nepali speakers. Rather, interactions among healer, sufferer, and the sufferer's community shape these conceptualizations. Mind-body divisions and the stigma related to dysfunction of the dimaag influence people's decisions about which healers they seek for help and how they explain illness. Figure 1 illustrates a gross simplification of how healers reframe and explain suffering of their clients and their families, through the domains that healers differentially emphasize. For example, the same sufferer and his/her family may have their phenomenal distress framed by a “traditional healer” as a problem of the interrelationship between saato and jiu; while a psychiatrist may describe the suffering as a problem of the interrelationship between dimaag and jiu; and a general physician may interpret the same complaint through a focus on jiu alone.

Figure 1.

The framing of suffering by healers in Nepal through Mind–body relations.

Note: Solid arrows represent interrelations among the divisions of self. Dotted ellipses represent healing domains. For example, traditional healers often explain suffering in terms of saato, jiu and samaj (society), while psychiatrists reframe suffering according dimaag. We acknowledge that this schematic simplifies the divisions, but we do this for heuristic purposes to highlight how the primary domains of different healing disciplines reframe and reconstitute suffering. Also note that “traditional healers” encompasses a wide range of practitioners from varied ethnic and religious backgrounds and is overly simplistic; although using the category in this way orients us with medical discourse, we strategically do so for the purposes of this article.

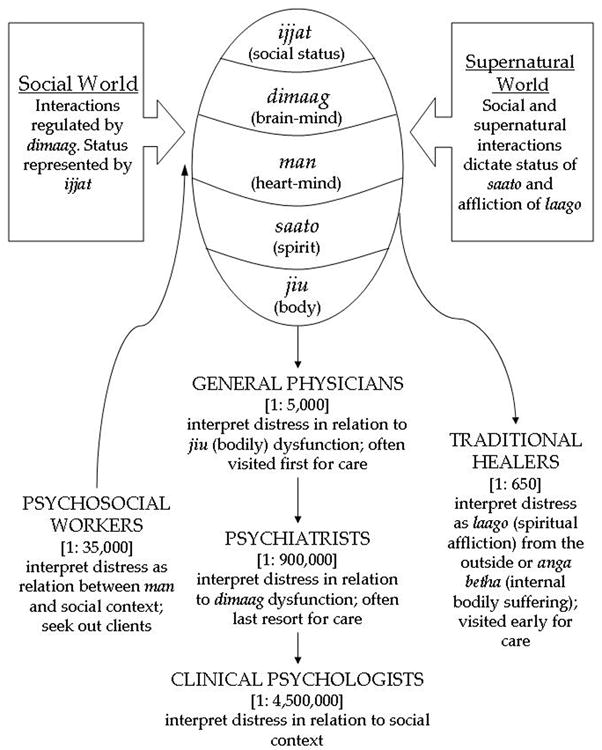

With the range of healers available in Nepal, individuals and their families generally navigate among diagnoses by visiting a number of healers to address mental health issues. As Naresh's and Kalpana's cases illustrate, it is not uncommon to visit traditional healers and general physicians simultaneously. For those with access, psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and psychosocial counselors are also referral points for mental health related care. Below we follow this navigation among diagnoses by describing how traditional healers, general physicians, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists frame mental illness (see Figure 2). The discussion of practitioners follows the hierarchy of resort for most Nepalis, i.e. traditional healers are the most prevalent practitioners (1 traditional healer per 650 persons), whereas clinical psychologists are fewest in number in the country (1 clinical psychologist per 4.5 million persons), (practitioner to population ratios based on the total population of Nepal were obtained from Kohrt 2006; Koirala 2001; Lamichanne 2007; Regmi, et al. 2004; World Health Organization 2001; and World Health Organization 2005). Thus, sufferers and their families are likely to call upon traditional healers early in the course of treatment whereas psychiatrists and psychologists are typically a final resort. However, this hierarchy of resort is dependent upon a range of issues, including class, caste and ethnicity, educational standing, economic status, etc.

Figure 2. Navigating Diagnoses: Pathways of helpseeking for psychological distress.

Note: Numbers in brackets represent the ratio of practitioners to population, e.g. there are 5000 people per physician in Nepal. Direction of arrows represents pathway of care, e.g. sufferers seek out traditional healers and physicians, whereas psychosocial workers seek out clients.

1. Traditional Healers

Kalpana's and Naresh's families were not exceptions to the practice of pursuing traditional healers early in the course of illness (see Figure 2). For Kalpana's family, witchcraft was one of the many explanations for her distress and led to her visiting many traditional healers. Similarly, upon a neighbor's suggestion, Naresh's mother took him to a traditional healer. The traditional healer explained his crying and abnormal visions as the loss of saato resulting from visiting the site of a suicide.

As Maskarinec (1995) has argued persuasively, following Levi-Strauss (1949), traditional healers provide a narrative structure through which the ill person comes to re-experience their symptoms, and mind and body, in particular ways. Traditional healers frame sickness, including physical and mental complaints, for the sufferer as the loss of vitality through the loss of the soul, most transparent in the label of saato gayo (soul loss).

Traditional healers have two central elements they use to address illness: the jiu and the saato. Angha betha afflicts the former and laago afflicts the latter. Traditional healers generally deal with laago and witchcraft – that is, with re-aligning the relations between both humans and the spirit world. Laago afflicts from the outside, and ghosts and spirits affect the sufferer in various ways. Laago is thus part of a landscape of affliction aligned with saato and loss of saato. Sufferers described the sensation of a recalled saato performed by traditional healers as relief of pain with momentary haluka (lightness of the heart-mind) (cf. Desjarlais 1992).

The construct of saato, and lost saato with invasion by supernatural forces through witchcraft, allows a way to discuss and treat psychological distress such as fear, low mood, fatigue, and nightmares. Granted, little is known of the efficacy of traditional healing in Nepal for psychological distress and mental illness. Ethnographic accounts of traditional practices in Nepal have described a range of emotional, psychological, and social responses that suggest the potential for alleviation of suffering (Desjarlais 1992; McHugh 2001; Peters 1981). This question of the efficacy of these practices is complex – the possible subject of another paper – and would need to address the “explanatory models” (Kleinman 1980; Weiss 1997) of varied groups in the healing process, and the interpretive positions and epistemologies of the healers themselves. Although traditional healers do not deal directly with restoring ijjat, by focusing on saato there is not the damage to ijjat as would happen with referring to dimaag. Moreover, traditional healers focus on social relations thus addressing ijjat indirectly.

Through Nepali indigenous divisions of mind–body, traditional healers provide a space for treating psychological distress. However, through both forces of modernity and its association with Cartesian divisions of mind–body, there are new layers of stigma placed upon traditional healing. At an ideological level, one key and overarching discourse is that development organizations, medical professionals, and the “educated” public frequently describe traditional healers as “backwards,” “superstitious,” or as “barriers” to seeking care; indeed, health workers may even view traditional healers as having mental illnesses. This stigma is evident from our experiences with Naresh and Kalpana. In the case of Naresh, despite numerous discussions in the hospital, the family did not disclose their visits to a traditional healer until we had a private meeting outside of the clinical setting. Similarly, Kalpana's husband was adamant about endorsing bodily explanations for Kalpana's distress rather than discussing witchcraft.

As part of modernization, the international development community has tried to reconstitute the role of traditional healers in the healing process as auxiliaries to biomedical care. One of the authors attended a non-governmental organization (NGO) healthcare training for traditional healers. This three-day training started as an attempt to re-orient the traditional healer's knowledge into the anatomical and physiological body; the ideological implications of this have been explored elsewhere (Harper and Maddox 2007). The idea was to get the healers to recognize the limits of their knowledge (to create “doubt” in their minds as one trainer phrased it), and for them to act as referral agents to health posts in the district. At a broader discursive level, this fed into ideas of modernity where many of these traditional healers were denigrated by the more educated as backwards and an impediment to development (Harper 2003; Ortner 1998).

Pigg has written extensively about the broader ideological and discursive dimension of emphasizing how “traditional healers” are the focus of development interventions (Pigg 1992; 1996; 1997; 1999). She argues that they occupy the space where policy and programs can be translated into practice. These “traditional healers” are treated generically in that they deal in health, so are like us but different enough to be the object of trainings and the objects of change (Pigg 1997).

We believe that this discursive marginalization of traditional healers has also been associated with a reinforcing of the marginalization of mental health. Whereas illnesses of the body require modern biomedical doctors, dhami-jhankri (traditional healers) are described as having therapeutic value for neurotic illnesses, as they allow the patient a spiritual construct to explain the symptoms (United Mission to Nepal 1998, p. 274). This logic links mental illness with superstition and “backward” forms of healing. Moreover, Cartesian biomedicine pathologizes traditional healing through labels of mental illness. Both psychologists and psychiatrists label traditional healers who arrive as their patients with International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) F44.3 “Trance and Possession Disorders” appearing under the Dissociative [Conversion] Disorders (WHO 2004). Psychiatrists typically medicate traditional healers with antipsychotics, and clinical psychologists help them relate their distress to social problems and stressors, and then teach the patient that psychological approaches can relieve stress.

Traditional healers are thus a part of the ideological space of development and progress, the overarching arena in Nepal where new identities and subjects are being forged; one leaves the past, and thus backwardness, behind to become modern, and thus educated and progressive. In doing so, this raises questions of the significance of saato in mental health and the future of traditional healing for mental health complaints. Because of development, modernization, and Cartesian hegemony, health seeking for both mental and physical distress from traditional healers is an environment of increasing stigma. This raises the question of whether an effective emotional, psychological, and social intervention will be lost to Nepalis if traditional healing becomes less available. This is not to deny that individuals and their families continue regularly to call upon the services of traditional healers to alleviate suffering.

2. General Physicians

Currently in Nepal, sufferers and their families visit general physicians (family physicians, pediatricians, and internists) after trying home remedies and self-medicating based on pharmacist recommendations (see Figure 2). Sufferers visit general physicians with the expectation of alleviating pain, typically conceived by sufferers as a malfunction of jiu, sarir, or angha (the body and its parts). Individuals present to physicians with bodily complaints, wounds, diarrhea, broken bones, etc. The doctor alleviates pain through the administration of medicine, particularly shots, which families and patients frequently perceive as stronger than pills (cf. Boker 1992). Families and patients generally do not disclose issues of the saato, man, and dimaag to general physicians; nor do physicians in our experience encourage such discussion.

General physicians typically do not represent a stigmatized space. On the contrary, physicians represent modernity. Furthermore, from the perspective of indigenous mind–body divisions, they treat a non-stigmatized part of the self, the jiu. The Cartesian dichotomy central to biomedicine reinforces the valorized space of the general physician; they address “real” physical problems, rather than problems of the mind. Thus, there is not damage to the ijjat by visiting a general physician. When physicians do encounter mental illness, they may provide treatment without naming it as so. One physician explained his reluctance to tell patients and their families that they have a “mental disease” such as depression. Although he identifies depression and prescribes anti-depressants, he does not tell patients the diagnosis because the families “think the worst.” Husbands consider abandoning their spouses. When the patient hears, “mental disease”, they “see it as the end of the world,” the physician explained. Ecks (2008) describes a similar issue in Kolkata, West Bengal.

The focus on physical complaints also can lead to a reconstituting of complaints in terms of the body to the neglect of issues of the man, dimaag, saato, and social world. This is particularly the case with “idioms of distress” (Nichter 1981) such as gyaastrik (gastric complaints) (See Ecks (2004; 2005) for examples from West Bengal) and jhamjham (parasthesia) (Kohrt and Schreiber 1999; Kohrt, et al. 2005; Kohrt, et al. 2007). In both urban and rural areas of Nepal, gyaastrik has emerged as a common idiom of disease. As many people reckon that recovering from gyaastrik requires a life long change in diet and typically is resistant to treatment, it is a particularly feared problem. Doctors in the Palpa mission hospital and other local clinics were commonly misdiagnosing this as gastritis. Even treatment failures were explained with an emphasis exclusively on the body. One surgeon in the Palpa mission hospital claims that gyaastrik persists because of failure to treat the disease correctly with pharmacological “triple therapy” protocols (an antibiotic, a proton-pump inhibitor, and a histamine blocker). Here we see a complaint being viewed exclusively in the physical arena to the neglect of other elements of ethnophysiology.

A woman with similar problems to Kalpana revealed that she had had no less than four gastroscopies in a number of hospitals across Nepal after complaints of gyaastrik. All of them came out normal. She was considering having a fifth, despite attempts to persuade her that this was unnecessary. The slippage of the term gyaastrik used in common Nepali parlance throughout much of Nepal, to the medical term “gastritis,” may be one issue in the persistent medical misunderstanding of this problem. Yet, it is partly an understanding that the hospital is the space where such physical problems are presented, combined with the stigma of being labeled with a “mental” problem that compounds the issue. The case of Naresh illustrates how the family first pursued the physical gastrointestinal complaints, and only later pursued treatment from “traditional” healers and mental health workers for potential problems in the saato and dimaag, respectively.

It is important to note here how biomedicine and its Cartesian thinking are overlaying its stigma on the preformed mind–body divisions and its concomitant stigmas. Ultimately, general physicians, biomedicine, and Cartesian dichotomies give supremacy to the jiu and potentially add stigma to the dimaag on top of the existing marginalization built into indigenous mind–body divisions.

3. Psychiatrists

As of 2004, there were only 30 psychiatrists in Nepal, and most of them were in Kathmandu (Regmi, et al. 2004); current estimates are 40 psychiatrists in the country, still concentrated in Kathmandu. However, even in an increasingly cosmopolitan capital, urban patients rarely visit psychiatrists first, except in cases of psychosis among educated families. Usually, before seeing a psychiatrist, individuals visit general physicians and traditional healers, with the former providing a referral to the psychiatrist (see Figure 2). General physicians refer to a psychiatrist when a patient does not improve even after repeated treatments, or when patients exhibit psychotic behavior. This is a last resort because through the referral, the general physician is placing a tremendous burden of stigma on the patient and her family. From our clinical and ethnographic work, we have met many families who describe the tremendous loss of ijjat in bringing a family member to see a psychiatrist. Families bringing patients to the mental hospital often register the patient under false names, which later creates problems for continuity of care and follow-up. Families with more economic means will take patients to India for psychiatric treatment to minimize public exposure.

This stigma against psychiatry is rooted in the daily discourse of mind–body divisions that identify dysfunction of the dimaag as socially threatening and damaging. For Naresh's family, hearing that his condition was not a mental illness was a tremendous relief. The treatment and psychological counseling recommended by the psychiatrists was secondary, if not entirely insignificant, in light of hearing that Naresh's dimaag was normal.

The public and other physicians stigmatize psychiatrists because they deal with this “incurable” and “socially dangerous” health issue of dimaag thik chhaina. Many people refer to psychiatrists as “crazy doctors” and the one mental hospital in the country as “crazy prison.” A hospital administrator in Kathmandu describes that the psychiatrist in his hospital is a “neuro”-psychiatrist; he explains, “It is worse to be a baulaahaa (crazy) doctor [a psychiatrist], than to be baulaahaa [a crazy person]” and that this was why we should refer to one with the prefix “neuro-.” One physician explains his decision not to study psychiatry despite his interest in the subject: “For families, it is a bigger shame to have a child who is a psychiatrist than to have a child who is not a doctor at all.”

One of the ways that psychiatrists deal with the stigma is to locate the pathology in the body. This is rooted in clinical training that emphasizes pharmacological rather than psychotherapeutic treatment (for accounts in Western settings see Luhrmann (2000)). One psychiatrist describes mental health as a problem of biology and emphasizes the importance of the electroencephalogram (EEG) for both its biological diagnostic acumen and its symbolic importance for giving psychiatrists status among other physicians. He was amused when interviewed, indicating that while the social issues on which we focused were interesting, they were secondary to the reality of mental illness causation, which remained firmly embodied in the chemical make up of, and other organic dysfunction of, the brain.

4. Clinical Psychology

Clinical psychology is a new and emerging field in Nepal. Naresh is one of the few people in the country who has seen a clinical psychologist. In 2004 there were five clinical psychologists in the country, only one of whom trained in Nepal (Regmi, et al. 2004). The country's leading teaching hospital began training clinical psychologists through an M. Phil. curriculum less than a decade ago. Clinical psychologists focus on neuropsychological testing and behavioral therapy. Psychiatrists refer cases to the clinical psychologist when they feel that the patient is not appropriate for pharmacotherapy or would not improve on pharmacotherapy alone (see Figure 2).

One clinical psychologist describes a tension between psychiatric and psychological intervention because patients arrive already with a diagnosis and a way of thinking about their illness crafted by the psychiatrists. The clinical psychologists try to encourage patients to think about their social situation, but this can produce a double stigma. The first stigma is the label of mental illness and the second arises from describing the social problem, which is also socially damaging, such as alcoholism, domestic violence, sexual violence, etc. Psychoeducation is seen as central to treatment. The psychologist thus steers patients to relate problems to causes; if they can grasp the links, then they become more open. If not, they leave. Many just ask for medication. They do not believe the talking helps at all. These issues were illustrated by Naresh and his family who thought that since no medicines were given by the psychologist, they would not need any more treatment. Kalpana had no such access to clinical psychologists.

Clinical psychology also reinforces the backward–modern dichotomy in psychological wellbeing. A psychologist explained that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for depressed patients needs to address their cognitive distortions and negative thoughts, but if someone says her suffering is from witchcraft, they are not reflexively modern enough for psychologists to help them. If the patient says it is witchcraft, the clinician may label the patient as psychotic. The family interprets this as being paagal (crazy), having a dimaag dysfunction, and ultimately losing ijjat.

In addition to clinical psychologists, psychosocial counsellors also are available for treatment as a part of the growing field of paraprofessional psychosocial workers (see Figure 2). In the next section, we will discuss psychosocial counselling within the framework of public health movements and stigma reduction.

Part 4: Reconstituting local mind–body divisions to reduce mental illness stigma and promote mental health service use

In Nepal, several organizations have creatively applied local mind–body relations in public health approaches that attempt to reduce the stigma of mental illness and promote use of mental healthcare services. Below, we describe two such public health approaches. In the first, mental illness is reinterpreted as nasaako rog (nerve disease), which is a condition of the body rather than the mind. In the second program, psychological distress is framed as manosamajik samasya (psychosocial problems), wherein the pathology is located between the man and society, rather than a dysfunction of the dimaag. We discuss the advances made by such programs, while also commenting on the limitations of such approaches.

The nasaako rog (nerve disease) approach

In the mid 1990s, expatriate physicians at a mission hospital in Palpa district developed mental health guidelines to translate psychological distress into a physical health model. The United Mission to Nepal5, which ran the hospital (Harper forthcoming), worked toward a redefinition of mental illness. Their nasaako rog approach focused on making psychiatric morbidity less stigmatizing and more socially acceptable by introducing the concept of “nerve disease” (United Mission to Nepal 1998, p. 272ff). A change in terminology was hoped to produce a change in social significance. Nasaa (in Turner's dictionary naso is defined as “nerve, vein, sinew,” p. 370) are the cords and tubes of the body, most commonly “nerve” in everyday discourse. Nasaa connect the dimaag to the rest of the body.

The guidelines for mental healthcare at the mission hospital first provide a brief exposition on the mind–body continuum. The advice in the guidelines is for practitioners to acknowledges the physical symptoms as real and explain them with a physical model that has meaning for the patient (United Mission to Nepal 1998, p. 272ff). In the protocols for treating nasaako rog (nerve disease), which were to be used by doctors and health workers, the list of common symptoms for the diagnosis of depression starts with the physical complaints, then moves onto a list of “unpleasant feelings” including not sleeping well, having a poor appetite, feeling tired, wanting to cry, feeling a loss of energy, having unpleasant dreams, feeling afraid for no reason, wanting to be alone, feeling angry, and losing enthusiasm for life. A list of triggers that may lead to the start of the nerve disease include the following: the death of a loved one; being given more responsibility than one can handle; fear of failing an exam; coping with a new marriage; going to live with a new husband and new mother-in-law and losing friends and family; a physical illness which takes time to get better; coping with an alcoholic; loneliness; lack of love, happiness or a good relationship.

The impact of this approach was experienced by Kalpana. She was coming to re-experience her condition not as witchcraft, but as a problem of the nerves, one treatable as a condition of the body with medication (a tricyclic anti-depressant). Reframing mental illness as nasaako rog is an example of linguistic and conceptual reframing to avoid the stigma placed upon dimaag and maanasik rog (mental illness). In addition, it was designed consciously to decrease dependence on dhami-jhankris. Missionary intervention has the added ideological imperative of perceiving these practitioners as “witchdoctors”, or evil, an added overlay of this specifically Christian form of modernity. It is important to note that there also may be influences relating to historic roots of soul–body divisions in Christianity originating in Pauline interpretations of the bodily resurrection (Bynum 1995; Lindland 2005) that influence the mission's physicians practice. However, as we did not discuss this with mission physicians, it is not addressed here.

However, one of the pitfalls of the programs such as this approach to nasaako rog, which rely upon changes in terminology, is that, without proper education, purely relocating and renaming mental illness may just open up new spaces for stigma. One must be cautious that new terms do not become new spaces for stigma to re-manifest itself. For example, without public health awareness campaigns, there is the threat that nasaako rog could become stigmatized as is dimaag dysfunction. Furthermore, the reification of nasaako rog will contribute to mental healthcare that relies predominantly on psychopharmacology to the exclusion of social and psychological supports. Finally, this approach to nasaako rog specifically targets reduction of reliance on traditional healers, which is an important form of social healing.

Psychosocial Programs

Manosamajik karyakram (psychosocial programs), as practiced in Nepal, represent another reconstituting of the mind–body division. Manosamajik is a neologism combining man (heart-mind) and samaj (society) referring to the connection between psychological and social processes. “Psychosocial” is a popular international movement in the humanitarian field that focuses on the interaction between social and psychological factors:

The term ‘psychosocial’ is used to emphasize the close connection between psychological aspects of our experience (our thoughts, emotions and behavior) and our wider social experience (our relationships, traditions and culture). The two aspects are so closely inter-twined in the context of complex emergencies that the concept of ‘psychosocial wellbeing’ is probably more useful for humanitarian agencies than narrower concepts such as ‘mental health’. (Psychosocial Working Group 2003)

In the wake of an eleven-year war between the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoists and the security forces of the Government of Nepal, NGOs in Nepal are echoing the international trend and pursuing a community psychosocial approach. In Nepal, psychosocial practitioners include community psychosocial workers (CPSWs), who have completed short courses of one to two weeks and act in various roles within NGOs, and community psychosocial counselors, who have completed four to six month courses in basic counseling skills. In the last few years alone, NGOs have produced 500-750 psychosocial workers, the vast majority of whom have completed short courses such as the CPSW training (Kohrt 2006; Lamichanne 2007). The most extensive training program involves a six-month course on basic counseling skills for para-professional psychosocial counselors (Jordans, et al. 2002; Jordans, et al. 2003a; Jordans, et al. 2003b; Jordans and Sharma 2004).

In Nepal, one of the central features of psychosocial trainings and interventions is distinguishing manosamajik samasyaa (psychosocial problems) from maanasik rog (mental illness). As the above quote from The Psychosocial Working Group illustrates, the international division between psychosocial and mental health is that the former involves the interconnection between psychological and social experience. However, in Nepal, one of the primary differences between psychosocial and mental is the location of pathology and the relationship to stigma. For example, one counselor explains:

“People view manosamajik samasyaa (psychosocial problems) as maanasik rog (mental illness) so they feel very ashamed to come forward. They think that if they tell anyone about their problem they will be stigmatized… they will be sent out of the village… so we explain to them that what they have is not a maanasik rog.”

The redefining of mental as psychosocial occurs through relocating pathological distress in the man rather than in the dimaag. The four key elements that psychosocial counselors claim to address are man, jiu, behavior, and relations with other people. These individuals are referred to as manobimarshakarta (person who advises on matters of the heart-mind). Psychosocial counselors emphasize the relationship between the man and society or social relations; they do not explain problems in terms of dimaag dysfunction. A psychosocial counselor exposed the challenge of reconstituting psychological complaints as psychosocial problems rather than mental illness symptoms:

“Paagal (madness or psychosis) is a problem of the dimaag. Chinta (worries or anxiety) is also perceived as a dimaag problem. People with these problems don't think they have problems with their man. They go to the doctor if they have a dimaag problem, but they wouldn't go for a man problem. We have a difficult time explaining to people what a counselor does and that we are trying to help their man.”

Whereas psychiatrists explain physical symptoms associated with psychiatric disease in terms of dimaag, psychosocial counselors explain the connection in terms of man. A psychosocial counselor explains how she struggles with psychoeducation to teach patients the relation between emotions and somatic complaints:

“We try to give a clear picture explaining that when you think a lot, your man gets affected, then your body gets affected and you have a headache and stomachache. Then your relations with other people get affected so that you get irritated when other people talk, or you just want to sit alone.”

For Nepali psychosocial counselors, the pathogenic agent from the psychosocial framework is society and the environment. Psychosocial counselors consider clients to have psychological and emotional problems because of their lifestyle and the people around them. This approach avoids the stigma associated with discussing mental illness and dimaag by discussing symptoms in terms of man. In a study of perceptions of counseling in Nepal, Jordans and colleagues (Jordans, et al. 2007) found that 92% of beneficiaries reported that the counseling service was appropriate culturally and that stigma was not a problem related to service use. This supports the viewpoint that visiting a community counselor is not stigmatized in the same manner as visiting a psychiatrist.

Currently, few people are seeking out psychosocial care as they would a doctor or traditional healer; instead psychosocial programs identify people in need of care through community awareness programs and screening children in schools (Kohrt 2006). Ultimately, psychosocial programming, like the nerve disease approach, provides a space for treatment of psychological distress and mental health in a manner that is less damaging to ijjat (social status), and thus promotes service use and compliance to treatment.

The potential limitations, however, of the implementation of psychosocial approaches in Nepal are fourfold. The first issue is the pitfall of re-labeling, as described above with reference to nasaako rog, wherein new terminology may become stigmatized in the same manner as dimaag dysfunction. With the spread of ‘psychosocial’ as a term referring to many problems previously classified as dimaag dysfunction, there is the risk that people labeled with ‘psychosocial’ problems also will be stigmatized. The second potential limitation is that ‘psychosocial’ is not taken up as a category necessitating intervention and support. This is illustrated by Naresh's case. When the family was told that Naresh had a problem with his man—but his dimaag was fine—this was interpreted by the family as an indication that he did not need professional care and thus the family did not return for additional counseling. The third potential limitation is the converse of a problem with the nasaako rog campaign. Wherein the “nerve disease” approach may lead to over reliance on psychopharmacology, the ‘psychosocial’ approach may be a barrier to mental healthcare in a medical setting. For example, the main recommendation of counseling beneficiaries in the study described above was the need for medication to be provided along with counseling (Jordans, et al. 2007). The final limitation is the lack of consensus in the definition of ‘psychosocial’. For example, whereas The Psychosocial Working Group emphasizes the mutual relationship between psychological and social, most psychosocial workers in Nepal described it as a one-way street in which social problems cause psychological difficulties. This latter approach ignores the multiple and complex pathways that contribute to psychological difficulties and the impact that psychological problems have on social processes and institutions. Moreover, the unidirectional interpretation obscures the issue that stigma arises at the interaction of social and psychological processes, rather than being simply a result of social processes.

Conclusion

Addressing the social stigma of mental illness in Nepal requires an understanding of local mind–body divisions. The dimaag (brain-mind) is the organ of socialization and social control. The public perceives individuals who lack socially appropriate behavior as deficient in their dimaag activity. Thus, dimaag dysfunction is tied directly to loss of ijjat (social honor) because the dysfunction represents an inability to abide by social norms. The exposition of mind–body discourses reveals the multiple dynamic ways in which sufferers and their families can interpret mental health distress. Help-seekers navigate among diagnoses constantly seeking a context that best fits their subjective experience of distress and the social world in which that is lived.

Our interpretation argues that the stigmatization of behaviors attributed to the mind predates the introduction of biomedicine and Cartesian duality in Nepal. The stigmatization appears to be rooted in concepts of the social implication of these behaviors: violation of social norms, especially caste hierarchy and gendered interactions. The perception of these defects as incurable further fuels the stigma, contributing to a fusion of illness with identity. This suggests, in broad strokes, that many of the fundamental features related to stigma against behaviors related to dimaag dysfunction in Nepal correspond to similar roots of stigma against mental illness in the West (Estroff 1981; Fink and Tasman 1992; Goffman 1963). However, the ethnopsychology of mind–body divisions explaining mental illness, the specific social violations most admonished, and specific pattern of ripple effects upon family are influenced strongly by Nepali cultures. Ultimately, there may be enough overlap between the “stigma systems” that the discrimination against mental illness in Cartesian biomedicine resonates with and augments the indigenous framework already marginalizing the mentally ill in Nepal.

Regarding future directions, it is important for medical anthropologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists to continue exploring mind–body divisions in non-Western settings. Studies of ethnophysiology in other cultures also have suggested complex frameworks for understanding bodily processes. Fox (2003) describes the divisions among heart, mind, and brain in Mandinka nosology. Based on her study of Naikan in Japan, Ozawa-de Silva (2006) describes how mind and body are seen as unified in health but can be separate sites of pathology. In addition, Hinton and Hinton (2002) discuss the process by which the ‘seven bodies’ of panic draw upon metaphor, the natural landscape, and sensation itself among Cambodian refugees. Furthermore, medical anthropologists and psychiatrists should look at the intersection and translations of indigenous mind–body relations and Cartesian divisions brought in through biomedicine, education, and other processes of modernity. Such intersections and translations may inadvertently exacerbate stigma and create obstacles to care for mental illness.

Finally, it is helpful to reflect again on the cases of Naresh and Kalpana. For Naresh's family, avoiding references to dimaag and mental illness was one of their most pressing concerns. After visiting an array of health professionals, the family was most comfortable referring to his distress in bodily terms, with his mother also invoking loss of saato. Furthermore, although the family was relieved that Naresh did not have a dimaag problem, they did not comprehend the relevance of the clinical psychologists and a “talking cure.” As we described, the man is not conceived as an organ of pathology which can be diseased or needs to be cured. Instead, the man registers when one is healthy or ill based on its lightness or heaviness. This highlights one of the limitations of the psychosocial endeavor, which focuses on man rather than dimaag. Because man is not seen as an organ susceptible to pathology, the family did not pursue further counseling for Naresh. The physicians who could alleviate Naresh's bodily pain and the traditional healer who recalled Naresh's soul were congruous with their understandings of pathology and suffering in relation to the jiu (body) and saato (spirit). Ultimately, both Naresh's and his family's ijjat (social status) were at stake in terms of the choice of care sought, the diagnoses they received, and the models they then endorsed. And, although ijjat was maintained, the lack of continued counseling raises concerns about his mental health recovery.

For Kalpana and her family, the explanation of her depressive and physical symptoms as nasaako rog (nerve disease) was congruent with her understanding of suffering as potentially originating from the body. The medical treatment was a salient healing based on bodily dysfunction and one in which she invested her hopes for palliation of distress. Like Naresh's, Kalpana's visits to doctors reframed idioms of distress, particularly abdominal complaints, as biological pathology. But, in neither case did the person improve with biomedical gastrointestinal treatments. Kalpana's husband, like Naresh's family, was adamant that the psychological and emotional complaints were not mental illness. The nasaako rog approach allowed Kalpana's husband to view the distress as bodily nerve pathology. Ultimately, Kalpana now is relying primarily upon the psychiatric medicines for her healing. The interpretation of psychiatric distress as a bodily dysfunction in the form of nasaako rog may contribute to an over-reliance on these medications without the compliment of social and psychological supports to promote mental health. For example, the bodily focus does not emphasize the need for exploring broader family and social relations in Kalpana's life, even as she defines some of these through local idioms of witchcraft.

Public health workers should utilize knowledge about the interaction between mind–body divisions, mental illness, and stigma to develop creative health campaigns to reduce stigma and promote service use. However, simply renaming mental illness may create new spaces for stigmatization. What will be the public perception of nasaako rog and manosamajik samasya a decade from now in Nepal? Will the public stigmatize these terms to the same degree as dimaag dysfunction? Furthermore, renaming can change the health-seeking in both positive and negative directions. For example, the nasaako rog focus may promote psychopharmacology to the exclusion of social and psychological healing. The psychosocial focus on man may contribute to decreased help seeking if family members dismiss man-related distress as an arena to be addressed personally rather than something aided by seeking help. Medical anthropologists can be instrumental in providing the foundational knowledge for public mental health programs to target stigma. Medical anthropologists can work to identify the roots of why mental illness is stigmatized by calling upon studies of language, ethnopsychology and ethnopsychiatry, and other ethnographic tools. From this information, we can advance the scientific study of stigma (Keusch, et al. 2006) and work toward global health programs that address not only the symptoms but also the stigma of mental illness.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this paper were presented at CNAS seminar of Tribhuvan University and at SAHI seminar of the University of Edinburgh. We thank the participants of these seminars as well as Peter Brown, Christina Chan, Mark Jordans, Sara Shneiderman, Wietse Tol, Lotje van Leeuwen, and Carol Worthman for their contributions to this manuscript. The first author was funded by NIMH National Research Service Award, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and Emory University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. The second author was funded by the Economic Social Research Council (ESRC).

Footnotes