Abstract

The immune system is comprised of several CD4+ T regulatory (Treg) cell types, of which two, the Foxp3+ Treg and T regulatory type 1 (Tr1) cells, have frequently been associated with transplant tolerance. However, whether and how these two Treg-cell types synergize to promote allograft tolerance remains unknown. We previously developed a mouse model of allogeneic transplantation in which a specific immunomodulatory treatment leads to transplant tolerance through both Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells. Here, we show that Foxp3+ Treg cells exert their regulatory function within the allograft and initiate engraftment locally and in a non-antigen (Ag) specific manner. Whereas CD4+ CD25− T cells, which contain Tr1 cells, act from the spleen and are key to the maintenance of long-term tolerance. Importantly, the role of Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells is not redundant once they are simultaneously expanded/induced in the same host. Moreover, our data show that long-term tolerance induced by Foxp3+ Treg-cell transfer is sustained by splenic Tr1 cells and functionally moves from the allograft to the spleen.

Keywords: Graft, spleen, T regulatory cells, transplant tolerance

Introduction

In the last decade, various types of CD4+ T regulatory (Treg) cells have been described (1). The existence of such a Treg cell arsenal suggests that a “finely-tuned collaboration” occurs to control immune responsiveness (2,3). However, the exact roles of the various types of Treg cells and how they interact to help maintain the balance between immunity and tolerance remain unclear.

The induction or maintenance of tolerance in mice and humans has often been associated with CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ (Foxp3+) Treg cells or T regulatory type 1 (Tr1) cells (reviewed in Ref. (4)). Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells are considered to be two distinct types of regulatory cells. The Foxp3+ Treg cells (i) are generated in the thymus but can also be induced in the periphery; (ii) their antigen specificity is still a matter of debate especially in humans; and (iii) suppress in vitro mainly via cell–cell contact, whereas in vivo they do so via several additional mechanisms (reviewed in Refs. (5,6)). Conversely, Tr1 cells (i) do not constitutively express Foxp3 and are characterized by the production of high levels of IL-10 in the absence of IL-4; (ii) are induced in the periphery in an antigen-dependent manner in the presence of IL-10 or IL-27; and (iii) are known to be predominantly IL-10 dependent with regard to their suppressive capacity (reviewed in Refs. (7,8)).

Previously, we demonstrated that Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells can co-exist in vivo in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes in which tolerance to endogenous pancreatic islets was induced by treatment with rapamycin + IL− 10 (9). Moreover, these two types of Treg cells co-localize in the small intestine of anti-CD3 treated mice, where each one was sufficient to control colitogenic Th17 cells (10). In line with this, we recently observed that in a mouse model of induced-tolerance following pancreatic islet transplantation, Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells co-exist but, differently from the aforementioned observations in anti-CD3 treated mice, they accumulate in different organs at variant times. Of note, Foxp3+ Treg cells accumulate in the allograft early after transplantation and then return to their physiological levels, while Tr1 cells increase in the spleen early, but are also maintained long term. In line with this we observed that depletion of CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells does not break the state of long-term tolerance, which is, on the contrary, IL-10 dependent (11). These data suggest that these two types of Treg cells might have a different function over time but this concept remains to be verified.

Another important matter of debate is in which tissue the respective regulatory activities of Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells occur. The sequential migration from the blood to the graft and ultimately to the draining lymph nodes has been elegantly shown to be required for Foxp3+ Treg cells to block islet allograft rejection (12). Conversely, Tr1 cells preferentially localize in the spleen in various animal models of tolerance (9,13). However, the notion of whether the spleen is the key organ for Tr1-cell regulatory activity and whether the distinct in vivo localization of Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells corresponds to a different function remains unknown.

To address these questions we took advantage of our recently developed mouse model of induced tolerance to allogeneic transplantation in which Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells are present and localize to different organs (11). We now show that transplant tolerance is initiated by Foxp3+ Treg cells that function locally within the graft in a non-antigen (Ag) specific manner while it is maintained by CD4+CD25− Tr1 cells that act from the spleen.

Materials and Methods

Islet transplant

Pancreatic islet transplant was performed under the kidney capsule as previously described (9). The transplanted mice that did not reject the graft 100 days after transplantation were challenged in vivo with splenocytes of the donor. A total of 30 × 106 splenocytes isolated from the original islet donors were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.), and blood glucose levels were monitored daily thereafter. Mice still normoglycemic 30–50 days after challenging were considered long-term tolerant. The doses of anti-IL-10R, PC61 mAbs, and P60 were chosen in accordance with to the literature (14– 16). Some mice underwent kidney removal 100 days following transplantation. These animals were anesthetized and the renal artery and vein were clamped and cauterized.

Treatment of 2TT mice

Transplanted mice were treated with anti-CD45RB mAb (MB23G2 clone from ATCC), rapamycin (Rapamune; Wyeth Europe, Taplow, UK)and r-hu-IL-10 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Anti-CD45RB mAb was injected i.v at days 0, 1, and 5 after transplantation at 100 µg per dose. Rapamycin was diluted in water and administered by gavage for 30 consecutive days once a day at 1 mg/kg. Recombinant hu-IL-10 was diluted in PBS and administered i.p. twice a day for 30 consecutive days at 0.05 µg/kg.

Cell isolation and adoptive transfer experiments

One-to-two million of magnetically purified cells were suspended in 200 µL PBS and injected i.v. into diabetic recipient mice 1 day prior to islet transplant. When indicated, CD45+ CD4+ Foxp3GFP+ T cells were FACS sorted with a FACSVantage (BD Bioscience). The cells isolated were suspended in 200 µL PBS and injected i.v. in diabetic recipient mice 1 day before undergoing islet transplant. Alternatively, all the graft-infiltrating cells were co-transplanted with the isolated islets under the kidney capsule of recipient diabetic mice (i.e. local transfer).

Cell staining and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Surface cell staining was performed with anti-CD45 PercP, anti-CD3 APC, anti-CD4 Pacific Blue, anti-CD25 APC or PeCy7, and anti-CD8 PE mAbs (all from BD Pharmingen). CD45RB expression was tested with the anti-CD45RB PE mAb (clone 16A from BD Pharmingen), which had been previously demonstrated to bind to an epitope different than that bound by the MB23G2 mAb (17). Foxp3 expression was tested with the Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA; clone FjK-16s).

Intracellular staining and ELISA were performed as previously described (18). Cells were acquired on a FACSCanto (BD Bioscience) and analyzed with FCS express V3 (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA).

Results

The 2TT mouse: A model to dissect the respective roles of Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells in vivo after allogeneic islet transplant

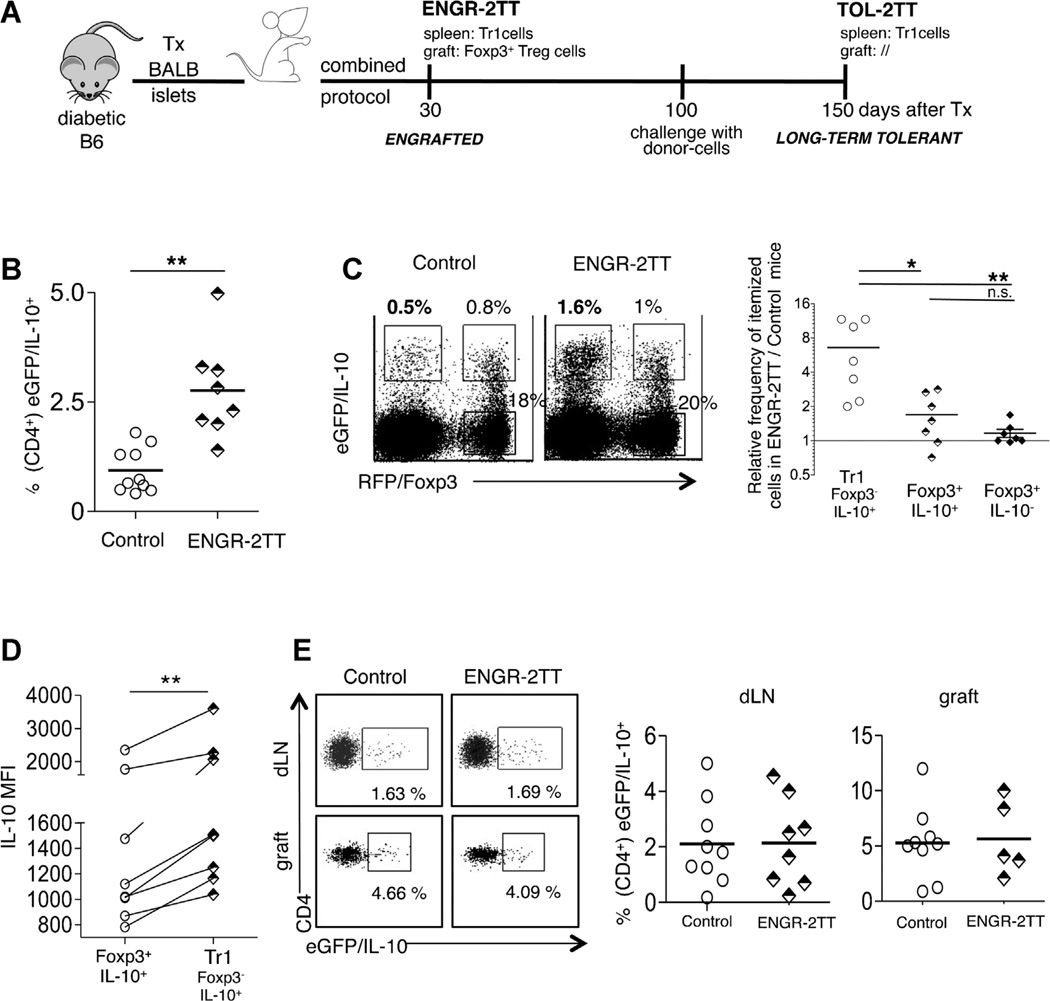

We previously demonstrated that a treatment composed of anti-CD45RB mAb + rapamycin + IL-10 (named “combined protocol”) promotes transplant tolerance in diabetic C57BL/6 (B6) mice transplanted with BALB/c (BALB) islets (11). In these mice the engraftment is accompanied by the accumulation of Foxp3+ Treg cells in the transplant and of Ag-specific CD4+IL-10+IL-4− T cells (i.e. Tr1 cells) in the spleen, which remain expanded also in the spleen of long-term tolerant mice (11). We designated this animal model “2TT (i.e. comprising 2 Treg-cell Types). Engrafted mice, analyzed 30 days after transplantation (i.e. immediately following treatment withdrawal) and which do not reject the allograft are defined as ENGR-2TT mice. Tolerant mice sacrificed 150 days following transplantation and which remain tolerant to the allograft even after receiving a challenge with donor-cells 100 days after transplantation, are defined as TOL-2TT mice (Figure 1A for a schematic depiction of this model).

Figure 1. The combined protocol induces Tr1 cells selectively in the spleen of 2TT-mice.

(A) A schematic depicting of the 2TT mouse model where diabetic B6 mice are transplanted with islets from BALB mice and are treated with the combined protocol for 30 days. (B) Diabetic double reporter B6 Fir/Tiger mice were transplanted with BALB islets and were either left untreated and analyzed once they rejected the graft (Control) or treated with the combined protocol and analyzed 30 days after transplantation (ENGR-2TT). The frequency of CD4+ eGFP/IL-10+ cells in the spleen of all control and ENGR-2TT mice is shown. (C) One representative dot plot of splenic cells isolated from one control and one ENGR-2TT mouse gated on CD4+ T cells is shown (left panel). The frequencies of CD4+ Foxp3−IL-10+ (Tr1), Foxp3+IL-10+and Foxp3−IL-10− in the spleen of ENGR-2TT mice were averaged and divided by the average of the same cell types found in the spleen of control untreated mice (right panel). (D) The IL-10MFI of Foxp3+IL-10+andof CD4+ Foxp3−IL-10+ (Tr1), gated on CD4+T cells residing in the spleen of all control and ENGR-2TTmice, is plotted. Lines link analyses performed in the same mouse. (E) One representative dot plot of cells isolated from the dLN and from the graft of one control and one ENGR-2TT mouse is shown (left panel). The frequencies of CD4+ eGFP/IL-10+ in the dLN and in the graft of all control and ENGR-2TT mice are plotted (right panel). Lines represent mean values (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.005).

Tr1 cells do not constitutively express Foxp3 and are characterized by the production of high levels of IL-10, which is also the key cytokine for their regulatory activity (8). While the suppressive function of Foxp3+ Treg cells is not strictly dependent on IL-10 production, such cells can release this cytokine (reviewed in Ref. (6)). Consequently, the distinction between Foxp3+IL-10+ Treg and Tr1 cells remains controversial. To overcome this constraint we used the double reporter mouse model for Foxp3 (Foxp3-RFP)and IL-10 (Il10-eGFP; i.e. the Fir/Tiger mouse) (19). The advantages of this model predominantly rely on the fact that the cells isolated from double reporter mice do not require re-activation in vitro to detect IL-10-production, and moreover, Foxp3+- and Foxp3−-IL-10-producing T cells can be readily distinguished (19). We used this model to expand upon our original observation that CD4+IL-10+IL-4− T cells accumulate in the spleen of 2TT mice (11). The presence of increased CD4+ IL-10+ T cells in the spleen of ENGR-2TT wt mice as compared to control untreated animals was confirmed in Fir/Tiger mice (Figure 1B). IL-10+ T cells were not found enriched in mice treated in the absence of pancreatic islet transplantation (data not shown). Interestingly, the Foxp3−IL-10+ (Tr1) cells were more responsive to the combined treatment compared to Foxp3+ cells (either IL-10+ or IL-10−; Figure 1C). Moreover, the IL-10-MFI levels were higher in Tr1 cells than in Foxp3+IL-10+ Treg cells (Figure 1D). This demonstrates that Tr1 cells produce higher levels of IL-10 on a per-cell basis than do Foxp3+IL-10+Treg cells, as observed in other animal models (20,21). Finally, the use of Fir/Tiger mice confirmed that IL-10+ T cells were not expanded in the draining lymph-nodes (dLN) or within the graft of treated mice in comparison to untreated animals (Figure 1E). However, the frequency of IL-10-producing cells is better measurable in nontransgenic mouse models in which we specifically showed that the spleen of treated animals contain about 20% of IL-10+IL4− Tr1 cells while the dLN and the graft only 2% (11).

Thus, the Fir/Tiger mouse confirms that our 2TT mouse is an ideal model to study the potential in vivo collaboration between Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells and the role played by the spleen as well as the graft in the induction and maintenance of tolerance to allogeneic transplant.

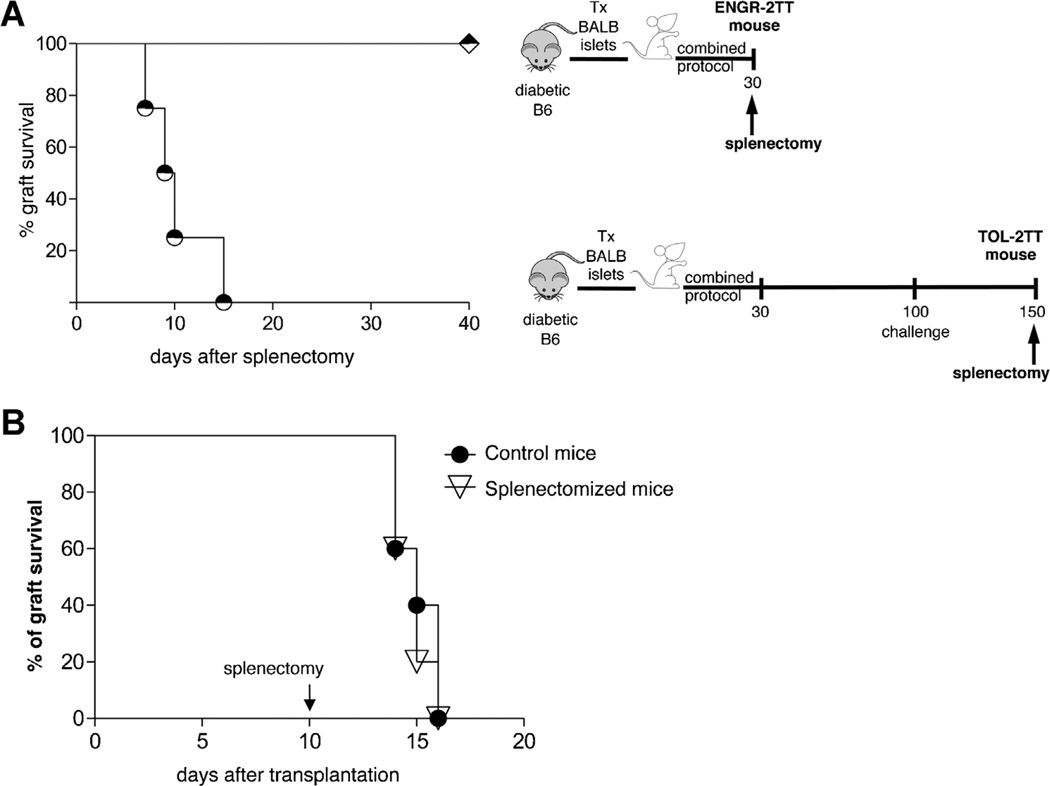

Transplant tolerance is maintained in the spleen

Alloantigen presentation occurs primarily in the spleen, suggesting that this organ is key for transplant tolerance (22,23). To investigate the role of the spleen in initiating and maintaining long-term tolerance we examined the effect of splenectomy in ENGR- versus TOL-2TT mice. None of the splenectomized ENGR-2TT mice rejected the graft, whereas all the TOL-2TT mice lost the graft within 2 weeks of spleen removal (Figure 2A). As a control, we showed that splenectomy, performed 10 days after transplantation, did not perturb the expected time of allograft rejection in untreated mice (Figure 2B). These data show that the spleen is a key organ in the maintenance of allograft tolerance, but not for its initiation.

Figure 2. Transplant tolerance is maintained in the spleen.

(A) Graft survival in ENGR-2TT mice splenectomized 35 days (diamonds, n = 7) or 150 days (circles, n = 4) after transplantation is shown. The cartoon depicting the specific experiment is displayed in proximity. (B) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets (n = 10). Mice were left untreated and 10 days after transplantation a group of mice were splenectomyzed (n = 5) while others were not (n = 5). Percentage of graft survival is shown.

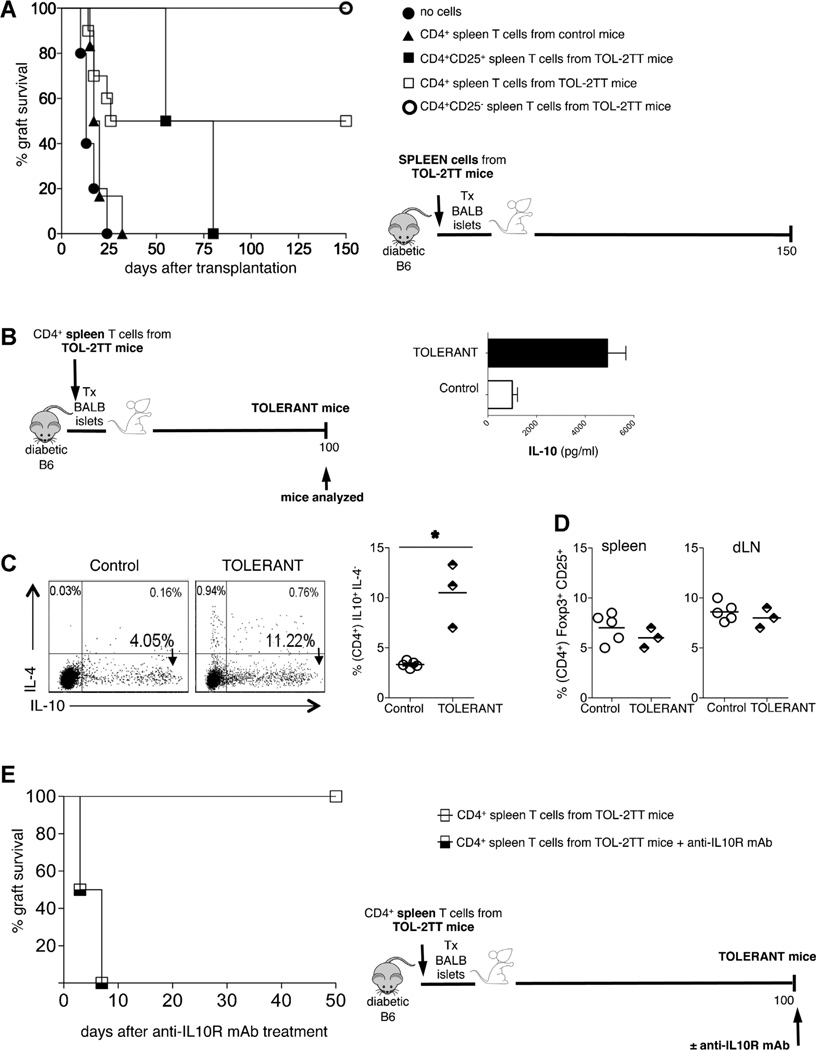

Given our previous demonstration that IL-10 is essential for tolerance maintenance in TOL-2TT mice and that the combined protocol induces CD4+CD25−Foxp3−IL-10+ Tr1 cells exclusively in the spleen (11), we sought to evaluate the regulatory function of these cells. Total CD4+ T cells or CD4+CD25− T cells, both enriched in Tr1 cells, were isolated from the spleen of TOL-2TT mice and transferred in newly transplanted animals, which were left untreated. Both cell subsets displayed strong in vivo regulatory activity, which was higher upon transfer of CD4+CD25− T cells. On the contrary, transfer of CD4+CD25+ T cells, enriched in Foxp3+ Treg cells, isolated from the spleen of TOL-2TT mice delayed graft rejection but did not promote long-term tolerance (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Splenic CD4+CD25T− cells contain Tr1 cells and have a strong regulatory capacity.

(A) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets and left untreated (filled circles n = 5), or the day before transplant were injected with CD4+ spleen T cells isolated from transplanted and untreated control mice (filled triangles, n = 6), or with CD4+CD25+ spleen T cells from TOL-2TT mice (filled squares, n = 2), or with CD4+spleen T cells isolated from TOL-2TT mice (empty squares, n = 10), or with CD4+CD25− spleen T cells from TOL-2TT mice (empty circles, n = 4). The graft survival curves are shown on the left while the cartoon depicting the experiment is shown on the right. (B) Mice that became tolerant upon the mere transfer of CD4+ spleen T cells isolated from TOL-2TT mice were analyzed 100 days after cell transfer (TOLERANT) and B6 mice transplanted and untreated were analyzed as soon as they rejected the graft (control). The cartoon depicting the experiment is shown on the left while the amount of IL-10 released from CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen of tolerant (black bars, n = 3) and control (white bars, n = 5) mice is shown on the right (mean ± SEM). (C) Representative dot plots of IL-10 and IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells from one control and one tolerant mouse are shown on the left. The results collected from all mice analyzed are shown on the right. Bars represent mean values (*p < 0.05). (D) Frequency of Foxp3+CD25+cells (gated on CD4+T cells) in the spleen and dLN of control and tolerant mice. (E) Mice that became tolerant upon the mere transfer of CD4+ spleen T cells isolated from TOL-2TT mice were either injected with the anti-IL-10R mAb (half-black squares, n = 2) or with PBS (empty squares, n = 3) 100 days after transplantation. The percentage of graft survival is shown on the left while the cartoon depicting the specific experiment is shown on the right.

Mice that became tolerant to allograft following the mere transfer of splenic CD4+ T cells isolated from TOL-2TT mice were analyzed 100 days after cell injection. A significant expansion of CD4+ IL-10-producing T cells (Figure 3B) and of frequency of CD4+IL-10+IL-4− Tr1 cells was observed in the spleen of these same mice (Figure 3C). On the other hand, there was no evidence of Foxp3+ Treg cell expansion in the spleen or in the dLN (Figure 3D). This tolerance was IL-10 dependent, since injection of anti-IL10R mAb 100 days after cell transfer led to graft rejection (Figure 3E).

Taken collectively these data show the strong regulatory activity of CD4+CD25− T cells, which localize in the spleen of mice that became tolerant to allogeneic islets upon treatment with the combined protocol. Their transfer to newly transplanted and untreated mice mediates long-term tolerance, which is again associated with, and mediated by IL-10.

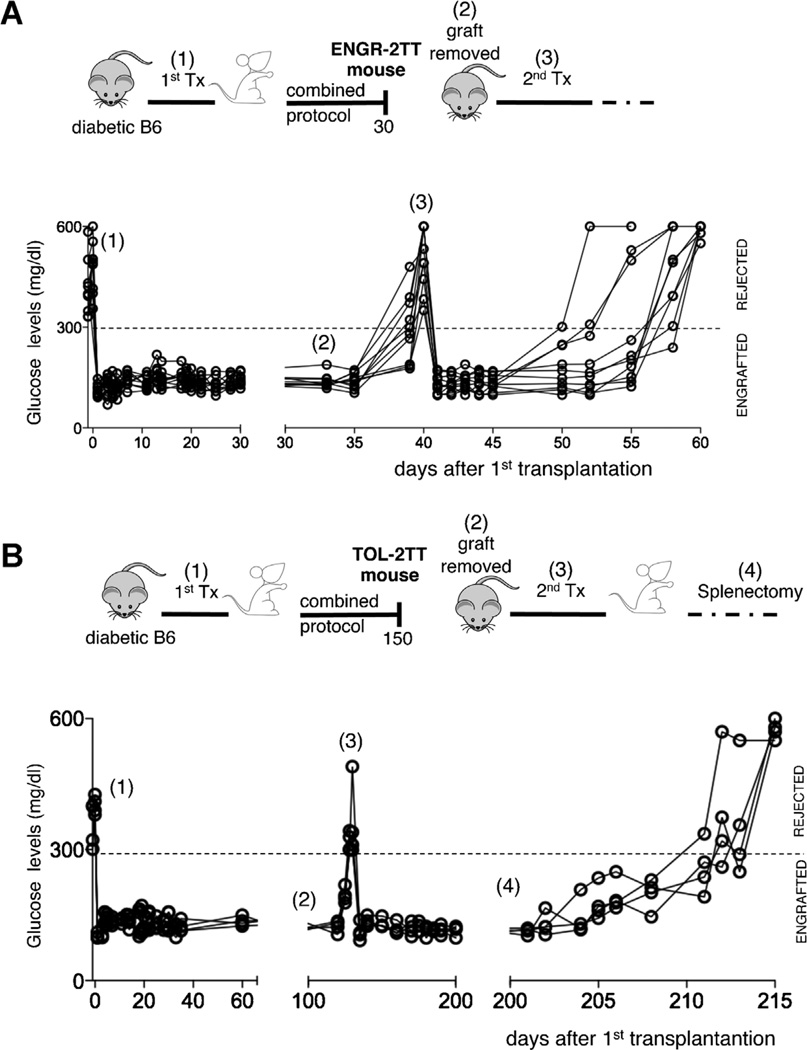

Transplant tolerance is initiated within the graft

We next tested the roles played by the cells infiltrating the graft in 2TT mice. The graft, and consequently all the cells that accumulate there, was removed from ENGR-2TT mice (i.e. immediately upon completion of treatment). As expected, given the lack of insulin producing cells, all mice promptly became hyperglycemic. A second islet transplant was performed in the contralateral kidney and all the mice rapidly returned to normoglycemia. However, over the next 15–20 days, all recipient rejected the second allograft (Figure 4A). The exact same experiment was performed in TOL-2TT mice. In marked contrast to the ENGR-2TT mice, TOL-2TT mice did not reject the second transplant placed after removal of the original graft. However, these same mice promptly rejected the second graft following splenectomy, showing that effector T cells are still present and confirming the key role of the spleen in maintaining transplant tolerance (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Transplant tolerance initiates within the graft.

(A) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets (1) and were treated with the combined protocol. Thirty days after transplantation the graft was removed from ENGR-2TT mice (2). A second islet transplant was performed in the controlateral kidney of mice returned diabetic (3). The cartoon depicting the specific experiment and time points is shown on top, while the blood glucose levels of each of the animal tested (n = 10) are shown below. (B) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets (1) and were treated with the combined protocol. One hundred fifty days after transplantation the graft was removed from TOL-2TT mice (2). A second islet transplant was performed in the controlateral kidney of mice returned diabetic (3) and upon normalization of the glucose levels mice were splenectomized (4). The cartoon depicting the specific experiment and time points is shown on top, while the blood glucose levels of each of the animal tested (n = 4) are shown below.

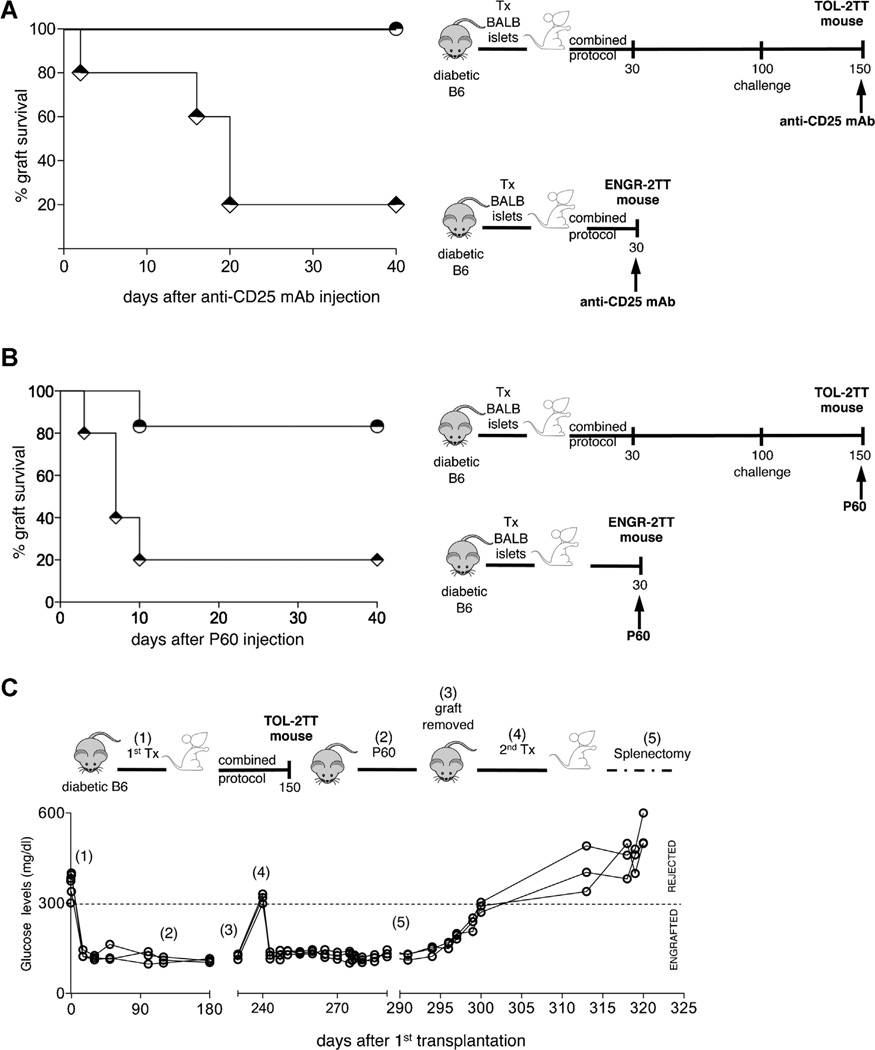

Given that CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells accumulate in the graft of ENGR-2TT mice (11), the role played in vivo by these cells was directly tested. Accordingly, we injected ENGR- and TOL-2TT mice with an anti-CD25 mAb (i.e. the PC61) or with P60, a peptide shown to impair Foxp3+ Treg-cell function in vivo (14). Four out of five ENGR-2TT mice treated with the PC61 mAb rejected the graft while none of the TOL-2TT mice became diabetic upon mAb injection (Figure 5A). Similarly, treatment of 2TT mice with P60 led to graft rejection in four out of five ENGR-2TT mice while only one out six TOL-2TT mice treated with P60 became diabetic (Figure 5B). Importantly, TOL-2TT mice that remained normoglycemic upon P60-treatment promptly rejected a second islet graft after splenectomy further confirming the key role of the spleen in transplant tolerance maintenance (Figure 5C). These data show that the graft is key in tolerance initiation but not in its maintenance.

Figure 5. Foxp3+ Treg cells play a key role in tolerance induction.

(A) Graft survival in ENGR-2TT (diamonds, n = 5) or in TOL-2TT (circles, n = 4) mice injected with anti-CD25 mAb is shown. The cartoon depicting the specific experiment is displayed in proximity. (B) Graft survival in ENGR-2TT (diamonds, n = 5) or in TOL-2TT (circles, n = 6) injected with P60 is shown. The cartoon depicting the specific experiment is displayed in proximity. (C) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets (1) and were treated with the combined protocol. One hundred fifty days after transplantation the TOL-2TT mice were treated with P60 (2). Two hundred days after transplant the graft was removed from TOL-2TT mice (3) and a second islet transplant was performed in the controlateral kidney of mice returned diabetic (4). Upon normalization of the glucose levels, all mice were splenectomized (5). The cartoon depicting the specific experiment and time points is shown on top, while the blood glucose levels of each of the animal tested (n = 3) are shown below.

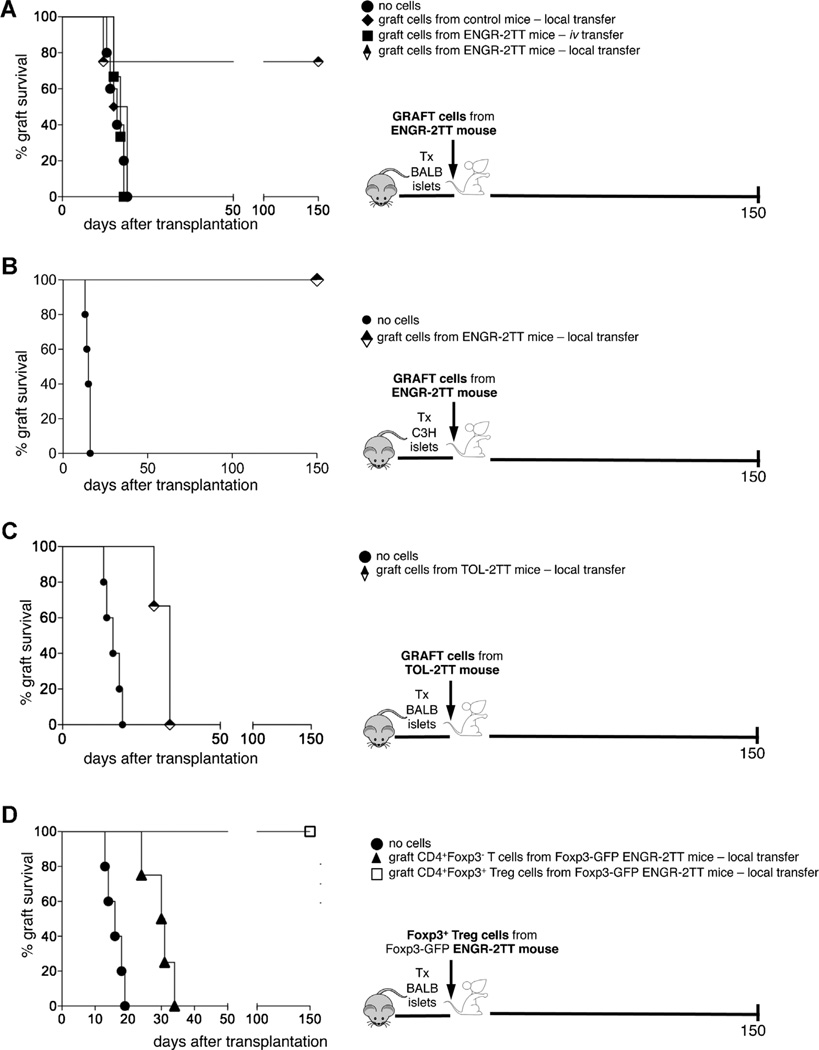

To now define whether the cells infiltrating the graft, which are rich in Foxp3+ Treg cells (11), possess regulatory function, we transferred total cells isolated from the graft of ENGR-2TT mice in newly transplanted mice. Interestingly, transfer of graft-infiltrating cells led to allograft tolerance only when transferred locally together with the islets and not when transferred systemically by i.v. injection (Figure 6A). These cells exhibited a regulatory activity even when transferred locally with the graft into mice transplanted with third party islets (Figure 6B). Conversely, the local transfer of total cells isolated from the graft of TOL-2TT mice with the allogeneic islets did not transfer tolerance in newly transplanted mice (Figure 6C). In general agreement, we previously showed that at this later time-point, graft-infiltrating CD4+ T cells are no longer enriched for Foxp3+ Treg cells (11).

Figure 6. The graft of 2TT mice is rich in Foxp3+ T cells with regulatory capacity.

(A) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets and left untreated (filled circles n = 5), or the day before the transplant were injected locally with the cells isolated from the graft of transplanted and untreated control mice (filled diamonds, n = 3), or intravenously (filled squares, n = 3) or locally (half-black diamonds, n = 4) with cells isolated from the graft of ENGR-2TT mice. The graft survival curves are shown on the left while the cartoon depicting the experiment is shown on the right. (B) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets and left untreated (filled circles n = 5), or the day before transplant of third party islets were injected locally with the cells isolated from the graft of ENGR-2TT mice (half-black diamonds, n = 3). The graft survival curves are shown on the left while the cartoon depicting the experiment is shown on the right. (C) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets and left untreated (filled circles n = 5), or the day before the transplant were injected locally with the cells isolated from the graft of TOL-2TT mice (half-black diamonds, n = 3). The graft survival curves are shown on the left while the cartoon depicting the experiment is shown on the right. (D) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with BALB islets and left untreated (filled circles n = 5), or the day before the transplant were injected locally with CD4+ Foxp3∼ T cells isolated from the graft of Foxp3-GFP ENGR-2TTmice (filled triangles, n = 4) or with CD4+ Foxp3+T cells isolated from the graft of Foxp3-GFP ENGR-2TTmice (empty squares, n = 3). The graft survival curves are shown on the left while the cartoon depicting the experiment is shown on the right.

To prove that the tolerogenic properties of total graft infiltrating cells are confined to the Foxp3+ Treg-cell compartment, we used Foxp3+-GFP reporter mice. Foxp3+ Treg cells were therefore isolated from the grafts of ENGR-2TT Foxp3-GFP reporter mice and transferred along with allogeneic islets into newly transplanted animals. The local transfer of pure Foxp3+ Treg but not of Foxp3− CD4+ T cells led to long-term survival of allogeneic islets (Figure 6D). These data show that Foxp3+ Treg cells infiltrating the graft after allogeneic islet transplant at the time of tolerance induction can transfer active tolerance in newly transplanted and otherwise untreated mice, and moreover, these act locally in an Ag non-specific manner.

Long-term tolerance induced by Foxp3+ Treg-cell transfer is sustained by splenic Tr1 cells

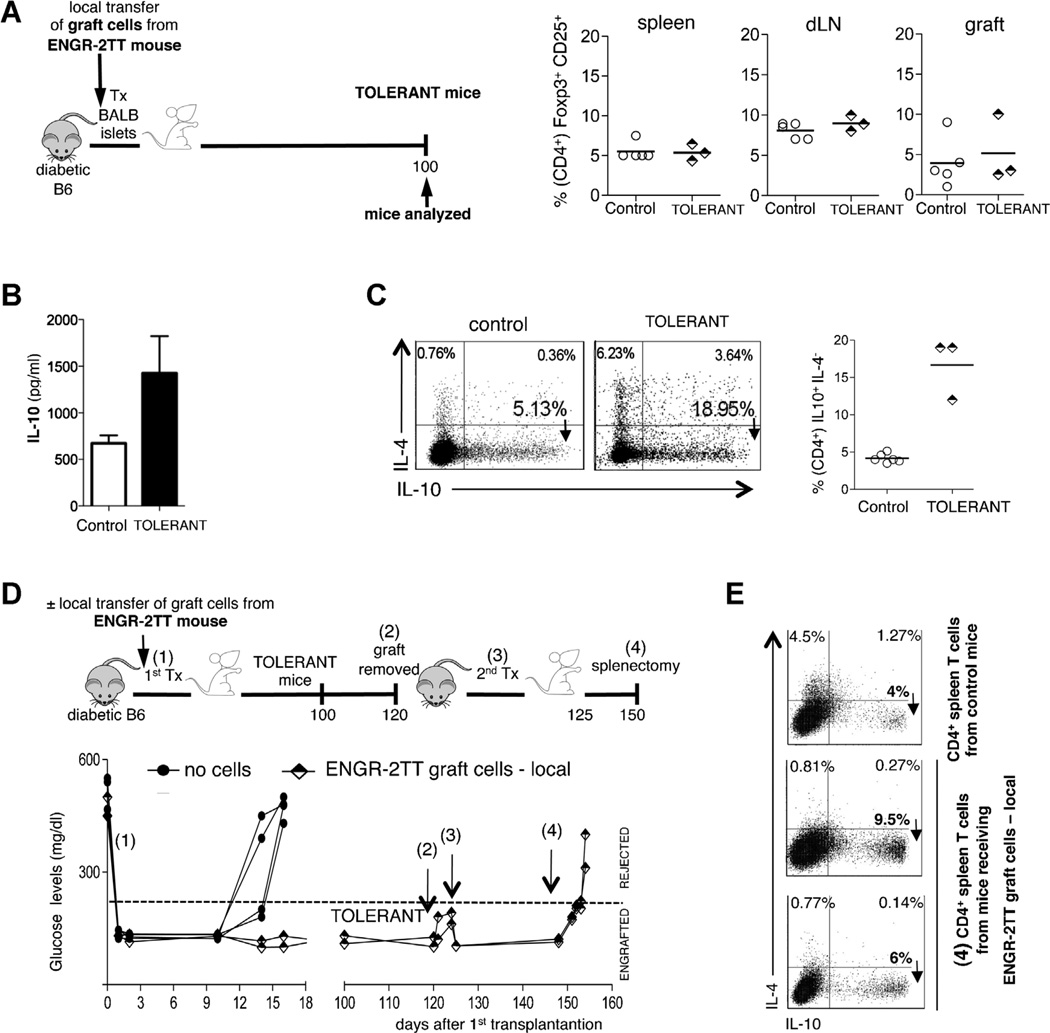

Despite our data showing that the graft infiltrating cells are not important for maintaining tolerance, we found that the mere transfer of these cells into newly transplanted and otherwise untreated mice was sufficient to induce long-term tolerance. To clarify this apparent discrepancy, we investigated the mechanism underlying long-term tolerance induced by the transfer of the graft-infiltrating cells. While the cells isolated from the grafts of ENGR-2TT mice were abundant in Foxp3+ Treg cells, after local transfer with islets into new recipients, we did not find an expansion of Foxp3+ Treg cells in the spleen, dLN, or within the graft (Figure 7A). In contrast, a significant increase in both IL-10 secretion by CD4+ T cells (Figure 7B) and frequency of IL-10 expressing CD4+ Tr1 cells (averaging 15%) was observed in the spleen of these same mice (Figure 7C). Based on these results, we hypothesize that the Foxp3+ Treg cell transfer generates a state of tolerance and that tolerance is sustained by Tr1 cells, similar to what we observed in 2TT mice. To test this hypothesis, graft-infiltrating cells isolated from ENGR-2TT mice and rich in Foxp3+ Treg cells were transferred locally with new islets into new recipient mice, which became tolerant. One hundred and twenty days after cell transfer and transplantation, the graft was surgically removed from tolerant mice and a second transplant with islets isolated from the original donor strain was performed. None of these mice rejected the second graft, thus showing that the cells present within the graft were not responsible for tolerance maintenance. Thirty days after the second islet transplant, the spleen was removed, resulting in prompt rejection of the graft (Figure 7D). Analysis of the removed spleens revealed the presence of CD4+IL-10+IL-4−T cells (Figure 7E). These data show that long-term tolerance induced by Foxp3+ Treg-cell transfer is sustained by splenic Tr1 cells and functionally moves from the allograft to the spleen.

Figure 7. Graft infiltrating cells from ENGR-2TT mice transfer long-term tolerance, which is sustained by the spleen.

(A) Mice that became tolerant upon the mere transfer of cells isolated from the graft of ENGR-2TT mice were analyzed 100 days after cell transfer (TOLERANT, n = 3). Age matched B6 mice transplanted and untreated were analyzed as soon as they rejected the graft (control n = 5). The cartoon depicting the experiment is shown on the left, while the percentages of CD25+Foxp3+ (among CD4+T cells) in the spleen, dLN and in the graft of all mice analyzed are reported on the right (bars represent mean values). (B) The amount of IL-10 released from CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen of control (white bars, n = 5) and tolerant (black bars, n = 3) mice after in vitro polyclonal stimulation are shown (mean ± SEM). (C) Representative dot plots of IL-10/IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells from one control and one tolerant mouse are shown on the left. The results collected from all mice analyzed are shown on the right (bars represent mean values). (D) Diabetic B6 mice were transplanted with allogeneic islets and the day before transplant were left untreated (filled squares, n = 4) or were injected locally with graft-cells from ENGR-2TTmice (half-black diamonds, n = 2) (1). One hundred twenty days after transplantation, the graft was removed from the tolerant mice which had received the local transfer of graft-cells (2). Five days later, a second islet transplant was performed with islets of the original donor (3). Twenty-five days after the second transplant, mice were splenectomized (4). The cartoon depicting the specific experiment and time points is shown on top, while the blood glucose levels of each of the animal tested are shown below. (E) CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleens collected at the time point (4) and the frequency of IL-10/IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells was tested by intracellular staining. As control, splenic CD4+ T cells from age-matched transplanted and untreated mice were used.

Discussion

The 2TT mouse model allowed us, for the first time, to simultaneously address still ill-defined features of Foxp3+-Treg and Tr1 cells as well as to investigate their in vivo relationship. In 2TT mice, donor-specific tolerance was induced following allogeneic transplantation through a unique combined protocol consisting of anti-CD45RB mAb + rapamycin + IL-10. We found that Foxp3+ Treg cells, with a non-Ag specific regulatory capacity, accumulate early into the graft and subsequently in the dLN. In contrast, Tr1 cells are found in the spleen during both the engraftment as well as the steady-state tolerant stages. Despite the fact that once isolated from 2TT mice, both Foxp3+ Treg and CD4+CD25− cells, which contain Tr1 cells, demonstrate powerful in vivo regulatory capacity in adoptive transfer experiments, when they coexist in the same animal, they exhibit distinct and nonredundant roles: Foxp3+ Treg cells are vital exclusively for engraftment, whereas splenic CD4+CD25− cells, rich in Tr1 cells, are critical for maintaining long-term tolerance. Moreover, transfer of non-Ag specific Foxp3+ Treg cells from tolerant 2TT mice into the graft of newly transplanted and otherwise untreated hosts, results in the induction of tolerance which is no longer dependent on the intragraft Foxp3+ Treg cells themselves, but rather on the de novo generation of splenic Tr1 cells. Thus, these data suggest that graft non-Ag specific Foxp3+ Treg cells present in the graft “hand tolerance over” to splenic Tr1 cells after allogeneic transplantation.

Our first conclusion is that Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells differ in their time of action following allogeneic transplantation. It is conceivable that non-Ag specific Foxp3+ Treg cells represent the first line of regulatory cells to assume control of allogeneic graft rejection: being that such cells are naturally present in the host where they are both available and can be targeted by our tolerogenic treatment (11). In contrast, Ag-specific Tr1 cells, which take time to be induced upon Ag stimulation and under the umbrella of rapamycin + IL-10(9), act later to maintain tolerance. In line with such a temporally distinct role for Treg cells in 2TT mice, studies performed in other mouse models of allogeneic transplantation have also demonstrated that Foxp3+ Treg cells are fundamental during the early phase of tolerance induction but dispensable subsequently (15,16,24). These studies suggested that Foxp3+ Treg cells “pass the tolerance torch” to other cells. We now demonstrate that transfer of Foxp3+ Treg cells results in Tr1-cell induction. Considering we analyzed the animals at 30 days after transplantation, we cannot exclude at this time that the cells distribute differently during the window of the 30-day treatment. Interestingly, in a mouse model of skin transplantation in which the potential alloreactive T cells remain over time into the graft and Tr1 cells are not expanded, the constant presence of Foxp3+ Treg cells in the skin is required for maintaining tolerance (25). These data underline once more how finely the collaboration between Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells is finely tuned accordingly to the type of transplant and immune response.

Our second conclusion is that Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells consistently localize to different organs in the same tolerant hosts. Foxp3+ Treg cells infiltrate the allogeneic graft, while Tr1 cells accumulate in the spleen during both the engraftment and the tolerant stages. This different localization of Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells is likely due to the differential expression of various chemokine receptors that are fundamental for cell migration. For example, Foxp3+ Treg cells express CCR2, CCR4, and CCR5, which drive their homing to the graft, and also CD62L and CCR7, which are key for their migration to secondary lymphoid organs (12). Interestingly, it has been show that Tr1 cells express low concentration of CD62L (26). Further investigation into the chemokine-receptor repertoire of Tr1 cells is required for full comprehension of their in vivo migratory pattern. Tissue-specific IL-10 levels could also influence differences in Treg-cell localization. The levels of IL-10 (27) and the tissue where this cytokine is released (28) are key in determining whether IL-10 fulfills a tolerogeneic or a pro-inflammatory function in vivo. For instance, high levels of IL-10 released in close proximity to the pancreatic islets can trigger a detrimental pro-inflammatory response (29). However, in apparent contrast, Foxp3+ Treg cells need close proximity to the transplanted islets and to release IL-10 in order to efficiently delay graft rejection (12). We speculate that Tr1 cells, which produce high levels of IL-10, remain far from the graft, where they could be detrimental, whereas Foxp3+ Treg cells, which produce IL-10 to a lower extent, can accumulate in the target organ without predisposing it to inflammation.

One intriguing question is how splenic IL-10-producing Tr1 cells maintain tolerance far from the site of transplantation. Among its many regulatory properties, IL-10 can directly block the release of IL-2 and TNF-α by CD4+ T cells and down-regulate the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by antigen presenting cells (APC) (reviewed in Ref. (8)). It is known that APC circulate to the graft, encounter and process allo-Ag, and then migrate mainly to the spleen, where they can efficiently prime naïve T cells (23,30). Thus, one can hypothesize that splenic Ag-specific Tr1 cells can exert their regulatory function in this organ directly by modulating the APC, the effector T cells, or both. Alternatively, Tr1 cells can interfere with the migration of already efficiently primed effector T cells, as we have previously demonstrated in a murine model of type 1 diabetes (13).

The last conclusion is that the mere transfer of Foxp3+ Treg cells from the grafts of ENGR-2TT mice into newly transplanted mice leads to stable long-term tolerance, which is ultimately maintained by Tr1 cells and not by the transferred cells. This phenomenon has been previously investigated. Human CD4+CD25+ Treg cells can give rise to Tr1-like cells in vitro (31) and these findings have led to the proposal that small numbers of non-Ag specific CD4+CD25+ Treg cells may increase their effectiveness by catalyzing the formation of additional Ag-specific Treg cells. Such phenomenon was also demonstrated in vivo in a model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (32,33). Our data demonstrate that this phenomenon runs not only from non-Ag specific Foxp3+ Treg to Tr1 cells, but also involves Treg cells located in different tissues, moving from the graft to the spleen. How and where this instruction actually takes place will require additional investigation.

In conclusion, we suggest that Foxp3+ Treg and Tr1 cells play distinct temporal and spatial roles in the initiation and maintenance of tolerance and that both cell populations acting in concert are essential for promoting robust long-term tolerance. Our data shed new light on the immune system’s requirement for more than one Treg-cell subset and have also important application for the design of clinical protocols aimed at inducing tolerance with immunomodulatory agents or through cell therapy approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Andrea Annoni, Laura Passerini, Samuel Huber and Enric Esplugues for helpful and continuous discussion. We are grateful to Juan José Lasarte and Noelia Casares from the Departamento de Medicina Interna, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona (Spain), for providing the P60 compound. This work has been supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant 7-2006-328 to M.B.

Abbreviations

- 2TT mice

mice comprising two Treg-cell types

- ENGR-2TT mice

engrafted mice analyzed 30 days after transplant

- TOL-2TT mice

tolerant mice analyzed 150 days after transplant and after donor cell boost

- Fir/Tiger mice

double reporter mice Foxp3-RFP and Il10-eGFP

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

Supplemental Materials and Methods

References

- 1.Workman CJ, Szymczak-Workman AL, Collison LW, et al. The development and function of regulatory T cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(16):2603–2622. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belkaid Y, Chen W. Regulatory ripples. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(12):1077–1078. doi: 10.1038/ni1210-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li XC, Turka LA. An update on regulatory T cells in transplant tolerance and rejection. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(10):577–583. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feuerer M, Hill JA, Mathis D, et al. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells: Differentiation, specification, subphenotypes. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(7):689–695. doi: 10.1038/ni.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang Q, Bluestone JA. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: A jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(3):239–244. doi: 10.1038/ni1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pot C, Apetoh L, Awasthi A, et al. Molecular pathways in the induction of interleukin-27-driven regulatory type 1 cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2010;30(6):381–388. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Battaglia M, et al. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:28–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Draghici E, et al. Rapamycin and interleukin-10 treatment inducesTregulatory type 1cells that mediate antigen-specific transplantation tolerance. Diabetes. 2006;55(1):40–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber S, Gagliani N, Esplugues E, et al. Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3 and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34(4):554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagliani N, Gregori S, Jofra T, et al. Rapamycin combined with anti-CD45RB mAb and IL-10 or with G-CSF induces tolerance in a stringent mouse model of islet transplantation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e28434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang N, Schroppel B, Lal G, et al. Regulatory T cells sequentially migrate from inflamed tissues to draining lymph nodes to suppress the alloimmune response. Immunity. 2009;30(3):458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Draghici E, et al. Induction of tolerance in type 1 diabetes via both CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cells and T regulatory type 1 cells. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1571–1580. doi: 10.2337/db05-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casares N, Rudilla F, Arribillaga L, et al. A peptide inhibitor of FOXP3 impairs regulatory T cell activity and improves vaccine efficacy in mice. J Immunol. 2010;185(9):5150–5159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo X, Pothoven KL, McCarthy D, et al. ECDI-fixed allogeneic splenocytes induce donor-specific tolerance for long-term survival of islet transplants via two distinct mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(38):14527–14532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805204105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller YD, Mai G, Morel P, et al. Anti-CD154 mAb and rapamycin induce T regulatory cell mediated tolerance in rat-to-mouse islet transplantation. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fecteau S, Basadonna GP, Freitas A, et al. CTLA-4 up-regulation plays a role in tolerance mediated by CD45. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(1):58–63. doi: 10.1038/83175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagliani N, Jofra T, Stabilini A, et al. Antigen-specific dependence of Tr1-cell therapy in preclinical models of islet transplant. Diabetes. 2010;59(2):433–439. doi: 10.2337/db09-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamanaka M, Kim ST, Wan YY, et al. Expression of interleukin-10 in intestinal lymphocytes detected by an interleukin-10 reporter knockin tiger mouse. Immunity. 2006;25(6):941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumgart M, Tompkins F, Leng J, et al. Naturally occurring CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are an essential, IL-10-independent part of the immunoregulatory network in Schistosoma mansoni egg-induced inflammation. J Immunol. 2006;176(9):5374–5387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagase H, Jones KM, Anderson CF, et al. Despite increased CD4+ Foxp3+ cells within the infection site, BALB/c IL-4 receptor-deficient mice reveal CD4+ Foxp3-negative T cells as a source of IL-10 in Leishmania major susceptibility. J Immunol. 2007;179(4):2435–2444. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burrell BE, Bromberg JS. Fates of CD4(+) T cells in a tolerant environment depend on timing and place of antigen exposure. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(3):576–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dijke IE, Weimar W, Baan CC. Regulatory T cells after organ transplantation: Where does their action take place? Hum Immunol. 2008;69(7):389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster KE, Walters S, Kohler RE, et al. In vivo expansion of T reg cells with IL-2-mAb complexes: Induction of resistance to EAE and long-term acceptance of islet allografts without immunosuppression. J Exp Med. 2009;206(4):751–760. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendal AR, Chen Y, Regateiro FS, et al. Sustained suppression by Foxp3+ regulatory T cells is vital for infectious transplantation tolerance. J Exp Med. 2011;208(10):2043–2053. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maynard CL, Harrington LE, Janowski KM, et al. Regulatory T cells expressing interleukin 10 develop from Foxp3+ and Foxp3-precursor cells in the absence of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):931–941. doi: 10.1038/ni1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Smith S, et al. Interleukin-10 administration decreases survival in murine recipients of major histocompatibility complex disparate donor bone marrow grafts. Blood. 1995;85(3):842–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wogensen L, Huang X, Sarvetnick N. Leukocyte extravasation into the pancreatic tissue in transgenic mice expressing interleukin 10 in the islets of Langerhans. J Exp Med. 1993;178(1):175–185. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregg RK, Bell JJ, Lee HH, et al. IL-10 diminishes CTLA-4 expression on islet-resident T cells and sustains their activation rather than tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;174(2):662–670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saiki T, Ezaki T, Ogawa M, et al. In vivo roles of donor and host dendritic cells in allogeneic immune response: Cluster formation with host proliferating T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69(5):705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dieckmann D, Bruett CH, Ploettner H, et al. Human CD4(+)CD25 (+) regulatory, contact-dependent T cells induce interleukin 10-producing, contact-independent type 1-like regulatory T cells [corrected] J Exp Med. 2002;196(2):247–253. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mekala DJ, Alli RS, Geiger TL. IL-10-dependent infectious tolerance after the treatment of experimental allergic encephalo-myelitis with redirected CD4+ CD25+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(33):11817–11822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505445102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selvaraj RK, Geiger TL. Mitigation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by TGF-beta induced Foxp3+ regulatory T lymphocytes through the induction of anergy and infectious tolerance. J Immunol. 2008;180(5):2830–2838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.