Abstract

Genome-wide significant associations with cigarettes per day (CPD) and risk for lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were previously reported in a region of 19q13, including CYP2A6 (nicotine metabolism enzyme) and EGLN2 (hypoxia response). The associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were assumed to be proxies for functional variation in CYP2A6. Here, we demonstrate that when CYP2A6 and EGLN2 genotypes are analyzed together, the key EGLN2 variant, rs3733829, is not associated with nicotine metabolism independent of CYP2A6, but is nevertheless independently associated with CPD, and with breath carbon monoxide (CO), a phenotype associated with cigarette consumption and relevant to hypoxia. SNPs in EGLN2 are also associated with nicotine dependence and with smoking efficiency (CO/CPD). These results indicate a previously unappreciated novel mechanism behind genome-wide significant associations with cigarette consumption and disease risk unrelated to nicotine metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

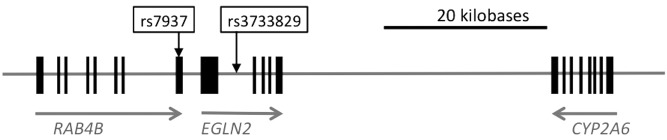

Despite reduced prevalence, tobacco use remains the largest cause of preventable mortality in the USA and worldwide (1). Smoking phenotypes are highly complex but nevertheless strongly influenced by heritable factors (2–4), and therefore genetic studies provide a tool to reveal their underlying biology and improve smoking cessation treatment. Although multiple unbiased genetic studies have been performed and many candidates otherwise investigated, thus far genes in only two pathways have consistently demonstrated associations with smoking behaviors (5–7). The loci most strongly and consistently associated with nicotine dependence, cigarettes per day (CPD), and smoking cessation, are the nicotinic receptor genes CHRNA5–CHRNA3–CHRNB4 (direct targets of nicotine in the central nervous system) at 15q25(5,7–12), and the primary nicotine metabolism gene CYP2A6(13,14), at 19q13. CYP2A6 was identified in two large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of CPD in European subjects. In one study, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs4105144, located 5′ of CYP2A6, showed the strongest association with CPD in that chromosomal region (7). The same study also reported a nominal association between rs4105144 and lung cancer (7). rs4105144 is in tight linkage disequilibrium (D′ = 1) with most of the important functional polymorphisms in CYP2A6 that occur in Europeans (15). The second GWAS identified a different SNP on chromosome 19, rs3733829 (minor allele frequency = 32%), ∼40 kb 3′ of CYP2A6 in an intron of the adjacent gene, EGLN2 (5) (Fig. 1). rs3733829 genotype is also associated with EGLN2 mRNA expression level (16,17), and correlated SNPs (R2 = 0.39, D′ = 0.93) are GWAS significantly associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (18).

Figure 1.

Relative positions on chromosome 19 of CYP2A6, EGLN2 and RAB4B genes and variants associated with cigarette consumption and related disease in GWAS (5,7,18).

Because of the proximity of EGLN2 to CYP2A6, rs3733829 was assumed to be a proxy for functional genetic variation in CYP2A6 (5,19). A large body of evidence has shown that nicotine metabolism predicts smoking behaviors including cessation (20–27), and variation in hepatic nicotine metabolism is strongly determined by CYP2A6 genotype (14,28). However, as we previously reported, rs3733829 appears to be significantly associated with cigarette consumption independent of CYP2A6 genotype (15). Importantly, rs3733829 is not associated with metabolism of nicotine to cotinine independent of CYP2A6 genotype (15)—i.e. rs3733829 does not appear to account for additional variation in CYP2A6 or otherwise influence nicotine metabolism. rs3733829 is also associated with dichotomous nicotine dependence (19), unlike SNPs in CYP2A6 (15), further evidence that variation in CYP2A6 and EGLN2 affect smoking behaviors via different mechanisms.

Approximately 1.5% of the human genome is transcriptionally responsive to hypoxic conditions (29,30), including carbon monoxide (CO) (31) and cigarette smoke exposure (32). EGLN2 a.k.a. PHD1 a.k.a. hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase (HIF-PH1) is a key component of the cellular oxygen-sensing pathway that regulates the expression of many downstream genes (33–36). EGLN2 is one of three similar genes that act in the hypoxia–response pathway and is widely expressed in tissues including brain, lung and muscle. EGLN gene products respond to hypoxia by acting upon multiple targets (37–40), but primarily they modify the key transcription regulator hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). Under normal conditions the EGLNs hydroxylate prolyl residues on HIFα subunits (HIF1α, 2α or 3α) targeting them for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. EGLN2 is not required for survival (unlike EGLN1) (41) but, uniquely, EGLN2 deficiency causes acute hypoxia tolerance in skeletal muscle and reduced exercise performance due to a shift from oxidative to anaerobic metabolism (42).

Here, we use exhaled CO, a sensitive measure of cigarette consumption highly relevant to hypoxia and disease risk, to evaluate the independent effects of genetic variation in CYP2A6 and EGLN2. Our results indicate hitherto unappreciated GWAS significant associations (5,18) and open up a novel biological pathway to investigation regarding variation in smoking behavior and related disease risk.

RESULTS

The CYP2A6 locus is highly heterogeneous and no single SNP can act as a proxy for CYP2A6 activity. Therefore, in initial analyses we used a predictive model of CYP2A6 activity based on CYP2A6 genotype to capture the genetic diversity of this locus in a single variable, as previously described (15,28). In a single SNP analysis, the EGLN2 SNP rs3733829 is significantly associated with categorical CPD in the University of Wisconsin Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (UW-TTURC) subjects (P = 0.026, β = 0.06 ± 0.03, n = 1395, Table 1). However, it does not remain significantly associated (P = 0.11) in a multivariate model that also includes the CYP2A6 variable, while the CYP2A6 variable itself is strongly associated with CPD in the multivariate model (P = 7.1 × 10−4, β = 0.11 ± 0.03). By comparison, both rs3733829 and the CYP2A6 variable are strongly associated with exhaled CO in single variable analyses (P = 3.8 × 10−5, β = 1.98 ± 0.48 ppm, and P = 2.3 × 10−5, β = 2.07 ± 0.49 ppm, respectively, n = 1355, Table 1) and are independently associated with CO in a multivariate analysis (P = 1.2 × 10−3, β = 1.59 ± 0.49 ppm and P = 3.6 × 10−4, β = 1.77 ± 0.49 ppm respectively, Table 1). rs3733829 also remains significantly associated with CO (P = 1.0 × 10−3, β = 1.69 ± 0.50 ppm) in a multivariate model that includes all of the CYP2A6 reduced function alleles common in Europeans (CYP2A6*1A, *2, *4, *9 and *12) as separate variables (Table 2). This is in contrast to the lack of a significant association between rs3733829 and nicotine metabolism in a parallel multivariate analysis of the previously described nicotine metabolism data (28) in which the CYP2A6 reduced function alleles show large and highly significant associations (Table 3).

Table 1.

Associations between smoking phenotypes and genetic variants at 19q13 in TTURC

| |

CPDa |

COb |

CO/CPDc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2A6d | 1.2 × 10−4 (0.11 ± 0.03) | 2.3 × 10−5 (2.07 ± 0.49) | 0.07 (0.38 ± 0.21) | ||||

| EGLN2e | 0.026 (0.06 ± 0.03) | 3.8 × 10−5 (1.98 ± 0.48) | 5.8 × 10−3 (0.58 ± 0.21) | ||||

| RAB4Bf | 0.18 (0.04 ± 0.03) | 0.011 (1.17 ± 0.46) | 0.06 (0.37 ± 0.20) | ||||

| CYP2A6d | EGLN2e | 7.1 × 10−4 (0.10 ± 0.03) | 0.11 (0.05 ± 0.03) | 3.6 × 10−4 (1.77 ± 0.49) | 1.2 × 10−3 (1.59 ± 0.49) | 0.16 (0.30 ± 0.22) | 0.02 (0.50 ± 0.21) |

| CYP2A6d | RAB4Bf | 2.8 × 10−4 (0.11 ± 0.03) | 0.66 (0.01 ± 0.03) | 1.4 × 10−4 (1.91 ± 0.50) | 0.18 (0.64 ± 0.48) | 0.14 (0.32 ± 0.22) | 0.23 (0.25 ± 0.21) |

| EGLN2e | RAB4Bf | 0.082 (0.06 ± 0.03) | 0.97 (0.00 ± 0.03) | 6.3 × 10−4 (2.06 ± 0.60) | 0.83 (0.12 ± 0.58) | 0.02 (0.59 ± 0.26) | 0.96 (0.01 ± 0.25) |

The statistical significance, P-values, and (effect sizes ± standard error) for associations between phenotypes and genetic variables, when modeled individually or as components of multivariate models including two genetic variables. All models include age, sex and study as covariates.

aSelf-reported cigarettes per day categorized into four levels (CPD ≤ 10, 10 < CPD ≤ 20, 20 < CPD ≤ 30 and CPD > 30) (n = 1395).

bThe mean of two baseline breath CO samples in parts per million (n = 1355).

cThe mean of two baseline breath CO samples in parts per million divided by categorical CPD (CPD ≤ 10 = 1, 10 < CPD ≤ 20 = 2, 20 < CPD ≤ 30 = 3 and CPD > 30 = 4) (n = 1353).

dA continuous variable that captures relative CYP2A6 activity based on diplotype defined by six common variants and gene copy number, as previously described (15,28).

eNumber of rs3733829 minor alleles (0–2).

fNumber of rs7937 major alleles (0–2). Given that the minor allele of rs3733829 usually falls on the major allele of rs7937, rs7937 major alleles were modeled in order to show the consistent direction of effect between the two variants.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of associations between CO and EGLN2/CYP2A6 genotype in TTURC

| Variable | na | MAFb | β ± SEc | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2A6*1A | 523 | 0.19 | −0.48 ± 0.63 | 0.4 |

| CYP2A6*2 | 78 | 0.03 | −2.62 ± 1.43 | 0.1 |

| CYP2A6*4 | 52 | 0.02 | −2.18 ± 1.47 | 0.1 |

| CYP2A6*9 | 204 | 0.08 | −1.15 ± 0.85 | 0.2 |

| CYP2A6*12 | 69 | 0.03 | −3.92 ± 1.49 | 0.008 |

| EGLN2 rs3733829 | 957 | 0.35 | 1.69 ± 0.50 | 0.001 |

Associations between exhaled CO and genetic variables modeled as components of a multivariate model including age, sex and study as covariates in 1355 subjects (2710 chromosomes).

aNumber of minor allele haplotypes.

bMinor allele frequency.

cEffect size ± standard error in ppm.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of associations between nicotine metabolism and EGLN2/CYP2A6 genotype in COGEND

| Variable | na | MAFb | β ± SEc | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2A6*1A | 57 | 0.15 | −0.04 ± 0.01 | 4.6 × 10−6 |

| CYP2A6*2 | 12 | 0.03 | −0.18 ± 0.02 | 4.5 × 10−17 |

| CYP2A6*4 | 6 | 0.02 | −0.21 ± 0.03 | 5.6 × 10−13 |

| CYP2A6*9 | 24 | 0.06 | −0.07 ± 0.01 | 2.5 × 10−6 |

| CYP2A6*12 | 9 | 0.02 | −0.18 ± 0.02 | 3.2 × 10−14 |

| EGLN2 rs3733829 | 137 | 0.36 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.13 |

Associations between the percent of deuterated nicotine metabolized to cotinine in plasma 30 min after oral nicotine administration and genetic variables modeled as components of a multivariate model including age and sex as covariates in 189 subjects (378 chromosomes).

aNumber of minor allele haplotypes.

bMinor allele frequency.

cEffect size ± standard error in the phenotype (cotinine/(cotinine + nicotine)).

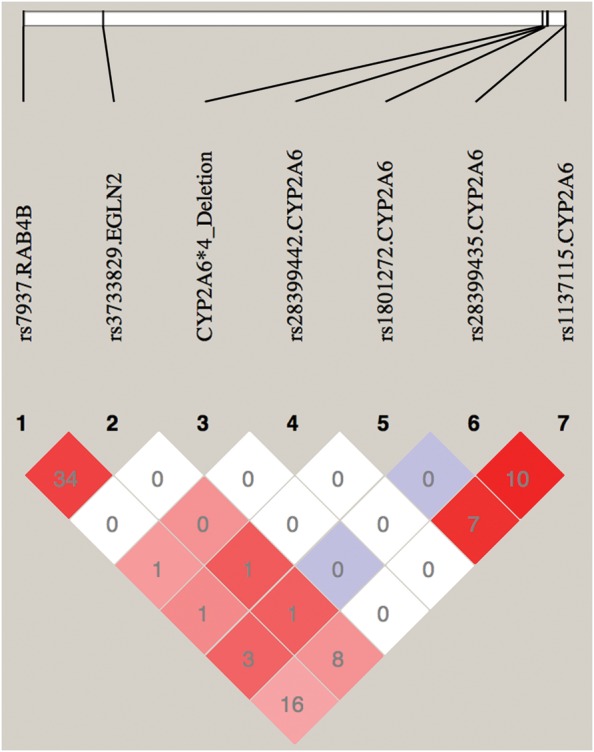

rs7937 (minor allele frequency = 49%), a variant in the 3′ UTR of RAB4B (Fig. 1) in linkage disequilibrium with rs3733829 (R2 = 0.34, D′ = 0.86 in TTURC European Americans, Fig. 2), was also previously identified as GWAS significantly associated with both CPD and COPD (7,18). rs7937 is nominally associated with CO (P = 0.011) in TTURC, but not independent of rs3733829 (P = 0.8, Table 1). rs7937 was not significantly associated with CPD.

Figure 2.

Linkage disequilibrium (R2 and D′) plot of rs3733829 in EGLN2, rs7937 in RAB4B and functional variants in CYP2A6 among TTURC European American Subjects. Numbers represent the R2 value expressed as a percentile. Red squares represent pairs with logarithm of odds (LOD) scores for linkage disequilibrium ≥2 and D′ = 1.0, pink squares represent LOD ≥ 2 and D′ < 1.0, blue squares represent D′ = 1 but LOD < 2, white squares represent LOD < 2 and D′ < 1.0. Plot generated using HaploView v4.2.

The contrast in the associations of rs3733829 with CO and CPD, respectively, led us to investigate a previously used measure of smoking efficiency, CO/CPD (43,44). rs3733829 is significantly associated with CO/CPD (P = 5.8 × 10−3, β = 0.58 ± 0.21 ppm/CPD), as is the key functional SNP in the nicotinic subunit gene CHRNA5, rs16969968 (9), (P = 6.6 × 10−4, β = 0.78 ± 0.21 ppm/CPD). The genotype-predicted CYP2A6 metric is not significantly associated with CO/CPD in these subjects (P = 0.07, Table 1) nor were individual CYP2A6 alleles in a multivariate regression analysis (Table 4); however, the effect sizes for the complete loss-of-function alleles (CYP2A6*2, *4, *12) were consistent with each other (Table 4), and failure to detect a significant association with CO/CPD may be due to lack of power. Power to detect an association with CO/CPD (assuming a minor allele frequency of 3%) was >97% for an effect size of 1.0 ppm/CPD (see Table 4), but only 59% for an effect size of 0.5 ppm/CPD.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of associations between (CO/CPD) and EGLN2/CYP2A6 genotype in TTURC

| Variable | na | MAFb | β ± SEc | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2A6*1A | 521 | 0.19 | 0.14 ± 0.27 | 0.6 |

| CYP2A6*2 | 78 | 0.03 | −0.69 ± 0.62 | 0.3 |

| CYP2A6*4 | 52 | 0.02 | −0.82 ± 0.64 | 0.2 |

| CYP2A6*9 | 204 | 0.08 | 0.03 ± 0.37 | 0.9 |

| CYP2A6*12 | 69 | 0.03 | −0.72 ± 0.65 | 0.3 |

| EGLN2 rs3733829 | 955 | 0.35 | 0.55 ± 0.22 | 0.01 |

Associations between exhaled CO/CPD and genetic variables modeled as components of a multivariate model including age, sex and study as covariates in 1353 subjects (2706 chromosomes).

aNumber of minor allele haplotypes.

bMinor allele frequency.

cEffect size ± standard error in ppm divided by categorical CPD (CPD ≤ 10 = 1, 10 < CPD ≤ 20 = 2, 20 < CPD ≤ 30 = 3 and CPD > 30 = 4).

DISCUSSION

Several candidate pathways have been investigated regarding their influence upon smoking behaviors, but only the nicotinic receptor subunit and nicotine metabolism genes have shown consistent evidence of association (5–7). Unaccounted for heritability in these phenotypes may be due to rare variation or many common variants with very small individual effects; however, our results indicate that detection of important genetic associations may also be impeded by insufficiently investigated genetic complexity, and by the utility of available phenotypes. The chromosomal region 19q13 surrounding CYP2A6 and EGLN2 exemplifies the difficulties encountered in identifying genetic associations with highly polymorphic loci containing many potentially functional variants. It has been hypothesized that significant genetic associations found by genome-wide studies may include ‘synthetic associations’ caused by linkage disequilibrium with multiple less-frequent functional variants in one or more genes (45). We have found this to be the case for SNPs on chromosome 19 identified by large GWAS of smoking behavior (5,7,15). rs3733829, a common SNP in European Americans located in the first exon of EGLN2, ∼40 kb 3′ of CYP2A6, was the SNP most significantly associated with cigarette consumption on chromosome 19 in a large study of European smokers (5). The relations between nicotine metabolism, CYP2A6 genotype and smoking behaviors are well established (20–27), and therefore associations between smoking phenotypes and variants in this region are usually assumed to be proxies for CYP2A6 function (5,7). Only by direct measurement of nicotine metabolism could we make certain that rs3733829 was not associated with further variation in CYP2A6 activity and nicotine metabolism due to unaccounted for variation in CYP2A6 or other nearby genes.

In a previously described experiment, CYP2A6 haplotypes explained >70% of the variance in the metabolism of nicotine to cotinine (15,28). Thus, we possessed substantial power to detect genetic effects on nicotine metabolism. Using CYP2A6 haplotypes as covariates, there was >85% power to detect significant (P < 0.05, n = 189 subjects) effects as small as 2% (0.02 on a scale of 0.0–1.0) and >99% power to detect effects of 3% for hypothetical genetic variants with the same minor allele frequency as rs3733829 (36% in TTURC European American subjects). For comparison, the variable with the smallest effect size in the published genetic model of nicotine metabolism, rs1137115, a synonymous variant that alters CYP2A6 mRNA splicing efficiency(46), has an effect size >0.04 (28). Our inability to detect an independent effect of rs3733829 on nicotine metabolism via this highly sensitive analysis led us to propose that biological differences associated with rs3733829 genotype likely influence smoking behaviors via a novel mechanism unrelated to nicotine metabolism (15), and paved the way to confirm this independent influence using a more suitable phenotype. Thus, our results arise from the convergence of two different approaches to pursuing the biological mechanisms underlying genetic correlates of smoking behavior and associated disease risk: a thorough dissection of the CYP2A6 locus and its influence on nicotine metabolism, and the use of a sensitive and appropriate measure of cigarette consumption and smoke exposure—exhaled CO.

CPD is the most commonly used and easily collected measure of cigarette consumption, but suffers from errors in self-report (47,48) and cannot capture differences in smoking topography, i.e. depth of inhalation, number of puffs per cigarette, etc. As such, correlations between CPD and biomarkers of smoke exposure are modest; CPD explains less than half the variance in saliva levels of the primary metabolite of nicotine, cotinine (49–51), which can vary by greater than an order of magnitude among smokers who report smoking the same number of CPD (50). Breath CO, a byproduct of combustion, has a relatively short half-life (1–4 h (52)) making it sensitive to time of last cigarette (43), but this problem can be reduced by using a check-in process before CO collection to avoid immediate prior smoking, as in this study. CO is significantly correlated with plasma cotinine (53,54) and smoking rate (53,55), and it is more highly correlated with a key biomarker of carcinogen exposure, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (56), than CPD, indicating that CO may capture aspects of smoking behavior relevant to cancer risk that are incompletely reflected through CPD. In this study, CO may also have the advantage of being particularly sensitive to differences in factors associated with hypoxia response, which might be more likely to influence smoking topography than smoking frequency (CPD).

CO is a measure of total smoke exposure; it essentially sums all factors contributing to exposure including number of cigarettes consumed (CPD) and the efficiency with which they are consumed (reflecting differences in smoking topography: number of puffs per cigarettes, depth of inhalation, etc.). By using CO/CPD, we have attempted to examine the efficiency of smoking as it is defined on the basis of yield of CO/cigarette smoked. This permits a rough distinction between factors that drive the frequency of smoking versus those that determine the smoking intensity, which has been related to tobacco dependence and withdrawal magnitude (57–59). It has been argued that variation in the nicotinic receptor gene CHRNA5 influences cancer risk via pathways other than those that mediate changes in smoking behavior (60–62), because the association between variation in CHRNA5 and lung cancer is largely independent of CPD. Our results are not conclusive as to whether greater CYP2A6 activity and the shorter nicotine half-life experienced by faster metabolizers is compensated for through greater smoking efficiency, i.e. higher CO per cigarette, and further studies using direct measures of smoking topography are necessary, but our data suggest how loci such as CHRNA5 (62–64) or EGLN2 can significantly influence exposure to the carcinogens in tobacco smoke while only nominally affecting CPD. These observations argue strongly in favor of CO or similar biomarkers as worthwhile adjuncts to CPD to measure smoking behavior relevant to cancer risk.

The clear demonstration of an association between smoking intensity and EGLN2, a hypoxia sensor upstream of a large portion of the human transcriptome (29,30), invites further investigation of this pathway and the mechanism underlying its genetic association. rs3733829 has been reported to be associated with EGLN2 mRNA levels in monocytes and lymphocytes (16,17). Bioinformatic tools do not predict a clear functional consequence of rs3733829 or other tightly linked SNPs; however, multiple SNPs in high LD with rs3733829 occur in the 5′UTR or promoter region and may impact EGLN2 transcription. Further studies will be necessary to determine the specific mechanisms by which polymorphisms in EGLN2 alter gene function. That the effect of this genetic variation is strong enough to be detected through a complex behavioral phenotype also indicates that this variation may be associated with robust differences in general cellular hypoxia response. Such differences may also affect other important processes such as wound healing, tumor growth or ischemia recovery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study complies with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association. The University of Wisconsin-Madison and Washington University Human Studies Independent Review Boards approved these studies (approval number for Collaborative Genetic Study of Nicotine Dependence (COGEND) is 00-0203), and all subjects provided written informed consent. Subjects were recruited from three UW-TTURC randomized, placebo-controlled smoking cessation trials, ‘Dependence’(65), ‘Ed.Sr’(66) and ‘TTURC 2′ (67). All subjects analyzed were of European descent, at least 18 years of age, and smoked 10 or more CPD. TTURC participants completed baseline assessments of demographics, smoking history (including CPD) and tobacco dependence measured by the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (68), and provided breath samples for alveolar CO analysis (67). Baseline CO was collected prior to the use of any smoking cessation pharmacotherapy and prior to the quit attempt, and participants had received no instruction to cut down or modify their smoking prior to sample collection. One CO sample was analyzed from TTURC 2 study subjects and the mean of two samples collected on the same day was analyzed for the Dependence and Ed.Sr study subjects (overall mean CO for all subjects = 26.6 ± 12.3, range = 1110 ppm). CO samples were collected using standard assessment methods for smoking cessation clinical trials (69–72) and occurred after a check-in process that entailed a delay between smoking and CO collection to reduce distortion by immediate smoking. CPD was collected and analyzed as a four-level categorical variable (CPD ≤ 10, 10 < CPD ≤ 20, 20 < CPD ≤ 30 and CPD>30) as in previous studies (69). To calculate CO/CPD, a measure of smoking efficiency (43,44), the four CPD categories were coded as 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively.

The COGEND is a multisite project in the United States (12). The 189 subjects analyzed here were self-identified as being of European American ancestry, and race was previously verified using EIGENSTRAT (70). Sample demographics were previously described (8,12).

Genome-wide genotyping in TTURC was performed by the Center for Inherited Disease Research at Johns Hopkins University using the Illumina Omni2.5 microarray (www.illumina.com). Data cleaning was led by the GENEVA Coordinating Center at the University of Washington. Additional genotyping and gene copy number determination in the CYP2A6 locus was performed using a Taqman copy number assay (Hs00010002_cn, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and custom designed Sequenom MassARRAY (Sequenom, San Diego CA, USA) and KASPar (KBioscience, Hoddesdon, Herts, UK) assays, as previously described (28). The predictive model of CYP2A6 activity based on CYP2A6 genotype was utilized to generate a continuous variable metric of nicotine metabolism for each subject, as previously described (15,28).

Association analyses were performed in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with sex, age and study as covariates, in genotyped subjects with available measures of CO or CPD. Power calculations were performed using Quanto 1.1 (71) LD was determined and LD plot generated using HaploView v4.2 (72).

FUNDING

The National Institute of Mental Health (5T32MH014677-33 to A.J.B.); the National Cancer Institute (P01 CA-089392 to L.J.B., and P50 CA-84724 and K05 CA-139871 to T.B.B.); the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K02 DA-021237 to L.J.B.) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01 HG-004422 to L.J.B.). Funding support for genotyping, which was performed at the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR), was provided by X01 HG005274-01. CIDR is fully funded through a federal contract from the National Institutes of Health to The Johns Hopkins University, contract number HHSN268200782096C. Assistance with genotype cleaning, as well as with general study coordination, was provided by the Gene Environment Association Studies (GENEVA) Coordinating Center (U01 HG004446). Funding support for collection of datasets and samples was provided by the Collaborative Genetic Study of Nicotine Dependence (COGEND; P01 CA089392) and the University of Wisconsin Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (P50 DA019706, P50 CA084724). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank and mention the following: The Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene provided considerable technical assistance in the form of DNA extraction. Research was also aided by the Wisconsin Partnership Program. Medication was provided to patients at no cost under a research agreement with GlaxoSmithKline. Investigators directing data collection for COGEND are Laura Bierut, Naomi Breslau, Dorothy Hatsukami and Eric Johnson; data management are organized by Nancy Saccone and John Rice; laboratory analyses are led by Alison Goate; data collection were supervised by Tracey Richmond.

Conflict of Interest statement. Drs. Goate and Bierut are listed as inventors on a patent (US 20070258898) covering the use of certain SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of addiction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mokdad A.H., Marks J.S., Stroup D.F., Gerberding J.L. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan P.F., Kendler K.S. The genetic epidemiology of smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 1999;1(Suppl. 2):S51–57. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011811. discussion S69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M.D. The genetics of smoking related behavior: a brief review. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2003;326:168–173. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koopmans J.R., Slutske W.S., Heath A.C., Neale M.C., Boomsma D.I. The genetics of smoking initiation and quantity smoked in Dutch adolescent and young adult twins. Behav. Genet. 1999;29:383–393. doi: 10.1023/a:1021618719735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genome-wide meta-analyses identify multiple loci associated with smoking behavior. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:441–447. doi: 10.1038/ng.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorgeirsson T.E., Geller F., Sulem P., Rafnar T., Wiste A., Magnusson K.P., Manolescu A., Thorleifsson G., Stefansson H., Ingason A., et al. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature. 2008;452:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature06846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorgeirsson T.E., Gudbjartsson D.F., Surakka I., Vink J.M., Amin N., Geller F., Sulem P., Rafnar T., Esko T., Walter S., et al. Sequence variants at CHRNB3-CHRNA6 and CYP2A6 affect smoking behavior. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:448–453. doi: 10.1038/ng.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saccone S.F., Hinrichs A.L., Saccone N.L., Chase G.A., Konvicka K., Madden P.A., Breslau N., Johnson E.O., Hatsukami D., Pomerleau O., et al. Cholinergic nicotinic receptor genes implicated in a nicotine dependence association study targeting 348 candidate genes with 3713 SNPs. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:36–49. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bierut L.J., Stitzel J.A., Wang J.C., Hinrichs A.L., Grucza R.A., Xuei X., Saccone N.L., Saccone S.F., Bertelsen S., Fox L., et al. Variants in nicotinic receptors and risk for nicotine dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:1163–1171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L.S., Baker T.B., Piper M.E., Breslau N., Cannon D.S., Doheny K.F., Gogarten S.M., Johnson E.O., Saccone N.L., Wang J.C., et al. Interplay of genetic risk factors (CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4) and cessation treatments in smoking cessation success. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2012;169:735–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freathy R.M., Ring S.M., Shields B., Galobardes B., Knight B., Weedon M.N., Smith G.D., Frayling T.M., Hattersley A.T. A common genetic variant in the 15q24 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene cluster (CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4) is associated with a reduced ability of women to quit smoking in pregnancy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:2922–2927. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bierut L.J., Madden P.A., Breslau N., Johnson E.O., Hatsukami D., Pomerleau O.F., Swan G.E., Rutter J., Bertelsen S., Fox L., et al. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:24–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malaiyandi V., Sellers E.M., Tyndale R.F. Implications of CYP2A6 genetic variation for smoking behaviors and nicotine dependence. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;77:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benowitz N.L., Swan G.E., Jacob P., 3rd, Lessov-Schlaggar C.N., Tyndale R.F. CYP2A6 genotype and the metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;80:457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloom A.J., Harari O., Martinez M., Madden P.A., Martin N.G., Montgomery G.W., Rice J.P., Murphy S.E., Bierut L.J., Goate A. Use of a predictive model derived from in vivo endophenotype measurements to demonstrate associations with a complex locus, CYP2A6. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3050–3062. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeller T., Wild P., Szymczak S., Rotival M., Schillert A., Castagne R., Maouche S., Germain M., Lackner K., Rossmann H., et al. Genetics and beyond – the transcriptome of human monocytes and disease susceptibility. PloS ONE. 2010;5:e10693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goring H.H., Curran J.E., Johnson M.P., Dyer T.D., Charlesworth J., Cole S.A., Jowett J.B., Abraham L.J., Rainwater D.L., Comuzzie A.G., et al. Discovery of expression QTLs using large-scale transcriptional profiling in human lymphocytes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ng2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho M.H., Castaldi P.J., Wan E.S., Siedlinski M., Hersh C.P., Demeo D.L., Himes B.E., Sylvia J.S., Klanderman B.J., Ziniti J.P., et al. A genome-wide association study of COPD identifies a susceptibility locus on chromosome 19q13. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:947–957. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L.S., Baker T.B., Grucza R., Wang J.C., Johnson E.O., Breslau N., Hatsukami D., Smith S.S., Saccone N., Saccone S., et al. Dissection of the phenotypic and genotypic associations with nicotinic dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012;14:425–433. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho M.K., Tyndale R.F. Overview of the pharmacogenomics of cigarette smoking. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:81–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malaiyandi V., Goodz S.D., Sellers E.M., Tyndale R.F. CYP2A6 genotype, phenotype, and the use of nicotine metabolites as biomarkers during ad libitum smoking. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1812–1819. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malaiyandi V., Lerman C., Benowitz N.L., Jepson C., Patterson F., Tyndale R.F. Impact of CYP2A6 genotype on pretreatment smoking behaviour and nicotine levels from and usage of nicotine replacement therapy. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:400–409. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benowitz N.L., Pomerleau O.F., Pomerleau C.S., Jacob P., 3rd Nicotine metabolite ratio as a predictor of cigarette consumption. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:621–624. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerman C., Jepson C., Wileyto E.P., Patterson F., Schnoll R., Mroziewicz M., Benowitz N., Tyndale R.F. Genetic variation in nicotine metabolism predicts the efficacy of extended-duration transdermal nicotine therapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010;87:553–557. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson F., Schnoll R.A., Wileyto E.P., Pinto A., Epstein L.H., Shields P.G., Hawk L.W., Tyndale R.F., Benowitz N., Lerman C. Toward personalized therapy for smoking cessation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial of bupropion. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;84:320–325. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnoll R.A., Patterson F., Wileyto E.P., Tyndale R.F., Benowitz N., Lerman C. Nicotine metabolic rate predicts successful smoking cessation with transdermal nicotine: a validation study. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2009;92:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benowitz N.L., Jacob P., 3rd, Fong I., Gupta S. Nicotine metabolic profile in man: comparison of cigarette smoking and transdermal nicotine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bloom J., Hinrichs A.L., Wang J.C., von Weymarn L.B., Kharasch E.D., Bierut L.J., Goate A., Murphy S.E. The contribution of common CYP2A6 alleles to variation in nicotine metabolism among European-Americans. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2011;21:403–416. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328346e8c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koong A.C., Denko N.C., Hudson K.M., Schindler C., Swiersz L., Koch C., Evans S., Ibrahim H., Le Q.T., Terris D.J., et al. Candidate genes for the hypoxic tumor phenotype. Cancer Res. 2000;60:883–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denko N.C., Fontana L.A., Hudson K.M., Sutphin P.D., Raychaudhuri S., Altman R., Giaccia A.J. Investigating hypoxic tumor physiology through gene expression patterns. Oncogene. 2003;22:5907–5914. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi Y.K., Kim C.K., Lee H., Jeoung D., Ha K.S., Kwon Y.G., Kim K.W., Kim Y.M. Carbon monoxide promotes VEGF expression by increasing HIF-1alpha protein level via two distinct mechanisms, translational activation and stabilization of HIF-1alpha protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:32116–32125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu H., Li Q., Kolosov V.P., Perelman J.M., Zhou X. Regulation of cigarette smoke-mediated mucin expression by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha via epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated signaling pathways. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2011;32:282–292. doi: 10.1002/jat.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greer S.N., Metcalf J.L., Wang Y., Ohh M. The updated biology of hypoxia-inducible factor. EMBO J. 2012;31:2448–2460. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majmundar A.J., Wong W.J., Simon M.C. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webb J.D., Coleman M.L., Pugh C.W. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF), HIF hydroxylases and oxygen sensing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:3539–3554. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metzen E., Ratcliffe P.J. HIF hydroxylation and cellular oxygen sensing. Biol. Chem. 2004;385:223–230. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q., Gu J., Li L., Liu J., Luo B., Cheung H.W., Boehm J.S., Ni M., Geisen C., Root D.E., et al. Control of cyclin D1 and breast tumorigenesis by the EglN2 prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cummins E.P., Berra E., Comerford K.M., Ginouves A., Fitzgerald K.T., Seeballuck F., Godson C., Nielsen J.E., Moynagh P., Pouyssegur J., et al. Prolyl hydroxylase-1 negatively regulates IkappaB kinase-beta, giving insight into hypoxia-induced NFkappaB activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18154–18159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siddiq A., Aminova L.R., Troy C.M., Suh K., Messer Z., Semenza G.L., Ratan R.R. Selective inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl-hydroxylase 1 mediates neuroprotection against normoxic oxidative death via HIF- and CREB-independent pathways. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:8828–8838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1779-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson K., Nordquist K.A., Gao X., Hicks K.C., Zhai B., Gygi S.P., Patel T.B. Regulation of cellular levels of Sprouty2 protein by prolyl hydroxylase domain and von Hippel-Lindau proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:42027–42036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.303222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeda K., Ho V.C., Takeda H., Duan L.J., Nagy A., Fong G.H. Placental but not heart defects are associated with elevated hypoxia-inducible factor alpha levels in mice lacking prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:8336–8346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00425-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aragones J., Schneider M., Van Geyte K., Fraisl P., Dresselaers T., Mazzone M., Dirkx R., Zacchigna S., Lemieux H., Jeoung N.H., et al. Deficiency or inhibition of oxygen sensor Phd1 induces hypoxia tolerance by reprogramming basal metabolism. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:170–180. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho M.K., Faseru B., Choi W.S., Nollen N.L., Mayo M.S., Thomas J.L., Okuyemi K.S., Ahluwalia J.S., Benowitz N.L., Tyndale R.F. Utility and relationships of biomarkers of smoking in African-American light smokers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3426–3434. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frei M., Engel Brugger O., Sendi P., Reichart P.A., Ramseier C.A., Bornstein M.M. Assessment of smoking behaviour in the dental setting. A study comparing self-reported questionnaire data and exhaled carbon monoxide levels. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012;16:755–760. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0583-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dickson S.P., Wang K., Krantz I., Hakonarson H., Goldstein D.B. Rare variants create synthetic genome-wide associations. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloom A.J., Harari O., Martinez M., Zhang X., McDonald S.A., Murphy S.E., Goate A. A compensatory effect upon splicing results in normal function of the CYP2A6*14 allele. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2013 doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835caf7d. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krall E.A., Valadian I., Dwyer J.T., Gardner J. Accuracy of recalled smoking data. Am. J. Public Health. 1989;79:200–202. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vesey C.J., Saloojee Y., Cole P.V., Russell M.A. Blood carboxyhaemoglobin, plasma thiocyanate, and cigarette consumption: implications for epidemiological studies in smokers. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1982;284:1516–1518. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6328.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Etter J.F., Perneger T.V. Measurement of self reported active exposure to cigarette smoke. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2001;55:674–680. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.9.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Etter J.F., Vu Duc T., Perneger T.V. Saliva cotinine levels in smokers and nonsmokers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000;151:251–258. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perez-Stable E.J., Benowitz N.L., Marin G. Is serum cotinine a better measure of cigarette smoking than self-report? Prev. Med. 1995;24:171–179. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scherer G. Carboxyhemoglobin and thiocyanate as biomarkers of exposure to carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide in tobacco smoke. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2006;58:101–124. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Domino E.F., Ni L. Clinical phenotyping strategies in selection of tobacco smokers for future genotyping studies. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psych. 2002;26:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marrone G.F., Paulpillai M., Evans R.J., Singleton E.G., Heishman S.J. Breath carbon monoxide and semiquantitative saliva cotinine as biomarkers for smoking. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:80–83. doi: 10.1002/hup.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood T., Wewers M.E., Groner J., Ahijevych K. Smoke constituent exposure and smoking topography of adolescent daily cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:853–862. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000282537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Joseph A.M., Hecht S.S., Murphy S.E., Carmella S.G., Le C.T., Zhang Y., Han S., Hatsukami D.K. Relationships between cigarette consumption and biomarkers of tobacco toxin exposure. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2963–2968. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arndt J., Vail K.E., 3rd, Cox C.R., Goldenberg J.L., Piasecki T.M., Gibbons F.X. The interactive effect of mortality reminders and tobacco craving on smoking topography. Health Psychol. 2013;32:525–532. doi: 10.1037/a0029201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perkins K.A., Karelitz J.L., Giedgowd G.E., Conklin C.A. The reliability of puff topography and subjective responses during ad lib smoking of a single cigarette. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012;14:490–494. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stewart D.W., Vinci C., Adams C.E., Cohen A.S., Copeland A.L. Smoking topography and outcome expectancies among individuals with schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2013;205:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hung R.J., McKay J.D., Gaborieau V., Boffetta P., Hashibe M., Zaridze D., Mukeria A., Szeszenia-Dabrowska N., Lissowska J., Rudnai P., et al. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature. 2008;452:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature06885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amos C.I., Wu X., Broderick P., Gorlov I.P., Gu J., Eisen T., Dong Q., Zhang Q., Gu X., Vijayakrishnan J., et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:616–622. doi: 10.1038/ng.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.VanderWeele T.J., Asomaning K., Tchetgen Tchetgen E.J., Han Y., Spitz M.R., Shete S., Wu X., Gaborieau V., Wang Y., McLaughlin J., et al. Genetic variants on 15q25.1, smoking, and lung cancer: an assessment of mediation and interaction. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012;175:1013–1020. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Le Marchand L., Derby K.S., Murphy S.E., Hecht S.S., Hatsukami D., Carmella S.G., Tiirikainen M., Wang H. Smokers with the CHRNA lung cancer-associated variants are exposed to higher levels of nicotine equivalents and a carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamine. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9137–9140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wassenaar C.A., Dong Q., Wei Q., Amos C.I., Spitz M.R., Tyndale R.F. Relationship between CYP2A6 and CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 variation and smoking behaviors and lung cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1342–1346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piper M.E., Federman E.B., McCarthy D.E., Bolt D.M., Smith S.S., Fiore M.C., Baker T.B. Efficacy of bupropion alone and in combination with nicotine gum. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2007;9:947–954. doi: 10.1080/14622200701540820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCarthy D.E., Piasecki T.M., Lawrence D.L., Jorenby D.E., Shiffman S., Fiore M.C., Baker T.B. A randomized controlled clinical trial of bupropion SR and individual smoking cessation counseling. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008;10:717–729. doi: 10.1080/14622200801968343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piper M.E., Smith S.S., Schlam T.R., Fiore M.C., Jorenby D.E., Fraser D., Baker T.B. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:1253–1262. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heatherton T.F., Kozlowski L.T., Frecker R.C., Fagerstrom K.O. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saccone N.L., Saccone S.F., Hinrichs A.L., Stitzel J.A., Duan W., Pergadia M.L., Agrawal A., Breslau N., Grucza R.A., Hatsukami D., et al. Multiple distinct risk loci for nicotine dependence identified by dense coverage of the complete family of nicotinic receptor subunit (CHRN) genes. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2009;150B:453–466. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saccone N.L., Wang J.C., Breslau N., Johnson E.O., Hatsukami D., Saccone S.F., Grucza R.A., Sun L., Duan W., Budde J., et al. The CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 nicotinic receptor subunit gene cluster affects risk for nicotine dependence in African-Americans and in European-Americans. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6848–6856. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gauderman W., Morrison J. Quanto 1.1: a computer program for power and sample size calculations for genetic-epidemiology studies. 2006 http://hydra.Usc.Edu/gxe . [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barrett J.C., Fry B., Maller J., Daly M.J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]