Abstract

Aims: There is mounting evidence that the transition metal copper may play an important role in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Triethylene tetramine dihydrochloride (trientine), a CuII-selective chelator, is a commonly used treatment for Wilson's disease to decrease accumulated copper, and thereby decreases oxidative stress. In the present study, we evaluated the effects of a 3-month treatment course of trientine (Trien) on amyloidosis in 7-month-old β-amyloid (Aβ) precursor protein and presenilin-1 (APP/PS1) double transgenic (Tg) AD model mice. Results: We observed that Trien reduced the level of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and decreased Aβ deposition and synapse loss in brain of APP/PS1 mice. Importantly, we found that Trien blocked the receptor for AGEs (RAGE), downregulated β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), inhibited amyloidogenic APP cleavage, and subsequently reduced Aβ levels. In vitro, in SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing Swedish mutant APP, Trien-mediated downregulation of BACE1 occurred via inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Innovation: In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that Trien inhibited amyloidogenic pathway including targeting the downregulation of RAGE and NF-κB. Conclusion: Trien might mitigate amyloidosis in AD by inhibiting the RAGE/NF-κB/BACE1 pathway. Our study demonstrates that Trien may be a viable therapeutic strategy for the intervention and treatment of AD and other AD-like pathologies. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 2024–2039.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and is characterized by progressively debilitating cognitive and memory impairment. The two major neuropathological hallmarks of AD are extracellular amyloid plaques composed of aggregated, fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide, and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of aggregated hyperphosphorylated tau protein (67, 69, 73). Sequential endoproteolytic cleavage of Aβ precursor protein (APP) by type 1 transmembrane protein β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) and the γ-secretase complex yield two major Aβ C-terminal variants, Aβ peptide 1–40 and Aβ1 peptide 1–42 (68, 74). Primarily, it is the low molecular weight Aβ oligomers that exhibit the greatest neurotoxicity, yielding the formation of Aβ aggregates (70, 75).

Many studies suggest that excessive oxidative stress is a common pathogenic mechanism underlying the onset of AD (49, 60). In AD, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids within the hippocampus and cortex exhibit high levels of oxidative modification. These include a complex array of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and advanced lipoxidation end products generated through glycoxidations and lipid peroxidations, respectively (11, 13). The receptor for AGE (RAGE) binds Aβ strands and is overexpressed in the degenerated hippocampi and frontal lobes of AD patients (47). Interestingly, AGE formation has been shown to promote Aβ covalent cross-linking (54) via a process that is accelerated by trace amounts of the transition metal ions, copper (Cu) and iron (Fe) (44). Cu, a redox-active metal, is intimately involved in the pathogenesis of AD (31). Cu and zinc (Zn) localize with Aβ in senile plaques (29, 57), and Cu and Fe promote the neurotoxic redox activity of Aβ to induce oxidative cross-linking of the peptide into stable oligomers (4, 10, 30, 50). The β secretase BACE1 possesses a Cu binding site, which implies that copper levels may impact Aβ generation directly via its synthetic pathway (1). Postmortem studies revealed that Cu, Fe, and Zn are significantly elevated in and around the Aβ plaques in AD brain (9, 45, 61) and in AD transgenic (Tg) mouse brain (42, 51). Drugs such as anti-redox species are potential therapeutic implications on AD (20). Indeed, metal chelators reduce the cerebral Aβ deposits in the AD Tg mouse brain (18). Therefore, it follows that therapeutic interventions that decrease Aβ production or oxidative stress by modulating copper availability may reduce the vulnerability to amyloidosis in AD.

Innovation.

Trien has recently been identified as a multifunctional molecule, which was previously approved as an agent for Wilson's disease. Until now, the effects of Trien on Alzheimer's disease (AD) in vivo have not been investigated. We show for the first time that Trien treatment reduces β-amyloid (Aβ) production and deposition, and it leads to decrease of AGE in AD transgenic mouse model. Moreover, we showed that Trien downregulates β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) in vivo and in vitro, by inhibiting the AGE/RAGE/NF-κB signal pathway. In conclusion, our findings provide the first evidence that Trien treatment reverses specific AD phenotypes and may be an effective clinical treatment for AD.

NF-κB, a family of homo- and hetero-dimeric transcription factors, regulates the transcription of a number of genes in response to infection, inflammation, and DNA damage (38). NF-κB activity has been shown to increase with age (12). NF-κB dysregulation has been implicated in diverse human pathologies (14). In AD postmortem brain, NF-κB is found in neurons, neurofibrillary tangles, and dystrophic neurites (72), and it is activated by Aβ specifically in neurons surrounding plaques (40). Aβ-mediated transactivation of the BACE1 promoter involved the NF-κB pathway (8). In addition, RAGE activation upregulates BACE1 expression via activation of NF-κB (35). Interestingly, it was recently reported that NF-κB DNA-binding activity and expression of various NF-κB target genes were found to be increased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from AD patients (3). Taken together, these findings identify NF-κB as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of AD.

Wilson's disease is an inherited disorder due to mutations in the gene encoding an ATPase copper pump that is necessary for the secretion of copper into bile (33, 56). Copper accumulation in tissues (especially in liver, brain, and eye) promotes free radical formation and oxidative damage (33, 56). Triethylene tetramine dihydrochloride (trientine), a CuII-selective chelator, is commonly used for the second-line treatment of Wilson's disease to remove excess extracellular Cu (76). There is some evidence that trientine (Trien) may be effective for treatment of cancer (43, 53) and several type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)-associated conditions, including cardiomyopathy (5), neuropathy (16, 55), and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (23). Long-term Trien treatment has not been shown to alter the balance of any other element in either diabetic or control subjects (24). Mechanistically, chronic Trien treatment may promote remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins by decreasing the AGE content of collagen (24). Whether long-term Trien administration can suppress or reverse AGE formation remains to be determined.

There are several lines of evidence that suggest a link between the pathogenesis of T2DM and AD (39, 46, 65). AD exhibited the altered glucose tolerance and metabolism [reviewed by Calabrese et al. (15)]. In a carefully controlled community study, it was found that more than 80% of an unselected group of AD patients had either T2DM or dysglycemia (39). Both disorders display elevated copper levels that generate CuII-mediated oxidative stress (22) and elevated AGEs. In T2DM patients, Trien has been shown to be a safe and efficient treatment (22). In postmortem AD tissues and APP-C100 Tg AD model mice, Trien mobilized Aβ from the sedimental to the soluble fraction (19). However, to date, there exists no comprehensive description of the effects of Trien on AD in vivo.

In the present study, we evaluated the effects of Trien on neuropathology in APP/presenilin-1 (PS1) double Tg mouse model of AD and identified its underlying mechanism. We observed that Trien reduced BACE1 activity and mitigated amyloidosis via the AGEs/RAGE/NF-κB pathway in both AD Tg mice and SH-SY5Y cell line stably overexpressing human APP Swedish mutation (APPsw) in vitro. Our data suggest that Trien might be a potential therapeutic strategy for the prevention and treatment of AD.

Results

Total copper, iron, and zinc levels in the serum and brain of APP/PS1 Tg mice are unaltered following Trien administration

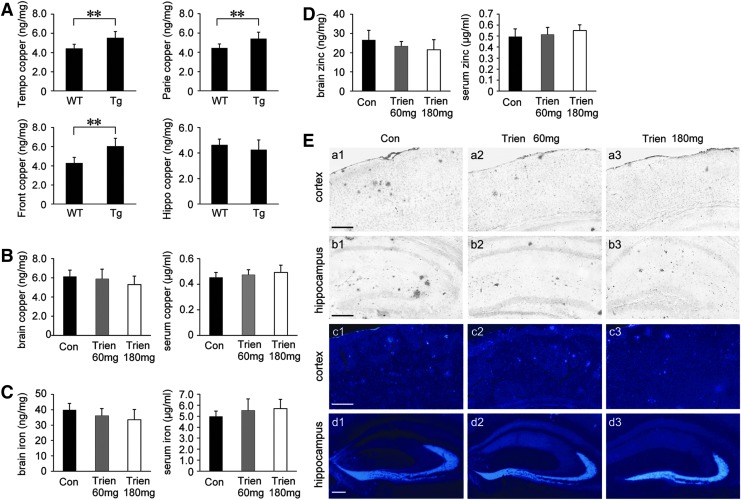

Based on the fact that dyshomeostasis of copper is a characteristic of AD (9, 45), we first determine copper levels in the brain of Tg APP/PS1 mice and age-matched wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice. As shown in Figure 1A, atomic absorption spectrum analysis revealed that copper levels were statistically increased in the temporal, parietal, and frontal cortex of Tg mice compared with WT group. There was no statistical difference in the copper level in the hippocampus although there was a trend toward a decrease in the Tg group compared with the WT group.

FIG. 1.

Assessment of metal levels (copper, iron, and zinc). (A) Copper level in the temporal cortex (Tempo), parietal cortex (Parie), frontal cortex (Front), and hippocampus (Hippo) of 7-month-old transgenic (Tg) amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 (APP/PS1) mice and age-matched wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice. (B–D) APP/PS1 mice were treated with vehicle control (Con, 0.9% physiological saline) or Trien at dose of 60 mg/kg/day (Trien 60 mg) or 180 mg/kg/day (Trien 180 mg) by gavage for 3 months. Atomic absorption spectrum assays showed that there were no statistically significant differences in the copper content either in the brain or in the serum under Trien treatment compared with the vehicle group (B). No alterations were observed in the brain iron and serum iron contents in Trien-treated APP/PS1 compared with the control group (C). Assays of zinc content indicated that Trien administration did not alter the zinc levels in the brain nor in the serum of the APP/PS1 mouse (D). (E) Silver autometallography and N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluenesulfonamide (TSQ) stains respectively showed the distribution of copper (cortex, a1–b3; hippocampus, b1–b3) and zinc (cortex, c1–c3; hippocampus, d1–d3) in the APP/PS1 mouse brain. Scale bar=200 μm. Values are represented as mean±SEM (n=6). **p<0.01 versus the Tg group (Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) post hoc Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD).

Following a 3-month treatment regimen with either Trien or vehicle, the levels of copper, iron, and zinc were measured in the serum and brain of APP/PS1 mice. There were no statistically significant differences in the level of copper, iron, or zinc in either serum or brain between vehicle- and Trien-treated groups (p>0.05; Fig. 1B–D).

We then stained brain sections by silver autometallography and a zinc-specific fluorescent dye, N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluenesulfonamide (TSQ) to evaluate the distribution of copper and zinc, respectively. Trien treatment reduced copper accumulation in the plaques of the APP/PS1 mouse brain (Fig. 1E, a1–b3). TSQ-fluorescence in plaques of Trien-treated group was significantly diminished (Fig. 1E, c1–d3).

Over the course of treatment, we observed no major behavioral abnormalities or gross motor defects in Trien-treated APP/PS1 mice relative to vehicle control. Trien treatment did not significantly affect body weight of APP/PS1 mice (data not shown).

Copper transporter 1, copper-transporting adenosine triphosphatases, and ceruloplasmin activity are unaffected following Trien administration in APP/PS1 Tg mouse brain, whereas superoxide dismutase 1 activity is elevated and malondialdehyde contents are reduced

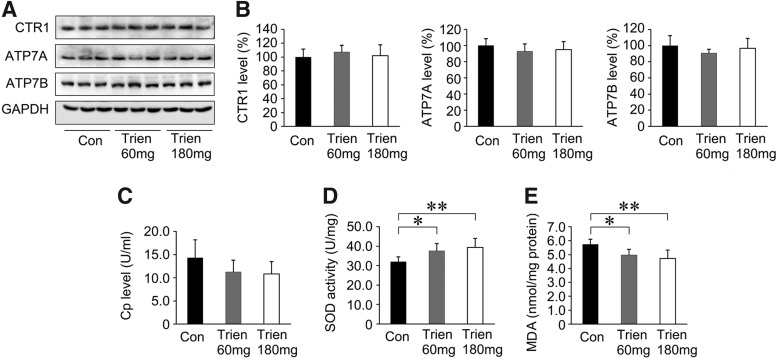

Protein levels of copper transporter 1 (CTR1), ATP7A, and ATP7B (Fig. 2A, B) or ceruloplasmin (Cp) activity (Fig. 2C) in the Trien treatment group was unaltered relative to vehicle control (p>0.05). Trien administration in APP/PS1 mouse brain did enhance superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) activity relative to vehicle [F(2,15)=6.08; p<0.05]. SOD activity was increased to 117.13%±12.09% of control (60 mg/kg; 37.51±3.87 U/mg vs. 32.02±2.57 U/mg; p<0.05; Fig. 2D) and 122.93%±14.51% of control (180 mg/kg; 39.37±4.64 vs. 32.02±2.57 U/mg; p<0.01; Fig. 2D). The malondialdehyde (MDA) contents were significantly reduced under Trien treatment [F(2,15)=6.80; p<0.01]. The MDA level was reduced to 86.75%±7.41% of control (60 mg/kg; 4.97±0.42 nmol/mg vs. 5.72±0.39 nmol/mg; p<0.05; Fig. 2E) and 82.56%±10.85% of control (180 mg/kg; 4.73±0.62 nmol/mg vs. 5.72±0.39 nmol/mg; p<0.01; Fig. 2E).

FIG. 2.

Effects of Trien treatment on copper transport protein, ceruloplasmin (Cp), superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) activity, and MDA production. (A) Western blotting showed the protein expression levels of copper transporter 1 (CTR1), ATP7A, and ATP7B in the vehicle- and Trien-treated APP/PS1 mouse brain. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (B) Trien treatment did not significantly alter the protein levels of CTR1, ATP7A, and ATP7B in the APP/PS1 mice brain. (C) Trien administration did not affect Cp activity. (D) Trien treatment dose-dependently enhanced SOD1 activity in the cortex of APP/PS1 mice brain compared with control group. (E) Trien markedly reduced the production of MDA in the APP/PS1 mouse brain. All values are mean±SEM (n=6). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus the control group (one-way ANOVA post hoc Fisher's PLSD).

Trien treatment inhibited Aβ generation and deposition, and reduced synapse loss in APP/PS1 mouse brain

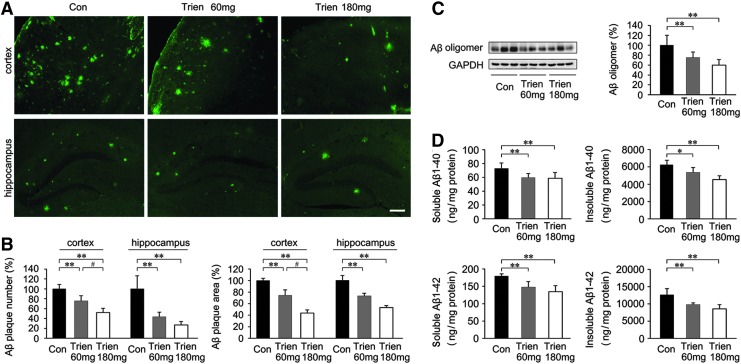

To investigate the effects of Trien on amyloidosis in APP/PS1 mouse brain, we compared the level of Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, Aβ oligomer, and Aβ plaques between the Trien-treated group and the control group. Immunofluorescence indicated that Aβ plaque formation was reduced in the brains from the Trien-treated group relative to vehicle controls (Fig. 3A, B). Quantification showed that Trien treatment significantly reduced the number and size of Aβ plaques in the cortex and hippocampus of APP/PS1 mouse brain. The number of Aβ-positive plaques in the cortex was reduced to 75.56%±10.59% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 51.99%±8.87% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01) [F(2,15)=36.92; p<0.01], and in the hippocampus it was reduced to 43.21%±9.82% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 26.70%±7.14% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01) [F(2,15)=31.85; p<0.01]. The immunoreactive area of Aβ plaques in Trien-treated groups were reduced in the cortex to 74.61%±9.10% (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 43.79%±5.59% (180 mg/kg; p<0.01) [F(2,15)=109.42; p<0.001], and were reduced in the hippocampus to 73.25%±4.48% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 53.17%±3.58% (180 mg/kg; p<0.01) [F(2,15)=92.63; p<0.01] of control.

FIG. 3.

Effects of Trien administration on Aβ generation and Aβ plaque deposition in APP/PS1 mouse brain. (A) Fluorescent labeling of Aβ showing the Aβ plaques in the cortex and hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice brain in the vehicle control group and Trien-treated groups at doses of 60 mg/kg and 180 mg/kg, respectively. (B) Quantification of fluorescence indicated that Trien administration significantly reduced Aβ plaques number and area, both in the cortex and in the hippocampus. Scale bar=100 μm. (C) Western blot analysis showed that the protein levels of Aβ oligomer were markedly reduced in the Trien-treated mice brain compared with controls. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (D) Results of ELISA Aβ 1–40 and Aβ 1–42 assays showed that Trien treatment led to a decrease in Aβ production. The level of Aβ was standardized to cortex tissue protein and expressed as Aβ ng/mg of tissue protein. All values are mean±SEM (n=6). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus the control group, #p<0.05 versus Trien 60 mg/kg treatment group (one-way ANOVA post hoc Fisher's PLSD).

Next, the protein expression of Aβ oligomer in APP/PS1 mice was evaluated with immunoblot. Aβ expression was significantly reduced in the 3-month Trien treatment condition [F(2,15)=16.08; p<0.01; Fig. 3C]. Moreover, the level of Aβ oligomer was reduced to 75.36%±11.06% of control (60 mg/kg, p<0.01) and 59.77%±11.46% of control (180 mg/kg, p<0.01).

Levels of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 were analyzed by sandwich ELISA. Trien treatment significantly reduced the levels of soluble Aβ1–40 [F(2,15)=6.53; p<0.01] and insoluble Aβ1–40 [F(2,15)=14.66; p<0.01] in APP/PS1 mice. Soluble Aβ1–40 levels in brain were reduced to 81.80%±8.25% of control (60 mg/kg, 59.58±6.01 ng/mg protein vs. 72.83±8.08 ng/mg protein; p<0.01) and 80.64%±11.56% of control (180 mg/kg, 58.74±8.42 ng/mg protein vs. 72.83±8.08 ng/mg protein; p<0.01) (Fig. 3D). Insoluble Aβ1–40 levels were reduced to 85.97%±9.48% of control (60 mg/kg, 5349.38±589.81 ng/mg protein vs. 6222.49±568.68 ng/mg protein; p<0.05) and 72.85%±7.28% of control (180 mg/kg, 4533.29±453.01 ng/mg protein vs. 6222.49±568.68 ng/mg protein; p<0.01). In addition, Trien administration significantly altered soluble Aβ1–42 [F(2,15)=15.58; p<0.01] and insoluble Aβ1–42 [F(2,15)=14.37; p<0.01] levels. Trien treatment decreased soluble Aβ1–42 levels to 82.29%±9.12% of control (60 mg/kg, 147.61±16.37 ng/mg protein vs. 179.38±6.75 ng/mg protein; p<0.01) and 74.87%±9.76% of control (180 mg/kg, 134.29±17.50 ng/mg protein vs. 179.38±6.75 ng/mg protein; p<0.01). For the 60 mg/kg and 180 mg/kg Trien treatment conditions, Trien treatment reduced insoluble levels of Aβ1–42 to 77.88%±4.12% of control (60 mg/kg, 9811.56±519.46 ng/mg protein vs. 12599.01±1864.61 ng/mg protein; p<0.01) and 67.80%±10.18% of control (180 mg/kg, 8542.59±1283.06 ng/mg protein vs. 12599.01±1864.61 ng/mg protein; p<0.01).

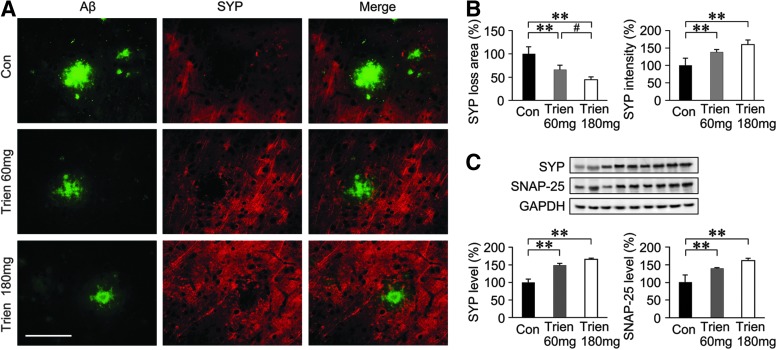

We then assessed the effects of Trien on synapse alterations. As shown in Figure 4, there was a significant effect of Aβ plaques on the decrease of synapse density in the APP/PS1 mouse brain. Whereas, under Trien treatment, the area of synaptophysin (SYP) loss was reduced to 66.23%±9.15% (60 mg/kg, p<0.01) and 44.12%±6.25% (180 mg/kg, p<0.01) of control, and the intensity of SYP was increased to 138.69%±7.27% (60 mg/kg, p<0.01) and 159.83%±13.16% (180 mg/kg, p<0.01) of control (Fig. 4A, B). In addition, western blot analysis of the samples using the anti-SYP and anti-synaptosomal-associated protein 25-kDa (SNAP-25) antibodies also confirmed these findings (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Trien treatment prevents synapse loss in the APP/PS1 mouse brain. (A) Brain sections of APP/PS1 mice were respectively labeled with anti-Aβ and anti-synaptophysin (SYP) antibodies to detect Aβ plaques and synapses. Negative stains of SYP revealed the synaptic disruption. Scale bar=50 μm. (B) Quantification showed the area of SYP loss and the intensity of SYP-positive regions. (C) Western blot showed that the protein expression levels of SYP and synaptosomal-associated protein 25-kDa (SNAP-25) were significantly reduced in the trientine-treated APP/PS1 mouse brain. All values are mean±SEM (n=6); **p<0.01 versus the control group (one-way ANOVA post hoc Fisher's PLSD).

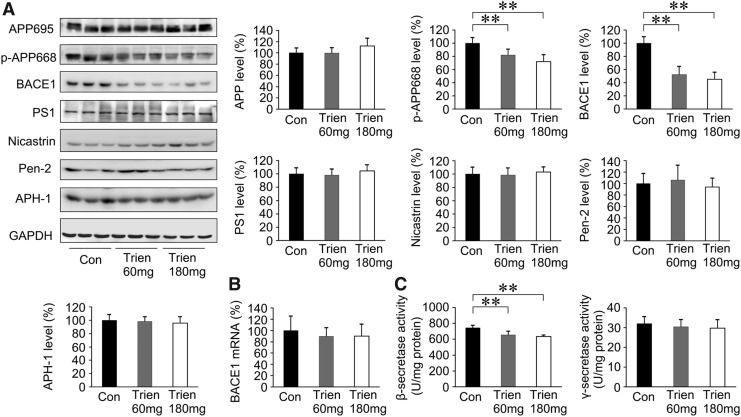

BACE1 is downregulated in Trien-treated APP/PS1 mouse brain

To determine whether the reduction of Aβ generation and aggregation in APP/PS1 mouse brain in Trien-treated group was correlated with β-secretase and γ-secretase activities, we measured β-secretase and γ-secretase. As shown in Figure 5A, we assessed the protein expression of APP, p-APP668, BACE1, PS1, nicastrin, APH1α, and Pen2. Western blot analysis revealed that the level of p-APP668 [F(2,15)=14.33, p<0.01] and BACE1 [F(2,15)=44.08, p<0.01] was decreased with Trien treatment. The protein expression of p-APP668 was reduced to 82.14%±8.65% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 71.97%±10.36% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01). Protein levels of BACE1 were reduced to 52.51%±12.09% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 45.17%±10.71% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01). Whereas, the variances in the protein expression levels of APP [F(2,15)=2.73; p>0.05], PS1 [F(2,15)=0.77; p>0.05], nicastrin [F(2,15)=0.37; p>0.05], Pen2 [F(2,15)=0.17; p>0.05], and APH-1 [F(2,15)=0.38; p>0.05] among the groups were not statistically significant when compared with the vehicle control.

FIG. 5.

Effects of Trien on β-secretase and γ-secretase in the APP/PS1 mouse brain. (A) Western blot analysis showed the levels of APP695, p-APP668, β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), and γ-secretase. There was no significant alteration in the level of APP695. The levels of p-APP668 and BACE1, however, were significantly reduced in Trien-treated APP/PS1 mouse brain. Accordingly, the expressions of γ-secretase complex proteins, PS1, nicastrin, APH1α, and Pen2 were not statistically altered in the Trien-treated group compared with controls. (B) Real-time PCR analysis indicated that there was no difference in mRNA levels of BACE1 between the Trien administration group and the vehicle-treated control group. (C) β-secretase and γ-secretase activities measured by an enzymatic cleavage assays showed that Trien markedly reduced β-secretase activity compared with the controls, whereas the activity of γ-secretase was not affected. All values are mean±SEM (n=6). **p<0.01 versus the control group (one-way ANOVA post hoc Fisher's PLSD).

The mRNA level of BACE1 was analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and Trien treatment did not alter the level of BACE1 mRNA [F(2,15)=0.43; p>0.05; Fig. 5B]. Therefore, the downregulation of BACE1 in Trien-treated APP/PS1 mouse brain only occurred at the protein level.

Next, we assessed β- and γ-secretase activities by an enzymatic cleavage assay. As shown in Figure 5C, β-secretase activity in the Trien-treated group was significantly reduced to 87.90%±6.18% of control (60 mg/kg; 654.51±46.03 U/mg protein vs. 744.63±32.00 U/mg protein; p<0.01) and 85.12%±2.24% of control (180 mg/kg; 633.85±16.70 vs. 744.63±32.00 U/mg protein; p<0.01); [F(2,15)=18.26; p<0.01]. There was no statistically significant difference in γ-secretase activity among groups [F(2,15)=0.56; p>0.05].

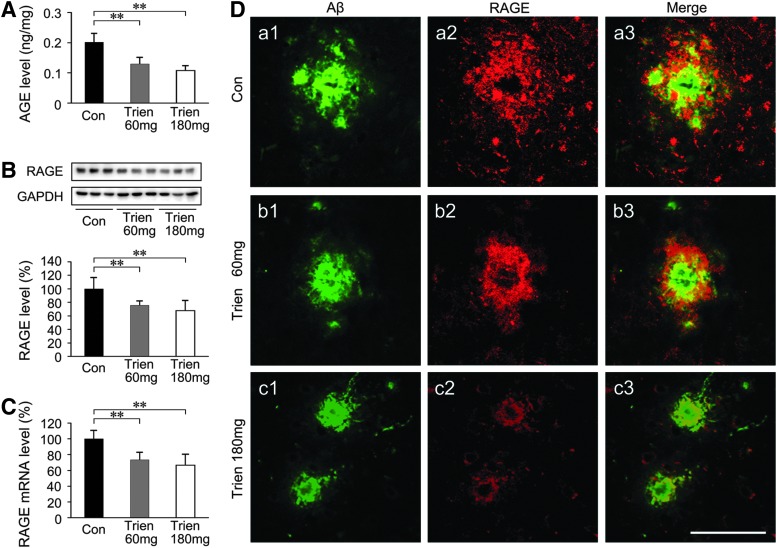

Trien treatment reduced AGE and downregulated RAGE in APP/PS1 Tg mouse brain

Both functional and pathologic research has shown that AGE/RAGE activation precedes the steep rise in cerebral Aβ and the formation of plaques (2). We assessed the effects of Trien on AGE and RAGE in APP/PS1 mouse brain. As shown in Figure 6A, sandwich ELISA analysis indicated that the level of AGE in Trien-treated mice was reduced to 64.02%±10.87% of control (60 mg/kg; 0.13±0.02 vs. 0.20±0.03 ng/mg tissue; p<0.01) and 53.68%±8.22% of control (180 mg/kg; 0.11±0.02 vs. 0.20±0.03 ng/mg tissue; p<0.01) [F(2,15)=27.32; p<0.01]. RAGE expression as detected by western blot and real-time PCR assays revealed that Trien treatment significantly downregulated RAGE not only at the protein level [F(2,15)=8.96; p<0.01; Fig. 6B] but also at the mRNA level [F(2,15)=14.06; p<0.01; Fig. 6C]. Using double immunofluorescence labeling of Aβ and RAGE in brain sections of APP/PS1 mice, we found that RAGE predominantly colocalized with the periphery of Aβ-positive plaques (Fig. 6D).

FIG. 6.

Assessment of Trien treatment on the effects of advanced glycation end product (AGE) and the receptor for AGEs (RAGE) in the APP/PS1 Tg mouse brain. (A) AGE contents were evaluated by sandwich ELISA. Quantization indicated that Trien treatment significantly reduced the AGE production in the APP/PS1 mice brain. The expression of RAGE was assessed by western blotting and real-time PCR. Western blot assays showed that the protein expression of RAGE was markedly reduced in the Trien-treated group (B), and similar results were seen with the mRNA expression (C). (D) Sections of APP/PS1 mouse brain were costained with anti-Aβ (a1, b1, c1) and anti-RAGE (a2, b2, c2) antibodies to label Aβ plaques and RAGE, respectively. Merged images from the double channels indicated that RAGE positive expression of immunofluorescence was predominantly observed and colocalized Aβ-positive plaques at the range of the Aβ plaques periphery in the cortex (a3, b3, c3). Scale bar=50 μm. All values are mean±SEM (n=6). **p<0.01 versus the control group (one-way ANOVA post hoc Fisher's PLSD).

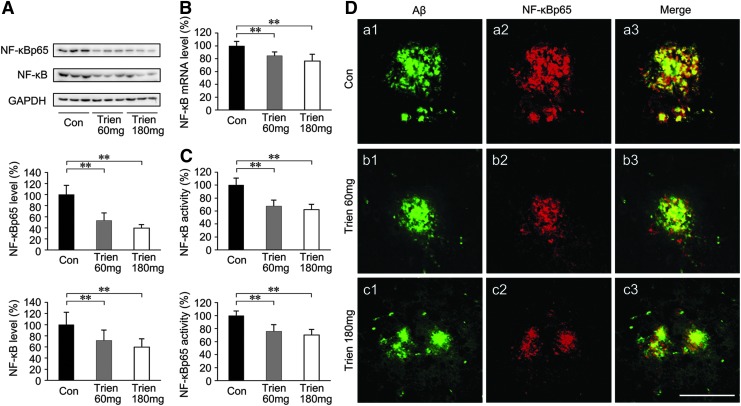

Trien treatment attenuated NF-κB activation in the APP/PS1 mouse brain

It has been reported that binding of RAGE to the ligands AGE and Aβ resulted in cellular oxidant stress (41, 78, 79) and subsequent activation of NF-κB (41, 79). To determine the effects of Trien on NF-κB, we measured the expression and activity of NF-κB in APP/PS1 mouse brain in both Trien- and vehicle-treated groups. The protein levels of total NF-κB [F(2,15)=7.23; p<0.01] and NF-κB p65 subunit [F(2,15)=35.99; p<0.01; Fig. 7A] in addition to NF-κB mRNA level [F(2,15)=13.88; p<0.01; Fig. 7B] were significantly reduced in the brain-derived nuclear extracts in the Trien treatment condition relative to controls. Trien treatment reduced the protein levels of total NF-κB to 71.56%±18.91% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01; Fig. 7A), and 59.59%±14.84% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01, Fig. 7A). The p65 subunit protein expression in Trien-treated group was reduced to 53.06%±13.63% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01; Fig. 7A), and 39.28%±6.43% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01; Fig. 7A). The mRNA levels of NF-κB were reduced to 84.62%±5.78% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01; Fig. 7B), and 76.19%±10.36% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01; Fig. 7B). Further, we assessed the activity of NF-κB in brain-derived nuclear extracts. As shown in Figure 7C, Trien treatment reduced the activity of total NF-κB to 75.73%±10.45% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 69.97%±8.72% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01) [F(2,15)=19.56; p<0.01], and the p65 subunit was reduced to 67.54%±9.03% of control (60 mg/kg; p<0.01) and 62.28%±7.96% of control (180 mg/kg; p<0.01) [F(2,15)=28.61; p<0.01]. Using double immunofluorescence labeling of Aβ and NF-κB, we found in 10-month-old APP/PS1 mouse brain that NF-κBp65 is localized to Aβ-positive plaques and closely adjacent neurons (Fig. 7D) but not astroglia (data not shown). In brain regions free of Aβ plaques, very few NF-κBp65 immunoreactive cells were present.

FIG. 7.

Effects on NF-κB in the APP/PS1 mouse brain under Trien treatment conditions. The expression and activity of NF-κB in the APP/PS1 mouse brain is shown for both Trien-treated groups and the vehicle-treated control group. (A) Western blot analysis showed that Trien administration significantly downregulated NF-κB. Protein levels of total NF-κB and NF-κBp65 subunit were markedly reduced in the brain-derived nuclear extracts from the Trien-treated APP/PS1 mice. (B) Real-time PCR assays indicated that the mRNA level of NF-κB in the brain-derived nuclear extracts of the Trien-treated group was significantly reduced. (C) Trien treatment induced an inhibition of nuclear activation of total NF-κB, and NF-κBp65, in brain-derived nuclear extracts of APP/PS1 mouse. (D) Double immunofluorescence labeling by anti-Aβ (a1, a2, a3) and anti-NF-κBp65 (b1, b2, b3) showed the colocalization of NF-κB immunoreactivity Aβ-positive plaques (c1, c2, c3). Scale bar=50 μm. All values are mean±SEM (n=6). **p<0.01 versus the control group (one-way ANOVA post hoc Fisher's PLSD).

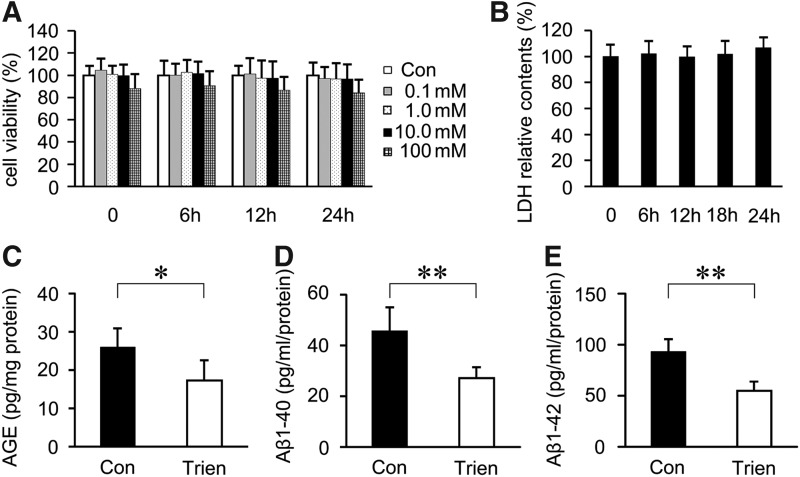

Trien treatment reduced AGE and Aβ generation in vitro

To examine the effect of Trien on AGE and Aβ generation, SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with APPsw. According to MTT and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) analysis, 10 mM Trien for 24 h was chosen for the treatment regimen for subsequent experiments in vitro (Fig. 8A, B). The results of sandwich ELISA assays indicated that Trien treatment reduced the contents of AGE to 66.57%±20.44% of control (17.26±5.30 pg/mg protein vs. 25.94±4.98 pg/mg protein; Student's t-test, p<0.05; Fig. 8C). Aβ 1–40 levels were reduced to 59.24%±9.74% of control (27.04±4.44 pg/ml protein vs. 45.64±9.35 pg/ml protein; Student's t-test, p<0.01; Fig. 8D) in the Trien-treated group, and the level of Aβ 1–42 was reduced to 58.73%±9.62% of control (54.95±9.01 pg/ml protein vs. 93.56±11.94 pg/ml protein; Student's t-test, p<0.01; Fig. 8D).

FIG. 8.

Trien administration reduced AGE and Aβ generation in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with human Swedish mutant APP (APPsw). MTT (A) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (B) assays showed that 0–10 mM Trien treatments had not observed significant toxic effects on SH-SY5Y cells transfected with APPsw. The contents of AGE and levels of Aβ analyzed by sandwich ELISA showed that the production of AGEs was significantly reduced under Trien treatment (C), and the generation of Aβ 1–40 and Aβ 1–42 in APPsw cells (D, E). All values are mean±SEM (n=3). *p<0.05, p**<0.01 versus the control group (one-way ANOVA and Student's t-test).

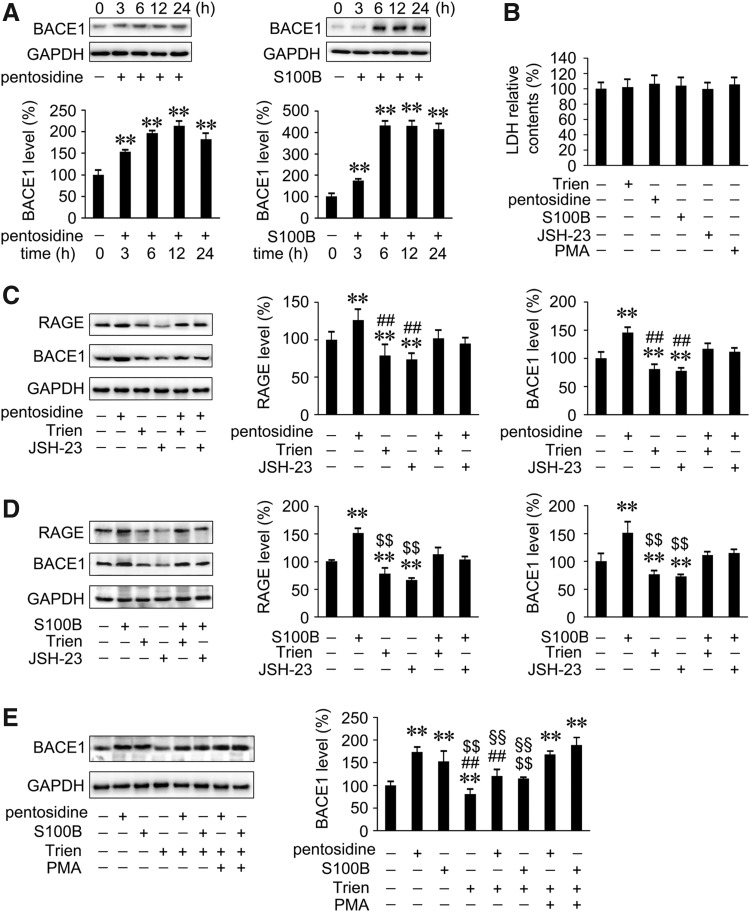

AGE/RAGE/NF-κB signaling is involved in Trien-mediated downregulation of BACE1

Previous studies have indicated that AGE/RAGE interactions were linked to early AD pathology (47, 64), and that RAGE activation potentiated Aβ-induced perturbation of neuronal function (2). A recent study suggested that activation of the AGEs/RAGE axis upregulated BACE1 via the NF-κB pathway (35). To further investigate the mechanism underlying Trien-mediated downregulation of BACE1 and mitigation of amyloidosis, we analyzed the effects of Trien on the AGE/RAGE/NF-κB signal in vitro. We examined the expression of BACE1 protein in APPsw cells with pentosidine, a biomarker for AGE, and the RAGE agonist S100B. Incubation time and doses of agonist or inhibitor were selected based on the western blot detection and LDH assays (Fig. 9A, B). Cells were pretreated for 6 h with 1 μM of pentosidine and 10 μg/ml of S100B prior to the addition of either Trien or inhibitor and activator. Pentosidine or S100B treatment induced significant increases in RAGE and BACE1 protein level in APPsw cells compared with controls (Fig. 9C, D). This effect was reversed by Trien treatment (Fig. 9C, D). The protein expression of RAGE and BACE1 was significantly increased to 126.07%±14.05% of control and 145.59%±8.71% of control, respectively, with pentosidine administration. These effects were reversed by either Trien or NF-κB activation inhibitor II, JSH-23 (20 μM). In APPsw cells preincubated with pentoside and then treated with Trien, the levels of RAGE and BACE1 were reduced to 80.65%±8.60% of pentosidine-treated alone [F(5,12)=8.26; p<0.01; Fig. 9C] and 79.93%±6.81% of pentosidine-treated alone [F(5,12)=26.26; p<0.01; Fig. 9C]. The S100B-induced increases of RAGE and BACE1 protein expression were 151.47%±8.87% of control and 151.21%±19.26% of control, respectively. In cells pretreated with S100B, Trien treatment decreased RAGE protein expression to 74.86%±12.47% of S100B treatment alone [F(5,12)=47.35; p<0.01; Fig. 9D] and decreased BACE protein level to 73.26%±3.71% of S100B treatment alone [F(5,12)=21.32; p<0.01; Fig. 9D]. To evaluate whether Trien-induced inhibition of pentosidine- or S100B-triggered BACE1 upregulation occurred via the suppression of NF-κB, we used the NF-κB activator PMA. Indeed, PMA partly attenuated Trien-mediated inhibition of pentosidine- or S100B-triggered BACE1 upregulation (p<0.01; Fig. 9E).

FIG. 9.

Trien-induced downregulation of BACE1 via the inhibition of AGE/RAGE/NF-kB pathway in APPsw cells. (A) Western blot assays indicted that the protein levels of BACE1 were induced after incubating with 1 μM pentosidine (a biomarker for AGE) or 10 μg/ml S100B (RAGE agonist) after 3 h and up to 24 h in APPsw cells. (B) LDH measurement showed that there were no significant alterations in cell viability in APPsw cells exposed to 1 μM pentosidine, 10 μg/ml S100B, 20 μM JSH-23 (NF-κB activation inhibitor), or 30 ng/ml PMA (NF-κB activator) for 6 h. The above interventions were used in the subsequent experiments in cultured cells. (C) Western blot analysis showed that Trien reversed the increase of pentosidine-triggered RAGE and BACE1 protein expression in APPsw cells, and the function of JSH-23. (D) S100B treatment induced increases in the levels of RAGE and BACE1 in APPsw cells. The effects were reversed by adding Trien to culture cells pretreated with S100B, similar to JSH-23. (E) The inhibitions caused by Trien on pentosidine- or S100B-induced BACE1 increase were partly blocked by NF-κB activator, PMA. All values are mean±SEM (n=3). **p<0.01 versus control group, ##p<0.01 vs. pentosidine-treatment group, $$p<0.01 versus S100B-treated group, §§p<0.01 versus PMA addition group (one-way ANOVA post hoc Fisher's PLSD).

Discussion

Trien is a potent and selective copper chelator that works to ameliorate the symptoms of Wilson's disease by facilitating the excretion of copper. Recent studies demonstrated that Trien may be a potential therapeutic option for several secondary complications of diabetes. Trien reversed LV damage in diabetic rats, ameliorated LV hypertrophy in humans with T2DM (23), decreased symptoms of cardiomyopathy in the Zucker T2DM rat (5), reduced the concentration of MDA in diabetic rats (55), and improved motor nerve conduction velocity in streptozotocin-induced diabetes rats (16). Shared characteristics of diabetes and AD, such as oxidative stress, vascular disease, and formation of localized protein aggregates, suggest there may be a common underlying pathogenic mechanism. Indeed, the Cu (I) chelator, D-penicillamine, has been shown to effectively resolubilize copper-Aβ1–42 aggregates (25). In addition, tetrathiomolybdate, a copper-binding agent, attenuated amyloid pathology in the Tg2576 Tg mouse (59), and Trien and a compound containing Trien were shown to solubilize Aβ from postmortem AD tissues and C100 AD model mice (19). However, there existed no detailed report of the therapeutic effects of Trien on AD in vivo and in vitro.

In the current study, the effects of Trien on several AD phenotypes in the APP/PS1 mouse brain were examined. Oral administration of Trien for 3 months did not affect body weight or alter the levels of Cu, Fe, and Zn in serum or brain, suggesting that the drug was well tolerated by the animals (24). Copper transporters in humans are complex molecular machines that regulate intracellular copper concentration, and they critically facilitate copper-dependent enzyme biosynthesis (48). We assayed the expression of various copper transport proteins, including CTR1, ATP7A, and ATP7B in the APP/PS1 mouse brain and found that Trien treatment did not alter their levels. On the other hand, we found that Trien treatment was neuroprotective in APP/PS1 mouse brain by increasing SOD1 activity, reducing AGE contents, reducing the oxidative stress product MDA, and attenuating amyloidosis. Trien significantly reduced the levels of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, significantly attenuated aggregation of Aβ oligomers, and it markedly reduced the formation of Aβ plaques in APP/PS1 mouse brain. Meanwhile, Trien treatment reduced copper and zinc accumulation in the plaques. In addition, the loss of synaptic markers correlates with the disease progression and cognitive decline in AD (67). In the present study, Trien administration reduced the loss of SYP and SNAP-25 signals, which further revealed its therapeutic potentials on mitigating AD-like pathologies.

Aβ is derived from sequential cleavage of APP by the amyloidogenic β-secretases and γ-secretases. The abnormal aggregation of Aβ is intimately linked to the pathogenesis of AD (36, 37, 71). Therefore, we then examined the effects of Trien on the β-secretase BACE1, and the γ-secretase complex, PS1, Nicastrin, APH1α, and Pen2. In this study, Trien treatment did not significantly affect γ-secretase activity or protein expression. However, Trien treatment did reduce the activity and protein expression of BACE1. Quantitative real-time PCR assays showed that Trien administration did not alter BACE1 mRNA levels, which indicated that Trien-mediated downregulation of BACE1 expression occurred at the level of protein expression only.

Several lines of study have observed that AGE-mediated pathology is via reactive oxygen species (17, 58). Increased levels of extracellular AGEs have been found in Aβ plaques (62). RAGE is a multiligand transmembrane receptor that can bind AGE, Aβ, amphoterin, S100B, and other ligands (7, 27, 63). Tg mice that express mutant human APP and RAGE in neurons display functional and pathologic neuronal perturbations that precede Aβ and plaque formation in cerebrum (2). RAGE functions as a transporter of Aβ, and RAGE association with Aβ results in increased Aβ influx into the brain across the blood–brain barrier (27, 28). Increased RAGE levels may coincide with the onset of AD (52). Most importantly, activation of RAGE stimulates functional BACE1 expression and potentiates Aβ production and deposition (21), whereas, blockade of RAGE suppresses Aβ aggregation (27). In the present study, we observed that AGE and RAGE levels are markedly reduced in Trien-treated APP/PS1 mouse brain. Immunofluorescent double labeling revealed the colocalization of RAGE and Aβ in the APP/PS1 mouse brain. This supports the model of RAGE-mediated transport of Aβ.

Further, we elucidated the mechanism underlying Trien-induced inhibition of RAGE and downregulation of BACE1. The elevation of RAGE, the oxidative stress marker, could activate cell signaling pathways such as NF-κB and Nrf2 in AD (13). NF-κB pathway is a representative transcription factor activated by RAGE–ligand interactions (34, 41), and BACE1 promoter activity was regulated by NF-κB (6). Recently, Guglielmotto and colleagues observed that AGEs/RAGE complex upregulated BACE1 through NF-κB activation (35). To determine whether downregulation of BACE1 protein by Trien in APP/PS1 mice was via the same pathway, we analyzed NF-κB in the nuclear extract of brain tissue. The results showed that Trien treatment in the mice reduced total NF-κB and NF-κBp65 levels, and reduced NF-κBp65 immunoreactivity in Aβ plaques. Further, we observed in vitro that pentosidine (a biomarker for AGE) and S100B (a RAGE agonist) induced the activation of BACE1 in APPsw cells, and that JSH-23 (NF-κB activation inhibitor II) blocked this effect. Our data are in strong agreement with a previous study that described RAGE-mediated activation of BACE1 through the NF-κB pathway (35). Most interestingly, Trien treatment suppressed pentosidine- or S100B- triggered upregulation of BACE1, and this effect was partly attenuated by the NF-κB activator PMA, suggesting that a component of Trien downregulation of BACE is through inhibition of NF-κB.

Our findings add to a growing consensus that dysregulation of copper plays an important role in the progression of AD. The copper chelator Trien alleviates several cellular abnormalities in AD mouse model animals including decreased SOD1, elevated MDA and AGEs, and amyloidosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatment

APP/PS1 (APPswe/PSEN1dE9) double-Tg mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (West Grove, PA). Mice were maintained in a controlled environment (22°C–25°C, 40%–60% relative humidity, and 12 h light/dark cycle) with a standard diet and distilled water available ad libitum. All experimental procedures using animals were designed to minimize suffering and the number of subjects used. These studies were carried out in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of medical animals established by the Ministry of Health, Peoples Republic of China (1998) and the ethical standards for laboratory animals of China Medical University.

Seven-month-old, female APP/PS1 double Tg mice were randomly divided into three treatment groups (n=6 in each group): vehicle control, 60 mg/kg Trien (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 180 mg/kg Trien. Trien was administered by oral gavage once a day for 3 months, and vehicle control mice were given physiological saline (100 μl). Body weight and general health of the mice were monitored daily.

Tissue preparation

Twenty-four hours after the last oral gavage treatment of either Trien or vehicle, mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally), and venous blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus. Animals were then transcardially perfused with saline and sacrificed by decapitation. The brains were immediately removed and dissected in half on an ice-cold board. One was prepared for morphological assessment. The other half was frozen at −80°C for biochemical analyses.

Atomic absorption spectrum

Copper levels in the temporal lobe, parietal lobe, frontal lobe of cortex and hippocampus of 7-month-old APP/PS1 mice and age-matched C57BL/6 mice were measured as previously described with minor modifications using a polarized Zeeman atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Model 180-80; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) (59). After 3 months Trien treatment, the levels of copper, iron, and zinc in the serum and cortex of APP/PS1 mice were also determined. Briefly, samples were weighed and digested in 0.5–2 ml of concentrated nitric acid (∼69.5%) overnight and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min. The supernatants were sequentially diluted to yield a final nitric acid concentration of 35%. Samples were diluted further with 2% nitric acid so that they were in the linear absorption range of the calibration curve (1–10 ppb [ng/L]). Twenty microliters of each sample was injected, and the injection time depended on the standard deviation of the measurement. Metal ion concentration of the sample was extrapolated from a calibration curve.

Autometallography

Autometallography was performed according to previously reported procedure with minor modifications (26). Briefly, fresh brain slices (2 mm) were cut with a vibratome and immersed in a mixture of 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.15 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 24 h. The brain slices were placed in 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C. Ten micrometer coronal cryostat sections were prepared. Brain sections were incubated in the autometallography developer at room temperature for 1 h. After a 1-min wash in running water, the sections were fixed in 10% sodium thiosulfate for 10 min to yield silver grains at the sites of Cu deposition. After several washes with distilled water, the sections were then dehydrated, covered, and examined with a microscope equipped with a digital camera (Model DP71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

TSQ staining

TSQ fluorescence staining was performed as previously described (32, 42). Briefly, without fixation, cryostat brain sections (20 μm) were prepared and immersed in a TSQ solution buffer (pH 10.5) containing 4.5 μM TSQ (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), 140 mM sodium barbital, and 140 mM sodium acetate for 1 min. TSQ binding was imaged with a fluorescence microscope (Model DP71; Olympus).

Immunofluorescence and confocal laser scanning microscopy

Coronal paraffin sections (6 μm) were dewaxed, rehydrated, and then treated in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. After three washes with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), sections were boiled in Tris, EDTA, and glycine buffer (TEG, pH 8) for 5 min in a microwave oven. After washing, the sections were blocked with 3% normal bovine serum albumin for 30 min. The slides were incubated with mouse anti-Aβ (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature overnight. Negative control sections were identically treated except for the exclusion of the primary antibodies. Following washes, sections were incubated with DyLight 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were mounted with an antifade mounting medium and examined using a microscope (Model DP71; Olympus). Analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

For immunofluorescent double staining, sections or cell cultures were blocked with normal donkey serum (1:20; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and incubated overnight with either mouse anti-Aβ (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich) and rabbit anti-SYP (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), mouse anti-Aβ and rabbit anti-RAGE (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or mouse anti-Aβ and rabbit anti-NF-κB p65 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Subsequently, samples were incubated in DyLight 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, Texas Red-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at room temperature for 2 h. The sections and cultured cells were mounted and examined using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Model SP2; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were collected and analyzed using Nikon EclipseNet and Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Western blotting

Homogenates of APP/PS1 mouse brain and treated cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and total protein levels were measured using a UV 1700 PharmaSpec ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). Thirty micrograms of protein was loaded onto 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h, transferred PVDF membranes were probed overnight with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-amyloid oligomer (1:500; Millipore), rabbit anti-SYP (1:2000; Abcam), rabbit anti-SNAP-25 (1:1000; Abcam), rabbit anti-BACE1 (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-PS1 (1:1000; Abcam), rabbit anti-APH1α (1:500; Abcam), rabbit anti-nicastrin (1:1000; Abcam), rabbit anti-Pen2 (1:200; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), rabbit anti-APP (1:4000; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), rabbit anti-p-APP668 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-RAGE (1:200; H-300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-NF-κB p65 (1:1000, C-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-CTR1 (1:500; Abcam), rabbit anti-ATP7A (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-ATP7B (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse anti-GAPDH (1:10,000; Kangchen Biotech, Shanghai, China). Immunoblots were washed and treated with the appropriate species horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and immunological complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using the ChemiDoc XRS system and the accompanying Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The immunoreactive bands were quantified using Image-pro Plus 6.0 analysis software.

Cell culture and drug treatments

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with Swedish mutant APP (APPsw) were grown as previously described (77). The cells at ≈80% confluence were treated with a biomarker for AGEs, pentosidine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), RAGE agonist S100B (Millipore), NF-κB activation inhibitor II (Millipore), Trien, NF-κB activator, or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich) as indicated. Untreated culture cells were used as the vehicle control.

Measurement of Cp, SOD1, β-secretase and γ-secretase activities, and MDA contents

Plasma Cp activity was measured using the oxidase method (66). Briefly, 7.5 μl of plasma was treated with 75 μl of 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 6.0) at 37°C for 5 min. Thirty microliters of prewarmed aqueous o-dianisidine dihydrochloride solution (2.5 mg/ml) was added to each sample and incubated another 5 min at 37°C. For the first time point, half of the sample was quenched with 150 μl of 9 M sulfuric acid (t1). The remainder of the solution was incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and quenched as described above (t2). Absorbance (Abs) of each sample was read at 540 nm. The enzymatic activity of Cp was calculated from the following equation: Activity (U/ml)=416×(Abs t2−Abs t1) (59).

SOD1 activity in the frontal cortex or cell lysates was detected using a Superoxide Dismutase Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit (Abcam). Brain tissue or cells were lysed in ice-cold buffer containing 0.1M Tris/HCl, pH 7.4 with 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mg/ml PMSF. Samples were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 5 min. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the supernatant was diluted by 1:19 with the assay buffer solution, and the absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan Group, Maennedorf, Switzerland).

MDA levels in the frontal cortex homogenates were analyzed using a Malondialdehyde Colorimetric Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Jiancheng Biology, Nanjing, China). The absorbance was read at 532 nm using a microplate reader.

γ-secretase and β-secretase activities in frontal cortex or cell lysates were detected by using specific peptides conjugated to the reporter molecules EDANS and DABCYL (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Briefly, brain tissues or treated cells were incubated in extraction buffer for 1 h on ice, homogenized, and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 2 min. The supernatant was mixed with 2×reaction buffer and 5 μl of substrate. The samples were incubated at 37°C away from light for 2 h and read on a fluorescent microplate reader.

NF-κB activity was measured according to the protocol described previously (35). Briefly, nuclear extract was isolated from brain tissue homogenates using the Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif, Rixensart, Belgium). Samples were added onto a 96-well plate immobilized with an oligonucleotide containing an NF-κB consensus binding site (5′-GGGACTTTCC-3′) specific for the active form of NF-κB. Next, the primary antibody against the active form of NF-κB total and p65 subunits was added to the wells, and after thoroughly rinsing, the secondary HRP-conjugated antibody was added. The absorbance was measured by spectrophotometry at 450 nm.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cerebral cortex tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two micrograms of total RNA from each tissue sample was reverse transcribed using the Prime Script™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan) and the following reverse transcription program: 37°C for 15 min, 85°C for 5 s. Quantitative PCR was performed with the SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems, Inc. [ABI], Foster City, CA) using an ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System. Fifty nanograms samples of cDNA were added to the reaction mixtures. Cycling conditions included preincubation at 50°C for 2 min, DNA polymerase activation at 95°C for 5 min, and 40 cycles of denaturing at 95°C for 30 s and annealing and extension at 58°C for 30 s. Each cDNA sample was tested in triplicate. The following PCR primers were used for quantification: BACE1: forward, GGC AGT CTC TGG TAC ACA CC and reverse, ACT CCT TGC AGT CCA TCT TG; RAGE: forward, CCC TGA GAC GGG ACT CTT TA and reverse, GTT GGA TAG GGG CTG TGT TC; NF-κB p65: forward, GGC GGC ACG TTT TAC TCT TT and reverse, CCG TCT CCA GGA GGT TAA TGC; β-actin: forward, GTA TGA CTC CAC TCA CGG CAA A and reverse, GGT CTC GCT CCT GGA AGA TG. Expression was calculated using cycle time (Ct) values normalized to β-actin, and relative differences between control and treatment groups were expressed as a percentage relative to control.

Sandwich ELISA

For Aβ detection, the cortex of mice was placed in either ice-cold 20 mM Tris, pH 8.5 (soluble) or 5 M guanidine HCl/50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (insoluble), and thoroughly ground with a hand-held motor. The homogenate was diluted with dilution buffer plus protease inhibitor cocktail centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min at 4°C, and the resultant supernatant was collected. For determination of Aβ secretion in vitro, culture medium of treated cells was collected. The levels of Aβ 1–40 and Aβ 1–42 were measured using human Aβ1–40 ELISA kits (Invitrogen) and Aβ1–42 ELISA kits (Invitrogen), respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For quantification of AGE levels, mouse brain homogenates were centrifuged for 30 min at 1000 g. For the measurement of AGE in vitro, treated cells were collected and lysed. The levels of AGE were detected using an AGE ELISA kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA) per the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were read at 450 nm.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean±SEM. Statistical significance between vehicle and Trien treatment was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Bonferroni or Tamhane's T2 test when appropriate. All other comparisons were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Fisher's PLSD. Results were reported to be highly statistically significant if p<0.01 and statistically significant if p<0.05.

Abbreviations Used

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AGE

advanced glycation end products

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- APPsw

human APP Swedish mutation

- BACE1

β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1

- Cp

ceruloplasmin

- CTR1

copper transporter 1

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LV

left ventricular

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- PLSD

protected least significant difference

- PS1

presenilin-1

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end products

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SNAP-25

synaptosomal-associated protein 25-kDa

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase 1

- SYP

synaptophysin

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- Tg

transgenic

- TSQ

N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluenesulfonamide

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81100808, 81071004, 81100810, and 81200972), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 20100471481 and 2012M510849), and the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (No. 20112104120010).

Author Disclosure Statement

There are no potential conflicts of interest, including any financial, personal, or other relationships with people or organizations that could inappropriately influence the current study.

References

- 1.Angeletti B, Waldron KJ, Freeman KB, Bawagan H, Hussain I, Miller CC, Lau KF, Tennant ME, Dennison C, Robinson NJ, and Dingwall C. BACE1 cytoplasmic domain interacts with the copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase-1 and binds copper. J Biol Chem 280: 17930–17937, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arancio O, Zhang HP, Chen X, Lin C, Trinchese F, Puzzo D, Liu S, Hegde A, Yan SF, Stern A, Luddy JS, Lue LF, Walker DG, Roher A, Buttini M, Mucke L, Li W, Schmidt AM, Kindy M, Hyslop PA, Stern DM, and Du Yan SS. RAGE potentiates Abeta-induced perturbation of neuronal function in transgenic mice. EMBO J 23: 4096–4105, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ascolani A, Balestrieri E, Minutolo A, Mosti S, Spalletta G, Bramanti P, Mastino A, Caltagirone C, and Macchi B. Dysregulated NF-kappaB pathway in peripheral mononuclear cells of Alzheimer's disease patients. Curr Alzheimer Res 9: 128–137, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atwood CS, Perry G, Zeng H, Kato Y, Jones WD, Ling KQ, Huang X, Moir RD, Wang D, Sayre LM, Smith MA, Chen SG, and Bush AI. Copper mediates dityrosine cross-linking of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta. Biochemistry 43: 560–568, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baynes JW. and Murray DB. The metal chelators, trientine and citrate, inhibit the development of cardiac pathology in the Zucker diabetic rat. Exp Diabetes Res 2009: 696378, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourne KZ, Ferrari DC, Lange-Dohna C, Rossner S, Wood TG, and Perez-Polo JR. Differential regulation of BACE1 promoter activity by nuclear factor-kappaB in neurons and glia upon exposure to beta-amyloid peptides. J Neurosci Res 85: 1194–1204, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bucciarelli LG, Wendt T, Rong L, Lalla E, Hofmann MA, Goova MT, Taguchi A, Yan SF, Yan SD, Stern DM, and Schmidt AM. RAGE is a multiligand receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily: implications for homeostasis and chronic disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 59: 1117–1128, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buggia-Prevot V, Sevalle J, Rossner S, and Checler F. NFkappaB-dependent control of BACE1 promoter transactivation by Abeta42. J Biol Chem 283: 10037–10047, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush AI. Copper, zinc, and the metallobiology of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 17: 147–150, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bush AI, Pettingell WH, Jr., Paradis MD, and Tanzi RE. Modulation of A beta adhesiveness and secretase site cleavage by zinc. J Biol Chem 269: 12152–12158, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterfield DA. and Lauderback CM. Lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation in Alzheimer's disease brain: potential causes and consequences involving amyloid beta-peptide-associated free radical oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 32: 1050–1060, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Cuzzocrea S, Iavicoli I, Rizzarelli E, and Calabrese EJ. Hormesis, cellular stress response and vitagenes as critical determinants in aging and longevity. Mol Aspects Med 32: 279–304, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Calabrese EJ, and Mattson MP. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal 13: 1763–1811, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Iavicoli I, Di Paola R, Koverech A, Cuzzocrea S, Rizzarelli E, and Calabrese EJ. Cellular stress responses, hormetic phytochemicals and vitagenes in aging and longevity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822: 753–783, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calabrese V, Mancuso C, Calvani M, Rizzarelli E, Butterfield DA, and Stella AM. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 766–775, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron NE. and Cotter MA. Neurovascular dysfunction in diabetic rats. Potential contribution of autoxidation and free radicals examined using transition metal chelating agents. J Clin Invest 96: 1159–1163, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carubelli R, Schneider JE, Jr., Pye QN, and Floyd RA. Cytotoxic effects of autoxidative glycation. Free Radic Biol Med 18: 265–269, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherny RA, Atwood CS, Xilinas ME, Gray DN, Jones WD, McLean CA, Barnham KJ, Volitakis I, Fraser FW, Kim Y, Huang X, Goldstein LE, Moir RD, Lim JT, Beyreuther K, Zheng H, Tanzi RE, Masters CL, and Bush AI. Treatment with a copper-zinc chelator markedly and rapidly inhibits beta-amyloid accumulation in Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice. Neuron 30: 665–676, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherny RA, Barnham KJ, Lynch T, Volitakis I, Li QX, McLean CA, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Tanzi RE, Masters CL, and Bush AI. Chelation and intercalation: complementary properties in a compound for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Struct Biol 130: 209–216, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiurchiu V. and Maccarrone M. Chronic inflammatory disorders and their redox control: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 2605–2641, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho HJ, Son SM, Jin SM, Hong HS, Shin DH, Kim SJ, Huh K, and Mook-Jung I. RAGE regulates BACE1 and Abeta generation via NFAT1 activation in Alzheimer's disease animal model. FASEB J 23: 2639–2649, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper GJ. Therapeutic potential of copper chelation with triethylenetetramine in managing diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer's disease. Drugs 71: 1281–1320, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper GJ, Phillips AR, Choong SY, Leonard BL, Crossman DJ, Brunton DH, Saafi L, Dissanayake AM, Cowan BR, Young AA, Occleshaw CJ, Chan YK, Leahy FE, Keogh GF, Gamble GD, Allen GR, Pope AJ, Boyd PD, Poppitt SD, Borg TK, Doughty RN, and Baker JR. Regeneration of the heart in diabetes by selective copper chelation. Diabetes 53: 2501–2508, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper GJ, Young AA, Gamble GD, Occleshaw CJ, Dissanayake AM, Cowan BR, Brunton DH, Baker JR, Phillips AR, Frampton CM, Poppitt SD, and Doughty RN. A copper(II)-selective chelator ameliorates left-ventricular hypertrophy in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia 52: 715–722, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui Z, Lockman PR, Atwood CS, Hsu CH, Gupte A, Allen DD, and Mumper RJ. Novel D-penicillamine carrying nanoparticles for metal chelation therapy in Alzheimer's and other CNS diseases. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 59: 263–272, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danscher G. Autometallography. A new technique for light and electron microscopic visualization of metals in biological tissues (gold, silver, metal sulphides and metal selenides). Histochemistry 81: 331–335, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, Welch D, Manness L, Lin C, Yu J, Zhu H, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Stern A, Schmidt AM, Armstrong DL, Arnold B, Liliensiek B, Nawroth P, Hofman F, Kindy M, Stern D, and Zlokovic B. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med 9: 907–913, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deane R, Wu Z, and Zlokovic BV. RAGE (yin) versus LRP (yang) balance regulates alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide clearance through transport across the blood-brain barrier. Stroke 35: 2628–2631, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong J, Atwood CS, Anderson VE, Siedlak SL, Smith MA, Perry G, and Carey PR. Metal binding and oxidation of amyloid-beta within isolated senile plaque cores: Raman microscopic evidence. Biochemistry 42: 2768–2773, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong J, Canfield JM, Mehta AK, Shokes JE, Tian B, Childers WS, Simmons JA, Mao Z, Scott RA, Warncke K, and Lynn DG. Engineering metal ion coordination to regulate amyloid fibril assembly and toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 13313–13318, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eskici G. and Axelsen PH. Copper and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry 51: 6289–6311, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frederickson CJ, Kasarskis EJ, Ringo D, and Frederickson RE. A quinoline fluorescence method for visualizing and assaying the histochemically reactive zinc (bouton zinc) in the brain. J Neurosci Methods 20: 91–103, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frommer DJ. Defective biliary excretion of copper in Wilson's disease. Gut 15: 125–129, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granic I, Dolga AM, Nijholt IM, van Dijk G, and Eisel UL. Inflammation and NF-kappaB in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes. J Alzheimers Dis 16: 809–821, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guglielmotto M, Aragno M, Tamagno E, Vercellinatto I, Visentin S, Medana C, Catalano MG, Smith MA, Perry G, Danni O, Boccuzzi G, and Tabaton M. AGEs/RAGE complex upregulates BACE1 via NF-kappaB pathway activation. Neurobiol Aging 33: 196 e13–196 e 27, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hardy J. and Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297: 353–356, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy JA. and Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256: 184–185, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayden MS. and Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev 18: 2195–2224, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O'Brien P, Petersen RC, and Butler PC. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 53: 474–481, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaltschmidt B, Uherek M, Volk B, Baeuerle PA, and Kaltschmidt C. Transcription factor NF-kappaB is activated in primary neurons by amyloid beta peptides and in neurons surrounding early plaques from patients with Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 2642–2647, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lander HM, Tauras JM, Ogiste JS, Hori O, Moss RA, and Schmidt AM. Activation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products triggers a p21(ras)-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway regulated by oxidant stress. J Biol Chem 272: 17810–17814, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JY, Mook-Jung I, and Koh JY. Histochemically reactive zinc in plaques of the Swedish mutant beta-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci 19: RC10, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J, Guo L, Yin F, Zheng X, Chen G, and Wang Y. Characterization and antitumor activity of triethylene tetramine, a novel telomerase inhibitor. Biomed Pharmacother 62: 480–485, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loske C, Gerdemann A, Schepl W, Wycislo M, Schinzel R, Palm D, Riederer P, and Munch G. Transition metal-mediated glycoxidation accelerates cross-linking of beta-amyloid peptide. Eur J Biochem 267: 4171–4178, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, and Markesbery WR. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer's disease senile plaques. J Neurol Sci 158: 47–52, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Stern Y, Shea S, and Mayeux R. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer's disease and dementia with stroke in a multiethnic cohort. Am J Epidemiol 154: 635–641, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lue LF, Walker DG, Brachova L, Beach TG, Rogers J, Schmidt AM, Stern DM, and Yan SD. Involvement of microglial receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) in Alzheimer's disease: identification of a cellular activation mechanism. Exp Neurol 171: 29–45, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lutsenko S, LeShane ES, and Shinde U. Biochemical basis of regulation of human copper-transporting ATPases. Arch Biochem Biophys 463: 134–148, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Markesbery WR. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer's disease. Free Radic Biol Med 23: 134–147, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maynard CJ, Bush AI, Masters CL, Cappai R, and Li QX. Metals and amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Exp Pathol 86: 147–159, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maynard CJ, Cappai R, Volitakis I, Cherny RA, Masters CL, Li QX, and Bush AI. Gender and genetic background effects on brain metal levels in APP transgenic and normal mice: implications for Alzheimer beta-amyloid pathology. J Inorg Biochem 100: 952–962, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller MC, Tavares R, Johanson CE, Hovanesian V, Donahue JE, Gonzalez L, Silverberg GD, and Stopa EG. Hippocampal RAGE immunoreactivity in early and advanced Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 1230: 273–280, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moriguchi M, Nakajima T, Kimura H, Watanabe T, Takashima H, Mitsumoto Y, Katagishi T, Okanoue T, and Kagawa K. The copper chelator trientine has an antiangiogenic effect against hepatocellular carcinoma, possibly through inhibition of interleukin-8 production. Int J Cancer 102: 445–452, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Munch G, Mayer S, Michaelis J, Hipkiss AR, Riederer P, Muller R, Neumann A, Schinzel R, and Cunningham AM. Influence of advanced glycation end-products and AGE-inhibitors on nucleation-dependent polymerization of beta-amyloid peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1360: 17–29, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakamura J, Hamada Y, Chaya S, Nakashima E, Naruse K, Kato K, Yasuda Y, Kamiya H, Sakakibara F, Koh N, and Hotta N. Transition metals and polyol pathway in the development of diabetic neuropathy in rats. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 18: 395–402, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Reilly S, Weber PM, Oswald M, and Shipley L. Abnormalities of the physiology of copper in Wilson's disease. 3. The excretion of copper. Arch Neurol 25: 28–32, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Opazo C, Huang X, Cherny RA, Moir RD, Roher AE, White AR, Cappai R, Masters CL, Tanzi RE, Inestrosa NC, and Bush AI. Metalloenzyme-like activity of Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid. Cu-dependent catalytic conversion of dopamine, cholesterol, and biological reducing agents to neurotoxic H(2)O(2). J Biol Chem 277: 40302–40308, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ortwerth BJ, James H, Simpson G, and Linetsky M. The generation of superoxide anions in glycation reactions with sugars, osones, and 3-deoxyosones. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 245: 161–165, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quinn JF, Harris CJ, Cobb KE, Domes C, Ralle M, Brewer G, and Wadsworth TL. A copper-lowering strategy attenuates amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 21: 903–914, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reddy PH. Amyloid precursor protein-mediated free radicals and oxidative damage: implications for the development and progression of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 96: 1–13, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Religa D, Strozyk D, Cherny RA, Volitakis I, Haroutunian V, Winblad B, Naslund J, and Bush AI. Elevated cortical zinc in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67: 69–75, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salkovic-Petrisic M. and Hoyer S. Central insulin resistance as a trigger for sporadic Alzheimer-like pathology: an experimental approach. J Neural Transm Suppl 72: 217–233, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, and Stern DM. The biology of the receptor for advanced glycation end products and its ligands. Biochim Biophys Acta 1498: 99–111, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, and Stern DM. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest 108: 949–955, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schonberger SJ, Edgar PF, Kydd R, Faull RL, and Cooper GJ. Proteomic analysis of the brain in Alzheimer's disease: molecular phenotype of a complex disease process. Proteomics 1: 1519–1528, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schosinsky KH, Lehmann HP, and Beeler MF. Measurement of ceruloplasmin from its oxidase activity in serum by use of o-dianisidine dihydrochloride. Clin Chem 20: 1556–1563, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science 298: 789–791, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev 81: 741–766, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Selkoe DJ. Amyloid beta protein precursor and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Cell 58: 611–612, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, and Selkoe DJ. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 14: 837–842, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shoji M, Golde TE, Ghiso J, Cheung TT, Estus S, Shaffer LM, Cai XD, McKay DM, Tintner R, Frangione B, et al. . Production of the Alzheimer amyloid beta protein by normal proteolytic processing. Science 258: 126–129, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Terai K, Matsuo A, and McGeer PL. Enhancement of immunoreactivity for NF-kappa B in the hippocampal formation and cerebral cortex of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 735: 159–168, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trojanowski JQ. and Lee VM. Phosphorylation of paired helical filament tau in Alzheimer's disease neurofibrillary lesions: focusing on phosphatases. FASEB J 9: 1570–1576, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vassar R, Kovacs DM, Yan R, and Wong PC. The beta-secretase enzyme BACE in health and Alzheimer's disease: regulation, cell biology, function, and therapeutic potential. J Neurosci 29: 12787–12794, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, and Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416: 535–539, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walshe JM. Treatment of Wilson's disease with trientine (triethylene tetramine) dihydrochloride. Lancet 1: 643–647, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang CY, Zheng W, Wang T, Xie JW, Wang SL, Zhao BL, Teng WP, and Wang ZY. Huperzine A activates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and enhances the nonamyloidogenic pathway in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse model. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 1073–1089, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, Roher A, Slattery T, Zhao L, Nagashima M, Morser J, Migheli A, Nawroth P, Stern D, and Schmidt AM. RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Nature 382: 685–691, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yan SD, Schmidt AM, Anderson GM, Zhang J, Brett J, Zou YS, Pinsky D, and Stern D. Enhanced cellular oxidant stress by the interaction of advanced glycation end products with their receptors/binding proteins. J Biol Chem 269: 9889–9897, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]