Abstract

Background

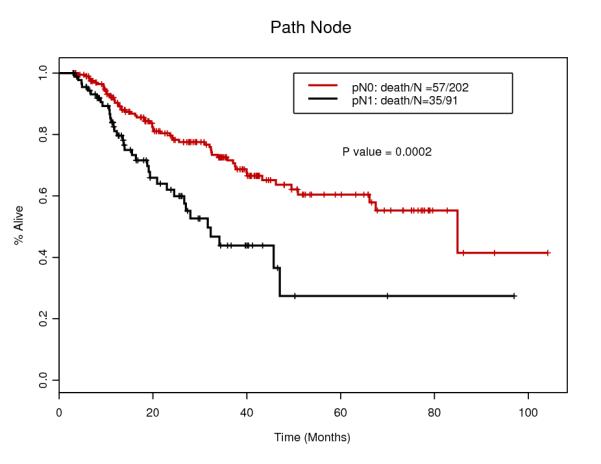

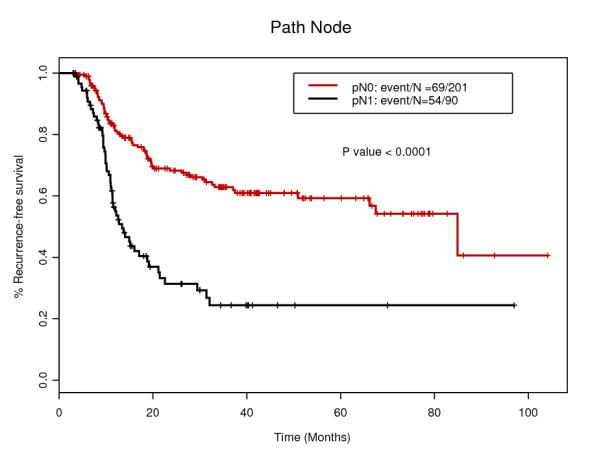

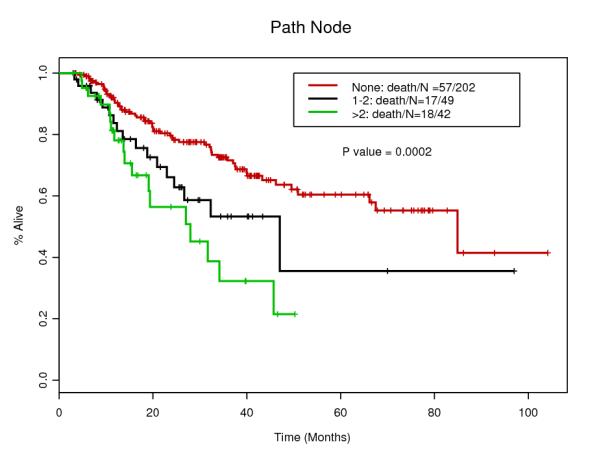

The presence of malignant lymph nodes in the surgical specimen (+ypNodes) after preoperative chemoradiation (trimodality) in patients with esophageal cancer (EC) portends a poor prognosis for overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). There is not one clinical parameter that is correlated with +ypNodes. We hypothesized that a combination of clinical parameters might provide a model that would associate with the high likelihood of +ypNodes in trimodality EC patients.

Methods

We report on 293 consecutive EC patients who received trimodality therapy. A multivariate logistic regression analysis that included pretreatment and post-chmoradiation parameters was performed to identify independent variables that were used to construct a nomogram for +ypNodes in trimodality EC patients.

Results

Of 293 patients, 91 (31.1%) had +ypNodes. In multivariable analysis, the significant factors associated with +ypNodes were: baseline T stage (odds ratio [OR], 7.145; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.381-36.969; p=0.019), baseline N stage (OR, 2.246; 95% CI, 1.024-4.926; p=0.044), tumor length (OR, 1.178; 95% CI, 1.024-1.357; p=0.022), induction chemotherapy (OR, 0.471; 95% CI, 0.242-0.915; p=0.026), lymph metastasis by post-chemoradiation PET (OR, 2.923; 95% CI, 1.007-8.485; p=0.049) and enlarged lymph node metastasis by post-chemoradiation CT (OR, 3.465; 95% CI, 1.549-7.753; p=0.002). The nomogram after internal validation using the bootstrap method yielded a high concordance index of 0.756 (95% CI, xx-xx).

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the constructed nomogram highly correlates with the presence of +ypNodes and upon validation; it could prove useful in individualizing therapy for trimodality patients with EC.

Introduction

Primary surgical resection is still the most frequent strategy to treat localized esophageal cancer (EC) but the 5-year survival rates remain poor 1, 2. In an analysis of 283 EC patients who underwent primary surgery at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 1997 to 2001, the 3-year survival rates for pathologic stage IIA and III were only 44% and 6%, respectively 3. Therefore, surgery alone for EC patients with clinical stage higher than T1BN0 is not recommended. Such patients should be considered for combined modality therapy and preoperative chemoradiation therapy provides the strongest evidence to date (gasst, etc) 4-6.

The prognosis of patients who receive preoperative chemoradiation followed by surgery (trimodality therapy) depends on the residual cancer in the surgical specimen and more importantly, the presence of metastatic lymph nodes (+ypNodes) (refs). One of the most important prognosticators for overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) is the presence of +ypNodes (refs). Although pathologic complete response (pathCR) rate varies among studies (18 to 40%) 5-9, a systemic review of the rate of pathCR after preoperative therapy for esophageal cancer 10 showed 22.0% of median pCR rate from 17 studies with adenocarcinoma and 23.7% from 16 studies with squamous cell carcinoma.

Gaur et al. developed a nomogram associated pathologic LN involvement for esophageal cancer patients treated with surgery alone, using clinical tumor length, clinical tumor depth and clinical nodal status 11 and they concluded that it could be used for selecting patients who are candidate for preoperative combined modality therapy. Since preoperative therapy is now commonly recommended (ref JNCCN-ajani), it would be important to develop a model that is correlated with +ypNodes. One could question our motive to develop such a nomogram and its value. A reliable nomogram could not be immediately implemented but would be instructive. It could provide additional useful clinical information that we currently unable to obtain. In the future, it might complement other approaches where we could avoid surgery in patients who are destined to have numerous +ypNodes and a very short survival.

Here we present a nomogram developed in a large number of patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We searched the prospectively collected esophageal cancer database in the Department of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) and retrospectively reviewed record for patients with biopsy-proven esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer who were treated between 2002 and 2010. 293 consecutive patients treated with trimodality therapy (preoperative CRT and surgery with or without induction chemotherapy) were identified. Patients were included if they had complete pretreatment clinical staging. The Institutional Review Board of MDACC approved this analysis.

Pretreatment Clinical Staging

Preoperative tumor, node and metastasis (TNM) stage was established using a combination of esophageal endoscopy with endoscopic ultrasonography and fine needle aspiration, CT, and PET. The TNM staging criteria used in this study was as defined in the sixth edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system 12. Clinical tumor length was determined by the longest craniocaudal axial length measured on endoscopy.

Preoperative Imaging

CT and/or PET reading reports, which were created by trained radiologists, were reviewed to determine LN involvement retrospectively. Metastatic potential of LN are considered by size greater than 10mm in short axis diameter on CT, metabolic activity with an SUV max of greater than 2.5 on PET and proximity of nodes to primary tumor.

Trimodality Therapy

All patients received concurrent chemotherapy with radiotherapy. Before CRT, 129 (44.0%) patients received induction chemotherapy. The total radiation dose delivered was either 45 grays (Gy) in 25 fraction or 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions, at 1.8 Gy per fraction delivered once per day, 5 days per week. Patients received a fluoropyrimidine and either a taxane or a platinum compound as the second cytotoxic agent during radiation. Five to six weeks after the completion of CRT, all patients underwent comprehensive restaging including blood test, esophageal endoscopy with tumor biopsies, and imaging studies of CT and/or PET and define surgical candidates. Types of esophagectomy included Ivor-Lewis, transthoracic, transhiatal, three-field, and minimally-invasive esophagectomy.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association of pathological LN metastasis with baseline demographic and clinical factors. Regarding multivariate analysis, initially a full multivariate logistic regression model, including all variables with a p value less than 0.15 in the univariate analysis, was fit. Then a backward variable selection procedure was performed to determine the independent covariates. The multivariate logistic model with independent covariates was used to construct nomogram.

The performance of the nomogram was quantified by discrimination and calibration 13. To reduce the overfit bias, the nomogram was subjected to 200 bootstrap resamples for internal validation. The bootstrap estimated corrected concordance index (C-index) was calculated. The C-index estimates the probability of concordance between the observed LN metastases and LN metastases that are predicted from the model. The C-index ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating perfect concordance, 0.5 indicating no better concordance than chance, and 0 indicating perfect discordance. All analyses were performed using SAS software 9.2 (Cary, NC) and R package, version2.12.1, with the design library.

Results

Patients and Tumor Characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 summarize patients and tumor characteristics of the study population. We analyzed 293 patients with esophageal cancer treated with CRT and surgery. The median age was 61 years (range 27-80), and the majority of the patients was male (87.4%) and Caucasian (90.1%). The majority of the tumors was diagnosed clinically T3 (86.7%) and node positive (60.8%). Main histology was adenocarcinoma (91.1%) and others include adenosquamous and undifferentiated carcinoma. 129 patients (44.0%) had induction chemotherapy before CRT. After the surgery, 91 patients (31.1%) actually had LNs involvements. Only 16 patients (5.5%) had Transhiatal esophagectomy which is less invasive, while 226 patients (77.1%) had standard transthoracic approach. Pathological CR was confirmed for 65 patients (22.2%) which rate is compatible with other studies 10.

Table1.

Patient and Tumor Charactaristics

| Number of patients (n=293) | |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis* | 61 (27-80) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 264 (90.1%) |

| African American | 6 (2.0%) |

| Hispanic | 18 (19.4%) |

| Asian | 5 (1.7%) |

| Gender (Male : Female) | 256 : 37 (87.4 : 12.6%) |

| Siewert class | |

| Esophagus | 25 (8.5%) |

| AEGI | 166 (56.7%) |

| AEGII | 102 (34.8%) |

| Baseline T stage | |

| T1 | 1 (0.3%) |

| T2 | 35 (11.9%) |

| T3 | 254 (86.7%) |

| T4 | 3 (1.0%) |

| Baseline N 1 | 178 (60.8%) |

| Baseline M 1 | 14 (4.8%) |

| Clinical Stage | |

| I | 1 (0.3%) |

| II | 121 (41.3%) |

| III | 157 (53.6%) |

| IV | 14 (4.8%) |

| Length of tumor (cm)* | 5 (1-14) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 267 (91.1%) |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 23 (7.8%) |

| Others | 3 (1.0%) |

| Tumor grade | |

| Well | 2 (6.8%) |

| Moderately | 131 (44.7%) |

| Poorly | 160 (54.6%) |

| Induction chemo | 129 (44.0%) |

median (range)

Table2.

Surgical Characterictics

| Number of patients (n=293) | |

|---|---|

| Type of surgery | |

| Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy | 189 (64.5%) |

| Transthoracic esophagectomy | 16 (5.5%) |

| Three-field esophagectomy | 21 (7.2%) |

| Transhiatal esophagectomy | 16 (5.5%) |

| Minimally-invasive esophagectomy | 38 (13.0%) |

| Others | 13 (4.4%) |

| Pathological T stage | |

| T0 | 73 (24.9%) |

| T1 | 44 (15.0%) |

| T2 | 50 (17.1%) |

| T3 | 118 (40.3%) |

| T4 | 8 (2.7%) |

| ypN1 | 91 (31.1%) |

| ypM1 | 1 (3.4%) |

| ypStage | |

| 0 | 65 (22.2%) |

| I | 35 (11.9%) |

| II | 127 (43.3%) |

| III | 65 (22.2%) |

| IV | 1 (3.4%) |

| pCR | 65 (22.2%) |

| Number of positive L/N* | 0 (0-20) |

| Number of total L/N* | 21 (0-52) |

median (range)

Preoperative therapy

The total radiation dose delivered was either 45 or 50.4 Gy. 291 patients (99.3%) received a fluoropyrimidine and 286 patients (97.6%) received either a taxane or a platinum compound as the second cytotoxic agent during radiation. 129 (44.0%) patients received induction chemotherapy before CRT with similar chemotherapy regimen.

Imaging after preoperative chemoradiation

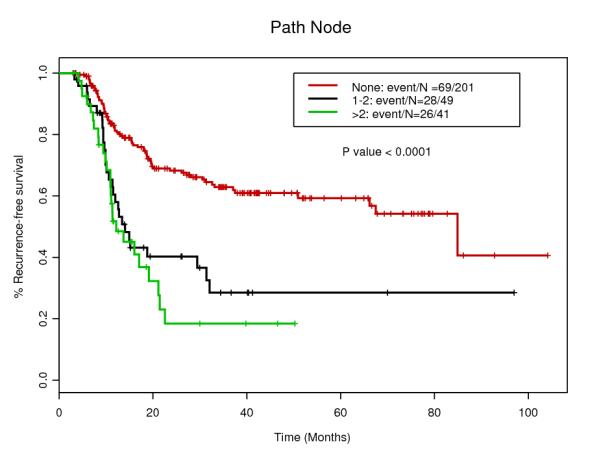

Sensitivities of LN metastasis by CT only and PET only after preoperative CRT were 41.6% and 21.6%, respectively (Fig.1). On the other hand, specificities of these were 85.7% and 93.7%, respectively.

Figure1.

Sensitivity and Specificity of post chemoradiation PET and CT for lymph node metastasis. Sensitivities of both imaging are low (21.6% and 41.6%, respectively), whereas specificities are high (93.7% and 85.7%, respectively).

Logistic regression model and nomogram

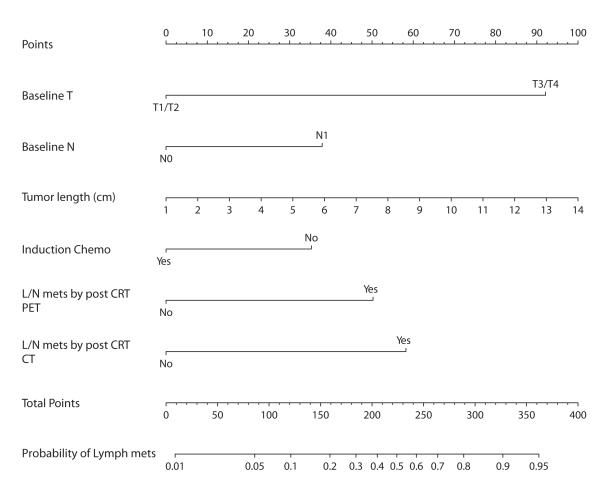

Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between pretreatment and post CRT clinical data and pathological LN involvement (ypN+) (Table 3). In multivariate analyses, ypN+ was independently associated with baseline T3/4 (odds ratio [OR] 7.145, p=0.019), baseline N1 (OR 2.246, p=0.044), longer tumor (OR1.178, p=0.022), absence of induction chemotherapy (OR0.471, p=0.026), post CRT LN metastasis by CT (OR3.465, p=0.002) and PET (OR 2.923, p=0.049). The SUV uptake and biopsy of primary tumor after CRT, as well as age, gender, tumor location, histology were not associated with ypN+. On the basis of the six variables which were independently associated with ypN+, we constructed a nomogram (Fig.2). Internal validation using the bootstrap method showed that the C-index for the model was 0.756.

Table3.

Logistic regression analysis

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P value | Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P value |

| Age | 0.996 | 0.972-1.020 | 0.753 | ||||

| Gender (Female) | 37 | 0.575 | 0.252-1.312 | 0.189 | |||

| Siewert class | 0.483 | ||||||

| Esophageal | 25 | 1.000 | |||||

| AEG 1 | 166 | 1.612 | 0.609-4.213 | 0.336 | |||

| AEG 2 | 102 | 1.258 | 0.456-3.466 | 0.657 | |||

| Baseline T (T3/4) | 257 | 9.006 | 2.114-38.344 | 0.003 | 7.145 | 1.381-36.969 | 0.019 |

| Baseline N (N1) | 178 | 4.505 | 2.457-8.258 | <0.0001 | 2.246 | 1.024-4.926 | 0.044 |

| Baseline M (M1) | 14 | 1.247 | 0.406-3.830 | 0.700 | |||

| Baseline Stage | <0.0001 | ||||||

| I/II | 122 | 1.000 | |||||

| III | 157 | 4.843 | 2.653-8.837 | <0.0001 | |||

| IV | 14 | 3.431 | 1.026-11.475 | 0.045 | |||

| Tumor length | 1.275 | 1.140-1.426 | <0.0001 | 1.178 | 1.024-1.357 | 0.022 | |

|

Histology (non-adeno) |

26 | 0.985 | 0.412-2.357 | 0.973 | |||

|

Tumor Grade (Poorly) |

160 | 1.723 | 1.036-2.865 | 0.036 | |||

| Induction Chemo | 129 | 0.587 | 0.352-0.979 | 0.041 | 0.471 | 0.242-0.915 | 0.026 |

|

SUV uptake of tumor (pre CRT) |

1.014 | 0.986-1.044 | 0.329 | ||||

|

SUV uptake of tumor (post CRT) |

1.042 | 0.981-1.108 | 0.179 | ||||

|

L/N mets by post

CRT PET |

31 | 4.085 | 1.883-8.860 | 0.0004 | 2.923 | 1.007-8.485 | 0.049 |

|

L/N mets by post

CRT CT |

57 | 4.267 | 2.295-7.933 | <0.0001 | 3.465 | 1.549-7.753 | 0.002 |

|

Post CRT tumor

biopsy |

59 | 1.468 | 0.806-2.676 | 0.210 | |||

Figure2.

Nomogram to predict the probability of pathological lymph node metastasis for esophageal cancer patients using pretreatment and post chemoradiation clinical values. (Top) Points are obtained according to prognostic contribution of parameters. (Bottom) Points are translated to probability of pathological lymph node metastasis. The total points score is obtained by summing the points for each covariate of the nomogram which are baseline T, baseline N, tumor length, induction chemo, lymph node metastasis by post chomoradiation PET and CT.

Discussion

The nomogram to predict pathological LN metastasis was developed and validated for the patient with esophageal and GEJ cancer treated with CRT first, and showed high reproducibility with C-index 0.756. This model has a potential to be useful to choose most favorable surgical procedure for the patients with esophageal cancer.

The staging is usually re-evaluated after preoperative therapy by endoscopy and imagings including CT and PET. However, sensitivity of imaging for diagnosing LN involvement is low and the rate of false negative is high. In pretreatment staging, sensitivity of enhanced CT, FDG-PET, FDG-PET/CT are reported 60%, 51%, and 60%, respectively 14, 15. But there is no study about the sensitivity of imaging for LN metastasis from esophageal cancer after CRT. In our study, sensitivity of CT and PET were 41.6 and 21.6% which were quite low. The main factor for determining LN metastasis by CT is the size, which is greater than 10 mm in short axis diameter. However, in the retrospective study with 2969 dissected LNs from 186 esophageal and GEJ cancer patients treated with preoperative CRT, Gu et al. 16 reported that the size of metastatic LNs were measured from 0.5 to 18 mm in greatest dimension. Furthermore, Bollschweiler et al. 17 showed the metastatic LNs after neoadjuvant CRT were significantly smaller than those with surgery only (p=0.031). From these studies, we can assume that there are still certain numbers of metastatic LNs less than 10 mm and they are difficult to be picked up by CT, especially after CRT. It is not surprising that the sensitivity of CT for detecting LN metastasis after CRT is low. We could say same thing about PET and PET/CT. CRT might affect metastatic LN not only in size but also its metabolic activity. At 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting, Waldron et al. presented the results from the study of PET/CT to predict residual node disease after radiation therapy for head and neck cancer patients 18. The sensitivity and specificity of PET/CT were 53% and 65%, respectively and they concluded it was not a reliable indicator. In this analysis, they included only the patients with more than 1 cm residual LN by CT, so the true sensitivity would be lower. Because of low sensitivities, we cannot use either CT or PET to predict ypN+ by itself, although the detections of LN metastasis by CT or PET are the independent predictors of true N+ in multivariate analysis. However, if we combined with other independent values, which are pretreatment tumor depth, node status, tumor length, and induction chemotherapy, we can have more accurate indicator. The actual probability of LN metastasis could be calculated using this nomogram before surgery. To our knowledge, this is the only reliable indicator which can predict ypN+ for esophageal cancer patients with preoperative CRT.

Pretreatment tumor depth, node status, and tumor length were also used for the nomogram predicting pN+ with surgery only esophageal cancer patients 11. Our finding suggests that these three factors and lymph node involvement have a very strong relation, so they remained as independent predictors even after preoperative CRT. Interestingly, induction chemotherapy before CRT was also the independent factor by multivariable analysis. There is no evidence that induction chemotherapy had a benefit for esophageal cancer patients 19, but our results suggested it has a potential to help CRT for eliminating LN metastasis.

For esophageal cancer patients, transthoracic approach, for example Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy with GEJ tumor and two or three-field esophagectomy with upper-middle esophageal tumor, is the most common procedure. This approach improves mediastinum LN dissection and provides more accurate staging after surgery. Moreover, the number of resected LNs and the ratio of metastatic to examined LNs were reported to be independent prognostic factors 20, 21. Another open approach used for esophageal cancer patients is transhiatal esophagectomy. In a randomized study, 220 patients with adenocarcinoma of mid-distal esophageal or gastric cardia were assigned to undergo either tranthoracic or transhiatal esophagectomy 22. The authors showed that transhiatal approach was associated with a shorter duration of surgery (3.5hrs vs. 6.0hrs; p<0.001, a lower blood loss (1.0L vs. 1.9L; p<0.001), and a lower morbidity than transthoracic approach, especially pulmonary complication (27% vs. 57%; p<0.001). However, transthoracic approach resected significantly more number of LNs (16±9 vs. 31±14; p<0.001), and there was a trend toward better 5 year over all survival (29% vs. 39%), although it was not significant. Then, who could receive benefits from less invasive surgery? There is another randomized trial which compared transthoracic and transhiatal esophagectomy 23. Omloo et al. demonstrated that locoregional disease-free survival after surgery for the patients with no LN metastasis was comparable with both approach (89% vs. 86%; p=0.64), while the patients with 1 to 8 positive LNs showed better locoregional disease-free survival with transthoracic than transhiatal approach (64% vs. 23%; p<0.02). Patients could choose the surgical procedure based on the prediction of LN involvement by the nomogram which we created in current study, and obtain better outcomes including complication and survival.

For example, the patient who has 6cm tumor with pretreatment clinical stage T2N1 scores less than 120 points if there is no evidence of LN involvement by post CRT imaging, regardless of induction chemotherapy. In this case, the probability of ypN+ would be less than 10%. This patient could have an advantage of less invasive surgery. On the other hand, even if there is no evidence of LN involvement by post CRT imaging, the patients with 6cm tumor and T3N1 clinical stage without induction chemotherapy scores 205 points, and the probability of ypN+ would be more than 40%. This patient needs en-block LN dissection rather than transhiatal approach. Our nomogram doesn’t include endoscopic biopsy result after preoperative CRT. Therefore, we could use this nomogram for convincing patient to have surgery when clinical evaluation shows clinical CR. Although two randomized trials 24, 25 demonstrated no survival advantage for additional surgery after CRT in esophageal cancer patients with response to preoperative therapy, surgical resection still need to be considered 26. In our study, there were 40 patients who had actual positive nodes out of 174 patients with no evidence of node involvement by post-CRT imaging. Moreover, there were 28 patients with ypN+ out of 139 patients with clinical CR which includes no node involvement by imaging and negative for endoscopic biopsy. We think surgery is necessary to eliminate all cancer cells for now, since we cannot predict clinical CR accurately, especially for the patients with adenocarcinoma.

There are some limitations to current study. First, this is a retrospective study. Second, we performed internal validation for the nomogram and it needs to be validated externally to make sure if it can be applied universally.

In conclusion, we have developed a nomogram which can predict pathological LN metastasis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to predict LN metastasis after preoperative CRT before surgery. Our model could be used for selecting the type of surgical procedure and one of the materials to explain patients about surgical necessity.

Figure3.

Nomogram to assess the possibility of +ypNodes after preoperative chemoradiaton in patients with oesphageal cancer undergoing surgery.

References

- 1.Mariette C, Taillier G, Van Seuningen I, Triboulet JP. Factors affecting postoperative course and survival after en bloc resection for esophageal carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(4):1177–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.02.068. S0003497504004680 [pii] 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.02.068 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice TW, Rusch VW, Apperson-Hansen C, Allen MS, Chen LQ, Hunter JG, Kesler KA, Law S, Lerut TE, Reed CE, Salo JA, Scott WJ, Swisher SG, Watson TJ, Blackstone EH. Worldwide esophageal cancer collaboration. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00901.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19196264, DES901 [pii] 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofstetter W, Swisher SG, Correa AM, Hess K, Putnam JB, Jr., Ajani JA, Dolormente M, Francisco R, Komaki RR, Lara A, Martin F, Rice DC, Sarabia AJ, Smythe WR, Vaporciyan AA, Walsh GL, Roth JA. Treatment outcomes of resected esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):376–384. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00014. discussion 384-375. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12192324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Zalcberg JR, Simes RJ, Barbour A, Gebski V. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5. Epub: S1470-2045(11)70142-5 [pii] 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tepper J, Krasna MJ, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Reed CE, Goldberg R, Kiel K, Willett C, Sugarbaker D, Mayer R. Phase III trial of trimodality therapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, radiotherapy, and surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer: CALGB 9781. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1086–1092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9593. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18309943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh TN, Noonan N, Hollywood D, Kelly A, Keeling N, Hennessy TP. A comparison of multimodal therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):462–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350702. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8672151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courrech Staal EF, Aleman BM, Boot H, van Velthuysen ML, van Tinteren H, van Sandick JW. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97(10):1482–1496. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7175. 10.1002/bjs.7175 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohatgi PR, Swisher SG, Correa AM, Wu TT, Liao Z, Komaki R, Walsh GL, Vaporciyan AA, Rice DC, Bresalier RS, Roth JA, Ajani JA. Histologic subtypes as determinants of outcome in esophageal carcinoma patients with pathologic complete response after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Cancer. 2006;106(3):552–558. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21601. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16353210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallbohmer D, Holscher AH, DeMeester S, DeMeester T, Salo J, Peters J, Lerut T, Swisher SG, Schroder W, Bollschweiler E, Hofstetter W. A multicenter study of survival after neoadjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy and esophagectomy for ypT0N0M0R0 esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2010;252(5):744–749. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fb8dde. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fb8dde [doi] 00000658-201011000-00005 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bollschweiler E, Holscher AH, Metzger R. Histologic tumor type and the rate of complete response after neoadjuvant therapy for esophageal cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6(1):25–35. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.133. 10.2217/fon.09.133 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaur P, Sepesi B, Hofstetter WL, Correa AM, Bhutani MS, Vaporciyan AA, Watson TJ, Swisher SG. A clinical nomogram predicting pathologic lymph node involvement in esophageal cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2010;252(4):611–617. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f56419. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f56419 [doi] 00000658-201010000-00006 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene F, Page D, Fleming I, Fritz A, Balch C, Haller D, Morrow M. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th Edition Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell FE, Jr., Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15(4):361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4 [pii] 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okada M, Murakami T, Kumano S, Kuwabara M, Shimono T, Hosono M, Shiozaki H. Integrated FDG-PET/CT compared with intravenous contrast-enhanced CT for evaluation of metastatic regional lymph nodes in patients with resectable early stage esophageal cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23(1):73–80. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0209-1. 10.1007/s12149-008-0209-1 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Westreenen HL, Westerterp M, Bossuyt PM, Pruim J, Sloof GW, van Lanschot JJ, Groen H, Plukker JT. Systematic review of the staging performance of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18):3805–3812. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.083. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15365078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu Y, Swisher SG, Ajani JA, Correa AM, Hofstetter WL, Liao Z, Komaki RR, Rashid A, Hamilton SR, Wu TT. The number of lymph nodes with metastasis predicts survival in patients with esophageal or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma who receive preoperative chemoradiation. Cancer. 2006;106(5):1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21693. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16456809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollschweiler E, Besch S, Drebber U, Schroder W, Monig SP, Vallbohmer D, Baldus SE, Metzger R, Holscher AH. Influence of neoadjuvant chemoradiation on the number and size of analyzed lymph nodes in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(12):3187–3194. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1196-8. 10.1245/s10434-010-1196-8 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waldron JN, Gilbert RW, Eapen L, Hammond A, Hodson DI, Hendler A, Perez-Ordonez B, Gu C, Julian JA, Julian DH, Levine MN. Results of an Ontario Clinical Oncology Group prospective cohort study on the use of FDG PET/CT to predict the need for neck dissection following radiation therapy of head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl):5504. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javeri H, Arora R, Correa AM, Hofstetter WL, Lee JH, Liao Z, McAleer MF, Maru D, Bhutani MS, Swisher SG, Izzo JG, Ajani JA. Influence of induction chemotherapy and class of cytotoxics on pathologic response and survival after preoperative chemoradiation in patients with carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 2008;113(6):1302–1308. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23688. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18623381, 10.1002/cncr.23688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariette C, Piessen G, Briez N, Triboulet JP. The number of metastatic lymph nodes and the ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors in esophageal cancer regardless of neoadjuvant chemoradiation or lymphadenectomy extent. Ann Surg. 2008;247(2):365–371. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815aaadf. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815aaadf [doi] 00000658-200802000-00024 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizk NP, Ishwaran H, Rice TW, Chen LQ, Schipper PH, Kesler KA, Law S, Lerut TE, Reed CE, Salo JA, Scott WJ, Hofstetter WL, Watson TJ, Allen MS, Rusch VW, Blackstone EH. Optimum lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2010;251(1):46–50. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b2f6ee. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b2f6ee [doi] 00000658-201001000-00007 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, Wijnhoven BP, Tijssen JG, Fockens P, Stalmeier PF, ten Kate FJ, van Dekken H, Obertop H, Tilanus HW, van Lanschot JJ. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1662–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022343. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12444180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omloo JM, Lagarde SM, Hulscher JB, Reitsma JB, Fockens P, van Dekken H, Ten Kate FJ, Obertop H, Tilanus HW, van Lanschot JJ. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the mid/distal esophagus: five-year survival of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246(6):992–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c4037. discussion 1000-100110.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c4037 [doi] 00000658-200712000-00011 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedenne L, Michel P, Bouche O, Milan C, Mariette C, Conroy T, Pezet D, Roullet B, Seitz JF, Herr JP, Paillot B, Arveux P, Bonnetain F, Binquet C. Chemoradiation followed by surgery compared with chemoradiation alone in squamous cancer of the esophagus: FFCD 9102. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(10):1160–1168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7118. 25/10/1160 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7118 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahl M, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, Meyer HJ, Walz MK, Seeber S, Klump B, Budach W, Teichmann R, Schmitt M, Schmitt G, Franke C, Wilke H. Chemoradiation with and without surgery in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2310–2317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.034. 23/10/2310 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.034 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenzie S, Mailey B, Artinyan A, Metchikian M, Shibata S, Kernstine K, Kim J. Improved outcomes in the management of esophageal cancer with the addition of surgical resection to chemoradiation therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;18(2):551–558. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1314-7. 10.1245/s10434-010-1314-7 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]