Abstract

Studies of Asian-American adults have found high estimates of problematic gambling. However, little is known about gambling behaviors and associated measures among Asian-American adolescents. This study examined gambling perceptions and behaviors and health/functioning characteristics stratified by problem-gambling severity and Asian-American and Caucasian race using cross-sectional survey data of 121 Asian-American and 1,659 Caucasian high-school students. Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents significantly differed on problem-gambling severity, with Asian-American adolescents more often reporting not gambling (24.8% vs. 16.4%), but when they did report gambling, they showed higher levels of at-risk/problem gambling (30.6% vs. 26.4%). Parental approval or disapproval of adolescent gambling also significantly differed between races, with Asian-American adolescents more likely to perceive both parental disapproval (50.0% vs. 38.2%) and approval (19.3% vs. 9.6%) of gambling. Asian-American adolescents were also more likely to express concern about gambling among close family members (25.2% vs. 11.6%). Among Asian-American adolescents, stronger associations were observed between at-risk/problem gambling and smoking cigarettes (interaction odds ratio=12.6). In summary, differences in problem-gambling severity and gambling perceptions indicate possible cultural differences in familial attitudes towards gambling. Stronger links between cigarette smoking and risky/problematic gambling amongst Asian-American adolescents suggest that prevention and treatment efforts targeting youth addictions consider cultural differences.

Keywords: gambling, adolescence, Asian American, family

1. Introduction

High rates of gambling and gambling-related problems exist among adolescents (Barnes et al., 2009; Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of Pathological Gambling, 1999; Fisher, 1999; Molde et al., 2009; Shaffer et al., 1999; Volberg et al., 2010; Welte et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2011). An early meta-analysis of gambling studies in North America estimated 3.2% to 8.4% of youth experience past-year gambling problems (Shaffer et al., 1999). While gambling is often considered an adult behavior, the prevalence of pathological gambling among adolescents is about three times that reported for adults (Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of Pathological Gambling, 1999; Shaffer et al., 1999).

Onset of gambling prior to adulthood has been associated with social, psychiatric, and substance use problems in adulthood (Burge et al., 2006; Lynch et al., 2004). Both problematic and recreational gambling have been linked to adverse mental health and social functioning in adolescence, with associations observed with poor school performance, drug use, and difficulties with mood and aggression (Lloyd et al., 2010; Yip et al., 2011). Therefore, development of targeted and effective education programs, prevention initiatives, and treatment efforts relating to youth gambling is important from public and mental health perspectives.

Most studies on gambling have been conducted in Western countries, involving predominantly Caucasian participants. Available evidence from adults suggests that problem gambling may be more prevalent among racial/ethnic minority groups (Barry et al., 2011a; Barry et al., 2011b; Fisher, 1999; Kessler et al., 2008; National Opinion Research Center, 1999). A 2001–2002 U.S. national survey found prevalence rates of disordered gambling among African-American (2.2%) and Native- and Asian-American adults combined (2.3%) to be higher than that of Caucasian adults (1.2%; Alegria et al., 2009). Amongst callers to a gambling helpline, Asian-American adults with gambling problems were more likely than Caucasian adults to report gambling-related suicidality and non-strategic gambling problems and less likely to report alcohol-use problems (Barry et al., 2009). Amongst university students, Asian-American students more frequently exhibited pathological gambling (12.5%) compared to African-American, Native-American, and Caucasian students (4–5%; Lesieur et al., 1991). A recent study of Chinese-American high-school students in California estimated past-year prevalence of problem gambling to be 10.9% (Chiu and Woo, 2012). These studies suggest more research is needed to understand gambling-related attitudes and behaviors amongst Asian-American youth.

The few studies of U.S. youth have found that similar to adults, members of certain racial/ethnic minority groups appear more likely to gamble and exhibit gambling-related problems than Caucasian youth (Goldstein et al., 2009; Raylu and Oei, 2004; Stinchfield, 2000; Westphal et al., 2000). However, studies on gambling of Asian-American adolescents have shown mixed findings, with some studies reporting that Asian-American students gamble less frequently than other racial/ethnic minority youth (Stinchfield et al., 1997; Welte et al., 2008), which have led some researchers to argue that Asian-American gambling is a stereotype not supported by research. However, others have found that Asian-American youth are more likely to engage in problematic gambling compared to non-Asian-American youth (Chiu and Woo, 2012; Forrest and McHale, 2011; Moore and Ohtsuka, 2001; Westphal et al., 2000), leading to the claim that Asian-American youth constitute a group susceptible to risky gambling behaviors. Similarly, British (Moore and Ohtsuka, 2001) and Australian (Forrest and McHale, 2011) studies have found higher rates of problematic gambling among adolescents from Asian descent compared to those from Anglo-Europeans backgrounds.

There are several important reasons to focus on gambling problems among Asian-American youth. Asian Americans constitute one of the fastest growing racial minority groups in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau., 2007). High rates of pathological gambling have been found among Asian-American adults contrary to the model minority myth that Asian Americans are problem-free (Fong and Tsuang, 2007). Gambling is often seen as a form of entertainment (Loo et al., 2008), and various marketing strategies have specifically targeted Asian groups (Chen, 2011; Dyall et al., 2009), which has led some to term Asian culture as “gambling-permissive.” (Kim, 2012).

If Asian-American youth grow up in households that share more permissible attitudes toward gambling and where parents may also engage in frequent gambling behaviors, Asian-American youth may also be at particular risk for gambling problems (Delfabbro and Thrupp, 2003; Vachon et al., 2004). According to the social learning theory, gambling behaviors and values of adolescents can be imitated or learned through vicarious learning or modeling from their family (Brown, 1987; Gupta and Derevensky, 1997). Adolescent perceptions of their environment are an important predictor for involvement in their actual behaviors, including gambling (e.g., Felsher et al., 2003; Hardoon et al., 2004; Wickwire et al., 2007). Compelling evidence shows that adolescents’ reports of parents such as parental problematic gambling behaviors (Gupta and Derevensky, 1997) and pro-gambling attitudes by parents is associated with their gambling behaviors (Delfabbro and Thrupp, 2003). Hence, Asian-American adolescent perceptions of familial and peer gambling warrant study.

1.1. Aims

We aimed to examine gambling behaviors and associated health, functioning, and risk behaviors among Asian-American and Caucasian high-school students. Our aim was to assess the association between at-risk/problem gambling (ARPG) and Asian American race in the adolescent sample. Based on previous adult and adolescent studies discussed above, we posed two opposing hypotheses: (1) Asian-American high-school adolescents would be more likely than Caucasian adolescents to exhibit ARPG based on DSM-IV criteria and (2) ARPG between Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents would not differ. We also examined whether cultural differences existed in adolescent gambling behavior. Specifically, we hypothesized that Asian-American adolescents would be more likely than Caucasian adolescents to endorse parental approval of gambling and concerns about close family members gambling. We also explored the relationship between ARPG and alcohol use to assess whether findings observed among Asian-American adults relating gambling problems with non-strategic gambling and less alcohol-use problems (Barry et al., 2009) would be present amongst Asian-American youth.

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Study Procedures

Data were derived from a survey of high-school students (grades 9 to 12); recruitment and study procedure have been described previously (Potenza et al., 2011; Schepis et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2011). In brief, all public 4-year high schools in Connecticut were invited to participate. After obtaining permission from School Boards and/or school system superintendents, the survey was administered in 10 schools. These schools represent each of the three tiers of the state’s district reference groups (DRGs). DRGs are groupings of school based on the socioeconomic status of the families in the school district. Thus, sampling from each of the three tiers of the DRGs creates a more socioeconomically representative sample.

Passive consent procedures were used to obtain consent from parents. Specifically, letters were sent through the school to parents informing them about the study and outlining the procedure by which they could deny permission for their child to participate in the survey. If no message was received from a parent, parental permission was assumed. All study procedures were approved by the participating schools and by the institutional review board of the Yale University School of Medicine.

Each school was visited on a single day by the research staff who explained the voluntary, anonymous, and confidential nature of the study and administered to all students willing to participate.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1

Demographic characteristics such as gender, school grade and grade average were assessed. Participant’s race was assessed by asking, “What is your racial background?” The choices included, “African American/Black,” “White/Caucasian,” “Asian,” and “Other.” Family structure was also assessed by asking whether the participant lived with “one parent”, “two parents”, or “other” (“foster family,” “grandparents,” “other relatives,” and “other”).

2.2.2

Gambling perceptions held by family and peers, as reported by participants, were assessed regardless of participants’ gambling behaviors. Participants reported whether their parents would approve or disapprove of their gambling (parental perception of gambling) and the responses were grouped into three categories: “disapprove” (combining “strongly disapprove” and “disapprove”), “approve” (combining “strongly approve” and “approve”) and “neither approve nor disapprove.” Perception of problematic family gambling was assessed with the question, “Has the gambling of a close family member caused you worry or concern?” The responses were dichotomized to “yes/no.” Perception of peer gambling was assessed with the question, “How many of your peers do you think gamble too much?” The responses were dichotomized to “none” and “1 or more.” Feeling peer pressure to gamble was assessed with a dichotomous response, “never” and “once or more.”

2.2.3

Problem-gambling severity was categorized into three groups using a similar method by Potenza et al. (2011): non-gambling (NG: no gambling activity in the past year), low-risk gambling (LRG: past-year gambling but no inclusionary criteria for pathological gambling based on the DSM-IV criteria), and at-risk/problem gambling (ARPG: one or more past-year inclusionary criteria for pathological gambling based on the DSM-IV criteria).

2.2.4

Health/functioning variables were categorized into extracurricular activities, substance use, mood, and aggression (Yip et al., 2011).

2.2.4.1. Extracurricular activities

Extracurricular activity involvement was acknowledged if an adolescent reported engaging in one or more activities of community service, volunteer work, team sports, school clubs, and church activities at least 1–2 times-a-month or having a paid part-time job.

2.2.4.2. Substance use

Life-time substance use was assessed by asking, “Have you ever smoked a cigarette/marijuana/had a sip of alcohol/used designer or other drugs, such as Ecstasy, GHB, Special K, or cocaine?” All responses were coded dichotomous “yes/no.” Past-30-day use of alcohol was assessed among those who had a sip of alcohol, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?” and responses were coded as “never” and “more than one.” Current caffeine use was assessed by asking, “On average, how many servings of caffeine drinks do you drink a day?” and responses were coded as “none,” “1–2 drinks,” and “3 or more drinks per day.”

2.2.4.3. Mood

Dysphoria/depression was assessed using dichotomous “yes/no” response to the question, “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?”

2.2.4.4. Aggression

Aggression was assessed by asking whether a participant carried a weapon in the past 30 days or got into a serious fight that he/she had to be treated by a doctor or nurse in the past year. Responses to both questions were assessed with dichotomous “yes/no”.

2.2.4.5. Weight

The responses to questions on height and weight were used to calculate body mass indexes, which were then categorized into four weight categories (normal, underweight, overweight, obese).

2.2.5

Gambling variables, which include gambling locations, partners, frequency, form, motivations, time spent on gambling, and age of onset were assessed using the predetermined categories used in other gambling studies with adolescents (Potenza et al., 2011; Yip et al., 2011). Forms of gambling included strategic (such as betting on pool or other game of skills), non-strategic (such as lottery), and machine (such as slot machine). Gambling location was categorized into online gambling, casino gambling and gambling on school grounds. Gambling forms and locations were not mutually exclusive.

Items assessing gambling motivations were grouped into four categories: gambling for excitement, financial reasons, to escape/relieve dysphoria, and social reasons. Gambling motivation in each category was dichotomously scored (“yes/no”) and any endorsement of the items in each category was scored “yes.” Gambling urge was also dichotomously scored if a participant responded “yes” to either, “Do you ever feel pressure to gamble when you do not gamble?” and “In the past year have you ever experienced a growing tension or anxiety that can only be relieved by gambling?” Gambling partners were categorized into gambling with adults, family, friend, stranger, and alone. Time spent gambling on an average week was coded “1 hour or less” versus anything more than one hour and age of onset of gambling was obtained.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed with selected data of respondents acknowledging Asian race and those acknowledging only Caucasian race using SAS version 9.3 (Lloyd et al., 2010). We also conducted all multivariate models excluding Asians who indicated other race (n = 23) and detected comparable findings. “Asian only” and “Asian + another race” groups did not differ on demographic, substance use, and gambling variables, with the exception of one variable: “Asians + another race” were more likely to report using other drugs than “Asian only” group (35% vs. 15%, p =.04). However, this difference does not affect our current findings because odds ratio could not be calculated in the comparison between the gambling groups and other drug use because of low number of individuals endorsing other drug use in the “Asian only” group. Based on these analyses, we decided to present the findings including “Asian and other” race.

Chi-square tests were used to examine the bivariate associations between problem-gambling severity and demographic characteristics, health, functioning, risk behaviors, and gambling variables, separately for Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents (see Tables S1–S2). Chi-square tests were also conducted to examine whether Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents differed in problem-gambling severity and gambling-related perceptions.

Next, we used multivariate-adjusted logistic regression models to examine the associations between problem-gambling severity (ARPG, LRG and NG) and health/functioning variables separately for Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents to assess race-specific effects. Then, we determined whether these effects differed across race groups by fitting an interaction model with the entire sample, which included problem-gambling severity by race. The significance of the interaction was determined by examining the interaction odds ratio, which is the ratio of the race-specific effects. Then, a similar approach involving only respondents who reported past-year gambling was used to examine the relationships between problem-gambling severity (ARPG, LRG) and gambling measures within and across race groups. All logistic regression models adjusted for gender, grade, Hispanic ethnicity, grade average, and family structure.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic variables

Only respondents providing information used to categorize problem-gambling severity and were either Asian-American or Caucasian (1,780 of the 4,523 total respondents) were included in analyses. The final sample consisted of 121 (38.60% females) Asian-American and 1,659 (42.63% females) Caucasian adolescents. Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents did not differ on gender (p =0.40), grade (p=0.09), and grade average (p=0.72). The two race groups differed in family structure, with a larger proportion of Asian-American students reporting “other” living arrangement compared to their Caucasian peers (χ2=57.19, p < 0.001; 18.49% vs. 3.53%).

3.2. Problem-gambling severity

There were differences between race and gambling-problem severity (χ2=8.59, p = 0.01). Higher proportions of Asian-American (versus Caucasian) adolescents acknowledged NG (24.79% vs. 16.40%) and ARPG (30.58% vs. 26.40%) and a lower proportion reported low-risk gambling (44.63% vs. 57.17%). We also assessed the association between race and gambling-problem severity with more defined DSM-IV endorsed gambling criteria (non-gambling, low-risk gambling [endorsing 0 DSM-IV criteria], at-risk gambling [endorsing 1–2 criteria], problem gambling [endorsing 3–4 DSM-IV criteria], pathological gambling [endorsing 5 of more DSM-IV criteria]) and found significant differences, χ2=32.52, p < 0.001. Specifically, we found that compared to Caucasian adolescents, Asian-American adolescents were less likely to report NG (24.79% vs. 16.40%) and more likely to report pathological gambling (13.22% vs. 3.74%). Low-risk (44.63% vs. 57.60%) and at-risk gambling (13.22% vs. 17.96%) appeared to be higher among Caucasian than Asian-American adolescents. The rates of problem gambling were comparable (4.13% vs. 4.70%).

When problem-gambling severity was compared on sociodemographic variables, similar patterns emerged within Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents. For both races, problem-gambling severity was associated with gender and reported grade average, with the likelihood of being a female and having a higher reported grade average lower for the LRG and ARPG groups compared to the NG group, and being a male and having a lower reported grade average higher for LRG and ARPG groups than NG group (Table 1). Family structure was related to problem-gambling severity among Asian-American but not among Caucasian adolescents, with the Asian-American ARPG group frequently acknowledging living with family members other than their parents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of demographic variables among gambling groups separated by race

| Variable | Asian-American (n=121) | Caucasian (n=1,659) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG | LRG | ARPG | X2 | p | NG | LRG | ARPG | X2 | p | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||||

| Gender | 11.43 | 0.003 | 140.89 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 11 | 37.93 | 32 | 62.75 | 27 | 79.41 | 104 | 38.52 | 493 | 52.28 | 349 | 80.05 | ||||

| Female | 18 | 62.07 | 19 | 37.25 | 7 | 20.59 | 166 | 61.48 | 450 | 47.72 | 87 | 19.95 | ||||

| Grade | 5.23 | 0.51 | 12.67 | 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| 9 th | 5 | 16.67 | 20 | 37.04 | 10 | 28.57 | 67 | 24.63 | 259 | 27.35 | 132 | 30.14 | ||||

| 10 th | 11 | 36.67 | 14 | 25.93 | 12 | 34.29 | 65 | 23.90 | 251 | 26.50 | 104 | 23.74 | ||||

| 11 th | 11 | 36.67 | 15 | 27.78 | 8 | 22.86 | 91 | 33.46 | 255 | 26.93 | 101 | 23.06 | ||||

| 12 th | 3 | 10.00 | 5 | 9.26 | 5 | 14.29 | 49 | 18.01 | 182 | 19.22 | 101 | 23.06 | ||||

| Age | 2.07 | 0.72 | 4.31 | 0.37 | ||||||||||||

| <14 | 5 | 33.33 | 14 | 20.90 | 5 | 33.33 | 25 | 12.95 | 145 | 16.61 | 32 | 16.75 | ||||

| 15–17 | 5 | 33.33 | 32 | 47.76 | 6 | 40.00 | 120 | 62.18 | 504 | 57.73 | 101 | 52.88 | ||||

| 18+ | 5 | 33.33 | 21 | 31.34 | 4 | 26.67 | 48 | 24.87 | 224 | 25.66 | 58 | 30.37 | ||||

| Grade Average | 9.99 | 0.04 | 21.70 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| A+B | 24 | 85.71 | 29 | 55.77 | 17 | 50.00 | 169 | 63.53 | 552 | 59.10 | 216 | 50.70 | ||||

| C | 2 | 7.14 | 17 | 32.69 | 12 | 35.29 | 70 | 26.32 | 289 | 30.94 | 136 | 31.92 | ||||

| D+F | 2 | 7.14 | 6 | 11.54 | 5 | 14.71 | 27 | 10.15 | 93 | 9.96 | 74 | 17.37 | ||||

| Family structure | 11.93 | 0.02 | 3.16 | 0.53 | ||||||||||||

| 1 parent | 5 | 17.24 | 12 | 22.22 | 2 | 8.33 | 49 | 18.15 | 200 | 21.28 | 86 | 19.95 | ||||

| 2 parents | 21 | 72.41 | 36 | 66.67 | 20 | 55.56 | 214 | 79.26 | 708 | 75.32 | 326 | 75.64 | ||||

| Other | 3 | 10.34 | 6 | 11.11 | 13 | 36.11 | 7 | 2.59 | 32 | 3.40 | 19 | 4.41 | ||||

Note: NG=nongamblings, LRG=low-risk gambling, ARPG=at-risk/problem gambling

3.3. Gambling perceptions

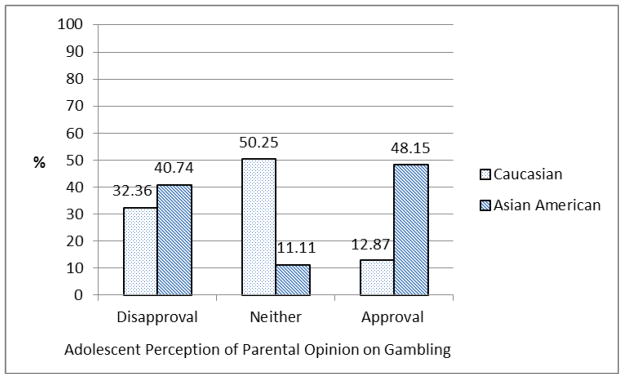

Perceptions of parental approval or disapproval of adolescent gambling differed between groups (X2=18.11, p<0.001), with more Asian-American (vs. Caucasian) adolescents reporting both parental disapproval (50.00% vs. 38.19%) and approval of their gambling (19.32% vs. 9.63%), and fewer Asian-American adolescents reporting neither parental approval nor disapproval of their gambling (30.68% vs. 52.18%). Asian-American adolescents acknowledging ARPG reported higher level of perceived parental approval of gambling than Caucasian adolescents (Figure 1; X2=28.05, p<0.001). More Asian-American adolescents than Caucasian adolescents reported having concern about gambling among close family members (X2=17.16, p<0.001, 25.23% vs. 11.55%). Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents did not differ on being pressured to gamble by peers (X2=0.01, p=0.98) and thinking that their peers gambled too much (X2=1.22, p=0.27).

FIGURE 1.

Perceptions of parental opinion on adolescent gambling among at-risk/problem gambling groups separated by race.

3.4. Health/functioning variables

3.3.1. Extracurricular activities

For both races and in comparison to NG, both LRG and ARPG were associated with participation in extracurricular activities.

3.3.2. Substance use and aggressive behaviors

A significant interaction showed that the association between ARPG and smoking cigarettes was stronger amongst Asian-American adolescents, compared to Caucasian adolescents (OR=12.56). For both Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents, compared to NG, ARPG was positively associated with ever trying marijuana and alcohol, drinking 3 or more cups of coffee per day, and carrying weapons. Amongst Caucasian adolescents, compared to NG, ARPG was also associated with past 30-day-use of alcohol, lifetime use of other drugs, and serious fights; LRG was associated with lifetime use of cigarettes, marijuana, and alcohol, past 30-day-use of alcohol, coffee drinking, and carrying weapons. Comparisons between problem-gambling severity and “other drug” and “past-30-day use of alcohol” could not be made amongst Asian-Americans because only one NG Asian-American adolescent reported past 30-day-use of alcohol and none of the NG Asian-Americans reported using other drugs.

3.3.3. Mood and weight

No associations were found between problem-gambling severity and BMI in either Asian-American or Caucasian adolescents. Amongst Asian-American adolescents, depressed mood was not associated with problem-gambling severity, but among Caucasian adolescents, ARPG and LRG were more strongly associated with depressed mood than was NG.

3.5. Gambling variables

Table 3 describes the multivariate-adjusted associations comparing ARPG to LRG for each race, as well as the interaction between Asian-American/Caucasian race and problem-gambling severity on gambling characteristics. Although ARPG was associated with multiple gambling variables in both Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents, the lack of interaction odds ratios indicate that the relationships between problem-gambling severity and gambling characteristics were similar across racial groups.

Table 3.

Multivariate-adjusted associations between gambling groups and health/functioning measures for Asian-American and Caucasian adolescents

| Asian-American | Caucasian | Interaction OR (Asian-American vs. Caucasian) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARPG vs. LRG | ARPG vs. LRG | ||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Form of gambling | |||

| Strategic | 0.83 (0.04, 20.08) | 7.45 (1.74, 31.91) | 0.13 (0.01, 2.31) |

| Non-strategic | 1.33 (0.41, 4.32) | 1.72 (1.26, 2.34) | 0.78 (0.28, 2.22) |

| Machine | 1.96 (0.59, 6.47) | 2.21 (1.71, 2.86) | 0.99 (0.34, 2.83) |

| Location of gambling | |||

| Online | 6.07 (1.47, 25.01) | 2.94 (2.18, 3.96) | 1.95 (0.61, 6.27) |

| School grounds | 7.06 (1.98, 25.11) | 4.37 (3.31, 5.77) | 1.49 (0.47, 4.71) |

| Casino | 3.20 (0.68, 15.19) | 4.42 (2.81, 6.96) | 0.75 (0.20, 2.78) |

| Gambling motivations | |||

| Excitement | 1.61 (0.47, 5.46) | 3.05 (2.21, 4.21) | 0.57 (0.18, 1.79) |

| Finance | 2.24 (0.75, 6.67) | 3.58 (2.70, 4.75) | 0.68 (0.24, 1.89) |

| Escape | 2.23 (0.75, 6.63) | 2.54 (1.95, 3.32) | 1.11 (0.40, 3.03) |

| Social | 0.96 (0.31, 2.97) | 1.83 (1.41, 2.36) | 0.60 (0.22, 1.61) |

| Gambling urges | |||

| Pressure to gamble | 3.07 (0.22, 42.23) | 3.42 (2.19, 5.34) | 0.82 (0.13, 5.06) |

| Anxiety relieved by gambling | -- | 12.94 (5.79, 28.95) | 0.57 (0.05, 6.47) |

| Gambling partners | |||

| Adults | 1.50 (0.41, 5.56) | 2.98 (2.25, 3.94) | 0.76 (0.25, 2.26) |

| Family | 0.98 (0.34, 2.82) | 1.89 (1.46, 2.43) | 0.56 (0.21, 1.49) |

| Friends | 1.35 (0.42, 4.34) | 1.83 (1.33, 2.52) | 0.50 (0.18, 1.43) |

| Strangers | 8.22 (1.10, 61.57) | 4.68 (2.91, 7.54) | 0.99 (0.21, 4.68) |

| Alone | 2.32 (0.47, 11.39) | 4.20 (2.68, 6.59) | 0.51 (0.13, 1.97) |

| Time spent gambling | |||

| >1 hr/week | 4.41 (0.52, 37.16) | 4.61 (3.20, 6.62) | 0.64 (0.16, 2.65) |

| Age of onset of gambling | |||

| <8 | ref | ref | ref |

| 9–11 | 4.39 (0.46, 42.43) | 0.98 (0.61, 1.59) | 1.51 (0.28, 8.57) |

| 12–14 | 0.46 (0.07, 3.24) | 0.73 (0.48, 1.12) | 0.30 (0.06, 1.44) |

| 15+ | 0.86 (0.13, 5.60) | 0.52 (0.33, 0.81) | 1.10 (0.24, 4.96) |

Note: NG=non-gambling, LRG=low-risk gambling, ARPG=at-risk/problem gambling. Model covariates include gender, grade, grade average, Hispanic ethnicity, and family structure. OR= odds ratio, CI=confidence interval. “No” was the reference group unless otherwise indicated.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the gambling-related perceptions and behaviors, and health/functioning characteristics of problem-gambling severity in Asian-American high-school students. Compared to Caucasian adolescents, Asian-American adolescents more frequently reported not gambling and at-risk/problem gambling (ARPG). Within ARPG, we found that Asian-American adolescents were more likely than Caucasian adolescents to meet the DSM-IV criteria for Pathological Gambling. These findings clarify our research question and provide support for previous findings that youth of Asian descent gamble less frequently, but when they do gamble, they experience greater problematic gambling than Caucasian adolescents (Moore and Ohtsuka, 2001) and that Asian-American adults are less likely to gamble compared to the general population but have higher rates of problematic gambling (Kim, 2012). These findings suggest that amongst individuals of Asian descent, those who choose to gamble may be at particularly high risk of developing gambling problems, and this propensity is evident during pre-adult developmental stages.

Gambling perceptions also differed between Asian-American and Caucasian respondents. Compared to Caucasian adolescents, Asian-American adolescents were more likely to perceive both parental disapproval and approval of gambling, suggesting that Asian-American families may have extreme views on gambling (ranging from prohibition to leniency), which may in part explain the different frequencies in groups problem-gambling-severity groups in Asian-American versus Caucasian groups.

Disapproval of gambling by Asian-American parents may result from awareness of the potential negative consequences of gambling for other family members or themselves and wishes to protect their children. Parents who approve of adolescent gambling may themselves engage in gambling as gambling is often regarded as a form of entertainment in Asian cultures (Loo et al., 2008). For example, in Chinese culture, games such as Mahjong are often played in family and social gatherings where adolescents may be taught how to play. We also found that Asian-American youth were more likely to report concern about gambling of a close family member than were Caucasian adolescents, which is important because it may represent exposure to gambling from family members. All of these may in part be related to ARPG among Asian-American adolescents because parental gambling and lack of parental disapproval of gambling are associated with child gambling and problem gambling among Asian youth (Forrest and McHale, 2011).

Asian-American youth have been termed a “model minority” because they are often well-adjusted, financially stable, and without mental health problems (Wong et al., 1998). However, our data suggest that Asian-American adolescents may exhibit a bimodal distribution with respect to problematic behaviors. In the case of gambling, many Asian-American adolescents do not gamble, but there is a group that seems to be at high risk for gambling problems.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not observe differential associations between alcohol use or non-strategic gambling and problem-gambling severity across race groups. In conjunction with prior findings showing differences in alcohol-use problems and non-strategic gambling in Asian-American and Caucasian adult callers to a gambling helpline (Barry et al., 2009), the findings suggest that such differences may emerge later during development. However, a stronger relationship between problem-gambling severity and cigarette smoking was observed in Asian-American as compared to Caucasian adolescents. The link between smoking cigarettes and ARPG amongst Asian-American youth may be explained by cultural factors. Prior findings indicated that smoking in the homes by family members and house guests is more acceptable in Asian-American households (Cunningham-Williams and Hong, 2007) and therefore, Asian-American adolescents who engage in risk behaviors such as ARPG may be more susceptible to the influences of permissible smoking attitudes. Given the association between ARPG and cigarette smoking amongst Asian-American youth, prevention and cessation interventions targeting both risk behaviors at the individual level, as well as at the family level, may be warranted.

There were multiple similarities in the correlates of problem-gambling severity amongst Asian-American and Caucasian youth. Consistent with the literature on adolescent gambling, ARPG amongst Asian-American adolescents was associated with being male, engaging in substance use and other risky behaviors such as carrying weapons, and having poor school grades (Potenza et al., 2011; Yip et al., 2011). These similarities indicate that the popularity of gambling activities may not only depend on broader cultural context but also other factors (e.g., ones linked to aggression and impulsivity across racial groups).

This study has several limitations. This study was a secondary analysis of self-reported risk behaviors of high-school students using a survey study, and our data did not permit us to examine the racial and cultural diversity within Asian-American adolescents or the extent to which acculturation is associated with gambling behaviors. We also did not directly assess parental opinions of adolescent gambling and their own gambling behaviors. It is possible that Asian-American adolescents’ perceptions of their parents and family gambling may be biased. However, our data indicate that Asian-American youth reported both perceptions of parental disapproval and approval of gambling, suggesting that strong cultural biases are not likely substantial. Despite the lack of confirmation from parents, there is a substantial body of literature indicating that adolescents’ perception of their environment is an important predictor for involvement in their actual behaviors including gambling (e.g., Wickwire et al., 2007; Felsher et al., 2003; Hardoon et al., 2004).

It is important to note that assessing gambling behaviors and values directly from parents may also be biased. If Asian parents gamble frequently and gambling is part of their culture, then Asian parents may be less inclined to report problematic gambling and disapproval of their children gambling. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to study whether Asian-American adolescent’s perceptions of their parents’ gambling coincide with their parents’ actual opinions and gambling behaviors. This is an empirical question that should be tested in future studies. Another important line of research includes assessing both self-reported gambling problems and actual gambling behavior in an experimental task to examine for possible biases in responses.

The sample size of Asian Americans (n=121) included in this study was smaller compared to the number of Caucasians (n=1,659). As a result, we could not compare past-30-day use of alcohol and lifetime use of other drugs among Asian-American youth because of the small number of individuals endorsing these behaviors, especially among non-gamblers. Thus, larger studies are warranted with more comparable and generalizable samples of Asian-American youth and comparison individuals. Larger sample sizes could allow for investigation of other relevant factors (such as gender-related differences relating to gambling in Asian-American and Caucasian youth), and replication of the current study would provide greater support of their generalizability. Given the small sample of Asian American youth in the current study, findings should be interpreted with caution.

Another important limitation of this study relates to the representativeness of the sample. The data were drawn from Connecticut public high-school students. The results, therefore, do not include students enrolled in private schools, those from other states, and students who are frequently absent from school or have dropped out of school. Adolescents who have dropped out of school are more likely to have gambling problems than students attending schools (Welte et al., 2008). Therefore, had school dropouts been included, ARPG frequency may have been different (and likely higher) than that reported here.

Strengths of this study include examination of gambling perceptions and correlates of problem-gambling severity in Asian-American adolescents. This racial group has been inadequately examined because of insufficient numbers of participants, precluding meaningful comparisons between specific racial/ethnic groups (Jacobs, 2000; Raylu and Oei, 2004). The need for research on gambling behaviors among the growing Asian-American youth population is important to better understand different factors in the initiation and maintenance of gambling behaviors and culture-specific processes relating to gambling. Such an understanding should inform the generation of improved prevention and treatment strategies relating to youth gambling.

In summary, this study adds to the scarcity of literature on gambling behaviors among Asian-American adolescents. The current study underscores the importance of greater prevention and intervention efforts targeting gambling behaviors among Asian-American adolescents. Future studies should also examine how these efforts may also decrease cigarette smoking amongst Asian-American youth.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Multivariate-adjusted associations between gambling groups and health/functioning measures for Asian American and Caucasian adolescents

| Variable | Asian-American | Caucasian | Interaction OR (Asian-American vs. Caucasian) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARPG vs. NG | LRG vs. NG | ARPG vs. NG | LRG vs. NG | ARPG vs. NG | LRG vs. NG | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Extra curricular Activities | 17.85 (1.44, 221.06) | 13.56 (1.44, 127.59) | 1.60 (1.08, 2.38) | 1.52 (1.08, 2.12) | 2.83 (0.67, 11.95) | 1.55 (0.47, 5.13) |

| Substance Use | ||||||

| Smoking ever | 21.30 (3.30, 137.33) | 3.60 (0.68, 19.15) | 2.77 (1.91, 4.01) | 1.69 (1.23, 2.33) | 12.56 (2.07, 76.23) | 2.43 (0.45, 13.08) |

| Marijuana ever | 14.94 (2.26, 98.91) | 5.63 (0.96, 32.88) | 2.56 (1.75, 3.76) | 1.69 (1.21, 2.35) | 5.81 (0.99, 34.31) | 2.82 (0.51, 15.53) |

| Alcohol ever | 28.31 (3.67, 218.56) | 24.35 (3.60, 164.50) | 4.24 (2.46, 7.33) | 3.78 (2.43, 5.88) | 1.65 (0.41, 6.64) | 2.10 (0.58, 7.60) |

| Alcohol-past 30 days | -- | -- | 2.20 (1.32, 3.68) | 1.66 (1.07, 2.58) | 4.33 (0.29, 64.54) | 2.50 (0.21, 29.55) |

| Other drug use ever | -- | -- | 3.27 (1.67, 6.40) | 1.71 (0.91, 3.19) | -- | -- |

| Caffeine use | ||||||

| None | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 1–2 | 1.54 (0.17, 13.58) | 0.70 (0.14, 3.47) | 1.39 (0.89, 2.16) | 1.59 (1.10, 2.30) | 0.39 (0.08, 1.93) | 0.35 (0.09, 1.39) |

| 3 or more | 21.95 (1.19, 405.98) | 9.48 (0.75, 120.60) | 3.13 (1.86, 5.26) | 2.38 (1.51, 3.75) | 2.99 (0.25, 36.10) | 2.18 (0.20, 24.03) |

| Aggression | ||||||

| Serious fights | 11.48 (0.99, 132.61) | 1.50 (0.13, 17.25) | 4.48 (1.95, 10.31) | 1.85 (0.81, 4.19) | 2.49 (0.24, 25.90) | 1.13 (0.10, 12.34) |

| Carry weapon | 11.51 (1.74, 76.25) | 1.57 (0.26, 9.35) | 2.71 (1.68, 4.38) | 1.64 (1.04, 2.58) | 2.87 (0.48, 17.17) | 0.93 (0.16, 5.44) |

| Mood | ||||||

| Depressed | 1.18 (0.19, 7.57) | 1.79 (0.41, 7.86) | 3.24 (2.01, 5.21) | 1.77 (1.16, 2.69) | 0.50 (0.10, 2.46) | 0.91 (0.23, 3.70) |

| Weight | ||||||

| Normal | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Underweight | -- | 1.03 (0.19, 5.70) | 1.39 (0.77, 2.51) | 1.16 (0.70, 1.93) | -- | 0.80 (0.18, 3.59) |

| Overweight | 0.64 (0.08, 5.36) | 0.75 (0.12, 4.57) | 0.90 (0.56, 1.45) | 0.87 (0.58, 1.31) | 0.71 (0.11, 4.47) | 1.09 (0.23, 5.27) |

| Obese | 0.98 (0.03, 34.68) | 1.44 (0.06, 32.81) | 0.82 (0.40, 1.67) | 0.69 (0.37, 1.30) | 2.47 (0.20, 30.47) | 2.46 (0.22, 26.97) |

Note: NG=nongamblings, LRG=low-risk gambling, ARPG=at-risk/problem gambling. Model covariates include gender, grade, grade average, Hispanic ethnicity, and family structure. OR= odds ratio, CI=confidence interval. “no” was the reference group unless otherwise indicated.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the NIH (R01 DA019039, RL1 AA017539, UL1 DE19586, T32 MH014235, and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research/Common Fund), the Connecticut Mental Health Center, the Connecticut State Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, and a Center of Excellence in Gambling Research Award from the National Center for Responsible Gaming and its Institute for Research on Gambling Disorders.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report that they have no financial conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript. Dr. Potenza has received financial support or compensation for the following: Dr. Potenza has consulted for and advised Boehringer Ingelheim and Lundbeck; has consulted for and has financial interests in Somaxon; has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Veteran’s Administration, Mohegan Sun Casino, the National Center for Responsible Gaming and its affiliated Institute for Research on Gambling Disorders, and Forest Laboratories, Ortho-McNeil, Oy-Control/Biotie, Psyadon and Glaxo-SmithKline pharmaceuticals; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders or other health topics; has consulted for law offices and the federal public defender’s office in issues related to impulse control disorders; provides clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program; has performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; has guest-edited journal sections; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts. Dr. Hoff has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Veterans Administration Clinical Research and Development, the National Center for Responsible Gambling and its affiliated Institute for Research on Gambling Disorders, and the National Center for PTSD; has participated in surveys, mailings, or telephone consultations related to psychiatric illness, ethics in medical research, or other health topics; has performed grant reviews for the NIH and other agencies,; has guest edited journal sections; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events, and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts. The other authors have no financial disclosures. The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funding agencies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alegria AA, Petry NM, Hasin DS, Liu SM, Grant BF, Blanco C. Disordered gambling among racial and ethnic groups in the US: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. CNS spectrums. 2009;14:132–142. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Welte JW, Hoffman JH, Tidwell MC. Gambling, alcohol, and other substance use among youth in the United States. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2009;70:134–142. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DT, Stefanovics EA, Desai RA, Potenza MN. Differences in the associations between gambling problem severity and psychiatric disorders among Black and White adults: Findings from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The American Journal on Addictions. 2011a;20:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DT, Stefanovics EA, Desai RA, Potenza MN. Gambling problem severity and psychiatric disorder among Hispanic and white adults: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011b;45:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DT, Steinberg MA, Wu R, Potenza MN. Differences in characteristics of Asian American and white problem gamblers calling a gambling helpline. CNS spectrums. 2009;14:83–91. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RIF. Models of gambling and gambling addictions as perceptual filters. Journal of Gambling Behavior. 1987;3:224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Burge AN, Pietrzak RH, Petry NM. Pre/early adolescent onset of gambling and psychosocial problems in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2006;22:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DW. New York Times. 2011. Casinos and buses cater to Asian roots; pp. A25–A26. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu E, Woo K. Problem gambling in Chinese American adolescents: Characteristics and risk factors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2012:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of Pathological Gambling. Pathological Gambling: A Critical Review. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham-Williams RM, Hong S. A latent class analysis (LCA) of problem gambling among a sample of community-recruited gamblers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:939–947. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815947e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfabbro P, Thrupp L. The social determinants of youth gambling in South Australian adolescents. Journal of adolescence. 2003;26:313–330. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall L, Tse S, Kingi A. Cultural icons and marketing of gambling. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2009;7:84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Felsher JR, Derevensky JL, Gupta R. Parental influences and social modeling of youth lottery participation. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology. 2003;13:361–377. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S. A prevalence study of gambling and problem gambling in British adolescents. Addiction Research. 1999;7:509. [Google Scholar]

- Fong TW, Tsuang J. Asian-Americans, addictions, and barriers to treatment. Psychiatry. 2007;4:51–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest D, McHale IG. Gambling and problem gambling among young adolescents in Great Britain. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2011;28:607–622. doi: 10.1007/s10899-011-9277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Resko SM, Duan L. Correlates of gambling among youth in an inner-city emergency department. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:113–121. doi: 10.1037/a0013912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Derevensky J. Familial and social influences on juvenlie gambling behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies. 1997;13:179–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1024915231379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardoon KK, Gupta R, Derevensky J. Psychosocial variables associated with adolescent gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:170–179. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DF. Juvenile gambling in North America: an analysis of long term trends and future prospects. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2000;16:119–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1009476829902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Hwang I, LaBrie R, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Winters KC, Shaffer HJ. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. Acculturation and gambling in Asian Americans: When culture meets availability. International Gambling Studies. 2012;12:69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Cross J, Frank M, Welch M, White CM, Rubenstein G, Moseley K, Mark M. Gambling and pathological gambling among university students. Addictive behaviors. 1991;16:517–527. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90059-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J, Doll H, Hawton K, Dutton WH, Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Rogers RD. Internet gamblers: A latent class analysis of their behaviours and health experiences. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2010;26:387–399. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9188-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo JMY, Raylu N, Oei TPS. Gambling among the Chinese: A comprehensive review. Clinical psychology review. 2008;28:1152–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Maciejewski PK, Potenza MN. Psychiatric correlates of gambling in adolescents and young adults grouped by age at gambling onset. Archives of general psychiatry. 2004;61:1116–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molde H, Pallesen S, Bartone P, Hystad S, Johnsen BH. Prevalence and correlates of gambling among 16 to 19-year-old adolescents in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2009;50:55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2008.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S, Ohtsuka K. Youth gambling in Melbourne’s west: Changes between 1996 and 1998 for Anglo-European background and Asian background school-based youth. International Gambling Studies. 2001;1:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- National Opinion Research Center. Gambling impact and behavior study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago; Chicago, IL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, Wareham JD, Steinberg MA, Rugle L, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Desai RA. Correlates of at-risk/problem internet gambling in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:150–159. e153. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raylu N, Oei TP. Role of culture in gambling and problem gambling. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23:1087–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Desai RA, Smith AE, Cavallo DA, Liss TB, McFetridge A, Potenza MN, Krishnan-Sarin S. Impulsive sensation seeking, parental history of alcohol problems, and current alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents. Journal of addiction medicine. 2008;2:185–193. doi: 10.1097/adm.0b013e31818d8916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: a research synthesis. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1369–1376. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield RD. Gambling and correlates of gambling among Minnesota public school students. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2000;16:153–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1009428913972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield RD, Cassuto N, Winters KC, Latimer W. Prevalence of gambling among Minnesota public school students in 1992 and 1995. Journal of Gambling Studies. 1997;13:25–48. doi: 10.1023/a:1024987131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Local Update of Census Addresses (LUCA) Program user guide for tribal governments. U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, D.C: 2007. Option 1, Title 13 full address list review, paper address list format. [Google Scholar]

- Vachon J, Vitaro F, Wanner B, Tremblay RE. Adolescent gambling: Relatiojnships with parent gambling and parenting practices. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:398–401. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volberg RA, Gupta R, Griffiths MD, Olason D, Delfabbro PH. An international perspective on youths gambling prevalence studies. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2010;22:3–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte JW, Barnes GM, Tidwell MC, Hoffman JH. The prevalence of problem gambling among U.S. adolescents and young adults: Results from a national survey. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2008;24:119–133. doi: 10.1007/s10899-007-9086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal JR, Rush JA, Stevens L, Johnson LJ. Gambling behavior of Louisiana students in grades 6 through 12. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:96–99. doi: 10.1176/ps.51.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickwire EM, Whelan JP, Meyers AW, Murray DM. Environmental correlates of gambling behavior in urban adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:179–190. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Lai CF, Nagasawa R, Lin T. Asian Americans as a model minority: Self- perceptions and perceptions by other racial groups. Sociological Perspectives. 1998;41:95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yip SW, White M, Grilo C, Potenza M. An exploratory study of clinical measures associated with subsyndromal pathological gambling in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2011;27:257–270. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9207-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.