Abstract

Heterotaxy (Htx) is a disorder of left-right (LR) body patterning, or laterality, that is associated with major congenital heart disease1. The etiology and mechanism underlying most human Htx is poorly understood. In vertebrates, laterality is initiated at the embryonic left-right organizer (LRO), where motile cilia generate leftward flow that is detected by immotile sensory cilia, which transduce flow into downstream asymmetric signals2–6. The mechanism that specifies these two cilia types remains unknown. We now show that the GalNAc-type O-glycosylation enzyme GALNT11 is crucial to such determination. We previously identified GALNT11 as a candidate disease gene in a patient with Htx7, and now demonstrate, in Xenopus, that galnt11 activates Notch signaling. GALNT11 O-glycosylates NOTCH1 peptides in vitro, thereby supporting a mechanism of Notch activation either by increasing ADAM17-mediated ectodomain shedding of the Notch receptor or by modification of specific EGF repeats. We further developed a quantitative live imaging technique for Xenopus LRO cilia and show that galnt11-mediated notch1 signaling modulates the spatial distribution and ratio of motile and immotile cilia at the LRO. galnt11 or notch1 depletion increases the ratio of motile cilia at the expense of immotile cilia and produces a laterality defect reminiscent of loss of the ciliary sensor Pkd2. In contrast, Notch overexpression decreases this ratio mimicking the ciliopathy, primary ciliary dyskinesia. Together, our data demonstrate that Galnt11 modifies Notch, establishing an essential balance between motile and immotile cilia at the LRO to determine laterality and identifies a novel mechanism for human Htx.

Keywords: live imaging, Xenopus tropicalis, left-right patterning, O-glycosylation, congenital heart disease, motility, mechanosensation, primary cilium, mouse node, gastrocoel roof plate, GalNAcT11

Recent, genomic analyses have identified candidate genes for congenital heart disease7–9; however, determining disease causality and developmental mechanisms remains challenging. In a Htx patient, we identified a copy number deletion of the GALNT11 gene7, a polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (GALNT) that controls the initiation of GalNAc-type O-glycosylation10. GALNTs serve different functions; however, a role for GALNT11 in vertebrate development is unknown.

To investigate the role of GALNT11 in LR development, we first examined its effects on cardiac looping. Normally, in vertebrates, the initially midline heart tube forms a rightward (D) loop. Aberrant LR patterning results in abnormal cardiac loops, including leftward (L) and symmetric/midline (A) loops. In Xenopus, we first confirmed that galnt11 knockdown (KD) by morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) led to abnormal cardiac looping, and that overexpression of human GALNT11 mRNA could rescue this phenotype, demonstrating specificity (Fig 1a).

Figure 1. Galnt11 alters LR patterning and Notch signaling.

Percent of embryos that have abnormal (a) cardiac looping (either A loops or L loops) or (b) abnormal coco or pitx2c expression L: left, R: right. c–j) Xenopus epidermal multiciliated cells marked by anti-acetylated α-tubulin (red). Embryos were injected at the two cell stage targeting the epidermis on either the right or left side with either galnt11 MO (d), GALNT11 RNA (f), notch1 MO (h), or nicd RNA (j) and compared to the uninjected side (c, e, g, i). GFP (insets) trace the injected side. All views are lateral views with dorsal to the top. k) Schematic of the Notch pathway l) Percent of embryos with abnormal pitx2c in galnt11 morphants or galnt11 morphants co-injected with members of the Notch pathway. Panel (a) UC n=130, galnt11 start MO n=145, galnt11 splice MO n=105, galnt11 splice MO + galnt11 RNA n=83, galnt11 RNA n=96. Panel (b) coco expression UC n=21, galnt11 MO n=24, galnt11 RNA n=23; pitx2c expression UC n=45, galnt11 MO n=54, galnt11 RNA n=34. Panel (l) UC n=96, galnt11 MO n=78, galnt11 MO + delta n=65, galnt11 MO + nicd n=86, galnt11 MO + su(h)ank n=62. Bars depict means. Additional details are in Methods.

We then examined early markers of LR patterning, dand5 (coco, cerl2) and pitx2c. coco is the earliest known asymmetric marker11. At the LRO, coco expression is initially symmetric but develops a right-sided bias with the onset of cilia-driven flow, while pitx2c is expressed in the left lateral plate mesoderm11. Both galnt11 KD and GALNT11 GOF resulted in abnormal patterns of coco and pitx2c, indicating that galnt11 affects LR patterning upstream of coco at the ciliated LRO (Fig 1b). Consistent with this finding, we previously found galnt11 mRNA expressed at the LRO7, and Galnt11 protein is localized in the mouse LRO (node), with enrichment in crown cells compared to pit cells (Ext Fig 1).

Abnormal coco expression suggests an abnormality in cilia-dependent signaling at the LRO. We first searched for a ciliary ultrastructural defect in the multiciliated cells on the Xenopus epidermis but found no consistent defect (Ext Fig 2). However, we did observe a higher density of multiciliated cells (compare Fig 1c and 1d). Conversely, galnt11 GOF reduced the number of multiciliated cells (Fig 1e, 1f). Interestingly, a similar phenotype is seen with disruptions in Notch signaling12. Like galnt11, notch1 KD increases, while notch1 GOF (nicd) decreases, the multiciliated cell density (Fig 1g–j). Based on these results, we hypothesized that galnt11 may affect the Notch signaling pathway.

We further explored this possibility by examining the effects of galnt11 and notch1 on the LR developmental cascade. galnt11 and notch1 KD and GOF produced similar LR patterning defects (Ext Fig 3), suggesting that galnt11 affects Notch signaling directly or in a parallel pathway. Notch is a key regulator of many aspects of biology13. The core components of the Notch pathway include a ligand, Delta or Jagged, the transmembrane Notch receptor, and the CBF1/Su(H)/Lag-1 (CSL) transcription factor complex (Fig 1k). Signaling from the Notch receptor requires a number of cleavage steps, S1–S3, culminating in the release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which translocates to the nucleus, interacts with CSL, and modulates Notch responsive genes (Fig 1k).

To test if Galnt11 acts directly in the Notch pathway, we attempted to rescue the galnt11 KD phenotype with Notch pathway members. Using pitx2c as our assay, we found that delta GOF had little effect on galnt11 KD, but both nicd and su(h)-ank (a constitutively active CSL protein14) efficiently rescued the phenotype (Fig 1l).

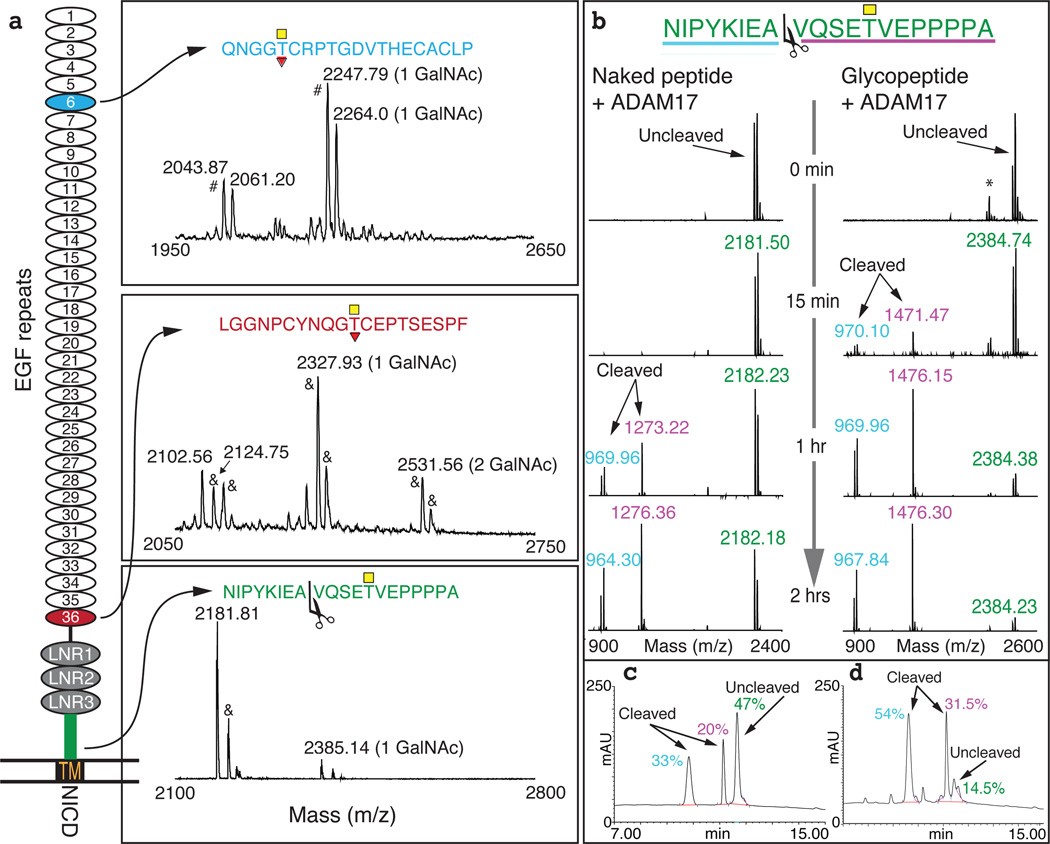

Notch functions are regulated by different O-glycosylations in the EGF repeats of the Notch receptor that affect the ligand-receptor interaction15. However, GalNAc-type O-glycosylation has not been reported previously; given our results, we searched for GalNAc-type O-glycosylation of Notch to identify activation mechanisms. First, we confirmed that Xenopus and human GALNT11 have identical substrate specificity similar to the Drosophila ortholog (Ext Table 1)16. Using mass spectrometry, we then tested 38 peptides derived from the extracellular domain (ECD) of human NOTCH1 in an in vitro enzyme assay to identify potential substrate sites for GALNT11 O-glycosylation. Three peptides were glycosylated by GALNT11, two in EGF repeats 6 and 36 overlapping proposed O-fucosylation sites15 and one in the juxtamembrane region near the ADAM metalloproteinase ectodomain shedding site (Fig 2a)17. The identified peptide substrates and several others were also glycosylated by other GALNTs (Ext Fig 4).

Figure 2. GALNT11 glycosylation of NOTCH1 derived peptides and effects on ADAM-mediated cleavage.

a) Depiction of NOTCH1 with MALDI-TOF spectra demonstrating O-GalNAc glycosylation of peptides derived from EGF6 (blue), EGF36 (magenta) and the juxtamembrane region (green). Yellow squares: O-GalNAc, Red triangles: O-Fuc. TM: transmembrane domain; NICD: Notch intracellular domain; # deammoniated peptide; & sodium adducts. b) MALDI-TOF time-course analysis of in vitro cleavage of the juxtamembrane peptide and glycopeptide by ADAM17. Scissors: Cleavage site. *nonspecific N-terminal degradation of two amino acids. c–d) HPLC analysis of the cleavage reactions with c) naked peptide and d) glycopeptide after 2 hrs (percentages above the peaks) with p<0.05 (two-tailed t-test).

Our experiments in Xenopus indicate that galnt11 activates the Notch pathway (Fig 1 and Ext Fig 3). However, the identified O-glycosylation site adjacent to the ADAM processing site (Fig 2a) would be expected to inhibit cleavage (based on numerous previous examples e.g. in TNR16, Ext Fig 5a)18 and thus block Notch receptor activation (Fig 1k). Surprisingly, but in support of our original hypothesis, GALNT11 O-glycosylation enhanced cleavage of the juxtamembrane peptide by ADAM 17 (Fig. 2b–d, Ext Fig 5b). We thus propose a model where site-specific GALNT11 glycosylation of NOTCH1 adjacent to the ADAM cleavage site facilitates shedding and activates the pathway by increasing the amount of NICD. However, alternative models remain possible with the identified glycosylation of ECD peptides, and additional in vivo studies are needed. Notably, the catalytic function of GALNT11 is required for mediating LR development, since mutation of essential catalytic residues from DSH to DSA (H247A)10 eliminates the aberrant effects on pitx2c and LR looping seen with wildtype GALNT11 GOF (Ext Fig 5c,d).

Next, we focused on how Galnt11 modulation of Notch1 alters LR development, where Notch has several possible roles19. Our data indicate that galnt11 acts upstream of asymmetric coco expression, so we focused our attention on the potential relationship between galnt11 and cilia function in the LRO.

galnt11 morphants retained bilateral symmetry: a predominance of midline, cardiac A loops and symmetric coco and pitx2 expression (Fig1 and Ext Fig 3). Similarly, our patient with GALNT11 haploinsufficiency had bilateral symmetry, presenting with right atrial isomerism7. Finally, mutant Dll1 or Notch1/2 mice and des/notch1a zebrafish are also predominately symmetric20,21. This is reminiscent of the Pkd2 mutant mice phenotype, which has right isomerism due to failure of ciliary sensing4,22. In contrast, overexpression of GALNT11 in Xenopus led to L and D loops (Fig 1a), and randomization across the LR axis, mimicking the human disorder primary ciliary dyskinesia, where ineffective ciliary beating fails to generate extracellular fluid flow. Based on these two observations, we postulated that GALNT11 via Notch specifies immotile (sensory) versus motile cilia (Ext Fig 8).

To test this, we developed a live imaging method to simultaneously assay motile and immotile cilia in the LRO of Xenopus, the gastrocoel roof plate (GRP). Employing an epitope-tagged ciliary protein, Arl13b-mCherry23 with confocal microscopy (Fig 3a, Sup Video 1), we spatially mapped motile and immotile cilia. After additive analysis of numerous LROs, we qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed cell populations with either cilia type (Ext Fig 6a–d). In wildtype Xenopus LRO explants, we found that motile cilia are concentrated in the center, with relatively more immotile cilia at the periphery, similar to the mouse LRO (or node) pit and crown, respectively (Fig 3b, c, h [vehicle])3,4. In both locations, cilia types are intermixed similar to the mouse LRO.

Figure 3. Galnt11/Notch signaling switches cilia between motile and immotile types.

a) Wildtype LRO explants expressing arl13b-mCherry reveal distinct populations of immotile and motile cilia. Cyan box highlights a single motile cilium, with a corresponding kymograph analyzing beating frequency. Magenta box highlights immotile cilium and kymograph. b) Analysis of multiple vehicle LROs reveals a specific geography for cilia types: immotile cilia are enriched along the fringes, while motile cilia are enriched in the center. c) Schematic of a wildtype LRO A: anterior, P: posterior, L: left, R: right. d) nicd overexpressants exhibit a decrease in motile cilia in the center of the LRO. notch1 (e) and galnt11 (f) morphants display a decrease in immotile cilia along the LRO periphery. (g–h) Quantification of motile cilia distribution in total LROs (g), and in the center and along the periphery of the LRO (h). Bars depict means and error bars are standard error. b,d,e,f) n=8. g,h) vehicle n=17, nicd RNA n=12, notch1 MO n=12, galnt11 MO n=15. Additional details are in Methods.

To evaluate the role of notch1 signaling, we co-injected nicd and arl13b-mCherry and analyzed cilia types. nicd overexpression reduced the ratio of motile to immotile cilia when compared to controls (compare Fig 3d to b, 3g and Sup Video 2). KD of notch1 or galnt11 had the opposite effect, increasing the ratio of motile to immotile cilia (Fig 3e–g and Sup Video 3,4). Previous reports have identified asymmetric RNA expression of Notch ligands at the LRO24; however, we failed to observe any significant asymmetry in cilia number or type across the LR axis of the LRO (Ext Fig 6j,k).

The transcription factors, FoxJ1 and Rfx2 are regulators of motile ciliogenesis25–27 so we evaluated the expression of rfx2 and foxj1 at the Xenopus LRO in response to Notch activation. nicd or GALNT11 GOF reduced the expression of foxj1 and rfx2, while H247A GALNT11 GOF had no effect (Ext Fig 7a–h), suggesting that Notch signaling functions upstream of foxj1 and rfx2 in determining ciliary type at the LRO.

Since Galnt11 expression in the mouse node was most prominent in the lateral crown cells (Ext Fig 1), we compared the Xenopus LRO periphery with the center (Ext Fig 6a–h). Interestingly, cilia in the periphery, where they are predominantly immotile (Fig 3b, c), were strikingly transformed to the motile type with galnt11 and notch1 KD (Fig 3h). Overall, mean total cilia numbers per LRO were not statistically different, supporting altered cilia identity as the primary mechanism for LR defects (Ext Fig 6i). To confirm that galnt11 was not perturbing formation of the LRO periphery, we tested peripheral markers at stages prior to when flow alters coco and noted no significant differences (Ext Fig 7i–u). We conclude that Galnt11/Notch1 signaling mediates a critical switch between these two cilia types and their spatial distribution within the LRO (Ext Fig 8).

Our results strengthen the two cilia model of LR patterning by identifying a signaling pathway that modulates the balance between motile and immotile cilia3 at the LRO (Ext Fig 8). Exactly how many cilia and which types are needed for proper LR signaling is controversial and may depend on the specific architecture of the LRO found in each organism. For example, in the mouse LRO, a partially open cup-shaped structure, only two motile cilia are needed for LR patterning28. However, in the zebrafish LRO, which is an enclosed spherical structure, there appears to be a greater enrichment of motile cilia relative to frog or mouse29. In the frog LRO, which is a shallow indentation inside the gastrocoel cavity, motile cilia are required only on the left for correct LR patterning30. For immotile cilia, there may be a threshold number that also differs depending on the specific architecture of the organism’s LRO. Further studies will need to address why two cilia types are needed in the LRO and the mechanisms that convert ciliary sensation of flow to asymmetric gene expression and laterality.

Our findings were prompted by gene discovery in a single disease subject. We had no additional alleles to prove causality using a genetic approach7. Instead, we assayed for phenocopy in a high-throughput vertebrate model, Xenopus, and then embarked on mechanistic analyses in order to understand the role GALNT11 plays in LR patterning and disease. Our results have led to new insights into the basic biology of GalNAc-type O-glycosylation, Notch signaling, LR patterning, and the etiology of Htx. Because of high locus heterogeneity and severe reduction in fitness, causative gene discovery in children with birth defects has been challenging. However, with the brisk pace of advancing human genomics, these limitations are being broken, and new opportunities are at hand to understand birth defects and their underlying genetic mechanisms especially when coupled with rapid vertebrate developmental models such as Xenopus.

Methods

Frog Husbandry

X. tropicalis were housed and cared for in our aquatics facility according to established protocols that were approved by Yale IACUC.

Mouse Husbandry

Mice were housed and cared for in our animal facility according to established protocols that were approved by Yale IACUC.

Microinjection of MOs and mRNA in Xenopus

We induced ovulation and collected eggs according to established protocols31. Staging of Xenopus tadpoles were according to Nieuwkoop and Faber32. MOs or mRNA were injected into the one cell or two cell embryo as previously described33. The following morpholino oligos were injected: galnt11 splice blocking (0.5–1 ng 5’CAGGTCAGAGAGAAGGGCACCTACT), galnt11 ATG blocking (0.5–1 ng 5’GCGCTGCCCATCGTCCCCCTAGCA), notch1 (3 ng 5’GAACAAGCAGCCCGATCCGATACAT), dnah9 (2–4 ng 5’TGGGTCACTCATCTTTCCCCTCATT). Alexa488 (Invitrogen), mini-ruby (Invitrogen), or GFP (100pg) were injected as tracers. We generated in vitro capped mRNA using mMessage machine kit (Ambion) and followed the manufacturer’s instructions. We generated human GALNT11 mRNA by cloning the insert from IMAGE clone 100068224 into the pCSDest vector using Gateway recombination techniques. To generate arl13b-mCherry mRNA, we fused zebrafish arl13b to mCherry into the pCSDest2 vector using Gateway recombination techniques. We injected 6 pg of GALNT11 mRNA for rescue of galnt11 morphants, 25 pg of GALNT11 mRNA for overexpression to assay LR patterning and in the ciliated epidermis assay, 25 pg GALNT11 H247A, 12.5 pg of nicd mRNA for rescue of galnt11 morphants, 25 pg of nicd mRNA for overexpression to assay LR patterning and in the ciliated epidermis assay, 2 pg of su(h)ank, and 100–200 pg of arl13b-mCherry.

Cardiac looping in Xenopus

Frog embryos at stage 45 were treated with benzocaine and ventrally scored for cardiac looping using a light dissection microscope. Loop direction is defined by the position of the outflow tract relative to the inflow of the heart: outflow to the right – D loop; outflow to the left – L loop; outflow midline – A loop.

Transfection of IMCD3 cells

Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA 48 hours after transfection and processed for immunofluorescence. Cells were not authenticated nor tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Immunofluorescence (IF) and in situ hybridization

E8.0 mouse embryos were harvested from timed pregnancies for node IF. Observation of coital plug marks e0.5. For GRPs, we collected stage (st) 14 Xenopus embryos for foxj1 and rfx2, st 16 for coco, xnr1, and gdf3, and st. 19–21 for coco. For pitx2c, we collected Xenopus embryos at st 28–31. For IF of multiciliated epidermal cells, we used st. 28–30 Xenopus embryos. GRPs were dissected as previously described5.

For IF, transfected mammalian cells, mouse and Xenopus embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS overnight at 4°Mouse embryos, Xenopus embryos, and Xenopus GRPs were labeled by immunofluorescence as previously described3,33. All embryos were mounted in Pro-Long Gold (Invitrogen) prior to imaging. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss Axiovert microscope equipped with Apotome optical interference imaging to obtain optical sections. For comparison of left- and right-sided epithelial cilia density, the Xenopus embryos were sandwiched between two coverslips and each side of a single embryo was imaged.

RNA in-situ hybridization was done as previously described33. We detected coco34, gdf3, foxj1, pitx2c, rfx2, and xnr1 by generating anti-digoxigenin probes (Roche) using clones TEgg007d24, Tgas141F11, TNeu058M03, TNeu083k20, IMAGE:7680423, and TGas124h10 respectively.

Antibodies used

Anti-Arl13b35

Rabbit anti-Arl13b (1:500, courtesy of T. Caspary)

Anti-acetylated tubulin (Sigma, Catalog: T-6793)36

Mouse monoclonal anti-acetylated tubulin, clone 6-11B-1 (1:1000)

Species reactivity: monkey, Protista, mouse, pig, human, bovine, invertebrates, rat, hamster, plant, frog, chicken

Anti-GALNT11 (Santa Cruz, Catalog: sc-68498)

Goat polyclonal anti-GALNT11 (K-19) (1:200) (transfected cells)

Species reactivity: mouse, rat, human

Anti-GALNT1137

Mouse, polyclonal (undiluted) (mouse LRO)

Live imaging of cilia motility in the GRP

For imaging of cilia motility in the GRP, wildtype embryos were injected with arl13b-mCherry mRNA at the 1-cell stage and then cultured until stage 16 – 17. Vehicle embryos were co-injected with water, while nicd overexpressants, notch1 morphants, and galnt11 morphants were co-injected with RNA or MOs. GRP explants were prepared in MBSH and mounted on a coverglass within a ring of petroleum jelly. High-speed fluorescent imaging was performed on an LSM 710 DUO (Zeiss) microscope equipped with a rapid LIVE linescan detector, a 40× C-Apochromat water objective and a 561-nm laserline. Multiple rapid acquisitions were collected per each embryo at several Z-planes within the GRP. All acquisitions were collected at a rate of 240 frames per second (fps) with a 512 × 512 pixel resolution using maximal pinhole settings, bidirectional scanning and 0 binning in Zen 2010 (Zeiss). Cilia beating dynamics were analyzed and quantified by kymographs in ImageJ (NIH) with an elapsed time of 1s displayed in Fig 3. Movie clips with overlays were prepared using Final Cut (Apple) and Compressor (Apple).

Spatial analysis of motile and immotile cilia populations in the GRP

Live high-speed acquisitions of GRP explants expressing arl13b-mCherry were slowed down, played back, and scored for motile and immotile cilia in ImageJ (NIH) onto two overlaying images: one for motile and the second for immotile cilia (Ext Fig 6a–c). Each overlaying image was converted into a binary image and then converted a second time into a false-colored 8-bit image. Both images were then merged to generate a two-color map of cilia distribution for an individual GRP (Ext Fig 6d). For each experimental condition, numerous two-color maps were assembled into an image series and processed into a single composite image using the projection function in ImageJ (Fig 3b, d, e, f). For quantification of motile and immotile cilia in the periphery or center region of the LRO, a two-color map representing a single GRP was imported into Photoshop CS5 (Adobe). A new layer (named ‘Layer 1’) was created and the edge of the total ciliated population of that GRP was traced using the pencil tool (Ext Fig 6e). A duplicate of the trace layer was created (named ‘Layer 2’), decreased in area uniformly (to maintain the shape of the original trace) by 50% using the transform tool and aligned at the absolute center of Layer 1 (Ext Fig 6f). By dividing the LRO into two 50% areas, while maintaining the specific shape of each GRP, the periphery and center of the LRO were defined with equal areas; thus minimizing any potential pre-conceived size bias for either zone (Ext Fig 6g, h). Further, this estimate is broadly supported by studies of the crown and pit cells in the mouse LRO4. The area within the trace in Layer 2 was defined as the center of the LRO, while the area between the traces in Layers 1 and 2 was defined as the periphery. Motile, immotile cilia, and total cilia (Fig 3, Ext Fig 6i) were scored specifically in the center and then periphery area.

In vitro GALNT11 glycosylation and ADAM processing studies

Glycosylation assays were performed in 25 µL reaction mixtures containing 10 µg peptide substrate, 4 mM UDP-GalNAc, 25 mM cacodylic acid sodium (pH 7.4), 10 mM MnCl2, 0.25% Triton X-100, and purified recombinant GALNT enzymes (0.1 µg). The enzyme reactions in Fig 2a were performed with GALNT11 by in vitro assays for 18–24 hrs. ADAM cleavage assays were performed with 250 nM ADAM17 (Enzo Life Sciences) with 10 µg of peptide or GalNAc-glycopeptide substrate in 25 mM TRIS (pH 9) in a total volume of 25 µl. Reaction for ADAM cleavage assays were sampled at 0 hrs, 15 min, 1 hrs, and 2 hrs. All reactions were incubated at 37°C and product development evaluated by MALDI-TOF in a time-course as previously described37 except that a Bruker Autoflex MALDI-TOF instrument with accompanying Compass 1.4 FlexSeries software was used for product evaluation. Position of sites were determined by electrospray ionization-linear ion trap-Fourier transform mass spectrometry (ESI-LIT-FT-MS) applying both high energy collision-induced dissociation and electron transfer dissociation (ETD) enabling peptide sequence analysis by MS/MS (MS2) with retention of glycan site-specific fragments as described in detail previously38 (data not shown). HPLC analyses were performed using a multistep gradient on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 LC system (Thermo Scientific) with a Kinetex 2.6u C18 100A 100×4.60 mm column (Phenomenex). Areas under the curves were calculated using the Chromeleon 6.80 software. Statistical analysis (two-tailed T-test) was carried out in Microsoft Excel comparing the averages of full-length glycosylated and unglycosylated peptides from three different sets of cleavage experiments. Statistical analysis showed that the difference in cleavage efficiency between the unglycosylated and glycosylated peptides was significant (p<0.05) in Fig 2c.

Electron microscopy

Stage 27 Xenopus embryos were fixed with Karnovsky fixative for 1 h at 4°C, washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4, then post-fixed with Palade's osmium for 1 h at 4°C, shielded from light. Following a second wash, embryos were stained with Kellenburger's solution for 1 h at RT, washed in double distilled water, then put through an ethanol series, propylene oxide, 50/50 propylene oxide/epon, then two incubations in 100% epon. Embedded embryos were sectioned at 400 nm before staining with 2% uranyl acetate. Micrographs were taken on a Zeiss 910 electron microscope.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated that for Xenopus experiments 20–25 samples per experimental condition were necessary for statistical significance given the magnitude of the changes expected. In most cases, considerably more samples were obtained for each except as noted in the figures. Statistical significance is reported as appropriate. In no cases did we exclude samples except in cases of technical failure (embryos were found to be uninjected, in situ hybridization failed, etc). We did not use any randomization method. For pitx2 and coco expression, one observer was unblinded but in all cases at least 1–2 other observers were blinded and a high degree of concordance was noted.

For Fig 1a sample sizes were 130 for uninjected controls, 145 for Galnt11 start MO, 105 for Galnt11 splice MO, 83 for Galnt11 splice MO + Galnt11 RNA, and 96 for Galnt11 RNA. These numbers represent the cumulative total of three biological replicates. For Fig 1b coco expression patterns sample sizes were 21 for uninjected controls, 21 for Galnt11 splice MO, and 23 for Galnt11 RNA. For pitx2c expression patterns sample sizes were 45 for uninjected controls, 54 for Galnt11 splice MO, and 34 for Galnt11 RNA. These numbers represent the cumulative total of two biological replicates for coco and three for pitx2 expression patterns. For Fig 1l sample sizes were 96 for uninjected controls, 78 for Galnt11 MO, 65 for Galnt11 MO + delta, 86 for Galnt11 MO + nicd, and 62 for Galnt11 MO + Su(h)ank. These numbers represent the cumulative total of three biological replicates.

For Fig 2, enzyme reactions were repeated three times, and statistical analysis on HPLC data was done using three biological replicates.

For the entirety of Fig 3, the data shown represent a cumulative total of 15 biological replicates. Fig 3a is a representative image. For Fig 3b,d,e,f, the analyzed samples sizes were 8 embryos per each condition. For Fig 3g,h, analyzed sample sizes were 17 embryos for vehicle (dH20), 12 for nicd RNA, 12 for notch1 MO and 15 for galnt11 MO. For Fig 3g,h, statistical significance was analyzed by t-test (two-tailed, type two); center values represent averages; errors bars indicate standard error. For quantitative analysis and mapping, embryos were excluded on the following pre-established criteria: 1) only partial labeling of total cilia population in the GRP by Arl13b-mCherry; 2) improper embryonic stage (stages 16/17 were defined as the inclusion criteria).

For Ext Fig 3 coco expression patterns sample sizes were 21 for uninjected control, 24 for galnt11 MO, 30 for notch MO, 23 for galnt11 RNA, and 22 for nicd RNA. These numbers represent the cumulative total of two biological replicates. For pitx2c expression patterns, sample sizes were 45 for uninjected control, 54 for galnt11 MO, 50 for notch MO, 34 for galnt11 RNA, and 30 for nicd RNA. These numbers represent the cumulative total of three biological replicates. For heart looping sample sizes were 276 for uninjected control, 68 for galnt11 MO, 75 for notch MO, 91 for galnt11 RNA, and 50 for nicd RNA.

For Ext Fig 4 glycosylations reactions were all repeated a minimum of two times for each glycosylation enzyme.

For Ext Fig 5, panel a) is a representative spectrum of three independent experiments, and b) is a representative spectrum of two independent experiments. For panel c) pitx2c expression patterns sample sizes were 45 for uninjected control, 34 for galnt11 RNA and 40 for galnt11 H247A RNA. These numbers represent the cumulative total of two biological replicates. For heart looping sample sizes were 276 for uninjected control, 91 for galnt11 RNA and 133 for galnt11 H247A RNA. These numbers represent the cumulative total of 3 biological replicates.

For the entirety of Ext Fig 6, the data shown represent a cumulative total of 15 biological replicates. Ext Fig 6a–h are representative images. For Ext Fig 6i, analyzed sample sizes were 17 embryos for vehicle (dH20), 12 for nicd RNA, 12 for notch1 MO and 15 for galnt11 MO. For Ext Fig 6j,k, analyzed sample sizes were 17 vehicle ('wildtype') embryos. For Ext Fig 6i,j,k, statistical significance was analyzed by t-test (two-tailed, type two); center values represent averages; errors bars indicate standard error. For quantitative analysis and mapping, embryos were excluded on the following pre-established criteria: 1) only partial labeling of total cilia population in the GRP by Arl13b-mCherry; 2) improper embryonic stage (stages 16/17 were defined as the inclusion criteria).

In all figures, statistical significance was defined as P<0.05, while P≥0.05 was defined as not significant (NS). A single asterisk indicates P<0.05, while double and triple asterisks indicates P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively. Fig 3 and Ext Fig 6 were analyzed by t-test (two-tailed, type two) presuming a normal distribution. Fig 1, Ext Fig 3, Ext Fig 5 were analyzed by chi-square as previously described39.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families who are the inspiration for this study. We thank S. Kubek and M. Slocum for animal husbandry. We thank U. Mandel, M. Vester-Christensen, T. D. Madsen, and S. B. Levery for help with generation of polyclonal antibodies, recombinant GALNT enzymes, in vitro glycosylation experiments, and mass spectrometry. Thanks to the Center for Cellular and Molecular Imaging at Yale for assistance with SEM/TEM (C. Rahner and M. Graham) and confocal imaging. Thanks to C. Kintner and Z. Sun for reagents. Thanks to R. Harland, K. Liem, R. Lifton, J. McGrath, A. Horwich and Z. Sun for critical reading of the manuscript. MTB was supported by Grant Number TL 1 RR024137 from NCRR/NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. SY was supported by NIH training grant 5T32HD00709436. This work was supported by NIH R01HL093280 to MB and NIH DE018825, DE018824 to MKK, and the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF107) to HC.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

MTB, SY, SM, MB, and MKK conceived and designed the embryological experiments in Xenopus and mouse. MTB, SY, SM, and MKK performed the Xenopus experiments while MB performed mouse experiments. NBP, CKG and HC performed and evaluated the glycosylation and ADAM studies. All authors wrote and contributed to the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Sutherland MJ, Ware SM. Disorders of left-right asymmetry: heterotaxy and situs inversus. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2009;151C:307–317. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nonaka S, et al. Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell. 1998;95:829–837. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81705-5. [published erratum appears in Cell 1999 Oct 1;99(1):117] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath J, Somlo S, Makova S, Tian X, Brueckner M. Two populations of node monocilia initiate left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshiba S, et al. Cilia at the node of mouse embryos sense fluid flow for left-right determination via Pkd2. Science. 2012;338:226–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1222538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweickert A, et al. Cilia-driven leftward flow determines laterality in Xenopus. Curr Biol. 2007;17:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer-Zucker AG, et al. Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer's vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development. 2005;132:1907–1921. doi: 10.1242/dev.01772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakhro KA, et al. Rare copy number variations in congenital heart disease patients identify unique genes in left-right patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2915–2920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenway SC, et al. De novo copy number variants identify new genes and loci in isolated sporadic tetralogy of Fallot. Nat Genet. 2009;41:931–935. doi: 10.1038/ng.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaidi S, et al. De novo mutations in histone-modifying genes in congenital heart disease. Nature. 2013;498:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett EP, et al. Control of mucin-type O-glycosylation: a classification of the polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family. Glycobiology. 2012;22:736–756. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweickert A, et al. The nodal inhibitor Coco is a critical target of leftward flow in Xenopus. Curr Biol. 2010;20:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deblandre GA, Wettstein DA, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Kintner C. A two-step mechanism generates the spacing pattern of the ciliated cells in the skin of Xenopus embryos. Development. 1999;126:4715–4728. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Muskavitch MA. Notch: the past, the present, and the future. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:1–29. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wettstein DA, Turner DL, Kintner C. The Xenopus homolog of Drosophila Suppressor of Hairless mediates Notch signaling during primary neurogenesis. Development. 1997;124:693–702. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rana NA, Haltiwanger RS. Fringe benefits: functional and structural impacts of O-glycosylation on the extracellular domain of Notch receptors. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwientek T, et al. Functional conservation of subfamilies of putative UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases in Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, and mammals. One subfamily composed of l(2)35Aa is essential in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22623–22638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brou C, et al. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell. 2000;5:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gram Schjoldager KT, et al. A systematic study of site-specific GalNAc-type O-glycosylation modulating proprotein convertase processing. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40122–40132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato Y. The multiple roles of Notch signaling during left-right patterning. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0695-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes SS, et al. Notch signalling regulates left-right asymmetry through ciliary length control. Development. 2010;137:3625–3632. doi: 10.1242/dev.054452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krebs LT, et al. Notch signaling regulates left-right asymmetry determination by inducing Nodal expression. Genes Dev. 2003 doi: 10.1101/gad.1084703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennekamp P, et al. The ion channel polycystin-2 is required for left-right axis determination in mice. Curr Biol. 2002;12:938–943. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00869-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duldulao NA, Lee S, Sun Z. Cilia localization is essential for in vivo functions of the Joubert syndrome protein Arl13b/Scorpion. Development. 2009;136:4033–4042. doi: 10.1242/dev.036350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raya A, et al. Notch activity acts as a sensor for extracellular calcium during vertebrate left-right determination. Nature. 2004;427:121–128. doi: 10.1038/nature02190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stubbs JL, Oishi I, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Kintner C. The forkhead protein Foxj1 specifies node-like cilia in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1454–1460. doi: 10.1038/ng.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisgrove BW, Makova S, Yost HJ, Brueckner M. RFX2 is essential in the ciliated organ of asymmetry and an RFX2 transgene identifies a population of ciliated cells sufficient for fluid flow. Dev Biol. 2012;363:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung MI, et al. RFX2 is broadly required for ciliogenesis during vertebrate development. Dev Biol. 2012;363:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shinohara K, et al. Two rotating cilia in the node cavity are sufficient to break left-right symmetry in the mouse embryo. Nature communications. 2012;3:622. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamura K, et al. Pkd1l1 complexes with Pkd2 on motile cilia and functions to establish the left-right axis. Development. 2011;138:1121–1129. doi: 10.1242/dev.058271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vick P, et al. Flow on the right side of the gastrocoel roof plate is dispensable for symmetry breakage in the frog Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2009;331:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods References

- 31.del Viso F, Khokha M. Generating diploid embryos from Xenopus tropicalis. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;917:33–41. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-992-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin) : a systematical and chronological survey of the development from the fertilized egg till the end of metamorphosis. Garland Pub.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khokha MK, et al. Techniques and probes for the study of Xenopus tropicalis development. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:499–510. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vonica A, Brivanlou AH. The left-right axis is regulated by the interplay of Coco, Xnr1 and derriere in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 2007;303:281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caspary T, Larkins CE, Anderson KV. The graded response to Sonic Hedgehog depends on cilia architecture. Dev Cell. 2007;12:767–778. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piperno G, Fulller MT. Monoclonal antibodies specific for an acetylated form of alpha-tubulin recognize the antigen in cilia and flagella from a variety of organisms. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2085–2094. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwientek T, et al. Functional conservation of subfamilies of putative UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases in Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, and mammals. One subfamily composed of l(2)35Aa is essential in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22623–22638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersen JW, et al. Lectin domains of polypeptide GalNAc transferases exhibit glycopeptide binding specificity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32684–32696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walentek P, Beyer T, Thumberger T, Schweickert A, Blum M. ATP4a is required for Wnt-dependent Foxj1 expression and leftward flow in Xenopus left-right development. Cell reports. 2012;1:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steentoft C, et al. Mining the O-glycoproteome using zinc-finger nuclease-glycoengineered SimpleCell lines. Nat Methods. 2011;8:977–982. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steentoft C, et al. Precision mapping of the human O-GalNAc glycoproteome through SimpleCell technology. Embo J. 2013;32:1478–88. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.