Abstract

Relationships between parental broader autism phenotype (BAP) scores, gender, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment, serotonin (5HT) levels and the child's symptoms were investigated in a family study of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The Broader Autism Phenotype Questionnaire (BAPQ) was used to measure the BAP of 275 parents. Fathers not taking SSRIs (F-SSRI; N = 115) scored significantly higher on BAP Total and Aloof subscales compared to mothers not receiving treatment (M-SSRI; N = 136.) However, mothers taking SSRIs (M+SSRI; N = 19) scored higher than those not taking medication on BAP Total and Rigid subscales, and they were more likely to be BAPQ Total, Aloof and Rigid positive. Significant correlations were noted between proband autism symptoms and parental BAPQ scores such that Total, Aloof and Rigid subscale scores of F-SSRI correlated with proband restricted repetitive behavior (RRB) measures on the ADOS, CRI and RBS-R. However, only the Aloof subscale score of M+SSRI correlated with proband RRB on the ADOS. The correlation between the BAPQ scores of mothers taking SSRIs and child scores, as well as the increase in BAPQ scores of this group of mothers requires careful interpretation and further study because correlations would not withstand multiple corrections. As expected by previous research, significant parent-child correlations were observed for 5HT levels. However 5HT levels were not correlated with behavioral measures. Study results suggest that the expression of the BAP varies not only across parental gender, but also across individuals using psychotropic medication and those who do not.

Keywords: broader autism phenotype, serotonin, autism, SSRI

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by social communication deficits, as well as stereotyped and repetitive behaviors with early onset and variable expression. Genetic susceptibility plays a large role in ASD. Twin studies through the 1990's supported very high rates of heritability, ranging up to 90% (Bailey et al., 1995; Folstein & Rutter, 1977), although a few recent twin studies have calculated lower heritability rates (Hallmayer et al., 2011; Lichtenstein, Carlstrom, Rastam, Gillberg, & Anckarsater, 2010; Rosenberg et al., 2009). Genetic liability appears to be expressed among unaffected relatives of people with ASD through an independent segregation of features that are milder than, although similar to, the defining characteristics of ASD. This grouping of subtle features of ASD symptomology is commonly referred to as the broad autism phenotype (BAP) and may reflect biological and genetically meaningful markers of risk.

Although the subclinical expression of ASD traits, or endophenotypes, in parents of affected children was first described forty years ago (Kanner, 1968), the BAP has recently become an even more active area of investigation. On average, parents of children with ASD have higher mean ratings on the Aloof and Rigid subcales, as compared to parents of children with other developmental disabilities or typically developing children (Losh et al., 2009; Losh & Capps, 2006; Piven, 2001). Strong evidence for familiality of endophenotypes has been shown for unaffected siblings and parents (P. Bolton et al., 1994; Losh et al., 2009; Losh & Piven, 2007; Piven, 2001). The familial liability associated with the BAP is also evident in the greater prevalence of BAP features in multiplex (MPX) families as compared to those in which only one individual is affected (simplex; SPX). Losh and colleagues (2008) found an elevated rate of BAP traits in MPX, as compared to SPX families or controls. In addition, it was more likely that both parents displayed BAP traits in MPX families (Losh, Childress, Lam, & Piven, 2008). It has also been shown that immediate family members in MPX families have greater social impairments (Szatmari et al., 2000) and decreased emotion recognition skills (Bolte & Poustka, 2003) than those in SPX families. These results have been further supported by recent work suggesting that individuals in MPX families have impairments in the social and communication BAP domains (Bernier, Gerdts, Munson, Dawson, & Estes, 2012). Parents of children with ASD, regardless of whether the families are SPX or MPX, have also been shown to display greater BAP characteristics than those in non-clinical populations (De la Marche et al., 2012) or compared to parents of children with other developmental disabilities (Losh et al., 2008).

Although the BAP is significant in evaluating the presence of important endophenotypes, the identification of related neural chemistry has played an important role in exploring if genetically meaningful relationships can be measured between parent and child. The strong heritability of serotonin system biomarkers (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5HT; (Meltzer & Arora, 1988; Ober, Abney, & McPeek, 2001)), including the role of altered 5HT levels in individuals with autism, has been actively investigated ever since Schain and Freedman's (1961) first report of hyperserotonemia in children with autism. Elevated 5HT synthesis capacity (Chugani et al, 1999) and whole blood 5HT (WB5HT) has been reported in autism probands (Abramson et al 1989; Leventhal et al, 1990; Mulder et al 2004). Heritability has also been evidenced by the strong correlations observed in platelet 5HT (Kuperman, Beeghly, Burns, & Tsai, 1985) and WB5HT levels (Abramson et al., 1989; Cook et al., 1990; Leventhal, Cook, Morford, Ravitz, & Freedman, 1990) of affected children and their first-degree relatives. Recent studies have also implicated SLC6A4, the gene that encodes the 5HT transporter (SERT), in ASD pathophysiology. Association of the serotonin transporter gene (5HTTLPR) short and long (S/L) polymorphism was found in family based association studies of autism, although heterogeneity is present (Cook et al., 1997; Devlin et al., 2005).

The 5HT system has been shown to be involved with restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRB) in persons with ASD. Numerous studies (Sutcliffe et al., 2005; Veenstra-Vanderweele et al., 2012) demonstrate that Gly56Ala, a mutation of the 5HT transporter gene SLC6A4, is significantly associated with increased rigid-compulsive behavior and related to insistence on sameness (IS) behavior, which is a subcategory of RRB (Bishop et al, 2012). IS is characterized by difficulties with changes in routine, ritualistic and compulsive behavior (Cuccaro et al, 2003). These behaviors which underlie IS are similar to obsessive-compulsive behavior, which itself is particularly sensitive to alterations in the 5HT system, as 5HT reuptake inhibitors are among the most promising treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder (Fineberg et al., 2010). As such, obsessive-compulsive symptoms may be particularly sensitive to 5HT, and investigating biological measures of this system in ASD may correspond better to the IS subcategory.

Multiple studies have correlated being a parent of a child with ASD to depressive symptoms, higher parenting stress, and anxiety (Carter, Martinez-Pedraza Fde, & Gray, 2009; Ingersoll, Meyer, & Becker, 2011; Piven et al., 1991), although in some cases parents have a history of depression and anxiety prior to the birth of the affected child (P. F. Bolton, Pickles, Murphy, & Rutter, 1998; Piven & Palmer, 1999; Smalley, McCracken, & Tanguay, 1995). The presence of BAP traits may also predispose parents to depression, as parental BAP and child autism severity are predictors of depressed mood in parents of children with ASD (Ingersoll et al., 2011). In a study comparing depressive symptoms of mothers of children with or without ASD, the presence of BAP traits increased susceptibility to depression in both groups (Ingersoll et al., 2011).

Multiple lines of evidence posit the BAP and 5HT levels as compelling ASD endophenotype and biomarkers, respectively. Of note, very little research, if any, has explored these relationships or the effects of selective 5HT reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) use in parents of children with ASD. As SSRIs are associated with anxiety and mood disorders, which themselves are prevalent in parents of children with ASD, analysis of BAP traits in parents using SSRIs could provide broader insight into the 5HT system. In order to further this line of research, the present study explored the use of SSRIs in parents of a child with ASD to examine the differences in BAP trait expression among parents who are taking SSRIs and those who are not. Using the Broad Autism Phenotype Questionnaire (BAPQ; (Hurley, Losh, Parlier, Reznick, & Piven, 2007)), we analyzed the expression of subclinical ASD traits in parents and their relationship to SSRI use along with proband clinical severity measures. We explored whether parents taking SSRIs would have greater Aloof, Rigid and Total BAPQ scores than those not taking medication based on the observation that statements in the BAPQ may also capture 5HT-related symptom clusters overlapping with anxiety and depression. In addition, we investigated clinical endophenotypes related to 5HT and whether the WB5HT endophenotype is associated between parents and ASD probands. IS behaviors, first described by Kanner in autism, were examined within BAPQ rigidity items as a potential family-related endophenotype. We specifically examined whether measures of parent rigidity or IS on the BAPQ would correlate with proband measures of rigidity and if WB5HT levels of parent and child would significantly correlate with each other.

Methods

Sample Characteristics

Participants in this report were drawn from the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Autism Center of Excellence (ACE). Recruitment for the ACE included pediatrician referrals, clinic referrals, community outreach, and the UIC website among other methods. Inclusion criteria for ACE probands was as follows: between the age of 3-50 years, screened for known genetic disorders, not using psychotropic medications or other medications affecting WB5HT level within 5 half-lives of the medication and an additional 45 days (5 times the platelet lifetime of 9-10 days), no significant birth complication, or history of high lead levels. A description of the study was provided to all participants prior to obtaining informed consent. The study and procedures were approved by the UIC IRB.

Assessments were made using both the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; (Lord, Rutter, & Le Couteur, 1994) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-WPS), along with a best estimate diagnosis of ASD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria (APA, 2000). In addition, parents taking psychotropic medications other than SSRIs were excluded from this study, as were their children. The final ACE sample used for analysis includes children (N=197) and their biological parents (N=357), of which 275 had completed the BAPQ, none of whom were taking psychotropic medications other than SSRIs. Within the group of probands (Male= 162, Female= 35), 139 were diagnosed with autism, and 58 were diagnosed with ASD as per ADOS criteria. Mean proband age was 240 months (SD = 67.32 months). Ethnicity was reported to be 59.5% of the sample identifying as European descent, 17.4% Hispanic, 15.4% African American, 4.1% Asian and 3.6% more than one. The sample was further refined into probands with parents not taking (N = 172) or taking SSRIs (N = 25; one proband with two parents). Within the parent not taking SSRI group, mean age of the probands was 10 years or 120 months (SD = 68 months), and 81.4% was male. For the parent taking SSRI group, the mean age of the probands was 9.3 years or 112 months (SD = 56 months) and 85.7% of the probands were male. Subjects with missing data on individual scales were not included for analyses utilizing the respective measure.

A total of 357 parents participated (N = 161 fathers, 196 mothers), for a total of 161 complete trio families. Mean maternal age was 41 years or 492 months (SD = 84 months), whereas mean paternal age was 44.3 years or 532 months (SD = 96 months). Fathers reported to be 72.1% of European descent, 14.9% Hispanic, 8.7% African American and 4.4% Asian. Of the mothers, 66% reported to be of European descent, 17.8% as Hispanic, 16.8% as African American, and 4.9% as Asian. Of the subset of parents (N=27) on SSRIs, 22 were mothers. This 7.6% sample of parents using SSRIs is lower than the general population (11%), as reported by the 2005-2008 CDC rate (CDC, 2011), but similar in that more women were on SSRIs than men. This lower rate may occur because the sample was recruited and screened to have probands who are not on medication. Medication status was determined by questionnaire prior to obtaining the blood sample per the protocol as described below.

Of this larger data set, only those individuals with completed BAPQ questionnaires, as described below, were included in the analysis (N = 155 maternal, N = 120 paternal). The remaining 82 parents either had missing entries in the BAPQ or did not complete the BAPQ. There were no differences across measures of age, sex, or ethnicity between respondents and those without complete questionaires (p > 0.05). Demographic information about these groups is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of parents with completed BAPQ.

| Not Taking SSRIs | Taking SSRIs | F or χ2 | df | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | ||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 81 | 86 | 17 | 4 | |||

| Hispanic | 24 | 15 | 1 | 1 | |||

| African American | 23 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 12.971 | 12 | NS |

| Native American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Asian | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| More than one | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| N | 136 | 115 | 19 | 5 | |||

| Mean Age in Months (SD) | 495 (83.49) | 531 (95.04) | 485 (82.04) | 553 (38.23) | 4.107 (3) | 274 | <0.01 |

Measures

Broader Autism Phenotype Questionnaire (BAPQ) for Parents

The BAPQ (Hurley et al., 2007) is a Likert-type scale used to determine qualitatively similar characteristics to ASD in parents (Piven, Palmer, Jacobi, Childress, & Arndt, 1997; Piven et al., 1994). It consists of 36 statements which relate to three subphenotypes implicated in the BAP, namely Aloofness, Rigidity, and deficits in Pragmatic Language. Responses range from 1, indicating a statement very rarely applies to the respondent, to 6, which indicates that the statement very often applies. Scoring is completed by summing responses across three individual subscales (Aloof, Pragmatic Language and Rigid), each of which consists of 12 statements. Higher scores on subscales and Total score are indicative of the BAP. Average scores may also be computed across the individual subscales, as well as for the Total. Screening cut off values have previously been established (Hurley et al, 2007), such that exceeding this level indicates a person screens positive for a BAP specific subscale or Total Score. Self-report and informant scores on the BAPQ have been shown to be highly correlated (Hurley et al., 2007). Both informant and self-report questionnaires were administered, but fewer informant questionnaires were completed. Consequently, there was not sufficient data for Best Estimate analysis, and therefore self-report scores were used for analysis in this study.

Six BAP items were identified by nine clinical expert raters as measurements for autism-related IS, in order to have a parent measure that may be more closely related to proband characteristics measured within this study and related to 5HT biomarkers. The BAP-IS subscale was obtained by summing responses across six statements in the Rigid subscale of the BAPQ, namely items 3 (I am comfortable with unexpected changes in plans), 13 (I feel a strong need for sameness from day to day), 15 (I am flexible about how things should be done), 22 (I have a hard time dealing with changes in my routine), 26 (People get frustrated by my unwillingness to bend) and 35 (I keep doing things the way I know, even if another way might be better). This total of IS items was compared to the Rigid score and analyzed along with the Aloof and overall Total scores.

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) for Probands

The ADOS (Lord et al, 1999) is a standardized, semi structured interactive assessment of social interaction, verbal and non-verbal communication, as well as stereotyped behaviors and restricted interests. The ADOS is composed of four modules designed for different developmental and language levels. The appropriate module was used for each proband as follows: 43 received Module 1, 27 Module 2, 107 Module 3 and 20 Module 4. Revised algorithms were used to calculate scores (Gotham, Pickles, & Lord, 2009). Calibrated severity scores were calculated according to revised algorithm scores and age (Gotham et al., 2009) for Modules 1-3 (N=177), so subjects who completed Module 4 were excluded from severity score analyses.

Repetitive Behavior Scale - Revised (RBS-R) for Probands

The RBS-R is an empirically derived, standardized and psychometrically sound rating scale which targets abnormal repetitive behaviors (Bodfish, Symons, Parker, & Lewis, 2000; Lam & Aman, 2007). The RBS-R is composed of 43 items originally grouped into six empirically derived subscales, namely stereotyped behavior, self-injurious behavior, compulsive behavior, ritualistic behavior, restricted behavior, and a total sum score. Recently a factor analysis (Lam & Aman, 2007) produced a five-factor solution (stereotyped behavior, self-injurious behavior, compulsive behavior, ritualistic/sameness behavior and restricted interests) which was used for this analysis. There were a total of 5 probands with missing items on the RBS-R and they were excluded for analyses with this measure (N=192).

Childhood Routines Inventory (CRI) for Probands

The CRI (Evans et al, 1997) is a parental report measure of child's ritualistic, compulsive behavior, initially developed in typically-developing children. It is composed of 19 statements rated on a five-point Likert scale in which responses range from 1 (not at all/never) to 5 (very much/always). Scores are obtained by summation and division by the number of items. The CRI has two principal components, “just right” behaviors and repetitive behaviors. Internal consistency has been shown to be high (0.92; (Evans et al., 1997). This instrument was added in order to better capture obsessive-compulsive symptoms after a portion of the study was completed, therefore 71 probands in this sample did not have CRI data (N=126).

Serotonin measurement for Parents and Probands

Blood samples from 140 probands and 166 parents were obtained. WB5HT is a reliable measure of platelet 5HT because greater than 99% of WB5HT is in the platelet fraction (Anderson, Feibel, & Cohen, 1987). Measurement of platelet 5HT in platelet-rich plasma prepared by centrifugation can add variance due to 5HT release during processing and variable platelet yield. WB5HT was measured by HPLC with fluorometric detection, as described previously (Anderson et al., 1987). Intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 1.7% and 6.2%, respectively. As SSRIs reduce levels of WB5HT (Anderson, 2004), only parents not taking medications affecting blood 5HT levels (psychotropic medications and other medications such as calcium channel blockers that affect WB5HT levels) within 5 medication half-lives and 5 platelet half-lives were included in WB5HT analyses.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses for the data set were conducted using PSAW Statistic v. 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality tests were used to examine deviations from a normal distribution. BAPQ, ADOS, ADI-R and WB5HT measures were not normally distributed (p ≤ 0.043). Square root transformations corrected each variable resulting in normal distributions of phenotype measures, allowing use of the parametric statistics below. Multivariate analyses of covariance tests (MANCOVA) were conducted to examine the effect of medication, as well as to examine differences between maternal and paternal BAPQ scores. As age was significantly different between parental and medication groups, it was used as a covariate in analyses. When parents were characterized as BAP positive according to the previous studies (Hurley et al., 2007), the relationship between BAP status, sex, and SSRI use was examined using χ2 tests. Partial correlations using normalized data, controlling for age and sex of proband, were performed to address relationships between parental and proband measures including WB5HT levels, and proband ADOS, CRI and RBS-R subscales. There were no corrections for multiple analyses. Correlation between maternal and paternal WB5HT was analyzed using Pearson product moment correlation. Two tailed p-values are reported for all correlations.

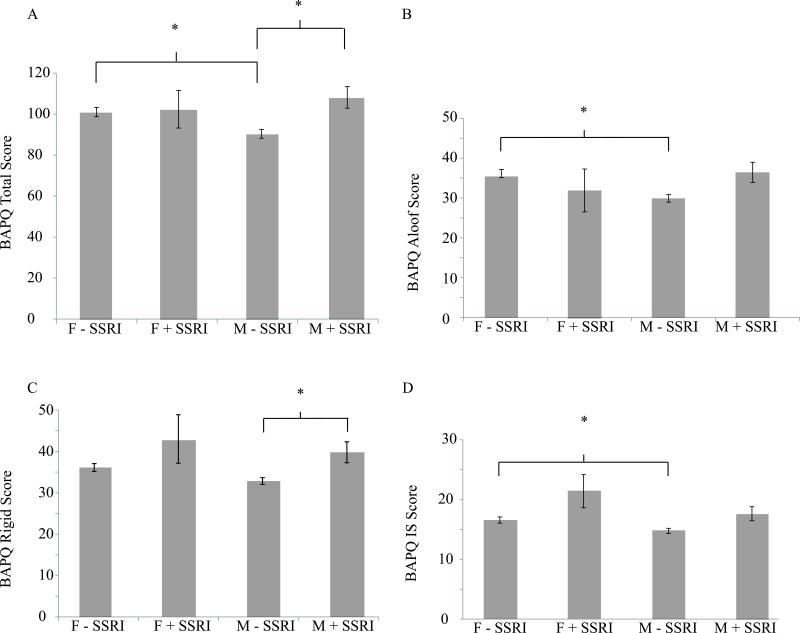

Results

Of the 275 parents in our sample that completed the BAPQ, 24 were taking SSRIs. Within this subset, significantly more mothers (N = 19) were taking medication than fathers (N = 5; χ2 = 5.503, N = 275, 1 df, p = 0.019). The remaining parents were not on any SSRI medications (N = 136 mothers, N = 115 fathers). To determine the differences across parent and medication groups on BAPQ scores MANCOVAs were performed to examine the relationship between sex and SSRI medication use on the Aloof, Rigid and Pragmatic Language subscales of the BAPQ, as well as, the Total and IS scores. Our analyses revealed significantly different average BAPQ scores across sex and medication groups, although the effect size was modest (Wilks’ Λ = 0.878, F(12,707) = 2.963, p =0.001; ηρ2 = 0.041). Specifically, sex and medication had significant effects on the Total score (F(3,270) = 6.014, p = 0.001; ηρ2 = 0.058) and on Aloof (F(3,270) = 6.279, p = 0.001; ηρ2 = 0.062), Rigid (F(3,270) = 5.646, p = 0.001; ηρ2 = 0.055) and IS (F(3,270) = 5.605, p = 0.001; ηρ2 = 0.053) subscales. As shown in Figure 1, post-hoc analyses using the Bonferroni correction revealed that fathers who were not on SSRIs had significantly higher Total (p = 0.005), Aloof and IS subscales scores (p = 0.001, p = 0.047, respectively), compared to mothers not on SSRIs. Mothers taking SSRIs also had significantly higher Total (p=0.021) and Rigid subscale scores (p = 0.026) than those mothers not on SSRI medications (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) BAPQ Total and Aloof, Rigid and IS subscale scores. Lines indicate significant differences across groups. F - SSRI: Fathers not taking SSRIs; F + SSRI: Fathers taking SSRIs; M - SSRI: Mothers not taking SSRIs; M + SSRI: Mothers taking SSRis.

Using established BAP positive screening cutoff criteria scores (Hurley et al., 2007), there was a significant relationship between sex, SSRI use and whether individuals were BAP positive or negative on Total (χ2 = 8.181, N=275, 3 df, p = 0.042) , Aloof (χ2 = 9.442, N=275, 3 df, p = 0.024) or Rigid (χ2 = 9.845, N=275, 3 df, p = 0.020) subscales. As shown in Table 2, more mothers using SSRIs were BAP Total, Aloof and Rigid positive than mothers not taking medication. In addition, significantly more mothers taking SSRIs were BAP Rigid positive than fathers not taking SSRIs. Even though sex-dependent screening cutoffs were used across parents not taking SSRIs, fathers were significantly more likely to be BAP Aloof positive than mothers. However, similar analysis grouping all fathers, and all mothers, together revealed that it is only in the Aloof subscale that significant differences arise between parents such that more fathers score above the cutoff than mothers (χ2 = 4.501, N=275, 1 df, p = 0.034).

Table 2.

Prevalence of the BAP among parents as measured by the BAPQ. Displays significant comparisons between BAP prevalence.

| Not Taking SSRIs | Taking SSRIs | χ2 Performed | df | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aMothers | bFathers | cMothers | dFathers | ||||

| Total | 11.76% | 17.39% | 36.84% | 20% | a,c8.296 | 1,155 | a,c<0.005 |

| Positive | |||||||

| Aloof | 24.26% | 40% | 47.37% | 20% | a,c4.505 | 1,155 | a,c<0.05 |

| Positive | a,b7.153 | 1,251 | a,b<0.05 | ||||

| Rigid | 25% | 20% | 52.63% | 40% | a,c6.261 | 1,55 | a,c<0.05 |

| Positive | b,c9.354 | 1,134 | b,c<0.005 | ||||

The superscripts indicate the groups compared (e.g. noted as a, noted as c).

is a χ2 test between mothers not taking SSRIs

is a χ2 test between mothers taking SSRIs

To further explore the differences across parent and medication groups, we used partial correlations controlling for proband age and sex to examine the relationship between parent BAPQ subscales and child clinical severity measures, focusing on BAPQ subscales that are significantly different across groups. Across the larger sample of parents not taking SSRIs and their children, paternal Total, Aloof, Rigid and IS BAPQ scores significantly correlated with specific ADOS and RBS-R 5-Factor subscales, as well as CRI Total (Table 3). There were no correlations found between the Pragmatic Language BAPQ of fathers, or any BAPQ subscale of mothers not taking SSRIs and proband scores (p > 0.05). However, for children of mothers taking SSRIs, a significant partial correlation was found between maternal BAPQ Aloof scores and proband ADOS RRB total (r=-0.814, df = 12, p < 0.001). There were no other significant correlations found between parental SSRI use, BAPQ scores and proband scores on other ADOS, CRI or RBS-R measures.

Table 3.

Associations between BAPQ scores of fathers not taking SSRIs and ASD proband measures. Partial correlations, controlling for proband age and sex were performed between paternal BAPQ scores and proband clinical severity measures.

| ADOS RRB (df = 89) | CRI Total (df =71) | RBS-R (5 factor) Compulsive Subscale (df = 97) | RBS-R (5 factor) Restricted Interest Subscale (df = 97) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | Sig. (2-tailed) | R | Sig. (2-tailed) | R | Sig. (2-tailed) | R | Sig. (2-tailed) | |

| Paternal BAPQ Total | −0.265 | 0.006 | 0.298 | 0.010 | 0.163 | 0.107 | 0.226 | 0.025 |

| Paternal BAPQ Aloof | −0.216 | 0.04 | 0.322 | 0.006 | 0.205 | 0.042 | 0.230 | 0.022 |

| Paternal BAPQ Rigid | −0.210 | 0.046 | 0.197 | 0.095 | 0.081 | 0.428 | 0.148 | 0.143 |

| Paternal BAPQ IS | −0.244 | 0.020 | 0.171 | 0.148 | 0.071 | 0.485 | 0.099 | 0.327 |

Bolded items indicate statistically significant correlations (p ≤ 0.05).

Use of SSRIs, as well as sex, affected BAPQ scores and correlations between BAPQ and child measures, therefore we investigated the role of 5HT in these relationships. Since SSRI use decreases WB5HT levels (Anderson, 2004), we examined the relationship between maternal and paternal measures for those not taking SSRIs and explored their relationship with proband WB5HT. Partial correlations controlling for proband age and sex among non-Hispanic Caucasian individuals in the study demonstrated a significant relationship between proband and maternal (r=0.319, df=47, p = 0.003), as well as paternal WB5HT (r=0.618, df = 47, p = 0.000). Controlling for age, sex and race across the entire dataset revealed similarly strong correlations (r=0.317, df = 51, p = 0.021; r=0.463, df=51, p = 0.000 between proband and maternal as well as between proband and paternal WB5HT, respectively). In addition, maternal and paternal WB5HT were modestly correlated (r = 0.261, df = 58, p = 0.048). However, there were no significant correlations between proband WB5HT and parental BAPQ measures. Nor were there significant correlations between parental WB5HT and BAPQ measures (p > 0.05). Therefore, the clinical endophenotypes did not show associations with the neurochemical endophenotype of WB5HT levels.

Discussion

The effects of parent gender and psychotropic medication use create observable patterns in BAP endophenotypes. Due to the relationships between BAP endophenotypes and ASD proband clinical subphenotypes, these two factors have an indirect influence on ASD proband clinical subphenotypes. Specifically, we show that among parents not on SSRI medication, fathers score significantly higher on multiple measures of the BAPQ than mothers, including the Total, Aloof and IS subscores. A comparison across mothers taking SSRIs and those not taking medication reveals that the medication group scores higher on multiple measures including Total and Rigid subscales. However, their scores are not significantly different from paternal BAPQ scores of either medication group. In addition, mothers taking SSRIs were more likely to be BAP Total, Aloof and Rigid positive than the non-medicated mothers, and were more likely to be BAP Rigid positive than fathers. While these results show clear differences between sex and medication groups, they also indicate that across multiple measures mothers on SSRIs are similar to fathers not taking SSRIs. In addition, comparison between parents without medication use shows that it is only on the Rigid subscale that fathers are more likely to score above the BAP cutoff than mothers. The differences observed may be due, in part, to the fact that men are less likely than women to seek treatment for mental health problems (Moller-Leimkuhler, 2002).

In contrast to previous studies of the BAP, our sample suggests that subclinical traits segregate not only based on gender but also show different patterns with parents using SSRI medications. Best-estimate scores using both self-report and spouse reports of BAPQ indicate that fathers have higher Aloof and lower Rigid subscale scores than mothers (Seidman, Yirmiya, Milshtein, Ebstein, & Levi, 2012). However, another study utilizing only self-report scores showed that fathers had higher mean scores on all BAPQ subscales than mothers (Davidson et al., 2012). Research using other measures of the BAP such as the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) has shown that fathers have higher levels of BAP, sometimes called quantitative autism trait (QAT; (Davidson et al., 2012; De la Marche et al., 2012)). A possible reason for the disparity in results is the number of families included in analysis (ranging from N = 38 in Seidman et al, 2011 to N=1,650 in Davidson et al, 2012), the population differences in the study cohort of more SPX versus MPX families, and studies not examining the role of medication use. The BAPQ has been validated against direct clinical assessment data and was developed specifically to address the core symptom domains of ASD (Hurley et al., 2007). In the present study, we utilized self-report BAPQ scores in 175 families and explored the effect of psychotropic medication use on measures of the BAP. Study BAPQ scores were significantly different between gender and medication groups, showing some differences in subclinical profiles than have previously been reported. These distinctions between sex and medication groups were also seen across the percentages of each group that scored above the positive cutoff for the individual and total BAPQ measures. Mothers on SSRIs were as likely as fathers not taking medication to be Total and Aloof positive, but were more likely to be Total, Aloof or Rigid positive than mothers not taking medication.

Correlational analyses reveal that paternal BAPQ subscales scores for fathers not taking SSRI medications modestly correlate with multiple proband compulsive and repetitive behavior subscales, as do Aloof subscale measures of mothers taking SSRIs. These results are particularly striking in light of the lack of such associations found in previous studies using the same or other measures of child clinical severity (Seidman et al., 2012). These results may be due to a greater number of families in this study, as well as comparisons exploring parental as well as medication groups. Of note, the correlations across the Aloof subscale on the BAPQ were most correlated with other measures.

Similar to previous results (Ober et al., 2001), this study also shows that WB5HT levels are significantly correlated between parents and children, underscoring the familial relationships between WB5HT. A plausible explanation of the increased BAPQ scores in parents taking SSRIs is that they have BAP related depression, anxiety, and or obsessive-compulsive disorders that are only partially treated by SSRIs. We did not, however, find significant correlations between BAP scores and WB5HT levels within probands or parents even though these endophenotypes show familial patterns independently.

There are several limitations to this study. Due to the small number of fathers taking SSRIs in our sample, caution is warranted regarding understanding the relationship between those scores and either child measures or comparisons between other parental groups. Further caution is warranted as we did not correct for multiple analyses with partial correlations across parental and proband measures. Previous studies have shown that parents of children with ASD have an increased risk (DeMyer et al., 1972; Koegel et al., 1992) and incidence of depression (Piven et al., 1991), and that the onset is often prior to the birth of the affected child (P. F. Bolton et al., 1998). In addition, presence of the BAP may predispose individuals to depression (Ingersoll et al., 2011). The rate of depression is particularly high in mothers of children with ASD (P. F. Bolton et al., 1998), although a recent study has shown that presence of the BAP itself, regardless of whether mothers have affected children, may itself predispose an individual to depression (Ingersoll et al., 2011) or anxiety disorders. These results may explain the greater number of mothers taking SSRIs as compared to fathers. Future studies could compare a group of parents assessed for depression or anxiety as a control for BAP positive parents, which could shed light on the specificity of the phenotypic expressions measured.

Within our sample, BAP endophenotype manifests differently with fathers and mothers of children with ASD but is also related to use of psychotropic medication. Fathers not taking medication have similar scores across many aggregate and average BAPQ measures as mothers taking SSRIs, whereas there are significant differences across multiple measures for mothers in the medicated and unmedicated groups. Furthermore, SSRI use in mothers increases the likelihood of being BAP positive as compared to mothers not taking medication. These results are also reflected in correlations between BAPQ scores for unmedicated fathers or medicated mothers and restricted and repetitive behavior measures in probands. These results argue for further research exploring relationships between the BAP and 5HT endophenotypes. Clinical instruments for parents and probands will need to be further refined in order to capture more distinct endophenotypes across the developmental spectrum and levels of functioning. This will facilitate connecting clinical presentation and behavioral traits to measurable biomarkers as a way of examining genetic risk and liability for development of subphenotypes that contribute to ASD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH Autism Center of Excellence P50 HD055751 (EHC) and K23MH082121 (SJ).

Footnotes

Dr. Jacob is currently with University of Minnesota, Department of Psychiatry, Minneapolis, MN and also has an adjunct position at the University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Psychiatry, Chicago, IL.

Contributor Information

T. Levin-Decanini, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, IL.

N. Maltman, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, IL.

S.M. Francis, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, IL.

S. Guter, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, IL.

G.M. Anderson, Departments of Child Psychiatry and Laboratory Medicine at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

E Cook, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, IL..

S. Jacob, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, IL..

Literature cited

- Abramson RK, Wright HH, Carpenter R, Brennan W, Lumpuy O, Cole E, Young SR. Elevated blood serotonin in autistic probands and their first-degree relatives. J Autism Dev Disord. 1989;19(3):397–407. doi: 10.1007/BF02212938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GM. Peripheral and central neurochemical effects of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in humans and nonhuman primates: assessing bioeffect and mechanisms of action. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22(5-6):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.06.006. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.06.006 S0736-5748(04)00080-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GM, Feibel FC, Cohen DJ. Determination of serotonin in whole blood, platelet-rich plasma, platelet-poor plasma and plasma ultrafiltrate. Life Sci. 1987;40(11):1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, Rutter M. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med. 1995;25(1):63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier R, Gerdts J, Munson J, Dawson G, Estes A. Evidence for broader autism phenotype characteristics in parents from multiple-incidence autism families. Autism Res. 2012;5(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/aur.226. doi: 10.1002/aur.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: comparisons to mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):237–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1005596502855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte S, Poustka F. The recognition of facial affect in autistic and schizophrenic subjects and their first-degree relatives. Psychol Med. 2003;33(5):907–915. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Macdonald H, Pickles A, Rios P, Goode S, Crowson M, Rutter M. A case-control family history study of autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35(5):877–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton PF, Pickles A, Murphy M, Rutter M. Autism, affective and other psychiatric disorders: patterns of familial aggregation. Psychol Med. 1998;28(2):385–395. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Martinez-Pedraza Fde L, Gray SA. Stability and individual change in depressive symptoms among mothers raising young children with ASD: maternal and child correlates. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(12):1270–1280. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20634. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EH, Jr., Courchesne R, Lord C, Cox NJ, Yan S, Lincoln A, Leventhal BL. Evidence of linkage between the serotonin transporter and autistic disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2(3):247–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EH, Jr., Leventhal BL, Heller W, Metz J, Wainwright M, Freedman DX. Autistic children and their first-degree relatives: relationships between serotonin and norepinephrine levels and intelligence. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;2(3):268–274. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J, Goin-Kochel RP, Green-Snyder LA, Hundley RJ, Warren Z, Peters SU. Expression of the Broad Autism Phenotype in Simplex Autism Families from the Simons Simplex Collection. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1492-1. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Marche W, Noens I, Luts J, Scholte E, Van Huffel S, Steyaert J. Quantitative autism traits in first degree relatives: evidence for the broader autism phenotype in fathers, but not in mothers and siblings. Autism. 2012;16(3):247–260. doi: 10.1177/1362361311421776. doi: 1362361311421776 [pii] 10.1177/1362361311421776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMyer MK, Pontius W, Norton JA, Barton S, Allen J, Steele R. Parental practices and innate activity in normal, autistic, and brain-damaged infants. J Autism Child Schizophr. 1972;2(1):49–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01537626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Cook EH, Jr., Coon H, Dawson G, Grigorenko EL, McMahon W, Schellenberg GD. Autism and the serotonin transporter: the long and short of it. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(12):1110–1116. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001724. doi: 4001724 [pii] 10.1038/sj.mp.4001724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DW, Leckman JF, Carter A, Reznick JS, Henshaw D, King RA, Pauls D. Ritual, habit, and perfectionism: the prevalence and development of compulsive-like behavior in normal young children. Child Dev. 1997;68(1):58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, Potenza MN, Chamberlain SR, Berlin HA, Menzies L, Bechara A, Hollander E. Probing compulsive and impulsive behaviors, from animal models to endophenotypes: a narrative review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(3):591–604. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.185. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.185 npp2009185 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein S, Rutter M. Infantile autism: a genetic study of 21 twin pairs. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1977;18(4):297–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1977.tb00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(5):693–705. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, Risch N. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76 archgenpsychiatry.2011.76 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RS, Losh M, Parlier M, Reznick JS, Piven J. The broad autism phenotype questionnaire. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(9):1679–1690. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0299-3. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, Meyer K, Becker MW. Increased rates of depressed mood in mothers of children with ASD associated with the presence of the broader autism phenotype. Autism Res. 2011;4(2):143–148. doi: 10.1002/aur.170. doi: 10.1002/aur.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1968;35(4):100–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Schreibman L, Loos LM, Dirlich-Wilhelm H, Dunlap G, Robbins FR, Plienis AJ. Consistent stress profiles in mothers of children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992;22(2):205–216. doi: 10.1007/BF01058151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman S, Beeghly JH, Burns TL, Tsai LY. Serotonin relationships of autistic probands and their first-degree relatives. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24(2):186–190. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KS, Aman MG. The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(5):855–866. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0213-z. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0213-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal BL, Cook EH, Jr., Morford M, Ravitz A, Freedman DX. Relationships of whole blood serotonin and plasma norepinephrine within families. J Autism Dev Disord. 1990;20(4):499–511. doi: 10.1007/BF02216055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Carlstrom E, Rastam M, Gillberg C, Anckarsater H. The genetics of autism spectrum disorders and related neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1357–1363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020223. doi: appi.ajp.2010.10020223 [pii] 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24(5):659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losh M, Adolphs R, Poe MD, Couture S, Penn D, Baranek GT, Piven J. Neuropsychological profile of autism and the broad autism phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):518–526. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.34. doi: 66/5/518 [pii] 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losh M, Capps L. Understanding of emotional experience in autism: insights from the personal accounts of high-functioning children with autism. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(5):809–818. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.809. doi: 2006-11399-005 [pii] 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losh M, Childress D, Lam K, Piven J. Defining key features of the broad autism phenotype: a comparison across parents of multiple- and single-incidence autism families. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B(4):424–433. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30612. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losh M, Piven J. Social-cognition and the broad autism phenotype: identifying genetically meaningful phenotypes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(1):105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01594.x. doi: JCPP1594 [pii] 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Arora RC. Genetic control of serotonin uptake in blood platelets: a twin study. Psychiatry Res. 1988;24(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller-Leimkuhler AM. Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J Affect Disord. 2002;71(1-3):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00379-2. doi: S0165032701003792 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober C, Abney M, McPeek MS. The genetic dissection of complex traits in a founder population. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(5):1068–1079. doi: 10.1086/324025. doi: S0002-9297(07)61323-8 [pii] 10.1086/324025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J. The broad autism phenotype: a complementary strategy for molecular genetic studies of autism. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(1):34–35. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010108)105:1<34::AIDAJMG1052>3.0.CO;2-D [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Palmer P. Psychiatric disorder and the broad autism phenotype: evidence from a family study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(4):557–563. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Palmer P, Jacobi D, Childress D, Arndt S. Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(2):185–190. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Tsai GC, Nehme E, Coyle JT, Chase GA, Folstein SE. Platelet serotonin, a possible marker for familial autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1991;21(1):51–59. doi: 10.1007/BF02206997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Wzorek M, Landa R, Lainhart J, Bolton P, Chase GA, Folstein S. Personality characteristics of the parents of autistic individuals. Psychol Med. 1994;24(3):783–795. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700027938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg RE, Law JK, Yenokyan G, McGready J, Kaufmann WE, Law PA. Characteristics and concordance of autism spectrum disorders among 277 twin pairs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(10):907–914. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.98. doi: 163/10/907 [pii] 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman I, Yirmiya N, Milshtein S, Ebstein RP, Levi S. The broad autism phenotype questionnaire: mothers versus fathers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(5):837–846. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1315-9. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley SL, McCracken J, Tanguay P. Autism, affective disorders, and social phobia. Am J Med Genet. 1995;60(1):19–26. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320600105. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P, MacLean JE, Jones MB, Bryson SE, Zwaigenbaum L, Bartolucci G, Tuff L. The familial aggregation of the lesser variant in biological and nonbiological relatives of PDD probands: a family history study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(5):579–586. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]