Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the associations between indices of caregiving strain, ruminative style, depressive symptoms, and gender among family members of patients with bipolar disorder.

Method

One hundred and fifty primary caregivers of patients enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) participated in a cross-sectional study to evaluate the role of ruminative style in maintaining depressive symptoms associated with caregiving strain. Patient lifetime diagnosis and current episode status were evaluated by the Affective Disorder Evaluation and the Clinical Monitoring Form. Caregivers were evaluated within 30 days of the patient on measures of family strain, depressive symptoms, and ruminative style.

Results

Men and women did not differ on depression, caregiver strain, or ruminative style scores. Scores suggest an overall mild level of depression and moderate caregiver strain for the sample. Greater caregiver strain was significantly associated (P < 0.05) with rumination and level of depressive symptoms, controlling for patient clinical status and demographic variables. Rumination reduced the apparent association between strain and depression by nearly half. Gender was not significantly associated with depression or rumination.

Conclusion

Rumination helps explain depressive symptoms experienced by both male and female caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Interventions for caregivers targeted at decreasing rumination should be considered.

Keywords: Caregiving strain, bipolar disorder, rumination, depression

Introduction

Up to 93% of family members report strain in relation to the demands of caring for a relative with bipolar disorder (1, 2), particularly when the relative is depressed (3). Caregiving strain is associated with symptoms of psychological distress, specifically depressive symptoms (4, 5). Little is known about why some caregivers experience high levels of depression while others report little or none. Perlick et al. (5) found that higher levels of perceived strain and lower levels of perceived mastery, that is, ability to influence everyday outcomes, were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms over time among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder.

Ruminative style, a cognitive response to stress characterized by persistent negative thoughts, brooding, and inhibition of instrumental coping, has been associated with increased severity and duration of depressive symptoms (6–8). Both depression (9) and ruminative style (10, 11) are more prevalent among women than among men. In a survey of 1132 community-residing adults, Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (10) found that ruminative style mediated the gender difference observed in depressive symptoms associated with chronic role strain, and that low mastery amplified the effects of ruminative style on depression. They speculated that women utilize rumination more often consequent to the strains associated with assuming the majority of child and elder care responsibilities and household duties, coupled with unequal societal and relationship power status, and lower levels of perceived mastery. Female caregivers perform more caregiving tasks and report experiencing higher levels of strain and depression than do male caregivers (12–14).

Aims of the study

This study aims to evaluate the association between ruminative response style and depressive symptoms among male and female caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder, and the potential mediating role of ruminative style on the relationship between caregiving strain and depression. We hypothesized that both caregiving strain and ruminative style would be positively associated with level of depressive symptoms among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Second, we hypothesized that ruminative response style would be a significant mediator of the association between caregiver strain and depression for female, but not for male caregivers.

Material and methods

Participants

The Family Experience Study (15) evaluated the caregiving strain and coping resources of the primary caregivers of 500 patients participating in the Systemic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), a national longitudinal study evaluating treatment effectiveness of evidence-based treatments and differential outcomes in bipolar disorder (16). Patients enrolled in the primary observational STEP-BD at eight FES sites between 8/1/02 and 1/31/04 provided permission to contact the individual they identified as their primary caregiver. The family member or friend selected had to meet three or more (two for friends) of five criteria (17): i) is a parent or spouse; ii) has the most frequent contact; iii) is the individual who responds in emergency situations; iv) attends treatment sessions with the patient, v) provides financial assistance. Overall, 87.4% or 676 patients gave permission, and 72.5% or 500 caregivers contacted consented. Caregivers who participated did not differ statistically from those who declined on age, gender, education, marital status, relationship to the patient, and whether or not they lived with the patient, and participation rates did not differ by site (15). Three of the eight FES sites (Stanford University Medical Center, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and Case-Western Reserve University) elected to participate in the ancillary study described here that included an additional measure to evaluate the associations between ruminative style and caregiver strain and outcomes, which was obtained on 150 caregivers.

Procedures

Patient Assessments

The patient’s lifetime diagnosis (Bipolar I, II, NOS and Schizoaffective, Bipolar Type) was established based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnosis (16) and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version (MINI Plus Version 5.0) (18). The STEP-BD Clinical Monitoring Form, a semi-structured interview administered by the treating psychiatrist at each clinical visit (16), was used to evaluate whether the patient met DSM-IV criteria for an episode of mania, hypomania, major depression, or mixed episode within the last 30 days.

Caregiver Assessments

Caregivers were assessed at study entry and within 30 days of their relative’s clinical assessment during a 90-min phone or in person interview.

Caregiving Burden (Strain) was evaluated by the Social Behavior Assessment Scale (19), a semi-structured interview assessing both Objective Burden: specific problems experienced in caring for the patient over the past 6 months in three areas: illness-related behaviors (violence or impulsiveness), patient role dysfunction (decline in productivity in work, household chores), and adverse effects (disruption of the caregiver’s own work, social and/or leisure time), and Subjective Burden: the distress associated with these problems. Objective burden represented the degree to which each of the 56 problems was rated as present on a scale of 0 (none), 1 (moderate), or 2 (severe); subjective burden was defined as the distress level experienced in relation to each positively endorsed objective item, rated on the same three-point scale. The total subjective burden score across 56 items (Cronbach ’s alpha = 0.92) was used to evaluate the study hypotheses as this represented the purer measure of perceived strain.

Depressive Symptoms were evaluated by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (20), a 20-item self-report scale evaluating frequency of depressive thoughts and feelings within the past week. The CES-D has been widely used in studies of caregiving strain (e.g., 1, 21) and demonstrated high internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93).

Ruminative Style

A 10-item shortened form of the original 22-item Ruminative Style Questionnaire (RSQ) (6) was used to measure ruminative style. The shortened form is comprised of the items most highly correlated with the full scale that are not highly correlated with classic depressive symptoms (22). Examples of the depressive items not used in the shortened form are ‘Think about how sad you feel’ and ‘Think about how passive and unmotivated you feel’. Participants rated their usual response to each item as ‘never’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’, or ‘always’. Because RSQ items are mostly self- or symptom-focused and research has demonstrated that caregivers tend to ruminate on problems related to the person they care for (23, 24), we included four items assessing rumination about the patient with bipolar disorder, for example, ‘I think, what if __ never gets better?’ and ‘I think about how I don’t get enough help from ___ around the house’. These items represented the most frequently endorsed topics of rumination from a set of 10 items administered to 20 caregivers, excluding any item rated as ‘never’. The internal consistency of the 14-item scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88), and it was highly correlated with the 10-item scale (Pearson r = 0.95).

Statistical analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted to identify sociodemographic and patient clinical variables that were significantly correlated with the dependent variable, to control for their contribution in subsequent multivariate analyses. Twenty variables were examined including caregiver and patient gender, age, education, ethnicity, work status, and patient clinical status. Although none of these variables had a significant association with the CES-D (i.e., Pearson r correlation coefficient of P < 0.05, two-tailed test), we included caregiver age, SES, and patient clinical status in our multivariate model to better evaluate and control for even low effects of these variables, which have previously been associated with caregiver depressive symptoms. Hierarchical, linear modeling was used to test the study hypotheses. CES-D scores were regressed onto the caregiver and patient control variables (Step 1), caregiver subjective strain (Step 2), RSQ (Step 3), caregiver gender (Step 4), and an interaction term (RSQ by gender) in the fifth and final step.

The 10 items of the RSQ load onto two domains: ‘Caregiver Brooding’ and ‘Reflective Pondering’ (22). ‘Caregiver Brooding’ is defined as moody pondering, or thinking anxiously or gloomily about a problem/difficulty and ‘Reflective Pondering ’ refers to self-contemplation to deal with and attempt to overcome problems/difficulties, without accompanying negative affect (22). Our pilot work showed that caregivers endorsed ruminative style items consistent with Treynor et al.’s ‘Caregiver Brooding’ and rarely endorsed items consistent with their definition of ‘Reflective Pondering’. We constructed a six-item ‘Caregiver Brooding’ scale that incorporated two items from the original RSQ and four items (see Table 1) we developed to evaluate rumination about common caregiving concerns (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73), and in a second analysis inserted the Caregiver Brooding scale score in Step 3 in the linear modeling analysis described above.

Table 1.

Items used in the caregiver brooding scale

| 1. | I think ‘What if _____ never gets better?’ |

| 2. | I think the little financial help I get from _____. |

| 3. | I think about a recent situation, wishing it had gone better. |

| 4. | I think about how helping _____ doesn’t leave me with enough time to do everything I want to do. |

| 5. | I think about how I don’t get enough help from _____ around the house. |

| 6. | I think ‘Why can’t I handle things better?‘ |

Items 3 and 6 are from the original scale; items 1, 2, 4, and 5 were developed to reflect caregiver brooding about the relative with bipolar disorder.

Results

Table 2 presents the patient and caregiver sociodemographic characteristics and scores on the RSQ, CES-D, and Social Behavior Assessment Scale. Men and women did not differ in CES-D scores, which were at or slightly above the standard cutoff of 16 for depression (men = 16, women = 18). These scores suggest an overall mild level of depression for the sample. Men also did not differ in rumination or caregiver strain scores. Caregiver strain scores suggest a moderate to high level of strain overall. Table 3 presents the results of the multivariate linear regression model.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics: male vs. female caregivers

| Caregiver variable | Male (N = 55) % or Mean ± SD |

Female (N = 94) % or Mean ± SD |

t/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.75 ± 12.42 | 50.57 ± 12.76 | ||

| Over age 60 | 9.1 | 18.1 | −2.25 | 0.026 |

| Minimum, maximum | 22, 71 | 20, 84 | 2.23 | 0.158 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Caucasian | 20.0 | 14.9 | 0.65 | 0.497 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabitating | 83.6 | 68.1 | 9.74 | 0.008 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 5.5 | 25.5 | ||

| Never married | 10.9 | 6.4 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Full Time | 76.4 | 53.2 | 8.62 | 0.035 |

| Part time | 3.6 | 12.8 | ||

| Retired | 7.3 | 14.9 | ||

| Unemployed | 12.7 | 19.1 | ||

| Socio-economic status* | ||||

| I | 16.4 | 7.4 | 6.52 | 0.163 |

| II | 21.8 | 20.2 | ||

| III | 38.2 | 34.0 | ||

| IV | 21.8 | 28.7 | ||

| V | 1.8 | 9.6 | ||

| Living situation | ||||

| Lives with patient | 81.8 | 66.0 | 4.32 | 0.040 |

| Relation to patient | ||||

| Parent | 18.2 | 45.7 | 23.79 | 0.000 |

| Spouse | 70.9 | 29.8 | ||

| Child | 5.5 | 10.6 | ||

| Other | 5.5 | 13.8 | ||

| RSQ | 21.95 ± 6.15 | 23.22 ± 6.39 | −1.18 | 0.238 |

| CES-D | 16.38 ± 5.77 | 18.11 ± 6.95 | −1.55 | 0.122 |

| Strain | 7.71 ± 8.98 | 10.05 ± 11.17 | −1.40 | 0.163 |

Based on Hollingshead and Redlich’s two-point scale; level I indicates higher socioeconomic status.

Table 3.

Effects of strain, ruminative style, and gender on caregiver depressive symptoms

| Independent variables | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step one: demographics | Age | −0.040 | 0.026 | 0.076 | 0.075 | 0.075 |

| SES | 0.032 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Clinical status | 0.001 | −0.034 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.002 | |

| Step two: subjective strain | Subjective Strain | 0.419*** | 0.213* | 0.212* | 0.212* | |

| Step three: RSQ | Rumination | 0.498*** | 0.498*** | 0.498*** | ||

| Step four: gender | Caregiver Gender† | 0.006 | 0.005 | |||

| Step five: RSQ by gender | Rumination by gender† | 0.001 | ||||

| R2 | 0.003 | 0.172*** | 0.372*** | 0.372 | 0.372 | |

| Adjusted R2 | −0.025 | 0.141 | 0.342 | 0.336 | 0.330 | |

| ΔR2 | 0.003 | 0.169*** | 0.200*** | 0.000 | 0.000 |

RSQ, Ruminative Style Questionnaire.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001.

1, Male, 2, Female.

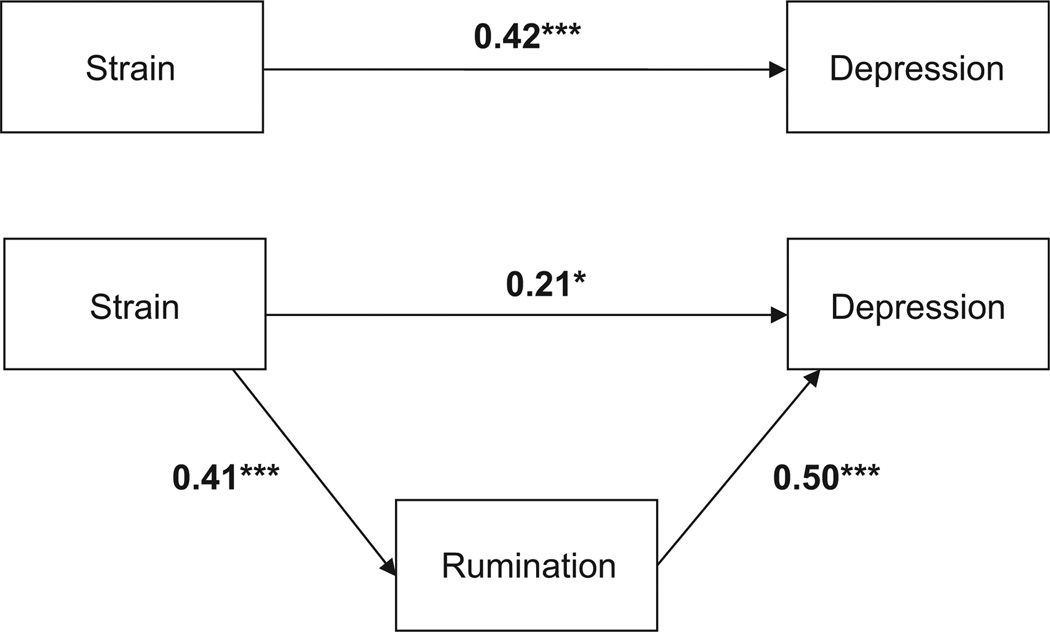

No control variable was significantly associated with CES-D (Step 1). Caregiver strain, entered in Step 2, was significantly and positively associated with CES-D and remained significant with the introduction of the RSQ in Step 3, but its beta weight was reduced by nearly 50%, indicating that the RSQ score accounted for about half of the association between strain and CES-D. Because the RSQ was significantly associated with CES-D (beta = 0.590, P < 0.001) and caregiver strain was also significantly associated with the RSQ (r = 0.468, P < 0.001), the reduction of the effect of caregiver strain in depression observed in Step 3 supports our hypothesis that the RSQ partially mediated the association between caregiver strain and CES-D (Fig. 1) (25). Neither caregiver gender (Step 4) nor the interaction of caregiver gender with RSQ (Step 5) was significantly associated with CES-D. The absence of a difference in the relationship between RSQ and CES-D for men vs. women does not support our hypothesis that ruminative style mediates the relationship between strain and depression only in women. The results obtained with substitution of the Caregiver Brooding (CB) scale for RSQ were highly similar. Caregiver Brooding was highly significant (beta = 0.394, P < 0.001), and inclusion of Caregiver Brooding reduced the beta for caregiver strain from 0.419 to 0.208.

Fig. 1.

Mediational effect of rumination on depression. Numbers represent standardized beta coefficients, after controlling for caregiver age, caregiver SES, and patient clinical status. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that caregiving strain is associated with depressive symptoms among family members of patients with bipolar disorder, and that this association is partially mediated by ruminative style. Rumination accounted for almost half of the association between caregiver strain and depression. The results indicate that strains associated with caregiving do not, in and of themselves, invariably result in depressive symptoms. The results suggest that the tendency of caregivers who experience high strain to ruminate on their difficulties and shortcomings predisposes them to depression. These results are consistent with other studies reporting a link between rumination and later depression (8).

In contrast to the findings of other studies (10), the association of ruminative style with depressive symptoms was not moderated by gender, nor did level of depressive symptoms differ by gender. These results suggest two possible reasons for these findings. It may be the role demands and restrictions of caregiving, not gender, that stimulate ruminations. Women generally assume the majority of routine household tasks in settings with and without a family member needing special care. If rumination is a by-product of role strain, men who assume traditionally female tasks, either by choice or a lack of alternatives, are likely to be more ruminative and experience depressive symptoms, similar to women. Male caregivers in this study reported nearly identical levels of rumination and similar levels of strain and depression as did women. Thus, a second possible explanation for these findings is that men who are more willing to, or drawn to, a caregiver role have a greater tendency toward rumination that also impacts depressive symptoms.

Watkins et al. (26) conducted a comprehensive review of repetitive thought and attempt to explain why some thought is constructive vs. unconstructive. They note ‘Ruminative thought becomes unconstructive if a person experiences an inability to progress toward reducing the discrepancy [between a goal and the current state of events] and at the same time is unable to give up on the reference value or goal’ (26). Caregivers commonly have questions about setting realistic goals for themselves and their loved one and have ongoing questions and concerns about whether those goals are realistic (see Table 1). For example, ‘Is it fair to ask Tom to make his own meals and do his own laundry?’, ‘Should I ask Sally to contribute to the household income?’ or ‘Is it realistic for Hilda to work?’ or ‘Should I be calling José every day to check on him?’ An intervention that can help caregivers gain insight into what assumptions and goals underlie the rumination and brooding associated with caregiving might help to produce more constructive ruminative thought regarding the caregiving role. Perlick et al. (27) have developed a treatment, Family Focused Treatment – Health Promoting Intervention (FFT-HPI), which targets caregivers of persons with bipolar disorder. Among other goals, FFT-HPI examines the caregiver’s automatic thoughts, feelings, and core beliefs about caregiving that sustain symptoms of depression and anxiety and interfere with efforts to seek social support, engage in pleasurable activities outside the home, and practice adequate medical and self-care.

In a randomized controlled trial, FFT-HPI has demonstrated significant reduction in caregiver’s perception of strain related to their loved one’s illness and a reduction in their depressive symptoms, compared to a control condition (27). Other psychotherapeutic approaches that target depressive rumination include mindfulness-based stress reduction (e.g., 28) or Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (29).

Watkins et al. (26) refer to the ‘intrapersonal context’ associated with depressive rumination. Intrapersonal factors can moderate the association of rumination to negative mood. For example, baseline mood state, self-esteem, attitudes toward the self and one’s predisposition to ruminate can impact how rumination then affects one’s current mood state. Interestingly, the Caregiver Brooding items analyzed in this study have more of an interpersonal context than items typically used to assess rumination. For example, the standard RSQ items do not reference interpersonal relationships directly. Thus, a unique aspect of caregiver brooding in particular seems to involve the interpersonal nature of the caregiving role. An interpersonal focus to caregiver brooding might also help explain why the gender-specific findings in this study were not consistent with those observed in prior research on ruminative style.

This study has limitations as well as strengths. Because the study is based on cross-sectional data derived from a largely Caucasian cohort of caregivers, we cannot draw conclusions about causality or infer generalizability to other ethnic groups of caregivers. The uniquely large overall sample enrolled in STEP-BD allowed us to address the hypotheses about ruminative style and depression in caregiver strain in a larger sample than can commonly be secured.

Prior interventions for family caregivers of people with bipolar disorder have tended to focus on education and skills training in problem-solving, communication and/or stress reduction techniques (30, 31). These findings can further research into non-gender-specific caregiver ruminative thoughts as well as help clinicians to consider what aspects of caregiving, such as the interpersonal nature of the rumination, may be contributing most to depression, anxiety and less than optimal self-care habits.

Significant Outcomes

Men and women caregiving for individuals with bipolar disorder report similar levels of caregiver strain, tendency to ruminate and depression symptoms.

Ruminative style accounts for a significant portion of the association between caregiver strain and depressive symptoms.

The association of ruminative style to depressive symptoms was similar for male and female caregivers.

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study and causality cannot be inferred.

The study may not generalize across other US ethnic groups.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant R34 MH071396 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors are indebted to Bruce Rounsaville, M.D., and Carolyn Mazure, Ph.D., for guidance on issues pertaining to treatment development and women’s health, and to the Mood Disorders Support Group of New York. We offer a special thanks to the family members and relatives with bipolar disorder who participated in this initial study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

Dr. Calabrese has received grant support, lecture honoraria, or has participated in advisory boards with Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Otsuka, Cephalon, Dainippon Sumitomo, Forest, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurosearch, OrthoMcNeil, Pfizer, Repligen, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Servier, Solvay, Synosia, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Takeda and Wyeth. Dr. Huth received grant support from Michigan State University. Each of the other authors declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Perlick D, Clarkin JF, Sirey J, et al. Burden experienced by caregivers of persons with bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:56–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinares M, Vieta E. The burden on the family of bipolar patients. Clin Approach in Bipolar Disord. 2004;3:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostacher MJ, Nierenberg AA, Iosifescu DV, et al. Correlates of subjective and objective burden among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Struening EL, Stueve A, Vine P, Kreisman DE, Link BG, Herman DB. Factors associated with grief and depressive symptoms in caregivers of people with serious mental illness. Res Commun Mental Health. 1995;8:91–124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Miklowitz DJ, et al. Caregiver burden and health in bipolar disorder: a cluster analytic approach. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:484–491. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181773927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and distress following a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:105–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, et al. The Temple-Wisconsin cognitive vulnerability to depression project: lifetime history of axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:403–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler R. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;74:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolen-Hoekssema S, Aldao A. Gender differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Pers Indiv Differ. 2011;51:704–708. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yee JL, Schulz R. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40:147–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources and health: an updated metaanalysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:33–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittmund B, Wilms UH, Mory C, Angermeyer MC. Depressive disorders in spouses of mentally ill patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;37:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s001270200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Miklowitz DJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of burden among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder enrolled in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) . Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:262–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) . Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:1028–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollak CP, Perlick D. Sleep problems and institutionalization of the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1991;4:204–210. doi: 10.1177/089198879100400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y. M.I.N.I Plus. Mini international neuropsychiatric interview. English version 5.0.0. University of South Florida-Tampa; 1994, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Platt S, Weyman A, Hirsch S, Hewett S. The Social behaviour assessment schedule (SBAS): rationale, contents, scoring and reliability of a new interview schedule (1980) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1980;15:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyck DG, Short R, Vitaliano PP. Predictors of burden and infectious illness in schizophrenia caregivers. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:411–419. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cognit Ther Res. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roick C, Heider D, Toumi M, Angermeyer MC. The impact of caregivers’ characteristics, patients’ conditions and regional differences on family burden in schizophrenia: a longitudinal analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:363–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stjernsward S, Ostman M. Whose life am I living? Relatives living in the shadow of depression. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:358–369. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:163–206. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Lopez N, et al. Family-focused treatment for caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:627–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams M, Teasdale J, Segal Z, Kabat-Zinn J. The mindful way through depression: freeing yourself from chronic unhappiness. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HD. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ. Bipolar disorder: a family-focused treatment approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinares M, Vieta E, Colom F, et al. Impact of a psychoeducational family intervention on caregivers of stabilized bipolar patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;73:312–319. doi: 10.1159/000078848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]