Abstract

Hispanic women who are 50 years of age and older have been shown to be at increased risk of acquiring HIV infection due to age and culturally related issues. The purpose of our study was to investigate factors that increase HIV risk among older Hispanic women (OHW) as a basis for development or adaptation of an age and culturally tailored intervention designed to prevent HIV-related risk behaviors. We used a qualitative descriptive approach. Five focus groups were conducted in Miami, FL, with 50 participants. Focus group discussions centered around 8 major themes: intimate partner violence (IPV), perimenopausal-postmenopausal related biological changes, cultural factors that interfere with HIV prevention, emotional and psychological changes, HIV knowledge, HIV risk perception, HIV risk behaviors, and HIV testing. Findings from our study stressed the importance of nurses' roles in educating OHW regarding IPV and HIV prevention.

Keywords: HIV, intimate partner violence, older Hispanic women, prevention

Approximately 1,185,000 people are currently living with HIV infection in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009). As noted by the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States (White House Office of National AIDS Policy, 2010), people who live in geographical hot spots (e.g., the southeast region of the United States, specifically Miami, FL) are considered to be at greater risk of acquiring HIV than their counterparts in other areas. In 2009, Florida was ranked as the leading state for the number of reported cases of HIV infection (13%), followed by California (11%) and New York (10%) (Florida Department of Health [FDH], 2009).

Between 2003 and 2007, the number of newly reported AIDS cases among women ages 50 years and older in the United States increased by 60% (Population Reference Bureau, 2009). It has been estimated that 15% of all newly reported cases of HIV infections occur among people older than 50 (CDC, 2007; Valdez, 2011). In Florida, newly reported HIV cases among older people increased by 47% from 2001 to 2010 (FDH, 2010a). A dramatic indication of health disparities and high risk for HIV acquisition in Hispanic communities can be seen in the proportion of AIDS cases in Florida. AIDS cases in Florida have decreased 12% among non-Hispanic Whites but increased 20% among Hispanics (FDH, 2010b). HIV infection rates for older Hispanics in the United States are 5 times as high (21.4/100,000) as rates for their non-Hispanic White counterparts (4.2/100,000; CDC, 2007).

Older women, particularly Hispanic women ages 50 years and older, are at a high risk for HIV infection, despite being the least studied minority group in the United States with regard to health and social practices or sexual behaviors. In 2007, older Hispanic women (OHW) accounted for 23% of all HIV cases among Hispanic women (FDH, 2011). In Florida, 32% of women living with HIV were 50 years of age or older, 19% of the newly reported cases of HIV infection were OHW, and 81% of these OHW were exposed through heterosexual contact (FDH, 2010a). In the face of such staggering statistics that clearly reflect a drastic increase in HIV infection among OHW, we believe there is a demanding need to better understand and address the factors that may be placing this population at increased risk in order to confront the existing health disparity. The number of HIV cases in older women is expected to continue to increase as women live longer and continue to engage in sexual activity (Lindau et al., 2007; Sormanti & Shibusawa, 2007).

Along with general factors that increase the vulnerability of older women to HIV, a number of specific cultural factors place OHW at particularly high risk for HIV; these factors have not often been addressed in the literature, including (a) intimate partner violence (IPV; e.g., long-term adverse health effects of partner violence, sexual violence); (b) perimenopausal-postmenopausal related biological changes (e.g., age-related changes in vaginal tissue); (c) cultural norms (i.e., endorsement of values related to machismo and marianismo); (d) emotional and psychological factors resulting from loss of partners and network support (e.g., depression, isolation); (e) gaps in HIV related knowledge; (f) low HIV risk perception; (g) high risk sexual behaviors among older people who find themselves back on the dating scene and unable to negotiate safer sex; and (h) ignorance of the value of being tested for HIV (Auerbach, 2003).

Interpersonal Violence

According to Mouton and colleagues (2004), postmenopausal women are exposed to abuse at similar rates as younger women. Abuse poses a serious threat to the health of older women and is associated with premature morbidity and mortality. Verbal, physical, or sexual IPV are areas that health care providers may not assess or ask older women to discuss (Bonomi et al., 2007). Furthermore, older women may be reluctant to disclose IPV to other people including health care providers. It has been found that in situations in which older women did disclose experiences of IPV, they felt discounted and unsupported (Zink, Jacobson, Regan, & Pabst, 2004). It also has been documented that victims of IPV reported higher frequencies of HIV risk factors than their non-abused counterparts. These high-risk behaviors included sex with a partner who insisted on not using a condom; sex with a man known or suspected to be an intravenous drug user; or sex with someone who experienced symptoms of, received a diagnosis of, and/or was treated for a sexually transmitted infection (STI; Sormanti & Shibusawa, 2008).

Perimenopausal-Postmenopausal Related Biological Changes

Women ages 50 and older are more vulnerable to HIV due to normal, age-related biological changes such as decreasing levels of estrogen that lead to a reduced production of vaginal lubrication and vaginal tissue thinning. These changes increase the risk for vaginal tearing and trauma during intercourse (Savasta, 2004). In addition, the Agenda for Research on Women's Health for the 21st Century (Office of Research on Women's Health [OWH], 1999) reported that as people age, the immune system naturally weakens resulting in an increased likelihood of contracting infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, STIs).

Cultural Factors

Cultural factors are believed to be some of the largest contributors to the rapid increase of HIV among Hispanic women (Peragallo et al., 2005). Although Hispanic groups are diverse, shared Hispanic cultural norms (e.g., machismo, marianismo) dominate navigation of the social environment and social interactions.

Machismo is a cultural norm that identifies men as strong and protective of the family and encourages men to be dominant in relationships, promoting sexual prowess, risk-taking behaviors, multiple partners, and having younger partners (Cianelli, Ferrer, & McElmurry, 2008; Marin, 2003). In addition, sexual relationships are defined in terms of penetration in heterosexual vaginal intercourse, whereas encounters without penetration are not considered to be sexual relationships (Schneider & Stoller, 1995). The use of sildenafil (Viagra®) and similar oral phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitor drugs may increase male partners' opportunities to engage in sex (Beaulaurier, Craig, & De La Rosa, 2009).

Marianismo encourages women to be sexually passive and submissive, accepting male partners' decisions on all sexual matters. The expectation that men will have multiple partners increases the chances that women may be at risk of acquiring HIV due to their partners' sexual activities (Cianelli et al., 2008).

HIV-Related Knowledge, Risk Perception, High Risk Behaviors, and Testing

Older women tend to have limited or inaccurate knowledge about HIV when compared to their younger counterparts, which can be attributed to the lack of attention to their age group in HIV prevention messages (Jacobs & Thomlison, 2009). When an older woman finds herself back on the dating scene, she is often unaware of the sexual risks and will typically perceive herself as at low risk for acquiring HIV (Auerbach, 2003).

Many sexually active older women are at increased risk of acquiring HIV due to their male partners' behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex, injection drug use). In addition, older women tend to view condoms primarily as a method of contraception; if they no longer fear unwanted pregnancy, they may not insist on condom use (Neundorfer, Harris, Britton, & Lynch, 2005).

The common misperception that older people do not have sex has lead health care providers to view this population as being at low risk for HIV infection. Clinicians are, therefore, less likely to test older people for HIV and are more likely to diagnose older adults at a later HIV infection stage (Savasta, 2004). In addition, stigma surrounding the sexual needs of older women can result in decreased HIV testing (Laganà & Maciel, 2010; Mack & Ory, 2003).

The purpose of our study was to investigate factors that increase the risk of acquiring HIV in OHW. We felt this information was needed to develop or adapt an age and culturally tailored intervention to prevent HIV risk behaviors.

Method

Design

A mixed methods design including collection of both qualitative and quantitative data was used for our study. This paper reports on the qualitative findings. A qualitative descriptive approach using focus groups was used as the method to elicit information. A qualitative descriptive method is the approach of choice when descriptions of the phenomena are desired directly from the source and when the researchers want to stay closer to the data and to the meanings participants give to their experiences. Language provides the vehicle of communication as interpretive structure that must be read (Sandelowski, 2000).

We chose focus groups to gather information about shared norms, values, and experiences of a specific, relatively homogeneous group. Focus groups have been shown to provide rich information about participants' common experiences (Duggleby, 2005; Van Eik & Baum, 2003). The researchers obtained information from guided group discussions with participants to disclose aspects of the phenomena that were less accessible in other research methods.

Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited from Open Arms Community Center, a nonprofit public charity organization located in West Miami, FL. Open Arms Community Center provides a broad range of services to the Hispanic Community. These services include health education, public assistance application, emergency food program, refugee and senior citizens program, legal and job assistance, and development programs. We selected Open Arms Community Center because of the large population of Hispanics that it served. In addition, this setting has been used in previous studies with OHW. The site liaison, in conjunction with the study team, assisted in recruitment activities. Potential participants were approached and given a brief description of the study to determine their interest in participation. If a woman was interested, the site liaison asked permission to provide her name and telephone number to a study staff member. In addition, the research team placed fliers at popular gathering spots for Hispanic persons in the community (e.g., churches, community centers, grocery stores, service agencies, laundermats, libraries). Women who read the fliers and were interested in the study called a toll-free study telephone number. Study staff members contacted potential participants to further describe the study and determine eligibility. If a potential participant was interested and met inclusion criteria, an appointment to obtain consent was made. After informed consent was obtained, an assessment was completed, and focus groups were scheduled.

To be eligible for this study, women had to (a) self-identify as Hispanic, (b) be 50 years of age or older, (c) live in Miami Dade County, FL, (d) be or have been sexually active in the previous year, (e) be able to read in English or Spanish, and (f) be willing to participate in our study. The institutional review board (IRB) from the University of Miami approved the study prior to commencement of data collection.

Data Collection

We conducted five focus groups with a total of 50 participants (i.e., 10 participants per group) led by the principal investigator (PI) and co-investigator of our study. Both the PI and co-investigator were bilingual and had experience in running focus groups. All groups were conducted in Spanish in accordance with participants' preferences. Before each focus group, refreshments were provided that allowed time for the participants to speak informally with the facilitators.

At the beginning of each focus group, the facilitator read the consent form to participants, asked them to follow along with the reading, and requested that they ask any questions they had prior to the commencement of the focus group. Once participants agreed to participate, the facilitator asked them to sign the consent form.

The facilitator conducted the focus groups using a discussion guide. The questions chosen to guide the discussion were based on literature review and the expert opinion of women's health and HIV specialists. The questions were related to HIV in OHW such as: Do you know if HIV is affecting Hispanic women who are 50 years of age and older in your community? Is there something else that you want to share about HIV and OHW? What do you know about older women having younger sexual partners? What can you tell me about your experience related to sex during menopause? What can you tell me about symptoms that you have experienced during menopause? Probes were used to stimulate discussion among the group participants. The focus groups lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, and they were recorded using digital technology to assure clarity of responses and to facilitate accuracy of transcriptions.

Saturation was used to determine the sample size for the qualitative portion of the study. At the point when no new data were emerging from the focus group discussions, we deemed the topic to be saturated, indicating that the limits of the phenomena had been covered, at which point the focus groups were terminated. To accurately describe the phenomena under study, saturation of data in our project was achieved with five focus groups with a total of 50 participants.

We took extra precautions to ensure that transcribed data were accurate across the language variations as well as to ensure the privacy of our participants. The PI of the study listened to the focus group tapes and reviewed transcriptions for accuracy. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim in Spanish and English for content analysis by a transcription and translation service. We were careful not to include any identifying information in the transcriptions. The research staff meticulously reviewed the transcriptions to verify that there were no discrepancies between the Spanish and English versions. Data were stored in a locked area for research files and the digital files were saved in password-protected computers.

Data Analysis

We used content analysis to identify and define the major themes that emerged from the focus groups. Content analysis is a method used to recognize, code, and categorize patterns from text data (Sandelowski, 2000). In analysis of the transcripts, we specifically used directed content analysis, a type of analysis recommended when there is prior literature related to the phenomenon of interest that can benefit from further description (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

In order to transcribe the data, we had three coders read the transcripts and code them line-by-line. Two of the transcribers were bilingual in Spanish and English, and one was English speaking. Based on a literature review of experiences of working with older women, broad categories were defined for the purpose of coding. A codebook and a coding sheet were developed to facilitate the coding process. Each of the three coders coded each line independently from the other coders. At the point of completion, the results were compared, and 90% agreement was obtained. Final themes were decided through consensus among the research team members.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

The participant's mean age was 55.7 ± 6 years of age (range = 50 to 76 years). The mean number of the years living in the United States was 18.2 ± 13 years. Of the participants, 36 (72%) were from Cuba, 6 (12%) from Colombia, 2 (4%) were from the Dominican Republic, 2 (4%) from Puerto Rico, and 4 (8%) were from other countries including the United States. All of the participants had more than 12 years of education. In regard to marital status, 15 (30%) participants were married, 16 (32%) were single, 14 (28%) were divorced, and 5 (10%) were widowed. However, 34 (68%) of the participants reported living with their partners. The majority of the participants (n = 29, 58%) reported being Catholic, 9 (18%) Evangelical or Christian, 6 (12%) mentioned other religions, and 6 (12%) reported not having a specific religion. At the time of the study, 34 (68%) participants were not working. The participants' mean monthly per capita income was $609 ± $380 (range = $10 to $1,600). Major sources of income in decreasing frequency were Social Security and other government assistance, partners or husbands, remunerated jobs, and families and friends (note: some participants reported more than one source of income so ns added up to more than 50 and percentages added up to more than 100%).

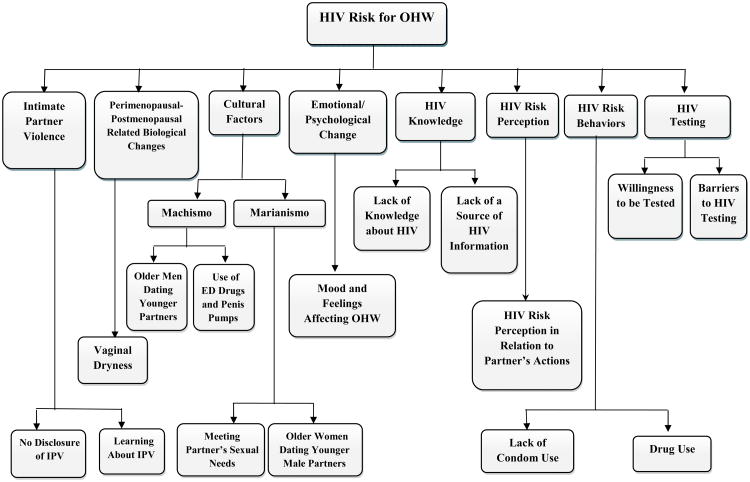

Eight major themes related to HIV and OHW were included in the qualitative analysis. These included: (a) IPV, (b) perimenopausal-postmenopausal related biological changes, (c) cultural factors that interfere with HIV prevention, (d) emotional/psychological changes, (e) HIV knowledge, (f) HIV risk perception, (g) HIV risk behaviors, and (h) HIV testing (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Coding diagram.

Note. IPV = interpersonal violence; ED = erectile dysfunction; OHW = older Hispanic women.

Interpersonal Violence

The theme of IPV contained ideas, feelings, and experiences women may encounter in relation to the experience of violence with partners and that may increase women's risks of acquiring HIV. More specifically, we assessed our participants' willingness to discuss or disclose experiences of IPV as well as their desires for education on IPV prevention.

Nondisclosure of IPV

The focus groups had specific segments designed to address IPV, initially with indirect questions. At no point did conversation about IPV occur spontaneously. Even when direct questions were asked about IPV, only a few participants responded, and most of the responses were vague and indirect. It was evident that, despite our coaxing, the participants did not want to talk about past events. However, they did provide strong statements indicating that they would not accept violence from a partner at this stage in their lives. One participant said, “Twenty something years I suffered … violence from my partner …”. Another participant elaborated:

Well, my blessing was coming to this country … because here, nobody can humiliate or beat you, nobody can … Do you understand? It is very good, and I wish the father of my children had been in this country so he would be in jail all his life.

Yet another participant asserted, “I tell you the truth, in my particular case, if I have to be with an older man who causes me trouble [IPV], I don't want him by my side. So for me, that's it”.

Learning about IPV

A majority of participants gave negative responses when the facilitator asked if they would like to learn more about IPV should it occur in the future. Participants reacted, “No, definitely no violence” and “No, not violence.” However, a few positive other-oriented responses were also provided. For example, one participant said,

That [education] is good because we can teach women, that may help our children, our family … everything we can learn is never in excess … everything is welcome, and we can give advice to others that is true.

Another participant commented, “Well, you learn to help others. Not my case, but you can always help. In the case of a friend or something.”

Perimenopausal-Postmenopausal Related Biological Changes

The theme of perimenopausal-postmenopausal related biological changes included vaginal dryness as a factor that can lead to vaginal tearing, thereby placing older women at higher risk for contracting HIV during unprotected sexual intercourse. In our study, we found that the majority of the participants mentioned vaginal dryness as a serious problem they encountered that had negative effects on their sexual lives due to painful intercourse. In an attempt to overcome this problem, participants reported using different things (e.g., hormonal patch, lubricants, hand cream). One participant elaborated:

One of the most important things is the lack of vaginal lubrication. Thus, we look for formulas, such as the gel we are prescribed, or the one we buy at the shop … and we solve that part, which is one of the hardest, because sex sometimes becomes painful instead of satisfying.

Several women stated that they used saliva (i.e., “spit” on their fingers) in an attempt to lubricate themselves.

Cultural Factors That Interfere with HIV Prevention

The third theme presented was cultural factors that interfere with HIV prevention. Two factors specifically relate to Hispanic culture that interfere with HIV prevention: machismo and marianismo.

Machismo

The subtheme of machismo included the perceptions, opinions, ideas, and feelings that women have about men with relation to HIV transmission or acquisition among older women. Specific subthemes discussed during the focus groups that related to machismo were male partner infidelity with younger partners and the use of drugs for erectile dysfunction or penis pumps.

Participants said that they sometimes considered men's infidelities to be expected, and they usually forgave their husbands after their husbands had an affair. Moreover, there were times that older women still blamed themselves for their partner's infidelities. Participants discussed that older men had a preference for younger women as sexual partners. One participant commented,

Older men have always looked for younger girls, always … we were all young girls, and older men have always tried … however, younger men do not care, most of them, to be with a mature woman.

Another participant elaborated, “Old men want more sex than young men. Because they have less ability, they are afraid already. And so they look for young people.” However, married men would continue to have sex with both their spouses and younger partners. The situation of infidelity increased married OHW's risk for acquiring HIV.

As a second subtheme related to machismo, Hispanic sexual relationships emphasize penetration in heterosexual vaginal intercourse; without penetration, there is considered to be no sexual relationship (Schneider & Stoller, 1995). Jones, Patsdaughter, and Martinez Cardenas (2011) noted that Hispanic heterosexual men have been reluctant to acknowledge that they needed to use erectile dysfunction drugs for sexual activity. However, participants in our focus groups mentioned the use of these drugs and penis pumps as common practice among older men to improve erections. Participants stated that older Hispanic men preferred to use the implanted penis pump or “bombita” instead of erectile dysfunction drugs because the bombita did not have medical complications. The participants emphasized that the use of the erectile dysfunction drugs and the bombita increased the sexual activity of older men by increasing their functionality as partners with fewer fears of incapability. One participant commented:

Because the pump is easier--you have it already, but you have to go and buy Viagra®, take the pill. The other is easier. Yes, the pill always has secondary effects--doesn't matter where, it will always have some. The pump seems to be more practical. So I tell you the pump is really popular.

Another participant elaborated:

That is one trend [penis pump] … I know old men who are almost 85, my neighbor who is … he went to put on the pump …the father of my children, who is over 60, put on the pump. With Viagra®, you can take some, but with a lot get you sick.

Marianismo

The subtheme of marianismo included perceptions, opinions, and ideas that participants may have had about gender roles and social, sexual, and economical subordination that can increase OHW's risk for acquiring HIV. The following subthemes were discussed during the focus groups: the need to meet partners' sexual needs and older women dating younger partners.

Participants stated that they felt they needed to please their partners and meet their partners' sexual needs regardless of their own sexual desires. The expressed rationale behind this belief was that participants were afraid that their partners would look for other women to satisfy their sexual needs if they did not. Participants also believed that if their partners were to have affairs, they might lose the partner and remain alone. Fears and submissive relationships with male partners make it less likely that OHW would be able to negotiate protective measures (e.g., condom use) to prevent HIV infection. One participant explained:

I have been many years with my husband, and when he wants to have sex, I can't tell him “I don't want to. “ I have to accept what he wants …because he's my husband, and he's not to blame for the fact that I don't feel well with myself--that I don't want to do it or that I have problems with myself. I must meet his needs, and I have to accept it when he wants to do it.

In accordance with traditional customs of Hispanic culture, it is not accepted for an older woman to have a younger partner. Participants validated that OHW who fall in love with younger men are subjected to derision. However, it appears that this situation is changing. Participants discussed how many OHW are now dating younger men and are open to the idea of having new sexual partners. One participant commented, “I do not care about dating a 35-year-old man because I do not care anymore about what people say because I feel self-confident.” Another participant said, “My husband is 15 years younger than me. We didn't meet yesterday--we've been together for 10 years, and this is my second husband.” Yet another participant stated, “I know a lot of older women who have young men. They go to look for them in Cuba.” However, participants also revealed that there were specific places in Miami where OHW go to find younger partners. One participant elaborated:

[There are places] where older women go and new immigrants come, new young boys--they go and catch them. They are older women, not like us, much older--older women called “sisters to the rescue” because they go after young boys who just come with no money. They are old rich woman--20, 30, 40, 50 years older.

Emotional and Psychological Changes

The theme of emotional and psychological changes included factors such as depression, loneliness, and sadness. These symptoms may increase the desires of OHW for companionship and placed them at increased risk for acquiring HIV.

Participants described how sadness, depression, and hopelessness were feelings they experienced in their daily lives related to events such as chronic health conditions, economic problems, loneliness, and the lack of having a partner. Participants discussed how changes in appearance related to aging as well as inabilities to perform activities as in the past evoked progressive feelings of sadness and depression. The increasing desire to feel accepted and loved place OHW in vulnerable positions to accept relationships with partners despite their partners' intentions. While OHW may be looking for companionship, partners are sometimes more interested in money, immigration status, or pleasure rather than genuine companionship, which cause OHW to find themselves in environments of risk taking behaviors with a lack of knowledge to appropriately handle the situation. One participant reported:

And he told me “Go to the gym” … and I said, “Oh, yeah, because you go out on the street and you see women with nice bodies. I know I'm of a certain age, but I will look good for you, and when you're old, when you have money, you will pay for my breasts and the rest of the things.”

Another participant said:

I'm a 54-year-old woman, and I have met a younger one who is 45, 35 years old, and my oldest son is 30. Maybe he's with me because I have money, a good house, a good car, good economic power--and that's why he loves me. It's not because he wants to have sex with me or because he wants to have a life with me, nothing like that. He loves me because of his own interest.

HIV Knowledge

The theme of HIV knowledge included misconceptions and myths that women have about HIV. Elements of the lack of knowledge included the truth of information; how HIV knowledge is transmitted, acquired, or avoided; and the sources from which OHW learned about HIV.

Participants discussed how a perceived problem in the community was a lack of information and misconceptions about how HIV was transmitted and prevented. Many participants admitted they did not know how to use a male condom and they had never seen a female condom. In all of our focus groups, participants expressed a desire to learn about HIV and information related to older women. One participant asked, “How long can the virus be there without coming out and exploding?” Another participant elaborated,

We are generally speaking of Latin men, European men, we all know the statistics … that it is spreading, it is spreading--but we are not yet aware of the disease, how you get it, how to avoid it. We haven't studied it.

Participants also expressed beliefs that they did not have reliable sources of HIV information. They reported they had some knowledge from their daily interactions in which someone shared second-hand information about the disease and related topics. However, participants noted that shared information was never specific to their age group. On recollection, participants thought there were fewer public HIV prevention campaigns in comparison with previous years. One participant emphatically shared:

Nowadays, what is happening is that in the 80s, when AIDS appeared, there was more protection than today--in a nightclub or in any place where you went. Nowadays, we aren't investing time telling people how to protect themselves. At the beginning, when you arrived at the nightclub, you found condoms there. They talked to you about it--but not anymore, they don't talk about it. Since there's no communication, there's nothing. So there are more infected people because nobody is interested in the fact that nobody is talking about it. At the beginning, we talked about it everywhere, and we were given condoms, but not now! Now it's different!

Another participant corroborated,

There was much more information on AIDS before, on how to protect yourself. It was in almost every television show, through the radio--they remind you of it all the time. Now there is not that much advertising on it, it's like it has been decreased.

HIV Risk Perception

The theme of HIV risk perception contained the ideas and beliefs that women have with regard to the possibility of contracting HIV. The theme included women's perceptions of HIV risk in relation to their partners' actions.

Our participants were concerned about the risk of HIV infection; however, we can infer that they were not fully aware of their own personal risk of acquiring the disease. The majority of participants did not recognize certain behaviors as a risk for acquiring HIV (e.g., having more than one partner, having younger partners, lack of condom use, alcohol use). Lack of knowledge led to false perceptions of risk that were directly related to low intentions regarding HIV testing and fewer HIV prevention behaviors. Participants explained that they still believed that the responsibility for safer sex fell on the man and that he was entitled to the option of having as many sexual partners as he wanted or needed, thus increasing OHW's risk for acquiring HIV.

Some participants did, however, appreciate that they were at increased risk of acquiring HIV through their partners' behaviors such as engaging in risky behaviors, infidelities, lack of condom use, and “macho” characteristics. The participants acknowledged that they were able to form these opinions based on second-hand information rather than a direct knowledge of HIV risk factors. One participant stated:

I have a partner, a stable partner. I assume he doesn't cheat on me. There is always a risk, but I assume he does not. And sometimes we people believe that because of a stable partner … I know now that there is a risk. But to start using condoms, to me, it would be a problem.

Another participant stated, “You are more at risk … men are worse, they react quickly, there is always a risk. He may be very faithful now, but tomorrow he's already changed.”

HIV Risk Behaviors

The theme of HIV risk behaviors included male and female behaviors or actions that were perceived by women as increasing the probability of HIV transmission or acquisition (e.g., lack of condom use, drug use). Participants in our study were concerned about suggesting condom use to their partners for fear that their partners might misinterpret their intentions. Most women feared their partners would accuse them of cheating if they suddenly suggested condom use. Participants generally viewed condoms as primarily a method of contraception. In the case of OHW who no longer have concerns about unwanted pregnancies, condom use was often deemed unnecessary. One participant told us, “If I was, for example, to have a casual relationship, I would surely use a condom, and if my husband did the same, I would appreciate if he used one, too. “ Another participant elaborated:

I've been with him for so long, and it is a relationship I consider a good relationship, stable, and I don't see any sign that he is doing anything like that. They say where trust is there is danger. Anyway, but personally, we do not use it, but I do recommend it for people, who are, as they say, like butterflies, from flower to flower.

Yet another participant said:

I wanted to say, for example, that men use condoms but not in oral sex. I have never heard anybody who uses protection, and if you have a sore in your mouth or anything, you can be transmitted as well. What's more, there are people who don't know that they can get the disease by oral sex. I think few people know that condoms are not only for vaginal sex--that they can be used for oral sex.

One participant discussed the risk of multiple partners and unprotected sex:

Those men who date women and men--they don't even wear a condom sometimes, and they have sex with one man, other man, and the man has AIDS, and then he gets it and then infects his female partner. And that happens. Those are terrible cases, and it happens.

Drug use was another important subtheme under HIV risk behaviors. Participants in our study stated that substance use was a frequent occurrence among some older individuals. The most common was the use of alcohol, followed by marijuana and cocaine. Frequently, the use of substances was associated with sex. One participant relayed her friend's situation:

When she is going to have sex with her partner, what she does is she smokes--she smokes marijuana, “It is not that I grab it, and I am stoned, ” she says. “I have it only for medicine. ” She tells me, “I don't know, it makes me change totally. ” It makes her change, and I asked her, “In what way? ” She says, “I don't know, but I get desperate, I am different.”

Another participant reported on a different type of substance use related to sexual behaviors. She recalled, “I heard, a friend told me that before having sex with his partner, he spreads a little powder in her vagina, so that she feels the desire. I have heard that … it's a drug. It's cocaine.”

HIV Testing

The theme of HIV testing contained factors that OHW perceive as positive or negative related to HIV testing, including rapid tests versus traditional tests, health system accessibility, cost, and accessibility of testing locations. Participants in our study stated that they would be willing to be tested if it could be done quickly and by using saliva rather than blood. One participant stated, “I think that the most appropriate is cotton in the mouth. It takes half an hour to know the results. Performing the AIDS test and waiting to be given the results, you are dying waiting there.” Another participant elaborated, “For everyone. Men too. And in a place where it is performed for free [HIV testing] and its not complicated--it would be annual like the Papanicolaou [test] or mammography and all those exams you have to take periodically.”

However, participants also discussed some of the perceived negative aspects of HIV testing, specifically the knowledge of their serostatus and the cost of the HIV test. Some women were afraid to get tested because they were afraid to learn if they were infected with HIV. One participant explained, “I don't want to take any test because knowing too much is bad.” Another participant addressed the burden of cost, “Do we have to pay for those AIDS tests? Yes, we have to pay for them. That is why there is so much AIDS in the streets, and people don't see it”. And another participant elaborated, “And the government … has not allocated money for you to say ‘I am going to take the test’, or it is free. We need to have funds for that.”

Discussion

Our study findings provide contributions to the existing knowledge base regarding OHW and their risk factors for acquiring HIV. Considering the lack of research that has targeted OHW, being able to understand the interaction of several factors (e.g., intimate partner violence, cultural norms of machismo and marianismo, peri- and postmenopausal changes, HIV knowledge, and risk perception) is essential to develop or adapt age- and culturally-tailored interventions to prevent HIV in OHW.

In the course of our research, we found that the women perceived a lack of HIV prevention messages tailored to OHW; they thought that most education messages and campaigns were directed toward young people. Perhaps the perception that older women do not have sex has made them invisible in HIV prevention campaigns. Therefore, there is a lack of HIV knowledge and HIV risk perception in OHW resulting in high-risk sexual behaviors. Additionally, the increase in sexual activity among older men due to availability and accessibility of erectile dysfunction drugs and penis pumps has increased the HIV risk in OHW.

According to Bandura's theory (1995), behavioral change is initiated through knowledge. Knowledge of HIV prevention is the first step toward HIV prevention. Studies within the Hispanic community have shown that HIV education remains an important strategy for decreasing HIV risk (Cianelli et al., 2012; Rodríguez et. al., 2011).

Age-specific and culturally sensitive HIV prevention efforts need to be developed for OHW. Such efforts would address the biological changes that OHW experience (e.g., vaginal dryness) and the reality that OHW continue to struggle with cultural issues (e.g., machismo, marianismo) that increase the risk of acquiring HIV. Negotiating safer sex with partners has been considered difficult for OHW because they lack strong communication skills and they have not developed self-efficacy for safer sex practices (e.g., condom use; Jacobs & Thomlison, 2009).

Furthermore, the OHW in our study were reluctant to share experiences related to IPV. We can infer a reflection of the idea shared within Hispanic communities that IPV is part of “couple life” or “couple privacy” and is not something to be discussed in a group setting or with people outside the family. Other researchers (Bonomi et al., 2007; Zink et al., 2004) have noted that older women may be reluctant to disclose IPV to their health care providers. In addition, IPV denial in the focus groups can be validated by the finding that in the quantitative component of this study, women reported a high prevalence of IPV (62%) when they were individually interviewed using a structured questionnaire (Villegas et al., in press).

Limitations

This study targeted a subgroup of OHW who resided in South Florida; therefore, findings cannot be generalized to all Hispanic women who live in the state of Florida or in the United States. It is possible that factors other than the themes included in the focus group interviews that are specific to the OHW community could have also influenced HIV risk. While focus groups offered an appropriate setting for collecting data, group interviews may have been considered by OHW to be too public to discuss such sensitive issues.

Conclusions

Gender roles (e.g., machismo, marianismo) that are part of Hispanic culture have been associated with IPV (Cianelli et al., 2008; Moracco, Hilton, Hodges, & Frasier, 2005; Mouton, 2003). In a study conducted by Cianelli and colleagues (2008), IPV was justified by women as an expression of machismo characterized by domination, control, and pressures exerted by male partners that increased the risk of acquiring HIV (Jacobs & Thomlison, 2009). Unfortunately, few publications have discussed IPV among OHW to increase awareness and prevent IPV in this population.

Findings from our study provide a starting point to motivate the scientific community to conduct further research with OHW to investigate IPV and HIV risk. Interventions designed to prevent HIV should take into account that IPV will inhibit women from use of health care resources and potentially interfere with the receipt of standard HIV prevention programs (Kim, Peragallo, & DeForge, 2006; Miner, Ferrer, Cianelli, Bernales, & Cabieses, 2011). Findings from our study can provide valuable knowledge that will contribute to the development of prevention strategies to facilitate HIV awareness and prevention in the OHW population.

Clinical Considerations.

Nurses and other health care providers need to recognize that older Hispanic women (OHW) are sexually active and may be at risk for HIV infection.

Nurses and other health care providers need to recognize that OHW may not becomfortable disclosing interpersonal violence (IPV) to people outside their family units.With consideration of Latino cultural context, nurses and other health care providers needto develop new strategies to ensure that OHW are supported in the disclosure of IPV.

Nurses and other health care providers play an important role in educating OHW about IPVand HIV prevention. It is essential to develop or adapt age and culturally tailoredinterventions to prevent IPV and HIV in OHW.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P60MD002266.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rosina Cianelli, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA.

Natalia Villegas, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA.

Sarah Lawson, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA.

Lilian Ferrer, Escuela de Enfermería, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile.

Lorena Kaelber, College of Health Sciences Nursing Division Barry University and Health Sciences Nursing, Broward College, Miami, FL, USA.

Nilda Peragallo, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA.

Alexandra Yaya, Open Arms Community Center, Miami, FL, USA.

References

- Auerbach J. HIV/AIDS and aging: Interventions for older adults. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33(2):S57–S58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, editor. Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulaurier R, Craig S, De La Rosa M. Older Latina women and HIV/AIDS: An examination of sexuality and culture as they relate to risk and protective factors. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2009;52(1):48–63. doi: 10.1080/01634370802561950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A, Anderson A, Reid R, Carrell D, Fishman P, Rivara F, Thompson R. Intimate partner violence in older women. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(1):34–41. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas. 2007;2005 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2005report/ [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report. 2009;2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/pdf/2009SurveillanceReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cianelli R, Ferrer L, Norr F, Miner S, Peragallo N, McElmurry B, et al. De lo Cruz R. Mano a Mano Mujer: An effective HIV prevention intervention for Chilean women. Health Care for Women International. 2012;33:321–341. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.655388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianelli R, Ferrer L, McElmurry B. Issues on HIV prevention among low-income Chilean women: Machismo, marianismo, and HIV misconceptions. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2008;10(3):297–306. doi: 10.1080/13691050701861439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby W. What about focus group interaction data? Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:832–840. doi: 10.1177/1049732304273916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Health. HIV/AIDS among those age 50 and over. 2010a Retrieved from http://www.doh.state.fl.us/disease_ctrl/aids/updates/facts/10Facts/2010_50plus_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

- Florida Department of Health. Florida annual report 2010 acquired immune deficiency syndrome/human immunodeficiency virus. 2010b Retrieved from http://www.doh.state.fl.us/Disease_ctrl/aids/trends/epiprof/HIVAIDS_annual_morbidity_2010_cover.pdf.

- Florida Department Health. HIV/AIDS among those age 50 and over (Florida) 2011 Retrieved from http://www.doh.state.fl.us/disease_ctrl/aids/updates/facts/…/50plus2010.pdf.

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RJ, Thomlison B. Self-silencing and age as risk factors for sexually acquired HIV in midlife and older women. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21(1):102–128. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SD, Patsdaughter CA, Martinez Cardenas VM. Lessons from the Viagra study: Methodological challenges in recruitment of older and minority heterosexual men for research on sexual practices and risk behaviors. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2011;22:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Peragallo N, DeForge B. Predictors of participation in an HIV risk reduction intervention for socially deprived Latino women: A cross sectional cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43(5):527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganà L, Maciel M. Sexual desire among Mexican-American older women: A qualitative study. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2010;12(6):705–719. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.482673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O'Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(8):762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack KA, Ory MG. AIDS and older Americans at the end of the twentieth century. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33:S68–S75. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture and empowerment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14:186–192. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner S, Ferrer L, Cianelli R, Bernales M, Cabieses B. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk behaviors among socially disadvantaged Chilean women. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(4):1–5. doi: 10.1177/1077801211404189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moracco KE, Hilton A, Hodges KG, Frasier PY. Knowledge and attitudes about intimate partner violence among immigrant Latinos in rural North Carolina baseline information and implications for outreach. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:337–352. doi: 10.1177/1077801204273296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton CP. Intimate partner violence and health status among older women. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:1465–1477. doi: 10.1177/1077801203259238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton CP, Rodabough RJ, Rovi SDL, Hunt JL, Talamantes MA, Brzyskie R, et al. Burge SK. Prevalence and 3- year incidence of domestic violence in postmenopausal women. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:605–612. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.4.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neundorfer M, Harris P, Britton P, Lynch D. HIV-risk factors for midlife and older women. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):617–625. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Research on Women's Health. The agenda for research on women's health for the 21st century. 1999 Retrieved from http://orwhpubrequest.od.nih.gov/

- Peragallo N, Deforge B, O'Campo P, Lee S, Kim Y, Cianelli R, Ferrer L. A randomized clinical trial of an HIV-risk-reduction intervention among low-income Latina women. Nursing Research. 2005;54:108–118. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. HIV/AIDS and older adults in the United States. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/pdf09/TodaysResearchAging18.pdf.

- Rodríquez NV, Ferrer LM, Acosta RC, Miner S, Campos L, Peragallo N. Conocimientos y autoeficacia asociados a VIH y SIDA en mujeres Chilenas [Knowledge and self efficacy of HIV and AIDS in Chilean women] Investigación y Educación En Enfermería. 2011;2:212–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savasta A. HIV: Associated transmission risks in older adults. An integrative review of the literature. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2004;15:50–59. doi: 10.1177/1055329003252051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Stoller N. Introduction: Feminist strategies of empowerment. In: Schneider B, Stoller N, editors. Women resisting AIDS: Feminist strategies of empowerment. 1st. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University; 1995. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Shibusawa T. Intimate partner violence among mid-life and older women: A descriptive analysis of women seeking medical services. Health and Social Work. 2008;33(1):33–41. doi: 10.1093/hsw/33.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Shibusawa T. Predictors of condom use and HIV testing among midlife and older women seeking medical services. Journal of Aging Health. 2007;19:705–719. doi: 10.1177/0898264307301173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez J. HIV/AIDS and Latinas at greater risk: Latinas are nearly four times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to be infected. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-05-2011/hiv-aids-latinas.html.

- Van Eik H, Baum F. Evaluating health system change using focus groups and a developing discussion paper to compile the voices from the field. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:281–286. doi: 10.1177/1049732302239605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas N, Cianelli R, Ferrer L, Kaelber L, Peragallo N, Yaya A. Factores de riesgo para la adquisición de VIH en mujeres hispanas de 50 años y más residentes en el sur de la Florida [Risk factors for HIV acquisition among Hispanic women 50 years and older living in South Florida] Revista Horizonte de Enfermería in press. [Google Scholar]

- White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf.

- Zink T, Jacobson CJ, Regan S, Pabst S. Hidden victims: The healthcare needs and experiences of older women in abusive relationships. Journal of Women's Health. 2004;13:898–908. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]