Abstract

Since the introduction of H1N1 influenza vaccine in the wake of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, many serious and non-serious vaccine-related adverse events have been reported. The vaccination could induce pain, erythema, tenderness, and induration on injected areas. These symptoms usually disappear in a few days after the vaccination. In this case, we observed a 26-year-old woman with multiple erythematous scaly macules scattered on the extremities and trunk. She was injected with an inactivated split-virus influenza A/H1N1 vaccine without adjuvant (Greenflu-S®, Green Corp.) on her left deltoid area 10 days earlier. The first lesion appeared on the injection site three days after the vaccination, and the following lesions spread to the trunk and extremities after a few days. Histopathological examinations showed neutrophilic collections within the parakeratotic cornified layer, moderate acanthosis, diminished granular layer, elongation and edema of the dermal papillae, and dilated capillaries. The lesions were successfully treated with topical steroids and ultraviolet B phototherapy within three weeks, and there was no relapse for the following fourteen months. We assumed that pandemic vaccination was an important trigger for the onset of guttate psoriasis in this case.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Vaccination

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis, which is one of the most common inflammatory skin disorders, is characterized by the self-perpetuating activation of autoimmune T cells. Infection is an important trigger for both the onset and exacerbations of psoriasis. However, there are only a few reports in the literature describing the new onset of psoriasis following the administration of vaccine1-6. The pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccine was widely used in Korea to fight the influenza pandemics in 2009. However, there have been a number of cases reported on the adverse events, including, but not limited to, the pain, erythema, tenderness, and induration on the injected areas7. These reports also indicated that these events were usually resolved within a few days after the vaccination.

In this study, a 26-year-old woman developed guttate psoriasis initially on the vaccination site three days after the injection of an inactivated split-virus influenza A/H1N1 vaccine (Greenflu-S®; Green Cross Corp., Yongin, Korea).

CASE REPORT

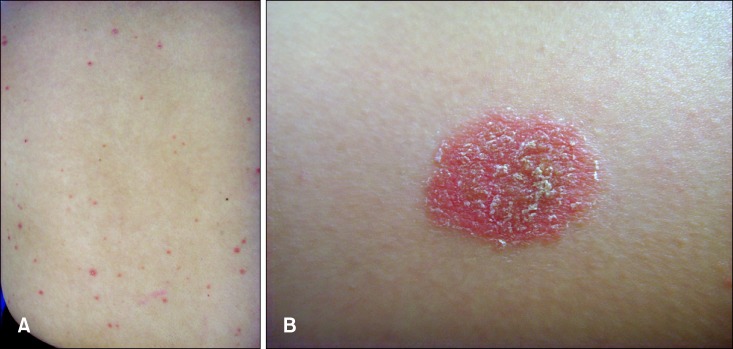

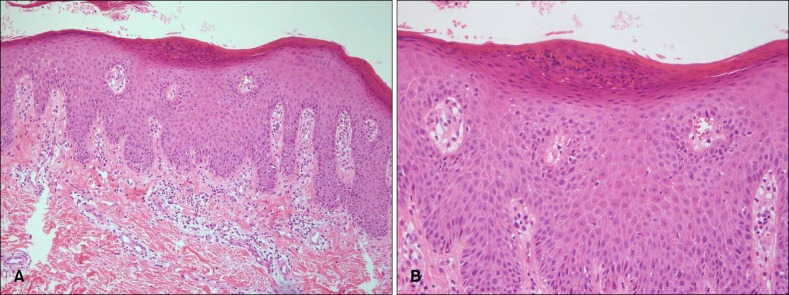

A 26-year-old Korean female was presented with guttate psoriasis-like lesions of multiple erythematous scaly macules scattered on her extremities and trunk (Fig. 1A). She was injected with an inactivated split-virus influenza A/H1N1 vaccine without adjuvant (Greenflu-S®) on her left deltoid area ten days before the visit to our department. The first lesion appeared on the injection site three days after the vaccination, and its size slowly increased (Fig. 1B). After a few days, multiple small scaly macules developed on the trunk and extremities. On the lesion on her back, an Auspitz sign was observed when silvery scales were removed. She suffered appendicitis four months before the vaccination and had no history of any other inflammatory disorders. There was no personal or family history of psoriasis. Routine laboratory investigation results were within the normal range of limits except for antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titer, which elevated to 773 IU/ml (normal: <200 IU/ml). However, there was no definite history of streptococcal infection, such as pharyngitis. Histopathological examination showed neutrophilic collections within the parakeratotic cornified layer, moderate acanthosis, diminished granular layer, elongation and edema of the dermal papillae, and dilated capillaries (Fig. 2). The lesions were successfully treated with topical steroids and ultraviolet B phototherapy within three weeks. And for the following fourteen months, there was no relapse.

Fig. 1.

(A) Multiple erythematous small scaly macules on trunk. (B) Larger lesion at the site of vaccination.

Fig. 2.

(A) Skin biopsy specimen showed parakeratosis, moderate acanthosis and rete ridge elongation in epidermis and perivascular infiltration of inflammatory cells in upper dermis (H&E, ×100). (B) Neutrophililc collection within the parakeratotic cornified layer, Munro's microabscess (H&E, ×200).

DISCUSSION

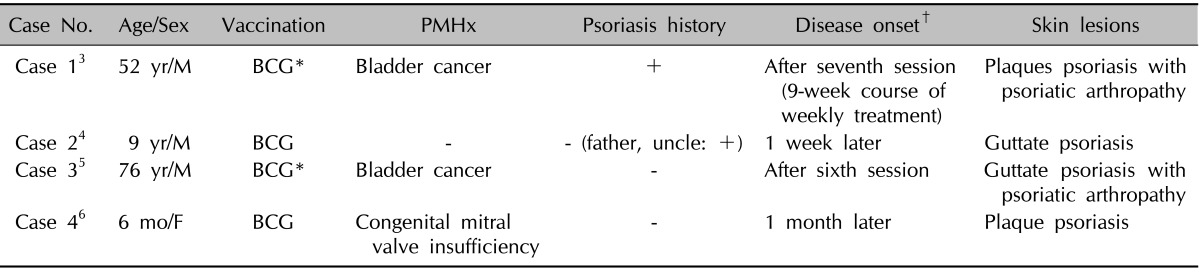

Infection is an important trigger for both the onset and exacerbations of psoriasis. However, there are only a few reports in the literature describing the new onset of psoriasis following vaccination. The onset of guttate psoriasis is developed at the site of vaccination against smallpox and influenza, as well as with diphtheria and antistreptococcal sera which was reported in 19551. BCG vaccination has also been reported to cause guttate psoriasis-like eruptions and psoriatic arthropathy1,3-5. The reported cases are summarized in Table 1. However, psoriasis followed by influenza vaccination is rare although some cases of pityriasis rosea developed after H1N1 vaccination or concurrent influenza A (H1N1) infection were reported8-10.

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of psoriasis following vaccination

PMHx: past medical history, M: male, F: female, BCG: bacillus Calmette-Guerin, +: present, -: absent. *BCG immunotherapy for bladder cancer. †Interval between the use of vaccination and the appearance of psoriasis lesions.

The aetiological relationship between psoriasis and vaccination is still uncertain. Researchers hypothesizes that the development of psoriasis following BCG vaccination is caused by the induction of a T helper type 1 (Th1) predominant response. The amplified cytokines include interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and interleukins (ILs)-1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 1811. This response may form the basis of the development for psoriasis; a Th1-dominant disease in genetically predisposes individuals, where IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF and IL-6 promote epidermal proliferation, and IL-8 stimulates neutrophil ingression12.

In South Korea, a monovalent, unconjugated, inactivated, split-virus influenza A (H1N1) vaccine, was widely used in 2009 during the pandemic breakout of the H1N1 influenza. The vaccine contained split-virus products of 15 µg of hemagglutinin antigen per 0.5 ml prefilled syringe. The most common local adverse events from influenza vaccination were pain, redness, tenderness, and swelling around the injected area. These issues were resolved in a few days after vaccination in most cases7.

Currently, it is thought that the pathological mechanisms responsible for psoriasis are related to IL-22, Th17 cell-derived cytokine, which is a key player in the development of characteristic epidermal changes of psoriasis13. In the study of influenza vaccine in a murine model, the cytokine profile demonstrated a robust cellular immune response with enhanced Th1 and Th17 immunity that provided balanced immunity against both intracellular and extracellular forms of the virus14.

There were other factors we considered when diagnosing that the psoriasis in this case was triggered by influenza vaccination.The patient showed an elevated level of ASO titer, which indicated that there was a previous streptococcal infection. However, the exacerbation of psoriasis following streptococcal infections usually occurs within two to three weeks15. In addition, ASO antibody can be found in the blood within weeks or months after the streptococcal infection has cured16. So, it was also hard to conclude that streptococcal infection, not the vaccine, was the real cause of psoriasis in this case when there was no definite history of recent infections. Therefore, the first lesion developed on the injection areawas suspected as a Koebner phenomenon, but the lesions spread on to the other sites of the body could not be explained by Koebnerization. One possible explanation is that H1N1 vaccination acted as a co-stimulant in carriers or patients with subclinical infections rather than the sole cause of guttate psoriasis. However, we could not find any similar reports to our case.

In conclusion, although the patient in this case showed an elevated level of ASO titer, we believed that the role of the H1N1 vaccination in the development of guttate psoriasis should not be ruled out.

References

- 1.Raaschou-Nielsen W. Psoriasis vaccinalis; report of two cases, one following B.C.G. vaccination and one following vaccination against influenza. Acta Derm Venereol. 1955;35:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogdaszewska-Czabanowska, Brzewski M. Psoriasis vaccinalis (post-BCG) Przegl Dermatol. 1973;60:497–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Queiro R, Ballina J, Weruaga A, Fernández JA, Riestra JL, Torre JC, et al. Psoriatic arthropathy after BCG immunotherapy for bladder carcinoma. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:1097. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.11.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koca R, Altinyazar HC, Numanoğlu G, Unalacak M. Guttate psoriasis-like lesions following BCG vaccination. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50:178–179. doi: 10.1093/tropej/50.3.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudelzak J, Curtis AR, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL., Jr New-onset psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a patient treated with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takayama K, Satoh T, Hayashi M, Yokozeki H. Psoriatic skin lesions induced by BCG vaccination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:621–622. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh CE, Lee J, Kang JH, Hong YJ, Kim YK, Cheong HJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated split-virus influenza A/H1N1 vaccine in healthy children from 6 months to <18 years of age: a prospective, open-label, multi-center trial. Vaccine. 2010;28:5857–5863. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of Pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon NH, Kim JE, Cho BK, Park HJ. A novel influenza a (H1N1) virus as a possible cause of pityriasis rosea? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:368–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JF, Chiang CP, Chen YF, Wang WM. Pityriasis rosea following influenza (H1N1) vaccination. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011;74:280–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Böhle A, Brandau S. Immune mechanisms in bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer. Philadelphia: Elsevier Sauders; 2012. pp. 135–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. pp. 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, Kasman I, Eastham-Anderson J, Wu J, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamouda T, Chepurnov A, Mank N, Knowlton J, Chepurnova T, Myc A, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and stability of a novel intranasal nanoemulsion-adjuvanted influenza vaccine in a murine model. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:585–594. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.7.11818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Telfer NR, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, Colman G. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MedlinePlus. Trusted Health Information for you [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); Antistreptolysin O titer; [updated 2011 Aug 29]. [cited 2011 Sep 1]. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003522.htm. [Google Scholar]