Abstract

Currently, there are 1.0 million annual hospital discharges for acute heart failure (AHF). The total cost of heart failure (HF) care in the United States is projected to increase to $53 billion in 2030, with the majority of costs (80 %) related to AHF hospitalizations. Approximately 50 % of AHF episodes occur in patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). There is a dearth of evidence-based guidelines for the management of AHF in HFpEF patients. Here, we briefly review the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of AHF patients with HFpEF.

Keywords: Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

Introduction

An estimated 5.8 million Americans have heart failure (HF), and this is expected to increase to 8.5 million by 2030 [1••]. Acute HF (AHF) is defined as a gradual or rapid change in HF symptoms resulting in a need for urgent therapy and can occur in patients without previously recognized HF, in patients with chronic HF (“acute on chronic HF”), and in patients with advanced end-stage (Stage D) chronic HF [2, 3]. Currently, there are 1.0 million annual hospital discharges for HF [4]. The total cost of HF care in the United States is currently estimated at $21 billion and is projected to increase to $53 billion in 2030, with the majority of costs (80 %) related to AHF hospitalizations [1••].

Observational and registry studies, as well as randomized clinical trials, in AHF have established that a substantial portion of patients with AHF have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (Table 1). Here, we review the characteristics of these patients in contrast to AHF patients with reduced EF (HFrEF) and discuss whether unique AHF therapies are needed in AHF patients with HFpEF.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in acute heart failure (AHF) with preserved ejection fraction (pEF)

| Reference | Owan TE, NEJM, 2006 |

Bhatia RS, NEJM, 2006 |

Yancy CW, JACC, 2006 |

Fonarow G, JACC, 2007 |

Chinali M, CAD, 2010 |

Steinberg BA, Circ, 2012 |

Bishu, AHJ, 2012 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study name | Mayo AHF | Canadian AHF | ADHERE | OPTIMIZE HF | Worcester AHF | GET WITH GUIDELINES |

DOSE TRIAL |

|||||||

| Type | Retrospective | Retrospective | Registry | Registry | Retrospective | Registry | RCT | |||||||

| n | 6,076 | 2,802 | 100,000 | 41,267 | 1,426 | 110,621 | 308 | |||||||

| pEF | rEF | pEF | rEF | pEF | rEF | pEF | rEF | pEF | rEF | pEF | rEF | pEF | rEF | |

| HF type | 47 % | 53 % | 44 % | 56 % | 50 % | 50 % | 24 % | 76 % | 43 % | 57 % | 36 % | 64 % | 27 % | 73 % |

| Age (years) | 74 | 72 | 75 | 72 | 74 | 70 | 76 | 70 | 76 | 74 | 78 | 70 | 74 | 66 |

| Female | 56 % | 35 % | 66 % | 37 % | 62 % | 40 % | 68 % | 38 % | 68 % | 47 % | 63 % | 36 % | 42 % | 20 % |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 | 29 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 28 | 27 | 29 | 27 | 34 | 31 |

| Hypertension | 63 % | 48 % | 55 % | 49 % | 77 % | 69 % | 77 % | 66 % | 69 % | 64 % | 80 % | 72 % | 84 % | 80 % |

| Coronary disease | 53 % | 64 % | 36 % | 49 % | 50 % | 59 % | 34 % | 54 % | 44 % | 52 % | 46 % | 63 % | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 41 % | 29 % | 32 % | 24 % | 21 % | 17 % | 32 % | 28 % | – | – | 34 % | 28 % | 69 % | 48 % |

| Diabetes | 33 % | 34 % | 32 % | 40 % | 40 % | 45 % | 41 % | 39 % | 34 % | 40 % | 46 % | 40 % | 47 % | 53 % |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.6 | 1.6 | – | – | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.46 | 1.66 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Serum Hgb (g/dl) | 12 | 13 | – | – | – | 11.8 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 12.4 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 11.9 | |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | – | – | 156 | 146 | 153 | 139 | 150 | 135 | 152 | 145 | 145 | 131 | 120 | 113 |

| Rales | – | – | 84 % | 84 % | 69 % | 67 % | 63 % | 63 % | – | – | – | – | 69 % | 56 % |

| Peripheral edema | – | – | 66 % | 57 % | 69 % | 63 % | 68 % | 62 % | 73 % | 70 % | – | – | 99 % | 94 % |

Note. BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; Hgb, hemoglobin

Unique Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of AHF Patients with HFpEF

The demographic features and clinical characteristics of AHF patients with preserved or reduced EF have been reported in observational studies and registries and, to a more limited extent, in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) conducted in AHF.

The prevalence of HFpEF in AHF cohorts varies but, in general, is 40 %–50 %, depending on the era, study setting, and EF value used to define HFpEF (Table 1) [5••, 6–10]. Importantly, among 6,076 consecutive AHF admissions at Mayo Clinic Hospitals from 1987 to 2001, the prevalence of HFpEF among AHF patients increased over time, increasing from 38 % in the first 5 years to 54 % in the final 5 years of the study. The prevalence of HFpEF among AHF patients was higher in community (55 %) than in referral (45 %) patients. While survival after admission for AHF improved over the study period in AHF patients with HFrEF, no such improvement was observed in AHF patients with HFpEF

As compared with AHF patients with HFrEF, those with HFpEF are older, more obese, and more likely to be female (Table 1). The prevalence of hypertension, atrial fibrillation (AF), and anemia is higher in HFpEF than in HFrEF, while the prevalence of renal dysfunction and diabetes is similar. Coronary disease is less common in patients with HFpEF. In general, blood pressure is higher in HFpEF than in HFrEF, but signs and symptoms of volume overload are similar (Table 1).

Most RCTs of AHF therapies have restricted enrollment to patients with HFrEF. However, RCTs of vasodilators (ASCEND, nesiritide; RELAX, serelaxin), ultrafiltration (UNLOAD and CARRESS-HF), and diuretic dosing strategies (DOSE) have not restricted enrollment according to EF, and in these studies, 20 %–30 % of AHF patients had HFpEF (variably defined as AHF with EF >40 % or >50 %). Only the diuretic dosing study (DOSE) [11••] presented characteristics of patients according to EF [12], and differences between AHF patients with HFpEF or HFrEF in DOSE were consistent with differences observed in observational and registry studies (Table 1). It is well recognized that patients enrolled in RCTs differ significantly from those in observational studies or registries, and one of these differences in RCTs of AHF patients is a lower prevalence of HFpEF [13].

Biomarkers in AHF Patients with HFpEF

Biomarkers are often measured in AHF studies and provide pathophysiologic, diagnostic, and prognostic information. Circulating levels of natriuretic peptides such as B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or the N-terminal fragment of pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) are used to exclude the diagnosis of HF in acutely dyspneic patients, and in AHF patients, BNP levels correspond with congestion severity and prognosis [14, 15]. However, multiple studies have shown that BNP levels are lower in AHF patients with HFpEF than in those with HFrEF despite similar HF severity [12, 16, 17]. HFpEF patients are, on average, more obese than HFrEF patients, and even in normal persons, obesity is associated with lower BNP levels [5••, 6–10, 18]. Ventricular wall stress is the stimulus for BNP production and is directly related to intraventricular pressures and left-ventricular (LV) radius and inversely related to LV wall thickness. Since HFpEF patients have smaller LV diameter and thicker walls than do HFrEF patients, their wall stress and, thus, their BNP levels are lower [19•].

Fewer studies have compared other biomarkers in AHF patients with preserved or reduced EF. In the DOSE trial [12], AHF patients with HFpEF had lower NT-proBNP levels than did HFrEF patients, consistent with previous studies. However, biomarkers reflecting renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) activation (plasma renin activity and serum aldosterone levels) were similarly elevated in HFpEF and HFrEF, despite less use of RAAS inhibitors in HFpEF, suggesting, that at least in AHF, there is similar activation of the RAAS system in both HF types. Uric acid, a marker of inflammation, and NT-procollagen III, a marker of increased collagen turnover, were elevated above normal range and to the same extent in both HFpEF and HFrEF. In a large multicenter AHF registry, patients with HFpEF had lower troponin than did patients with HFrEF, suggesting less ongoing myocardial necrosis [17].

Outcomes in AHF Patients with HFpEF

In observational and registry studies, short- and long-term mortality following AHF hospitalization for AHF is slightly better for HFpEF than for HFrEF [5••, 7–9, 17]. In a Canadian study of 2,802 patients with incident AHF, 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were not different between HFpEF and HFrEF [7]. In the Mayo Clinic study, survival rates (median follow-up 10 years) were marginally better in HFpEF, with mortality rates of 29 % and 32 % at 1 year and 65 % and 68 % at 5 years for HFpEF and HFrEF, respectively [5••]. In the ADHERE AHF registry, mortality for patients with HFpEF during hospitalization was lower (2.8 % vs. 3.9 % in HFrEF); ICU admission rate was lower (19 % vs. 25 % for HFrEF), while length of hospital stay was similar (4.9 vs. 5.0 days for HFrEF) [8]. In the OPTIMIZE-HF registry, in-hospital mortality was lower among HFpEF patients (2.9 % vs. 3.9 % for HFrEF); postdischarge mortality up to 3 months (9.8 % vs. 9.5 %) and rehospitalization (30 % vs. 31 %) rates were similar with HFrEF [9]. In the Get With the Guidelines AHF Registry, in-hospital mortality was similar in patients with HFpEF (2.5 %) and HFrEF (2.7 %) [17].

Pathophysiology of HFpEF

The pathophysiologic features of HFpEF include resting diastolic dysfunction and impaired diastolic reserve, subtle resting contractile dysfunction (despite normal EF) and impaired systolic reserve, increased ventricular systolic stiffness, increased vascular stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, impaired vasodilatory reserve, chronotropic incompetence, and neurohumoral activation [20, 21]. Patients with HF develop pulmonary hypertension (PH) due to chronic pulmonary venous and variable reactive pulmonary arterial hypertension, and among HF patients, PH is as common in HFpEF as in HFrEF [22, 23], and RV dysfunction is present in at least 25 % of patients with HFpEF [24]. As in HFrEF, both intrinsic kidney disease and HF-related impairment in kidney function play prominent roles in HFpEF pathophysiology [25].

Pathophysiology of AHF

As was previously reviewed, the pathophysiology of AHF is diverse and suboptimally characterized [2, 3], but the pathophysiologic features include congestion (elevated right and left atrial pressures), impaired myocardial function (decreased cardiac output and hypotension), and increased load (elevated blood pressure or systemic vascular resistance). Ongoing myocardial injury is thought to play a role in AHF pathophysiology as troponin levels are increased in the absence of critical epicardial coronary disease, but the mechanism of myocardial necrosis in HF is not well characterized. Activation of the RAAS is present in AHF and contributes to vasoconstriction, renal dysfunction, and, potentially, myocardial necrosis. Activation of inflammation and oxidative stress pathways may be enhanced in AHF. Intrinsic kidney disease and renal dysfunction due to acute and chronic hypoperfusion or venous congestion related to HF play a key role in the pathophysiology of AHF. Arrhythmias are recognized precipitants of AHF and, particularly, recent onset AF with tachycardia, heart rate irregularity, and loss of filling due to atrial contraction. Comorbidities variably influence the pathophysiology of AHF.

Targets for Therapy in AHF Patients with HFpEF

While many of the therapeutic approaches to AHF are applied without regard to EF, the demographic features, clinical characteristics, and pathophysiologic mechanisms unique to AHF patients with HFpEF suggest that response to some standard AHF therapies may differ in HFpEF and that unique therapies for AHF patients with HFpEF may be needed.

Congestion Relief in HFpEF Patients with AHF

In the ADHERE AHF registry, as compared with patients with HFrEF, patients with HFpEF were slightly more likely to receive intravenous diuretic therapy during the AHF hospitalization but had similar weight loss and a similar prevalence of symptom relief at discharge [8]. In the OPTIMIZE-HF registry, HFpEF patients had slightly less weight loss but slightly more symptomatic improvement than did AHF patients with HFrEF [9].

When a patient with congestion fails to respond, the dose of loop diuretic is increased, or a thiazide is added [26, 27]. When these measures fail to relieve congestion, ultrafiltration or other renal replacement approaches may be considered. The two larger RCT trials of ultrafiltration in AHF (UNLOAD and CARRESS-HF) included AHF patients with HFpEF but did not report on potential differences in response to ultrafiltration in HFpEF versus HFrEF [28, 29]. In a single-center cohort study, Jeffries et al. compared response to ultrafiltration in AHF patients with HFpEF and HFrEF and found no difference in weight loss, electrolyte perturbations, or in-hospital mortality with ultrafiltration in the two types of HF [30].

Thus, the limited data available suggest that HFpEF patients respond to standard decongestive therapies in a manner similar to AHF patients with HFrEF.

Vasodilator Therapy in HFpEF Patients with AHF

In AHF, increased vascular and LV stiffness may exacerbate acute pulmonary congestion by redistributing fluid to the more compliant pulmonary venous bed [31]. Systemic hypertension is common in HFpEF patients with AHF and may predispose to such redistribution and to load-induced worsening of systolic and diastolic function and mitral regurgitation. Thus, as outlined in current guidelines [26], control of elevated blood pressure is an important treatment goal in the treatment of HFpEF (and HFrEF) patients presenting with AHF.

In general, HFpEF patients with AHF have higher systolic blood pressure than do HFrEF patients (Table 1). The prevalence of marked systolic hypertension in AHF varies by care setting and, in some settings, is more common and more prevalent in AHF with HFpEF [32•]. While parental vasodilator therapy is an important treatment strategy in AHF patients with elevated blood pressure, the unique pathophysiology present in HFpEF warrants consideration when initiating and monitoring vasodilator therapy.

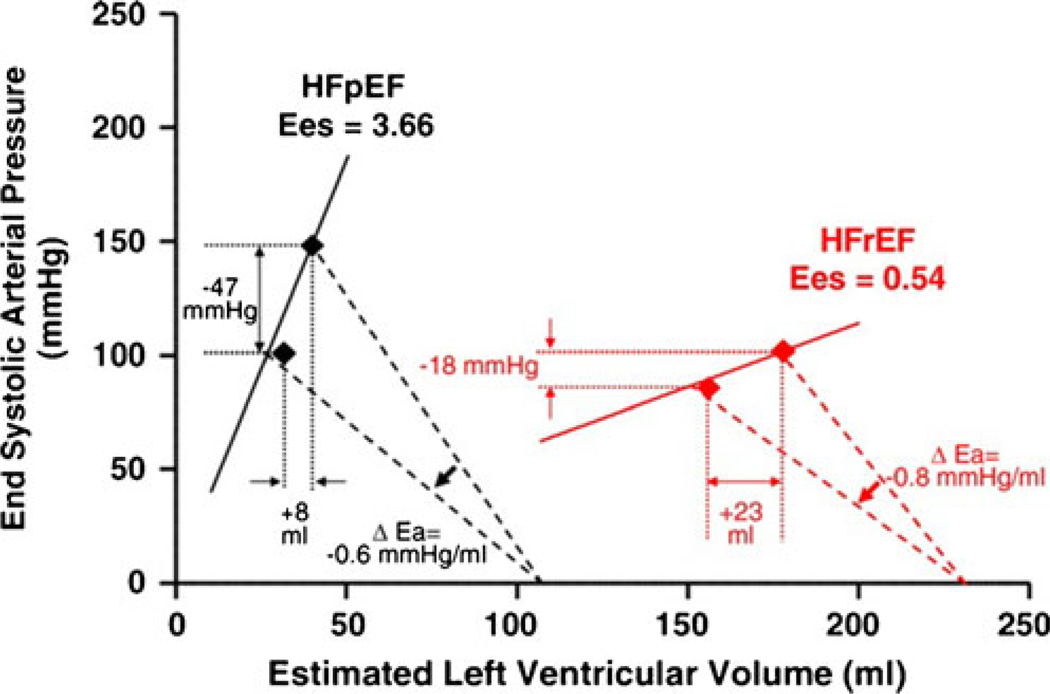

Schwartzenberg et al. studied HF patients referred for right-heart catheterization and noted a distinctly different response to acute intravenous vasodilator therapy in HFpEF and HFrEF patients (Fig. 1) [32•]. HFpEF patients had higher blood pressure and stroke volume, while pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and pulmonary artery systolic pressure were similar to those in the HFrEF patients. In response to a similar dose of sodium nitroprusside and similar reduction in total arterial load (arterial elastance, Ea), the drop in systemic arterial pressure was 2.6-fold greater in HFpEF, while improvement in stroke volume and cardiac output was ≈60 % lower than in HFrEF, and HFpEF patients were 4 times more likely to experience a reduction in cardiac output with nitroprusside, despite similar reduction in PCWP. The differential hemodynamic response to acute intravenous vasodilator therapy in HFpEF was due to the higher LV end-systolic elastance (stiffness, Ees). These data underscore the fundamental differences in pathophysiology in HFpEF versus HFrEF patients and that, while reduction of elevated systolic blood pressure is beneficial in AHF [33, 34], the improvements in forward flow with vasodilator therapy well known to occur in HFrEF may not be realized in AHF patients with HFpEF. In the ADHERE and OPTIMIZE-HF registries, HFrEF patients were more likely to receive intravenous vasodilator therapy, as compared with HFpEF patients, underscoring the recognized benefits of vasodilator therapy in HFrEF, where enhanced cardiac output may occur in response to vasodilators even in the absence of hypertension [8, 9].

Fig. 1.

Unique pathophysiology in HFpEF determines hemodynamic response to acute vasodilator therapy: Grouped data from pressure volume analysis in patients with heart failure (HF) with preserved (HFpEF) or reduced (HFrEF) ejection fraction. Patients with HFpEF have higher end systolic elastance (Ees), indicating greater left-ventricular systolic stiffness. Equivalent reduction in total arterial load (arterial elastance, Ea) was achieved with acute administration of nitrosprusside in the two forms of HF. In response to vasodilatation, HFpEF patients experienced greater reduction in arterial pressure but less increase in stroke volume. (Reprinted from Schwartzenberg S, Redfield MM, From AM, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Borlaug BA, Effects of Vasodilation in Heart Failure With Preserved or Reduced Ejection Fraction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012; 59(5):442–451. ©2012, with permission from Elsevier)

Few studies have examined the potential for differential response to vasodilator therapy in the two forms of HF. The large ASCEND trial tested the effect of the vasodilator nesiritide on symptom relief in AHF [35•]. Nesiritide marginally improved symptom relief without effect on renal function or clinical outcomes, and there was no differential response according to EF (<40 % and ≥40 %).

Relaxin is an endogenous peptide that modulates cardiovascular adaptation to pregnancy and is a potent vasodilator that may also have beneficial effects on renal function. The RELAX-AHF trial program tested recombinant human relaxin-2 (serelaxin) in AHF patients with normal or increased (>125 mmHg) systolic blood pressure and included patients with preserved EF (26 % of patients). Overall, relative to placebo, serelaxin improved dyspnea at 5, but not 2, days, had no effects on cardiovascular deaths or HF or renal failure hospitalizations at 180 days, reduced 180-day all-cause mortality, and had significant favorable effects on biomarkers reflective of congestion, renal function, hepatic function, and myocardial necrosis [36, 37]. Of the patients in RELAX-AHF, 45 % had EF >40 %, and data on the effect of treatment compared between HFpEF and HFrEF hopefully will be forthcoming.

Other novel vasodilators are being tested in AHF, including those targeting enhancement of cGMP, the second messenger for the vasoactive nitric oxide and natriuretic peptide systems. In animal in vivo studies and in human myocardial tissue, activation of cGMP targets (protein kinase G) acutely enhances diastolic distensibility independently of load effects, suggesting that cGMP-based vasodilators may have unique therapeutic effects in HFpEF [38, 39]. Enhancement of cGMP can be provided by ligand administration (NO donors or natriuretic peptides; see above), soluble or particulate guanylyl cyclase activators, or inhibition of cGMP degradation by phosphodiesterases. The soluble guanylate cyclase activator cinaciguat was proven vasoactive in AHF patients with HFrEF [40] but has not been tested in HFpEF patients with AHF. In ambulatory HFpEF patients, the phosphodiesterase-5A inhibitor sildenafil did not improve exercise tolerance or clinical status but had a minimal effect on plasma cGMP levels [41•]. Since HFpEF patients have lower natriuretic peptide levels and high levels of oxidative stress that may impair NO production and soluble guanylyl cyclase activity [42], different strategies may be needed to enhance cGMP in HFpEF. Studies of chronic natriuretic peptide or nitrate administration in HFpEF are ongoing or planned and may provide a means to enhance cGMP in HFpEF.

Myocardial Directed Therapy in HFpEF Patients with AHF

In HFrEF patients with AHF, when hemodynamic and end-organ function is deteriorating despite diuretics and vasodilators, inotropic therapy or mechanical circulatory support are considered. The only inotropic therapy tested in HFpEF was digoxin, where among ambulatory HFpEF patients, digoxin therapy was associated with a trend toward reduction in HF hospitalizations but an increase in acute coronary syndrome hospitalizations [43]. While beta agonists and cAMP targeted phosphodiesterase inhibitors enhance lusitropic as well as inotropic function, they have not been tested in HFpEF. As was noted above, cGMP-enhancing therapies have the potential for direct myocardial effects.

Thus, therapies that acutely and specifically enhance diastolic function in HFpEF are lacking.

Renal Targeted Therapy in AHF Patients with HFpEF

As was recently reviewed, numerous studies have confirmed the association of renal dysfunction with adverse short- and long-term outcomes in AHF, established that this association is equally potent in AHF patients with HFrEF or HFpEF, and provided insight into the complex pathophysiology of renal dysfunction in AHF [44, 45].

Given the renal vasoconstriction characteristic of AHF, other vasodilators with variable specificity for the renal vasculature have been or are being tested in AHF and include low-dose dopamine and low-dose nesiritide [46–48], as well as serelaxin as noted above. Unfortunately, there are few data in regard to differential effects of renal vasodilators in AHF due to HFpEF.

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is a recognized risk factor for AHF with preserved EF and is common (≈8 %) in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, with approximately 20 % of patients with RAS having bilateral RAS [49]. ACC guidelines recommend percutaneous revascularization for patients with RAS and recurrent episodes of AHF [50]. A high index of suspicion for RAS should be maintained in patients with HFpEF, particularly those with flash pulmonary edema, and renal artery Duplex scanning or imaging should be considered as specific therapy is available.

Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease in AHF Patients with HFpEF

Guidelines recommend treatment of ischemia in patients with HFpEF when ischemia is thought to contribute to cardiac dysfunction [26]. In the past, ischemia and load-induced systolic dysfunction were thought to contribute to the pathophysiology of AHF patients who present with hypertension and pulmonary edema but are later found to have preserved EF. It was speculated that if evaluated when hypertensive at the time of presentation, EF would be reduced, and wall motion abnormalities or mitral regurgitation might be common in these HFpEF patients. However, Ghandi et al. performed echocardiography during hypertensive pulmonary edema (emergency department) and later in the AHF hospitalization when blood pressure was controlled in a cohort of AHF patients. Most of these patients had normal EF at later assessment and would be considered to have HFpEF. This study found that EF and wall motion scores were similar at presentation and reassessment and that significant MR was uncommon [51••]. Importantly, in cohort study of patients with hypertensive pulmonary edema and coronary disease, revascularization did not reduce the incidence of repeated episodes of flash pulmonary edema [52].

While coronary artery disease and ischemia should be considered in HFpEF patients with AHF, determining when ischemia is playing a role in the pathophysiology of HFpEF is difficult, particularly in AHF, where troponin is commonly elevated in the absence of coronary artery disease [53] and may exceed thresholds utilized for the diagnosis of ACS in up to 20 % of AHF presentations [54]. Stress testing utilizing imaging may also have reduced specificity, since the EF response may be flat even in the absence of coronary disease [55].

If ischemia is documented in HFpEF patients, the decision to treat medically or with revascularization will be dictated by a number of factors, including the age and concomitant comorbidities present.

Atrial Fibrillation in AHF Patients with HFpEF

Among AHF patients, AF is more common in patients with HFpEF than in those with HFrEF (Table 1). In ambulatory HFpEF patients, those with AF are older and have worse systolic and diastolic function, more neurohumoral activation, and worse exercise tolerance [56]. The presence of AF among patients with chronic stable HF is a predictor of subsequent HF hospitalization in HFpEF [57].

Sleep Disordered Breathing in AHF Patients with HFpEF

HFpEF patients are, on average, more obese than HFrEF patients and have higher blood pressure and a higher prevalence of AF (Table 1). Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is more common in obese patients and in patients with HF and predisposes to hypertension and AF. Bitter et al. studied 244 consecutive patients with HFpEF without previous SDB diagnosis and found that 69.3 % had SDB with obstructive sleep apnea in 39.8 % and central sleep apnea in 29.5 % [58]. While continuous positive airway pressure did not improve outcomes in HFrEF [59], ongoing studies are evaluating adaptive servo ventilation devices in HF. These devices may better control apneic episodes and may impact outcomes in HF. If so, aggressive screening and therapy for SDB in AHF with HFpEF may be warranted.

Conclusion

AHF with preserved EF is characterized by unique clinical characteristics and pathophysiology. There is a dearth of evidence-based guidelines for the specific management of AHF in HFpEF. When appropriate, future AHF trials of agents not specifically targeting systolic dysfunction should include adequate numbers of HFpEF patients to allow determination of potential differential effects in HFpEF.

Acknowledgments

Margaret M. Redfield is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Thoratec, and Medtronic; has received royalties from Annexion; and has received payment for development of educational presentations from the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest Kalkidan Bishu declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1. Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the american heart association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–619. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. This analysis underscores the tremendous and growing burden of AHF on the health-care system.

- 2.Gheorghiade M, Zannad F, Sopko G, Klein L, Piña IL, Konstam MA, et al. Acute heart failure syndromes: current state and framework for future research. Circulation. 2005:3958–3968. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felker GM, Pang PS, Adams KF, Cleland JGF, Cotter G, Dickstein K, et al. Clinical trials of pharmacological therapies in acute heart failure syndromes: lessons learned and directions forward. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(2):314–325. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.893222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012 Dec 12; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. This study documented the increasing prevalence of HFpEF in AHF.

- 6.Chinali M, Joffe SW, Aurigemma GP, Makam R, Meyer TE, Goldberg RJ. Risk factors and comorbidities in a community-wide sample of patients hospitalized with acute systolic or diastolic heart failure: the Worcester Heart Failure Study. Coron Artery Dis. 2010;21(3):137–143. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328334eb46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, et al. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, De Marco T, Fonarow GC. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure with preserved systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(1):76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(8):768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweitzer NK, Lopatin M, Yancy CW, Mills RM, Stevenson LW. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized with Heart Failure and Normal Ejection Fraction (≥55%) Versus those with mildly reduced (40% to 55%) and moderately to severely reduced. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(8):1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, Redfield MM, Stevenson LW, Goldsmith SR, et al. Diuretic strategies in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):797–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005419. This study was one of the few to test the comparative effectiveness of diuretic administration strategies in AHF.

- 12.Bishu K, Deswal A, Chen HH, LeWinter MM, Lewis GD, Semigran MJ, et al. Biomarkers in acutely decompensated heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 2012;164(5):763–763. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezekowitz JA, Hu J, Delgado D, Hernandez AF, Kaul P, Leader R, et al. Acute heart failure: perspectives from a randomized trial and a simultaneous registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(6):735–741. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.968974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels LB, Maisel AS. Natriuretic peptides. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(25):2357–2368. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munagala VK, Burnett JC, Redfield MM. The natriuretic peptides in cardiovascular medicine. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2004;29(12):707–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonarow GC, Peacock WF, Phillips CO, Givertz MM, Lopatin M. ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Admission B-type natriuretic peptide levels and in-hospital mortality in acute decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(19):1943–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation. 2012;126(1):65–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.080770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EP, Wilson PWF, et al. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation. 2004;109(5):594–600. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112582.16683.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iwanaga Y, Nishi I, Furuichi S, Noguchi T, Sase K, Kihara Y, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide strongly reflects diastolic wall stress in patients with chronic heart failure: comparison between systolic and diastolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(4):742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.030. This study demonstrated the physiologic basis for lower natriuretic peptides in patients with HFpEF versus HFrEF.

- 20.Borlaug BA, Redfield MM. Diastolic and systolic heart failure are distinct phenotypes within the heart failure spectrum. Circulation. 2011;123(18):2006–2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.954388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borlaug BA, Kass DA. Mechanisms of diastolic dysfunction in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16(8):273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam CSP, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Borlaug BA, Enders FT, Redfield MM. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(13):1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bursi F, McNallan SM, Redfield MM, Nkomo VT, Lam CSP, Weston SA, et al. Pulmonary pressures and death in heart failure: a community study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(3):222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammed SF, Roger VL, Abouezzeddine OF, Redfield MM. Right ventricular systolic function in subjects with HFpEF: a community based study. Circulation. 2011 Jun 23;(Supplement 1):A17404. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heywood JT, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, Mathur VS, Wigneswaran JR, Wynne J, et al. High prevalence of renal dysfunction and its impact on outcome in 118,465 patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a report from the ADHERE database. J Card Fail. 2007;13(6):422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for themanagement of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Jun 5; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Channer KS, McLean KA, Lawson-Matthew P, Richardson M. Combination diuretic treatment in severe heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Br Heart J. 1994;71(2):146–150. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.2.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bart BA, Goldsmith SR, Lee KL, Givertz MM, O'Connor CM, Bull DA, et al. Ultrafiltration in decompensated heart failure with cardiorenal syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(24):2296–2304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costanzo MR, Saltzberg MT, Jessup M, Teerlink JR, Sobotka PA. Ultrafiltration Versus Intravenous Diuretics for Patients Hospitalized for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (UNLOAD) Investigators. Ultrafiltration is associated with fewer rehospitalizations than continuous diuretic infusion in patients with decompensated heart failure: results from UNLOAD. J Card Fail. 2010;16(4):277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jefferies JL, Bartone C, Menon S, Egnaczyk GF, O'Brien TM, Chung ES. Ultrafiltration in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: comparison with Systolic Heart Failure Patients. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2013 Jun 4; doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cotter G, Metra M, Milo-Cotter O, Dittrich HC, Gheorghiade M. Fluid overload in acute heart failure–re-distribution and other mechanisms beyond fluid accumulation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(2):165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwartzenberg S, Redfield MM, From AM, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Borlaug BA. Effects of vasodilation in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. JAC Elsevier Inc. 2012;59(5):442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.062. This study demonstrated that unique pathophysiology in HFpEF is associated with differential response to vasodilators.

- 33.Cotter G, Metzkor E, Kaluski E, Faigenberg Z, Miller R, Simovitz A, et al. Randomised trial of high-dose isosorbide dinitrate plus low-dose furosemide versus high-dose furosemide plus low-dose isosorbide dinitrate in severe pulmonary oedema. Lancet. 1998;351(9100):389–393. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012:1787–1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O'Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, Armstrong PW, Dickstein K, Hasselblad V, et al. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(1):32–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100171. This large multinational study demonstrated that vasoactive doses of nesiritide had minimal favorable effects on symptom relief in AHF and were not associated with worsening renal function or increased mortality.

- 36.Metra M, Cotter G, Davison BA, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, et al. Effect of serelaxin on cardiac, renal, and hepatic biomarkers in the Relaxin in Acute Heart Failure (RELAX-AHF) development program: correlation with outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(2):196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison BA, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, et al. Serelaxin, recombinant human relaxin-2, for treatment of acute heart failure (RELAX-AHF): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9860):29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishu K, Hamdani N, Mohammed SF, Krüger M, Ohtani T, Ogut O, et al. Sildenafil and B-type natriuretic peptide acutely phosphory-late titin and improve diastolic distensibility in vivo. Circulation. 2011;124(25):2882–2891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.048520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamdani N, Bishu KG, Frieling-Salewsky von M, Redfield MM, Linke WA. Deranged Myofilament Phosphorylation and Function in Experimental Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Cardiovascular Research. 2012 Dec 4; doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erdmann E, Semigran MJ, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Agrawal R, Mitrovic V, et al. Cinaciguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase activator, unloads the heart but also causes hypotension in acute decompensated heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(1):57–67. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Redfield MM. Effect of Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection Fraction A Randomized Clinical Trial Effect of PDE-5 on exercise and clinical Status in HFPEF. JAMA. 2013;309(12):1268. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2024. This study examined the effect of sildenafil on exercise capacity and clinical status in ambulatory HFpEF patients. Despite strong rationale for testing this agent in HFpEF, no beneficial effect was seen.

- 42.van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Falcao-Pires I, Leite-Moreira AF, Begieneman MPV, Bronzwaer JGF, et al. Low myocardial protein kinase G activity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2012;126(7):830–839. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, et al. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114(5):397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brandimarte F, Vaduganathan M, Mureddu GF, Cacciatore G, Sabbah HN, Fonarow GC, et al. Prognostic implications of renal dysfunction in patients hospitalized with heart failure: data from the last decade of clinical investigations. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18(2):167–176. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9317-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith GL, Lichtman JH, Bracken MB, Shlipak MG, Phillips CO, DiCapua P, et al. Renal impairment and outcomes in heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(10):1987–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giamouzis G, Butler J, Starling RC, Karayannis G, Nastas J, Parisis C, et al. Impact of dopamine infusion on renal function in hospitalized heart failure patients: results of the Dopamine in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (DAD-HF) trial. J Card Fail. 2010;16(12):922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.07.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riter HG, Redfield MM, Burnett JC, Chen HH. Nonhypotensive low-dose nesiritide has differential renal effects compared with standard-dose nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure and renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(11):2334–2335. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Blood Institute NHLBI. Renal Optimization Strategies Evaluation in Acute Heart Failure and Reliable Evaluation of Dyspnea in the Heart Failure Network (ROSE) Study (ROSE/REDROSE) ClinicalTrials.gov. Report No.: NCT01132846.

- 49.Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Makani H, Rimoldi SF, Allemann Y, White CJ, et al. Flash pulmonary oedema and bilateral renal artery stenosis: the Pickering syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(18):2231–2235. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006:e463–e654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gandhi SK, Powers JC, Nomeir AM, Fowle K, Kitzman DW, Rankin KM, et al. The pathogenesis of acute pulmonary edema associated with hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(1):17–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440103. This is a seminal study that clarified the pathophysiology of HFpEF patients with AHF.

- 52.Kramer K, Kirkman P, Kitzman D, Little WC. Flash pulmonary edema: association with hypertension and reoccurrence despite coronary revascularization. Am Heart J. 2000;140(3):451–455. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.108828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kociol RD, Pang PS, Gheorghiade M, Fonarow GC, O'Connor CM, Felker GM. Troponin elevation in heart failure. 14. Vol. 56. JAC Elsevier Inc.; 2010. pp. 1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cotter G, Felker GM, Adams KF, Milo-Cotter O, O'Connor CM. The pathophysiology of acute heart failure—is it all about fluid accumulation? Am Heart J. 2008;155(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CSP, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, et al. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(11):845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zakeri R, Borlaug BA, McNulty S, Mohammed SF, Lewis GD, Semigran MJ, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on exercise capacity in Diastolic Heart Failure: a RELAX Trial Ancillary Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 61 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000568. 10_S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linssen GCM, Rienstra M, Jaarsma T, Voors AA, Van Gelder IC, Hillege HL, et al. Clinical and prognostic effects of atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients with reduced and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(10):1111–1120. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bitter T, Faber L, Hering D, Langer C, Horstkotte D, Oldenburg O. Sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(6):602–608. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaneko Y, Floras JS, Usui K, Plante J, Tkacova R, Kubo T, et al. Cardiovascular effects of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(13):1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]