SUMMARY

Osteomas are the most common fibro-osseous lesions in the paranasal sinus. They are benign tumours characterized by slow growth and are often asymptomatic. Treatment is indicated in sphenoid osteomas that threaten the optic canal or orbital apex and in symptomatic cases. The choice of surgical management depends on the location, size and experience of the surgeon. An open approach allows tumour removal with direct visual control and remains the best option in large tumours, but the continued progression in endoscopic approaches is responsible for new indications in closed techniques. Immediate reconstruction allows aesthetic and functional restoration of neighbouring structures, which should one of the goals in the treatment of this benign entity. We report a case of a giant ethmoid osteoma with orbital invasion treated by a combined open craniofacial approach with reconstruction of the anterior cranial base and orbital walls. The literature is reviewed and aetiopathogenic theories, diagnostic procedures and surgical approaches are discussed.

KEY WORDS: Orbital osteoma, Giant osteoma, Ethmoidal osteoma, Orbital reconstruction

RIASSUNTO

Gli osteomi sono le più comuni lesioni osteo-fibrose dei seni paranasali. Si tratta di neoplasie benigne, frequentemente asintomatiche, caratterizzate da un lento accrescimento. Il trattamento è indicato negli osteomi sfenoidali che minacciano il canale ottico o l'apice orbitario, e nei casi sintomatici. La scelta dell'approccio chirurgico dipende dalla localizzazione e dalla grandezza della lesione, nonché dall'esperienza dell'operatore. La tecnica aperta consente la rimozione del tumore con controllo visivo diretto e rimane l'opzione di prima scelta nelle neoplasie estese, ma i continui progressi in ambito endoscopico hanno portato ad un aumento dei casi in cui è indicata la tecnica chiusa. La ricostruzione immediata permette un ripristino estetico e funzionale delle strutture adiacenti, che rappresenta l'obbiettivo primario del trattamento di tali lesioni. In questo lavoro abbiamo descritto un caso di osteoma etmoidale gigante con invasione dell'orbita trattato mediante approccio combinato craniofacciale aperto e ricostruzione del pavimento della fossa cranica anteriore e delle pareti orbitarie. Vengono inoltre discusse le teorie eziopatogenetiche, le procedure diagnostiche e gli approcci chirurgici descritti in letteratura.

Introduction

Osteomas are relatively rare, benign bone neoplasms that usually develop in craniofacial and jaw bones 1. They are slow-growing tumours, often asymptomatic for many years, and diagnosed incidentally on radiographs. They are the most frequent neoplams of the paranasal sinuses, most often originating from the ethmoid and frontal bones. Ethmoid osteomas are detected earlier because of the limited anatomical space. Orbital or skull base involvement is very unusual, causing ophthalmologic and neurological symptoms, and is one of the indications for early intervention.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for symptomatic ethmoid osteomas. Due to the rapid progress of endoscopic sinus surgery, even small osteomas can be easily removed without the need for an external approach. However, large cases with intraorbital or skull base expansion are still treated with an external approach.

We report a case of an anterior skull base osteoma of ethmoid cells with frontal and orbital extension producing exophthalmos. The aetiology, manifestations and management of this rare entity are discussed.

Case report

A 62-year-old woman was referred to the Maxillofacial Department of La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain, with a 1-year history of gradual painless proptosis of her right eye. The patient reported loss of visual field and visual acuity in her right eye as well as a reduction in her capacity to smell.

An ophthalmologic examination showed proptosis of the right eye. Extra-ocular movements were not restricted, with no alteration of the anterior segment or fundus. Visual acuity was impaired due to cataracts in both eyes. Anterior rhinoscopy showed deviation of the lateral nasal wall. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a 4 × 4.5 cm right ethmoid polylobulated lesion, with a dense compact cortical margin and a matrix with medullary-like attenuation (Fig. 1). The lesion extended from the right frontal sinus floor to the right sphenoid sinus, and grew superiorly and posteriorly into the right orbit, pushing down the extraocular musculature, optic nerve and eyeball in an inferior and anterior direction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a homogeneous extraconal mass with iso-low signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging. An endoscopic transnasal biopsy was performed and histopathological findings confirmed the diagnosis of benign osteoma.

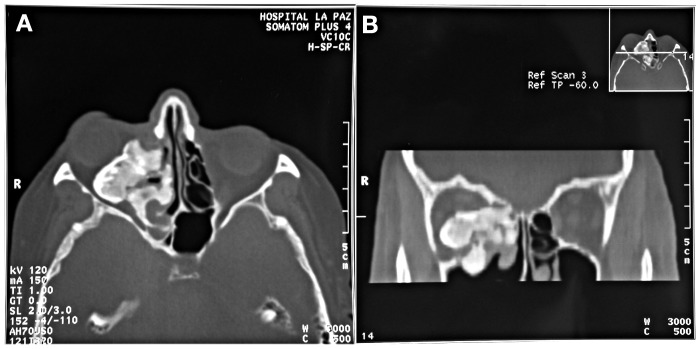

Fig. 1.

Preoperative CT. A, axial view: 4 × 4.5 cm right ethmoid polylobulated lesion. B, coronal view: the lesion extended from the right frontal sinus floor to the right sphenoid sinus, and grew superiorly and posteriorly into the right orbit.

Surgical intervention was performed under general anaesthesia. After a coronal flap and subciliary approach, the frontal bone, upper rims of the orbit and nasal root were exposed. A right frontal craniotomy and a right frontoorbital bar extending to the lateral orbital wall were performed, and the tumour was removed.

The defect was reconstructed immediately. Temporal fascia was used in dural reconstruction. Two autogenous bone grafts obtained from calvarial bone were used to reconstruct the medial and orbital floor, with the additional use of a titanium mesh. A galeal-pericranial flap was used to cover the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The fronto- orbital bar was replaced using 15 mm titanium miniplates. Epidural and subgaleal drains were placed (Fig. 2). The patient made excellent recovery in the immediate and late postoperative periods. The final histopathologic report confirmed a diagnosis of osteoma with osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. Proptosis resolved, ocular movements remained intact and no visual defects were detected. A postoperative CT scan showed no residual tumour. At one year after intervention, a frontal osseous irregularity was corrected using a bone filler (Norian®, Norian Corporation, Cupertino, CA) (Fig. 3). There has been no recurrence after 5 years of follow-up. Two years postoperatively the patient underwent surgical correction of cataracts, with improvement of visual acuity.

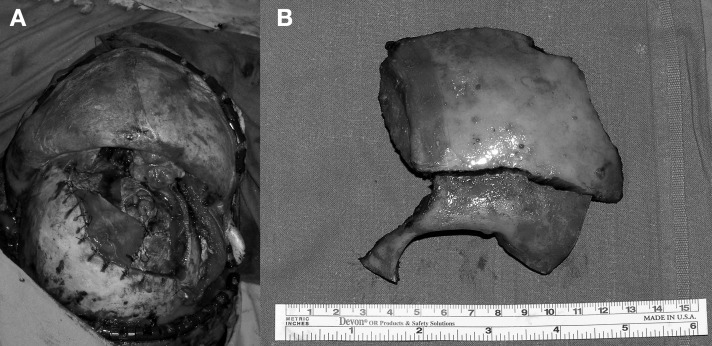

Fig. 2.

A, Intraoperative view of the combined cranioorbital approach. B, Portion of cranioorbitotomy.

Fig. 3.

A, Postoperative view showing the frontal contour defect. B, The frontal contour defect was corrected in a second intervention using a bone filler. C, One-year postoperative CT showed no residual tumour.

Discussion

Osteomas are the most common benign tumours of the paranasal sinuses 2, usually found in the frontal sinus (71.8%) and less often in the ethmoid sinus (16.9%), maxillary sinus (6.3%) or sphenoid sinus (4.9%) 3.

Osteomas are slow-growing neoplasms that are generally diagnosed incidentally in 1% of plain sinus radiographs and in 3% of CT of the sinuses 3 4. They affect 0.43-1% of the population 5, with a male preponderance. Only 5% of cases become symptomatic or require surgery 3. Although giant sinus osteomas have been reported, they are rare with the average size being below 2 cm 1.

Different theories exist concerning the factors responsible for their formation (Table I). A combination of traumatic, inflammatory and embryologic hypotheses is the most widely accepted at present 3 4 6.

Table I.

Pathogenetic theories of paranasal sinus osteoma.

| Traumatic theory of Gerber | Injuries suffered during puberty may cause the growth of osteomas from bone sequestra |

| Inflammatory theory | Sinusitis may stimulate osteoblastic proliferation or it can be a secondary symptom arising from obstruction of sinus drainage |

| Embryologic theory | Osteoma arises from the remains of persistent embryologic cells located at the junction of the ethmoid and frontal sinuses |

Osteomas are usually asymptomatic. When they become symptomatic, it is often related to the location of the tumour. The most common symptom is headache 6 7. When osteomas grow into the anterior cranial fossa, they can produce meningitis, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, pneumatocele 8 or brain abscess 9 10.

Secondary orbital invasion is relatively uncommon, representing 0.9 to 5.1% of all orbital tumours 3, and occurs more frequently in ethmoid, fronto-ethmoid and frontal locations. Tumour growth into the orbit may cause eyeball displacement with gradual proptosis and diplopia, and eventually restriction of extraocular movements. Rare complications include amaurosis 11, orbital emphysema or cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea.

Histologically, osteomas can be divided into ivory, mature or mixed types 1. Almost all osteomas contain different proportions of the three types, suggesting that they grow outwards from the centre, with increasing maturation at the periphery of the tumour. This may explain why partial resection leaving residual peripheral tissue does not often lead to recurrence 5.

The radiological appearance is a homogeneously calcified, lobulated, sharply defined tumour that fills the internal contour of the sinus of origin 5. MRI is superior to CT scan in showing optic nerve or optic canal invasion. Radionuclide bone scan may help to differentiate an actively growing lesion from a stable one.

Osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma are usually the major differential diagnostic considerations 12. Other benign fibro-osseous and cartilaginous lesions include fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, or chondroma 1 5. A biopsy of the lesion is required if the clinical and radiological presentation is unusual.

Management depends on symptoms as well as the size and location of the tumour. Observation and periodic radiological controls are recommended in most asymptomatic cases, except for those located in the sphenoid sinus that threaten the optic canal or orbital apex 3-5.

In our case, the mass extended beyond the orbit causing ocular displacement. Visual acuity was most likely affected by two factors, namely cataracts and tumour compression. It was decided to defer cataract intervention given the risk of dehiscence of the corneal incisions due to the compression.

Surgical treatment can be carried out by either endoscopic or open surgery. The choice must consider several factors such as tumour location, extension, dimension and the experience of the surgeon. Rapid progress in endoscopic surgery has enabled more effective endoscopic approaches in small and medium sized tumours 2 4 13. The advantages of an endoscopic approach are limitation of blood loss and reduced postoperative morbidity, with a shorter hospitalization time 2 14. The most important disadvantages are the difficult management of intraoperatory complications, such as bleeding, inadequate control of the margins of the lesion and the surgical experience needed. Open approaches allow radical tumour removal under direct visual control. Transfacial approaches are limited to selected cases depending on the extension of the tumour 7 15. An intracranial open approach is the technique of choice for large lesions such as the one described here, where the tumour extended to the orbit or the anterior skull base. However, there are disadvantages, such as a longer hospital stay and the risk of damage to the frontal branch of the facial nerve. Depending on the location, a combined cranioendoscopic approach is recommended to perform complete excision with optimal brain control 2 14 16.

Orbital invasion usually necessitates early surgical treatment. In larger cases, orbitocranial approaches combined with other transfacial approaches may be necessary 17. A frontal craniotomy combined with a burr hole fronto-orbitotomy and a subciliary approach was used in our case, providing excellent control of the disease in the skull base, posterior orbital region and orbital walls.

The resulting defect should be repaired immediately. Small dura defects can be addressed with local flaps, such as pericranial or galeal-pericranial flaps 18, which were used in the present case. For orbital reconstruction, calvarial grafts are preferred in adults as resorption is more predictable and it is possible to obtain a large amount of bone from the same operative area 19.

Postoperative morbidity depends on the surgical approach. Injury to the periorbita, optic nerve or cribriform plate is possible. Tumour recurrence due to incomplete resection is very unusual. Once the area is stable, yearly controls for at least three years are recommended to identify recurrent or persistent tumour 20.

References

- 1.McHugh JB, Mukherji SK, Lucas DR. Sino-orbital osteoma. A clinicopathologic study of 45 surgically treated cases with emphasis on tumors with osteoblastoma-like features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1587–1593. doi: 10.5858/133.10.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miman MC, Bayindir T, Akarcay M, et al. Endoscopic removal technique of a huge ethmoido-orbital osteoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:1403–1406. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181aee30e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansour AM, Salti H, Uwaydat S, et al. Ethmoid sinus osteoma presenting as epiphora and orbital cellulitis: Case report and literature review. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43:413–426. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naraghi M, Kashfi A. Endonasal endoscopic resection of ethmoido-orbital osteoma compressing the optic nerve. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:408–412. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(03)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selva D, White VA, O'Connell JX, et al. Primary bone tumors of the orbit. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:328–342. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma'luf RN, Ghazi NG, Zein WM, et al. Orbital osteoma arising adjacent to a foreign body. Opthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19:327–330. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000075021.85888.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanyura H, Kaminski Z, Stopa Z. Treatment of osteomas located between the anterior cranial base and the face. J Craniomaxillof Surg. 2005;33:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson D, Tan L. Intraparenchymal tension pneumatocele complicating frontal sinus osteoma: case report. Neurosurg. 2002;50:878–880. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200204000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koyuncu M, Belet U, Sesen T. Huge osteoma of the frontoethmoidal sinus with secondary brain abscess. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2000;27:285–287. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(00)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Summers LE, Mascott CR, Tompkings JR, et al. Frontal sinus osteoma associated with cerebral abscess formation: a case report. Surg Neurol. 2001;55:235–239. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(01)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siboni P, Shindo M. Orbital osteoma with gaze-evoked amaurosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:788–788. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.5.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sires BS, Benda PM, Stanley RB, Jr, Rosen CE. Orbital osteoid osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:414–415. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagella F, Giourgos G, Matti E, et al. Removal of a frontoethmoidal osteoma using the sonore omni ultrasonic bone curette:first impressions. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:307–309. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31815988c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatki AM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, et al. Endonasal surgery of the ventral skull base- endoscopic transcranial surgery. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am. 2010;22:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livaoĝlu M, Cakir E, Karaçal N. Large orbital osteoma arising from orbital roof: Excision through an upper blepharoplasty incision. Orbit. 2009;28:200–202. doi: 10.1080/01676830902920322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yiotakis I, Eleftheriadou A, Giotakis E, et al. Resection of giant ethmoid osteoma with orbital and skull base extension followed by duraplasty. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;14:110–110. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai BS, Harish K, Venkatesh MS, et al. Ethmoidal osteoid osteoma with orbital and intracraneal extension. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2005;5:2–2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moyer JS, Chepeha DB, Teknos TN. Contemporary skull base reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:294–299. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000131445.27574.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brusati R, Biglioli P, Mortini P, et al. Reconstruction of the orbital walls in surgery of the skull base for benign neoplasms. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29:325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eller R, Sillers M. Common fibro-osseus lesions of the paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2006;39:585–660. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]