SUMMARY

In some patients suffering from acute unilateral peripheral vestibular deficit, the head impulse test performed towards the affected side reveals the typical catch-up saccade in the horizontal plane, and an oblique, mostly vertical, upward catch-up saccade after the rotation of the head towards the healthy side. Three cases are reported herein, which have been studied using slow motion video analysis of the eye movements captured by a high-speed webcam (90 fps). The clinical evidence is discussed and a pathophysiological explanation is proposed, consisting in a selective hypofunction of the superior semicircular canal during superior vestibular neuritis.

KEY WORDS: Superior vestibular neuritis, Vertical catch-up saccade, High-speed video head impulse test, Selective superior semicircular canal paresis

RIASSUNTO

In alcuni pazienti affetti da deficit vestibolare periferico acuto, il Test Impulsivo Cefalico (HIT) eseguito verso il lato malato evidenzia un tipico saccadico di rifissazione sul piano orizzontale, mentre, quando eseguito verso il lato sano, provoca un saccadico obliquo, in maggior misura verticale, verso l'alto. Sono stati studiati tre pazienti in cui il movimento oculare è stato registrato con webcam ad alta frequenza di campionamento (90 fps) ed analizzato al rallentatore. Sono esposte e discusse le evidenze cliniche e ne viene proposta una interpretazione fisiopatologica consistente nella ipofunzione selettiva del canale semicircolare superiore in corso di neurite vestibolare superiore.

Introduction

The head impulse test (HIT) is of fundamental importance in the examination of the dizzy patient because it directly explores the function of the lateral semicircular canal (LSC), allowing accurate diagnosis of peripheral vestibular deficit where the analysis of the nystagmus (ny) is often non-specific 1.

In order to increase the sensitivity of HIT when it generates unclear results, since February 2012, a high-speed webcam has been used in our facility to obtain a more accurate evaluation of eye movements during routine vestibular exam. This novel protocol led to unexpected results.

In almost 10 months of activity, the high-speed videoassisted head impulse test (HSVA-HIT) has been performed on 65 patients presenting with vertigo of various origins; 30 patients had unilateral peripheral vestibular deficit, identified by HIT evidence of a horizontal catchup saccade after torsion of the head towards the affected labyrinth. Among these, 6 patients showed an unexpected downward eye movement during the torsion of the head towards the healthy side, followed by an oblique upward catch-up saccade. Three of the six patients showing such behaviour were further studied and underwent routine instrumental audio-vestibular tests and brain MRI.

Materials and methods

All patients were examined within a week since the beginning of their vertigo, and a second check-up was scheduled one month later. Further visits were then programmed for instrumental tests or rehabilitative sessions as needed.

To begin with, each patient was examined for clinical evidence of otologic disease and was administered a pure tone audiometry test (with Amplaid 319 in a soundproof cabin). After that, patients underwent a careful clinical bedside vestibular exam consisting in the search, under Frenzel's glasses, for spontaneous ny, positional and positioning ny (Dix-Hallpike), gaze and rebound ny, mastoid vibration ny (100 Hz), head shaking ny and hyperventilation ny. Finally, patients were given the Romberg Test, the Untemberger Test and the HIT.

HSVA-HIT: the patient, sitting in front of the webcam (Philips SPC 900NC PC camera at 90 fps) at a distance of 50 cm, is asked to look at the camera (which has a white led just upon the lens), while the clinician at his back moves his head in the yaw plane with brief abrupt unpredictable torsions of about 30°. The camera is placed at the same height of the patient's eyes, on an adjustable tripod, well aligned horizontally. The video of the exam is recorded at 90 fps with a resolution of 352 × 288 pixels, and then viewed in slow motion (0.33×) to precisely assess eye movements during and after the head impulse. HSVA-HIT was performed in both the yaw and the vertical planes [pitch, left anterior-right posterior (LARP) and right anterior-left posterior (RALP)] 2.

Caloric vestibular stimulation was performed according to Fitzgerald and Hallpike's standards with computerized ENG evaluation of the caloric ny.

Cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (CVEMPs), induced by air-conducted sound stimuli (130 dB Spl 500 Hz logon transmitted bilaterally by headphones), were recorded at the level of the sternocleidomastoid muscles, with the patient lying in the supine position while keeping his/her head actively uplifted 3.

Ocular VEMPs (O-VEMPs) were recorded from the inferior oblique muscles, with the patient lying supine, while staring at a visual target 20° above his/her horizon, using the same air-conducted sound stimulus mentioned above for C-VEMPs. Both ENG and VEMPs were performed using an Amplaid MK12 instrument 4.

Results

Case 1

Male, 62-years-old, smoking more than 20 cigarettes a day, suffering from hypertension (treated with ramipril 10 mg QD). The patient presented for a vestibular examination, complaining of acute vertigo and nausea with acute onset 5 days prior, without hearing symptoms, headache or loss of consciousness. He had never suffered from such symptoms before and had a family history of vascular disease.

Bedside vestibular examination showed a horizontal ny with fast phase beating towards the left (of the patient) and mild torsional clockwise component (as seen from the clinician's point of view); this ny stopped under fixation of a visual target and did not change its direction in any of the head positions tested (sitting, supine and side lining), reducing its amplitude when lying on the left side. The patient had a difficult gait (not ataxic) and a clear rightward step deviation at Untemberger's test. Neurological exam and CT scan were negative. Pure tone audiometry was normal for the age (mild presbycusis). Brain MRI, performed two months after onset of vertigo, revealed many areas of leukoencephalopathy of microvascular origin.

HIT was positive when the head was turned to the right with a clear catch-up saccade in the horizontal plane, but an unexpected oblique upward catch-up saccade was observed when the head was turned to the left. HSVA-HIT was performed and the above-mentioned oblique upward saccade was confirmed (Figs. 1A-F).

Fig. 1.

Sequence of photos captured during HIT in patients suffering from right superior vestibular neuritis. Case 1: A-F, case 2: G-N, case 3: O-T (see text). For each patient, the first line of photos shows the head before the impulse to the right (A, G, O), after this impulse, just before the catch-up saccade (B, H, P) and after the saccade (C, I, Q). The second line of photos shows, for each patient, the head before the impulse to the left (D, L, R), after this impulse, just before the catch-up saccade (E, M, S) and after the saccade (F, N, T).

HSVA-HIT in the pitch plane was also recorded revealing a clear upward catch-up saccade after nose-down tilt of the head, and a normal eye movement during nose-up tilt of the head with no catch-up saccade. HSVA-HIT in the RALP and LARP planes revealed a catch-up saccade only in RALP plane after nose-down tilt of the head, whereas all other movements had a normal gain of the vestibuloocular reflex (VOR) with no catch-up saccades.

Vestibular neuritis (VN) of the right side was diagnosed, possibly due to microvascular disease; the patient was instructed about home vestibular rehabilitation exercises and received steroid therapy (prednisone 25 mg QD for 7 days, then progressive reduction over 2 weeks) together with gastric protection (lansoprazole 15 mg QD for 2 weeks), and ASA (75 mg QD).

One month later the patient was examined, and his previous vertigo had disappeared except for some residual difficulties while walking in wide-open space and in darkness. However, he had been complaining of postural vertigo for 4 days. The clinical vestibular exam evidenced a typical paroxysmal positional vertigo (PPV) due to lithiasis of the right inferior semicircular canal (ISC) that led to a diagnosis of Lindsay-Hemenway Syndrome 5.

HSVA-HIT in the yaw plane was performed again, and confirmed the same findings revealed during the first visit. No evidence of spontaneous ny in the sitting position and normal results obtained with Untemberger's test (rightward deviation within 30°) indicated good compensation of the vestibular deficit.

For two months, sessions of vestibular rehabilitation (using Semont's Liberatory and a personal canalith repositioning manoeuvre) were held, but although subjectively improved, PPV was still present 8 weeks later. The absence of a liberatory ny after rehabilitative manoeuvres led to the diagnosis of persistent cupulolithiasis of the ISC; PPV finally disappeared one month later without further treatment 6 7.

A caloric vestibular test was performed two months after vertigo onset, revealing a right canal paresis (CP 55%) with mild directional preponderance (DP 28%) of the ny towards the left.

C-VEMPs were normal in both sides, while O-VEMPs were absent under the left eye. Four months after vertigo onset, the HIT in the yaw plane revealed the same pattern of ocular response seen before; HSVA was not repeated due to the large amplitude of the catch-up saccade that was clearly visible, as in previous visits.

At the end of follow-up (4 months), all these findings confirmed the diagnosis of right superior vestibular neuritis (SVN) with persistent deficit of LSC and superior SC (SSC) function, in good central compensation, and persistent deficit of utricular macula function, with preservation of saccular macula and ISC function 8.

Case 2

Female, 62-years-old, who had never suffered from vertigo before. The patient arrived to the hospital emergency room complaining of acute vertigo and vomiting; these symptoms had started 2 days earlier. Neither headache nor auditory symptoms were reported at the time of vestibular assessment. Neurological examination was negative, pure tone audiometry was normal. Brain MRI, performed a week later, evidenced subcortical and deep tissue point signal alterations of ischaemic microvascular origin and dilation of perivascular spaces in the brainstem.

In addition, vestibular examination revealed acute peripheral vestibular deficit of the right side with the following signs: spontaneous ny with horizontal fast phase to the left side and torsional component beating clockwise. This ny was the same in all positions of the head and was inhibited by fixation of a visual target, whereas hyperventilation and 100 Hz mastoid vibrations did not change it. Clear rightward step deviation in the Untemberger's test was seen.

HIT was positive when the head was turned to the right with a clear catch-up saccade in the horizontal plane, but an unexpected oblique upward catch-up saccade was observed when the head was turned to the left. HSVA-HIT was performed and the above-mentioned oblique upward saccade was confirmed (Figs. 1G-N).

VN of the right side was diagnosed and steroid therapy was started (prednisone 25 mg BID for 2 days, then progressive reduction over 2 weeks) together with gastric protection (lansoprazole 15 mg QD) and an oral heparinoid (sulodexide 250 ULS 1 cpr BID for 2 months).

At a control visit 10 days later, the patient felt much better. She reported that acute vertigo had disappeared in a week and, at that time, she was suffering only from mild unsteadiness. The bedside vestibular examination revealed a small spontaneous horizontal ny beating to the right in all the positions of the head, which was inhibited by fixation and augmented after head shaking test. HIT was bilaterally negative both in horizontal and vertical planes, and Untemberger's test was within the norm. Recovery syndrome after VN of the right labyrinth was diagnosed.

Twenty days later the patient was checked again: she did not complain about vestibular symptoms and bedside vestibular examination was negative. At that time, C-VEMPs were registered on both sternocleidomastoid muscles with the same amplitude; O-VEMPs were recorded only under the right eye. This led to the assessment of persistent right utricular deficit, with preserved bilateral saccular function.

The final diagnosis was right SVN that recovered with "restitutio ad integrum" of the canal function and persistent subclinical damage of the utricular macula.

Case 3

Male, 62-years-old, truck driver, smoking more than 20 cigarettes a day. The patient came for urgent vestibular examination, complaining of acute vertigo that started 7 days before, together with vomiting and epigastric pain; neither auditory symptoms nor headache were present. He did not report any significant pathology in his history and had never suffered from vestibular diseases. Neurological exam and CT were negative, pure tone audiometry was normal for his age (mild bilateral deafness for high frequencies due to chronic acoustic trauma and presbycusis). Brain MRI performed a few weeks later showed marked dilatation of the lateral ventricles and the cortical sulci, and many areas of leukoencephalopathy of microangiopathic origin.

Vestibular clinical examination evidenced right acute peripheral vestibular deficit with the following signs: spontaneous ny beating to the left with a torsional component beating clockwise, present in all the positions of the head and inhibited by fixation. Clear rightward step deviation during Untemberger's test was evidenced.

HIT was positive when the head was turned to the right with a clear catch-up saccade in the horizontal plane, but an unexpected oblique upward catch-up saccade was observed when the head was turned to the left. HSVA-HIT was performed and the oblique upward saccade above mentioned was confirmed (Figs. 1O-T).

VN of the right side was diagnosed and the patient was instructed about home vestibular rehabilitation exercises; he received 2 weeks of steroid therapy (prednisone 25 mg QD at the beginning) together with gastric protection (lansoprazole 15 mg QD) and ASA (75 mg QD).

One month later the patient was controlled, his vertigo had disappeared, spontaneous ny was not evident and step deviation was within the normal range; HIT was still positive with the same pattern of ocular response reported before. He had a persistent peripheral right vestibular deficit with good central compensation.

A few weeks later the patient suffered from mild positional vertigo, but he recovered without any treatment and did not undergo vestibular examination.

Four months after the beginning of his vertigo, he underwent a scheduled control visit: he was free of any vertigo symptoms and did not complain of unsteadiness; neither spontaneous ny nor step deviations were evident, but HIT was still showing the same ocular response seen before. HSVA-HIT was again performed in the yaw plane confirming the oblique upward saccade above mentioned while in the pitch plane a very little catch-up saccade only after nose-down movement was inconstantly seen. HIT in RALP and LARP plane was normal, with only minor anomalies in the RALP plane.

Caloric stimulation evidenced a severe hyporeflexia of the right labyrinth (CP 90%) without latent ny (DP 5% to the left). O-VEMPs were recorded bilaterally, as well as C-VEMPs that presented reduced amplitude in the right sternocleidomastoid muscle, indicating the integrity of the utricular macular function bilaterally and slight damage of the right saccular macula.

Discussion

All patients herein had acute labyrinthine damage, of various origins, which impaired the function of the SCs and maculae to different degrees. All patients had a clear deficit of the LSC that was shown by HIT in the horizontal plane towards the affected side and measured by caloric test in cases 1 and 3.

In case 1, a clear deficit of VOR in the vertical plane was observed at HIT during nose-down tilt of the head (pitch and RALP), confirming unilateral SSC impairment; in case 2, vertical HIT was within the norm and in case 3 it produced unclear results.

In patients 1 and 2, the damage also involved the utricular macula, while in case 3 this was preserved whereas a slight damage of the saccular macula was seen (this patient was examined with caloric test and VEMPs only 4 months after the onset of the vertigo).

In all these patients, slow motion analysis of eye movement during HIT on the yaw plane towards the healthy side revealed an active downward movement of the eyes that was more evident in the eye ipsilateral to the affected ear.

The analysis of the eye positions was carried out on still frame images captured at the beginning and end of the head movement, and at the beginning and end of the following catch-up saccade.

This type of analysis only detects the direction of the eye movement in the horizontal and vertical planes (not torsional), does not allow quantifying it and presents some difficulties for the eye located furthest from the webcam (due to the perspective effects). Despite these limitations, the movements seen are so clear that the reported ocular sign is evident with negligible bias. Figure 2 shows the analysis performed on case 2. Similar results were obtained in the other cases.

Fig. 2.

Photo analysis of the oblique catch-up saccade after impulse test towards the healthy side. Dotted lines are for the right eye, and dashed lines are for the left eye. A and C lines show the position of the pupils before the saccade and B and D their position after the saccade. E and G lines indicate the level of the eyelids before the saccade and F and H their position after the saccade. Arrows show the direction of the saccade: it is mainly vertical with a slight horizontal component and the amplitude is greater at the right eye (ipsilateral to the lesion).

According to recent literature, a movement of the head in the yaw plane activate mostly the LSC, up to 94% of the angular acceleration, although both the vertical SCs are activated in a smaller percentage: up to 26% of the angular acceleration on the ISC and up to 18% on the SSC 9.

According to Ewald's second law, both vertical canals are excited by ampullofugal endolymphatic flows. This is the reason why they are both activated by movements towards the opposite ear, whereas the LSC is activated by movement towards the ipsilateral ear.

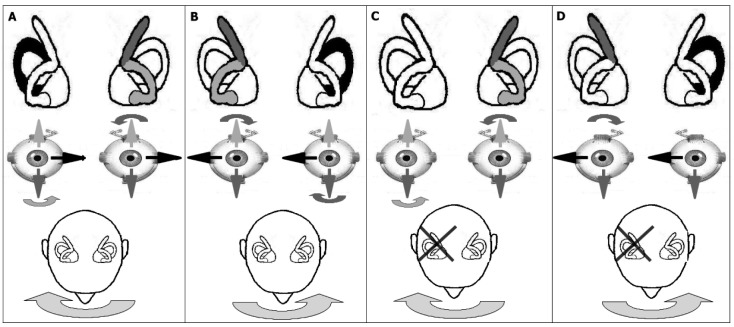

Concerning vertical eye movements only, in the normal labyrinth stimulation of both SSC and ISC of the same side leads to bilateral activation of antagonist ocular muscles with no resulting eye movement in the vertical plane. (Figs. 3A, B)

Fig. 3.

Activation of semicircular canals and eye movements during HIT in normal conditions (A and B) and in superior vestibular neuritis (C and D). In normal conditions, activation of both vertical semicircular canals stabilizes the eyes in the vertical plane, only the action of LSC moves the eyes: no catch-up saccades are necessary to stare at the target. During superior vestibular neuritis, only the ISC of the affected side is still functioning. During torsion of the head towards the affected side, contralateral vertical semicircular canals stabilize the eyes in the vertical plan, but they do not move horizontally, so a horizontal catch-up saccade is necessary to bring back the sight on the visual target. During torsion towards the healthy side, eyes move almost normally in the horizontal plane (a slight deficit of VOR is due to the absence of inhibitory action of LSC of the affected side), but due to the isolated action of ISC, eyes move improperly downward, so that an oblique (mostly vertical) catch-up saccade is triggered.

In labyrinths with lesions of the SSC and preserved function of the ISC (as in SVN), impulse head torsion towards the healthy side leads to a downward eye movement that responds to the inputs coming from the ISC that is no longer counteracted by the antagonist action of the damaged SSC. (Figs. 3C, D)

According to the muscular projections of the single SC through the VOR, the eye movement recorded in the patients analysed is consistent with this hypothesis 10 11.

The clinical sign observed revealed a much greater involvement of both vertical SCs during impulsive head rotation in the yaw plane than previously indicated in the literature 12-14.

Conclusions

Patients suffering from SVN present vertical downward eye movements during HIT performed in the yaw plane towards the healthy side, followed by an oblique (mostly vertical) upward catch-up saccade. HIT in the horizontal plane acts at the same time on all three SCs, although with different directions and magnitude. The reported clinical sign is consistent with lack of excitation of the SSC of the affected labyrinth, while the ISC still works properly.

HIT in the vertical planes never reached substantial significance in routine bedside vestibular examination: in the pitch plane, it has a very low sensitivity due to the contemporary activation of vertical SCs of both sides (SSCs for nose-down pitch, ISCs for nose-up pitch). In RALP and LARP planes, its quite difficult to perform a satisfactory test because the amplitude of the head movement is restricted and the catch-up saccade is very small; this leads to uncertain results even with the support of high-speed video recording; computer analysis of both head acceleration and eye movement is essential to properly assess this function.

The sign reported here gives clear indications of SSC impairment, when ISC is still functioning, even in those patients having unclear responses to HIT performed in the vertical planes, and even using high-speed video recording. This is because the eye movement occurs in a plane that is orthogonal to the head movement, and it is an active downward shift that makes it clearly visible without any instrument.

This clinical sign is typically not reported because its significance is unknown, unexpected and usually ascribed to the patient's distraction; high-speed video recording is able to augment the sensitivity and helps to study doubtful cases. The positivity of this sign is a direct expression of the SSC dysfunction and remains evident even after satisfactory central compensation of vestibular impairment.

Since the HSVA-HIT has been initially performed only in patients with doubtful horizontal saccade, many cases with vertical catch-up saccade on the affected side were missed at that time. Systematic application of this technique has been introduced only in the last 4 months (all the studied cases belong to this period); this brings about the hypothesis that the prevalence of such a clinical sign is much higher than what is presented in this study (6/30). Further studies on the physiology of the vertical SC involvement during head impulses in the yaw plane are necessary to fully understand this new evidence.

References

- 1.Halmagyi DM, Curthoys IS. A clinical sign of canal paresis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:737–739. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520310043015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cremer PD, Halmagyi GM, Aw ST, et al. Semicircular canal plane head impulse detect absent function of individual semicircular canals. Brain. 1988;131:699–716. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicini C, Valli P, Valli S, et al. Il nostro assetto di registrazione dei VEMPs. In: Vicini C, editor. Atti delle XVIII Giornate Italiane di Otoneurologia. Palermo: 2001. pp. 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curthoys IS, Vulovic V, Manzari L. Ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potential (oVemp) to test utricular function: neural and oculomotor evidence. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32:41–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindsay JR, Hemenway WG. Postural vertigo due to unilateral sudden partial loss of vestibular function. Annal Otol. 1956;65:692–706. doi: 10.1177/000348945606500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semont A, Freyss G, Vitte E. Curing the BPPV with a liberatory maneuver. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1988;42:290–293. doi: 10.1159/000416126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.d'Onofrio F, Costa G, Mazzone A, et al. Canalith repositioning maneuver: proposal of a new therapy for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior semicircular canal. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1998;18:300–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AW ST, Fetter M, Cremer PD, et al. Individual semicircular canal function in superior and inferior vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 2001;57:768–774. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Della Santina CC, Potyagaylo V, Migliaccio A, et al. Orientation of human semicircular canals measured by threedimensional multiplanar CT reconstruction. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2005;6:191–206. doi: 10.1007/s10162-005-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Waele C, Tran Ba Huy P. Anatomie des voies vestibulaires centrales. In EMC (Paris) ORL. 2001;20-038-A-10:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchino Y, Kushiro K. Differences between otolith- and semicircular canal-activated neural circuitry in the vestibular system. Neurosci Res. 2011;71:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber KP, Aw ST, Todd MJ, et al. Head impulse test in unilateral vestibular loss. Vestibulo-ocular reflex and catch up saccades. Neurology. 2008;70:454–463. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000299117.48935.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aw ST, Halswanter G, Halmagyi GM, et al. Three-dimensional vector analysis of the human vestibuloocular reflex in response to high-acceleration head rotations I. Responses in normal subjects. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:4009–4020. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aw ST, Halmagyi GM, Halswanter G, et al. Three-dimensional vector analysis of the human vestibuloocular reflex in response to high-acceleration head rotations II. Responses in subjects with unilateral vestibular loss and selective semicircular canal occlusion. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:4021–4030. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]