SUMMARY

Minimally-invasive procedures for parathyroidectomy have revolutionized the surgical treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT). Coexistence of goitre is considered a major contraindication for these approaches, especially if unilateral. A specific advantage of video-assisted parathyroidectomy (VAP) compared to other endoscopic techniques is the possibility to combine it with thyroidectomy when necessary and when the selection criteria for video-assisted thyroidectomy (VAT) are met. We evaluated the role of VAP in a region with a high prevalence of goitre. The medical records of all patients who underwent parathyroidectomy and concomitant thyroid resection in our Division, between May 1998 and June 2012, were reviewed. Patients who underwent VAP and concomitant VAT were included in this study. Overall, in this period, 615 patients were treated in our Division for pHPT and 227 patients (36.9%) underwent concomitant thyroid resection. Among these, 384 patients were selected for VAP and 124 (32.3%) underwent concomitant VAT (lobectomy in 26 cases, total thyroidectomy in 98). No conversion to conventional surgery was registered. Mean operative time was 66.6 ± 43.6 min. Transient hypocalcaemia was observed in 42 cases. A transient recurrent nerve lesion was registered in one case. No other complications occurred. Final histology showed parathyroid adenoma in all but two cases of parathyroid carcinoma, benign goitre in 119 cases and papillary thyroid carcinoma in the remaining 5 patients. After a mean follow-up of 33.2 months, no persistent or recurrent disease was observed. In our experience, a video-assisted approach for the treatment of synchronous thyroid and parathyroid diseases is feasible, effective and safe at least considering short-term follow-up.

KEY WORDS: Video-assisted parathyroidectomy, Endemic goitre, Parathyroid surgery, Video-assisted thyroidectomy

RIASSUNTO

L'introduzione delle tecniche di paratiroidectomia mini-invasiva ha rivoluzionato il trattamento chirurgico dell'iperparatiroidismo primitivo (pHPT). La presenza di un gozzo voluminoso è stata generalmente considerata una delle principali controindicazioni agli approcci mini-invasivi di paratiroidectomia, soprattutto se unilaterali. Uno dei principali vantaggi della paratiroidectomia video-assistita (VAP) è la possibilità di eseguire resezioni tiroidee concomitanti, laddove i criteri di inclusione delle tiroidectomia video-assistita (VAT) siano rispettati. In questo studio abbiamo valutato il ruolo della VAP in una regione di endemia gozzigena. Sono state analizzate tutte le cartelle cliniche dei pazienti sottoposti a paratiroidectomia e concomitante tiroidectomia tra Maggio 1998 e Giugno 2012, presso la nostra Unità Operativa. Sono stati inclusi nello studio tutti i pazienti sottoposti a VAP e concomitante VAT. Durante il periodo considerato, su un totale di 615 pazienti trattati per pHPT, 227 casi (36,9%) sono stati sottoposti a concomitante tiroidectomia. Tra questi, 384 pazienti sono stati selezionati per l'approccio video-assistito. In 124 di questi 384 pazienti (32,3%) è stata associata una VAT: una lobectomia in 26 casi e una tiroidectomia totale in 98 casi. La conversione a chirurgia convenzionale non si è resa necessaria in nessun caso. Il tempo operatorio medio è stato 66,6 ± 43,6 min. In quarantadue casi è stata rilevata un'ipocalcemia transitoria. Nella serie riportata è stato osservato un solo caso di lesione ricorrenziale transitoria. L'esame istologico definitivo ha dimostrato 122 adenomi paratiroidei, 2 casi di carcinoma paratiroideo, uno struma colloideo-cistico in 119 casi e un carcinoma papillare della tiroide in 5 casi. A un follow-up medio di 33,2 mesi, non sono stati registrati casi di persistenza né di recidiva di malattia. I risultati del nostro studio dimostrano che, in casi selezionati, l'approccio video-assistito rappresenta un'opzione terapeutica efficace nel trattamento di una significativa percentuale di pazienti affetti da pHPT associato a gozzo.

Introduction

The last two decades have seen a revolution in the field of surgical treatment of sporadic primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT), at least in part due to advances in technology 1 2. The evolution of preoperative imaging studies, the availability of the quick parathyroid hormone assay (qPTHa) and the introduction of cervicoscopy gave great impulse to the application of several variants of minimally-invasive techniques for parathyroidectomy. To date, a minimally-invasive approach to parathyroidectomy emerged as a valid and validated option to treat selected cases of sporadic pHPT, at least in referral centres 3, and are assuming an increasingly important role 4.

Nonetheless, the diffusion of the minimally-invasive parathyroidectomy has resulted in several controversies regarding the indications for these approaches 5. One of the criticisms regards the role of minimally-invasive parathyroid access in the treatment of a concomitant thyroid pathology 6-8, which could represent a relevant limit for the diffusion of these approaches, especially in regions with a high prevalence of goitre. Indeed, in countries with endemic goitre, concomitant thyroid disease is found in 35-78% of patients with pHPT 7.

Miccoli 9 first described video-assisted parathyroidectomy (VAP), and in 1998 our department adopted the procedure 10. Early after its first description, this technique encountered large, worldwide acceptance 10-15 as it is easy to reproduce in different surgical settings. Indeed, it reproduces all the steps of a conventional procedure, with the endoscope representing a tool that allows performing the same operation through a smaller skin incision 10. Thanks to its central access, VAP, in selected cases, allows performing bilateral neck exploration and thyroid resection when necessary through the same central access 3 10 16.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of VAP in a region with a high prevalence of goitre.

Materials and methods

The medical records of all patients who underwent parathyroidectomy for pHPT and a concomitant thyroid lobectomy (TL) or total thyroidectomy (TT), between May 1998 and June 2012, at our institution were reviewed. Patients who underwent VAP and concomitant video-assisted thyroidectomy (VAT) were included in this study. Demographic, clinical, surgical, pathologic and follow-up data of these patients were evaluated. Statistical analysis was performed using a commercially available software package (SPSS 10.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill). The χ2 test was used for categorical variables, and a t test was used for continuous variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Preoperative work-up

Preoperative high-resolution ultrasound (US) and 99mTcsestamibi (MIBI) scans were performed in all patients with sporadic pHPT to localize hyperfunctioning glands. All patients had normal renal function (serum creatinine value ranging from 0.7 to 1.2 mg/dl).

Indications

Ideal candidates for VAP are those with sporadic pHPT in whom a single adenoma is suspected basing on preoperative MIBI-scan and ultrasonography. Parathyroid adenomas larger than 3 cm in their maximum diameter should not be selected for VAP, because a difficult dissection can lead to dangerous capsular rupture. Patients with concomitant nodular goitre requiring surgical removal can be selected for VAP if the inclusion criteria for the video-assisted thyroidectomy (VAT) are respected 10 17. Basing on the surgeons' experience, in selected cases, patients with previous contralateral neck surgery or intrathymic/retrosternal adenomas can be selected for VAP. In case of suspected multiple gland disease, a video-assisted bilateral exploration can be planned.

Intraoperative-PTH (IOPTH) monitoring

All patients underwent IOPTH monitoring. Blood samples were collected peripherally pre-incision (preoperative baseline concentration – PTH), pre-excision (after dissection and just before clamping the blood supply of the suspected affected gland – PTH) and at 10 min (PTH-10) and 20 min (PTH-20) after gland excision. A point of care chemiluminescence immunoassay system (Stat-IntraOperative-intact PTH – Future Diagnostics, Wijchen, The Netherlands) was used for IOPTH measurements and set up in the recovery room. Blood specimens were collected and analyzed following the manufacturer's indications 18.

Surgical technique

The surgical technique we use has been previously described elsewhere in detail 19. The patient, under general or loco-regional anaesthesia with cervical block 20 21, is positioned supine with the neck in slight extension. A small (1.5 cm) horizontal skin incision is made between the cricoid cartilage and the sternal notch, in the midline. The cervical linea alba is opened as far as possible. The technique is completely gasless. The endoscope (5 mm, 30°) and the dedicated small surgical instruments are introduced through the skin incision without any trocar utilization (Fig. 1). After identifying the inferior laryngeal nerve in the involved side, a targeted exploration is usually carried out to identify the abnormal gland. The magnification (2-3 folds) of the endoscope permits a easy identification of the nerve and the parathyroid glands, if the principles of blunt and bloodless dissection are respected. In case of suspicion of multiglandular disease, bilateral parathyroid exploration can be accomplished. The gland should not be grasped, in order to avoid any capsular rupture. After cutting the pedicle, the adenoma is extracted through the skin incision.

Fig. 1.

Video-assisted parathyroidectomy: two small conventional retractors are used to medially retract the thyroid lobe and laterally retract the strap muscles to maintain the operative space. The endoscope (5 mm, 30°) and dedicated small surgical instruments are then introduced through the skin incision without any trocar utilization.

When video-assisted thyroidectomy is required, dissection of the thyroid gland is safely performed under endoscopic vision according to the technique previously described 17-19.

Follow-up schedule

During follow-up, calcium levels combined with intact PTH (iPTH) values were examined at 1, 3 and 6 months after the operation, and the following classification criteria for postsurgical resection outcome at 6 months were used:

group 1: cured patients/operative success: normal or low serum calcium levels for at least 6 months after parathyroidectomy; group 2 – patients with disease persistence/operative failure: persistent hypercalcaemia and elevated iPTH levels (> 65 pg/ml; 6.89 pmol/l) within 6 months after surgery.

Results

Between May 1998 and June 2012, at our institution 615 patients underwent surgery for primary HPT. Among these, 227 patients (36.9%) underwent concomitant thyroid resection.

Three hundred and eighty four patients with PHPT who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were selected for VAP. Among these, concomitant VAT was carried out in 124 patients (32.3%): 105 females and 19 males, with a mean age of 60.8 ± 10.3 years (range: 38-84). Indications for concomitant thyroid resection were indeterminate nodule within bilateral goitre in 31 cases and multinodular goitre (MNG) with compressive symptoms in the remaining 93 cases. The mean diameter of the dominant nodule of the 93 cases of MNG was 20.3 ± 9.8 mm (range: 2-46 mm). Video-assisted TL was performed in 26 cases and video-assisted TT in 98 cases. No conversion to conventional surgery was necessary. The mean operative time of all procedures was 66.6 ± 43.6 min (range: 30-175). In particular, the mean operative time of VAP associated to video-assisted TL was 63.19 ± 38.1 min (range: 30- 170); the parathyroid lesion was ipsilateral to the side of the thyroid lobectomy in 19 cases and contralateral in the remaining 7 cases. The mean operating time for VAP associated with video-assisted TT was 68.27 ± 32.5 min (range: 40-175). Transient hypocalcaemia was observed in 42 cases (32.8%), transient recurrent lesion in one case (0.8%). No other complications occurred. Mean postoperative hospital stay was 3.4 ± 1.7 days (range: 3-7). Most patients (93%) considered the cosmetic result as excellent as evaluated by a verbal response scale (Fig. 2a-b).

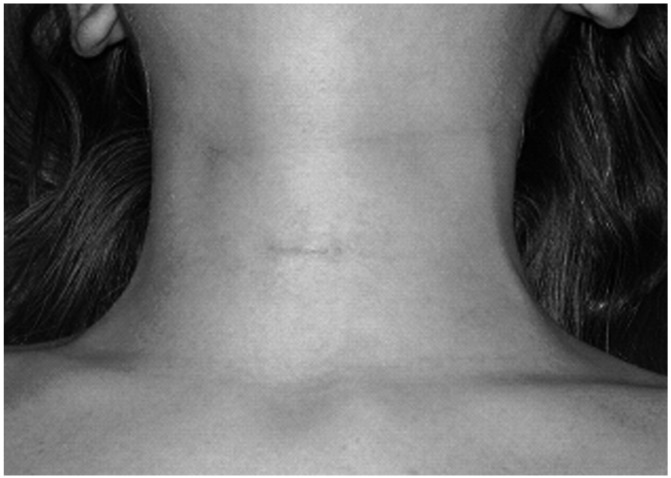

Fig. 2a.

Cosmetic result of a VAP at two weeks after surgery.

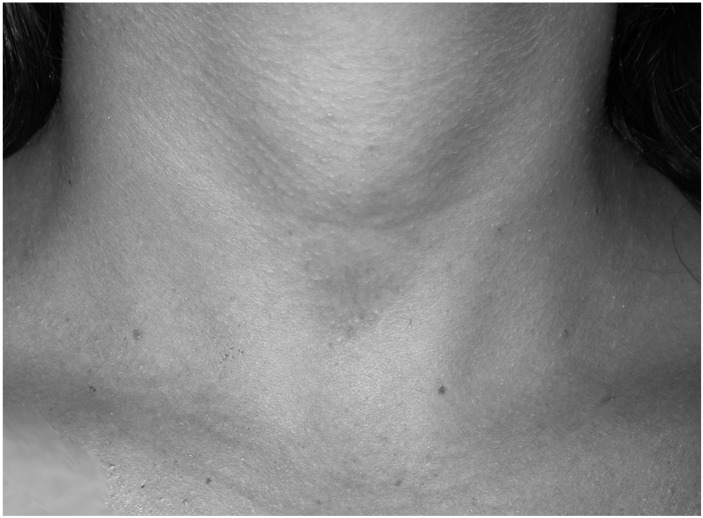

Fig. 2b.

Cosmetic result of a VAP at six months after surgery.

Final histology showed parathyroid adenoma in all but two cases of parathyroid carcinomas.

In particular, in these latter two cases, no signs and/or suspicions of malignancy were present on the basis of pre-operative evaluation; in both cases simultaneous videoassisted total thyroidectomy for a concomitant bilateral thyroid disease was performed.

Final histology of thyroid specimens revealed benign goitre in 119 cases and papillary thyroid carcinoma in 5 cases. The preoperative cytological examination of the five cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma was consistent with indeterminate nodules. After a mean follow-up of 33.2 ± 20.0 months (range: 3-110), no persistent recurrent parathyroid or thyroid disease was observed.

Discussion

The results of VAP in terms of cure and complication rates are similar and rival those of conventional surgery. This has been extensively demonstrated in the international literature 3 4 16, and it is also confirmed in our personal experience 10 18 19.

Some criticisms about the technical aspects for MIVAP have concerned the operating time. However, it has been demonstrated in large retrospective series 10 14 as well as in small comparative, randomized trials 3 22 that the operating time does not represent a limit. A prospective, randomized, small comparative study (level II evidence) showed that the operating time for MIVAP was significantly shorter than conventional bilateral exploration and similar to open minimally-invasive parathyroidectomy 22.

In addition, in our overall experience with exclusive VAP and IOPTH the mean operating time was 42.6 ± 18.1 min (range: 15-95).

Besides its reproducibility, VAP also seems to offer significant advantages over conventional surgery in terms of patient satisfaction with the cosmetic result and postoperative recovery 3. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that in selected cases of pHPT, VAP is curative and safe considering short- and medium-term outcome and complications 10-14 22 23.

The association between benign and malignant thyroid disease with pHPT has been previously described 5-8. Indeed, the presence of concomitant thyroid disease has been reported in 15%-70% of patients with pHPT 24 25. In a surgical series of 51 patients with pHPT, Kösem described 43 cases (84.3%) of coexistent thyroid diseases. Among these, 9 patients (17.6%) had papillary thyroid cancer 26.

The association between pHPT and goitre seems to be more much relevant in areas with iodine deficiency. It has been reported that in an endemic goitre region, 67 of 137 patients with PHPT (49%) had concomitant thyroid disease 7.

In a large retrospective analysis involving a population living in a geographical area with an average-mild iodine deficiency, such as the mixed Italian regions, a total of 124 of 241 patients (51.5%) with pHPT showed concomitant thyroid disorders 27.

It has been pointed out that a head and neck endocrine surgeon needs to be aware of the possible coexistence of thyroid and parathyroid disease so that, when encountered, they can be safely and effectively managed in a single procedure 24 25. However, some authors have argued that concomitant thyroid disease requiring surgical management represents an exclusion criteria for minimally-invasive parathyroidectomy 5 6. Perrier 5 reported that 17% of patients referred to parathyroidectomy were considered ineligible for localized parathyroid surgery because of a coexisting thyroid pathology. However, a relevant advantage of central access is the possibility to perform thyroid resection, even bilateral, when necessary. This introduces an important difference when compared to other minimally-invasive techniques, as conversion to a conventional approach is usually required when bilateral thyroid resection is needed 28. Because of the high prevalence of multinodular goitre in some countries, the central approach of VAP can allow experienced surgeons to increase the number of patients eligible for a video-assisted procedure. Indeed, in our experience in a region of high prevalence of goitre in Italy, the video-assisted approach was successful accomplished in the treatment of both parathyroid and thyroid disease during the same procedure in a significant percentage of patients (32.3%).

Moreover, concomitant thyroid diseases with pHPT may result in more difficult preoperative localization of the pathological parathyroid gland. Indeed, in these cases, one of the main problems is the accuracy of preoperative imaging studies. It has been reported that the coexistence of pHPT and thyroid disease may reduce the sensitivity of sestaMIBI from 81% to 75%, and of US from 73% to 55% 29. However, the combined use of sestaMIBI and US seems to be more effective in patients with pHPT for localization of an enlarged parathyroid gland even in the case of concomitant thyroid disease 29. This would make it possible to perform a focused parathyroidectomy in the most of patients suffering from pHPT even in an endemic goitre region 7.

Moreover, it might be stressed that even if preoperatively, well-documented single adenoma is a prerequisite for any type of focused parathyroidectomy 1 30, the concept that preoperative localization studies are mandatory when performing a minimally-invasive approach remains valid only for procedures that imply a unilateral approach. Among these, the lateral approach (VAP-LA) described by Henry which is the most diffuse, has been shown to be effective and safe, with a minimal complication rate 31. Nonetheless, due to its unilateral approach, the rate of contraindications for VAP-LA appears fairly high (43%) compared to that of large series of VAP 23. This may depend on the need of stricter eligibility criteria, due to the unilaterality of the approach, which implies the strong demonstration of a single enlarged parathyroid gland on preoperative imaging studies and excludes bilateral thyroid disease. The main technical limitation of the technique is, indeed, that a unilateral approach prevents the possibility to accomplish bilateral exploration when necessary without conversion to an open conventional procedure 28 30 31.

On the other hand, a relevant merit of VAP is the possibility of performing bilateral neck exploration when necessary through the same central access. This characteristic in part explains the lack of conversion in the present series and the very low conversion rate generally reported for VAP 10 16. Moreover, the possibility of performing a bilateral neck exploration produces two main effects on the restrictive inclusion criteria. First, at least from a theoretical point of view, VAP can be performed if IOPTH monitoring is not available or in the case of inadequate preoperative localization, given the ability to explore all parathyroid sites through this approach 10 23 32.

In our experience in an endemic goitre area, 62.4% of patients with PHPT were eligible for VAP. The possibilities given by central access allowed us to treat a significant percentage of patients with concomitant thyroid disease who fulfilled the indication criteria of VAT. No conversion to conventional surgery was necessary and no definitive complications occurred. After a mean follow-up of 33.2 months, no persistent or recurrent parathyroid or thyroid diseases was observed.

Conclusions

When selection criteria are followed, the treatment of synchronous thyroid and parathyroid disorders can be accomplished using a minimally-invasive procedure. In our experience, a video-assisted approach is feasible, effective and safe for the treatment of synchronous thyroid and parathyroid disorders, at least considering short-term follow-up.

References

- 1.Lee JA, Inabnet WB., 3rd The surgeon's armamentarium to the surgical treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:130–135. doi: 10.1002/jso.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duh QY. Surgical approach to primary hyperparathyroidism (bilateral approach) In: Clark OH, Duh QY, editors. Textbook of endocrine surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1997. pp. 357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Traini E, et al. Video-assisted minimally invasive parathyroidectomy: benefits and longterm results. World J Surg. 2009;33:2266–2281. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9931-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergenfelz AOJ, Hellman P, Harrison B, et al. Positional statement of the European Society of Endocrine Surgeons (ESES) on modern techniques in pHPT surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:761–764. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perrier ND, Ituarte PHG, Morita E, et al. Parathyroid surgery: separating promise from reality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1024–1029. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sidhu S, Campbell P. Thyroid pathology associated with primary hyperparathyroidism. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:285–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2000.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prager G, Czerny C, Ofluoglu S, et al. Impact of localization studies on feasibility of minimally invasive parathyroidectomy in an endemic goiter region. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:541–548. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01897-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihai R, Barczynski M, Iacobone M, et al. Surgical strategy for sporadic primary hyperparathyroidism an evidencebased approach to surgical strategy, patient selection, surgical access, and reoperations. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:785–798. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miccoli P, Bendinelli C, Conte M, et al. Endoscopic parathyroidectomy by a gasless approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1998;8:189–194. doi: 10.1089/lap.1998.8.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellantone R, Raffaelli M, Crea C, et al. Minimallyinvasive parathyroid surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:207–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dralle H, Lorenz K, Nguyen-Thann P. Minimally invasive video-assisted parathyroidectomy: selective approach to localized single gland adenoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;384:556–562. doi: 10.1007/s004230050243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mourad M, Ngongang C, Saab N, et al. Video-assisted neck exploration for primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1112–1115. doi: 10.1007/s004640090017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hallfeldt KKJ, Trupka A, Gallwas J, et al. Minimally invasive video-assisted parathyroidectomy. Early experience using an anterior approach. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:409–412. doi: 10.1007/s004640090042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenz K, Miccoli P, Monchik JM, et al. Minimally invasive video-assisted parathyroidectomy: multiinstitutional study. World J Surg. 2001;25:704–707. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki S, Fukushima T, Ami H, et al. Video-assisted parathyroidectomy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2002;56(Suppl 1):18s–21. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(02)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berti P, Materazzi G, Picone A, et al. Limits and drawbacks of video-assisted parathyroidectomy. Br J Surg. 2003;90:743–747. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Princi P, et al. Safety of video-assisted thyroidectomy versus conventional surgery. Head Neck. 2005;27:58–64. doi: 10.1002/hed.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Traini E, et al. Intraoperative PTH monitoring during parathyroidectomy: the need for stricter criteria to detect multiglandular disease. Langenbeks Arch Surg. 2008;393:639–645. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M. Encyclopedie Medico-Chirurgicale, Tecniche Chirurgiche – Chirurgia Generale, 46- 465-A. Paris: Elsevier; 2005. Paratiroidectomia mini-invasiva video-assistita; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Modesti C, et al. Video-assisted thyroidectomy under local anesthesia. Am J Surg. 2004;187:515–518. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miccoli P, Barellini L, Monchik JM, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing regional and general anaesthesia in minimally invasive video-assisted parathyroidectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:814–818. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miccoli P, Bendinelli C, Berti P, et al. Video-assisted versus conventional parathyroidectomy in primary hyperparathyroidism: a prospective randomized trial. Surgery. 1999;126:1117–1121. doi: 10.1067/msy.2099.102269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miccoli P, Berti P, Materazzi G, et al. Results of videoassisted parathyroidectomy: single institution's six-year experience. World J Surg. 2004;28:1216–1223. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7638-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beus KS, Stack BC., Jr Synchronous thyroid pathology in patients presenting with primary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentrem DJ, Angelos P, Talamonti MS, et al. Is preoperative investigation of the thyroid justified in patients undergoing parathyroidectomy for hyperparathyroidism? Thyroid. 2002;12:1109–1112. doi: 10.1089/105072502321085207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kösem M, Algün E, Kotan C, et al. Coexistent thyroid pathologies and high rate of papillary cancer in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: controversies about minimal invasive parathyroid surgery. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:568–571. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2004.11679616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dell'Erba L, Baldari S, Borsato N, et al. Retrospective analysis of the association of nodular goiter with primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145:429–434. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1450429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carling T, Udelsman R. Focused approach to parathyroidectomy. World J Surg. 2008;32:1512–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9567-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krausz Y, Lebensart PD, Klein M, et al. Preoperative localization of parathyroid adenoma in patients with concomitant thyroid nodular disease. World J Surg. 2000;24:1573–1578. doi: 10.1007/s002680010280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Assalia A, Inabnet WB. Endoscopic parathyroidectomy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37:871–886. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henry JF, Sebag F, Tamagnini P, et al. Endoscopic parathyroid surgery: results of 365 consecutive procedures. World J Surg. 2004;28:1219–1223. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miccoli P, Berti P, Materazzi G, et al. Endoscopic bilateral neck exploration versus quick intraoperative parathormone assay (qPTH) during endoscopic parathyroidectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:398–400. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]