Abstract

AIM: To investigate the indications for lymph node dissection (LND) in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis was conducted on 124 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) patients who had undergone surgical resection of ICC from January 2006 to December 2007. Curative resection was attempted for all patients unless there were metastases to lymph nodes (LNs) beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament. Prophylactic LND was performed in patients in whom any enlarged LNs had been suspicious for metastases. The patients were classified according to the LND and LN metastases. Clinicopathologic, operative, and long-term survival data were collected retrospectively. The impact on survival of LND during primary resection was analyzed.

RESULTS: Of 53 patients who had undergone hepatic resection with curative intent combined with regional LND, 11 had lymph nodes metastases. Whether or not patients without lymph node involvement had undergone LND made no significant difference to their survival (P = 0.822). Five patients with multiple tumors and involvement of lymph nodes underwent hepatic resection with LND; their survival curve did not differ significantly from that of the palliative resection group (P = 0.744). However, there were significant differences in survival between patients with lymph node involvement and a solitary tumor who underwent hepatic resection with LND and the palliative resection group (median survival time 12 mo vs 6.0 mo, P = 0.013).

CONCLUSION: ICC patients without lymph node involvement and patients with multiple tumors and lymph node metastases may not benefit from aggressive lymphadenectomy. Routine LND should be considered with discretion.

Keywords: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, Lymph node dissection, Lymph node metastases, Postoperative survival

Core tip: The indications for lymph node dissection (LND) in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) are still controversial. Our findings may provide a reference to the criterion for LND in ICC patients. Routine LND should be considered with discretion for ICC patients without lymph node involvement and patients with multiple tumors and lymph node metastases.

INTRODUCTION

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), arising from second order or more peripheral branches of the intrahepatic bile duct, is the second most common primary liver cancer after hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), accounting for 5%-10% of primary malignancies of the liver[1,2]. It is considered a highly malignant neoplasm because it is frequently associated with lymph node (LN) involvement, intrahepatic metastasis, and peritoneal dissemination[3,4].

Hepatic resection remains the most effective therapy for patients with ICC. LN status, a definite prognostic factor in oncologic surgery, significantly affects long-term survival, as reported by the tumor staging system of the International Union Against Cancer[5]. Regional lymph node dissection (LND) is already a standard procedure, in combination with hepatic resection, for carcinoma arising from the extrahepatic bile duct [6,7]. Although LN metastasis is considered to be the most important prognostic factor for survival of ICC patients[8,9], the indications for, and roles of, LND in patients with ICC are still subject to discussion. It is important to define the role of LND because it is a modifiable factor by a surgeon during hepatic resection, but no clear guidelines yet exist. Although some consider the standard surgical procedure for ICC is hepatectomy combined with extensive nodal dissection, not all centers support routine LND[10]. Some institutions have reported selective LND and limited application of this procedure[11]. Concerns remain about routine performance of LND in patients with liver tumors because it is reportedly associated with an increased operative risk compared with hepatic resection alone[3,12].

We performed a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients at our hospital to examine the outcomes of ICC patients undergoing hepatic resection. We assessed the influence of LND on patient survival to clarify the indications for this procedure in surgical treatment of ICC, especially when LN metastases are absent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Altogether, 152 patients were diagnosed with ICC and underwent surgical dissection at Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China) from January 2006 to December 2007. Twelve patients only underwent laparotomy and biopsy because they had peritoneal dissemination. The remaining 140 patients were included in the present study. Among them, only 124 (88.6%) were followed sufficiently to allow subsequent data analysis, and the remaining 16 patients were lost to follow-up. The reasons for their loss to follow-up are unknown but include inability to contact them and possibly death. ICC was defined as adenocarcinoma arising from second order or more distal branches of the intrahepatic bile ducts[10,11]. Patients with combined HCC and cholangiocarcinoma or bile duct cystadenocarcinoma were excluded from this study. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in the study according to the requirements of this committee.

Preoperative investigations

Resectability of the ICCs was assessed by ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before a decision to perform surgery was made. Liver function was evaluated according to the Child-Pugh classification. Patients aged over 60 years were routinely subjected to formal cardiopulmonary evaluation and evaluation of their general condition preoperatively. Resection criteria were constant over the study period and included the number of resectable tumors, presence or absence of tumor thrombi and gross metastatic foci, and adequate hepatic functional reserve, as described in our previous study[13]. Patients were deemed to have resectable disease only if the tumor could be completely removed while preserving a sufficient functional liver remnant with adequate vascular inflow and hepatic venous outflow. If the estimated liver resection volume exceeded 60% of the whole liver as calculated by CT, preoperative percutaneous transhepatic portal embolization was performed on the liver segment to be resected, in order to induce compensatory hypertrophy of the future remnant liver.

Surgical procedures and definitions of parameters

Patients with peripheric ICC underwent hepatectomy while patients with hilar ICC underwent hemihepatectomy or trisectionectomy. Bisectionectomy or more was defined as a major hepatectomy. Sectionectomy or less was defined as a minor hepatectomy. Extended hepatectomy was defined as removal of 5 or more segments. Liver resection was performed using finger fracture and clamp crushing with intermittent Pringle’s maneuver at room temperature. Initial intraoperative assessment consisted of careful examination and palpation of the hepatic hilum and hepatoduodenal ligament by the chief surgeons to detect any enlarged LNs. Any enlarged LN was considered suspicious for metastases. Because of the patient’s old age, poor general condition, peripheral tumor location in the liver and the known increased risk of adding this procedure to hepatic resection, prophylactic LND was not performed in patients in whom LN involvement had not been identified by preoperative imaging (CT and MRI) and intraoperative assessment. These patients were clinically defined as not having LN metastases. If LN metastases were clinically recognized, regional LND was performed. However, curative resection was not attempted when there were metastases to LNs beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament. Regional LND included complete excision of soft tissue and LNs at the hepatic hilum, hepatoduodenal ligament, posterior to the upper portion of the pancreatic head, and common hepatic artery stations. The extent of LND was similar for right- and left-sided tumors, except that dissection of LNs along the lesser curvature of the stomach was added for tumors located in the left lobe of the liver.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was classified by gross appearance, as proposed by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan[14]. These types include mass-forming (MF), periductal infiltrating (PI), and intraductal growth (IG), with mixed types being expressed as MF + PI or MF + IG. Tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging of tumors followed the guidelines of the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against Cancer. In this study, multiple tumors were defined as more than one involved node (including micrometastases that were discovered only on pathological examination); tumor size referred to the maximum tumor diameter; resection of three or more hepatic segments was classified as major liver resection; and resection of one or two hepatic segments as minor liver resection. Curative resection was defined as negative surgical margins on microscopic examination of the resected specimen, surgical findings of macroscopic absence of intrahepatic metastases in the residual liver, and absence of visible abdominal dissemination.

Follow-up

Clinical data for all patients were collected retrospectively. After resection, follow-up included routine blood tests, physical examination, and abdominal ultrasonography every 3 mo postoperatively for the first 2 years and twice a year thereafter at our hospital. Suspected recurrences were confirmed by CT or MRI. If the patients were unable to attend for these assessments, they were followed by telephone or letter yearly.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of surgery. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of the first clinically documented disease recurrence. Comparison between groups was examined by the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The OS and RFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess differences. All statistical analyses were performed with software package SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Clinicopathological characteristics

We continued follow-up of patients until death or the final date of the study, June 30, 2012. Data for analysis were available for 124 patients, including 96 men and 28 women with a median age of 56 years (range, 28-79). According to the Union for International Cancer Control TNM classification, 65 patients had stage I disease, 8 had stage II, 51 had stage III, and none had stage IV. As for liver function as defined by the Child-Pugh classification, 113 patients had class A, 11 had class B, and none had class C.

Of the 124 patients, 65 underwent major liver resection and 59 underwent minor resection. We performed additional procedures in 67 patients (Table 1). Surgical complications occurred in eight patients, including biliary leakage in three, subphrenic infection in two, liver abscess in one, bowel obstruction in one, and bleeding in one. LND did not increase the rates of postoperative complications or death.

Table 1.

Operative procedures for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

| Operative modality | n |

| Hepatic resection (n = 124) | |

| Major resection (n = 65) | |

| Partial hepatectomy | 38 |

| Right trisectionectomy | 1 |

| Left trisectionectomy | 2 |

| Extended left hemihepatectomy | 2 |

| Right hemihepatectomy | 4 |

| Left hemihepatectomy | 15 |

| Central bisectionectomy | 3 |

| Minor resection (n = 59) | |

| Partial hepatectomy | 37 |

| Right anterior sectionectomy | 4 |

| Right posterior sectionectomy | 3 |

| Left lateral sectionectomy | 8 |

| Bisegmentectomy | 7 |

| Additional procedures (n = 67) | |

| Spleen resection | 2 |

| Gallbladder resection | 12 |

| Lymph node dissection | 53 |

Of the 124 patients, 10 had microscopically positive resection margins (palliative resection group). Of the 114 patients who underwent resection with curative intent, 61 did not undergo LND [LND (-) group]. Of the 53 patients who underwent LND, 42 did not have LN metastases [LND (+) LN (-) group] and 11 did [LND (+) LN (+) group]. In all, 318 LNs were analyzed histologically. The median number of retrieved LNs was 6 (1-16). We found LN metastases in the hepatoduodenal ligament in 10 patients and along the common hepatic artery in three patients. We found a single LN metastasis in nine patients.

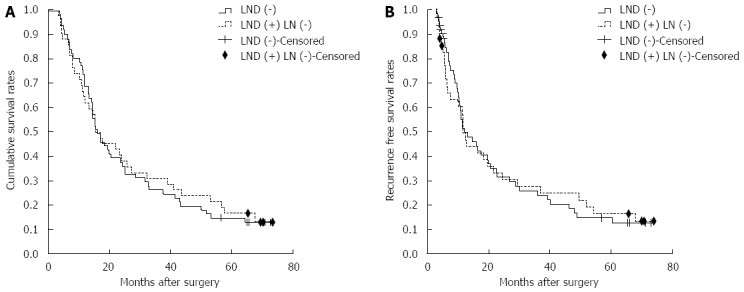

OS and RFS of patients who did not undergo LND and those who did and had no LN metastases detected

The clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients in the LND (-) and LND (+) LN (-) groups are summarized in Table 2. There were no significant differences between these groups. Figure 1 presents the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing patients in the LND (-) group with those in the LND (+) LN (-) group. There were no differences in their survival curves (P = 0.822). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 69%, 26% and 15%, respectively, in the LND (-) group and 64%, 31%, and 17%, respectively, in the LND (+) LN (-) group. Recurrence occurred in 69 of these patients (67.0%). RFS rates at 1-, 3-, and 5-year were 53%, 25%, and 15%, respectively, in the LND (-) group and 52%, 29%, and 17%, respectively, in the LND (+) LN (-) group. There was no significant difference in RFS between the LND (-) and LND (+) LN (-) groups (P = 0.970) (Figure 1). The sites of recurrence are shown in Table 3. The most common recurrence site was the remnant liver. Among the 61 patients who did not undergo LND, the initial recurrence site was LNs in nine. Recurrence in LNs occurred in four patients who had undergone LN dissection.

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients in the lymph node dissection (-) and lymph node dissection (+) lymph node (-) groups

| Factor |

LND (-) |

LND (+) LN (-) |

P value |

| n = 61 | n = 42 | ||

| Gender | 1.000 | ||

| Female | 13 | 9 | |

| Male | 48 | 33 | |

| Age | 0.516 | ||

| ≤ 60 | 44 | 27 | |

| > 60 | 17 | 15 | |

| Viral hepatitis | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 36 | 24 | |

| No | 25 | 18 | |

| Cirrhosis | 0.694 | ||

| Yes | 28 | 21 | |

| No | 33 | 21 | |

| Child-Pugh class | 0.735 | ||

| A | 55 | 39 | |

| B | 6 | 3 | |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 0.553 | ||

| ≤ 37 | 30 | 18 | |

| > 37 | 31 | 24 | |

| Histologic differentiation | 0.498 | ||

| Well or Moderate | 44 | 33 | |

| Poor | 17 | 9 | |

| Gross type | 0.433 | ||

| MF | 43 | 28 | |

| PI | 4 | 7 | |

| IG | 5 | 2 | |

| MF + PI | 5 | 4 | |

| MF + IG | 4 | 1 | |

| Tumor number | 0.510 | ||

| Single | 45 | 28 | |

| Multiple | 16 | 14 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.318 | ||

| < 5 | 33 | 18 | |

| ≥ 5 | 28 | 24 | |

| TNM classification | 0.080 | ||

| Early (stage I, II) | 47 | 25 | |

| Advanced (stage III, IV) | 14 | 17 | |

| Width of resection margin (cm) | 0.229 | ||

| < 1 | 33 | 17 | |

| ≥ 1 | 28 | 25 | |

| Surgical procedure | 0.153 | ||

| Major hepatectomy | 41 | 22 | |

| Minor hepatectomy | 20 | 20 | |

CA19-9: Carbohydrate antigen 19-9; IG: Intraductal growth; LN: Lymph node; LND: Lymph node dissection; MF: Mass-forming; PI: Periductal infiltrating; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

Figure 1.

Overall survival and recurrence-free survival curves of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients without lymph node involvement. A: Survival curves of patients in the lymph node dissection (LND) (-) and LND (+) LN (-) groups. There is no significant survival difference between the two groups (P = 0.822). The censored represented the cases who were still alive at the endpoint; B: Recurrence-free survival curve of patients in LND (-) and LND (+) LN (-) groups. There is no significant survival difference between the two groups (P = 0.970). The censored represented the cases who were still alive at the endpoint or died for other reasons instead of tumor recurrence.

Table 3.

Sites of initial recurrence in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients after resection with curative intent

| Site of initial recurrence | LND (-) | LND(+) LN (-) | LND(+) LN (+) |

| n = 61 | n = 42 | n = 11 | |

| Liver, lymph nodes | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Liver, lung | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Liver | 25 | 18 | 6 |

| Lymph nodes | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Peritoneum | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Wound site | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bone | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Lung | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total No. of recurrence | 42 | 27 | 11 |

LN: Lymph node; LND: Lymph node dissection.

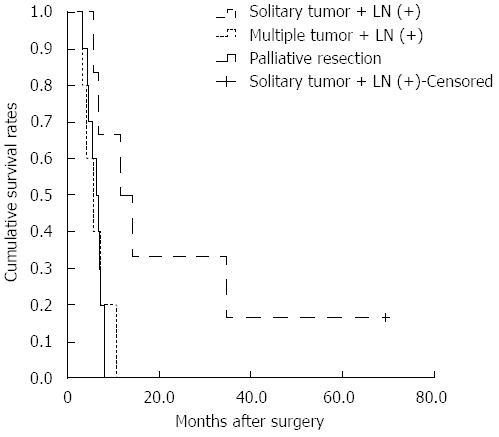

OS of patients in the palliative resection group and patients who underwent LND and had positive LNs

Five patients with LN involvement and multiple tumors underwent hepatic resection with LND. As for the subgroup analysis, the median survival times of the palliative resection group and patients with LN involvement and multiple tumors were 6.0 mo and 5.5 mo, respectively (Figure 2). There were no significant survival differences between the two groups (P = 0.744). However, there was a significant difference between patients with a solitary tumor and LN involvement who underwent hepatic resection with LND and the palliative resection group (P = 0.013), and their median survival times were 12 mo and 6.0 mo, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival curves of patients in the palliative resection and lymph node dissection (+) lymph node (+) groups. There are significant differences between the palliative resection group and patients with lymph node (LN) involvement and a solitary tumor (P = 0.013). There are no significant differences between the palliative resection group and patients with LN involvement and multiple tumors (P = 0.744).

DISCUSSION

Although curative resection provides the only chance of long-term survival for patients with ICC, the prognosis after surgical resection remains poor because this tumor exhibits aggressive invasion locally and frequently metastasizes, tending especially to spread via the lymphatic system[3,15-25]. The rate of perihepatic LN positivity detected at surgery reportedly ranges from 36% to 62%[3,15-25]. In our current study of 53 patients who underwent regional lymphadenectomy, the incidence of LN metastasis was 20.8% (11/53), which is slightly lower than those reported in previous studies. The most common site of LN metastases was the hepatoduodenal ligament (10/11).

Many investigators have used multivariate analysis to determine useful prognostic factors for ICC after surgical resection in recent 5 years (Table 4)[8,9,26-37]. According to these reports, potentially significant prognostic factors include multiple tumors, LN metastasis, serum CA 19-9 level, vascular invasion, tumor size, histological grade, intrahepatic metastases, histological grade, and resection margin. LN metastasis was confirmed to be one of the most significant independent prognostic factors for patients with ICC. Although LN metastasis was considered a significant prognostic factor, whether routine LND should be adopted is still controversial.

Table 4.

Selected published series of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients after resection

| Author | Year | Cases | Prognostic factors | Median survival time | 5-yr survival rate | Routine LND |

| Ribero et al[8] | 2012 | 434 | LN metastases | 33 | 32.90% | No |

| Multiple tumors | ||||||

| CA19.9 level | ||||||

| de Jong et al[9] | 2011 | 449 | Tumor number | 27.3 | 30.7 | No |

| Vascular invasion | ||||||

| LN metastasis | ||||||

| Saxena et al[26] | 2010 | 88 | CA 19.9 level | 33 | 28 | No |

| Clinical stage | ||||||

| Histological grade | ||||||

| LN metastases | ||||||

| Ercolani et al[27] | 2010 | 72 | LN metastasis | 57.1 | 48 | Yes |

| Blood transfusion | ||||||

| Cho et al[28] | 2010 | 63 | Old age | Not available | 31.8 | Yes |

| CA19-9 level | ||||||

| LN metastasis | ||||||

| Narrow resection margin | ||||||

| Shirabe et al[29] | 2010 | 60 | Lymphatic invasion index | Not available | 30.6 | No |

| Histological grade | ||||||

| Guglielmi et al[30] | 2009 | 81 | LN metastasis | 40 | 20 | Not available |

| Vascular invasion | ||||||

| Tamandl et al[31] | 2009 | 93 | Lymph node ratio | 25.5 | Not available | No |

| Choi et al[37] | 2009 | 64 | LN metastasis | 39 | 39.5 | No |

| Shimada et al[32] | 2009 | 104 | Intrahepatic metastases | 25 | 37 | No |

| LN metastasis | ||||||

| Yedibela et al[33] | 2009 | 67 | Resection margin | 26 | 27 | No |

| LN metastasis | ||||||

| Blood transfusion | ||||||

| Nakagohri et al[34] | 2008 | 56 | Intrahepatic metastasis | 22 | 32 | Not available |

| Uenishi et al[35] | 2008 | 133 | Intrahepatic metastasis | 18.4 | 29 | Yes |

| LN metastases | ||||||

| Tumor at the margin | ||||||

| Shimada et al[36] | 2007 | 57 | LN metastasis | 62 | 56.8 | No |

LN: Lymph node; LND: Lymph node dissection; ICC: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

It is unclear whether prophylactic clearance of the route of LN metastasis improves survival. Ribero et al[8] reported that LN metastases and multiple tumors are associated with decreased survival rates. Lymphadenectomy should be considered for all patients according to its theoretical potential to improve long-term survival. LND for nodal metastases has reportedly resulted in a few long-term survivors[38,39]. But some authors have reported that extended LN dissection in patients with ICC does not seem to offer any advantage without control of liver metastases, because most recurrences are in the liver[3,40].

In the current study, we showed that patients who did not undergo LND and those who did, but had negative LNs, had similar survival (1-year: 69% vs 64%; 3-year: 26% vs 31%; 5-year: 15% vs 17%, P = 0.822). These findings suggest that LND does not improve the survival significantly in LN negative patients. The commonest recurrence pattern was intrahepatic, which is similar to other reported findings[5,25,41,42]. We also found no statistically significant difference in RFS between patients who did and did not undergo LND (P = 0.970). It seems that LND does not improve the prognosis because it has no effect on liver metastases.

Prophylactic LND has been advocated to prevent LN recurrence, not only because there can be microscopic LN metastases around the perihepatic LNs, but also because it allows removing a frequent site of recurrence. Among the 61 patients who did not undergo LND, three developed LN recurrence as the primary recurrence site. The chance of benefiting from LND seems to be only about 3/61 (4.9%) of all patients with ICC. Choi et al[37] found that the patients who underwent LND but had negative LDs appear to show slightly worse survival than LND (-) group in the earlier time of the follow-up period, although it was not statistically significant because of the small sample size. Thus, prophylactic LND may be not beneficial to the clinically LD negative patients.

One might question the reliability of our intra-operative LN examination and indications for lymphadenectomy. For patients who had not undergone LN dissection, the N status cannot be ascertained. Clearly, some patients have microscopic nodal involvement that is beyond detection by conventional radiographic imaging or even direct palpation. Some authors have advocated routine lymphadenectomy for all patients undergoing hepatic resection as a staging procedure[8,9,40,43]. However, clinical assessment of LN negativity without histopathologic confirmation appears to be associated with a small risk of subsequent LN metastases. Grobmyer et al[44] stated that the incidence of truly occult metastatic disease to perihepatic LNs is low in patients with primary and metastatic liver cancer. Of patients with negative preoperative imaging and intraoperative assessment, none had involved perihepatic nodes. This conclusion is consistent with another report of a low incidence of missed diagnosis of LN metastases[45]. In addition to the increased operative time associated with lymphadenectomy, surgeons should factor potential complications into decisions about performing this procedure in these patients without LN involvement.

In addition, hepatectomy with LND might not contribute to long-term survival in patients with multiple tumors and LN metastases. These patients had similar survival to patients who underwent palliative resection (P = 0.744), possibly because both LN involvement and multiple tumors are poor prognostic factors[8]. However, patients with a solitary tumor and LN involvement might benefit from LND. Suzuki et al[21] reported that hepatic resection with LND may be curative for patients with a solitary tumor and a single LN metastasis. Nakagawa et al[24] also reported that curative resection with LND could improve the prognosis of patients with a solitary tumor and no more than two LN metastases. In our series of patients with ICC, those with a solitary tumor and LN involvement had better survival than did palliative resection patients. The median survival time was 12 mo vs 6.0 mo (P = 0.013). Although LN metastasis is an independent prognostic factor, it seems that LND can prolong the survival time of patients with a solitary tumor and LN metastases. However, more studies are needed.

Because our study was based on retrospectively available medical records, and more than five surgeons were involved in treating the study patients, it is difficult to draw definite conclusions about the indications for LND.

In conclusion, ICC patients without LN involvement and patients with multiple tumors and LD metastases may not benefit from aggressive lymphadenectomy. Without sufficient evidence, routine LND for all the ICC patients would be dogmatic. Routine LND should be considered with discretion.

COMMENTS

Background

Surgical resection is considered to improve the survival of patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). Lymph node (LN) involvement significantly affects survival adversely. However, the benefit of lymph node dissection (LND) is still controversial.

Research frontiers

Although LN metastasis was considered one of the most significant prognostic factors for patients with ICC, whether routine LND should be adopted is still controversial. Some consider that LN metastasis should not be considered a selection criterion that prevents patients from undergoing a potentially curative resection. Lymphadenectomy should be considered for all patients. On the other hand, some consider that routine use of LND in patients with ICC is not recommended, because no difference in survival was observed in patients with negative LN metastases, irrespective of the use of LND.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The indications for, and roles of, LND in patients with ICC are still subject to discussion. It is important to define the role of LND because it is a modifiable factor by a surgeon during hepatic resection, but no clear guidelines yet exist. In this study, they found that ICC patients without LN involvement and patients with multiple tumors and LN metastases may not benefit from aggressive lymphadenectomy.

Applications

It is unclear whether prophylactic clearance of the route of LN metastasis improves survival. Thire findings may provide a reference to the criterion for LND in ICC patients. Routine LND should be considered with discretion for ICC patients without LN involvement and patients with multiple tumors and LN metastases. Routine LND can be performed for the patients with a solitary tumor and LN metastases for a better survival.

Peer review

The authors investigated the benefit of LND in the patients with ICC. They concluded that ICC patients without LN involvement and patients with multiple tumors and LN metastases may not benefit from aggressive lymphadenectomy, so routine LND should be considered with discretion. It is a well written manuscript that addresses an interesting topic. It also provides useful data on recurrences. The design is appropriate and the conclusion is reasonable.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Assadi M, Cidon EU, Hu HP, Vinh-Hung V S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Casavilla FA, Marsh JW, Iwatsuki S, Todo S, Lee RG, Madariaga JR, Pinna A, Dvorchik I, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Hepatic resection and transplantation for peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:429–436. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikai I, Arii S, Okazaki M, Okita K, Omata M, Kojiro M, Takayasu K, Nakanuma Y, Makuuchi M, Matsuyama Y, et al. Report of the 17th Nationwide Follow-up Survey of Primary Liver Cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:676–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimada M, Yamashita Y, Aishima S, Shirabe K, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K. Value of lymph node dissection during resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1463–1466. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto M, Takasaki K, Yoshikawa T. Lymph node metastasis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29:147–150. doi: 10.1093/jjco/29.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobin LH, Wittekind C, editors . International Union Against Cancer (UICC): TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. 5th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimada H, Endo I, Togo S, Nakano A, Izumi T, Nakagawara G. The role of lymph node dissection in the treatment of gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:892–899. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970301)79:5<892::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitagawa Y, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Sano T, Yamamoto H, Hayakawa N, Nimura Y. Lymph node metastasis from hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 110 patients who underwent regional and paraaortic node dissection. Ann Surg. 2001;233:385–392. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribero D, Pinna AD, Guglielmi A, Ponti A, Nuzzo G, Giulini SM, Aldrighetti L, Calise F, Gerunda GE, Tomatis M, et al. Surgical Approach for Long-term Survival of Patients With Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Multi-institutional Analysis of 434 Patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:1107–1113. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong MC, Nathan H, Sotiropoulos GC, Paul A, Alexandrescu S, Marques H, Pulitano C, Barroso E, Clary BM, Aldrighetti L, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis of prognostic factors and lymph node assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3140–3145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353–1357. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber SM, Jarnagin WR, Klimstra D, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: resectability, recurrence pattern, and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:384–391. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Rassi ZE, Partensky C, Scoazec JY, Henry L, Lombard-Bohas C, Maddern G. Peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: presentation, diagnosis, pathology and management. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25:375–380. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang T, Zhang J, Lu JH, Yang LQ, Yang GS, Wu MC, Yu WF. A new staging system for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with six existing staging systems in a large Chinese cohort. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:739–750. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathan H, Pawlik TM. Staging of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:269–273. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328337c899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uenishi T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Yamamoto T, Yamazaki O, Kinoshita H. Clinicopathological factors predicting outcome after resection of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:969–974. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okabayashi T, Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Takayama T, Makuuchi M. A new staging system for mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of preoperative and postoperative variables. Cancer. 2001;92:2374–2383. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2374::aid-cncr1585>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue K, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Torzilli G, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, Kosuge T, Yamasaki S, Konishi M, Kinoshita T, et al. Long-term survival and prognostic factors in the surgical treatment of mass-forming type cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 2000;127:498–505. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.104673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawarada Y, Yamagiwa K, Das BC. Analysis of the relationships between clinicopathologic factors and survival time in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2002;183:679–685. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isa T, Kusano T, Shimoji H, Takeshima Y, Muto Y, Furukawa M. Predictive factors for long-term survival in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001;181:507–511. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirabe K, Shimada M, Harimoto N, Sugimachi K, Yamashita Y, Tsujita E, Aishima S. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: its mode of spreading and therapeutic modalities. Surgery. 2002;131:S159–S164. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.119498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki S, Sakaguchi T, Yokoi Y, Okamoto K, Kurachi K, Tsuchiya Y, Okumura T, Konno H, Baba S, Nakamura S. Clinicopathological prognostic factors and impact of surgical treatment of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2002;26:687–693. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uenishi T, Yamazaki O, Yamamoto T, Hirohashi K, Tanaka H, Tanaka S, Hai S, Kubo S. Serosal invasion in TNM staging of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:479–483. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morimoto Y, Tanaka Y, Ito T, Nakahara M, Nakaba H, Nishida T, Fujikawa M, Ito T, Yamamoto S, Kitagawa T. Long-term survival and prognostic factors in the surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:432–440. doi: 10.1007/s00534-002-0842-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagawa T, Kamiyama T, Kurauchi N, Matsushita M, Nakanishi K, Kamachi H, Kudo T, Todo S. Number of lymph node metastases is a significant prognostic factor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:728–733. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7761-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohtsuka M, Ito H, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Togawa A, Yoshidome H, Miyazaki M. Results of surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and clinicopathological factors influencing survival. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1525–1531. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxena A, Chua TC, Sarkar A, Chu F, Morris DL. Clinicopathologic and treatment-related factors influencing recurrence and survival after hepatic resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a 19-year experience from an established Australian hepatobiliary unit. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1128–1138. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ercolani G, Vetrone G, Grazi GL, Aramaki O, Cescon M, Ravaioli M, Serra C, Brandi G, Pinna AD. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: primary liver resection and aggressive multimodal treatment of recurrence significantly prolong survival. Ann Surg. 2010;252:107–114. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e462e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho SY, Park SJ, Kim SH, Han SS, Kim YK, Lee KW, Lee SA, Hong EK, Lee WJ, Woo SM. Survival analysis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1823–1830. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirabe K, Mano Y, Taketomi A, Soejima Y, Uchiyama H, Aishima S, Kayashima H, Ninomiya M, Maehara Y. Clinicopathological prognostic factors after hepatectomy for patients with mass-forming type intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: relevance of the lymphatic invasion index. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1816–1822. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0929-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Campagnaro T, Pachera S, Valdegamberi A, Nicoli P, Cappellani A, Malfermoni G, Iacono C. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic factors after surgical resection. World J Surg. 2009;33:1247–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamandl D, Kaczirek K, Gruenberger B, Koelblinger C, Maresch J, Jakesz R, Gruenberger T. Lymph node ratio after curative surgery for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2009;96:919–925. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimada K, Sano T, Nara S, Esaki M, Sakamoto Y, Kosuge T, Ojima H. Therapeutic value of lymph node dissection during hepatectomy in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma with negative lymph node involvement. Surgery. 2009;145:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yedibela S, Demir R, Zhang W, Meyer T, Hohenberger W, Schönleben F. Surgical treatment of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an 11-year Western single-center experience in 107 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:404–412. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagohri T, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Takahashi S, Gotohda N. Surgical outcome and prognostic factors in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2008;32:2675–2680. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uenishi T, Kubo S, Yamazaki O, Yamada T, Sasaki Y, Nagano H, Monden M. Indications for surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with lymph node metastases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimada K, Sano T, Sakamoto Y, Esaki M, Kosuge T, Ojima H. Clinical impact of the surgical margin status in hepatectomy for solitary mass-forming type intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma without lymph node metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:160–165. doi: 10.1002/jso.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi SB, Kim KS, Choi JY, Park SW, Choi JS, Lee WJ, Chung JB. The prognosis and survival outcome of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma following surgical resection: association of lymph node metastasis and lymph node dissection with survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3048–3056. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asakura H, Ohtsuka M, Ito H, Kimura F, Ambiru S, Shimizu H, Togawa A, Yoshidome H, Kato A, Miyazaki M. Long-term survival after extended surgical resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with extensive lymph node metastasis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:722–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uenishi T, Yamazaki O, Horii K, Yamamoto T, Kubo S. A long-term survivor of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with paraaortic lymph node metastasis. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:391–392. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, Grigioni WF, Cescon M, Gardini A, Del Gaudio M, Cavallari A. The role of lymphadenectomy for liver tumors: further considerations on the appropriateness of treatment strategy. Ann Surg. 2004;239:202–209. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109154.00020.e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miwa S, Miyagawa S, Kobayashi A, Akahane Y, Nakata T, Mihara M, Kusama K, Soeda J, Ogawa S. Predictive factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma recurrence in the liver following surgery. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:893–900. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1877-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakagohri T, Asano T, Kinoshita H, Kenmochi T, Urashima T, Miura F, Ochiai T. Aggressive surgical resection for hilar-invasive and peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2003;27:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibbs JF, Weber TK, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Driscoll DL, Petrelli NJ. Intraoperative determinants of unresectability for patients with colorectal hepatic metastases. Cancer. 1998;82:1244–1249. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980401)82:7<1244::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grobmyer SR, Wang L, Gonen M, Fong Y, Klimstra D, D’Angelica M, DeMatteo RP, Schwartz L, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Perihepatic lymph node assessment in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy for malignancy. Ann Surg. 2006;244:260–264. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217606.59625.9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun HC, Zhuang PY, Qin LX, Ye QH, Wang L, Ren N, Zhang JB, Qian YB, Lu L, Fan J, et al. Incidence and prognostic values of lymph node metastasis in operable hepatocellular carcinoma and evaluation of routine complete lymphadenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:37–45. doi: 10.1002/jso.20772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]