Significance

For an understanding of the molecular mechanism of actin-based motility, knowledge of the underlying molecular architectures is indispensable. We have used cryo-electron tomography to study the supramolecular arrangements of actin filaments in unperturbed cellular environments. An in-depth quantitative analysis of comet tails, stress fibers, and filopodia has revealed the existence of bundles of nearly parallel actin filaments, some of them hexagonally packed and with strikingly similar spacings between the filaments. This common feature of actin filament architecture has important implications for the mechanical properties of actin supramolecular assemblies and for the mechanism of force generation.

Keywords: cellular actin structures, actin bundles, bundling proteins, force generation

Abstract

The intracellular bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes is capable of remodelling the actin cytoskeleton of its host cells such that “comet tails” are assembled powering its movement within cells and enabling cell-to-cell spread. We used cryo-electron tomography to visualize the 3D structure of the comet tails in situ at the level of individual filaments. We have performed a quantitative analysis of their supramolecular architecture revealing the existence of bundles of nearly parallel hexagonally packed filaments with spacings of 12–13 nm. Similar configurations were observed in stress fibers and filopodia, suggesting that nanoscopic bundles are a generic feature of actin filament assemblies involved in motility; presumably, they provide the necessary stiffness. We propose a mechanism for the initiation of comet tail assembly and two scenarios that occur either independently or in concert for the ensuing actin-based motility, both emphasizing the role of filament bundling.

Several pathogens, including Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri, and Rickettsiae, have developed means to hijack the actin cytoskeleton of their host cells to move inside the host’s cytosol and to spread from cell to cell (1, 2). The cytoplasmic comet tails assembled from actin and actin-interacting proteins propel the bacteria forward and form protrusions emanating from the cell surface, which then become engulfed by neighboring cells.

Several studies using light microscopy and EM have attempted to visualize the supramolecular organization of Listeria cytoplasmic comet tails and protrusions (1–8). Despite advances in superresolution fluorescence microscopy, this technique has not yet resolved individual actin filaments in crowded environments. Furthermore, conventional EM applied to detergent-extracted and dehydrated samples suffers from artifacts or a complete collapse of the delicate cytoskeletal networks. Cytoplasmic comet tails were reported to consist of multiple short actin filaments forming a cross-linked and branched network (1, 2) with some degree of alignment at their periphery (7). Branching occurs at the bacterial surface through the interaction of the bacterial surface protein ActA with the Arp2/3 complex (9, 10), which nucleates daughter filaments at an angle of 70° from preexisting filaments (10–12). Isolated Listeria protrusions were described as containing bundles of long, axial filaments, interspersed by short, randomly oriented filaments (3). To date, the detailed molecular architecture of these networks, which is key to understanding actin-based motility, has remained elusive.

We examined Listeria comet tails, stress fibers, and filopodia, in their native cellular environment using cryo-electron tomography (CET). CET combines the power of 3D imaging with a close-to-life preservation of cellular structures (13). We cultivated epithelial Potoroo kidney Ptk2 cells on EM grids and infected them with Listeria monocytogenes (SI Text). Uninfected, as well as infected, cells were subjected to plunge-freezing (13), and tomographic datasets of filopodia, stress fibers, and Listeria cytoplasmic comet tails near the periphery of cells or in protrusions were recorded (SI Text).

For the interpretation of the tomograms, we applied an automated segmentation algorithm developed specifically for tracking actin filaments (14). Unlike manual segmentation, automated segmentation is fast and unbiased. Due to the low signal-to-noise ratio of CET data, we applied the algorithm conservatively, which tends to underestimate the frequency of branching and the length of filaments. Furthermore, short filaments (<100 nm in comet tails and <70 nm in stress fibers and filopodia) were excluded from the analysis to avoid false-positive results. Tomograms of five Listeria cytoplasmic comet tails (Fig. 1A and Figs. S1A and S2A), nine Listeria protrusions (Fig. 2A and Figs. S3B and S4 A and D), eight stress fibers (Fig. 3C and Fig. S5 A and D), and four filopodia (Fig. 3A and Fig. S6 A and F) were subjected to segmentation. The localization of individual filaments and the analysis of their local neighborhood were used to describe quantitatively the architecture of the networks.

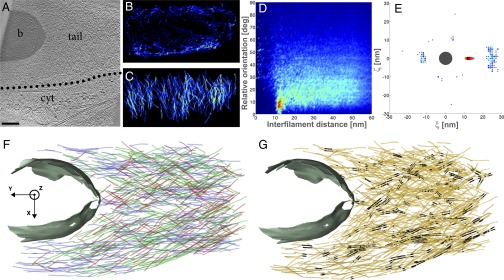

Fig. 1.

Hollow Listeria cytoplasmic comet tail contains closely packed parallel filaments. (A) Slice through the tomogram of a cytoplasmic comet tail (tail) in a PtK2 cell (cytoplasm is indicated by cyt) infected by Listeria (b). (Scale bar: 200 nm.) Distribution of XY-filaments (B) and Z-filaments (C) in the XZ plane, projected over the Y axis. The color scale ranges from high occurrence (red) to low occurrence (blue) (same color code in all relevant panels). (D) Two-dimensional histogram of interfilament distances, weighted by the distance, and relative orientations between the filaments. deg, degrees. (E) Two-dimensional histogram of the (ξ, ζ) coordinates of the neighboring filaments in an XY-bundle in the local plane perpendicular to the central filament (dark gray, drawn to scale). (F) XY-filaments projected into the XY plane. The color of the filaments corresponds to their angle with respect to the Y axis: 0–15° (blue), 15–30° (green), 30–45° (red). The cell wall of the bacterium is shown in gray. (G) XY-pairs of parallel filaments (black) among XY-filaments (orange).

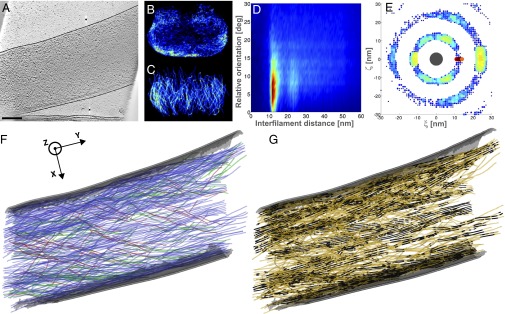

Fig. 2.

Listeria protrusion shows hexagonal bundles in the vicinity of the plasma membrane. (A) Slice through the tomogram of a protrusion formed by Listeria at the surface of a PtK2 cell. The electron micrograph is shown in Fig. S3A. (Scale bar: 200 nm.) Distribution of XY-filaments (B) and Z-filaments (C) in the XZ plane, projected over the Y axis. (D) Two-dimensional histogram of interfilament distances, weighted by the distance, and relative orientations between the filaments. (E) Two-dimensional histogram of the (ξ, ζ) coordinates of the neighboring filaments in an XY-bundle in the local plane perpendicular to the central filament (dark gray, drawn to scale). (F) XY-filaments projected into the XY plane (same color code as in Fig. 1F). The plasma membrane of the protrusion is shown in gray. (G) XY-pairs of parallel filaments (black) among XY-filaments (orange).

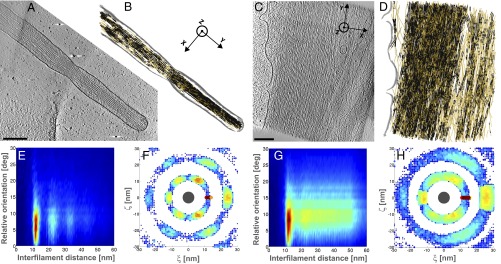

Fig. 3.

Filopodia and stress fibers contain hexagonal bundles. Slices through the tomograms of a filopodium (A) and a stress fiber (C) of a PtK2 cell. (Scale bar: 200 nm.) (B and D) XY-pairs of parallel filaments (black) among XY-filaments (orange). The plasma membrane is shown in gray. (E and G) Two-dimensional histogram of interfilament distances, weighted by the distance, and relative orientations between the filaments. (F and H) Two-dimensional histogram of the (ξ, ζ) coordinates of the neighboring filaments in an XY-bundle in the local plane perpendicular to the central filament (dark gray, drawn to scale).

We found that many filaments in the comet tails, stress fibers, and filopodia are organized into bundles with spacings between 12 and 13 nm. Moreover, we discovered an arrangement in which filaments are assembled into hexagonal close-packed arrays. Based on our results, we propose a mechanism for the initiation of comet tail assembly and two scenarios enabling Listeria motility, both illuminating the role of filament bundling.

Results

Comet Tails at the Cell Periphery Are Not Rotationally Symmetrical.

Actin polymerization occurs at nucleation sites on the bacterial surface, propelling Listeria cells forward, whereas the comet tails remain stationary (15–17). The orientation of the filaments in the comet tails in the vicinity of the bacterium is therefore assumed to reflect the orientation near their origin. CET experiments were performed on thin areas of the cell. In the data presented, the bacterium moves within the confines of the thin cytoplasm in the plane of the substrate; therefore, the comet tails described are not rotationally symmetrical about the long axis of the network (Fig. S7). Instead of using the long axis of the comet tail as the frame of reference, we used the substrate plane. This also permits the analysis of the other cellular networks explored here.

The XY plane of the substrate was defined using principal component analysis of the coordinates of the filaments (SI Text). In our Cartesian coordinate system, the Y axis is defined along the long axis of the network, which usually coincides with the long axis of the bacterium in the case of comet tails. The X axis is associated with the width of the network on the plane of the substrate. The Z axis is perpendicular to the XY plane and corresponds to the thickness of the network. We distinguish between filaments with a deviation out of the XY plane toward Z smaller than 30° (“XY-filaments”) and filaments with a deviation larger than 30° (“Z-filaments”). We defined 30° as the inclination limit, above which filaments do not belong to the XY plane.

Filaments Tangential to the Bacterial Surface Contribute to the Comet Tail Architecture During Intracellular Movement and Cell-to-Cell Spread.

The majority of the filaments are XY-filaments both in cytoplasmic comet tails (73%) and in protrusions (89%), and they are typically 200–300 nm in length (Table S1). In cytoplasmic comet tails, XY-filaments exist in high density (Figs. S1B and S2B), enveloping the pole of the bacteria tangentially (Fig. 1F and Figs. S1E and S2F). One of five cytoplasmic comet tails was found to be almost depleted of internal XY-filaments (Fig. 1B). A similar, nearly hollow shell structure of XY-filaments is observed in protrusions, where they are mainly found in the vicinity of the membrane (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4B; five of nine tomograms). In cytoplasmic comet tails and in protrusions, Z-filaments are typically 150 nm long; they appear throughout the entire tail, coating the bacterial pole tangentially (Figs. 1C and 2C and Figs. S1C, S2C, and S4 C and F). Interestingly, XY- and Z-filaments are tangential to the bacterial surface.

Cytoplasmic Comet Tails and Protrusions Contain Closely Packed Parallel Filaments.

To analyze quantitatively comet tail architecture, we determined distances and relative orientations (angles) between filaments (SI Text and Figs. S8 and S9). For interfilament angles between 0° and 15° (i.e., a nearly parallel orientation), we found spacings of 12.8 ± 1.1 nm in cytoplasmic comet tails (Fig. 1D and Figs. S1D and S2D) and spacings of 12.3 ± 0.8 nm in protrusions (Fig. 2D and Fig. S4 K and M). Several bundling/cross-linking proteins have been localized in Listeria comet tails, including fascin, fimbrin, alpha-actinin, and filamin (8, 15, 18–20). Our data provide unique insight at the molecular level into the local environment of actin networks where these proteins are known to act. The interfilament angular range we found is in good agreement with the geometries induced in actin filaments by these proteins, which are known to vary in cross-bridge conformations, angles, stoichiometry, and lengths, as well as in the relative rotation and axial offset between neighboring filaments (21–23). Moreover, the spacings between the filaments are consistent with fimbrin cross-linking spacings of 11.5–12 nm (23) but far from spacings reported for fascin (8–9 nm) (24) or alpha-actinin (39 nm) (25).

In addition, our analysis unveiled long-range order in the structures. In our actin-tail data, two of the protrusions exhibited a second-order peak (i.e., reflecting distances at a position corresponding to twice the main interfilament spacing) (Fig. 2D). We did not detect significant contributions of filaments with an angular orientation of 70° in cytoplasmic comet tails (Fig. 1D and Figs. S1D and S2D) or in protrusions (Fig. S4 K and M). This suggests that branches within the actin comet tails either escape detection or are rather short, and therefore likely to be excluded during the elimination of small filaments.

Filopodia and Stress Fibers Show Similar Interfilament Spacings as Found in Comet Tails.

Filopodia are thin plasma membrane protrusions, in which actin is mainly bundled by fascin (26) (Fig. 3A and Fig. S6 A and F). Stress fibers are contractile actomyosin bundles mainly cross-linked by periodically arranged alpha-actinin (27) and possibly by other bundling proteins (Fig. 3C and Fig. S5 A and D). The actin filaments in the tomograms of stress fibers and filopodia were subjected to the same segmentation procedure and analysis. For interfilament angles between 0° and 15°, we found interfilament spacings of 12.2 ± 0.9 nm in filopodia (Fig. 3E and Fig. S6 D and I; four tomograms) and 13.3 ± 1.3 nm in stress fibers (Fig. 3G and Fig. S5 G and I; eight tomograms). Strikingly, Listeria cytoplasmic comet tails and protrusions, as well as filopodia and stress fibers, all contain tightly packed parallel filaments of similar spacings. These spacings are in disagreement with those reported for fascin (24) or alpha-actinin (25) in vitro.

In one filopodium network, second- and third-order peaks were detected (Fig. 3E), reflecting long-range order. In stress fibers, a second-order peak was detectable among contributions of spacings over the full distance range (Fig. 3G and Fig. S5 G and I). This indicates that although longer range order exists, parallel filaments are less ordered in stress fibers than in filopodia.

Actin Packing in Comet Tails, Filopodia, and Stress Fibers.

We investigated the proportion of parallel filaments for each type of actin network (SI Text and Table S1). We define pairs as being composed of two parallel filament segments, bundles as being built of at least three parallel filament segments, and sheets as planar bundles (i.e., made of three parallel filament segments in the same plane). Parallel filaments were absent from Z-filaments. The percentage of pairs among XY-filaments (“XY-pairs”) is up to 21% in cytoplasmic tails (Fig. 1G, Figs. S1F and S2G, and Table S1), 35% in protrusions (Fig. 2G and Figs. S3E and S4 I and J), 63% in stress fibers (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5 C and F), and 72% in filopodia (Fig. 3B and Fig. S6 C and H). Sheets found among XY-filaments (“XY-sheets”) were almost absent from cytoplasmic comet tails (<2%), rare in protrusions (1–7%) and in stress fibers (6–16%), but more abundant in filopodia (12–25%). We explored further the order of packing of parallel XY-filaments. We looked for filament packing in a hexagonal lattice (“XY-hexagonal bundle”) (SI Text). Less than 1% fell into that category in cytoplasmic comet tails, up to 6% in protrusions, between 3 and 14% in stress fibers, and between 9 and 30% in filopodia. Filopodia appear to have the highest long-range order in the spatial arrangement of the filaments.

Filopodia Form Hexagonal Bundles, Whereas Stress Fibers Organize in Sheets.

To distinguish between sheets and hexagonal packing, we examined the spatial distribution of XY-filaments belonging to a bundle (“XY-bundle”) (SI Text and Fig. S8G).

Filopodia were typically between 100 and 150 nm in diameter (Fig. 3A and Fig. S6 A and F). Two filopodia networks contain hexagonal close-packed XY-bundles made of two to three layers, with up to 36 rotationally arranged neighboring filaments and a mean spacing of 12.2 nm (Fig. 3F, Fig. S6E, and Table S1). The other two filopodia are less tightly packed but also contain hexagonal bundles (Fig. S6J). Our data imply that filopodia are made of large bundles comprising six to eight layers, hexagonally packed locally but with some imperfections in the overall packing.

Stress fibers comprise stacked XY-sheets containing laterally up to five filaments with a mean spacing of 13.3 nm (Fig. 3H and Fig. S5 H and J). The full range of interfilament spacings found in stress fibers (Fig. 3G and Fig. S5 G and I) indicates that on a larger length scale, they form less regular and densely packed XY-sheets. This looser overall packing would allow for the stress fibers to fulfill their contractile role, providing flexibility to the network. This is also consistent with the alternation of filament polarity reported in Ptk2 cells at a typical periodicity of 0.6 μm along the filament length (28), which may induce irregularities in the filament distribution through the network.

Protrusions Are Built of Hexagonal Bundles Adjacent to the Plasma Membrane.

Most of the protrusions (Fig. S4 L and N; seven of nine tomograms) and all cytoplasmic comet tails (Fig. 1E and Fig. S2E; five tomograms) contain XY-pairs or XY-sheets of up to four filaments. In some protrusions, stacked XY-sheets were also visible (Fig. S4L). Protrusions tend to have higher local order than cytoplasmic comet tails. In two of them, we observed hexagonal close-packed XY-bundles (made of two layers) (Fig. 2E and Fig. S3D) in the vicinity of the plasma membrane (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, reconstituted lipid bilayers are known to be capable of inducing filopodium-like protrusions from branched actin networks without the help of bundling or tip-complex proteins (29). Our data indicate that, in situ, in protrusions assembled by Listeria, bundle formation is favored in the vicinity of the plasma membrane. This is likely due to interactions between actin and the plasma membrane, which have been ascribed to ezrin, a protein that accumulates at the plasma membrane of the protrusions (3) and contributes to their formation (30).

Discussion

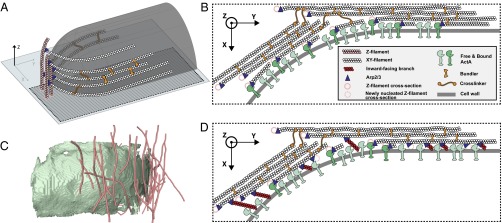

Actin Clouds Are Made of Z-Filaments, Which Serve to Nucleate XY-Filaments.

The tangential orientation of both Z- and XY-filaments with respect to the bacterial cell wall is likely to arise from a favored nucleation pattern. It has been shown that nucleation geometry can be the principal determinant of actin-network architecture (31). The bacterial surface protein ActA serves to nucleate actin assembly, together with the Arp2/3 complex (9, 10). Arp2/3 nucleates daughter filaments, creating branches from preexisting filaments (10–12). Filaments parallel to a surface have been proposed to favor branching along it (32). Our data on actin clouds at the earliest stage in the comet tail assembly show that clouds are mostly made of short Z-filaments (Fig. 4C and Fig. S10), indicating that Z-filaments are nucleated first, and thus are likely to serve as preexisting filaments for new branches along the bacterial surface. The orientation of XY-filaments with respect to Z-filaments is compatible with a branch junction (Fig. 4A). ActA, together with Arp2/3, could therefore generate branches from Z-filaments, resulting in the nucleation of XY-filaments. Furthermore, the hexagonally packed XY-filaments detected in our data explain the maximum packing density of 0.3 ActA molecules per 100 nm2 measured at the Listeria surface and found to be compatible with a hexagonal lattice constant of 11.4 nm (33).

Fig. 4.

Mechanism for the initiation of comet tail assembly and scenarios for Listeria actin-based propulsion. (A) Z-filaments (pink) are first nucleated tangentially to the bacterial cell wall (transparent gray). XY-filaments (white) originate as branches from Z-filaments, which act as “primers” (32) for XY-filament growth tangential to the cell wall in the XY plane. (B) Model of squeezing bundles. The de novo nucleation of XY-filaments along the bacterial surface, constrained to grow between the surface and the stiff scaffold of cross-linked XY-bundles, creates a squeezing stress, which pushes the bacterium forward. (C) Side view of Z-filaments (pink) extracted from the tomogram of an actin cloud (Fig. S10). The cell wall of the bacterium is shown in green. (D) Model of pushing bundles. The tangential orientation of the XY-bundles along the bacterial surface could favor Arp2/3-dependent explosive growth of branches at the surface, as proposed by Achard et al. (32). Tangential branches from XY-filaments could give rise to newly nucleated Z-filaments (dashed pink circles). Inward- and outward-facing branches are not displayed here. The simultaneous polymerization of these multiple branches, constrained to grow between the surface and the stiff scaffold of cross-linked XY-bundles, could generate a compressive stress, which pushes the bacterium forward.

Similar Interfilament Spacings Are Observed with a Variety of Bundlers.

Filopodia have a mean interfilament spacing of 12.2 nm (Table S1) and exhibit hexagonal packing, suggesting that fascin, the dominant bundling protein in filopodia (26), enables this geometry. Protrusions are mainly bundled by fascin and fimbrin (8, 18, 20), resulting in a mean interfilament spacing of 12.3 nm. This value is in agreement with in vitro work on 2D actin arrays cross-linked by fimbrin (23) and with our filopodia data. Alpha-actinin, which is absent from protrusions (3), is one of the main cross-linkers in cytoplasmic comet tails (15) and in stress fibers (27). Our data suggest further that alpha-actinin, mostly known as a cross-linker, can contribute to bundling and give rise to a mean interfilament spacing between 12.8 and 13.3 nm (Table S1); alpha-actinin appears to favor an arrangement in sheets. Different bundling proteins, despite differences in cross-bridge conformation, angles, and length, apparently satisfy a narrow range of interfilament spacings. Moreover, most of the network architectures we observed, and thus most or all of the bundling proteins involved, allow for hexagonal packing.

Actin Comet Tails in Situ Contain Stiff, Cross-Linked Bundles.

The established presence of alpha-actinin or filamin in the comet-tail networks (15, 19) implies that the XY-bundles are cross-linked to some extent. Listeria comet tails would therefore consist of interconnected bundles that cover the rear end of the bacteria. An actin bundle was found to be two orders of magnitude stiffer than a group of non–cross-linked actin filaments of similar radius (34). Furthermore, compact bundles embedded into cross-linked orthogonal networks form significantly stiffer structures than structures containing only bundles or only orthogonally cross-linked individual filaments (35). Based on our observation of actin bundling in comet tails, we predict that Listeria assembles stiffer structures than previously suggested (1, 2).

Cross-Linked Actin Bundles Can Provide the Stiffness Necessary for Intracellular Movement and Cell-to-Cell Spread.

The mechanism of force generation in Listeria motility is still under debate. It has been analyzed extensively using experimental biomimetic systems (36), combined with theoretical models on both molecular and mesoscopic scales (37). In vitro assays rely on functionalized latex beads or lipid vesicles, as well as reconstituted motility medium (38) or cell extracts. A branched (so-called “dendritic”) organization has been observed in comet tails at the surface of latex beads in cell extracts (39). Based on this observation and aiming toward the reconstitution of actin-based motility directly from essential proteins, in vitro studies have not taken into account the role of filament bundling in the force generation mechanism. Here, we show that the 3D architecture of Listeria comet tails differs from a dendritic organization. Moreover, bundling proteins, which are not included in the minimal set of proteins reported to generate actin-based motility (38), are nevertheless likely to play an important role in Listeria motility. It is probable that Listeria movement in the crowded cellular environment requires a higher force to push the bacteria forward than in biomimetic motility systems. The combination of local bundling of the actin filaments and overall cross-linking of the actin bundles could provide the necessary stiffness. In protrusions, the higher order of packing at the membrane could increase the efficiency of force transmission along a particular direction and appears to be a general mechanism of cellular protrusions.

Initiation of Comet Tail Assembly.

We propose the following mechanism for the initiation of Listeria comet tail assembly, based on our experimental data and recent in vitro work on branch formation initiated by tangential filaments (“primers”) to a surface (32). Z-filaments are nucleated first at the bacterial surface. They could possibly be nucleated through ActA and Arp2/3 as branches from surrounding cytoskeletal filaments in the vicinity of the Listeria cell wall. XY-filaments originate as branches from Z-filaments, which act as primers (32) for the growth of XY-filaments (Fig. 4A). XY-filaments are densely nucleated due to the close packing of ActA at the bacterial surface, possibly already in an arrangement compatible with hexagonal packing. The various bundling proteins in comet tails promote hexagonal packing. The XY-bundles could be cross-linked over the entire comet tail, and in the case of protrusions, they are supported by and anchored to the plasma membrane, probably by the membrane linker ezrin. The comet tail therefore consists of a stiff scaffold of interconnected bundles at the rear end of the bacteria.

Scenarios for Intracellular Movement and Cell-to-Cell Spread: Squeezing Bundles vs. Pushing Bundles.

Once the comet tail is longer than the bacteria, Listeria can move while the comet tail remains stationary (36). This takes place due to the viscous force that opposes the motion of an object in the cytoplasm and increases as a function of the object size. The two following scenarios can occur either independently or in concert, enabling Listeria motility. In a first scenario, the de novo nucleation of XY-filaments along the bacterial surface, constrained to grow between the surface and the stiff scaffold of cross-linked XY-bundles, creates a squeezing stress that pushes the bacterium forward (Fig. 4B). This nanoscopic model of “squeezing bundles” supports the mesoscopic “elastic propulsion” model, where the comet tail is seen as an elastic gel that generates squeezing forces (36, 40, 41). In a second scenario (“pushing bundles”) (Fig. 4D), the tangential orientation of the de novo XY-filaments along the bacterial surface, part of XY-bundles, can favor an Arp2/3-dependent explosive growth of branches at the surface, as proposed by Achard et al. (32). These small branches, which may have been removed from the analysis, can grow toward (“inward-facing branches”), tangentially to (“tangential branches”), or away from (“outward-facing branches”) the surface. Tangential branches from XY-filaments can give rise to newly nucleated Z-filaments. Inward-facing branches have been proposed to be stalled by the surface until they escape and grow tangentially as well, whereas outward-facing branches were found to be capped rapidly (32). Here, we propose that the simultaneous polymerization of multiple tangential, inward- and outward-facing branches constrained to grow between the surface and the stiff scaffold of XY-bundles can generate a compressive stress, which results in the bacterial motion. This process gives rise to new Z-filaments, which, in turn, allow for de novo polymerization of XY-filaments.

Materials and Methods

Detailed experimental procedures and references are given in SI Text. Briefly, cells were grown on EM grids and used for the infection assays, followed by cryofixation. CET was performed using a Tecnai G2 Polara transmission electron microscope (FEI). Tilt series were recorded with SerialEM, and tomograms were calculated using IMOD. Tomograms were then subjected to template matching using the filament segmentation package in Amira (FEI). Data analysis was performed in MATLAB (MathWorks) using as input the coordinates of the automatically detected filaments. The analysis is described in detail in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Günther and A. Rigort for help with the Amira software; A. Martinez-Sanchez for help with the membrane segmentation of the Listeria cell wall; S. Mostowy, A. H. Crevenna, L. F. Kourkoutis, and M. Schüler for fruitful discussions; and G. Gerisch for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization Long-Term Fellowship and a Marie Curie Action Intra-European Fellowship (to M.J.), the European Research Council (Grant 233348, to P.C.), European Union Seventh Framework Program Proteomics Specification in Space and Time Grant HEALTH-F4-2008-201648 (to W.B.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Excellence Cluster Center for Integrated Protein Science Munich Grant GRK 1721 (to E.V.), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and an interinstitutional research initiative of the Max Planck Society.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1320155110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(4 Pt 1):1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gouin E, et al. A comparative study of the actin-based motilities of the pathogenic bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri and Rickettsia conorii. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 11):1697–1708. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.11.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sechi AS, Wehland J, Small JV. The isolated comet tail pseudopodium of Listeria monocytogenes: A tail of two actin filament populations, long and axial and short and random. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(1):155–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tilney LG, Connelly PS, Portnoy DA. Actin filament nucleation by the bacterial pathogen, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1990;111(6 Pt 2):2979–2988. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilney LG, DeRosier DJ, Tilney MS. How Listeria exploits host cell actin to form its own cytoskeleton. I. Formation of a tail and how that tail might be involved in movement. J Cell Biol. 1992;118(1):71–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilney LG, DeRosier DJ, Weber A, Tilney MS. How Listeria exploits host cell actin to form its own cytoskeleton. II. Nucleation, actin filament polarity, filament assembly, and evidence for a pointed end capper. J Cell Biol. 1992;118(1):83–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhukarev V, Ashton F, Sanger JM, Sanger JW, Shuman H. Organization and structure of actin filament bundles in Listeria-infected cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1995;30(3):229–246. doi: 10.1002/cm.970300307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brieher WM, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ. Fascin-mediated propulsion of Listeria monocytogenes independent of frequent nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(2):233–242. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch MD, Iwamatsu A, Mitchison TJ. Actin polymerization is induced by Arp2/3 protein complex at the surface of Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1997;385(6613):265–269. doi: 10.1038/385265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welch MD, Rosenblatt J, Skoble J, Portnoy DA, Mitchison TJ. Interaction of human Arp2/3 complex and the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein in actin filament nucleation. Science. 1998;281(5373):105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amann KJ, Pollard TD. Direct real-time observation of actin filament branching mediated by Arp2/3 complex using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(26):15009–15013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211556398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullins RD, Heuser JA, Pollard TD. The interaction of Arp2/3 complex with actin: Nucleation, high affinity pointed end capping, and formation of branching networks of filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(11):6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucić V, Förster F, Baumeister W. Structural studies by electron tomography: From cells to molecules. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:833–865. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigort A, et al. Automated segmentation of electron tomograms for a quantitative description of actin filament networks. J Struct Biol. 2012;177(1):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dabiri GA, Sanger JM, Portnoy DA, Southwick FS. Listeria monocytogenes moves rapidly through the host-cell cytoplasm by inducing directional actin assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(16):6068–6072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theriot JA, Mitchison TJ, Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature. 1992;357(6375):257–260. doi: 10.1038/357257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanger JM, Sanger JW, Southwick FS. Host cell actin assembly is necessary and likely to provide the propulsive force for intracellular movement of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1992;60(9):3609–3619. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3609-3619.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kocks C, Cossart P. Directional actin assembly by Listeria monocytogenes at the site of polar surface expression of the actA gene product involving the actin-bundling protein plastin (fimbrin) Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2(4):207–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Kirk LS, Hayes SF, Heinzen RA. Ultrastructure of Rickettsia rickettsii actin tails and localization of cytoskeletal proteins. Infect Immun. 2000;68(8):4706–4713. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4706-4713.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Troys M, et al. The actin propulsive machinery: The proteome of Listeria monocytogenes tails. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375(2):194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hampton CM, Taylor DW, Taylor KA. Novel structures for alpha-actinin:F-actin interactions and their implications for actin-membrane attachment and tension sensing in the cytoskeleton. J Mol Biol. 2007;368(1):92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanein D, et al. An atomic model of fimbrin binding to F-actin and its implications for filament crosslinking and regulation. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5(9):787–792. doi: 10.1038/1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volkmann N, DeRosier D, Matsudaira P, Hanein D. An atomic model of actin filaments cross-linked by fimbrin and its implications for bundle assembly and function. J Cell Biol. 2001;153(5):947–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa R, Sakamoto T, Ando T, Higashi-Fujime S, Kohama K. Polarized actin bundles formed by human fascin-1: Their sliding and disassembly on myosin II and myosin V in vitro. J Neurochem. 2003;87(3):676–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor KA, Taylor DW, Schachat F. Isoforms of alpha-actinin from cardiac, smooth, and skeletal muscle form polar arrays of actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(3):635–646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeRosier DJ, Edds KT. Evidence for fascin cross-links between the actin filaments in coelomocyte filopodia. Exp Cell Res. 1980;126(2):490–494. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazarides E, Burridge K. Alpha-actinin: Immunofluorescent localization of a muscle structural protein in nonmuscle cells. Cell. 1975;6(3):289–298. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cramer LP, Siebert M, Mitchison TJ. Identification of novel graded polarity actin filament bundles in locomoting heart fibroblasts: Implications for the generation of motile force. J Cell Biol. 1997;136(6):1287–1305. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu AP, et al. Membrane-induced bundling of actin filaments. Nat Phys. 2008;4:789–793. doi: 10.1038/nphys1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pust S, Morrison H, Wehland J, Sechi AS, Herrlich P. Listeria monocytogenes exploits ERM protein functions to efficiently spread from cell to cell. EMBO J. 2005;24(6):1287–1300. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reymann AC, et al. Nucleation geometry governs ordered actin networks structures. Nat Mater. 2010;9(10):827–832. doi: 10.1038/nmat2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achard V, et al. A “primer”-based mechanism underlies branched actin filament network formation and motility. Curr Biol. 2010;20(5):423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Footer MJ, Lyo JK, Theriot JA. Close packing of Listeria monocytogenes ActA, a natively unfolded protein, enhances F-actin assembly without dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(35):23852–23862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803448200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin JH, Mahadevan L, So PT, Matsudaira P. Bending stiffness of a crystalline actin bundle. J Mol Biol. 2004;337(2):255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirtz D, Khatau SB. Protein filaments: Bundles from boundaries. Nat Mater. 2010;9(10):788–790. doi: 10.1038/nmat2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plastino J, Sykes C. The actin slingshot. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17(1):62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mogilner A. On the edge: Modeling protrusion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loisel TP, Boujemaa R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature. 1999;401(6753):613–616. doi: 10.1038/44183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cameron LA, Svitkina TM, Vignjevic D, Theriot JA, Borisy GG. Dendritic organization of actin comet tails. Curr Biol. 2001;11(2):130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerbal F, Chaikin P, Rabin Y, Prost J. An elastic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes propulsion. Biophys J. 2000;79(5):2259–2275. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76473-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernheim-Groswasser A, Prost J, Sykes C. Mechanism of actin-based motility: A dynamic state diagram. Biophys J. 2005;89(2):1411–1419. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.055822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.