Abstract

Ample evidence implicates neuroinflammatory processes in the etiology and progression of Alzheimer's disease (AD). To assess the specific role of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1) in AD we examined the effects of intra-hippocampal transplantation of neural precursor cells (NPCs) with transgenic over-expression of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1raTG) on memory functioning and neurogenesis in a murine model of AD (Tg2576 mice). WT NPCs- or sham-transplanted Tg2576 mice, as well as naive Tg2576 and WT mice served as controls. To assess the net effect of IL-1 blockade (not in the context of NPCs transplantation), we also examined the effects of chronic (4 weeks) intra-cerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of IL-1ra. We report that 12-month-old Tg2576 mice exhibited increased mRNA expression of hippocampal IL-1β, along with severe disturbances in hippocampal-dependent contextual and spatial memory as well as in neurogenesis. Transplantation of IL-1raTG NPCs 1 month before the neurobehavioral testing completely rescued these disturbances and significantly increased the number of endogenous hippocampal cells expressing the plasticity-related molecule BDNF. Similar, but less-robust effects were also produced by transplantation of WT NPCs and by i.c.v. IL-1ra administration. NPCs transplantation produced alterations in hippocampal plaque formation and microglial status, which were not clearly correlated with the cognitive effects of this procedure. The results indicate that elevated levels of hippocampal IL-1 are causally related to some AD-associated memory disturbances, and provide the first example for the potential use of genetically manipulated NPCs with anti-inflammatory properties in the treatment of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, neural precursor cells, interleukin-1, hippocampus, neurogenesis, microglia

INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades it became evident that inflammatory processes in the brain, including activation of microglia and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, have an important role in the etiology and progression of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Akiyama et al, 2000; Glass et al, 2010; Heneka et al, 2010b; McGeer and McGeer, 2003). Over-production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-1 has been particularly implicated in the pathophysiology of AD, because IL-1 is involved in acute neurodegeneration (Allan et al, 2005); post-mortem brain tissues from patients suffering from AD (as well as Down syndrome individuals, which usually develop AD in middle age) show increased production of IL-1, as well as the enzyme that is required for its processing (Griffin, 2011; Griffin et al, 1989); several IL-1 gene polymorphisms are associated with increased risk of developing AD (Rainero et al, 2004); IL-1 stimulates the expression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Goldgaber et al, 1989; Sheng et al, 1996) and promotes the hyperphosphorylation of tau (Ghosh et al, 2013; Li et al, 2003); reduced cholinergic function in AD is in part due to over-activity of acetylcholinesterase, whose levels can be elevated by IL-1 (Li et al, 2000); the drugs that are clinically used for treatment of AD (acetylcholiesterase inhibitors) attenuate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including peripheral and brain IL-1 (Pollak et al, 2005); the NLRP3 inflammasome and its associated enzyme caspase-1, which are responsible for IL-1 cleavage from its precursor protein, are over-expressed in the brains of AD patients; deficiency in the NLRP3/caspase-1 axis was found to completely rescue the memory impairments and other pathological symptoms in a mouse model of AD (Heneka et al, 2013), and finally, chronic peripheral administration of IL-1 receptor blocking antibody alleviated the neuroinflammation and neurobehavioral pathology in a transgenic model of AD (Kitazawa et al, 2011). While these phenomena suggest that elevated levels of IL-1 contribute to the pathophysiology of AD, recent studies surprisingly demonstrated that sustained transgenic IL-1 over-expression, as well as in vitro exposure to IL-1, lead to a reduction in amyloid pathology, mediated by enhancement of microglia-dependent plaque degradation (Ghosh et al, 2013; Shaftel et al, 2007; Tachida et al, 2008), with no evidence for IL-1-associated apoptosis of neurons or cholinergic axon degeneration (Matousek et al, 2012). Together, these findings suggest that IL-1 and neuroinflammation may produce both detrimental and beneficial effects on specific AD symptoms (Matousek et al, 2012; Shaftel et al, 2008).

In addition to its role in immunoregulation of inflammatory processes, IL-1 has a major role in neurobehavioral regulation (Goshen and Yirmiya, 2009b; McAfoose and Baune, 2009). In particular, at pathophysiological levels IL-1 can produce detrimental effects on hippocampal-dependent memory processes (Rachal Pugh et al, 2001; Yirmiya and Goshen, 2011), which may be related to its effects on several mechanisms of neural plasticity, including suppression of neurogenesis (Goshen et al, 2008; Koo and Duman, 2008; Wu et al, 2012) and the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Barrientos et al, 2003; Barrientos et al, 2004; Tong et al, 2008).

To integrate the neuroinflammatory, neuropathological and neurobehavioral effects of IL-1 in AD, we examined the specific role of hippocampal IL-1 signaling in the memory and neurogenesis disturbances exhibited by mice with AD-like pathology (Tg2576 mice) (Hsiao et al, 1996), by using intra-hippocampal transplantation of neural precursor cells (NPCs) with transgenic over-expression of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1raTG). This approach was chosen because in this genetic animal model of AD mice exhibit neuropathological changes along with memory disturbance despite lack of neurodegeneration (Irizarry et al, 1997), providing a unique opportunity to investigate AD-related changes in a brain environment that affects neurobehavioral functioning without tissue loss, as well as to devise therapeutic procedures for reversing AD-like symptoms by changing this environment. Furthermore, this approach allows to pinpoint the location of IL-1's involvement in AD-associated memory deficits, as we have previously shown that IL-1ra secretion by the transplanted NPCs is restricted to the hippocampus (ie, it does not diffuse to other brain or peripheral locations), and can counteract the IL-1-mediated detrimental effects of chronic stress on hippocampal-dependent memory and neurogenesis (Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2008). It should be noted that previous research has already demonstrated beneficial effects of WT NPCs transplantation on AD-associated memory disturbances (Blurton-Jones et al, 2009), and therefore we hypothesized that the effects of IL-1ra secretion will synergize with the effects of the NPCs transplantation to produce a very effective treatment for the AD-like symptoms. To assess the net effect of IL-1 blockade (not in the context of NPCs transplantation) we also examined the cognitive and neurogenic effects of chronic intra-cerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of IL-1ra.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were C3B6-Tg (APP695)3Dbo/J male mice, expressing the Mo/Hu APPSWE45 mutation (Tg2576 mice), and their littermate controls (originally obtained from Taconic Farms, USA, and bred in our laboratory). Mice were housed in an air-conditioned room (23±1 °C), with food and water ad libitum. The behavioral experiments were conducted during the first half of the dark phase of the 12-h light/dark cycle. Newborn IL-1raTG mice (with astrocyte-directed over-expression of the human IL-1ra gene under the control of the murine glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter (Lundkvist et al, 1999)) and their WT controls (C57BL/6XCBA strain, originally derived from the non-transgenic littermates of the transgenic offspring) were used as a source for NPCs. The experiments were approved by the Hebrew University Committee on Animal Care and Use.

RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis and Real-Time PCR

To examine the levels of hippocampal IL-1β in Tg2576 vs WT mice, total RNA was isolated by a commercial TriReagent (Sigma). The amount and quality of RNA was determined with the ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out with Super Script II RNase H-reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) using a random primer.

The mRNA expression of IL-1β was quantified in the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) by using Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix UDG with ROX (Invitrogen), following the instructions of the manufacturer. Quantitative calculations of IL-1β expression vs HPRT was performed using the ΔΔCT method.

Preparation of NPCs and Growth of Neurospheres

NPC spheres were prepared from newborn IL-1raTG or WT mice, as previously described (Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2008; Ben-Hur et al, 2003). Briefly, the hemispheres were dissected, followed by removal of the meninges. The tissue was minced, digested by trypsin for 20 min, and dissociated. Following suspension in N2 medium, 10 × 106 cells were plated in a T-75 uncoated flask and supplemented with 10 ng/ml FGF2 and 20 ng/ml EGF, added daily. After 5 days of growth, undifferentiated neurospheres were collected for transplantation.

Sphere Transplantation

Prior to transplantation, spheres were incubated with 25 μg/ml BrdU for 72 hr. Examination of the spheres in vitro (before transplantation) revealed that >95% of the cells incorporated BrdU, as we previously reported (Fainstein et al, 2013). The spheres (4000 spheres/4 μl N2 medium) were bilaterally transplanted into the hippocampus using a stereotaxic instrument. Coordinates of the injection site (in mm relative to Bregma) were as follows: AP −2.6, L ±1.4, DV −1.6. Injections were conducted using a 25-μl Hamilton syringe. After each injection, the needle was left in situ for 5 min before being retracted, to allow complete diffusion of the spheres. The spheres were transplanted into the hippocampus of 11-month-old mice and behavioral testing commenced 4 weeks later. Mice from the sham-operated group were similarly injected with 4 μl N2 medium only. At the end of the behavioral tests (ie, 5–6 weeks post transplantation), animals were perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissues were deep frozen in liquid nitrogen and serial 8 μm brain coronal frozen sections were cut for histological analyses. In this study the spheres were transplanted only in the Tg2576 mice, because in a previous study we found that a similar procedure of spheres transplantation (ie, from either IL-1raTG or WT newborns) in WT mice did not produce any significant effects on memory functioning and neurogenesis (Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2008).

Cell Lineage Characterization and Quantification of the Transplanted Cells In Vivo

The transplanted cells were detected by immunostaining for BrdU. Sections were incubated with 2 N HCl for 30 min at 37 °C, washed, and incubated with 3% normal goat serum (NGS) for 1 hr at room temperature (RT), followed by incubation with rat anti-BrdU (clone BU1/75 (ICR1), serotec, 1 : 200 dilution) for 48 h at 4 °C. A goat anti-rat IgG secondary antibody, conjugated to Alexa 555, was added for 50 min at RT. To determine the fate of the transplanted cells, sections were double-stained for BrdU and the astrocytic marker GFAP (rabbit anti-GFAP; 1 : 100) or the neuronal marker NeuN (mouse anti–neuronal nuclei; 1 : 50), followed by incubation with goat anti rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies, respectively, and conjugated to Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes) for 50 min at RT. Images were captured using Nikon E-600 and Olympus FV-1000 confocal microscopes and cameras.

BrdU-labeled cells were counted on every sixth 8-μm coronal section, covering the dorsal dentate gyrus in its entire rostro-caudal extension. The total number of transplanted cells was extrapolated for the entire volume of the dentate gyrus (Kempermann et al, 1997). Differentiation of transplanted cells into astrocytes and neurons was determined by immunofluorescent staining for GFAP and NeuN in brains transplanted with BrdU-labeled neurospheres. As no BrdU-labeled cells were also stained for NeuN, quantitative analysis focused on astrocytes. The percentage of graft-derived cells that differentiated into astrocytes was determined by dividing the number of cells manifesting double labeling for BrdU and GFAP by the total number of BrdU-positive cells. All analyses were conducted by an experimenter who was blind with respect to the experimental and control groups.

Evaluation of Growth Factors Expression by Transplanted and Host Cells

In order to evaluate the expression of growth factors by NPCs in vivo, slices were double-stained with BrdU and either BDNF or IGF-1. Staining for BDNF was done on slices that were blocked with Background Buster (Innovex biosciences) for 30 min, followed by incubation with primary antibody diluted in 0.3% triton X-100 for 24 h in RT. Goat anti rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 was added to 1 h in RT. Staining for IGF-1 was carried on slices that were blocked with 20% NGS in 0.1% triton X-100 followed by incubation with primary antibody for 24 h in RT. Donkey anti-Goat conjugated to Alexa 488 was added for 1 h in RT. The percentage of graft-derived cells that express BDNF or IGF-1 was determined by dividing the number of cells manifesting double labeling for BrdU and BDNF or IGF-1 by the total number of BrdU-positive cells. To evaluate possible differences between the expression of BDNF by WT cells and IL-1raTG cells, slides with clear evidence of the transplant were stained with BDNF and the percentages of cells that express BDNF were assessed. In order to explore the possibility that NPCs transplantation induced expression of BDNF by the host tissue, slides of DG areas located far from the transplanted IL-1raTG and WT cells (ie, at least 48 μm away from the last section in which BrdU-labeled cells were identified and further away until the anterior and posterior ends of the DG) were stained with BDNF, and the number of endogenous cells expressing this neurotrophin (but not labeled with BrdU) was calculated in these areas. In parallel, slides from naive and sham-operated mice were also stained with BDNF and positive cells for this neurotrophin were counted in matching areas.

Evaluation of Neurogenesis Levels by Immunostaining to Doublecortin

Slices containing the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus were stained for doublecortin (DCX). Slices were fixed in methanol for 20 min in −20 °C, followed by blocking with 1% BSA in PBS, diluted in 0.1% triton X-100. The primary antibody, anti-DCX (1 : 500; Chemicon), was added for 24 h at 4 °C followed by incubation with the secondary antibody, biotin-conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig IgG, for 2 h at RT and then incubation with 488-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson Laboratories) for 2 h at RT. Counterstaining was done with DAPI.

Evaluation of Plaque Area in Transgenic Mice

Slides were stained with 0.05% thioflavin-S in 50% ethanol in the dark for 8 min. This step was followed by two quick washes with 80% ethanol and then incubation with high concentration of phosphate buffer at 4 °C for 30 min. Slides were washed with distilled water and cover-slipped. Plaque area was measured using image analysis software (Nikon NIS elements) in the entire dorsal hippocampal DG area and in the piriform cortex.

Assessment of Microglia Density and Markers Expression

To evaluate the number and morphology of microglia in all the experimental groups, slides were fixed with 2% PFA, followed by blocking with 3% NGS in 5% BSA. The primary antibody, rabbit anti Iba-1 (1 : 200; Abcam), was added for 24 h at 4 °C. The secondary antibody, goat anti rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes), was added for 1 h at RT. Numbers of Iba-1-positive cells were counted in the entire DG of both hemispheres and the density of microglia cells was calculated. In addition, the number of microglia associated with DG plaques was counted and the ratio of microglia/plaque area was calculated. Microglia were considered to be plaque-associated if the Iba-1 staining of their soma or processes overlapped or was in clear contact with the thioflavin-S labeled plaque. Counting was conducted by an experimenter who was blind with respect to group assignment.

To further characterize the microglia phenotype, slides were blocked with goat serum and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-MHC-II (1 : 50; Chemicon). Secondary goat anti-mouse antibody was added for 1 h in RT. For TNFα staining, slides were fixated in methanol, dried and blocked with 2% BSA. Anti-TNFα (1 : 100; Abcam) was added for 24 h at 4 °C. Secondary donkey anti-goat antibody (Molecular Probes) was added for 1 h at RT. For IL-10 staining, slides were blocked with goat serum, incubated with goat anti-mouse IL-10 antibody (1 : 40; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), washed, and incubated with the secondary donkey anti-goat antibody (Molecular Probes). All slides were counterstained with DAPI.

Intra-Cerebral IL-1ra Administration

Eleven-month-old Tg2576 and control mice were anesthetized with halothane and placed in a stereotaxic instrument. A burr hole was drilled through the skull over the lateral ventricle, 1.5 mm lateral to the midline and in a distance posterior to bregma that was computed by the formula (−0.4–0.66 × (bl−3.8)) mm, where bl is the distance between bregma and lambda. A 30-gauge Alzet brain infusion cannula was inserted into the lateral ventricle (3.2 mm from the skull surface), which was then cemented to three anchoring screws on the skull. A 4-week delivery Alzet osmotic minipump, filled with either IL-1ra (10 μg/day, Amgen, CA) or vehicle (Amgen, CA), was inserted into a subcutaneous pocket in the midscapular area of the back of the mouse, connected via a catheter to the brain cannula. The osmotic minipumps were replaced 2 weeks following their insertion with freshly filled minipumps (because in preliminary experiments we found that 2 weeks is the maximal time that IL-1ra will remain effective within these pumps). At 22–28 days after the initiation of IL-1ra treatment, mice were tested in the fear-conditioning and water maze paradigms (the testing order was counterbalanced, so half of the mice were first tested in the fear conditioning and then in the water maze and the order was reversed for the other half of the animals) and then killed for the assessment of histological and histopathological parameters.

Measurement of Learning and Memory in the Fear-Conditioning Paradigm

The fear-conditioning apparatus consisted of a transparent square conditioning cage (25 × 21 × 18 cm), with a grid floor wired to a shock generator and scrambler (Kinder scientific, U.S.). Mice were placed in the cage for 120 s, and then a pure tone (2.9 kHz) was sound for 20 s, followed by a 2-s, 0.5-mA foot-shock. This procedure was then repeated, and 30 s after the delivery of the second shock mice were returned to their home cage. Forty-eight hours later, fear conditioning was assessed by measuring the time spent in freezing (complete immobility) during exposure to the conditioned stimuli (ie, either the context or the tone), using an automated system (Kinder scientific, USA). The mice tested for contextual fear conditioning were placed in the original conditioning cage, and freezing was measured for 5 min. The mice tested for the auditory-cued fear conditioning were placed in a different context—a triangular-shaped cage with no grid floor. As a control for the influence of the novel environment, freezing was measured for 2.5 min in this new cage, and then the tone was sounded for 2.5 min, during which conditioned freezing was measured. Freezing was also measured during the first 120 s of the conditioning trial, before the tone and shock administration, in order to assess possible strain differences in baseline freezing.

Measurement of Learning and Memory in the Water Maze

Animals were trained in a circular pool (160 cm in diameter) filled with 23±2 °C water mixed with non-toxic gouache paint to make it opaque. In the spatial memory experiment, mice were trained to find the location of a hidden platform, submerged 1 cm below the water surface, using extra maze visual cues. Training consisted of three trials per day, with a 1-h break between trials, for 3 days using a random protocol, in which the entrance point to the maze was varied randomly between trials, and the platform remained in a permanent position. One day following training (ie, on the fourth experimental day) a probe trial was conducted, in which the platform was removed, the mice were placed in the water maze for 60 s, and the number of crossings over the previous location of the platform was recorded. A video camera above the pool was connected to a computerized tracking system (VP118 tracking system, HVS Image, Hampton, England), which monitored the latency to reach the platform in each training trial and the crossings over the platform in the probe trial (refre to studies by Avital et al (2003) and Goshen et al (2009a) for additional details).

Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVAs, followed by the Tukey HSD post hoc analysis, when appropriate. The results of the water maze test were analyzed by three-way ANOVAs, with the trials as a repeated-measures factor.

RESULTS

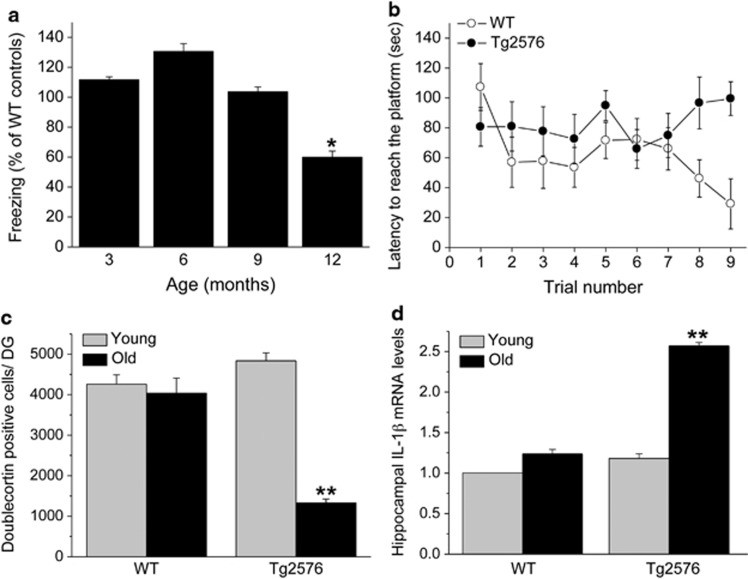

Age of Memory Disturbances Onset in Tg2576 Mice

Previous studies on the age of onset of memory disturbances exhibited by Tg2576 mice reported inconsistent findings, and the effect of age on hippocampal neurogenesis impairments in Tg2576 mice has not been systematically determined. Therefore, we first examined memory functioning and neurogenesis in different age groups of Tg2576 and WT control mice. At 3, 6 and 9 months of age, contextual fear-conditioning memory in Tg2576 mice was similar to their littermate controls, whereas at 12 months of age Tg2576 mice displayed significantly impaired fear conditioning, compared with all other age groups (F(3,11)=178.1, P<0.001) (Figure 1a). In the Morris water maze paradigm, 12-month-old Tg2576 mice also displayed a significant spatial learning impairment compared with their littermate controls (F(3,11)=2.916, P=0.006) (Figure 1b). The latency to reach the platform was not influenced by changed motivation or motor performance because there were no differences in the swimming speed among the groups (P>0.5). At a young age (3 months) there was no difference in hippocampal neurogenesis between Tg2576 mice and their controls; however, at 12 months of age Tg2576 mice displayed markedly reduced neurogenesis. These findings were reflected by a significant strain by age interaction (F(3,1)=24.235, P<0.001) (Figure 1c). Similarly, whereas at 3 months of age there was no difference in the levels of hippocampal IL-1β mRNA expression between Tg2576 mice and their littermate controls, at 12 months of age Tg2576 mice displayed markedly elevated IL-1β mRNA expression, reflected by a significant strain by age interaction (F(3,11)=170.17, P<0.001) (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Age-dependent behavioral and neuro-immune alterations in Tg2576 mice. (a) Fear-conditioning scores in different age groups of Tg2576 mice, presented as percent of WT mice at the corresponding ages. Memory functioning in the Tg2576 mice was normal (ie, ∼100% of control) at 3, 6, and 9 months of age, but it was significantly impaired in 12-month-old mice (n=9/group). (b) In the Morris water maze paradigm, 12-month-old Tg2576 mice displayed a significant spatial learning impairment compared with their littermate controls (n=9/group). (c) Hippocampal neurogenesis, assessed by counting the number of doublecortin-labeled cells in the dentate gyrus, was similar in young (3-month-old) Tg2576 and WT mice, whereas at an older age (12 months) WT mice maintained similar rate of neurogenesis but Tg2576 mice displayed markedly reduced neurogenesis (n=6/group). (d) Hippocampal IL-1β mRNA expression levels were similar in young (3-month-old) Tg2576 and WT mice, whereas at an older age (12 months) WT mice maintained the low expression but Tg2576 mice displayed markedly elevated IL-1β mRNA expression levels (n=8/group). *P<0.05 compared with all other age groups. **P<0.001 compared with all other groups.

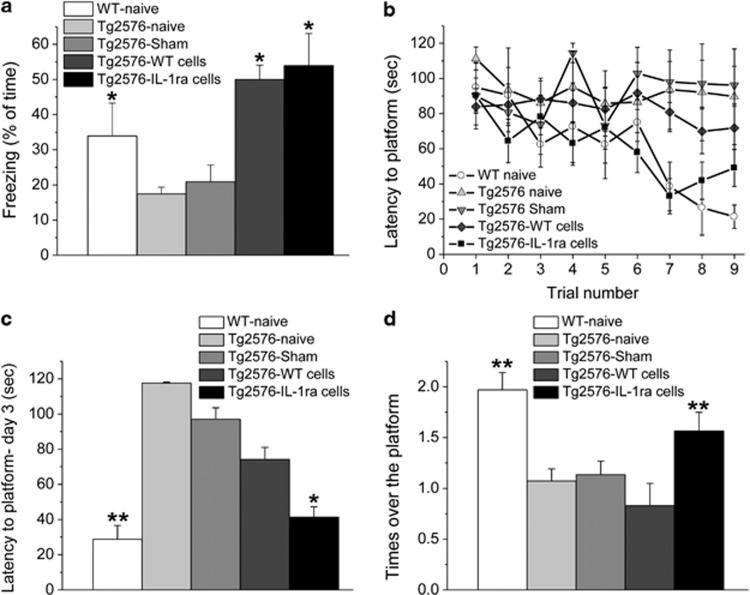

Effects of NPCs Transplantation on Memory Functioning in the Fear Conditioning and Water Maze Paradigms

Memory functioning was assessed in 12-month-old WT naive (untreated) mice and four groups of Tg2576 mice (naive, sham-operated, and transplanted with either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs at 11 months of age). In the contextual fear-conditioning paradigm, naive and sham-operated Tg2576 mice exhibited markedly impaired contextual fear-conditioning memory, as compared with naive WT mice. Transplantation with either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs completely reversed this memory impairment (Figure 2a), as reflected by a significant overall difference among the groups (F(4,24)=6.456, P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of NPCs transplantation on memory functioning. (a) Fear conditioning (reflected by % freezing during the memory retention test) was significantly impaired in naive and sham-operated Tg2576 mice, compared with naive WT mice. Transplantation with either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs completely reversed this memory impairment (n=9/group). (b) In the water maze paradigm, naive, sham-operated and WT NPCs-transplanted Tg2576 mice displayed severely impaired spatial learning and memory compared with the WT naive group. This impairment was completely rescued by transplantation with IL-1raTG NPCs. (c) On the last day of water maze training, naive and sham-operated Tg2576 mice exhibited significantly longer latencies to reach the platform than either naive WT or IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted Tg2576 mice, whereas the WT NPCs-transplanted Tg2576 group did not differ from any of the other Tg2576 groups. (d) In the probe trial, the naive, sham and WT-transplanted NPCs Tg2576 groups displayed significantly fewer crossings over the previous location of the platform than either the WT or the IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted groups. *P<0.05 compared with the Tg2576 naive and sham groups. **P<0.05 compared with the Tg2576 naive, sham and WT-transplanted groups.

In the water maze paradigm, naive and sham-operated Tg2576 mice displayed severely impaired spatial learning and memory, with almost no reductions in the latencies to reach the hidden platform over the entire training period. WT NPCs-transplanted Tg2576 mice also showed marked learning impairment, with limited improvement over trials, but IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted Tg2576 mice were completely rescued from this impairment, displaying reductions in the latency to reach the hidden platform that were similar to those of WT controls (Figure 2b). These findings were reflected by a significant group by trials interaction (F(4,38)=3.990, P<0.05). The latency to reach the platform was probably not influenced by changes in motivation or motor performance because there were no differences in the swimming speed among the groups (average velocity=18.6–20.3 cm/s; P>0.5). To further elucidate these differences, an additional analysis was conducted, comparing the latencies to reach the platform on the last day of training (Figure 2c), demonstrating significant overall difference among the groups (F(4,38)=5.059, P<0.05), with complete reversal of the memory impairment in IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted mice (as compared with naive and sham mice) and partial reversal in WT NPCs-transplanted mice (which were not different from either naive and sham-operated mice or from IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted mice). In the probe trial, comparison of the number of crossings over the previous location of the platform showed a significant difference between the groups (F(4,23)=10.596, P<0.01), with complete rescue of the memory impairment in IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted Tg2576 mice, which were significantly different from all other groups of Tg2576 mice and not different from the WT mice (Figure 2d).

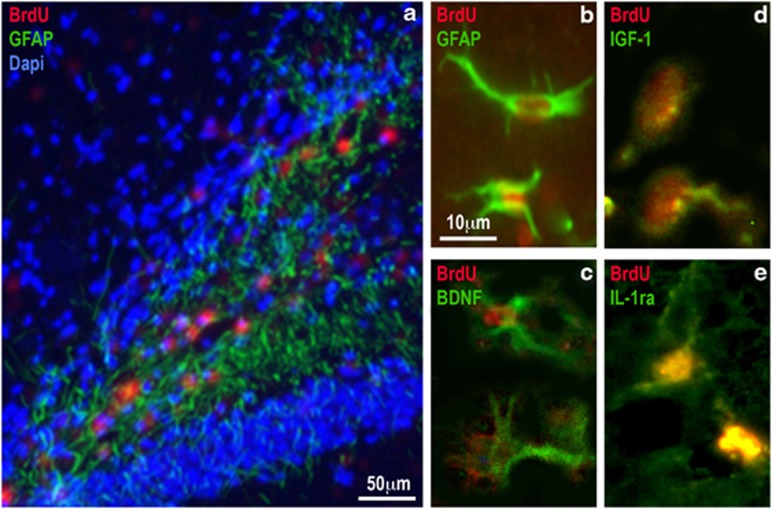

Localization and Characterization of the Transplanted NPCs

The distribution and differentiation of transplanted NPCs within the host brain were examined after completion of all behavioral tests (ie, 5–6 weeks post transplantation). NPCs were labeled with BrdU before transplantation and could be clearly detected in the host dentate gyrus (DG) area (including the hilus, granular and molecular layers) (Figure 3a). The average numbers (±SEM) of WT and IL-1raTG BrdU-labeled cells in the DG of the Tg2576 mice were 8088 ±318 and 8043 ±341, respectively. To evaluate the pattern of differentiation of the transplanted NPCs, slides were double-stained for BrdU, together with glial or neuronal markers. Immunohistochemistry and quantification of double-labeled cells revealed that 78% of the BrdU-labeled cells expressed the astrocytic marker GFAP (Figures 3a and b). In contrast, no double-staining for BrdU and the neuronal marker NeuN was observed in any cell (data not shown). This pattern of differentiation was evident for either WT- or IL-1raTG-transplanted cells. To further characterize the transplanted cells, slides were double-stained for BrdU and the neurotrophic factors BDNF and IGF-1. The percentages of cells that expressed these markers were calculated among the BrdU-positive cells, showing that 85% of the transplanted cells expressed BDNF (Figure 3c) and 72% of the cells expressed IGF-1 (Figure 3d), with no discernible differences between WT and IL-1raTG NPCs. Most of the NPCs obtained from IL-1raTG mice (but none from WT mice) expressed hIL-1ra (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Localization and characterization of transplanted NPCs. (a) A representative picture of the hippocampal DG 1 month following transplantation of BrdU-labeled NPCs. BrdU (red)-positive cells were mainly found in the hilus of the DG. Staining to both BrdU and the astrocytic marker GFAP (green) revealed that 78% of the BrdU transplanted cells expressed GFAP. (b) A representative picture in higher magnification of two cells, expressing both BrdU (red) and GFAP (green). (c) A representative picture taken from an adjacent slice, showing two transplanted cells that express both BrdU (red) and BDNF (green). (d) A representative picture showing two transplanted cells that express both BrdU (red) and IGF-1 (green). (e) A representative picture of two cells expressing both BrdU (red) and hIL-1ra (green). Such cells were found only in brains transplanted with NPCs derived from IL-1raTG mice.

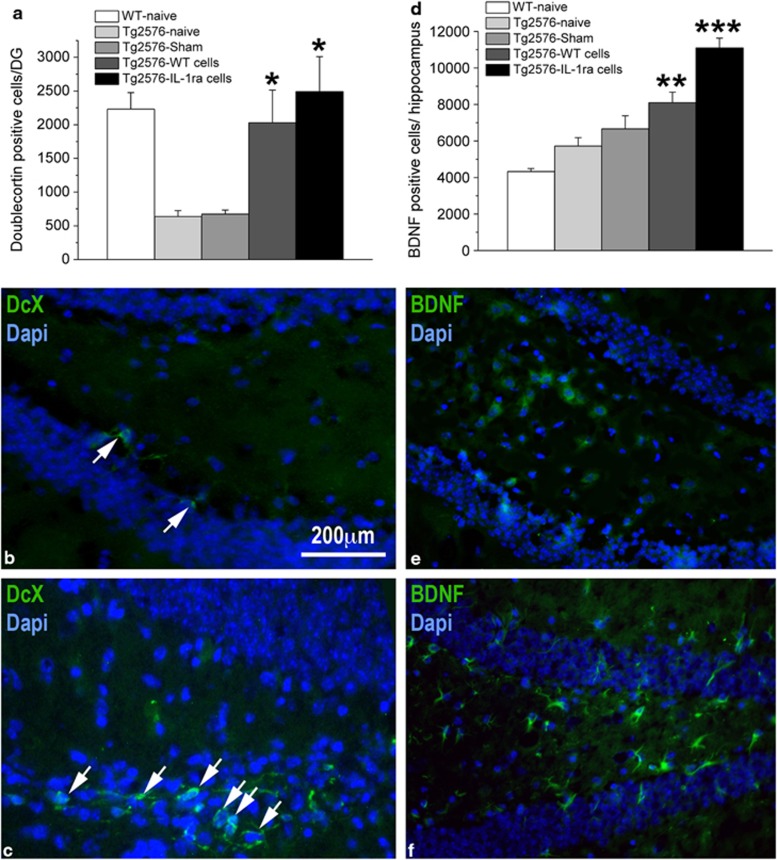

Effects of NPCs Transplantation on Hippocampal Neurogenesis and BDNF Expression

As a first attempt to explore possible mechanisms that underlie the effects of NPCs transplantation on learning and memory functioning we assessed the number of adult-born neurons (doublecortin (DCX)-labeled) and BDNF-expressing cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Immunohistochemistry for DCX revealed a significant difference among the groups (F(4,98)=15.656; P<0.0001) (Figures 4a and c and d). Specifically, both naive and sham-operated Tg2576 mice displayed suppressed hippocampal neurogenesis, compared with the WT naive group, and this effect was completely rescued in Tg2576 mice transplanted with either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs. It should be noted that NPCs transplantation affected neurogenesis from endogenous stem cells/NPCs, as the exogenously transplanted NPCs did not express DCX. Analysis of the number of BDNF-expressing endogenous cells (ie, measured in hippocampal areas not containing BrdU-labeled transplanted NPCs) also revealed a significant difference among the groups (F(4,193)=39.938, P<0.001) (Figures 4b). Specifically, Tg2576 mice transplanted with WT NPCs displayed greater number of BDNF-positive endogenous cells than WT mice, and IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted mice showed significantly higher number of BDNF-positive cells than all other groups.

Figure 4.

Effects of NPCs transplantation on hippocampal neurogenesis and BDNF expression. (a) Hippocampal neurogenesis, determined by counting the number of DCX-labeled cells, was significantly suppressed in naive and sham-operated Tg2576 mice, as compared with WT mice, but transplantation of either WT- or IL-1raTG-derived NPCs completely rescued this impairment (n=8/group). (b) A representative picture of the DG from a sham-operated mouse demonstrates the labeling of only two DCX-labeled adult-born cells (green; marked by white arrows). (c) A representative picture of the DG from a Tg2576 mouse transplanted with IL-1raTG-derived NPCs demonstrates the labeling of numerous DCX-labeled cells (green; marked by white arrows). (d) The number of BDNF-labeled endogenous cells in Tg2576 mice was elevated by transplantation of WT NPCs, as compared with WT naive mice (n=8/group). This number was further increased by transplantation of NPCs derived from IL-1raTG mice, rising to a level significantly greater than in all other groups (including the WT NPCs-transplanted group). (e) A representative picture demonstrating a relatively low number of BDNF-expressing cells (green) in the DG of a naive WT mouse, as compared with (f) A representative picture of the DG from a Tg2576 mouse transplanted with IL-1raTG NPCs, demonstrating a relatively high number of BDNF-expressing cells (green). *P<0.05 compared with the Tg2576-naive and Tg2576-sham groups. **P<0.05 compared with the WT-naive group. ***P<0.05 compared with all other groups.

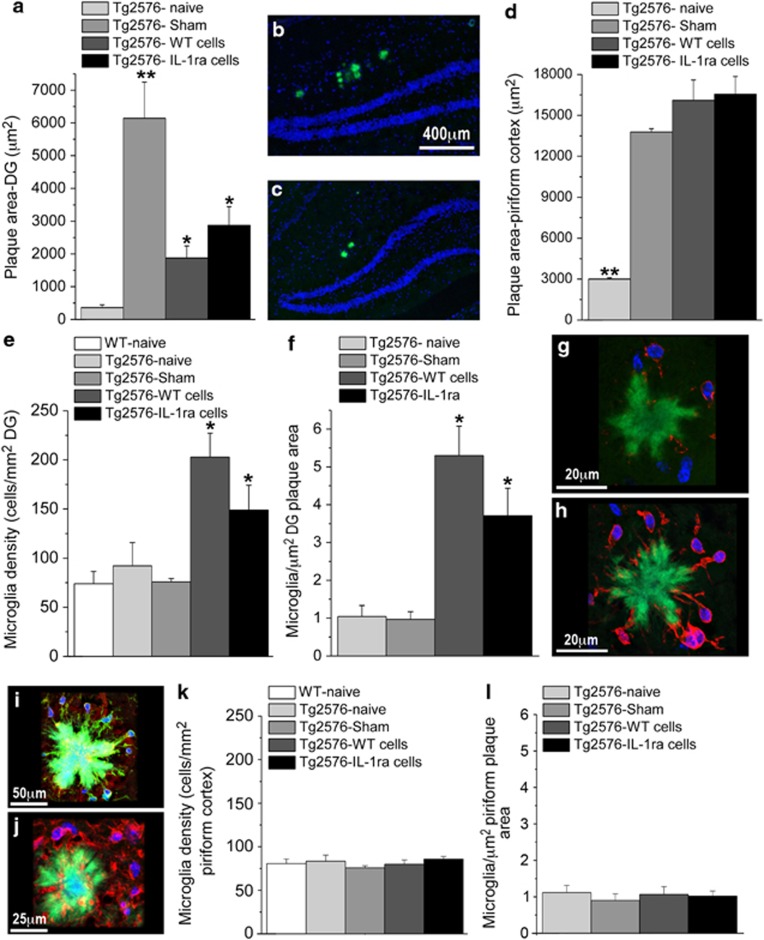

Effects of NPCs Transplantation on Plaque Area and Microglial Density and Phenotype

As the formation of amyloid plaques constitutes the neuropathological hallmark of AD and may be involved in the neurobehavioral alterations in Tg2576 mice, we used thioflavin staining to evaluate the area covered by plaques in the DG, as well as in the piriform cortex, which is particularly prone to the development of plaques in AD (Kim et al, 2012). A significant difference in DG plaque area was found between the Tg2576 groups (F(3,8)=96705.193, P<0.001) (Figures 5a–c). Specifically, sham-operated Tg2576 mice displayed a dramatic increase in plaque area, as compared with naive mice, whereas both WT and IL-1raTG NPCs transplantation significantly reduced the operation-related increase in plaque area, although plaque area in these groups was still significantly larger than in naive mice. Plaque area in the piriform cortex also differed among the groups (F(3,8)=101. 449, P<0.001) (Figure 5d), but in this case all operated groups (sham-operated or transplanted with either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs) displayed greater plaque area than the naive group.

Figure 5.

Effects of NPCs transplantation in Tg2576 mice on plaque area and microglia density. (a) At 5-6 weeks post NPCs transplantation, the area of the DG covered with plaques was significantly increased in sham-operated Tg2576 mice, compared with naive Tg2576 mice. Transplantation with either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs significantly reduced this operation-induced plaque area increase, although plaque area in the transplanted groups was still significantly greater than in the naive group (n=6/group). (b) A representative picture of thioflavin-labeled plaques (green staining) in the hippocampal DG (delineated by blue Dapi staining) of a sham-operated Tg2576 mouse as well as (c) a mouse transplanted with IL-1raTG NPCs. (d) The area of the piriform cortex covered with plaques was significantly increased in the sham-operated mice, as well as in mice transplanted with WT or IL-1raTG NPCs, compared with naive mice. (e) Microglia density within the DG (cells per mm2), as well as (f) the number of microglia associated with plaques (cells per μm2 plaque area) were significantly increased in mice transplanted with WT or IL-1raTG NPCs (n=6/group). (g) A representative confocal microscope image of Iba-1-labeled microglia (red) associated with a thioflavin-labeled plaque (green) in a sham-operated Tg2576 mouse, and (h) in an IL-1raTG-transplanted Tg2576 mouse. (i) A representative confocal image of plaque-associated microglia with double-staining for Iba-1 (green) and MHCII (red). (j) A representative confocal image of IL-10 labeled plaque-associated cells in IL-1raTG-transplanted Tg2576 mouse. (k) No group differences were found in microglial density (cells per mm2) and (l) the number of microglia associated with plaques (cells per μm2 plaque area) in the piriform cortex (n=6/group). *P<0.05 compared with the Tg2576-naive, Tg2576-sham and WT-naive (when applicable) groups. **P<0.05 compared with all other groups.

Microglia, which are responsible for most (but not all) production of brain IL-1, have key roles in the formation and degradation of plaques in AD (Farfara et al, 2008; Lynch, 2009; Weitz and Town, 2012), and may be also involved in cognitive functioning and neurogenesis (Blank and Prinz, 2013; Ekdahl et al, 2009; Yirmiya and Goshen, 2011). Therefore, we assessed the density of microglia in the hippocampal DG and piriform cortex, as well as the number of microglia specifically associated with plaques. Significant group differences were found in DG microglial density (number of microglia/DG area) (Figure 5e) (F (4,48)=6.368.P<0.001). Specifically, transplantation of either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs significantly increased microglia density, as compared with all other groups. Particularly, high density of microglia was observed in association with the plaques (Figure 5f), with significant differences among the groups (F(3,45)=20.615, P<0.001), stemming from increased number of microglia/plaque area in mice transplanted with either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs, as compared with naive and sham-operated mice (Figures 5g and h). Plaque-associated microglia in all groups displayed activated morphology (round cell bodies with reduced processes ramification) and some microglia were shown to extend processes into the plaque area (Figures 5g and h). As a first attempt to characterize the phenotype and polarization of the plaque-associated microglia, immunostainings for the M1-associated markers MHCII and TNFα, as well as the M2-associated marker IL-10 were conducted. In all groups ∼20% of the microglia expressed MHC-II (Figure 5i), but almost no expression of TNFα was observed. Importantly, although in naive and sham-operated mice no cells were found to express the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10, in the WT and IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted groups almost all cells around the plaques were positive for this cytokine (Figure 5j), suggesting a shift towards an alternative (M2) microglial phenotype. Analysis of microglial density and the number of microglia specifically associated with plaques in the piriform cortex revealed no parallel group differences, ie, the microglial density and the number of microglia per plaque were overall similar to those measured in the DG of naive and sham-operated mice, and there were no increases in these parameters by NPCs transplantation (Figures 5k and l).

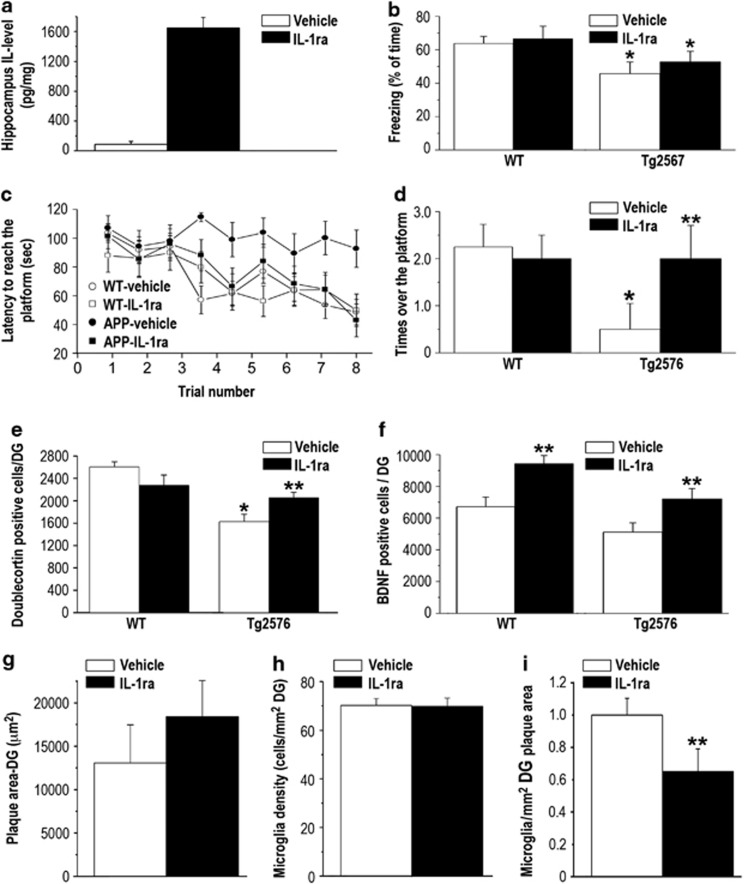

Effects of Chronic IL-1ra Administration on Memory Functioning, Neurogenesis, BDNF Expression, Plaque Area and Microglial Density

To examine the net effect of IL-1 blockade (ie, not in the context of the NPCs transplantation) we studied the effects of chronic i.c.v. administration of hIL-1ra, using the same paradigms and timing employed in the experiment on NPCs transplantation. The chronic administration of hIL-1ra resulted in high levels of this cytokine in the hippocampus, as compared with almost no IL-1ra in vehicle-treated mice hippocampus (t(5)=5.64, P<0.001) (Figure 6a). In the fear-conditioning paradigm, Tg2576 mice displayed a significant memory impairment, which was not prevented by the IL-1ra treatment, as reflected by a significant strain effect (F(3,22)=10.761, P<0.05) (Figure 6b). In the water maze paradigm, vehicle-treated Tg2576 mice displayed a severe learning and memory impairment, with no improvement in the latency to reach the hidden platform over the entire training period, but in contrast with the result in the fear-conditioning task this impairment was completely rescued by the IL-1ra treatment, equating the performance of the treated Tg2576 mice to that of the WT groups. This finding was reflected by a strain by treatment by trials interaction (F(3,24)=5.906, P<0.05) (Figure 6c). The latency to reach the platform was not influenced by changed motivation or motor performance because there were no differences in the swimming speed between the groups (P>0.5). Spatial memory was further assessed by a probe trial 1 day following the completion of the 3-day training by placing the mice in the water maze without the platform and measuring the number of passes over the former location of the platform. Vehicle-treated Tg2576 mice displayed a marked impairment in this task, which was completely reversed by IL-1ra treatment, reflected by a significant strain by treatment interaction (F(3,24)=4.32. P<0.05) (Figure 6d).

Figure 6.

Effects of pharmacological blockade of IL-1 signaling by chronic i.c.v. administration of IL-1ra. (a) hIL-1ra levels in the hippocampus were significantly elevated following chronic i.c.v. administration of hIL-1ra (n=5-6/group). (b) Fear-conditioning memory, expressed as % freezing during the retention test, was significantly impaired in both vehicle- and IL-1ra-treated Tg2576 groups, ie, the IL-1ra treatment had no effect on memory impairment in this task (n=9/group). (c) In the Morris water maze, Tg2576 mice treated with vehicle showed severe spatial memory impairment compared with the WT groups, with no improvement over the entire training period. This deficit was completely rescued in Tg2576 mice treated with IL-1ra, which displayed performance similar to the groups of WT mice. (d) In the probe test of the water maze, Tg2576 mice treated with vehicle showed almost no crossing over the previous location of the platform, and this deficit was also completely rescued in Tg2576 mice treated with IL-1ra, which performed similarly to the groups of WT mice. (e) Hippocampal neurogenesis, expressed as the number of doublecortin (DCX)-labeled cells in the DG, was markedly reduced in Tg2576 mice treated with vehicle, and this reduction was significantly attenuated in Tg2576 mice treated with IL-1ra. (f) The number of BDNF-labeled cells in the DG was significantly increased in both WT and Tg2576 treated with IL-1ra. (g) Plaque area and (h) microglial density in the DG were not altered following chronic i.c.v. administration of IL-1ra. (i) The number of plaque-associated microglia in the DG was significantly reduced following chronic i.c.v. administration of IL-1ra. *<0.05 compared with both groups of WT controls. **<0.05 compared with the vehicle-treated mice of the same strain.

At the completion of the behavioral tests, mice were perfused and the levels of DG neurogenesis and BDNF expression were examined. Vehicle-administered Tg2576 mice exhibited significantly reduced level of neurogenesis, compared with WT mice (injected with either saline or IL-1ra) and this reduction was significantly (although not completely) prevented by IL-1ra administration. These findings were reflected by a significant strain by treatment interaction (F(3,21)=6.19, P<0.05) (Figure 6e). The IL-1ra treatment induced significant elevations in the number of BDNF-expressing cells in both WT and Tg2576 mice (F (1,18)=5.803, P<0.05) (Figure 6f). IL-1ra treatment produced no effects on DG plaque area (Figure 6g) or microglial density (Figure 6h) (P>0.1). The number of plaque-associated microglia was significantly reduced in IL-1ra-treated mice (t(6)=11.53, P<0.001) (Figure 6i).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that intra-hippocampal transplantation of NPCs with transgenic over-expression of IL-1ra can rescue the cognitive disturbances exhibited by mice with AD-like pathology and increase the production of the plasticity-related molecule BDNF. Similar, but less-consistent effects were also produced by transplantation of WT NPCs as well as by blockade of IL-1 signaling using chronic intra-cerebral administration of IL-1ra. Furthermore, the present findings demonstrate for the first time that transplantation of either WT or IL-1raTG NPCs can rescue the severe impairment in hippocampal neurogenesis displayed by AD-like mice, and that a similar, albeit more partial amelioration of the neurogenesis deficit can be produced by pharmacological blockade of brain IL-1 signaling.

As currently approved drugs for AD provide limited long-term benefits, and the development of novel drugs that target Aβ or tau pathology has been slow and frustrating, it has been suggested that stem cell transplantation could offer a promising therapeutic approach to AD (Chen and Blurton-Jones, 2012). In some neurological diseases the transplantation of stem cells or their differentiated derivatives, such as NPCs, can cause functional improvement by replacing lost cell, particularly neurons. However, in AD, in which the impairments in neuronal systems, synaptic connectivity and neurochemical functionality are widespread, it is more likely that stem cells will be efficacious via the secretion of trophic factors that influence the endogenous cells or via their anti-inflammatory activity (Chen and Blurton-Jones, 2012; De Feo et al, 2012). The present study are in agreement with the findings of a previous study, demonstrating that WT NPCs ameliorate the cognitive disturbances in triple transgenic mice (3 × Tg-AD) that express pathogenic forms of amyloid precursor protein, presenilin, and tau (Blurton-Jones et al, 2009), and together these studies support the notion that NPCs transplantation indeed has promising effects on AD-induced impairments in learning, memory and neuroplasticity, mediated by the secretion of compounds that block endogenous disruptors of these processes (such as IL-1) and compounds that promote these processes (such as BDNF), as detailed below.

The results of the present study corroborate our previous demonstrations (Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2011; Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2008) that transplanted WT and IL-1raTG NPCs readily survive in the host hippocampus for many weeks and differentiate mainly into astrocytes (in a preliminary experiment we found that the transplanted cells can survive for >9 months post transplantation). In a previous report (Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2008), we showed that the transplanted IL-1raTG NPCs dramatically increase the levels of IL-1ra in the hippocampus, but not in other regions of the brain. In the AD-like mice this elevation was functionally important for spatial memory, because this type of memory was markedly improved only by transplantation of IL-1raTG NPCs, whereas contextual fear-conditioning memory and neurogenesis were improved by transplantation of both WT and IL-1raTG NPCs. This pattern of results suggests (but does not prove) that transplantation-induced neurogenesis facilitation may account for the improvement in contextual memory, which is more dependent on neurogenesis than spatial memory (Hernández-Rabaza et al, 2009; Meshi et al, 2006), whereas the effect of IL-1 blockade in the water maze task is probably mediated by another process (eg, the enhanced BDNF production).

This conclusion is validated by the present findings that i.c.v. administration of IL-1ra (which elevated hippocampal IL-1ra levels to those found in IL-1raTG NPCs-transplanted mice) beneficially affected spatial memory but not fear conditioning, suggesting a specific sensitivity of spatial memory to disruption by IL-1 in AD context, which has not been reported hereto. The current finding of beneficial effects of IL-1 signaling blockade extends our previous report that transplantation of IL-1raTG NPCs ameliorate the cognitive and neurogenic impairments induced by chronic stress (Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2008), as well as the recently reported beneficial cognitive effects of IL-1 blockade in 3 × Tg-AD mice (Kitazawa et al, 2011). In the latter study, IL-1 signaling was blocked by peripheral administration of anti-IL-1R blocking monoclonal antibodies, but as no such antibodies were found within the brain, the localization of these effects (peripheral vs central) remained uncertain. The present results, demonstrating increased IL-1β mRNA expression in the hippocampus of aging Tg2576 mice, and rescue of the AD-associated hippocampal-dependent spatial memory impairment by NPCs that secrete IL-1ra specifically in this structure, indicate that the effects of IL-1 blockade occur directly within the hippocampus.

The effects of WT and IL-1raTG NPCs transplantation may be mediated by several mechanisms, including increases in hippocampal neurogenesis and BDNF production, as well as reductions in plaque burden and alterations in microglia status. Mounting evidence indicates that transgenic models of AD are associated with impairments in hippocampal neurogenesis, which may at least partially underlie the cognitive disturbances exhibited in such models (Mu and Gage, 2011; Shruster et al, 2010). The results of the present study are the first to show that NPCs transplantation into the hippocampus of AD-like mice completely rescues their neurogenesis disturbances. Blockade of IL-1 signaling using IL-1ra administration also partially rescued the neurogenesis impairment, consistently with the known detrimental effects of elevated hippocampal IL-1 levels on neurogenesis and the ability of genetic, cellular and pharmacological IL-1 blockade procedures to prevent neurogenesis suppression in various conditions associated with elevated brain IL-1 levels (Ben Menachem-Zidon et al, 2008; Goshen et al, 2008; Koo and Duman, 2008).

In view of the critical role of neurotrophic factors, particularly BDNF, in memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis, as well as findings that in brains of AD patients BDNF levels are decreased, dysregulation of neurotrophic activity was proposed as an important mechanism contributing to AD pathology (Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). Consistently, neurotrophin expression and secretion by various types of stem cells was proposed as an important mechanism for their ability to counteract cognitive and neuropathological symptoms of AD in transgenic models (Chen and Blurton-Jones, 2012). Indeed, a study using BDNF gain-of-function and loss-of-function demonstrated that the production of BDNF by transplanted NPCs is critical for their beneficial effects on cognitive functioning and synaptic plasticity (Blurton-Jones et al, 2009). The results of the present study demonstrate that in addition to the expression of BDNF by the transplanted NPCs, the transplantation induced a significant increase in the number of endogenous cells that express BDNF. Furthermore, the transgenic IL-1ra over-expression potentiated the NPCs-induced increases in BDNF expression, and treatment with IL-1ra was also capable of promoting BDNF expression by endogenous cells. These findings are consistent with the known suppressive effects of IL-1 on BDNF expression (Barrientos et al, 2003; Barrientos et al, 2004; Tong et al, 2008) and corroborate the possible role of elevated hippocampal BDNF levels in promoting functional recovery in AD.

Although the formation of amyloid plaques represents the hallmark pathological symptom of AD, the relationship between plaques and cognitive functioning is still intensely debated (Golde et al, 2011; Karran et al, 2011). In the present study, comparisons between naive and sham-operated Tg2576 mice revealed that the surgery (along with the halothane anesthesia, which was given only to the operated animals) produced a widespread increase in amyloid plaque area, in accordance with previous research demonstrating that both surgery and anesthesia can enhances amyloidopathy in AD-like mice (Lu et al, 2010; Tang et al, 2013). In contrast with its dramatic effect on amyloid plaques, surgery had no discernible effect on memory and neurogenesis. These findings dramatically demonstrate dissociation between plaque formation and neurobehavioral disturbances (at least in the early stage of the disease exhibited by the animals in this study). Interestingly, NPCs transplantation (either WT or IL-1raTG) significantly reduced the surgery-induced increase in plaque formation, whereas IL-1 blockade did not seem to affect plaque area (reflected by no difference between the effects of WT vs IL-1raTG NPCs transplantation and no effect of the IL-1ra infusion, consistently with a previous report of no effect of IL-1 blockade on APP levels (Oprica et al, 2007)). The effects of NPCs transplantation on plaque burden may be related to the increase in the overall density of microglia, and particularly the increase in the number of activated microglia associated with the plaques. The mechanism for this effect of the NPCs is not clear, but it may be suggested that the transplanted cells constitute an immune challenge that induces microglia proliferation and/or migration into the hippocampus, as well as promotion of their activation against the amyloid plaques. This conclusion is strengthened by the findings that the effects of NPCs transplantation on both plaque formation and plaque-associated microglial number were specific to the location of the transplantation, as they were evident in the DG but not the piriform cortex. As shown previously, microglia can effectively clear amyloid plaques (Lee and Landreth, 2010), and the recruitment of microglial with alternative (M2) morphology was specifically associated with improved phagocytic functioning (Medeiros et al, 2013). The morphological relations between microglia and plaques observed here, and the M2-like phenotype exhibited by these cells suggest the possibility of such a process in the current study. Previous studies indicated that IL-1 signaling can either interfere with (Heneka et al, 2013; Heneka et al, 2010a) or facilitate (Shaftel et al, 2008; Shaftel et al, 2007) microglia-mediated plaque degradation and phagocytosis. In the present study, pharmacological administration of IL-1ra was found to reduce the number of microglia associated with plaques, but this reduction was not associated with significant effects on plaque area. Thus, the relations between IL-1 signaling, microglial status and the formation and degradation of plaques should be further investigated.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate that hyper-secretion of IL-1 within the hippocampus contributes to AD-associated deficits in at least some forms of memory (particularly spatial memory). Furthermore, the present findings extend previous reports, demonstrating that transplantation of WT NPCs or long-term pharmacological IL-1 blockade can ameliorate AD-associated neurobehavioral deficits, by demonstrating that combination of these approaches exceeds the beneficial potential of each approach by itself. The idea that genetic manipulations before transplantation could enhance the therapeutic potential of NPCs, by turning them into ‘Trojan horses' delivering specific proteins to the AD-afflicted brain, has been suggested (Chen and Blurton-Jones, 2012) but not tested so far. Our results provide the first example for the use of genetically manipulated NPCs in the treatment of AD, indicating that supplementation of NPCs therapy with the delivery of an anti-inflammatory agent, particularly IL-1ra, can potentiate the beneficial effects of NPCs transplantation on cognition, possibly by inducing the expression of BDNF by endogenous hippocampal cells.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by The Legacy Heritage Bio-Medical Program of the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 430/09), and in part by grants from the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation (grant number 270804), the Israel Ministry of Health (grant number 2985) and Cure Alzheimer's Fund. We thank Dr Mikhal Cohen, Sys Kochavi and Erez Yirmiya for help with specific technical aspects of the study.

Author contributions

Dr Ofra Ben Menachem-Zidon designed the work that led to the submission, acquired data, had an important role in interpreting the results, drafted the manuscript and approved the final version. Mr Yair Ben Menahem acquired data and approved the final version. Dr Tamir Ben-Hur had an important role in interpreting the results, revised the manuscript and approved the final version. Dr Raz Yirmiya conceived and designed the work that led to the submission, had an important role in interpreting the results, drafted the manuscript and approved the final version.

Disclaimer

The corresponding author confirms that he has had full access to the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan SM, Tyrrell PJ, Rothwell NJ. Interleukin-1 and neuronal injury. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:629–640. doi: 10.1038/nri1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avital A, Goshen I, Kamsler A, Segal M, Iverfeldt K, Richter-Levin G, et al. Impaired interleukin-1 signaling is associated with deficits in hippocampal memory processes and neural plasticity. Hippocampus. 2003;13:826–834. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Sprunger DB, Campeau S, Higgins EA, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA downregulation produced by social isolation is blocked by intrahippocampal interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Neuroscience. 2003;121:847–853. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Sprunger DB, Campeau S, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF. BDNF mRNA expression in rat hippocampus following contextual learning is blocked by intrahippocampal IL-1beta administration. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;155:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Menachem-Zidon O, Avital A, Ben-Menahem Y, Goshen I, Kreisel T, Shmueli EM, et al. Astrocytes support hippocampal-dependent memory and long-term potentiation via interleukin-1 signaling. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:1008–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Menachem-Zidon O, Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben Menahem Y, Reinhartz E, Ben Hur T, et al. Intrahippocampal transplantation of transgenic neural precursor cells overexpressing interleukin-1 receptor antagonist blocks chronic isolation-induced impairment in memory and neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2251–2262. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur T, Ben-Menachem O, Furer V, Einstein O, Mizrachi-Kol R, Grigoriadis N. Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the growth, fate, and motility of multipotential neural precursor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:623–631. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank T, Prinz M. Microglia as modulators of cognition and neuropsychiatric disorders. Glia. 2013;61:62–70. doi: 10.1002/glia.22372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton-Jones M, Kitazawa M, Martinez-Coria H, Castello NA, Muller FJ, Loring JF, et al. Neural stem cells improve cognition via BDNF in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13594–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901402106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WW, Blurton-Jones M. Concise review: can stem cells be used to treat or model Alzheimer's disease. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2612–2618. doi: 10.1002/stem.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Feo D, Merlini A, Laterza C, Martino G. Neural stem cell transplantation in central nervous system disorders: from cell replacement to neuroprotection. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:322–333. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328352ec45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl CT, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Brain inflammation and adult neurogenesis: the dual role of microglia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein N, Einstein O, Cohen ME, Brill L, Lavon I, Ben-Hur T. Time limited immunomodulatory functions of transplanted neural precursor cells. Glia. 2013;61:140–149. doi: 10.1002/glia.22420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farfara D, Lifshitz V, Frenkel D. Neuroprotective and neurotoxic properties of glial cells in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:762–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Wu MD, Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, LaFerla FM, Olschowka JA, et al. Sustained interleukin-1β overexpression exacerbates tau pathology despite reduced amyloid burden in an Alzheimer's mouse model. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5053–5064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4361-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde TE, Schneider LS, Koo EH. Anti-aβ therapeutics in Alzheimer's disease: the need for a paradigm shift. Neuron. 2011;69:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldgaber D, Harris HW, Hla T, Maciag T, Donnelly RJ, Jacobsen JS, et al. Interleukin 1 regulates synthesis of amyloid beta-protein precursor mRNA in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7606–7610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Avital A, Kreisel T, Licht T, Segal M, Yirmiya R. Environmental enrichment restores memory functioning in mice with impaired IL-1 signaling via reinstatement of long-term potentiation and spine size enlargement. J Neurosci. 2009a;29:3395–3403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5352-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, et al. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:717–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Yirmiya R. Interleukin-1 (IL-1): a central regulator of stress responses. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009b;30:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS. Alzheimer's—looking beyond plaques. F1000 Med Rep. 2011;3:24. doi: 10.3410/M3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, Stanley LC, Ling C, White L, MacLeod V, Perrot LJ, et al. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7611–7615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer's disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature. 2013;493:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Nadrigny F, Regen T, Martinez-Hernandez A, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Terwel D, et al. Locus ceruleus controls Alzheimer's disease pathology by modulating microglial functions through norepinephrine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010a;107:6058–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, O'Banion MK, Terwel D, Kummer MP. Neuroinflammatory processes in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm. 2010b;117:919–947. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0438-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Rabaza V, Llorens-Martín M, Velázquez-Sánchez C, Ferragud A, Arcusa A, Gumus HG, et al. Inhibition of adult hippocampal neurogenesis disrupts contextual learning but spares spatial working memory, long-term conditional rule retention and spatial reversal. Neuroscience. 2009;159:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, McNamara M, Fedorchak K, Hsiao K, Hyman BT. APPSw transgenic mice develop age-related A beta deposits and neuropil abnormalities, but no neuronal loss in CA1. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:965–973. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer's disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:698–712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Gage FH. Genetic influence on neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10409–10414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Lee JE, Park SK, Lee KW, Seo JS, Im JY, et al. Analysis of differential plaque depositions in the brains of Tg2576 and Tg-APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer disease. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:492–502. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.8.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa M, Cheng D, Tsukamoto MR, Koike MA, Wes PD, Vasilevko V, et al. Blocking IL-1 Signaling rescues cognition, attenuates tau pathology, and restores neuronal beta-catenin pathway function in an Alzheimer's disease model. J Immunol. 2011;187:6539–6549. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JW, Duman RS. IL-1beta is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708092105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Landreth GE. The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:949–960. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu L, Barger SW, Griffin WS. Interleukin-1 mediates pathological effects of microglia on tau phosphorylation and on synaptophysin synthesis in cortical neurons through a p38-MAPK pathway. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1605–1611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01605.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu L, Kang J, Sheng JG, Barger SW, Mrak RE, et al. Neuronal-glial interactions mediated by interleukin-1 enhance neuronal acetylcholinesterase activity and mRNA expression. J Neurosci. 2000;20:149–155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00149.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Wu X, Dong Y, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Xie Z. Anesthetic sevoflurane causes neurotoxicity differently in neonatal naive and Alzheimer disease transgenic mice. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1404–1416. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d94de1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundkvist J, Sundgren-Andersson AK, Tingsborg S, Ostlund P, Engfors C, Alheim K, et al. Acute-phase responses in transgenic mice with CNS overexpression of IL-1 receptor antagonist. Am J Physiol. 1999;276 (3 Pt 2:R644–R651. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.3.R644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MA. The multifaceted profile of activated microglia. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;40:139–156. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matousek SB, Ghosh S, Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, Olschowka JA, O'Banion MK. Chronic IL-1β-mediated neuroinflammation mitigates amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease without inducing overt neurodegeneration. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:156–164. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9331-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAfoose J, Baune BT. Evidence for a cytokine model of cognitive function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:741–749. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros R, Kitazawa M, Passos GF, Baglietto-Vargas D, Cheng D, Cribbs DH, et al. Aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 stimulates alternative activation of microglia and reduces Alzheimer disease-like pathology in mice. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1780–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshi D, Drew MR, Saxe M, Ansorge MS, David D, Santarelli L, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis is not required for behavioral effects of environmental enrichment. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:729–731. doi: 10.1038/nn1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y, Gage FH. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and its role in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:85. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara AH, Tuszynski MH. Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:209–219. doi: 10.1038/nrd3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprica M, Hjorth E, Spulber S, Popescu BO, Ankarcrona M, Winblad B, et al. Studies on brain volume, Alzheimer-related proteins and cytokines in mice with chronic overexpression of IL-1 receptor antagonist. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:810–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak Y, Gilboa A, Ben-Menachem O, Ben-Hur T, Soreq H, Yirmiya R. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors reduce brain and blood interleukin-1beta production. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:741–745. doi: 10.1002/ana.20454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachal Pugh C, Fleshner M, Watkins LR, Maier SF, Rudy JW. The immune system and memory consolidation: a role for the cytokine IL-1beta. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainero I, Bo M, Ferrero M, Valfre W, Vaula G, Pinessi L. Association between the interleukin-1alpha gene and Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:1293–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaftel SS, Griffin WS, O'Banion MK. The role of interleukin-1 in neuroinflammation and Alzheimer disease: an evolving perspective. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, Olschowka JA, Miller JN, Johnson RE, O'Banion MK. Sustained hippocampal IL-1 beta overexpression mediates chronic neuroinflammation and ameliorates Alzheimer plaque pathology. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1595–1604. doi: 10.1172/JCI31450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JG, Ito K, Skinner RD, Mrak RE, Rovnaghi CR, Van Eldik LJ, et al. In vivo and in vitro evidence supporting a role for the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 as a driving force in Alzheimer pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:761–766. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shruster A, Melamed E, Offen D. Neurogenesis in the aged and neurodegenerative brain. Apoptosis. 2010;15:1415–1421. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0491-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachida Y, Nakagawa K, Saito T, Saido TC, Honda T, Saito Y, et al. Interleukin-1 beta up-regulates TACE to enhance alpha-cleavage of APP in neurons: resulting decrease in Abeta production. J Neurochem. 2008;104:1387–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JX, Mardini F, Janik LS, Garrity ST, Li RQ, Bachlani G, et al. Modulation of murine Alzheimer pathogenesis and behavior by surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;257:439–448. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318269d623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong L, Balazs R, Soiampornkul R, Thangnipon W, Cotman CW. Interleukin-1 beta impairs brain derived neurotrophic factor-induced signal transduction. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1380–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz TM, Town T. Microglia in Alzheimer's Disease: It's All About Context. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:314185. doi: 10.1155/2012/314185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MD, Hein AM, Moravan MJ, Shaftel SS, Olschowka JA, O'Banion MK. Adult murine hippocampal neurogenesis is inhibited by sustained IL-1β and not rescued by voluntary running. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya R, Goshen I. Immune modulation of learning, memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:181–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]