Abstract

Förster resonance energy transfer was used to monitor the dynamic conformations of mononucleosomes under different chromatin folding conditions to elucidate the role of the flexible N-terminal regions of H3 and H4 histones. The H3 tail was shown to partake in intranucleosomal interactions by restricting the DNA breathing motion and compacting the nucleosome. The H3 tail effects were mostly independent of the ionic strength and valency of the ions. The H4 tail was shown to not greatly affect the nucleosome conformation, but did slightly influence the relative population of the preferred conformation. The role of the H4 tail varied depending on the valency and ionic strength, suggesting that electrostatic forces play a primary role in H4 tail interactions. Interestingly, despite the H4 tail’s lack of influence, when H3 and H4 tails were simultaneously clipped, a more dramatic effect was seen than when only H3 or H4 tails were clipped. The combinatorial effect of H3 and H4 tail truncation suggests a potential mechanism by which various combinations of histone tail modifications can be used to control accessibility of DNA-binding proteins to nucleosomal DNA.

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, DNA is packaged into a highly organized chromatin structure. This compact DNA-protein assembly limits the accessibility of genomic DNA to transcription factors and helps to regulate gene expression in cells. The nucleosome is the fundamental building unit of eukaryotic chromatin. It assumes a highly organized structure with 147 basepairs of DNA tightly wrapped around a histone octamer complex (1). Each nucleosome contains two copies of four types of histone proteins, i.e., H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. In addition to participating in the formation of a nucleosome core particle, these proteins all contain an extensive N-terminal tail region that is not included in the core structure of a nucleosome. These tails extend distinctively from the nucleosome core and are populated with positively charged amino acids, such as lysine (K) and arginine (R). The histone tails participate in inter- and intranucleosomal interactions and play a significant role in regulating the accessibility of genomic DNA (2). Posttranslational modification on the charged residues of histone tails, such as lysine acetylation, can have a profound effect on gene expression (3). These tail modifications are capable of altering the chromatin structure, affecting the electrostatic interactions with DNA and core histone regions. Specific tail modifications also exhibit different affinities to particular remolding proteins and transcription factors that further modulate gene expression (4,5).

Although all core histone protein tails are known to contribute to the chromatin compaction, H3 and H4 tails are of particular interest due to their extended length and high lysine content (1). H3 and H4 histone proteins form a tetramer within the core of a nucleosome. Simultaneous removal of the N-terminal domains of H3 and H4 histones is known to affect the DNA-binding affinity and DNA exposure (2,6). Acetylation and partial removal of H3 and H4 tails have both been shown to play a role in heterochromatin formation and regulating gene expression (7,8). The N-terminus of H3 tails exit the nucleosome near the DNA entry and exit sites. Although the H3 tail domain was conventionally conceived to be structureless, a recent NMR study shows that the H3 tail assumes a relatively unperturbed folding (9). Studies using model nucleosome arrays have further revealed that H3 tails participate in the nucleosomal compaction process, primarily through intranucleosomal interactions (10–12).

The N-terminal tail of histone H4, on the other hand, is close to the central dyad position of the DNA wrapped around the histone octamer. The H4 tail exhibits an overall flexible conformation, with the exception of the region between Ala-15-Lys-20, which favors the formation of a α-helical domain (13). The H4 tails have been shown to participate in chromatin formation mainly through internucleosomal interactions, for example via the direct contacts between the tails of H4 and H2A histones (14,15). Despite our current knowledge of H3 and H4 tails in modulating the overall chromosome conformation, the comprehensive model detailing all the roles of H3 and H4 tails under different conditions remains unresolved. It is also not clear from current literature whether the H3 and H4 tails may interact or the extent to which modifications of one tail affects the other.

Chromatin is known to assume a dynamic conformation under different ionic strengths (16). Monovalent and divalent cations, e.g., Na+, K+, and Mg2+, are commonly found in the cell nucleus. Different types of cations and cation concentrations mimic the chromatin environments at different transcriptional states and stages of development. Understanding how H3 and H4 tails affect chromosome conformation at the nucleosomal level is therefore of critical importance to understanding the mechanisms involved in cellular activities like transcription and DNA replication.

This work focuses on elucidating the effects of the flexible N-terminal region of histone H3 and H4 on intranucleosomal interactions under different chromatin folding conditions. We monitored the conformational and dynamic features of a mononucleosome using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) as measured by time-domain fluorescent spectroscopy. By selectively clipping the N-terminal tails of histone H3 and H4 proteins, we identified the mechanistic role of those flexible domains in regulating the dynamic DNA end breathing motion, as well as the detailed nucleosomal conformation. The flexible end of the H3 tail is shown to partake in intranucleosomal interactions that serve to limit the accessibility of the nucleosome by restraining the DNA breathing motion and generating more compact nucleosome conformations. The flexible region of the H4 tail is shown to not greatly affect the nucleosome conformations but can slightly affect the extent to which each conformation is preferred. Interestingly, despite the lack of influence displayed by the H4 tails, when both H3 and H4 tails are truncated, the effects on the DNA breathing motion are considerably more pronounced than when only H3 or only H4 tails are truncated. The detailed roles of H3 and H4 tails in nucleosomal conformation and dynamics vary from each other and exhibit a certain dependence on the type of cations present. The changes in the nucleosome conformation and breathing motion caused by histone tail truncation shed light on a mechanism in which histone tail acetylation can facilitate access of DNA-binding proteins to nucleosomal DNA.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of fluorescently labeled mononucleosome samples

Nucleosome conformations were monitored using fluorescently labeled mononucleosomes. A FRET dye pair, i.e., fluorescein (FAM) and tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA), was introduced to the two ends of a DNA fragment using polymerase chain reaction. The DNA sequence chosen for this study was a 157-bp Widom-601 sequence (17). This sequence has the largest known binding affinity to a histone octamer and therefore the reconstituted nucleosome adopts a uniform centered positioning pattern with 5 bp linker DNA evenly distributed on the DNA entry and exit sites (Fig. 1). The energy transfer efficiency between the two terminal ends of the linker DNA can therefore be used to measure the conformational details of the nucleosome.

Figure 1.

A schematic drawing of the closed and open conformations of a nucleosome that originates from the DNA end breathing motion observed at low salt concentrations. The H3 tails are shown as dashed lines and the H4 tails as solid lines (one H4 tail is only partially visible due to the orientation of the nucleosome). A symmetric breathing motion is pictured here, but a possible alternative model exists in which the DNA breathing occurs asymmetrically. In this case, only one of the DNA ends breathes away from the histone core at a time. The circles at the DNA ends depict the locations of the FRET dye pair.

Histone octamers were refolded using four types of recombinant Xenopus laevis histone proteins, i.e., H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. These four types of recombinant proteins were individually expressed and purified using an established protocol (18). The plasmids that encode for the N-terminus truncated H3 and H4 proteins were prepared using a site-directed mutagenesis strategy. The truncated H3 protein had 27 amino acids (ARTKQTARKSTGGKAPRKQLATKAARK) removed from its N-terminus. The truncated H4 protein had 10 amino acids (SGRGKGGKGL) removed from its N-terminus. The truncated H3 and H4 proteins were expressed recombinantly and purified using the same conditions as the wild-type (WT) histone proteins (18). Truncated H3 and H4 octamers were prepared by substituting the corresponding WT histone proteins with the truncated versions.

Four types of mononucleosomes, i.e., WT, H3-truncated (ΔH3), H4-truncated (ΔH4), and H3-and-H4-truncated (ΔH3ΔH4), were prepared by mixing fluorescently labeled DNA fragments with WT, truncated H3, truncated H4, and truncated H3 and H4 octamers, respectively. Each type of nucleosome was reconstituted with two differently labeled DNA fragments to obtain both donor-only (FAM)- and donor-acceptor (FAM-TAMRA) labeled mononucleosomes. All of the nucleosomes were reconstituted using the established salt gradient approach (18). The picture of the polyacrylamide gel of the mononucleosomes is depicted in Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material. WT, ΔH3, and ΔH4 mononucleosomes exhibit a single band. The smearing and very faint high band that is seen for ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes is most likely due to the differences between the two nucleosomal conformations being more dramatic for ΔH3ΔH4 than they are for the other mononucleosomes. The slight variation in the electrophoretic motilities between the different types of nucleosomes is likely to originate from the overall effect of both reduced molecular weight due to tail truncation (increased electrophoretic mobility) and the conformational changes of mononucleosomes (more open conformation leading to reduced electrophoretic mobility).

FRET measurements

FRET experiments are commonly used to obtain spatial conformations of biological molecules at subnanometer resolution. The FRET efficiency is related to the separation between the FRET dye pairs as in Eq. 1

| (1) |

In this expression E is the energy transfer efficiency, r is the distance between the donor and the acceptor labels, i.e., the distance between the DNA ends in this work, and R0 is the Förster distance, which was characterized to be 5.03 nm using a 17 bp short DNA fragment with a known end-to-end distance (Section S1.1 in the Supporting Material). The anisotropy of donor- and acceptor-labeled nucleosomes was consistently lower than 0.2 indicating that the distance calculated from Eq. 1 should have <10% error (Section S1.2 in the Supporting Material). These small values of anisotropy also suggests that both dyes can be considered as freely rotating and therefore the Förster distance can be considered as a constant throughout the experiments performed in this study. The FRET efficiency (E) was obtained using time-domain fluorescence lifetime spectroscopy and Eq. 2

| (2) |

In this expression τd and τda are the fluorescence lifetimes of donor-only and donor-acceptor mononucleosomes, respectively. The labeling efficiency of TAMAR-labeled DNA used in the donor-acceptor mononucleosomes was found to be >99% as detailed in Section S1.3 in the Supporting Material. Therefore, the lifetimes of donor-acceptor-labeled samples do not have interference from donor-only samples. Using Eq. 1, these two values can provide detailed spatial information about the ends of the DNA that are bound to a histone octamer. Compared with steady-state FRET experiments, time-domain measurements can provide additional molecular details by differentiating distinctive fluorescence species that coexist in the sample. The time-domain fluorescence decay curve can routinely resolve the relative intensity of two fluorescent species (19). The detailed approach of performing time-domain fluorescent lifetime measurements and the data analysis procedure is available in Section S1.4-1.5 in the Supporting Material. In the case of a mononucleosome, instead of assuming a homogenous conformation, the nucleosome assumes a dynamic conformation originating from the DNA end breathing motion at low salt concentrations (Fig. 1) (20,21). Mononucleosomes labeled with the FAM-TAMRA FRET dye pair exhibited two distinct fluorescence states. The shorter fluorescence lifetime corresponds to closed-state nucleosomes and the longer fluorescent lifetimes correspond to open-state nucleosomes. The relative abundance of these two conformations (f1) can be used to reveal the dynamic equilibrium of the formed mononucleosomes.

This study aims to measure the FRET occurring between the donor and the acceptor on the same mononucleosome, but it is also possible that aggregation of mononucleosomes could bring a donor and an acceptor dye together close enough for FRET to occur. To account for this, a control experiment was performed in which FRET due to aggregation was monitored using a sample that contained 50% donor-only mononucleosomes and 50% acceptor-only mononucleosomes. We found that FRET due to aggregation does not contribute to the measured energy transfer over the concentrations presented here (Section S1.6 and Fig. S9 in the Supporting Material).

Results and Discussion

Histone H3 tails restrain the DNA end motion and limit nucleosome accessibility

Among the four types of histone proteins, histone H3 is unique in at least two aspects. First, it has the longest N-terminal tail with 59 amino acids, populated with positively charged residues. Second, the N-terminal region of histone H3 forms direct contacts with the DNA fragment wrapped around a nucleosome. The H3 tails pass through the minor groove of the DNA segment near the DNA entry and exit sites on a nucleosome. Histone tail clipping and acetylation have both been found to similarly affect nucleosome stability in various biochemical and biophysical assays (8,10–12,22,23). This similarity is due to both tail clipping and acetylation decreasing the number of positive charges on histone tails. The primary function of the tail clipping is to reveal the role the histone tail plays in dictating the nucleosome conformation, but the results from the tail clipping can provide insight as to how acetylated histone tails would affect conformation. However, for specifically evaluating the effect of acetylation, it would be more apt to use an acetylation mimic such as lysine to glutamine mutations or to use acetylated histones (10,25). First, we specifically evaluated the conformational and dynamic changes of a mononucleosome induced by H3 tail clipping alone.

A typical nuclear monovalent cationic concentration is around 100 mM (26). However, increasing monovalent cationic strength facilitates the destabilization and eventual dissociation of the octamer, which is important for providing access for DNA-binding proteins. Nucleosomes undergo a dynamic equilibrium between an open and closed conformation that is also important for providing access to DNA, as shown in Fig. 1. This dynamic equilibrium is referred to as the DNA breathing motion and is considered to originate from the transient contacts between the histone octamer surface and the DNA ends entering/exiting from a nucleosome. It is characterized by DNA end-to-end distance of the closed (d1) and open (d2) conformations of the nucleosome and by the relative population of the closed-state nucleosome. The fraction of the nucleosomes in the closed state (f1) reflects the equilibrium of the DNA end regions. An apparent equilibrium constant, accounting for the DNA breathing motion, can be calculated as in Eq. 3

| (3) |

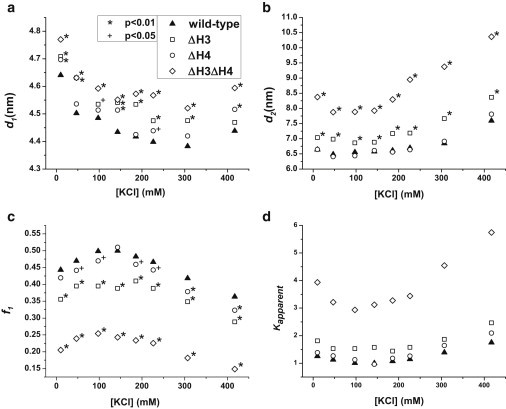

WT and ΔH3 mononucleosomes undergo a similar compaction process at low monovalent cationic strengths (<200 mM) as illustrated in Fig. 2. This compaction is reflected by an increase in the fraction of nucleosomes in the closed state and a slight reduction in the DNA end-to-end distance of the closed state. At concentrations between 100 and 200 mM K+ both the WT and ΔH3 nucleosomes reach maximum compaction. Under the range of monovalent cationic concentrations studied here, the two conformations observed for ΔH3 nucleosomes differ by 2.3–3.9 nm in the DNA end-to-end distance, as depicted in Fig. 2, a and b (Fig. S12, a and b). Based on this distance, an estimated 4–7 basepairs are involved in the DNA breathing motion for each side of WT nucleosomes and 5–8 basepairs are involved for ΔH3 nucleosomes. This estimation is based on a model in which DNA unwrapping occurs symmetrically, with the same number of basepairs being involved on both sides of the nucleosome. There is some evidence, however, that suggests DNA unwraps asymmetrically (27,28). If this is the case, then the number of basepairs involved would be different than what is reported here. The number of basepairs reported here is smaller than what has been previously reported in protein-binding and single-molecule experiments, but agrees with recent findings using small-angle x-ray scattering (29). Comparing the conformations of WT and ΔH3 mononucleosomes, both the closed state and the open state of ΔH3 mononucleosomes show a larger DNA end-to-end distance. As KCl concentration increases, the population of open-state nucleosomes increases further. Multiple conformational states can contribute to the open state conformation including DNA breathing motion, dimer destabilization, and dimer dissociation (30). Although our labeling strategy cannot discriminate between these mechanisms, they all play a similar role in enhancing DNA accessibility.

Figure 2.

(a) The distance between the DNA ends for mononucleosomes in the closed conformation, d1, under different monovalent cationic conditions. (b) The distance between the DNA ends for mononucleosomes in the open conformation, d2. (c) The fraction of nucleosomes in the closed conformation, f1. (d) The apparent equilibrium constant, Kapparent, characterizing the DNA breathing motion under different KCl concentrations. The legend is the same for all four graphs. A t-test is applied to compare the statistical significance of the measurements in (a–c) for the four mononucleosomes. Each data point that is statistically different than WT is labeled based on the confidence level. The confidence levels are (∗) for 99% (p = .01) and (+) for 95% (p = .05). Unlabeled data points in (a–c) are not statistically different than WT at the 95% confidence level. f1 is the only parameter used to calculate Kapparent therefore the statistical significance is the same in (d) as it is in (c). Error bars are omitted from these graphs to avoid overcrowding. Graphs that include the error bars are available in Figs. S12, S14, and S16.

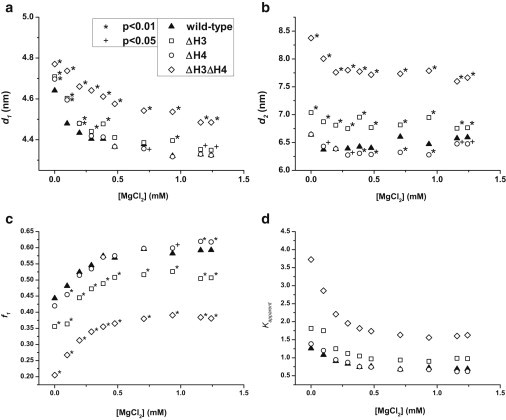

We further evaluated the effects of H3 tails with the presence of a divalent cation, i.e., Mg2+. Mg2+ is found in cell nucleus and is known to facilitate the compaction of a nucleosome array or a chromatin fiber. Understanding how Mg2+ mediates the nucleosomal interaction can help to elucidate the role of histone tails during the folding process. The in vivo Mg2+ concentration varies from tissue to tissue and the reported values range from 0.2–1.5 mM (31). With increasing Mg2+ concentration, WT and ΔH3 mononucleosomes undergo a compaction process with increased population of nucleosomes in the closed state and a more compact closed-state nucleosome, as depicted in Fig. 3, a–c (Fig. S13, a–c). The compaction process saturates at around 0.5 mM Mg2+ independent of the presence of the H3 tail domain, as illustrated in Fig. 3 c.

Figure 3.

(a) The distance between the DNA ends for mononucleosomes in the closed conformation, d1, under different divalent cationic conditions. (b) The distance between the DNA ends for mononucleosomes in the open conformation, d2. (c) The fraction of nucleosomes in the closed conformation, f1. (d) The apparent equilibrium constant, Kapparent, characterizing the DNA breathing motion under different MgCl2 concentrations. The legend is the same for all four graphs. A t-test is applied to compare the statistical significance of the measurements in (a–c) for the four mononucleosomes. Each data point that is statistically different than WT is labeled based on the confidence level. The confidence levels are (∗) for 99% (p = .01) and (+) for 95% (p = .05). Unlabeled data points in (a–c) are not statistically different than WT at the 95% confidence level. f1 is the only parameter used to calculate Kapparent therefore the statistical significance is the same in (d) as it is in (c). Error bars are omitted from these graphs to avoid overcrowding. Graphs that include the error bars are available in Figs. S13, S15, and S17.

The difference in nucleosome conformations and dynamic equilibrium, between the WT and the ΔH3 mononucleosomes as observed in this study, unambiguously suggests that a positively charged H3 tail participates in stabilizing the contacts between a DNA fragment and a histone octamer surface. H3 tails can restrain the DNA end breathing motion by holding the DNA end fragments closer to the octamer. With the loss of H3 tails, the conformation of both the closed and the open state of the nucleosome becomes looser as seen in Fig. 3, a and b (Fig. S13, a and b). Additionally, the presence of H3 tails increases the energetic barrier for the DNA end fragments to breathe away from a histone octamer surface. As a result, an increased population of nucleosomes (6–12%) in the open state is found in the ΔH3 mononucleosome samples as shown in Fig. 3 c (Fig. S13 c). In addition, an increased number of DNA basepairs (0.5–1 bp from each side) are estimated to be involved in the DNA end breathing motion. The differences between the WT and ΔH3 mononucleosomes under divalent conditions are similar to those observed in monovalent cationic solutions. The positive surface charges on the H3 tail are expected to remain close to the DNA entry and exit sites, restraining the DNA end motion and enhancing the nucleosomal stability through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding. Increasing ionic strength does not significantly alter the intranucleosomal interactions involving histone H3 tails. These findings suggest that the H3 tail region is likely to remain close to the histone octamer surface under the cationic concentrations being explored here and consistently stabilizes the DNA-histone octamer contacts.

The equilibrium constant (Kapparent) of a ΔH3 mononucleosome, characterizing the DNA breathing motion, is around 1.4 times that of a WT nucleosome near the physiological condition as seen in Fig. 3 d (Fig. S13 d). This finding suggests that the truncation of H3 tails can significantly enhance the DNA end breathing motion and increase the accessibility of nucleosomal DNA fragments by at least 50%. It would be expected that H3 tail acetylation would likewise increase accessibility. Based on the number of residues truncated, the pertinent lysines known to get acetylated are H3K9, H3K14, and H3K18 (32). The variation in DNA accessibility can affect the efficiency of many molecular events, e.g., DNA replication and transcription, which requires protein binding to a DNA fragment. The increased distance between DNA ends in the open conformation serves to enhance the accessibility of DNA fragments near the entry and exit sites. Although there is also an increase in the distance between DNA ends in the closed conformation, it is likely too small to have significant biological bearings because DNA-binding proteins would be expected to preferentially access the open nucleosomal conformation.

Histone H4 tails assume different roles in nucleosomal accessibility dependent on the type of cations present

The N-terminal H4 tails exit the core nucleosome on its top/bottom surface and has been shown to be primarily involved in internucleosomal interactions forming direct contacts with neighboring nucleosomes in a nucleosome array (33). Although the H4 tail assumes a disordered structure in general, it contains a sequence stretch that has a strong propensity to form a α-helical structure (13). We truncated only the first 10 amino acids from the N-terminus of a histone H4 to avoid this region. The clipped peptide sequence has three positively charged amino acids and is not located in the close vicinity of the structured region within the H4 tail.

The removal of H4 N-terminal tails does not affect the nucleosome conformation when the buffer only contains monovalent cations. As illustrated in Fig. 2, a and b (Fig.S14, a and b), the two conformations, i.e., the open and the closed state of a nucleosome, are essentially identical to the WT nucleosomes. The fraction of nucleosomes in the closed conformation, on the other hand, exhibits a weak dependence on the H4 tail domain by favoring the open-state nucleosome slightly more than WT as illustrated in Fig. 2 c (Fig. S14 c). The apparent equilibrium constant of a ΔH4 mononucleosome is found to be similar, but slightly higher (∼10%) than that of a WT mononucleosome as shown in Fig. 2 d (Fig. S14 d). At low concentrations of KCl, the ΔH4 mononucleosome has a similar compaction pattern to the WT mononucleosome and both reach their maximum compaction at around 140 mM KCl. Over the range of 10 to 140 mM KCl, WT mononucleosomes exhibit a 13% increase in the value of f1, whereas ΔH4 mononucleosomes show a 22% increase in f1. Thus, ΔH4 mononucleosomes show a greater sensitivity to the KCl gradient than WT.

Similar to the WT mononucleosomes, the ΔH4 mononucleosome undergoes an Mg2+-induced compaction process featuring a further closure of the closed-state nucleosome and an enhancement in the population of the closed-state nucleosomes. Like that seen for KCl, the removal of the H4 tail region does not significantly affect the conformation of nucleosomes in the closed state, but there is a slight decrease (0.1–0.3 nm) in the end-to-end distance of the open state at moderate to high Mg2+ concentrations, as shown in Fig. 3, a and b (Fig. S15, a and b). In addition, with the removal of the H4 tail, an increased population (3–5%) of nucleosomes in the closed state is observed at Mg2+ concentrations above 0.9 mM as shown in Fig. 3 c (Fig. S15 c). The introduction of Mg2+ seems to alter the role of histone H4 tails on nucleosomal conformation and equilibrium. Instead of suppressing the DNA breathing motion as with the presence of monovalent salt, the H4 tail seems to increase accessibility of a nucleosome complex by increasing the fraction of nucleosomes in the open state and increasing the end-to-end distance of the open-state nucleosome with the introduction of divalent counterions.

Although H4 tails are known to primarily participate in internucleosomal interactions, our results suggest that they can also be involved in intranucleosomal interactions. However, the effect of the H4 tails are smaller than what was seen for H3 tails. The H4 tail effects on the nucleosomal accessibility, although small, are interesting because they vary depending on the types of cations that exist in the solution. The H4 tail domains have been shown to be in close vicinity to the central dyad region of the DNA and are relatively far away from the DNA entry/exit site of the nucleosome, which we were directly monitoring in our experiments (1). The change in the role played by the H4 tail for different valency cations suggests the flexible end of the H4 tail may take on different conformations under different ionic conditions. This suggests that electrostatic interactions are the primary contributor to the H4 tail interactions. This type of conformational transition can be important in terms of understanding the role of H4 tails in mediating internucleosomal interaction and facilitating chromosome compaction.

Combinatorial role of H3 and H4 tails in limiting accessibility of mononucleosomes

Surprisingly, despite H3 and H4 tails being spatially distant from each other, the simultaneous truncation of both H3 and H4 tails has a much larger effect on the conformation and dynamics of the nucleosome than H3 and H4 tail effects combined. Under monovalent conditions, the distance between DNA ends is increased for both the open and closed conformation when both H3 and H4 tails are removed. However, the conformational change is much more significant for the nucleosomes in the open state as shown in Fig. 2 b (Fig. S16 b). The DNA end-to-end distance increases compared to WT by 1.3–2.5 nm for ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes, which represents a 20–37% increase in the distance of WT. Although a similar trend was observed with H3 tail clipping, the difference is much smaller (0.3–0.8 nm). A similar scenario is seen for the relative population of nucleosomes in the closed state. For ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes, there are 50% fewer nucleosomes in the closed state as there are for WT, as depicted in Fig. 2 c (Fig. S16 c). This equates to a Kapparent that is on average three times larger than that of WT. A reduction in the fraction of nucleosomes in the closed state was also seen for ΔH3 mononucleosomes, but just as for the distance between DNA ends in the open conformation, truncating both H3 and H4 tails makes this change more severe. The Kapparent for ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes is twice as large as that of ΔH3 mononucleosomes. In addition, as can be seen in Fig. 2 d (Fig. S16 d), Kapparent continues to increase with increasing KCl concentrations with the Kapparent for ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes increasing at a greater rate than what is seen for other mononucleosomes. This suggests that nucleosome destabilization mechanisms such as dimer destabilization may be occurring more rapidly for ΔH3ΔH4 nucleosomes.

The trends seen for monovalent conditions are similar to those seen for divalent conditions. Mononucleosomes with both H3 and H4 truncated undergo an Mg2+-induced compaction process similar to that of WT, ΔH3, and ΔH4 mononucleosomes. As seen in Fig. 3 c, all four types of mononucleosomes show an increase in the relative population of nucleosomes in the closed state with a plateau reached at Mg2+ concentrations >0.5 mM. For ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes, this plateau occurs with an f1 value of ∼0.39, which is 0.2 lower than the f1 value of WT mononucleosomes. This difference in f1 equates to a Kapparent that is 2.3 times larger for ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes when compared to WT mononucleosomes. This represents an additional increase beyond the increase seen when only H3 tails are truncated, as the Kapparent for ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes is on average 1.7 times larger than that of ΔH3. In addition, the Mg2+-induced compaction process causes a decrease in the DNA end-to-end distance in the closed and open conformations for all four types of mononucleosomes studied, as shown in Fig. 3, a and b. For ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes, the change in DNA end-to-end distance for the closed state on average is minor (0.14 nm larger than WT). However, the increase in DNA end-to-end distance for the open state compared to WT is significant with an average increase of 1.25 nm or 19%.

All three parameters used to quantify the dynamic conformation of a mononucleosome (f1, d1, and d2) suggested that the DNA of ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes was the most accessible of the four types of mononucleosomes studied in this work. WT and ΔH4 mononucleosomes were the least accessible, followed by ΔH3 and then ΔH3ΔH4 mononucleosomes. The increased accessibility arises primarily from the larger population of nucleosomes in the open state and an increase in the DNA end-to-end distance of the open state. The differences seen in the DNA end-to-end distance of the closed state were small and it is unlikely they have any biological significance. Given that the effects of the H4 tail were also small, and that H4 tails slightly increased the accessibility under divalent cationic conditions, whereas H3 tails decreased the accessibility, one would expect nucleosomes with both tails truncated to have accessibility similar to ΔH3 nucleosomes. This is not what is seen however, as ΔH3ΔH4 nucleosomes are the most accessible. This finding suggests that both H3 and H4 can contribute to intranucleosome interactions that serve to limit accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. H3 tails contribute to accessibility by themselves. H4 tails do not limit accessibility by themselves but rather contribute to accessibility through synergistic effects with H3 tails.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the flexible N-terminal region of histone H3 contributes more than the flexible N-terminal region of H4 to the conformation and equilibrium of mononucleosomes. Histone H3 tails are located close to the DNA fragments that enter and exit a nucleosome and provide additional constraints by preventing the DNA breathing motion. The changing nucleosome conformation with increasing ionic strength is similar for all four nucleosomes studied here. These changes are likely due to electrostatic interactions between the DNA and the histone octamer core. The role played by H3 tails is mostly independent of the ionic strength and the valency of the ions. However, the role played by H4 tails in the accessibility of the nucleosome varies depending on the ionic strength and the valency of the ion. This observation suggests that H4 tail may adopt a different folding in the presence of different cations and that the H4 tail interactions are due at least partially to electrostatic forces. The result that H3 tails play a larger role than H4 tails in intranucleosomal interactions agrees with previously reported results (8,11), but here we elucidate the mechanism behind these interactions as well as the detailed effects on the conformation and equilibrium of the mononucleosome.

Even though H3 tails have a larger effect than H4 tails, when both H3 and H4 tails are truncated, the conformational and equilibrium changes are greater than what is seen for truncating H3 or H4 tails separately. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that this combinatorial effect has been reported, where H4 tail truncation significantly contributes to intranucleosomal interactions, but only when H3 tails are also truncated. This combinatory effect suggests a mechanism in which histone tail acetylation can be used to determine varying degrees of accessibility of the nucleosomal DNA to proteins such as transcription factors. It has been shown that H3 and H4 tails can cross talk with each other, where the addition of an epigenetic mark on one tail can alter the likelihood of the addition of an epigenetic mark on another tail (34). Here, we showed that dual tail modifications can also more significantly affect the nucleosome structure than the modifications of a single tail.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Tim Richmond in ETH, Zurich for generously sharing with us the expression plasmids of histone proteins.

This project was supported by the American Chemical Society (PRF# 50918-DNI7) and Purdue Showalter’s Trust (11098479).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Richmond T.J., Davey C.A. The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature. 2003;423:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature01595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polach K.J., Lowary P.T., Widom J. Effects of core histone tail domains on the equilibrium constants for dynamic DNA site accessibility in nucleosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:211–223. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenuwein T., Allis C.D. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wysocka J., Swigut T., Allis C.D. A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature. 2006;442:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature04815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu J., Xu W. Histone H3R17me2a mark recruits human RNA polymerase-associated factor 1 complex to activate transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:5675–5680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114905109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brower-Toland B., Wacker D.A., Wang M.D. Specific contributions of histone tails and their acetylation to the mechanical stability of nucleosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos-Rosa H., Kirmizis A., Kouzarides T. Histone H3 tail clipping regulates gene expression. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:17–22. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tóth K., Brun N., Langowski J. Chromatin compaction at the mononucleosome level. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1591–1598. doi: 10.1021/bi052110u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato H., Gruschus J., Bai Y. Characterization of the N-terminal tail domain of histone H3 in condensed nucleosome arrays by hydrogen exchange and NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15104–15105. doi: 10.1021/ja9070078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X., Hayes J.J. Acetylation mimics within individual core histone tail domains indicate distinct roles in regulating the stability of higher-order chromatin structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:227–236. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01245-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng C., Lu X., Hayes J.J. Salt-dependent intra- and internucleosomal interactions of the H3 tail domain in a model oligonucleosomal array. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33552–33557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kan P.-Y., Lu X., Hayes J.J. The H3 tail domain participates in multiple interactions during folding and self-association of nucleosome arrays. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:2084–2091. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02181-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang D., Arya G. Structure and binding of the H4 histone tail and the effects of lysine 16 acetylation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:2911–2921. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01487g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kan P.-Y., Caterino T.L., Hayes J.J. The H4 tail domain participates in intra- and internucleosome interactions with protein and DNA during folding and oligomerization of nucleosome arrays. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:538–546. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01343-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorigo B., Schalch T., Richmond T.J. Nucleosome arrays reveal the two-start organization of the chromatin fiber. Science. 2004;306:1571–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1103124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grigoryev S.A., Woodcock C.L. Chromatin organization - the 30 nm fiber. Exp. Cell Res. 2012;318:1448–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowary P.T., Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luger K., Rechsteiner T.J., Richmond T.J. Preparation of nucleosome core particle from recombinant histones. Methods Enzymol. 1999;304:3–19. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakowicz J.R. 3rd ed. Springer; New York: 2006. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G., Widom J. Nucleosomes facilitate their own invasion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:763–769. doi: 10.1038/nsmb801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gansen A., Valeri A., Seidel C.A. Nucleosome disassembly intermediates characterized by single-molecule FRET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15308–15313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee D.Y., Hayes J.J., Wolffe A.P. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell. 1993;72:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90051-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertin A., Renouard M., Durand D. H3 and H4 histone tails play a central role in the interactions of recombinant NCPs. Biophys. J. 2007;92:2633–2645. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reference deleted in proof.

- 25.Neumann H., Peak-Chew S.Y., Chin J.W. Genetically encoding N(epsilon)-acetyllysine in recombinant proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:232–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handwerger K.E., Cordero J.A., Gall J.G. Cajal bodies, nucleoli, and speckles in the Xenopus oocyte nucleus have a low-density, sponge-like structure. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:202–211. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyagi A., Ando T., Lyubchenko Y.L. Dynamics of nucleosomes assessed with time-lapse high-speed atomic force microscopy. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7901–7908. doi: 10.1021/bi200946z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voltz K., Trylska J., Langowski J. Unwrapping of nucleosomal DNA ends: a multiscale molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 2012;102:849–858. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang C., van der Woerd M.J., Luger K. Biophysical analysis and small-angle X-ray scattering-derived structures of MeCP2-nucleosome complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4122–4135. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Böhm V., Hieb A.R., Langowski J. Nucleosome accessibility governed by the dimer/tetramer interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3093–3102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montezinho L.P., Fonseca C.P., Castro M.M. Quantification and localization of intracellular free mg in bovine chromaffin cells. Met. Based Drugs. 2002;9:69–80. doi: 10.1155/MBD.2002.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon F., Luger K., Hansen J.C. The core histone N-terminal tail domains function independently and additively during salt-dependent oligomerization of nucleosomal arrays. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33701–33706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischle W., Wang Y., Allis C.D. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stühmeier F., Welch J.B., Clegg R.M. Global structure of three-way DNA junctions with and without additional unpaired bases: a fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13530–13538. doi: 10.1021/bi9702445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jimenez-Useche I., Yuan C. The effect of DNA CpG methylation on the dynamic conformation of a nucleosome. Biophys. J. 2012;103:2502–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haas E., Katchalski-Katzir E., Steinberg I.Z. Effect of the orientation of donor and acceptor on the probability of energy transfer involving electronic transitions of mixed polarization. Biochemistry. 1978;17:5064–5070. doi: 10.1021/bi00616a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edelman L.M., Cheong R., Kahn J.D. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer over approximately 130 basepairs in hyperstable lac repressor-DNA loops. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1131–1145. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74929-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.You Y., Tataurov A.V., Owczarzy R. Measuring thermodynamic details of DNA hybridization using fluorescence. Biopolymers. 2011;95:472–486. doi: 10.1002/bip.21615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.