Abstract

Background

Malignant brain tumors in children generally have a very poor prognosis when they relapse and improvements are required in their management. It can be difficult to accurately diagnose abnormalities detected during tumor surveillance, and new techniques are required to aid this process. This study investigates how metabolite profiles measured noninvasively by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) at relapse reflect those at diagnosis and may be used in this monitoring process.

Methods

Single-voxel MRS (1.5 T, point-resolved spectroscopy, echo time 30 ms, repetition time 1500 ms was performed on 19 children with grades II–IV brain tumors during routine MRI scans prior to treatment for a suspected brain tumor and at suspected first relapse. MRS was analyzed using TARQUIN software to provide metabolite concentrations. Paired Student's t-tests were performed between metabolite profiles at diagnosis and at first relapse.

Results

There was no significant difference (P > .05) in the level of any metabolite, lipid, or macromolecule from tumors prior to treatment and at first relapse. This was true for the whole group (n = 19), those with a local relapse (n = 12), and those with a distant relapse (n = 7). Lipids at 1.3 ppm were close to significance when comparing the level at diagnosis with that at distant first relapse (P = .07, 6.5 vs 12.9). In 5 cases the MRS indicative of tumor preceded a formal diagnosis of relapse.

Conclusions

Tumor metabolite profiles, measured by MRS, do not change greatly from diagnosis to first relapse, and this can aid the confirmation of the presence of tumor.

Keywords: brain tumors, diagnosis, MR spectroscopy, pediatrics, relapse.

Brain tumors are the most common solid tumors in children and account for ∼20% of all childhood cancers. While some brain tumors have a very good prognosis, others continue to present major challenges, and brain tumors are now the leading cause of death from cancer in children.1 Children who relapse following treatment of a malignant brain tumor commonly have a very poor prognosis. Diagnosis of relapse is commonly made using the clinical course and changes on imaging without a biopsy. However, it is well documented that changes can occur on an MRI as a result of treatment and may not represent tumor recurrence or progression, and a more accurate noninvasive diagnosis of relapse would enhance clinical management.2–6

The Macdonald criteria, which are based on an increase in size of an enhancing tumor on consecutive MRI scans together with clinical assessment, have been used to determine tumor recurrence.7 However, not all tumors enhance, and changes in enhancement can result from treatment effects, in particular from radiotherapy. These treatment-related changes are often referred to as pseudoprogression and are due to secondary edema and vessel permeability changes.8,9 Further challenges have arisen with the introduction of new therapeutic agents that alter the permeability of the blood–brain barrier and demonstrate a dramatic improvement in enhancement rather than a true tumor response or “pseudo-response.”10 The recognition of pseudoprogression, particularly in adults with high-grade glioma, led to the agreement of the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria, which have also been extended to low-grade gliomas in adults.2,3 The RANO criteria provide an improved assessment of disease progression and treatment response by addressing the limitations of the Macdonald criteria. However, they are still restricted in their ability to diagnose relapse accurately; there are currently no similar guidelines for diagnosing relapse specific to children, and the need for these has been identified.6

1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is a noninvasive, in vivo method for determining metabolite profiles of tissue.11 Studies of MRS in adults have investigated the method for diagnosis and evaluation of tumor recurrence.12–15 Brain tumors in children have a different spectrum of disease than those in adults, and even where the tumors are of the same histological type, there is evidence that the tumors differ between children and adults.16 In particular, there are a large and diverse number of tumor types seen in children, and this is reflected by the diversity of MRS metabolite profiles seen in the tumors.17–20 Combining MRS with a quantitative analysis of metabolite profiles can exploit these differences to provide accurate classification of common childhood brain tumor types.18,21 Potentially, MRS could be used to aid the identification of tumor at suspected relapse; however, the diversity of metabolite profiles seen across tumor types ensures that simple rules based on single metabolites or ratios of metabolites are unlikely to be successful in identifying relapsed tumor in all children.17 One approach would be to use the metabolite profile of the tumor at diagnosis to inform the interpretation of MRS during surveillance, but it is unknown how the metabolite profiles of brain tumors in children differ between diagnosis and relapse. Since it is known that alterations in the biology of tumor cells can occur between diagnosis and relapse—for example, chromosomal changes accumulate in ependymomas22—large changes in MRS profile could potentially occur, and this possibility needs to be investigated.

The main purpose of this study was to determine whether large changes occur in metabolite profiles of malignant childhood brain tumors from diagnosis to relapse and if so to identify these. A secondary aim was to confirm that significant differences do exist between MRS of tumors at diagnosis and nontumor lesions observed in the same patients at follow-up. We explored the potential of MRS to aid relapse confirmation when it was added to conventional MRI and clinical course.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This is a retrospective analysis from a study in which single-voxel MRS was performed on children between July 2003 and July 2011 during routine MRI for a suspected brain tumor prior to treatment and at subsequent MRI where a lesion was identified. The enrollment criteria for this study included all children with a histologically diagnosed brain tumor of grades II–IV that demonstrated progression or relapse and had good-quality MRS. Diffuse pontine gliomas were excluded due to the known difficulties of identifying progression on conventional MRI23 and the previously reported evolution of MRS with subsequent disease progression.24 Nineteen patients were identified (Table 1). The cohort consisted of patients (mean age 7 y) with 7 different tumor types, including 4 glioblastoma multiforme (4 males, mean age 11 y), 4 medulloblastomas (3 males, 1 female, mean age 5.6 y), 4 diffuse astrocytomas (4 males, mean age 8.6 y), 3 ependymomas (1 of which was anaplastic; 2 males, 1 female, mean age 1.8 y), 2 CNS primitive neuroectodermal tumors (2 males, mean age 5.6 y), 1 atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (1 male, age 0.1 y), and 1 gliomatosis cereberi (1 male, age 16.3 y), giving a total of 15 male and 4 female patients.

Table 1.

A summary of clinical data from a cohort of 19 cases included in the MRS study

| No. | Sex | Diagnosis | Treatment (prior to relapse) | Surgery at Diagnosis | Relapse Site | Surgery at Relapse | Status | No. of Days Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Glioblastoma | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | SR | Distant | None | D | 676 |

| 2 | M | Glioblastoma | Chemotherapy | GTR | Local | None | D | 194 |

| 3 | M | Glioblastoma | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | SR | Local | None | D | 282 |

| 4 | M | Glioblastoma | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | SR | Local | None | D | 483 |

| 5 | M | Ependymoma | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | GTR | Local | SR | D | 935 |

| 6 | F | Ependymoma | Focal radiotherapy | SR | Local | 4 surgeries SR | D | 1074 |

| 7 | F | Anaplastic ependymoma | Chemotherapy | SR | Local | None | D | 576 |

| 8 | M | Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor | Chemotherapy | SR | Local | None | D | 213 |

| 9 | F | Medulloblastoma | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | SR | Local | None | D | 1245 |

| 10 | M | Medulloblastoma | Craniospinal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | SR | Distant | None | D | 816 |

| 11 | M | Medulloblastoma | Chemotherapy | GTR | Distant | None | D | 539 |

| 12 | F | Large cell anaplastic medulloblastoma | Craniospinal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | GTR | Local | None | D | 764 |

| 13 | M | CNS primitive neuroectodermal tumor | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | SR | Distant | SR | D | 465 |

| 14 | M | Supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor | Chemotherapy | Biopsy | Distant | None | D | 596 |

| 15 | M | Diffuse astrocytoma | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Biopsy | Local | None | D | 571 |

| 16 | M | Diffuse astrocytoma | Chemotherapy | SR | Local | None | A | 2268 |

| 17 | M | Diffuse astrocytoma | Focal radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Biopsy | Distant | None | D | 756 |

| 18 | M | Diffuse astrocytoma | Chemotherapy | SR | Local | None | D | 170 |

| 19 | M | Gliomatosis cerebri | Radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Biopsy | Distant | None | D | 227 |

Abbreviations: GTR, gross total resection; SR, subtotal resection; D, died; A, alive.

Following MRI at presentation, all patients underwent surgery. Following surgery, an MRI scan was performed within 1 to 3 days, and formal radiological reporting together with review in a multidisciplinary team meeting was used to determine the extent of tumor excision (gross total or subtotal resection). Four patients had a gross total resection by surgical opinion and postoperative MRI; 11 had a subtotal resection; and 4 had a biopsy for diagnosis alone. All children underwent adjuvant treatment with either focal or craniospinal radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy depending on their tumor type and prognostic stratification (Table 1).

Assessment of Disease Progression

Disease progression confirmation in the cohort was taken as the decision made by the neuro-oncology multidisciplinary team from a combination of clinical and radiological features. The criteria were (i) diagnosis of progression if there was an increase in the size of the tumor of more than 25% measured in 2 dimensions on MRI scan and (ii) the appearance of tumor in a previously uninvolved area or clear clinical evidence of disease progression in combination with an equivocal MRI. Follow-up scans were then performed every 1–3 months depending on case scenario to determine patient status. MRS was performed if a lesion, either local or distant to the tumor identified at diagnosis, was large enough for single-voxel MRS. During suspected tumor relapse, MRS processed by the scanner was made available to the clinical multidisciplinary team and qualitatively analyzed by them, but a quantitative comparison with the diagnostic MRS was not made available. If the consensus decision was that the patient demonstrated tumor relapse, optimal treatment strategies were discussed. Neurosurgery at relapse was performed only if it was felt to be beneficial to the patient taking account of outcome and quality of life. Only 3 cases had surgical intervention at first relapse for comparison with histopathological diagnosis at presentation. In all cases the histology was in keeping with that at diagnosis. At the end of the study, 18 patients had died of disease progression and 1 patient was alive with stable disease. The mean time from diagnosis to relapse was 15 months, and mean time from diagnosis to death was 19 months.

MRS Acquisition and Quantitation of Metabolite Concentrations and Lipid Intensities

MRS was carried out on a 1.5 T MR scanner (GE Excite, Siemens Symphony, or Siemens Avanto) after conventional MRI, which included T1-weighted, T2-weighted. and T1-weighted postcontrast sequences. A single-voxel MRS protocol was used with point-resolved spectroscopy localization, a short echo time of 30 ms, and a repetition time of 1500 ms. A water unsuppressed acquisition was also acquired as a concentration reference. Cubic voxels were used with either 2 cm or 1.5 cm side length, and 128 or 256 repetitions were acquired, respectively. Voxel placement was entirely within the tumor as delineated by the conventional MRI with the enhancing component maximized. Local relapses were at the site of the primary tumor, while distant relapses were taken to be at any other location.

Raw spectroscopy data were processed using TARQUIN (Totally Automatic Robust Quantitation in NMR) v3.2.2 with a basis set including 18 different metabolites and 9 lipid and macromolecular components (Table 2).25 The lipid and macromolecular components were included in the analysis as individual components and as combined components at 0.9 ppm, 1.3 ppm, and 2.0 ppm. For cases to be included in the analysis, conventional MRI and voxel location were required both prediagnosis and at relapse. Accurate voxel positioning was confirmed by imaging from 3 planes and checked to confirm that placement was >3 mm away from bone, scalp, and air and was not dominated by normal brain. Cases were also required to have TARQUIN values for full-width half-maximum <0.150 ppm and a signal-to-noise ratio >5, and a measure of fit quality (Q) was also determined for each spectrum accepting those with a Q fit of <2.5. Spectra were also inspected visually for baseline abnormalities and major artifacts. In addition to the 19 cases included, 1 case was excluded due to unstable baseline on the relapse MRS.

Table 2.

Estimated metabolite concentrationsa

| Mean Metabolite Concentrations (mM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite | P | Diagnosis vs Relapse at Any Location | Diagnosis vs Local Relapse | Diagnosis vs Distant Relapse |

| Ala | n.s | 0.27 vs 0.37 | 0.32 vs 0.48 | 0.20 vs 0.18 |

| Cit | n.s | 0.64 vs 1.10 | 0.79 vs 1.32 | 0.39 vs 0.71 |

| Cr | n.s | 2.73 vs 3.14 | 2.53 vs 2.66 | 3.08 vs 3.96 |

| PCh + GPC | n.s | 1.98 vs 1.99 | 1.78 vs 1.73 | 2.31 vs 2.45 |

| GPC | n.s | 1.25 vs 1.24 | 1.16 vs1.19 | 1.39 vs 1.34 |

| PCh | n.s | 0.73 vs 0.75 | 0.62 vs 0.54 | 0.92 vs 1.11 |

| Glc | n.s | 1.82 vs 1.31 | 1.74 vs 1.28 | 1.97 vs 1.35 |

| Gln | n.s | 3.19 vs 3.02 | 3.88 vs 3.21 | 2.01 vs 2.72 |

| Glu | n.s | 2.16 vs 2.84 | 2.22 vs 2.42 | 2.01 vs 3.57 |

| Glu + Gln | n.s | 5.35 vs5.87 | 6.10 vs 5.62 | 4.06 vs 6.29 |

| Gly | n.s | 2.20 vs 2.11 | 2.42 vs 2.33 | 1.83 vs 1.74 |

| Gua | n.s | 0.61 vs 0.68 | 0.62 vs 0.70 | 0.59 vs 0.65 |

| Ins | n.s | 2.81 vs3.01 | 2.75 vs 3.87 | 2.90 vs 1.54 |

| Lac | n.s | 2.16 vs1.67 | 2.62 vs 2.35 | 1.37 vs 0.51 |

| Scyllo | n.s | 0.30vs 0.35 | 0.31vs 0.36 | 0.28 vs 0.32 |

| Tau | n.s | 1.02 vs 0.94 | 0.55 vs 0.74 | 1.83 vs 1.28 |

| NAA+NAAG | n.s | 1.27 vs 1.54 | 1.15 vs 1.25 | 1.48 vs 2.03 |

| MMLip0.9 | n.s | 6.61 vs7.95 | 7.30 vs 8.90 | 5.43 vs 6.33 |

| Lip 0.9 | n.s | 3.32 vs 3.78 | 4.01 vs 3.98 | 2.13 vs 3.44 |

| MM 0.9 | n.s | 3.29 vs 4.17 | 3.29 vs 4.91 | 3.30 vs 2.90 |

| MMLip 1.3 | n.s | 15.32 vs 19.13 | 19.83 vs 22.69 | 7.60 vs 13.52 |

| Lip 1.3 | n.s | 13.32 vs16.44 | 17.30 vs 18.52 | 6.50 vs 12.87 |

| MM 1.3 | n.s | 2.00 vs 2.88 | 2.53 vs 4.17 | 1.01 vs 0.65 |

| MMLip2.0 | n.s | 10.30 vs 9.66 | 11.28 vs 9.44 | 8.63 vs 10.05 |

| Lip 2.0 | n.s | 3.70 vs 3.07 | 4.48 vs 2.94 | 2.36 vs 3.28 |

| MM 2.0 | n.s | 6.61 vs 3.36 | 6.80 vs 6.49 | 6.27 vs 6.77 |

Abbreviations: Ala, alanine; Cit, citrate; GPC, glycerophosphocholine; Glc, glucose; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; Glu + Gln, glutamate + glutamine (Glx); Gly, glycine; Gua, guanidinoacetate; Ins, myo-inositol; Lac, lactate; Scyllo, scyllo-inositol; Lip 0.9, lipids at 0.9 ppm; Lip 1.3, lipids at 1.3 ppm (a + b); Lip 2.0, lipids at 2.0 ppm; MMLip0.9, lipids + macromoleules at 0.9 ppm; MM 0.9, macromolecules at 0.9 ppm; MMLip1.3, lipids + macromoleules at 1.3 ppm; MM 1.3, macromolecules at 1.3 ppm; MMLip2.0, lipids + macromoleules at 2.0 ppm; MM 2.0, macromolecules at 2.0 ppm; NAA + NAAG, N-acetyl aspartate (NAA); PCh + GPC, total choline; PCh , phosphocholine; Tau, taurine; n.s, not significant.

aDiagnosis vs relapse (n = 19), diagnosis vs local relapse (n = 12), diagnosis vs distant relapse (n = 7), showing no significant differences among any of the 3 groups using a 2-tailed Student's t-test.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed with R Statistical Software v2.13.1 on the metabolite concentrations (mM) quantified using TARQUIN.25,26 A power analysis calculation showed that the 19 samples would detect a large effect size (Cohen d = 0.68) for a 2-tailed paired t-test at a significance level of 0.05 with a power of 0.8. TARQUIN provides an indication of the uncertainty in the fit for each metabolite by Cramér-Rao lower bounds. Statistical analysis excluded the metabolites aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid due to their consistently high Cramér-Rao lower bound levels. Paired Student's t-tests were performed to investigate differences between metabolite profiles at diagnosis and relapse. The comparison was also performed separately for local and distant relapse. Box and whisker plots were constructed for differences between absolute concentrations of variables at diagnosis and relapse. Line plots were constructed to visualize differences among levels of 4 main variables (total choline, myo-inositol, n-acetyl aspartate, and lipids at 1.3 ppm) at diagnosis and relapse. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for the paired analysis of metabolites in nontumor lesions at follow-up and tumors at diagnosis due to the smaller numbers of cases and lack of information on the Gaussian nature of the distribution.

Results

No significant differences in metabolites or lipid and macromolecules were found between diagnosis and relapse (n = 19; P > .05, paired Student's t-test). Subgroup analyses of local relapse (n = 12) and distant relapse (n = 7) also demonstrated no significant differences in metabolites or combined and individual macromolecules and lipid components in either of these 2 groups (P > .05, paired Student's t-test). However, lipids at 1.3 ppm were close to significance (6.5 vs 12.9, P = .07) in the group where MRS was of a distant relapse (Table 2). In addition, no significant differences (P > .05, Student's t-test) were found when comparing MRS at diagnosis and relapse in specific tumor types. The tumor types tested were those brain tumors that had 4 or more cases per tumor type: glioblastomas (n = 4), medulloblastomas (n = 4), and diffuse astrocytomas (n = 4).

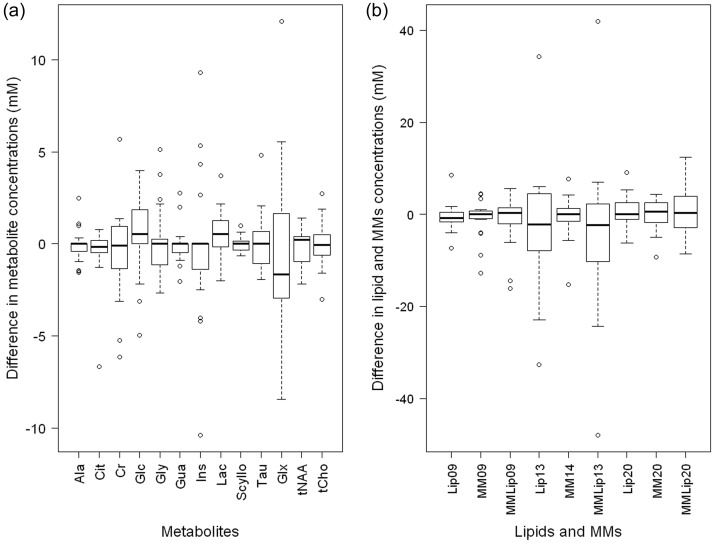

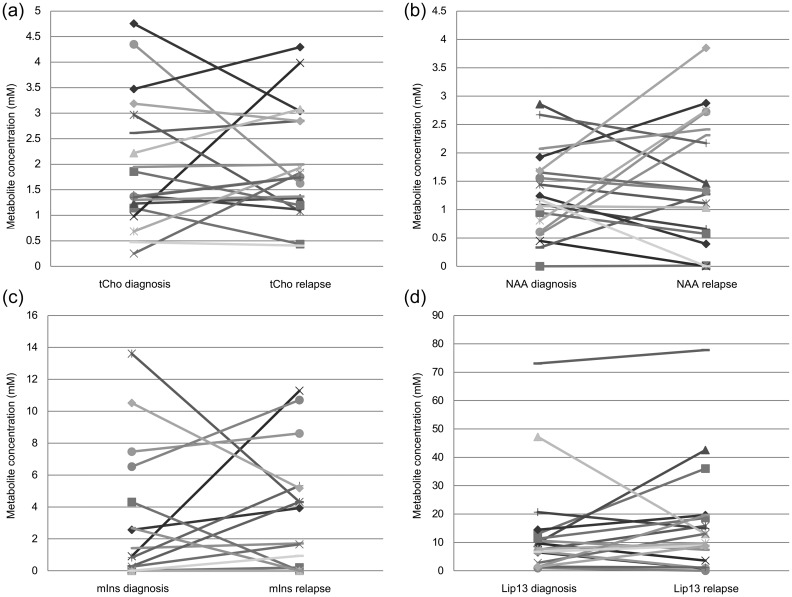

Differences in metabolite, lipid, and macromolecule levels at diagnosis and relapse are demonstrated in Fig. 1 as a box and whisker plot. Although there are some metabolites that change by a large amount from diagnosis to first relapse, there are no tumors for which this occurs for several metabolites, lipids, or macromolecules, indicating that for all tumors, the majority of the MRS profile is the same at relapse as at diagnosis. Figure 2 shows changes in metabolite concentrations from diagnosis to relapse for 4 main variables: total choline, n-acetyl aspartate, myo-inositol, and lipids at 1.3 ppm. Again, for most cases there is little change in the levels of these metabolites between diagnosis and relapse. However, for a small number of cases, there is a large change in a specific metabolite.

Fig. 1.

Box and whisker plots demonstrating differences between diagnosis and relapse in (a) metabolite concentrations and (b) lipid and macromolecular (MM) concentrations (n = 19).

Fig. 2.

Changes in metabolite concentrations at diagnosis and relapse for individual cases: (a) total choline (tCho), (b) n-acetyl aspartate (NAA), (c) myo-inositol (mIns), and (d) lipids at 1.3 ppm.

For 5 of the cases, MRS indicated the presence of tumor prior to a diagnosis of relapse being made by the multidisciplinary team using clinical information, conventional MRI, and histology where available. The median time from MRS indicating the presence of tumor to diagnosis of relapse was 3 months in these 5 cases. Four of the cases were astrocytomas and 1 was an ependymoma.

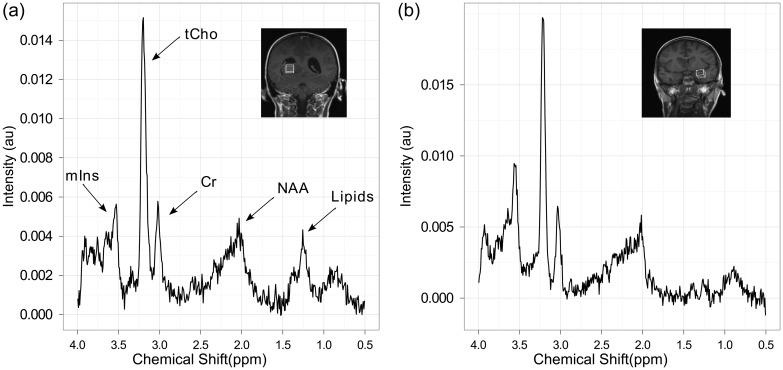

Figure 3 demonstrates the similarity of MRS at diagnosis and distant relapse in a patient with glioblastoma multiforme who had 2 surgical resections followed by radiotherapy. Tumor progression was seen at 536 days, and an additional MRI was performed following radiologically confirmed progression at 654 days at 2 different distant tumor sites.

Fig. 3.

Comparison showing the similarity of MRS at diagnosis and distant first relapse (case 1). (a) MRS of the brain tumor prediagnosis with a coronal T1-weighted image showing the voxel location and (b) MRS obtained from the same tumor at relapse from a distant site with the T1-weighted imaging showing the voxel location. Abbreviations: mIns, myo-inositol; tCho, total choline; Cr, creatine; NAA, n-acetyl aspartate.

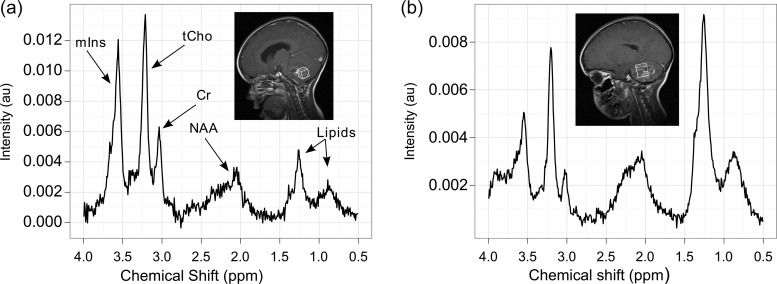

Figure 4 demonstrates spectra from a patient with multiply relapsed ependymoma. After diagnosis, the patient underwent surgical resection followed by focal radiotherapy but later developed local tumor progression. This patient had 4 surgical resections: 2 at diagnosis, 1 at first relapse, and another at a subsequent relapse. Diagnosis at initial presentation was grade 2 ependymoma, but at first and second relapse the tissue samples were increasingly cellular and demonstrated an increasing proliferative rate. The final sample was suggestive of an anaplastic ependymoma (grade III). Spectroscopy was performed at each relapse with the last 908 days after diagnosis. The spectra demonstrate high levels of myo-inositol and low levels of lipids at first relapse, in keeping with MRS at diagnosis (Fig. 4A), but a decline in myo-inositol and an increase in lipids on the last spectrum (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Evolution of MRS from diagnosis to third relapse (case 6). (a) MRS of an ependymoma prediagnosis with a sagittal T1-weighted postcontrast image showing the voxel location; (b) MRS obtained after a subsequently confirmed relapse with a sagittal T1-weighted postcontrast image showing the voxel location. Abbreviations: mIns, myo-inositol; tCho, total choline; Cr, creatine; NAA, n-acetyl aspartate.

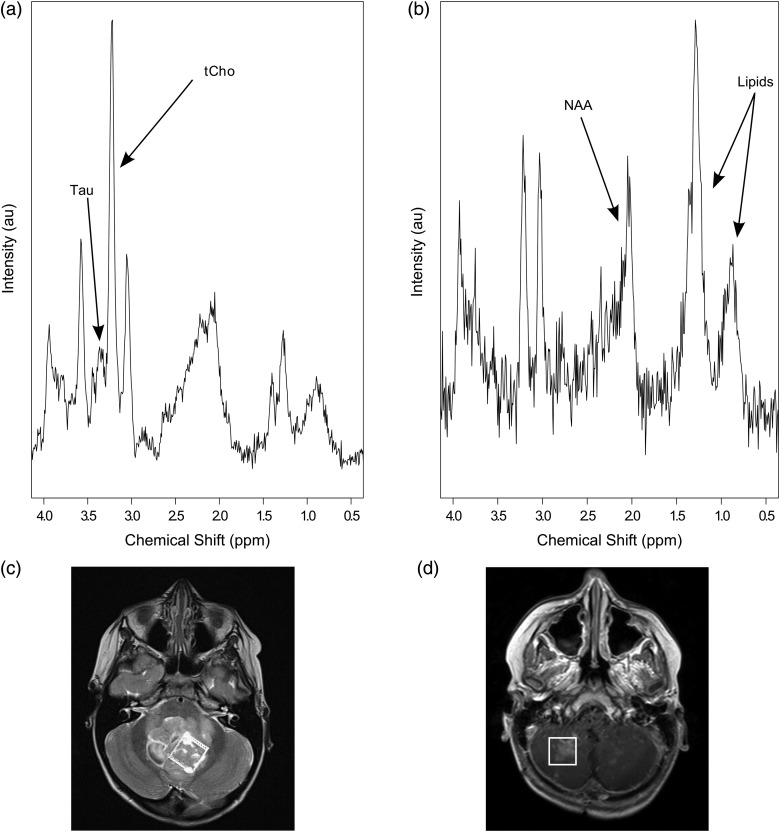

In addition to the cases where relapse occurred, a further 5 cases had MRS at diagnosis, and of a lesion that appeared posttreatment, where extended follow-up confirmed that the lesion was not relapsed tumor. The MRS in all these cases was very different on visual inspection from the MRS at diagnosis. An example is presented in Fig. 5. Analysis of 9 MRS scans during surveillance paired with the MRS scans at initial diagnosis showed significantly higher total choline, glycine, lactate, and taurine at initial diagnosis (P < .05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test ).

Fig. 5.

MRS at diagnosis and pseudoprogression from a patient with classic medulloblastoma. (a) Prediagnostic brain tumour MRS showing elevated total choline (tCho) and taurine (Tau); (b) MRS obtained from the same tumour after completion of treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (the spectrum demonstrates raised lipids, low N-acetyl aspartate [NAA], no detectable Tau and tCho is not raised); (c) T2-weighted axial image showing location of voxel corresponding to spectrum in (a); (d) T1-weighted postcontrast axial image showing an enhancing lesion in the posterior fossa with the position of the voxel indicated, which corresponds to spectrum (b).

Discussion

This study investigated metabolite profiles of childhood brain tumors at diagnosis and suspected first relapse at either local and/or distant sites using short echo time MRS and found no significant differences in any metabolite, lipid, or macromolecular level on a paired Student's t-test. In 5 cases there was diagnostic uncertainty based on the clinical and conventional MRI appearances, with relapse being confirmed only 1 to 6 months later. MRS profiles of brain tumors recorded at diagnosis therefore have the potential to aid the diagnosis of relapse.

In adults with gliomas, simple ratio's of metabolites such as total choline/creatine or total choline/n-acetyl aspartate are used to identify tumor.27 However, pediatric neuro-oncology practice is not dominated by a single tumor type, and a number of studies characterizing metabolite profiles of pediatric brain tumors have identified key differences depending on the diagnostic subtype.17,18,20 This study implies that for pediatric brain tumors, MRS at diagnosis would be a useful aid in identifying tumors on follow-up scans. In any given case, a small number of metabolite values may change substantially from diagnosis to relapse, but the overall pattern of metabolite levels tends to be very similar.

While this study shows that metabolite profiles are similar at first relapse to diagnosis, there are some indications that alterations toward a more aggressive metabolite phenotype can occur in some circumstances. It might be expected that the greatest changes are seen in the distant relapses, and there is a tendency toward higher lipids in these cases, although this is not significant (P = .07). The tendency for the MRS changes to be small from diagnosis to relapse even when the relapse is at a distant site is demonstrated by case 1, which had both a local and a distant relapse (Fig. 3). It may be expected that changes in tumor metabolite profiles accumulate over time, and there is evidence for this in case 6 (Fig. 4), which had subsequent relapses and showed evolving changes in the MRS profiles mirroring changes in histology. The decreasing myo-inositol and increasing lipids at subsequent relapses are consistent with this evolution of grade. MRS scans of grade II ependymoma tend to have a prominent myo-inositol peak seen at 3.6 ppm, in keeping with studies of adults with gliomas, where there are trends toward lower levels of myo-inositol at higher grade (Fig. 4).28 In addition, a number of previous studies have investigated the levels of lipids in pediatric brain tumors, found mobile lipids to correlate with malignancy across a range of pediatric brain tumors, and associated them with necrosis, which is a histological characteristic of high-grade tumors.29,30 Similar changes in MRS are likely to occur in tumors that are known to change from low to high grade as the disease progresses, and this is consistent with findings for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma.24

While this study has established that the MRS scans of relapsed children's brain tumors are very similar to those at diagnosis, the degree of certainty with which MRS can be used to diagnose relapse also depends on the MRS characteristics of other lesions in the brain occurring in these patients. It is therefore reassuring that significant differences were seen in several metabolites between the MRS of tumors at diagnosis and nontumor lesions observed in the same patients at follow-up. Caution does need to be taken when interpreting the spectra in these circumstances—in particular, it is important to ensure that the voxel does not contain significant amounts of normal brain and that the spectra meet the quality control criteria.

It is encouraging that MRS was able to detect recurrent tumor in several cases where the clinical scenario and conventional MRI were not able to diagnose relapse with confidence. MRS was made available to the multidisciplinary team as part of their clinical information during the study, and it may be that there were cases where MRS aided the diagnosis of relapse, although data were not collected systematically on this. It is interesting that none of the cases where MRS indicated the presence of tumor early were medulloblastomas or other primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Certainly, diagnostic dilemmas following treatment have been best documented in gliomas, and it may be that posttreatment abnormalities that mimic tumor on conventional MRI are rarer in primitive neuroectodermal tumors, although this may change with increasing intensity of treatment in those with high-risk disease. Analysis of MRS that includes the comparison of MRS at follow-up with that at diagnosis is now routinely used to inform clinical decision making in our center, in combination with clinical information and conventional MRI. The role of modalities such as perfusion imaging also warrants investigation, although this technique is not as well established in children as it is in adults. The optimum combination of imaging techniques has yet to be formally established.

Conclusion

This study found that the MRS metabolite profile of a child's brain tumor (grades II–IV) was not significantly different at first relapse from that at diagnosis, therefore aiding the confirmation of the presence of tumor on follow-up MRI. This finding is particularly relevant to the clinical management of these children given that radiotherapy and chemotherapy are known to cause abnormalities on MRI that are difficult to distinguish from recurrent tumor. A large multicenter study should be undertaken to clearly define the role of MRS in distinguishing tumor relapse from treatment-related effects and its added value compared with conventional MRI and other imaging modalities.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This work was funded by CR-UK & EPSRC Cancer Imaging Programme at the CCLG, in association with the MRC and Department of Health (England) C7809/A10342; the NIHR 3T MRI Centre; and an NIHR Professorship.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of the Birmingham Children's Hospital Radiology Department, in particular Shaheen Lateef and Rachel Grazier. We would like to thank Dr Heather Crosby for the work that she put into the initial data collection and analysis.

References

- 1.Childhood Cancer Research Group (CCRG) National Registry of Childhood Tumours/Childhood Cancer Research Group. http://www.ccrg.ox.ac.uk/ Accessed 30 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: Response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1963–1972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Bent MJ, Wefel JS, Schiff D, et al. Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (a report of the RANO group): assessment of outcome in trials of diffuse low-grade gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):583–593. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta AI, Kanaly CW, Friedman AH, Bigner DD, Sampson JH. Monitoring radiographic brain tumor progression. Toxins. 2011;3(3):191–200. doi: 10.3390/toxins3030191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quant E, Wen P. Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13(1):50–56. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0143-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren KE, Poussaint TY, Gilbert Vezina G, et al. Challenges with defining response to antitumor agents in pediatric neuro-oncology: a report from the Response Assessment in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology (RAPNO) working group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(9):1397–1401. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24562. 9 doi:10.1002/pbc.24562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macdonald DR, Cascino T, Schold SJ, et al. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1277–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, et al. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant glioma. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:453–456. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu LS, Baxter LC, Smith KA, et al. Relative cerebral blood volume values to differentiate high-grade glioma recurrence from post treatment radiation effect: direct correlation between image-guided tissue histopathology and localized dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging measurements. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(3):552–558. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG, di Tomaso E, et al. AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peet AC, Arvanitis TN, Leach MO, Waldman AD. Functional imaging in adult and paediatric brain tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(12):700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tate AR, Underwood J, Acosta DM, et al. Development of a decision support system for diagnosis and grading of brain tumours using in vivo magnetic resonance single voxel spectra. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(4):411–434. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Gómez JM, et al. Multiproject-multicentre evaluation of automatic brain tumour classification by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. MAGMA. 2009;22:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0146-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julià-Sapé M, Coronel I, Majós C, et al. Prospective diagnostic performance evaluation of single-voxel 1H MRS for typing and grading of brain tumours. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(4):661–673. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith EA, Carlos RC, Junck LR, Tsien CI, Elias A, Sundgren PC. Developing a clinical decision model: MR spectroscopy to differentiate between recurrent tumor and radiation change in patients with new contrast-enhancing lesions. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(2):W45–W52. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones D, Mulholland S, Pearson D, et al. Adult grade II diffuse astrocytomas are genetically distinct from and more aggressive than their paediatric counterparts. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;121(6):753–761. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0810-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panigrahy A, Krieger M, Gonzalez-Gomez I, et al. Quantitative short echo time 1H-MR spectroscopy of untreated pediatric brain tumors: preoperative diagnosis and characterization. Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(3):560–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies NP, Wilson M, Harris LM, et al. Identification and characterisation of childhood cerebellar tumours by in vivo proton MRS. NMR Biomed. 2008;21(8):908–918. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris LM, Davies NP, MacPherson L, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the assessment of pilocytic astrocytomas. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(17):2640–2647. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orphanidou-Vlachou E, Auer D, Brundler MA, et al. 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the diagnosis of paediatric low grade brain tumours. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(6):e295–e301. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vicente J, Fuster-Garcia E, Tortajada S, et al. Accurate classification of childhood brain tumours by in vivo 1H MRS—a multi-centre study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(3):658–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puget S, Grill J, Valent A, Bieche I. Candidate genes on chromosome 9q33–34 involved in the progression of childhood ependymomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1884–1892. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hargrave D, Chuang N, Bouffet E. Conventional MRI cannot predict survival in childhood diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J Neuro-Oncol. 2008;86(3):313–319. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panigrahy A, Nelson M, Nelson J, et al. Metabolism of diffuse intrinsic brainstem gliomas in children. Neuro-oncology. 2008;10(1):32–44. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson M, Reynolds G, Kauppinen RA, Arvanitis TN, Peet AC. A constrained least-squares approach to the automated quantitation of in-vivo 1H MRS data. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(1):1–12. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKnight TR, Lamborn KR, Love TD, et al. Correlation of magnetic resonance spectroscopic and growth characteristics within grades II and III gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(4):660–666. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castillo M, Smith JK, Kwock L, et al. Correlation of myo-inositol levels and grading of cerebral astrocytomas. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(9):1645–1649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astrakas LG, Zurakowski D, Tzika AA, et al. Noninvasive magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging biomarkers to predict the clinical grade of pediatric brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(24):8220–8228. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson M, Cummins CL, MacPherson L, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy metabolite profiles predict survival in paediatric brain tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(2):457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]