Abstract

Despite a remarkable regenerative capacity, recovery of the mammalian olfactory epithelium can fail in severely injured areas, which subsequently reconstitute as aneuronal respiratory epithelium (metaplasia). We contrasted the cellular response of areas of the rat epithelium that recover as olfactory after methyl bromide lesion with those undergoing respiratory metaplasia in order to identify stem cells that restore lesioned epithelium as olfactory. Ventral olfactory epithelium is at particular risk for metaplasia after lesion and patches of it are rendered acellular by methyl bromide exposure. In contrast, globose basal cells (GBCs, marked by staining with GBC-2) are preserved in surrounding ventral areas and uniformly throughout dorsal epithelium, which consistently and completely recovers as olfactory after lesion. Over the next few days, neurons reappear, but only in those areas in which GBCs are preserved and multiply. In contrast, parts of the epithelium in which GBCs are destroyed are repopulated in part by Bowman’s gland cells, which pile up above the basal lamina. Electron microscopy confirms the reciprocity between gland cells and globose basal cells. By 14 days after lesion, the areas that are undergoing metaplasia are repopulated by typical respiratory epithelial cells. As horizontal basal cells are eliminated from all parts of the ventral epithelium, the data suggest that GBC-2(+) cells are ultimately responsible for regenerating olfactory neuroepithelium. In contrast, GLA-13(+) cells may give rise to respiratory metaplastic epithelium where GBCs are eliminated. Thus, we support the idea that a subpopulation of GBCs is the neural stem cell of the olfactory epithelium.

Indexing terms: stem cells, neurogenesis, gland/duct cells, respiratory metaplasia, mutipotent progenitors, immunohistochemistry

The capacity for cellular reconstitution after lesion is a remarkable feature of the olfactory system. There have been various experimental lesion models to demonstrate that the olfactory epithelium recovers from the loss of its cellular constituents after damage. They include axotomy (Costanzo, 1991; Monti-Graziadei and Graziadei, 1979; Simmons et al., 1981), bulbectomy (Costanzo, 1984; Costanzo and Graziadei, 1983), and inhalation or injection of environmental agents, such as 3-methylindole (Peele et al., 1991), methyl methacrylate (Chan et al., 1988), zinc sulfate (Harding et al., 1978; Cancalon, 1982), Triton X-100 (Cancalon, 1983; Verhaagen et al., 1990), and methyl bromide (Hurtt et al., 1988; Hastings et al., 1991; Schwob et al., 1995). In particular, the inhalation of methyl bromide (MeBr), a selective olfactotoxic gas, has been shown to be a consistent and reliable means of destroying the olfactory epithelium. When chronically food-restricted rats are exposed, MeBr destroys more than 95% of the olfactory epithelium, including the olfactory neurons and sustentacular cells, leaving only basal cells (Schwob et al., 1995). Recovery from damage is quick (within 8 weeks postlesion), as cellular composition and immunohistochemical and biochemical characteristics return to normal or near-normal (Schwob et al., 1995).

Nonetheless, in models that evoke more extensive injury, including MeBr under some circumstances, recovery after lesion, especially the reconstitution of the olfactory receptor neurons, fails. Under these conditions, what was originally olfactory mucosa reconstitutes as respiratory epithelium, which is a form of metaplasia. Moreover, biopsy and autopsy studies of the human nasal mucosa also reveal extensive metaplasia of what was originally olfactory epithelium as a consequence of aging (Nakashima et al., 1984; Paik et al., 1992), viral upper respiratory infection (Douek et al., 1975), and other conditions associated with olfactory dysfunction. It is likely that pathophysiological conditions that damage the epithelium directly may lead to a failure to regenerate as olfactory.

The failure of regeneration may be due to either destruction of stem cell populations in the olfactory epithelium or disruption of yet uncharacterized signaling pathways that direct neurogenesis. Thus, analyzing the metaplasia that occurs after injury may give two significant insights. First, by examining cellular dynamics in both the successfully reconstituted area and the failed counterpart, candidates that serve as stem cells for the epithelium may become more apparent. Second, better understanding of the pathophysiological process underlying the olfactory loss in age-related diseases and other infectious diseases will likely emerge.

Of the six distinct morphological cell types of the olfactory epithelium, horizontal basal cells (HBCs), globose basal cells (GBCs), and Bowman’s duct cells have been suggested by various investigators as the stem cells of the epithelium (Matulionis, 1975; Graziadei and Monti Graziadei, 1979; Calof and Chikaraishi, 1989; Caggiano et al., 1994; Huard et al., 1998). Various anatomical and cell biological data indicate that among the population of GBCs are multipotent progenitors that are activated by destruction of both neurons and nonneuronal cells (Huard et al., 1998; Goldstein et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2001). The multipotent progenitors activated by MeBr lesion can give rise to all of the cell types of the olfactory epithelium, with the exception of duct/gland cells. Exactly how the fate of these multipotent GBCs is determined and regulated is still not clear. However, lineage tracing, tissue analysis, and transplantation methods suggest that the status of the various cell populations of the olfactory epithelium after lesion is one of the factors that “directs” the course of differentiation of GBCs (Huard et al., 1998; Goldstein et al., 1998).

These and other data on the in vivo and in vitro capacity for neurogenesis led us and others (Caggiano et al., 1994; Schwartz Levey et al., 1991; Calof and Chikaraishi, 1989; Mumm et al., 1996) to suggest that the neurogenic stem cell is also to be found within the population of GBCs, along with GBCs that function as transient amplifying cells and immediate neuronal precursors. Our ability to study the GBC population is hampered by a paucity of specific markers for them. While HBCs express cytokeratins 5 and 14, the EGF receptor and a carbohydrate moiety recognized by Griffonia lectin, a GBC-only marker does not exist. Nonetheless, a few markers have been generated in our laboratory that identify GBCs in normal and lesioned epithelium, although they are also expressed at diminishing levels in cells downstream of the GBC population (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996; Goldstein et al., 1997). Here, we describe the cell biological behavior of GBCs at various time points after MeBr lesion using a previously reported GBC antibody, GBC-2 (Goldstein et al., 1997), along with specific markers for other major cell types in the epithelium: GLA-13 for Bowman’s gland/duct cells (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996; Goldstein et al., 1997), SUS-4 for sustentacular cells (Goldstein et al., 1997; Huard et al., 1998), and the antineurotubulin antibody TuJ-1 for immature olfactory neurons (Pixley, 1992).

For purposes of the present study, we have modified the parameters of MeBr exposure such that parts of the anterior and ventral part of the olfactory epithelium are at substantial and consistent risk for reconstituting as respiratory. Immunostaining with cell-specific markers was used in order to correlate differences in cellular populations spared by lesion between dorsal olfactory epithelium, which uniformly and reliably recovers, vs. ventral epithelium, where patches will recover as olfactory and surrounding areas will consistently undergo respiratory metaplasia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and tissue preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY), 200–250 g when obtained, were food-restricted in order to maintain them at 75% of ad libitum body weight. Thus, rats weighed 225–275 g at the time of lesion. Our previous results showed that when food-restricted, exposure to MeBr gas destroys more than 95% of the olfactory epithelium and damages areas of ventral olfactory epithelium to such an extent that they reconstitute as respiratory epithelium (Schwob et al., 1995). The procedures for MeBr exposure and tissue preparation were described previously (Schwob et al., 1995), except that MeBr gas was delivered unilaterally. The left side of the nose was closed with glue and a single stitch set under halothane 1 day before MeBr exposure. The closed side was used as an internal control for the open, lesioned side. The day after naris closure, conscious animals were caged and exposed to MeBr gas (Matheson Gas Products, East Rutherford, NJ) at 330 ppm in purified air for 6 hours. The animals were kept on the same feeding schedule after lesion until being sacrificed. Animals to be used for tissue sections were sacrificed at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, or 14 days after lesion, and those to be used for whole mount were sacrificed at 1, 2, 5 days or 3 months after lesion. All rats were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, i.p., and injected i.v. with BrdU (Fisher Scientific, 90 mg/kg) 1 hour before sacrifice. The animals were perfused by PBS (pH 7) and fixed by perfusion with a solution of periodatelysine-paraformaldehyde (PLP) in phosphate buffer. The concentration of paraformaldehyde was either 1 or 2%, depending on the intended analysis. The olfactory tissue was decalcified in saturated, neutral EDTA, cryoprotected, and sectioned on a cryostat at 8 µm in the coronal plane. For whole-mount analysis, only the septum was stained. All animal protocols were approved by the Committee for Humane Use of Animals at the SUNY Health Science Center at Syracuse, where the animal material was prepared.

Antibody reagents

Primary antibodies used in this study were: goat antiserum against OMP (the gift of Dr. Frank Margolis; Monti Graziadei et al., 1977), mouse monoclonal against BrdU (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), mouse monoclonal TuJ-1 against neuron-specific β-tubulin (the gift of Dr. Anthony Frankfurter; Moody et al., 1987), and rabbit polyclonal Laminin Ab-1 against laminin (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA). The following antibodies were generated in our laboratory: the mouse monoclonal IgG termed SUS-4 (to label sustentacular cells; Goldstein and Schwob, 1996), the mouse monoclonal IgG termed GLA-13 (to label Bowman’s gland/duct cells; Huard et al., 1998), the mouse monoclonal IgM termed GBC-2 (to label GBCs; Goldstein, et al., 1997), and the mouse monoclonal IgG termed PAN-4 (our unpublished data shows that PAN-4 stains all cellular components of the olfactory and respiratory epithelium; see Results).

Immunohistochemistry

The procedure for immunohistochemistry with a single primary antibody is modified slightly from what was previously reported by our laboratory (Schwob et al., 1992). Briefly, all sections for single labeling were treated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 5 minutes, followed by washing with PBS for 5 minutes. For GBC-2, sections were pre-treated with 70, 95, 100, 95, 70% ethanol for 1 minute each before trypsin. After pretreatment, sections were blocked with either 2.25% fish gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS for GBC-2 or 4% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) with 10% normal serum in PBS for all the other antibodies. The blocking solutions also contained 0.1% Triton-X. All the primary antibodies for single labeling were diluted in appropriate blocking solutions and were incubated overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed in PBS with 0.05% Tween-20. Primary antibodies used in isolation were visualized using appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies and peroxidase-based ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlin-game, CA) followed by incubation with diaminobenzidine (DAB). To compare the staining pattern with a set of antibodies (e.g., GBC-2, SUS-4, and GLA-13, or TuJ-1 and GLA-13), single-labeling was done on the directly adjacent section or the one next removed. For whole-mount staining with anti-OMP or anti-BrdU antibodies, the times for incubations and washes were extended. For double-labeling with GBC-2 and anti-BrdU (Fig. 5), GBC-2 was first visualized with DAB, then the sections were steamed in 0.1 N sodium citrate buffer to facilitate labeling with anti-BrdU. After the staining with GBC-2 was photographed using a water immersion lens (Nikon), sections were blocked and incubated with anti-BrdU for 90 minutes at room temperature. After incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody and ABC reagents, BrdU was visualized using the Slate Gray substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). For double-labeling with anti-laminin and PAN-4, sections were trypsinized before blocking and incubated with both antibodies. Since anti-laminin and PAN-4 were generated in different species (rabbit and mouse, respectively), the staining of both antibodies was visualized with simultaneous incubation of FITC-conjugated antirabbit IgG and Texas Red-conjugated anti-mouse IgG without cross-reaction. Sections were then dipped in 0.0001% bis-benzamide (Hoechst 33258; Poly-sciences, Warrington, PA) to identify nuclei.

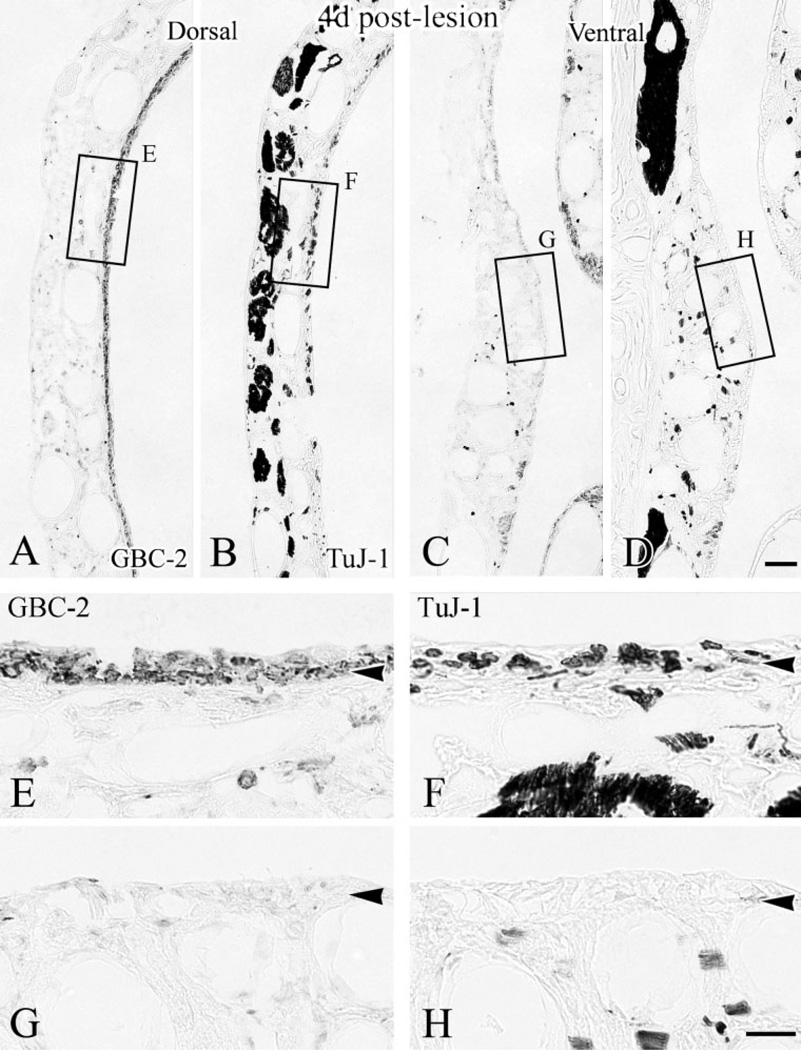

Fig. 5.

At 4 days after lesion, the neuronal population (labeled by TuJ-1 in B and D) has reemerged in dorsal epithelium but is only sporadically evident ventrally. Labeling with GBC-2 (in A,C) on adjacent sections shows that the immature neurons began to appear in dorsal epithelium (C) where GBCs are present (A), while ventral areas where GBCs are absent (B) are still devoid of neurons (D). Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification in E–H, respectively. Scale bar = 50 µm in D applies in A–C; 20 µm in H applies in E–G. Arrowheads indicate the basal lamina.

Preparation of images

OMP-stained whole-mount septa (Figs. 1, 2A–D) were photographed onto Ektachrome film using a Nikon photomicroscope and scanned into Adobe PhotoShop (Mountain View, CA). All other images were photographed using a digital SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Whole-mount staining with anti-BrdU antibody (Fig. 2A–D) were imaged at 4× magnification and assembled into a mosaic. Images were segmented for density and then highlighted using IPLab Spectrum image analysis software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA) to emphasize the location of the BrdU(+) cells. For analytic purposes, the “dorsal” area was defined as the septal mucosa region from the apex of the dorsal recess to the point opposite the dorsal edge of endoturbinate II. The “ventral” area was defined as the septal region that extends from the point opposite the ventral edge of endoturbinate II to the respiratory epithelium. Since the shift in severity of the MeBr lesion is proceeds gradually from dorsal to ventral, the area of the septum that corresponds with the endoturbinate II was excluded from analysis to contrast the cellular response of dorsal vs. ventral areas.

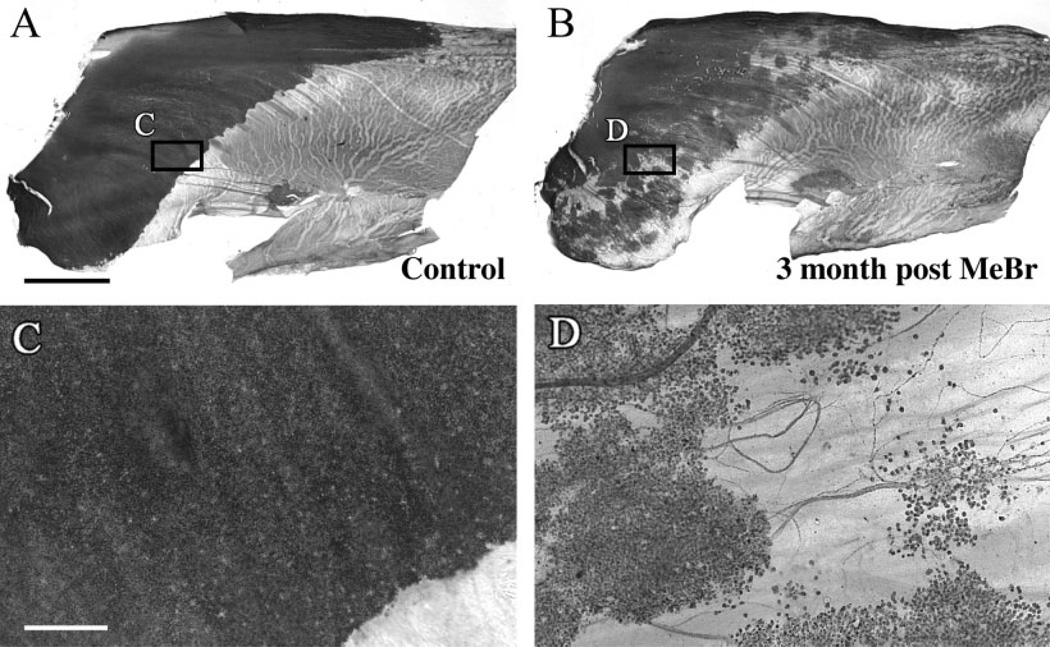

Fig. 1.

Recovery is incomplete even 3 months after MeBr lesion of chronically food-restricted animals, as shown in OMP-stained whole mounts of the normal septum. Septa from a control animal (A) and animal sacrificed 3 months after exposure to MeBr lesion (B) were stained with anti-OMP to label mature neurons. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification. Mature neurons form a uniformly dense sheet in control animal (C), compared with discontinuous “patchy” clusters of neurons surrounded by nonneuronal areas in the lesioned animal (D). Scale bar = 2 mm in A,B; 200 µm in C,D.

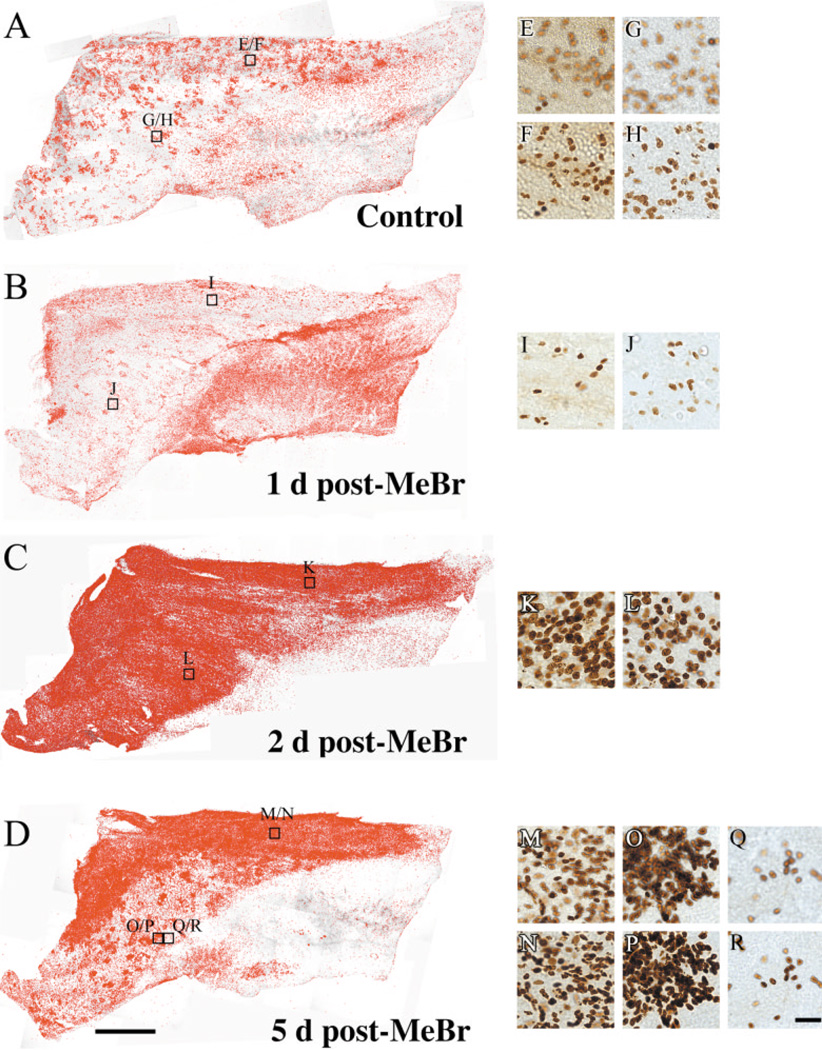

Fig. 2.

The distribution of proliferating cells correlates with the recovery of lesioned epithelium as olfactory. Whole mount of septal mucosae stained with anti-BrdU in control (A), 1 day (B), 2 days (C), 5 days post-MeBr lesion (D) animals showing that distribution of proliferating cells increasingly resembles that of neuronal regeneration (A–D). BrdU(+) cells were highlighted on mosaics of BrdU-stained whole mounts using IPLab Spectrum image analysis software; boxed areas are shown at higher magnification. E–R: High-magnification photomicrographs of stained samples. The number of BrdU(+) cells is markedly increased in all areas of the nasal septum at 2 days after lesion (C), but it drops precipitously in many parts of the ventral epithelium at 5 days after lesion (D); their distribution closely resembles that of neurons across ventral epithelium (cf. Fig. 1B). In control mucosa and at 5 days after lesion the photomicrographs were focused at levels just above the basal lamina (F,H,N,P,R) and on the apical surface of the epithelium (E,G,M,O,Q), while at 1 and 2 days after lesion only the level of the basal lamina was photographed due to the thickness of the epithelium (I,J,K,L). At 5 days postlesion, note the difference in the number of proliferating cells in adjacent areas of ventral epithelium (O,P vs. Q,R). BrdU(+) cells are limited to the vicinity of the basal lamina in areas where proliferation is less robust (Q vs. R). Scale bar = 2 mm in D applies in A–C; 50 µm in R applies in E–Q.

Cell counts were performed for purposes of validating the data observed at 2 days after lesion for GBC-2(+) cells (Fig. 4) and at 4 and 7 days after lesion for TuJ-1(+) neurons (Figs. 5, 6). GBC-2(+) cells were counted on sections taken at three different levels through the anteroposterior extent of the epithelium from three rats lesioned 2 days prior to perfusion. GBC-2-stained sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and “GBC-2(+) profiles” were separately counted in dorsal vs. ventral parts of the lesioned septa. The length of the counted area of the epithelium in mm was determined and used to normalize the cell counts. For Tuj-1, one animal sacrificed at 4 days and another sacrificed at 7 days after lesion were used for the counts. The averaged numbers of TuJ-1(+) cells from the three different levels were also normalized to the length (mm) of the epithelium.

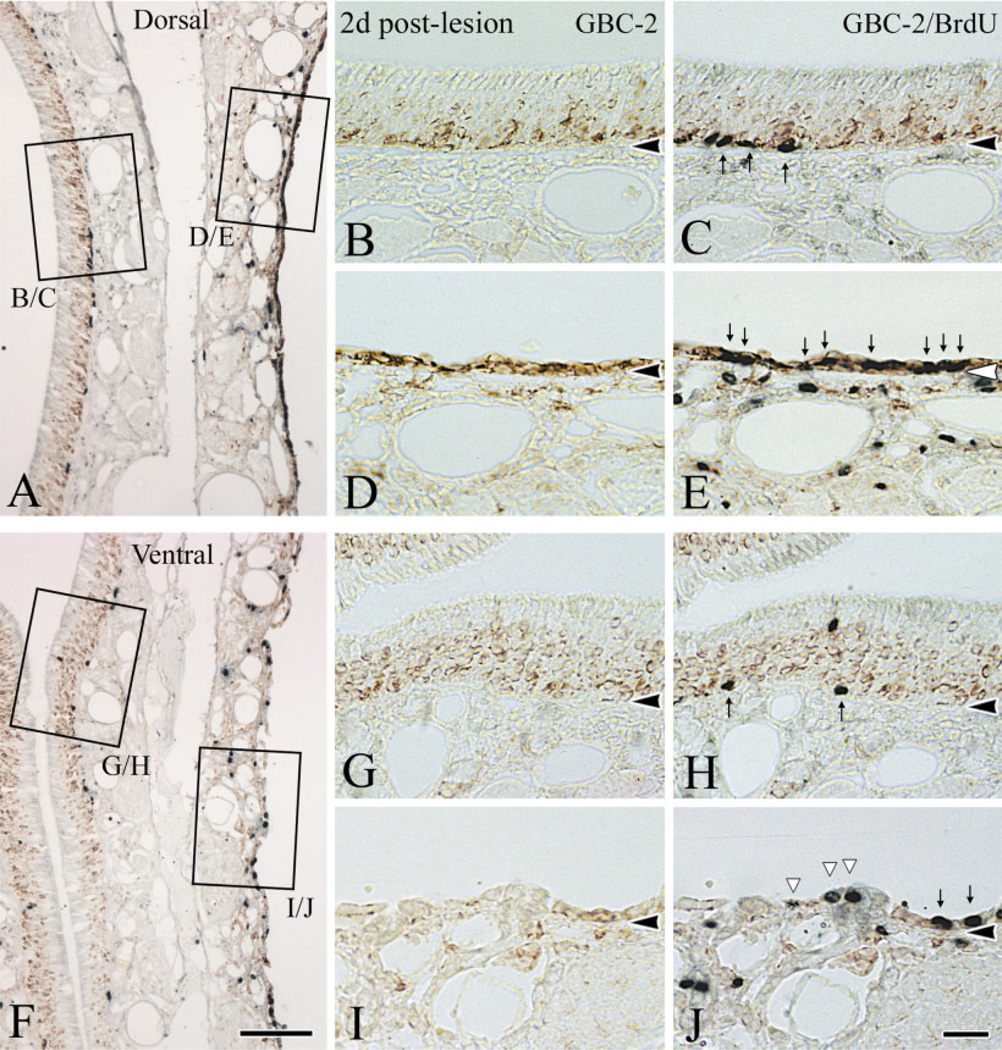

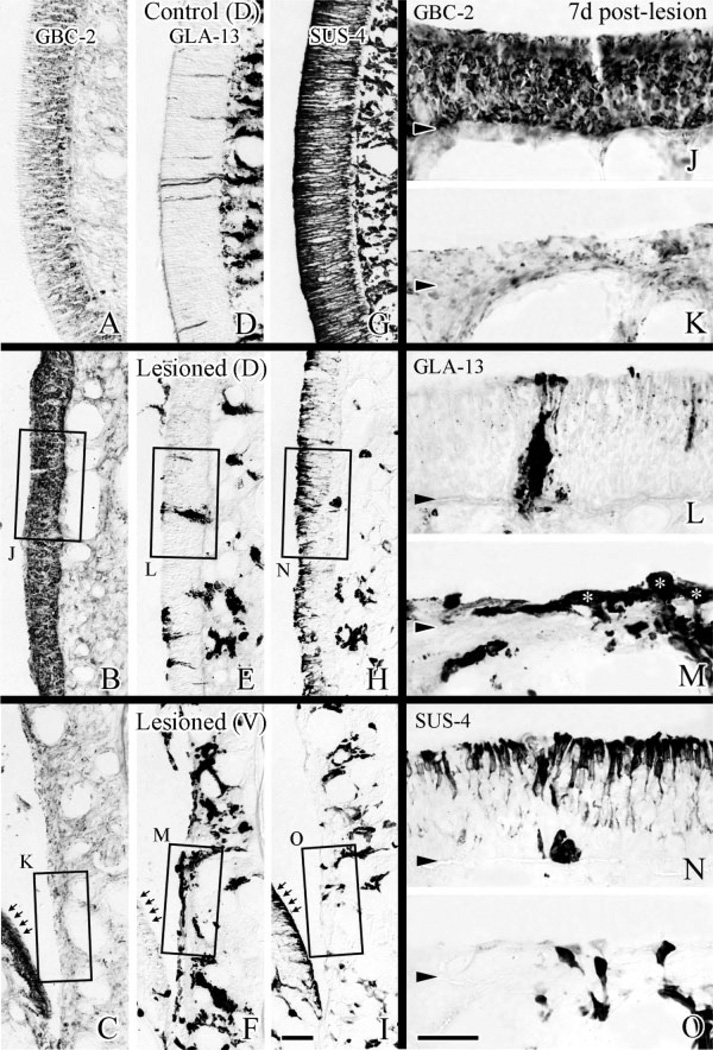

Fig. 4.

The proliferating populations are different in dorsal (A, low magnification and B–E, high magnification) vs. ventral (F, low magnification and G–J, high magnification) epithelium at 2 days after lesion. The vast majority of proliferating cells dorsally are GBC-2(+) GBCs while many of the proliferating cells seen ventrally are not GBCs. Sections were stained with GBC-2, photographed (B,D,G,I), and then stained with anti-BrdU (C,E,H,J). Note the markedly increased immunoreactivity of GBC-2 in dorsal epithelium after lesion (D) compared to control side (B). In lesioned epithelium (D,E,I,J), all BrdU(+) cells are GBC-2(+) in dorsal area (indicated by thin arrows in E), while some BrdU(+) cells are GBC-2(−) in the ventral counterpart (indicated by white triangles in J). Indeed, some of the proliferating cells in ventral epithelium are gland cells (cells designated by the middle and righthand white triangles in J). Scale bar = 100 µm in F applies in A; 25 µm in J applies in B–E and G–I. Arrowheads indicate the basal lamina.

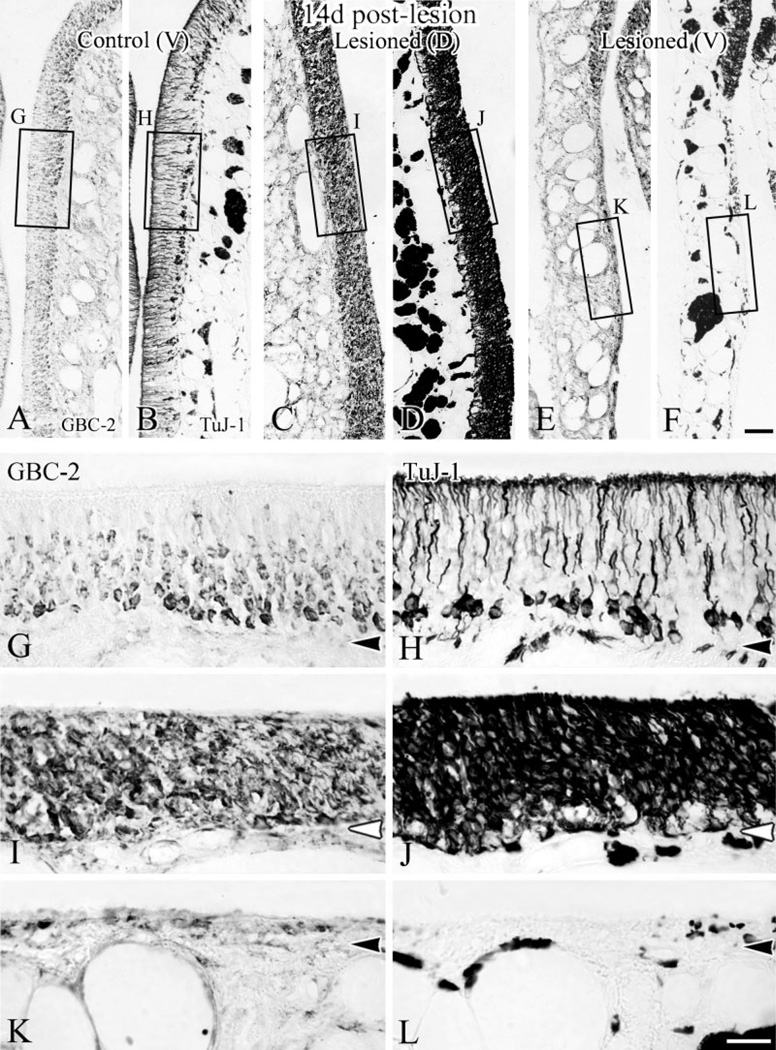

Fig. 6.

The distributions of GBCs and of regenerating neurons are well matched 14 days after lesion. The staining patterns with GBC-2 and TuJ-1 are shown at low magnification in control (A,B), and in lesioned epithelium from a dorsal area (C,D) and a ventral area (E,F). G–L: Higher magnification from boxed areas in A–F. The dorsal epithelium is full of neurotubulin(+), immature neurons (J), some of which are also GBC-2(+) (I). In ventral epithelium neurons are lacking where GBCs remain absent (K,L). While dorsal epithelium has regenerated to the thickness of the control, the metaplastic ventral epithelium is thin by comparison with the control or its dorsal counterpart. Scale bar = 50 µm in F applies in A–E; 20 µm in L applies in G–K. Arrowheads indicate the basal lamina.

Electron microscopy

Tissues for electron microscopic examination were obtained according to the previously published protocol (Schwob et al., 1992). Briefly, animals were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde / 0.6% paraformaldehyde in 0.06 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2. Tissues were then post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour, dehydrated, and embedded in Araldite before examining with a transmitted electron microscope (TEM).

RESULTS

Regional differences in the recovery of the olfactory cellular population

Our previous reports showed that mature neurons, identified by the OMP expression, begin to reappear 2 weeks after lesion and reach near-normal numbers by 6 weeks after MeBr lesion (Schwob et al., 1995). However, we also reported that parts of the anterior and ventral septal olfactory mucosa do not recover as olfactory under some circumstances and lack olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs). Thus, the mucosa in that anteroventral area forms a discontinuous sheet of OMP(+) neurons even at very long survivals after lesion (see Fig. 13 in Schwob et al., 1995). The present results extend that observation (Fig. 1). We find that the exposure to MeBr in food-restricted animals consistently leads to metaplasia of parts of the ventral and anterior olfactory epithelium and its recovery as respiratory epithelium. Even with an extended recovery time of 5 months after MeBr lesion, patches of respiratory epithelium still persist and interrupt the mucosa in anterior and ventral locations (Schwob et al., 1995), which is noticeably contrary to the control side or the posterodorsal part of the septum which contain a smooth, continuous sheet of OMP(+) neurons. The failure of reconstitution of the olfactory epithelium was observed in each of greater than 20 rats exposed while food-restricted and varied from 10–30% of the surface area of the septum in a smaller group subject to septal whole-mount analysis. Thus, examination of ventral olfactory epithelium under such conditions offers us an opportunity to examine areas at substantial risk for metaplasia and assess the correlates of that risk.

The variation in the recovery of dorsal and ventral epithelium and the contrast between ventral olfactory epithelium that recovers and that which does not correlates closely with the differences in cellular proliferation in those areas. We examined the distribution of BrdU(+) cells in septal whole mounts of animals killed at various times after MeBr lesion. We previously reported that cell proliferation exceeds control at 2 days after lesion and peaks at 7 days after lesion (Schwob et al., 1995). Our present results show that the immense increase in cell proliferation during this time point is uniform only in the dorsal region of the epithelium. In contrast, while proliferation is dense and widespread ventrally at 2 days after lesion (Fig. 2C), by 5 days the distribution of dividing cells is already spotty: foci with a high density of BrdU(+) cells are surrounded by areas where the proliferation rate has dropped precipitously (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, the patchy distribution of a high density of mitotic cells closely mirrors the intermittent distribution of neurons in the ventral olfactory epithelium (i.e., where it recovers as olfactory epithelium) (cf. Figs. 1, 2D). When examined closely by changing the focal plane onto the epithelium of the whole mount, the majority of the BrdU(+) cells are close to the basal lamina in the control epithelium (Fig. 2F,H). At 1 day after lesion, the smaller number of proliferating BrdU(+) cells are still located just superficial to the basal lamina, regardless of the dorsal and ventral septum (Fig. 2I,J), indicating that they are either spared basal cells or Bowman’s duct cells. At 2 days after lesion, the proliferating cells span the entire septal olfactory epithelium throughout the much-reduced thickness of the epithelium without clusters (Fig. 2K,L). At 5 days after lesion, in the dorsal epithelium and in ventral patches where the BrdU(+) cells are clustered, the proliferation profile is maintained as the BrdU(+) cells span the thickness of the epithelium (Fig. 2N–P). However, in the ventral areas where the BrdU(+) cells are sparse, the location of those BrdU(+) cells remain immediately superficial to the basal lamina, which is comparable to their location 1 day after lesion (Fig. 2Q). The significance of this change in the proliferation profile will be discussed (see Discussion). Here, we provide further analysis of the cellular composition in the two areas (dorsal vs. ventral) of the septal olfactory epithelium during reconstitution after MeBr lesion.

In keeping with the differential response to lesion between dorsal and ventral epithelium, the extent of the damage to the epithelium also differs between the two regions (Fig. 3). In order to identify the extent of cell sparing after lesion, we stained sections with PAN-4, an antibody from our laboratory, and anti-laminin to label the basal lamina. PAN-4 is a monoclonal IgG antibody against an anonymous antigen produced by immunizing mice with dissociated cells from MeBr-lesioned rat olfactory epithelium (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996). PAN-4 labels all cells derived from the olfactory epithelium: sus-tentacular cells, duct/gland cells, OSNs and their axons, HBCs, and GBCs. In addition, respiratory epithelium lining nasal cavity is also labeled by PAN-4. Thus, cells that survive the lesion can be identified as indicated. At 1 day postlesion, the dorsal basal lamina in the dorsal mucosa is lined by a continuous single layer of cells (Fig. 3B), while the ventral epithelium contains areas that are totally devoid of cells, i.e., areas in which the basal lamina is completely denuded (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that the ventral epithelium is more severely damaged than the dorsal epithelium. Thus, the difference in the severity of the damage in two areas may dictate the differential recovery. To address this possibility further, we used a number of cell-type-specific markers to assess directly how the two areas respond differently to the differentially severe injury.

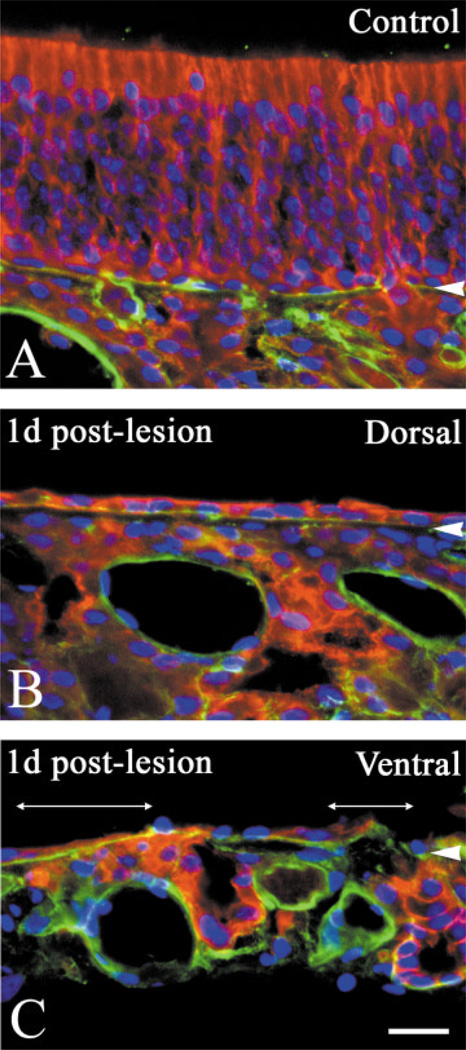

Fig. 3.

Exposure to MeBr gas causes differential damage to dorsal vs. ventral epithelium. Double labeling with anti-laminin (green) and PAN-4 (red) along with nuclear staining with Hoechst 33258 (blue) on tissues from 1 day after lesion on the control side (A), dorsal (B), and ventral (C) areas on the lesioned side. In the dorsal mucosa there is a continuous layer of cells above the basal lamina (B). In contrast, the basal lamina is completely denuded in some parts of ventral mucosa (under two-headed lines in C). Scale bar = 25 µm in C applies in A,B. Arrowheads indicate the basal lamina.

By 2 days after lesion the differences between dorsal and ventral areas and between different parts of the ventral epithelium have become more substantial. At this time, GBC-2-labeled GBCs are prevalent in dorsal epithelium and form a continuous band of densely stained profiles one or more layers thick (Fig. 4D). Indeed, the level of expression per cell looks to be greater for GBCs on the lesioned-recovering side as compared with the unlesioned epithelium (cf. Fig. 4D,B). In contrast, the number of GBC-2-stained profiles is much less in ventral olfactory epithelium and is discontinuous (Fig. 4I). When GBC-2(+)-labeled profile were counted on sections at three different levels in three animals, 28.6 ± 8.2 profiles/mm were found in the ventral area as compared to 58.4 ± 7.4 profiles/mm in the dorsal area. There is no systematic difference between the size of cells in dorsal vs. ventral epithelium (Fig. 4 and data not shown). Hence, the relative density of profiles corresponds closely to the relative density of labeled GBCs. Thus, there are roughly twice as many GBCs in dorsal epithelium as compared to ventral at this point. Indeed, it is likely that the relative discrepancy between the two areas is greater than 2-fold, because the density of labeled profiles in dorsal epithelium is such that counts are likely to be an underestimate of the total in dorsal epithelium (Fig. 4). Double-labeling with an anti-BrdU antibody indicates that most of the proliferating cells located superficial to the basal lamina in dorsal olfactory epithelium are GBC-2(+) (Fig. 4E). Only some of the proliferating cells in ventral epithelium are GBC-2(+), while other BrdU(+) cells found above the basal lamina are displaced gland cells (Fig. 4J).

The variable severity of the damage (Fig. 3) and the differential persistence of the GBC population (Fig. 4) translate into the differential recovery of the neuronal population after MeBr lesion. In dorsal olfactory epithelium of these animals, the timing of reconstitution of the neuronal population closely follows that which we de- scribed previously as the course of recovery after MeBr lesion (Schwob et al., 1995). Immature neurotubulin-expressing neurons are first observed 3 days after lesion and rapidly increase in number through the first 2 weeks after lesion (Figs. 5B,D, 6D). The majority, if not all, of the TuJ-1(+) cells are also GBC-2(+) on the lesioned side (Figs. 5E, 6I). Even at this and later time points, the number of GBC-2(+) GBCs can be ascertained by comparison with the TuJ-1(+) staining on adjacent sections. In contrast, large areas of ventral olfactory epithelium remain devoid of any GBCs or neurons, even as long as 14 days after lesion, as expected from the distribution of nonolfactory epithelium at very long time points after lesions of this severity (cf. Figs. 1, 5H, 6L). It is unlikely that any of these aneuronal areas are likely to recover, given the progress toward recovery in surrounding areas, and the appearance of an epithelium that consists of columnar respiratory epithelial cells in areas lacking GBCs and neurons. Surrounding these aneuronal patches in ventral epithelium are areas where the neuronal population is reconstituting in similar fashion and with similar timing as in dorsal epithelium. In these, a substantial number of GBC-2(+) GBCs is evident within 2 days after lesion and an ever-increasing population of immature neurons is evident between 3 and 14 days after lesion as in dorsal epithelium (cf. Figs. 5C, 6E). The disparity in the number of GBC-2(+) cells in the dorsal vs. ventral epithelium noted above is closely correlated with a disparity in the number of the TuJ-1(+) cells between dorsal and ventral epithelium. At 4 days after lesion, the number of the TuJ-1(+) cells is almost 9 times higher than in the dorsal area than in the ventral area (29.2/mm vs. 3.3/mm). When counted after 7 days after lesion, the ratio of the number of TuJ-1(+) cells per mm of epithelium in the dorsal and ventral area becomes 2.6:1 only because of an increasing population of the TuJ-1(+) cells in the patches that are becoming neuronal (194.7/mm vs. 74.3/mm).

Role of duct and gland cells in reconstitution of the ventral epithelium

We also assessed the reaction of cells of Bowman’s gland and ducts (BG/D) and sustentacular cells to lesion using monoclonal antibodies GLA-13 and SUS-4, respectively, which were generated in our laboratory (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996). In particular, we compared the distribution of BG/D cells within areas of the epithelium likely to recover as olfactory, i.e., in which GBC-2(+) cells were preserved vs. areas where GBC-2(+) cells are absent. The distribution of BG/D cells, hence the response of the population, differs between dorsal and ventral olfactory epithelium, particularly in areas of ventral epithelium in which GBC-2(+) cells are absent. We also found that expression of the antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody SUS-4 is differentially regulated, later to reappear, and can be dissociated from the expression of the GLA-13 antigen.

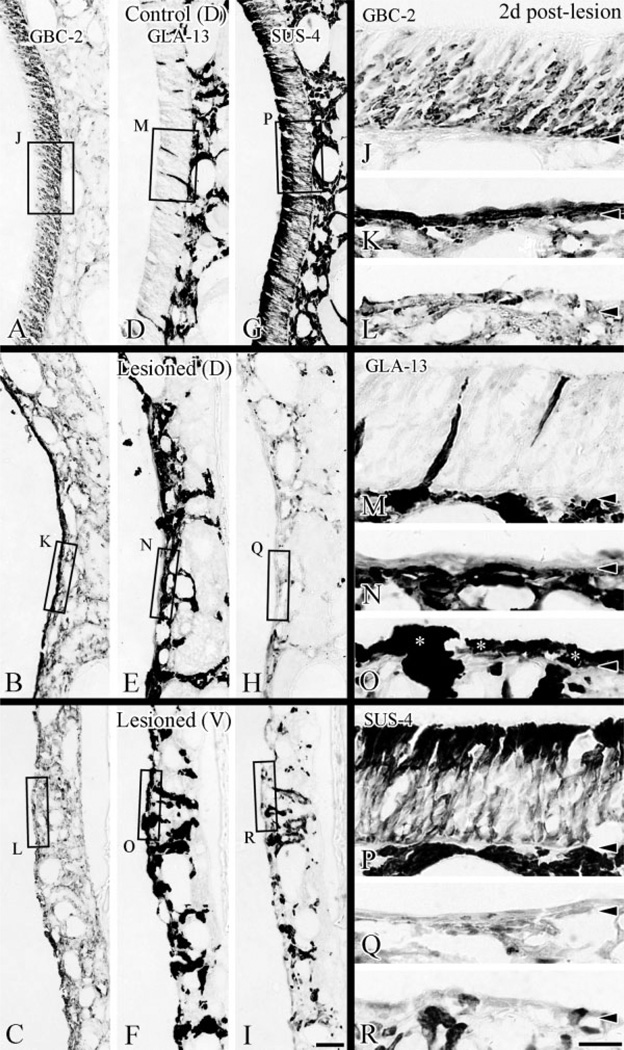

As indicated above, GBC-2(+) cells are more numerous dorsally than ventrally at 2 days after lesion. The equivalent areas on adjacent sections indicate that GLA-13 staining is retained in glands and ducts extending apically through the olfactory epithelium, while SUS-4 staining is largely suppressed in those cells in contrast with the control epithelium where all GLA-13(+) cells are SUS-4(+) (cf. Fig. 7D,G vs. E,H or F,I). Most strikingly, GLA-13(+) cells accumulate superficial to the basal lamina on the lesioned side, particularly in ventral areas (Fig. 7F,O), and to a lesser extent in dorsal epithelium (Fig. 7E,N). In ventral areas on the lesioned side, GLA-13-labeled cells occupy a substantial proportion of the tangential extent of the epithelium, particularly where GBC-2-labeled cells are lacking (cf. Fig. 7K,L vs. 7N,O). Unlike the control epithelium, these GLA-13(+) cells on the lesioned side are not labeled with SUS-4, indicating that they have assumed a less differentiated phenotype.

Fig. 7.

BG/D cells expand into the ventral epithelium that lacks GBCs after lesion. Adjacent sections from an animal at 2 days after lesion were stained with GBC-2 (A–C; J–L at higher magnification), GLA-13 (D–F; M–O for higher magnification) and SUS-4 (G–I; P–R at higher magnification). In lesioned dorsal epithelium where GBC-2(+) cells are predominant (K), GLA-13(+) cells remain below the basal lamina for the most part (N), while in ventral area where GBC-2(+) cells are absent (L), GLA-13(+) cells begin to pile up above the basal lamina and spread away from the duct penetrating the basal lamina (asterisks in O). Sustentacular cells labeled by SUS-4 disappear from the whole of the nasal septal mucosa (Q,R). Moreover, GLA-13(+) cells on the lesioned side are poorly and inconsistently labeled with SUS-4 (H,I), in contrast with the strong positivity for both GLA-13 and SUS-4 in the mucosa on the control side (D,G). Scale bar = 50 µm in I applies in A–H; 20 µm in R applies in J–Q. Arrowheads indicate the basal lamina.

By 7 days after lesion, areas that are recovering as olfactory are becoming well demarcated from those that are undergoing metaplasia with respect to the expression of the BG/D cells and sustentacular cells (Fig. 8B,C). Where recovery is ongoing, the epithelium is thick, becoming pseudostratified, and beginning to show SUS-4(+) labeling at its apex. Here, GLA-13(+) cells form a narrowing column that extends through the olfactory epithelium, the latter structures presumably correspond to reorganizing ducts. In areas that appear to be metaplastic, GLA-13 labeling is becoming less prominent in the epithelium, but labeling with SUS-4 and GBC-2 remain absent. The contrast between recovering and metaplastic epithelium is evident whether the recovering epithelium is located dorsally or ventrally (note recovering area on turbinate facing metaplastic ventral epithelium; arrows in Fig. 8C,F,I).

Fig. 8.

At 7 days after lesion, cellular composition in dorsal epithelium is substantially like normal, while not so in ventral epithelium. Sections labeled by GBC-2 (A–C), GLA-13 (D–F), and SUS-4 (G–I) are shown at low magnification. J,L,N: High magnification of dorsal epithelium. K,M,O: High magnification of ventral epithelium. In dorsal epithelium, elongated, GLA-13(+) duct-like structures (L) and SUS-4(+) cells (N) reappear in addition to GBC-2(+) cells, which span an epithelium (J) approximating the thickness of the control side (A). In ventral epithelium, GBC-2( + ) cells and SUS-4(+) cells are still absent (K,O) in areas where GLA-13( + ) cells spread over the basal lamina (asterisks in M). Arrows in C,F,I indicate the areas recovering as olfactory in contrast to areas undergoing metaplasia shown in K,M,O. Scale bar = 25 µm in I applies in A–H; 25 µm in O applies in J–N. Arrowheads indicate the basal lamina.

By 14 days after lesion the process of recovery is well underway in those areas that are reconstituting as olfactory (see Fig. 6D). The epithelium is full-thickness, although the neuronal population is predominantly composed of immature neurons. In particular, ducts extend to the apical surface of the epithelium and closely resemble the ducts on the control side, except that the staining of the reconstituting ducts is noticeably more intense on the lesioned side (data not shown).

With regard to the ventral epithelium, in those areas where recovery as olfactory fails, the process of respiratory metaplasia appears to be advanced as well (Fig. 9). In areas such as these, neurons are absent or rare (Fig. 9G). In the latter case, they are intermingled with cilia-capped columnar respiratory epithelial cells, which can be recognized by their distinctive appearance in H&E-stained sections (Fig. 9G,H). One aspect that differentiates metaplastic areas from normal respiratory epithelium at this stage is the presence of GLA-13(+) cells superficial to the basal lamina. GLA-13(+) labeling is not seen in or deep to respiratory epithelium normally (data not shown). Eventually, the GLA-13 staining becomes restricted to the lamina propria of the metaplastic epithelium, where it remains for as long as 7 weeks after lesion. Hence, the persistence of GLA-13(+) cells indicates areas that were olfactory prior to lesion but have undergone respiratory metaplasia as opposed to epithelium that was originally respiratory.

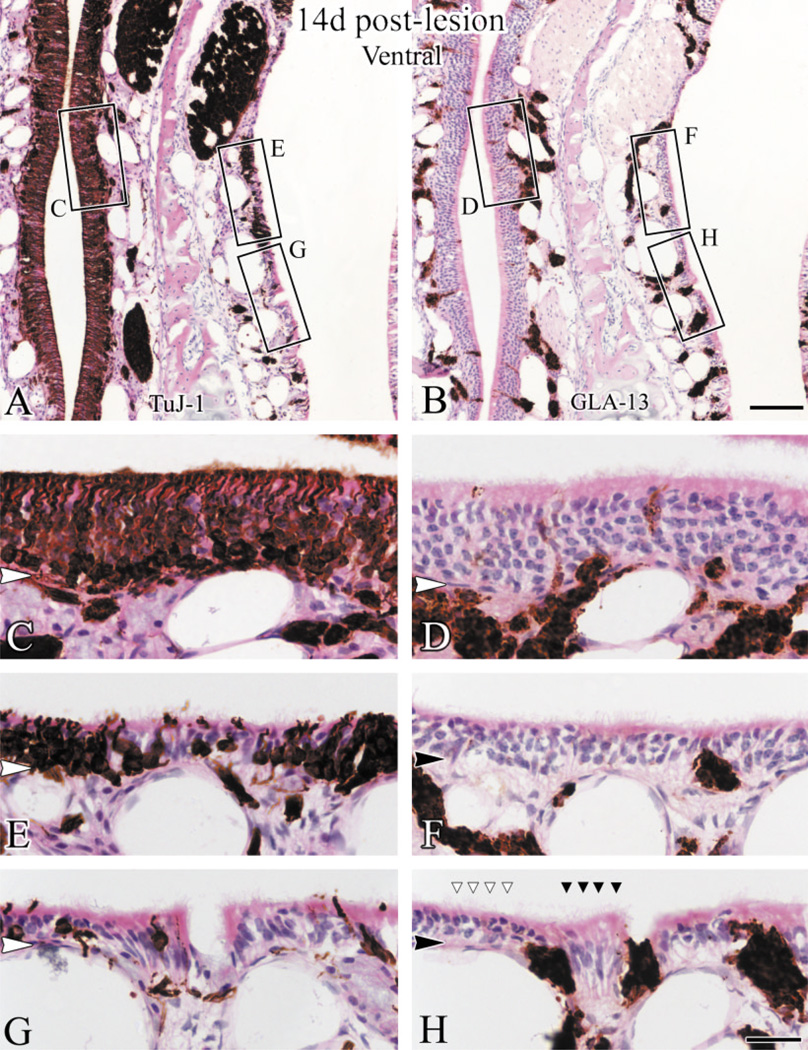

Fig. 9.

Areas of the ventral epithelium that closely resemble mature respiratory epithelium are apparent 14 days after lesion. Sections were stained with TuJ-1 (A) and GLA-13 (B) and counterstained with H&E. C–H: high magnifications of boxed areas in A,B. In areas of epithelium where TuJ-1(+) cells are predominant (E), GLA-13(+) cells are rare (F). Reconstituting olfactory areas, which resembles the control side in C and D, are surrounded by epithelium where TuJ- 1(+) cells are absent (G) and GLA-13(+) cells are found superficial to the basal lamina (H). In “neuron-free” areas, the epithelium is populated by cells that appear to be ciliated columnar respiratory cells (dark arrowheads in H designate ciliated, columnar cells) and flanked by neurons (white arrowheads in H). Scale bar = 50 µm in B applies in A; 25 µm in H applies in C–G. Arrowheads indicate the basal lamina.

Ultrastructure of the regenerating epithelium

In order to contrast more fully the cellular population between recovering and metaplastic epithelium and, in particular, to characterize the likely GLA-13(+) cells, the regenerating epithelium was examined with the electron microscope (EM). The tissue preparation was designed to produce separation of cells in order that the individual cells and their structure be seen in isolation. In dorsal olfactory epithelium at 3 days postlesion (Figs. 10A, 11A), the cellular composition is rich and diverse throughout. Among the cell types are: 1) cells resembling GBCs in normal olfactory epithelium; 2) darker cells surrounding them, extending to the surface with putative microvilli; 3) others that are intermediate in appearance with light cytoplasm and elongated profile being displaced toward apical surface. Previous results indicate that cells with a shape and distribution similar to the second type express CK 5/14, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R), and other markers that are characteristics of HBCs (Schwob et al., 1995; Holbrook et al., 1995; Goldstein and Schwob, 1996)

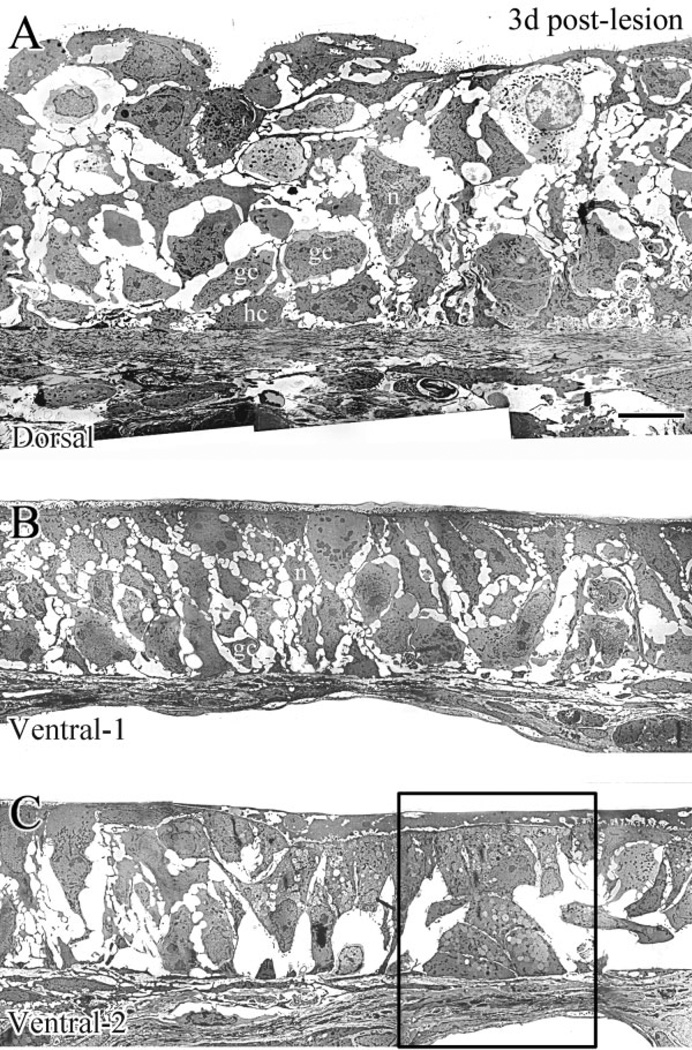

Fig. 10.

EM examination of the dorsal (A) and the ventral (B,C) epithelium at 3 days after MeBr lesion. A: The dorsal epithelium is rich in GBCs (gc), HBCs (hc), and regenerating neurons (n). B: In some ventral areas, the epithelium looks comparable to its dorsal counterpart (see A) in that GBCs (gc) and regenerating neurons (n) are relatively abundant. C: In other ventral areas, cellular constituents are much sparser and GBCs are rarely found (cf. B,C). Note that HBCs are rare in both B and C in comparison to A. The boxed area in C is shown at high magnification in Fig. 11B. Scale bar = 5 µm in A applies in B,C.

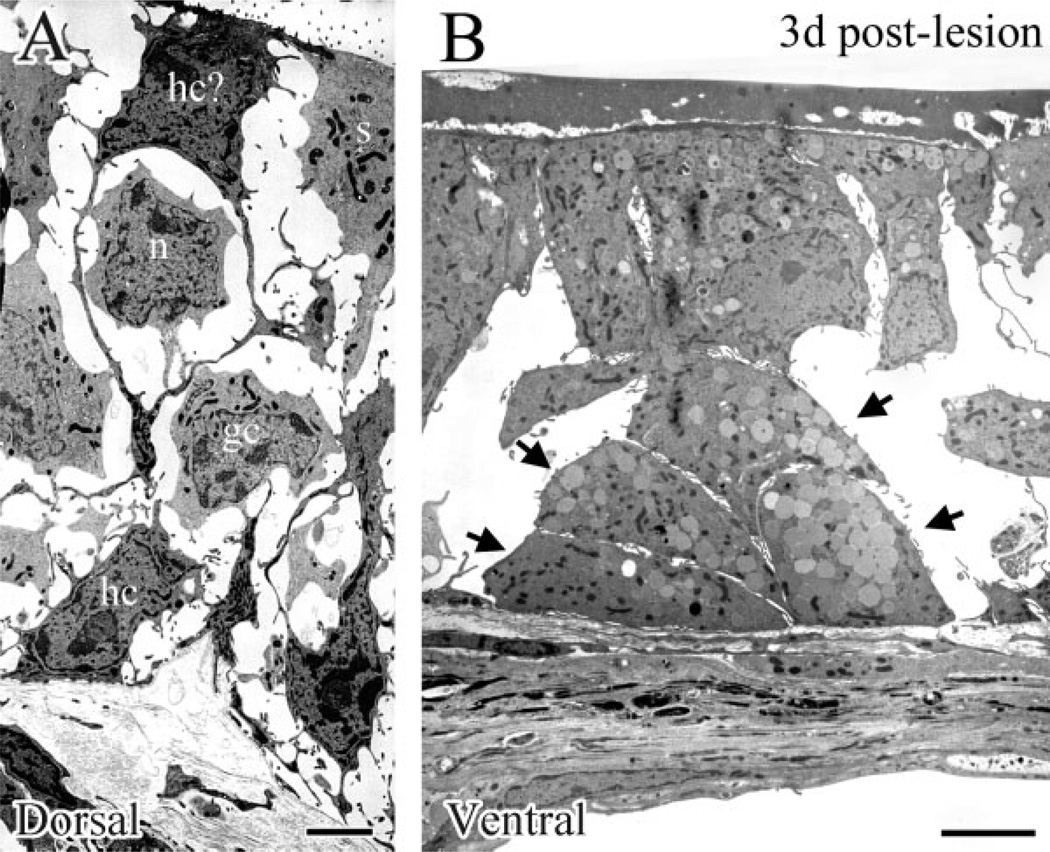

Fig. 11.

EM examination at high magnification of dorsal (A) and ventral (B) epithelium at 3 days after MeBr lesion. A: HBCs (hc) are identified by their juxtalaminar position and finger-like projections, while GBCs (gc) are rounder and lack microvilli. Some dark cells, which extend up through the epithelium, closely resemble HBCs (hc?). These cells have been shown to be CK5/ 6(+) when examined by light microscopy (Schwob et al, 1995). Note that immature sustentacular cells (s) are also present at the apex of the epithelium. B: Higher magnification of the boxed area in Figure 10C. Gland cells with secretory vesicles are indicated by the arrows. Scale bars = 225 µm.

In contrast, the EM appearance of the ventral epithelium is much more variable across its extent (Fig. 10B,C). In some areas, the cellular environment is relatively rich, although the darker cells with the characteristics of HBCs are rare (Fig. 10B); the apparent absence of EM-identifiable HBCs is consistent with published light microscopic (LM) immunohistochemical results (Schwob et al., 1995; Holbrook et al., 1995; Goldstein and Schwob, 1996). Other cellular constituents closely resemble ones from dorsal epithelium, including some cells that look like GBCs. In other areas of ventral epithelium at 3 days after lesion (Figs. 10C, 11B) the cellular constituents are much sparser as compared with dorsal olfactory epithelium. In keeping with LM results with GLA-13 staining, gland cells—identified by secretory vesicles in their cytoplasm—are found superficial to the basal lamina, while other cells span the width of the epithelium and bear primitive microvilli (Fig. 11B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, limits on the capacity of the olfactory epithelium to recover from severe injury (e.g., MeBr exposure in food-restricted rats) were revisited. As noted before, the extent and severity of damage caused by exposure to MeBr gas varies with the animal’s nutritional status at the time of lesion. When rats are maintained at 75% ad libitum body weight, some areas (exclusively rostral and ventral) of the olfactory epithelium reconstitute after lesion as respiratory epithelium rather than olfactory, which is a form of metaplasia. The results focus on the sequence and cellular characteristics of epithelial re-constitution after MeBr injury, contrasting recovery as olfactory from metaplasia.

Previous studies on the reconstitution of olfactory epithelium after MeBr lesion form an essential backdrop against which to contrast these processes. An important feature of recovery of lesioned epithelium as olfactory is the activation of two types of multipotent progenitors (MPP) shortly after MeBr exposure (Huard et al., 1998). The first, thought to be a GBC on a variety of grounds, has the capacity in rats to give rise to GBCs, neurons, susten-tacular cells, and HBCs. The other, thought to be a duct cell, gives rise to sustentacular cells and BG/D cells. The present results extend previous observations and clarify the nature of the stem cells ultimately responsible for maintaining the neuronal population—which may be distinct from, and more primitive than, the multipotent GBCs noted above.

To recapitulate, we report here that exposure to MeBr under these conditions causes more profound damage to the epithelium that is at risk for metaplasia than to areas that reliably recover as olfactory. In these at-risk areas, the spared cells form an interrupted layer and areas where the basal lamina is denuded are interspersed between cells that survive the lesion. In particular, the sparse, spared cells in the anteroventral epithelium have the phenotypic characteristics of GBCs (determined both by immunochemical and EM analysis) and their distribution at 2 days after lesion correlates with the patches that do recover as olfactory. That interspersed ventral areas where GBCs are spared do recover as olfactory suggests that failure to recover as olfactory is not due to differences in the regenerative capacity of GBCs in the two areas.

Critical to any evaluation of the cells that are spared lesion and participate in epithelial reconstitution are the reagents that are used to mark the cells and their specificity. GLA-13 and TuJ-1 are demonstrably specific for BG/D cells and immature neurons, respectively, based on current and published data. SUS-4 appears to be specific for more mature sustentacular cells and BG/D cells as its expression, even in areas of the lesioned epithelium that recover as olfactory, lags that of another sustentacular cell-specific marker, namely CK-18 (Schwob et al., 1995). Given our working hypothesis, implicating GBCs—and more specifically, their destruction—as the cause of respiratory metaplasia, the ability to identify GBCs is especially important. We have used the monoclonal antibody GBC-2 to identify GBCs positively at short time points after lesion, which was developed by immunizing with FACS-isolated proliferating GBCs (Goldstein et al., 1997). The distribution of the antigen recognized by GBC-2 in normal epithelium indicates that the antibody does indeed label most, if not all, GBCs (Goldstein et al., 1997; data not shown). However, immunoreactivity carries over to the population of immature neurons in the normal epithelium, as is characteristics of other GBC-reactive monoclonal antibodies generated in our laboratory (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996; Goldstein et al., 1997).

In similar fashion, cells are found that label with both GBC and HBC or GBC and sustentacular cell markers. The coexpression of GBC and other cell type-specific markers is observed with either GBC-1 (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996) or GBC-2 (data not shown). These data are in keeping with the activation of multipotent-GBC progenitors by MeBr lesion and suggest that labeling carries over to nonneuronal derivatives of GBCs at early stages in the regeneration of the epithelium as well as neurons (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996; Goldstein et al., 1997). Thus, GBC-2 serves our intent to trace the GBC population immediately after lesion and during the subsequent recovery of the epithelium, particularly in the context of the neuronal population. It is striking that GBC-2 immunoreactivity is markedly increased on the spared and proliferating cells above the basal lamina shortly after MeBr exposure, which makes the absence of staining in areas of ventral epithelium more striking. GBC-1, whose antigen is a glycolipid (Goldstein and Schwob, 1996), apparently labels only subsets of GBCs remaining at early times after MeBr, while GBC-2, as reported here, appears to stain most, if not all, GBCs in the normal and dorsal recovering epithelium (Figs. 4–8). In keeping with its ubiquity, the GBC-2 antigen is expressed in all cells of an olfactory-derived cell line, NIC cell line, when cultured in rich medium, while GBC-1 antigen is expressed in only a small percentage of cells (Goldstein et al., 1997). These findings suggest that GBC-2 is an earlier marker than GBC-1 in the lineage of the multipotent GBCs. The nature of the antigen for GBC-2 is not clear at this point, although the monoclonal antibody labels a doublet of 30–35 kDa on Western blots and reacts with a carbohydrate moiety, as shown by free lactose-blockade of GBC-2 staining of sections and blots.

The disjunction between colabeling of both sustentacular cells and BG/D cells by SUS-4 in normal epithelium (Figs. 7, 8; normal epithelium) and lack of staining of BG/D cells immediately after lesion indicates a different regulation of SUS-4 vs. GLA-13 expression. The delay in expression of SUS-4 is worthy of note, but does not militate against our hypothesis that sustentacular cells and BG/D cells share a common lineage in the lesioned epithelium (Schwob et al., 1995; Huard et al., 1998). Nor does it hamper our attempt to dissect cellular dynamics of regenerating epithelial cells after lesion. The elimination of SUS-4 expression can be permanent. GLA-13(+) cells which persist deep to epithelium that has undergone respiratory metaplasia remain SUS-4(–) as long as 7 months after lesion.

Our hypothesis that the destruction of GBCs in ventral epithelium is responsible for the onset of metaplasia requires further discussion of three aspects. First, why is ventral epithelium more susceptible to metaplasia? Second, are GBCs the stem cells for the neural epithelium? Third, what cells give rise to the respiratory epithelium, where it forms instead of olfactory? Each will be considered in turn.

Selective sensitivity of ventral epithelium

We suggest above that destruction of the GBC population in areas of ventral olfactory epithelium is the ultimate cause of the respiratory metaplasia. However, that is not the only difference between dorsal and ventral epithelium. Cells derived from BG/D take up residence superficial to the basal lamina of the epithelium that is undergoing metaplasia, arranging themselves in mounds, and retain a glandular phenotype. In contrast, some GLA-13(+) cells do invade epithelium that is reconstituting as olfactory, but eventually become aligned in ducts spanning the epithelium.

Because GLA-13(+) cells also invade the epithelial counterpart dorsally as well as ventrally, and because the changes in gland cell distribution are subsequent to differential damage, we do not favor the notion that altered BG/D behavior is the underlying reason for metaplasia. Thus, the intriguing question becomes why and how GBCs persist differentially in dorsal vs. ventral epithelium. The most likely explanation for selective sensitivity, although speculative, derives from the physical differences between dorsal vs. ventral epithelium, specifically the difference in thickness between the two. Sensitivity to the olfactotoxic effects of MeBr gas are mediated via sustentacular cells; that statement is based on the fact that prior exposure to environmental chemicals that affect the biotransformation system modulates sensitivity (Hurtt et al., 1988) and that no damage is observed when sustentacular cells are immature, i.e., repeat exposure 2 weeks after lesion has no further effect on the status of the epithelium (Schwob, unpubl. obs.). The ventral epithelium is markedly thinner (by as much as 50% or more) than dorsal epithelium, yet the density of sustentacular cells is fairly comparable across the epithelium, as is the expression of markers of the cytochrome P450 family. Hence, it makes sense that thinner areas are more at risk, since the concentration of MeBr or its toxic intermediates would likely be higher at the basal lamina than in thicker areas.

Nature of the neuroepithelial stem cell

As noted above, several lines of evidence indicate that some GBCs have the capacity to act as MPPs in the context of the MeBr-lesioned epithelium. That some GBCs act as immediate neuronal precursors (INPs), a well-established role for them, is not inconsistent with the additional capacity of other GBCs as MPPs, and does not detract from that assignment. Left unanswered by this formulation is the nature and identity of the stem cell that is ultimately responsible for maintaining the neuroepithelial character of the olfactory epithelium. Part of the intent of the current investigation was to clarify the identity of the neurogenic stem cell by reference to situations when it has presumably been eliminated, i.e., when the epithelium fails to recover as olfactory and undergoes respiratory metaplasia instead.

Of the three cell types suggested by various investigators (on relatively indirect grounds) to be the neurogenic stem cell—GBCs (Caggiano et al., 1994; Huard et al., 1998), HBCs (Mackay-Sim and Kittel, 1991; Satoh and Takeuchi, 1995; Calof et al., 1998), and duct cells (Matulionis, 1975)—the evidence presented here most strongly favors the notion that a form of GBC is the stem cell. First, where a population of GBCs is retained after lesion (i.e., continuously, as in dorsal epithelium, or patchily, as in some areas of ventral epithelium) as we show here by immunostaining and EM examination, the regenerating epithelium becomes neuronal. Second, during the recovery period after MeBr lesion, especially during the early phase (up to 7 days postlesion), HBCs disappear from the ventral and lateral epithelium as a result of lesion, i.e., from ventral areas that will recover and others that will not (Schwob et al., 1995). In other words, neurons (as well as sustentacular cells) reemerge in patches within the ventral “HBC-free” areas. Thus, these data do not support the assignment of stem cell function to the HBCs. Instead, the majority (70–90%) of proliferating cells are GBCs and they account for the massive increase in cell number in the epithelium. Third, gland cells do not seem to act as a neurogenic stem cells because they densely populate precisely those areas of ventral olfactory epithelium that are not recovering. It is formally possible that duct cells located just above the basal lamina might be different in their progenitive capacity from cells located just below it and that such epilaminar cells are selectively absent from areas undergoing metaplasia after injury. However, the lack of positive evidence for a lineage relationship between duct cells and neurons among the large numbers of retrovirus-labeled clones that we analyzed argue against that (Huard et al., 1998).

Gland/duct cells: source for respiratory epithelium?

Our present results show that the survival of the population of GBCs is a prerequisite for complete restoration of the olfactory epithelium after injury. However, the olfactory epithelium is replaced by a tissue closely resembling respiratory epithelium in places where GBCs disappear as a consequence of the lesion, i.e., interspersed throughout the ventral epithelium. From what progenitors) do the respiratory epithelial cells originate? Candidate precursor cells for respiratory epithelium must be capable of mitotic expansion. GBCs, HBCs, duct cells, gland cells, and sustentacular cells satisfy this criterion. Sustentacular cells are not viable candidates since they disappear within hours of MeBr exposure throughout all affected areas of the epithelium (see Results). Horizontal basal cells are also excluded because of their complete absence in the ventral epithelium during early stages of recovery. Indeed, we observed respiratory-like organization by 5 days postlesion when HBCs were still absent, based on staining with BS-I or antibody to epidermal growth factor receptor (data not shown). The Bowman’s duct cells and gland cells remain the only likely possibility. The behavior of duct cells after lesion is quite complicated. Retrovirus lineage tracing and pulse-chase BrdU labeling suggest that duct cells positioned at the basal lamina can give rise to gland cells and sustentacular cells in epithelium that recovers as olfactory. We presume that some, if not all, of the GLA-13(+) cells observed in dorsal epithelium are derived from the duct cells located at the basal lamina, which would be spared in these areas. In contrast, the GLA-13(+) cells that are found in lesioned ventral epithelium are ultrastructurally similar to gland cells, having secretory vesicles in the cytoplasm, and presumably derive by migration from the lamina propria through the basal lamina into the epithelium. Thus, the gland cells become a prime candidate for serving as the precursor for respiratory epithelial cells. The severity of the lesion in these areas might also eliminate the juxtalaminar duct cells as well as the GBCs. Thus, duct cells might have a different intrinsic capacity for differentiation than gland cells, in that duct cells can give rise to sustentacular cells. In that vein, it is worth noting that cells with different progenitor capacity inhabit different niches even though they share a direct lineage relationship (i.e., skin and hair follicle; Taylor et al., 2000; Lavker and Sun, 2000). Alternatively, the fate of duct cells and gland cells may be determined by context; i.e., the preservation of GBCs, or the reemergence of neurons, or both, may be critical in determining the fate of gland-duct derivatives. At present, all of these explanations are necessarily based on indirect evidence. More definitive answers will likely come from studies utilizing selective isolation and transplantation of each cell type to define progenitor capacity, which are currently under way in our lab (Chen et al., 2001).

CONCLUSION

From data presented here, persistence of the GBC population is critical to the regeneration of olfactory sensory neurons after damage by MeBr. The generation of metaplasia in areas that lack GBCs is likely due to the expansion of gland cell population. Our data also have implications for human disease. The decline of olfactory sensitivity that accompanies aging and upper respiratory infection may be due in large part to the replacement of olfactory epithelium by respiratory epithelium in a manner analogous to what we observed after severe lesion. It is also possible that senescence in the progenitor population may contribute to clinical dysfunction. In either case, the putative assignment of stem cell function to GBCs on the basis of the data presented here suggests that the persistence of functioning GBCs is critical for maintaining function in either context. The present results also have implications for therapeutic intervention in humans. From these data, strategies for maintaining function after injury should focus on replacing and/or sustaining the GBC population. Understanding how cell types in the olfactory epithelium respond to injury and the contextual influence of each cell type on the whole (as a variable manifestation of the severity of the initial damage) will greatly enhance our chance to accomplish olfactory reconstitution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Renee Mezza and Masako Nakatsa-gawa for their excellent technical assistance.

Grant sponsor: the National Institute of Health/ National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; Grant number: R01 DC02167.

LITERATURE CITED

- Caggiano M, Kauer JS, Hunter DD. Globose basal cells are neuronal progenitors in the olfactory epithelium: a lineage analysis using a replication-incompetent retrovirus. Neuron. 1994;13:339–352. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calof AL, Chikaraishi DM. Analysis of neurogenesis in a mammalian neuroepithelium: proliferation and differentiation of an olfactory neuron precursor in vitro. Neuron. 1989;3:115–127. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancalon P. Degeneration and regeneration of olfactory cells induced by ZnSO4 and other chemicals. Tissue Cell. 1982;14:717–733. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(82)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancalon P. Influence of a detergent on the catfish olfactory mucosa. Tissue Cell. 1983;15:245–258. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(83)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PC, Eustis SL, Huff JE, Haseman JK, Ragan H. Two-year inhalation carcinogenesis studies of methyl methacrylate in rats and mice: inflammation and degeneration of nasal epithelium. Toxicology. 1988;52:237–252. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(88)90129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Murrell JR, Hunter DD, Schwob JE. Limits and potential of basal cell transplantation. Chem Senses. 2001;26:1055. [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo RM. Comparison of neurogenesis and cell replacement in the hamster olfactory system with and without a target (olfactory bulb) Brain Res. 1984;307:295–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo RM. Regeneration of olfactory receptor cells. Ciba Found Symposium. 1991;160:233–242. doi: 10.1002/9780470514122.ch12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo RM, Graziadei PP. A quantitative analysis of changes in the olfactory epithelium following bulbectomy in hamster. J Comp Neurol. 1983;215:370–381. doi: 10.1002/cne.902150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douek E, Bannister LH, Dodson HC. Recent advances in the pathology of olfaction. Proc R Soc Med. 1975;68:467–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BJ, Schwob JE. Analysis of the globose basal cell compartment in rat olfactory epithelium using GBC-1, a new monoclonal antibody against globose basal cells. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4005–4016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-04005.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BJ, Wolozin BL, Schwob JE. FGF2 suppresses neuronogenesis of a cell line derived from rat olfactory epithelium. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:411–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BJ, Fang H, Youngentob SL, Schwob JE. Transplantation of multipotent progenitors from the adult olfactory epithelium. Neuro-Report. 1998;9:1611–1617. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziadei PP, Monti Graziadei GA. Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. I. Morphological aspects of differentiation and structural organization of the olfactory sensory neurons. J Neurocytol. 1979;8:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01206454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JW, Getchell TV, Margolis FL. Denervation of the primary olfactory pathway in mice. V. Long-term effect of intranasal ZnSO4 irrigation on behavior, biochemistry and morphology. Brain Res. 1978;140:271–285. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings L, Miller ML, Minnema DJ, Evans JE, Radike M. Effects of methyl bromide on the rat olfactory system. Chem Senses. 1991;16:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook EH, Szumowski KE, Schwob JE. An immunochemical, ultrastructural, and developmental characterization of the horizontal basal cells of rat olfactory epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:129–146. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard JM, Youngentob SL, Goldstein BJ, Luskin MB, Schwob JE. Adult olfactory epithelium contains multipotent progenitors that give rise to neurons and non-neural cells. J Comp Neurol. 1998;400:469–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtt ME, Thomas DA, Working PK, Monticello TM, Morgan KT. Degeneration and regeneration of the olfactory epithelium following inhalation exposure to methyl bromide: pathology, cell kinetics, and olfactory function. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1988;94:311–328. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(88)90273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavker RM, Sun TT. Epidermal stem cells: properties, markers, and location. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13473–13475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250380097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay-Sim A, Kittel P. Cell dynamics in the adult mouse olfactory epithelium: a quantitative autoradiographic study. J Neurosci. 1991;11:979–984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00979.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulionis DH. Ultrastructural study of mouse olfactory epithelium following destruction by ZnSO4 and its subsequent regeneration. Am J Anat. 1975;142:67–90. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001420106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti Graziadei GA, Graziadei PP. Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. II. Degeneration and reconstitution of the olfactory sensory neurons after axotomy. J Neurocytol. 1979;8:197–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01175561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti Graziadei GA, Margolis FL, Harding JW, Graziadei PP. Immunocytochemistry of the olfactory marker protein. J Histochem Cyotochem. 1977;25:1311–1316. doi: 10.1177/25.12.336785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody SA, Quigg MS, Frankfurter A. Development of the peripheral trigeminal system in the chick revealed by an isotype-specific anti-beta-tubulin monoclonal antibody. J Comp Neurol. 1989;279:567–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.902790406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumm JS, Shou J, Calof AL. Colony-forming progenitors from mouse olfactory epithelium: evidence for feedback regulation of neuron production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11167–11172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima T, Kimmelman CP, Snow JB. Structure of human fetal and adult olfactory epithelium. Acta Oto Laryngol. 1984;110:641–646. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1984.00800360013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik SI, Lehman MN, Seiden AM, Duncan HJ, Smith DV. Human olfactory biopsy. The influence of age and receptor distribution. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:731–738. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880070061012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peele DB, Allison SD, Bolon B, Prah JD, Jensen KF, Morgan KT. Functional deficits produced by 3-methylindole-induced olfactory mu-cosal damage revealed by a simple olfactory learning task. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1991;107:191–202. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90202-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley SK. Purified cultures of keratin-positive olfactory epithelial cells: identification of a subset as neuronal supporting (sustentacular) cells. J Neurosci Res. 1992;31:693–707. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490310413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, Takeuchi M. Induction of NCAM expression in mouse olfactory keratin-positive basal cells in vitro. Dev Brain Res. 1995;87:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00057-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Levey M, Chikaraishi DM, Kauer JS. Characterization of potential precursor populations in the mouse olfactory epithelium using immunocytochemistry and autoradiography. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3556–3564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03556.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob JE, Szumowski KE, Stasky AA. Olfactory sensory neurons are trophically dependent on the olfactory bulb for their prolonged survival. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3896–3919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03896.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob JE, Youngentob SL, Mezza RC. Reconstitution of the rat olfactory epithelium after methyl bromide-induced lesion. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:15–37. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons PA, Rafols JA, Getchell TV. Ultrastructural changes in olfactory receptor neurons following olfactory nerve section. J Comp Neurol. 1981;197:237–257. doi: 10.1002/cne.901970206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G, Lehrer MS, Jensen PJ, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Involvement of follicular stem cells in forming not only the follicle but also the epidermis. Cell. 2000;102:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaagen J, Oestreicher AB, Grillo M, Khew-Goodall YS, Gispen WH, Margolis FL. Neuroplasticity in the olfactory system: differential effects of central and peripheral lesions of the primary olfactory pathway on the expression of B-50/GAP43 and the olfactory marker protein. J Neurosci Res. 1990;26:31–44. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490260105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]