Abstract

Generalist species and phenotypes are expected to perform best under rapid environmental change. In contrast to this view that generalists will inherit the Earth, we find that increased use of a single host plant is associated with the recent climate-driven range expansion of the UK brown argus butterfly. Field assays of female host plant preference across the UK reveal a diversity of adaptations to host plants in long-established parts of the range, whereas butterflies in recently colonized areas are more specialized, consistently preferring to lay eggs on one host plant species that is geographically widespread throughout the region of expansion, despite being locally rare. By common-garden rearing of females’ offspring, we also show an increase in dispersal propensity associated with the colonization of new sites. Range expansion is therefore associated with an increase in the spatial scale of adaptation as dispersive specialists selectively spread into new regions. Major restructuring of patterns of local adaptation is likely to occur across many taxa with climate change, as lineages suited to regional colonization rather than local success emerge and expand.

Keywords: range expansion, climate change, environmental change, host plant preference, local adaptation, butterfly

1. Introduction

The potential for the rapid evolution of ecological traits demanded by climate-driven range expansion remains unclear [1–5]. In particular, the adaptation of existing populations to local conditions will reduce their ability to colonize new geographical regions if their hosts are rare or patchily distributed in new regions [3,6,7]. This means that unless shifts in the geographical position of thermally suitable habitat are matched by corresponding shifts in specific food sources, prey or symbionts, specialization on local resources could condemn species to extinction [8,9]. Generalist species are therefore expected to expand their ranges most readily [7], whereas specialist species may need to evolve more generalist phenotypes in order to overcome ecological barriers to dispersal [1,3,10,11]. At the same time, although local specialization may slow spread at ecological margins, local adaptation across a species’ range provides genetic diversity from which successful colonizing phenotypes could be selected. Such geographical variation is determined by divergent selection and gene flow among populations [12–14], and by the balance of local extinction and colonization within a metapopulation network [15–17].

Range expansion generally favours the evolution of increased rates of dispersal [1,3,10,18], and the use of resources that are widespread across the landscapes into which range expansion occurs [3,19]. Host preference is a key driver of habitat use in phytophagous insects such as butterflies, and there is strong evidence both for a heritable component to host plant preference [1,20–22] as well as for its rapid evolution [23]. Range expansion should therefore involve the spread of generalist phenotypes, which will, in turn, cause a shift in population ecology from local- to regional-scale adaptation in the new parts of the range. Once new sites are colonized, and range expansion slowed, selection may again favour adaptations to the locally most abundant or profitable host, and reduced dispersal rates [10,18,24]. However, the loss of genetic diversity during range expansions may limit the capacity for local adaptation in recently colonized regions, particularly where this loss is driven by selective sweeps as well as genetic drift [25].

The brown argus butterfly, Aricia agestis (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae), has expanded its geographical range in the UK over the past 25 years in response to climate warming [26,27]. Distinct populations of its different host plant species are found throughout its range. Across the long-established range in southern England, the brown argus is common on chalk grassland habitats characterized by high densities of the host plant, Helianthemum nummularium (Cistaceae, also known as Helianthemum chamaecistus), but also on a diverse range of other habitats (e.g. sand dunes, heathlands and grasslands on disturbed ground), where host plants in the Geraniaceae family, mainly Geranium molle, Geranium dissectum and Erodium cicutarium, are found.

We first consider levels of specialization in egg-laying behaviour on these four different plant species at different local populations of A. agestis, within the long-established range. All of these host plants also occur in the recently colonized range, but H. nummularium is far more localized, and is almost entirely absent from the region immediately north of the historical distribution [28]. This means that selection for increased use of Geraniaceae species (and reduced use of H. nummularium) may have been necessary to allow the northward spread of the brown argus butterfly [1,14,26]. In this study, we test this suggestion empirically in more detail, by assaying variation in host preference behaviour and dispersal-related morphology throughout the species’ UK range.

2. Material and methods

(a). Geographical variation in host plant abundance

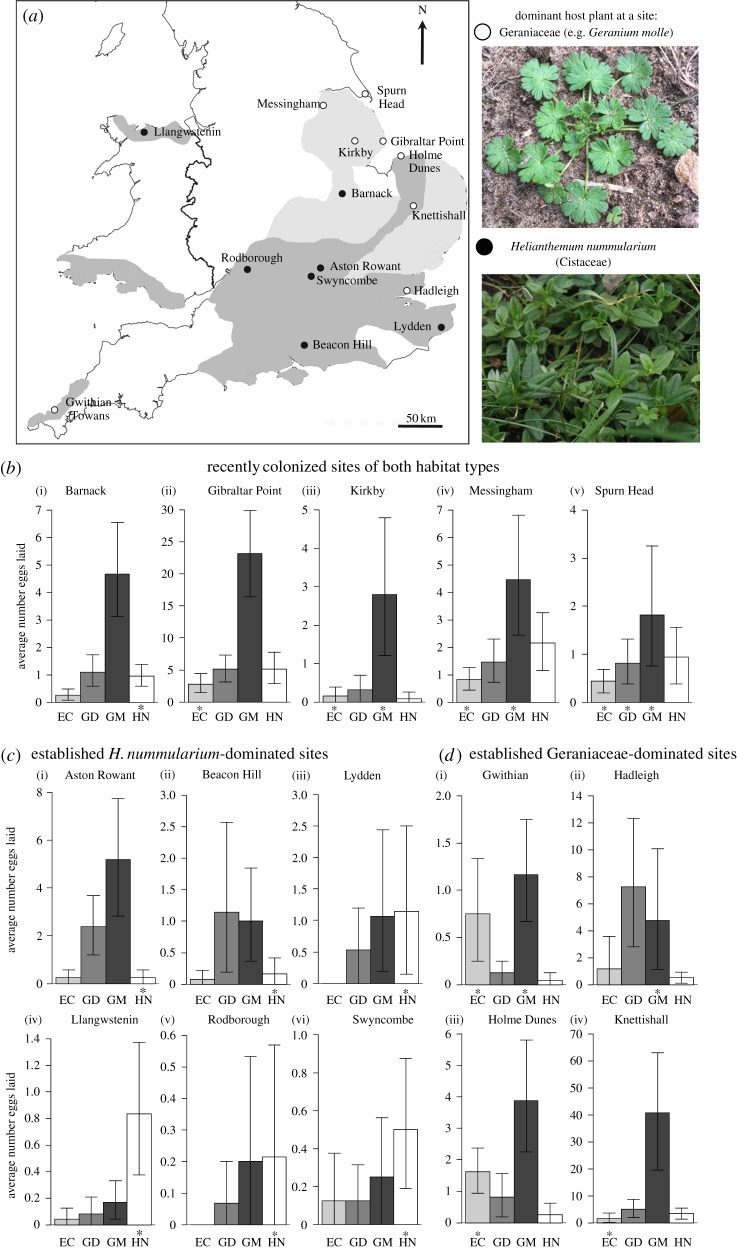

Fifteen sites across the UK distribution of A. agestis were selected to represent all combinations of sites with respect to habitat type and colonization history (figure 1a and the electronic supplementary material, table S1). The dominant host plant at each site was determined using records of host plant presence in 2000/2001, and vegetation surveys conducted in 2004/2005. For the vegetation surveys, 20 quadrats were placed randomly at each site in each habitat type known to be frequented by A. agestis, and the percentage cover estimated for its four UK host plants, G. molle, G. dissectum, E. cicutarium and H. nummularium. These classifications were unchanged in subsequent surveys in 2007–2011.

Figure 1.

(a) Geographical location of study sites (for site names and descriptions, see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). The darker grey shading denotes long-established parts of the range of A. agestis (recorded presence since 1970–1982; [27]) and lighter grey shading indicates more recently colonized areas (A. agestis only present since 1995–1999). The filled circles indicate H. nummularium-dominated habitats and open circles indicate Geraniaceae-dominated habitats. Photos provide examples of the two groups of host plants that are dominant in the two main habitat types present across the range. (b–d) Average eggs laid per host plant at each site with 95% confidence intervals estimated through bootstrapping with 10 000 randomizations (the electronic supplementary material, table S3 gives sample sizes). The x-axis displays the four host plants: EC, Erodium cicutarium; GD, Geranium dissectum; GM, Geranium molle; HN, Helianthemum nummularium. The y-axis, average eggs laid per host plant, varies in scale. Asterisk above a host plant code indicates that it is a dominant host plant at the site (For Spurn Head, the host plants present are indicated, as the dominant host species is unknown). (Online version in colour.)

(b). Geographical variation in site host preference

Site host preference was measured by estimating the average number of eggs laid by free-flying females on greenhouse-grown host plants (G. molle, G. dissectum, E. cicutarium and H. nummularium) at each of the 15 study sites (figure 1a). Host preference assays were conducted during the second brood (late-July to early-September) in 2000, 2001 and 2004 (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3), and were repeated at three sites across 2 years. There was no significant effect of year on site-level preference estimates at these three sites (see the electronic supplementary material, table S2), so host preference data were pooled across years for subsequent analyses.

For each sampling year, individual potted host plants of the four host plant species were grown to an equivalent size from a single (UK) commercial source of seeds or plugs in a common greenhouse environment. A host plant of each species was placed in a randomized position in each corner of a 0.5 × 0.5 m quartet, with 16–24 such quartets placed randomly across the study site. The plants were left in situ for 7–21 days. The eggs laid on each surviving host plant by free-flying females at a site were then counted. Eggs typically take approximately one week to hatch in the field, so the numbers on the host plants reflect the rate of recent egg-laying on each host plant. Preferences for different host species at a site were estimated using the average number of eggs laid per individual plant of each host species. The number of eggs laid on each individual host plant was resampled 10 000 times (with replacement) for each host species at a site to produce bootstrap 95% confidence limits for the average number of eggs per host species (figure 1b–d). The number of eggs laid on each individual plant was used as the response variable in a generalized linear model (GLM) with negative binomial error (for overdispersed count data) implemented in the MASS R package [29]. To test for an association between host preference and habitat type, the model used percentage H. nummularium preference (as estimated above) as the response variable, with habitat type as the explanatory variable, weighted by the total number of eggs laid on host plants at a site. The difference in predicted mean H. nummularium preference for the different habitat types was estimated. To test the significance of an observed difference, we re-estimated this difference following a permutation of sites among the two habitat types and repeated this 10 000 times to produce a distribution of simulated differences. A p-value represents the proportion of simulated differences greater than the observed difference. All statistical analyses were conducted with R statistical software [30], unless otherwise specified. Likelihood-ratio tests were used to test for a significant change in the log-likelihood of a model on removal of each model term.

(c). Comparison of variance in host preference among sites of differing colonization history

Variance components analyses were used to estimate the proportion of among- and within-site variance in host preference for all long-established sites and all recently colonized sites separately. To estimate within-site variation in host preference, the quartets of host plant at a site on which eggs were laid (ranging from five to 33 quartets at different sites) were treated as independent assays of host preference within a site. Preference for H. nummularium or G. molle was estimated as the number of eggs laid on that plant in a quartet relative to the number of eggs laid on the three Geraniaceae host plants (or remaining two Geraniaceae host plants) in the quartet.

A generalized linear-mixed effects model with binomial error (‘lme4’ R package [31]) was fitted to these data, including the random effects of variation among sites and the variation among host plant quartets within each site. The proportion of variance among sites relative to total variance (among-site variance/(among-site + within-site variance)) in host preference was then estimated for the long-established sites and recently colonized sites separately. The difference between established and recently colonized sites in the proportion of among-site variance in preference for H. nummularium was calculated, and the significance of this difference tested with permutations at the level of site using the R package ‘permute’ [32]. The permutation design randomly allocated five study sites to a recently colonized group and 10 to a long-established group, whereas within-site structure in quartet-level host preference estimates remained as measured. The difference between recently colonized and long-established sites in the proportion of among-site variance in host preference was then re-estimated. This difference was calculated for 10 000 permutations of study sites among the two colonization history classifications; the p-value represents the proportion of simulated differences that are greater than the observed difference.

(d). Morphometric analysis of dispersal ability

Thirty-seven females from five sites (Barnack, Holme Dunes, Swyncombe, Kirkby and Rodborough) were collected in the summer of 2009 and placed individually under cages to oviposit on natural patches of host plants at their home site. The eggs laid were then reared to adult at 20°C on a 16 : 8 h day : light cycle to estimate genetic differentiation in relative thorax mass and forewing size. Heritable variation in these traits, as well as an association with flight (dispersal) ability has been demonstrated in several other butterfly species (e.g. Pararge aegeria: [33,34]). Eggs from different sites were reared in two batches. Eggs were reared individually in 55 mm Petri dishes with moistened filter paper and fresh greenhouse-grown G. molle leaf. Within 24 h of emergence, adults were sexed and killed by freezing at −20°C. Sample size varied from one to 21 individuals per family (median = 4). Abdomen and thoraxes were then dissected out and dried to constant mass at 65°C, and weighed using a Sartorius ME 5 microbalance (sensitivity ± 1 µg). Wings were mounted on glass slides using isopropanol and Aquatex aqueous mounting agent and photographed (McCamera, moticam 16 mm). Forewing area was estimated using tpsUtil and tpsDig, based on the square root of the sum of squared distances of a set of 14 landmarks from their centroid (http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/). Measurements were highly repeatable for thorax and abdomen mass (0.20% measurement error, n = 95) and forewing size (0.47% error, n = 10). Variation in male or female forewing area and thorax mass, averaged within families, was tested using a linear-mixed effects model, with site colonization history as a fixed factor, total mass as a covariate and site of maternal origin as a random effect. By using total mass as a covariate in the analyses of flight morphology, we also account for any variation in body mass that may result from differential maternal investment in offspring. Differences among sites of different habitat type, the two rearing batches (‘batch’ effect) and the study sites (within each rearing batch) were tested by replacing ‘site colonization history’ with each of these fixed effect factors in turn.

3. Results

(a). Geographical variation in host plant abundance

Helianthemum nummularium was the dominant host plant at all chalk grassland sites, whereas plants in the Geraniaceae were the only potential hosts present in other habitat types used by A. agestis (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). Helianthemum nummularium cover in quadrats averaged 28.8% (range = 11.0–46.6%) across the seven chalk grassland sites surveyed, with Geraniaceae host species found in only 1 out of 140 quadrats. By contrast, H. nummularium was never recorded in non-chalk habitats, and the average host cover of G. molle and E. cicutarium combined was 5.8% (range = 1.0–10.7%), with G. dissectum not found in any vegetation quadrats. Sites were therefore divided into ‘H. nummularium-dominated sites’ and ‘Geraniaceae-dominated sites’ for analysis (figure 1).

(b). Geographical variation in host plant preference

(i). Long-established sites

Significant variation in site-level host preference was observed among the 10 long-established sites (likelihood-ratio (LR) statistic = 92.1, d.f. = 27, chi-squared test: p < 0.0001; figure 1c,d), with preferences generally matching the locally dominant host plant (figure 1c versus 1d). The four long-established Geraniaceae-dominated sites varied significantly in the preferred species of Geraniaceae (LR = 24.31, d.f. = 9, p = 0.004; figure 1d), with consistently low preferences for the locally absent H. nummularium (2.0–6.6%; figure 1d) and increased preference for E. cicutarium at dune habitats (Gwithian and Holme Dunes; electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S3) where it is more locally common. There was also significant variation in host preference among the six long-established H. nummularium-dominated sites (LR = 34.98, d.f. = 15, p = 0.003; figure 1c), with H. nummularium preferences greater than 40% at four sites, although G. molle and G. dissectum were preferred at two sites. The percentage of eggs laid on H. nummularium in long-established H. nummularium-dominated sites was significantly greater than in long-established Geraniaceae-dominated sites (H. nummularium sites = 20.7%; Geraniaceae sites = 5.6%; p = 0.02, when tested with 10 000 permutations of the site-level preference estimates among the two habitat types.

(ii). Recently colonized sites

The significant variation in preference profile observed among long-established sites of both habitat types was not observed across recently colonized study sites (figure 1b; LR = 13.84, d.f. = 12, p = 0.311). Despite substantial variation in the locally dominant host plant at these five sites (including a H. nummularium- and E. cicutarium-dominated site), there was a consistently strong preference for G. molle at all sites.

(c). Comparison of variance in host preference among sites of differing colonization history

Among-site variance for H. nummularium preference was 4.4 times lower at recently colonized sites than at long-established sites, an effect that was marginally significant, even given the small number of sites considered (p = 0.095; table 1). There was also a 1.9 times reduction in among-site variance for G. molle-preference at recently colonized sites although this difference was far less significant (p = 0.722; table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage variance in host preference estimates attributed to among-site effects as estimated by variance components analysis for all long-established sites and all recently colonized sites separately. (Est., established sites; RC, recently colonized sites (since 1990). The significance of a difference in among-site variance of this magnitude when tested using permutations (see main text description) is given (‘p’).)

| no. sites (est., RC) | median no. quartets per site (min.-max.) | % variance attributed to among-site effects |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| established sites | recently colonized sites | ||||

| H. nummularium preference | 10, 5 | 10 (6–33) | 69.2 | 15.7 | 0.095 |

| G. molle preference | 9, 5 | 10.5 (5–31) | 24.9 | 12.9 | 0.722 |

(d). Morphological analysis of dispersal ability

Relative thorax sizes were significantly larger for females originating from recently colonized sites than from long-established populations (table 2a; p = 0.004), suggesting stronger flight ability in individuals from recently colonized sites. Males showed a similar, but non-significant trend (table 2b; p = 0.134). Habitat type of origin did not affect relative thorax mass (table 2; p = 0.905 in all cases). Forewing size, controlling for total mass, was not significantly correlated with colonization history or the host plant present (table 2; p > 0.535 in all cases). Habitat of origin and site colonization history also had no effect on average development time on G. molle (table 2). Within each rearing batch, progeny from all sites developed equally successfully on G. molle leaf (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S4 and S5a,b), and relative thorax mass was still greater in recently colonized sites (see the electronic supplementary material, table S5a).

Table 2.

Variation in family mean estimates of days to adult emergence and two measures of flight morphology (thorax mass and forewing size) for (a) females and (b) males reared in a common environment from eggs collected from sites differing in colonization history (long-established and recently colonized) and habitat type: Helianthemum nummularium-dominated, or Geraniaceae-dominated. (Mean relative thorax mass and relative forewing size represents the means of residuals of a regression between thorax mass and total mass (or forewing size and total mass). Standard errors (s.e.) and sample sizes (number of families, n) of these flight morphology measures are also given. Statistics were produced by a combination of linear-mixed models to control for site variation or a linear model with covariates including total mass to control for variation in body size. Significance of factor: **p = 0.004, with all other comparisons not significant (p > 0.134).

| category | factor levels | n | days to emergence |

relative thorax mass |

relative forewing size |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | s.e. | mean | s.e. | mean | s.e. | |||

| (a) females | ||||||||

| colonization history | established | 23 | 53.0 | 0.5 | −0.042** | 0.02 | −1.00 | 6.29 |

| recent | 12 | 52.9 | 0.9 | 0.080** | 0.04 | 2.10 | 20.44 | |

| habitat type | H. nummularium | 18 | 53.0 | 0.6 | −0.004 | 0.03 | 1.19 | 9.97 |

| Geraniaceae | 16 | 52.9 | 0.6 | 0.004 | 0.03 | −1.34 | 12.17 | |

| (b) males | ||||||||

| colonization history | established | 22 | 50.1 | 0.7 | −0.036 | 0.05 | −1.99 | 12.23 |

| recent | 11 | 49.4 | 0.6 | 0.071 | 0.03 | 3.99 | 14.55 | |

| habitat type | H. nummularium | 18 | 49.6 | 0.5 | −0.027 | 0.06 | −4.76 | 9.45 |

| Geraniaceae | 15 | 50.3 | 0.0 | 0.032 | 0.04 | 5.72 | 17.51 | |

4. Discussion

The recent range expansion of A. agestis is associated with increased temperatures at its range margins, and has involved butterflies colonizing landscapes where Geraniaceae host plants, particularly G. molle, are widespread, and H. nummularium habitat is rare [26]. We assayed host preference at 15 sites throughout the UK range of A. agestis, to test in detail the prediction, first proposed in Thomas et al. [1], that host preference evolution has facilitated the range expansion of the brown argus butterfly. Our data confirm a shift from locally adapted patterns of host plant use in long-established areas, to host preference profiles that consistently favour G. molle in recently colonized locations, even if not associated with local habitat type or host plant availability. Rearing of larvae collected from sites in a common environment also suggests the evolution of increased female flight capacity associated with range expansion. These data, combined with molecular genetic analysis [14], indicate that climate change adaptation in this species has involved the rapid evolution of key ecological traits, involving the selective spread of genotypes that prefer the most geographically widespread host plant throughout the region of expansion, and have higher dispersal ability. This observation mirrors the success of invasive species that are adapted to widespread rather than localized resources [35].

We identified significant divergence in site-level host plant preference across the long-established part of the UK distribution (figure 1c,d), with preference profiles typically matching the most locally abundant host plant. Four of the six chalk grassland sites showed strong preferences for the dominant species H. nummularium (ranging from 41.7% to 74.1%; figure 1c and the electronic supplementary material, table S3). Evidence for local adaptation was also observed at the four long-established Geraniaceae-dominated study sites: the two sites with the highest percentage preference for E. cicutarium were coastal dune grasslands where E. cicutarium is locally abundant (figure 1d(i,iii) and the electronic supplementary material, table S3), and preference for laying eggs on the locally absent H. nummularium was correspondingly low (ranging from 2.2% to 6.6%; figure 1d and the electronic supplementary material, table S3).

Variation in preference among sites in the long-established part of the range, particularly in preference for H. nummularium, is greatly reduced in areas colonized during the recent range expansion (table 1). Across sites in the recently colonized parts of the range, consistent patterns of preference are observed for all four host plant species, with the majority of eggs laid on G. molle (figure 1b), irrespective of the locally abundant host plant (e.g. at Barnack and Gibraltar Point). Use of G. molle preference was also consistently observed at established sites (lower than 25% at only one established site), and was the most preferred host at two long-established H. nummularium-dominated sites. The ability to use G. molle as a host is therefore widespread in the established part of the range, even at chalk grassland sites where G. molle is locally rare. This observation supports evidence that selection on standing genetic variation between long-established populations is associated with the loss of host preference variation during the colonization of new habitats [14].

In many organisms, the use of a wide range of resources is traded off with reduced ability to use any single resource [36]. The persistent tendency of females to use G. molle at long-established H. nummularium sites may reflect a host on which all larvae develop successfully (at least during warm summers—we observed no differences in development time or larval survival in our rearing experiments; electronic supplementary material, table S4), an adaptation to a resource with a widespread distribution, or the continual influx of females adapted to G. molle from the surrounding landscape [14]. In the Glanville fritillary butterfly (Melitaea cinxia) variation in host preference is associated with local host abundance, but also with host preference in and connectivity to surrounding patches [16,19]. Similarly, in A. agestis in north Wales, gene flow and population turnover result in local voltinism profiles adapted to climatic conditions across the population network as a whole, rather than those expected given the local microclimate [37].

In contrast to G. molle, H. nummularium is locally abundant but geographically localized [28], so its use should increase fitness only when individuals remain in a H. nummularium-dominated habitat, but not when dispersing to new locations, or crossing areas where the spatial distribution of this host is highly fragmented. Bodsworth [38] showed that females reared from eggs collected from a long-established, G. molle-preferring site move between host plant patches ca 20% faster on average than females reared from eggs collected from a long-established, H. nummularium-preferring site [38]. Higher movement rates are also expected where host plant densities are low and searching behaviour is the priority: females of the butterfly Euphydryas editha are more likely to leave a habitat patch if their preferred host plant is rare or absent [39]. This association between G. molle preference and faster movement, in addition to the broader distribution of G. molle, would lead to spread at the species’ margin being dominated by G. molle-preferring genotypes.

Laboratory-reared A. agestis females from recently colonized sites also have significantly greater relative thorax mass compared with those from long-established sites (table 2). These differences in thorax investment are not related to significant differences in survival or total mass, making it unlikely that they reflect between site differences in maternal investment or condition (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S4 and S5). Although we report no direct association between flight morphology and dispersal ability here, in the speckled wood butterfly, P. aegeria, relative thorax mass shows heritable variation [34] and is associated with increased flight acceleration capacity [33]. The significant increase in flight capacity observed for females, but not males, has been observed in other studies [40,41]. Generally, males defend particular locations within a site to find females, whereas females disperse, sometimes over larger distances, to find suitable patches of host plant on which to lay their eggs.

Predicting when and how range shifts will allow populations to track climate change is important for identifying those species most at risk of extinction [8,9], as well as for designing potential mitigation strategies [42]. This study underlines that understanding the evolutionary responses that will underlie range expansion in many species is crucial [2–4,11]. In addition, our data demonstrate a reduction in host preference variation associated with range expansion of A. agestis, and adaptation to the regional availability of hosts rather than their local abundance. This loss of standing genetic variation associated with rapid evolution may reduce responses to new selection pressures and prevent further range expansion into new biotic environments [25]. In this case, reduced capacity to use H. nummularium looks likely to slow the expansion of A. agestis across H. nummularium habitats in north Yorkshire as the climate continues to warm. Maintaining genetic variation in key ecological traits by population translocation or assisted migration may therefore be crucial for sustaining, as well as generating, responses to climate change in many species throughout the twenty-first century [5].

Acknowledgements

We thank the numerous research assistants who helped collect the field data and rear caterpillar larvae. We are very grateful to managers and landowners who gave permission to work on their land, and in particular Natural England, the National Trust and the Lincolnshire, Kent and Norfolk wildlife trusts. We also thank Roger Butlin (University of Sheffield), Jane Hill (University of York) and two anonymous reviewers for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Data accessibility

Data available from the dryad digital repository: http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.8261b.

Funding statement

This work was supported by an NERC New Investigators grant to J.R.B., an NERC studentship to J.B. and a University of Leeds studentship to E.J.B.

References

- 1.Thomas CD, Bodsworth EJ, Wilson RJ, Simmons AD, Davies ZG, Musche M, Conradt L. 2001. Ecological and evolutionary processes at expanding range margins. Nature 411, 577–581 (doi:10.1038/35079066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridle JR, Vines T. 2007. Limits to adaptation at range margins: when and why does adaptation fail? Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 140–147 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill JK, Griffiths HM, Thomas CD. 2011. Climate change and evolutionary adaptations at species’ range margins. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 143–159 (doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144746) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann AA, Sgro CM. 2011. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485 (doi:10.1038/nature09670) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duputié A, Massol F, Chuine I, Kirkpatrick M, Ronce O. 2012. How do genetic correlations affect species range shifts in a changing environment? Ecol. Lett. 15, 251–259 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01734.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill JK, Collingham YC, Thomas CD, Blakeley DS, Fox R, Moss D, Huntley B. 2001. Impacts of landscape structure on butterfly range expansion. Ecol. Lett. 4, 313–321 (doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00222.x) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren MS, et al. 2001. Rapid responses of British butterflies to opposing forces of climate and habitat change. Nature 414, 65–69 (doi:10.1038/35102054) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas CD, et al. 2004. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427, 145–148 (doi:10.1038/nature02121) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maclean IMD, Wilson RJ. 2011. Recent ecological responses to climate change support predictions of high extinction risk. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12 337–12 342 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1017352108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feder ME, Garland T, Marden JH, Zera AJ. 2010. Locomotion in response to shifting climate zones: not so fast. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72, 167–190 (doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135804) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavergne S, Mouquet N, Thuiller W, Ronce O. 2010. Biodiversity and climate change: integrating evolutionary and ecological responses of species and communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 41, 321–350 (doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102209-144628) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slatkin M. 1987. Gene flow and the geographic structure of natural populations. Science 236, 787–792 (doi:10.1126/science.3576198) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer MC, Thomas CD. 1996. Evolutionary responses of a butterfly metapopulation to human- and climate-caused environmental variation. Am. Nat. 148, S9–S39 (doi:10.1086/285900) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckley J, Butlin RK, Bridle JR. 2012. Evidence for evolutionary change associated with the recent range expansion of the British butterfly, Aricia agestis, in response to climate change. Mol. Ecol. 21, 267–280 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05388.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas CD, Singer MC, Boughton DA. 1996. Catastrophic extinction of population sources in a butterfly metapopulation. Am. Nat. 148, 957–975 (doi:10.1086/285966) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanski I, Singer MC. 2001. Extinction-colonization dynamics and host-plant choice in butterfly metapopulations. Am. Nat. 158, 341–353 (doi:10.1086/321985) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanski I, Mononen T. 2011. Eco-evolutionary dynamics of dispersal in spatially heterogeneous environments. Ecol. Lett. 14, 1025–1034 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01671.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simmons AD, Thomas CD. 2004. Changes in dispersal during species’ range expansions. Am. Nat. 164, 378–395 (doi:10.1086/423430) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuussaari M, Singer M, Hanski I. 2000. Local specialization and landscape-level influence on host use in an herbivorous insect. Ecology 81, 2177–2187 (doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2177:LSALLI]2.0.CO;2) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson JN. 1988. Evolutionary genetics of oviposition preference in swallowtail butterflies. Evolution 42, 1223–1234 (doi:10.2307/2409006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nylin S, Nygren GH, Windig JJ, Janz N, Bergstrom A. 2005. Genetics of host-plant preference in the comma butterfly Polygonia c-album (Nymphalidae), and evolutionary implications. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 84, 755–765 (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00433.x) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klemme I, Hanski I. 2009. Heritability of and strong single gene (Pgi) effects on life-history traits in the Glanville fritillary butterfly. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 1944–1953 (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01807.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer MC, Thomas CD, Parmesan C. 1993. Rapid human-induced evolution of insect host associations. Nature 366, 681–683 (doi:10.1038/366681a0) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanski I. 2011. Eco-evolutionary spatial dynamics in the Glanville fritillary butterfly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14 397–14 404 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1110020108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pujol B, Pannell JR. 2008. Reduced responses to selection after species range expansion. Science 321, 96 (doi:10.1126/science.1157570) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pateman RM, Hill JK, Roy DB, Fox R, Thomas CD. 2012. Temperature-dependent alterations in host use drive rapid range expansions in a butterfly. Science 336, 1028–1030 (doi:10.1126/science.1216980) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asher J, et al. 2001. The millennium atlas of butterflies in Britain and Ireland. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stace C. 1997. New flora of the British Isles, 2nd edn Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venables WN, Ripley BD. 2002. Modern applied statistics with S, 4th edn New York, NY: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Development Core Team 2009. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; See http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B.2011. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999375–42. See http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4 .

- 32.Simpson GL.2012. permute: functions for generating restricted permutations of data. R package version 0.7–0. See http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=permute .

- 33.Berwaerts K, Van Dyck H, Aerts P. 2002. Does flight morphology relate to flight performance? An experimental test with the butterfly Pararge aegeria. Funct. Ecol. 16, 484–491 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00650.x) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berwaerts K, Matthysen E, Van Dyck H. 2008. Take-off flight performance in the butterfly, Pararge aegeria, relative to sex and morphology: a quantitative genetic assessment. Evolution 62, 2525–2533 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00456.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hufbauer RA, Facon B, Ravigné V, Turgeon J, Foucaud J, Lee CE, Rey O, Estoup A. 2011. Anthropogenically induced adaptation to invade (AIAI): contemporary adaptation to human-altered habitats within the native range can promote invasions. Evol. Appl. 5, 89–101 (doi:10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00211.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gripenberg S, Mayhew PJ, Parnell M, Roslin T. 2010. A meta-analysis of preference-performance relationships in phytophagous insects. Ecol. Lett. 13, 383–393 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01433.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wynne IR, Wilson RJ, Burke AS, Simpson F, Pullin AS, Thomas CD, Mallet J. 2003. The effect of metapopulation processes on the spatial scale of adaptation in Aricia butterflies across an environmental gradient. UCL Eprints no. 19259. See http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/19259/1/19259.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bodsworth E. 2002. Dispersal and behaviour of butterflies in response to their habitat. Leeds, UK: University of Leeds [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas CD, Singer M. 1987. Variation in host preference affects movement patterns within a butterfly population. Ecology 68, 1262–1267 (doi:10.2307/1939210) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanski I, Eralahti C, Kankare M, Ovaskainen O, Siren H. 2004. Variation in migration propensity among individuals maintained by landscape structure. Ecol. Lett. 7, 958–966 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00654.x) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niitepold K, Mattila ALK, Harrison PJ, Hanski I. 2011. Flight metabolic rate has contrasting effects on dispersal in the two sexes of the Glanville fritillary butterfly. Oecologia 165, 847–854 (doi:10.1007/s00442-010-1886-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopkins JJ, Allison H, Walmsley C, Gaywood M, Thurgate G. 2007. Biodiversity conservation and climate change: guidance on building capacity to adapt. London, UK: DEFRA [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the dryad digital repository: http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.8261b.