Abstract

An infant-oriented parental repertoire contributes to an infant's development and well-being. The role of oxytocin (OT) in promoting affiliative bonds and parenting has been established in numerous animal and human studies. Recently, acute administration of OT to a parent was found to enhance the carer's, but at the same time also the infant's, physiological and behavioural readiness for dyadic social engagement. Yet, the exact cues that are involved in this affiliative transmission process remain unclear. The existing literature suggests that motion and vocalization are key social signals for the offspring that facilitates social participation, and that distance and motion perception are modulated by OT in humans. Here, we employed a computational method on video vignettes of human parent–infant interaction including 32 fathers that were administered OT or a placebo in a crossover experimental design. Results indicate that OT modulates parental proximity to the infant, as well as the father's head speed and head acceleration but not the father's vocalization during dyadic interaction. Similarly, the infant's OT reactivity is positively correlated with father's head acceleration. The current findings are the first to report a relationship between the OT system and parental motion characteristics, further suggesting that the cross-generation transmission of parenting in humans might be underlaid by nuanced, infant-oriented, gestures relating to the carer's proximity, speed and acceleration within the dyadic context.

Keywords: oxytocin, parenting, social signal processing, motionese, motherese

1. Introduction

Effective parental care is known to increase a progeny's survival rates and developmental outcomes. Similarly, in humans, an infant-directed repertoire such as motionese and motherese (describing, respectively, the kinds of gestures and speech used with infants and toddlers) [1], was found to have behavioural- and developmental-enhancing effects [2]. The role for oxytocin (OT), a nine-amino acid peptide hormone, in the initiation and maintenance of affiliative bonds and parental repertoire has been elucidated in animal research that spans several decades [3], and more recently also in humans [4]. Similarly, the oxytocinergic system in the brain and periphery has been suggested to underlie the cross-generation transmission of parenting in humans [5]. For example, a single-dose of OT administered to a parent was found to enhance the parent's physiological, hormonal and behavioural readiness for social interaction with the infant, but at the same time to modulate the infant's readiness for social engagement, as reflected also in the infant's salivary OT increase [6]. However, the specific human carer's cues that are affected by OT, which may be central to this affiliative transmission process, remain largely unknown.

Seminal studies on the attachment phenomenon in animals show that motion and vocalization are key visual and auditory inputs for the offspring [7,8]. Likewise, motion generally attracts human infants’ attention [9]. For instance, during chasing, acceleration seems to be a key parameter to draw infants’ attention [10], and speed of others’ movements may automatically influence the observer's action (e.g. the timing of movement execution) [11]. Similarly, recent studies showed the OT-induced suppression of cortical activity at the alpha/mu and beta bands when biological motion is viewed [12], implying heightened sensitivity towards biological versus non-biological motion [13]. In addition, OT administration modulated social distance between males and females during interactions [14], and mothers’ speech stimulated OT release in girls [15]. Taken together, these findings suggest that proximity and movement might be affected by acute OT intervention, but also that parental vocalization is another nuanced feature that affects the OT system in humans.

In that context, this study tests whether intranasal OT administered to the parent may modulate the father's distance and motion characteristics as well as vocalization during interaction with his infant. To this end, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover experimental design was employed. A social signal processing (SSP) method of movement tracking [16] and of speech turn-taking [17] was applied in order to assess OT-induced changes in father–infant proximity and the father's movement and speech turn-tacking during interaction with his own infant. The father's head speed and acceleration were computed to account for movement. Finally, associations between the father's characteristics and infant's salivary OT increase following interaction were examined.

2. Material and methods

(a). Participants

Thirty-five healthy fathers (average age 29.7 years, s.d. = 4.2, range 22–38) participated with their five-month-old infants (s.d. = 1.25 months, range 4–8) in two laboratory visits, a week apart (total N = 70). Females were not enrolled in this study owing to physiological effects of OT manipulation (e.g. uterus contraction) and the need to control for menstrual cycle (For a detailed description, see the electronic supplementary material, S1)

(b). Procedure and oxytocin administration

Following their arrival at the laboratory, fathers were asked to self-administer 24 international units of either OT (Syntocinon Spray, Novartis, Switzerland) or a placebo. Administration order was counterbalanced, and participants and experimenters were blind to drug condition. Forty minutes after administration, the infant joined their father in the observation room. The infant was seated in an infant seat mounted on a table. Father–infant interaction began approximately 45 min after substance administration.

(c). Recording father–infant interaction

Each father–infant interaction lasted for 8 min: 3 min of free play, 2 min of parental still face and another 3 min of free play. Interactions were videotaped using a Flip Mino HD digital camcorder (Cisco, Irvine, CA) for off-line coding of behaviours.

(d). Computational analysis of parent–infant motion

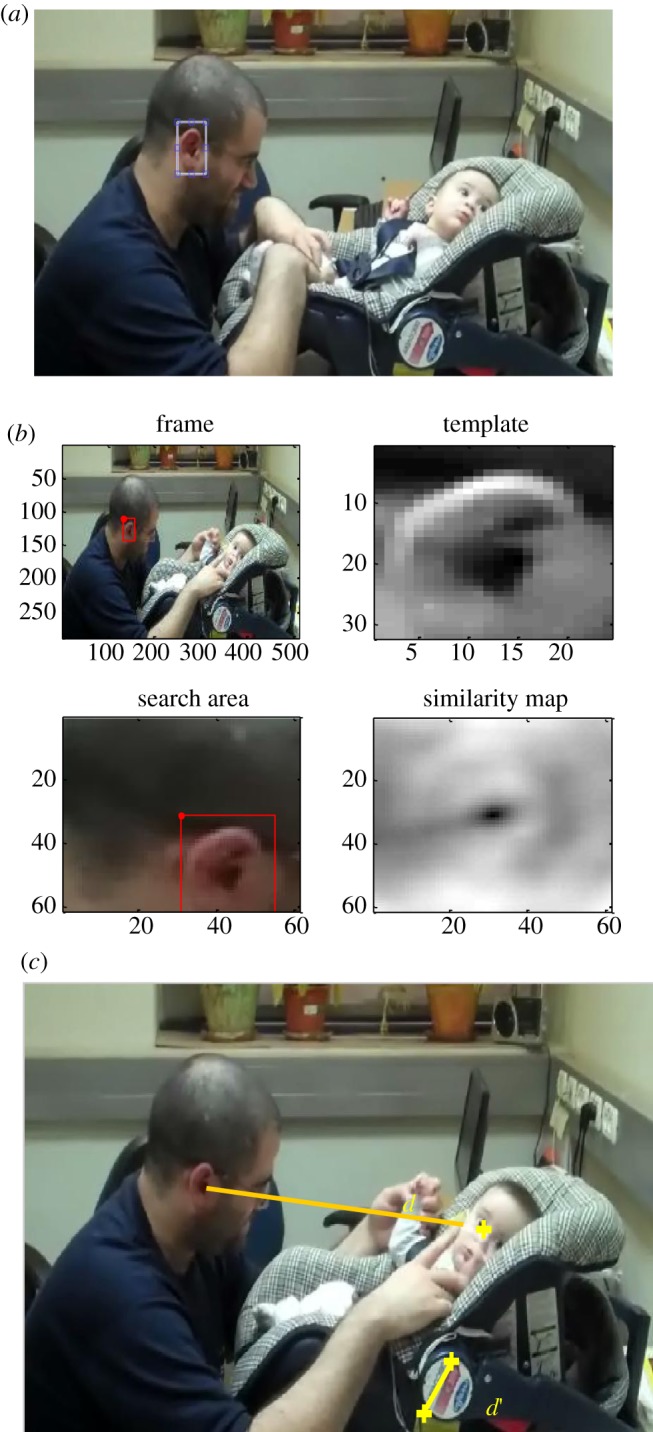

Parent–infant motion analysis was conducted based on a randomly selected 2 min long vignette extracted from the first 3 min of free play recording, using the following procedure: the position of the father's head was obtained by ear tracking (figure 1a). The position of the ear corresponds to the point with the highest similarity with the template (the dark spot on the similarity map; figure 1b). Distance was normalized according to a scale (diameter of the rotating device of the chair; d′; figure 1c) to take into account the zoom variations in the various sessions. Three variables were computed from the analysis: the distance between father and infant, the speed and the acceleration of the father. Several statistical parameters were extracted for each variable: mean, median, minimum, time to minimum (time until minimum was reached), maximum, time to maximum, range and standard deviation (see the electronic supplementary material, S2).

Figure 1.

Using SSP methods to assess father's distance from the infant, father's head speed and head acceleration during 2 min of parent–infant interaction. (Online version in colour.)

(e). Computational analysis of speech turn-taking

To assess speech turn-taking during father–infant interaction, the father's and infant's utterances were first segmented using ELAN. Then the infant's and father's utterances were labelled by two annotators (blind to drug condition) as vocalization (including laugh, singing and cry) or other noise. From the annotation, we extracted all the speech turns of the infant and the father using the algorithm specified in Delaherche et al. [17]. The following features were measured: father vocalization; infant vocalization; father pause; infant pause. We also extracted three features involving both partners simultaneously, i.e. synchrony variables: silence, overlap ratio and synchrony ratio (see the electronic supplementary material, S3).

(f). Salivary oxytocin collection and analysis

A full description of salivary OT collection and ELISA analysis is detailed in a previous publication [6]. The father's and infant's saliva samples were collected by Sallivatte (Sarstedt, Rommelsdorft, Germany) at multiple time-points: T1 (baseline)—before substance administration (father only); T2—40 min after administration prior to interaction; T3—20 min after interaction began (just after the still-face episode ended) and T4—20 min later. The Ratio of change in the infant's salivary OT following interaction with father in the OT session (i.e. infant OT at T3/infant OT at T2) was calculated. Log transformation was computed and the variable reached a normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

3. Results

(a). Oxytocin shapes parental motion, leaving parental vocalization unaffected

Table 1 details the fathers' distance, speed and acceleration between the OT and placebo sessions. Following OT administration, the maximum distance between father's head and the infant was greater, and minimum distance was reached earlier, compared with the placebo condition. The father's maximum head speed was higher, maximum speed was reached earlier and father's speed varied more (i.e. larger standard deviation), under OT influence. Similarly, the father's maximum head acceleration was greater, and acceleration tended to vary more in the OT condition. Also the minimum and maximum acceleration were reached earlier in the OT condition. As minimum speed and acceleration was found to be zero, range data and statistics equal the ones of the maximum parameter and are therefore disregarded from the results. By contrast, no significant differences relating to speech turn-taking parameters were found between the OT and the placebo conditions (table 2).

Table 1.

Comparing the fathers' distance, speed and acceleration in the OT and placebo conditions.

| oxytocin | placebo | s.d. | paired t-test | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| distance to childa | |||||

| mean | 7.238 | 6.944 | 1.225 | −1.356 | 0.092 |

| median | 7.195 | 6.909 | 1.336 | −1.210 | 0.118 |

| minimum | 4.787 | 4.693 | 1.403 | −0.381 | 0.353 |

| time to minimum | 0.481 | 0.585 | 0.331 | 1.764 | 0.044 |

| maximum | 10.021 | 9.401 | 1.700 | −2.063 | 0.024 |

| time to maximum | 0.535 | 0.525 | 0.483 | −0.114 | 0.455 |

| range | 5.234 | 4.708 | 2.227 | −1.334 | 0.096 |

| standard deviation | 1.015 | 0.893 | 0.636 | −1.091 | 0.142 |

| speed | |||||

| mean | 0.938 | 0.808 | 0.728 | −1.011 | 0.160 |

| median | 0.289 | 0.295 | 0.693 | 0.054 | 0.479 |

| minimum | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| time to minimum | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 1.162 | 0.127 |

| maximum | 45.421 | 35.744 | 27.308 | −2.005 | 0.027 |

| time to maximum | 0.441 | 0.635 | 0.408 | 2.696 | 0.006 |

| range | 45.421 | 35.744 | 27.308 | −2.005 | 0.027 |

| standard deviation | 2.547 | 2.044 | 1.668 | −1.704 | 0.049 |

| acceleration | |||||

| mean | 1.187 | 0.951 | 0.877 | −1.524 | 0.069 |

| median | 0.557 | 0.528 | 0.763 | −0.214 | 0.416 |

| minimum | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| time to minimum | 0.0007 | 0.0012 | 0.0015 | 1.939 | 0.031 |

| maximum | 59.439 | 46.889 | 33.737 | −2.104 | 0.022 |

| time to maximum | 0.412 | 0.593 | 0.394 | 2.605 | 0.007 |

| range | 59.439 | 46.889 | 33.737 | −2.104 | 0.022 |

| standard deviation | 3.624 | 2.763 | 2.871 | −1.696 | 0.050 |

aDistance is normalized according to fixed parameter (see §2).

Table 2.

Comparing speech turn-taking in the OT and placebo conditions.

| oxytocin | placebo | s.d. | paired t-test | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| father's speech turn-taking | |||||

| vocalization | 1.37 | 1.38 | 0.62 | 0.1 | 0.92 |

| pause | 1.61 | 1.45 | 0.75 | −1.0 | 0.32 |

| infant's speech turn-taking | |||||

| vocalization | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.1 | 0.90 |

| pause | 1.02 | 1.0 | 0.91 | −0.8 | 0.44 |

| speech turn-taking synchrony | |||||

| silence | 1.70 | 1.54 | 0.85 | −0.8 | 0.44 |

| overlap ratio | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.59 |

| synchrony ratio | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.99 |

(b). Parental motion correlates with infant oxytocin increase

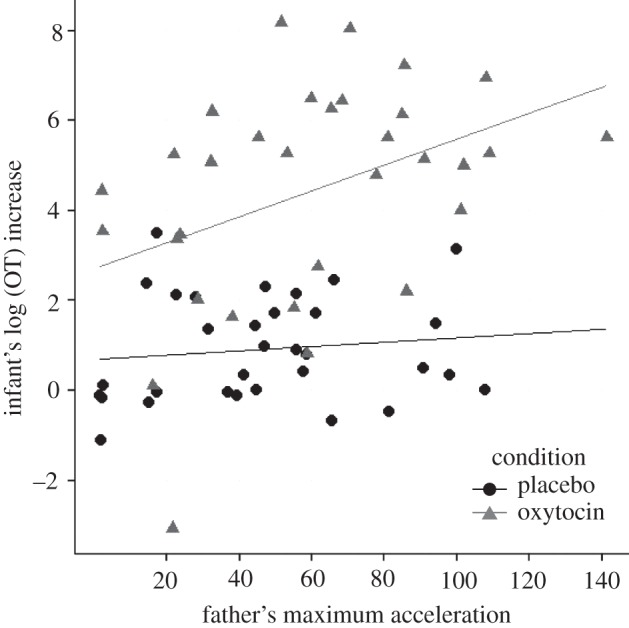

As there are two values per dyad studying association of the proximity parameters with infant's OT increase requires the use of mixed model analysis. From the parameters that were significantly modified under OT condition, none related to distance and speed was significantly associated with the infant's OT increase following interaction with the father. However, a significant correlation between a father's maximum head acceleration and the infant's OT increase was found, estimate = 0.026, p = 0.02. Post hoc correlation showed that in the placebo condition, correlation between the father's maximum acceleration and the infant's OT increase was not significant, r = 0.12, p = 0.50. By contrast, under OT condition, father's maximum head acceleration was found to positively correlate with infant's OT increase, r = 0.40, p = .02 (figure 2). Father's and infant's OT values can be found in the electronic supplementary materials, S4.

Figure 2.

Infant's log (OT) increase following interaction with father is correlated with father's maximum acceleration in the OT condition, but not in the placebo condition.

4. Discussion

The current findings are the first to show that OT administration to parent modulates a father's proximity and motion characteristics during interaction with his infant and that infant OT reactivity is associated with the carer's movement acceleration. Taken together, these findings show that the involvement of OT in the cross-generational transmission of human parenting is associated with specific, nearly hidden, features of infant-directed gestures along the movement/motion array. Specifically, OT administration markedly increased the maximum distance between father and infant, but at the same time drove fathers to reach their closest proximity to the infant earlier, as compared with the placebo condition. In addition, a father's head tended to move faster and to reach its highest velocity sooner under OT influence. Fathers showed greater acceleration which also tended to vary more. Finally, infant OT increase following interaction with the father correlated with a father's maximum acceleration parameter. OT did not alter central-oriented parameters of parental motion such as the mean and median, and was more related to the minimum and maximum (i.e. extreme) orientations, that is, to its distribution parameters as well as to the overall layout.

Social cues from carers that favour infant bonding are multimodal in humans and include vocalization (motherese) [8], imitation [18], synchronization [19] and infant-directed actions and gestures (motionese) [1,2]. Whether the variables assessed here fall under the common definition of motionese (i.e. actions and gestures that are typically slow and involve high levels of repetition and exaggerated movements), or whether they elaborate the existing framework of this concept remained to be answered. Either way, the results of this study imply that parental proximity and parental motion are involved in non-verbal parent–infant exchange, but moreover, that these modalities are susceptible to intervention in key neuroendocrine pathway that is central to the initiation and maintenance of parental repertoire, namely, the OT system. Future studies should examine whether OT shapes proximity and motion also among mothers interacting with their infants, between romantic partners, and other social circumstances. Finally, different aspects of parental vocalization other than speech turn-taking, for example motherese [20], should be taken into consideration and analysed in order to better decipher the specific channels through which exogenous OT enhances parent–infant interaction.

Acknowledgments

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Bar-Ilan University, was conducted according to ethical standards, and all participating fathers signed an informed consent.

Funding statement

The study was supported by the German-Israeli Foundation grant (no. 1114-101.4/2010) to R.F., by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-12-SAMA-006) to D.C., and the Groupement de Recherche en Psychiatrie (GDR-3557) to D.C. Sponsors had no involvement in study design, data analysis or interpretation of results.

References

- 1.Brand RJ, Baldwin DA, Ashburn LA. 2002. Evidence for motionese: modifications in mothers’ infant-directed action. Dev. Sci. 5, 72–83 (doi:10.1111/1467-7687.00211) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koterba EA, Iverson JM. 2009. Investigating motionese: the effect of infant-directed action on infants’ attention and object exploration. Infant Behav. Dev. 32, 437–444 (doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.07.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Insel TR. 2010. The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: a review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior. Neuron 65, 768–779 (doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter CS. 1998. Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23, 779–818 (doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00055-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman R. 2012. Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Horm. Behav. 61, 380–391 (doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.01.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisman O, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. 2012. Oxytocin administration to parent enhances infant physiological and behavioral readiness for social engagement. Biol. Psychiatry 72, 982–989 (doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenz KZ. 1935. Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. J. Ornithol. 83, 137–213, 289–413 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falk D. 2004. Prelinguistic evolution in early hominins: whence motherese? Behav. Brain Sci. 27, 491–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tronick E. 1972. Stimulus control and the growth of the infant's effective visual field. Percept. Psychophys. 11, 373–376 (doi:10.3758/BF03206270) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankenhuis WE, House B, Barrett HC, Johnson SP. 2013. Infants’ perception of chasing. Cognition 126, 224–233 (doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2012.10.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe K. 2008. Behavioral speed contagion: automatic modulation of movement timing by observation of body movements. Cognition 106, 1514–1524 (doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.06.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry A, Bentin S, Shalev I, Israel S, Uzefovsky F, Bar-On D, Ebstein RP. 2010. Intranasal oxytocin modulates EEG mu/alpha and beta rhythms during perception of biological motion. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 1446–1453 (doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.04.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keri S, Benedek G. 2009. Oxytocin enhances the perception of biological motion in humans. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 9, 237–241 (doi:10.3758/CABN.9.3.237) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheele D, Striepens N, Güntürkün O, Deutschländer S, Maier W, Kendrick KM, Hurlemann R. 2012. Oxytocin modulates social distance between males and females. J. Neurosci. 32, 16 074–16 079 (doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2755-12.2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seltzer LJ, Ziegler TE, Pollak SD. 2010. Social vocalizations can release oxytocin in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B 7, 2661–2666 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0567) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaherche E, Chetouani M, Mahdhaoui A, Saint-Georges C, Viaux S, Cohen D. 2012. Interpersonal synchrony: a survey of evaluation methods across disciplines. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comp. 3, 349–365 (doi:10.1109/T-AFFC.2012.12) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delaherche E, Chetouani M, Bigouret F, Xavier J, Plaza M, Cohen D. 2013. Assessment of communicative and coordination skills of children with pervasive developmental disorders and typically developing children using social signal processing. Res. Autism Spectr. Dis. 7, 741–756 (doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.003) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meltzoff AN, Kuhl PK, Movellan J, Sejnowski TJ. 2009. Foundations for a new science of learning. Science 325, 284–288 (doi:10.1126/science.1175626) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman R. 2007. Parent–infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing; physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 329–354 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01701.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saint-Georges C, Chetouani M, Cassel RS, Apicella F, Mahdhaoui A, Muratori P, Lanzik MC, Cohen D. 2013. Motherese, an emotion- and interaction-based process, affects infants’ cognitive development. PLoS ONE 8, e78103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]