Abstract

Specific immune priming enables an induced immune response upon repeated pathogen encounter. As a functional analogue to vertebrate immune memory, such adaptive plasticity has been described, for instance, in insects and crustaceans. However, towards the base of the metazoan tree our knowledge about the existence of specific immune priming becomes scattered. Here, we exposed the invasive ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi repeatedly to two different bacterial epitopes (Gram-positive or -negative) and measured gene expression. Ctenophores experienced either the same bacterial epitope twice (homologous treatments) or different bacterial epitopes (heterologous treatments). Our results demonstrate that immune gene expression depends on earlier bacterial exposure. We detected significantly different expression upon heterologous compared with homologous bacterial treatment at three immune activator and effector genes. This is the first experimental evidence for specific immune priming in Ctenophora and generally in non-bilaterian animals, hereby adding to our growing notion of plasticity in innate immune systems across all animal phyla.

Keywords: immune priming, bacteria, invertebrate, ctenophore, basal metazoan, adaptive plasticity

1. Introduction

At the base of the metazoan tree four phyla branch off prior to Bilateria: Cnidaria, Porifera, Placozoa and Ctenophora [1]. These simple multi-cellular animals are invaluable to understand comparatively the evolution of key metazoan traits, including development, neurobiology and immune defence. Their large and delicate body surfaces are exposed to a ‘soup’ of bacteria in the marine environment, prompting the question of how their apparently effective immune defence is ensured.

The immune system has the ‘double-edged’ task of discriminating and eliminating pathogenic non-self while minimizing damage to self. Specific immune priming permits an induced response upon secondary exposure to the same threat [2,3]. While immunological memory was traditionally considered a hallmark of the vertebrate adaptive immune system [4], there is growing evidence that invertebrate immune responses are also modulated upon repeated infections [5–8]. Such functional analogues to immune memory clearly reach down further in the tree of life [8] but distribution and mechanisms remain to be defined. There are some immune repertoire studies on cnidarians and sponges [9,10], while experimental evidence for immune priming in basal metazoans is lacking. The neighbouring phylum of Ctenophora has been largely ignored in comparative immunology, even though it might represent the most basal metazoans [1,11]. The lobate ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi gained wide recognition as an invasive species, introduced repeatedly from the Americas into Eurasian Seas [12]. As the first ctenophore with a sequenced genome [13] it may become the ‘model’ species of this phylum.

To investigate specific immune priming in M. leidyi, we measured immune gene expression upon two consecutive bacterial challenges. Ctenophores were exposed twice to heat-killed bacteria in a fully reciprocal design. In heterologous treatments, ctenophores were injected with two different bacteria, and in homologous treatments twice with the same agent. In the absence of specific immune priming, gene expression should solely depend on the second treatment. Alternatively, presence of specific immune priming would be identified if expression depends on the interaction of primary and secondary exposure and differs between homologous and heterologous treatments.

2. Material and methods

(a). Animal collection and experiment

Mnemiopsis leidyi were collected in the North Sea (Oostende, Belgium) and acclimatized at GEOMAR in North Sea water (35 psu) for 24 h. Ctenophores were individually kept in beakers (300 ml) throughout the experiment (see the electronic supplementary material, S1). For the immune challenge, two heat-killed bacteria were used: the Gram-negative bacterium Listonella anguillarum (DSM no. 11323) and the Gram-positive Planococcus citreus (ATCC 14404), dissolved in sterile, artificial seawater. This combination of two abundant marine pathogens has been applied to activate and characterize immunological responses in fishes [14]. Bacteria were grown as outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S1.

Ctenophores were injected through the mesoglea into the body cavity with 50 µl of L. anguillarum (L), P. citreus (P) or with artificial seawater as sham control (S). All animals received a subsequent secondary injection 84 h later with either the same strain (homologous), or a different bacterial strain (heterologous) or sham-exposed in a fully reciprocal set-up (table 1), afterwards they were transferred into fresh water. Six hours after secondary exposure, total RNA was extracted from four individuals per treatment combination (Invitek Spin Tissue RNA Mini, 36 samples). The set-up resulted in nine different treatments, including two homologous (LL and PP) and two heterologous bacterial treatments (LP and PL).

Table 1.

Experimental treatment combinations. Ctenophores were sequentially injected (T1 and 84 h later T2) with L. anguillarum (L), P. citreus (P) or sham treated (S) in a fully factorial design. This results in nine treatments, including homologous (ho) and heterologous (ht) bacterial exposures.

| first exposure (T1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| L. anguillarum | P. citreus | sham | |

| second exposure (T2) | |||

| L. anguillarum | LL (ho) | PL (ht) | SL |

| P. citreus | LP (ht) | PP (ho) | SP |

| sham | LS | PS | SS |

(b). Quantification of immune gene expression using Q-RT-PCR

Our seven target genes were preselected based on unpublished pooled EST-libraries of M. leidyi comprising four treatments (naive, sham, LPS or bacteria exposure; S Bolte*, EER Philipp*, L Kraemer, G Hemmrich-Stanisak, J Saphörster, O Roth, TBH Reusch, P Rosenstiel 2010 *shared first authorship, unpublished data). We identified differentially regulated genes via digital expression profiling that are putatively involved in bacterial sensing (see electronic supplementary material, S3). Primers flanking these target genes were designed using the software Primer3 [15] with melting temperatures around 60°C and amplicon length 80–160 bp (table 2; electronic supplementary material, S2). Gene expression was quantified with Q-RT-PCR as outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S3 relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH).

Table 2.

Genes and primers for quantitative real-time PCR in the ctenophore M. leidyi.

| primer | gene annotation | pathway/function | seq. 5′–3′ | amp. size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GADPH | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | glycolysis | AGG GCT GAT GAC TGT TC CCT CTC CCG TCT CTC CAT TT |

87 |

| A12 | peroxiredoxin | ROS/redox | CCC CAG CCT CAA TAA CTG AA ATG GCC GGT ACC GTA GAT TA |

103 |

| A4 | chitinase | chitin degradation, put. allorecognition | GTC GGG TCC TTG ACA ACA GT ACT GGG GAA GCA GGA TTT TT |

83 |

| TC1N | MACPF 14/lectin | complement | ATT TGC AGA TCG ACC AAA CC CCA AAC ACA CAA CTG GCA AC |

121 |

| TR2N | proPOdiphenoloxidase subunit A3 | ROS/redox melanization |

CTT CCA ATT TGT CAC CAG CA GGA GAG ATA ACC GAC CAG CA |

120 |

| TR3 | SOD Cu–ZN 7 | ROS/redox | AAT CCA CAT GGA GCC ACT TC TGC CCT CTT TGC TCT TGT TT |

80 |

| TR4N | complement factor B | complement, alternative pathway |

TCG ACC CAT CAC ACC TAA CA CCC ATG ACA ACG TGC ACT AC |

93 |

| L1N | adenosylhomocysteinase B | nucleic acid and protein metabolism | GTG GAG ACA CCC AGC GAT AC CTG ACA TCG AGT TGG CAG AA |

137 |

(c). Data analysis

Prior to (M)ANOVA data normality was tested using a Shapiro–Wilk test (JMP v. 10) and deviations from homogeneity using Levene's test. A two-way MANOVA across all genes was performed to test the effect of primary (T1) or secondary exposure (T2) or their interaction (priming effect) on gene expression. This was followed by two-way ANOVAs testing which genes contributed to the overall effect (see electronic supplementary material, S4). To unravel whether a priming effect may be specific, we performed planned contrast analyses comparing homologous (LL and PP) versus heterologous (LP and PL) bacterial treatments (see electronic supplementary material, S4). Analyses were performed in R v. 2.15.1 (www.r-project.org).

3. Results

Over all tested genes, no main effects of first or second exposure were significant. Rather, the interaction of both exposures significantly influenced gene expression (MANOVA: F = 1.71, p = 0.04**, table 3a; electronic supplementary material, S4), attesting a priming effect. This translated to univariate interactions in six of the seven genes, constituting the overall effect (see electronic supplementary material, S4). Finally, a planned contrast between homologous (ho) and heterologous (ht) bacterial challenges revealed a significantly different expression at four genes (table 3b; electronic supplementary material, S4), supporting specificity of the priming effect.

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of differential gene expression. (a) Two-way MANOVA over all genes testing the effects of first exposure (T1), second exposure (T2) and their interaction (T1 : T2). (b) Planned contrast between homologous (ho) and heterologous (ht) exposure. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01.

| d.f. | Pillai | approx. F | num d.f. | den d.f. | Pr(>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) two-way MANOVA | ||||||

| T1 | 2 | 0.69615 | 0.91528 | 14 | 24 | 0.55601 |

| T2 | 2 | 1.01764 | 1.77586 | 14 | 24 | 0.10461 |

| T1 : T2 | 4 | 1.85618 | 1.73166 | 28 | 56 | 0.04044* |

| residuals | 17 | |||||

| gene | contrast | d.f. | sum sq | mean sq | F-value | Pr(>F) |

| (b) planned contrasts | ||||||

| A12 peroxiredoxin |

ho versus ht | 1 | 4.14 | 4.145 | 2.575 | 0.1202 |

| A4 chitinase |

ho versus ht | 1 | 0.62 | 0.623 | 0.208 | 0.6527 |

| L1N adenosylhomocysteinase |

ho versus ht | 1 | 4.86 | 4.858 | 11.258 | 0.00263** |

| TR2N proPO |

ho versus ht | 1 | 11.84 | 11.839 | 5.030 | 0.0333* |

| TR3 SOD |

ho versus ht | 1 | 10.61 | 10.61 | 4.548 | 0.0422* |

| TR4N complement factor B |

ho versus ht | 1 | 3.41 | 3.409 | 7.304 | 0.0124* |

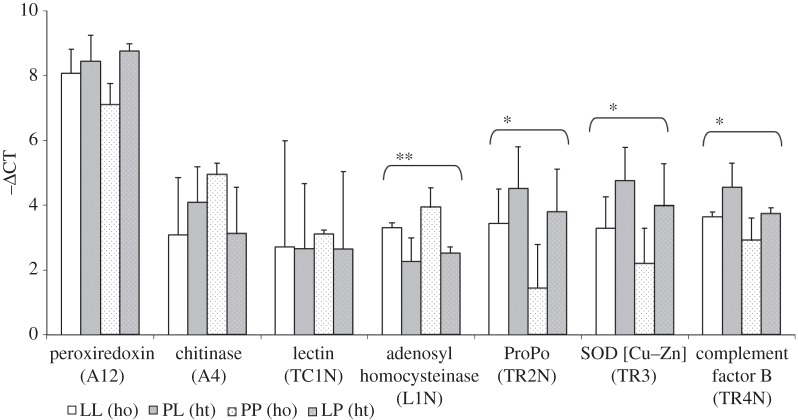

Relative expression of all genes comparing homologous (ho) or heterologous (ht) bacterial exposure is shown in figure 1 (all groups in the electronic supplementary material, S5). Four genes showed significantly modulated expression: adenosylhomocysteinase (L1N) was higher expressed in the homologous treatment whereas expression of prophenol oxidase (proPO, TR4N), superoxide dismutase (TR3) and complement factor B1 (TR4N) was decreased upon homologous compared with heterologous bacterial exposure.

Figure 1.

Differential gene expression between homologous (ho) and heterologous (ht) pathogen exposure. Ctenophores were injected with L. anguillarum (L) or P. citreus (P), resulting in homologous (LL and PP) and heterologous (PL and LP) treatments. Expression of seven immune-related genes (–ΔCT ± s.d., all values transferred to positive scale by addition of 5CTs). Four genes showed significantly different expression: adenosylhomocysteinase was upregulated upon homologous treatment; Propo, SOD and complement factor B showed lower expression after homologous treatment (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, for exact p-values, see table 3b).

4. Discussion

The expression of immune-related genes in M. leidyi was not only determined by the acute bacterial challenge but also depended on previous pathogen exposure. Such a plastic response implies the presence of immune priming in the phylum Ctenophora that comes with a certain degree of specificity regarding the treatment with two distinct bacteria, i.e. a Gram-negative Vibrio and a Gram-positive Planoccus.

We described the ctenophore immune response via expression of candidate genes which had been preselected from pooled cDNA libraries of sham and bacteria-challenged individuals. Their putative immune function has not yet been assessed directly in ctenophores and functional interpretation relies on homology to the phylogenetically closest examples (mostly Cnidaria). ProPO/diphenoloxidase expression was reduced upon homologous compared with heterologous exposure. Phenoloxidase activity (melanization) is an important component of innate immunity in invertebrates, mostly studied in arthropods and crustaceans [16] and an important role in cnidarian immune defence of corals, with an upregulation in pigmented tissues as part of an inflammatory response [17]. Superoxide dismutase (Cu–Zn SOD) catalyses the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide [18], and thus plays an important role in inflammatory processes [19]. SOD is known as a major player in the breakdown of cnidarian–dinoflagellate symbiosis during coral bleaching [20]. Here, its expression was reduced upon homologous compared with heterologous bacterial challenge. Such reduced inflammatory response after homologous exposure, detected for phenoloxidase and superoxide dismutase, may save resources and reduce self-damage. Complement factor B is involved in the alternative pathway of complement activation directly from the pathogen surface [21]. This evolutionarily oldest pathway of complement activation [22] is present in Cnidaria but to date unexplored in Porifera and Ctenophora [23]. Here, we observed significantly lower expression in homologous compared with heterologous treatment, indicating that complement activation contributes to specific immune priming of ctenophores. Increased expression of the metabolic enzyme adenosylhomocysteinase in homologous, as opposed to heterologous treatments suggests enhanced metabolic function in these animals.

At the first glance, lower gene expression after homologous compared with heterologous treatment at three immune receptor and effector genes seems puzzling. However, these findings are consistent with evolutionary theory predicting that selection drives species to minimize costs and self-damage of immune defence [2,3]. In line with this, the expression of a general metabolic enzyme adenosylhomocsteinase was increased after homologous compared with heterologous bacterial challenge. According to the concept of immune priming, a specific response to repeated infections would also include upregulation of particular immune pathways matching this encounter (reviewed in [24]). We did not observe such upregulation of immune effectors after homologous exposure, indicating that either the repeated injections with heat-killed bacteria were not recognized as real threats (infections) or the specifically upregulated genes were not included in our candidate gene set. Future research including transcriptome-wide analysis of gene expression should help to identify pathways specifically upregulated after repeated exposure.

Despite this limitation, our study provides experimental evidence that immune gene expression of M. leidyi is induced through pre-exposure. To our knowledge, this is the first observation of immune priming in the phylum Ctenophora and in an invertebrate prior to Bilateria. This study should encourage future research to unravel the significance of this process, its molecular mechanisms and ecological implications. Ultimately, such plasticity will enhance the ecological performance of comb jellyfish and contribute to their success in changing global oceans.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lies Vansteenbrugge for help with sampling, Lars Krämer for IT support, Rudi Lüthje and Svend Mees for technical support, and Katrin Beining and David Haase for help with the laboratory work.

Funding statement

This study was financially supported by grants from the DFG (T.B.H.R.) and Volkswagen foundation (O.R.).

References

- 1.Edgecombe GD, Giribet G, Dunn CW, Hejnol A, Kristensen RM, Neves RC, Rouse GW, Worsaae K, Sørensen MV. 2011. Higher-level metazoan relationships: recent progress and remaining questions. Organ. Divers. Evol. 11, 1–22 (doi:10.1007/s13127-011-0044-4) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid-Hempel P, Ebert D. 2003. On the evolutionary ecology of specific immune defence. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 27–32 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)00013-7) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulenburg H, Kurtz J, Moret Y, Siva-Jothy MT. 2009. Introduction. Ecological immunology. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 3–14 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0249) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed R, Gray D. 1996. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science 272, 54–60 (doi:10.1126/science.272.5258.54) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadd BM, Kleinlogel Y, Schmid-Hempel R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2005. Trans-generational immune priming in a social insect. Biol. Lett. 1, 386–388 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0369) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson KN, van Hulten MCW, Barnes AC. 2008. ‘Vaccination’ of shrimp against viral pathogens: phenomenology and underlying mechanisms. Vaccine 26, 4885–4892 (doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth O, Sadd BM, Schmid-Hempel P, Kurtz J. 2009. Strain-specific priming of resistance in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 145–151 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1157) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz J. 2004. Memory in the innate and adaptive immune systems. Microb. Infect. 6, 1410–1417 (doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2004.10.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller WEG, Mueller IM. 2003. Origin of the metazoan immune system: identification of the molecules and their functions in sponges. Integr. Comp. Biol. 43, 281–292 (doi:10.1093/icb/43.2.281) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller DJ, Hemmrich G, Ball EE, Hayward DC, Khalturin K, Funayama N, Agata K, Bosch T. 2007. The innate immune repertoire in Cnidaria - ancestral complexity and stochastic gene loss. Genome Biol. 8, R59 (doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r59) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn CW, et al. 2008. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature 452, 745–749 (doi:10.1038/nature06614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reusch TBH, Bolte S, Sparwel M, Moss AG, Javidpour J. 2010. Microsatellites reveal origin and genetic diversity of Eurasian invasions by one of the world's most notorious marine invader, Mnemiopsis leidyi (Ctenophora). Mol. Ecol. 19, 2690–2699 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04701.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan JF, Pang K, Moreland RT, Nguyen A, Nisc, Wolfsberg TG, Mullikin JC, Martindale MQ, Baxevanis AD. The genome of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and its implications on the history of animals. Integr. Comp. Biol. 51, E120 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandes JMO, Smith VJ. 2002. A novel antimicrobial function for a ribosomal peptide from rainbow trout skin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 296, 167–171 (doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00837-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132, 365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerenius L, Lee BL, Söderhäll K. 2008. The proPO-system: pros and cons for its role in invertebrate immunity. Trends Immunol. 29, 263–271 (doi:10.1016/j.it.2008.02.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petes L, Harvell C, Peters E, Webb M, Mullen K. 2003. Pathogens compromise reproduction and induce melanization in Caribbean sea fans. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 264, 167–171 (doi:10.3354/meps264167) [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCord JM, Fridovich I. 1969. Superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 6049–6055 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marikovsky M, Ziv V, Nevo N, Harris-Cerruti C, Mahler O. 2003. Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase plays important role in immune response. J. Immunol. 170, 2993–3001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weis VM. 2008. Cellular mechanisms of cnidarian bleaching: stress causes the collapse of symbiosis. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 3059–3066 (doi:10.1242/jeb.009597) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janeway CA, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M. 2005. Immunobiology: the immune system in health & disease. New York, NY: Garland Publishing [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nonaka M, Kimura A. 2006. Genomic view of the evolution of the complement system. Immunogenetics 58, 701–713 (doi:10.1007/s00251-006-0142-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerenius L, Kawabata S, Lee BL, Nonaka M, Söderhäll K. 2010. Proteolytic cascades and their involvement in invertebrate immunity. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 575–583 (doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulenburg H, Boehnisch C, Michiels NK. 2007. How do invertebrates generate a highly specific innate immune response? Mol. Immunol. 44, 3338–3344 (doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.02.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]