Abstract

Anorexia nervosa (AN) patients exhibit a disparity in their actual physical identity and their cognitive understanding of their physical identity. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tasks have contributed to understanding the neural circuitry involved in processing identity in healthy individuals. We hypothesized that women recovering from AN would show altered neural responses while thinking about their identity compared with healthy control women. We compared brain activation using fMRI in 18 women recovering from anorexia (RAN) and 18 healthy control women (CON) using two identity-appraisal tasks. These neuroimaging tasks were focused on separable components of identity: one consisted of adjectives related to social activities and the other consisted of physical descriptive phrases about one’s appearance. Both tasks consisted of reading and responding to statements with three different perspectives: Self, Friend and Reflected. In the comparisons of the RAN and CON subjects, we observed differences in fMRI activation relating to self-knowledge (‘I am’, ‘I look’) and perspective-taking (‘I believe’, ‘Friend believes’) in the precuneus, two areas of the dorsal anterior cingulate, and the left middle frontal gyrus. These data suggest that further exploration of neural components related to identity may improve our understanding of the pathology of AN.

Keywords: mentalization, identity, precuneus, eating disorders, cingulate

INTRODUCTION

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a psychiatric illness consisting of the maintenance of a low body weight, a fear of gaining weight, amenorrhea and either a disturbance in the perception of one’s actual body weight or shape or a denial of the seriousness of current low body weight (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The body-image disturbance in AN has been most consistently observed as a cognitive-evaluative dissatisfaction with body shape (Cash and Deagle, 1997; Skrzypek et al., 2001). Stein and Corte (2003) proposed that body-image disturbance is only one of a number of components related to identity altered in AN. Identity can be defined as the stable but evolving set of memory structures relating to one’s own experiences, and further dissected into cognitive sets of specific self-knowledge relating to different dimensions, frequently referred to as self-schemas, such as personality traits and body image (Stein and Corte, 2007). Their work has suggested that eating disorders are associated with the presence of fewer self-schemas, more inter-related than separable self-schemas, more negative self-schemas than positive and the presence of a fat self-schema (Stein and Corte, 2007; Stein and Corte, 2008).

A number of other lines of evidence converge around the concepts of self-knowledge deficits in anorexia. Alexithymia is a term that describes impairments in one’s self-knowledge regarding emotions (Nemiah, 1977), and elevated levels of alexithymia have been found in as many as 77% of AN patients (Bourke et al., 1992; Corcos et al., 2000). Low self-esteem has also been proposed to contribute to eating disorders (Silverstone, 1992; Vanderlinden et al., 2009) and has been associated with the development of eating disorders (Button et al., 1996). Tafarodi and Swann (1995) operationalized two components of self-esteem, the self-competence component relating to the belief that one can achieve things and the self-liking component related to the feelings one has about whether one is a good person. Both measures are frequently low in AN patients, and the severity of illness has been correlated with the self-competence component (Paterson et al., 2007; Surgenor et al., 2007).

Finally, neuroscience results have begun to be reported from AN subjects viewing their own image and thinking about their body image. Several studies of body image in AN have reported differences in parietal and occipital regions specific to the viewing of self-photographs (Wagner et al., 2003; Sachdev et al., 2008; Vocks et al., 2011). Friederich and colleagues (2010) similarly showed differences in the cingulate and insula when subjects were not asked to view themselves, but only to imagine themselves in comparison to a displayed image of a slim model. Elevated activations in MPFC in response to negative body-image words have been seen in both binge–purge AN and bulimia nervosa (Miyake et al., 2010). These studies indicate that neural regions that encode that body-image self-schema function differently in people with AN.

In addition to problems in the development of stable, positive self-schemas that form their identity, AN patients may also struggle to understand other people. Social difficulties occur in AN patients before the illness appears, during the course of the illness and even following recovery from AN (Wentz et al., 2001; Troop and Bifulco, 2002; Zucker et al., 2007). Emotional recognition has been found to be impaired in both recovered and currently ill AN patients in a number of studies using a variety of psychological tasks (Zonnevijlle-Bender et al., 2002; Kucharska-Pietura et al., 2004; Harrison et al., 2009, 2010; Oldershaw et al., 2010). Low levels of mentalization, the ability to understand another person’s perspective, have been associated with development of eating disorders (Rothschild-Yakar et al., 2010). Improvements in psychosocial relationships have also been closely tied to recovery (Nilsson and Hagglof, 2006). Recently, we observed decreased activation in network regions subserving social cognition in recovering AN subjects (McAdams and Krawczyk, 2011).

The neural networks involved in self-knowledge have been suggested to consist primarily of cortical midline structures (CMSs), organized in three primary clusters (Northoff et al., 2006). The ventral cluster includes the medial orbitofrontal cortex, ventromedial prefrontal cortex and subgenual anterior cingulate cortex; the dorsal cluster consists of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC) and supragenual anterior cingulate cortex and a posterior cluster includes the posterior cingulate, the precuneus and medial partial cortex. A different but partially overlapping neural network, composed of the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), the fusiform gyrus, the inferior frontal gyrus, the precuneus, the temporal poles and the temporoparietal junction, is activated when processing social stimuli (Castelli et al., 2002; Schultz et al., 2003; Saxe et al., 2004; Saxe and Wexler, 2005; Frith and Frith, 2006). As understanding aspects of oneself can facilitate the understanding of other people and the converse; several regions including the DMPFC and the precuneus are involved in both the self-knowledge neural network and the social cognition neural network (Heatherton, 2011).

Social appraisal tasks present adjectives or statements to the subjects and ask the subjects to reflect on the validity of the words in characterizing themselves, someone else or themselves from their friend’s point of view. Studies in healthy controls have reported activation in CMSs when participants evaluated their self ‘I believe I am … ’ in contrast to someone else ‘I believe my friend is … ’ (Johnson et al., 2002; Ochsner et al., 2005; Moran et al., 2006; D’Argembeau et al., 2007; Modinos et al., 2009). In contrast, when healthy individuals evaluated their self from another person’s perspective, ‘Someone else believes I am … ’ in comparison to ‘I believe I am … ’, activation has been reported in the precuneus, posterior cingulate, temporoparietal junction and MPFC, components of a network relevant to social cognition (Ochsner et al., 2005; D’Argembeau et al., 2007; Pfeifer et al., 2007; Pfeifer et al., 2009).

We examined the processes of self-knowledge and mentalization by comparing cortical activity in recovering AN patients and healthy controls using two similar appraisal functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tasks; one involving socially descriptive adjectives and a second with physically descriptive phrases. The goal of this study was to examine the neural representations of two different types of self-schemas, one focusing on socially descriptive adjectives and a second focusing on body-image evaluations. This design allowed a comparison of differences in the neural processing associated with thinking about oneself from a social viewpoint and a physical state. We hypothesized that neural regions involved in the social and physical identity would be less active in the AN subjects with more differences relating to physical comparisons.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Participants

A total of 36 female participants, between 18 and 45 years of age, were recruited for this study. The participant groups consisted of 18 healthy controls (CON) and 18 individuals with a recent history of anorexia but currently in the process of recovering from AN (RAN). The RAN participants were recruited from the Dallas, TX area. All RAN participants had maintained a minimum body mass index (BMI) >17.5 and had menstrual cycles for at least 2 months, with no reported binging or purging behaviors during the previous month. All RAN subjects had met full criteria for AN within the previous 2 years; this time period was chosen because several studies have shown that psychological recovery from anorexia lags the physical or physiological weight gain by at least 2 years (Strober et al., 1997; Bachner-Melman et al., 2006; Bardone-Cone et al., 2010). Ten of the RAN subjects had maintained a stable weight with menses and BMI > 19 for over 6 months. The other eight RAN subjects had maintained BMIs exceeding 17.5 for only 3–6 months. Eleven of the RAN subjects had the restricting subtype and seven had the binge–purge subtype of AN.

Subjects provided written informed consent to participate in this study at an initial appointment. All subjects were then interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-RV) disorders to confirm the history of anorexia in the RAN group, the absence of eating disorders in the CON group and the absence of other current Axis I disorders, including a current major depressive episode (MDE), depression not otherwise specified and dysthymia, in both groups. Participants were also screened for MRI compatibility. Some of the subjects had a history of recurrent Major Depressive Disorder (1, CON; 7, RAN) but none had met symptom criteria for an MDE for at least 3 months prior to the neuroimaging studies. No participants had a current or past diagnosis of any psychotic disorders or bipolar disorder; no participants were currently taking mood-stabilizers, antipsychotics or benzodiazepines. Participants on antidepressants whose dosage had not changed for at least 3 months prior to their MRI scans were included (1 CON; 8 RAN). This study was approved by the institutional review boards of both the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and The University of Texas at Dallas.

Participants also completed the Quick Inventory of Depression, Self-Report (QIDS-SR), a self-report questionnaire consisting of 16 items to assess current symptoms of depression (Rush et al., 2003), as well as the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26), a self-report questionnaire consisting of 26 items that relate to current eating behaviors (Berland et al., 1986). Subjects also completed the Self-Liking and Self-Competence Self-Esteem Questionnaire, a 16 item self-report questionnaire that provides two measures of self-esteem (Tafarodi and Swann, 1995).

Neuroimaging tasks

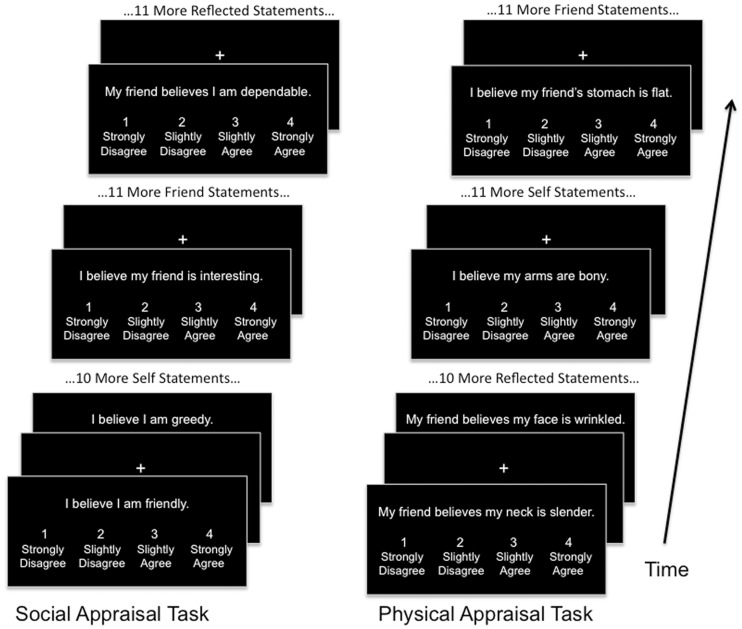

Two fMRI tasks were employed, the Social task and the Physical task (Figure 1). Both tasks consisted of the presentation of written appraisal statements projected onto a screen within the MRI scanner. For both tasks, three different types of appraisals were shown: Self (evaluation of an attribute about one’s own identity based on one’s own opinion); Friend (evaluation of an attribute about a close female friend); and Reflected (evaluation of an attribute about one’s self as believed by one’s friend). Each statement was presented above a scale reading 1, ‘strongly disagree;’ 2, ‘slightly disagree;’ 3, ‘slightly agree’ and 4, ‘strongly agree’. Subjects were asked to read each statement and select a rating through a hand-held button. The friend and reflected statements were personalized to contain the name of a specific female friend of each subject. Each task was conducted separately, with all runs of the social task preceding any runs of the physical task. This is a limitation of the study, resulting a desire to limit the overall duration of time necessary to collect complete data sets for each task to minimize potential motion artifacts. Each task consisted of four runs containing 36 statements each, 12 statements of each task condition within each run for a total duration of 6 min per run. All statements for each condition were sequential for each run, and the order of the conditions was pseudorandomized across runs. Each statement was presented for 4 s followed by a jittered fixation period of 4, 6 or 8 s.

Fig. 1.

Both tasks included four fMRI runs consisting of the presentations of appraisal statements with intervening fixation periods. During the presentation of each statement, subjects would read and respond using a hand-held button box. Within each run, all statements for each condition (self, friend and reflected) would occur sequentially.

In the social task, the self statements were presented in the format ‘I believe I am kind’, friend statements were in the format ‘I believe my friend is thoughtful’ and reflected statements were in the format ‘My friend believes I am selfish’. The same adjectives were shown for each condition. For the physical task, self statements were presented in the format ‘I believe my arms are toned’, friend statements in the format ‘I believe my friend’s eyes are bloodshot’ and reflected statements in the format ‘My friend believes my skin is smooth’. An effort was made to avoid containing only words that could be considered synonymous with fat and thin descriptors. For both the social and physical tasks, an approximately equal number of words perceived as positive or negative were selected (See Supplementary Table S1 for word lists).

MRI acquisition and analysis

All images were acquired with a 3 T Philips MRI scanner. Functional images were acquired during eight runs (four for social and four for physical), each lasting 360 s, using a 1-shot gradient T2*-weighted echoplanar (EPI) image sequence sensitive to blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) contrast. Each sequence was acquired using a repetition time (TR) of 2 s, an echo time (TE) of 35 ms and a flip angle of 0°. Volumes were composed of 36 axial slices (4 mm thick, no gap). Each slice was acquired with a 22.0-cm2 field of view, a matrix size of 64 × 64 and a voxel size of 3.4 × 3.4 × 4 mm. Head motion was limited using foam padding. High resolution MP-RAGE 3D T1-weighted images were acquired for anatomical localization with the following imaging parameters: TR = 2100 ms, TE = 3.7 ms; slice thickness of 1 mm with no gap, a 12° flip angle and 1 mm3 voxels.

Prior to statistical analyses, preprocessing consisted of spatial realignment to the first volume of acquisition, normalization to the MNI standard template and spatial smoothing with a 6-mm 3D Gaussian kernel. Functional MRI task data were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM5, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience London, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) run in matlab 7.4 (http://www.mathworks.com) and viewed in xjview (http://www.alivelearn.net/xjview8/). The fMRI data were analyzed separately with the same techniques for the social and the physical tasks. Each task was analyzed using an event-related design, in which each type of event (self, friend and reflected) corresponded to the BOLD signal during the 4-s presentation of each statement. A general linear model was used to create contrast images for each trial type. Activation of each trial type was assessed using multiple regression analysis set as boxcar functions. Each regressor was convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function provided in SPM5 and entered into the modified general linear model of SPM5. Parameter estimates (e.g. beta-values) were extracted from this GLM analysis for the regressors. A high-pass filter (cutoff 128 s) was applied to the data to remove frequency effects. Resulting single-subject one-sample t-test contrast images (self–friend; friend–self; reflected–self and self–reflected) were created for each participant. These contrast images were combined for group map analyses. A first-level analysis examined activations by task in the contrast images for each participant population (CON and RAN). A second-level analysis used two-sample t-tests to provide a whole-brain voxel-wise comparison of data obtained from the CON and RAN group contrasts, setting an initial threshold of voxel-wise P < 0.001, uncorrected and minimum cluster size of 20 to identify regions with group differences. Because this was an exploratory study of activations associated with identity for this patient population, we did not define a priori regions of interest (ROIs). Instead, we selected as ROIs those areas that emerged from voxel-wise whole-brain t-tests for the contrasts for the CON and RAN groups. We then extracted the percent signal change occurring within each region for each subject using the MarsBar toolbox (sourceforge.net/projects/marsbar) and transferred this data to SPSS (SPSS, Inc., Chicago) for between-group t-tests using a corrected significance threshold of P = 0.0125 (P = 0.05/4 regions tested).

Correlations between the clinical scales and neural activity were further examined in SPSS using a Pearson’s correlation analysis of the four scales (SL, SC, QIDS and EAT) against the activation of these ROIs. These correlations were done both across all subject groups and within each participant group, with the threshold for significant correlations set at P < 0.0125 (P = 0.05/4, as four tested scales).

RESULTS

Demographic measures and scales

The CON and RAN groups were not significantly different in age or years of education but differed in BMI (Table 1). The two groups also showed significant differences in both the psychiatric symptom scales for depression and current eating behavior as well as in the psychological measures for both the self-liking and the self-competence components of self-esteem.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and symptom scale values for the participants

| CON (n = 18) |

RAN (n = 18) |

Independent t-test |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | t | P | |

| Average age (years) | 24.5 (6.4) | 18–39 | 26.1 (6.8) | 18–40 | −0.708 | 0.484 |

| Mean years of education | 15.8 (2.1) | 14–20 | 14.9 (1.9) | 12–19 | 1.250 | 0.220 |

| Current BMIa | 23.2 (4.2) | 18–35 | 19.8 (1.6) | 18–23 | 3.096 | 0.004* |

| Months in recoveryb | NA | NA | 7.6 (5.2) | 3–20 | NA | NA |

| Lowest BMIc | NA | NA | 16.4 (1.1) | 14.5–18.3 | NA | NA |

| Quick inventory of depression | 3.7 (2.3) | 0–9 | 8.5 (4.7) | 2–17 | −3.923 | <0.001* |

| Eating attitudes test | 4.3 (4.1) | 0–15 | 27.4 (16.1) | 1–61 | −5.894 | <0.001* |

| Self-liking and competence scale | ||||||

| Self-liking | 30.7 (5.3) | 19–40 | 17.2 (7.0) | 8–29 | 6.520 | <0.001* |

| Self-competence | 30.2 (4.5) | 24–40 | 24.7 (4.5) | 18–37 | 3.656 | 0.001* |

aMean and range for RAN subjects exclude one outlier.

bMonths since meeting full criteria for AN.

cLowest BMI in the preceding 2 years. *p < 0.05

FMRI task performance: behavioral data

Each appraisal statement was presented for 4 s, during which the subjects were expected to read and respond to each statement using a 4-point rating scale. Response times varied slightly across tasks and conditions, but no significant differences were observed across groups (Supplementary Table S2). There was a significant difference across groups on the rating scales during both the social self condition (means CON 2.53, RAN 2.44, t(34) = 2.236, P = 0.032) and social reflected condition (means CON 2.53, RAN 2.38, t(34) = 5.102, P < 0.001), but not in the social friend condition (means CON 2.49, RAN 2.46, t(34) = 0.713, P = 0.48). There were no ratings differences across group for conditions of the physical task.

FMRI activation during social appraisals in CON and RAN groups

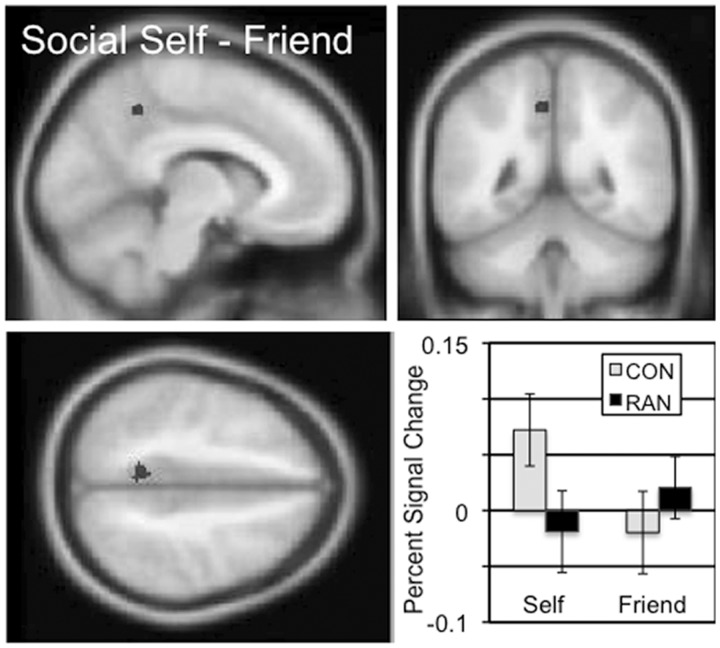

Cortical regions involved in the processing of social self-knowledge were identified based on the self–friend (‘I am’) contrast in the social task (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). In the CON subjects, there were four significantly active clusters in the occipital lobe. The RAN subjects showed more active clusters in this contrast, including a large cluster in the occipital lobe, as well as bilateral activation in parietal cortex, frontal cortex, the inferior and the middle frontal gyri. The self (‘I am’) two-sample comparison between the CON and RAN subjects revealed a single cluster in the dorsal precuneus, which showed increased percent signal change in the self condition than the friend condition for the CON subjects and the opposite pattern in the RAN subjects (Figure 2 and Table 3; mean percent signal change, social self–friend, CON 0.09, RAN −0.04, t = 4.590, P < 0.001). In the social friend–self (‘Friend is’) contrast, both the CON subjects and the RAN subjects showed single cluster in the ventral precuneus (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). In the ‘Friend is’ two-sample comparison, a region in the left middle frontal gyrus (MFG) also showed differential activation by group (Table 3, mean percent signal change, social friend–self, CON − 0.10, RAN − 0.53, t = 3.550, P = 0.001; Supplementary Figure S2).

Table 2.

Locations of significantly activated regions in the social task contrasts for the recovering anorexia subjects (RAN) and the healthy comparison subjects (CON)

| Anatomical region | BA | Laterality | Cluster size | Cluster Pa | Peak t | MNI x, y, z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON group map: social self–friend | ||||||

| Lingual | 18 | L | 915 | 0.000 | 8.7 | −4, −94, −4 |

| 7.83 | −16, −90, 8 | |||||

| 7.21 | −10, −78, −2 | |||||

| Lingual | 18 | R | 454 | 0.000 | 6.83 | 8, −82, −4 |

| 6.42 | 12, −90, 12 | |||||

| 4.51 | 16, −88, −10 | |||||

| Occipital | 19 | R | 115 | 0.007 | 6.13 | 32, −86, 12 |

| 4.18 | 24, −76, 16 | |||||

| Occipital | 19 | L | 290 | 0.000 | 6.11 | −24, −68, −18 |

| 4.77 | −28, −78, −20 | |||||

| 4.14 | −18, −70, −4 | |||||

| RAN group map: social self–friend | ||||||

| Occipital | 18 | R | 4399 | 0.000 | 8.86 | 24, −92, −2 |

| 8.09 | −28, −62, −32 | |||||

| 7.45 | 34, −64, −22 | |||||

| Superior parietal | 7 | L | 1358 | 0.000 | 8.80 | −22, −64, 48 |

| 6.76 | −30, −58, 46 | |||||

| 6.07 | −16, −72, 50 | |||||

| Caudate | NA | R | 95 | 0.009 | 7.35 | 16, 14, −2 |

| 3.86 | 18, 18, −10 | |||||

| Middle frontal | 9 | L | 1293 | 0.000 | 7.27 | −54, 18, 30 |

| 6.29 | −22, −2, 56 | |||||

| 5.88 | −42, 6, 40 | |||||

| Superior frontal | 6 | R | 923 | 0.000 | 7.23 | 6, 8, 58 |

| 6.15 | −8, 18, 62 | |||||

| 5.90 | −4, 14, 42 | |||||

| Inferior frontal | 47 | L | 560 | 0.000 | 6.46 | −44, 40, 2 |

| 6.39 | −46, 30, 0 | |||||

| 5.93 | −54, 12, 2 | |||||

| Superior temporal gyrus | 38 | R | 166 | 0.000 | 6.14 | 48, 16, −10 |

| 5.07 | 38, 24, −6 | |||||

| 4.49 | 32, 16, −4 | |||||

| Precuneus | 7 | R | 539 | 0.000 | 5.97 | 18, −70, 50 |

| 5.75 | 26, −68, 48 | |||||

| 5.52 | 32, −62, 46 | |||||

| Middle frontal | 9 | R | 75 | 0.030 | 5.79 | 36, 32, 28 |

| 3.91 | 46, 34, 24 | |||||

| Inferior parietal | 40 | R | 75 | 0.030 | 5.71 | 38, −50, 42 |

| 4.52 | 42, −48, 52 | |||||

| 4.31 | 40, −42, 40 | |||||

| Cerebellum | NA | R | 74 | 0.032 | 5.64 | 10, −76, −44 |

| 4.15 | 18, −68, −48 | |||||

| Inferior frontal | 45 | R | 137 | 0.001 | 5.04 | 36, 2, 22 |

| 4.40 | 50, 12, 20 | |||||

| 4.30 | 60, 16, 20 | |||||

| CON group map: social friend–self | ||||||

| Post cingulate | 31 | R | 468 | 0.000 | 6.49 | 6, −50, 18 |

| Precuneus | L | 5.93 | −2, −50, 26 | |||

| 5.70 | −12, −58, 22 | |||||

| RAN group map: social friend–self | ||||||

| Precuneus | 31 | R | 182 | 0.000 | 6.95 | 14, −50, 34 |

| 4.90 | −2, −54, 36 | |||||

| CON group map: social reflected–self | ||||||

| Lingual Gyrus | 18 | R | 151 | 0.001 | 8.15 | 18, −82, −6 |

| Posterior cingulate | 7 | R | 1008 | 0.000 | 6.74 | 8, −24, 28 |

| Precuneus | 6.13 | −6, −62, 32 | ||||

| 5.88 | 8, −46, 16 | |||||

| Middle temporal | 21 | L | 135 | 0.002 | 6.36 | −52, −16, −12 |

| 5.03 | −60, −16, −14 | |||||

| Cuneus | 17 | R | 79 | 0.035 | 5.83 | 16, −76, 10 |

| Superior frontal | 6 | L | 140 | 0.002 | 4.84 | −2, 8, 56 |

| 4.35 | 6, 6, 48 | |||||

| 4.32 | −6, −2, 54 | |||||

| RAN group map: social reflected–self | ||||||

| Precuneus | 7 | L | 137 | 0.002 | 6.02 | −8, −64, 34 |

| 4.39 | −6, −72, 30 | |||||

| Posterior cingulate | 23 | R | 85 | 0.024 | 5.44 | 4, −30, 24 |

| 5.26 | 12, −26, 24 | |||||

| CON group map: social self–reflected: no regions | ||||||

| RAN group map: social self–reflected | ||||||

| Superior parietal | 7 | R | 96 | 0.013 | 5.54 | 26, −60, 54 |

| 4.52 | 20, −64, 60 | |||||

| 3.90 | 16, −70, 50 | |||||

| Medial frontal | 9 | R | 78 | 0.035 | 5.07 | 8, 30, 36 |

| 4.25 | −2, 34, 38 | |||||

| 3.93 | 6, 18, 36 | |||||

| Postcentral | 2 | R | 72 | 0.049 | 4.93 | 62, −24, 32 |

| 4.71 | 56, −16, 28 | |||||

| 4.19 | 60, −28, 40 | |||||

aCorrected cluster-wise, P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

The two-sample comparison of the CON and RAN groups in the social self–friend contrast (‘I am’) identified a cluster in the precuneus with a peak t of 4.61 consisting of 43 voxels. Slices centered on MNI coordinates of the peak voxel (−8, −48, 46). The percent signal change in this cluster for the self and friend conditions is shown for the CON and RAN groups in the lower right panel.

Table 3.

Clusters showing significant differences in activation in the two-sample comparisons of subjects recovering from anorexia (RAN) and the healthy comparison subjects (CON)a

| Anatomical region | BA | Laterality | MNI x, y, z | Cluster size | Peak t | Percent signal changeb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | RAN | ||||||

| Social task, CON–RAN, self–friend contrast | |||||||

| Precuneus | 7 | L | −8, −48, 46 | 43 | 4.61 | 0.09 | −0.04 (P < 0.001) |

| Social task, CON–RAN, friend–self contrast | |||||||

| Middle frontal | 6 | L | −40, 26, 24 | 43 | 4.15 | −0.10 | −0.53 (P = 0.001) |

| Social task, CON–RAN, reflected–self contrast | |||||||

| Cingulate | 32 | R | 6, 26, 36 | 379 | 5.74 | 0.08 | −0.09 (P < 0.001) |

| 6, 8, 46 | 4.89 | ||||||

| 4, 10, 60 | 4.55 | ||||||

| Physical task, CON–RAN, self–friend contrast | |||||||

| Anterior cingulate | 24 | L | −6, 20, 24 | 61 | 4.50 | 0.12 | −0.01 (P < 0.001) |

aSignificance threshold for two-sample t-tests were set at P ≤ 0.001 height, and extent of 20 voxels.

bP-value corresponds to independent sample t-tests across CON and RAN groups comparing percent signal change across that contrast in the identified ROI.

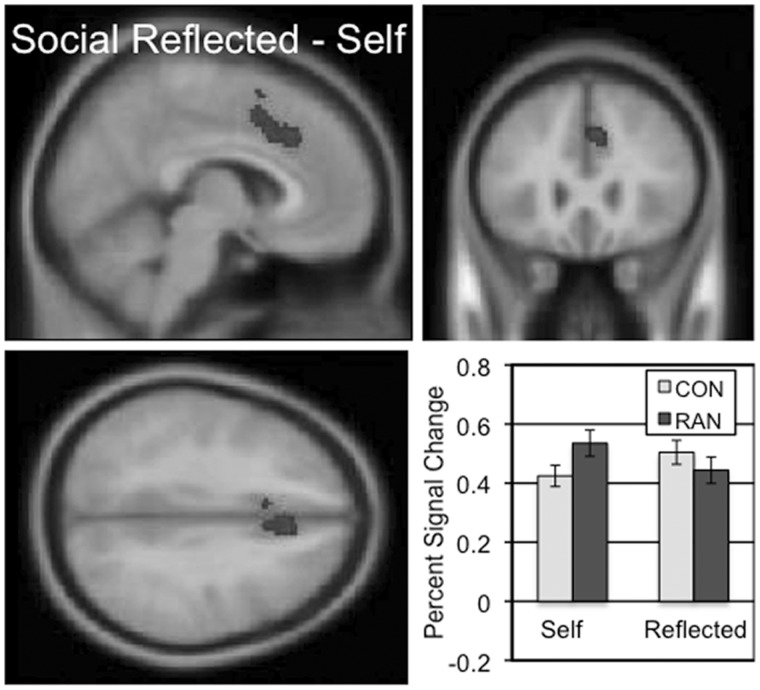

Cortical regions involved in mentalization (‘Friend believes’) were identified by contrasting activity in the social reflected and self conditions (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S3). The largest active regions in both the CON and RAN groups were in the posterior cingulate and the ventral precuneus. No other regions were selectively activated in this contrast in the RAN group. In the ‘Friend believes’ two-sample comparison contrast across the CON and RAN groups, a single, large region in the dorsal anterior cingulate (dACC) extending into DMPFC was identified (Figure 3 and Table 3; mean percent signal change, social reflected–self, CON 0.08, RAN − 0.09, t = 5.304, P < 0.001). This region showed increased activation in the reflected appraisals for CON subjects relative to the self appraisals, and more activation during self appraisals than reflected appraisals for the RAN subjects. In the social self–reflected (‘I believe’) contrast, the CON group showed no activation clusters but the RAN group had clusters in the frontal and parietal lobes (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S3).

Fig. 3.

The two-sample comparison of the CON and RAN groups in the social reflected–self contrast (‘Friend believes’) identified a cluster in the dorsal anterior cingulate and DMPFC with a peak t of 5.74 consisting of 379 voxels. Slices centered on MNI coordinates of the peak voxel (−6, 26, 36). The percent signal change in this cluster for the self and reflected conditions is shown for the CON and RAN groups in the lower right panel.

FMRI activation during physical appraisals in CON and RAN groups

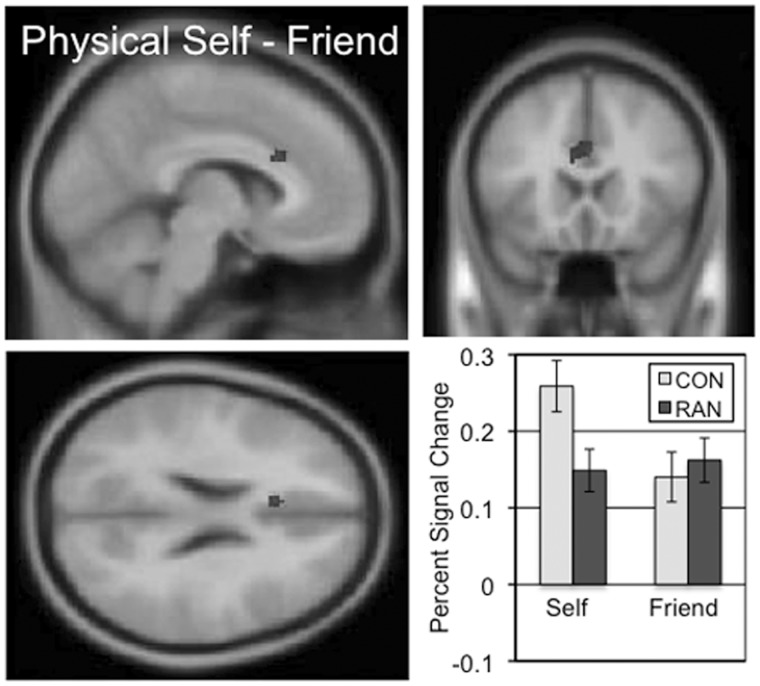

Cortical regions involved in the understanding of one’s own body image (‘I look’) were identified by contrasting activity across the self and friend conditions of the physical task (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S4). For the CON subjects, three clusters extended through the anterior and middle cingulate. The RAN subjects exhibited three clusters of activation in the inferior frontal gyri and medial frontal gyrus. The ‘I look’ two-sample comparison of the CON and RAN subjects identified a ventral region of the dorsal anterior cingulate immediately adjacent to the corpus callosum (cc-dACC) showing greater activation in the self condition than the friend condition in the CON subjects but similar levels of activation for both conditions in the RAN subjects (Figure 4 and Table 3; mean percent signal change, physical self–friend, CON 0.12, RAN − 0.01, t = 4.699, P < 0.001). Neither group showed any significant clusters in the physical friend–self contrast.

Table 4.

Locations of significantly activated regions in the physical task for the subjects recovering from anorexia (RAN) and the healthy comparison subjects (CON)

| Anatomical region | BA | Laterality | Cluster size | Cluster Pa | Peak t | MNI x, y, z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON group map: physical self–friend | |||||||

| Anterior cingulate | 32 | L | 614 | 0.000 | 7.64 | −6, 22, 24 | |

| 6.48 | −2, 34, 28 | ||||||

| 4.76 | 4, 20, 28 | ||||||

| Anterior cingulate | 32 | R | 104 | 0.011 | 6.23 | 2, 42, 12 | |

| Cingulate gyrus | 24 | R | 184 | 0.000 | 5.14 | 6, −8, 34 | |

| 5.03 | 4, −18, 32 | ||||||

| 4.85 | 8, −90, 42 | ||||||

| RAN group map: physical self–friend | |||||||

| Inferior frontal | 47 | R | 80 | 0.022 | 4.84 | 40, 16, −16 | |

| 4.24 | 48, 18, −16 | ||||||

| 4.01 | 48, 22, −8 | ||||||

| Medial frontal | 9 | L | 70 | 0.040 | 4.49 | −2, 36, 38 | |

| 3.95 | 2, 32, 44 | ||||||

| 3.74 | −4, 46, 30 | ||||||

| Inferior frontal | 47 | L | 70 | 0.040 | 4.45 | −50 20 −6 | |

| 4.40 | −50, 18, 2 | ||||||

| 3.7 | −42, 20, −10 | ||||||

| CON group map: physical reflected–self | |||||||

| Precuneus | 7 | L | 125 | 0.004 | 5.19 | −8, −62, 34 | |

| RAN group map: physical reflected–self | |||||||

| Precuneus | 7 | R | 186 | 0.000 | 5.20 | 8, −60, 30 | |

| L | 4.22 | −4, −56, 32 | |||||

| 3.84 | −8, −50, 24 | ||||||

| CON group map: physical self–reflected | |||||||

| Anterior cingulate | 32 | L | 280 | 0.000 | 5.99 | −10, 26, 24 | |

| 5.79 | −2, 38, 34 | ||||||

| R | 4.76 | 8, 34, 26 | |||||

| Middle frontal | 9 | R | 177 | 0.000 | 5.36 | 44, 14, 46 | |

| 4.72 | 48, 20, 40 | ||||||

| 3.66 | 44, 10, 34 | ||||||

| RAN group map: physical self–reflected | |||||||

| Anterior cingulate | 32 | L | 846 | 0.000 | 6.70 | −4, 30, 28 | |

| 6.42 | 6, 34, 36 | ||||||

| 6.14 | −4, 30, 38 | ||||||

aCorrected cluster-wise.

Fig. 4.

The two-sample comparison of the CON and RAN groups in the physical self–friend contrast (‘I look’) identified a cluster in the ventral anterior cingulate with a peak t of 4.50 consisting of 61 voxels. Slices centered on MNI coordinates of the peak voxel (−6, 20, 24). The percent signal change in this cluster for the self and friend conditions is shown for the CON and RAN groups in the lower right panel.

Cortical regions involved in mentalization about physical identity were also examined by contrasting activity in the physical reflected and self conditions (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S5). Both the CON and the RAN groups exhibited active ventral precuneus clusters. The opposite comparison, physical self–reflected, led to several regions of activation in both the CON and RAN groups with the largest clusters in the anterior and middle cingulate. There were no group differences in the two-sample comparisons for either the physical reflected–self or physical self–reflected contrasts.

Correlations between behavioral measures and fMRI activations

As the CON and RAN participant groups differed in the self-report measures for depression, eating attitudes, self-liking and self-competence, we examined whether the neural areas with significant activation differences identified from the two-sample comparisons described above (ROIs: social self–friend precuneus, social friend–self MFG, social reflected–self dACC and physical self–friend cc-dACC) were correlated with self-report scores. Although we did observe significant correlations between fMRI activations in these regions for the QIDS (dACC, r = −0.584, P < 0.001), EAT (dACC, r = −0.623, P < 0.001; cc-dACC, r = 0.420, P = 0.011), SL (dACC, r = 0.492, P = 0.002; precuneus, r = 0.415, P = 0.012; cc-dACC, r = 0.445, P = 0.007; MFG, r = 0.430, P = 0.009) and SC scores (cc-dACC, r = 0.419, P = 0.11), these correlations were entirely attributable to the group differences in these variables and were not significant when examined within either participant group separately (CON alone and RAN alone).

DISCUSSION

These experiments examined the fMRI activity involved in understanding one’s identity as well as other people’s perceptions of one’s identity in AN. The neuroimaging tasks were designed to elicit both a social understanding of identity, using an appraisal task consisting of performing judgments using standard personality trait adjectives, and a physical understanding of identity, using an appraisal task considering of performing judgments about physical characteristics.

Social and physical self-knowledge

We found that different regions of cortex were involved in the processing of social and physical self-knowledge. This was true for both for the healthy CON subjects: the social ‘I am’ contrast activated regions of the occipital lobe and the physical ‘I look’ contrast activated areas within the cingulate, and for the RAN subjects: the social ‘I am’ contrast activated many bilateral peripheral cortical regions while the physical ‘I look’ contrast significantly activated only the bilateral insula and MPFC. We also found group differences in the activation of the dACC in the social ‘Friend believes’ conditions. These data support the position that identity is a complex attribute, and also that knowledge about social descriptors is not the same as knowledge about one’s appearance. Additionally as the DSM-IV criteria describe AN as an illness with a low body weight in conjunction with physical identity disturbances (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), we were surprised that our results showed more neural differences in the comparisons related to the social task than the physical task. In sum, our results are consistent with literature proposing identity and self-esteem as core disturbances in AN (Stein and Corte, 2007, 2008), as well as studies suggesting that social cognition plays a role in AN (Zucker et al., 2007; Harrison et al., 2009; Harrison et al., 2010; Oldershaw et al., 2010; Mcadams and Krawczyk, 2011).

Our social appraisal task was similar to those used to study self-knowledge and mentalization in healthy controls in other studies. The cortical regions expected to be active during the self–friend ‘I am’ contrast and reflected–self ‘I believe’ contrast include the MPFC, the dACC, the vACC and the precuneus (Northoff et al., 2006; Heatherton, 2011). We chose to use a task that included a close other, a friend of the subject, because we were particularly interested in the neural activations associated with the third person perspective condition, a condition most appropriate with known, personalized others.

However, the use of a close other in comparison to a self-evaluation has shown inconsistent neural activations even in healthy individuals unlike those studies using a distant other or semantic comparison (Johnson et al., 2002; Kelley et al., 2002; Schmitz et al., 2004; Ochsner et al., 2005; Heatherton et al., 2006; D’Argembeau et al., 2007; Pfeifer et al., 2007; Modinos et al., 2009; Moran et al., 2009; Pfeifer et al., 2009). Four studies have used an fMRI task with a close friend as the other: two showed more activation in both anterior and posterior midline cortical structures in the self condition than the friend condition (Heatherton et al., 2006; D’Argembeau et al., 2007) and two found no differences in midline cortical structures (Schmitz et al., 2004; Ochsner et al., 2005), akin to our data. Two other studies have used the subject’s mother as the comparator; one found increased ACC for self compared with mother (Vanderwal et al., 2008) and the other (Zhu et al., 2007) found increased MPFC activation for self compared with mother in Western individuals but no differences in Chinese individuals. Together these studies have suggested that the more one perceives one’s friend to be similar to oneself, the less likely neuroimaging studies are to show differences in midline cortical structures (Heatherton, 2011). Here, the similar activation of the midline cortical structures in the self and friend conditions in the CON group suggests that these conditions elicited similar cognitive processing. This is in marked contrast to the RAN subjects for whom many clusters, including the dACC but also a number of peripheral cortical regions emerged in the social self and friend comparison.

Of note, another important variable in detecting activations is the threshold set for cluster extent, and these thresholds vary in the literature. We lowered our threshold by changing the extent from a cluster-P corrected 0.05 value to a 10 voxel extent, as was more common in early fMRI studies, observing clusters in both the precuneus (47 voxels, t = 4.84) and the middle cingulate (44 voxels, t = 5.92) in the CON (but not RAN) group, akin to both the D’Argembeau and Heatherton studies consisting of healthy controls (Supplementary Figure S6). We also examined the percent signal change using these two ROIs for both the CON and RAN populations, recognizing that this is a non-standard comparison for clinical neuroimaging. In the CON group, we found increased percent signal change in both of these regions in the self condition relative to the friend condition. In the RAN group, the precuneus shows the opposite effect, and the modulation of the cingulate is reduced. These data are consistent with our other findings that the midline cortical structures are differentially activated in participants recovering from AN compared with healthy participants.

The region that emerged in the two-sample comparison between the CON and RAN groups in the social self–friend contrast was the precuneus. The precuneus is a cortical region in the parietal lobe with connections to the limbic system, the parietal cortex, the occipital lobe and the temporal lobe (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006); this region has been proposed to integrate emotional, physical and visual inputs into a view of self relevant to consciousness (Northoff et al., 2006; Cavanna, 2007). The precuneus has been divided into multiple regions, with the dorsal portion, that we observed to have lower activity in RAN subjects than the CON subjects in the social ‘I am’ contrast, involved in self-assessments, and a ventral region contiguous with the posterior cingulate activated by perspective-taking tasks, akin to our social ‘Friend believes’ contrast (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006; Northoff et al., 2006). Pfieffer and colleagues (Pfeifer et al., 2009) recently compared the neural activity associated with performing social appraisal tasks in healthy adults and adolescents and found increased activation within the posterior cingulate and precuneus in adolescents performing social appraisal tasks relative to the adults.

Other neurodevelopmental and physiological information about the precuneus supports a role for this area in the pathology of AN. The precuneus is the last cortical region to myelinate, along with prefrontal cortex, typically completing myelination during adolescence (Goldman-Rakic, 1987). The connectivity between the anterior cingulate and the precuneus also increases with age in comparisons of children, adolescents and adults (Kelly et al., 2009). These studies suggest that normal neurodevelopmental processes lead to maturation of the precuneus during adolescence, the same period as the typical onset of AN (Kaye, 2008). Neuroimaging studies in healthy controls have also observed precuneus activation during set-shifting, executive-function tasks, mentalization and ToM tasks (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006); all functions reported to be impaired in AN (Gillberg et al., 2007; Harrison et al., 2009; Gillberg et al., 2010; Rothschild-Yakar et al., 2010). Finally, the precuneus is highly active in the resting state and consumes ∼35% more glucose than any other area of human cerebral cortex (Gusnard and Raichle, 2001). This high utilization of glucose suggests that this region may be particularly susceptible to degeneration in starvation. We were unable to determine whether the differences we observed in the precuneus in RAN were present before AN began and related to its pathogenesis or whether the precuneus was secondarily damaged by this illness. Further research may allow the effects of neurodevelopmental changes to be separated from possible physiological consequences from starvation, but such information may only be attainable from a larger longitudinal study.

The physical task directly examined the cognitive processes associated with evaluation of body shape. In the CON group map for the ‘I look’ contrast, we observed several clusters in the anterior and middle cingulate whereas in the RAN group map, there were clusters in the bilateral insula and dACC and no activations in the cingulate. The subgenual anterior cingulate has been previously reported to be smaller in AN, and the amount of the size reduction has even been related to the severity of the illness (Naruo et al., 2001; Muhlau et al., 2007; McCormick et al., 2008). The cingulate is often engaged in tasks involving self-regulation, such as considering one’s current physiological or emotional state (Heatherton, 2011). Alexithymia has been correlated with decreased activity in the anterior cingulate in both healthy controls and AN patients (Miyake et al., 2009), reinforcing the notion of this area as mediating self-understanding. In both a social economic game and a self-imagery paradigm, activation of the middle cingulate has been associated with directly with reflection on the consequences of one’s own behavior (Chiu et al., 2008). Interestingly, the RAN subjects, unlike the CON subjects, did show modulation of this part of the cingulate during the contrast of the physical reflected (‘Friend believes I look’) and the physical self (‘I believe I look’) conditions (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S5). If the cingulate is considered to monitor current self-state (Northoff et al., 2006; Heatherton, 2011), then these findings are consistent with an idea that cc-dACC of the RAN subjects may have learned that their friend’s belief about their own appearance is a more accurate portrayal of current physical state than their own belief about their appearance.

Mentalization in AN

The process of mentalization has been a topic highly relevant to psychiatric treatment (Bateman and Fonagy, 2004). The third-person appraisal condition in social appraisal tasks ‘Friend believes’ has consistently shown strong activations in the precuneus and posterior cingulate as well as other cortical regions activated in social cognition tasks in healthy controls (D’Argembeau et al., 2007; Pfeifer et al., 2009). Consistent with this literature, the CON group showed robust activation of the ventral precuneus and posterior cingulate and other clusters in the social cognition network including the medial temporal gyrus and dACC. The RAN group showed activation of only two regions: the ventral precuneus and posterior cingulate.

A cluster in the dACC was identified in the whole-brain voxel-wide comparison of the social reflected–self contrast for the CON and RAN groups. This cluster, although primarily in the right hemisphere, extended into the DMPFC and left paracingulate. Social appraisal studies in healthy controls have typically reported the involvement of the dACC, DMPFC, the ventral precuneus and the posterior cingulate in understanding other people rather than one’s own self (Ochsner et al., 2005; Pfeifer et al., 2009). On examination of the percent signal change in the dACC cluster, we found that the CON subjects showed elevated activation in the social ‘Friend believes’ condition relative to the ‘I am’ condition and the RAN subjects showed the opposite pattern, despite both groups showing similar levels of BOLD modulation. This differs fundamentally from the other regions identified from the group differences, the precuneus and vACC, regions in which the RAN group showed no modulation of the BOLD signal. Interestingly, the same contrast in the physical task shows no differences in the CON and RAN whole-brain comparison. These findings suggest that thinking about one’s physical appearance from a third person’s point of view is quite similar for the CON and RAN subjects but thinking about one’s social traits from a third-person’s view differs.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to the neuroimaging tasks used in this study. First, the social task was conducted separately from the physical task, and the statements were shown in block mode by condition rather than being randomly interleaved. This design was deliberate so that subjects could stay focused on one condition rather than switching between the six types of statements presented, which may have resulted in confusion for the subjects. Second, the social adjectives were selected from the top and bottom most liked words using a standard list of likableness ratings of the words (Anderson, 1968). Thus, every social appraisal involved either a strong positive or negative valence, and we were unable to separate the valence judgment from the self-knowledge judgment. As we did observe significantly lower behavioral ratings of the social adjectives by the RAN subjects for both the self and reflected conditions (Supplementary Table S2), these behavioral data are consistent with RAN subjects having a more critical perception of their social identity. A similar overall negative self-concept has been described in current ED subjects (Stein and Corte, 2003; Paterson et al., 2010). Moran et al. (2006) conducted a self-reflective personality fMRI task in healthy subjects designed to separate effects of valence from self-relevance; they reported that self-relevance was coded independent of valence in the posterior cingulate and MPFC, whereas valence of the adjectives was related to ventral ACC activity, and that both factors showed an interaction in the ventral ACC. Similar future studies in RAN subjects may help us better understand whether some of the neural differences we observed are related to valence as well as self-knowledge.

Other limitations involved the variability in clinical state associated with our particular patient population. We included adult AN subjects who had the illness in the previous 2 years for our exploratory study of neural activations associated with identity in this illness. The resulting patient population shows a wide variety of clinical characteristics that may best be described as remitted. Recovery rates for adults with AN range from 21% to 68% (Rigaud et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011); statistically, it suggests that some of our participants will relapse and others will recover. Additionally, AN patients do not show normalization of the cognitive characteristics associated with AN until at least 2 years following weight recovery (Strober et al., 1997; Bachner-Melman et al., 2006; Bardone-Cone et al., 2010). Subsequently, our data cannot distinguish between neural differences that predispose to, contribute to, or result from AN: they only show a correlation with having had this illness recently. Couturier and Lock (2006), Darcy (2010) and Bardone-Cone (2010) have emphasized that recovery should include both psychological and physiological measures. Although we did include psychological measures, another limitation of our study was that these were assessed primarily through self-report scales. Future studies that include more subjects, and more detailed phenotyping with clinician-scored measures in concert with neuroimaging will be essential in understanding how pathology and neural activations relate.

CONCLUSION

Our results support the idea that identity, including components associated with ‘I am’, ‘I look’ and ‘I believe’, utilize different cortical regions in AN. Regardless of the cause of problems in the neural networks associated with identity, consideration of the function of these cortical regions in healthy brains may help patients to recognizing that problems in identity, self-esteem and mentalization may be part of the illness. Tchanturia and colleagues (2008) reported success in the treatment of AN in a pilot study using cognitive-remediation therapies focused on improving cognitive flexibility, a function frequently associated with the precuneus (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006). Maudsley family-based therapy has also shown promise in the treatment of adolescent AN; this approach focuses on ensuring weight gain in the context of the family providing support to ensure both nutrition for the patient, and enabling the parents to help the adolescent develop their identity (Lock, 2002; Lock and Le Grange, 2005; Loeb et al., 2007). Additional research examining the effects of therapeutic interventions on neural activity within the identity network may help us better understand the mechanisms that mediate successful psychiatric treatments.

We cannot determine whether the neural differences we have found contribute to the development of AN or are consequences of AN. These are difficult questions to address: AN has a low incidence rate, making it difficulty to examine individuals before and after illness onset, and there is also a variable interval between onset of the disease, obtaining treatment and reaching recovery. These questions should be examined both through comparisons between currently ill and fully recovered AN subjects as well as through longitudinal studies of AN patients at the start of illness and following recovery. Further studies examining identity through the use of fMRI may be able to separate cortical regions that change in response to treatments and those that are not.

In conclusion, we propose that primary neural processes, including modulation of the precuneus and vACC, which are utilized to interpret one’s self-knowledge are impaired in AN, and that other regions, including the dACC and MFG, may be involved in compensating for these deficiencies. These experiments provide a deeper understanding of both biological and psychological components of AN and support consideration of identity, both social and physical, as a feature of the illness.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at SCAN online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ehsan Shokri Kojori for assistance with programming and data analysis; M. Michelle McClelland, Sunbola Ashimi, Lauren Monier and Joanne Thambuswamy for assistance in the execution of this project and both The Elisa Project and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas for assistance in recruitment of subjects. This work was supported by unspecified funds from the School of Behavioral and Brain Science at the University of Texas at Dallas, the UT Southwestern Medical Center Physician Scientist Training Program, and National Institutes of Mental Health grant K23 MH093684-01A1.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.) Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NH. Likableness ratings of 555 personality-trait words. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9(3):272–9. doi: 10.1037/h0025907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachner-Melman R, Zohar AH, Ebstein RP. An examination of cognitive versus behavioral components of recovery from anorexia nervosa. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194(9):697–703. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000235795.51683.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone-Cone AM, Harney MB, Maldonado CR, Lawson MA, Robinson DP, Smith R, et al. Defining recovery from an eating disorder: conceptualization, validation, and examination of psychosocial functioning and psychiatric comorbidity. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2010;48(3):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18(1):36–51. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.36.32772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berland NW, Thompson JK, Linton PH. Correlation between the Eat-26 and the Eat-40, the Eating Disorders Inventory, and the Restrained Eating Inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1986;5(3):569–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke MP, Taylor GJ, Parker JD, Bagby RM. Alexithymia in women with anorexia nervosa. A preliminary investigation. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;161:240–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button EJ, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Davies J, Thompson M. A prospective study of self-esteem in the prediction of eating problems in adolescent schoolgirls: questionnaire findings. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;35(Pt 2):193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Deagle EA., 3rd The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(2):107–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli F, Frith C, Happe F, Frith U. Autism, Asperger syndrome and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 8):1839–49. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE. The precuneus and consciousness. CNS Spectrums. 2007;12(7):545–52. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900021295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Trimble MR. The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 3):564–83. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu PH, Kayali MA, Kishida KT, et al. Self responses along cingulate cortex reveal quantitative neural phenotype for high-functioning autism. Neuron. 2008;57(3):463–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcos M, Guilbaud O, Speranza M, et al. Alexithymia and depression in eating disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2000;93(3):263–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J, Lock J. What is recovery in adolescent anorexia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(7):550–5. doi: 10.1002/eat.20309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darcy AM, Katz S, Fitzpatrick KK, Forsberg S, Utzinger L, Lock J. All better? How former anorexia nervosa patients define recovery and engaged in treatment. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18(4):260–70. doi: 10.1002/erv.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argembeau A, Ruby P, Collette F, et al. Distinct regions of the medial prefrontal cortex are associated with self-referential processing and perspective taking. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(6):935–44. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederich HC, Brooks S, Uher R, et al. Neural correlates of body dissatisfaction in anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(10):2878–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Frith U. The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron. 2006;50(4):531–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg IC, Billstedt E, Wentz E, Anckarsater H, Rastam M, Gillberg C. Attention, executive functions, and mentalizing in anorexia nervosa eighteen years after onset of eating disorder. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2010;32(4):358–65. doi: 10.1080/13803390903066857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg IC, Rastam M, Wentz E, Gillberg C. Cognitive and executive functions in anorexia nervosa ten years after onset of eating disorder. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29(2):170–8. doi: 10.1080/13803390600584632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. Development of cortical circuitry and cognitive function. Child Development. 1987;58(3):601–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusnard DA, Raichle ME. Searching for a baseline: functional imaging and the resting human brain. Nature Review Neuroscience. 2001;2(10):685–94. doi: 10.1038/35094500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J. Emotion recognition and regulation in anorexia nervosa. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2009;16(4):348–56. doi: 10.1002/cpp.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Tchanturia K, Treasure J. Attentional bias, emotion recognition, and emotion regulation in anorexia: state or trait? Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(8):755–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Wyland CL, Macrae CN, Demos KE, Denny BT, Kelley WM. Medial prefrontal activity differentiates self from close others. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2006;1(1):18–25. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF. Neuroscience of self and self-regulation. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:363–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Baxter LC, Wilder LS, Pipe JG, Heiserman JE, Prigatano GP. Neural correlates of self-reflection. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 8):1808–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye W. Neurobiology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Physiology and Behavior. 2008;94(1):121–35. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WM, Macrae CN, Wyland CL, Caglar S, Inati S, Heatherton TF. Finding the self? An event-related fMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14(5):785–94. doi: 10.1162/08989290260138672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AM, Di Martino A, Uddin LQ, et al. Development of anterior cingulate functional connectivity from late childhood to early adulthood. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(3):640–57. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska-Pietura K, Nikolaou V, Masiak M, Treasure J. The recognition of emotion in the faces and voice of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35(1):42–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J. Treating adolescents with eating disorders in the family context. Empirical and theoretical considerations. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;11(2):331–42. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, le Grange D. Family-based treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;37(Suppl.):S64–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20122. discussion S87–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb KL, Walsh BT, Lock J, et al. Open trial of family-based treatment for full and partial anorexia nervosa in adolescence: evidence of successful dissemination. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):792–800. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318058a98e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams CJ, Krawczyk DC. Impaired neural processing of social attribution in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Research. 2011;194(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick LM, Keel PK, Brumm MC, et al. Implications of starvation-induced change in right dorsal anterior cingulate volume in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(7):602–10. doi: 10.1002/eat.20549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y, Okamoto Y, Onoda K, Shirao N, Mantani T, Yamawaki S. Neural correlates of alexithymia in response to emotional stimuli: a study of anorexia nervosa patients. Hiroshima Journal of Medical Sciences. 2009;58(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y, Okamoto Y, Onoda K, Shirao N, Otagaki Y, Yamawaki S. Neural processing of negative word stimuli concerning body image in patients with eating disorders: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2010;50(3):1333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modinos G, Ormel J, Aleman A. Activation of anterior insula during self-reflection. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JM, Macrae CN, Heatherton TF, Wyland CL, Kelley WM. Neuroanatomical evidence for distinct cognitive and affective components of self. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18(9):1586–94. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.9.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JM, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM. Modulation of cortical midline structures by implicit and explicit self-relevance evaluation. Soc Neurosci. 2009;4(3):197–211. doi: 10.1080/17470910802250519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlau M, Gaser C, Ilg R, et al. Gray matter decrease of the anterior cingulate cortex in anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(12):1850–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruo T, Nakabeppu Y, Deguchi D, et al. Decreases in blood perfusion of the anterior cingulate gyri in Anorexia Nervosa Restricters assessed by SPECT image analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2001;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemiah JC. Alexithymia. Theoretical considerations. Psychother Psychosom. 1977;28(1–4):199–206. doi: 10.1159/000287064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K, Hagglof B. Patient perspectives of recovery in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa. Eating Disorders. 2006;14(4):305–11. doi: 10.1080/10640260600796234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Heinzel A, de Greck M, Bermpohl F, Dobrowolny H, Panksepp J. Self-referential processing in our brain–a meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage. 2006;31(1):440–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Beer JS, Robertson ER, et al. The neural correlates of direct and reflected self-knowledge. Neuroimage. 2005;28(4):797–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldershaw A, Hambrook D, Tchanturia K, Treasure J, Schmidt U. Emotional theory of mind and emotional awareness in recovered anorexia nervosa patients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72(1):73–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181c6c7ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson G, Power K, Yellowlees A, Park K, Taylor L. The relationship between two-dimensional self-esteem and problem solving style in an anorexic inpatient sample. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15(1):70–7. doi: 10.1002/erv.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, Lieberman MD, Dapretto M. “I know you are but what am I?!”: neural bases of self- and social knowledge retrieval in children and adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(8):1323–37. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.8.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Borofsky LA, Dapretto M, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD. Neural correlates of direct and reflected self-appraisals in adolescents and adults: when social perspective-taking informs self-perception. Child Development. 2009;80(4):1016–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud D, Pennacchio H, Bizeul C, Reveillard V, Verges B. Outcome in AN adult patients: A 13-year follow-up in 484 patients. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37(4):305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild-Yakar L, Levy-Shiff R, Fridman-Balaban R, Gur E, Stein D. Mentalization and relationships with parents as predictors of eating disordered behavior. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198(7):501–7. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e526c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev P, Mondraty N, Wen W, Gulliford K. Brains of anorexia nervosa patients process self-images differently from non-self-images: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(8):2161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Wexler A. Making sense of another mind: the role of the right temporo-parietal junction. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(10):1391–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Xiao DK, Kovacs G, Perrett DI, Kanwisher N. A region of right posterior superior temporal sulcus responds to observed intentional actions. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(11):1435–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz TW, Kawahara-Baccus TN, Johnson SC. Metacognitive evaluation, self-relevance, and the right prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage. 2004;22(2):941–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RT, Grelotti DJ, Klin A, et al. The role of the fusiform face area in social cognition: implications for the pathobiology of autism. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences. 2003;358(1430):415–27. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone PH. Is chronic low self-esteem the cause of eating disorders? Medicial Hypotheses. 1992;39(4):311–5. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(92)90054-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypek S, Wehmeier PM, Remschmidt H. Body image assessment using body size estimation in recent studies on anorexia nervosa. A brief review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;10(4):215–21. doi: 10.1007/s007870170010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF, Corte C. Identity impairment and the eating disorders: content and organization of the self-concept in women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15(1):58–69. doi: 10.1002/erv.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF, Corte C. Reconceptualizing causative factors and intervention strategies in the eating disorders: a shift from body image to self-concept impairments. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2003;17(2):57–66. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KF, Corte C. The identity impairment model: a longitudinal study of self-schemas as predictors of disordered eating behaviors. Nursing Research. 2008;57(3):182–90. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000319494.21628.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10–15 years in a prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(4):339–60. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199712)22:4<339::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgenor LJ, Maguire S, Russell J, Touyz S. Self-liking and self-competence: relationship to symptoms of anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15(2):139–45. doi: 10.1002/erv.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafarodi RW, Swann WB., Jr. Self-linking and self-competence as dimensions of global self-esteem: initial validation of a measure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;65(2):322–42. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6502_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troop NA, Bifulco A. Childhood social arena and cognitive sets in eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41(Pt 2):205–11. doi: 10.1348/014466502163976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlinden J, Kamphuis JH, Slagmolen C, Wigboldus D, Pieters G, Probst M. Be kind to your eating disorder patients: the impact of positive and negative feedback on the explicit and implicit self-esteem of female patients with eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2009;14(4):e237–42. doi: 10.1007/BF03325124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwal T, Hunyadi E, Grupe DW, Connors CM, Schultz RT. Self, mother and abstract other: an fMRI study of reflective social processing. Neuroimage. 2008;41(4):1437–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocks S, Schulte D, Busch M, Gronemeyer D, Herpertz S, Suchan B. Changes in neuronal correlates of body image processing by means of cognitive-behavioural body image therapy for eating disorders: a randomized controlled fMRI study. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(8):1651–63. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A, Ruf M, Braus DF, Schmidt MH. Neuronal activity changes and body image distortion in anorexia nervosa. Neuroreport. 2003;14(17):2193–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200312020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentz E, Gillberg C, Gillberg IC, Rastam M. Ten-year follow-up of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: psychiatric disorders and overall functioning scales. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42(5):613–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Stewart Agras W, Halmi KA, Crow S, Mitchell J, Bryson SW. A 1-year follow-up of a multi-center treatment trial of adults with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(3):e177–81. doi: 10.1007/BF03325129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Yi J, Yao S, Ryder AG, Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Cross-cultural validation of a Chinese translation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonnevijlle-Bender MJ, van Goozen SH, Cohen-Kettenis PT, van Elburg A, van Engeland H. Do adolescent anorexia nervosa patients have deficits in emotional functioning? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;11(1):38–42. doi: 10.1007/s007870200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker NL, Losh M, Bulik CM, LaBar KS, Piven J, Pelphrey KA. Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders: guided investigation of social cognitive endophenotypes. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(6):976–1006. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.